Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The unthinkable is now possible: Democrats are a win in Georgia away from expanding their Senate majority

Laxalt took an early lead in Nevada, with returns from the state’s rural counties arriving long before mail ballots from the more populous ones: Clark, home to Las Vegas, and Washoe, where Reno is located. But as votes from the state’s urban centers were counted, Laxalt’s advantage eroded, and by Saturday it was clear that Cortez Masto had amassed an insurmountable lead. He admitted as much on Saturday morning, writing on Twitter, “The race will come down to 20-30K Election Day Clark drop off ballots…If they continue to trend heavy DEM then she will overtake us. Thanks for all the prayers from millions of Nevadans and Americans who hope we can still take back the Senate and start taking our country back.”

A swing state where Democrats have experienced increasingly narrow wins in recent cycles, Nevada appeared teetering toward the GOP in polls leading up to Election Day. Those polls and Laxalt’s early lead in the state prompted the usual conspiracy-minded fabulists to cry fraud. On “Truth” Social, Trump declared without evidence that Clark County has a “a corrupt voting system.” His pilot fish, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) echoed the conspiracy on a Thursday call with Republican senators, claiming “There is no mathematical way Laxalt loses. If he does, then it’s a lie.”

No lie: it’s over. And Cortez Masto’s win — coupled with Democrat Mark Kelly’s triumph over Blake Masters (R-Disturbia) in Arizona — means Democrats will have at least 50 seats in the Senate next year. Pre-election, the thought of even holding their “tie-plus-VP-tiebreaker” majority seemed like a reach for Democrats. Now, an expanded, 51-seat majority is on the table. In Georgia, Democrat Warnock and Republican Walker will face off on Dec. 6. Warnock narrowly topped Walker in the first round of voting, but neither candidate surpassed the 50 percent threshold needed to claim the seat outright.

The scenario is a familiar one for Warnock, a senior pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, who won the Senate seat he currently occupies — and control of the chamber for Democrats — in a special election less than two years ago. Multiple women came forward during the campaign to accuse his opponent, Walker, a vocally anti-abortion Republican, of pressuring them to terminate pregnancies and paying for the procedures. Walker, a vocal critic of absentee fathers, was also forced to admit to having additional children with whom he had little contact, whose existence he had not publicly acknowledged, during the campaign.

A Warnock win would take Democrats’ seat count to 51, giving them something they didn’t have during President Biden’s first two years in office: a margin for error. The 50-50 split of the past two years meant the party’s progressive agenda was entirely beholden to its most conservative member, Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, and his aspiring “maverick” sidekick, Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema. In practice, that meant scaling back planned expansions of the social safety net to appease Manchin’s skepticism, as well as packaging action on climate change with perks for the fossil fuel industry to appease his home-state corporate benefactors.

Whether Democrats can turn their majority into meaningful legislation depends on what happens in the House. As of Saturday morning, Republicans had claimed 211 seats while Democrats had 201, but control of the chamber remains up in the air. Nearly two dozen districts, largely in western states where mail-in ballots are still being counted, have not yet been called.

Even if Democrats lose the House, a larger Senate majority could prove crucial for Biden’s judicial and executive nominees — the branches of government that tend to take over when Congress grinds to halt. The current Supreme Court is a testament to the long-lasting effects of such appointments: earlier this summer a trio of Trump appointees helped form the majority that overturned Roe v. Wade and ended a federal right to abortion access.

But Republicans’ five decade campaign to strip women of their Constitutional rights was answered with backlash at the polls this November — including in Nevada. Laxalt, grandson of former Nevada governor and U.S. senator Paul Laxalt, was the state’s attorney general from 2015 to 2019. During his tenure, he signed Nevada on multiple amicus briefs supporting anti-abortion efforts, despite overwhelming support for reproductive rights in the state. Laxalt, who appeared aware that his long-held views and strong ties to the antiabortion movement could hurt his bid in the pro-choice state, downplayed them as the election drew near.

Exit polls indicate Laxalt was right to worried: Abortion was, by far, the most motivating issue for Democrats who came out to support Cortez Masto: 89 percent reported that it was the most important issue to them. Abortion ranked only second to inflation as the most important issue to voters regardless of party.

READ MORE People on the main square of Kherson celebrate the city's liberation from Russian occupation on Saturday. (Photo: Washington Post)

People on the main square of Kherson celebrate the city's liberation from Russian occupation on Saturday. (Photo: Washington Post)

Scores of people flooded to Kherson’s central square on Saturday afternoon, less than 24 hours after the last Russian soldiers fled, surrendering this regional capital in a stunning setback to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war goals. A boombox blared techno music. Couples kissed and strangers hugged. Young men stood on top of cars, waving Ukrainian flags.

“We are so happy, despite all our struggles,” said Olga Malakh, 56, who was near tears as she stood in the central square. “We have lived through so much, but we will rebuild.”

But for others here, their struggles were too much to set aside, and it was clear many were just beginning to deal with the trauma, including the deaths and disappearances of loved ones.

Lyubov Obozna’s 28-year-old son, Dmytro, had been snatched by Russian security agents on Aug. 3 in front of his two young children. More than three months later, she still doesn’t know his whereabouts though she believes he is alive.

Amid the sea of happiness around her, Obozna, 61, stood ashen-faced, holding her six-year-old grandson’s hand. “We don’t know where he is,” she said.

Again and again, people stepped out of the celebrating crowd to say that a loved one was missing, or that they themselves had been detained, interrogated, tortured.

After weeks of silence from Kherson, where the occupying Russian forces had cut off almost all communication, people were now starting to tell their stories. And like in many other liberated towns and cities before this one — Bucha, Izyum, Lyman — the early signs were ominous.

Many people spoke of arbitrary searches, arrests, torture and disappearances.

As a few dozen people danced in a circle, Proskoviya Stepanova, 55, stood anxiously to the side.

