Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The longtime U.S. senator believes that Griner's nine-year prison sentence in Russia is ridiculous.

Griner, a WNBA star, was sentenced to nine years in a Russian prison for drug smuggling.

"Sentencing Brittney Griner to nine years in prison in Russia is absolutely outrageous. She should not be a victim of geo-political tensions. She should be released immediately and allowed to come home," Sanders wrote.

The United States is currently working on a prisoner exchange deal with Griner.

Hopefully the WNBA star will be brought home soon.

Serhil Ardolyanova, 54, embraces his daughters, Inna, 31, and Masha, 10, before they depart on an evacuation bus at a humanitarian aid center for internally displaced people in Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, on Aug. 19. (photo: Heidi Levine/WP)

Serhil Ardolyanova, 54, embraces his daughters, Inna, 31, and Masha, 10, before they depart on an evacuation bus at a humanitarian aid center for internally displaced people in Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, on Aug. 19. (photo: Heidi Levine/WP)

The ominous threat to the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, Europe’s largest, alarmed world powers and renewed calls by U.N. Secretary General António Guterres for an immediate cessation of hostilities and access for international nuclear experts.

“Any potential damage to Zaporizhzhia is suicide,” Guterres said after a meeting in Ukraine with President Volodymyr Zelensky and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Ukrainian officials said the Kremlin was behind explosions at the plant meant to create a “provocation.” Russian President Vladimir Putin accused Ukraine of shelling the plant and risking a “large-scale catastrophe.” Both Russia and Ukraine are warning that the other could conduct a “false flag” attack, an operation designed to disguise the country responsible.

Putin made the comments, his first about the recent fighting around the large complex along the Dnieper River, during a phone call with French President Emmanuel Macron. Like many world leaders, Macron emphasized the need for U.N. nuclear experts to visit the site under conditions laid out by Ukraine and the United Nations.

In the area around the plant, some families packed up their possessions and started to flee. Fathers and husbands, unable to leave on buses with their families, helped load belongings and waved to their loved ones in tearful goodbyes at a parking lot in the city of Zaporizhzhia, 30 miles to the northeast.

“It was a hard decision to make,” Serhii Aroslanov, 46, said of sending his family away as they boarded a bus to Bulgaria. “They are leaving because of the threat to the plant.” They planned to travel on to Germany, he told The Washington Post. Men between 18 and 60 years old are banned from leaving Ukraine in case they are needed for military service.

The nuclear power plant is currently under Russian control but operated by Ukrainian staff.

Russian forces ordered workers at the plant to stay home Friday and to limit personnel at the complex to only those who operate the plant’s power units, according to Energoatom, Ukraine’s state-run nuclear company.

Ukrainian officials accused Russian forces of preparing to disconnect the plant from Ukraine’s electric grid, depriving the country of a major source of power.

Guterres warned against any attempt to cut power to or from the facility and called for the area around the plant to be demilitarized.

“Obviously the electricity from Zaporizhzhia is Ukrainian electricity, and it’s necessary, especially during the winter, for the Ukrainian people. And this principle must be fully respected,” he said.

U.S. officials have watched fighting in the area with great concern and are monitoring reports of damage to the facility with a particular focus on power lines, a senior U.S. defense official told reporters Friday. The United States has called on Russia to relinquish control and withdraw from the area to reduce further risk.

“Fighting near a nuclear plant is dangerous,” the official said. “It’s really the height of irresponsibility.” The official spoke on the condition of anonymity under ground rules set by the Pentagon.

Russia’s Foreign Ministry has rejected a proposal to demilitarize the area around the Zaporizhzhia plant, saying that it would make the facility “more vulnerable.” The presence of Russian troops near the plant is a “guarantee” there will be no reprise of the Chernobyl disaster, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said Friday.

“The recklessness with which our opponents are playing with nuclear safety poses threats to the largest nuclear site in Europe, involving potential risks for a huge territory, not only that surrounding the plant but also far beyond Ukrainian borders,” he told Russia’s Rossiya-1 television channel.

Ryabkov also warned parties of “carelessness” in the pursuit of “geopolitical goals.”

The International Atomic Energy’s director general, Rafael Mariano Grossi, warned that any further escalation related to the six-reactor plant could lead to a severe nuclear accident with potentially grave consequences for human health and the environment in Ukraine and elsewhere.

“In this highly volatile and fragile situation, it is of vital importance that no new action is taken that could further endanger the safety and security of one of the world’s largest nuclear power plants,” Grossi said.

Efforts to organize a visit by members of the IAEA have been thwarted by logistical and political disagreements.

Russian officials have proposed that experts could travel through the Russian-controlled Crimean Peninsula, but Ukraine, which claims the peninsula as its own, has called that a violation of its sovereignty and requested that visitors arrive through the capital, Kyiv.

On Friday, the Russian government said Putin supports an IAEA visit, but it was far from clear that it would happen with fighting continuing around the plant.

For the most part, Zaporizhzhia on Friday looked much as it has during months of conflict, as most war-weary residents stayed put despite the threat.

For some families, however, it was the second time they have been displaced. “We’d been thinking about them leaving for a month,” Oleksander Soroka, 37, said of his wife and two children, who were boarding a bus to the Polish border. “But it was only this morning that it was finalized.”

“It’s really hard,” Soroka added. He had been living with his family in Zaporizhzhia since March after fleeing the nearby Russian-held town of Pology.

Employees based in Enerhodar, the Russian-held city that is home to the plant, told The Post of the daily terror of working at the nuclear facility. Amid the deteriorating security situation, vital workers such as engineers and operational staff have fled to Ukrainian-held territory in recent weeks, they said, adding to worries about the plant’s functioning.

There are few residents of Enerhodar, a town with a prewar population of about 50,000, who don’t have some kind of connection to the plant.

The city was built in 1970 for families of workers at the nearby coal-fired power station on the river. The nuclear plant covers about half a square mile and was added 10 years later.

Katya Lubitskaya, a 33-year-old former resident of Enerhodar, said she is frightened about the safety of her mother and grandmother, who are still in the city.

“The scariest scenario is something like Chernobyl but worse,” she said, referring to the 1986 nuclear disaster.

She has encouraged her relatives to leave, but it is difficult. People have waited in lines for more than four days in their cars in the summer heat as artillery fire flies overhead. “It is not easy to find a car and driver either,” she said.

As Ukraine and Russia warned Friday of nuclear catastrophe, Lubitskaya said she was more alarmed but felt powerless. “For now, I can do nothing,” she said.

Also Friday, there were unconfirmed reports of explosions in the Russian-held Crimean Peninsula and a large explosion at a weapons depot in the Russian border city of Belgorod. Some Ukrainian officials said the attacks were carried out by Ukrainian special forces units.

Fighting has also intensified in the northeastern city of Kharkiv, where Russian rockets continued to cause damage and casualties early Friday, according to the regional governor. At least 17 people were killed and 42 wounded in two separate Russian attacks in recent days, Oleh Synyehubov said.

The Biden administration hopes steady deliveries of military aid will help tilt the trajectory of the war in Ukraine’s favor even as Russia makes incremental progress in the country’s east. The United States is poised to send an additional $775 million worth of security assistance for Ukrainian forces, marking more than $10 billion in aid since President Biden took office, the U.S. defense official said.

New items provided by the United States include ScanEagle drones that will allow Ukrainian forces to locate targets for their artillery crews, and blast-resistant armored vehicles that will help ground troops navigate mined areas. Those and other items will help increase mobility, the official said, as Ukraine looks toward future counteroffensives.

Newly provided Carl Gustaf recoilless rifles and TOW antiarmor systems point to a need for Ukrainian troops to move closer to enemy formations and destroy vehicles and fighting positions, a shift from the largely long-distance artillery fight occurring in the eastern part of the country.

