Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

How to fortify yourself

It has been quite a year. Some of the regressive forces undermining our democracy, polluting our planet, widening inequality, and stoking hatred have been pushed back. This is a worthy accomplishment and cause for celebration. It offers hope that the Trump years are behind us and the hard work of building a decent society can resume.

But this is no time for complacency. No one should assume that the battle has been won. The anti-democracy movement is still fulminating. Trump is still dangerous. Corporate malfeasance continues. The climate catastrophe is worsening. Inequality is widening. Reproductive rights have been dealt a major setback. The haters and bigots have not retreated.

These regressive forces have many weapons at their disposal — lobbyists, money to bribe lawmakers, giant media megaphones, the most rightwing Supreme Court since the 1930s, a GOP that has lost all moral bearings and, starting soon, a Republican-controlled House of Representatives.

But their most powerful weapon is cynicism. They’re betting that if they can get most of us to feel like we can’t make a difference, we’ll stop fighting. Then they can declare total victory.

We must keep up the fight.

Here’s the thing to keep in mind. Notwithstanding setbacks, we are better today than we were fifty years ago, twenty years ago, even a year ago.

We’ve strengthened labor rights and LGBTQ rights. Most Americans are intent on strengthening women’s rights and civil rights. Most also want to extend Medicare for all, affordable childcare, paid sick leave, and end corporate monopolies and corporate dominance of our politics. We have clean water laws and clean air laws. We’ve torn down Confederate statues and expanded clean energy.

And we’ve got a new generation of progressive politicians, labor leaders, and community organizers determined to make the nation and the world more democratic, more sustainable, more just.

They know that the strongest bulwark against authoritarianism is a society in which people have a fair chance to get ahead. The fights for democracy, social justice, and a sustainable planet are intertwined.

The battle is likely to become even more intense this coming year and the following. But the outcome will not be determined by force, fear, or violence. It will be based on commitment, tenacity, and unvarnished truth.

It is even a battle for the way we tell the story of America. Some want to go back to a simplistic and inaccurate narrative where we were basically perfect from our founding, where we don’t need to tell the unpleasant truths about slavery, racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, and all the other injustices.

But there is another story of America, one of imperfection but progress. In this story, which is far more accurate, reformers have changed this nation many, many times for the better.

From Martin Luther King, Jr. to Ruth Bader Ginsberg to, more recently, Stacey Abrams, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Chris Smalls (who led the victory of Amazon’s Staten Island warehouse workers), Jaz Brisack (who led Starbucks workers), and Maxwell Alejandro Frost (the first Gen-Z elected to Congress), and many others — individuals have repeatedly changed the course of history by refusing to believe that they could not stand up to repression, bigotry, and injustice.

You don’t have to be famous to be an agent of positive change. You don’t have to hold formal office to be a leader. Change happens when selfless individuals, some of whose names we will never know, give their energies and risk their livelihoods (and sometimes their lives) to make the world more humane.

Small actions and victories lead to bigger ones, and the improbable becomes possible.

Look, I know: The struggle can be exhausting. No one can go all in, all the time. That’s why we need to build communities and movements for action, where people give what effort they can, and are buoyed in solidarity with others.

That’s what we’re doing in a small way in this forum. Building community. Sharing information and analyses. Fortifying our commitment.

The reason I write this newsletter is not just to inform (and occasionally amuse) you, but also to arm you with the truth — about how the system works and doesn’t, where power is located and where it’s lacking, and the myths and lies used by those who are blocking positive social change — so you can fight more effectively for the common good.

Here’s my deal. I’ll continue to give you the facts and arguments, even sprinkle in drawings and videos. I’ll do whatever I can to help strengthen your understanding and resolve, and give you the information you need.

In return, please use the facts, arguments, drawings and videos to continue the fight. To fight harder. And enlist others. (And, if you can, support this effort with a paid or gift subscription.)

If at any time you feel helpless or despairing, remind yourself that the fight for democracy, social justice, and a sustainable planet is noble. The stakes could not be higher. And we will — and must — win.

Wishing you a good 2023.

READ MORE  U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents search for an undocumented immigrant at his mother's house. (photo: Irfan Khan/LA Times/TNS)

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents search for an undocumented immigrant at his mother's house. (photo: Irfan Khan/LA Times/TNS)

During fiscal year 2022, a 12-month span between Oct. 2021 and Sept. 30, 2022, ICE deportation agents carried out 142,750 immigration arrests and 72,177 deportations, increases of 93% and 22%, respectively, compared to the previous fiscal year.

While the number of deportations in fiscal year 2022 is the second-lowest tally recorded by ICE, it represents a notable increase from 2021, when arrests and deportations by the agency plunged due to the coronavirus pandemic's impact on operations and new Biden administration policies that narrowed the population of deportable immigrants agents were instructed to prioritize for deportation.

Those rules, which prioritized the arrest of immigrants convicted of serious crimes, those deemed to pose a national security threat and migrants who recently entered the U.S. illegally, were struck down in federal court in June due a lawsuit by Republican-led states. The Supreme Court is set to decide in 2023 whether the Biden administration can reinstate the policies.

Founded in 2003, ICE's immigration enforcement division is charged with monitoring, arresting, detaining and deporting immigrants who are deportable under U.S. law, including those convicted of certain crimes and migrants transferred by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officials along the U.S.-Mexico border.

The increase in ICE arrests and deportations in 2022 was mostly a result of the unprecedented levels of unauthorized crossings recorded along the U.S.-Mexico border over the past year, the statistics published Friday show.

In fiscal year 2022, U.S. officials along the southern border reported a record 2.3 million migrant interceptions. Over 1 million of those detentions led to migrants being expelled to Mexico or their home country under a pandemic-related measure known as Title 42, according to federal data.

More than 96,000, or 67%, of the arrests ICE carried out in fiscal year 2022 involved immigrants without criminal convictions or charges, compared to 39% in 2021, a shift the agency attributed to the large number of migrants and asylum-seekers it received from border authorities. Nearly 44,000, or 61%, of the migrants deported in fiscal year 2022 were initially processed by U.S. border officials, Friday's report said.

Over the past year, 1,000 of ICE's 6,000 deportation officers were assigned to process and transport migrants arriving along the U.S.-Mexico border. The agency also carried out 117,213 expulsions of migrants processed under the Title 42 border restrictions. Because those expulsions were carried out under a public health law, they were not counted in ICE's formal deportation tally.

The average number of immigrants held in ICE's network of county jails and for-profit prisons increased slightly to 26,000, also driven by transfers of migrants from the U.S.-Mexico border. Moreover, ICE's caseload of immigrants awaiting a decision on their deportation cases outside of detention facilities grew to over 4.7 million cases — a 29% increase from 2021.

