Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Skeptics don’t understand why Kyiv insists on holding a city of modest strategic value.

But Ukraine does not have the luxury of choosing where it has to fight, precisely because it is preparing a counteroffensive. As it seeks to roll back the Russian forces that advanced farther into Ukrainian territory in last year’s Battle of the Donbas, Ukraine needs some time to master a wide variety of new equipment provided by its European allies and the United States, while simultaneously wearing down Russian troops and equipment.

Far from being needlessly destructive, the Ukrainian decision to fight for Bakhmut, Avdiivka, and Vuhledar—in what we are calling the Second Battle of the Donbas—has been, like most of the Ukrainian military’s decisions in this war, grounded in solid strategic understanding. The plan has been to use the benefits of being on the defensive to accumulate and train forces for the counteroffensive. Indeed, rather than harming any counteroffensive, the Ukrainian decision to prolong the fighting in these cities has more likely been integral to maximizing the chances of success.

The Ukrainian armed forces face an enemy with a quantitative advantage. The Russian army, particularly after the hastily prepared mobilization that started last September, had brought in a large number of new soldiers—albeit ones equipped, because of Russia’s earlier battlefield losses, with ever older and worse-maintained equipment than in earlier phases of the war. This expanded but flawed army needed time to train. Russia would have served its own interest better by allowing the new troops to develop their skills in protected defensive positions and by letting more experienced soldiers rest up in preparation for a Ukrainian attack. If Ukraine wants to get back the territory that Russia seized last year or in 2014, it will have to force the occupiers to retreat. And if the current war has made anything clear, it is that trying to advance against modern firepower is a dangerous job—as the Ukrainians themselves have demonstrated to Russian invaders many times in the current war.

Yet even after Russia’s 2022 campaign revealed major deficits in its forces’ leadership and effectiveness, Moscow’s military strategists seemed obsessed with the idea of taking the small communities now in contention in the Donbas. So Russia went back on the offensive without trying to fix its manifold problems. The Russian effort in Bakhmut was particularly intense because the community had become the target of the infamous Wagner Group, a private military company organized by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a onetime Kremlin caterer who is sometimes known as “Putin’s chef” and has become one of the pillars of his regime. The Russian army, meanwhile, set its eyes on Kupyansk, Lyman, Avdiivka, and Vuhledar and committed significant resources to their capture. In this way, the Russians unleashed a deadly competition within their own side, as the army and Wagner each seemed to go to greater and greater lengths to outdo each other for political purposes.

The fighting in Vuhledar produced one of the most extraordinary sights of the war. In early February, the Russians, desperate to take the town, ordered a column of tanks to advance single file down a road without demining equipment. The Ukrainians destroyed the whole column by scattering mines before and behind, leading to losses so catastrophic that the Russian commander was fired. Similarly, Russian formations failed to bypass and surround Avdiivka, failed to seize Kupyansk, made countless unsuccessful attempts to relieve Ukrainian pressure on Kreminna, and were unable to push Ukrainian formations back to Lyman (which Russia occupied before Ukraine liberated it in early October). Each of these failed operations cost the Russians dearly.

Bakhmut has been an even more grisly example of the Russian willingness to sacrifice soldiers. The Wagner Group has adopted a particularly perverse form of warfare. Raw, inexperienced troops of convicts are sent forward to attack Ukrainian lines with almost no hope of survival. Their role is only to be targets—to make the Ukrainians expose their own positions by opening fire. The apparent hope is that Russian artillery and subsequent assault waves can then advance past the bodies of their dead comrades. By applying these extremely costly “human waves” tactics, Wagner has been repeating a Red Army practice from World War II—one that today’s Western admirers of Soviet operational art typically don’t highlight.

However, even this form of self-destructive warfare has yielded only small territorial gains, and the losses of Russian soldiers, especially at Bakhmut, have been particularly shocking. A NATO official told The Guardian in late March that the Russians were suffering 1,200 to 1,500 casualties a day in the Second Battle of the Donbas, with most occurring in and around Bakhmut.

Ukraine has suffered real losses too. In December, when President Volodymyr Zelensky made his famous visit to Washington, one of the most emotional sections of his address to Congress dwelled on the fighting in Bakhmut. “Every inch of that land is soaked in blood; roaring guns sound every hour,” he said, adding, “The fight for Bakhmut will change the tragic story of our war for independence and of freedom.” In March, when Zelensky visited the Bakhmut front, he thanked soldiers for their heroic efforts while also stressing that the fight must continue until Ukraine wins. He has insisted that if Bakhmut falls, then Putin will smell weakness and use a Russian victory to muster international pressure against Ukrainian interests.

The Second Battle of the Donbas has exposed the terrible strategic choices that modern war forces upon combatants. Zelensky’s decision to prolong and play up the significance of the battle might seem callous, but it is part of a considered attempt to reduce Ukrainian losses in the future and prepare for the counteroffensive. Far better for Ukrainian forces to confront a large, unskilled Russian army when it is doing the attacking and exposing itself to great losses. If the Russian leadership keeps trying to press forward under these circumstances, the Ukrainians have to keep taking advantage.

READ MORE  Supporters of a military junta wave a Russian flag in the streets of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, on Oct. 2. (photo: Sophie Garcia/AP)

Supporters of a military junta wave a Russian flag in the streets of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, on Oct. 2. (photo: Sophie Garcia/AP)

The rapid expansion of Russia’s influence in Africa has been a source of growing alarm to U.S. intelligence and military officials, prompting a push over the past year to find ways to hit Wagner’s network of bases and business fronts with strikes, sanctions and cyber operations, according to the documents.

At a time when Wagner leader Yevgeniy Prigozhin has been preoccupied with Kremlin infighting over the paramilitary group’s deepening involvement in the war in Ukraine, U.S. officials depict Wagner’s expanding global footprint as a potential vulnerability.

One document in the trove lists nearly a dozen “kinetic” and other options that could be pursued as part of “coordinated U.S. and allied disruption efforts.” The files propose providing targeting information to help Ukraine forces kill Wagner commanders, and cite other allies’ willingness to take similar lethal measures against Wagner nodes in Africa.

And yet, there is little in the trove to suggest that the CIA, Pentagon or other agencies have caused more than minor setbacks for Wagner over a six-year stretch during which the mercenary group, controlled by Putin ally Prigozhin, gained strategic footholds in at least eight African countries, among 13 nations where Prigozhin has operated in some capacity, according to one document.

The only direct military strike mentioned in the files refers to “a successful unattributed attack in Libya” that “destroyed a Wagner logistics aircraft.” The document provides no further detail about the operation or why that single plane — part of a far larger Wagner fleet — was targeted.

The most significant American attack against Wagner was near Deir al-Zour, Syria, in February 2018, when U.S. airstrikes killed several hundred Wagner fighters who were attacking several dozen Delta Force soldiers, Rangers and Kurdish forces next to a gas plant.

Overall, the trove portrays Wagner as a relatively unconstrained force in Africa, expanding its presence and ambitions on that continent even as the war in Ukraine has become a grinding, if not all-consuming, problem for the Kremlin.

As a result, “Prigozhin likely will further entrench his network in multiple countries,” one of the intelligence documents concludes, “undermining each country’s ability to sever ties with his services and exposing neighboring states to his destabilizing activities.”

Wagner’s rise heralds a new surge of great power competition in Africa and with it a resurgence of authoritarianism, said Anas El Gomati, director of the Tripoli-based Sadeq Institute think tank.

Wagner, he said, “are a solution to the kind of problems that African dictators find themselves in: Democratic pushback? No problem. We’ll help you with that, whether it’s tampering with ballots, or whether it’s literally fighting brutal kind of insurgencies like they have in [the Central African Republic] and in southern Libya.”

“If you’re suffering trying to get your resources and minerals out of your country, ‘not only can we bring [those] services to you, but we’ll put those dollars in your bank and no one will be any the wiser’ — because they operate these massive networks of shell companies,” he said, referring to Wagner.