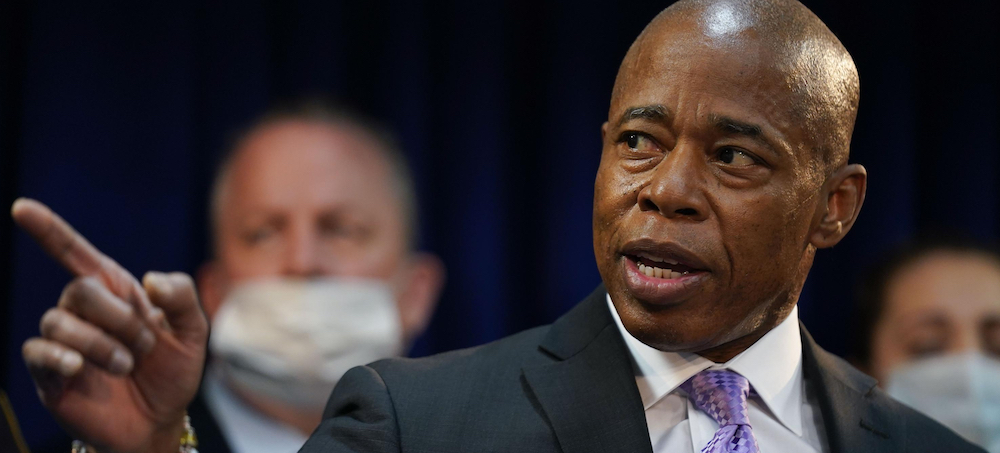

New York City mayor Eric Adams. (photo: Seth Wenig/AP)

New York City mayor Eric Adams. (photo: Seth Wenig/AP)

The mayor has chosen sides in at least 10 primaries this year, as he looks to enact criminal justice changes and defeat left-leaning candidates.

Mayor Eric Adams of New York City does not subscribe to that theory.

Just seven months into his first term, Mr. Adams, a Democrat, has injected himself into his party’s divide, making endorsements in roughly a dozen state legislative primaries.

Mr. Adams has endorsed incumbents, upstart challengers, and even a minister with a history of making antisemitic and homophobic statements.

Behind all the endorsements lies a common theme: The mayor wants to push Albany and his party away from the left, toward the center.

“I just want reasonable thinking lawmakers. I want people that are responding to the constituents,” Mr. Adams said Thursday. “The people of this city, they want to support police, they want safe streets, they want to make sure people who are part of the catch-release-repeat system don’t continue to hurt innocent New Yorkers.”

In Tuesday’s State Senate primary, the mayor has endorsed three candidates facing rivals backed by the Democratic Socialists of America. The mayor said the endorsements are meant to help elect people willing to tighten the state’s bail law, a move that he believes is needed to address an uptick in serious crime.

Mr. Adams’s most striking endorsement might be his decision to back the Rev. Conrad Tillard, who has disavowed his remarks about gay people and Jews, over incumbent Senator Jabari Brisport, a member of the Democratic Socialists.

The mayor, who proudly hires people with troubled pasts, said Mr. Tillard is a changed man. During a recent interview on WABC radio, Mr. Tillard said that Mr. Adams was elected with a “mandate” to make New York City safer.

“I want to join him in Albany, and I want to join other legislators who have common sense, who realize that without safe streets, safe communities, we cannot have a thriving city,” he said.

The mayor has also held a fund-raiser for Miguelina Camilo, a lawyer running against Senator Gustavo Rivera in the Bronx. Mr. Rivera was endorsed by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who has criticized Mr. Adams for some of his centrist views; Ms. Camilo is the candidate of the Bronx Democratic Party.

In a newly created Senate district that covers parts of Queens, Brooklyn and Manhattan, the mayor has endorsed a moderate Democrat, Elizabeth Crowley, over Kristen Gonzalez, a tech worker who is supported by the Democratic Socialists and the Working Families Party. Mike Corbett, a former City Council staff member, is also running. The race has been flooded with outside money supporting Ms. Crowley.

In Brooklyn, Mr. Adams endorsed incumbent Senator Kevin Parker, who is facing a challenge from Kaegan Mays-Williams, a former Manhattan assistant district attorney, and David Alexis, a former Lyft driver and co-founder of the Drivers Cooperative who also has support from the Democratic Socialists.

Three candidates — Mr. Brisport, Ms. Gonzalez and Mr. Alexis — whose rivals were supported by Mr. Adams said they are opposed to revising the bail law to keep more people in jail before their trials.

“When it comes to an issue like bail reform, what we don’t want to have is a double standard where if you have enough money you can make bail and get out, but if you are poor or working class you don’t,” Ms. Gonzalez said.

Mr. Brisport said that the mayor’s motive extends beyond bail and criminal justice issues.

Mr. Adams, Mr. Brisport said, is “making a concerted effort to build a team that will do his bidding in Albany.”

The mayor did not disagree.

In his first dealings with Albany as a mayor, Mr. Adams fell short of accomplishing his legislative agenda. He had some victories, but was displeased with the Legislature’s refusal to accommodate his wishes on the bail law or to grant him long-term control of the schools, two issues central to his agenda.

While crime overall remains comparatively low and homicides and shootings are down, other crimes such as robbery, assault and burglary have increased as much as 40 percent compared with this time last year. Without evidence, the mayor has blamed the bail reform law for letting repeat offenders out of jail.

Under pressure from the governor, the Legislature in April made changes to the bail law, but the mayor has repeatedly criticized lawmakers for not going far enough.

“We passed a lot of laws for people who commit crimes, but I just want to see what are the list of laws we pass that deal with a New Yorker who was the victim of a crime,” Mr. Adams said.

The mayor’s strategy is not entirely new. Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg sought influence by donating from his personal fortune to Republicans. Mayor Bill de Blasio embarked on a disastrous fund-raising plan to help Democrats take control of the Senate in 2014. But those mayors were interceding in general elections, not intraparty primaries.

In the June Assembly primaries, Mr. Adams endorsed a handful of incumbents facing upstart challengers from the left. He backed Michael Benedetto, an incumbent from the Bronx who beat back a primary challenge from Jonathan Soto, who worked for, and was endorsed by, Ms. Ocasio-Cortez. Mr. Adams also endorsed Assemblywoman Inez E. Dickens in Central Harlem in her victorious campaign against another candidate backed by Ms. Ocasio-Cortez.

“The jury is still out on how much endorsements matter, but they do matter for the person being endorsed,” said Olivia Lapeyrolerie, a Democratic political strategist and former aide to Mr. de Blasio. “It’s good to keep your friends close.”

Mr. Adams’s influence is not restricted to his endorsements. Striving for a Better New York, a political action committee run by one of his associates, the Rev. Alfred L. Cockfield II, donated $7,500 to Mr. Tillard in May and more than $12,000 to Mr. Parker through August.

The mayor’s efforts have come under attack. Michael Gianaris, the deputy majority leader in the Senate, said there is no need to create a new faction in the Senate that is reminiscent of the Independent Democratic Conference, a group of breakaway Democrats that allowed Senate Republicans to control the chamber until they were vanquished in 2018.

“Eric Adams was never very good at Senate politics when he was in the Senate,” Mr. Gianaris said. “And apparently he hasn’t gotten much better at it.”

It’s unclear how much influence Mr. Adams’s endorsements will have. Sumathy Kumar, co-chair of the New York City chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America, said that with the mayor’s lukewarm approval ratings, she’s betting that on-the-ground organizing will be the deciding factor in what is expected to be a low turnout primary.

Mr. Parker said the mayor’s endorsement would be influential in his district and supported Mr. Adams’s push against the left wing of the party.

“How many times do you have to be attacked by the D.S.A. before you realize you’re in a fight and decide to fight back?” Mr. Parker said.

Anti-death penalty activists rally outside the U.S. Supreme Court in an attempt to prevent Oklahoma's planned execution of Richard Glossip. (photo: Larry French/Getty Images)

Anti-death penalty activists rally outside the U.S. Supreme Court in an attempt to prevent Oklahoma's planned execution of Richard Glossip. (photo: Larry French/Getty Images)

She was sitting with her husband in the living room of their ranch house on a sprawling piece of creek-side property nestled among Texas live oak trees. The color drained from Garcia’s face. A tear ran down her cheek. What’s wrong? her husband asked. They’d been through a lot in their decades together, but he’d never seen her react like this.

