Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

ALSO SEE: Thousands Lie in the Street in Warsaw,

Calling on US to Close Ukrainian Sky

Free people of a free country!

Today we were all with you - on your streets, in your protest. And all together we tell the occupiers one thing: go home while you can still walk.

The Russian invaders entered Slavutych and faced the same reaction there as in the south of our state, as in the east of our country.

Ukraine is united in its desire to live freely, to live independently and for the sake of its own dreams, not other people's sick fantasies. Every day of our struggle for Ukraine, every manifestation of our resistance in all areas the occupiers have entered so far proves that Ukraine is a state full of life, which has historical roots and moral foundations throughout its territory.

Nothing they do will help the occupiers in the Ukrainian territory they temporarily entered. Disconnection of our television and activation of passionate nonsense speeches by Moscow TV presenters, leaflets with propaganda, distribution of rubles. Rubles, which in Russia will soon be weighed instead of assessing them at face value.

Bribing outcasts whom the occupiers are looking for in all the dumps to portray the allegedly pro-Russian government will not help as well.

The answer to Russian troops will be one - hatred and contempt. And our Armed Forces of Ukraine will inevitably come.

That is why ordinary Ukrainian peasants take captive the pilots of downed Russian planes that fall to our land. That is why our "tractor troops" - Ukrainian farmers take Russian equipment in the fields and give it to our Armed Forces of Ukraine. In particular, the latest models that Russia has tried to keep secret. And now the occupiers leave them on our land and just run away...

Actually, they do the right thing. Because it is better for them to escape than to die. And there are not and will not be other alternatives.

Everyone in Ukraine has united and has been devoting all their energy to the defense of our state for more than a month already. Together with the Armed Forces, together with all our defenders, together with our National Guard.

I would like to once again congratulate the National Guard of Ukraine on its day with great respect. I am sincerely grateful for everything you do to protect the state, to protect Ukrainians! Thank you for all the steps to victory that will come and that were made possible thanks to you.

Today I presented awards to soldiers of the National Guard who distinguished themselves in battles with the Russian occupiers. I also awarded the rank of brigadier general to five colonels of the National Guard of Ukraine.

In total, during the full-scale war since February 24, 476 soldiers of the National Guard have been awarded state awards already.

I also spoke today with Polish President Andrzej Duda. Twice. About our people who found protection in Poland. And the need to strengthen our common security. Security of our states. Security for all Europeans actually.

What is the price of this security? This is very specific. These are planes for Ukraine. These are tanks for our state. This is anti-missile defense. This is anti-ship weaponry. This is what our partners have. This is what is covered with dust at their storage facilities. After all, this is all for freedom not only in Ukraine - this is for freedom in Europe.

Because it cannot be acceptable for everyone on the continent if the Baltic states, Poland, Slovakia and the whole of Eastern Europe are at risk of a clash with the Russian invaders.

At risk only because they left only one percent of all NATO aircraft and one percent of all NATO tanks somewhere in their hangars. One percent! We did not ask for more. And we do not ask for more. And we have already been waiting for 31 days!

So who runs the Euro-Atlantic community? Is it still Moscow because of intimidation?

Partners need to step up assistance to Ukraine. These are the words: partners need! Because this is the security of Europe. And this is exactly what we agreed on in Kyiv when the three prime ministers of Eastern European countries, as well as Mr. Kaczynski, arrived in our capital. It was in mid-March. Today, immediately after the conversation with the President of Poland, I contacted the defenders of Mariupol. I am in constant contact with them. Their determination, their heroism and resilience are impressive. I am grateful to each of them! I wish at least a percentage of their courage to those who have been thinking for 31 days how to transfer a dozen or two of planes or tanks…

And, by the way, we talked today with our military in Mariupol, with our heroes who defend this city, in Russian.

Because there is no language problem in Ukraine and there never was.

But now you, the Russian occupiers, are creating this problem. You are doing everything to make our people stop speaking Russian themselves. Because the Russian language will be associated with you. Only with you. With these explosions and killings. With your crimes. You are deporting our people. You are bullying our teachers, forcing them to repeat everything after your propagandists. You are taking our mayors and Ukrainian activists hostage. You are placing billboards in the occupied territories with appeals (they appeared today) not to be afraid to speak Russian. Just think about what it means. Where Russian has always been a part of everyday life, like Ukrainian, in the east of our state, and where you are turning peaceful cities into ruins today. Russia itself is doing everything to ensure that de-russification takes place on the territory of our state. You are doing it. In one generation. And forever. This is another manifestation of your suicide policy.

Our representatives - the Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Minister of Defense of Ukraine - met today in Poland with colleagues from the United States. They were joined by US President Joseph Biden. As I was informed, the negotiations concerned, in particular, these vital interests, which I mentioned above. Concerned what we really need while this ping-pong continues - who should give us planes and other protection tools and how. Ukraine cannot shoot down Russian missiles using shotguns, machine guns, which are too much in supplies.

And it is impossible to unblock Mariupol without a sufficient number of tanks, other armored vehicles and, of course, aircraft. All defenders of Ukraine know that. All defenders of Mariupol know that. Thousands of people know that - citizens, civilians who are dying there in the blockade.

The United States knows that. All European politicians know. We told everyone. And this should be known as soon as possible by as many people on earth as possible. So that everyone understands who and why was simply afraid to prevent this tragedy. Afraid to simply make a decision. Vital decision.

Of course, we have already seized a number of Russian tanks, which the military command of this country keeps sending to be burned here.

However, the nations of the world will not understand for sure if the battlefield in Ukraine will be a larger supplier of tanks to protect freedom in Europe than our partners.

Ukraine's position must be heard. I want to emphasize: this is not only our position.

This is the position of the vast majority of Europe's population, the majority of Europeans.

If someone does not believe me, look at current public opinion polls in the world.

And if you do not want to hear the opinion of the people, then hear the strikes of Russian missiles hitting right next to the Polish border. Are you waiting for the roar of Russian tanks?

I also spoke with Prime Minister of Bulgaria Kiril Petkov. In particular, about the humanitarian catastrophe due to the actions of Russian troops and how to save our people.

I spoke today at the Doha Forum in the capital of Qatar. This is a respectable meeting that is important not only for the Islamic world, but also for many other countries in Latin America and Africa. These are the regions where Russian propaganda still has great influence. But we are working against lies all over the world. Let Russia know that the truth will not remain silent. And let every nation in the world feel the depth of Russia's injustice against Ukraine. Against everything that keeps the world within morality and humanity.

The occupiers committed another crime against history. Against historical justice.

Near Kharkiv, Russian troops in their branded inhuman style "denazified" the Holocaust Memorial in Drobytsky Yar.

During World War II, the Nazis executed about 20,000 people there. 80 years later they are killed a second time. And Russia is doing it.

The menorah in Drobytsky Yar destroyed by Russian projectiles today is another question to the entire Jewish community of the world: how many more crimes against our common memory of the Holocaust will be allowed to be committed by Russia on our Ukrainian land?