Prigozhin entities have not only accelerated operations in Africa over the past year, according to the assessments, but appear to be operating with expanded ambition and authority — “shifting his approach from taking advantage of security vacuums to intentionally facilitating instability,” according to one of the documents.

The description appears on a slide marked with symbols indicating that it was prepared for U.S. Army Gen. Mark A. Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and his senior advisers. A footnote summarizes Prigozhin’s “aggressive agenda,” citing plans to counter U.S. and French influence in Burkina Faso, Eritrea, Guinea, Mali and other countries, as well as Wagner’s direct support for a coup plot in Chad by setting up a cross-border training compound for rebels.

Chad has long been a linchpin of French and U.S. counterinsurgency operations against armed Islamist groups in the Sahel, and French President Emmanuel Macron signaled its importance when he attended Idriss Déby’s funeral in 2021.

One of the documents in the trove indicates that France “has communicated a willingness to strike Wagner if the [paramilitary organization] supports a coup in Chad.”

Prigozhin did not respond to a request for comment about the documents. Earlier, he told The Washington Post in response to questions about Chad that any suggestion that he had a role in destabilizing the transitional government there was “nonsense.”

Prigozhin claimed in comments on Telegram that his operations in Africa are “honest and fair,” designed only to “defend the African peoples, including those oppressed by bandits, terrorists, and unreliable neighbors.”

But in Libya, said El Gomati, Wagner’s intervention helped split and paralyze the country.

“They’re probably the most destabilizing actor now operating in Libya,” he said. “They often continue this kind of sub-threshold violence so whether you’re living in peace or war, you don’t feel any sense of stability.”

As if to underscore his expanding sense of self-importance, Prigozhin on Friday offered himself as a peace-broker in Sudan where fighting between rival factions have brought the East African country to the brink of civil war.

“To help resolve the existing conflict and for Sudan’s future prosperity, I am ready to mediate” a conflict between the head of the country’s army and the leader of a powerful private paramilitary, Prigozhin said in a statement published by his press office on the Telegram social media platform. He claimed to be ready to send planes with medical supplies and “everything needed for the people who are now suffering.”

Offering humanitarian intervention in a conflict he arguably inflamed — by previously supplying weapons and training to security forces — would be consistent with the Prigozhin playbook described in the trove of documents.

‘A particularly creepy Russian organization’

After the Cold War, when the Soviet Union and United States fueled proxy wars in Africa, Russia retreated from the continent, leaving China to forge in with offers of infrastructure and cheap loans, free of the usual Western pressure for progress on human rights or democratic institutions.

Russia’s return to Africa in recent years has revived a jostling competition for military and political influence that recalls the colonial scramble for African resources, a contest that one Equatorial Guinean official said indicated that Africa was like a “pretty girl” with “many suitors,” including the United States, according to the documents.

“There’s certainly a perception on the continent that following the end of the Cold War, the U.S. became less interested in the continent, only perceiving it as a place where it could engage in humanitarian activity, maybe apply some pressure for democratization, but not really engage in a meaningful way. And that opened up a gap for others,” said Murithi Mutiga, African program director at International Crisis Group.

Wagner is extracting resources in the Central African Republic (CAR), Libya and Sudan, according to one of the leaked documents. As well as a source of gold, uranium and other resources, the continent is a market for Russian weapons, nuclear power technology and security contracts. Russia leveraged its influence with Sudanese military leaders to agree on the completion of a naval base in Port Sudan by the end of 2023, according to the documents.

As Moscow intensifies diplomatic efforts to counter criticism of its war against Ukraine, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has visited multiple African countries this year, including Mali, Sudan, South Africa, Eswatini, Angola and Eritrea, all ahead of Putin’s July summit with African leaders in St. Petersburg.

In January, the State Department designated Wagner as a transnational criminal organization, with a pattern of “serious criminal behavior [that] includes violent harassment of journalists, aid workers, and members of minority groups and harassment, obstruction, and intimidation of U.N. peacekeepers in the Central African Republic, as well as rape and killings in Mali.”

CIA Director William J. Burns alluded to covert U.S. efforts to combat Wagner’s operations in public remarks at Georgetown University in February, describing Prigozhin’s group as “a particularly creepy Russian organization.”

He said that Wagner “is expanding its influence in … Mali and Burkina Faso and in other places, and that is a deeply unhealthy development and we’re working very hard to counter it because that’s threatening to Africans across the continent.”

Prigozhin — an ex-convict who rose to become an oligarch and close ally of Putin — offers security, military assistance, political advice, opinion polling, and political manipulation techniques to African leaders facing rebellions or instability, in return for resource contracts in regions that are too unstable to attract major Western companies.

“The Russians are very opportunistic and will just go in at very low cost and try to stir things up and see if they can create an advantage for themselves,” said Alex Vines, head of the Africa program at London-based think tank Chatham House. “There’s opportunistic mischief going on in various places.”

In CAR, Wagner forces helped the government drive out rebels who were threatening the capital in 2020, and provided security for President Faustin-Archange Touadéra, whose Russian security adviser, Vitaly Perfilov, is a Wagner employee, according to the State Department. Prigozhin’s entities are entrenched in mining, forestry and other activities there.

French newspaper Le Monde reported in February that U.S. officials offered Touadéra a deal on the sidelines of the U.S.-Africa summit in December to break with Wagner, in return for U.S. military training and increased humanitarian aid.

In response, Perfilov proposed an anti-American disinformation campaign in CAR media and social media, according to the documents, claiming that Washington bribed government ministers and attempted to plunder CAR’s mineral resources.

Russia has taken advantage of former Soviet ties with African leaders, according to analysts, but it has also exploited the United States’ dwindling engagement in Africa, notably during the Trump presidency, as well as an anti-French backlash over its counterterrorism operation in the Sahel region, focused on Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger named Operation Barkhane.

France withdrew its forces from Mali in 2021, when Wagner mercenaries moved in, and in December withdrew its last forces from CAR, where some analysts say Wagner is engaged in state capture. In February, Burkina Faso ordered French troops to leave.

“Russia through troll factories and fake media has been kind of successful at poisoning views on France in Africa. It was already not good, but they’ve really been able to stir the pot, through trolling and so on,” Vines said. “The Sahel is a very worrying, deteriorating area: It’s the global hot spot for militant Islamic jihadism globally at the moment, not the Middle East. And so clearly Russia has seen an opportunity.”

He said Russian anti-French and anti-Western propaganda resonated with African leaders, angered by French missteps in the Sahel, and weary of Western leaders pressing them on democratic values and human rights.

To elites in Africa, the United States is perceived as “still focused on the old playbook of lectures about democratization and sending humanitarian aid” while Washington’s democratic institutions have lost some of their sheen, Mutiga said.

“America may have taken a reputational knock in terms of the health of its democracy in recent years, but not just because of Trump, but because of congressional gridlock and chaotic politics and of course Trump’s rejection of the election results.”

Meanwhile, some analysts say, U.S. investment in Africa pales in comparison to China’s vast program of infrastructure and loans, while Russia is seen as offering more choices to African leaders who do not want to pick sides between Washington, Beijing and Moscow.

READ MORE  The geography of gun violence is the result of differences at once regional, cultural and historical. (photo: Sam Upshaw/Louisville Courier Journal/AP)

The geography of gun violence is the result of differences at once regional, cultural and historical. (photo: Sam Upshaw/Louisville Courier Journal/AP)

America’s regions are poles apart when it comes to gun deaths and the cultural and ideological forces that drive them.

In October, Florida’s Republican governor Ron DeSantis proclaimed crime in New York City was “out of control” and blamed it on George Soros. Another Sunshine State politico, former president Donald Trump, offered his native city up as a Democrat-run dystopia, one of those places “where the middle class used to flock to live the American dream are now war zones, literal war zones.” In May 2022, hours after 19 children were murdered at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott swatted back suggestions that the state could save lives by implementing tougher gun laws by proclaiming “Chicago and L.A. and New York disprove that thesis.”