It was 2017, and the face on TV belonged to Justin Sneed, a slight man with gaunt cheeks. Garcia recognized him from 20 years earlier as the thieving, unpredictable maintenance man at a run-down Best Budget Inn on the outskirts of Oklahoma City.

On January 7, 1997, Sneed committed the brutal murder of motel owner Barry Van Treese inside Room 102. Back then, Garcia was working as an escort and dancer at the Vegas Club, a strip club that sat kitty-corner to the motel. She worked a club circuit with a group of women who traveled the country together, performing at venues from California to Oklahoma to Florida. When they were working at the Vegas Club, Garcia and her crew stayed at the Best Budget Inn, which was rife with drug dealing and prostitution.

Conditions had begun to change, however, after Van Treese hired 32-year-old Richard Glossip to manage the motel. “Richard was just a square, quiet-type guy, but hardworking,” Garcia recalled. He’d run off the worst of the drug trade and much of the revolving-door prostitution, though he let Garcia and her friends stick around. And he tried to fix the place up where he could. “He made that place better. He cleaned it up. He had places in the rooms painted. He had the ugliest plaid chairs put in,” she said. “And you could go out to your car at night and get something without being terrified.”

Sneed had come to town as part of a roofing crew from Texas, and Glossip brought him on to do some work around the motel in exchange for a place to stay. Garcia did not like Sneed; he was constantly stealing from motel guests in order to feed his growing drug habit. He fancied himself a pimp and tried to take money from Garcia’s friends. “He was slick. I mean, you turn your back on him, in a second he’ll have his hand in your purse,” she said. By the end of 1996, she recalled, Sneed was always high, often shooting methamphetamine. “He was just nasty with it,” she said. “He wouldn’t be able to find a vein, get mad at his needle, and he’d just throw it. … He disgusted me.”

The week before Van Treese’s murder, Garcia said Sneed was behaving particularly erratically. He’d grabbed one of her girlfriends by the throat, pinning her against a motel room wall. Garcia panicked, pulled a knife on Sneed, and told him to let her friend go. He did. She and her crew packed up and hit the road. They didn’t return until after Van Treese’s murder. When she heard what happened, Garcia’s first thought was that Sneed was responsible. “I said it right away,” she recalled.

What she didn’t expect was that detectives would quickly decide it was Glossip who’d put Sneed up to the crime. Police — and eventually prosecutors — fixated on a narrative that 19-year-old Sneed was merely a hapless dolt whom Glossip had coerced into carrying out a murder-for-hire plot. The motel operated mostly in cash, and Van Treese only came by periodically to collect the receipts and pay the staff. Once Van Treese was dead, the official story went, Glossip had promised to split whatever cash he had on him with Sneed.

To Garcia, this was nonsense. In her experience, Sneed was the dangerous one, aggressive and conniving. She tried to tell the police about him, but they wouldn’t listen. Instead, she said, they threatened her, telling her to keep her mouth shut about what had been going on around the motel or she would face arrest. Garcia, who’d been to prison before, heard the warning and got out of town.

Still, over the intervening years, she regularly thought about Glossip, Sneed, and the murder at the Best Budget Inn. She figured investigators would eventually realize that their suspicion of Glossip was unfounded. But sitting there in her home that night in 2017, the TV flickering in front of her, Garcia realized that hadn’t happened: Instead, Glossip had been charged with Van Treese’s murder and ended up on death row. He’d come close to execution multiple times.

Garcia has faced a lot of challenges in life. She escaped horrific childhood abuse; joined a carnival where she rode a motorcycle inside a metal cage; wrangled alligators and rattlesnakes at a roadside attraction; battled addiction and years of chronic medical problems. But seeing Sneed’s face, and learning of Glossip’s fate, shook her to the core. If only she’d stood up to the cops and told them what she knew about Sneed and the circumstances preceding Van Treese’s murder, she thought, things might have turned out differently. “That was the whole problem,” she said. “Richard would have never been there if us girls had stayed there and just took their bullshit, let them arrest us if they’re going to, and kept telling the truth.”

After seeing Sneed on TV, Garcia reached out to Don Knight, Glossip’s attorney. As it turned out, she was one of dozens of people who had information relevant to the case but were never interviewed by law enforcement. She hoped that her story would be enough to set the record straight. Instead, on July 1, the state of Oklahoma set a fourth execution date for Glossip.

As Glossip’s lawyers fight yet again to save the life of their client, Garcia can’t shake the feeling that she bears some responsibility for his fate. “It is my fault,” she said. “I’ve really been afraid that I’m going to take this to my grave.”’

Things to Clean Up

Since the moment he was arrested in January 1997, Glossip has maintained his innocence for orchestrating the murder of Barry Van Treese. The Intercept was the first national news outlet to dig into his case; an investigation published in July 2015 revealed myriad problems plaguing Glossip’s conviction: a perfunctory and biased police investigation, aggressive prosecutors who cut corners and ignored glaring holes in their theory of the crime, and woefully inadequate defense lawyering that left much of the state’s story unchallenged.

The weakness of the state’s case against Glossip has been well known to the courts for years. Glossip’s original conviction was overturned in 2001 when the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals found that his attorneys had failed to adequately represent him at trial. After a second jury found him guilty in 2004, a federal judge noted that the evidence against Glossip was “not overwhelming” but upheld his conviction anyway.

As Glossip’s fourth execution date approached this summer, his legal team asked the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals to grant them the opportunity to present new evidence that had never been heard in court. This week, Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt ordered a 60-day stay of execution to allow the court to consider their request.

In the meantime, new evidence continues to emerge that bolsters Glossip’s innocence claim. In the past two weeks alone, handwritten letters from Sneed have revealed how close he came to taking back his story about Glossip. In 2003, a year before Glossip’s retrial, Sneed wrote to his public defender, asking, “Do I have the choice of re-canting my testimony at any time during my life, or anything like that.” In 2007, he sent the lawyer another letter: “There are a lot of things right now that are eating at me,” he wrote. Things he needed “to clean up.” Although he didn’t specifically mention recanting, he suggested that he’d made a “mistake.” The lawyer, Gina Walker, who has since died, discouraged him from coming forward.

There has never been any dispute over who actually killed Van Treese. In the early hours of January 7, 1997, Sneed carried a baseball bat and a set of master keys to Room 102, where he attacked the 54-year-old motel owner. Van Treese fought back, Sneed later said, knocking him into a window, which shattered. But Sneed eventually overpowered Van Treese, bludgeoning him to death. Sneed then moved Van Treese’s car to the parking lot of a nearby credit union, taking a stack of cash from under the driver’s seat. Sneed hid his bloody clothes and played dumb the following morning when Van Treese’s family called to say that he hadn’t made it home to Lawton, some 90 miles away. It wasn’t until 10 p.m. that night that Van Treese’s beaten body was discovered inside Room 102 amid a pile of blankets next to the bed. By that time, Sneed had fled the motel.

Oklahoma City Police Detectives Bob Bemo and William Cook headed up the investigation, which was cursory at best. The investigators failed to do even the most basic work, like talking to the numerous people who were staying at the motel at the time of the crime. Instead, they quickly latched on to a half-baked theory that has animated the case for nearly two decades: that Glossip coerced Sneed into murdering Van Treese in order to steal his money and take over the motel.

The cops became suspicious of Glossip in part because he’d failed to give them information that tied Sneed to the murder. The night Van Treese was killed, Glossip said, he was startled awake around 4 a.m. by Sneed knocking on the wall of his apartment, which was adjacent to the motel’s office. Sneed stood outside with a black eye and told him that he’d run off some drunks who had broken a window while fighting in one of the motel rooms. As Sneed was walking away, Glossip said he asked him about his eye and Sneed flippantly responded that he’d killed Van Treese. It wasn’t until the next morning, when no one could find Van Treese, that he realized Sneed might have been serious. Still, he didn’t tell the cops right away — he said his girlfriend had suggested that he wait until they figured out what was happening.

