Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

If further escalation is a possibility, defense contractors and cold warriors in Washington won’t define it—the Ukrainians will.

The economic sphere is where Ukraine’s allies, in Washington and Brussels and Tokyo and London and Berlin, have most readily confronted the Kremlin—freezing assets, applying sanctions, working to insure that few are willing to sell what Moscow wants to buy. But, however likely these measures are to choke the Russian economy in the medium term, it’s been hard to see any real effect on the war machine. “When people are saying the sanctions are working, in our view it’s really ridiculous,” Ustenko said. “Even today—the capital, they bombed all night. So people were hidden in the bomb shelters from, I would say, 10 P.M. until 6 A.M. Then they were allowed to go out on the ground, and then again the bombs started. So they are sending missiles all the time.”

The trouble, he went on, was that the sanctions had left an enormous loophole. Russia’s foreign-currency reserves had been frozen—a measure the Kremlin did not anticipate—and the U.S. has banned the importing of energy from Russia, but Europe, crucially, has not. Since the invasion began, hundreds of millions of dollars have flowed into Russia each day. Ustenko and his team have been tracking the tankers; among the largest European importers of Russian oil and gas are Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands. “Our logic is that whoever is financing Putin’s military machine is also financing the war crimes,” he said. “Twenty-four hours, seven days a week, we are searching for everybody who was in the Russian oil ports. We know exactly the volume of oil that was loaded, where it was lifted—we know the country, the flag, the port of destination, the name of the captain.”

What was under way seemed obvious to Ustenko: a cash-and-carry operation. With his country’s assets frozen, Vladimir Putin needed currency in order to pay for military equipment to keep the war going, both from domestic producers and overseas, where he had reportedly appealed to China for military assistance. Ustenko said, “Look, he’s searching desperately on the market to try to find weapons—he needs cash. If he doesn’t have cash on his hands, he will not be able to run his military.” Putin’s last recourse was energy. “The West will never stop buying energy from Russia—it was his working assumption from the very beginning, from the point when he started to build this kind of economy,” Ustenko said. “It’s not difficult to get to the conclusion that Putin is thinking that he is holding the global economy by the neck. And that nobody will be, not even willing, but able to switch off from him.”

Ustenko’s career has run in parallel with the post-Soviet market transition, which he has studied and advised. He did graduate work at Harvard and Brandeis; his 1995 thesis, from Kyiv National Economic University, was titled “Diversifying Production in the Context of a Developing Market Economy.” In the presentations that Ustenko has given to Western economic think tanks this month, he has looked like one of their own, with neat glasses and unkempt hair. On the phone, he had an understated manner. At one point, when the connection cut out, Ustenko said, “Look, the line is really very bad here due to current conditions.” Then he kept going.

His timelines have changed. Market liberalization takes place across decades; the current war is measured in hours. Ustenko spoke about the assistance that the West had given Ukraine—the access to new loans and grants, the choice that the Biden White House and the governments of Poland and Denmark had made to stop oil and gas imports. He sounded grateful for all of it. But, still, the loophole was open; energy was flowing to the West and cash to the East. I asked what his conversations were like with officials from European countries that haven’t yet sworn off Russian energy. “They are trying to move the horizon. They are trying to do it a bit later than is really necessary,” Ustenko said. “And for us it is completely unacceptable. Everybody in Europe, they do believe that they have to cut off. But the only question is: when?”

In the five weeks since Russia invaded Ukraine, the policy response from the West has grown increasingly expansive. A direct military confrontation with Russia, in the form of a NATO-imposed no-fly zone, was ruled out from the start. Everything else now seems to be on the table. From Washington, cash is flowing: $13.6 billion in aid for Ukraine, including several billion dollars to purchase military equipment. Some four thousand and six hundred Javelin anti-aircraft missiles, more than half the total purchased by the Pentagon in the past decade, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, have been sent to Ukraine in the past month. Famously neutral Switzerland and Sweden have strayed from their usual positions; Germany halted the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, a controversial eleven-billion-dollar project. The Central Bank of Russia, whose activities were restricted by an alliance of Western countries last month, is the largest and most significant economic entity ever sanctioned. A status quo that had long tolerated Putin and his oligarchs is showing some signs of shifting. For many weeks, it was taken as an article of faith that no U.S. official would say anything to hint that Washington meant to foment a regime change in Moscow. Then, on March 26th, President Biden travelled to Warsaw and, addressing a crowd of thousands, said, “For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power!”

Ukrainian military success has been one reason for these changes. “Before the war, the Biden Administration was trying to deter it by threatening sanctions,” Daniel Fried, who was Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama and is now at the Atlantic Council, told me. “They assumed the Russians would be militarily victorious. That assumption is now questionable. It is now an open question as to who wins. Let that sink in for a minute. Russia attacks Ukraine, it’s an open question as to who succeeds. That’s a kind of ‘Oh, shit, really?’ moment.”

Ukraine’s appeals to solidarity have also activated something in Western politicians—in Biden perhaps most of all. Fried had been the Polish desk officer at the State Department in 1989, during the Solidarity movement. He said that, in Biden’s Warsaw speech, he heard clear echoes of Ronald Reagan’s “evil empire” address in Berlin. To him, this underscored the differences between Biden and Obama. “All Biden’s points of reference are different,” Fried said. “He was an adult before Vietnam.” But, if this is a hawkish phase, in which escalation is again a possibility, then it isn’t defense contractors or cold warriors in Washington who have defined it. It is the Ukrainians. Every few days, Zelensky has appeared via video link to a standing ovation of Western legislators (in Congress, the U.K. Parliament, the Bundestag) to ask for more material help: more severe sanctions, more financial assistance, more military equipment, a no-fly zone. In these appearances, he is posing a version of the question Ustenko posed to me: Having defined this as a conflict between a democracy and a war criminal, how far are Western politicians prepared to go to help the democracy?

For some hawks in Washington, the Ukrainian success so far has meant that the United States may not need to go as far as they had initially imagined. “A no-fly zone is unpalatable at the moment, but it may not be necessary,” Alexander Vindman, the former National Security Council director for European Affairs who was fired after testifying at President Donald Trump’s first impeachment trial, told me. Vindman, who was born in Ukraine, had called for a new Marshall Plan and a lend-lease program in which significant weaponry would be provided to Kyiv at little to no cost. When I spoke with him this week, he emphasized that what was really needed was military equipment that we and other Western partners had at hand: long-range missiles that could target Russian air bases outside Ukraine, more shoulder-fired anti-tank and anti-aircraft weapons, and drones that can target tanks and armored personnel carriers. “We’re entering a more dangerous phase, potentially,” Vindman said. “Russia has less capability, but it’s going to be more focussed.”

But the moral case Vindman made for intervention sounded like it hadn’t changed much at all. “It’s not simply in the Ukrainian interests—it’s in our interests to win,” he said. “Right now, it looks like China is sitting this out, but that’s because Russia is losing. If it looks like Russia is going to win, then they’re going to go to their natural state of wanting to support Russia, and then it’s a major win for the authoritarian regimes crushing democracy. Frankly, I don’t think that’s a battle we can afford to lose.”

