Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

At the same time, Israeli protesters mounted a massive miles-long march on Jerusalem.

A committee of the parliament, dominated by a right-wing coalition that includes out-and-out extremists, reported out an article of the new law on the judiciary that removes the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review on the grounds of whether a law is “reasonable” in the light of Israel’s basic laws on issues such as human dignity. The country does not have a formal constitution, but some laws, on human rights issues, have been taken as the basis for overturning subsequent legislation that contradicts the basic laws. Removing the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review would make Israel an elective dictatorship, where the ruling party can pass retrograde laws permitting discrimination against women, Christians, Muslims, secularists and gays, in accordance with the principles of the Israeli Religious Right.

The Supreme Court has also branded some squatter-settlements by Israelis on Palestinian-owned land in the West Bank as illegal, and extremists Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir want to prevent the court from so ruling in the future.

It is expected that the government will pass the controversial legislation on Monday, since the current coalition has more than enough votes to do so and Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu is unmoved by the huge demonstrations that have been mounted for 28 weeks in a row. Netanyahu is on trial for corruption, and the new legislation may save him from being convicted.

Thousands of protesters against the new law set out this week from Tel Aviv, walking on foot to the Givat Ram district of Jerusalem where the Israeli parliament or Knesset meets, to stage a big demonstration this weekend and into Monday against the passage of the law neutering the Supreme Court. The journey is about 44 miles. On Friday evening, the group, some 10,000 strong, halted 9 miles outside Jerusalem to hold Friday evening worship ceremonies.

Although they never blocked the main road, Minister of National Security Itamar Ben-Gvir, and notorious extremist and racist, ordered the police chief to clear it with as much force as needed. Ben-Gvir seems to want to treat secular Jews rather as the occupied Palestinians are treated. It shows that once you go in for occupying other people and depriving them of their rights, it eventually blows back on the metropole.

The demonstrators issued the following statement:

“We are entering the most fateful days in the history of the state. This is a war of independence for the vast majority of the citizens of Israel, patriots who have given up everything and have been fighting for months for its future as a liberal democracy. We are in the phase before the destruction of the Third Temple, and the government and its president must hear the people’s cry and stop. Starting Saturday evening we will all be in the streets, and only with firm resistance will we stop the dictatorship.”

The reference to the destruction of the Third Temple is almost apocalyptic in tone. Solomon’s temple, the center of Jewish worship according to the Bible, was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BCE. The Iranian Achaemenid Empire then conquered the Near East and allowed Jews to return to the Levant, to a special district for them named Yahud. There they built the Second Temple. It was destroyed by the Romans in 70 A.D. Thereafter Judaism developed as a different sort of religion, based in scattered communities rather than around a central cultic site, and developing rabbis who advised on the practice of the religion in the absence of a temple. The destruction of both edifices is lamented in Jewish tradition. The protesters are saying that Israel as a secular liberal democracy functioned sort of as a Third Temple for the Jewish people, and that Netanyahu and his colleagues are no less a threat than had been the Babylonians and the Romans.

READ MORE  'The Supreme Court ruled that Alabama must create two congressional districts that would encompass majority-Black electorates. Republicans in the state didn't listen.' (photo: Jim Bourg/Reuters)

'The Supreme Court ruled that Alabama must create two congressional districts that would encompass majority-Black electorates. Republicans in the state didn't listen.' (photo: Jim Bourg/Reuters)

The Supreme Court ruled that Alabama must create two congressional districts that would encompass majority-Black electorates. Republicans in the state didn’t listen.

In a June ruling, the conservative-leaning Supreme Court surprised some onlookers when it ruled 5-4 that Alabama’s new map of congressional districts likely violated the Voting Rights Act as an illegal racial gerrymander. Under that map, only one out of Alabama’s seven districts had a majority Black electorate, even though Black residents comprise more than a quarter of the population.

The justices, upholding a lower court’s ruling, ordered Alabama’s Republican-controlled legislature to redo the maps, this time carving out a second Black-majority district, “or something quite close to it.”

But Republicans in the state didn’t go through with it, effectively ignoring the high court’s order, opponents argue.

After a special session convened in response to the ruling, Alabama’s legislature passed a new map on Friday that created only one seat with a majority Black electorate, NBC reported. Another seat included in the revised plan has a 40 percent Black voter base.

The new maps passed a vote on Friday afternoon—as a court-mandated deadline loomed—and got Alabama governor Kay Ivey’s signature that night. They advanced over the objection of Democratic lawmakers, as well as the advocacy groups that successfully challenged the previous maps—and which have promised to fight the new one as well.

"The Legislature knows our state, our people and our districts better than the federal courts or activist groups, and I am pleased that they answered the call, remained focused and produced new districts ahead of the court deadline,” Ivey said in a statement Friday night.

READ MORE  Dr. Kristin Lyerly, an obstetrician-gynecologist, lives in Green Bay, Wisc. These days she drives across the border to work in rural Minnesota. 'I want to practice medicine here,' she says, 'but first we have to get rid of this law.'