The most glaring problem with the state’s narrative was the lack of any reliable evidence linking Glossip to the murder. The case against him was based almost solely on Sneed’s claim that Glossip had manipulated him into murdering their boss. The reasons to doubt Sneed’s account go beyond the obvious incentive for him to lie in order to escape the harshest punishment. Sneed’s confession was the result of a highly coercive interview led by Bemo, who all but convinced Sneed to blame Glossip. The detective repeatedly named Glossip as a possible conspirator — and even mastermind — before asking Sneed for his version of events.

“Everybody is saying you’re the one that did this, and you did it by yourself, and I don’t believe that,” Bemo told Sneed. “You know Rich is under arrest, don’t you?” No, Sneed said. “So he’s the one,” Bemo replied. “He’s putting it on you the worst.”

Coercion by the detectives who interviewed Sneed would have been crucial exculpatory evidence for Glossip. Yet the videotaped interrogation was never shown to the jurors who sent Glossip to death row. Over the course of two separate trials, lawyers for Glossip failed to use the videotape to show how Sneed’s claims against their client had been concocted with the help of police.

It was only while Glossip faced his second and third execution dates in September 2015 that his case began to attract wider press scrutiny. Up until that point, Glossip had been primarily known as the named plaintiff in a challenge to Oklahoma’s lethal injection protocol, which had reached the U.S. Supreme Court earlier that year. After the justices ruled in Oklahoma’s favor, giving the green light to execute Glossip, The Intercept published its first investigation into the case, followed by a wave of additional coverage. Soon thereafter, new witnesses began to come forward with information casting further doubt on Glossip’s guilt. Two men who had spent time with Sneed in jail separately contacted Glossip’s attorneys to say that Sneed had boasted about killing Van Treese and letting Glossip take the blame. Rather than investigate these claims, Oklahoma County District Attorney David Prater took dramatic measures to silence these witnesses.

Glossip came perilously close to execution in the fall of 2015, spared only by the state’s incompetence in securing the right lethal injection drugs. After it was revealed that Oklahoma had previously carried out an execution using the same erroneous drug it was poised to administer to Glossip, the state’s death penalty ground to a halt. Executions remained on hold for six years.

In the meantime, Glossip’s case continued to attract attention from activists, politicians, and the media. In 2017, documentarian Joe Berlinger released the four-part series “Killing Richard Glossip” — the series that caught Garcia’s attention. Among the major revelations in the documentary was an alternate scenario of the crime. According to a man who spent time with Sneed at the Oklahoma County Jail, Sneed said that he and a woman had lured Van Treese into Room 102 in order to rob him. In other words, this was a robbery gone bad, not a murder for hire.

Glossip’s case also caught the attention of a bipartisan group of Oklahoma lawmakers, many of them rock-ribbed pro-death penalty conservatives, who became concerned that the state planned to kill an innocent man. In May 2021, 34 Oklahoma state legislators, the majority of them Republicans, asked Stitt as well as the state’s Pardon and Parole Board to investigate Glossip’s case. When Stitt and the board failed to act, the lawmakers sought out the law firm Reed Smith LLP, asking for an independent investigation into the case. The firm took on the work pro bono; over the course of four months, 30 attorneys, three investigators, and two paralegals reviewed over 12,000 documents and interviewed more than 36 witnesses. The resulting 343-page report, released in June 2022, contains bombshell revelations that paint the clearest picture to date of Glossip’s wrongful conviction.

“Fundamental concerns and new information revealed by this investigation cast grave doubt as to the integrity of Glossip’s murder conviction and death sentence,” it reads. “The 2004 trial cannot be relied on to support a murder-for-hire conviction. Nor can it provide a basis for the government to take the life of Richard E. Glossip.”

A Grave Error

Much of the report focuses on the shocking investigative failures of the Oklahoma City Police Department in 1997. Among the dozens of people interviewed by Reed Smith’s investigative team were employees or guests staying in one of the 19 rooms occupied at the Best Budget Inn the night of the murder. “The police should have canvassed all of the rooms in the motel to determine if there were any additional witnesses to what occurred,” the report’s authors write. Instead, the cops interviewed just four such people.

Detectives never interviewed Sneed’s roommate, the Reed Smith team found. Nor did they interview a motel housekeeper who said that she overheard Sneed telling someone on the phone that Van Treese was “going to get what he deserved,” nor a woman who reportedly heard glass breaking from outside the motel at the time of the crime.

But the report’s most stunning revelations cut to the heart of the state’s case against Glossip. New details about Van Treese’s finances and the motel’s inner workings undermine the state’s theory of the crime and debunk Glossip’s alleged motive for wanting Van Treese dead.

Underpinning the theory that Glossip compelled Sneed to kill Van Treese in return for half the cash stashed under the motel owner’s car seat was the contention that Glossip’s job was on the ropes. According to the state, Van Treese was upset to discover that Glossip had been embezzling funds from the Best Budget Inn — allegedly totaling about $6,100 in 1996 — and had traveled to Oklahoma City on January 6, 1997, to fire Glossip.

The embezzlement theory appears to have originated with Van Treese’s wife, Donna. At Glossip’s first trial, she testified that the family had returned home from a vacation on January 5, 1997, at which time she prepared a year-end report and discovered a $6,100 shortage for 1996. But oddly, there is no mention of any of this in the police reports — not the shortage calculation or the fact that her husband was planning to fire Glossip as a result. In fact, there is no indication that police ever formally interviewed Donna Van Treese. “The lack of any reporting of this from Ms. Van Treese to the police casts suspicion on the state’s motive theory,” the report reads.

There have always been fundamental problems with the embezzlement narrative, including that Barry Van Treese consistently paid Glossip a bonus for bringing in more revenue per month than had been forecast, which doesn’t square with the notion that any revenue was missing. The Reed Smith report lays out a wealth of additional evidence that there was no verifiable shortage to begin with and that the state peddled this narrative without confirming it. “This ‘embezzlement’ theory should not have been presented to the jury. The prosecution should not have presented a theory it could not verify, and the defense completely fell down in failing to object,” the Reed Smith team wrote. “The jury was told Glossip was stealing from the motel and was going to be fired for it, even though we have found no credible evidence that any of this was, in fact, true.”

At issue was the way in which the Van Treeses handled their motel finances, which appears to have been driven by deep financial problems that neither the jury nor, apparently, the defense knew about. According to the Reed Smith report, Van Treese was heavily in debt to both state and federal taxing entities, and his two motels — the family had a Best Budget Inn in Tulsa as well as the one in Oklahoma City — were mortgaged to the hilt. His accountant, who was never interviewed by police, told the Reed Smith team that the IRS had levied Van Treese’s bank accounts.

Because of the financial problems, which dated back roughly a decade, the Van Treeses had all but abandoned the banking system and were operating almost entirely in cash, much of which was kept in Van Treese’s car. The accountant, Dudley Bowdon, recalled an incident in which Van Treese had paid him for his services from a supply of cash that he kept under his car seat. A receipt for the transaction was recorded on a restaurant napkin.

The state’s core claim that there was a $6,100 shortfall for 1996 — and thus that Glossip had been embezzling money — was calculated by Donna using an improper accounting method, which two forensic accountants say was unreliable and could not be verified. The shortfall was based on Donna’s “business volume” calculations, which were generated by taking an average of the daily room rate — rounded up or down — multiplied by the number of rooms rented. In other words, Donna’s assertion that there was a shortage was based solely on her income projections and not actual revenue. “Over a course of a full year, this could lead to a meaningful discrepancy,” the Reed Smith team wrote. “This methodology of rounding numbers up or down may be an appropriate business forecasting method, but it is not appropriate when attempting to show embezzlement as a motive in a capital murder case.”

What’s more, the team found evidence that Van Treese did not record cash income that was smaller than a $5 bill. As such, Donna’s shortage calculation, “even if accepted,” could be readily explained by Van Treese’s collection habits, the report concluded, “meaning there was no shortage at all.”