The Ukrainians’ success has eased some of the doves’ most vivid worries as well. “After some sleepless nights during the first weeks of the invasion, I’m glad to say I’m sleeping now,” Stephen Wertheim, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told me. Even so, he went on, the Western response did not seem to suggest a steady strategy but instead a pattern of drift—of vigorous indirect action, broad talk, and somewhat ill-defined aims that hinted at escalation without committing to it: “You have to think, why is the U.S. taking all these risks?” The Administration, he said, had been very clear that U.S.’s vital interests were not at stake in Ukraine. There was an obvious moral argument, he said, but it was entangled with a second. “Part of it has to do with seeing an opportunity to cripple Russia, and in so doing to unite the West under American leadership,” he said. The quick change in posture made it difficult to see which motive was the real one. Wertheim said, “I don’t think Vladimir Putin can tolerate losing power—which is why talk of regime change is so dangerous.”

The news from Ukraine this week has carried some flickers of hope: a counteroffensive that pushed Russian troops back from the outskirts of Kyiv, a stalled advance in the south, peace talks substantial enough that plans were reportedly being made for Putin and Zelensky to meet face to face. In our conversation, Ustenko, the Ukrainian economic adviser, had mentioned to me how many children had been killed. He told me how many women Russian soldiers had raped, according to a Ukrainian prosecutor, and how young and old the women were alleged to have been. But his argument wasn’t just humanitarian. Ustenko wanted something, which was for European countries to stop importing Russian energy, and he was insistent that this would have the effect of stopping all these horrors. “I think it’s going to be almost an immediate effect on his economy,” Ustenko said. To my ear, it sounded like Ustenko was trying to emphasize how much still hangs in the balance. Devastation was still possible. So was victory.

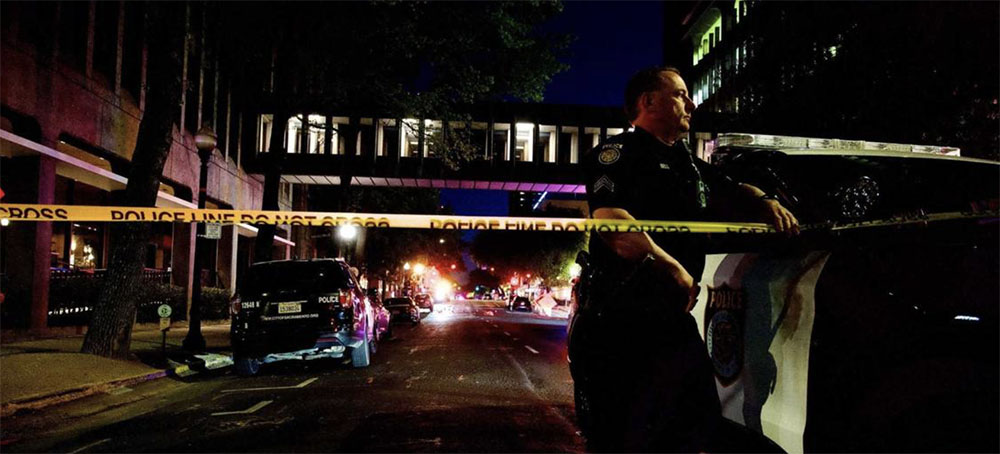

Sacramento Police Department Officer David Bell stands on the scene at 10th and L streets in downtown Sacramento on Sunday, April 3, 2022. Six people were killed and at least nine others have been injured after a shooting in downtown Sacramento. (photo: Hector Amezcua/SacBee)

Sacramento Police Department Officer David Bell stands on the scene at 10th and L streets in downtown Sacramento on Sunday, April 3, 2022. Six people were killed and at least nine others have been injured after a shooting in downtown Sacramento. (photo: Hector Amezcua/SacBee)

The death toll, and the number of wounded, made the bloodbath in the vicinity of 10th and K streets the worst mass shooting in Sacramento’s history.

Police Chief Kathy Lester said the shooting, which followed a fight, left three men and three women dead. Officers have recovered a stolen handgun at the scene, she said, and “we have confirmed there were multiple shooters.”

She said there were no suspects in custody as of Sunday afternoon and stressed that the investigation was at its earliest stage. She said police cameras in the vicinity were able to “capture portions of the shootings.”

The shootings took place around the 1000 block of K Street, near a strip of nightclubs close to such Sacramento landmarks as Golden 1 Center and the state Capitol.

“We know that a large fight took place just prior to the shootings,” said Lester, who was sworn in as chief two weeks ago. She called the level of violence “unprecedented in my 27 years with the Sacramento Police Department.”

The shooting happened just after 2 a.m. The shooting scene was strewn across a two-by-four-block area, with broken glass and police markers on 10th Street from K to L, as officers work the scene; police were also investigating at 12th and K streets.

Family members who had amassed around cordoned-off streets, said the shooting erupted as bars and clubs were letting out for the night. Relatives and social media pointed to videos that showed bodies on the sidewalk after gunfire appeared to come from call speeding north on 10th Street.

Sacramento police said they’re aware of social media videos, including one “that appears to show an altercation that preceded the shooting. We are currently working to determine what, if any, relation these events have to the shooting.”

A law enforcement source said authorities were investigating whether automatic weapons were involved, and had begun studying downtown cameras and license-plate readers for potential clues.

Lester called it “a really tragic, unfortunate situation.”

She called it a “complex and complicated” scene that was “secure.” But she appealed to the public for help in identifying the suspects. “If anyone saw anything, has video or can provide any information to the police department, we are asking for their assistance.”

An information center was set up at City Hall, 10th and I streets, for relatives.

Shooting ‘difficult to comprehend’

It was Sacramento’s second mass shooting in weeks. In late February, a man shot his three daughters and a fourth person to death at a church in suburban Sacramento before killing himself. David Mora, who was subject to a restraining order that prohibited him from having a gun, fired an AR 15-style rifle in the incident.

Sunday’s death toll matches the worst mass shootings in the United States this year, according to a Washington, D.C., group called the Gun Violence Archive. Six people were killed in incidents in Milwaukee and Corsicana, Texas, according to the organization.

Sunday’s violence also matches the worst mass shootings in modern Sacramento history — the hostage drama at the Good Guys electronics store that left six dead, which happened 31 years ago Monday, and the 2001 incident in which Nikolay Soltys murdered six of his family members because he thought they were poisoning him.

Soltys was charged with seven counts of murder — including the murder of the unborn fetus his wife was carrying. He later killed himself in jail.

With 18 in all shot in the rampage, Sunday’s incident generated a fresh wave of demands from gun-control activists around the country, as well as elected officials in California, for more action to curb gun violence.

“Another Sunday, another shooting with mass casualties,” tweeted Fred Guttenberg, whose daughter was killed in the Parkland, Florida, high school shooting in 2018.

Relatives search for loved ones downtown

As word of the shooting ricocheted through Sacramento, friends and relatives of potential victims descended on downtown, desperately seeking information from police.

One man, standing near 10th and J streets, said he feared that his sister’s husband was among those killed. The man had dropped off his sister Saturday night in the neighborhood. When he called her husband’s cellphone Sunday to find the couple, someone else answered.

Two other men standing nearby said they were trying to get information from police about a loved one feared dead or injured. They said his car was still parked by the Citizen Hotel but they couldn’t find him.

Pamela Harris and her daughter-in-law Leticia, who came to the scene with community activist Stevante Clark, had their worst fears confirmed.

They said Leticia’s husband, Sergio, had gone to a nightclub called London late Saturday near 10th and K.

“We just want to know what happened to him,” said Pamela Harris, Sergio’s mother. “Not knowing anything is just hard to face.”