Her son-in-law, a police officer named Vadim Valereyovich Barinov, 31, has been missing since March 28.

Stepanova had gone to the Russian-installed military administration where they had said not to worry, he would be questioned and let go. She had gone to the detention center, but they said they had no one by that name. Finally, she had gone to the cemetery, where she could smell what she believed were bodies being burned. “I really hope he is alive,” she said.

Others described occupation as a nightmare that lasted for months.

“Life under occupation was horrible,” said Tetiana Fomina, 58. “It was like living in a concentration camp. We were never free. The Russians had guns on them, and you never knew when they would come to get you.”

Fomina said she had cancer and needed chemotherapy but had been unable to get treatment for more than eight months. “At our hospital, in order to get any sort of treatment you’d need to show a Russian passport,” she said. “Otherwise you didn’t have any rights.”

Volodymyr Tymar, 18, said Russian soldiers had stripped him down to his underwear on the side of the road to look for pro-Ukrainian tattoos — describing what he said was a common tactic. Two of his friends had been detained for a week and a month respectively. They had hardly been fed, and were released with shaved heads.

“It was like a gulag,” he said.

Others described even worse treatment.

Valeriy, a 20-year-old military cadet, said Russian military police had searched his house in the spring while he was at work and found his military ID. They then came to his work and arrested him. He was taken to a base run by the FSB, the Russian federal security service, where he was blindfolded, beaten, and shocked with electricity for a week as the Russians tried to pry information out of him.

“When they took me home, I couldn’t speak for two weeks,” said Valeriy, who did not give his last name. “I thought I was gong to die in there.”

While many of those who had suffered remained silent, or told their stories quietly, scores more took to the central square, dancing and laughing.

When explosions sounded in the distance — likely outgoing rounds fired toward Russian positions on the other side of the Dnieper River — few in the crowd seemed to notice.

Yet the rumble of munitions was a reminders that the Russians “are not far away from us,” as Nataliya Chornenka said. Chornenka, head of the Korabelny section of Kherson, was among those who managed to flee the Russian occupation and had been asked to delay returning over concerns for their safety.

“People are calling all the time, asking ‘when can we go back?’ ” she said by phone from the central Ukrainian city of Vinnytsia. But “it’s possible there will be shelling and artillery fire,” she said. And “there is no electricity or water, and no communications connections.”

Reporters for The Washington Post were among the first wave of journalists to reach Kherson city on Saturday, and everywhere there was evidence of the intense fighting that preceded the Russian surrender.

The highway from the nearby city of Mykolaiv was littered with massive craters and burned-out vehicles. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said in his evening address that bomb disposal teams had removed some 2,000 explosive devices in the Kherson region — “mines, trip wires, and unexploded ammunition.”

In villages on the way to Kherson city, people old and young stood by the roadside to wave and shout greetings at soldiers entering the city.

In Kyselivka, itself liberated only on Thursday, two young men stood next to a hand-painted sign pointing the way to the regional capital, smiling and giving thumbs-up.

“Glory to our heroes,” another man shouted.

A few miles closer to Kherson city, a bridge had been blown up in what appeared to be a failed attempt to stop the Ukrainian advance.

At the edge of the city they had been trying to reach for months, young soldiers stopped in front of a “Kherson” sign and took selfies.

A few blocks farther into town, billboards showing a smiling blond girl promised that “Russia is here forever.”

A group of young men were painting over one of the billboards, rendering the promise — or threat — a laughingstock.

Kherson city had been without running water for four days, and without electricity for a week, residents said. Cellphones were useless. So, people at the central square resorted to shouting over the noise of raucous celebrations.

“We’ve waited for so long for this to happen,” Andriy Fyedorov, 23, said as he stood on top of a black SUV, waving a Ukrainian flag. “I always believed this would happen,” he said of liberation, “up until the very end.”

The mood was mostly festive. Techno music thumped as people danced and sang. Someone handed out candy and ice cream bars. Inside one restaurant, people cooked meat in the dark: a celebratory feast.

There was no sign of the occupiers who had terrified many here for the better part of a year. Most people in the square said it had been four or five days since they last saw Russian soldiers, though a few said they had seen Russians as recently as Friday.

Whenever it was, the occupiers left quickly.

Alina Kanivchenko, 19, said she had heard rumors earlier in the week that the Russians who had been living in a bunker down the street had fled. A friend went to check and found the Russians had left behind bulletproof vests, food and other belongings.

As dusk began to fall on the central square, more military vehicles arrived, each one welcomed with cheers, honks and chants of “Z.S.U.,” an acronym for the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

As the party continued, some people pulled away and headed home, along pitch-black streets, to dwellings without power or water. Among them were three children who were friends from the same neighborhood. They had walked 30 minutes to get to the square.

“We wanted to see the military,” said Iryna, 9, a soft-spoken girl in a hat and scarf. Now that it was dark, they were afraid of walking home alone.

Yehor, a 12-year-old with a Ukrainian flag around his shoulders, said some people in their neighborhood had generators but his home didn’t.

Iryna held a cardboard box full of canned meat, ice cream and chocolate bars that someone had given the children. “The last time we had this,” she said, “was when there was no war.”

For some, their joy was all the more intense because of what they had gone through.

Iryna Yefimova, 49, said Russian security agents had beaten down her door, hit her husband and 15-year-old son, and taken her prisoner. The Russians detained her for two months, she said, accusing her and a sister in Ukrainian-held territory of assisting the Ukrainian armed forces. When she was finally released, she received no explanation for her ordeal. But that encounter made Saturday all the sweeter.

“It’s freedom here,” she said.

“I’m happy in my soul,” added her son, Timofey.

Yet for others, there would be no happiness until their loved ones came home.

When Obozna’s son was detained on Aug. 3, his children saw him led away. “Are you going to give him back,” Dmytro’s six-year-old son had asked the Russian security agents.