Dr. Kristin Lyerly, an obstetrician-gynecologist, lives in Green Bay, Wisc. These days she drives across the border to work in rural Minnesota. 'I want to practice medicine here,' she says, 'but first we have to get rid of this law.'

Obstetricians describe patients who cannot comprehend having to carry nonviable pregnancies. And only one pharmacist in town will fill prescriptions for abortion pills.

“We didn’t even know germs caused disease back then,” said Dr. Kristin Lyerly, an obstetrician-gynecologist who lives in Green Bay.

Like undertakers and garbage haulers, obstetricians see the nitty-gritty of human existence that can be ghastly and grotesque. A fetus with organs growing outside its body. A woman forced to birth a baby with no skull to push open her cervix.

OB-GYN Dr. Anna Igler regularly performed abortions for medically indicated reasons before the Supreme Court overturned the right to abortion last year. She is beyond fed up.

“I’m at a different level with it now,” she said. “Part of me is so upset at people for sticking their head in the sand.” With her world inside a Green Bay hospital in turmoil, she said, she cannot fathom that people might be oblivious to the government’s incursion into their medical care.

“So many people I’ve talked to have no idea what our laws are in our state,” she said.

Even now, a year later, Igler said, expectant parents come into her office with the assumption that if their fetus has a lethal genetic disorder, like anencephaly or trisomy 13 or 18, they can end the pregnancy safely.

“They are shocked when I tell them they can’t,” Igler said, “and they are shocked when I tell them we are following the law from 1849.”

She’s referring to the state’s original abortion law, which was passed before the Civil War, when women could not vote or own property. The law makes it a felony to perform an abortion at any stage of pregnancy, unless it would prevent the death of the pregnant person.

It had been some time since these women were together, and they were eager to compare notes. The certified midwife spoke on the condition of anonymity because she’s not authorized to talk to the media and is concerned about losing her job at a local health system. “My biggest issue right now is getting medication to end a pregnancy that has already passed,” she said. “I’m finding locally that pharmacists just won’t dispense the medication.”

She offered a rundown: One pharmacist told her patient the medication, misoprostol, which causes cramping to expel the pregnancy tissue, had expired. Another, at a Walgreens, simply canceled the order. A third said he needed preauthorization, noting, “It’s a $3 pill, and we’re not going to get preauthorization on a weekend.”

The midwife said she and physician colleagues in her practice have half-joked that they’d send a gift basket to one pharmacist in town she’d found who will fill their prescriptions.

Now, when a patient miscarries, the midwife said, “we warn patients that this might happen, and they are like, ‘But my baby is dead,’ and I tell them, ‘I’m sorry. I don’t know why, but a lot of pharmacists in Green Bay think it’s their job to police this.’”

A year into this new era of compulsory birth for most women with pregnancies, the dismay and disorientation of those first few months have settled into, if not acceptance or resignation, a kind of chronic fear. Obstetricians and gynecologists are fearful of practicing medicine as they were trained.

A recent survey by pollsters at KFF of OB-GYNS in states with abortion bans found 40% felt constrained in treating patients for miscarriages or other pregnancy-related medical emergencies since the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision last summer. Nearly half of them said their ability to practice standard medical care has become worse.

The specter of felony charges and losing a medical license has led to futile exercises.

Under the Wisconsin abortion ban — and bans in at least 13 other states — physicians who cannot detect fetal cardiac activity should, in theory, not face criminal charges for prescribing medication abortion pills or performing abortion procedures. But physicians here in Green Bay, and others interviewed in Madison, said they — and the litigation-averse hospitals they work for — are requiring patients whose pregnancies are no longer viable, or who have gestational sacs that do not contain an embryo, to return for multiple ultrasounds, forcing them to carry nonviable pregnancies for weeks.

Before Wisconsin’s abortion ban, Igler would typically use the ultrasound machine in her office to detect when a patient’s pregnancy had ceased. She would break the news to expectant parents there. In some cases, a patient wanted further ultrasounds and she would refer them to the fetal-imaging department. It might help with their grieving, and “I was happy to do that for them,” Igler said.

But her bedside ultrasound can’t record and save the images that Igler would now need to prove that her medical judgment was reasonable during a criminal prosecution, so she is compelled to send all her patients for additional imaging.

“It seems cruel to show a woman her nonviable, dead baby and then say, ‘Well, now I have to bring you over to fetal imaging so we can record a picture and you have to see it again,’” she said.

In March, Rep. Ron Tusler, a Republican who represents a rural swath of Wisconsin south of Green Bay, posted on Facebook, “Thank God for the Dobbs decision!” In response, a local resident asked, “If my non-verbal, non-ambulatory 14-year-old daughter is assaulted, should she be forced to carry?”

The exchange escalated into a confrontation. “Is her health jeopardized?” Tusler asked. “Is she unable to leave the state? Can she provide consent?”

