We have always said we never cut off any subscriber for not paying or donating and we don’t. But the service providers that keep RSN up and running are not so understanding.

To keep the process going some money is required.

Do what you can.

Marc Ash

Founder, Reader Supported News

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Noam Chomsky spoke with The Intercept’s Jeremy Scahill in a wide-ranging discussion on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

On Sunday, in an interview on NBC, national security adviser Jake Sullivan cast the war not just as a defense of Ukraine but also an opportunity to deliver significant blows to the stability of the Russian state. “At the end of the day, what we want to see is a free and independent Ukraine, a weakened and isolated Russia, and a stronger, more unified, more determined West,” he said. “We believe that all three of those objectives are in sight, can be accomplished.”

As Ukraine and its Western allies accuse Russian forces of heinous war crimes and crimes against humanity, including massacres of large numbers of civilians, Putin’s government and media apparatus is waging an all-out campaign to denounce the allegations as lies and fake news.

Biden has officially accused Putin of war crimes and suggested he should face a “war crime trial.” Russia, like the U.S., has steadfastly refused to ratify the treaty establishing the International Criminal Court, so it is unclear how or where the administration believes such a trial would take place.

This week, renowned dissident and linguist Noam Chomsky joined me for a wide-ranging discussion on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, holding the powerful accountable, the role of media and propaganda in war, and what Chomsky believes is necessary to end the bloodshed in Ukraine.

Jeremy Scahill: Thank you very much for joining us here at The Intercept for this discussion with Professor Noam Chomsky.

We’re going to be discussing today, the Russian government’s invasion of Ukraine, the horrors that we’ve seen coming out of Ukraine, the bloodshed, the massacres, the killings.

But also we are witnessing a major assertion of power by the United States in Europe, calls for expanding U.S. militarism in Europe, European governments pledging to spend more money on weapons systems and to increase their activities as arms brokers. The United States, at present, is the largest weapons dealer in the world.

At the same time, our guests Noam Chomsky says that this was an act of aggression, state-sponsored act of aggression, that belongs in the history books alongside the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, as well as the 1939 invasion of Poland by both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany.

I want to welcome Professor Noam Chomsky to this forum here on The Intercept. Noam, thank you very much for being with us.

Noam Chomsky: Pleased to be with you.

JS: I want to start because there’s been a lot of discussion on the left in the United States among anti-war activists on how to make sense of what a just response would look like to Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine and the mass killing that we are seeing. We can take time to talk about the broader historical context, and you’ve been discussing this a lot in other interviews, but I want to just start by asking you, is there any aspect of the U.S., NATO, and European Union response to this invasion that you believe is just: the weapons transfers to Ukraine, the sweeping economic sanctions and attempts to entirely isolate not only Russia and Putin, but ordinary Russians? Is there any aspect of the government response to this by the U.S., NATO or the European Union that you agree with?

NC: I think that support for Ukraine’s effort to defend itself is legitimate. If it is, of course, it has to be carefully scaled, so that it actually improves their situation and doesn’t escalate the conflict, to lead to destruction of Ukraine and possibly beyond sanctions against the aggressor, or appropriate just as sanctions against Washington would have been appropriate when it invaded Iraq, or Afghanistan, or many other cases. Of course, that’s unthinkable given U.S. power and, in fact, the first few times it has been done — the one time it has been done — the U.S. simply shrugged its shoulders and escalated the conflict. That was in Nicaragua ,when the U.S. was brought to the World Court, condemned for unlawful use of force or to pay reparations, responded by escalating the conflict. So it’s unthinkable in the case of the U.S., but it would be appropriate.

However, I still think it’s not quite the right question. The right question is: What is the best thing to do to save Ukraine from a grim fate, from further destruction? And that’s to move towards a negotiated settlement.

There are some simple facts that aren’t really controversial. There are two ways for a war to end: One way is for one side or the other to be basically destroyed. And the Russians are not going to be destroyed. So that means one way is for Ukraine to be destroyed.

The other way is some negotiated settlement. If there’s a third way, no one’s ever figured it out. So what we should be doing is devoting all the things you mentioned, if properly shaped, but primarily moving towards a possible negotiated settlement that will save Ukrainians from further disaster. That should be the prime focus.

That requires that we can’t look into the minds of Vladimir Putin and the small clique around him; we can speculate, but can’t do much about it. We can, however, look at the United States and we can see that our explicit policy — explicit — is rejection of any form of negotiations. The explicit policy goes way back, but it was given a definitive form in September 2021 in the September 1 joint policy statement that was then reiterated and expanded in the November 10 charter of agreement.

And if you look at what it says, it basically says no negotiations. What it says is it calls for Ukraine to move towards what they called an enhanced program for entering NATO, which kills negotiations; — this is before the invasion notice — an increase in the dispatch of advanced weapons to Ukraine, more military training, the joint military exercises, weapons placed on the border. We can’t be sure, but it’s possible that these strong statements may have been a factor in leading Putin and his circle to move from warning to direct invasion. We don’t know. But as long as that policy is guiding the United States, it’s basically saying, to quote Ambassador Chas Freeman, it’s saying: Let’s fight to the last Ukrainian. [That’s] basically, what it amounts to.

So the questions you raised are important, interesting, just what is the appropriate kind of military aid to give Ukrainians defending themselves enough to defend themselves, but not to lead to an escalation that will just simply lead to massive destruction? And what kinds of sanctions or other actions could be effective in deterring the aggressors? Those are all important, but they pale into insignificance in comparison with the primary need to move towards a negotiated settlement, which is the only alternative to destruction of Ukraine, which of course, Russia is capable of carrying out.

JS: You know, it’s interesting because Volodymyr Zelenskyy has been really lionized, particularly in the U.S. and Western European media. And he’s become a kind of caricature, with these grand, sweeping historical comparisons. And often the quotes from him are intended to give the appearance of this defiant leader who is going to fight to the end. But when you read between the lines, and you read what Ukrainian negotiators are saying, when you read what Zelenskyy says when pressed on conditions for peace, he seems to be extremely aware of the factors that you’re citing, that this has to end in a negotiation.

And I want to ask you about the role of the U.S. and European media in perpetuating this mythology around Zelenskyy, and the way in which it seems to kind of undermine the seriousness of the negotiators of Ukraine or of Zelenskyy when he is talking in a nuanced manner. It seems that there’s this intent to kind of create a caricature rather than actually listening to the conditions that Ukraine is stating it can live with.

NC: Yes, you’re absolutely right. If you look at the media coverage, Zelenskyy’s very clear, explicit, serious statements about what could be a political settlement — crucially, neutralization of Ukraine — those have been literally suppressed for a long period, then sidelined in favor of heroic, Winston Churchill impersonations by Congressman, others casting Zelenskyy in that mold.

So, yes, of course. He’s made it pretty clear that he cares about whether Ukraine survives, whether Ukrainians survive, and has therefore put forth a series of reasonable proposals that could well be the basis for negotiation.

We should bear in mind that the nature of a political settlement, the general nature of it, has been pretty clear on all sides for quite some time. In fact, if the U.S. had been willing to consider them, there might not have been an invasion at all.

Before the invasion, the U.S. basically had two choices: One was to pursue its official stance, which I just reviewed, which makes the negotiations impossible and may have led to war; the other possibility was to pursue the options that were available. To an extent, they’re still somewhat available, attenuated by the war, but the basic terms are pretty clear.

Sergey Lavrov, Russian Foreign Minister announced at the beginning of the invasion that Russia had two main goals — two main goals. Neutralization of Ukraine and demilitarization. Demilitarization doesn’t mean getting rid of all your arms. It means getting rid of heavy weapons connected to the interaction with NATO aimed at Russia. What his terms meant basically was to turn Ukraine into something like Mexico. So Mexico is a sovereign state that can choose its own way in the world, no limitations, but it can’t join a Chinese-run military alliances in placing advanced weapons, Chinese weapons, on the U.S. border, carrying out joint military operations with the People’s Liberation Army, getting training and advanced weapons from Chinese instructors and so on. In fact, that’s so inconceivable that nobody even dares to talk about it. I mean, if any hint of anything like that happened, we know what the next step would be — no need to talk about it. So it’s just inconceivable.

