Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

My wife is a forgiving person. She has not filed for guardianship. She kicks my butt at Scrabble but she’s gracious about it. She rations my bacon cheeseburgers. She tells me if I look bedraggled so I don’t walk down the street and people hand me spare change. And she turns out the light at night and rolls over and puts her arms around me. This is better than a Pulitzer Prize. So I don’t wake up in the morning with an aching in my head and the blues all around my bed and the water tastes like turpentine because my good gal left me here cryin’. She didn’t. She has made coffee and she has read the morning paper so that I don’t need to. When you skip the news, life is a lot more like Anne of Green Gables or The House at Pooh Corner.

I shall take a break from high dudgeon. A man who leaves the shower running needs to give outrage a rest. So I find myself in a sort of second childhood. People are friendly to me because they sense that I’m harmless. The young woman in the coffee shop smiles and says, “What can I get you, my friend,” and this makes my day. As Tennessee Williams said, “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

I don’t comprehend the anger you see out there in America. The truckers’ convoy, yes; driving big trucks is a miserable hard life, but the biker brigades who come roaring through town louder than a 757, bulky men with graying ponytails wearing leather, flying the flag and bearing vulgar right-wing bumper stickers, these are suburban sociopaths who just want to be noticed — but to what end? These are expensive bikes, the riders are well-fed, what’s their beef? Just because you’ve wasted forty years on adolescence, it’s not too late to get a life.

A man needs heroes to light the way. One of mine is the cardiologist who performed a heart catheterization on me recently in an OR with a team of men and women and the powerful sense of competence in that room was impressive to me, the man who left the water running. Another hero is my editor Roger Angell who died at the age of 101, the graciousness of his life, his classiness, the joy he took in his old age right up to the end, the happiness of his writing.

Another is Duke Ellington — long gone from the world but you can go on YouTube and he’s there in force, “Take the A Train” and “Mood Indigo,” his Sacred Concerts and “Caravan” — who toured the country with his 15-piece orchestra, playing ballrooms packed with his fans, a dance floor where people could jitterbug swing. This was back when segregation was still in force and the band never knew if they could get a hotel room or a meal in a restaurant. They were all Black, but Juan Tizol, the trombonist, was fairly light-skinned and had to wear blackface so nobody would think the band was integrated.

Ellington was elegant and cool and he didn’t deign to address bigotry — he just played right through it. He’s famous for his band compositions but I love his solo stuff, the man was a great pianist.

Not all that much has changed in the fifty years since Duke died. There’s rampant craziness in the country still, but Duke’s example is worth copying: ignore the hatred and create something great. The old Southern segregationist senators are gone and forgotten and Duke lives on, an American treasure. Anger dies; genius endures. He came out of ragtime and into swing and was unaffected by rock ’n’ roll and is flying along still.

A Russian gold processing plant in the desert outside al-Ibediyya, 200 miles north of the Sudanese capital, Khartoum. (photo: Abdulmonam Eassa/NYT)

A Russian gold processing plant in the desert outside al-Ibediyya, 200 miles north of the Sudanese capital, Khartoum. (photo: Abdulmonam Eassa/NYT)

Backed by the Kremlin, the shadowy network known as the Wagner Group is getting rich in Sudan while helping the military to crush a democracy movement.

Locals call it “The Russian Company” — a tightly guarded plant with shining towers, deep in the desert, that processes mounds of dusty ore into bars of semirefined gold.

“The Russians pay the best,” said Ammar al-Amir, a miner and community leader in al-Ibediyya, a hardscrabble mining town 10 miles from the plant. “Otherwise, we don’t know much about them.”

In fact, Sudanese company and government records show, the gold mine is one outpost of the Wagner Group, an opaque network of Russian mercenaries, mining companies and political influence operations — controlled by a close ally of President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia — that is expanding aggressively across a swath of Africa.

Best known as a supplier of hired guns, Wagner has in recent years evolved into a far broader and more sophisticated tool of Kremlin power, according to experts and Western officials tracking its expansion. Rather than a single entity, Wagner has come to describe interlinked war-fighting, moneymaking and influence-peddling operations, low-cost and deniable, that serve Mr. Putin’s ambitions on a continent where support for Russia is relatively high.

Wagner emerged in 2014 as a band of Kremlin-backed mercenaries that supported Mr. Putin’s first foray into eastern Ukraine, and that later deployed to Syria. In recent months, at least 1,000 of its fighters have re-emerged in Ukraine, British intelligence has said.

The linchpin of Wagner’s operations, according to Western officials, is Yevgeny V. Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch known as “Putin’s chef” who was indicted in the United States on charges of meddling in the 2016 presidential election.

In 2017, Wagner expanded into Africa, where its mercenaries have become a significant, sometimes pivotal factor in a string of conflict-hit countries: Libya, Mozambique, Central African Republic and most recently Mali where, as elsewhere, Wagner has been accused of atrocities against civilians.

But Wagner is far more than a war machine in Africa, and a close look at its activities in Sudan, the continent’s third largest gold producer, reveals its reach.

Wagner has obtained lucrative Sudanese mining concessions that produce a stream of gold, records show — a potential boost to the Kremlin’s $130 billion gold stash that American officials worry is being used to blunt the effect of economic sanctions over the Ukraine war, by propping up the ruble.

In eastern Sudan, Wagner is supporting the Kremlin’s push to build a naval base on the Red Sea to host its nuclear-powered warships. In western Sudan, it has found a launchpad for its mercenary operations in neighboring countries — and a possible source of uranium.

And since Sudan’s military seized power in a coup in October, Wagner has intensified its partnership with a power-hungry commander, Lt. Gen. Mohamed Hamdan, who visited Moscow in the early days of the Ukraine war, which began in February. Wagner has given military aid to General Hamdan and helped Sudan’s security forces to suppress a fragile grass-roots, pro-democracy movement, Western officials say.

“Russia feeds off kleptocracy, civil wars and internecine conflicts in Africa, filling vacuums where the West is not engaged or not interested,” said Samuel Ramani of the Royal United Services Institute, a defense research group in London, and the author of a forthcoming book on Russia in Africa.

