Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

ALSO SEE: Mariupol Residents Are

Being Forced to Go to Russia, City Council Says

ALSO SEE: Thousands of Mariupol Residents

Forcibly Taken to Russia, City Council Says

Source: Mariupol City Council, with a comment from Mayor Vadym Boychenko

Quote: "What the occupiers are doing today is familiar to the older generation, who saw the horrific events of World War II, when the Nazis forcibly captured people. It is hard to imagine people being forcibly deported in the 21st century.

Not only are Russian troops destroying our peaceful Mariupol, but they have also gone even further and started deporting Mariupol residents. All Russian war crimes must be severely punished."

Details: Russian occupying forces took residents of the Left Bank district, as well as citizens who were hiding in a shelter under the building of a sports club. Mostly women and children were in the shelter.

These are areas where active fighting had taken place. Units of the Armed Forces of Ukraine withdrew from the sports club and residential buildings in order not to attract fire from the Russian occupying forces to these areas of concentrated population. According to the Mariupol City Council, Russian troops took advantage of this and captured the residents.

They were forcibly deported to Russia but were first placed in filtration camps. After checking documents and mobile phones, some were sent to remote regions of the Russian Federation. In another part of Mariupol, the fate of residents is unknown.

Background:

- Journalists showed eerie satellite images and drone videos capturing Mariupol's residential neighbourhoods and shopping malls after the devastating air and artillery shelling by Russian forces.

- According to the Azov Battalion, Russians are putting white bandages on Mariupol residents, telling them that they are doing it for their safety. However, Russian troops are also identified by these bandages – Ukrainian fighters become confused and are not able to distinguish between the occupiers and the civilian population.

- The Mariupol City Council has stated that the Russians drop 50 to 100 bombs on the city every day. 80-90% of the city's buildings have been destroyed as a result, and cannot be repaired.

- In a night address on 19 March, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that 130 people had been rescued from the rubble of the drama theatre in the centre of Mariupol.

- In the afternoon of 16 March, Russian aircraft dropped a heavy bomb on the drama theatre in the centre of Mariupol. The building housed about a thousand city residents who lost their homes due to Russian shelling. Russia's Defence Ministry, Sergei Shoigu, has denied that its planes were involved in the bombing and has claimed that the explosion was a provocation staged by the Azov Battlalion.

Riot officers are deployed in the streets during a protest against the Ukraine invasion in Saint Petersburg, Russia. (photo: AFP/Getty Images)

Riot officers are deployed in the streets during a protest against the Ukraine invasion in Saint Petersburg, Russia. (photo: AFP/Getty Images)

- Four private jets went to Dubai from Russia on Thursday.

- It is not clear why those jets left, but many wealthy Russians are making efforts to leave.

- This week Putin pledged a "self-cleansing" of Russian society, seemingly targeted at the rich.

Danish analyst Oliver Alexander observed the four jets leaving Moscow for Dubai on Thursday morning using flight tracking service FlightRadar24. He described it as an "exodus."

Insider verified the routes the four jets took via flight-tracking websites.

It is not clear who was on board the planes or what reason they had for heading to Dubai, which, unlike Western destinations, has not banned Russian air traffic.

Private jets were also seen going from Russia to Israel earlier this month as Western sanctions on Russian oligarchs began to bite.

Thousands of people have tried to flee Russia since it started its invasion of Ukraine on February 24, Insider previously reported, fearing what life there would be like as it is increasingly isolated from the rest of the world.

Some Russians who left told Insider's Sophia Ankel that they left because they were afraid of detention and other crackdowns in the country, and were also afraid of Russia's economic situations after so many countries implemented sanctions over the invasion.

Putin said in a speech on Wednesday that Russia has to undergo a "self-cleansing of society" following its invasion of Ukraine.

He said: "The collective West is attempting to splinter our society, speculating on military losses, on socioeconomic effects of sanctions, in order to provoke a people's rebellion in Russia."

He appeared to threaten people who were not supportive of the government: "But any people, the Russian people, especially, are able to distinguish true patriots from bastards and traitors and will spit them out."

"I am certain that this necessary and natural self-cleansing of society will only strengthen our country, our solidarity, togetherness, and our readiness to answer any calls to action," he continued.

In the speech, Putin appeared to have wealthy, pro-Western Russians in mind, highlighting those with properties in France or the US who are used to eating oysters and foie gras.

Kenosha. (photo: Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Kenosha. (photo: Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

Jerrel Perez, the girl's father, has been calling on the school district to release the footage. He argues the district attorney should bring charges against Kenosha officer Shawn Guetschow for placing his knee on Perez's daughter's neck to restrain her — a move that was banned for Wisconsin law enforcement officers last year.