And basically, Lavrov’s proposals could plausibly be interpreted as saying: Let’s turn Ukraine into Mexico. Well, that was an option that could have been pursued. Instead, the U.S. preferred to do what I just described as inconceivable for Mexico.

Now, that’s not the whole story. There are other issues. One issue is Crimea. The fact of the matter is Crimea is off the table. We may not like it. Crimeans apparently do like it. But the U.S. says: We’re never going to concede it. Well, that is the basis for permanent conflict. Zelenskyy has sensibly said: Let’s put that off for further discussion. That makes sense.

Another issue is the Donbas region. That’s been a region of extreme violence for eight years on both sides: Ukrainian shelling, Russian shelling, land mines all over the place, lots of violence. There are OSCE observers, European observers on the ground who give regular reports. You can read them, they’re public. They don’t try to assess the source of the violence — that’s not their mission — but they talk about its radical increase. According to them, if my memory is correct, about 15,000 people or something in that neighborhood may have been killed in the conflict over the last eight years since the Maidan Uprising.

Well, something has to be done about Donbas, the proper reaction, which maybe the Russians would accept, would be a referendum, an internationally supervised referendum to see what the people of the region want. One possibility, which was available before the invasion, was implementation of the Minsk II agreements, which provided for some form of autonomy in the region within a broader Ukrainian Federation, something like maybe Switzerland or Belgium or other places where there are federal structures — conflict, but confined within federal structures. That would have been a possibility. Whether it could have worked, there’s only one way to find out: to try. The U.S. refused to try; instead, insisted on a super-militant position, official position, which, as far as I know, the press has yet to report. You can tell me if I’m wrong, but I have never seen one reference anywhere in the mainstream press. Occasionally, we at the margins; any reference to the official U.S. position of September 1, 2021, the reiteration or expansion of it in November in the charter.

Actually I saw one reference to it in the American Conservative, conservative journal, which did refer to it. And, of course, on the left people have talked about it. But the U.S. insisted on that position, which the alternative would have been to pursue the opposite, the option of saying: OK, your main goals are neutralization and demilitarization, meaning Mexico-style arrangement, let’s pursue that. With regard to Crimea, let’s accept Zelenskyy’s sensible position that let’s delay it, we can’t deal with it now. With regard to the Donbas region, work towards some kind of framework with autonomy, based on the opinions of the people who live there, which can be determined by an internationally supervised referendum. Would the Russians agree? We don’t know. Would the United States agree? We don’t know. All we know is they’re rejecting it, officially. Could they be pressed to accept it? I don’t know. We can try. That’s the one thing we can hope to do.

I mean, there is a sort of a guiding principle that we should be keeping in mind, no matter what the issue, the most important question is: What can we do about it? Not: What can somebody else do about it? That’s worth talking about. But from the most elementary point of view, the major question is, what can we do about it? And we can, in principle, at least do a lot about U.S. policy, less about other things. So I think that’s where the focus of our attention and energy should be.

JS: I want to ask you about some of the statements that Biden administration officials have made in recent days. On the Sunday talk shows this past weekend, you had the national security adviser and the Secretary of State both laying out what was almost an overt war plan for seeking to fundamentally weaken the Russian state and talking about the war in Ukraine as helping to achieve a goal of a severely weakened Russia.

To what extent are U.S. actions that we’re witnessing now in Ukraine, ultimately aimed at bringing down the government, in Moscow, of Vladimir Putin? Yes, there was the kerfuffle over Biden talking about the this-guy’s-got-to-go quote. But the actions are playing out in full public view. And I think a lot of people put too much weight on a particular clip of Joe Biden, though he may have intentionally said it that way. It’s hard to tell right now with him whether he means to say something or not. But setting that aside, it does seem that a major aspect of the U.S. position right now is that this is a grand opportunity to — they smell the blood of Putin in the water, I guess, is what I’m saying now.

NC: Yes, I think the actions indicate that. But remember, there’s something along with action — namely inaction. What is the United States not doing? Well, what it’s not doing is rescinding the policies that I described, maybe the American press doesn’t let Americans know about them, but you can be sure that Russian intelligence reads what is on the official White House website, obviously. So maybe Americans can be kept in the dark, but the Russians read and know about it. And they know that one form of inaction is not to change that.

The other form of inaction is not to move to participate in negotiations. Now, there are two countries that could, because of their power, facilitate a diplomatic settlement — I don’t say bring about, but facilitate, make it more likely. One of them is China; the other is the United States. China is being rightly criticized for a refusal to take this step; criticism of the United States is not allowed, so the United States is not being criticized for its failure to take this step and, furthermore, its actions, which makes this step more remote, like the statements you quote on the Sunday talk shows.

Just imagine how they reach Putin and his circle, what they’re saying, what they interpret as meaning is: Nothing you can do. Go ahead and destroy Ukraine as much as you like. There’s nothing you can do, because you’re going to be out. We’re going to ensure that you have no future. So therefore, you might as well go for broke.

That’s what the heroic pronouncements on the Sunday talk show mean. It may feel like, again, Winston Churchill impersonations, very exciting. But what they translate into is: Destroy Ukraine. That’s the translation. Inaction, in refusal to withdraw the policy positions that the Russians certainly are fully aware of, even if Americans are kept in the dark, one is to withdraw those. Second is: Do what we blame China for not doing. Join in efforts to facilitate a diplomatic settlement and stop telling the Russians: There’s no way out; you might as well go for broke; your backs are against the wall.

Those are things that could be done.

JS: Now, I want to ask you about media coverage. And first, I just want to say that we have already seen a horrifying number of journalists killed in Ukraine. In fact, a friend of mine, the filmmaker Brent Renaud, was one of the first journalists killed in Ukraine. And it’s horrifying to witness media workers, some of whom appear to have been directly targeted for killing. So I guess I just want to say at the onset that I think we’re seeing some incredibly brave and vital journalism coming out of Ukraine, and much of it is being done by Ukrainian reporters. And that statement just needs to stand on its own.

But back in the studios in Washington, and Berlin, and London, there’s a different form of media activism happening. And it really seems as though many journalists see their role now working for powerful, particularly broadcast media outlets, as supporting the position of the United States and NATO and being actual propagandists for a particular outcome and course of action. And this is happening at the same time that the Biden administration is now admitting that it has been manipulating the media by putting out unverified intelligence and pushing claims about plans to use chemical weapons and other actions.

And I just want to read to you, Noam, from an NBC News report recently, it said: “It was an attention-grabbing assertion that made headlines around the world. U.S. officials said they had indications suggesting Russia might be preparing to use chemical agents in Ukraine. President Joe Biden later said it publicly. But three U.S. officials told NBC News this week there is no evidence Russia has brought any chemical weapons near Ukraine. They said the U.S. released the information to deter Russia from using the banned munitions […] Multiple U.S. officials acknowledged that the U.S. has used information as a weapon even when confidence in the accuracy of the information wasn’t high. Sometimes it has used low-confidence intelligence for deterrent effect, as with chemical agents, and at other times, as an official put it, the U.S. is just ‘trying to get inside Putin’s head.’”

Now this kind of activity from the U.S. government is not new. What I think is extraordinary or interesting is that they’re now not only owning it publicly, but they are almost celebrating that they’re able to use their own news media and powerful journalists to spread it as part of their war effort.

NC: As you say, it’s by no means new. You can trace it far back in a concentrated, organized form back to World War I, when the British established a Ministry of Information. We know what that means. The goal of the Ministry of Information was to put up horror stories about German war crimes which would induce Americans to get into the war, Woodrow Wilson — and it worked. If you read U.S. liberal intellectuals, they were taken. They accepted it. They said: Yes, we have to stop these horrible crimes that the British Ministry of Information is concocting in order to mislead us.

President Wilson set up his own ministry of public information, meaning lies to the public, to try to encourage Americans to hate everything German. So the Boston Symphony Orchestra wouldn’t play Beethoven, for example.

Then it goes on. Reagan had what’s called an Office of Public Diplomacy, meaning an office to lie to the public and the media about what we’re doing. But it’s not a hard task for the government.