Russian troops are deliberately killing civilians, destroying residential neighborhoods, targeting shelters and hospitals, schools and universities. Even churches, even Holocaust memorials!

Russian troops receive just such orders: to destroy everything that makes our nation nation, our people - people, our culture - culture. This is exactly how the Nazis tried to capture Europe 80 years ago. This is exactly how the occupiers act in Ukraine. No one will forgive them. There will be responsibility. Just like 77 years ago. Most likely not in Nuremberg. But the meaning will be similar. You will see.

Everyone will see. Everyone. We guarantee.

Glory to all our heroes!

Glory to Ukraine!

Vladimir Putin. (photo: The Hill)

Vladimir Putin. (photo: The Hill)

The speed of Russia’s transformation to Soviet-style “self-purification” has been astonishing. When Russia invaded Ukraine last month, state TV went to wall-to-wall propaganda blaming Ukrainian “neo-Nazis” and “nationalists.” Now, shadowy pro-Putin figures are daubing the words “traitor to the motherland” on the doors of peace activists and others.

A pile of animal excrement was left outside the door of St. Petersburg activist Daria Kheikinen on Friday, and a severed pig’s head and an anti-Semitic slogan was left Thursday at the door of Alexei Venediktov, editor in chief of the now-disbanded liberal radio station Echo of Moscow. The station was forced to close earlier this month by state-owned Gazprom, which controlled its board.

Websites with names have sprung up encouraging Russians to denounce “traitors,” “enemies,” “cowards” and “fugitives” who oppose the war.

One of the first three people charged Russia’s tough wartime censorship law was Marina Novikova, a 63-year-old pensioner with just 170 Telegram followers. A day after the invasion, she fixed her gaze on the camera, a lock of red hair flopped over one eye. “Those who want to think and can think will be able to get out of darkness,” said from the closed Russian nuclear city Seversk (formerly Tomsk-7).

In what she called a “shock psychotherapy” session, she said Russians “all approved the war in Ukraine. This is our silent, total agreement.”

Others have headed from the borders. Actors, celebrities, businessman, singers, dancers, writers. IT workers and independent journalists are among those who have left Russia.

State television staffer Marina Ovsyannikova — the Channel One producer who made global headlines on March 14 when she held up an antiwar poster during a news broadcast — feared she could face up to 15 years jail. But on Friday, she was charged with a misdemeanor offense of discrediting the military. Earlier Kirill Kleimyonov, the station’s head of news, suggested on air that she was a British spy.

“Treason is always someone’s personal choice,” he said, claiming she acted not out of passion but “for 30 pieces of silver.”

But a conversation with Ovsyannikova leaves a different impression. Her words tumble out, one thought after another. She hesitates about saying something that might land her in more trouble, but says it anyway.

“Propaganda in Russia has become ugly. Our country is in a total darkness now. Anyone can be called a national traitor or a ‘fifth columnist’ now for just taking part in a rally,” she said in an interview before the court decision.

For years, she looked away as repressions piled up, taking a good state salary telling herself she was doing it for her family. “But you get to the point of no return when it’s beyond the limit of absolute evil. And a normal person can’t stand it any longer. You just can’t go on.”

“I was so shocked. I could not eat or sleep.” At work “the atmosphere was very depressing and stressful. I saw these breaking news reports all the time. I realized that I could not work there anymore.”

In the end, she burst onto the national state television news with her antiwar poster in an unprecedented act of defiance.

“They’re lying to you here,” the poster said in Russian. And in English: “No war.”

“I don’t have any regrets, I and not recanting any of my words or acts. I am glad that it sounded out loud,” she said.

Despite the risk of fines and jail time, others keep protesting. More than 15,000 people have been arrested since the war started.

Anastasia, wearing a jacket with the words “No to War,” was grabbed by riot police earlier this month as she walked toward a small group of protesters in Moscow. She was arrested and fined.

“It makes me really angry,” said Anastasia, who asked that her surname not be used for security reasons. “On top of anger, I feel a kind of desperation and sadness and regret, specifically a regret that there is nothing good in the future any more.”

Cars carrying imperial flags and bearing the letter Z, a symbol of support for the war have appeared in Russian cities and towns.

“It’s hard to believe that these people are real and that they actually believe that this military operation is a way to save Russia, because none of this is going to bring any good,” she said.

Kirill Martynov, political editor of Novaya Gazeta, was denounced as a traitor and dismissed recently by two universities where he taught two philosophy courses. A parent had heard him tell students that civilians were being killed in Ukraine.

Martynov, who later left Russia, fears the purges are just getting started, amid deepening social tensions over the war.

“Russian authorities and people who support the war need to find someone who is guilty, because when society and the economy is collapsing, you have to find some enemy to take responsibility,” he said.

“There will be a kind of hunt for traitors in the next months and we’ll see a lot of criminal prosecutions, because they need some explanation of what is happening in Russia and, if Russia is so great and Putin is such a wise person, why is life in Russia so bad now,” he added.

But there is a thread of messianic rhetoric from top Russian officials, pro-Kremlin journalists, religious figures and academics, laying out the mission to revive Russian greatness. They revile Western liberalism and applaud conservative, authoritarian orthodoxy.

A prominently featured article on state-owned RIA Novosti news site by conservative commentator Pyotr Akopov bore the headline” “Russia of the future: Forward to the USSR.” He wrote that “the spirit of Russian history, the spirit of our ancestors gives us a chance not just to atone for the collapse of the Soviet Union. It gives us a chance to fix it through creation, through the rebirth of the great Russia.”

Calling for new Russocentric thinking, he argued that Russian intellectuals and oligarchs were mental slaves of the West, who wanted to copy it and reform Russia.

“What does this mean?” tweeted historian Ian Garner, who specializes in the study of Russian propaganda. “In sum: a rooting out of anyone accused of being ‘un-Russian’ in thinking or culture.’”

Olga Irisova, editor in chief of independent media outlet Riddle, said that Putin’s call for Russia’s self-purification marked an ominous turning point, making it dangerous to oppose the war. (Irisova is outside Russia and Riddle website is still operating.)

“Even my acquaintances who are still in Russia, are scared to speak out now,” said Irisova. They’re scared even to talk to people about the war because they believe that other people might report them to the authorities or just might call them traitors.”

Irisova said the marking of “traitors” on activists’ doors reinforced the government’s message. “If you do not agree with us, you are a minority,” she said. “You should stay silent. And people are afraid.” Thousands would emigrate, but most would not be able to leave.

“I don’t see any positive scenario for Russia,” she added. “I see more repressions.”

But one protester, Valetin Belayev, sees a sliver of hope from his home in Kazan, 510 miles east of Moscow. “Now Russia is at a crossroads,” he said. “Either we will sink into the abyss of a hopeless nightmare, or we will be able to avoid this scenario.”

“We’re at a point where history could go in completely different directions,” he continued, “and all of us now have a personal responsibility for what the future of our country and the world will be like.”