In reality, the region the Big Apple comprises most of is far and away the safest part of the U.S. mainland when it comes to gun violence, while the regions Florida and Texas belong to have per capita firearm death rates (homicides and suicides) three to four times higher than New York’s. On a regional basis it’s the southern swath of the country — in cities and rural areas alike — where the rate of deadly gun violence is most acute, regions where Republicans have dominated state governments for decades.

If you grew up in the coal mining region of eastern Pennsylvania your chance of dying of a gunshot is about half that if you grew up in the coalfields of West Virginia, three hundred miles to the southwest. Someone living in the most rural counties of South Carolina is more than three times as likely to be killed by gunshot than someone living in the equally rural counties of New York’s Adirondacks or the impoverished rural counties facing Mexico across the lower reaches of the Rio Grande.

The reasons for these disparities go beyond modern policy differences and extend back to events that predate not only the American party system but the advent of shotguns, revolvers, ammunition cartridges, breach-loaded rifles and the American republic itself. The geography of gun violence — and public and elite ideas about how it should be addressed — is the result of differences at once regional, cultural and historical. Once you understand how the country was colonized — and by whom — a number of insights into the problem are revealed.

To do so you need to more accurately delineate America’s regional cultures. Forget the U.S. Census divisions, which arbitrarily divide the country into a Northeast, Midwest, South and West using often meaningless state boundaries and a willful ignorance of history. The reason the U.S. has strong regional differences is because our swath of the North American continent was settled by rival colonial projects that had very little in common, often despised one another and spread without regard for today’s state boundaries.

Those colonial projects — Puritan-controlled New England, the Dutch-settled area around what is now New York City; the Quaker-founded Delaware Valley; the Scots-Irish-led upland backcountry of the Appalachians; the West Indies-style slave society in the Deep South; the Spanish project in the southwest and so on — had different ethnographic, religious, economic and ideological characteristics. They were rivals and sometimes enemies, with even the British ones lining up on opposite sides of conflicts like the English Civil War in the 1640s. They settled much of the eastern half and southwestern third of what is now the U.S. in mutually exclusive settlement bands before significant third party in-migration picked up steam in the 1840s.

In the process they laid down the institutions, symbols, cultural norms and ideas about freedom, honor and violence that later arrivals would encounter and, by and large, assimilate into. Some states lie entirely or almost entirely within one of these regional cultures, others are split between them, propelling constant and profound disagreements on politics and policy alike in places like Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, California and Oregon. Places you might not think have much in common, southwestern Pennsylvania and the Texas Hill Country, for instance, are actually at the beginning and end of well documented settlement streams; in their case, one dominated by generations of Scots-Irish and lowland Scots settlers moving to the early 18th century Pennsylvania frontier and later down the Great Wagon Road to settle the upland parts of Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Tennessee, and then into the Ozarks, North and central Texas, and southern Oklahoma. Similar colonization movements link Maine and Minnesota, Charleston and Houston, Pennsylvania Dutch Country and central Iowa.

I unpacked this story in detail in my 2011 book American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, and you can read a summary here. But, in brief, the contemporary U.S. is divided between nine large regions — with populations ranging from 13 to 63 million — and four small enclaves of regional cultures whose centers of gravity lie outside the U.S. For space and clarity, I’m going to set aside the enclaves — parts of the regions I call New France, Spanish Caribbean, First Nation, and Greater Polynesia — but they were included in the research project I’m about to share with you.

Understanding how these historical forces affect policy issues — from gun control to Covid-19 responses — can provide important insights into how to craft interventions that might make us all safer and happier. Building coalitions for gun reform at both the state and federal level would benefit from regionally tailored messaging that acknowledged traditions and attitudes around guns and the appropriate use of deadly violence are much deeper than mere party allegiance. “A famous Scot once said ‘let me make the songs of a nation, and I care not who makes its laws,’ because culture is extremely powerful,” says Carl T. Bogus of Roger Williams University School of Law, who is a second amendment scholar. “Culture drives politics, law and policy. It is amazingly durable, and you have to take it into account.”

In the book American Nations I argued that there has never been one America but rather several Americas, most of them developing from one or another of the rival colonial projects that formed on the eastern and southwestern rims of what is now the United States. These regional cultures – “nations,” if you will – had their own ethnographic, religious and political characteristics, distinct ideas about the balance between individual liberty and the common good and what the United States should become.

They’ve also profoundly affected the geography of gun violence and gun policy.

There is a more detailed summary here, but the nine large regions – with populations ranging from 13 and 63 million – are:

Yankeedom (pop. 55.8 million)

Founded by Puritans who sought to perfect earthly society through social engineering, individual denial for common good, and the assimilation of outsiders. The common good – ensured by popular government - took precedence over individual liberty when the two were in conflict.

New Netherland (pop. 18.8 million)

Dutch-founded and retains characteristics of 17th century Amsterdam: a global commercial trading culture, materialistic, multicultural and committed to tolerance and the freedom of inquiry and conscience.

Tidewater (pop. 12.6 million)

Founded by lesser sons of landed gentry seeking to recreate the semi-feudal manorial society of English countryside. Conservative with strong respect for authority and tradition, this culture is rapidly eroding because of its small physical size and the massive federal presence around D.C. and Hampton Roads.

Greater Appalachia (pop. 59 million)

Settlers overwhelmingly from war-ravaged Northern Ireland, Northern England and Scottish lowlands were deeply committed to personal sovereignty and intensely suspicious of external authority.

The Midlands (pop. 37.7 million)

Founded by English Quakers, who believed in humans’ inherent goodness and welcomed people of many nations and creeds. Pluralistic and organized around the middle class; ethnic and ideological purity never a priority; government seen as an unwelcome intrusion.

Deep South (pop. 43.5 million)

Established by English Barbadian slave lords who championed classical republicanism modeled on slave states of the ancient world, where democracy was the privilege of the few and subjugation and enslavement the natural lot of the many.

El Norte (pop. 33.3 million)

Borderlands of Spanish-American empire, so far from Mexico City and Madrid that it developed its own characteristics: independent, self-sufficient, adaptable and work-centered. Often sought to break away from Mexico to become independent buffer state, annexed into U.S. instead.

Left Coast (pop. 17.9 million)

Founded by New Englanders (who came by ship) and farmers, prospectors and fur traders from the lower Midwest (by wagon), it’s a fecund hybrid of Yankee utopianism and the Appalachian emphasis on self-expression and exploration.

Far West (pop. 28.7 million)

Extreme environment stopped eastern cultures in their path, so settlement largely controlled by distant corporations or federal government via deployment of railroads, dams, irrigation and mines; exploited as an internal colony, with lasting resentments.

I run Nationhood Lab, a project at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy, which uses this regional framework to analyze all manner of phenomena where regionalism plays a critical role in understanding what’s going on in America and how one might go about responding to it. We knew decades of scholarship showed there were large regional variations in levels of violence and gun violence and that the dominant values in those regions, encoded in the norms of the region over many generations, likely played a significant role. But nobody had run the data using a meaningful, historically based model of U.S. regions and their boundaries. Working with our data partners Motivf, we used data on homicides and suicides from the Centers for Disease Control for the period 2010 to 2020 and have just released a detailed analysis of what we found. (The CDC data are “smoothed per capita rates,” meaning the CDC has averaged counties with their immediate neighbors to protect victims’ privacy. The data allows us to reliably depict geographical patterns but doesn’t allow us to say the precise rate of a given county.) As expected, the disparities between the regions are stark, but even I was shocked at just how wide the differences were and also by some unexpected revelations.

The Deep South is the most deadly of the large regions at 15.6 per 100,000 residents followed by Greater Appalachia at 13.5. That’s triple and quadruple the rate of New Netherland — the most densely populated part of the continent — which has a rate of 3.8, which is comparable to that of Switzerland. Yankeedom is the next safest at 8.6, which is about half that of Deep South, and Left Coast follows closely behind at 9. El Norte, the Midlands, Tidewater and Far West fall in between.