“There’s just too many damn guns,” said Clark, who rose to prominence after his brother Stephon was shot to death by police officers in March 2018.

Minutes later, Pamela and Leticia Harris were taken behind the police tape at 9th and K streets by a law enforcement officer, who began talking to them quietly. Suddenly Pamela Harris cried out and they began hugging each other. Clark confirmed to The Bee that Leticia’s husband had died, and Leticia Harris said the family had just booked an Airbnb for a trip to Mexico.

Just a few feet away, Frank Turner was coming to terms with his own grief.

Turner said his 29-year-old son, DeVazia, who had been a regular at the London club, was among the dead. He expressed frustration and anger that he wasn’t able to get much if any information from police.

The owners of London issued a statement Sunday afternoon expressing grief over the shooting and added that the club “enforces strict security protocols and begins closing procedures at 130 a.m. While this incident occurred a block away, we will continue to make ourselves available to the Sacramento Police Department and provide any information we can during their investigation.”

Leaders share in sorrow

As the shock sank in, elected officials promised to do something to curb violence. But they were clearly grasping for answers.

President Joe Biden in a statement Sunday night offered his condolences to the victims and families, thanked first responders and urged Congress to work toward solutions on gun control, saying: “we must do more than mourn; we must act.”

“Our community deserves better than this,” said Councilwoman Katie Valenzuela, tears streaming down her cheeks at a hastily-called outdoor press conference a block from the shooting. Valenzuela’s district includes downtown.

“This morning our city has a broken heart,” Mayor Darrell Steinberg added. “This is a senseless and unacceptable tragedy.” Although no details were immediately available about the weapon or weapons used Sunday, he called for tougher laws on assault rifles.

Gov. Gavin Newsom and other state leaders quickly weighed in on the shooting.

“What we do know at this point is that another mass casualty shooting has occurred, leaving families with lost loved ones, multiple individuals injured and a community in grief. The scourge of gun violence continues to be a crisis in our country, and we must resolve to bring an end to this carnage,” Newsom said.

Witnesses described a gruesome scene after the gunfire.

“I just saw victims, victims with blood all over themselves running out with glass all over themselves,” said community activist Berry Accius, who rushed to the area after the shooting. “Their loved ones taking their last breath. It was hectic. It was crazy.

“Gun violence is a city problem, a city issue,” Accius said. “Old Sacramento, downtown Sacramento .... People are supposed to be going out, having fun.”

Hours earlier, people had been doing just that. Thousands gathered inside Golden 1 Center for a performance by Grammy-winning rapper Tyler, the Creator. It wasn’t known if any of the victims had been in attendance, but Steve Hicks, a Dublin resident who’d brought his daughters to the show, said he was awakened in his room at the Citizen by the sound of ambulances.

“Geez, this city’s going a little crazy,” Hicks said.

hooting had ‘rapid fire, very rapid fire’

Sue Lockwood, 67, said she heard the shooting from her tent on the east side of City Hall, where she is living.

“A lot of guns going off and they were big handguns, they weren’t rifles,” Lockwood said, adding that she served in the Navy and was familiar with gunfire. “I was sitting up in my tent and I zipped it up and laid down. There was no foxhole. It went on for quite a while. There was a lot of gunshots. It wasn’t just some drunk guy.”

Video posted on Twitter showed people running through the street as the sound of rapid gunfire could be heard in the background. Video also showed that multiple ambulances had been sent to the scene with officers and other first responders tending to victims.

Ross Rojek had dinner downtown Saturday night at Grange Restaurant & Bar. Rojek, who owns Capital Books near the corner of 10th and K streets, said it was a notably busy Saturday night — largely from the bar and club scene in the area. Lately, he said, there’s been a “constant flow” of people at night.

“It gets really chaotic at night,” Rojek said. “During the day and the evening, it’s still a great place to go hang out, go out dinner, and shop.

“It’s just, the night is getting there.”

He woke up to news of the shooting and, like many others, went searching for information. His bookstore, which was cordoned off by crime scene tape, was closed Sunday, he said.

Rojek said he’s not deterred: “I’m not going to give up on the area.”

Steinberg sought to calm fears that downtown Sacramento was too dangerous for visitors. Golden 1 Center hosted major concerts Friday and Saturday, and the Sacramento Kings are scheduled to play the Golden State Warriors Sunday evening.

Two performances of the Broadway musical “Wicked,” a matinee and evening show, were set to go on as scheduled Sunday at the SAFE Credit Union Performing Arts Center. Broadway Sacramento, the organization presenting the shows, said police concluded the area was safe for theater-goers.

“Obviously, people look at this and say, ‘Oh my God, how dangerous is downtown?’” the mayor said. “Well, we want people to come downtown, and safely.”

He said the city is investing $8 million in federal COVID relief dollars in public safety, including enhanced lighting and other efforts. He said the City Council recent invested $5 million in youth programs aimed at curbing violence.

“I want to encourage our people to come downtown,” Steinberg said, adding: “Don’t stay out ‘til 2 in the morning.”

An eerie, tense mood in downtown Sacramento

Still, a tense, fraught air hung over much of downtown during the morning amid signs of normalcy. As USA Track & Field masters runners finished their cool-down laps following a 10-mile road race, tourists sped away from their hotels, eager to bypass crime-scene tape. Cars that were stranded at the intersection of 10th and K streets were being towed away.

Steve Bell, an Atlanta resident who ran in the road race, said sirens woke him up at 2:30 a.m. But he didn’t think much of it until hours later, when his wife texted him in a panic. Although the race proceeded, he couldn’t help but think of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing.

“The other scary thing (was) not knowing where that shooter was,” Bell said. “Is this guy going to start taking runners out?”

Paul Slaikeu and his husband Martin, who were staying at the Citizen Saturday night in anticipation of a roller-skating competition in Citrus Heights, said they were awakened at around 2 a.m. by “a pop-pop-pop sound.”

“We heard a lot of popping and saw some flashes of light on the ceiling,” said the Healdsburg resident. “From our vantage point, there was a woman on the ground being tended to.”

He added that the gunfire was “rapid fire, very rapid fire.“

But even as loved ones were converging on the central city to scour for information, others were arriving downtown for regularly scheduled events late Sunday morning. Just east of the shooting scene, the Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament was holding worship services, with congregants being told to enter through a rear door.

Meanwhile, families were strolling through Capitol Park, walking their dogs — close enough to the crime scene that one could see the blue police markings that indicated the locations of shell casings. Runners were jogging down L Street. Travelers were checking out of hotels, dragging rolling suitcases behind them.

By noon, dining areas in downtown were bustling with brunch traffic — two blocks from the shooting scene near Cesar Chavez Plaza, the sounds of DJ music was booming across from City Hall.

At dawn, Dennis Young, a 73-year-old downtown resident, was walking his 6½-year-old Chihuahua mix Barkley near the shooting scene early Sunday. He said he carries pepper spray to remain safe in the area and that the incident is the worst he has seen.

“I keep my distance, no guns or anything, but I see everything from hypodermic needles,” Young said. “Yesterday, I saw a steak knife and somebody stabbed on the sidewalk. It’s just issues, it’s just issues.”

In the afternoon the large police presence that blocked off an eight-block area, was reduced to two as police continued to process the scene. That closure kept the Sacramento Regional Transit’s Blue Line train offline from Globe to 13th Street Station.

Young said he began his walk about 6 a.m. at Capitol Mall and saw a huge police presence, and initially thought it was for a road race.