Surveillance footage appears to show another student approach Perez’s daughter, before Perez’s daughter pushes the other student and a fight ensues.

Almost immediately Guetschow, 37, intervenes in the fight by pulling the other student off Perez’s daughter. Guetschow then scuffles with Perez’s daughter, before falling to the ground and striking his head on the cafeteria table.

Guetschow then restrained Perez’s daughter by pushing her head into the ground and placing her in a chokehold restraint, for roughly 25 seconds, using his knee on the girl’s neck. The officer then handcuffs the girl and walks her out of the cafeteria.

Perez's attorney, Drew Devinney, said Guetschow was acting in an on-duty capacity once he placed Perez's daughter in a chokehold. He and his client are calling for criminal charges for the officer. The Kenosha district attorney hasn't announced charges for any of the parties involved.

Devinney said they will be filing suit against the officer, school district and police department.

The school district initially placed Guetschow on paid leave. He resigned from his part-time security job with the school on Tuesday, according to Tanya Ruder, KUSD's chief communications officer.

"As it appears that this incident may lead to litigation, the district will provide no further details at this time," Ruder said.

In his resignation letter, Guetschow called out the school district for lack of support and said the incident has placed a heavy burden on his family.

"Given the events that have taken place and the escalated attention this incident at Lincoln Middle School has caused in the community, mental and emotional strain it has bought upon my family, and the lack of communication and or support I have received from the district, I can no longer continue my employment with the Kenosha Unified School District," Guetschow wrote, misspelling brought, to Kenosha Superintendent Beth Ormseth.

The Kenosha Police Department did not respond to questions about the incident or Guetschow.

Perez, Devinney and activists from Kenosha, Milwaukee and Chicago stood outside the school district on Wednesday, where they likened the incident to Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin and his use of knee chokehold restraint when he murdered George Floyd.

Devinney said Wednesday that his client was the subject of bullying and was defending herself. Further, he said "at no point did Jerrel's daughter push or strike at this officer." He also said Perez's daughter yelled out she couldn't breathe while the officer had his knee on her neck.

Perez said his daughter is in therapy and seeing a neurologist for her injuries and has been medically excused from school for two weeks.

School board member Todd Price stood in solidarity with Perez at Wednesday's press conference. Price said he was standing there as a parent first. The school board will hold a meeting on March 22 at 7 p.m.

Waves lap ashore near condo buildings in Sunny Isles, Fl., on Aug. 9, 2021. Rising sea levels are seen as one of the potential consequences of climate change and could impact areas such as Florida's Miami-Dade County. (photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Waves lap ashore near condo buildings in Sunny Isles, Fl., on Aug. 9, 2021. Rising sea levels are seen as one of the potential consequences of climate change and could impact areas such as Florida's Miami-Dade County. (photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

The country's top financial regulator is expected to propose new disclosure rules that would require companies to report their contributions to greenhouse gas emissions as well as how climate change might affect their businesses.

It's part of a global push by regulators to acknowledge climate change as a risk to their economies and their financial systems.

Investors are demanding companies disclose potential risks from climate change. But some businesses worry climate-related government mandates could be invasive and burdensome.

Here's what to know ahead of the SEC announcement.

So what is the SEC's goal?

Some companies, including Apple, already disclose their greenhouse gas emissions as well as those from their suppliers. But the U.S. lacks clear standards on what exactly companies have to report to their investors when it comes to climate impact and risks. The SEC wants to change that.

Any rules proposed by the SEC's four commissioners, led by Chair Gary Gensler, would be subject to a public feedback period.

"There will be a whole new round of focus on climate disclosure rules, and what it is going to mean for companies, investments, and, of course, climate itself," says Rachel Goldman, a partner at the law firm Bracewell.

Why adopt enhanced climate disclosure rules?

The push is largely coming from investors themselves, who are increasingly keen to know how climate change might impact the businesses they fund.

The White House also wants to address climate-related financial risk. President Biden issued an executive order last year pushing the federal government to help identify the risks posed by climate change.

Though the regulator has been considering the issue for years now, efforts accelerated under the SEC's former acting chair, Allison Herren Lee, and have continued under Gensler.

"When it comes to climate risk disclosures, investors are raising their hands and asking regulators for more," Gensler told a forum on green investments last year.

"Today, investors increasingly want to understand the climate risks of the companies whose stock they own or might buy," he added.

Do companies support enhanced climate disclosures?

Most companies acknowledge the impact of climate change and many have already pledged to move toward net-zero emissions.

But some companies fear SEC mandates could be a headache and leave them potentially liable to lawsuits given how difficult it is to measure emissions and climate change risks.