Sudan, Mr. Ramani added, typifies the kind of country where Wagner thrives.

The Kremlin and Mr. Prigozhin deny any links to Wagner, which is said to be named after Richard Wagner, Hitler’s favorite composer, by a founding commander who was fascinated by Nazi symbolism and history.

Mr. Prigozhin shrouds his activities in secrecy, trying to mask his ties to Wagner through a web of shell companies and traveling the African continent by private jet for meetings with presidents and military commanders. But the U.S. Treasury Department and experts who track Mr. Prigozhin’s activities say that he owns or controls most, if not all, of the companies that make up Wagner.

And as his operations in Sudan show, those companies have left a paper trail.

Russian and Sudanese customs and corporate records, obtained through the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, a nonprofit in Washington, as well as mining documents, flight records and interviews with Western and Sudanese officials, reveal the extent of his business empire in Sudan — and the particular importance of gold.

The Wagner Group has “spread a trail of lies and human rights abuses” across Africa, and Mr. Prigozhin is its “manager and financier,” the State Department said in a statement on May 24.

Most officials spoke about Mr. Prigozhin and Wagner on the condition of anonymity, citing the confidentiality of their work or, in some cases, fears for their safety. General Hamdan and Mubarak Ardol, Sudan’s state regulator for mining, declined to be interviewed.

In a lengthy written response to questions, Mr. Prigozhin denied any mining interests in Sudan, denounced American sanctions against him and rejected, with a hint of a wink, the very existence of the group he is famously associated with.

“I, unfortunately, have never had gold mining companies,” he said. “And I am not a Russian military man.

“The Wagner legend,” he added, “is just a legend.”

The ‘Key to Africa’

Wagner’s operations in Sudan began in 2017 after a meeting in the Russian coastal resort of Sochi.

After nearly three decades of autocratic rule, President Omar Hassan al-Bashir of Sudan was losing his grip on power. At a meeting with Mr. Putin in Sochi, he sought a new alliance, proposing Sudan as Russia’s “key to Africa” in return for help, according to the Kremlin’s transcript of their remarks.

Mr. Putin snapped up the offer.

Within weeks, Russian geologists and mineralogists employed by Meroe Gold, a new Sudanese company, began to arrive in Sudan, according to commercial flight records obtained by the Dossier Center, a London-based investigative body, and verified by researchers at the Center for Advanced Defense Studies.

The Treasury Department says that Meroe Gold is controlled by Mr. Prigozhin, and it imposed sanctions on the company in 2020 as part of a raft of a measures targeting Wagner in Sudan. Meroe’s director in Sudan, Mikhail Potepkin, was previously employed by the Internet Research Agency, the Prigozhin-financed troll factory accused of meddling in the 2016 United States election, the Treasury Department said.

Meroe Gold’s geologists were followed by Russian defense officials, who opened negotiations over a potential Russian naval base on the Red Sea — a strategic prize for the Kremlin, suddenly within reach.

Over the next 18 months, Meroe Gold imported 131 shipments into Sudan, Russian customs records show — mining and construction equipment, but also military trucks, amphibious vehicles and two transport helicopters. One of the helicopters was photographed a year later in Central African Republic, where Wagner fighters were protecting the country’s president, and where Mr. Prigozhin had acquired lucrative diamond mining concessions.

Incongruously, the shipments also included a vintage American car — a 1956 Cadillac Series Sixty-Two, documents show.

But the Russians soon found themselves advising Mr. al-Bashir on how to save his skin. As a popular revolt surged from late 2018, threatening to topple his government, Wagner advisers sent a memo urging the Sudanese government to run a social media campaign to discredit the protesters. The memo even advised Mr. al-Bashir to publicly execute a few protesters as a warning to others.

This memo and other documents were obtained by the Dossier Center, which is financed by Mikhail B. Khodorkovsky, a former oil oligarch and a longtime nemesis of Mr. Putin’s. Through interviews with officials and business leaders in Sudan, The New York Times confirmed key information in the documents, which the Dossier Center said were provided by sources inside the Prigozhin organization.

When Mr. al-Bashir was ousted by his own generals and placed under house arrest in April 2019, the Russians swiftly changed course.

A week later, Mr. Prigozhin’s jet arrived in Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, carrying a delegation of senior Russian military officials. It returned to Moscow with senior Sudanese defense officials, including a brother of General Hamdan, who was then emerging as a power broker, according to flight data obtained by the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta.

Six weeks later, on June 3, 2019, General Hamdan’s troops launched a bloody operation to disperse pro-democracy protesters from central Khartoum in which at least 120 people were killed over the next two weeks. On June 5, Mr. Prigozhin’s company, Meroe Gold, imported 13 tons of riot shields, as well as helmets and batons for a company controlled by General Hamdan’s family, customs and company documents show.

Around that time, a Russian disinformation campaign using fake social media accounts sought to exacerbate political divisions in Sudan — a technique similar to the one used by the Internet Research Agency to meddle in the 2016 U.S. election. Facebook shut down 172 of those accounts in October 2019 and May 2021, linking them directly to Mr. Prigozhin.

But neither those measures nor the American sanctions deterred the Wagner Group from its main goal — capturing a slice of Sudan’s gold boom.

The Gold Miners

Poor men hoping to strike it big stream to al-Ibediyya, the gold mining town north of Khartoum, on the banks of the Nile.

After hacking gold-rich rock from the desert, they bring it to be crushed at the town’s ramshackle market, extracting gold using a crude, mercury-based technique that poses great risks to their health.

But far greater profits can be earned by running the same ore through a second, more complex gold extraction process at a cluster of industrial plants 10 miles away. One of the largest is run by Meroe Gold.

In interviews, traders described how Russians come to the market to take samples and buy gold ore, paying up to $3,600 for a nine-ton truckload. Sometimes, they said, the Russians were protected by troops from General Hamdan’s Rapid Support Forces.