Due to insufficient levels of resources and personnel, however, ICE was only closely monitoring 321,000 immigrants in deportation proceedings at the end of fiscal year 2022 through its alternatives to detention program, which uses facial recognition technology, phone calls and GPS systems to track immigrants.

During a call with reporters on Friday, a senior ICE official who only agreed to answer questions anonymously said the agency would continue to help the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) respond to the "irregular mass migration that's occurring on the southwest border" in the coming year.

While the Biden administration's ICE enforcement priorities have been held up in court, agency officials said they are still prioritizing the arrest and deportation of certain categories of deportable immigrants.

"All law enforcement agencies have always allocated their resources to different priorities and different functions. We will continue to focus on national security and public safety threats, and we will continue to focus our efforts to those that undermine the integrity of the immigration process," the senior ICE official said.

Arrests and deportations of immigrants with criminal records remained at similar levels as 2021. ICE arrested 46,396 immigrants with criminal convictions or charges in fiscal year 2022, up from 45,432 in 2021. It also deported 44,096 immigrants with criminal convictions or charges, compared to 44,933 in 2021.

Among those deported in fiscal year 2022, ICE said, were 2,667 suspected or known gang members, 56 suspected or known terrorists and 7 human rights violators, whom the agency labeled as high-priority removals.

President Biden's administration moved to reshape ICE's practices soon after he took office in Jan. 2021, scrapping Trump-era rules that broadened the population subject to deportation and expanded immigration detention. The administration also tried to enact an 100-day moratorium on most deportations, but that effort was blocked in federal court.

While its rules to generally exempt unauthorized immigrants who have lived in the U.S. for years from arrest if they have clean records are currently held up in court, the Biden administration has issued other policies to limit the scope of ICE enforcement operations.

The administration has instructed the agency to discontinue mass work-site arrests and the long-term detention of families with minor children, and to refrain from arresting pregnant women, victims of serious crimes and military veterans.

Republican lawmakers have strongly criticized the changes at ICE, as well as the low number of interior deportations, accusing the Biden administration of not fully enforcing U.S. immigration laws amid record levels of migrant apprehensions along the U.S.-Mexico border.

But the Biden administration has argued its policies are designed to make the best use of ICE's limited resources by prioritizing the arrest of those deemed to pose the greatest threats to the country's national security, public safety and border security.

Beyond ICE's immigration branch, the agency also oversees Homeland Security Investigations, a law enforcement office that focuses on fighting transnational crime like migrant and drug smuggling, human trafficking and child exploitation.

In its report Friday, ICE said the work of its Homeland Security Investigations branch in fiscal year 2022 led to nearly 37,000 criminal arrests, more than 13,000 convictions, $5 billion in seized currency and assets and 9,382 weapon confiscations.

READ MORE  Gov. Kathy Hochul in her office at the New York State Capitol in Albany, N.Y. (photo: Cindy Schultz/NYT/Redux)

Gov. Kathy Hochul in her office at the New York State Capitol in Albany, N.Y. (photo: Cindy Schultz/NYT/Redux)

"Unacceptable": NY Progressives Vow to Stop Dem. Gov's Nomination of Conservative Judge to Top Court

Democracy Now!

Excerpt: "In a remarkable development, New York Democrats look likely to defeat Democratic Governor Kathy Hochul's nomination of Hector LaSalle to be the state's next chief judge, after progressives raised concern about his conservative judicial record and anti-abortion, anti-labor and anti-bail reform positions."

In a remarkable development, New York Democrats look likely to defeat Democratic Governor Kathy Hochul’s nomination of Hector LaSalle to be the state’s next chief judge, after progressives raised concern about his conservative judicial record and anti-abortion, anti-labor and anti-bail reform positions. “We have a situation here in New York where we have an opportunity to shift the highest court in a progressive direction, and the governor is completely fumbling that opportunity,” says Jabari Brisport, a Democratic Socialist state senator in Brooklyn who was one of the first to oppose LaSalle’s nomination.

On Wednesday, Democracy Now!'s Juan González and I spoke to one of the first state senators to oppose LaSalle's nomination, Jabari Brisport, New York state senator in Brooklyn who’s a Democratic Socialist. I asked him to describe how the governor chooses who to nominate for a chief justice, and why he opposes LaSalle.

SEN. JABARI BRISPORT: Well, good morning, Amy. Thank you for having me. It’s always a pleasure to be here.

The process in New York works like this. There is a Commission on Judicial Nominations. They take recommendations, applications over a several-week period, whenever they have an opening. And then they make a shortlist of seven that they give to the governor, who picks one to send to the Senate for confirmation. So, in the shortlist of seven, I would say there were three really outstanding candidates and three unacceptable ones. One, that being Hector LaSalle, who is unacceptable for the reasons you’ve listed previously, as making anti-labor decisions, anti-abortion decisions, and, honestly, branding as not even a conservative judge, but a conservative activist judge, going out of his way to make these decisions.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And could you be a little more specific on some of those decisions that he’s made that draw the ire and the concern of progressive groups?

SEN. JABARI BRISPORT: Yeah, sure. So, in his anti-abortion decision, there was a crisis pregnancy center in New York City that was misleading women seeking abortions and then went under investigation for illegally practicing medicine. And during their investigation, Hector LaSalle helped author a decision that shielded them from the full investigation by the attorney general. He basically made the case that they did not need to give or share what their marketing materials were, the things they were using to dupe women. He said that sharing those marketing materials would be a violation of their First Amendment rights somehow.

In terms of anti-labor decisions, there was a case where an employer, Cablevision, was suing union leaders. And even though that’s illegal in New York, Hector LaSalle went out of his way to say that even if the employer could not sue them as union leaders, he could sue them as individuals, basically exploding and rolling out the red carpet to a loophole to sue labor leaders. And that’s why five labor unions have also come out against Hector LaSalle, in addition to the 10 senators who have, as well.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: Now, in terms of his confirmation process, Democrats have an overwhelming majority in the state Senate. What would it take to block his confirmation?

SEN. JABARI BRISPORT: He would need 32 yes votes to be confirmed by the state Senate. So, currently, there are 10 of the 42 Democratic senators who have come out opposing him. If one single more is opposing him, then he will not have enough votes from the Democratic conference to be confirmed.

AMY GOODMAN: So, what’s going to happen now? And talk about — I mean, you know, it was a very close race between Lee Zeldin and Governor Hochul. One of their main differences was reproductive rights, was the issue of abortion. And, you know, he was fiercely anti-abortion, and she said she was extremely pro-choice. Can you talk about what that means when a chief justice has the position that he has, what kind of cases he presides over? And did this nomination surprise you?