For gun suicides, which is the most common method, the pattern is similar: New Netherland is the safest big region with a rate of just 1.4 deaths per 100,000, which makes it safer in this respect than Canada, Sweden or Switzerland. Yankeedom and Left Coast are also relatively safe, but Greater Appalachia surges to be the most dangerous with a rate nearly seven times higher than the Big Apple. The Far West becomes a danger zone too, with a rate just slightly better than its libertarian-minded Appalachian counterpart.

When you look at gun homicides alone, the Far West goes from being the second worst of the large regions for suicides to the third safest for homicides, a disparity not seen anyplace else, except to a much lesser degree in Greater Appalachia. New Netherland is once again the safest large region, with a gun homicide rate about a third that of the deadliest region, the Deep South.

We also compared the death rates for all these categories for just white Americans — the only ethno-racial group tracked by the CDC whose numbers were large enough to get accurate results across all regions. (For privacy reasons the agency suppresses county data with low numbers, which wreaks havoc on efforts to calculate rates for less numerous ethno-racial groups.) The pattern was essentially the same, except that Greater Appalachia became a hot spot for homicides.

The data did allow us to do a comparison of white and Black rates among people living in the 466 most urbanized U.S. counties, where 55 percent of all Americans live. In these “big city” counties there was a racial divergence in the regional pattern for homicides, with several regions that are among the safest in the analyses we’ve discussed so far — Yankeedom, Left Coast and the Midlands — becoming the most dangerous for African-Americans. Big urban counties in these regions have Black gun homicide rates that are 23 to 58 percent greater than the big urban counties in the Deep South, 13 to 35 percent greater than those in Greater Appalachia. Propelled by a handful of large metro hot spots — California’s Bay Area, Chicagoland, Detroit and Baltimore metro areas among them — this is the closest the data comes to endorsing Republican talking points on urban gun violence, though other large metros in those same regions have relatively low rates, including Boston, Hartford, Minneapolis, Seattle and Portland. New Netherland, however, remained the safest region for both white and Black Americans.

The data suppression issue prevented us from calculating the regional rates for just rural counties, but a glance at a map of the CDC’s smoothed county rates indicates rural Yankeedom, El Norte and the Midlands are very safe (even in terms of suicide), while rural areas of Greater Appalachia, Tidewater and (especially) Deep South are quite dangerous.

So what’s behind the stark contrasts between the regions?

In a classic 1993 study of the geographic gap in violence, the social psychologist Richard Nisbett of the University of Michigan, noted the regions initially “settled by sober Puritans, Quakers and Dutch farmer-artisans” — that is, Yankeedom, the Midlands and New Netherland — were organized around a yeoman agricultural economy that rewarded “quiet, cooperative citizenship, with each individual being capable of uniting for the common good.”

Much of the South, he wrote, was settled by “swashbuckling Cavaliers of noble or landed gentry status, who took their values . . . from the knightly, medieval standards of manly honor and virtue” (by which he meant Tidewater and the Deep South) or by Scots and Scots-Irish borderlanders (the Greater Appalachian colonists) who hailed from one of the most lawless parts of Europe and relied on “an economy based on herding,” where one’s wealth is tied up in livestock, which are far more vulnerable to theft than grain crops.

These southern cultures developed what anthropologists call a “culture of honor tradition” in which males treasure their honor and believed it can be diminished if an insult, slight or wrong were ignored. “In an honor culture you have to be vigilant about people impugning your reputation and part of that is to show that you can’t be pushed around,” says University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign psychologist Dov Cohen, who conducted a series of experiments with Nisbett demonstrating the persistence of these quick-to-insult characteristics in university students. White male students from the southern regions lashed out in anger at insults and slights that those from northern ones ignored or laughed off. “Arguments over pocket change or popsicles in these Southern cultures can result in people getting killed, but what’s at stake isn’t the popsicle, it’s personal honor.”

Pauline Grosjean, an economist at Australia’s University of New South Wales, has found strong statistical relationships between the presence of Scots-Irish settlers in the 1790 census and contemporary homicide rates, but only in Southern areas “where the institutional environment was weak” — which is the case in almost the entirety of Greater Appalachia. She further noted that in areas where Scots-Irish were dominant, settlers of other ethnic origins — Dutch, French and German — were also more violent, suggesting that they had acculturated to Appalachian norms. The effect was strongest for white offenders and persisted even when controlling for poverty, inequality, demographics and education.

In these same regions this aggressive proclivity is coupled with the violent legacy of having been slave societies. Before 1865, enslaved people were kept in check through the threat and application of violence including whippings, torture and often gruesome executions. For nearly a century thereafter, similar measures were used by the Ku Klux Klan, off-duty law enforcement and thousands of ordinary white citizens to enforce a racial caste system. The Monroe and Florence Work Today project mapped every lynching and deadly race riot in the U.S. between 1848 and 1964 and found over 90 percent of the incidents occurred in those three regions or El Norte, where Deep Southern “Anglos” enforced a caste system on the region’s Hispanic majority. In places with a legacy of lynching — which is only now starting to pass out of living memory — University at Albany sociologist Steven Messner and two colleagues found a significant increase of one type of homicide for their 1986-1995 study period, the argument-related killing of Blacks by whites, that isn’t explained by other factors.

Those regions — plus Tidewater and the Far West — are also those where capital punishment is fully embraced. The states they control account for more than 95 percent of the 1,597 executions in the United States since 1976. And they’ve also most enthusiastically embraced “stand-your-ground” laws, which waive a person’s obligation to try and retreat from a threatening situation before resorting to deadly force. Of the 30 states that have such laws, only two, New Hampshire and Michigan, are within Yankeedom, and only two others — Pennsylvania and Illinois — are controlled by a Yankee-Midlands majority. By contrast, every one of the Deep South or Greater Appalachia-dominated states has passed such a law, and almost all the other states with similar laws are in the Far West.

By contrast, the Yankee and Midland cultural legacies featured factors that dampened deadly violence by individuals. The Puritan founders of Yankeedom promoted self-doubt and self-restraint, and their Unitarian and Congregational spiritual descendants believed vengeance would not receive the approval of an all-knowing God (though there were plenty of loopholes permitting the mistreatment of indigenous people and others regarded as being outside the community.) This region was the center of the 19th-century death penalty reform movement, which began eliminating capital punishment for burglary, robbery, sodomy and other nonlethal crimes, and today none of the states it controls permit executions save New Hampshire, which hasn’t killed a person since 1939. The Midlands were founded by pacifist Quakers and attracted likeminded emigrants who set the cultural tone. “Mennonites, Amish, the Harmonists of Western Pennsylvania, the Moravians in Bethlehem and a lot of German Lutheran pietists came who were part of a tradition which sees violence as being completely incompatible with Christian fellowship,” says Joseph Slaughter, an assistant professor at Wesleyan University’s religion department who co-directs the school’s Center for the Study of Guns and Society.

In rural parts of Yankeedom — like the northwestern foothills of Maine where I grew up — gun ownership is widespread and hunting with them is a habit and passion many parents instill in their children in childhood. But fetishizing guns is not a part of that tradition. “In Upstate New York where I live there can be a defensive element to having firearms, but the way it’s engrained culturally is as a tool for hunting and other purposes,” says Jaclyn Schildkraut, executive director of the Rockefeller Institute of Government’s Regional Gun Violence Research Consortium, who formerly lived in Florida. “There are definitely different cultural connotations and purposes for firearms depending on your location in the country.”

If herding and frontier-like environments with weak institutions create more violent societies, why is the Far West so safe with regard to gun homicide and so dangerous for gun suicides? Carolyn Pepper, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Wyoming, is one of the foremost experts on the region’s suicide problem. She says here too the root causes appear to be historical and cultural.

“If your economic development is based on boom-and-bust industries like mineral extraction and mining, people come and go and don’t put down ties,” she notes. “And there’s lower religiosity in most of the region, so that isn’t there to foster social ties or perhaps to provide a moral framework against suicide. Put that together and you have a climate of social isolation coupled with a culture of individualism and stoicism that leads to an inability to ask for help and a stigma against mental health treatment.”

