Shocked by the Lack of Support

I just want you to know that, as a monthly contributor who thinks the work you are doing is hugely important, I am shocked by the lack of support of other readers. Rest assured that rsn is deeply appreciated and I count on it/you to keep informed.

If we want a “free” and independent press in today’s world of corporate news, you are essential and I, for one, am deeply grateful to you and want to express my thanks. I’m sorry that your fundraising efforts are not bringing faster and more abundant results.

In deep appreciation,

Marilyn, RSN Reader-Supporter

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Also: “Grievance,” “slave labor,” “This is dumb,” “living wage,” “diversity,” “vaccine,” and others.

“Our teams are always thinking about new ways to help employees engage with each other,” said Amazon spokesperson Barbara M. Agrait. “This particular program has not been approved yet and may change significantly or even never launch at all.”

In November 2021, Amazon convened a high-level meeting in which top executives discussed plans to create an internal social media program that would let employees recognize co-workers’ performance with posts called “Shout-Outs,” according to a source with direct knowledge.

The major goal of the program, Amazon’s head of worldwide consumer business, Dave Clark, said, was to reduce employee attrition by fostering happiness among workers — and also productivity. Shout-Outs would be part of a gamified rewards system in which employees are awarded virtual stars and badges for activities that “add direct business value,” documents state. At the meeting, Clark remarked that “some people are insane star collectors.”

But company officials also warned of what they called “the dark side of social media” and decided to actively monitor posts in order to ensure a “positive community.” At the meeting, Clark suggested that the program should resemble an online dating app like Bumble, which allows individuals to engage one on one, rather than a more forum-like platform like Facebook.

Following the meeting, an “auto bad word monitor” was devised, constituting a blacklist that would flag and automatically block employees from sending a message that contains any profane or inappropriate keywords. In addition to profanities, however, the terms include many relevant to organized labor, including “union,” “grievance,” “pay raise,” and “compensation.” Other banned keywords include terms like “ethics,” “unfair,” “slave,” “master,” “freedom,” “diversity,” “injustice,” and “fairness.” Even some phrases like “This is concerning” will be banned.

“With free text, we risk people writing Shout-Outs that generate negative sentiments among the viewers and the receivers,” a document summarizing the program states. “We want to lean towards being restrictive on the content that can be posted to prevent a negative associate experience.”

In addition to the automated system, managers will have the authority to flag or suppress any Shout-Outs that they find inappropriate, the documents show.

A pilot program is slated to launch later this month. In addition to slurs and swear words, the planned list includes the following words:

I hate

Union

Fire

Terminated

Compensation

Pay Raise

Bullying

Harassment

I don’t care

Rude

This is concerning

Stupid

This is dumb

Prison

Threat

Petition

Grievance

Injustice

Diversity

Ethics

Fairness

Accessibility

Vaccine

Senior Ops

Living Wage

Representation

Unfair

Favoritism

Rate

TOT

Unite/unity

Plantation

Slave

Slave labor

Master

Concerned

Freedom

Restrooms

Robots

Trash

Committee

Coalition

“If it does launch at some point down the road,” said the Amazon spokesperson, “there are no plans for many of the words you’re calling out to be screened. The only kinds of words that may be screened are ones that are offensive or harassing, which is intended to protect our team.”

Amazon has experimented with social media programs in the past. In 2018, the company launched a pilot program in which employees were handpicked to form a Twitter army advocating for the company, as The Intercept reported. The workers were selected for their “great sense of humor,” leaked documents showed.

On Friday, Amazon workers at a fulfillment center in Staten Island, New York, stunned the nation by becoming the first Amazon location to successfully unionize. This came as a shock to many because it was achieved by an independent union not affiliated with an established union and that operated on a shoestring budget. With a budget of $120,000, the Amazon Labor Union managed to defeat the $1.5 trillion behemoth, which spent $4.3 million on anti-union consultants in 2021 alone.

Adding to the David-and-Goliath overtones, the Amazon Labor Union’s president, Christian Smalls, a 33-year old former rapper, had been fired by the company after leading a small walkout calling for better workplace protections against the coronavirus in 2020. Amazon executives denigrated Smalls, who is Black, as “not smart or articulate” during a meeting with then-CEO Jeff Bezos, according to leaked memo reported by Vice News.