SEN. JABARI BRISPORT: This nomination was baffling to me, that the governor would attempt to cement a conservative majority on our highest court up until 2030 with a judge who has a record of making anti-abortion decisions. And again, he has gone out of his way. When you have someone willfully misinterpreting the Constitution to the point where they’re saying an anti-abortion crisis pregnancy center does not need to share what, you know, lying, deceitful marketing materials they’re using, that’s a problem for me. And we have a situation here in New York where we have an opportunity to shift the highest court in a progressive direction, and the governor is completely fumbling that opportunity.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about bail reform, state Senator Brisport?

SEN. JABARI BRISPORT: Yes. In 2019, New York state enacted changes to the bail laws that allowed for more — less restrictive measures to allow more people to wait at home for their trial rather than waiting at our detention facility in New York City called Rikers in pretrial detention. And it was a strong success in terms of more equality of people staying at home and waiting home for their fair trial. But due to conservative backlash and blaming everything under the sun on the laws, it suffered rollbacks immediately after in 2020 and again this year, in 2022. And conservatives continue to weaponize it and lie about the facts of bail reform in order to get rollbacks and force more people to be incarcerated.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And what is your sense of why Governor Hochul took this decision, what kind of pressure she was under? After all, if she wanted to name the first Latino to chief justice, she could have named Jenny Rivera, who came out of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund and is already on the court, but she chose instead this far more conservative pick.

SEN. JABARI BRISPORT: Yeah, I would say two things, Juan. One is just the outspoken identity politics angle of confirming the first Latino. In terms of Jenny Rivera, she is fantastic; however, she was not on the seven-person shortlist provided by the Commission on Judicial Nominations, so she was not an option for the governor to choose.

And, you know, the unspoken one, aside from the identity politics, is that the governor consistently shies away from making bold progressive decisions. That’s also why she did so poorly against an election-denying, Trump-supported fascist running against her for the governorship just a few weeks ago, is that she refused to make — to distinguish herself with a strong progressive tack.

AMY GOODMAN: Hector LaSalle was a prosecutor in Suffolk County, New York. You tweeted, “It’s indefensible to ask for Black votes and then work to incarcerate us. No on LaSalle,” you said. Explain.

SEN. JABARI BRISPORT: There are zero judges with a defense background on the court. And that was a problem when we voted to confirm Madeline Singas over a year ago. I voted no on her. I voted no again on Troutman earlier this year. And we have an extremely lopsided fact that the Court of Appeals is dominated by prosecutors and people that issue, you know, pro-landlord decisions and pro-business decisions. And nominating yet another prosecutor to our highest court would maintain that imbalance.

AMY GOODMAN: Jabari Brisport, New York state senator in Brooklyn, a Democratic Socialist. We spoke to him Wednesday, before more Democrats said they would vote against the confirmation of Hector LaSalle, reaching 12, meaning he can’t be approved without Republican support, which makes it unlikely Democrats will bring his nomination to a vote, challenging the choice of the Democratic governor of New York, Kathy Hochul.

READ MORE  Execution chamber. (photo: California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation/Getty Images)

Execution chamber. (photo: California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation/Getty Images)

After a series of botched executions, the state is choosing a path of technical, rather than moral, innovation.

On July 28, Alabama executed Joe Nathan James Jr., a convicted murderer. And, for some reason—the precise cause remains a mystery because of the extreme degree of confidentiality the state guarantees its executioners—the execution team working that night botched their task badly, piercing James all over his body before evidently cutting into his arm, presumably in search of a visible vein in which to insert an IV catheter. They nevertheless managed to kill him, the results of their work clear in the early-August autopsy I witnessed. I left that experience convinced that Alabama’s next execution would also likely unfold against protocol.

With that in mind, I headed to Alabama again on September 22, the scheduled execution date of another man, Alan Eugene Miller. I was there that night when, after an hour or more of failed attempts, executioners exhausted their efforts at getting two needles into two of Miller’s veins, and state authorities called off his death.

Undaunted by their two consecutive failures in the execution chamber, Alabama promptly scheduled another death-row prisoner, Kenneth Smith, to die. I immediately made Smith’s acquaintance and agreed to attend his killing as well. On November 17, Alabama again tried and again failed to execute its man. Smith spoke with me later that night, once he was back in his cell, and told me how his would-be executioners had pierced his arms and hands and finally his neck underneath his collarbone before abandoning their efforts.

At that point, Alabama finally acknowledged what had been clear to me since early August: Inside the state’s execution chamber, there is a crisis deserving of investigative review. On November 21, Governor Kay Ivey ordered a temporary halt to executions so that the Alabama Department of Corrections could assess its execution methodology and personnel before moving forward. But this is not to say that Alabama is evolving; if notions of progress were distributed evenly among the states, this would be the point in the story where I would be able to report that this series of botched executions had caused Alabama’s leaders to consider abandoning the death penalty altogether. Instead, Alabama is choosing a path of technical, rather than moral, innovation.

The state appears to be preparing to premiere a new kind of execution by lethal gas. In the gas chambers of old, little cells were filled with poison that eventually destroyed the organs of the trapped prisoners, resulting in death. Now Alabama proposes to use nitrogen gas to replace enough oxygen to kill via hypoxia, an untested method once imagined in a National Review article and made manifest in a plastic gas mask.

Chief Justice Earl Warren made a certain presumption about the relationship between moral and technological progress, and that presumption shaped his interpretation of the Eighth Amendment, which bans cruel and unusual punishment. It went like this: As societies develop, their moral sensibilities tend to become more refined as well. Or, as Warren put it, writing in Trop v. Dulles, “The Amendment must draw its meaning from the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society.” In other words, Americans ought to aspire to more and more humane means of punishment, and the law ought to be understood as cooperative in that effort.

And yet, though several methods of execution have fallen into disfavor across history, the Supreme Court has never formally banned one, instead allowing states to choose from many archaic ways to kill prisoners. Lethal gas, for example, remains an artifact of the past and a specter of the future, both lethal injection’s inferior predecessor and its current statutory alternative in a small number of states—Alabama among them.