And the reason was actually stated, rather clearly, by the public relations officer of the United Fruit Company, back in 1954, when the U.S. was moving to overthrow the democratic government of Guatemala and install a vicious, brutal dictatorship, which has killed hundreds of thousands of people with U.S. support ever since. He was asked by the media: What about the United Fruit Company efforts to try to convince journalists to support this? He said: Yes, we did it. But you have to remember how eager they were for the experience.

OK? Wasn’t hard. They wanted it. We fed them these lies. They were delighted because they wanted to support the state and its violence and terror.

Now, that’s not the journalists on the ground. There is a split, as you describe. It’s true of every war. So in Nicaragua, in the Central American wars of the 1980s, there were great reporters on the ground. The Vietnam War, same thing, doing serious, courageous work — many suffering for it. You get up to the newsrooms; it looks totally different. That’s a fact about the media.

And we don’t have to look far back. You can take a look at The New York Times. It’s the best newspaper in the world, which is not a high bar. Its main thinker, a big thinker, who writes serious articles, had an article, an op-ed a day or two ago, saying: How can we deal with war criminals? What can we do? We’re stuck. There’s this war criminal running Russia. How can we possibly deal with him?

The interesting thing about that article is not so much that it appeared. You expect that kind of stuff. It’s that it didn’t elicit ridicule. In fact, there was no comment on it. We don’t know how to deal with war criminals? Sure, we do. In fact, we had a clear exhibition of it just a couple of days ago. One of the leading war criminals in the United States is the man who ordered the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq; can’t go far beyond that as being a war criminal. And, in fact, on the 20th anniversary of the invasion of Afghanistan, there was one interview in the press. To its credit, The Washington Post did interview him in the Style section. The interview is worth reading: It’s about this lovable, goofy grandpa playing with his grandchildren; happy family, showing off the portraits he painted of great people he had met.

So we know how to deal with war criminals. What’s the problem? We deal with them very easily. Nevertheless, this column could appear in the world’s greatest newspaper, which is interesting enough, and not elicit a word of comment, which is much more interesting.

Well, that tells you what you’re talking about, as Tom McCann said, the United Fruit Company PR guy: They’re eager for the experience.

It doesn’t take much propaganda. So the government can work hard with its cognitive control systems. But it’s pushing an open door at the editorial level. And this has been true as far back as you want to go, and it still is.

JS: Charlie Savage, who is not an op-ed writer, but is an excellent national security reporter for The New York Times, also had a piece that dealt with some of this this week in The New York Times. And it was an analytical piece, looking at the challenge that the U.S. has made for itself because of its grand hypocrisy on issues of international criminal court.

And I just want to summarize a little bit for people that maybe don’t follow this the way that you do or I do. But the short of it is that the United States has consistently been adamantly and militantly opposed to any international judicial body that would have jurisdiction over its own actions. And in fact, in 2002, George W. Bush signed into law a bipartisan piece of legislation that came to be known as the Hague Invasion Act. And people can go online and read the bill themselves, and it’s still the law of the land in the United States, but one of the clauses of that law states that the U.S. military can be authorized to literally conduct a military operation in the Netherlands to liberate any U.S. personnel who are brought there on war crimes charges or under war crimes investigation. That’s why it’s called, by many activists and civil libertarians, the Hague Invasion Act.

At the same time, Joe Biden himself has said Vladimir Putin is a war criminal, and has called for a war crimes trial while the United States itself has only supported these ad hoc tribunals for countries like Yugoslavia, or Rwanda, and, like Russia, the United States refuses to ratify the treaty that established the International Criminal Court.

I’m sure, Noam, that you and I both agree that there are massive war crimes being conducted right now in Ukraine — certainly Russia is the dominant military power and I wouldn’t be surprised for one second if a huge percentage of the war crimes being committed are being done by Russia. That doesn’t mean that there aren’t war crimes being committed by Ukraine. We already have video evidence of this, of both Ukraine and Russia. But I want to be clear here; I believe that Russia is committing systemic war crimes in Ukraine. But when you have the United States undermining the International Criminal Court, refusing to ratify the treaty, how can Joe Biden call for a war crimes trial, when Dick Cheney and George Bush are walking around as free men, not to mention Henry Kissinger? And when the U.S. itself won’t accept that that court should have jurisdiction equally over all powers in the world?

NC: Well, two questions, points of fact: You’re quite right, that the overwhelming mass of the war crimes, the ones that we should be considering, are carried out by the Russians. That’s not in dispute. And they are major war crimes. It’s also true that the United States totally blocked the ICC. But notice there’s nothing new about that. There’s even a stronger case, which has been deep-sixed. The United States is the only country to have rejected a judgment of the International Criminal Court — of the World Court. They used to have two companions, Hoxha of Albania and Qaddafi in Libya. But they are gone. So now the U.S. stands in splendid isolation in having rejected the judgment of the World Court, that was in 1986, dealt with one of Washington’s minor crimes, the war against Nicaragua. The court condemned the United States for — the words were — “unlawful use of force,” meaning international terrorism, ordered the U.S. to desist and pay substantial reparations.

Well, there was a reaction by the Reagan administration and Congress: Escalate the crimes. That was the reaction. There was a reaction in the press: The New York Times editorial saying the court decision is irrelevant, because the court is a hostile forum. Why is it a hostile forum? Because it dares to accuse the United States of crimes. So that takes care of that. So the reaction is to escalate the crimes.

Nicaragua actually sponsored first a Security Council resolution, which didn’t mention the United States, just called on all states to observe international law; the U.S. vetoed it. It was on record as saying to the Security Council, states should not observe international law. It then went to the General Assembly who overwhelmingly approved a similar resolution. U.S. opposed, Israel opposed, two states that should not observe international law. Well, all of that, that’s not part of history as far as the United States is concerned. That’s the kind of history, according to Republicans, you shouldn’t teach because it’s divisive, makes people feel bad. You shouldn’t teach it. But you don’t have to tell anyone because it’s not taught. And it’s not remembered — virtually no one remembers it.

And it goes beyond that. The United States, in fact, when the major treaties, like the Organization of American States treaty, were signed back in the 40s, the United States added reservations, saying basically not applicable to the United States. In fact, the United States very rarely signs any conventions — very rarely. I mean ratifies — sometimes it signs. And when it does ratify them, they are with reservations, excluding the United States.

That even includes the Genocide Convention. There is a Genocide Convention. The United States finally ratified it after, I think, about 40 years, but with a reservation saying inapplicable to the United States. We are entitled to commit genocide. That came to the international tribunals: Yugoslavia tribunal, or maybe it was the World Court. I don’t remember. Yugoslavia charged NATO with crimes in its attack on Serbia. The NATO powers agreed to enter into the details of the court operations. The U.S. refused. And it did on grounds that Yugoslavia had mentioned genocide. And the United States is self-immune, immunized from the charge of genocide. And the court accepted that correctly. Countries are subject to jurisdiction only if they accept it. Well, that’s us.

We can go on. We’re a rogue state, the leading rogue state by a huge dimension — nobody’s even close. And yet we can call for war crimes trials of others, without batting an eyelash. We can even have columns by the major columnist, most respected columnist, saying: How can we deal with a war criminal?

It’s interesting to look at the reaction to all of this in the more civilized part of the world, the global self. They look at it; they condemn the invasion, say it’s a horrible crime. But the basic response is: What’s new? What’s the fuss about? We’ve been subjected to this from you from as far back as it goes, Biden calls Putin a war criminal; yeah, takes one to know one. It’s the basic reaction.

You can see it simply by looking at the sanctions map. The United States doesn’t understand why most of the world doesn’t join in sanctions. Which countries join in sanctions? Take a look. The map is revealing. The English-speaking countries, Europe, and those who apartheid South Africa called honorary whites: Japan, with a couple of its former colonies. That’s it. The rest of the world says: Yeah, terrible, but what’s new? What’s the fuss about? Why should we get involved in your hypocrisy?

The U.S. can’t understand that. How can they fail to condemn the crimes the way we do? Well, they do condemn the crimes the way we do, but they go a step beyond which we don’t — namely, what I just described? Well, that means there’s a lot of work to do in the United States simply to raise the level of civilization to where we can see the world, the way the traditional victims see it. If we can rise to that level, we can act in a much more constructive way with regard to Ukraine as well.