The race — the USA Track & Field event, conducted by the Sacramento Running Association, went on as scheduled, with an oddly upbeat atmosphere. Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run” played over the loudspeakers at the starting line. The planned route had the runners crossing the Tower Bridge to West Sacramento, away from the shooting scene.

“I read about it, I still came,” said Cora Vang, a Sacramento resident who heard about the shooting Sunday morning before driving in with her running mates. “I didn’t tell them, though, about it until we were on our way here.”

A demonstration in Washington DC in February. (photo: Paul Morigi/Getty Images/We The 45 Million)

A demonstration in Washington DC in February. (photo: Paul Morigi/Getty Images/We The 45 Million)

A planned demonstration in Washington will bring attention to the issue as Biden is said to be weighing debt forgiveness

During the pandemic, a pause on federal student loan payments set in March 2020 temporarily lifted the burden for Kapadia, 40, though he continued to make payments on smaller loans with private lenders.

“I can’t describe the amount of relief it’s given me. It’s been life-changing,” Kapadia said. “Prior to the moratorium, I would burn through every single check, I’d have nothing left at the end of the month. I’d be going into credit card debt.”

The pause is scheduled to expire on 1 May after two years in place, and Kapadia – who is one of nearly 45 million Americans with student debt – said that he was “terrified” at the idea of payments getting started again, especially since inflation has meant his cost of living has gone up. Over the last decade, Kapadia has managed to pay off most of his principal loan amount, $80,000, but is still working to pay off the $50,000 of interest his loan has accrued.

“Having a huge chunk taken out immediately and put towards interest payment, despite having paid back the full principal balance, I just find that to be usury and cruel, really,” Kapadia said.

Kapadia is joining hundreds of borrowers who are heading to Washington DC on 4 Aprilto protest against student debt and advocate for Joe Biden’s cancellation of student loans. Among the 60-plus organizations taking part are MoveOn, the Working Families party, NextGen America and the Hip Hop Caucus.

Activists say the expiration of the loan pause and the economy’s high rate of inflation mean there is even more urgency to address the student debt crisis.

The Debt Collective, a union of borrowers, is organizing the rally and said protesters from across the country will be traveling to DC for the event. The organization said that if Biden allows payment on federal loans to start again on 1 May, the collective will commence a debt strike once payments resume – a tactic that the group has coordinated before.

“There’s really no good reason to restart payments, especially when household budgets are already being squeezed by the cost of living going up,” said Thomas Gokey, legal and policy director for the Debt Collective. “To put an additional, on average, $400 student loan payment on millions of households is really adding a lot of pain when people are already experiencing it quite a bit.”

The concern is shared among many with student debt: A survey of more than 20,000 borrowers by the Student Debt Crisis Center conducted in February found that 92% of fully employed borrowers are concerned about being able to afford their student loan payments because of inflation.

Along with the general rise in cost of living affecting borrowers, inflation could affect the interest rates of those who have debt with private lenders. While many with federal student loans have fixed interest rates, those who have debt with private lenders can be subject to increased interest rates after the Federal Reserve raised interest rates by a quarter percentage point this month.

When he was running for president, Biden advocated for canceling at least $10,000 in debt for each person with student loans – a plan that was first proposed by Senator Elizabeth Warren.

While the White House and the Department of Education has been mum on any plans around extending the pause, Biden’s chief of staff, Ron Klain, suggested that the administration is considering policies that go beyond a moratorium extension.

“The president is going to look at what we should do on student debt before the pause expires, or he’ll extend the pause,” Klain said in early March, adding that Biden is “the only president in history where no one’s paid on their student loans for the entirety of his presidency”.

“The question whether or not there’s some executive action on student debt forgiveness when payments resume is a decision we’re going to take before payments resume,” he said.

On Thursday, a group of nearly 100 lawmakers sent a letter to Biden urging him to extend the pause on federal student loans until at least the end of the year and ultimately work toward debt cancellation. The lawmakers cited Klain’s recent comments as “encouraging to millions of borrowers across the country”.

Advocates have noted that the momentum around student debt cancellation has continued to grow as the pause on federal loans, which was first undertaken by Donald Trump’s administration, has been renewed several times, giving borrowers a glimpse at relief.

“We’re getting to a point with loan pauses that one of the things that [the administration] talks about is wanting to have a smooth transition to repayment,” said Natalia Abrams, president and founder of the Student Debt Crisis Center. “We’ve gotten to a point that one of the only ways to do that is cancel student debt.”

Kapadia said he was hopeful that the administration would consider cancelling student debt, “leveling the playing field”, but was anxious about the amount of time the White House is taking to act.

“You’ve got folks making payments their entire adult lives,” he said. “[Biden] has the complete authority to do something to drastically to change millions of lives, and he’s sitting on it.”

Then-Maj. Richard Foy drives Oct. 4, 2021, in a part of Dallas designated by the police as a city grid needing special attention to reduce crime. (photo: Cooper Neill/WP)

Then-Maj. Richard Foy drives Oct. 4, 2021, in a part of Dallas designated by the police as a city grid needing special attention to reduce crime. (photo: Cooper Neill/WP)

At least nine jurisdictions either plan to or have adopted the crime- reduction strategy known as ‘place network investigations’ — a model that examines geographic connections that allow crime to flourish.

In the months preceding the shooting, Louisville officers had studied a model known as “place network investigations.” The then-novel approach pioneered by an academic posited that crime could be curbed if police and other community partners focused on geographic connections in areas plagued by violent crime. It is the latest in a long line of U.S. policing philosophies that have used data to target crime concentrated in small areas known as hot spots.

In early 2020, a newly formed Louisville police squad installed cameras and tracking devices to surveil several vacant homes that officers believed were linked to a drug operation, according to a review of city documents. One officer was later fired and accused of lying about some of the evidence used to connect Taylor — who lived over 10 miles away — to her ex-boyfriend’s alleged drug activity.

“It was an epic failure on so many levels,” Sam Aguiar, a lawyer who has represented Taylor’s family in litigation against the city over her death, said of the city’s place-based plan. “It was destined to fail from the start.”

At the time of Taylor’s death, Louisville was one of three cities to try the strategy. It later scrapped the initiative. Now, at least nine jurisdictions either plan to or have already adopted a similar model, according to a Washington Post review.

Tamara Herold, an associate professor at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas and the architect of the place network investigations model, said that Taylor’s death should not be viewed as a consequence of the strategy. Louisville officers have said they were inspired by Herold’s research. She said she shared information with them about the strategy, but had no involvement in how they conducted their investigations or the decisions they made.

“This particular search warrant resulted in a horrific tragedy. It is not a defining feature of this initiative,” she said. “The defining feature of this particular initiative is really to bring in city resources to remove the need for continuous police enforcement.”

In statements provided to The Post, officials from some departments pursuing the strategy have stressed that it has shown great potential to reduce crime.

In Philadelphia, police spokeswoman Jasmine Reilly called the plan “a holistic approach to crime reduction.” In Las Vegas, police spokesman Larry Hadfield said the collaborative effort among city agencies has “substantially reduced gun-related victimization” and has helped direct “resources to our most vulnerable communities.” And in Tucson, Police Chief Chad Kasmar has called it “a comprehensive and meaningful plan to reduce violence,” saying that his department is “a staunch supporter of evidence-based, science-informed policing.”