America’s executions with gas began roughly 100 years ago, at the outset of a century that would witness the industrial-level use of cyanide in Germany’s death camps. Scott Christianson’s book The Last Gasp: The Rise and Fall of the American Gas Chamber notes an inflection point in America’s experiment with gas in March of 1921, when Nevada Governor Emmet Boyle signed the Humane Execution Bill into law, requiring future executions to be carried out with lethal gas. The new law endeavored to replace older, uglier methods—hanging and electrocution—with a manner of dying that was promised to be painless and bloodless. Instead, on February 8, 1924, Nevada prison officials led the Chinese immigrant Gee Jon to a converted stone barber house that would be flooded with a gaseous form of hydrocyanic acid commercially known as cyanogen, a highly toxic substance used industrially to manufacture fertilizer and exterminate insects. Witnesses watched through the brick outbuilding’s window that morning as Gee gasped and convulsed amid the haze of lethal gas that filled the chamber. One military physician who observed the execution that day would later report that the death house’s heating had failed, causing the gas to partially liquefy rather than vaporize, then collect on the floor of the chamber where it remained in a deadly pool for hours after Gee’s death. That same physician would also later speculate that Gee, who had been poisoned on a frigid day at roughly 9:45 a.m. and who was not removed from his shackles until after noon, had likely died of cold and exposure.

Nevertheless, the execution was hailed as a coup for progress: Finally, after all of the bodies twisting on nooses and smoking under electrocution hoods, there was a scientific, humane execution method. Around the world, people took note: In Soviet Russia, Leon Trotsky was certain that America would soon turn its dastardly weapons on revolutionary Europe; in Germany, the news was met with great interest by researchers for the cyanide industry and budding fascists alike.

More than 600 people have died in American gas chambers since Nevada’s 1924 experiment. Remarkably, states used gas to execute prisoners even after the term gas chamber became synonymous with Nazi Germany. Though the chamber had promised instantaneous and painless death, the ugliness and risk of its application eventually made it the country’s shortest-lived method of execution, Deborah Denno, a professor at Fordham University School of Law, told me. In plain view of witnesses, prisoners died screaming, convulsing, groaning, and coughing, their hands clawing at their restraints and their eyes bulging and their skin turning cyanic.

The last of them, Walter LaGrand, was killed in Arizona in 1999. Despite the length of time separating his death from Gee’s, he endured a similarly troubled execution: LaGrand, a German-born American who was convicted of murder, gagged and hacked and then died over the course of 18 minutes. Knowing what prison authorities intended to do well before they strapped LaGrand into the black harness that would contain his body as he choked on poison gas, the government of then–German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder had tried diplomatic interventions to save the man’s life. The irony was lost on Arizona.

Alabama has something slightly different in mind. Nitrogen hypoxia is the dream of Stuart Creque, a technology consultant and filmmaker who, in 1995, proposed the method in an article for National Review, in which he speculated optimistically about the ease and comfort of gas-induced death. After hearing about the potential of nitrogen hypoxia as a lethal agent in a BBC documentary, Oklahoma State Representative Mike Christian brought the idea before Oklahoma’s legislature in 2014 as an alternative to lethal injection. Oklahoma passed a law permitting the use of nitrogen hypoxia as a backup method of execution in the event that lethal injections could no longer be carried out. Mississippi passed similar legislation in 2017; Alabama followed in 2018. With Missouri, California, Wyoming, and Arizona (which have older lethal-gas statutes still on the books), these three nitrogen-curious newcomers make up the handful of governments that could begin attempting to execute people with lethal gas at any time. (Alabama Department of Corrections did not immediately reply to a request to comment for this article.)

Alabama is by no means the ablest of these states, but it is among the more eager. Since the state’s governor announced an execution moratorium pending an investigation, Alabama’s attorney general, Steve Marshall, has been adamant that the killings will resume as soon as possible. “Let’s be clear,” Marshall recently said at a press conference he called to dispense his thoughts on the subject. “This needs to be expedited and done quickly, because we have victims’ families right now asking when we will be able to set that next date and I need to give them answers,” adding that “justice delayed is justice denied.”

Court papers provide clues about where Marshall’s insistence upon speedy executions translates into an interest in gas. Earlier this year, Marshall’s deputy attorney general, James Houts, brandished a gas mask during the deposition of Alan Eugene Miller, one of the men the state tried and failed to execute via lethal injection this fall, and asked Miller if he would be cooperative if prison officials attempted to fit the mask to his face or if he would be upset by the process. A witness to the event described the mask as a large plastic covering that would obscure most of the face, and which was to be locked in place by wide lime-green straps arrayed around the mask like the fixtures of a headlamp. Houts all but assured Miller’s attorneys and a district-court judge that Alabama would be prepared to execute Miller on September 22 of this year via nitrogen hypoxia, though he could not state directly and unequivocally that the state had actually finished developing its nitrogen-hypoxia execution protocol.

Unsurprisingly, Alabama officials weren’t ready, and thus they attempted to kill Miller this fall with the usual cocktail of lethal drugs piped in via needle. Still, their presentation with the gas mask during Miller’s proceedings demonstrated something useful about their approach: Unlike the gas houses of yesteryear, the state is evidently preparing to use a sealed mask attached to some source of nitrogen gas in order to induce hypoxia in a restrained prisoner. For this method of execution to kill successfully, the state will need access to the mask and its tubing, nitrogen gas or its precursors, a sealed chamber for the safety of bystanders, and a detailed plan.

Nitrogen is cheap and widely available, but also extremely dangerous. It has been used as a method of suicide and has killed people in industrial accidents. Deployed at a prison, it could pose a risk to staff in the event of leaks. Just last year, a liquid-nitrogen leak at a Georgia poultry facility resulted in six deaths and 11 hospitalizations. The Alabama Department of Corrections is aware of these risks: James Houts admitted during a court hearing in November that “the fact that there’s nitrogen gas stored in a certain place” presented “the dangers of inert-gas asphyxiation to employees.”

Houts added that the state had attempted to contract with a Tennessee-based firm to diagnose and improve their gas-execution system. But that firm terminated their contract with the state in February of this year after protests from local religious leaders, leaving the ADOC without an obvious alternative. This month, a spokesperson for Airgas, a national industrial-gas distributor that has done business with the ADOC in the past, told me over email that “notwithstanding the philosophical and intellectual debate of the death penalty itself, supplying nitrogen for the purpose of human execution is not consistent with our company values. Therefore, Airgas has not and will not supply Alabama nitrogen or other inert gasses to induce hypoxia for the purpose of human execution.” Airgas’s spokesperson added that the company’s contact in Alabama had been notified of this position upon my outreach. Few vendors, it appears, want to be directly involved with America’s return to the gas chamber.

Alabama will need a finished protocol taking all of the above into account before it is ready to execute the first American by nitrogen hypoxia. As of this fall, state officials seemed not to have one. It would take a certain audacity to be the first state to test an unknown means of execution immediately following three consecutive botched executions. But Alabama’s administrators are nothing if not audacious.