Anne Finucane, who oversaw Bank of America's work on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) matters as the bank's vice chairman, supports enhanced climate rules. She says that reporting on climate risk is demanding and it can be duplicative.

"Right now, there at least a dozen third parties, NGOs, that measure companies — all companies, not just financial institutions," she said in an interview with NPR before she retired in December. "It's like a Venn diagram. Eighty percent is the same, but 20 percent is different."

Many Republican lawmakers are opposed to financial regulators wading into climate change.

This month, Sarah Bloom Raskin, President Biden's nominee for a top regulatory post at the Federal Reserve, was forced to withdraw after attracting strong opposition over her stance that bank regulators should pay more attention to climate-related risks.

So will the SEC rules spark a big fight?

It depends. It's still unclear how wide-ranging the SEC's disclosures rules will be and whether they would impact every publicly traded company.

But in particular, businesses are worried the SEC could require companies disclose what are called "Scope 3" emissions. Those are emissions generated by a company's suppliers and customers. (Scope 1 is the emissions generated by the company themselves, while Scope 3 measures the emissions from the energy consumed, like electricity for example)

Any moves by the SEC to require Scope 3 disclosures could spark a big corporate pushback, and so could any disclosure rules that companies feel are too wide-ranging or comprehensive.

Gretchen Whitmer, Michigan’s governor, was the target of rightwing ire for her Covid restrictions – but also, perhaps, for being a woman and a Democrat. (photo: Paul Sancya/AP)

Gretchen Whitmer, Michigan’s governor, was the target of rightwing ire for her Covid restrictions – but also, perhaps, for being a woman and a Democrat. (photo: Paul Sancya/AP)

Four militia group members are on trial for an alleged plot to abduct Gretchen Whitmer but did informants and agents egg on big-talking good ole boys?

Adam Fox, Brandon Caserta, Barry Croft Jr and Daniel Harris were charged in October 2020 with conspiring to abduct Whitmer from her northern Michigan vacation house. Their motive, say prosecutors in Grand Rapids, was anger over the Democrat’s Covid-19 restrictions and their plan has become a symbol of rising far-right violence and the threat it represents to US democracy.

At the moment the FBI arrested the men, prosecutors argued in court, they had plans to acquire a bomb to blow up a bridge near Whitmer’s home to hinder police. Jurors, they have said, would see social media posts and hear secretly recorded conversations, highly inflammatory language and details of a plan to take down a “tyrant”.

When they were arrested the case seemed a slam dunk. But as more evidence has unfolded and the trial has begun, a different narrative has emerged. Far from being a dedicated bunch of coup-plotters, their attorneys argue, the Wolverine Watchmen are hapless victims of FBI entrapment who had been induced by paid informants to commit crimes they would not otherwise have considered.

The FBI, according to defense filings, deployed at least 12 informants, as well as several undercover agents. “There was no plan, there was no agreement and no kidnapping,” defense attorney Joshua Blanchard said last week.

It is not an entirely outlandish claim. The defense’s argument of FBI entrapment draws on a long history. In the post 9/11 era, when internal US security agencies focused on the existence of Muslim extremist plots, several prosecutions, including of the Newburgh Four, hinged on informants actively promoting a plot before turning would-be perpetrators over to the government to be tried on conspiracy charges.

Activists and civil rights experts have argued that the FBI has frequently overstepped boundaries, essentially egging on people to participate in plots and locking up people for crimes that they would never have committed had it not been for the intervention of law enforcement.

Those counter-terrorist techniques, reapplied to the threat of white nationalist radicalization that Joe Biden has repeatedly said is the “most lethal threat” to the US, will play a part in how the Wolverine Watchmen trial unfolds. It has raised the question: were the Wolverines more dupes than dedicated terrorists?

“Counter-terrorism tactics have evolved because there wasn’t a lot of international terrorism occurring on the US soil,” said Mike German, author of Disrupt, Discredit and Divide: How the FBI Damages Democracy. “But there’s still pressure to make cases and that’s caused the FBI to adopt this methodology of manufacturing terrorism plots.”

German, who served 16 years as an FBI special agent and is now attached to the Brennan Center for Justice and NYU law school, says the tactics have migrated to far-right groups, though not necessarily with much success. The Hutaree militia case of 2010, in which nine members of a Michigan group infiltrated by the FBI were accused of plotting to kill a police officer, ended in acquittal.

“When these tactics first started it was easy to get the public on the FBI’s side just by making allegations,” German said, recalling the case of the Liberty City Seven – a Muslim extremist plot to blow up Chicago’s Sears Tower that ended, after three trials, in five convictions.

“The problem is, they’re manufacturing crimes and that’s not the job of a law enforcement agency – to make themselves look good by solving crimes they create – and there’s no legitimate government purpose in manufacturing a plot,” he said.