A Yemeni soldier inspects a site of Saudi-led airstrikes targeting two houses in Sanaa on Saturday. (photo: Hani Mohammed/AP)

A Yemeni soldier inspects a site of Saudi-led airstrikes targeting two houses in Sanaa on Saturday. (photo: Hani Mohammed/AP)

At least 8 killed as targets struck in rebel-held cities of Sanaa and Hodeida

The overnight airstrikes on Sanaa and Hodeida — both held by the Houthis — came a day after the rebels attacked an oil depot in the Saudi city of Jeddah, their highest-profile assault yet on the kingdom.

Brig.-Gen. Turki al-Malki, a spokesperson for the Saudi-led coalition, said the strikes targeted "sources of threat" to Saudi Arabia, according to the state-run Saudi Press Agency.

He said the coalition intercepted and destroyed two explosives-laden drones early Saturday. He said the drones were launched from Houthi-held civilian oil facilities in Hodeida, urging civilians to stay away from oil facilities in the city.

Footage circulated online showed flames and plumes of smoke over Sanaa and Hodeida. Associated Press journalists in the Yemeni capital heard loud explosions that rattled residential buildings there.

Fuel supply station among targets

The Houthis said the coalition airstrikes hit a power plant, a fuel supply station and the state-run social insurance office in the capital.

A Houthi media office claimed an airstrike hit houses for guards of the social insurance office, killing at least seven people and wounding three others, including women and children.

The office shared images it said showed the aftermath of the airstrike. It showed wreckage in the courtyard of a social insurance office with the shattered windows of a nearby multiple-story building.

In Hodeida, the Houthi media office said the coalition hit oil facilities in violation of a 2018 cease-fire deal that ended months of fighting in Hodeida, which handles about 70% of Yemen's commercial and humanitarian imports. The strikes also hit the nearby Port Salif, also on the Red Sea.

Al-Malki, the coalition spokesperson, was not immediately available for comment on the Houthi claims.

The escalation is likely to complicate efforts by the UN special envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg, to reach a humanitarian truce during the holy month of Ramadan" in early April.

It comes as the Gulf Cooperation Council plans to host the warring sides for talks late this month. The Houthis however have rejected Riyadh — the Saudi capital where the GCC is headquartered — as a venue for talks, which are expected to include an array of Yemeni factions.

The Houthis also announced Saturday a unilateral initiative that included a three-day suspension of cross-border attacks on Saudi Arabia, as well as fighting inside Yemen. They demanded an end to the coalition air and sea blockade on their territories before engaging in negotiations.

Peter Salisbury, Yemen expert at the International Crisis Group, doubted that ongoing efforts will succeed in bringing a peaceful settlement to the grinding war in the near future, given that international attention is now focusing on other crises including the war in Ukraine.

"I really wouldn't buy into any optimism we'll see diplomatic progress in 2022," he said. "It's pretty clear that all parties are still looking for ways to either win outright or cause significant damage to their rivals."

Yemen's brutal war erupted in 2014 after the Houthis seized Sanaa. Months later, Saudi Arabia and its allies launched a devastating air campaign to dislodge the Houthis and restore the internationally recognized government.

The conflict has in recent years become a regional proxy war that has killed more than 150,000 people, including over 14.500 civilians. It also created one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world.

The Houthis' Friday attack came ahead of a Formula One race in the kingdom on Sunday, raising concerns about Saudi Arabia's ability to defend itself against the Iranian-backed rebels.

Jeddah hosting Formula One race

Friday's attack targeted the same fuel depot that the Houthis had attacked in recent days — the North Jeddah Bulk Plant that sits just southeast of the city's international airport and is a crucial hub for Muslim pilgrims heading to Mecca.

In Egypt, hundreds of passengers were stranded at Cairo International Airport after their Jeddah-bound flights were cancelled because of the Houthi attack, according to airport officials.

The kingdom's flagship carrier Saudia announced the cancelation of two flights on its website. The two had 456 passengers booked. A third cancelled flight with 146 passengers was operated by the low-cost Saudi airline Flynas.

Some passengers found seats on other Saudi Arabia-bound flights and others were booked into hotels close to the Cairo airport, according to Egyptian officials who spoke on condition of anonymity because there were not authorized to brief media.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell speaks during a news briefing on March 15, 2022. (photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell speaks during a news briefing on March 15, 2022. (photo: Alex Wong/Getty Images)

The GOP’s hypocrisy on donor transparency has been on full display since President Biden announced Ketanji Brown Jackson as his Supreme Court justice nominee.

On the day President Joe Biden announced Jackson’s nomination, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell declared she “was the favored choice of far-left dark-money groups.” During the first day of Jackson’s confirmation hearings, Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, feigned concern about the “troubling role of far-left dark money groups” in the judicial selection process.

Outside of the hearing room, Judicial Crisis Network — which pioneered dark money spending on judicial nominations — has dropped at least $2.5 million on ads attacking the “dark money” it claims is behind Jackson’s nomination. (These attacks are largely focused on Demand Justice, which formed in 2018 as a liberal counterweight to JCN, but whose spending thus far has been dwarfed by that of JCN.) As The Washington Post’s Fact Checker and others have pointed out, it is certainly ironic for a prominent dark money group to critique dark money.

But the hypocrisy from Republican senators — McConnell in particular — is on another level: They are critiquing a system that they themselves have not only worked to protect, but to construct.

In fact, just last year, McConnell, Grassley and their colleagues had a chance to do something about the dark money flooding judicial nominations. But instead, these Republican senators used their power to keep dark money dark.

In 2021, the House passed the For the People Act, which, among many other things, had robust provisions to shine a spotlight on dark money, including dark money spent on judicial nominations. When the bill reached the Senate, some of its voting rights and ethics protections were jettisoned, but the transparency provisions remained intact.

McConnell, Grassley and every other Republican senator blocked the legislation. If they hadn’t, then dark money groups like Demand Justice on the left and Judicial Crisis Network on the right would have been required to disclose the wealthy donors who had given $10,000 or more. There would’ve been little “dark money” today for these politicians to complain about.

McConnell’s new attack on dark money is particularly cynical. He not only blocked the legislation, but expressly critiqued its anti-dark money measures and proposed an amendment that would’ve stripped out the bill’s transparency provisions, arguing that keeping wealthy donors secret was necessary to protect “associational privacy.” When the House passed the bill, McConnell issued a statement declaring that it “tramples on citizens’ privacy,” echoing a talking point he has used to argue against more donor transparency. (That’s on top of the amicus brief he filed with the Supreme Court last year urging it to strike down California’s charity disclosure laws.)

He made it his personal mission to keep the dark money spigot open. In a recording obtained by The New Yorker, a top McConnell aide told a number of powerful dark money groups that McConnell was “not going to back down” in his opposition to the bill, especially its “donor privacy” provisions.

But the recording revealed another insight, one that may be relevant to the GOP’s latest messaging: Internal polling conducted by one Koch-run advocacy group showed that ending dark money is popular with voters across the political spectrum. “There’s a large, very large, chunk of conservatives who are supportive of these types of efforts,” a representative of the Koch group said on the call, according to The New Yorker.