Obozna went to the police to report that her son was kidnapped. The police said they would investigate, but instead it was the family that tracked Dmytro down to a detention center. Obozna wasn’t able to call or visit him, but she received word from released prisoners that her son was alive and okay.

But on Oct. 20, she heard the prisoners were being taken away. Obozna thought her son — who she said had fought in the Azov Regiment in 2015, perhaps putting him on the radar of the Russians — was now being held in a town across the Dnieper River. But as she spoke, another bystander interjected, saying he believed the prisoners had been taken to Crimea.

“We don’t know,” she said, shaking her head.

READ MORE Fox News host Tucker Carlson. (Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty)

Fox News host Tucker Carlson. (Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty)

The Fox News host would like you to know that someone else is to blame, but the candidates he backed largely flopped the midterm elections

Turns out Tucker’s type may not be super electable.

As Republicans scramble to find an explanation for their poor midterm showing, finger pointing abounds. “Heads should roll,” declared commentator Ben Shapiro. Trump, Kevin McCarthy, Mitch McConnell, the entire leadership of the party is under fire. So what about Tucker?

Carlson enjoys a position as a kingmaker and agenda setter for GOP politics. Look no further than how he almost single-handedly converted the “great replacement” conspiracy theory from a white nationalist talking point to a major policy concern for conservatives. If there’s a man besides Donald Trump with the power to catapult local political hopefuls into national political figures — and who wielded that power with unbridled enthusiasm in the lead-up to the election — is it not the man with the most watched cable news show in the country?

The candidates Carlson championed as the anti-establishment, America first, blood-and-soil future of conservative politics floundered in virtually every race where they weren’t an incumbent. Ohio Senator-elect JD Vance seems to be – at this moment – the only exception. Blake Masters lost to Mark Kelly in Arizona, where gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake is already resorting to claims of election rigging to explain her deficit to Democrat Katie Hobbs. In Washington state, the extremist affiliated House candidate Joe Kent is on the verge of an unexpected defeat at the hands of Democrat Marie Gluesenkamp Perez.

Vance, Kent, and Masters, were among Carlson’s most frequent guests on his flagship Fox News program Tucker Carlson Tonight. According to weekday cable segment data from watchdog group Media Matters, Vance, Kent, and Masters appeared on Carlson’s show 17, 14, and 10 times respectively in the year before the election (11/1/21-11/10/22). Vance and Kent were among the 20 most frequent guests on the show in that time period. Carlson also produced hour-long, in-depth interviews with each of them for Fox’s subscription-based streaming service, Fox Nation.

The three candidates were some of the clearest examples of how Carlson and his political allies hoped to gain national, legislative footholds that would help them reshape federal policies in their own image. All three of them ran their campaigns by spitting up the latest culture war panic ginned up by the Stephen Millers and Chris Rufo’s of the world. And the faustian bargain was evident to everyone watching.

In one appearance, Vance, whose campaign was supercharged and largely funded by conservative Silicon Valley billionaire Peter Thiel, declared Silicon Valley tech companies “enemies of western civilization.” Vance and Masters both went all in on pushing the racist great replacement conspiracy theory, accusing Democrats of wanting to “import” new voters via the southern border in order to win elections. Now there’s not a lot of border crossings in Ohio, but in Masters’ case, an over 100,000 vote deficit suggests that making such claims in a state with a large hispanic population harmed rather than helped.

A frequent guest on Alex Jones’ InfoWars network, Kent has been dogged by ties to extremism throughout his campaign. The Trump endorsed candidate appeared as a speaker at a rally on behalf of defendants accused of storming the Capitol on Jan. 6th. Kent has appeared repeatedly on Carlson’s show to attack the January 6th investigation, as well bolster Carlson’s claims that the 2020 election was suspect and the attack on congress was orchestrated by government operatives.

In one September monologue Carlson spoke directly to midterm candidates, whom he knows to be viewers of his show, elevating Kent as the example of a candidate who was hitting the messaging right and warning them against modeling themselves after party line candidates like Lindsey Graham. “If you do emulate Lindsey Graham and steal those talking points, you will lose,” he declared.

In that same monologue Carlson acknowledged that there was evidence the GOP was “alienating its own voters,” and encouraging the party to “talk about the issues that people actually care about in this country, issues that are relevant to their lives.”

But as it turns out, aligning with Carlson’s nightly demonization of undocumented immigrantion as the “greatest crime ever committed against the United States,” attacks against transgender and LGBTQ people that result in bomb threats to childrens’ hospitals, banning books you don’t like, and maligning anything and anyone that acknowledges racism as an attack on civilization (unless it’s against white people), may not actually be endearing to voters who arent soaked in the lore of Fox News’ universe.

Nowhere is the divide clearer than among young voters, who early reports indicate had the second highest level of turnout in the past three decades, and who heavily favored democrats. As of yesterday, we saw a 27 percent turnout of youth voters 18-29, with a 28-point margin favoring Democrats.

A lot of the culture rhetoric coming from the right is a signal that they “do not trust young people,” says Jack Lobel, deputy communications director of the progressive gen-Z group Voters of Tomorrow, tells Rolling Stone. Lobel explains that the conservative focus on policing inclusivity, and demonizing honest and open discussions about race and sexual identity is offputting to slews Americans reaching voting age, who feel infantilized. “Gen Z turned out, again, to deliver a blow to the far-right for the third consecutive cycle in a row…because we know stuff, and we know that they are not fighting for our futures,” he said.

During his monologue Wednesday night, Carlson argued that “the people whose job it was to win but did not win should go do something else now. We’re speaking specifically of the Republican leadership of the House and the Senate and of the RNC.” This is a bit rich, as Fox operates as an integral public relations arm of the Republican Party, and Carlson’s programming is a core medium of the GOP’s messaging and policy priorities.

Carlson won’t be losing his job anytime soon, nor taking any lessons from his wipeout, but Tuesday’s midterms are a sign that many voters are not sold on having his acolytes run their country.