In the torrent of vitriol, certain moments stand out. Igler was incensed at the callous response and jumped in, writing: “Are you a monster, Ron Tusler? Do you know what compassion is? Come the next election, you will feel the backlash of your inhumane and outdated views. Get your hands off women’s bodies and out of the exam room. I’m an obstetrician. I’m the expert, not you.”

Tusler shot back that Igler was “angry she can’t kill babies until and occasionally after birth” and asked whether “I’m a monster for stopping her.” He wrote, “Honestly, how many babies have you aborted? How much money have you made from it? Did your hospital harvest the bodies for stem cells?”

The lunchtime rush at the restaurant in Green Bay had eased, and the women stared at the Facebook post on Igler’s phone.

She shook her head in baffled amusement. “This doesn’t even make sense,” she said. “It’s a conspiracy theory. I make so much more money if people actually have their babies. And if I don’t give out birth control, I would make a lot more money.”

Those sitting at the table laughed at the absurdity.

The salad bowls were empty. Everyone had told their own abortion stories. Igler was forced to travel to Colorado after her baby, at 25 weeks, was ravaged by a viral infection; Lyerly had lost a pregnancy at 17 weeks and did not want to endure the trauma of a vaginal birth.

Some 22 million women living today have had an abortion. It doesn’t take much effort to find a few of them.

Igler has found a community to grieve with other women in a Facebook group called “Ending a Wanted Pregnancy.” There are an untold number of other online groups.

“Politicians would like to believe we live in a perfect world where these things don’t happen,” she said.

The Wisconsin Legislature is one of the most gerrymandered in the country, according to Princeton University’s Gerrymandering Project. Republicans hold a majority in the state Senate and Assembly, and last month Senate Republicans voted unanimously to keep the 1849 abortion ban.

But a judicial alternative to restoring abortion rights has begun to unfold. In April, Janet Protasiewicz, an abortion rights supporter promoted by Democrats, won a seat on the Wisconsin Supreme Court, giving liberal justices a narrow majority and opening a path for a ruling on the legitimacy of the 1849 law. On July 7, a Circuit Court judge in Dane County, Diane Schlipper, appeared to doubt the validity of the pre-Civil War-era ban, allowing a lawsuit by Attorney General Josh Kaul, a Democrat, to proceed.

For now, Lyerly is driving across the border to work in rural Minnesota. “I want to practice medicine here,” she said, “but first we have to get rid of this law.”

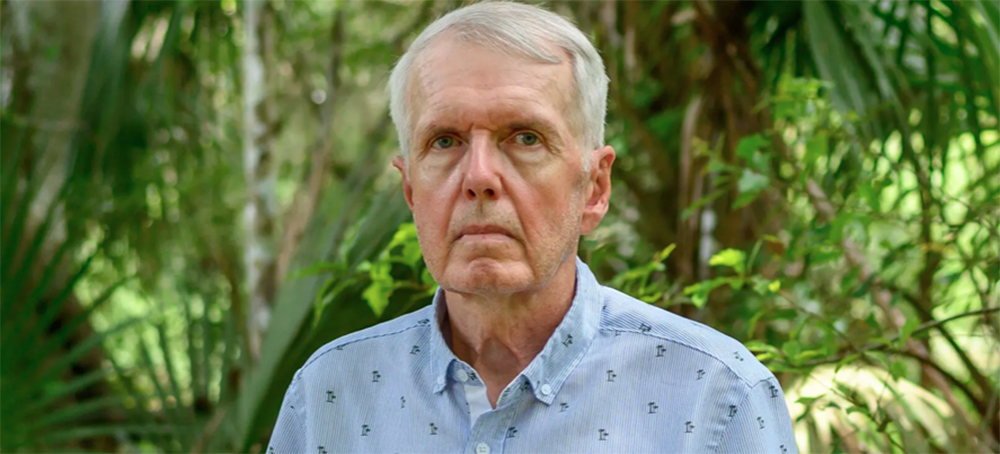

READ MORE  David Swisher is among the people suing Gilead. He took the company’s H.I.V. drug Truvada for 12 years and developed kidney disease and osteoporosis. (photo: Todd Anderson/NYT)

David Swisher is among the people suing Gilead. He took the company’s H.I.V. drug Truvada for 12 years and developed kidney disease and osteoporosis. (photo: Todd Anderson/NYT)

Gilead delayed a new version of a drug, allowing it to extend the patent life of a blockbuster line of medications, internal documents show.

In private, though, something else was at play. Gilead had devised a plan to delay the new drug’s release to maximize profits, even though executives had reason to believe it might turn out to be safer for patients, according to a trove of internal documents made public in litigation against the company.

Gilead, one of the world’s largest drugmakers, appeared to be embracing a well-worn industry tactic: gaming the U.S. patent system to protect lucrative monopolies on best-selling drugs.

At the time, Gilead already had a pair of blockbuster H.I.V. treatments, both of which were underpinned by a version of a drug called tenofovir. The first of those treatments was set to lose patent protection in 2017, at which point competitors would be free to introduce cheaper alternatives.