READ MORE  Romelia Navarro, right, is comforted by nurse Michele Younkin as she weeps while sitting at the bedside of her dying husband, Antonio, in St. Jude Medical Center's Covid-19 unit in Fullerton, California. (photo: Jae C. Hong/AP)

Romelia Navarro, right, is comforted by nurse Michele Younkin as she weeps while sitting at the bedside of her dying husband, Antonio, in St. Jude Medical Center's Covid-19 unit in Fullerton, California. (photo: Jae C. Hong/AP)

The true toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on many communities of color is worse than previously known.

If someone dies at home, if they have symptoms not typically associated with the disease or if they die when local health systems are overwhelmed, their death certificate might say “heart disease” or “natural causes” when COVID-19 is, in fact, at fault.

New research shows such inaccuracies also are more likely for Americans who are Black, Hispanic, Asian or Native.

The true toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on many communities of color – from Portland, Oregon, to Navajo Nation tribal lands in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, to sparsely populated rural Texas towns – is worse than previously known.

Incorrect death certificates add to the racial and ethnic health disparities exacerbated by the pandemic, which stem from long-entrenched barriers to medical care, employment, education, housing and other factors. Mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention point to COVID-19’s disastrous impacts, in a new analysis by the Documenting COVID-19 Project at Columbia University’s Brown Institute for Media Innovation and MuckRock, in collaboration with Boston University’s School of Global Public Health; the USA TODAY Network; the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting; Willamette Week in Portland; and the Texas Observer.

The data shows that deaths from causes the CDC and physicians routinely link to COVID – including heart disease, respiratory illnesses, diabetes and hypertension –have soared and remained high for certain racial and ethnic groups.

In Arizona's Navajo and Apache counties, which share territory with Navajo Nation, COVID deaths among Native Americans drove nation-leading excess death rates in 2020 and 2021. While COVID death rates among Natives dropped during the second year of the pandemic thanks to local health efforts, other causes of death such as car accidents and alcohol poisoning increased significantly from 2020 to 2021.

In Portland, deaths from causes indirectly related to the pandemic went up in 2021 even as official COVID deaths remained relatively constant. Black residents were disproportionately impacted by some of these causes, such as heart disease and overdose deaths – despite a county-wide commitment to addressing racism as a public health threat.

UNCOUNTED 2021: Inaccurate death certificates across U.S. hide COVID's true toll

In Texas, smaller, rural counties served by Justices of the Peace were more likely to report potential undercounting of COVID deaths than larger, urban counties served by medical examiners. Justices of the Peace receive limited training in filling out death certificates and often do not have sufficient access to postmortem COVID testing, local experts say.

Experts point to several reasons for increased inaccurate death certificates among non-white Americans. These include resources available for death investigations, the use of general or unknown causes on death certificates, and how the race and ethnicity fields of these certificates are filled out.

Such barriers to accurate death reporting add on to existing health disparities that made non-white Americans more susceptible to COVID in 2021, despite widespread vaccination campaigns and health equity efforts.

“Even if you try to level the playing field, from the jump, certain populations are dealing with things that put them at greater risk,” said Enrique Neblett, a health equity expert at the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health. These issues include higher exposure to COVID, as people of color are overrepresented among essential workers, as well as higher rates of chronic conditions that confer risk for severe disease. “Those things aren’t eliminated just by increasing access to a vaccine,” Neblett said.

It is critical to improve data collection and reporting for deaths beyond those officially labeled as COVID because data is a “major political determinant of health,” said Daniel Dawes, executive director of the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at the Morehouse School of Medicine. Information on how people are dying in a particular community can shape priorities for local public health departments and funding for health initiatives.

“If there is no data, there is no problem,” Dawes said.

Undercounting at the national level

Going beyond the deaths officially attributed to COVID provides a broader picture of the pandemic’s toll on marginalized communities. The U.S. system for investigating how people die is a patchy, uneven network of coroners and medical examiners, which have wildly different resources and training from state to state – or even from county to county.

As a result, researchers often use excess deaths, a measure of deaths that occur above what demographers expect to see in a given time period based on past trends, to examine the pandemic’s overall impact. Nationwide, more than 280,000 excess deaths since 2020 have not been attributed to COVID.

Coroners and medical examiners serving Black communities, in particular, have fewer resources for death investigations, according to an analysis by the Boston University School of Public Health, relying on survey data of death investigations by the Department of Justice. Counties with the highest shares of Black residents had the fewest full-time personnel to investigate each death, the researchers found.

These death investigation offices “may not have the capacity to treat all of these deaths equally,” compared to offices with more staff, said Rafeya Raquib, a research fellow who worked on the analysis.

Also, in the last two years, death investigators have relied more heavily on nonspecific or unknown causes of death for people of color. These causes, called “garbage codes” by researchers, are designed to be used as a last resort when an investigator is unable to determine how someone died.

Garbage codes were a “pretty big problem” before the pandemic, said Laura Dwyer-Lindgren, leader of the U.S. Health Disparities team at the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Past analyses going back to the 1990s have found these codes have historically been used more among non-white people.

These inaccurate codes “compromise our ability to say something definitive about a person’s cause of death,” Dwyer-Lindgren said. Garbage code deaths among non-Hispanic white people increased only 1% during the pandemic, compared to the prior two years; among Hispanic, Native, and Asian Americans, they increased by more than 20%.

The Boston University team found this trend was more pronounced among deaths that happened at home, where death investigators with less medical training are in charge.

“Our death investigation system structurally disadvantages communities of color by obscuring the causes of death in those communities, which hinders our policy response,” said Andrew Stokes, a professor in the Department of Global Health at the Boston University School of Public Health and leader of the research team.

Another potential source for undercounting: Race and ethnicity are not always correctly reported on death certificates, especially if the investigator filling out such a certificate is a different race than the person who died. These errors are particularly common for Native Americans, like Mary-Katherine McNatt, a public health expert at A.T. Still University whose research focuses on health disparities.

“Very rarely will someone look at me and say, ‘Oh, she's clearly American Indian,’” she said.

In Native American communities in Arizona, excess deaths remain high

Timian Godfrey, a Navajo assistant clinical professor of nursing at the University of Arizona, traveled to the Navajo Nation in early 2021 to help with its mass vaccination campaign.

The reservation – the largest in the country, with a population over 160,000 and shared territory with Arizona, New Mexico and Utah – was hit hard by COVID in spring 2020. Barriers to health care access and high rates of chronic diseases made the Diné community highly vulnerable; leaders responded with strict lockdowns and other safety measures. Getting vaccines into arms was the next phase of Navajo Nation’s response.