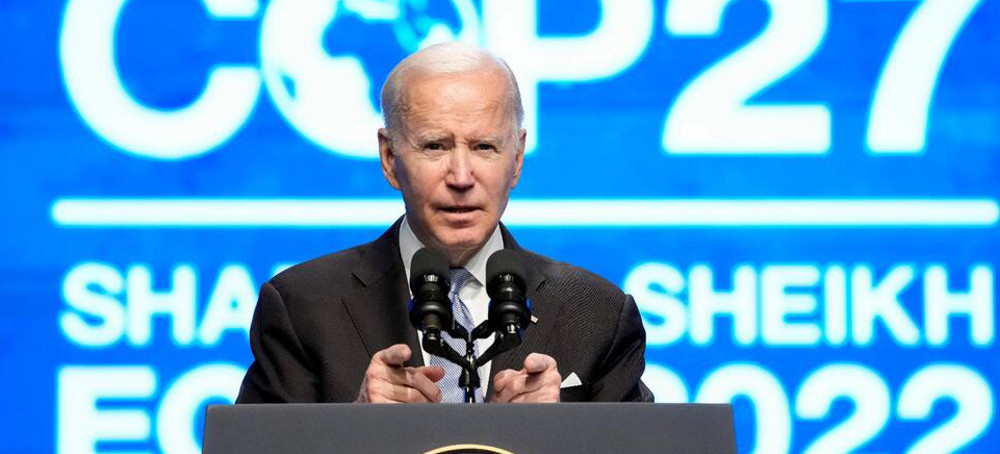

READ MORE President Joe Biden speaks at the COP27 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 11, 2022, at Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. (Photo: AP)

President Joe Biden speaks at the COP27 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 11, 2022, at Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt. (Photo: AP)

The Biden administration has ramped up efforts to reduce methane emissions, targeting the oil and gas industry for its role in global warming even as President Joe Biden has pressed energy producers for more oil drilling to lower prices at the gasoline pump.

Biden announced a supplemental rule cracking down on emissions of methane — a potent greenhouse gas that contributes significantly to global warming and packs a stronger short-term punch than even carbon dioxide — as he attended a global climate conference in Egypt.

“We’re racing forward to do our part to avert the ‘climate hell’ the U.N. secretary general so passionately warned about,'' Biden said, referring to comments this week by United Nations leader António Guterres.

The new methane rule will help ensure that the United States meets a goal set by more than 100 nations to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030 from 2020 levels, Biden said.

“I can ... say with confidence, the United States of America will meet our emissions targets by 2030,'' he said.

The Environmental Protection Agency rule follows up on a proposal Biden announced last year at a United Nations climate summit in Scotland. The 2021 rule targets emissions from existing oil and gas wells nationwide, rather than focusing only on new wells as previous EPA regulations have done.

The new rule goes a step further and takes aim at all drilling sites, including smaller wells that now will be required to find and plug methane leaks. Small wells currently are subject to an initial inspection but are rarely checked again for leaks.

The proposal also requires operators to respond to credible third-party reports of high-volume methane leaks.

The Biden administration will embark on “a relentless focus to root out emissions wherever we can find them,” White House national climate adviser Ali Zaidi said Friday.

Oil and gas production is the nation’s largest industrial source of methane, the primary component of natural gas, and is a key target for the Biden administration as it seeks to combat climate change.

“We must lead by example when it comes to tackling methane pollution — one of the biggest drivers of climate change,'' said EPA Administrator Michael Regan, who also is in Egypt for the climate talks. The new, stronger standards “will enable innovative new technology to flourish while protecting people and the planet,” he said.

“Our regulatory approach is very aggressive from a timing standpoint and a stringency standpoint," Regan said at a briefing in Egypt. The old and new rules should be able to prevent more than 80% of the energy waste, about 36 million tons (32.6 million metric tonnes) of carbon emissions, he said.

Leakage from wells and pipelines is why former Vice President Al Gore and others call natural gas “a bridge to nowhere.” In an interview with The Associated Press, Gore said: “When you work the math, a leakage of 2 to 3% of the methane completely negates the climate advantage of methane gas. And, tragically, the wildcatters that do most of the hydrological fracturing do not pay attention to the methane leakage. You have leakage in the LNG (liquefied natural gas) process, you have leakage in pipelines, you have leakage in the use.”

The supplemental rule comes as Biden has accused oil companies of “war profiteering” and raised the possibility of imposing a windfall tax on energy companies if they don’t boost domestic production.

Biden has repeatedly criticized major oil companies for making record-setting profits in the wake of Russia's war in Ukraine while refusing to help lower prices at the pump for the American people. The Democratic president suggested last week that he will look to Congress to impose tax penalties on oil companies if they don’t invest some of their record-breaking profits to lower costs for American consumers.

Besides the EPA rule, the climate and health law approved by Congress in August includes a methane emissions reduction program that would impose a fee on energy producers that exceed a certain level of methane emissions. The fee, set to rise to $1,500 per metric ton of methane, marks the first time the federal government has directly imposed a fee, or tax, on greenhouse gas emissions.

The law allows exemptions for companies that comply with the EPA’s standards or fall below a certain emissions threshold. It also includes $1.5 billon in grants and other spending to help operators and local communities improve monitoring and data collection for methane emissions, with the goal of finding and repairing natural gas leaks.

Multiple studies have found that smaller wells produce just 6% of the nation’s oil and gas but account for up to half the methane emissions from well sites.

“We can’t leave half of the problem on the table and expect to get the reductions that we need to get and protect local communities from pollution,” said Jon Goldstein, senior director of regulatory affairs for oil and gas at the Environmental Defense Fund.

The draft rule is "a welcome sign that reducing methane emissions is a top priority for EPA,'' said Darin Schroeder, an associate attorney at Clean Air Task Force.

The oil industry has generally welcomed direct federal regulation of methane emissions, preferring a single national standard to a hodgepodge of state rules.