The promising drug, then in the early stages of testing, was an updated version of tenofovir. Gilead executives knew it had the potential to be less toxic to patients’ kidneys and bones than the earlier iteration, according to internal memos unearthed by lawyers who are suing Gilead on behalf of patients.

Despite those possible benefits, executives concluded that the new version risked competing with the company’s existing, patent-protected formulation. If they delayed the new product’s release until shortly before the existing patents expired, the company could substantially increase the period of time in which at least one of its H.I.V. treatments remained protected by patents.

The “patent extension strategy,” as the Gilead documents repeatedly called it, would allow the company to keep prices high for its tenofovir-based drugs. Gilead could switch patients to its new drug just before cheap generics hit the market. By putting tenofovir on a path to remain a moneymaking juggernaut for decades, the strategy was potentially worth billions of dollars.

Gilead ended up introducing a version of the new treatment in 2015, nearly a decade after it might have become available if the company had not paused development in 2004. Its patents now extend until at least 2031.

The delayed release of the new treatment is now the subject of state and federal lawsuits in which some 26,000 patients who took Gilead’s older H.I.V. drugs claim that the company unnecessarily exposed them to kidney and bone problems.

In court filings, Gilead’s lawyers said that the allegations were meritless. They denied that the company halted the drug’s development to increase profits. They cited a 2004 internal memo that estimated Gilead could increase its revenue by $1 billion over six years if it released the new version in 2008.

“Had Gilead been motivated by profit alone, as plaintiffs contend, the logical decision would have been to expedite” the new version’s development, the lawyers wrote.

Gilead’s top lawyer, Deborah Telman, said in a statement that the company’s “research and development decisions have always been, and continue to be, guided by our focus on delivering safe and effective medicines for the people who prescribe and use them.”

Today, a generation of expensive Gilead drugs containing the new iteration of tenofovir account for half of the market for H.I.V. treatment and prevention, according to IQVIA, an industry data provider. One widely used product, Descovy, has a sticker price of $26,000 annually. Generic versions of its predecessor, Truvada, whose patents have expired, now cost less than $400 a year.

If Gilead had moved ahead with its development of the updated iteration of the drug back in 2004, its patents either would have expired by now or would soon do so.

“We should all take a step back and ask: How did we allow this to happen?” said James Krellenstein, a longtime AIDS activist who has advised lawyers suing Gilead. He added, “This is what happens when a company intentionally delays the development of an H.I.V. drug for monopolistic purposes.”

Gilead’s apparent maneuver with tenofovir is so common in the pharmaceutical industry that it has a name: product hopping. Companies ride out their monopoly on a medication and then, shortly before the arrival of generic competition, they switch — or “hop” — patients over to a more recently patented version of the drug to prolong the monopoly.

The drugmaker Merck, for example, is developing a version of its blockbuster cancer drug Keytruda that can be injected under the skin and is likely to extend the company’s revenue streams for years after the infused version of the drug faces its first competition from other companies in 2028. (Julie Cunningham, a spokeswoman for Merck, denied that it is engaged in product hopping and said the new version is “a novel innovation aimed at providing a greater level of convenience for patients and their families.”)

Christopher Morten, an expert in pharmaceutical patent law at Columbia University, said the Gilead case shows how the U.S. patent system creates incentives for companies to decelerate innovation.

“There’s something profoundly wrong that happened here,” said Mr. Morten, who provides pro bono legal services to an H.I.V. advocacy group that in 2019 unsuccessfully challenged Gilead’s efforts to extend the life of its patents. “The patent system actually encouraged Gilead to delay the development and launch of a new product.”

David Swisher, who lives in Central Florida, is one of the plaintiffs suing Gilead in federal court. He took Truvada for 12 years, starting in 2004, and developed kidney disease and osteoporosis. Four years ago, when he was 62, he said, his doctor told him he had “the bones of a 90-year-old woman.”

It was not until 2016, when Descovy was finally on the market, that Mr. Swisher switched off Truvada, which he believed was harming him. By that time, he said, he had grown too sick to work and had retired from his job as an airline operations manager.

“I feel like that whole time was taken away from me,” he said.

First synthesized in the 1980s by researchers in what was then Czechoslovakia, tenofovir was the springboard for Gilead’s dominance in the market for treating and preventing H.I.V.

In 2001, the Food and Drug Administration for the first time approved a product containing Gilead’s first iteration of tenofovir. Four more would follow. The drugs prevent the replication of H.I.V., the virus that causes AIDS.

Those became game-changers in the fight against AIDS, credited with saving millions of lives worldwide. The drugs came to be used not only as a treatment but also as a prophylactic for those at risk of getting infected.

But a small percentage of patients who were taking the drug to treat H.I.V. developed kidney and bone problems. It proved especially risky when combined with booster drugs to enhance its effectiveness — a practice that was once common but has since fallen out of favor. The World Health Organization and the U.S. National Institutes of Health discourage the use of the original version of tenofovir in people with brittle bones or kidney disease.