Another association that can’t be dismissed: suicide rates in the region rise with altitude, even when you control for other factors, for reasons that are unclear. But while this pattern has been found in South Korea and Japan, Pepper notes, it doesn’t seem to exist in the Andes, Himalayas or the mountains of Australia, so it would appear unlikely to have a physiological explanation.

As for the Far West’s low gun homicide rate? “I don’t have data,” she says, “but firearms out here are seen as for recreation and defense, not for offense.”

You might wonder how these centuries-old settlement patterns could still be felt so clearly today, given the constant movement of people from one part of the country to another and waves of immigrants who did not arrive sharing the cultural mores of any of these regions. The answer is that these are the dominant cultures newcomers confronted, negotiated with and which their descendants grew up in, surrounded by institutions, laws, customs, symbols, and stories encoding the values of these would-be nations. On top of that, few of the immigrants arriving in the great and transformational late 19th and early 20th century went to the Deep South, Tidewater, or Greater Appalachia, which wound up increasing the differences between the regions on questions of American identity and belonging. And with more recent migration from one part of the country to another, social scientists have found the movers are more likely to share the political attitudes of their destination rather than their point of origin; as they do so they’re furthering what Bill Bishop called “the Big Sort,” whereby people are choosing to live among people who share their views. This also serves to increase the differences between the regions.

Gun policies, I argue, are downstream from culture, so it’s not surprising that the regions with the worst gun problems are the least supportive of restricting access to firearms. A 2011 Pew Research Center survey asked Americans what was more important, protecting gun ownership or controlling it. The Yankee states of New England went for gun control by a margin of 61 to 36, while those in the poll’s “southeast central” region — the Deep South states of Alabama and Mississippi and the Appalachian states of Tennessee and Kentucky — supported gun rights by exactly the same margin. Far Western states backed gun rights by a proportion of 59 to 38. After the Newtown school shooting in 2012, not only Connecticut but also neighboring New York and nearby New Jersey tightened gun laws. By contrast, after the recent shooting at a Nashville Christian school, Tennessee lawmakers ejected two of their (young black, male Democratic) colleagues for protesting for tighter gun controls on the chamber floor. Then the state senate passed a bill to shield gun dealers and manufacturers from lawsuits.

When I turned to New York-area criminologists and gun violence experts, I expected to be told the more restrictive gun policies in New York City and in New York and New Jersey largely explained why New Netherland is so remarkably safe compared to other U.S. regions, including Yankeedom and the Midlands. Instead, they pointed to regional culture.

“New York City is a very diverse place. We see people from different cultural and religious traditions every moment and we just know one another, so it’s harder for people to foment inter-group hatreds,” says Jeffrey Butts, director of the research and evaluation center at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Manhattan. “Policy has something to do with it, but policy mainly controls the ease to which people can get access to weapons. But after that you have culture, economics, demographics and everything else that influences what they do with those weapons.”

The old and new buildings of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in Washington. The Sackler donations to the institution are valued at over $31 million, about 4 percent of its overall endowment. (photo: Shuran Huang/NYT)

The old and new buildings of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in Washington. The Sackler donations to the institution are valued at over $31 million, about 4 percent of its overall endowment. (photo: Shuran Huang/NYT)

Even as the nation’s drug crisis mounted, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine continued to accept funds from some members of the Sackler family, including those involved with Purdue Pharma.

Yet officials with the National Academies have kept quiet about one thing: their decision to accept roughly $19 million in donations from members of the Sackler family, the owners of Purdue Pharma, the maker of the drug OxyContin that is notorious for fueling the opioid epidemic.

The opioid crisis has led to hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths, spawned lawsuits and forced other institutions to publicly distance themselves from Sackler money or to acknowledge potential conflicts of interest from ties to Purdue Pharma. The National Academies has largely avoided such scrutiny as it continues to advise the government on painkillers.

“I didn’t know they were taking private money,” Michael Von Korff, a prominent pain care researcher, said. “It sounds like insanity to take money from principals of drug companies and then do reports related to opioids. I am really shocked.”

Unlike the World Health Organization, which was accused of being manipulated by Purdue and later retracted two opioid policy reports, the National Academies has not conducted a public review to determine if the Sackler donations influenced its policymaking, despite issuing two major reports that influenced national opioid policy.

One of those reports, released in 2011 and now largely discredited, claimed that 100 million Americans suffered from chronic pain — an estimate that proved to be highly inflated. Still, it gave drugmakers another talking point for aggressive sales campaigns, primed doctors to prescribe opioids at an accelerating rate and influenced the Food and Drug Administration to approve at least one highly potent opioid.

Another problem arose in 2016, months after the National Academies received a $10 million Sackler family donation. The F.D.A. had tapped the institution to form a committee to issue new recommendations on opioids. But one senator took exception to some of the members selected by the Academies, complaining they had “substantial ties” to opioid makers, including Purdue. Before work began, four people were removed from the panel.

The National Academies is a nongovernmental institution, chartered by Abraham Lincoln in 1863, to serve as an independent adviser to the nation on science and medicine. Members of the Academies are elected each year — a career-capping honor for scientists and doctors.

In recent years, though, the advisory group has come under criticism for lapses over disclosing conflicts of interest in reports on biotechnology, genetically modified food and pharmaceutical pricing. Lisa Bero, chief scientist at the University of Colorado Center for Bioethics and Humanities, said the group’s longtime failure to disclose financial ties between committee members and industry placed the Academies in the “dark ages” of research integrity.

Accepting millions of dollars from the Sackler family while advising the federal government on pain policy “would be considered a conflict of interest under almost any conflict-of-interest policy I’ve ever seen,” Dr. Bero said.

Lawmakers and others have issued investigations into the business practices of members of the Sackler family and lavish spending by Purdue that amplified the voices of doctors and medical organizations wanting more opioid prescriptions despite soaring overdose deaths.

Yet aside from an article in a medical journal in 2019, the National Academies has not drawn public attention. After internal meetings, it quietly removed the Sackler name from the conferences and awards the family once helped sponsor.

Megan Lowry, a spokeswoman for the National Academies, said in a statement that the Sackler donations “were never used to support any advisory activities on the use of opioids or on efforts to counter the opioid crisis.” Ms. Lowry added that the organization had been prevented from returning the Sackler money because of legal restrictions and “donor unwillingness to accept returned funds.” The Academies declined to make senior officials available for interviews.

The Sackler donations emerged as an internal issue for the advisory group in 2019, when members of the governing council were briefed about the money. Sylvester Gates, known as Jim, a prominent Brown University physicist on the council, said members were “outraged” and wanted to ensure the funds did not influence the work of the Academies. But returning the money, Dr. Gates said, “was more complicated than the string theory I studied.”

The Lincoln Society

The National Academies receives 70 percent of its budget from federal funding, with the remainder from its endowment and private donors, including corporations that sell fossil fuels, chemicals and myriad prescription drugs.

Members of the Sackler family who were among the most heavily involved in running Purdue Pharma made their first donations to the National Academies in 2008, when Dr. Raymond Sackler, and his wife, Beverly Sackler, and the couple’s foundation, started contributing, according to Academy treasurer reports. Dr. and Ms. Sackler died in 2017 and 2019, respectively.

Daniel S. Connolly, a lawyer for the Raymond and Beverly Sackler branch of the family, said the couple gave $13.1 million, which differs slightly from the $14 million listed in the National Academies treasurer reports. The donations were intended to support the National Academy of Sciences “in ways that are clearly described publicly as having nothing at all to do with pain, medications or anything related to the company,” Mr. Connolly said.

The reports from the National Academies treasurer describe science-related events, prizes and studies supported by Raymond and Beverly Sackler.

Donations from Dame Jillian Sackler, whose husband, Arthur, died years before OxyContin arrived on the market, began in 2000 in amounts that by 2017 reached $5 million, reports show. Those donations funded a series of scientific meetings, the treasurer reports say.