Nonetheless, the court allowed Donna’s assertions to stand — even though doing so appears to have violated Oklahoma law, which requires that underlying financial records be admitted into evidence. The majority of those records weren’t available though. Some had been lost in a flooding event at the Van Treese home, Donna testified. And others had been destroyed by the state.

The report also sheds light on astonishing mishandling of evidence in the case. “Police appear to have lost a surveillance video tape showing the night of the murder from the Sinclair Gas Station which was within walking distance from the Best Budget Inn,” it reads. Sneed went to the gas station around the time of the murder; the tape could have provided evidence to support or contradict his story. As the report points out, the surveillance footage could have also revealed whether or not Sneed was by himself.

Even worse was the willful destruction of key evidence prior to Glossip’s second trial. Although records show the official reason given by the DA’s office for destroying this evidence was that Glossip’s appeals had been exhausted, this was far from the truth. Retired prosecutor Gary Ackley, who assisted the lead prosecutor at Glossip’s retrial, told investigators that the DA’s office “had a long-standing agreement with the Oklahoma City Police Department to never destroy evidence in a capital murder case.”

Yet Reed Smith interviewed several career Oklahoma City law enforcement officers who described how prosecutors explicitly requested that evidence be destroyed in 1999, in contravention of the office’s own policy. Not only did prosecutors ask police to destroy a box of evidence in Glossip’s case, but the DA’s office also created a new case number “solely for this destruction of this box of evidence,” according to one detective who previously worked in the police crime lab. Ordinarily, the original case number would be used. This conduct was clearly aberrant and unnerving to those interviewed by Reed Smith. One law enforcement officer said it was “not the way it’s supposed to be done.” Ackley was especially blunt. “The Glossip deal horrifies me,” he said. “I have no idea how something like this could happen.”

The box destroyed in 1999 contained 10 items, eight of which Reed Smith identified as being especially important to Glossip’s defense. They included handwritten accounting logbooks that Van Treese kept in his car — a deposit book containing the motel’s financial records and two receipt books containing the motel’s expenses. As the report makes clear, these were “the very financial records … that Glossip would need to definitely disprove there was embezzlement.”

Other destroyed evidence included items recovered from the crime scene that had obvious forensic value, including a shower curtain Sneed used to cover the broken window in Room 102, a roll of duct tape he used to hang the shower curtain, and a wallet that, according to Sneed, had been handled by Glossip yet was never tested for fingerprints. Finally, there were items whose descriptions were vague enough to leave the question of their evidentiary value unanswered, such as an envelope with a note and a “white box with papers.”

It is not clear what these items might have revealed had they been preserved as required. What is clear is that “Glossip did not have any of this evidence for his retrial or any of his post-conviction efforts,” the report emphasizes.

“The state should not be absolved from how grave of an error this is,” the Reed Smith team concluded. “The state’s destruction of evidence is … inexcusable in a capital murder case.”

A Significant Threat

And then there is Justin Sneed.

To hear the state tell it, Sneed was simply too clueless to have orchestrated the murder of Van Treese on his own, notwithstanding the savagery of his actions on January 7. But the Reed Smith investigation makes clear not only that Sneed was far savvier than the prosecution made him out to be, but also that the state had evidence of this in its possession long before Glossip was ever tried.

And there were other signs that should have raised red flags — including Sneed’s shifting story about the money Glossip allegedly promised to pay him.

Sneed gave various accounts of how much Glossip offered him for the murder but eventually landed on $4,000, which Glossip allegedly told him would be found under Van Treese’s car seat. Sneed said that he was given around $2,000. When Glossip was arrested on January 9, he had $1,757 on him — proof, as the prosecution would have it, that Sneed’s story made sense. In accepting this at face value, however, the prosecution dismissed key information. First, according to Glossip, his money had come from his paycheck as well as the proceeds from selling several personal items, which he did, he said, in order to hire an attorney to help him deal with the cops. Glossip said that after he was first questioned by police, a friend warned him not to speak to them again without representation; Glossip was ultimately arrested upon exiting the office of an Oklahoma City attorney.

There was no physical evidence linking Glossip’s money to the murder. There was no blood on it, as there was on bills Sneed had in his possession, and there were no similar serial numbers or denominations among the two pots of cash.

And there was an even bigger problem, Reed Smith found, which further discredited Sneed’s story about splitting money with Glossip. Records reflect that the total receipts collected by Van Treese from the motel that week amounted to less than $3,000. One forensic accountant estimated that the amount of cash Van Treese would have collected was actually closer to $2,000, which would account only for the money in Sneed’s possession.

Ruling on Glossip’s appeal of his second conviction, the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals pointed to the alleged money split as critical evidence backing Sneed’s version of the murder plot. “The most compelling corroborative evidence, in a light most favorable to the state, is the discovery of money in Glossip’s possession,” the court wrote.

The court accepted the notion that were it not for Glossip, Sneed wouldn’t have known about the money in Van Treese’s car. This too was wrong. “He always kept money,” Garcia said of Van Treese. It was common knowledge among the motel regulars, including Sneed, who Garcia said had been agitating to steal from Van Treese for a while — including by trying to get one of her fellow dancers to help out. “I guarantee it,” she said. “It was talked about.” She said she made it clear to her friends that they should not mess with Van Treese; she let them know that “if they had anything to do with that,” they’d “never work another night in any club I was in.”

She said Sneed was constantly in search of money to feed his drug habit and recalled one particularly chilling incident: After complaining about not having money for drugs, Sneed picked up a brick and wandered off. Later, he returned with about $500 and blood on his shirt. Others who were hanging around the motel recalled similar interactions with Sneed. Jamie Spann, who worked at the roofing company with Sneed and shared a room with him at the Best Budget Inn, said in an affidavit that Sneed regularly stole items from other roofers and that he’d seen him steal from one of the houses they were working on. He said that Sneed walked around the motel like he “owned” the place and “wanted everyone to pay him to sell drugs.” He said Sneed wanted those engaging in sex work at the motel to split their profits with him — an allegation that Garcia has also made against Sneed.

None of these behavioral problems were new. Spann had known Sneed since childhood and said he’d been a manipulative “bully type.” Sneed was frequently in trouble for fighting and mouthing off, the Reed Smith team found. In fact, although prosecutors portrayed him as guileless for the jury, Sneed’s troubling history was known to the state prior to Glossip’s first trial. In a competency report provided to the state in 1997, a forensic psychologist found that if Sneed were to be released without “treatment, therapy, or training,” he would “pose a significant threat to the life or safety” of himself or others.

The report, which was completed before Sneed pleaded guilty and agreed to testify against Glossip, also noted that Sneed had a criminal history in Texas — including for burglarizing a house and making a bomb threat against a friend’s school. Sneed explained away each incident by claiming that someone else had forced his hand.

Where the murder of Van Treese is concerned, Sneed has never been able to keep his story straight. His testimony from Glossip’s first trial morphed significantly by the time he testified again in 2004 — roughly a year after he’d asked his lawyer if he could recant — incorporating additional details he’d never told police that were not supported by any evidence. All of this should have raised concern for the state. Instead, prosecutor Connie Smothermon told the jury that such inconsistencies could be explained by the fact that she was simply better at asking questions than her predecessor on the case. “I’m not going to apologize for asking more questions than anybody else did before,” she said, “because, you know, that’s me, I’m a questioner.”

When questioned about the crime in recent years, Sneed has continued to give inconsistent answers. In a 2015 interview with The Frontier, he made the bizarre claim that he had no idea why Glossip would’ve wanted Van Treese dead. The Intercept sent Sneed an email asking about the letters he wrote indicating that he wanted to recant his testimony. He did not respond.

A Haunting Experience

Since Glossip last faced execution in 2015, numerous witnesses in addition to Garcia have come forward to share what they knew with his legal team. Their accounts are contained in a flurry of affidavits that consistently portray Sneed as violent and cunning.