Even so, oil and gas companies have asked the EPA to exempt hundreds of thousands of the nation’s smallest wells from the upcoming methane rules.

The American Exploration and Production Council, which represents the largest independent oil and gas companies in the U.S., said it appreciates changes made by EPA as the rule was developed but still has concerns to make it truly workable. "We will continue to work with EPA on meaningful solutions,'' said Anne Bradbury, the group's CEO.

The EPA will accept public comments through Feb. 13 and issue a final rule in 2023.

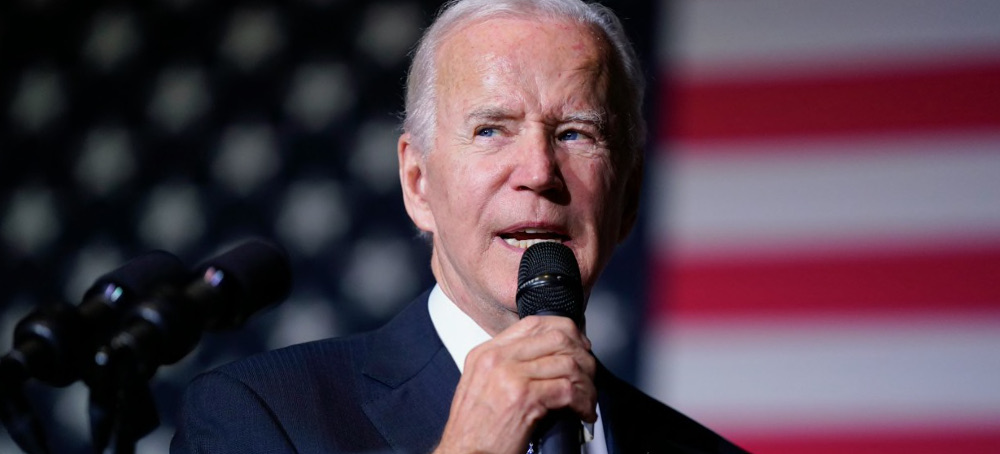

READ MORE President Joe Biden. (photo: Evan Vucci/AP)

President Joe Biden. (photo: Evan Vucci/AP)

The party's hold on the Senate majority, as projected by NBC News, means Democrats can confirm more liberal and diverse judges without the threat of Republican obstruction.

The Senate majority, inked by a Democratic win in Nevada, gives Biden a clear runway to continue one of his most consequential pursuits: reshaping federal courts with a diverse array of lifetime-appointed liberal judges, including record numbers of women, minorities, former public defenders and civil rights lawyers.

The Senate has confirmed 84 Biden-nominated judges, including Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson as the first Black woman on the Supreme Court and 25 appeals court judges, confirming judges at a faster rate than President Donald Trump before the 2022 election.

“Senate Democrats have been committed to restoring balance to the federal judiciary with professionally and personally diverse judges,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer told NBC News on Saturday night. “With two more years of a Senate Democratic majority we will build on our historic pace of judicial confirmations and ensure the federal bench better reflects the diversity of America.”

Trump, in tandem with Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell, confirmed 234 judges in his four years — including three Supreme Court justices and scores of young conservatives poised to rule on cases for generations. Senate Republican leaders told NBC News before the election that if they took the majority, they would use their power over the floor to compel Biden to send more centrist judges that GOP senators could support.

“This is a major bullet dodged, because it means Biden will have the opportunity to build on what will go down as a signature legacy item for him, which is a true makeover in the composition of the courts if he’s given a full four years of running room,” said Brian Fallon, who runs the courts-focused liberal group Demand Justice. “He won’t just be competitive with Trump over a four-year span with total nominees confirmed, he’ll also have left a lasting mark.”

Like other liberals, Fallon feared that Republicans would have slowed judicial confirmations to a crawl if they took control of the Senate. He said Democrats keeping control means that if a Supreme Court vacancy were to open up, Biden’s nominee would be assured a vote. But he said he doesn't agree with some liberals who argue Justices Sonia Sotomayor or Elena Kagan should retire so Democrats can hold their seat for longer by confirming younger justices.

Fallon argued that a “silver lining” to a possible Republican-controlled House is that the halting of Biden's legislative agenda means “judicial nominations are the only game in town in terms of the agenda in the Senate,” at least if the second half of Biden’s term is anything like Trump’s last two years.

NBC News projected Saturday that Democrats will win the Nevada Senate race and carry at least 50 seats, enough to keep control with the tie-breaking vote of Vice President Kamala Harris — and could get a 51st if they win the Georgia Senate runoff on Dec. 6. NBC News has not yet projected which party will control the House, with a close battle and votes still being counted in key races.

That leaves conservatives with little hope of thwarting Biden's selected judges, after unsuccessful attempts in recent years to sway centrists like Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., to vote down some of them.

“Biden promised unity and moderation but has consistently nominated radical judges to appease the liberal dark money groups who helped elect him. Unfortunately, Senate Democrats have simply rubber-stamped his picks and I expect that pattern to continue,” said Carrie Severino, the president of the Judicial Crisis Network, a well-funded advocacy group that fights for a more right-leaning judiciary and also does not disclose its donors.

“JCN will continue to use whatever means necessary to highlight Biden’s extremist judges who care more about delivering liberal policy results from the bench than following law,” she said.

While the current 50-member Democratic caucus has been unified behind Biden’s judicial nominees, a 51st seat for the party could further embolden it. Currently the 50-50 split means the Judiciary Committee is also evenly divided and Republicans can force Democrats to jump through an additional hoop and eat up hours of Senate floor time to secure a vote on a judge. If Democrats hold on to their seat Georgia, they could deny the GOP that option.

Currently there are 76 vacancies on district courts and 9 on appellate courts. That number is sure to grow as more judges retire and open up their seats in the next two years.