Another issue, German says, is that there’s more white supremacist/far-right activity in the US than there ever was Muslim extremism. But the federal government doesn’t maintain a database on white extremist violence, lumping all extremism – white nationalist, environmentalist – in one category under the Hate Crimes Statistics Act (1990) and the National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism, announced last year.

And that, German points out, has left the government without accurate data on what has occurred and in a position of trying to predict and prevent what might occur. “The issue is starting with talk and getting to violence, but not vice versa,” he said.

In the Wolverine Watchmen case, the four defendants are accused of taking deliberate steps toward violence, including secret messaging, gun drills and a night drive to northern Michigan to scout Whitmer’s vacation house. Two of the six men initially arrested, Ty Garbin and Kaleb Franks, have pleaded guilty and will appear as government witnesses.

But defense attorneys claim that one of the men on trial, Barry Croft, was lured to militia meetings and gun training by “Big Dan”, an informant with a long criminal history who was paid $54,000 by the FBI.

Big Dan’s handler was Jayson Chambers, an FBI agent who was looking to build a security consulting business that included “online undercover techniques” and had participated in investigations of Muslim “plots” involving inducements.

Another informant, Stephen Robeson, has pleaded to various felonies. Another government witness, FBI agent Robert Trask, was fired after beating his wife after a swingers party. Another was accused of perjury.

Still, anti-government extremism in the upper midwest comes with a track record that includes Terry Nichols, a participant in the 1995 Oklahoma city bombing, who was from Michigan. Fourteen men from the state have been charged in connection with the January 6 insurrection.

In 2020, hundreds of protesters, some armed, some driving Humvees, attempted to enter the floor of the legislative chamber of Michigan’s state capitol as lawmakers debated Whitmer’s request to extend emergency Covid powers. Some compared Whitmer to Hitler.

“I’m not surprised this is coming out of Michigan because of its history and because Governor Whitmer has drawn a lot of negative attention for her lockdown procedures,” said Amy Cooter, a sociologist at Vanderbilt University and author of Problems Predicting Extremist Violence.

Cooter suggests the alleged plot against Whitmer was not merely about Covid restrictions but also because she is a woman and a Democrat. In Cooter’s experience groups that indulge in extremist talk rarely translate that into action.

“The problem is there’s always potential for it to evolve into something more,” Cooter adds. “So when a specific person is targeted I think we have to take it seriously.”

Nils Kessler, the assistant US attorney prosecuting the current case, has drawn explicit parallels between the plan and the January 6 attack. “As the Capitol riots demonstrated, an inchoate conspiracy can turn into a grave substantive offense on short notice,” he wrote in a court filing.

Whatever the jury’s findings in the Wolverine case, Cooter predicts, groups on the right are “going to assume they were set up and [it] could galvanize some to further action”.

JoEllen Vinyard, a professor of history at Eastern Michigan University who notes that today’s white nationalists have antecedents in racist groups like the KKK, says groups like the Wolverine Watchmen “see themselves as standing for democracy and in many cases saving the country from its leaders”.

Michigan, she said, gets a lot of attention because groups there appear to be periodically better organized, depending on their leadership. “It’s hard to know the role of the FBI in this but these particular guys don’t seem to be the type that could exert much leadership,” she said.

She added: “There’s a lot of unrest in this country that we haven’t always recognized, and people have different reasons at different times. They were encouraged, of course, by Donald Trump. He didn’t create it, but he gave these people a sense that they were right and justified in their actions.”

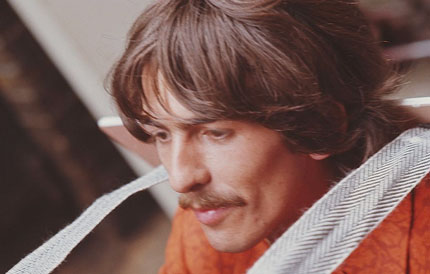

George Harrison | Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)

George Harrison | Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth)

Lyrics George Harrison, Give Me Love (Give Me Peace On Earth)

Written by, George Harrison.

From the 1973 album, Living in the Material World.

Give me love, give me love

Give me peace on earth

Give me light, give me life

Keep me free from birth

Give me hope, help me cope

With this heavy load

Trying to touch and reach you with

Heart and soul

Om...

My Lord

Please take hold of my hand

That I might understand you

Won't you please, oh, won't you?

Give me love, give me love

Give me peace on earth

Give me light, give me life

Keep me free from birth

Give me hope, help me cope

With this heavy load

Trying to, touch and reach you with

Heart and soul

A view from near Vila Realidade on Highway 319, which runs more than 500 miles through the core of the Brazilian Amazon. (photo: Raphael Alves/AP)

A view from near Vila Realidade on Highway 319, which runs more than 500 miles through the core of the Brazilian Amazon. (photo: Raphael Alves/AP)

A highway is speeding the destruction of the vital global resource. Along this stretch, the killings have already begun.