JS: What do you see — or how would you analyze right now, the posture of the United States toward India and China, in particular? I mean, two massive countries representing a large portion of the world’s population, relative to the size of the United States for certain, but the economic pressure that the United States is putting on both India and China right now, what are the consequences of the U.S. posture toward both India and China right now?

NC: Well, it’s different. For one thing the United States is quite supportive of the Indian government. India has a neo-fascist government. The Modi government is working hard to destroy Indian democracy, turn India into a racist, Hindu kleptocracy, attack Muslims, conquer Kashmir — not a word about that. The United States supports all that. It’s very supportive. It’s a close ally, a close ally of Israel — our kind of guy, in other words, so no problem.

And the problem with India is it doesn’t go far enough. It doesn’t go as far as we want it to, to join in the assault against Russia. It is playing a neutral game like all of the Global South saying: Yeah, it’s a crime, but we’re not going to get involved in your game.

And the other thing is, India is participating, but not as actively as the U.S. would like in its policy of what the Biden administration calls “encircling China.” One of our major policy, Russia’s kind of a sideline, but the major policy is to encircle China — containment is out of fashion, so encircle China — with sentinel states, that’s the term that’s used, armed to the teeth with massive offensive capacity to protect ourselves from what’s called the threat of China. That’s a ring of states from South Korea, Japan, Australia, India — except India is not joining actively enough — which we will provide, the Biden administration has just recently announced providing advanced precision missiles aimed at China.

In the case of Australia, the United States, along with Britain, its puppy dog, is providing Australia with advanced nuclear submarines, advertised as able to get into Chinese ports without being detected and to destroy the Chinese fleet in two or three days. China has an ancient prehistoric fleet there — they don’t even have nuclear submarines — old fashioned diesel submarines.

Meanwhile, the United States is enhancing its own capacity to defend ourselves. So far, we have Trident nuclear submarines, which are able to, each one, one submarine, can destroy almost 200 cities anywhere in the world with a nuclear strike. But that’s not enough. We’re now moving to more advanced, I think it’s called Virginia-class submarines, which will be far more destructive. And that’s our policy towards China.

We also have an economic policy. The United States just passed a bipartisan, two-party supported act to improve the U.S. technology, science infrastructure, not because it would be good for the United States — we couldn’t consider that — but because it would compete with China. It’s the compete-with-China bill. So if we want to have better science and technology, it is because we have to beat down China, make sure China doesn’t get ahead of us. Let’s not work with China, to deal with truly existential problems like global warming, or less serious but severe problems, like pandemics and nuclear weapons. Let’s compete with them and make sure we can beat them down — that’s what’s important — and get ahead of them.

It’s a pathology. You can’t imagine anything more lunatic. Incidentally: What is the China threat? It’s not that China’s got a very brutal, harsh government. But the U.S. never cares about things like that. Deals with them easily. The China threat, there’s an interesting article about it by an Australian statesman, well-known international statesman, former prime minister, Paul Keating, who reviews the various elements of the China threat, and concludes, finally, that the China threat is that China exists. And he’s correct. China exists and does not follow U.S. orders. That’s no good. You have to follow U.S. orders. If you don’t, you’re in trouble.

Well, most countries do. Europe does. Europe despises U.S. sanctions against Cuba, Iran, strongly opposes them, but it observes them because you don’t step on the toes of the godfather. So they observe U.S. sanctions. China doesn’t. China’s engaged in what the State Department once called “successful defiance” of U.S. policies. That was 1960s when the State Department was explaining why we have to torture Cuba, carry out a terrorist war against it, almost leading to nuclear war, impose highly destructive sanctions — we’re still at it after 60 years, posed by the entire world. Look at the votes in the General Assembly 184-2, U.S. and Israel. We have to do it as the liberal state department explained in the 1960s because of Cuba’s successful defiance of U.S. policies going back to 1823.

The Monroe Doctrine, which stated the U.S. determination to dominate the hemisphere — [we] weren’t strong enough to do it at the time, but that’s the policy. And Cuba is defying it successfully. That’s no good.

China’s not Cuba, it’s much bigger. It’s successfully defying U.S. policies. So no matter how brutal it is, who cares? We support other brutal states all the time, but not successful defiance of U.S. policies. So therefore, we have to encircle China, with sentinel states, with advanced weapons aimed at China, which we have to maintain and upgrade, and ensure that we overwhelm anything in China’s vicinity. That’s part of our official policy. It was formulated by the Trump administration, Jim Mattis, in 2018, taken over by Biden. We have to be able to fight and win two wars with China and Russia.

I mean, that’s beyond insanity. The war with either China or Russia means: Nice knowing you, goodbye civilization, we’re done. But we have to be able to win and fight two of them. And now with Biden, we have to expand it to encircling China with sentinel states to which we provide more advanced weapons, while we upgrade our huge destructive capacity. Like we don’t want those weak nuclear submarines which can destroy 200 cities. That’s sissy stuff. Let’s go beyond.

And then Putin gave the United States a tremendous gift. The war in Ukraine was criminal, but also from his point of view, utterly stupid. He gave the United States the fondest wish; it could have handed Europe to the United States on a golden platter.

I mean, throughout the whole Cold War, one of the major issues in international affairs was whether Europe would become an independent force in international affairs, what was called a third force, maybe along the lines that Charles de Gaulle outlined, or that Gorbachev outlined when the Soviet Union collapsed; common European home, no military alliances, cooperation between Europe and Russia, which had become integrated into peaceful commercial blood. That’s one option.

The other option is what’s called the Atlanticist program, implemented by NATO. The United States calls the shots and you obey, that’s the Atlanticist program. Of course, the U.S. has always supported that one, and has always won. Now Putin solved it for the United States. He said: OK. You get Europe as a subordinate. Europe goes ahead and arms itself to the teeth to protect itself from an army, which Europe says gleefully, is incapable of conquering cities 20 miles from its border. So therefore, we have to arm ourselves to the teeth to defend ourselves from the onslaught of this extraordinarily powerful force against NATO. I mean, if anybody’s observing this from outer space, they’d be cracking up in laughter. But not in the offices of Lockheed Martin. They think it’s terrific. Even better in the offices of Exxon Mobil.

That’s the interesting part. There were some hopes, not major hopes, but some hopes of dealing with a climate crisis that is gonna destroy organized human life on Earth. Not tomorrow, but in the process of doing it. Current, most plausible projections are three degrees Centigrade increase over pre-industrial levels by 20 by the end of the century. That’s catastrophic. I mean, doesn’t mean everybody dies, but it’s a total catastrophe. Well, there were moves to stop that. Now they’ve been reversed.

You look at the stuff that’s coming out of the energy corporations, they’re euphoric. First, we’ve got all these annoying environmentalists out of our hair. They don’t bother us anymore. In fact, now we’re being loved for saving civilization. And that’s not enough. They say: We want to be “hugged” — their word — we want to be hugged by saving civilization, by rapidly expanding the production of fossil fuels, which will destroy everything, but put more cash in our pockets during the period that remains. That’s what somebody from outer space would be looking at. That’s us, OK?

JS: I know, Noam, we have to wrap up. But I do want to note that just in recent days we’ve heard now that the White House is proposing a record-shattering military budget, in excess of $813 billion. And you know, this would be a much longer conversation if we kept it going. But it’s really a number of very significant things that have happened over the course of this war, from the perspective of the U.S. and NATO, among them Germany lifting its cap on the amount of its GDP that it will spend on defense, the pipeline of weapons. And many European countries have been very hesitant to get super-involved with transferring weapons systems and now there’s discussion of even more permanent NATO bases.

And I think part of what you’re getting at, which I think is important for people to understand, is that Vladimir Putin, for whatever reasons he made the decision to do this in Ukraine, ultimately has created conditions that the U.S. has long wished were there for the United States to assert total dominance over European decision-making on issues of militarism. It also is an enormous boondoggle for the war industry. And I think that it’s hard to — go ahead.

NC: And the fossil fuel industry.