“I was shocked to hear that anyone had tried to portray him as someone who is slow, or could be manipulated by anyone, let alone Richard Glossip,” said one man who used to sell drugs at the Best Budget Inn. A roofer who briefly lived with Sneed at an Oklahoma City apartment said that after the murder took place, Sneed returned to the house acting strange. He had a black eye and was “really nervous,” refusing to leave the house and looking out the window a lot. A different roommate eventually saw Sneed on TV and turned him in, according to the affidavit, yet “no one from the defense or the prosecution ever came to talk to me about this.”

Perhaps the most damning accounts come from people who were once incarcerated with Sneed. Among them is Paul Melton, who spent 13 months with him at the Oklahoma County Jail starting in March 1997.

Melton remembers feeling concerned for Sneed at first. “I kind of felt bad for him when I first met him because he was green to prison life, to jail,” he said. “In Oklahoma, that’s very dangerous.” It’s not that Sneed was naïve, exactly. In fact, he was a “hustler” who made money selling cigarettes to his neighbors. But at the same time, “Justin wouldn’t shut his mouth,” Melton said. He would talk openly about his case in a way that was reckless. He remembered telling Sneed, “Everything you’re doing right now is going to follow you to prison, so you better shut your mouth.”

As Melton recalls it, Sneed was clear from the start that he had killed Van Treese on his own. But he also corroborated the account introduced in “Killing Richard Glossip,” in which Sneed and a woman had lured Van Treese to Room 102 as part of a plan to rob him. Melton said this was something Sneed had done a number of times to motel guests. Unlike their previous targets, Van Treese fought back, escalating the confrontation until Sneed killed him. “Justin Sneed and a girl set this up, and it was a robbery went south,” Melton said.

Garcia also recalled Sneed targeting motel guests this way. “Sneed would use some of the girls who worked at the club to lure men into the rooms so he could set the men up and rob them,” she said in a 2018 affidavit. Both she and Melton described one such woman as Sneed’s girlfriend, but Garcia also said that Van Treese was her “sugar daddy,” giving her gifts and money. Garcia, who worked with the woman, said the police knew about Van Treese’s proclivities but wanted her to keep quiet about it. This is why they never listened to her about Sneed and instead threatened to arrest her if she talked. “If I go saying that Barry was a sugar daddy and I’m running a prostitution ring, I’m going back to prison for a very long time,” Garcia said she was told.

Melton was in jail with Sneed when he cut his deal with the Oklahoma City DA’s office. As he recalls, Sneed laughed about the fact that Glossip would get the death penalty instead of him. “And that’s what stuck with me. He thought it was funny.”

Others who spent time in jail with Sneed were similarly bothered by his boasting about setting up Glossip. At least one tried to tell the state about it long before Glossip went to death row. In May 1997, a letter arrived at the office of then-Oklahoma County DA Robert Macy, from a man who had recently spent time in the county jail. That man, Fred McFadden, had contacted Macy at least once before to share “an experience that truly haunts me.” While in jail, McFadden heard Sneed bragging openly about what he had done to Glossip. At the time, he was sitting at a table along with another man. “He and I were both so disgusted we got up from the table and walked around the pod,” McFadden wrote. “It quite frankly angered both of us.”

In his May 1997 letter, McFadden shared the name of the other man with Macy. But there’s no evidence that the DA followed up on the tip. Instead, prosecutors continued their case against Glossip, sending him to death row the following year.

McFadden died in 2015. Melton did not want to carry what he knew to his grave. When Glossip’s legal team contacted him asking if he’d spent time in the Oklahoma County Jail in 1997, he agreed to speak to them — even though he feared retaliation from Oklahoma authorities. Like Garcia, he feels deep guilt over his failure to share what he knew about Sneed years ago. He broke down in tears during multiple phone calls, expressing anguish and regret that he’d ever met Sneed. “I am not OK with an innocent man being murdered,” he said. “And I know [Glossip] was set up because the murderer told me.”

A Starbucks barista. (photo: USA TODAY)

A Starbucks barista. (photo: USA TODAY)

As hundreds of Starbucks locations across the U.S. vote to unionize, one store’s workers were suspended over claims they tried to kidnap their manager while asking for a pay raise.

The incident, which took place on Aug. 1, was manager Melissa Morris’s first day working at the Anderson Starbucks store.

She was walking into a volatile situation. Like many Starbucks workers across the country, baristas at the store had become increasingly dissatisfied.

“We were tired of how management was treating us, not listening to our complaints,” says Aneil Tripathi, 19, who took his first ever job in the Anderson store and led the unionization effort. “They haven’t stepped a foot on the floor, they probably never made a drink in their life. And they’re telling us how to do our jobs.”

Tripathi recalled how on one particularly busy Sunday he found the store understaffed—three people were doing the job of six. He called the district manager for help. It was her day off and he could hear the TV on in the background. “There’s not much I can do,” she told him. That day he sent an email to Starbucks Workers United—an independent labor union that has been organizing workers nationwide—asking for advice on how to unionize the store.

The unionization campaign at the Anderson store was a wild success. The May 31 vote was unanimous, with all 18 workers voting to join. “It was kind of a big deal,” Tripathi says, because northern South Carolina is very pro-Trump and historically anti-union.

In response to the vote, workers say, management cracked down on the Anderson store. They were told they couldn’t wear pro-union T-shirts and management started unilaterally cutting their hours, as well as shortening the store’s opening times.

Starbucks has been scrambling to respond to a wave of stores unionizing nationwide. In an effort to stem the flow, the company announced on May 3 that it would roll out a new packet of benefits on Aug. 1 but there was a catch. Workers at unionized stores would not be eligible for the new perks. Instead, each would have to negotiate their own contract individually.

The Anderson baristas had gone out on strike twice last month but this edict was the final straw.

“Our store was very frustrated,” said Tripathi. The baristas reacted angrily to news they would be excluded from the very benefits they had been demanding and felt like it was retaliation for organizing.

So they began to plan a “March on the Boss,” a federally protected direct action in which workers present their demands directly to their manager. They drafted a letter asking for new equipment for the store and demanding that they receive the same pay raise being given to non-unionized stores.

They planned to take action on Aug. 1—the day the new benefits were rolled out.

Originally, the Anderson workers had planned to confront their store manager, but she quit after the first strike. Their new manager, Melissa Morris, started Aug. 1.

“Unfortunately for her that was the day it fell on,” says Tripathi.

The workers gathered around Morris and read their letter aloud.

“We are not going to move until some action is taken for our raise. No work is being done on the floor, and no customers are being served,” one worker told Morris, in audio published by More Perfect Union on Twitter.

“We carried this company on our shoulders through the pandemic at the risk of our health and loved ones’ health,” another worker tells Morris in the recording, “and we have nothing to show for it.”

“We weren’t menacing,” says Tripathi, “We were a good distance away from her.”

Video of the incident, released by Starbucks Workers United, shows Morris sitting at a table in the store, surrounded by 10 workers, while another employee films the situation. While speaking to the district manager on the phone, Morris stands up, brushes past one of the workers, and stops before reaching the door. Workers followed her to the door, but did not block her path, Tripathi says.

“No one was blocking the door,” he told The Daily Beast. “The door was unlocked.”

“Will you let me exit the building?” Morris asks the workers, still on the phone.

“Yes,” Tripathi answered.

The entire interaction lasted around six minutes, according to audio of the incident.

Two days later, Morris filed a report with the Anderson County Sheriff’s Office alleging that her employees had kidnapped her at the store, and “would not let her leave until they got a raise.”

“One employee also assaulted her,” Morris told police, and the incident was “captured on video,” according to a police report viewed by The Daily Beast.

Morris was not immediately available for comment.

Police came to the store and interviewed workers about the kidnapping allegation.

“They saw that we’re not criminals, we’re people who make coffee,” Tripathi says.

On Aug. 6, Tripathi and 10 other workers at the store found out they were being suspended.

The store manager “felt threatened and unsafe as a result of conduct by 11 store partners,” Starbucks said in a statement, adding that they had been advised by law enforcement to suspend workers “until their investigation is complete.”

“They want to make an example out of us,” says Tripathi, who sees the suspension as direct retaliation for organizing.