Safety issues have been a perennial concern for Amazon workers. In December, a tornado killed six Amazon employees in a warehouse in Edwardsville, Illinois. Many employees said that they had received virtually no emergency training, as The Intercept reported. (The House Oversight Committee recently launched an investigation into Amazon’s workplace safety policies.)

In 2020, workers at an Amazon fulfillment center in Bessemer, Alabama, tried to join the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. The attempt became unusually high-profile, attracting the attention of President Joe Biden, who released a statement saying, “Every worker should have a free and fair choice to join a union … without intimidation or threats by employers.”

The Bessemer vote failed, but the National Labor Relations Board ordered a new election, citing undue interference by Amazon. The Bessemer warehouse held a second vote that was also counted last week, and while the initial tally favored Amazon, the vote was much closer than the previous one and will ultimately depend on the results of challenged ballots.

Amazon released a statement Friday saying that it is considering filing an objection to the Staten Island union vote, alleging interference by the NLRB.

Ukraine's U.N. Ambassador Sergiy Kyslytsya urged the General Assembly to adopt a draft resolution suspending Russia from the U.N. Human Rights Council, saying thousands of Ukrainians have been killed, tortured, raped and robbed by Russia's military. (photo: Timothy A. Clary/Getty)

Ukraine's U.N. Ambassador Sergiy Kyslytsya urged the General Assembly to adopt a draft resolution suspending Russia from the U.N. Human Rights Council, saying thousands of Ukrainians have been killed, tortured, raped and robbed by Russia's military. (photo: Timothy A. Clary/Getty)

The resolution needed a two-thirds majority of the vote in order to pass. The tally was 93 in favor and 24 against, with 58 abstentions.

Several countries spoke out against the resolution, such as China, Syria and Cuba, whose representatives said human rights were being politicized. Others abstained from the vote -- including South Africa, whose representative said it did so because of a lack of due process in determining Russia’s guilt.

Belarus' representative Valentyn Rybakov said his country is “categorically against” the resolution, saying it would demonize and isolate the Russian Federation.

The world is at a critical juncture and the Human Rights Council is in danger of foundering, Ukraine's U.N. Ambassador Sergiy Kyslytsya said ahead of the vote in Thursday's emergency special session of the General Assembly.

Kyslytsya evoked the council's core goal of preventing genocide as he urged delegations to take the extraordinary step of suspending Russia from the council.

“We are in a unique situation now,” Kyslytsya said, when “a member of the Human Rights Council commits horrific human rights violations and abuses that could be equated to war crimes and crimes against humanity” in another country’s territory.

Saying that thousands of civilians in Bucha and other Ukrainian towns have been killed, tortured, raped and robbed by Russia’s military, Kyslytsya said the reasons for suspending Russia are “obvious and self-explanatory.”

Russia has repeatedly rejected claims that it has killed or harmed civilians, despite a mounting death toll and images showing Ukrainian residences destroyed by Russian attacks -- and video of Ukrainians lying dead in the streets in Bucha and elsewhere.

“We don’t target civilian facilities to save as many civilians as possible. That is why our advance is not that rapid as many expected,” Vasily Nebenzya, Russia's ambassador to the U.N., said at a Security Council session on Tuesday. "We are not acting like the Americans and their allies were acting in Iraq when they wiped out entire cities," he added.

Former president Donald Trump in 2017. (photo: Brendan Smialowski/Getty)

Former president Donald Trump in 2017. (photo: Brendan Smialowski/Getty)

The people, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the sensitive matter, said the probe remained in the very early stages. It’s not yet clear if Justice Department officials have begun reviewing the materials in the boxes or seeking to interview those who might have seen them or been involved in assembling and moving them.

The department is facing increasing political pressure to disclose its plans in the case. On Thursday, House Oversight Committee Chairwoman Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.) accused the Justice Department of obstructing her committee’s investigation into the 15 boxes of records Trump took to his estate in Palm Beach, Fla.

In a letter addressed to Attorney General Merrick Garland, Maloney alleges that the Justice Department is “interfering” with the investigation by preventing the National Archives and Records Administration from handing over a detailed inventory of the contents of the recovered boxes.

If the department is planning an investigation, that might explain why it would not want lawmakers getting an inventory of the materials.