The newer version doesn’t cause those problems, but it can cause weight gain and elevated cholesterol levels. For most people, experts say, the two tenofovir-based drugs — the first known as T.D.F., the second called T.A.F. — offer roughly equal risks and benefits.

The internal company records from the early 2000s show that Gilead executives at times wrestled with whether to rush the new formulation to market. At some points, the documents cast the two iterations of tenofovir as similar from a safety standpoint.

But other memos indicate that the company believed the updated formula was less toxic, based on studies in laboratories and on animals. Those studies showed that the newer formulation had two advantages that could reduce side effects. It was much better than the original at delivering tenofovir to its target cells, meaning that much less of it leaked into the bloodstream, where it could travel to kidneys and bones. And it could be given at a lower dose.

The new version “may translate into a better side effect profile and less drug-related toxicity,” read an internal memo in 2002.

That same year, the first human clinical trial of the newer version got underway. A Gilead employee mapped out a development timeline that would have brought the newer formulation to market in 2006.

But in 2003, Gilead executives began to sour on rushing it forward. They worried that doing so would “ultimately cannibalize” the growing market for the older version of tenofovir, according to minutes from an internal meeting. Gilead’s head of research at the time, Norbert Bischofberger, instructed company analysts to explore the new formulation’s potential as an intellectual property “extension strategy,” according to a colleague’s email.

That analysis resulted in a September 2003 memo that described how Gilead would develop the newer formulation to “replace” the original, with development “timed such that it is launched in 2015.” In a best-case scenario, company analysts calculated, their strategy would generate more than $1 billion in annual profits between 2018 and 2020.

Gilead moved to resurrect the newer formulation in 2010, putting it on track for its 2015 release. John Milligan, Gilead’s president and future chief executive, told investors that it would be a “kinder, gentler version” of tenofovir.

After winning regulatory approvals, the company embarked on a successful marketing campaign, aimed at doctors, that promoted its new iteration as safer for kidneys and bones than the original.

By 2021, according to Ipsos, a market research firm, nearly half a million H.I.V. patients in the United States were taking Gilead products containing the new version of tenofovir.

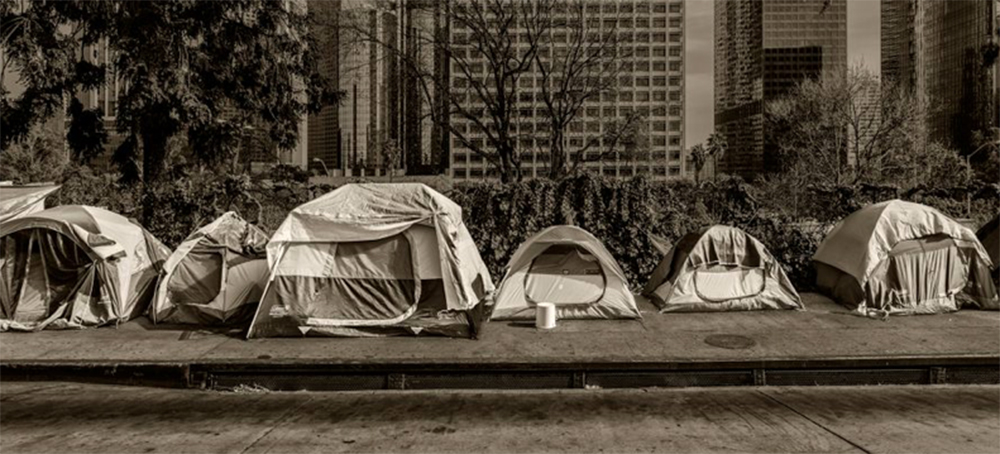

READ MORE  'California is home to Hollywood and Disneyland, sun and sand, and ... nearly one-third of all unhoused people in the entire nation.' (photo: In These Times)

'California is home to Hollywood and Disneyland, sun and sand, and ... nearly one-third of all unhoused people in the entire nation.' (photo: In These Times)

Our economic priorities have created a serious housing crisis and fueled homelessness. Solving the problem simply requires us to change our priorities from profits to people.

An extensive study of the state’s struggle with homelessness by the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) paints a detailed picture of the problem, and it’s not pretty. Homelessness is thriving at the intersections of racism, sexual violence, overpolicing, and more. The report’s authors explain, it “occurs in conjunction with structural conditions that produce and reproduce inequalities.”

Contrary to the popular perception that good weather fuels voluntary homelessness and consists largely of transplants from out of the state, the report points out that 90 percent of the unhoused had been living in California when they lost access to housing. And, three-quarters continue to remain in the same county.

The problem also manifests in systemic racism, with Black and Indigenous people overrepresented among the unhoused compared to their populations. More than a quarter of all unhoused people in California are Black, and yet only 6.5 percent of the state’s overall population is Black.

Homelessness also fuels sexual violence that disproportionately impacts unhoused LGBTQ people and women. More than one-third of transgender and nonbinary people currently experiencing homelessness reported being victims of sexual violence, while 16 percent of cisgender women did so as well.