The Anderson County Sheriff’s Office said a detective is still investigating the case and it has not been determined yet if charges will be filed.

“Bossnapping,” or taking your boss hostage during a labor dispute is an unusual tactic, but occurs occasionally in France, where workers have been known to kidnap their employers for several days. The strategy is unknown in the United States.

“I cannot believe I have to say this, but workers who are organizing for better working conditions should not have to deal with their boss accusing them of kidnapping and assault,” Senator Bernie Sanders tweeted on Aug. 8, “How outrageous. This campaign of rampant union-busting from Starbucks has got to end.”

The kidnapping charge is just the latest example of Starbucks’s aggressive response to union organizing by its workers since the campaign began in Buffalo, New York, in 2021. To date, 223 Starbucks stores have voted to unionize.

Tripathi believes Morris filed the police report on the advice of Starbucks management, who are being counseled by Littler Mendelson—the high-powered law firm Starbucks has brought in to help them.

The firm, which has also represented Apple and Trader Joes, is notorious for its aggressive union-busting tactics.

To date, Starbucks has fired over 85 pro-union workers at stores across the country, according to Starbucks Workers United, who also say the company is engaged in underhand, illegal anti-union tactics, including spreading disinformation, closing stores, intimidating workers, retaliating against those who organize, and attempting to halt elections.

On Thursday, the National Labor Relations Board, the federal body that adjudicates disputes between unions and management, found that Starbucks had violated the law when they fired seven union-involved baristas in Memphis, Tennessee. A judge ordered Starbucks to reinstate the workers and to “cease and desist from unlawful activities.” Starbucks said it disagrees with the verdict and plans to appeal, according to a statement posted to their website.

The union has filed 291 unfair labor practice charges with the NLRB against Starbucks since their organizing campaign began. The Board has already found merit in 87 of these allegations, accusing Starbucks of illegally interfering with and coercing workers, and taking retaliatory action against organizers.

But it may take months or even years for the Board to wade through all the complaints, and their enforcement power is limited.

“It really is kind of an amazing anti-union crime wave from this company that professes to be a progressive employer and to care about its people,” says John Logan, a professor and director of labor and employment studies at San Francisco State. Logan believes the harsh tactics Starbucks is employing are part of Littler Mendelson’s anti-union playbook.

“Hiring Littler Mendelson is like planting a flag and saying: we’re going to fight this union to the death,” Logan says, “It has unlimited resources with which to fight this campaign.”

Littler Mendelson, founded in 1942, has grown into an enormous international firm, employing thousands of lawyers across the world. The firm specializes in union-avoidance. It made more than $658 million in gross annual revenue in 2021, according to its website. In June, the firm handed out average bonuses of $10,000 to high-performing employees, according to the legal blog Above The Law.

At least 50 Littler Mendelson lawyers, spread across 17 states, have been working for Starbucks in just the last three months, according to a Daily Beast review of NLRB filings since June 2022. At least three of these lawyers are also representing Trader Joes, which is engaged in its own battle against unionization efforts at its stores.

“It might be the most expensive anti-union campaign of all time,” Logan says.

On Friday, Starbucks workers at stores on North Broadway in Chicago, and in Clifton Park, New York, voted overwhelmingly in favor of unionizing, while a vote at a separate location in Louisville, Kentucky, was much closer with 10 people voting yes, 7 voting no, and 3 ballots being challenged.

Starbucks CEO, billionaire Howard Schultz has taken an active role in anti-union efforts, blaming outside agitators for stoking resentment among employees. Last month, he told a New York Times event that he could not accept a future for the company with a union involved, “because we have a different view.”

In Schultz’s 1999 memoir, Pour Your Heart Into It: How Starbucks Built a Company One Cup at a Time, Schultz recalls watching unionization efforts at Starbucks in the late 1980s.

“There is no more precious commodity than the relationship of trust and confidence a company has with its employees,” he wrote, “Once they start distrusting management, the company’s future is compromised.”

A march in Mexico City on the anniversary of the disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa, Guerrero. (photo: Keith Dannemiller)

A march in Mexico City on the anniversary of the disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa, Guerrero. (photo: Keith Dannemiller)

Head of commission said disappearance of students was a ‘state crime’ involving officials from all levels of government.

The mass disappearance of the students sparked international outrage over impunity in Mexico, and did lasting damage to the administration of then-President Enrique Pena Nieto, particularly as international human rights experts criticised the official inquiry as riddled with errors and abuses.

Mexico’s top human rights official, Alejandro Encinas, made a rare official acknowledgement on Thursday that the students did not survive.

Encinas told a news conference that government involvement in the disappearance – including local, state and federal officials – constituted a “state crime”.

“Their actions, omissions or participation allowed the disappearance and execution of the students, as well as the murder of six other people,” said Encinas, who is heading the commission and is also deputy interior minister.

“There is no indication the students are alive. All the testimonies and evidence prove that they were cunningly killed and disappeared,” he said.

“It’s a sad reality.”

Despite extensive searches, the remains of only three students have been discovered and identified, Encinas said.

Missing students

The students, from a rural teachers’ college, went missing after they had commandeered buses in the southern state of Guerrero to travel to a demonstration.

Encinas said the army was responsible at least for not stopping the abductions because a soldier had infiltrated the student group and the army knew what was happening at the time.

According to an official report presented in 2015 by the government of Pena Nieto, the students were arrested by corrupt police and handed over to a drug cartel.

The cartel mistook the students for members of a rival gang and killed them before incinerating and dumping their remains, according to that report, which did not attribute responsibility to the military.

Those conclusions were rejected by relatives as well as independent experts and the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Encinas said that further investigations were necessary to establish the extent of participation by army and navy personnel.

“An action of an institutional nature was not proven, but there was clear responsibility of members” of the armed forces stationed in the area at the time, he said.

The defence ministry did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Drug trafficking ties

Encinas also revived the hypothesis that the origin of the abductions was tied to the region’s active drug trafficking.

He said a bus that night had passed through 16 federal security checkpoints without being stopped, despite intercepted communications discussing “merchandise” that it was carrying.

“And the merchandise is either drugs or money,” he said.

A 2016 investigation by independent experts found that federal police had taken students off the so-called “fifth bus” and then escorted the bus out of the town of Iguala in Guerrero state. Investigators suspect the bus was part of a heroin trafficking route from the mountains of Guerrero to Chicago and that the students had unknowingly hijacked it and its illicit cargo, triggering the events that followed.

The families of the disappeared have kept up pressure on the government over the years, demanding the investigation be kept open and expanded to include the military, which has a large base in Iguala yet did not intervene.

Mexico’s President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador said in March that members of the navy were under investigation for allegedly tampering with evidence, notably at a rubbish dump where human remains were found, including those of the only three students identified so far.

He denied an accusation by independent experts that Mexican authorities were withholding important information about the case, which shocked the country and drew international condemnation.

Trina Sherwood, a cultural specialist for the Yakama Nation's Environmental Restoration and Waste Management Program, during a trip to collect data on the Umtanum desert buckwheat. (photo: Jovelle Tamayo/Guardian UK)

Trina Sherwood, a cultural specialist for the Yakama Nation's Environmental Restoration and Waste Management Program, during a trip to collect data on the Umtanum desert buckwheat. (photo: Jovelle Tamayo/Guardian UK)

A generation after it was decommissioned, tribal members are still working to clean up the Hanford nuclear site, one of the most contaminated spots in the US

It also sits on the ancestral lands of the Yakama Nation and other Indigenous peoples in Washington state. Here, precious wildlife, vision quest sites and burial grounds lie side-by-side with signs reading “warning hazardous area” and towering nuclear reactors, some of which date back to the second world war.

There’s Gable Mountain, where young men would fast and pray, explained Sherwood, a cultural specialist for the Yakama Nation’s Environmental Restoration/Waste Management (ER/WM) program. There’s Locke Island, where an Indigenous village once stood, and the towering White Bluffs, where Native people collected white paint for ceremonies. There are also outcroppings of tules, which were used to make mats for ceremonies and tipis, as well as yarrow root, which was known to treat burns.