Studies of Herold’s strategy have so far been limited, but the private fund Arnold Ventures, which invests in social causes, has pledged more than $2 million for training efforts and evaluations of the program in Philadelphia, Las Vegas, Tucson, Denver, Wichita, Baton Rouge, and Harris County, Tex. (A Baton Rouge police spokesman said plans for the program were paused in December because of a shortage of officers.)

“Policymakers, mayors and city councils are looking for answers of, ‘How do we sustainably decrease violence?’ ” said Walter Katz, the vice president for criminal justice at Arnold Ventures.

In Dallas, Police Chief Eddie Garcia said that before he took over the department in 2021, he consulted with criminologists, telling them: “I want to come up with a scientifically based crime-reduction strategy from the best that criminology has to offer.” In 2020, Dallas had ended the year with 251 homicides, its highest count since 2004.

Those discussions led Garcia to turn to place network investigations alongside a traditional hot-spot-policing effort.

“This is not just about making arrests and police proactivity,” he said of the place network strategy. “It’s about lighting, streets, traffic, parks and [recreation], schools, the city attorney’s office and holding landlords accountable — I mean, you name it. It’s a holistic approach about truly trying to invest in that neighborhood and take care of a problem.”

Police chiefs under pressure to quickly reduce crime have long turned to plans prioritizing small areas of a city that account for outsize rates of violence.

One of the earliest uses of hot spots was in Minneapolis in the late 1980s during an experiment co-led by the criminologist David Weisburd. That work identified 110 clusters of addresses with the highest number of calls to police. Officials analyzed the calls to determine the “hottest” times and assigned officers to patrol half of the areas for at least three hours a day. In the end, hot spots with increased patrols reported reductions of between 6 and 13 percent in the number of calls about crime.

“As opposed to having to just ride around in incoherent ways, have them go to the hot spots,” said Weisburd, a professor at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., and at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “Let’s use police patrol in a more rational way.”

The success of such early experiments gained notice. The strategy soon took hold in police departments across the country as officials routinely found that a small percentage of city blocks accounted for significant portions of citywide crime numbers.

As the use of hot spots spread, Anthony Braga, now the director of the Crime and Justice Policy Lab in the department of criminology at the University of Pennsylvania, reviewed 78 tests of hot-spot-policing interventions conducted in more than two dozen U.S. cities and in eight countries from 1989 to 2017. He found that nearly 80 percent of the tests reported “noteworthy crime and disorder reductions.”

In his review, he noted that just 10 percent of hot-spot studies measured the effects of such policing on community residents. Those that did found little detriment to community and police relations, but Braga noted that some initiatives could lead to more men of color being swept into the criminal justice system — a point also made by critics of such programs.

“Flooding the zone isn’t going to solve the problem of poverty or economic stagnation in certain communities,” said Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, a law professor at American University in Washington and author of the book “The Rise of Big Data Policing.”

Ferguson suggested that greater funding of schools and jobs programs would have longer-lasting positive results. “But they’re police chiefs,” he said. “They don’t actually have the tools to do these things, so all they can come up with is an answer that sounds good, which is: ‘Don’t worry. We have a new policing strategy’ — which is really just the old policing strategy with a new name.”

Before taking over the Dallas department last year, Garcia consulted with criminologists at the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) to draft a crime-reduction plan and to oversee an effort to evaluate its results.

The first step would be to divide the city into tens of thousands of grids, about the size of football fields, and to flag roughly the top 50 grids for violent crime. Officers would patrol those areas with greater visibility and, in some grids, use investigative tactics to gather intelligence.

Also within the 29-page plan was the place network investigations model that promised to “identify and disrupt networks of criminogenic places.”

“It’s a relatively new theoretical advance in our understanding of crime and place,” said Michael Smith, a professor in the department of criminology at UTSA. “It’s certainly not been around as long as hot spots policing has been around. But I think it has shown great promise.”

Throughout the new Dallas plan, Garcia cited the research of Herold — whose “place-based investigations of violent offender territories (PIVOT)” model was first used in Cincinnati in 2016 as an experiment to combat gun violence. There, she and police officials developed a scoring system to flag “micro-locations” that were “chronically violent,” according to a summary. The strategy relied heavily on intelligence gathering — surveillance, undercover policing and the use of confidential informants — and leaned on community partners. Drug crime was one factor often driving gun violence, Herold found.

In the Cincinnati experiment, street parking was eliminated after the team concluded that the spaces were used to conceal drug transactions. Streetlights were installed. Blighted buildings were demolished. When investigators examined one residential area used by gang members, they found guns and ammunition hidden in tall grass with children playing nearby. So, they mowed the grass.

From 2015 to 2016, the pilot micro-location program reported a drop of more than 80 percent in the number of shooting victims. Capt. Matthew Hammer of the Cincinnati Police Department said that the strategy remains effective but that the city, which had a record number of homicides in 2020, has struggled to scale up the program. It is in use in just four locations.

“The amount of resources that it takes to work through some of these challenges and to untangle some of these problems is extraordinary,” Hammer said.

Officials in Louisville had embraced the strategy after high-ranking members of their police department attended a presentation in June 2019 about Herold’s model. In October, they traveled to Cincinnati to observe meetings about the strategy. By December, Louisville had created its own “Place-Based Investigations Squad.”

The goal, according to documents later made public by Louisville, was to “dismantle the entire physical infrastructure, or place networks, used by offenders.” The city planned to use “all city resources” to do so, focusing on areas of chronic violence and then disrupting networks of violence. Then, officials would create “sustainable solutions” for public safety.

By New Year’s Eve, city leaders assigned five officers to the squad and selected its first target: a “microcell” in West Louisville comprising several blocks. In the middle was Elliott Avenue, the site of an increase in aggravated assaults and drug-related crimes.

During a May 2020 interview with the Louisville police department’s public integrity unit, then-detective Josh Jaynes described how the squad decided on the location.

“It’s like a hot spot,” he said.

Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old hospital technician, had no criminal record and lived more than 10 miles outside the “microcell” under police scrutiny. Yet she quickly became ensnared in what Jaynes later said in the investigative interview was “probably one of the bigger casefiles I’ve ever been a part of.”

On Jan. 2, 2020, Louisville police officers installed a camera on a utility pole, pointing the lens west at South 24th Street and Elliott Avenue. Within one hour of the camera’s activation, detectives observed as many as 20 cars drive to and from 2424 Elliott Ave. The constant flow of cars there, they noted, was “indicative of narcotics trafficking.”

“Just [a] typical trap house,” Jaynes remarked in his interview. “People coming and going.”

One of the cars spotted was a white 2016 Chevrolet Impala carrying Jamarcus Glover, who had a felony record for selling cocaine in Mississippi. The car was registered to Taylor, his ex-girlfriend, although detectives did not report seeing her in the vehicle that night. In later reports detailing the camera’s surveillance, detectives documented one sighting of Taylor with Glover, along with reports of her black Dodge Charger seen “numerous times” in front of the Elliott Avenue home.

On Jan. 3, 2020, police arrested Glover on charges related to guns and drugs recovered from the Elliott Avenue home and two other houses, and he was booked into jail, from where he called Taylor. After his release, the squad installed a GPS tracking device on his car that recorded six trips to 3003 Springfield Dr., Taylor’s apartment complex across town. A detective photographed Glover leaving Taylor’s apartment with what appeared to be a U.S. Postal Service package in hand.

The squad developed a theory that Glover was using Taylor and her apartment to store his drug money. “They get other people involved, and it’s usually females,” Jaynes said in his police interview.