When a team from The Times approached the gate of the Meroe plant, Ahmed Abdelmoneim, a Sudanese engineer, wanted to be helpful. About 30 Russians and 70 Sudanese worked there, he said, motioning to the living quarters, workshops and gleaming metal towers. The Russians were unlikely to speak with a reporter because of the company’s reputed “link to Wagner,” which he dismissed as untrue.

Before he could elaborate, a message in Russian crackled over the radio. A small bus pulled up outside, driven by an athletic-looking white man who wore shorts, sunglasses and a khaki-green T-shirt. He avoided eye contact with our team.

The bus drove away with Mr. Abdelmoneim, and we were invited to leave.

Gold production in Sudan soared after 2011, when South Sudan seceded and took with it most of its oil wealth, but only a handful of Sudanese have gotten rich. General Hamdan’s family dominates the gold trade, experts and Sudanese officials say, and about 70 percent of Sudan’s production is smuggled out, according to Central Bank of Sudan estimates obtained by The Times.

Most of it passes through the United Arab Emirates, the main hub for undeclared African gold. Western officials say that Russian-produced gold has likely been smuggled out this way, allowing producers to avoid government taxes and possibly even the share of the proceeds that is owed to the Sudanese government.

“You can walk into the U.A.E. with a handbag full of gold, and they will not ask you any questions,” said Lakshmi Kumar of Global Financial Integrity, a Washington-based nonprofit that researches illicit financial flows.

Halting the flow of Russian gold has become a priority for Western governments. In March, the Treasury Department threatened sanctions on anyone who helps Mr. Putin launder the $130 billion stash in Russia’s central bank.

Some Sudanese gold might be going directly to Moscow.

From February to June 2021, Sudanese anticorruption officials tracked 16 Russian cargo flights that landed in Port Sudan from Latakia, Syria. Some flights, operated by the Russian military’s 223rd Flight Unit, originated near Moscow. The Times was able to verify most of those flights using flight-tracking services.

Suspecting the planes were being used to smuggle gold, the officials raided one flight before it took off on June 23. But as they were about to break open its cargo, a Sudanese general intervened, citing an order from Sudan’s leader, General al-Burhan, said a former senior anticorruption official who spoke on the condition of anonymity to avoid reprisals.

The plane was moved to the military section of the airport, he said, and left for Syria a couple of hours later without being searched.

The anticorruption body, set up to dismantle Mr. al-Bashir’s network inside Sudan, was disbanded five months later, after October’s military coup.

General al-Burhan declined to be interviewed for this article. Lt. Gen. Ibrahim Gabir, a fellow member of the ruling Sovereignty Council, played down accounts of Russian smuggling.

“People are talking,” he said. “But you need evidence.”

From Russia With Cookies

Since 2016, the United States has imposed no fewer than seven rounds of sanctions on Mr. Prigozhin and his network, and the F.B.I. is offering a $250,000 reward for information leading to his arrest. Those measures have done little to stem his expansion in Africa, where he sometimes feels emboldened to flaunt his ties.

In a splashy bid for Sudanese support, Mr. Prigozhin donated 198 tons of food to poor Sudanese last year during the holiday month of Ramadan. “A gift from Yevgeny Prigozhin,” read the packets of rice, sugar and lentils, under a slogan that recalled the depths of the Cold War: “From Russia With Love.”

The donation, made through a subsidiary of Meroe Gold, included 28 tons of cookies that had been specially imported from Russia. “They were meant for children, but everyone enjoyed them,” said Musa Gismilla, the head of the Sudanese charity that distributed the aid.

But there was a hitch. Mr. Prigozhin insisted on diverting 10 tons of the food to Port Sudan, where Russia was lobbying for naval access, instead of to more needy regions. Mr. Gismilla was disturbed.

“It suggested the gesture was more about politics than humanitarianism,” he said.

In his response to The Times, Mr. Prigozhin wrote that he had “nothing to do with Meroe Gold,” yet added that he had learned that the company was “currently in liquidation.”

He confirmed the charity donation, which he said was at the behest of a Sudanese woman with whom he had “friendly, comradely, working and sexual relations” — apparently a mocking explanation most likely to cause particular offense in a conservative Muslim society.

Wagner’s main military ally in Sudan, General Hamdan, is also reaching for public support. Since betraying his onetime patron, Mr. al-Bashir, in 2019, General Hamdan has sought to distance himself from his reputation as a ruthless commander in the Darfur conflict that led to an estimated 300,000 civilian deaths in the 2000s.

Instead, Mr. Hamdan has signaled his ambition to lead Sudan, building a support base among traditional leaders he has courted using money and vehicles, diplomats said, and with friendly foreign powers like Russia.

Two senior Western officials said that Wagner organized General Hamdan’s February visit to Moscow, where he arrived on the eve of the war in Ukraine. Although the trip was ostensibly to discuss an economic aid package, they said, General Hamdan arrived with gold bullion on his plane, and asked Russian officials for help in acquiring armed drones.

On his return to Sudan a week later, General Hamdan announced that he had “no problem” with Russia opening a base on the Red Sea.

Supporting a Coup ‘to Steal Gold’

The murkiest part of Wagner’s Sudan drive is in Darfur, a region riven by conflict and rich in uranium. There, Russian fighters can slip into bases controlled by General Hamdan’s Rapid Support Forces, Western and United Nations officials say — and sometimes use the bases to cross into Central African Republic, Libya and parts of Chad.

This year, a team of Russian geologists visited Darfur to assess its uranium potential, one Western official said.

Since the war in Ukraine began, Russian disinformation networks in Sudan have churned out nine times as much fake news as before, trying to generate support for the Kremlin, said Amil Khan of Valent Projects, a London-based company that monitors disinformation flows.

That message is not welcomed by everyone. Several protests against Meroe Gold operations have erupted in mining areas. A Sudanese YouTube personality known only as “the fox” has attracted large audiences with videos that purport to lift the lid on Wagner’s activities. And pro-democracy demonstrators theorize that Moscow was behind last October’s military takeover of the Sudanese government.

“Russia supported the coup,” read an unsigned poster that appeared in Khartoum recently, “so it could steal our gold.”