There was an unmarked dirt road branching off from the highway. It cut into the jungle and led out of sight. Lucas Ferrante, the environmental scientist leading this journey, wanted to go down the road and see what — and who — was hidden behind the trees.

“This is illegal deforestation,” he said.

The driver, who lives on the highway, told him it would be too dangerous to proceed. These rough-hewn side roads are often the work of armed criminal groups. The groups, which dominate this stretch of the forest, had unleashed a wave of fire and destruction that was transforming much of southern Amazonas state into smoldering pastureland. The way they solve problems is with violence. People disappear. Their bodies are never found. Our driver feared the trouble that following this road would bring.

Ferrante, who has spent years detailing the region’s lawlessness in academic journals, understood the highway’s dangers and uncertainties better than most. He had been threatened in anonymous calls and messages — then abducted in November 2020 and told to keep quiet.

Another researcher documenting the destruction received this text: “You’re going to burn in the fire. It will be a barbecue. Message delivered.”

But Ferrante, 33, believed traveling here was worth the risk. He had come to see this highway, a reddish gash scarring a quilt of green, as one of the Amazon’s last stands. A photographer and I had now joined him on this journey to its further reaches.

Stretches of the highway have been improved in recent years, making travel easier and unleashing a surge of deforestation. Many in the rainforest want the government to complete the job. President Jair Bolsonaro, who has worked to ease and undermine environmental regulations to promote development, says paving the highway would fulfill “a wish of the Amazonian people.” His vice president, a general in reserve, said he’d eat his own military beret if current officials don’t get it done.

For many in Manaus, a city of 2.2 million cut off from Brazil’s main highway system, the road symbolizes something close to freedom — a lifeline that connects them to the rest of the country and paves the path toward development.

“BR-319: It’s our right,” says the slogan plastered across social media and highway signs. In a region of both vast resources and pervasive poverty, many say the time has come to use what’s there for the taking, to seize the better life long denied by isolation and geography, to push back against federal laws and environmentalists who seem to care far more for trees than people.

The outcome of the emotional political clash, scientists say, has implications not only for the rest of the forest but the world. The Amazon is a crucial bulwark against global warming, helping to slow the inexorable march of climate change. But researchers warn that finishing the highway and subsequent state roads would open up its core to destruction. Scientists at the Federal University of Minas Gerais found in 2020 that paving the highway would quadruple deforestation here over the next three decades.

“That would be the end of the forest,” said Carlos Nobre, a climate scientist who focuses on the Amazon.

The Amazon is already believed to be at the precipice. If much more is lost, scientists warn, the forest could suffer destabilizing ecological changes that convert immense swaths into degraded open savanna. What has historically been a carbon sink could suddenly become a “carbon bomb,” upending the world’s efforts to avert catastrophic warming. Already, some regions of the Amazon are exploding — emitting more carbon gas than they absorb. The shift has been particularly acute in the most deforested sections of the Amazon’s degraded southeast, where in the past 40 years the average temperature during the annual dry season has risen more than 4 degrees.

But the wave is now moving deeper into the forest. The two cities in Brazil that produce the most carbon gases — São Félix do Xingu and Altamira — are far from the most populous. They’re both in the Amazon, near large infrastructure projects that have brought development, but also deforestation and extreme violence.

Along this stretch of BR-319, where the destructive process is well underway, the killings have already begun.

Humaitá, the town closest to our position, recorded 15 homicides in October alone — five times the monthly average. Police said most were connected to rising land-grabbing and deforestation. On one cattle farm built on cleared land, several workers had recently disappeared. First went a farm worker named Jeferson Bungenstab, 37. Then followed one of the last men to see him alive, a housekeeper named Nelson Antônio da Conceição, 33. Police didn’t yet know what had happened to the men, but had begun to suspect the worst.

Ferrante, unaware of the rash of killings and disappearances, peered down the road. He had made up his mind. He told the driver to pull out onto it. The photographer, Raphael Alves, and I looked at each other. I felt a wave of nerves. Alves got his camera ready. The truck started forward.

“We’re entering an area of great risk,” warned the driver, who asked not to be named out of concern for his safety.

Heading down the path and into the forest, we didn’t yet know how much.

‘Catastrophic’ environmental consequences

In the late 1960s, several years into Brazil’s two decades of military rule, a small group of generals started drawing lines on the map. They were strategizing the greatest military excursion in Brazilian history: the conquest of the Amazon. They charted out a blitzkrieg of highway projects to tame and integrate the rainforest into the larger country. The Trans-Amazonian Highway cut across the Amazon’s belly. Another road cleaved massive Pará state. A third highway lassoed Venezuela to the Brazilian Amazon.