In March, Jaynes prepared the request for no-knock warrants to enter 2424 Elliott Ave. and two neighboring houses, along with Taylor’s apartment on Springfield Drive. For Taylor’s apartment, Jaynes wrote that he had “verified through a U.S. postal inspector that Jamarcus Glover has been receiving packages at 3003 Springfield Drive #4.”

Shortly after midnight on March 13, 2020, a Louisville SWAT team raided 2424 Elliott Ave. and recovered “a large amount of suspected crack cocaine and suspected Fentanyl pills” hidden in a bag in a tree in the backyard, along with “other evidence of narcotics trafficking” including a digital scale and large amounts of cash, according to documents. Glover was arrested at the house.

Across town, officers carried out what they have described as a “knock and announce” entry into Taylor’s apartment. Her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, opened fire, and police returned fire, fatally shooting Taylor. Walker, a licensed gun owner, has said he heard banging sounds but did not hear any identification — leading him to think the officers were intruders. Officials said officers found no drugs or money in Taylor’s apartment.

The revelation that a Louisville officer had been shot in the leg left Jaynes feeling unsettled. “It stinks, because I feel like some of our investigation, I would have done it a little bit differently,” he said in the interview with the public integrity unit. “These are our warrants. We all had a hand in this.”

The city later agreed to pay Taylor’s family $12 million. Former police officer Brett Hankison was acquitted this month of charges that he endangered three people when he fired through a wall into an adjacent apartment during the raid.

Eleven months after Taylor’s death, the Louisville Metro Police Department disbanded the squad dedicated to place-based investigations. Jaynes was fired last year after officials said he had lied on the search warrant affidavit about the claim that he had “verified” through a U.S. postal inspector that Glover received packages at Taylor’s apartment complex. Jaynes has sued the department’s merit board in an attempt to regain his job.

In an interview with The Post, Jaynes said he did not lie but was instead relying on information conveyed by a fellow officer. “We’re still pursuing my appeal in circuit court, and I’m going to fight this until I can’t fight no more,” he said.

Jaynes, 39, declined to answer questions about the investigative tactics his team used to focus on Taylor and Glover. But he said he believed in the philosophy behind his team’s work and disagreed with the decision to end the department’s initiative on place based investigations.

“We all had good intentions to implement the strategy and to see results and to see criminal activity decrease,” he said.

The department declined to make Police Chief Erika Shields available for an interview.

“Place Based Investigations (PBI) was a hot-spot-policing strategy intended to help focus limited resources in specific high-crime areas. It is no longer in existence,” said a statement issued by a department spokeswoman. “The Criminal Interdiction Unit, which oversaw the initiative, was revamped under Chief Shields’s administration to align with current intelligence-led policing practices focusing on illegal guns and violent offenders — knowing ‘who’ you are looking for and ‘why’ rather than ‘where.’ ”

Herold has said that Louisville’s attempt to implement her strategy was not fully formed because it had not adopted the core tenet of her program: a board of citywide partners working together to address issues in the places under scrutiny.

Although there was no board in place, emails later released by the city show that the efforts to confront crime on Elliott Avenue extended beyond the police department. In early 2020, a Louisville code enforcement officer emailed detectives assigned to the squad, discussing nuisance orders related to criminal activity at 2424 Elliott Ave. Months after Taylor’s death, the city took ownership of the property.

Aguiar, meanwhile, said he is “absolutely” certain that Taylor would be alive if the Louisville department had not embarked on a place-focused strategy. He said the effort was a misguided attempt to gentrify blighted neighborhoods under the guise of fighting crime — a claim disputed by city leaders.

“They should have never been at Breonna Taylor’s house that night,” he said. “And the only reason they were is because you had five detectives that were given such a minor task that had to consume 40 hours of their workweek and became their life. They just became obsessive over it.”

Back in Dallas, Garcia has a go-to phrase to sum up his long-term vision: weeding and seeding.

“We need to weed the criminal element that’s responsible for violent crime,” he said. “But we’re also trying to seed those same areas with positivity. And that’s part of the plan that I hope doesn’t get missed.”

Dallas officials, citing security concerns, have not publicly identified the roughly 50 hot spot grids or the two locations in which they are testing the broader place network investigations strategy. But The Post was allowed to observe the hot spot strategy in a handful of locations last fall.

Within the grids, opinions from community members ranged from anger to ambivalence, and in some cases, cautious praise.

In southwest Dallas, the hub of Grid No. 6913 is the Super 7 Inn — a long-term-stay motel that police officials say has been plagued by violent crime. One night last fall, an officer in an unmarked car entered license plate numbers of nearby cars into an electronic system — looking for stolen vehicles or other violations. Officers in a marked cruiser soon pulled over a Dodge Charger with an expired registration tag and arrested the driver for outstanding warrants on traffic tickets. A small amount of marijuana was recovered, but officers said the quantity did not meet the threshold for criminal charges.

Two passengers in the car, who were released without being charged with a crime, criticized the policing tactics used in the area.

“They’re not going to protect us,” said Marquez Penagraph, a 22-year-old Black college student. “Ain’t no African American, male or female, thinking they’ve got police help. I guarantee you — they are not.”

Across the street, a small group of men watched from a grassy field as police swarmed the area during the stop.

“This is an area of high crime and high drugs,” said Christopher Middleton, 37, a long-term resident of the Super 7 Inn. “If nobody wasn’t doing nothing, [the police] are not gonna be here, right?”

Across the city, in Grid No. 46649, a stretch of rundown houses on Hamilton Avenue had been flagged by police as one of the city’s most violent areas. One house, painted blue, was boarded up. Three women sat on a bed of blankets and pillows on the porch, playing dominoes.

Lauthasal Langley, 45, said that for the past few months, she has used the porch as a place to sleep and keep an eye on her two friends.

“They think that every time that they see a group of Black folks together, it has to be some drugs going on, or a crime going on,” she said, pointing at the nearby Dallas police officers. “No. We just like to hang out. This is what we do.”

In a command staff meeting in October, police leaders described evidence of an illegal drug operation within the block of Hamilton Avenue. One official suggested that the next step to address the house where Langley and her friends live would be to work with city code enforcement to declare it uninhabitable and possibly tear it down.

Garcia said the place network investigations strategy aims to provide assistance to people such as Langley by coordinating services from multiple city agencies, including the Office of Homeless Solutions.

“Solving a problem isn’t necessarily arresting people,” Garcia said.

At the end of the year, homicides were down by 13 percent, against a 5 percent increase in homicide numbers in major cities nationwide. Dallas officials also reported a citywide 9 percent decrease in violent crime from the previous year.

Smith, the criminologist guiding Dallas’s plan, said the crime reduction program is working. Grids that were prioritized in the fall showed a nearly 53 percent reduction in violent crime from the three-month period before the experiment began, according to summary data. Grids that did not receive enhanced policing recorded only a 12 percent decrease.

And although Smith says he thinks policing efforts within the grids probably drove the citywide decrease in violent crime, he does not yet have the data analysis to prove it.

“Can I as a scientist draw a direct causal line? At this point, no,” said Smith. “This is not a lab. This is the real world. You can’t control for any input that could have contributed to a crime drop.”

Critics caution that any police-gathered data should be viewed with the highest level of scrutiny because of the danger of confirmation bias.

“The data that they have about where crimes are committed and by whom is all based on police decisions about where and how to collect the information,” said Carl Takei, a senior staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union. “And so it often becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy that the police will focus a great deal of resources on certain Black and Brown neighborhoods.”