JS: And the fossil fuel industry. And I think that as we watch the horrors of human destruction and mass murder happening in Ukraine, we also must find a way to think of the long-term consequences of the actions of our own government. And unfortunately, when you raise these issues, when I raised them, when others do right now, in the U.S. media contexts, there is this Neo McCarthyite response, where to question the dominant narrative, or to question the motives of those in power, is now treated as an act of treason, or it’s traitorous or you are a Putin stooge or are being paid in rubles. This is a very dangerous trend that we’re witnessing where to question the state now is being very publicly and consistently equated with being a traitor.

NC: That’s an old story.

JS: It’s an old story, but also with social media, and the fact that so many people now could have their comments spread around, and the cohesion of messaging that we’re seeing — it is an old story, Noam, of course, and you’ve written multiple books about this very phenomenon. What I’m getting at is that it now is just permeating every aspect of our culture, where to question those in power, which is the job of journalists, which is the job of thinking, responsible people in a democratic society, those things are being attacked as acts of treason, basically.

NC: As always has been the case. We have a dramatic example of it right in front of us: Julian Assange. A perfect example of a journalist who did the job of providing the public with information that the government wants suppressed. Information, some of it about U.S. crimes but other things. So he’s been subjected to years of torture — torture — that’s the U.N. Repertory torture decision, now being held in a high-security prison, subjected to the possibility of extradition to the United States where he’ll be severely punished for daring to do what a journalist is supposed to do.

Now take a look at the way the media are reacting to this. First of all, they used everything WikiLeaks exposed, happily used it, made money out of it, improved their reputations. Are they supporting Assange, and this attack on the person who performed the honorable duty of a journalist and is now being tortured? Not that I’ve seen. They’re not supporting it. We’ll use what he did, but then we’ll join the jackals who are snapping at his feet. OK? That’s now. It goes far back.

You go back to 1968, the peak of the war in Vietnam, when real mass popular popular opinion was developing. When McGeorge Bundy, national security adviser for Kennedy and Johnson wrote a very interesting article in Foreign Affairs, a main establishment journal, in which he said: Well, there are legitimate criticisms of some of what we’ve done in Vietnam, like we made tactical errors, we should have done things a little differently. And then he said, there are also the wild men in the wings, who question our policies beyond tactical decisions — terrible people. We’re a democratic country, so we don’t kill them. But you got to get rid of these wild men in the wings — [that’s] 1968.

You go to 1981: U.N. ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick devises the notion of moral equivalence. He said: If you dare to criticize the United States, you’re guilty of moral equivalence. You’re saying we’re just like Stalin and Hitler. So you can’t talk about the United States.

There’s another term that’s used now. It’s: whataboutism. If you talk about what the U.S. is doing right now, it’s whataboutism, you can’t do that. You’ve got to adhere firmly to the party line, strictly to the party line. We don’t have the kind of force that Hitler and Stalin had. But we can use obedience, conformity — a lot of things we’ve been talking about. And you get a sort of similar result — not new.

And yes, you’re right, it has to be combatted. We have to deal with what’s happening. And that includes what we are now doing to Ukraine, as we’ve discussed, both by inaction and action, we’re fighting to the last Ukrainian to quote Ambassador Freeman again. And it should be legitimate to say that if you care anything about Ukrainians. If you don’t care anything about them, fine, just silence.

JS: On that note, Noam Chomsky, I want to thank you very much for taking the time to be with us and for all of your work. I really appreciate you taking the time this evening.

NC: Good to talk to you.

A man walks near a residential building destroyed in the southern port city of Mariupol, Ukraine, on April 17. (photo: Alexander Ermochenko/Reuters)

A man walks near a residential building destroyed in the southern port city of Mariupol, Ukraine, on April 17. (photo: Alexander Ermochenko/Reuters)

Analysts expect Russia to capture the devastated city soon while it refocuses its military might on Ukraine’s eastern region after failing to seize the capital, Kyiv.

The battle for control over eastern and southern cities is the latest stage in a war now in its eighth week, as Russia attempts to solidify its grip on an area that provides strategically important access points to the Black Sea and beyond. Ukrainian leaders, meanwhile, made pleas on Sunday news programs for additional U.S. support.

The officials said besieged cities including Mariupol remain under their control but described conditions as increasingly dire.

The “city still has not fallen,” Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal said Sunday on ABC’s “This Week.” “There is still our military forces, our soldiers. So they will fight till the end.”

Russia had given Ukrainian forces in Mariupol a deadline of 6 a.m. local time Sunday (11 p.m. Eastern time Saturday) to surrender. Russia said it broadcast its orders every 30 minutes throughout the night and vowed to guarantee the lives of those who laid down their arms in a five-hour period immediately after the deadline, according to state media.

Troops have laid siege to the port city for more than a month in a Russian attempt to take control of all along the coast of the Sea of Azov. Doing so would give Russia control of the land and sea between territories it holds in Ukraine’s east and the Crimean Peninsula, which it annexed in 2014.

An estimated 100,000 civilians, less than a quarter of the prewar population, remain in Mariupol cut off from food, water, heat and humanitarian aid, with some exceptions. Mariupol emerged as an early flash point in the war with horrifying scenes captivating the world’s attention, including the bombings of a maternity ward and a theater where hundreds sought refuge.

Moscow contends that remaining pro-Ukrainian forces in Mariupol have lost control of all but the Azovstal steel plant, one of the largest metallurgical factories in Europe. The Washington Post cannot verify that claim, and Ukrainian authorities say they still have troops elsewhere in the city.

Russian forces “likely captured” the port area of Mariupol on Saturday, further reducing Ukrainian defenses outside of the factory, according to an assessment by the Institute for the Study of War, a think tank. The report refers to footage of Russian forces in numerous “key locations,” including the port itself.

“Isolated groups of Ukrainian troops may remain active in Mariupol outside the Azovstal factory, but they will likely be cleared out by Russian forces in the coming days,” the institute’s latest assessment says.

The evaluation adds that Russian forces could try to force the remaining defenders in the factory to “capitulate through overwhelming firepower.” Ukrainian forces, it says, “appear intent on staging a final stand.”

Moscow claims the Ukrainian government forbade negotiations to surrender at the plant, citing intercepted radio communications. Russian officials threatened those who remain.

“In the case of further resistance, they will all be eliminated,” the Russian Defense Ministry posted on the Telegram messaging app.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky told Ukrainian media outlets that negotiations between the two sides could end if Russian forces killed all of the Ukrainians defending the city.

Analysts predict Mariupol will become the first major Ukrainian city to fall under Russian control, and Ukrainian officials have described the city as all but lost.

Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba told CBS’s “Face the Nation” that Mariupol “doesn’t exist anymore” and faces a situation that is “dire militarily and heartbreaking.”

Russian forces are issuing passes for movement around the areas they control in Mariupol. Starting in the coming days, they will be required by anyone leaving their homes, said Petro Andrushchenko, an adviser to Mariupol’s Ukrainian mayor.

Russia had not agreed on cease-fires to allow the evacuation of civilians, including in Mariupol, on Sunday, Ukrainian Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk said.

“We are working hard to get the humanitarian corridors back on track as soon as possible,” she added.

Control over all of Mariupol would mark a significant turning point for Russia, which has struggled to capture major cities after its early occupation of Kherson in the south. Russian President Vladimir Putin faces pressure at home to show successes for a war that has killed thousands of Russian troops, with the precise toll unclear, and has resulted in widespread economic hardship from sanctions.

Russia’s eastern pivot encroaches on friendlier territory where pro-Moscow separatists have fought for years. Analysts say the open terrain in the energy-rich industrial Donbas region is better for Russian troops who struggled in urban battles, where Ukrainian forces had the edge.

“They want to literally finish off and destroy Donbas. Destroy everything that once gave glory to this industrial region,” Zelensky said in a televised address Sunday. “Just as the Russian troops are destroying Mariupol, they want to wipe out other cities and communities in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.”

Ukrainian officials confirmed that the country’s financial team will meet with representatives of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the U.S. Treasury in Washington this week. World Bank officials are planning a $3 billion package to support Ukraine.

The prime minister said financial assistance is essential as the country runs a $5 billion-a-month deficit.

“We need more finances to support our people, our refugees, our internally displaced persons — to save our economy for future recovery,” Shmyhal said on “This Week.”