Police. (photo: ChiccoDodiFC/Shutterstock)

Police. (photo: ChiccoDodiFC/Shutterstock)

The fear of most Black parents is now shrouded in a double threat of potential harm.

Shane Paul Neil, a 44-year-old father of two thought of his own children as most parents did, in the days following the massacre of 19 children at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde. As he grappled with the possibility of a double threat in his children’s schools — increased chances of random gun violence, as well as racial profiling by police — he voiced his fears online in a tweet that has now gone viral. “As a black father I now have two potential threats to be concerned over.”

“For White parents it was, ‘we don’t want to bring more guns into school,’” he told The Washington Post. “For myself and other Black parents, it’s that we don’t want to force police interaction in school with our children in particular.”

Statistics show that Black and Latin X students are suspended and expelled at significantly higher rates than their white peers. They are also most likely to be arrested both in and outside of the classroom, at times leaving them with a record that stays with them into their adulthood. “It only takes one incident for my son or daughter to have an arrest record, a juvenile record,” Neil says, “and those things stick with you, they follow you.”

For Natalie Moss, the mother of two preschool aged children, the thought of turning teachers into “de facto law enforcement” doesn’t sit well with her and her husband. “There’s a culture of adultification bias against Black children,” she says. “They’re cute when they’re 2 or 3. But when they reach a certain height, it’s different. My child is in the 99th percentile for height — he’s on par with most 6-year-olds in terms of height, so when people approach him, they often think he’s older than he is, already.”

Moss also speaks on the history of distrust between the police and oppressed people as it relates to the unfolding details and changing stories from the officers present that day in Uvalde.

“I think that what people have to pay close attention to is how these changing stories bring distrust in law enforcement, particularly in the African American community as well as communities of color,” Moss says. “I have all these questions. How do I know what’s true and what’s not? As a Black parent, what about any of this would evoke any level of confidence that more police would benefit my Black sons?”

Beatriz Beckford, national director of the social welfare organization Moms Rising charges us all to be more imaginative when it comes to the consideration of public safety. “There’s not enough space to dream beyond a world where we rely so heavily on police for everything,” she says. “We rely on them to discipline in the classroom. We rely on them to intervene when there’s a mental health crisis.” We must find the balance. Our lives, and the lives of future generations depend on it.

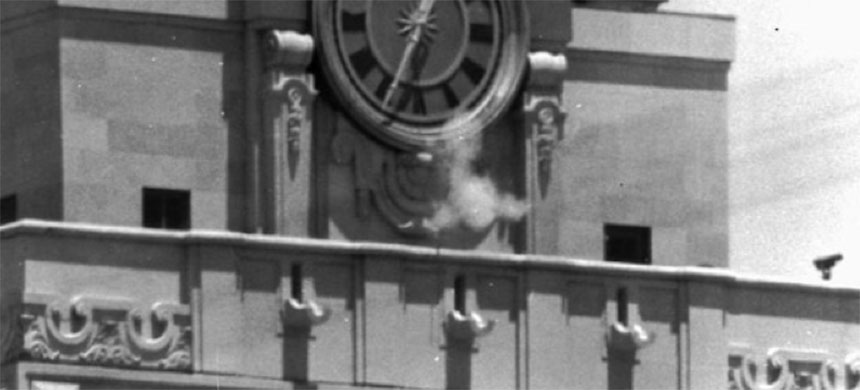

A puff of smoke from sniper Charles Whitman's rifle emerges from the observation deck of the Tower at the University of Texas at Austin on Aug. 1, 1966. Whitman killed 16 people and wounded 31 before being fatally shot by police. (photo: AP)

A puff of smoke from sniper Charles Whitman's rifle emerges from the observation deck of the Tower at the University of Texas at Austin on Aug. 1, 1966. Whitman killed 16 people and wounded 31 before being fatally shot by police. (photo: AP)

In 1966, we had no idea this school massacre would be just the first

Raised by a brutal, damaged father who taught him to shoot — and shoot well — before he was school age, Charlie did not “depart from it.” I was in a Shakespeare class at the University of Texas in Austin on Aug. 1, 1966, when Whitman, by then 25, took his weapons and his torments to the top of the university’s Main Building and from its clock tower became the first modern entry on a uniquely American timeline of what we now call mass shooters. All together, he killed 15 people and wounded 31, many grievously, including a man who died decades later of the injuries he suffered.

Those of us forced to witness the carnage, who hid from the crosshairs of Whitman’s sniper scope and stepped around puddles of blood that darkened in the hot sun before it was finally over, cannot forget even if we wanted to. The shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde is both its own distinct nightmare and simply the latest reminder.

“Tell me, hon,” Whitman’s father, also Charles, said to me in 1976, when I interviewed him for a story on the anniversary of the shootings. “How do they feel about this in Austin 10 years later? Do they blame the family? Or do they think Charlie was just sick?”

Here’s one thing nobody was thinking back then — that we would still be having these conversations 56 years later. The Vietnam War was barely underway in 1966. We’d never heard of military-style weapons in the hands of civilians. We thought Whitman was an aberration. But “what began on the UT campus two generations ago has never ended,” as a recent essay in the Texas Tribune put it. “It’s been repeated again and again.”

Yet mass shootings did pause, in Texas and elsewhere, for many years. One thing that changed was the weaponry. In 1989, a suicidal angry drifter with an AK-47-style rifle killed five and wounded 32 at an elementary school in Stockton, Calif. The outcry prompted California and later Congress to ban such weapons. The federal ban ended in 2004.

In a way, Whitman was an anomaly compared to later shooters — an older, former Marine sharpshooter who picked off his victims one by one with a Remington 700 bolt-action rifle, a classic hunting (and sniper) weapon that in skilled hands can fire up to 10 rounds a minute. For boys taught to hunt like he was, skill was key. It was a point of pride to make the first shot the killing shot, so the animal wouldn’t get far or needlessly suffer.

My cousin Blaine Bennett, who grew up in Uvalde and still lives there, remembers once asking his father for more capacity for his deer rifle. It held three bullets, and he wanted five. My uncle refused. “His reasoning was if I hadn’t dropped that deer in three shots, then I was just a bad shot,” Blaine recalled. “In fact, his expectation for me was one shot.” My cousin was 8 at the time.