Some on the left have pushed Senate Judiciary Chair Dick Durbin, D-Ill., to end a courtesy known as the “blue slip” that allows senators to block consideration of district court judges in their home state. As a practical matter, that means Democrats currently need Republican sign-off to confirm judges in red states. (GOP leaders eliminated the rule for circuit judges but kept it for district courts.)

Asked by NBC News in September if he would preserve the tradition, Durbin said it has worked for the Senate and he’s “sticking with” it if he remains Judiciary chairman for two more years.

Democrats' hold on the Senate alleviates the pressure on Schumer to push through judges in the lame duck session, which party leaders were planning to do in case Republicans took control, wary of whether they would allow votes on those nominees.

For now, both parties are expected to spend heavily in the Georgia runoff between Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock and Republican challenger Herschel Walker, which could make it slightly easier for Democrats to maneuver Biden's judicial nominations.

“Georgia is still important for the judicial confirmation project because it’s really been a bitch to have to deal with all these discharge petitions on the floor,” Fallon said. “The process will be even more streamlined if we can add Georgia in the runoff.”

Americans are being inundated with messaging about a surge in crime rates. But the reality is more complicated. (Photo: Getty)

Americans are being inundated with messaging about a surge in crime rates. But the reality is more complicated. (Photo: Getty)

But is there actually a crime wave? Turns out the answer is deeply complicated. So is the question.

Start with the FBI crime stats from 2021, "the big takeaways were crime is up on some measures and it's down on others," says Insha Rahman of the Vera Institute of Justice.

In broad strokes — up on homicides, down on property crimes — similar to 2020. But those numbers come with a giant asterisk. Because of a long-planned change in reporting standards, most cities did not report their 2021 crime numbers to the FBI.

"It's turned our crime data into this sort of giant black hole I don't think we'll ever actually be able to undo," according to John Pfaff, a law professor at Fordham University. "I think 2021 will always just be a giant gap in our narrative."

Even when we have more complete data, the stories we tell about crime are filled with holes that misinformation can crawl into and take up residence.

"A big mistake we make with crime narratives is the effort to tell a narrative," Pfaff says. "Crime is deeply local."

Telling a single story of crime will always result in a Frankenstein, he says, because it requires grafting together multiple stories, often with very different arcs.

Pfaff points to 2020, when there was an "unambiguous nationwide increase in homicides."

"There's no denying that, but what's interesting is that if you look at it sort of city by city, the patterns by which it happens vary," Pfaff says.

Another problem? Too often we base the story of rising crime on increments of time that are statistically meaningless.

"Both journalists and elected officials have a habit of comparing crime today to crime last year," says Robert Vargas, a sociologist at the University of Chicago.

Even looking across a few years only gives us a hastily taken snapshot that's out of focus and badly framed.

"There's absolutely no systemic or scientifically informed way of thinking about crime trends" in this short term way, Vargas says.

Which is why, when it comes to crime, it's imperative to take the long view, says Rena Karefa-Johnson, with the advocacy group Fwd.Us.

"It is often lost that there are certain crimes like property crimes that are actually at historic lows," she says. "For the crimes like gun homicide that have increased and spiked and that we really need to focus on, we're still not talking about rates anywhere near the historic highs of the nineties."

"People were 80% less likely to be a victim of violent crime in 2021 compared to 1993," she says.

What is rising, unhinged from the complex facts on the ground, is the frenzied narrative around rising crime.

What we mean when we talk about crime

To really understand how we count crime, it is imperative to understand what crimes count.

"We generally talk about, 'crime is up' or 'crime is down,'" Pfaff says. "It's referring to sort of this small core set of what the FBI calls index one crimes."

That's murder, robbery, rape, aggravated assault, larceny, burglary, auto theft, and arson. Over a century ago, those crimes were selected by a group of police chiefs to develop a system of uniform crime statistics. Other than the addition of arson in 1979, the list remains unchanged.

"I don't think crime data tells you all that much," says Vargas. "It tells you how police behave as an organization."

In this system, shoplifting tampons or diapers counts as crime, but tax evasion, environmental crimes, and wage theft do not. Police aren't even responsible for investigating those crimes.

"Wage theft is a problem about five times the magnitude of shoplifting," says Alec Karakatsanis, an activist, lawyer and executive director of Civil Rights Corps.

"Wage theft is when companies steal money from usually low-income workers," he explains. Estimates are that this kind of theft costs workers $50 billion a year. In the past decade the estimated cost of tax fraud has risen to $1 trillion a year — most of it stolen by the wealthy and corporations.

The way the system is set up perpetrators of what we call crime are more likely to be poor people, because that's how crime is defined.

The data is biased in another way too, Vargas says, by who police choose to target as criminals.

"They're going after people selling drugs, people committing traffic violations, oftentimes in poor neighborhoods, poor Black and brown neighborhoods and not other neighborhoods."

Numerous studies have shown that Black and brown people are policed and arrested at much higher levels than white people.

"If you are a teenager who gets in a physical fight and you're Black in a public school in New York, that's crime," says Karefa-Johnson.

"You get arrested by the police, you get taken into criminal court and you're charged with assault," she says. But when white teenagers get into a fight, "specifically white children who go to private schools or go to schools in more affluent areas where there are no police in the classroom, it's not something that we see thought about as a crime."

Karefa-Johnson says our understanding of crime is constructed by choices - choices to not include white collar crime, choices to target poor people of color - made by those in power.

"Crime is very much a social construct," she says. "I know it can be made to feel like something that is more objective or something that is more long-standing, a category that has its own gravitas. But it's very much a reflection of who's in power, of the way that society is ordered and that the way we want to keep it ordered."

Crime is a story that we are told, and the people who write the first draft of that story, down to defining the language, are the police.

The politics of police

"A lot of the big police departments have really big media departments," Pfaff says. "They have press information officers that are out there really trying to structure the narrative."

Police are political actors, not reliable narrators.

"When people talk about a crime wave, they're basing that on a very distorted set of data the police themselves are manipulating and curating for their own political reasons."