The gifts qualified the Sackler donors for the institution’s Lincoln Society, consisting of top givers who enhance the Academies’ “impact as advisers to the nation,” according to the 2021 treasurer report. The Academies invested the funds, which grew to more than $31 million by the end of 2021, the most recent accounting available.

A Flawed Report

As the Sackler donations grew, a Purdue Pharma lobbyist was trying to make inroads with the Academies, according to records released in lawsuits against opioid makers. The Pain Care Forum, a group co-founded by Burt Rosen, the Purdue lobbyist, pushed for legislation introduced in 2007 and 2009 that included calling for a National Academies report to “increase the recognition of pain as a significant public health problem.”

Soon after the measure passed in a 2010 law, Mr. Rosen convened the Pain Care Forum at a 10 p.m. gathering to focus on “meetings with the Institute of Medicine,” the former name for the National Academy of Medicine, and for “membership on I.O.M. Committee.”

At the same time, the National Academies was forming the committee that would produce its 2011 opioids report, which included the estimate that about 100 million or 42 percent of American adults were in pain, a figure that other researchers later found to be significantly inflated. The report described chronic pain that limited function and cost the nation billions of dollars in lost salary and wages. Later estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defined chronic pain by different categories of severity, saying the condition affects 7 percent to 21 percent of Americans.

The report did not disclose any conflicts of interest for committee members nor did it disclose the Sackler funds. A spokeswoman for the National Academies said it did not release members’ conflict statements.

But among the panelists chosen, Dr. Richard Payne was president of the American Pain Society, a physicians group, in 2003 and 2004, which at the time drew more than $900,000 from Purdue. Dr. Payne died in 2019.

Another panelist, Myra Christopher, was swapping emails in 2007 with Purdue staff about “talking points” to respond to a news broadcast critical of opioids, records released in a Senate Finance Committee investigation in 2020 show.

At the time that the 2011 report was written, Ms. Christopher was president of the Center for Practical Bioethics, a nonprofit based in Kansas City, Mo. Purdue gave $934,770 to the organization that year. Asked about the funding, John Carney, a former chief executive at the center, sent an opinion article that stated the group’s donors did not dictate any of its work. Ms. Christopher declined to comment.

The 2011 report, which allowed pharmaceutical companies to argue that doctors should prescribe more opioids, came out even as the White House announced a very different message — that the nation was facing an opioid addiction crisis.

Soon after the National Academies report was issued, Dr. Andrew Kolodny, president of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, emailed the institution and asked whether it would disclose that Ms. Christopher’s organization had received funds from Purdue.

“No, sorry, can’t do that,” Clyde Behney, an official with the Academies, replied in an email in August 2011 reviewed by The New York Times. “Keep in mind that the report is done and released, so the future is more important than the past.”

Mr. Behney declined to comment. In a statement, the National Academies said it published an article in JAMA to explain how the committee arrived at the estimate that 100 million Americans were in pain. And the article, by Dr. Victor Dzau, president of the National Academy of Medicine, said that “conflict of interest is not an issue for the authors of the report,” who he said were carefully vetted. The JAMA article made no mention of Sackler family donations.

Dr. Dzau later wrote a letter to JAMA clarifying that he should have disclosed — in that article and others — conflicts of his own, including funds he received from Medtronic, which made a device to infuse pain medication.

The outsize pain figure was invoked routinely over the years — including in 2012 by Purdue’s own lawyers, who described the figure as evidence of pain that was “untreated or under-treated” in response to a Senate inquiry. Federal officials also highlighted the statistic. In 2014, Dr. Margaret Hamburg, the F.D.A. commissioner at the time, cited the figure of 100 million people “living with severe chronic pain” to explain why the agency approved a controversial and potent opioid called Zohydro.

Another Panel Questioned

By 2016, a new set of National Academies committee members would face scrutiny.

Opioid overdose deaths were soaring that year and would soon overtake car crashes as the leading cause of death in the United States. Dr. Robert Califf, then the acting commissioner of the F.D.A., was under pressure from Congress to do something.

He turned to the National Academies. Citing the 100 million people in pain, Dr. Califf and other top F.D.A. officials wrote in an article in The New England Journal of Medicine that the institution “brings an unbiased and highly respected perspective on these issues that can help us revise our framework.” (Dr. Califf was elected to be a member of the Academies later that year.)

Soon after, names were floated to sit on the committee, leading Senator Ron Wyden, a Democrat of Oregon, to raise concerns about “potential conflicts of interest and bias” in a letter to Dr. Dzau, the National Academy of Medicine president. One person’s work, funded by Purdue, used the term “pseudoaddiction” to downplay the lure of opioids, the senator noted.

The National Academies then replaced four panelists. The committee’s final report was widely respected and remains a key document for the F.D.A., which said it had consulted a variety of sources to address the drug crisis. Dr. Califf continues to rely on the report, which called for a “fundamental shift” in the nation’s approach to prescribing opioids.

Shannon Hatch, an agency spokeswoman, said that the F.D.A. was not aware that the Sackler family donated to the Academies and that the 2017 report speaks for itself.

Two members of the panel — Richard Bonnie, chairman of the committee and director of the University of Virginia Institute of Law, Psychiatry and Public Policy, and Dr. Aaron Kesselheim, a Harvard Medical School professor — said they were not aware of the Sackler family donations until asked about it by The Times. “I certainly didn’t feel any influence or pressure or expectations of what we would say from anyone at the National Academies,” Dr. Kesselheim said.

Two years after that report was released, The BMJ examined the potential conflicts of Dr. Dzau and of members of yet another Academies committee convened to examine opioid-prescribing guidelines.

Since then, the Justice Department announced an $8 billion civil and criminal settlement with Purdue Pharma and a civil settlement with members of the Sackler family. Those Sackler family members agreed to pay $225 million to resolve civil claims, and said they acted “ethically and lawfully.” Members of the family have not faced criminal charges.

A bankruptcy plan to reorganize Purdue and resolve thousands of opioid cases was challenged over the Sacklers’ proposed conditions and is under appellate review.

Purdue Pharma was asked by The Times to respond to a list of questions about its contacts with the Academies. But Michele Sharp, a Purdue spokeswoman, did not respond directly to any of those issues. Instead, she said the company was focused on its bankruptcy and settlement proceedings. “The settlement would deliver over $10 billion of value for opioid crisis abatement, overdose rescue medicines, and victim compensation,” she said.

Institutions that more publicly examined their use of Sackler donations include Tufts University, which released a review of possible conflicts of interest related to pain research education funded by Purdue Pharma. Concerns noted in the report included a senior Purdue executive’s delivering lectures to students each semester.

The World Health Organization in 2019 retracted two guidance documents on opioid policy after lawmakers aired concerns about ties to opioid makers, including a Purdue subsidiary, among report authors and funders.

Going forward, experts in nonprofit law said the National Academies was in the unusual position of having millions of dollars with no plans for their use.

Some universities, including Brown and Tufts, have dedicated their respective funds from the Sacklers to address the prevention or treatment of addiction.

Given the devastation of the opioid crisis, Michael West, senior vice president of the New York Council of Nonprofits, said that it would be worth the effort for the Academies to follow their lead.

“This would be a way,” he said, “of trying to make it right.”