It is unclear to what extent the Justice Department already has assessed the contents of the boxes, which the National Archives arranged to retrieve from Mar-a-Lago in January — including documents clearly marked as classified, The Washington Post previously reported. The Justice Department, though, has been in touch with the Archives about moving its own inquiry forward, people familiar with the matter said.

Addressing the matter previously, Garland said the department would “do what we always do under these circumstances — look at the facts and the law and take it from there.”

Trump’s spokesman in the past has defended his handling of the records. “It is clear that a normal and routine process is being weaponized by anonymous, politically motivated government sources to peddle Fake News,” Taylor Budowich said in a statement in February.

In her letter Thursday, Maloney said her committee needed further explanation as to why the Justice Department was blocking its request for an inventory of the records.

“The Committee does not wish to interfere in any manner with any potential or ongoing investigation by the Department of Justice,” Maloney wrote. “However, the Committee has not received any explanation as to why the Department is preventing NARA from providing information to the Committee that relates to compliance with the [Presidential Records Act], including unclassified information describing the contents of the 15 boxes from Mar-a-Lago.”

An FBI spokeswoman told The Post, “We can neither confirm nor deny the existence of an investigation.”

The National Archives sent a letter to the committee at the end of last month saying that on the basis of the Archives’ “consultation” with the Justice Department, the Archives was unable to “provide any comment” and fulfill the committee’s request. It instead referred the committee to the DOJ’s Office of Legislative Affairs for any further questions.

Maloney asked the Justice Department to tell the committee by April 14 whether it “will inform NARA that it may fully cooperate with the Committee’s inquiry, including by providing the requested inventory of documents recovered from Mar-a-Lago.”

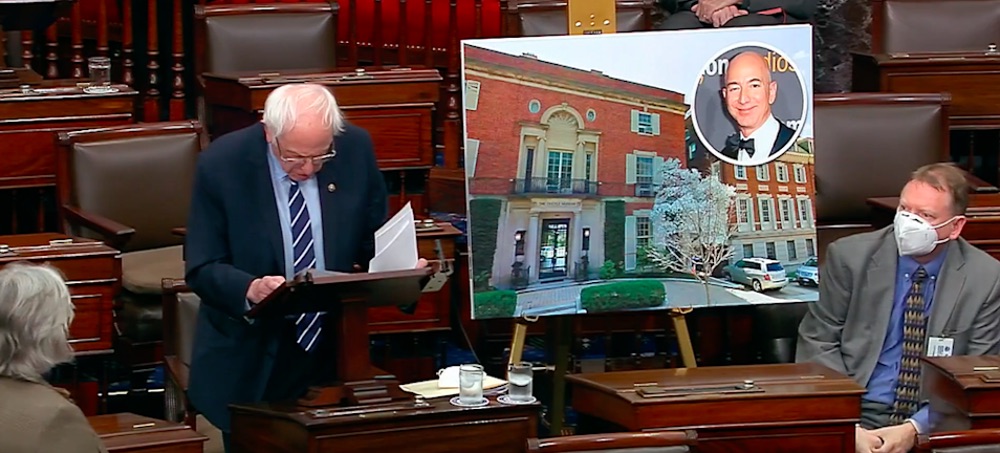

Sen. Bernie Sanders delivers a speech on the Senate floor asking for a provision to be removed from a pending bill that would send an additional $10 billion for moon landers. (photo: Twitter)

Sen. Bernie Sanders delivers a speech on the Senate floor asking for a provision to be removed from a pending bill that would send an additional $10 billion for moon landers. (photo: Twitter)

“Count me in as someone who doesn’t think that the taxpayers of this country need to provide Mr Bezos a $10 billion bailout to fuel his space hobby,” Mr Sanders said during his speech on the Senate floor

Sen Bernie Sanders, who’s public scorn of billionaires has become a staple of his policies addressing wealth distribution and reining in corporate influence, continued to champion this cause Wednesday night during a speech on the House floor where he criticised a spending bill that includes a provision to send $10 billion to NASA for private contractors, like Bezos’s Blue Origin or Musk’s SpaceX, to land on the moon.

“Count me in as someone who doesn’t think that the taxpayers of this country need to provide Mr Bezos a $10 billion bailout to fuel his space hobby,” the Vermont Independent began in his 22-minute address on the Senate floor.