Godfrey said people waited in line for upward of four hours to get their vaccinations. “We heard so many devastating stories, but also the commitment of them knowing that this is what they could do for their family and to protect their loved ones,” she said.

Thanks to these efforts, Arizona’s Native American communities became “pockets of high vaccine areas,” McNatt said. The vaccinations contributed to a sharp decline in COVID deaths and overall excess deaths: In Navajo County, the COVID death rate for Native Americans almost halved between 2020 and 2021, according to analysis of CDC data. In Apache County, the rate dropped by 36%.

But neighboring white communities were more “hostile to masking” and vaccination, said Will Humble, executive director of the Arizona Public Health Association. As a result, white death rates in Navajo County rose by 3.5 times from 2020 to 2021, while white death rates in neighboring Apache County rose by more than five times.

Even as COVID death rates declined for Native Americans, excess deaths in Navajo and Apache counties remained high. In both 2020 and 2021, Apache County had the highest excess death rate of any U.S. county over 30,000 people, while Navajo County had the fourth-highest rate in 2020 and the second-highest rate in 2021.

Arizona counties with high percentages of Native American residents rank extremely high on the CDC’s social vulnerability index, said Dr. Daniel Derksen, director of the University of Arizona Center for Rural Health. “The populations that live in those rural counties tend to be quite vulnerable to things like natural disasters, things like pandemics,” he added, because of numerous factors included in the index calculation, including lack of access to care and populations that skew older.

Despite the vaccination success for this Native American community, legacies of racism and colonialism contributed to continued health problems in 2021, said Emerson, the UNC expert. He pointed to issues such as a lack of clean water and intergenerational households as sources of coronavirus spread in the region. Godfrey said that the high prevalence of chronic diseases in Native Americans, such as diabetes and kidney disease, which are dangerous comorbidities, are also a consequence of colonialism in the country.

In Portland, Black residents are disproportionately affected

For officials in Portland, the pandemic has revealed how much work lies ahead in order to truly address systemic health inequities. Since 2014, Multnomah County, which includes the state's most populous city, has received grant funding from the CDC for targeted programs aimed to improve public health among the county’s Black residents.

The pandemic worsened disparities and “made it harder” to do this work, said Charlene McGee, director of the program, called Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health.

Despite its high COVID vaccination rate – more than 80% of residents are fully vaccinated, according to CDC data – Multnomah County saw a stark increase in excess deaths from 2020 to 2021. These deaths were disproportionately located in communities of color, particularly Native American, Black and Pacific Islander communities.

Some of those excess deaths resulted directly from COVID. While the overall number of official deaths in Portland did not change significantly from 2020 to 2021, the distribution shifted: The rate of Black deaths more than doubled from 2020 to 2021. Death rates among other groups remained constant or dropped.

McGee connected the high Black death rate to a history of poor access to health care, as well as higher rates of chronic conditions such as diabetes, high blood pressure and hypertension. She also pointed to vaccine hesitancy in the Black community, tied to past and present negative interactions with the medical system.

“In 2022, we still hear about the Tuskegee study,” she said.

Beyond the official COVID deaths, deaths from other causes went up in the second year of the pandemic above what demographers estimated for Multnomah County. To researchers like the Boston University team, such an increase could indicate that some COVID deaths have been incorrectly reported.

The best “proxy measure” for incorrect reporting is the share of excess deaths that were assigned to COVID-19, Stokes said. In Multnomah County, less than half of excess deaths were officially labeled as COVID in 2021. This could indicate “potentially severe underreporting, which could be significant enough to skew decision-making by policymakers,” he said.

The Multnomah County Health Department acknowledged it doesn’t routinely analyze local death data or compare Multnomah to other counties.

Russell Barlow, an epidemiologist at the agency, pushed back against potential undercounting of COVID deaths. In later stages of the pandemic, he has seen more “incidental” cases in which a patient tested positive for COVID – but it’s unclear whether the virus actually contributed to their hospitalization or death, he said.

Such cases could potentially skew COVID-19 death rates in the opposite direction, though some experts say worries about these cases are overblown.

Limited bandwidth for analyzing death data has been a broader problem for Oregon’s public health system during the pandemic. Oregon has a statewide medical examiner’s office, but it relies on individual counties to investigate deaths that occur outside the health care system.

County programs to investigate deaths often “rely on part-time investigators with limited forensic training,” said a spokesperson for the Oregon State Police, which oversees the medical examiner’s office.

During the pandemic, these investigators saw more cases but did not receive a corresponding increase in resources. The state medical examiner’s office had 17 full-time staff as of summer 2022, with 8.5 positions “vacant pending recruitment.” While the office received a funding increase in Oregon’s latest legislative session, goals such as accreditation by the National Association of Medical Examiners are still far off.

Resource challenges likely contributed to an increase in deaths attributed to garbage codes – those ill-defined causes of death that investigators are supposed to use only after exhausting all other efforts to identify how someone died – in both Multnomah County and Oregon as a whole. In Multnomah County, the number of deaths attributed to these codes increased by 34% during the pandemic compared to the previous two years, while in Oregon as a whole, garbage code deaths increased by 35%.

Rural counties in Texas see tight budgets

Any pandemic strain felt by physicians and death investigators in urban areas like Portland was multiplied for rural counties with even fewer resources. This problem is particularly visible in Texas.

Texas has 254 counties, each of which has its own office for tracking deaths. In 15 counties with populations over 2 million, this is a formal medical examiner's office with trained staff. For example, Dallas County is served by the Dallas County Southwestern Institute of Forensic Sciences: this office had 71 full-time staff and a budget of nearly $16 million in 2018, according to the DOJ survey.

For the remaining 239 Texas counties, elected Justices of the Peace are responsible for investigating deaths. These JPs do not need any medical training to take on their jobs. In fact, the only training they receive for tracking down deaths outside medical settings is a two-hour course from a medical examiner, according to reporting by the Texas Observer.

This is far from the comprehensive education that should be required to fill out death certificates, said Rebecca Fischer, an epidemiologist at Texas A&M University. “It’s unfair to put this burden onto somebody without proper training,” she said.

Texans regularly received incorrect death certificates before the pandemic, but COVID has brought new light to this issue. For instance, early in the pandemic, JPs from Orange and Jefferson counties told local reporters they were not ordering COVID tests for people who had potentially died of the disease, even though such testing is recommended by the CDC.

In more than half of Texas’ rural counties, fewer excess deaths were officially attributed to COVID in 2021 than the state average, according to the analysis by Stokes’ team.