The Hanford nuclear site was established in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project, and over the next four decades produced nearly two-thirds of the plutonium for the US’s nuclear weapons supply, including the bomb dropped on Nagasaki.

During its lifespan, hundreds of billions of gallons of liquid waste were dumped in underground storage tanks or simply straight into the ground. After the site’s nine nuclear reactors were shut down by 1987, about 56m gallons of radioactive waste were left behind in 177 large underground tanks – two of which are currently leaking – alongside a deeply scarred landscape.

In the decades since, the Yakama Nation has been one of four local Indigenous communities dedicated to the cleanup of this historic landscape. For the Yakama Nation, that has meant tireless environmental and cultural oversight, advocacy and outreach with the hope that one day the site will be restored to its natural state, opening the doors to a long-awaited, unencumbered homecoming.

Today, their outreach work has reached a fever pitch. There are few Yakama Nation elders still alive who remember the area before its transformation, and there are likely decades to go before cleanup is complete. So members are racing to pass on the site’s history to the next generation, in the hopes they can one day take over.

“Our elders are leaving that have that historical knowledge; people that actually lived there during that time and can tell you stories about the area,” said Laurene Contreras, administrator for ER/WM, the program responsible for the Yakama Nation’s Hanford work. “That’s why it’s so important for us to make sure that we’re carrying that message forward.”

‘Religious and moral duty’

Yakama Nation history on the Hanford site dates back to pre-colonization, when people would spend the winter here fishing for sturgeon, salmon and lamprey in the Columbia River, as well as gathering and trading with other families. In 1855, the Nation ceded over 11m acres of land to the US, which included the Hanford area, and signed a treaty that relegated them to a reservation while allowing the right to continue fishing, hunting, and gathering roots and berries at “all usual and accustomed places”.

But in the 1940’s, the situation shifted dramatically when the area was cleared out to make room for the construction of nuclear reactors.

LaRena Sohappy, 83, vice-chairwoman for Yakama Nation General Council, whose father was a well-known medicine man, grew up in Wapato, about 40 miles from Hanford. She said she remembers the strawberry fields that lined the Hanford site, her family gathering Skolkol, a root and daily food, and traveling to the area for ceremonies.

Her cousin’s family who lived close to Hanford were woken in the middle of the night and forced to leave to make way for the nuclear site, she recalled

“They didn’t have time to pack up anything,” said Sohappy. “They just had to leave and they were never told why and how long they were going to be gone.”

The effort to give Indigenous people a voice in Hanford’s fate was forged in part by Russell Jim, a member of Yakama Nation’s council, whose work has been credited with helping to keep Hanford from becoming a permanent “deep geologic repository”, a place where high-level nuclear waste from this site and others across the country would be stored.

“From time immemorial we have known a special relationship with Mother Earth,” Jim, who died in 2018, said in a statement to the US Senate in 1980. “We have a religious and moral duty to help protect Mother Earth from acts which may be a detriment to generations of all mankind.”

Today, the ER/WM program, which was founded in the early 1980’s with Jim at the helm, includes such staff as a biologist, ecologist and archeologist. It’s funded by the US Department of Energy (DoE), which operates the Hanford site and leads the cleanup process under an agreement with the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Washington state department of ecology.

The Yakama Nation program’s focus is on accelerating a thorough cleanup of the site, protecting culturally significant resources and assessing the threats to wildlife and water.

The area around Hanford is considered the last free-flowing section of the Columbia River. There’s a major spawning site for Chinook salmon, and all along this section of the waterway, sturgeon live all year round, explained Phil Rigdon, Yakama Nation acting Tribal Administrative Director.

“Our people, we’re fish people, we’re salmon people in the Columbia River … So for us, that was a priority,” he said.

Chemicals including mercury, which can damage the brain, kidneys and heart, and PCBs, which can cause cancer, have been found in the river and could be ingested when eating fish, according to a 2017 advisory. For the Hanford Reach, a 150-mile section of the river that runs through Hanford, it suggests limiting consuming some fish to four or fewer times a month.

In the past decade, it was also discovered that hundreds of gallons of highly radioactive waste have been leaking from two Hanford tanks, threatening the Columbia River.

McClure Tosch, a Natural Resource Injury Assessment lead for ER/WM, said recently Yakama Nation has played a key role in developing a plan for the EPA to monitor the basin, including fish tissue.

ER/WM has also been advocating for the federal government to test the wells at Hanford near the Columbia River for PFAS, long-lasting chemicals that can be found in an array of commercial and industrial products. If found, Tosch said, that could be a huge concern for the local drinking water. The energy department said in a statement: “Information-gathering about the occurrence and use of PFAS at DoE sites is ongoing”.

There has also been a focus by the Yakama Nation to preserve culturally significant plants. Most recently, Sherwood has been overseeing the protection of a bright yellow plant known as Umtanum desert buckwheat. It has long been known as a medicinal plant for the local Indigenous people, and today, Hanford is the only place in the world where it is documented as growing.

A ‘push and pull’ effect

Despite the sometimes glacial nature of the federal government’s work, the Yakama Nation have scored some important wins.

Recently, the ER/WM succeeded in amending a cleanup proposal for an area next to the Columbia River containing nuclear reactors, ensuring it will include a review of the impact on local aquatic insects. And in the coming months, Tosch says the tribe will work with the federal government to assess the effectiveness of a polyphosphate injection to sequester uranium found in Hanford’s groundwater; an approach the tribe has questioned.

ER/WM staff have also pushed back against a federal government change in how high-level radioactive waste is classified, which could downgrade some of Hanford’s waste, ultimately preventing it from being removed from the site as expected. The energy department said they don’t plan to move forward with this new interpretation without first meeting with local Indigenous Nations.

For their part, both DoE and EPA said their representatives meet with Yakama Nation regularly about Hanford and have benefitted from their’s and other local Indigenous Nations’ expertise and input.

But Brian Stickney, DoE’s deputy manager for the Hanford Site, said in a statement that while Yakama Nation wants to see the lands returned to a pre-nuclear state, DoE is focused on regulatory requirements and protecting treaty rights.

The Washington state department of ecology, which helps to oversee the Hanford cleanup and whose officials meet with the Yakama Nation at least once a month, described their relationship with the tribal Nation as a bit “push and pull”.

“We are the regulators, and sometimes Yakama Nation would like us to push a little harder than they perceive us doing,” said Laura Watson, its director. “And so there’s a little bit of that push and pull. And that’s fine, that’s actually important as a regulator to have folks pushing.”

‘For our children not yet born’

A fully rehabilitated Hanford site likely won’t happen within the lifetime of Yakama Nation’s elders, or even the generation that follows. So, they’re working diligently to bring in younger tribal members to the effort.

In recent years, they’ve held coloring contests, a mass postcard mailing campaign and visited local schools, explained Samantha Redheart, who coordinates Stem programs for ER/WM. They’ve also offered college scholarships for students studying such subjects as engineering and science in the hopes that the recipients may one day bring that knowledge back to the community.

“We always share that Hanford is a multi-generational cleanup site,” she said. “Yakama Nation leaders and management are always looking into not just the cleanup today, but for our future generations and of our children that are not yet born.”

22 high school students were allowed to visit Hanford in 2016 - a rare opportunity, explains Redheart, as those under 16 are typically not allowed on most of the site. She said they took them to a series of culturally important sites, pointing out traditional cultural artifacts and salmon spawning grounds. But the experience was thoroughly regimented, involving energy department staff, hazmat guides and strict timelines.

If Sohappy had her way, sharing her knowledge of Hanford before it was a nuclear site with the next generation would involve something of a trip back in time. She would take them on wagons and horses to each of the important sites, making sure to point out where the strawberry fields and old town once stood.

It’s difficult to know whether that will ever be a reality. She herself hasn’t been to Hanford in over a decade.

“It angers me that I can’t go where my dad used to wander around,” she says. “There’s nothing there that’s pleasurable. Not anymore anyway. It’s all torn up.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.