The new roads fueled surges in both migration and deforestation. In a region where people have long seized land and tried to establish ownership by occupying it, the highways filled with travelers — poor migrants, land speculators, ranchers — chasing fortune and opportunity. Many ended up along the Amazon’s southern sweep, a bow-shaped area that now concentrates 75 percent of the forest’s losses and has come to be known as the “arc of deforestation.”

Years of analyses illustrate how roads often lead to deforestation. It’s called the fishbone pattern. The highway forms the spine. Then speculators, illegal loggers and local officials build roads radiating outward: the ribs. Studies have shown that the vast majority of deforestation in the Amazon has occurred within 30 miles of a major road.

BR-319 was different. It was constructed in the 1970s, like the others, but attracted far less notice. Merchants in Manaus found cheaper methods to transport goods. Migrants went to other parts of the forest. The highway — built hastily during the rainy season and battered annually since then with an average rainfall of 87 inches — fell into disrepair and became impassable for much of the year. In 1988, it was effectively shut down, sealing off both the core of the Amazon and also Manaus, where a divisive debate over its future has seesawed ever since.

Transportation and environmental authorities in 2007 approved the restoration of portions of the highway, but not its vast middle. Then they authorized the rudimentary “maintenance” of the highway’s decayed midsection — but not paving it. Local politicians promised before the 2018 elections to finish the whole thing. Environmentalists countered that it made no economic sense: Studies showed it was cheaper to transport goods along river routes.

Then, last year, a new coronavirus variant crushed the city, depleting its oxygen supplies. The road’s supporters seethed: If the highway had been passable, oxygen would have arrived in time. Instead, dozens suffocated to death.

The raw nerves surrounding the issue have been exposed at boisterous public hearings.

At one September session in Manaus, an American scientist read a lengthy prepared statement. “The BR-319 highway is economically unviable,” said Philip Fearnside, who contributed to the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 for climate research. He called Brazil’s decision-making process “deficient.” And the environmental consequences if the highway were paved? “Catastrophic.”

The highway’s supporters in the audience started to boo. Fearnside yelled over them in his heavily accented Portuguese. Then his mic was cut. Video shows the next speaker striding to the front.

“Why would someone from the United States come here for this?” demanded Sérgio Kruke, director of the Conservative Amazonas Movement, pointing at Fearnside. “How could that be?”

The audience clapped and cheered. Kruke shouted into the microphone.

“This house is ours! If we want to knock down all of the trees, we’ll knock them down!”

A highway in three acts

Ferrante, a researcher affiliated with the National Institute of Amazonian Research, sat in the front row at that hearing, increasingly restive. He is Brazilian, but believes the forest belongs to the world. Terrified by the implications of paving the highway, he had partnered with Fearnside to show how even its simple maintenance had already harmed the rainforest, and also threatened Indigenous communities.

But sitting in the audience, the PhD candidate saw the studies hadn’t been enough. Few were convinced of his view. He needed more proof. He needed to make another trip down the highway. We asked to join him.

We set out at 3 a.m., caught the first ferry out of Manaus and, as the sky reddened over the Amazon River, reached the highway. Ferrante thought about the long road ahead.

BR-319 is a highway in three acts. The first 100-some miles are paved, marked by road signs and split by yellow stripes. Then it begins to devolve into what’s known as the “middle stretch”: 250 miles of dirt and crevices and mud-slicked stretches so formidable that they cause vehicles to spin out and tumble off the road. The final act is smoothed out — and speeds travelers into one of the most dangerous parts of the Amazon, on the edge of the arc of deforestation, where environmental destruction and violence are rampant.

Ferrante secured his N95 mask, less to protect him from Brazil’s rampant coronavirus than to hide his identity.

“We are going against the entire world here,” he said, a world he worried wished him harm. Intense and combative, Ferrante knew his work and demeanor had made him enemies. He’d argued heatedly with highway proponents. He’d accused the government in opinion pieces of intentionally destroying the Amazon. He’d written academic study after academic study: On illegal loggers along the highway. On remote Indigenous groups sidelined during highway discussions. On illegal gold prospecting near the highway.

Now he feared he was a marked man. In November 2020, he’d climbed into a car he’d assumed was his Uber outside his apartment. The driver took him far off course and, according to the statement Ferrante gave state authorities, attacked him with a sharp object, scratching his arms. “You’re messing with things you shouldn’t be,” Ferrante said the man told him. Ever since, Ferrante has perceived threats nearly everywhere.