Several counties on or near the state’s border with Mexico, such as Zavala, assigned less than half of their excess deaths to COVID in 2021 – a clear signal of underreporting. Another border country, Presidio, also fits this pattern.

Sometimes, JPs may want to perform a COVID test or full autopsy to determine how someone died, but may feel constrained by the high costs of these tests, said Thea Whalen, the executive director of the Texas Justice Court Training Center, who organizes training for JPs.

“Everything is county budget-driven, in our state,” she said. “That can lead to judges, sometimes, feeling like they aren’t able to get what they need.”

Texas counties with higher-resourced medical examiners offices had more accurate reporting: Dallas County assigned 85% of its excess deaths to COVID in 2021. But even these offices may be “pretty overwhelmed” with many deaths to investigate, Whalen said.

JPs are primarily responsible for investigating deaths that occur at home or otherwise outside medical settings. These at-home deaths are more common in rural areas, Stokes said, in part because rural communities have less access to health care. Between 2005 and 2022, 183 rural hospitals have closed across the country, according to a study by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Of those 183 hospitals, 24 were in rural parts of Texas.

Fischer also pointed to political polarization around COVID as a potential driver of inaccurate death reporting in the state. Inaccurate reporting can further contribute to community perceptions of COVID risk, as part of what Stokes calls a “negative behavioral feedback loop.” If someone does not know people are dying from COVID in their community, they may be less likely to follow public safety measures – thus contributing to more spread of the virus.

“When the information pipeline is clogged by underreporting, we don’t know what our risk is,” Fischer said.

What can be done?

Despite the challenges that stand in the way of accurate death data for marginalized Americans, these patterns are not inevitable.

In mid-March 2020, officials in Matagorda County, Texas – a rural county along the Gulf Coast, served by a JP – identified the first COVID death in the state. The Texan, a man in his late 90s, died before he could be tested for the coronavirus, but his respiratory symptoms led the county’s small hospital to conduct posthumous testing for him and for his caregiver. This was a unique move, at a time that testing was widely inaccessible in rural areas.

Matagorda County’s JP office, aided by an attentive small county hospital staff, continued to conduct thorough death investigations throughout the pandemic. According to the Boston University analysis, this county had more official COVID deaths in 2021 than it did excess deaths, indicating a high accuracy of reporting.

This Texas county may serve as an example for future improvements in death reporting. When local offices are provided with resources and training to thoroughly investigate deaths, they are better equipped to do their jobs. Some experts have even suggested abolishing coroners entirely, and ensuring that every death investigator is a medical professional. A bill that would split the roles of sheriff and coroner in California is currently advancing through the state legislature.

“Every epidemiologist wants everybody to be tested for everything all the time,” Fischer said. Such exhaustive testing is likely impossible, she acknowledged, but more comprehensive training and better resources for death investigators could bring the U.S. closer to that ideal.

Only 17% of death investigation offices interviewed in the DOJ study were accredited by one of the two organizations that certifies this work, said Raquib, the Boston University researcher. “Providing guidelines for these offices, as well as making sure they’re accredited,” would improve death statistics.

Statewide medical examiners can also bring more standards to this process. The Documenting COVID-19 project’s past reporting with USA TODAY found that highly accurate COVID death reporting in New England states stems from such statewide offices, which are well-run and well-funded; high quality-hospitals in this region played a role as well. Federal agencies like the CDC have even more capacity to standardize the death system across the country, Stokes said.

Outside the death investigation system, disadvantaged communities require resources and structural changes to address long-standing inequities, experts say. Public health researchers like McNatt and Dawes currently must break through mistrust in the medical system when they seek to collect data, even though those data could be vital in addressing problems.

“Without the data, we cannot go in there as professionals and develop interventions to make (a) better quality of life,” McNatt said.

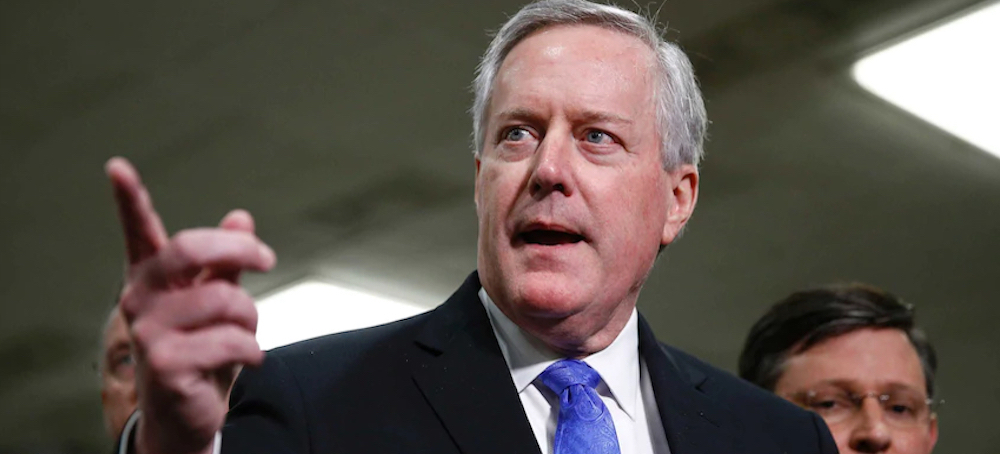

READ MORE  Mark Meadows. (photo: Patrick Semansky/AP)

Mark Meadows. (photo: Patrick Semansky/AP)

Meadows and his wife, Debra, were under investigation after media reports that the former North Carolina congressman’s voter registration listed a mobile home in Scaly Mountain, N.C., that he had never owned, stayed at or visited. But authorities were shown proof that Meadows and his wife leased the home, Debra did stay there for short periods, and there was no evidence the couple “knowingly swore to false information considering the signed lease,” said Attorney General Josh Stein (D).

Meadows is “explicitly excepted from certain residency requirements as a result of his service to the federal government,” Stein added.

“The State Bureau of Investigation conducted an extensive investigation into the fraud allegations against Mr. and Mrs. Meadows concerning their registration and voting in the 2020 elections,” Stein said in a statement. “After a thorough review, my office has concluded that there is not sufficient evidence to bring charges against either of them in this matter.”

Meadows’s spokesman, Ben Williamson, declined to comment about the prosecutorial decision.

In 2020, Meadows changed his registration after he sold his home in North Carolina’s 11th Congressional District, which he represented from 2013 until that year. From March 2020 to January 2021, Meadows served as Trump’s chief of staff. He had a condo in Virginia near Washington, but he did not own property in North Carolina.