World Bank economists recently estimated that Ukraine’s economy could shrink 45 percent this year, depending on the length and severity of the conflict. An economic collapse of that magnitude would dwarf the 11.2 percent the Russian economy is expected to shrink over the same time because of unprecedented sanctions, and would exacerbate the humanitarian crisis in the region.

The European Union is allocating another 50 million euros ($54 million) in humanitarian aid as part of its 1 billion euro pledge, officials announced Sunday.

The money is aimed at helping people in “hard-to-reach areas who are cut off from access to healthcare, water and electricity, and those who have been forced to flee and leave everything behind,” Janez Lenarcic, commissioner for crisis management, said in the statement, adding that the European Union must prepare for an escalation in Russia’s attacks, principally in eastern Ukraine.

Reports of casualties from other eastern Ukrainian regions continued. In Kharkiv, five died and 13 were wounded in strikes Sunday, local officials said. They are among 18 killed and 106 wounded during Russian shelling of Kharkiv in the past four days, Zelensky said Sunday.

Earlier Sunday, Oleh Synyehubov, head of Kharkiv’s regional administration, said three people were killed and 31 injured in Russian shelling over the previous 24 hours. He appealed to those still in the Kharkiv region to avoid being out on the streets.

A World Central Kitchen restaurant partner in Kharkiv is relocating after a missile struck the building where a team of volunteers had been cooking free meals for residents, injuring four staff members, CEO Nate Mook said Sunday.

“This is the reality here — cooking is a heroic act of bravery,” he said on Twitter.

Another humanitarian organization’s leader described the challenges of getting food in various areas.

“I’ve seen places where there’s nothing in these warehouses but food, and that’s not even in Mariupol,” David Beasley, head of the U.N. World Food Program, said on “Face the Nation.” “There is no question food is being used as a weapon of war in many different ways here.”

The eastern Luhansk region’s governor said Sunday that Russian shelling hit a residential part of Zolote, killing two people and wounding four. Local Ukrainian officials also accused Russia of shelling a church in the city of Severodonetsk on Sunday.

Russian missile strikes continued over the weekend in the Kyiv area even as forces turned toward the east. An attack Saturday on the capital killed at least one person and injured several, the mayor said. Another strike hit the Kyiv suburb of Brovary.

Officials also said Sunday they pulled another body from the ruins of apartment buildings in the Kyiv suburb of Borodyanka shelled earlier in the month. The death toll from the attack that leveled much of the suburb is expected to rise as authorities search the rubble of two more destroyed buildings.

In an interview with CNN’s Jake Tapper that aired Sunday, Ukraine’s president said world leaders are failing to live up to the promise of “never again” after the Holocaust.

“We don’t believe the words,” Zelensky said. “After the escalation of Russia, we don’t believe our neighbors. We don’t believe all of this.”

Demonstrations against Russia’s war in Ukraine took place across Europe over the weekend, including in Amsterdam, Berlin and Barcelona and outside the British prime minister’s official residence in London.

Pope Francis, in his Easter address delivered to tens of thousands of worshipers in the Vatican’s St. Peter’s Square, called for “peace for war-torn Ukraine.”

“We have seen all too much blood, all too much violence,” he said. “Our hearts, too, have been filled with fear and anguish, as so many of our brothers and sisters have had to lock themselves away to be safe from bombing.”

Zelensky also invoked Easter in his Sunday address, describing the holiday as a celebration of the victory of life over death.

“I wish you to keep the light of soul even in this dark time of war against our state,” he said. “To keep it to see how good will soon surely defeat evil for the sake of our country, and how the truth will overcome any lies of the occupiers.”

The war in Ukraine is having knock-on effects in other parts of the world, including Somalia, where is is making a hunger problem worse. (photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP)

The war in Ukraine is having knock-on effects in other parts of the world, including Somalia, where is is making a hunger problem worse. (photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP)

It has been 41 days since the Russians launched their invasion of Ukraine, and agriculture executive Alex Lissitsa sighs deeply into the camera of his smartphone. He says that even he doesn’t really know what is left of his company. He is planning on heading out to the fields the next day to take a look, but he has no idea what he is going to find.

An energetic man with a high forehead, Lissitsa attended university in Berlin, the United States and Australia. For the last several years, he has been head of the agricultural company IMC, which is listed on the Warsaw stock exchange. His fields, located to the northeast of Kyiv, primarily produce corn and wheat.

Following the invasion, Lissitsa headed for the safety of central Ukraine, relocating to his company’s branch office in the city of Poltava in central Ukraine, which is currently home to hundreds of thousands of people who have fled Kharkiv. From there, he maintains contact with colleagues via Telegram and WhatsApp. Before the attack, as they were considering a number of possible scenarios, Lissitsa asked them to print out lists of telephone numbers on paper. "As a digital company," he says, "we thought we would more likely be facing a cyberattack."

But then, company employees wrote him that tanks were rolling through the villages. Workers who would usually be spreading fertilizer at this time of year were manning the checkpoints, while others had sought shelter in their cellars. At some point, Lissitsa had his site manager from Chernihiv on the phone – who told him that they were surrounded, and he was calling to bid farewell.

Two days later, photos showed up in his WhatsApp chat of rockets that had slammed into a storage facility containing 68,000 tons of corn. Meanwhile, hundreds of cattle fell ill and starved to death in a stall located in occupied territory. Then, a laboratory belonging to the country burned up, along with the office next door and a grain silo full of 30,000 tons of wheat.

Lissitsa swallows hard. "I hope that at least half of our fields can still be planted," he says.

There are a number of agronomists in Ukraine who are facing similar difficulties. Farms across the country have had to suspend operations. Fields have gone unplanted because they are covered with mines or destroyed military equipment or because staff has joined the fight. Tons of grain is sitting unused in storage facilities because of a lack of fuel or because roads are unusable, and ports are blocked. In a normal March, Lissitsa says, his country would likely have exported 5 million tons of wheat. This year, exports hardly even amounted to 200,000 tons. His own company didn’t export anything at all.

It is a collapse that doesn’t just have consequences for Ukraine. If the agricultural experts are right, it could trigger famine in a number of different corners of the world.

The grain produced by the region’s fertile soil is vital for the global food system. In combination with Russia, whose exports have also collapsed as a result of sanctions, Ukraine covers around 30 percent of the world’s wheat exports and roughly 15 percent of corn and barley exports. And the two countries are responsible for fully two-thirds of all global exports of sunflower oil. According to one study, the two countries produce around 12 percent of all calories consumed in the world.

Hunger Kills Slowly

Now that a significant share of this supply has vanished from the tightly woven global market, it has created a shockwave that can be felt in many areas of the world, including the Horn of Africa and the Middle East, where Lissitsa sends a large share of his harvests. Fewer deliveries are arriving in countries like Lebanon, Egypt and Yemen, which import almost all of their cereals from Ukraine and Russia. Prices could now explode, making food unaffordable for millions of people. Since the beginning of the war, the price of wheat has already risen by 40 percent.

The result, says David Beasley, director of the World Food Program, could exceed anything seen since World War II. WFP relies on Ukrainian cereals to feed roughly half of the 125 million people the organization provides aid to. In an address to the UN Security Council recently, he warned that his organization may soon have to ration food to the hungry to save the starving – and also that the situation could lead to unrest and mass displacement around the world.

"Depending on where I live, that could mean that I’ll have to pay more for food, will have to eat less, or will die because I was already on the brink," says agriculture expert David Laborde from the International Food Policy Research Institute in Washington.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations has calculated that the number of undernourished people could increase by 8 to 13 million if the prices remain high. And the poorest countries of Africa and Asia would very likely be the hardest hit.

Already, every second person living in sub-Saharan Africa has trouble securing sufficient food each day. According to a report by the International Committee of the Red Cross, it wouldn’t take much for the situation to turn into a full-blown catastrophe.

Thus far, though, the calls for help have largely gone unheeded. There are no shocking images making the rounds and no bodies lying in the streets – as there are in Ukraine. And there are no African heads of state regularly appealing to parliaments in the West as Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has been doing. Hunger is not a war crime, and it doesn’t arrive as suddenly as a shell bursting in one of Lissitsa’s grain silos.

Rather, it kills more slowly. But it has arrived.