Back in Grid 6913, at the Super 7 Inn, Middleton and his partner, Brittney, have lived at the motel since last summer. The sound of gunfire from a drive-by shooting across the street in January left the couple and their two young children feeling rattled. But Middleton said they have felt safer because of the hot-spot-policing effort.

“This motel complex used to have a lot of unsavory characters,” he said. “The dope dealers, they’re gone. Either they were arrested or they got smart and left.”

Deputy Chief Richard Foy, who oversees the police department’s South Central and Southwest divisions, proudly credits the officers who patrol hot spots such as Grid 6913. He calls them his “crime-fighters” — a superhero-like reference to the men and women working the high-priority shifts.

“On violent crime, we kicked ass,” Foy said on New Year’s Eve as he analyzed numbers on his work computer. “Just because we have a successful year doesn’t mean that we’re done. In a perfect world, crime is zero.”

Pakistani paramilitary troops stand guard with riot gears outside the National Assembly, in Islamabad, Pakistan, Sunday, April 3, 2022. (photo: Anjum Naveed/AP)

Pakistani paramilitary troops stand guard with riot gears outside the National Assembly, in Islamabad, Pakistan, Sunday, April 3, 2022. (photo: Anjum Naveed/AP)

The decision to break up the parliamentary session ahead of the vote marked a stunning attempt by Khan to remain in office despite widespread economic and political discontent across Pakistan. A successful no-confidence motion would have likely seen the formation of a new government. Instead, the country looks headed to fresh elections – giving Khan a potential new lease on keeping the job.

The opposition says it will challenge the move in the country's Supreme Court. The court said it would take the challeng up on Monday, but it remains far from clear how the court may rule.

"Absolutely unprecedented," said Amber Rahim Shamsi, an analyst and former broadcaster who is now the director of the Center of Excellence in Journalism at the International Business Administration. "This is a constitutional crisis."

"This is Imran Khan changing the nature of the game," she said. "The opposition had the numbers, and it was pretty much a sure vote. Had it gone through, the prime minister would have been removed from office."

In a day of remarkable political theater in Pakistan's legislature, Information Minister Fawad Chaudhry accused the opposition of treason, while Khan's allies rushed to the floor of the chamber shouting, "Friends of America are traitors to their country!"

Khan claims Washington is plotting against him

The political crisis stems from frustrations over economic mismanagement, rising prices and concerns over the direction Pakistan's foreign policy has taken under Khan's leadership. Khan and his allies allege that Washington is trying to overthrow his government, and that his political opponents are doing Washington's bidding by trying to oust him.

Khan claims a cable from the Pakistani embassy in Washington, which relays a conversation with a senior State Department official critical of the prime minister's recent actions, as proof of U.S. meddling. American officials have denied any suggestion that they are seeking to unseat his government.

The disarray in Pakistan, a nuclear-armed nation of 220 million people, comes at a moment of deep economic anxiety in the country. As negotiations continue between Khan's government and the International Monetary Fund over a $6 billion bailout package, pandemic-linked inflation and concerns over the Russian invasion of Ukraine have combined to push up the price of food and fuel.

Khan's woes began after it appeared that the military had signaled it was no longer supporting the prime minister over allegations of economic mismanagement and disagreement with his foreign policy views.

Khan openly celebrated the Taliban's seizure of Afghanistan last year, saying the regime change meant that Afghans had "broken the shackles of slavery." He also met President Vladimir Putin as Russia invaded Ukraine. The signaling by Pakistan's most powerful institution allowed the opposition to start pushing forward with efforts to oust him. Military leaders, however, have maintained they are neutral parties in the country's political landscape.

In early March, the opposition put forward a no-confidence motion. At least one party that formed Khan's governing coalition supported the move last week, robbing him of his political majority.

Khan and his allies responded with threats of social disgrace, warning those who planned to vote against him that "no-one will marry your children." They appealed to the Supreme Court to decide on whether lawmakers could vote against their own party leader – the court has not made a decision.

In a devout Muslim nation, Khan has insisted he is fighting for Islam, while also claiming that Washington is trying to remove him from office.

That move appeared to be, in part, an attempt by Khan to shape a narrative that will help propel him back into power, according to Shamsi.

"He thinks he's built enough of a narrative to counter the accusations of misgovernance, to counter the inflationary pressures and the ... accusations of mismanagement," she said. "That it is these emotive messaging that will appeal to the public."

Khan said he'd win the vote, then shifted course

Khan had insisted on television that he would win the vote, but then on Saturday he dismissed the vote as part of an American conspiracy in an interview with The New York Times and said he would not accept the result. By Sunday, with the no-confidence motion set to succeed, Khan dissolved parliament.

His supporters claimed they were saving Pakistan's democracy. The parliamentary secretary for law and justice, Maleeka Bokhari, said they had stopped "a no-confidence motion that was moved unconstitutionally on the instigation of a foreign power in collusion with members of parliament of opposition and I think no democratic state, no independent sovereign state, can allow the removal of the prime minister through such unconstitutional means."

Pakistan's opposition vowed to challenge the move.

"This cannot happen like that in the daylight," said Marriyum Aurangzeb, a spokeswoman for the PML-N, a major opposition party. "This is the violation, blatant violation of the constitution of the country."

The crisis has put a fresh spotlight on the influence of Pakistan's army in domestic politics, said Mosharraf Zaidi, a columnist and director of Tabadlab, a policy think tank based in Islamabad.

The army's "stakes in this have been vastly and dramatically enhanced because it chose to intervene in the 2018 election to secure a first time prime ministership for an individual that was long seen as the only viable alternative to the traditional political families," Zaidi said. "Now that that experiment has come full circle. They are having to work with those traditional political families to extricate themselves of the political, national security and foreign policy liability that Imran Khan is."

Summer Lake Wildlife Area. (photo: Emily Cureton Cook/OPB)

Summer Lake Wildlife Area. (photo: Emily Cureton Cook/OPB)

Velvety ferns hugged a lush river bank. Under the water’s clear surface, aquatic plants waved and shone like green hair. Not far from here, springs bubble up from the ground, flowing into the Ana River and powering one of Oregon’s most iconic wetlands — Summer Lake Wildlife Area.

St. Louis, a biologist, was the wildlife area’s manager for more than 30 years. He retired from the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife in 2020, and remains an avid guide to the 19,000-acre spread of state land, where people have documented more than 250 bird species.

“We’re right here in the Pacific flyway,” St. Louis said on a recent tour.

Flyways are the main routes birds use to move north and south across North America. The wetlands around Summer Lake provide an important rest stop in the mostly dry and inhospitable expanse of the continent’s Great Basin.

Scanning the horizon with his binoculars, St. Louis spied more than a dozen species on a February day. Among them, a gaggle of tundra swans who spend their summers in the Arctic, a pair of sandhill cranes and some 15,000 snow geese in a constant state of roaring chatter.

“They’re probably chewing each other out,” St. Louis said of the geese. “They’re a quarrelsome lot.”

Marshes at Summer Lake became Oregon’s first wildlife area in 1944, with priorities to protect bird habitat and public hunting grounds. While the area’s water source begins with gushing freshwater springs, it ends in a reservoir made salty by evaporation. Summer Lake, and Lake Abert to the southeast, are the two surviving remnants of a much larger, ancient water source that once covered this part of Southern Oregon’s Lake County.