Karakatsanis points out another set of crimes that doesn't make it into police stats: "crimes committed by police themselves."

Police unions are deeply political entities, most often found lobbying against criminal justice reform, progressive prosecutors and for Republicans, like their support for former President Donald Trump.

That's playing out across the country right now. In the Wisconsin senate race the Fraternal Order of Police, alongside a majority of Sheriffs and other law enforcement agencies, have thrown their political weight behind the incumbent, "tough-on-crime" Republican Ron Johnson. Johnson has also called the criminal Jan. 6th attack on the Capitol "a peaceful protest."

In 2021, he told conservative talk show host Joe Pag, "I knew those were people that love this country, that truly respect law enforcement, would never do anything to break the law." He added that had they been "Black Lives Matter and Antifa protesters, I might have been a little concerned."

Unlike the insurrection, the Black Lives Matter racial justice protests of the summer of 2020 were mostly peaceful. The response to them by police was not.

The ad game

That same brand of thinly veiled racism in Johnson's comments about Black Lives Matter was on display in campaign ads against his Democratic challenger, Mandela Barnes. In one, paid for by the Senate Leadership Fund, a narrator asks the viewer, "do you feel safe?' while ominous music thumps in the background.

"Mandela Barnes would eliminate cash bail, setting accused criminals free into the community before trial, even with shootings, robberies, carjackings, violent attacks on our police. More than 300 murders last year alone. Yet Barnes has even supported defunding the police. Mandela Barnes, he stands with them, not us."

The not so subtle suggestion being that Barnes, who is Black, stands with the images of the alleged criminals in the ad, all of whom are also Black.

The ad not only attacks Barnes, but also bail reform. It's been a popular target of the right, in lockstep with police, claiming that it will let violent suspects — almost always depicted as Black and brown — out onto the street. That's despite a lack of evidence that shows a connection between bail reform and increased crime.

"This is like climate science denial, right?" Karakatsanis says.

"We know from the actual evidence the things that determine the level of crime or violence or harm in a society are bigger structural factors." He lists off some examples — poverty and inequality, early childhood education, and access to mental health care.

Still in places such as Wisconsin, ads that push the narrative of a crime wave have been working, says the Vera Institute for Justice's Insha Rahman.

"When those narratives go unchecked, because there's huge amounts of money and private interests behind these ads, they are incredibly potent and powerful," she says. "They have a real impact on what happens in our elections because they play to people's emotions and perceptions and fears."

Crime is, for many people, a metaphor for deeper fears, says law professor John Pfaff.

"We use crime as a shorthand for fear of other people, especially people of color," he says. "We use it as a proxy for deeper racial fears that white people don't feel comfortable expressing."

Republicans continue to be seen by many voters as better on crime, Rahman says, even when people know their "tough on crime" solutions have repeatedly proven unsuccessful. "When it's the only option on offer, it's what people go to because in the absence of a proactive, affirmative vision for safety, you pick the thing that you know, even if you know it doesn't really work."

Democrats, she says, have failed to give any alternative for what safety could look like. Just examine the accusation — like the one falsely made against Mandela Barnes — that Democrats want to "defund the police." Rahman says most Democrats go on the defensive by saying, "No, no, I wanna fund the police."

"Turns out, at least from the polling, that's not a very effective tactic. But that's the only response that we are seeing to those attacks."

People are looking for a different, more complex vision for safety, Rahman says, they just aren't finding it.

Perhaps the groups most desperate for real policies that lead to safety are those who are most impacted by violent crime, especially homicide — which spiked in 2020 and has remained high in some places, says Rena Karefa-Johnson. The largest increase in murders in 2020 were actually in Republican-led states and cities.

But all this messaging around crime is not meant for those who bare its brunt, Karefa-Johnson says.

"The communities that are most uniquely harmed by gun violence," she says, "are also the communities that are most uniquely harmed by long sentences, by pretrial detention, by draconian approaches to criminal justice reform."

Backlash

We've seen these crime wave narratives crest before.

In the mid-1960s and '70s we saw the emergence of the "tough on crime" lexicon, the language that accompanies the politics of "law and order" — describing a surge of crime, riots and lawlessness rampant in "dangerous" cities — especially, of course, presumed lawlessness in Black neighborhoods.

That was the dawn of a certain kind of American war: The war on crime, the war on drugs, the revival of the death penalty, felon disenfranchisement statutes, and the start of a still ongoing project of mass incarceration.

What was going on in those "lawless" cities across the United States? Riots that, like Watts in 1965, have come to be understood by many scholars and activists as uprisings against police violence, racism, and oppression. In the South there were nonviolent protests led by Black freedom fighters, although there was violence there too, coming from the police's side.

It was "the largest civil rights protests this country had ever seen," says Rahman. Until the protests that swept across the country in the summer of 2020.

"We are seeing that same kind of backlash of weaponizing issues of crime and safety today," she says.

"It's very important for powerful people, especially in moments of uprising and moments of social unrest, to attempt to create a moral panic around crime," says Karakatsanis.

Moral panics are a way of pushing back against change or reform, a way of preserving the status quo. But this time it isn't about keeping things the way they have been, Karakatsanis says, because while the Republican Party is running on a moral panic about crime, they are also openly anti-democratic.

"The reactionary backlash against the protests of 2020 is coming at a time when this country is hurtling fast toward fascist and authoritarian life," he says.

And in response to the rising threat of fascism, both Republicans and Democrats are calling for more police.

President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen speaks during the Sharm El-Sheikh Climate Implementation Summit (SCIS) of the UNFCCC COP27 climate conference on Nov. 8, 2022 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. (Photo: Sean Gallup/Getty)

President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen speaks during the Sharm El-Sheikh Climate Implementation Summit (SCIS) of the UNFCCC COP27 climate conference on Nov. 8, 2022 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt. (Photo: Sean Gallup/Getty)

November 11, 2022 These Rich Nations Are Finally Committing Cash to Climate Reparations. The US Isn’t Among Them

Delegates at COP27 will officially discuss for the first time the creation of a global fund for “loss and damage”—the idea that rich nations are largely responsible for causing global warming and therefore owe a financial debt to poorer countries struggling to deal with the costs of worsening drought, storms and other climate-fueled disasters.