It can be seen when a Lebanese school has to suspend meals for its students because no more wheat is arriving in the country. Or when Egypt announces fixed prices for non-subsidized bread in order to slow inflation.

Aid Organizations Cap Rations

"What is happening in Ukraine affects all of us," says Sacdio Osman Roble, a 20-year-old Somali woman who is currently living in a tent camp on the outskirts of Baidoa. The people who have ended up here have nothing: no running water, no electricity and no smartphones. Like most of those here, Roble lived with her three young children in the center of the country and had a field on which, after three years without rain, nothing grew. They were driven away by hunger.

"I fight every day to feed my children," Roble says. Like many in the camp, she spends her days begging in the streets. She stands in front of shops in which not just the bread is twice as expensive as it was just a couple of weeks ago. It’s hard, she says. "My children haven’t had any milk for days. The last thing they’ve had to eat was a couple spoonfuls of rice yesterday evening."

Somalia, which the FAO says receives more than 90 percent of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine, is one of the countries that has been hit hardest by the war. Three consecutive years of drought have transformed much of the country’s farmland into a dry crust. More than 2 million people in Somalia had, like Roble, no choice: When they ran out of supplies, they were forced to flee to camps run by the international aid industry.

Almost a third of the Somali population is already suffering from hunger, the FAO estimates. It is forecasted that 1.4 million children will face acute malnutrition this year.

They are abstract numbers that say little about the suffering faced by individuals, but they are enough to keep Rafaël Schneider up at night. Schneider works for the German aid agency Welthungerhilfe and he says that because the food storage facilities belonging to a number of organizations in Somalia are slowly emptying out, they have already been forced to cut rations by 30 percent in some places.

But that’s not all. In countries like Somalia, a large share of the aid is now delivered in the form of cash transfers to those in need. But with the prices skyrocketing, they are able to buy less – and larger monetary transfers aren’t currently an option. Many organizations are currently waiting to see if the amounts pledged by donor states will actually arrive or whether that money will be diverted to Ukraine.

The fight against hunger, as many on the front lines see it, is now a battle for coverage in the media. The fact that the suffering of some is weighed against the suffering of others is one of the perverse aspects of war.

Somalia is just one example of how various local flashpoints combine to form a wildfire. In Ethiopia, it’s the civil war. In South Sudan, it’s the floods. In Lebanon, the economic crisis began as early as 2019. The 2020 explosion at the port of Beirut exacerbated the crisis, one which the World Bank considers historic.

The country's currency has lost around 90 percent of its value in the past two years, and now the pound is plummeting further. Hospitals in many places run on diesel generators because there is no electricity. The Lebanese government, which has to feed not only its own citizens, but also around 1.5 million civil war refugees from Syria, is turning to the U.S. these days for fresh money to buy wheat on the world market.

Having To Choose Food over Medicine

If you spend an afternoon in Bab al-Tabbana, a neighborhood located in Tripoli’s "slum belt,” where people live close together in multistory apartment blocks, you can get a good idea of what it means when bread prices double within a few weeks.

On Tuesday, two neighbors, Hana Ahmad and Ahlam al-Mohamed, are sitting in one of the unheated apartments there. It’s Ramadan, the time of year when everyday life actually slows down, when fasting takes place during the day before families gather in the evening to ceremoniously break the fast.

But for this, Ahmad and Mohamed are now dependent on the help of a charity organization that goes through the neighborhood every evening distributing portions of rice, a little meat and some salad.

"It’s not much,” says Mohamed, whose husband earns about $2 a day as a day laborer in construction. "Sometimes I go to sleep on an empty stomach, so the kids at least get enough to eat.”

Ahmad, who is diabetic, dumps a bag of empty packages of medicine on the floor. She says she can’t afford the pills anymore. She has to set priorities now, and food comes before health.

"Our problem is that we have been saddled with one crisis after the next,” says IFPRI researcher Laborde. Each country has its own history, its own problems and its own crises. Then the coronavirus pandemic came along and crippled global supply chains. Public debt continued to rise, renewed demand caused energy prices to climb, and inflation arrived. FAO’s food price index had catapulted to unprecedented heights even before Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Are the Chinese Hoarding Wheat?

A major factor in this, agronomists believe, is the discreet wheat-buying spree of the Chinese. Faced with market uncertainty, China declared food security a national priority.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture says that 159 million tons of wheat are stored in reserve in Chinese silos. In order not to panic the markets and drive up prices unnecessarily for his own traders, the Chinese director general of the FAO reportedly even kept a UN paper under wraps that warned of an impending food crisis.

On the day the war began, China’s customs authorities lifted an import ban on Russian wheat that China had imposed because of sanitary concerns. Only days later, the first train with dozens of rail cars rolled across the border.

There are many who believe that the desired food self-sufficiency isn’t the only goal on leader Xi Jinping’s agenda. Many believe the wheat is also intended to expand China’s influence, including African countries suffering from famine but are rich in natural resources.

The invasion of Ukraine, it seems, is not only shaking up the balance of power in the world. It is also partially suspending the laws of capitalism.

In normal times, companies would respond to shortages and high prices by investing and ramping up production. The greater supply would eventually ensure that prices would slowly fall again. But this up-and-down market, which recurs in cycles, no longer seems to be working.

A Shortage of Fertilizer

Russia is not only one of the largest exporters of grain – it is also one of the most important producers of all artificial fertilizers used worldwide. This means that fertilizers are also currently in short supply as a result of the sanctions. For the remaining stocks still available on the world market, prices are being demanded that are causing many wheat producers to hesitate.

Smaller producers in particular are putting their production on hold because they lack the funds to invest. Others are reducing their acreage or fertilizing less, resulting in smaller or sometimes lower-quality crops that further tighten supply.

In Germany, the government has opened up environmentally protected areas for the cultivation of grain, and many are hoping that countries like Argentina will step into the breach and increase their wheat exports.

Argentina is the largest wheat producer in Latin America. In theory, says farmer Mariano Otamendi, he and fellow cultivators have "optimal conditions” to rapidly expand their capacity during the crisis. "Our operations are highly mechanized,” says Otamendi.

But the farmer, who runs a 200-year-old family business with his brother in the hinterland of Buenos Aires, nonetheless shrugs it off. "For us Argentines, there’s just no incentive,” he says. "And it’s not just because of high fertilizer prices.”

To cap inflation, the Argentine government has frozen prices. Whereas a ton of wheat currently trades for around $400 on the global market, it changes hand for less than half of that in Argentina. Otamendi says that 95 percent of the export quotas set by the government for this crop are already exhausted.

Meanwhile, says agricultural researcher Laborde, it is hardly likely that China will suddenly offer its reserves on the world market. He is calling on policymakers to crack down on hoarding to avoid artificially fueling the shortage.

As China triggers new chain reactions by halting fertilizer exports, grain wholesalers in Ukraine are looking for solutions to absorb the loss of their ports, through which 90 percent of exports normally pass.

They are now working to export the wheat released by the Agricultural Ministry by rail, but this is difficult, says one trader, because there are bottlenecks at the border stations. The rail gauges in Poland and Romania are also different from those in Ukraine. Right now, the evacuation of civilians is being given the priority. It’s only possible to get a few containers through each day.

The World Food Program in Somalia has just received the last shipload of shelled peas that left the port of Odessa in February, and it doesn’t know when the next ship will arrive. Many experts are calling for a radical rethink to avoid pitting one crisis against another.

Scientists like Benjamin Bodirsky, who researches global food systems at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research believe the food production is sufficient. For example, he says, it shouldn’t be the case that 60 percent of the grain produced in Germany is fed to animals.

Previously Unavailable Aid Suddenly Opens Up

Others, who have been fighting hunger for years, are scratching their heads with regard to Ukraine right now and how uncomplicated it can be to organize help. They are wondering how all these budgets are suddenly appearing that they were always told didn’t exist. And about the open borders. About what is suddenly possible when there is a political will to help.

Alex Lissitsa, the Ukrainian agricultural manager, is especially concerned about corn. It has no value in a silo. If it were left to sit there because of the closed ports, he says, he would lack the money to buy fertilizers and seed for the next season.