Old-school Texans like him are repelled by the idea that anyone, much less teenagers, as the shooters in Uvalde and Buffalo and Parkland were, can easily buy and wreak havoc with weapons that are designed to tear apart scores of human bodies within seconds and cause maximum suffering. Gun advocates deride the “spray and pray” reputation of the AR-15 as a myth but it’s capable of firing six times as many rounds a minute as a bolt-action rifle.

However, if the Tower shootings were an aberration, they were also a template for the mass slayings that followed. We know the script by heart. There will be shock and horror and mourning of senseless deaths. Interviews with survivors and relatives of victims and shooters. Photographs of those who were slain and their funerals. GoFundMe pages. Gun debates. Much talk about a mental health crisis. Explosive news conferences about what went wrong, because something always goes wrong, whether it’s before, during or after the shooting or all three.

When I dragged my two dusty boxes of Whitman sniper files from my garage and paged through the yellowed copies of the Aug. 1 police reports, I was struck by the echoes of Uvalde in the chaos and terror of that afternoon in Austin. In a way mass shootings are like war, difficult even for cops to comprehend unless they’ve been there.

Houston McCoy was a military veteran, perhaps the first police officer to arrive at the Tower after the shooting began. His handwritten account of that afternoon, the adrenaline and confusion and fear, is remarkable for its plain-spoken honesty. “Grab my shotgun, look for an entrance. Don’t see one, look toward the top and see all the windows. Feel like there is somebody with a gun behind each window, get scared, run back to my (police car).”

The endless hash and rehash of what the “good guys” did or didn’t do in Uvalde is an old story. There will always be lapses and mistakes and missed warning signs, despite the shooter drills and training and fancy equipment that are supposed to avoid them. When Whitman told a doctor at the student health center about his urge to take a deer rifle to the top of UT’s Main Building and shoot people, the doctor took notes but did nothing except schedule him for another appointment. Whitman never showed. The unarmed campus cop on guard duty when Whitman drove on campus could have checked his claim that the footlocker in his back seat contained equipment for the science building. It actually contained his arsenal. But there was no reason in 1966 to be suspicious of this young man.

The rapid shots from the observation deck were ringing above their heads as McCoy and other officers got the word to converge near the Tower. McCoy thought, “Oh boy, someone has finally come up with a plan,” he later recounted. But there was no plan. Almost an hour would pass before he and Officer Ramiro Martinez felled Whitman in a helter-skelter rush to the observation deck, an hour in which the body count rose. Though he was a hero that day, McCoy blamed himself for those bodies for the rest of his life.

That’s the trouble with trauma, as the survivors and the bereaved in Uvalde are learning, like all the others who came before. It ripples through people and communities and even generations endlessly, never reaching the shore where it can spend itself for good. Losing any loved one is hard, but losing your child is particularly devastating. As I learned when talking to survivors of the Tower shootings many years later, those traumas can upend lives, destroy marriages, rip apart families.

Those of us who were there in 1966 are in our 70s and 80s now. We've lived long enough to die of natural causes. It’s our grandchildren who are having shooting drills in school. Grandchildren who were shot to pieces in Uvalde, who will be shot to pieces somewhere else. There have been worse mass shootings in terms of numbers, but there’s something unbearable about those young faces, row upon row of them, looking so hopefully at the camera when they were alive.

What was an unprecedented massacre on a placid college campus has repeated itself for two generations and counting. An endless loop, therefore a predictable one, abetted by unspeakably deadly weapons that almost anyone can buy, anywhere. We didn’t know that going in, in 1966. But every decade since, we’ve learned. We’ve learned.

Over the past decade, the ACLU lawyer has been mounting an all-angles 24/7 defense of LGBTQ+ rights. (photo: Hunter Abrams/The Advocate)

Over the past decade, the ACLU lawyer has been mounting an all-angles 24/7 defense of LGBTQ+ rights. (photo: Hunter Abrams/The Advocate)

Over the span of his career, Strangio has gone from an underpaid, overworked lawyer at an LGBTQ+ legal aid organization focused on direct services for queer and trans New Yorkers to a better-paid, still overworked lawyer working on cases that impact LGBTQ+ communities at large in the nation’s highest courts. In tandem with the growth of his professional profile as a civil rights advocate, Strangio has leveraged his own celebrity along with the profiles of well-followed friends to shift public consciousness: appearing on the Emmys red carpet with Laverne Cox, raising $3 million in partnership with Ariana Grande, and hosting a series of Instagram lives. It’s an all-angles, 24/7 defense of LGBTQ+ rights at a time when trans rights specifically are the ones most directly under attack.

Again, though, that’s just how he’s always appeared to me, whichever screen I saw him on. I don’t actually know who Chase Strangio is, despite being briefly introduced through a mutual friend at a screening of Lizzie Borden’s Working Girls that we all happened to be at a few years ago. I’ve technically spent hours on the phone talking to him, but always in the context of me being a journalist and him being an authoritative source on whatever I happened to be covering: an anti-trans sports bill here, an anti-trans order from the Trump administration there. But beyond those mutually transactional encounters, the man has always been a total mystery.

“One of my few criticisms of Chase is that he is so dedicated, he doesn’t take breaks when he needs to,” Chelsea Manning, the security consultant whom Strangio represented after she was incarcerated for leaking classified government documents, tells me. “He is so dedicated to the work that he does, and I think that’s why his social life is so diminished.”

On a sunny Tuesday morning in early May, I arrived on set for Strangio’s cover shoot, ready to meet the man behind all the advocacy. We were at New York City’s Stonewall Inn—not just the site of the famed 1969 uprising against police brutality but a bar, the kind of place people might go to in order to kick back, have fun, and not check their work email for a few hours.

“Is this the first time in a while you’ve been in a bar?” I ask once the camera’s initial clicks subsided. “I interviewed Chelsea Manning, and she said you’re so dedicated to your job that you don’t go out much.”