Mr Sanders, who threatens to stall the legislation set up to strengthen America’s technological edge over foreign competitors, has for months characterised the bill’s moon lander provision as “subsidising” Mr Bezos “space travel”.

The pending United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021 has passed in both the House and the Senate and now awaits to be finalised with an arranged committee.

Though he’s been railing against the provision for months, the 80-year-old senator took to relying on a more theatrical approach in his latest speech on the Senate floor.

“Let me be very clear, Mr Bezos has enough money to buy a very beautiful $500m yacht,” the Vermont senator said while having an aide prop up a large blown up picture of Mr Bezos’s yacht alongside a picture of the former Amazon CEO’s smiling face. “Looks very nice to me, not that I know very much about yachts.”

He then had his aide swap out the picture of the billionaire’s yacht for another board, but this time it showcased Mr Bezos’s Washington, DC mansion.

“Mr Bezos has enough money to purchase a $23m mansion with 25 bathrooms,” he said, before quipping that he’s “not quite sure you need 25 bathrooms but that’s not my business”.

The provision that would allot $1billion to the space agency would not guarantee that those funds were funnelled to Mr Bezos’s Blue Origin, as NASA would have the discretion to divide those funds up between multiple companies, depending on who the winner of the public-private moon lander contract is.

Politico also reported that the winner of that partnership is also expected to contribute a portion of their own money to the contract.

For Mr Sanders, however, he views the provision as a failure of industrial policy in America, noting that the fact that tech billionaires who made their fortunes while largely avoiding paying federal income tax - “[Amazon] pays nothing, zero in federal income taxes after making billions in profits” - are able to benefit from “bailouts” points to a systemic problem.

Industrial policy, the Vermont Independent explained, is about cooperation, not “the government providing massive amounts of corporate welfare to extremely profitable corporations without getting anything in return”.

“That is corporate welfare … that is crony capitalism.”

A man stands with his child in front of police during demonstrations Sunday in downtown Long Beach. Police pointed rubber bullet guns to prompt crowds to back away. (photo: Richard Grant/Daily Forty-Niner)

A man stands with his child in front of police during demonstrations Sunday in downtown Long Beach. Police pointed rubber bullet guns to prompt crowds to back away. (photo: Richard Grant/Daily Forty-Niner)

Records reveal that some cities gave more stimulus money to law enforcement than to health, housing and food initiatives

As part of the American Rescue Plan Act (Arpa), the Biden administration’s signature stimulus package, the US government sent funds to cities to help them fight coronavirus and support local recovery efforts. The money, officials said, could be used to fund a range of services, including public health and housing initiatives, healthcare workers’ salaries, infrastructure investments and aid for small businesses.

But most large California cities spent millions of Arpa dollars on law enforcement. Some also gave police money from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (Cares) Act, adopted in 2020 under Donald Trump. The records show:

- San Francisco received $312m in Arpa funds for fiscal year 2020 and allocated 49% ($153m) to police, 13% ($41m) to the sheriff’s department, and the remainder to the fire department, according to the city controller. San Francisco also gave roughly 22% ($38.5m) of its Cares funds to law enforcement.

- Los Angeles spent roughly 50% of its first round of Arpa relief funds on the LAPD, according to a public records request by the controller candidate Kenneth Mejia, and first reported in local news site LA Taco.

- Fresno spent $36.6m of its Cares funds on the police, making up 67% of Cares spending on city salaries, and roughly 40% of all of Fresno’s Cares funds.

- San Jose allocated roughly $27.8m of its Cares and Arpa funds to police salaries and the police dispatch department, representing about 12% of its relief money.

- Long Beach allocated the majority of its $135.8 million Arpa funds to police, though a spokesperson said a detailed breakdown of funds was not available.

- Oakland allocated $5m (13.5%) of its Cares funds to police salaries; Sacramento allocated $2.2m (2.5%) of Cares funds to police; and San Diego spent roughly $60.1m (64%) of its Cares funds on police in fiscal year 2020, and $52.6m (33%) in fiscal year 2021.

The budgeting and reporting process varies by city and is often opaque, making it difficult to compare and analyze how governments prioritized police and executed their budgets.