Lissitsa is still wearing his weatherproof jacket when he gets in touch from Kyiv. At 4 a.m. in the morning, he left for his inspection tour of the fields. He says he didn’t get very far because the roads were still closed, but he was at least able to have a meeting with staff. They decided at the meeting that they should start with the spring planting. They have to complete the process by May, because otherwise the soil will become too dry and too hard. "It’s going to be a battle against time,” Lissitsa says.

In this April 16, 2018, photo, a guard tower stands above the Lee Correctional Institution, a maximum security prison in Bishopville, SC. (photo: Sean Rayford/AP)

In this April 16, 2018, photo, a guard tower stands above the Lee Correctional Institution, a maximum security prison in Bishopville, SC. (photo: Sean Rayford/AP)

Matthew Ware, a former supervisory corrections officer at the Kay County Detention Center, violated "the civil rights of three pretrial detainees," the Justice Department said in a release.

According to the release, Ware "willfully" deprived them of their "right to be free from a corrections officer's deliberate indifference to a substantial risk of serious harm" and "use of excessive force," a jury found.

In 2017, Ware commanded lower-ranking officers to move two Black detainees to a cell row that housed "white supremacist" inmates, the release stated. These inmates "posed a danger" to the detainees, D'Angelo Wilson and Marcus Miller.

Later that day, Ware ordered the officers to unlock the doors to both the jail cells of the detainees and of the white supremacist inmates.

"When Ware's orders were followed, the white supremacist inmates attacked Wilson and Miller, resulting in physical injury to both, including a facial laceration to Wilson that required seven stitches to close," the release said.

In 2018, Ware directed a lower-ranking officer to restrain Christopher Davis, another pretrial detainee. Davis was placed in a "stretched-out position," in which his left wrist was "restrained to the far-left side of the bench" and his right "to the far-right side," the release said.

Davis remained in that position for 90 minutes and sustained physical injuries as a result. The restraining act is believed to have been in retaliation for Davis criticizing the way Ware ran the Center.

"This high-ranking corrections official had a duty to ensure that the civil rights of pretrial detainees in his custody were not violated," Kristen Clarke, assistant attorney general of the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division, said in a statement.

She continued: "The defendant abused his power and authority by ordering subordinate corrections officers to violate the constitutional rights of several pretrial detainees. The Civil Rights Division will continue to hold corrections officials accountable when they violate the civil rights of detainees and inmates."

Ware will be sentenced in July. He faces a maximum 10-year prison sentence, a fine of up to $250,000 for each violation, and three years of supervised release.

Lisa Pascoe with her 2-year-old daughter on Wednesday, March 23, 2022, at their home in Clarkson Valley, Mo. (photo: St. Louis Public Radio)

Lisa Pascoe with her 2-year-old daughter on Wednesday, March 23, 2022, at their home in Clarkson Valley, Mo. (photo: St. Louis Public Radio)

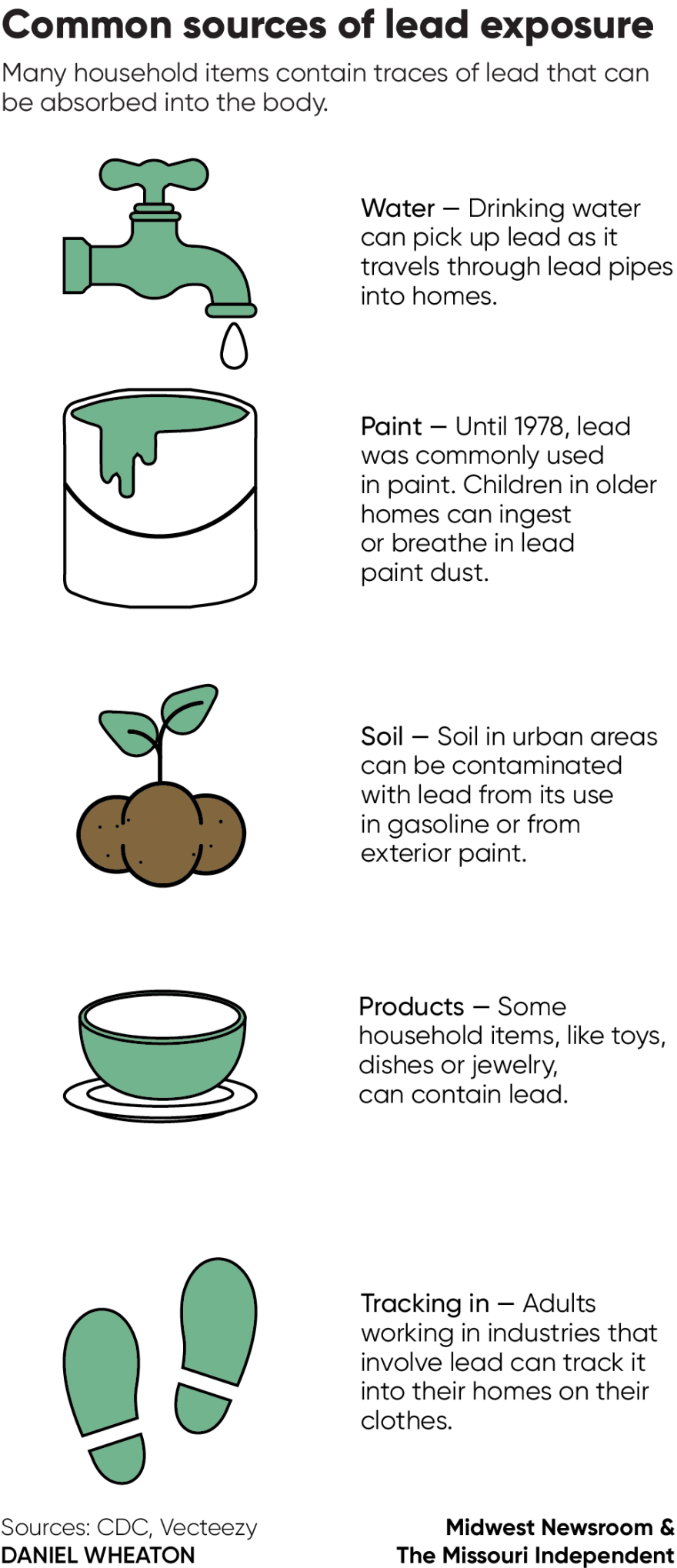

Researchers say even a small amount of the toxin can harm kids’ development. One 2021 study found Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska and Missouri had some of the highest rates of elevated blood lead levels in children.

But then the nurse called to say her son's blood lead level was dangerously high — five times the level federal health officials then deemed elevated.

Pascoe said she was "completely shocked."

"After you hang up on the phone, you kind of go through this process of 'Oh my gosh, my kid is lead poisoned. What does that mean? What do I do?'" she said.

That same week, St. Louis city health workers came out to test the home to identify the source of the lead.

The culprit? The paint on the home’s front window. Friction caused by opening and closing the window caused lead dust to collect in the mulch and soil outside of the house, right where her son played every day.

A decade later, the psychological scars remain. Pascoe and her toddler ended up leaving their St. Louis home to escape lead hazards. To this day, she’s extra cautious about making sure her son, now a preteen, and her two-year-old daughter aren’t exposed to lead so she doesn’t have to relive the nightmare.

Pascoe’s son was one of almost 4,700 Missouri children with dangerous levels of lead in their blood in the state’s 2012 report — decades after the U.S. started phasing lead out of gasoline and banned it in new residential paint and water pipes. Missouri’s lead poisoning reports run from July through June. Though cases have fallen precipitously since the mid-20th century, lead is a persistent poison that impacts thousands of families each year, particularly low-income communities and families of color.

Eradicating it has been a decades-long battle.

No safe level

Omaha, Nebraska, has been cleaning up contaminated soil from two smelters for more than 20 years. The Argentine neighborhood of what is now Kansas City, Kansas, grew up around a smelter that produced tens of thousands of tons of lead as well as silver and zinc. About 60% of homes in Iowa were built before 1960, when residential lead-based paint was still used. Missouri is the number one producer of lead in the United States.

The four states have some of the most lead water pipes per capita in the country. While representative data on the prevalence of lead poisoning is hard to come by because screening rates lag in many areas, one study published last year found that the four states struggled with some of the highest rates of lead poisoning.