“I’m not that dedicated!” he responds in mock outrage. “I mean, that’s been hard during COVID. Everything feels different, but I still try to integrate some spaces into my life that are not about work. What’s also hard in this moment is that whenever I go to places that are very queer, the likelihood of being recognized is much higher than if I went to some straight bar where no one knew who I was.”

I sarcastically suggest that he could try going to straight bars.

“I guess there are options,” he laughs. “But yeah, I don’t know that I’ve done the best job over the last decade in creating systems of rest and relaxation for myself.”

“But I have been to a bar.”

Hailing from Newton, Mass., Strangio began his legal career shortly after graduating from Northeastern University School of Law in 2010. He worked as a lawyer at New York City’s Sylvia Rivera Law Project, where he had interned one year prior. Working under the legal aid organization’s founder, Dean Spade, whose vision he very much admired, Strangio represented trans folks incarcerated in New York state prisons and jails. Another influential figure was the late community organizer Lorena Borjas, with whom he created a now-defunct cash bail fund. “Lorena was a very frequent guest and comrade who would come into the office and push us to do more for the trans Latina community in Queens,” he says.

Burned out by what he felt were the limitations of working at a small nonprofit — not to mention stressed over student loans and the cost of starting a family — he took a job as a staff attorney at the ACLU in 2013. Though the world of impact litigation proved a steep learning curve, Strangio gradually established himself as a leading figure in the legal battle over LGBTQ+ civil rights. Even if you somehow haven’t heard of him, you’re definitely familiar with the cases he’s argued. He represented Manning during her final three years in prison for disclosing military intel to WikiLeaks, sex work activist Monica Jones, and embattled trans student-turned-activist Gavin Grimm. As a litigator, he also on worked Obergefell v. Hodges, which produced the 2015 Supreme Court decision legalizing same-sex marriage across the United States; 2016’s Carcaño v. McCrory (later Carcaño v. Cooper), which led to the repeal of North Carolina’s infamous law restricting trans people’s public bathroom access; and Aimee Stephen’s case which was combined with two others in Bostock v. Clayton County, where the Supreme Court ruled in 2020 that Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act protects LGBTQ+ workers from employment discrimination.

In the two years since Bostock, Strangio’s legal work and advocacy have focused largely on the growing number of anti-trans laws pushed forth by state legislatures nationwide. Lawmakers filed a record number of anti-trans bills in 2020 only to break that record the following year, introducing 150 pieces of legislation that would make trans people’s lives—and those of their accepting parents and medical providers—needlessly difficult, if not fully criminalized. We’re not even halfway through 2022, and already we’re on track to break that record again, with 140 bills filed by mid-May alone.

“This is the third year where we’re seeing this incredibly intense attack against trans people, but particularly trans youth,” says Cathryn Oakley, state legislative director and senior counsel at the Human Rights Campaign. “The folks pushing these bills are the same opponents of LGBTQ equality we’ve had for decades: the Heritage Foundation, the American Principles Project, the Alliance for Defending Freedom—same old, same old. Their goal is to stop LGBTQ equality at any cost. They tried with marriage, it didn’t work. They tried with bathrooms, it didn’t work. They’ll try anything they can to get a foothold and start pulling back LGBTQ equality.”

As deputy director for trans justice with the ACLU’s LGBT & HIV Project, a position he has held since 2019, Strangio is currently involved in “a million cases,” by his count. One of them involves an Arkansas state law passed in 2021 that would have prohibited trans youth from receiving gender-affirming health care of any kind. The ACLU challenged it, prompting a federal judge to issue a temporary injunction, thereby preventing an untold number of trans kids in the state from being medically detransitioned against their will. “We are preparing for a trial in October,” Strangio says.

In Texas, he is involved with a case pertaining to Gov. Greg Abbott’s directive issued earlier this year ordering the state’s Department of Family and Protective Services to investigate the families of trans kids, cravenly calling the provision of lifesaving gender-affirming medical care “child abuse.” The case is spurring New York Times push alerts, and in addition to being in hearings, Strangio can be often found making corrections or bringing context to headlines on Twitter. There’s another case in Idaho, which passed a sports ban on trans students in the early months of the pandemic. And then there’s Connecticut: in Soule et al v. Connecticut Associations of Schools et al, involving three white cis girls—represented by the Alliance Defending Freedom—who were so upset over having to compete alongside two Black trans girls, they sued their state, claiming that its trans-inclusive policy for publicly funded athletics violated their rights under Title IX. “The cis girls are fine, of course,” Strangio says. “They went on to receive athletic scholarships, even though their whole argument was based on the claim that they couldn’t because their opportunities were supposedly compromised.”

“I was really hoping that this year was going to be different, and it’s just the worst,” he says.

Outside of the courtroom, Strangio works overtime in his attempts to get the public to understand the battle raging inside it, making appearances on Democracy Now! and The Rachel Maddow Show as well as utilizing Twitter and Instagram to shape the public narrative in trans people’s favor.

“Chase is such a legal mastermind,” says Raquel Willis, a writer and activist who launched the annual Trans Week of Visibility and Action with him last year. “Chase is one of the fiercest defenders of bodily autonomy and self-determination that we have on a national level. He can get such crucial and often inaccessible understandings of legislation to our community. He is also a powerful strategist who spends most of his days figuring out how to preserve, protect, and demand more on behalf of our people.”

But it’s not just at the macro level: Manning spoke with me about how Strangio helped care for her after she got out of prison. The two of them spent the first week immediately following her release at a safe house in an undisclosed location in upstate New York. “I have no idea where it was to this day,” she explains. She’d always felt safe with him, always trusted him. Unlike the “white shoe” lawyers who came before him, he never made her feel like she had to explain herself to him or defend why she wanted the things that she did, like access to hormone replacement therapy while she was incarcerated. The week upstate was no exception. Thanks to Strangio’s help, Manning was able to re-enter the outside world with no reporters, no phones, and no spotlight glaring down on her. “Just chill vibes only,” she recalls. “There was a sound system. We’d just jam out to pop music,” a lot of EDM, drum and bass, rave music, and Selena Gomez—her picks, not his. He later helped her get her first debit card in years, changing her name and updating her account information.