Given the public’s broad, bipartisan opposition to secret political spending, McConnell and other wealthy special interests have apparently given up on trying to convince voters that dark money actually stands for “donor privacy” and that transparency is really an “attack on speech.”

Instead, they’re going to cynically muddy the waters and attempt to confuse the public about who is spending dark money — and who is working to keep dark money dark.

The public is right to be concerned about dark money. When judicial confirmation battles are dominated by millions of dollars in secret political spending, the public and lawmakers cannot know who is trying to influence them or how the wealthy special interests who are secretly bankrolling these campaigns may stand to benefit from the Supreme Court’s opinions.

As the 2022 midterms approach, we are certain to see millions more in dark money spent by both Democrats and Republicans to influence our votes. When millions of dollars in dark money are spent on elections, voters cannot know what secret donors might be getting in return from the politicians they are backing.

Candidates of all political stripes are critiquing the role of dark money in politics, but voters should demand more than just talk. Politicians who rail against dark money while refusing to support legislation to clean it up are part of the problem.

Catherine Nash, Jesse Harvey's mother, poses for a portrait at a pond in her backyard in Holden, Mass., on March 17, 2022. (photo: Kayana Szymczak/The Intercept)

Catherine Nash, Jesse Harvey's mother, poses for a portrait at a pond in her backyard in Holden, Mass., on March 17, 2022. (photo: Kayana Szymczak/The Intercept)

Lying in a hospital bed in late 2019, he told his mother, Catherine Nash, that another stretch in a rehab center wouldn’t do the job. At just 27, he had already experienced the disillusioning cycle in and out of inadequate treatment facilities and hospitals that is familiar to the millions of Americans with substance use disorders. “Those places never work,” Catherine recalls him saying. He knew well that many patients quickly relapse after leaving standard treatment centers.

He told Catherine he wanted to enter civil commitment, a court-ordered form of institutionalization. Once Jesse agreed to be committed, he would be relinquishing his right to leave before a specified date. Catherine was relieved at his decision, desperate for anything to help her son, even if it meant he would be locked up. After a night in a motel and a pizza dinner, they drove a rental car through the snow to a courthouse in central Massachusetts.

Throughout the United States, people with diagnosed mental illnesses have long been voluntarily and involuntarily committed to treatment centers and hospitals. More recently, civil commitment has been used to treat people with addictions. Yet experts say that even if commitment can prevent self-harm in the short term, it rarely addresses the root causes of substance misuse — and its long-term consequences can be devastating. “Seclusion and restraint continue to be used in inpatient commitment settings, and the experience can be highly traumatic for some patients,” according to a 2019 report exploring the practice by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a federal agency.

There is little to no evidence demonstrating the long-term effectiveness of civil commitment for substance use disorder. Still, courts have repeatedly classified this form of incarceration as constitutional, seeing it as necessary for the safety of both the public and the individuals locked up.

Even when civil commitment is effective, it deprives people of basic civil liberties. “There is no real evidence that I’ve heard that convinces me that it’s reasonable to take away somebody’s freedom over their own body when they have not been convicted of a crime,” said Susan Sered, a sociologist at Suffolk University who has for years studied civil commitment for women and fears the rise of commitment for drug use. “The wholesale use of voluntary commitment is really going to be problematic. There is a reason that we have a legal system with the idea of due process.”

Overwhelmed with opioid overdoses, many states have loosened their civil commitment laws over the last decade to sweep in more people with substance use disorders. A yearlong investigation by The Intercept and Type Investigations — including dozens of data requests, examinations of obscure government records and databases, and interviews with numerous experts and patients — shows that in recent years, tens of thousands of people across the country at minimum have been forced to undergo addiction treatment in jail-like conditions. While some of them benefit from civil commitment, others find the treatment to be nonexistent or downright harmful — and all lose their freedoms while they are locked up. The facilities holding them are sometimes housed on the grounds of jail complexes, providing incarceration by another name.

Jesse had tried civil commitment years earlier, doing a 25-day stint at the Massachusetts Alcohol and Substance Abuse Center. Despite its harshness, he had found the intense structure helpful and wanted to try it again. Starting at a young age, he had spent years tackling the challenges of addiction — both for himself and for others. At 24, he founded a nonprofit that ran recovery houses, and at 26, he started the “Church of Safe Injection” to offer supplies like unlimited free clean needles to those in need.

By 2019, Jesse had become well-acquainted with the mountains of research showing that criminalizing drug use worsens the plight of users. He knew that successful treatment requires a combination of medication and therapy. He understood that he would be entering a locked facility when he put his fate in the court’s hands, but he anticipated a therapeutic environment as well. On December 31, Catherine and Jesse entered Leominster District Court, where she signed a form to commit him. The thin young man with clean-cut hair was still wearing his hospital scrubs when a forensic psychologist from the state’s Department of Mental Health assessed him. (The department’s slogan: “Good Mental Health. It starts with a conversation.”) Jesse’s breath smelled of the booze he’d had that very morning, but the psychologist found him to be articulate and intelligent. She agreed that he met the state’s criteria for commitment — he’d lost his ability to control his use of alcohol and drugs, and he posed an imminent threat to himself or others — and a judge signed off.

Massachusetts has one of the highest rate of deaths from opioid overdoses of any state. It also has among the most commitments in the country, and the state Department of Correction runs the largest program. Jesse joined the thousands of people committed in the state in 2019. For the first time in a while, he was optimistic about his chances at transcending his disorder. He asked to go to the Stonybrook Stabilization and Treatment Center in Ludlow, where he knew he would be held until he was sober. “He just needed to be in a place where he couldn’t leave,” Catherine recalled. At the time, the average stay at Stonybrook lasted 52 days, much longer than at other facilities in the state. Yet based on his previous experience in commitment and the advice of a public defender, whose name does not appear in Jesse’s treatment records, Jesse believed he would be locked in the treatment center for about three weeks, which had been the statewide average length of commitment a couple years prior. After that, he hoped, he could return to school, healthy and with renewed spirits. It didn’t work out that way.

In the modern era, civil commitment laws are primarily used to treat individuals with severe mental illnesses, but states are increasingly applying the laws to other populations. Individuals can be committed while being evaluated for competency before they stand trial, for example. Other people are held in commitment indefinitely, sometimes for decades, after completing criminal sentences, a practice opposed by the American Psychiatric Association.

Individuals who use drugs inevitably were added to this population. As part of the panic over cocaine and crack, especially among pregnant Black women, in 1989, the first Bush administration recommended that states make it easier to civilly commit drug users. (At the time, only a handful of states had civil commitment programs for people with substance use disorders who hadn’t been convicted of a crime, and the laws were rarely used.) In 1997, the Supreme Court expanded the conditions under which people could be civilly committed, ruling that it was legal to commit anyone who had a “mental abnormality,” whereas the previous standard had been narrower, requiring “mental illness.” Writing in the California Law Review in 2002, a law professor predicted that the ruling would expand civil commitment for substance abuse, despite its violation of fundamental due process rights.