And, nearly half of all the study’s participants (47 percent) report being harassed by police. Law enforcement routinely subjects California’s unhoused population to violent police raids, dehumanizing searches and seizures of property, forced relocation, and incarceration. The unhoused are disproportionately criminalized by a system that pours a significant amount of tax dollars into policing rather than into affordable housing. Increasingly, cities are simply making it illegal to live outdoors, as if criminalizing homelessness will magically make the math of housing affordability work out.

The UCSF report is neither the first, nor will it be the last one to explore the extent of homelessness in California. And while it makes clear how serious the problem is, the main question remains: how to solve it?

There are several policy solutions put forward including rental assistance in the form of housing vouchers, an exploration of shared housing models, mental health treatment, and even a progressive-sounding monthly income program. But these are merely metaphorical band-aids being applied to a gaping, bleeding wound. None of them address the fundamental reason of why there are more than 171,000 people without housing in California.

Interestingly, one of the UCSF study’s main authors, Dr. Margot Kushel, honed in on the core issue in an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle when she said, “We have got to bring housing costs down, and we’ve got to bring incomes up… We need to solve the fundamental problem — the rent is just too high.”

This is a nationwide problem and California is merely on the front lines.

So, how to bring housing costs down? The federal government sees a shortage of homes as the problem, treating it as an issue of supply and demand: increase the supply and the price will fall. But there is no shortage of housing in the nation. There is a shortage of affordable housing and as long as moneyed interests keep buying up housing, building more won’t be a fix.

Wall Street hedge funds see housing as the next frontier in profitable investing.

Since at least 2008, hedge funds have been buying up single-family homes and rental units in California, throwing a bottomless well of cash at a resource that individuals need for their survival and pushing house prices and rents out of reach for most ordinary people. This too is a nationwide phenomenon, one that was extensively outlined in a 2018 report produced by the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE), Americans for Financial Reform, and Public Advocates.

That report makes it clear that Wall Street hedge funds see housing as the next frontier in profitable investing. Once these funds buy up homes and apartments to rent out, they cut the labor and material costs associated with maintenance, and routinely raise the rents.

And why wouldn’t they? Their bottom line is profits, not safe, clean, fair, affordable housing. In 2000, the average American renter spent just over 24 percent of their income on housing. Today that percentage has jumped to 30. Hedge fund landlords are likely celebrating their success at getting “consumers” to fork over a larger share of money for their “products.”

The only way to stop hedge funds from taking over the housing market is… [drumroll] to stop hedge funds from buying up homes. To that end, the ACCE report calls on local municipalities and state governments to offer tenants the first right of refusal in purchasing homes, along with appropriate supports, and then offer nonprofit institutions like community land trusts to have the second right of refusal to purchase. It also calls on the federal government to “not incentivize speculation, or act to favor Wall Street ownership of housing assets over other ownership structures.”

The other end of the problem is that incomes are too low. According to Dean Baker at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, the federal minimum wage ought to be $21.50 an hour in order to keep up with the rise in productivity. But it’s not. It’s a horrifyingly low $7.25 an hour. And while a growing number of states are in the process of pushing that wage floor far higher to about $15 an hour, it doesn’t come close to what’s needed. Even the few dozen cities that have forced the minimum wage past their state requirements don’t get to $21.50 an hour.

Yes, individual incomes are rising because of worker demands on employers, but they are not keeping up with inflation. And even though government officials admit that rising wages don’t fuel inflation, the Federal Reserve sees rising wages as the problem, countering them with higher interest rates.

Putting together these pieces of the puzzle, one can only conclude that our economy is designed to keep ordinary Americans living hand to mouth, running on an endless treadmill just to keep from falling into homelessness.

The rent is too damn high — to cite affordable housing activists—and wages are too damn low. That is the nutshell description of an economy that is simply not intended to center human needs.

Passing laws to prevent hedge funds and other large businesses from buying up homes and apartments and raising the minimum wage to at least $21.50 are hardly radical ideas, but they offer course corrections for an economy that is running roughshod over most of us. Rather than tinkering at the edges of the problem and putting forward complex-sounding solutions that don’t actually address the root of the issue, wouldn’t society be better served by redesigning our economy to make homelessness obsolete?

READ MORE  'Thai politics could still change despite the best efforts of the military and the monarchy.' (photo: Lauren DeCicca/Vox)

'Thai politics could still change despite the best efforts of the military and the monarchy.' (photo: Lauren DeCicca/Vox)

Thai politics could still change despite the best efforts of the military and the monarchy.

The National Assembly also ousted Pita late Wednesday on recommendation of the Constitutional Court as it decides on the validity of his May candidacy in Thailand’s general elections. Pita had managed to build a multiparty parliamentary coalition, but failed to capture the necessary votes in an initial contest on July 13 though his party emerged as clear winners in Thailand’s general elections in May. Despite his coalition’s popularity — indicative particularly of young Thais’ frustration with a stalling economy and massive inequality — their ideas for a more open society threaten Thailand’s entrenched monarchy and military leadership.