“It was this life-changing moment, being able to access my own money again,” she says. “I didn’t have to ask people for money to go to the store. It had been so long. [Even after my release and the week upstate,] I was basically trapped for about 10 days without access to my own money. He helped me solve that.”

Throughout my interviews, I thought about something Laverne Cox had told me over the phone. The Emmy-winning actress, who recently starred in Netflix’s Inventing Anna, said that she often reaches out to Strangio before doing an interview. “Chase is truly the most important legal mind in the United States when it comes to trans issues,” she told me, adding that he always knows exactly how to distill even the most complicated legal matter into digestible talking points that she can mention during interviews.

While my own conversations with Strangio had felt intimate, more like talking to a new friend than an interview subject at times, they were still opportunities to convey some sort of messaging to the public—but then, what?

A few days after the Stonewall photo shoot, I meet him at the two-bedroom apartment in Queens that he shares with his kid, when they’re not with their other parent. It was sparsely decorated: Precious Brady-Davis’s I Have Always Been Me and Shon Faye’s The Transgender Issue faced outward on a built-in shelf, resting beside a draped Pride flag; magnetic poetry on the fridge arranged to spell out “LGBTQ” in big letters; the record sleeve for Janet Jackson’s “Nasty” propped up on the air conditioner; very little of anything on the walls. The two of them have lived here for about a year and a half, but—surprise—he’s been too busy to fully figure out the decor.

Something he has fully figured out might be alarming for some, especially from the one-man, never-sleeping, trans rights defender himself.

“We’re not going to see any wins like we did with Obergefell or Bostock,” he says. “The courts have changed significantly. We have to contend with reality.” The same applies to federal legislation, he adds, like the seemingly doomed Equality Act. “We’re not going to see that type of transformative structural change in the coming years. In fact, we’re more likely to see further regression and backlash.”

When Arizona introduced a bathroom bill way back in 2013, “there was a sense that it was beatable,” he continues. “Beatable in the sense of using law as a tool.” But there’s been a domino effect ever since the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act that same year. That decision in Shelby County v. Holder enabled rampant voter suppression and gerrymandering of districts, “which is impacting whether and how you can beat things in state legislatures,” Strangio says. “If in a state like Arkansas you have three people in the whole legislature who are even mildly supportive of trans rights, it’s really hard to stop anti-trans bills.” Defending trans rights through the courts is equally daunting thanks to the 200-plus federal court judges appointed by former President. Donald Trump. Even if the ACLU, for example, were able to get a case involving trans rights before the conservative-majority Supreme Court, it’ll likely fare no better than the fate Roe v. Wade appears headed for.

So why is he a lawyer if he doesn’t believe that the law will ever truly save the community he spends all his time defending? “For me, it’s the time,” he explains. “I see it as a form of harm reduction—a delaying tool that gives people more time to mobilize, to build resources, and transform our living conditions in more meaningful ways than the law will ever allow.”

Although he’s not an optimist, he’s no nihilist either. Strangio does believe that we should keep organizing and pushing lawmakers to cancel student loan debt, expand health care, and provide other basic necessities. He also believes that we should intervene wherever we encounter anti-trans antagonism, whether that’s with friends and family or with our state and local governments. “Constituent contact is consistently the most effective way to kill a bill—I mean, other than being a corporation and buying off politicians,” he says. “Even if you live in a state where these things aren’t happening, you can organize and run call-in programs, calling voters to connect them to their lawmaker.”

“We’re going to be living in different times of extralegal care networks,” he continues. “People should be prepared to think about how they’re going to get access to medication, how they’re going to get involved to get other people what they need whether that’s Plan B, birth control, the abortion pill, hormones, puberty blockers. How are we collectivizing our access to care and redistributing it?”

As Strangio answered my questions on his expansive L-shaped couch, lounging cross-legged in a Boba Fett hoodie and Adidas cap, I realized how many things were competing for his attention: the notifications on his phone, which he frequently checked without pausing our interview; his black cat, Raven, who kept trying to drink out of our water glasses. About half an hour in, his apartment buzzer rang. The dinner he’d ordered for him and his kid had arrived. After giving his kid a plate in another room, he’d occasionally interrupt himself to check to see if they’d finished their salad, if they wanted another slice of pizza, before getting back to whichever of my questions he’d started answering.

“National efforts like passing the Equality Act or codifying Roe — those are fine things, but Congress is not going to do it because federal legislation is a huge resource demand with low reward at this point, and it’s just going to get challenged in court,” he says. “I was at these two big LGBTQ organization events in the last 10 days—the GLAAD Media Awards and the Ali Forney Center gala. There’s this drive for simple narratives at these events, so much talk about Disney and the ‘don’t say gay’ bill in Florida — which wasn’t just about gay people — and I’m like… this is how we got ourselves here! I get that people’s capacity is so limited, but we just have to be able to hold more nuance. I’m also like—hey! Raven!”

His cat had started tearing up the side of the couch.

“I got you these scratching things!” he says, pointing to the nearest one. “Cats are so demonic, but, like, I chose to get him.” He picked up his cat and cradled him, talking to Raven in the sing-songy, cutesy baby voice in which most pet owners are fluent. “And he’s going to scratch fu-u-urnitu-u-ure, which is why I don’t even have nice thi-i-ings, so it’s fi-i-ine.” Another problem dealt with—now onto the other 87.

The UN, along with the African Union and regional grouping IGAD, has been pushing for Sudanese-led talks to break the post-coup political impasse. (photo: Mahmoud Hjaj/Anadolu Agency)

The UN, along with the African Union and regional grouping IGAD, has been pushing for Sudanese-led talks to break the post-coup political impasse. (photo: Mahmoud Hjaj/Anadolu Agency)

A protester was killed during Friday’s demonstrations despite UN calls for security forces to ‘refrain from excessive violence against protesters’.

Sudan has been rocked by deepening unrest and a violent crackdown against near-weekly mass protests since army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan’s power grab on October 25 derailed a fragile transition to civilian rule.