He saw them again here now, as his driver pulled to a stop before a stagnant body of water. Runoff from road maintenance had turned the water a soupy brown. Ferrante looked back and forth — coast clear — and got out to investigate. “We have to hurry,” he said. “We can’t stay in one place for too long.” He noted the environmental damage — fish killed, water source poisoned — and got back in the truck. The next water source down road was the same. And the one after that: brown and dead.

As we drove on, the forest was an uninterrupted blur of verdant greens — except where it wasn’t. Every now and again, a whole chunk of the forest had been bitten off, leaving behind charred trees, smoldering earth, smoky air. Cattle, cultivated for beef, wandered through the burned brush. Often at the center of these ashen expanses was a single shack inhabited by a squatter. The forest was gone, and the land had been claimed.

“You can still smell the fire,” Ferrante said.

“This was all forest three months ago,” the driver said.

The road beneath the truck began to change. The asphalt cracked open, then receded. The remnants looked like pieces of broken pottery. A sign said the paved portion of the highway had come to an end. There was now only a line of red earth streaking into the distance. We had reached the worst part of the road.

“The middle stretch,” Ferrante said.

Plunging deeper into the forest’s grip

There were no signs of humanity here. The temperature was lower. The forest was dense and dark. As we pushed deeper into its grasp, the highway became a bog of thick mud. The vehicle struggled forward — past a marooned truck, an abandoned van, a jaguar skirting across the road. Finally, we reached a small collection of dirt-covered homes along a river.

Inside a wooden house on stilts, an old woman had spent 50 years waiting.

Nilda Castro dos Santos, 74, was young when she came here, following her father from a dead-end town elsewhere in Amazonas. The road then was “new and beautiful.” She viewed it as a promise: There would be work, opportunities, a better life for her children. The people built a community with small restaurants, shops, serving residents and visitors. But then their lifeline — the highway — began to atrophy. No one came to fix it. The flow of travelers stopped. Neighbors moved away.

Now the town felt as dead as the highway itself: silent and sun-wilted.

Every day now, Castro sits and waits — for the government to remember this place, for the highway to be paved, for the fulfillment of a promise she feels has been delayed a half-century.

“I’m scared I’ll die without ever seeing it paved,” she said. “We have been able to survive here, but we haven’t been able to live.”

A gnarled man walked down the dirt street. Rosineu Batista, 59, spoke of his brother-in-law. The man had recently fallen ill. But the highway had been impassable, and without proper care, he died. Batista believes a paved highway might change things here. Maybe he’d be able to have more to eat than whatever he can fish out of the river.

“But you’re not worried about criminal land grabbers coming in with a paved highway?” Ferrante asked.

“Yeah,” he said. Then he looked out at the desolate village: “But …”

We continued on. The truck bumped and jostled across a river, over rickety bridges, past signs hailing the coming maintenance. Rains rushed through. Darkness enveloped the forest. Vila Realidade, a gritty highway village settled by squatters, came and went.

Then, as suddenly as it had deteriorated, the road improved. The dirt smoothed out. Shacks appeared in the distance.

Anderson Ferreira, 30, stepped out of one. He’d grown up on the highway. For most of his life, the forest was all there was. But then workers began improving the highway. Outsiders arrived from faraway states.

The forest started to burn.

Now Ferreira tends a small house on recently deforested land, looking after someone else’s cattle. He badly wants the highway paved — it’s all anyone here talks about. But he also thinks of the cost.

“To be human is to want to live in harmony with nature,” he said.

Beyond his house, the smoke was rising. We had made it to the arc of deforestation.

‘This is going to be a massive hidden farm’

Since 2015, deforestation along the highway has grown ninefold. A sweep of forest nearly the size of Washington, D.C., is lost every year. Nowhere is the destruction more evident than here, in the vast city limits of Humaitá, the largest municipality along the highway, where the road finally smooths out. Patch by patch, the forest here is being stripped clear. Illegal roads streak into the receding tree line.

Ferrante’s research team has started mapping the roads, even driving down several. They have found illegal gold prospecting, logging and burned forest. One criminal forest broker tried to sell them land, the team wrote in the academic journal Land Use Policy. He offered two acres of deforested land for $570. The same amount of forested land would go for $3.80, but the buyers would have to deforest and occupy it themselves. During a visit to the site, the “land-grabbing agent” kept a gun in his hand.

The deforestation has been closely accompanied by the threat of violence. In 2017, armed illegal miners in broad daylight burned down the offices in Humaitá of Ibama, the federal environmental law enforcement agency. Inspectors investigating illegal sites now equip themselves for combat: long rifles, camouflaged fatigues, bulletproof vests. Rural landowners have been targeted. Criminals “come and execute the people on the land so they can lay claim to it,” Amazonas state police detective Mário Melo said.