Now, a rare opportunity for major reform is at risk; though Thai people have demonstrated their support for Move Forward and Pita after their recent setbacks, attending rallies and organizing protests, the deeply entrenched power of the monarchy and the military may prove too overwhelming for progressive civilian governance to break through.

Thailand has a history of political turmoil, resulting in several military coups, including the most recent in 2014, which deposed democratically-elected Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra. The present Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha took power in 2014 and is a former army general, as well as the nation’s defense minister. Though Thailand has vacillated between a parliamentary democracy and military autocracy throughout the decades, it is technically a constitutional monarchy.

The monarchy is in one sense a treasured part of Thailand’s national character, part of a centuries-long tradition. But under the present king, Maha Vajiralongkorn, Thailand’s government has experienced further democratic backsliding even as Thai people demand the opposite. Under Vajiralongkorn, the military and the monarchy make a powerful and often threatening combination; according to Human Rights Watch, the government arrested activists, suppressed pro-democracy protests, and instituted a nationwide state of emergency after massive and wide-ranging pro-democracy protests in 2020 and 2021. That protest movement was largely borne out of increasing government restrictions and demands to reform the monarchy.

For both Thais and outside observers, Pita’s campaign and his coalition’s win in May presented a real possibility for change and growth in southeast Asia’s second largest economy. Now, given the government’s multivalent efforts to suppress the Move Forward coalition, an opportunity for real change is starting to look like a repeat of history — a seemingly ineluctable cycle of hope, unrest, and crackdowns edging further toward autocracy.

“There’s a pattern here of establishment pushback against any progressive movement in Thai politics,” Thitinan Pongsudhirak, a political science professor at Chulalongkorn University told the New York Times. “And the pushback comes in different shapes and forms,”

Thailand’s constitutional monarchy is heavy on the monarchy

Thailand has been a constitutional monarchy since 1932, when a military coup abolished the absolute monarchy under King Prajadhipok. Despite that history, the Thai military establishment enjoys a close relationship with the monarchy — and they often work in concert to maintain a conservative and even autocratic government despite Thailand’s nominal embrace of democracy.

Prayuth and Vajiralongkorn have proven a formidable pair; during the 2020 and 2021 pro-democracy protests and calls to reform the monarchy, Prayuth’s government re-instituted punishment for lèse-majèste, or criticizing the monarchy. That policy, coupled with Covid-19 pandemic restrictions, enabled the government to detain and harshly punish thousands of pro-democracy protesters, according to Human Rights Watch.

Under Prayuth, the military government has also consolidated power and made it even more difficult for ordinary Thai citizens to participate in government and actually have a choice regarding the future of their government, as Vox’s Li Zhou explained in May:

The military has long had a hold on Thai politics, a grip only strengthened by military coups in 2006 and 2014. That latter coup was led by current Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha, who ushered in a new constitution that gave the military unprecedented power over government. One of those post-coup reforms threatens Move Forward’s coalition: 376 members of parliament are needed to elect a new prime minister, and the 250-person Senate was appointed by the military.

The military and monarchy hold significant sway over the political elite, including those who make up the Senate. That’s less pronounced in the democratically elected lower chamber, the House of Representatives, Brian Harding, senior expert on Southeast Asia and Pacific Islands at the US Institute for Peace told Vox in an interview. “If that were the only chamber, that in many ways reflects the will of the people,” he said.

But the Senate has been “in lock step” with the government and the monarchy, Anthony Nelson, vice president in the East Asia and Pacific practice at Albright Stonebridge Group, told Vox.

“The constitution is basically functioning as intended; it’s protecting the monarchy, it’s allowing the conservative, establishment Thai parties to have a major, major veto over what happens.”

Move Forward could still be pivotal to Thailand’s future

The democratic movement in Thailand is about much more than Pita, although he has emerged as its charismatic face. His leadership in Move Forward is actually somewhat of an outgrowth of the pro-democracy protests, youth movements, and efforts on the part of Thai civil society.

What is perhaps most salient about Pita is that he reflects the types of people who are drawn to Move Forward — young, well-educated, and progressive, people who ordinarily might be drawn to the traditional political elite, Nelson told Vox. That’s important for two reasons: It’s a departure from the country’s well-worn populist elected-to-military coup pipeline; and it’s an indicator that the newer generation is less socially stratified and more interested in building a forward-looking Thailand.

Economically speaking, Thailand’s government is highly conservative; the country is a regional powerhouse but has never really broken out of its middle income status, and there has been relatively little encouragement for domestic innovation.

Thailand’s economy is highly globalized; it is a friendly place for foreign investment, has a robust tourism industry, and is a part of the complex globalized supply chain. But there is a sense among Thai people, Nelson explained, that the fruits of the economy are largely concentrated at the very top.

That’s not unfounded; in 2018 Thailand’s Crown Property Bureau transferred about $40 billion in assets including land titles and stakes in domestic corporations over to Vajiralongkorn to be “administered and managed at His Majesty’s discretion,” as the Financial Times reported in 2020. Thais protested the move, calling for more government transparency and reforming the monarchy, in some ways setting off the current pro-democracy movement.