“It is simply unacceptable that 99 people have been killed and more than 5,000 injured as a result of excessive use of force by the joint security forces,” Adama Dieng told reporters on Saturday, quoting a toll provided by pro-democracy medics.

He called on authorities “to expedite” investigations into the killings of protesters.

On what is his second visit to Sudan since last year’s coup, Dieng raised concerns during talks with senior officials over arbitrary and mass arrests of activists, sexual and gender-based violence, and “acts of torture and ill-treatment” during detentions.

He said an inquiry set up by Sudanese authorities has confirmed “four cases of sexual violence” during the protests.

The UN expert also pointed to an intensification of an existing economic crisis since the coup, which has seen Western donors return to the sidelines, after a brief engagement with a civilian-military power-sharing government established in the wake of the deposing of President Omar al-Bashir in 2019.

Spiralling prices and a poor harvest are “forecast to dramatically increase the number of people living in poverty”, he noted.

Dieng is scheduled to meet al-Burhan later on Saturday.

On Friday, thousands of protesters took to the streets across Sudan to mark the third anniversary of a crackdown that medics say killed 128 people in June 2019, when armed men in military fatigues violently dispersed a weeks-long sit-in outside army headquarters.

A protester was killed during Friday’s demonstrations despite calls by Dieng, echoed by Western diplomats, for security forces to “refrain from excessive violence against protesters”.

The UN, along with the African Union and regional grouping IGAD, has been pushing for Sudanese-led talks to break the post-coup political impasse.

On Friday, UN special representative Volker Perthes announced the Security Council had voted to extend by one year the UN’s mission in Sudan.

Perthes, as well as AU and IGAD representatives, agreed with military officials to launch “direct talks” among Sudanese factions next week.

On Sunday, al-Burhan lifted a state of emergency in force since the coup to set the stage for “meaningful dialogue that achieves stability for the transitional period”.

Since April, Sudanese authorities have released several civilian leaders and pro-democracy activists.

The Alps, pictured here behind Balzers, Liechtenstein, are getting greener as warmer temperatures lead to a decline in snow. (photo: Diego Grandi/Alamy)

The Alps, pictured here behind Balzers, Liechtenstein, are getting greener as warmer temperatures lead to a decline in snow. (photo: Diego Grandi/Alamy)

The European mountain range is seeing less snow and more vegetation, leading to concerns about drinking water and rising temperatures.

In a study published Thursday in the journal Science, researchers report that a process called “greening” is occurring over large swaths of the Alps. While this term is sometimes used to refer to making a space more environmentally friendly, in this case, it refers to an increase in plant growth and spread which can accelerate climate change.

Greening can potentially cause a few positive consequences, but the negative consequences outweigh these effects, said Sabine Rumpf, the study’s first author and a professor at the University of Basel in Switzerland.

This phenomenon is occurring across 77 percent of the European Alps above the tree line — the edge of alpine habitats where trees stop growing. An earlier estimate reported this was happening in just 56 percent of the region.

Rumpf and her colleagues also found that snow cover has declined significantly in 10 percent of the Alps. These figures are based on an analysis of 38 years of data. The scientists evaluated information captured by the Landsat Missions, a group of eight Earth-observing satellites that use remote sensors to collect data. Instead of looking at images, the team used this data to calculate the spread of snow cover and vegetation productivity.

While 10 percent may sound small, the potential impact is large. Beyond playing an important role in ecosystems, snow is essential for people as a source of drinking water. The Alps are the highest and most extensive mountain range entirely in Europe. Forty percent of Europe’s drinking water stems from this area. This is why the Alps are called the “water towers” of Europe, Rumpf said.

A reduction in snow does not mean there will be less drinking water available tomorrow, but it does suggest a concerning long-term trend, she explained.

One issue with climate change, Rumpf said, is that by now most people are aware of it but “the consequences of our actions are decoupled from our everyday life.” Most people do not see the results of the crisis immediately.

“We hear about it, we see numbers, but these facts can feel removed,” she said. “My hope is that these very striking effects — which are now actually visible from space — might be easier for people to grasp, rather than findings concerning how much carbon dioxide we have in the atmosphere.”

Carbon dioxide definitely plays a role. Mountain regions, which are hot spots for biodiversity, are warming about twice as fast as the global average. This warming drives greening and the subsequent increase in vegetation pushes the cycle forward. Taller and denser plant life in areas where this isn’t the norm can put alpine plant and animal communities at risk and release further greenhouse gases through the melting of permafrost.

Greening can also prevent snow cover, and less snow harms an area’s ability to reflect solar radiation — energy that comes to the Earth from the Sun. An inability to reflect this energy contributes to overall warming.

“Snow reflects about 90 percent of it back,” Rumpf said. “When we have less snow, we keep more of this energy.”

Alexander Winkler, a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, was not a part of this research but also studies how climate change affects vegetation. Beyond greening, there is also browning — this is when plants die, something his research shows is happening in tropical regions. Beyond the Alps, greening is well-established in the Arctic, a reality some experts say should be viewed as a bellwether of global climate change.

“The vegetation trends are now well-known among the scientific community but are certainly underappreciated phenomena among the public,” he said.

When he speaks to people about greening as a response to carbon dioxide emissions and human-caused climate change, the response Winkler often gets is: “So that’s a good thing, right?”

Not necessarily, he said. While plants can absorb and store atmospheric carbon dioxide, which can help combat climate change, the other costs are severe.

Rumpf agrees. “It’s also important to remember that the carbon dioxide absorbed by plant biomass is not stored for eternity and taken out of the system,” she said. “It gets recycled and enters the system again. It’s not truly gone.”

Alpine plants, because of their smaller size, also play a much smaller role in the absorption of carbon dioxide overall.

While there are efforts underway to create protected areas of biodiversity in the Alps, Rumpf said, major action is needed to slow this trend. Overall, changes in precipitation driven by climate change are expected to reduce snow cover by up to 25 percent in the Alps, over the next 10 to 30 years.

“We can try to mitigate these effects on small scales, but if we don’t change the source of the problem it’s a rather feeble effort,” she said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.