Scientists believe Summer Lake has been around for at least 10,000 years. Its main source springs can release water that’s been percolating through rocks for a millennium. This slow-moving water cycle provides a drought-resistant lifeblood in a region with very little annual rain and increasingly less snow. But, current state management of groundwater puts the Ana River springs in danger of disappearing within a generation. Their flow has been in steady decline since wells began pumping water to nearby hay farms.

Environmental advocate and attorney for WaterWatch Lisa Brown said the state agency managing water supplies has stood by for decades, allowing agriculture in the Fort Rock basin’s Christmas Valley to doom a prized public resource.

“It’s alarming that we have a plan in place in Oregon to basically dry up Summer Lake,” Brown said.

The nonprofit WaterWatch often challenges decisions by the Oregon Water Resources Department. In 2014, Brown sounded alarms that led to a moratorium on new water rights in Harney County, one of Oregon’s most overdrawn basins. Now, Brown worries that Ana Springs, and by extension Summer Lake, will become the next casualty of a timid state agency that fails to reel in water rights holders.

“It’s really a relic of an old outdated approach,” she said. “This should be a lake that Oregon is proud to have and that we strive to sustain.”

Foreseeable conflict

Due to declining groundwater, the state Water Resources Department stopped allowing new irrigation water rights in Lake County’s Fort Rock basin in 1990. Leading up to that freeze, a state scientist studied the area’s aquifers. His report matter-of-factly describes how farming at 1980s levels will likely dry out natural springs feeding Summer Lake, and groundwater flowing to the Upper Deschutes Basin. The scientist estimated total depletion might take decades, or it might take a century.

“That vagueness is for a reason,” said Donn Miller, the hydrogeologist who wrote the state report and retired from the Water Resources Department in 2010.

Miller believes the concept in his report is solid, but a timeline is hard to predict. Human-caused climate change adds another layer of uncertainty.

“That’s a spooky factor,” Miller said of more recent climate change models. “It’s not sounding good.”

Miller’s research predicts that before Ana Springs go dry, desert plants with deep roots will wither and die. He estimated that this will happen at around 50 feet of groundwater decline, a point at which current state regulations say the Water Resources Department might finally step in. The springs would be lost if groundwater declined another 20 feet beyond that.

“There’s no reason to believe the analysis is incorrect or unreliable,” Water Resources Department groundwater manager Justin Iverson said in an email.

So far, the state has tracked a 17-foot drop in groundwater in the basin, with the majority of it, some 13 feet, occurring since the 1990 moratorium on new irrigation water rights.

More than 30 years later, water use by agricultural wells has only increased, with the potential for dramatically more pumping under existing water rights. In Lake County, the regional economy is more reliant than ever on alfalfa hay farming, as the crop’s value soars through export markets to Asia and the Middle East.

A foreseeable conflict over the fate of Summer Lake, which state water managers have long known about and failed to prioritize, will pit people who value Ana Springs against those whose communities depend on farming in the Christmas Valley.

Oregon Water Resources Department deputy director Doug Woodcock acknowledged that wells in the region are lowering the water table. He denied an intentional plan to favor farmers.

“That’s just the nature of groundwater hydrology,” Woodcock said in an interview in March.

State studies of two Eastern Oregon basins — Summer Lake and Malheur County’s Cow Valley — suggest the department has a practice of allowing irrigation pumping to dry up surface water connections where agricultural interests dominate the landscape.

State regulators don’t track how much water Fort Rock basin farmers use. About 99% of the wells in the area aren’t required to measure and report what they take out of the ground.

“We have not been working down in that area because we have more critical areas to evaluate in the state right now,” Woodcock said. “The department does have a charge to manage the area sustainably and as we can get to it, we will.”

The agency said it does plan to eventually track the water usage with remote-sensing technology through funding provided by the Oregon Legislature in 2021, but it’s not clear when those efforts will start.

Exporting water

While the state has not tracked regional water usage in Christmas Valley, some hay farmers using the water have. Their analysis of electrical power records indicates the region’s farms are pumping out about 20% more water than they were in 1990. Under the existing water rights, farmers in the future could legally draw more than double the amount people were taking out when Miller first predicted spring declines.

Dan Jansen is a Christmas Valley hay grower who wants to conserve more water, and avoid a crackdown on water rights.

“If we get cut back here, it’s gonna be devastating,” he said. “This will be a ghost town. There will be nothing but blowing sand here if we don’t have the alfalfa crops.”

As president of the Lake County Hay Growers Association, Jansen has been pushing his fellow growers for more discussion of the region’s groundwater declines. He wants farmers to agree there’s a problem, or likely will be, and pursue conservation measures to increase efficiencies. He has spoken out against irrigation happening illegally, either intentionally or more often, he said, because growers misunderstand the limits of their water rights.

Recently, water use monitoring and enforcement by the state water department has been virtually nonexistent in Christmas Valley. Beginning in 2000, the department entered a two-decade span without issuing any notices of violation. In 2020, the local enforcement arm of the agency — known as the watermaster — took stock of the valley, and found about 1,400 acres being irrigated without a water right, and one clear case of illegal use. The department broke its dry spell on enforcement and sent 25 warning letters.

Jansen commended the shift. His goal is to avoid more drastic state interventions, which could diminish legal water rights across more than 50,000 acres.

Farming didn’t exist in the Christmas Valley until the 1970s and ‘80s, Jansen said. Now, he described a tight-knit community largely made up of multi-generational families.

“It’s really about waking up in the morning and going out, and working your tail off and having something in the barn to show for that,” he said.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture valued Lake County’s hay crops at around $44 million in 2017, the last year for which figures were available. Since then, the sale price of alfalfa has boomed. Jansen estimated that in more recent years, the county’s irrigated farms conservatively translate to around $75 million in annual gross revenue.

The basin’s harsh conditions and temperature extremes are part of what makes the hay so valuable in an international market.

“This is the best climate, probably in the world, for this crop,” Jansen said.

Cold nights slow down the growth of the hay, he explained, which makes it more nutritious as livestock feed. The bales fetch a premium price in many Asian countries, like China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

“Now we’re starting to get a lot of Middle East countries that are buying because they don’t have any water to grow it,” he said. “We’re exporting water in a sense.”

A thousand cuts

While some hay farmers are preparing for a future where their livelihoods will be affected by declining groundwater, the reality is already starting to show for the wildlife area.

The state Department of Fish and Wildlife knows Ana Springs are declining, and will likely continue to do so.

“We are accustomed to managing with scarcer water,” the wildlife area’s current manager Jason Journey said in an email.

This means allowing some wetlands to dry out in the spring and summer, whereas in the past they would have had water all year. Journey said the bright side is that the dry periods allow managers to clear or burn invasive vegetation, fine tuning the habitat to appeal to certain bird species.

Former wildlife area manager St. Louis said it’s difficult to judge exactly how migratory birds are reacting to less water, without a widespread geographical study. He worries that refuges like Summer Lake are disappearing all over the world.

“It’s like death by a thousand cuts. And it’s gonna take a lot to figure out some solutions to reverse that,” he said.

St. Louis said the conflicts brewing underground in Lake County are a matter of time. Water managers in the state face problems that could become catastrophes in 10, 20 or 50 years — which can seem far off when other parts of Oregon are seeing urgent collapses in the water table.

But when compared to a lake that’s 10,000 years old, the decades until Ana Springs dry up are only a fleeting moment.

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.