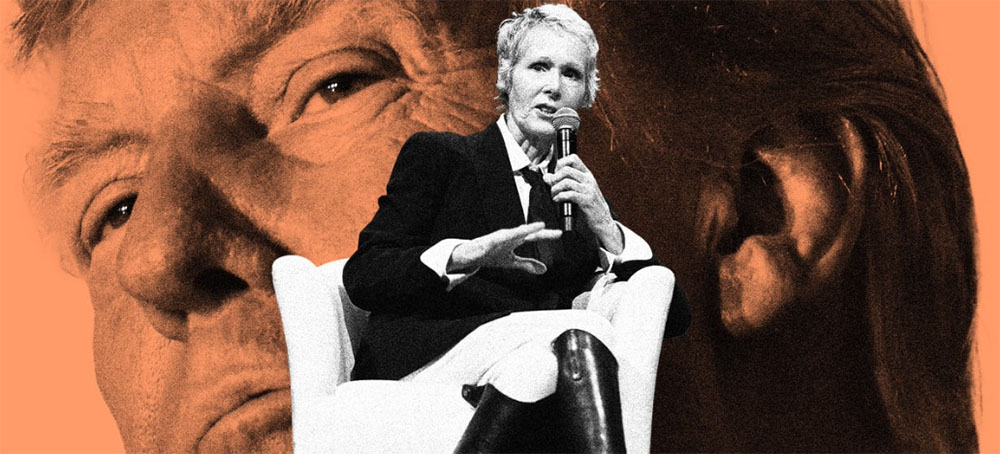

READ MORE  E. Jean Carroll. (photo: Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/Reuters)

E. Jean Carroll. (photo: Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/Reuters)

The long-time journalist accused the former president of raping her in the mid-1990s. Here’s what you need to know on the eve of the trial.

E. Jean Carroll, a journalist and author, has accused Donald Trump of raping her in a dressing room at the Bergdorf Goodman Department Store in Manhattan sometime between the fall of 1995 and spring of 1996. Trump has denied those allegations, contending at various times that he “did not know her” and she “was not his type.”

The case has been winding its way through the courts since 2019. The first complaint filed by Carroll contended that Trump had defamed her by falsely denying her accusation of rape. In 2022, Carroll filed a second complaint, which sought to hold him directly responsible for the rape. It is the rape case that is going to trial on Tuesday.

How Is A Case About An Alleged Rape in 1995-96 Getting To Trial Nearly 30 Years Later?

Generally, the statute of limitations for civil claims by adult survivors of sexual assault in New York is three years. However, in 2021, New York passed the Adult Survivors Act, which created a one-year window (from Nov. 24, 2022-Nov. 24, 2023) where the statute of limitations for civil claims of sexual assault was lifted.

On Nov. 24, 2022, Carroll filed her new case against Trump, alleging that he raped her (and defamed her when he denied that rape after leaving the White House). Trump moved to dismiss the case, contending that the Adult Survivors Act violated the Due Process Clause of the New York Constitution. Judge Lewis Kaplan denied the motion to dismiss, holding that the Adult Survivors Act was constitutional.

What Are The Best Facts For Carroll’s Case?

When Carroll’s legal team presents her case, the central part of the case will be her testimony that she was raped by Donald Trump in a dressing room in the lingerie section of Bergdorf Goodman.

A long-time reporter and television host, Carroll is used to public speaking and has repeated her account of the rape in numerous interviews over the last four years, in addition to her deposition in this case. Many people (not on the jury) have been persuaded that she is telling the truth.

But Carroll will be allowed to present more than her testimony that she was raped by Donald Trump.

Two witnesses—Carol Martin and Lisa Birnbach—will testify that Carroll told them of the rape shortly after it occurred, and that Carroll has had a consistent account of the rape for more than 25 years. Martin may be particularly persuasive to jurors over the age of 50. She was the first African-American female local news anchor in New York, hosting daily WCBS newscasts from the 1970s until 1994. Birnbach is the bestselling author of The Official Preppy Handbook and Lisa Birnbach’s College Book, which was required reading for NY-area college applicants.

Two other witnesses will testify that the former president sexually assaulted them: Jessica Leeds and Natasha Steynoff.

Leeds will testify that in 1979, she was seated next to Trump on a flight when he sexually assaulted her: “He was with his hands grabbing me, trying to kiss me, grabbing my breasts, pulling me towards him, pulling himself on me. It was kind of a struggle going on… It was when he started putting his hand up my skirt that I realized that nobody was going to save me but me.”

Steynoff will testify that during an interview with Trump for People magazine in 2005, he “grab[bed] my shoulders and pushe[d] me against this wall and start[ed] kissing me,” and that Trump later “groped” her. Former President Trump moved to have this testimony excluded from the trial, but Judge Kaplan held that under Federal Rule of Evidence 415, evidence of prior sexual assaults by the defendant is admissible in a subsequent civil trial for sexual assault.

In addition, Judge Kaplan held that Rule 415 permitted Carroll to introduce the infamous Access Hollywood interview against former President Trump. In that interview, Trump stated:

“You know, I’m automatically attracted to beautiful… I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. Just kiss. I don’t even wait. And when you’re a star they let you do it. You can do anything… Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything.”

Finally, Carroll will be able to present portions of Trump’s deposition, which was a disaster for him. Prior to his his deposition, Trump repeatedly insisted he wouldn’t have sex with Carroll because “she’s not my type.”

However, at his deposition, when Trump was shown a picture of Carroll from the mid-1990s and asked “Do you recognize her?”, he stated, “That’s my wife.”

Trump literally confused Carroll with his second wife, Marla Maples, to whom he was married for almost 10 years. He left his wife and mother of his first three children because he was so taken with Maples’ appearance. It is hard to imagine better proof that Carroll was Trump’s “type” than his deposition testimony confusing her with his wife.

What Are The Best Facts For Trump?

There are gaps in Carroll’s evidence. She does not remember the date, week, month, or year when the rape allegedly took place. She has not found any witnesses who corroborate seeing her with Trump at Bergdorf Goodman. There are no security photos or videos from the store showing the two of them together.

In addition, if Trump takes the witness stand, he will deny that he ever had sexual contact of any kind with Carroll. For some jurors, this evidence may be enough to rule in his favor.

Will There Be DNA Evidence?

No. At the start of the case, Carroll’s attorneys filed a portion of an expert report from a DNA expert, that analyzed stains on the dress that Carroll contends she was wearing when Trump allegedly raped her. Carroll’s legal team demanded that Trump allow their experts to extract DNA to compare to the dress. Trump’s attorneys refused, and Carroll’s legal team decided not to press the issue.

As trial approached, Trump’s lawyers made a high-profile demand for access to the rest of the DNA expert’s report. They stated that after they received the report, they would allow Carroll’s team to extract DNA from Trump. Carroll’s legal team declined that offer.

Judge Kaplan held that the Trump offer came far too late. Discovery had long been closed when Trump tried to get the DNA evidence into the case. Judge Kaplan held that Trump’s team was not allowed to second-guess their prior strategic choice. As a result, there will be no physical evidence that would prove (or disprove) Carroll’s claim that Trump ejaculated on her dress.

Will Trump Testify?

We still do not know whether Trump will testify (or even attend) trial. Carroll elected not to name Trump as witness, instead relying upon clips from the deposition. Trump’s lawyers listed him as a potential witness, but have not taken a position on whether he will actually testify.

If Trump testifies, he would face cross-examination, likely from Kaplan—a skilled questioner who elicited very damaging testimony from the former president during his deposition.

Could Trump Be Charged Criminally With Rape?

Yes, it is theoretically possible that former President Trump could be charged with rape, if the Manhattan DA concludes on the basis of the civil trial that there is a prosecutable criminal case. Under New York law, there is no statute of limitations for first degree rape.

When Carroll published her book, she made a formal complaint to the NYPD. Since that time, there is no evidence that the NYPD or the Manhattan DA’s office have taken steps to prosecute the case. It is unlikely that they would prosecute a criminal case unless something happens at the trial that drastically changes the situation.

It likely would take the equivalent of Jack Nicholson admitting on the witness stand that he ordered the Code Red at the end of A Few Good Men for DA Alvin Bragg to conclude that a criminal case should be pursued.

Will the Trial Be Televised, Photographed, or Livestreamed?

No. But the transcripts will be made available to reporters daily.

Conclusion

Ordinarily, at a civil trial, the only thing at issue is money. Here, the stakes are much higher. Depending on how this trial progresses, it may have a huge impact on the 2024 presidential election, the pending criminal investigations of former President Trump by prosecutors in Georgia and by the DOJ, and even the indictment for the Stormy Daniels payments. And it is hard to imagine a settlement of this case short of a verdict, but I suppose we will see.