That’s exactly what happened. As of May 2021, 37 states and the District of Columbia permit civil commitment for substance or alcohol misuse, with additional states considering joining the ranks, according to data from Temple University’s Center for Public Health Law Research. Between 2015 and 2018 alone, there were 25 new laws — or expansions of existing laws — in this area. That was more than triple the number of new or expanded laws passed in the 13 prior years combined.

While some states’ laws are less restrictive than others, many of them lead to warehousing people with substance misuse problems in jail-like facilities that can, in some cases, exacerbate rather than address their illness. “There is an increasing recognition that incarceration may not be the appropriate response to addiction, but at the same time, the rapid growth of civil commitment laws and programs is an indicator that we’re not moving away from negative, coercive programs — we’re just rebranding them,” said Leo Beletsky, a public health expert at Northeastern University School of Law.

Many states lack data on how many individuals are committed exclusively or primarily for substance misuse, instead folding the numbers into the total number of people committed for all mental health issues. In Texas, that number is astronomical: There were more than 240,000 applications for commitment between fiscal years 2016 and 2020. Of cases that reached a final hearing, about 60 percent were ordered to inpatient commitment, with the numbers of annual commitments tripling from 2004 to 2020. Wisconsin, also high on the list of states that commit people, had about 17,200 cases between 2016 and 2020.

Massachusetts leads the country in confirmed substance abuse commitments, with nearly 30,000 adult cases of commitment between FY 2016 and FY 2021. Minnesota issued more than 5,200 judgments between 2016 and 2021 ordering that people be committed. In Kentucky, there were almost 3,000 cases of people being committed between 2016 and 2021, while Washington committed about 300 people for opioid use disorder between April 1, 2018, when the state’s commitment law went into effect, and December 31, 2021.

Florida’s commitment law for alcohol and substance use disorder was used nearly 45,000 times between January 2016 and June 2020. But it’s impossible to know how many of those cases actually led to commitment, because the state doesn’t track that number. “This should not be particularly difficult to investigate or to see,” said Ameet Sarpatwari, an expert on bioethics at Harvard Medical School. “The stats haven’t really been collated in a systemic way across the states, and states aren’t necessarily collecting that information and making it transparent.”

In some states, civil commitment laws are on the books but rarely invoked for substance abuse. In Michigan, an average of one person a year is committed for it. But that isn’t because policymakers don’t wish to lock people up; 80 percent of judges in one survey said they had seen individuals who would benefit from commitment for substance abuse. However, when someone signs a petition for civil commitment in the state, they must agree to cover the costs of examining their loved one by a health professional, pay for the court hearing, and the commitment itself. That discourages people from utilizing the program.

The lack of comprehensive national figures on civil commitment for substance use disorder illustrates what Nathaniel Morris, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, has called “detention without data.” He says it applies to civil commitment generally, not just as the practice is used for substance misuse. “Even within states, civil commitment may be practiced differently between different counties,” he wrote in an email. “We have a fragmented mental health system in the United States, where different hospitals, emergency departments, clinics, and courts often do not readily share information or communicate with one another.”

Nearly all states mandate that individuals receive a clinical assessment before they are committed. However, in one recent survey published in the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 19 out of 33 court clinicians surveyed in Massachusetts who evaluated people for substance use disorders said they had at least once recommended that an individual be committed even when they didn’t meet the statutory criteria for it — that is, they went beyond what the law allows. And only four states bind the court’s decision to the assessment.

These kinds of arbitrary standards and lack of oversight alarm doctors, activists, and experts, many of whom are fighting the expansion of laws that would allow more involuntary commitment. Some believe civil commitment for opioid users should be abolished altogether, while others believe it needs profound reform.

Jesse Harvey was just glad to be going somewhere he could get the help he needed. That was the plan anyway.

The Hampden County Sheriff’s Department depicts Stonybrook as an ideal treatment center, promising “evidence-guided, trauma-informed, and family-focused detox and post-detox care.” It describes a therapeutic, nonpunitive environment. “The men civilly committed to [Stonybrook] are referred to as clients,” it says. They are issued T-shirts, khaki pants, and sweatshirts to wear and don’t share space with people who face criminal charges: “Civil commitments are housed separately, their intakes occur separately, and have all recreation separately.”

But Jesse soon discovered a very different reality. Like other individuals committed in Massachusetts, he was immediately slapped with handcuffs and shackles for transport to the treatment center, though he had volunteered to enter commitment and hadn’t been charged with a crime.

While there were dedicated therapists on staff, Jesse was also surrounded by jail guards, a policy that Rob Rizzuto, a spokesperson for sheriff’s department, said has since changed. “All staff working at the Stonybrook Stabilization & Treatment Center are specially trained residential treatment staff,” he wrote in an email. Yet he acknowledged that some of the people classified as residential treatment staff are former correctional officers. The building itself is on the grounds of the Hampden County Correctional Center, a forbidding seven-building complex that holds 900 medium-security prisoners and is surrounded by barbed wire. In a 500-page diary he kept during his stay, Jesse described the humiliation of being locked in a jail-like facility run by a sheriff. “This is the best way to reinforce criminality and to hopelessly institutionalize the already downtrodden,” he wrote.

Guards routinely called the men “inmates,” he wrote in his diary, flouting the official policy, and the language of incarceration also appeared in his treatment records. In Jesse’s “offender assessment” documents, his caseworker referred to him as an “offender” who “is in jail” and in “incarceration.” He was given a wristband with an ID number and barcode. His cell was a shared room with a stainless steel seatless toilet and an open door that allowed the guards to monitor him at all times. (Rizzuto said that “the program has since moved to another facility which has communal bathrooms with modifications made to enhance privacy.”) Jesse was given shirts with slogans like “Change is Possible” and “Recovery Works.”

Stonybrook’s rules added to Jesse’s sense that he was being locked up for having an illness. “It’s dehumanizing and unnecessary,” he wrote. “Put us in a hospital or a treatment center, not a jail.” The jail could arrange for family visits by special appointment only, and staff monitored detainees’ phone calls, which they could only use to call pre-approved individuals. After granting them five free five-minute calls upon entering the facility, Stonybrook charged the usual exploitative call fees common to prisons and jails in the U.S. (the policy at Stonybrook has since been changed to permit 15 free 10-minute calls per week). The jail only accepted letters sent to residents that were written on white paper in black ink and sent in white envelopes. Although they received snack bags, there was no commissary should detainees want to purchase extra food, beverages, or hygienic items (in an April 2019 presentation, the sheriff’s department said this was meant “to prevent the clients from placing undue pressure on family members for money,” claiming that many of them “have been a financial drain on family resources.”)

In response to emailed questions, Rizzuto praised the program. “We are extremely proud of this program as it has saved countless lives as the addiction treatment system offers too few options, and insurance is a barrier to many getting the comprehensive help they need and deserve.” He added that, since Jesse’s time at Stonybrook, there is a new recreation area with open outdoor spaces, a large lawn, basketball courts, a track, and a wooded area. Stonybrook now has a full-time therapy dog, Rizzuto said, as well as more mindfulness classes, including a guided drum circle.