For 30 years, developing countries—predominantly in the Global South—have called for such a fund and been met with resistance. But this week, several Western countries, mostly in Europe, committed to begin paying that debt with cash, signaling a notable shift in the decadeslong fight and marking one of the most surprising developments so far this year at the United Nations’ cornerstone climate summit.

“The COP must make progress on minimizing and averting loss and damage from climate change,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said during her Tuesday speech at the conference in Egypt, during which she encouraged other world leaders to also support the loss and damage fund. “It is high time to put this on the agenda.”

As of Friday morning, Germany has pledged $170 million for the fund, while Australia has pledged $50 million, Ireland has pledged $10 million and Belgium has promised $2.5 million. Scotland—which pledged $2.2 million to the cause when it hosted COP26 last year—increased that commitment this week by an additional $5.7 million. And in September, Denmark promised $13 million to the effort.

The announcements, however, were met with mixed reactions from climate activists and world leaders living in some of the world’s most climate-vulnerable places, including Pakistan, which suffered deadly and historic flooding this year that left a third of the country underwater for months.

At just over $250 million, the recent commitments fall drastically short of the $200 billion in annual funding for “climate reparations” that the U.N. says is needed this decade alone to adequately address the issue. It also falls far below the $100 billion in annual international climate spending that the world’s wealthiest nations previously promised in a similar 2009 U.N. agreement, but have failed so far to deliver.

Two of the most significant carbon emitters, the United States and China, were also notably absent from the slew of announcements. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the U.S. has produced roughly a quarter of the world’s total greenhouse gas emissions, making it by far the most significant overall contributor to the climate crisis, according to 2020 data from the Union of Concerned Scientists. And in the short span of China’s industrial boom, it quickly became the second leading historical contributor, responsible for 14 percent of total emissions.

Rather than committing federal dollars directly, the U.S. announced this week that it was launching a global carbon market as soon as next year, saying it would help raise money for developing countries by selling so-called “carbon credits” to companies that want to offset their emissions. Switzerland, too, announced a similar plan to leverage money raised through carbon credits to pay for its climate commitments. And China said it would be willing to participate in a global carbon market scheme once it’s up and running.

Carbon markets are financial schemes that allow a participant to pay other people to reduce their emissions rather than the participant reducing its own emissions. For example, Company A could pay Company B to plant trees or upgrade their buildings to make them more energy efficient, which in theory will reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions going into the atmosphere. But Company A isn’t necessarily reducing its own emissions—it’s paying other companies to reduce theirs.

But carbon markets, along with other voluntary market-based solutions that rely on incentives, not regulation, to reduce emission, have long been a source of controversy in the climate community. It’s not surprising, then, that the U.S. announcement this week was met by fierce backlash from environmental advocates who say carbon markets rarely deliver the climate benefits they promise, suffer from poor management and regulation and delay meaningful efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by promising to address the issue in the future. Rather, advocates say, that money should be spent on proven climate solutions, such as building new renewable energy sources.

Take California, for example, which runs one of the world’s largest carbon markets. Instead of reducing their own emissions, companies participating in the state’s carbon market—including major conglomerates like Microsoft—have poured billions of dollars into projects that planted trees. But even though an estimated 153,000 acres of forests that were part of the state’s carbon market burned in wildfires last summer, the companies can still claim those forests for credits in the program.

In fact, just a day prior to the U.S. announcement this week, U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned delegates not to rely on carbon markets to achieve their climate goals.

“The absence of standards, regulations and rigor in voluntary carbon market credits is deeply concerning,” Gutteres said in a speech Tuesday. “Shadow markets for carbon credits cannot undermine genuine emission reduction efforts, including in the short term. Targets must be reached through real emissions cuts.”

On Thursday, U.S. climate envoy John Kerry defended the carbon market plan, saying there was “not enough money in any country in the world to actually solve this problem.”

Quickly evolving geopolitics, high inflation and soaring energy prices have prompted many governments to backtrack on climate pledges in recent months. On Friday, President Joe Biden touted U.S. efforts to help adaptation efforts in Africa, but refrained from mentioning the new carbon market plan. The U.S. initially pledged $11 billion to help developing nations, but a divided U.S. government only approved $1 billion this year for that effort—an issue that’s largely out of Biden’s hands.

“We desperately need money,” Kerry told CNN. “It takes trillions and no government that I know of is ready to put trillions into this on an annual basis.”

But debate over who should pay—and how—when it comes to dealing with the costs of climate change remains fiercely undecided. And many climate activists see this week’s U.S. proposal as the latest evidence that COP27 has been co-opted and compromised by corporate interests. Activists have chastised the summit’s organizers for allowing one of the world’s biggest plastic polluters to sponsor the conference, as well as hiring a global public relations firm that also represents major oil companies as clients.

Still, excluding corporations from COP27, even those that are greenwashing their images, would be a bad idea, said Michael Vandenbergh, a law professor and the director of Vanderbilt Law School’s Climate Change Research Network. In many ways, he told me in an interview, buy-in and cooperation from the private sector is vital for the larger international effort to be successful.

Vandenbergh, who conducts research on the private sector’s role in combating climate change, said companies are failing to meet their climate goals at the same rates as countries and cities, so exiling them now would only hurt the broader effort. Instead, he said, people should focus on reducing greenwashing and holding companies accountable to their promises.

“Climate change poses an urgent, major threat, so all options, including private sector action, should be on the table,” Vandenbergh said. “It is true that, as a globe, we are not meeting the Paris Agreement terms, but that is not a reason to give up hope or to abandon smart strategies.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.