READ MORE  Amelia Santos, 55, holds up a portrait of her late husband, Edward Navarte, during a recent performance. Santos says her husband was targeted in a 2016 extrajudicial killing by police as part of the Philippines' war on drugs. (photo: Ashley Westerman/NPR)

Amelia Santos, 55, holds up a portrait of her late husband, Edward Navarte, during a recent performance. Santos says her husband was targeted in a 2016 extrajudicial killing by police as part of the Philippines' war on drugs. (photo: Ashley Westerman/NPR)

Clutching a wireless microphone, the 55-year-old from Caloocan City, an area in Metro Manila's north, recalls the day she returned home from work in September 2016 and was told her husband, Edward Narvarte, had been killed.

"Somebody went to my house and told me, 'Go to your husband because he was killed, he was shot a lot of times by the police,'" she says. "When I arrived, there were police... and I saw the dead bodies of the victims, my husband was one of them."

Her family has not been the same, Santos tells the audience. Her children are scared and depressed and she is alone and afraid. Authorities linked her husband to a notorious Philippine drug lord, she says — a connection Santos denies.

With tears streaming down her face and her voice quivering with a mix of outrage and sadness, Santos recalls asking God, "Why? Why did this happen to us?"

"I will not stop until justice has been served," she says.

Santos is not alone. Almost all of the nearly 20 people onstage in this play, titled EJK Teatro, have lost a loved one to the Philippine government's so-called war on drugs — launched by former President Rodrigo Duterte in 2016.

EJK stands for extrajudicial killing. The play is part of the nonprofit Arnold Janssen Kalinga Foundation's Program Paghilom, which has been helping victims' families since 2016. Performing onstage is a sort of cathartic therapy for those who want to bring attention to critical issues in the Philippines. From inflation woes and environmental issues to the drug war and fears of a takeover by China, this eclectic performance — a nearly hour-long mix of scripted lines, unscripted monologues and lots of music and dancing — pulls no punches.

The day NPR attended, human rights campaigners, victims' family members and their supporters were joined in the audience by a delegation from the European Union, including EU Special Representative on Human Rights Eamon Gilmore.

The performance comes at a time when the slow wheels of justice appear to be starting to turn in the drug war.

Last month, the International Criminal Court denied an appeal by the Philippine government for the court to suspend collecting evidence for its investigation into alleged crimes against humanity committed during the seven-year war on drugs.

The denial of this appeal, analysts say, will inevitably bring government officials into the scope of the investigation — putting current President Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr. in a tough bind politically, as his vice president is Duterte's daughter and she is a political ally who helped him secure the nation's top office last May.

The denial came two months after the ICC declared that the Philippines' own investigation into the drug war — a tactic by Duterte to slow down the ICC investigation — was not sufficient and that the court would resume the probe it attempted to launch in 2021.

Philippine officials say that some 6,200 people have died in anti-drug operations since Duterte launched the war on drugs. Human rights groups and the United Nations estimate the number could be much higher, with most killed by police or vigilantes.

It is these extrajudicial killings that the ICC is looking to investigate, and now the ICC Office of the Prosecutor can move forward in collecting evidence while a second appeal to throw out the investigation entirely is pending, says Aurora Parong, co-chair of the Philippines Coalition for the International Criminal Court.

Evidence, she says, includes information such as interviews and testimony from victims' families. The court will also be able to start asking the government for information, "and after they have collected all that evidence, they should be able to identify a possible suspect who will be charged," she says.

Many human rights campaigners and legal experts say Duterte is the person responsible. However, obtaining evidence — such as communications between officials and police and testimony from officials — will be a challenge, given that President Marcos has said his government will not cooperate with the ICC.

"I do not see what their jurisdiction is," Marcos told reporters in January. "I feel we have our police, in our judiciary a good system. We do not need any assistance from any outside entity."

Analysts say this jurisdiction argument is faulty, because even though Duterte withdrew the Philippines from the ICC in 2018, the alleged human rights abuses of the drug war began earlier — so the ICC can still investigate them.

Still, Marcos has vowed to "disengage with the ICC" and has banned its investigators from entering the country.

This stance puts Marcos in a difficult spot politically as he works to both charm internationally and keep his own house in order, says Jean Encinas-Franco, a political scientist at the University of the Philippines Diliman.

Since taking office in May 2022, Marcos, the son of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, has traveled abroad in an attempt to secure economic and security agreements – which he hopes will rehabilitate his family name following his father's peaceful 1986 ouster in what's known as the "People Power Revolution."

But his stance on the ICC investigation "brings back the violent history of his father," Encinas-Franco says. That violent history included torture, extrajudicial killings and the targeting of political opponents, journalists and activists.

Domestically, Marcos knows he owes his presidential victory to his alliance with the Duterte family, she says — particularly Vice President Sara Duterte, daughter of the former president. Riding the coattails of her father's popularity, Duterte helped Marcos secure a landslide victory last year.

"I think Marcos Jr. would not want to antagonize Sara Duterte's supporters at this point in his administration," Encinas-Franco says.

Both Rodrigo Duterte and the anti-drug campaign as a policy are still popular — particularly among low-income voters. And it is these ordinary Filipinos that Marcos is probably banking on, Encinas-Franco says: "I think it would be very easy for him to sort of explain in simplistic terms that the ICC is encroaching on the Philippines' sovereignty."

But not all ordinary Filipinos will buy the sovereignty argument from Marcos — especially those who've been deeply affected by the war on drugs.

People like Amelia Santos, who has wrapped up her performance back at the auditorium. This was her first time onstage, she says.

"I wasn't able to express much after my husband died, to say everything that's inside," Santos says. "I am relieved."

Like other victims' loved ones, Santos is waiting to see what justice — if any — the ICC investigation brings.

READ MORE  Workers hired by BP rake up globs of oil on the beaches in southern Louisiana. (photo: Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

Workers hired by BP rake up globs of oil on the beaches in southern Louisiana. (photo: Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

Thousands have sued BP for health conditions they say come from cleaning up the Deepwater Horizon oil spill 13 years ago

The Guardian spoke with two dozen former workers, used computer programming to analyze a random sample of cases and combed through legal filings to understand the scope of the public health disaster.

BP declined to comment on detailed questions, citing ongoing litigation.

Here are some key findings:

Data analysis showed prevalence of health conditions among those who have sued

Among those who are sick there is a shared feeling of exasperation and anger as the chances of receiving damages and acknowledgement via the courts rapidly dwindles. They boated out into the Gulf to try to block the oil from coming ashore with floating barriers, called booms. They worked 12-hour shifts in the middle of the summer to save the wetlands and say they got sick as a result.

The Guardian used computer programming to analyze a random sample of 400 lawsuits out of the nearly 5,000 filed against BP. Many of the people in our sample have more than one ailment. Sinus issues are the most common chronic health problem listed among those who have sued, followed by eye, skin and respiratory ailments. Chronic rhinosinusitis, a swelling of the sinuses in the nose and head that causes nasal drip and pain in the face, was the most common condition. Two per cent have been diagnosed with cancer, a number some experts believe will continue to rise.

BP did not collect evidence that lawyers say could have shown if workers were exposed to toxins

Federal agencies encouraged BP to take urine, blood or skin swab samples of cleanup workers to detect whether toxins had entered their bloodstream. Instead, the fossil fuel firm depended on air monitoring to determine if workers were safe. Internal emails, gleaned from discovery in the lawsuits and reported on for the first time by the Guardian, show that was not BP’s only goal.

In a chain of emails among BP’s occupational hygiene team from 31 July 2010, the company discussed why it was continuing its air monitoring efforts. “Although we are documenting zero exposures in most monitoring efforts, the monitoring itself adds value in the eyes of public perception, and zeros add value in defending potential litigation,” wrote John Fink, a BP industrial hygienist.

Lawyers say this shows BP was already preparing its legal defense in the immediate aftermath of the spill.

BP is accused of using ‘scorched earth tactics’