In Fresno, the city allocated more than double of its Cares money to police than it did to Covid testing, contact tracing, small business grants, childcare vouchers and transitional housing combined. Oakland’s police allocation was greater than the amounts spent on a housing initiative, a small business grant program and a workforce initiative. San Jose, meanwhile, spent significantly more on housing services and food programs than on law enforcement. And although Long Beach initially reported that it was allocating 100% of its Arpa funds to police, a spokesperson said $11.8m of those funds were now going to direct relief grants and that a portion was also supporting the city’s parks and marine departments.

Officials from Oakland and Anaheim both said that their Arpa awards were used as “revenue replacement” for their general fund, and said it was not possible to specify where the federal money went (though both cities typically spend large portions of their overall budgets on police, with Oakland going $22m over budget last year). A Bakersfield representative said $13.6m in Cares funds went to public safety, but did not specify how much of that went to police.

Cities have explained their spending on police in a number of ways. In a report for the US government, Long Beach said police were “heavily involved in the City’s Covid-19 response”, including opening an emergency operations center and providing security at testing and vaccination sites.

Stephen Walsh, Oakland’s controller, said that claiming Cares funds for the police was an “accounting strategy” and that the relief money wasn’t used to expand law enforcement, but rather to avoid cuts. He said this allowed the city to “pursue a great variety of worthy projects directed at Covid relief”. A spokesperson for the LA controller also said the Arpa funds were used for LAPD revenue that had previously been budgeted, and a representative for the LA city administrative officer said allocations for “public safety services” were “consistent with the intent of the funds”.

Hillary Ronen, a member of the board of supervisors in San Francisco, noted that there were minimum staffing needs for the fire department and police, and that Covid cases in those departments forced cities to spend large amounts on public safety overtime. But she also said she appreciated the criticisms of the law enforcement allocations and that she wanted to see San Francisco invest in alternatives to police: “Over time, I do hope to shrink the budget of the police department.”

Cities using relief funds for police have typically funneled the money to salaries, although The Appeal recently reported that some jurisdictions were using stimulus dollars to buy new surveillance technology and build new prisons.

‘Cities hide their police spending’

The data in California matches national trends. After the George Floyd uprisings sparked a national debate about the role of law enforcement and calls for the US to “defund the police” and reinvest those dollars in services, local governments across the US used Covid relief to maintain and expand law enforcement, including Chicago, Philadelphia and the state of Alabama. Meanwhile, the pressure to invest more in police is growing amid a rise in homicides and other crimes, even as the crime rate remains significantly lower than previous decades.

The significant stimulus spending on police reflects the longstanding budget priorities in the US, where police spending has tripled over the last 40 years, with cities spending an increasing portion of their general funds on officers. Arpa allowed cities to replace lost revenue, so many of them funneled the relief to the agencies that previously received the most money.

But in California, a state with severe income inequality and a dramatically worsening homelessness crisis, the stimulus spending has sparked backlash from community organizers who argue that the funds should have gone directly to civilians and that police should have accepted cuts.

“It was called the ‘American Rescue Plan’, but you’re telling me that what needed to be rescued was the police department?” said Stephen “Cue” Jn-Marie, a pastor and activist at Skid Row in LA. “The city’s kneejerk reaction is always to use law enforcement to respond to everything … and the police forces keep getting larger.”

“When the money is going toward law enforcement again, it’s just increasingly criminalizing those that need the most help,” said Hope Williams, an activist in San Francisco, referencing the escalating police crackdown on unhoused people suffering from addiction in the city. Williams, who has sued the police department over its treatment of protesters, added, “It’s exhausting and infuriating, but not surprising.”

James Burch, policy director at the Anti Police-Terror Project, a coalition that organizes against police violence in Oakland, said it was frustrating how hard it was to get basic information on stimulus spending: “Cities like Oakland do everything they can to hide how much money they spend on policing, because if the public truly knew how much we spend on police and how little we spend on services, they would be infuriated.”

In LA, the Arpa spending plan was not publicized until Kenneth Mejia, an accountant and advocate running for controller, filed a public records request with the current controller. Some other cities’ public reports have not directly mentioned police at all, categorizing the expenditures under “government services” or “payroll”.

“It’s shocking and not at all transparent,” said Mejia, who has also uncovered how cannabis business taxes go to police. He further noted that LAPD was getting the funding at a time in 2021 when many of the department’s employees were declining to get vaccinated, with officers routinely caught on camera refusing to wear masks. “A city’s spending is representative of a city’s values … and you think that Covid relief money is going to help people, but it’s not. It’s going to police.”