But Jesse wasn’t the only person who experienced commitment in Massachusetts as dehumanizing. A 2019 lawsuit filed by Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts, or PLSMA, against several state agencies alleges that people committed in the state were put in shackles and waist chains, subjected to strip searches, and even put in solitary confinement — all outside the criminal justice system. In 2021, the organization filed an amended complaint, adding four men held in Stonybrook. The suit is still pending.

“The feedback we receive from patients and their families is not at all consistent with the allegations made in the lawsuit,” said Rizzuto, who denied that the department conducts strip searches or uses solitary confinement. “We often hear from clients and their families that our program saved their lives.”

Spokespeople for the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Department of Correction, and the Executive Office of Public Safety and Security all declined to comment, citing pending litigation. The Department of Health and Human Services did not respond to requests for comment. But the agencies mentioned by PLSMA jointly filed a court motion in February 2022 seeking dismissal of the suit, noting that the state is requesting $36 million to overhaul one of the civil commitment facilities. The motion said the state “is involved in major, ongoing projects to improve” the program.

Despite his shock and disappointment at his treatment, Jesse was determined to make the most of his experience. “There’s some pain in my life that I haven’t addressed yet, that I should, that I must, if I hope to recover,” he wrote. He was eager to receive counseling and explore research-backed treatments. He meditated often, read a mystery novel, found himself enjoying the news and classical music on NPR, and he watched NBC’s “Meet the Press” and several Keanu Reeves movies in the common space.

Some fellow detainees recognized him from his activism and approached him, he wrote in his diary, and numerous others who had read or heard about his work sent him letters. “He was a visible and beloved figure in harm reduction communities,” said Northeastern University’s Beletsky. After working at a treatment center in Maine, Jesse had founded his nonprofit, Journey House, which operates four homes for people in recovery, addressing the need for affordable housing for people taking medications to combat substance abuse issues. Rehab, halfway houses, and treatment centers in the U.S. are traditionally abstinence-only, prohibiting or ejecting anybody who uses drugs like methadone that are proven to help alleviate withdrawal symptoms and psychological cravings. But Jesse knew about the growing body of research that suggests that such strict puritanical mandates are deeply harmful to recovery, and his recovery houses reflected that knowledge.

That’s also what inspired him to found the Church of Safe Injection. In Maine, where it was illegal to independently distribute clean needles despite overwhelming evidence that it saves the lives of intravenous drug users, Jesse handed out thousands of them in areas where addiction was rampant. The Church spread to other states and had multiple chapters. Soon Jesse was profiled in HuffPost, STAT, various Maine publications, and a short documentary film.

Helping other residents was a source of strength for him while at Stonybrook. He encouraged his cellmate to take advantage of after-incarceration support systems and talked with another about opening a sober house together. “I have a feeling I am here for a reason, not only in this facility but on this planet and in this multiverse,” he wrote in his diary.

But Jesse’s extensive knowledge of treatment options made his experience all the more disappointing — and then infuriating. Most of the treatment at Stonybrook came in the form of group meetings, which he was pushed to attend, even if they were unhelpful. “Another group providing little if any therapeutic value,” Jesse wrote after one meeting. “It’s a demeaning place, not a therapeutic one.”

His impressions were echoed in the PLSMA lawsuit, in which one prisoner alleged that he was forced to withdraw from opioids cold turkey, and another claimed that none of the treatment sessions tackled the mental health problems underlying substance misuse. Rizzuto did not address the lawsuit claims directly but said, “All clients are seen by medical staff upon admission for a physical evaluation to include medically managed withdrawal specific to each client’s needs.” Stonybrook provides medication to help people detoxing, Rizutto noted, in the form of Suboxone, Librium, Vistaril, and clonidine.

In his diaries, Jesse noted that some detainees were benefiting from the treatment offered, and he said being away from dangerous substances was initially helpful. Still, he wrote, “I wonder why such rehabilitation, court-ordered, can’t happen exclusively in hospital settings, locked even, and why can’t it happen in line with compassion and evidence-based principles instead?”

Jesse soon found that whatever benefits he derived from civil commitment were diminishing. He was horrified to learn that he would not be leaving after three weeks. Instead, he was told he would be released at an unknown date entirely at the discretion of the facilities’ officials. (Treatment records show that Jesse’s commitment was meant to expire on March 27, nearly three months after his commitment.) “Part of me is starting to wonder if I’ll get even more jaded, or depressed even, if they don’t let me leave soon,” he wrote. But getting out would prove far more difficult than he could have imagined.

As the opioid crisis escalated, it was easy for policymakers to opt for civil commitment as a remedy. For one thing, after decades of mass incarceration, jails and detention centers are more plentiful and better funded than outpatient services that treat drug addiction and dependency. Locking people up is also a simpler policy option than dealing with the structural factors that lead to drug and alcohol misuse, such as poverty. Civil commitment also doesn’t infringe upon the rights or privileges of the general public, and politicians can boast that they are taking action as part of the drug war.

“There has long been this idea that if you criminalize homelessness, and if you criminalize mental health conditions, then you don’t have to actually deal with it,” said John Raphling, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch, which last year opposed a proposed civil commitment bill in Yolo County, California. “It’s easier for a given community to say, ‘Well, just lock those people up on the street.’” In one county in Florida, 1,000 people are committed per year — but there are only 20 beds for long-term treatment. The rest are sent to jails.

Depending on the state, mental health providers, court officials, or law enforcement can apply for commitment. Many states also allow any member of the public to file a petition for commitment. Between punitive laws criminalizing drug use and the lack of affordable treatment options, civil commitment may seem like a reasonable last resort for familie watching loved ones succumb to addiction. “Given the realities of fiscally constrained public mental health systems in an era of managed care and a shrinking safety net, commitment is being used to leverage scarce resources for treatment and other services,” as the 2019 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration report put it. Black people are especially unlikely to receive treatment for opioid use disorder, one reason African Americans are overrepresented in civil commitment.

Effective treatment elsewhere is rare; a survey of 613 for-profit and nonprofit treatment programs published in 2020 in the medical journal JAMA found that not even one-third offered opioid agonist therapy, which research has shown is effective at reducing the risk of overdose and relapse. Well-resourced hospitals and mental health clinics are even scarcer, making civil commitment a more attractive option.

But there is skepticism in the medical community — and sometimes outright hostility — about the use of involuntary treatment for opioid users. In a survey of 739 American Psychiatric Association members published in a 2007 issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, just 12 percent supported committing people for drug use. Still, the approach has its supporters. A 2021 paper in the Journal of Addiction Medicine found that 60.7 percent of addiction specialists favored the practice, although more than one-third of those surveyed said they were unfamiliar with how the laws even worked.