Meadows cast an absentee ballot by mail in the battleground state for the November general election while his registration listed the mobile home as his residence. Trump won the state by 1.3 percentage points.

The New Yorker, which first reported on Meadows’s registered address, interviewed a previous property owner who said Meadows’s wife had rented the property for a short period and spent only one or two nights there during each visit.

According to a state Department of Justice memo about reasons for declining to charge in the case, the couple provided investigators with a signed year-long lease for the home that began on Sept. 1, 2020. Debra Meadows also shared cellphone logs for two days in October that showed her placing calls in the area.

Meadows was removed from North Carolina’s voter rolls while the fraud investigation was ongoing. North Carolina State Board of Elections spokesman Patrick Gannon said Meadows was removed “after documentation indicated he lived in Virginia and last voted in the 2021 election there.”

Although Stein said Meadows should not be charged with voter fraud, he criticized Meadows’s history of supporting Trump’s false claims of voter fraud in the 2020 election that stoked the Jan. 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riot. Last week, the bipartisan panel investigating the storming of the Capitol by a pro-Trump mob released a report placing blame on “one man,” Trump, but naming others in the former president’s circle, such as Meadows, who supported him.

Earlier this year, the House recommended that Meadows be charged with contempt of Congress for refusing to cooperate with the Jan. 6 select committee, but the Justice Department declined to prosecute him.

“I urge federal prosecutors to hold accountable every single person who engaged in a conspiracy to put our democracy at risk,” Stein said. “None of the matters involving January 6th, however, are relevant to the specific allegations of voter fraud concerning Mr. and Mrs. Meadows that were referred to my office for review.”

Stein added that he reserved the right to reopen the case if new information comes forward.

READ MORE  A bull moose in a wetland. (photo: Encyclopedia Britannica)

A bull moose in a wetland. (photo: Encyclopedia Britannica)

The rule defines which “waters of the United States” are protected by the Clean Water Act. For decades, the term has been a flashpoint between environmental groups that want to broaden limits on pollution entering the nation's waters and farmers, builders and industry groups that say extending regulations too far is onerous for business.

The Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of the Army said the reworked rule is based on definitions that were in place prior to 2015. Federal officials said they wrote a “durable definition” of waterways to reduce uncertainty.

In recent years, however, there has been a lot of uncertainty. After the Obama administration sought to expand federal protections, the Trump administration rolled them back as part of its unwinding of hundreds of environmental and public health regulations. A federal judge rejected that effort. And a separate case is currently being considered by the Supreme Court that could yet upend the finalized rule.

"We have put forward a rule that’s clear, it’s durable, and it balances that protecting of our water resources with the needs of all water users, whether it’s farmers, ranchers, industry, watershed organizations,” EPA Assistant Administrator for Water Radhika Fox told The Associated Press.

The new rule is built on a pre-2015 definition, but is more streamlined and includes updates to reflect court opinions, scientific understanding and decades of experience, Fox said. The final rule will modestly increase protections for some streams, wetlands, lakes and ponds, she said.

The Trump-era rule, finalized in 2020, was long sought by builders, oil and gas developers, farmers and others who complained about federal overreach that they said stretched into gullies, creeks and ravines on farmland and other private property.

Environmental groups and public health advocates countered that the Trump rule allowed businesses to dump pollutants into unprotected waterways and fill in some wetlands, threatening public water supplies downstream and harming wildlife and habitat.

“Today, the Biden administration restored needed clean water protections so that our nation’s waters are guarded against pollution for fishing, swimming, and as sources of drinking water,” Kelly Moser, senior attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center’s Clean Water Defense Initiative, said in a statement.

Jon Devine, director of federal water policy for the Natural Resources Defense Council, called repealing the Trump-era rule a “smart move” that “comes at a time when we’re seeing unprecedented attacks on federal clean water protections by polluters and their allies.”

But Republican Sen. Shelley Moore Capito called the rule “regulatory overreach” that will “unfairly burden America’s farmers, ranchers, miners, infrastructure builders, and landowners.”

Jerry Konter, chairman of the National Association of Home Builders, struck a similar note, saying the new rule makes it unclear if the federal government will regulate water in places such as roadside ditches and isolated ponds.

A 2021 review by the Biden administration found that the Trump rule allowed more than 300 projects to proceed without the federal permits required under the Obama-era rule, and that the Trump rule significantly curtailed clean water protections in states such as New Mexico and Arizona.

In August 2021, a federal judge threw out the Trump-era rule and put back in place a 1986 standard that was broader in scope than the Trump rule but narrower than Obama’s. U.S. District Court Judge Rosemary Marquez in Arizona, an Obama appointee, said the Trump-era EPA had ignored its own findings that small waterways can affect the well-being of the larger waterways they flow into.

Meanwhile, Supreme Court justices are considering arguments from an Idaho couple in their business-backed push to curtail the Clean Water Act. Chantell and Michael Sackett wanted to build a home near a lake, but the EPA stopped their work in 2007, finding wetlands on their property were federally regulated. The agency said the Sacketts needed a permit.

The case was heard in October and tests part of the rule the Biden administration carried over into its finalized version. Now-retired Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in 2006 that if wetlands “significantly affect the chemical, physical, and biological integrity” of nearby navigable waters like rivers, the Clean Water Act's protections apply. The EPA's rule includes this test. Four conservative justices in the 2006 case, however, said that federal regulation only applied if there was a continuous surface connection between wetlands and an obviously regulated body of water like a river.

Charles Yates, attorney for the libertarian group Pacific Legal Foundation, said the new rule shows the importance of the Supreme Court case since the definition for WOTUS “shifts with each new presidential administration.”

“Absent definitive guidance from the Supreme Court, a lawful, workable, and durable definition of ‘navigable waters’ will remain elusive,” Yates said in a statement.

The Biden rule applies federal protections to wetlands, tributaries and other waters that have a significant connection to navigable waters or if wetlands are “relatively permanent.” The rule sets no specific distance for when adjacent wetlands are protected, stating that several factors can determine if the wetland and the waterway can impact water quality and quantity on each other. It states that the impact “depends on regional variations in climate, landscape, and geomorphology.”

For example, the rule notes that in the West, which typically gets less rain and has higher rates of evaporation, wetlands may need to be close to a waterway to be considered adjacent. In places where the waterway is wide and the topography flat, “wetlands are likely to be determined to be reasonably close where they are a few hundred feet from the tributary ...,” the rule states.

Fox said the rule wasn't written to stop development or prevent farming.

“It is about making sure we have development happening, that we’re growing food and fuel for our country but doing it in a way that also protects our nation’s water," she said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.