Ferrante had thought extensively about the perils of his work. Brazil is one of the world’s most dangerous countries in which to investigate environmental crime. Twenty environmentalists were killed in 2020 alone. But he told himself — and his family — that it wouldn’t happen to him. He was too methodical, too careful. Still, some risk was unavoidable: “We can only discover certain things by going inside.”

Now he was inside again, going down another illegal path, looking out into the dark forest.

“This is new,” he said. “We don’t know what we’re about to find.”

Then it was upon him: A mile down the road, there was a large wooden sign. It said the land here — which was public and protected — was private and for sale. It listed a phone number and the name “Martelos.” Ferrante shook his head and took a picture. The road forked to the right and opened on a vast clearing.

A wash of blackened earth. A string of shacks. Electrical wiring. A fence to hold in the cattle.

“This is going to be huge,” Ferrante said. “This is going to be a massive hidden farm.”

If someone found him here, he worried, there would be trouble. Difficult questions would be asked. Someone might recognize him. He could easily be disappeared. He was hours out of cellphone range. No one would ever know. Working quickly, Ferrante marked the property’s coordinates, took some pictures and, planning to alert the authorities, got back into the truck. He was furious.

“This is land that belongs to the country!” he fumed. “They have just invaded it and ripped out all of the trees!”

He then heard the squawking of birds. It was getting louder. The truck approached a fence post. Vultures were sitting on it.

Alves, the photographer, went out to document the scene. Ferrante and I followed. We were looking down at the dirt path when we heard the screaming. It was coming from Alves.

Alves was running toward the truck. He yelled that he’d found a body. It had been a man. His hands were tied. Ferrante told the driver to start the truck and keep it running. He then went to see for himself. And there, at the base of a ditch beside the fence, he came upon the motionless form.

The man’s face was disfigured. His wrists were bound. He appeared to have been executed.

The body of Nelson Antônio da Conceição, the farm housekeeper who had disappeared, had lain in this ditch for days. Police say he vanished shortly after telling them what he knew about the disappearance of the farm worker Jeferson Bungenstab. Both men, police say, worked for the same cattle rancher, Celso Deola, 59. Conceição, police told me, had accused him of ordering the disappearances of Bungenstab and others. Police said Deola, an alleged land grabber and illegal deforester, would cheat his workers on payday and then resolve the resulting pay disputes with his “pistoleiro” — a reputed hit man named Edmilson de Jesus Chagas, 35, who carried a Glock 9mm.

Deola did not respond to multiple requests for comment. A relative said: “Unfortunately, he’s my uncle. I hope this time he pays for what he’s done.”

Ferrante took one last look at one of the alleged victims. Then he raced back to the truck. The driver pulled out as his door closed. Ferrante looked up, then felt a swell of panic: In front of the truck, two men on a motorcycle were coming toward us. “Don’t stop,” Ferrante told the driver. “Whatever you do, keep going.”

The truck passed the motorcycle.

“Go, go, go.”

The men kept going in the other direction. The truck broke the tree line and made it back onto the highway. No one was following.

“That’s not going to happen to me,” Ferrante said. “I’m not going to end up dead.”

The truck sped to the nearest town. We heatedly discussed what to do. In a region where many local officials are connected to environmental crime, the police would be difficult to trust. It would be easier and safer to wait until after we’d left the region to report the body. But then we thought of this man’s family, waiting, never knowing what had happened to him. We had to tell someone now. So that evening, Ferrante reported the body, then took the police back to it.

In the weeks to come, police would accuse Chagas and Deola of killing his two employees and announce warrants for their arrest. Officers would mortally wound the alleged hit man in a firefight at his house, police said. Next they would try to visit the rancher, police said, but Deola had already fled. Police say that he is now considered a fugitive. Authorities would release pictures of what they say was discovered at his ranch: heavy-caliber rifles, silencers, scopes, rounds and rounds of ammunition. Ferrante would feel sickened by how close he’d come to meeting that violence.

But for now, on this highway, Ferrante felt as if it was receding behind him. The road took us further south — back into cell range, out of the lawless frontier, and, finally, into a placid expanse. The highway was now fully paved and marked. On either side were pastures stretching to the horizon. The wave of deforestation had already passed through.

The highway had been traversed, and this was how it ended: not in pitched lawlessness, but in a stream of pleasant farmhouses, in cattle meandering through well-maintained fields — in another chunk of the forest cleared away and the Amazon brought yet closer to its death. The guns were gone. There were no more bodies. The criminals had been replaced by legitimate business people. It was as if the forest had never existed at all, and the future was already here.

“The transformation is complete,” Ferrante said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.