There is good reason for clinicians’ and researchers’ ambivalence. “There is limited quality, peer-reviewed research on the efficacy of involuntary treatment for alcohol and substance use disorders,” according to a 2019 report by a commission appointed by Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker. Proponents of the practice sometimes suggest that, if nothing else, civil commitment provides a short-term way to keep people from overdosing. But a full one-third of civil commitment users relapse the same day they are released, according to a study in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence. The evidence also suggests that forcibly detaining people for opioid misuse doesn’t work in the long term. A paper on civil commitment in a 2021 issue of the Journal of Medical Ethics found “emerging evidence suggests that it may be associated with long-term harms, including a heightened risk of severe withdrawal, relapse and opioid-involved mortality.”

“Involuntary civil commitment is the opposite of treatment,” said Michael Sinha, an adjunct professor at Loyola University’s Beazley Institute for Health Law and Policy, in an email. “In a therapeutic relationship, patients have autonomy and must provide informed consent prior to commencing any treatment or procedure. In a coercive setting such as involuntary civil commitment, patients have no autonomy to affirmatively choose treatment.”

The criminalization of commitment compounds its essential illiberalism. Bonnie Tenneriello, an attorney with Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts who worked on the lawsuit, sees a clear violation of due process. “You can’t hold men in prison just because they have an addiction,” she said. “It’s disability discrimination, it reflects decades of misconceptions about addiction, it creates stigma.”

Jesse Harvey experienced the criminalization of drug addiction firsthand, and he wanted out. Besides his frustration with the treatment, Jesse had other reasons to get back home. He needed to return to his final semester of graduate school or else risk losing his health insurance, access to his counselor and psychiatrist, a $2,000 academic scholarship, and a salary working part-time on campus. “I can get these things back if they let me out,” he wrote. But it’s difficult to revoke a civil commitment in Massachusetts. Stonybrook officials were unmoved by his appeals, with his caseworker writing in his notes, “Jesse seems more focused on leaving our program than committing to treatment.” Another recorded, “I tried to point out to Jesse that he needs to focus on his treatment and recovery and [he] seemed to feel that he is not receiving any treatment here at Stonybrook.”

Jesse’s diary entries grew increasingly despondent. “It is tremendously disempowering, coming to a facility that we’re supposed to get better at, regain our self-esteem, etc., and then be talked down to, lied to, misdirected, etc., constantly having our autonomy and our hopes and dreams torn down without any thorough evaluation of their merit by staff,” he wrote.

He started gathering signatures from other detainees to protest conditions, suggesting they form a class-action lawsuit. “When I’m stuck in a mindless bureaucracy that pledges itself more to red tape than results, I like to fight,” he explained. His efforts did not endear him to authorities. He wrote in his diary that the guards stopped giving him paper, envelopes, and pens, though the sheriff’s department denies this.

At his three-week mark, Jesse was transferred to the Western Massachusetts Recovery and Wellness Center, another facility run by the Hampden County Sheriff’s Department. There, at least the toilets had seats. But again, according to Jesse’s diary, he didn’t find the available treatment to be helpful. “A lethal shame,” he called it.

He wanted to attend different meetings, return to seeing his therapist, get regular exercise, and volunteer or get a job somewhere. He felt that he had a better support system on the outside, with his family, friends, and graduate studies. He made a bucket list of life experiences he wanted to try, everything from bungee jumping to hosting an art show to running a restaurant. He also pledged that, once he was released, he would work to improve conditions for other people in civil commitment.

The Massachusetts statute governing civil commitments authorizes superintendents to release individuals at any time if it does not result in “serious harm” to the community. Yet the office of Superintendent Pamela MacEachern denied his request to leave. (MacEachern has since retired and the spokesperson for the Department of Correction, Jason Dobson, said privacy laws prevented him from commenting on “any part of an inmate’s incarceration.”) Harvey wrote a letter to the sheriff, Nicholas Cocchi, saying, “I’d like to talk to you about concerning violations of civil rights” as a result of his release request being denied. Cocchi responded that he had reviewed Jesse’s case, offered to speak with him, and wrote, “I recommend you continue to work toward your discharge plan.”

Jesse began a hunger strike, refusing all food and beverages besides water and coffee. Still, authorities refused to release him, transferring him back to Stonybrook in handcuffs. He sat in his cell reading and meditating. When nurses checked on him, he declined medical treatment. Other prisoners, including his cellmate, ridiculed him for starving himself, he wrote in his diary, but he was adamant.

Finally, after 124 hours, Jesse wrote, he was given an ultimatum: He had to immediately consume a meal-replacement drink or be put on “risk status,” meaning he would be placed in an anti-suicide smock, and put on continuous 1:1 observation if he refused to wear the smock. However, if he ate, staff promised to review his case status again in a few days. He was convinced the superintendent would let him die rather than release him. He drank the beverage and was put into a wheelchair.

Jesse attended the necessary meetings and outwardly welcomed the treatment he felt was useless. “I can’t believe how powerless I am here,” he wrote. “They have sufficiently beaten me down into dirt. All I feel is worthless. All I see is metal bars. All I hear is lies and dogma and broken promises.”

Stonybrook authorities saw Jesse’s eventual compliance as evidence of progress. He was released on February 6 and given a “certificate of participation,” five weeks after he was first committed and one week after his hunger strike ended. He described feeling battered by the experience. The day before he left Stonybrook, Jesse confessed in his diary, “I feel like I’ll be out and still not feel like it’s real, still feel like a person who is unworthy of civil rights, let alone ethical treatment and common courtesy.”

Kari Morisette met Jesse at the first recovery meeting he attended post-release. Morisette told the group that she felt purposeless, living paycheck to paycheck and working at a donut shop. Jesse approached her after and invited her to help him hand out clean needles to drug users. “He had that type of personality who drew people in, so I didn’t know him, but I knew that I wanted to know him,” she recalled, in between running deliveries for the Church of Safe Injection. She is now the Church’s executive director.

The two became fast friends, and he schooled her in the ways of harm reduction. “It was just me and him,” she said. Jesse remained sober for a while but soon began drinking again. He was discouraged and angry at what he had endured, and he grew more isolated. He was more convinced than ever that the punitive response to substance misuse was both ineffective and caused immense suffering. On September 7, 2020, about seven months after leaving Stonybrook, Jesse died of a drug overdose in his home.

Experts say that Jesse’s experience is common. At worst, civil commitment can cause trauma among people suffering from substance use disorders, who are further discouraged about the health care system. Harvard’s Ameet Sarpatwari, who has written about civil commitment of opioid users for The BMJ, a medical journal, said that treatment in such institutions is often lacking. “It would be one thing if you brought them into care and provided them with the gold standard of care. And then ensured that once they were released from somewhere, that they had integrated and continuous care,” he said. “But that’s not what we’re seeing.”

Catherine, Jesse’s mother, is furious at the civil commitment authorities in Massachusetts. “Jesse died a preventable death,” she said in an email. “Being forced to wait so much longer than he needed to in that diabolical cell week after week took away the things he had to live for.”