Both Germany and Switzerland are in the process of acquiring F-35 jets from Lockheed Martin at nearly $80 million a piece. (photo: Fabrice Coffrini/Getty)

Both Germany and Switzerland are in the process of acquiring F-35 jets from Lockheed Martin at nearly $80 million a piece. (photo: Fabrice Coffrini/Getty)

Not even 1 percent of NATO military hardware will actually be used to help Ukraine. But the Russian invasion has provided a pretext for massively increased arms spending — and it’s great news for weapons manufacturers’ profits.

Military-industrial complexes everywhere are rubbing their hands with glee. NATO armies’ top brass is again resorting to the old trick of overestimating the threats, as it periodically used to do with regard to the Soviet Union during the Cold War, in order to advocate rearmament. Such a term is utterly inappropriate, given that NATO armies never disarmed to begin with; rather, they were constantly over-armed during the Cold War and have stuck to excessive arms levels ever since. Besides, whatever deliveries of defensive weapons are made to Ukrainian resistance are but a tiny portion of ongoing military expenditure — not even the 1 percent of all NATO spending that Ukraine’s president has been begging for.

Not content with the United States’ current gigantic military expenditure, which amounted to $782 billion last year — up from $778 billion spent in 2020, which itself represented, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 39 percent of global military expenditure, more than three times China’s ($252 billion) and more than twelve times Russia’s ($61.7 billion) — Joe Biden is now requesting $813 billion for the next fiscal year ($773 billion for the Pentagon and an additional $40 billion for defense-related programs at the FBI, Department of Energy, and other agencies). According to undersecretary of defense, Comptroller Michael J. McCord: “This budget was finalized before Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. So there is nothing in this budget that specifically was changed because it was too late to change it if we wanted to, to reflect the specifics of the invasion.”

Germany also seized the opportunity of the war to get rid of the last remnants of its post-1945 military self-limitation. This once again came under a Social Democratic (SPD) chancellor, Olaf Scholz, following the precedent of Germany’s participation in the bombing of Serbia under Gerhard Schröder, also from the SPD, who later reconverted his position into highly remunerated perks with the Russian gas industry. Berlin decided upon a vast and immediate one-off €100 billion ($110 billion) increase in its military spending and a massive permanent rise to above 2 percent of GDP, as against 1 percent in 2005 and 1.4 percent in 2020. Germany will thus overtake Britain, which last year became NATO’s second- and the world’s third-largest military spender.

Unsurprisingly, this renewed frenzy of military expenditure translates into happy days for the industrial interests involved in producing means of destruction. A recent report in the French daily Le Monde provided an instructive glimpse into the financial impact of all this: after quoting Armin Papperger, the head of Rheinmetall, one of Germany’s main arms manufacturers, who had complained in January about investment funds’ reluctance to work with his firm, the newspaper reported that the atmosphere has now completely changed. It adds that Commerzbank, one of the major German banks, has announced its decision to shift part of its investment toward the arms industry.

In France, after a growing trend of financial disinvestment from the arms industry under citizen pressure for ethical responsibility — especially in light of the ugly contribution of Western arms sales to the Saudi kingdom’s destruction of Yemen — Guillaume Muesser, director of defense and economic affairs for the French Aerospace Industries Association, told Le Monde that “the invasion of Ukraine is a game changer. It shows that war is still on the agenda, on our doorsteps, and that the defense industry is very useful.”

It is not hard to imagine the euphoria currently prevailing among the manufacturers of death machines in the United States, such as Lockheed Martin, the world’s largest arms-producing company. Germany decided to buy their F-35 stealth jets, whose capability to carry nuclear weapons was explicitly mentioned as a key argument in opting for them, although Germany doesn’t have nuclear weapons of its own. The unit cost of these planes is close to $80 million. Lockheed Martin’s share price peaked at $469 on March 7 in the wake of the German announcement, up from $327 last November 2 — a 43.4 percent increase in only four months.