Thailand also lacks a robust social safety net, though the government did implement some social protection policies during the Covid-19 pandemic, including cash payouts for workers in the informal sector and relaxed loan repayments.

In addition to major political reforms like amending the lèse-majèste law and demanding more scrutiny of the defense apparatus, Move Forward offered a striking economic shift. The party proposed policies to build Thailand’s social safety net and raise wages “by raising taxes on corporations and on the wealthy, many of whom currently pay almost nothing in personal income tax,” Scott Christensen, an independent analyst, wrote in May for the Brookings Institution.

Thailand has “found itself in a middle-income rut,” Nelson said, due to vested economic interests and monopolies in several industries including telecoms and alcohol sales. Move Forward had vowed to tackle those monopolies to foment innovation and competition — a position Thitinan told Bloomberg would amount to “a complete transformation of the Thai economy.”

At this point there is almost no possibility that Pita will be Thailand’s next leader; the country’s Constitutional Court is hearing a case alleging that he was unqualified to run in May’s election because he owns shares in a media company, and the National Assembly has voted to prevent him from standing in the PM contest a second time.

However, Prayuth retired from politics July 11 following his party’s poor showing in the polls. Though he did not give a specific reason for his resignation, there is, potentially, at least some understanding that his government is deeply unpopular, as well as hope for a peaceful transition of power.

Furthermore Pheu Thai, Move Forward’s populist coalition partner, is set to field a candidate for a July 27 election. Though Pheu Thai is more conservative and will likely have to work with populist military-backed parties in parliament, that could actually push the National Assembly in a more progressive direction, Nelson said. And if Pheu Thai wins the premiership, that would actually represent a significant shift from Thailand’s current politics.

“It was not all that long ago that there was a military coup to break Pheu Thai’s influence,” he said, referring to the 2007 coup that removed Thaksin Shinawatra, the party’s founder, from power. “So if what ends up happening from this is that they come back into power anyway — who knows to what degree they’ll be able to exercise it — but they’ll certainly be able to do something.”

READ MORE The Western red cedar tree that could be cut down to make way for a housing project in Seattle. (photo: Manuel Valdes/AP)

The Western red cedar tree that could be cut down to make way for a housing project in Seattle. (photo: Manuel Valdes/AP)

Protest on private lot the latest episode highlighting tensions as climate crisis diminishes Seattle’s urban canopy

The protest on a private lot is the latest episode highlighting tensions behind tree policy in Seattle as the climate crisis increases temperatures and urban canopy decreases.

The western red cedar, dubbed “Luma” is about 80ft (24.4m) tall, with two trunks that are each about 4ft (1.2m) in diameter.

Its age is not known, but activists have estimated it could be as many as 200 years old. The Snoqualmie Indian Tribe is seeking to have the tree preserved for its archaeological significance, saying that Native Americans shaped its branches generations ago to distinguish it as a trail marker.

The protesters have declined to give their names, citing concerns about retaliation.

“We have to win this tree. We have to win because Luma is setting the tone for every other tree that’s under threat in Seattle,” one said from the tree. “We have to show that we mean business.”

The occupation began on 14 July, with each activist taking shifts of several days in the tree.

Some local residents hope to see it preserved.

“We were led to believe that this tree was was going to be kept,” said Andy Stewart, who lives down the block. “Then we got surprised to learn that the final permits were approved with the tree being removed.”

The tree is on a development site where a single family home is being replaced with six housing units split between two parcels. After the city surveyed the site and proposal, it decided that the tree needed to be removed to accommodate the new housing,

The initial plans neighbors cited didn’t accurately show the extent of the tree’s roots, said Bryan Stevens, a spokesman for the department of construction and inspections.

“The tree sits towards the middle of the parcel, making it difficult to preserve while also allowing for the development to achieve the number of housing units allowed on the property,” Stevens said.

Stevens said the city can’t revoke the removal permit.

The project is funded by Legacy Group Capital, which did not reply to an email from the Associated Press seeking comment.

The Snoqualmie Tribe this week sent a letter to the city asking officials to halt the removal. The city suggested the tribe reach out to state authorities to further assess if the tree is on an archeological site.

It’s unclear if the tree will be removed because new coordination between the landowner and the Washington department of archaeology and historic preservation is needed, Stevens said.

The department did not immediately respond to an email Friday.

Cities across the country have pledged to plant more trees to combat climate crisis and its impact. Trees not only absorb carbon dioxide but also cool cities. Researchers also say old trees need to be tended in cities because new plantings can take 10 to 20 years to start providing environmental benefits.

“Our majestic trees, for the most part, are our very largest native trees. And they are the most valuable in terms of keeping the community healthy and preserving our ecosystem,” said Sandy Shettler of the Last 6000, a group that aims to count and protect old trees.

Western red cedars can live up to 1,500 years in forests, according to the Washington department of natural resources.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.