But in Massachusetts and nationally, authorities are keeping faith in civil commitment. The Colorado legislature is considering expanding its program. The Washington state legislature recently passed a bill allowing law enforcement and social service workers to petition to require people to undergo outpatient treatment for substance use disorder. This would further criminalize drug use and ensnare even more people in the criminal justice system.

If Jesse had lived, he might have fought against such programs. In his diary, which his mother shared with me, Jesse asked, “How can any sane society or government sanction the jailing of any person who has not committed a crime, but rather has what they — and society and the state — have said is a disease?” He also pointed out the irony of commitment as care. “The power differential that is inherent in a situation like this is glaring and dangerous,” he wrote. “They are taking away the supports they say you need.”

Iconic rock band Pink Floyd, circa 1979. (photo: Capitol Records)

Iconic rock band Pink Floyd, circa 1979. (photo: Capitol Records)

Lyrics Pink Floyd, Another Brick in the Wall

Written by, Roger Waters

From the 1979 album, The Wall.

Daddy's flown across the ocean

Leaving just a memory

Snapshot in the family album

Daddy what else did you leave for me?

Daddy, what'd'ja leave behind for me?!?

All in all it was just a brick in the wall.

All in all it was all just bricks in the wall.

"You! Yes, you! Stand still laddy!"

When we grew up and went to school

There were certain teachers who would

Hurt the children any way they could

By pouring their derision

Upon anything we did

And exposing every weakness

However carefully hidden by the kids

But out in the middle of nowhere

When they got home at night, their fat and

Psycopathic wives would thrash them

Within inches of their lives

We don't need no education

We dont need no thought control

No dark sarcasm in the classroom

Teachers leave them kids alone

Hey! Teachers! Leave them kids alone!

All in all it's just another brick in the wall.

All in all you're just another brick in the wall.

We don't need no education

We dont need no thought control

No dark sarcasm in the classroom

Teachers leave them kids alone

Hey! Teachers! Leave us kids alone!

All in all it's just another brick in the wall.

All in all you're just another brick in the wall.

"Wrong, Do it again!"

"If you don't eat yer meat, you can't have any pudding. How can you

have any pudding if you don't eat yer meat?"

"You! Yes, you behind the bikesheds, stand still laddy!"

[Sound of many TV's coming on, all on different channels]

"The Bulls are already out there"

Pink: "Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaarrrrrgh!"

"This Roman Meal bakery thought you'd like to know."

I don't need no arms around me

And I dont need no drugs to calm me.

I have seen the writing on the wall.

Don't think I need anything at all.

No! Don't think I'll need anything at all.

All in all it was all just bricks in the wall.

All in all you were all just bricks in the wall.

Goodbye, cruel world

I'm leaving you today

Goodbye, goodbye, goodbye

Goodbye, all you people

There's nothing you can say

To make me change my mind

Goodbye

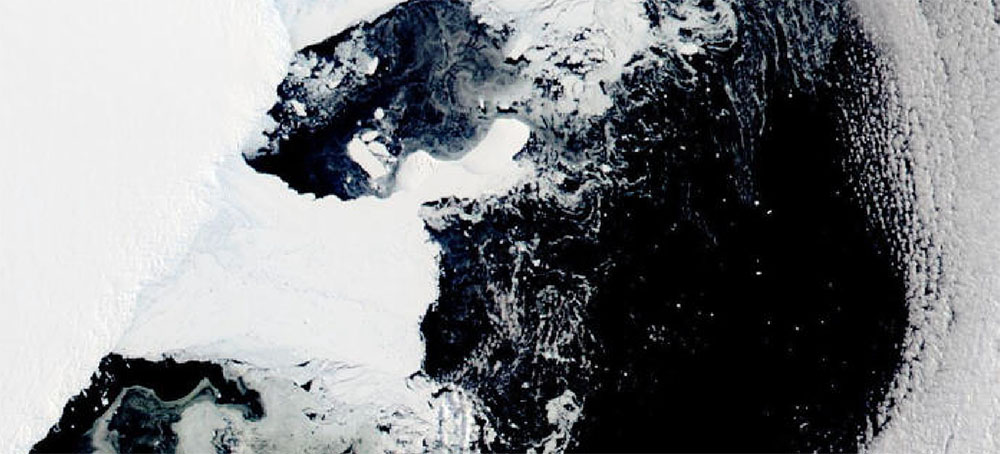

Scientists are concerned because an ice shelf the size of New York City collapsed in East Antarctica, an area that had long been thought to be stable. (photo: NASA/AP)

Scientists are concerned because an ice shelf the size of New York City collapsed in East Antarctica, an area that had long been thought to be stable. (photo: NASA/AP)

The collapse of the 463-square-mile Glenzer Conger ice shelf, which occurred last week, came as temperatures rose in the eastern section of Antarctica by as much as 70 degrees Fahrenheit above normal. That was enough in some places for rain, rather than snow, to fall, the Associated Press reported.

NASA satellites first detected the collapse of the ice shelf.

The extreme heat and the collapse of the ice sheet, which helped keep the Conger and Glenzer glaciers from hitting warming water, is causing alarm among scientists who had considered the area to be stable — unlike other regions, where fears of the collapse of glaciers could lead to massive sea level rise worldwide.

“The Glenzer-Conger ice shelf presumably had been there for thousands of years, and it’s not ever going to be there again,” University of Minnesota ice scientist Peter Neff told the AP.

Ice shelves, which extend over water, help keep ice further inland from flowing into the ocean. As human beings continue to pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, global air and water temperatures continue to rise. "Upper ocean temperatures to the west of the Antarctic Peninsula have increased over 1°C since 1955," according to the British Antarctic Survey. "It has now been established that the Antarctic Circumpolar Current is warming more rapidly than the global ocean as a whole."

While most scientists have been focused on the western section of Antarctica, where the Thwaites Glacier, which is the size of Florida, is in danger of collapse, the revelation that ice in the eastern section of the continent is also at risk of collapse due to climate change is worrisome.

The eastern portion of Antarctica contains more than five times the ice that is found in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, the AP reported. If all of the ice in the east was to melt, scientists say, sea levels would rise by more than 160 feet.

The good news is that it would likely take centuries at the current rate of warming for eastern Antarctica to lose all of its ice. The bad news, however, is that melting there is adding to a problem that scientists believe has already locked in several feet of sea level rise. What remains unknown, however, is how much seas will rise because of melting polar ice caps over the coming decades.

“Think of it this way: If I dumped a truckload of ice in the middle of Phoenix, we’d all know it’s going to melt. But it takes time to melt," Benjamin Strauss, the president and CEO of Climate Central, a nonprofit that tries to educate policymakers and the public about the threats posed by climate change, told Yahoo News. "And the same thing is true for the big ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica and glaciers around the world. We turned up the thermostat. We’ve already heated the planet by a couple degrees, but they’ve only begun to respond by melting. And that’s why we have all this extra sea level in the pipeline.

"It’s hard to imagine the long-term future of South Florida, let’s say," he added, "with the sea level that’s already in the pipeline.”

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.