The shift in the global mood from the end of last year is staggering. Last December, an appeal signed by more than fifty Nobel Prize winners urged the adoption of what they called “a simple proposal for humankind”:

The governments of all UN member-states should negotiate a joint reduction of their military expenditure by 2% every year for five years. The rationale for the proposal is simple: 1. Adversary nations reduce military spending, so the security of each country is increased, while deterrence and balance are preserved. 2. The agreement contributes to reducing animosity, thereby decreasing the risk of war. 3. Vast resources — a “peace dividend” of as much as 1 trillion USD by 2030 — are made available. We propose that half of the resources freed up by this agreement are allocated to a global fund, under UN supervision, to address humanity’s grave common problems: pandemics, climate change, and extreme poverty.

Perhaps such a proposal may be considered naive or utopian. Yet it is actually inscribed in the UN Charter among the functions of the General Assembly:

The General Assembly may consider the general principles of co-operation in the maintenance of international peace and security, including the principles governing disarmament and the regulation of armaments, and may make recommendations with regard to such principles to the Members or to the Security Council or to both.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine should be a wake-up call for the global antiwar movement, major sections of which neglected such pacifist goals in order to focus exclusively on political opposition to Western governments. The present opportunistic seizure of the war as a pretext for a major increase in warmongering and military expenditure fundamentally reverses the lessons that must be drawn from the ongoing tragedy.

Far from justifying such attitudes, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has shown the high risk entailed in militaristic postures. And no increase in military expenditure will change the basic balance of forces with Russia, a country that possesses more nuclear warheads than the United States, Britain, and France combined, and whose president did not hesitate to brandish the threat of resorting to his nuclear force.

The antiwar movement should support the Nobel Prize winners’ appeal and launch a coordinated global campaign demanding that the United Nations General Assembly put the appeal’s proposals on its agenda. It is now clearer than ever that there can be no serious progress in the war against climate change in particular, upon which the future of humanity depends, without a massive reduction and reconversion of military expenditure, which is itself a major source of pollution, death, and misery.

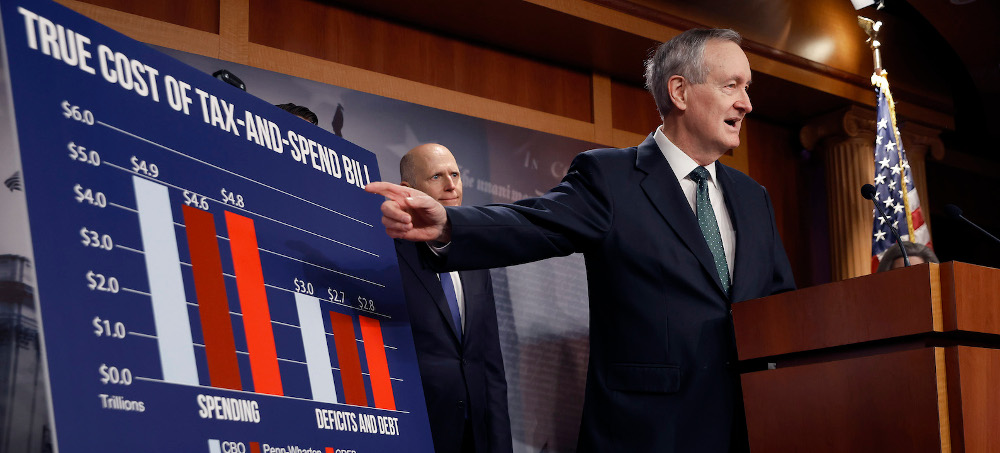

Republican Senators Mike Crapo and Rick Scott hold a news conference criticizing the costs associated with Biden's Build Back Better agenda at the U.S. Capitol, December 14, 2021. (photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty)

Republican Senators Mike Crapo and Rick Scott hold a news conference criticizing the costs associated with Biden's Build Back Better agenda at the U.S. Capitol, December 14, 2021. (photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty)

For 30 years, the debate has largely ignored the soaring costs of inaction.

It was a pivotal moment: Seven months before, during an unusually hot summer, James Hansen, then director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, had warned Congress that the signs of global warming were already upon us, making the issue front-page news across the country. By the end of the year, politicians had introduced 32 climate bills in Congress, and the United Nations had established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a group of scientists and policymakers intended to put global climate policy in motion.

In light of these developments, LeVine advised Exxon to temper the public’s growing concern for the planet with “rational responses” — not only arguing that the science wasn’t settled, but also emphasizing the “costs and political realities” of addressing rising emissions. In other words, the main problem wasn’t fossil fuel emissions, but that doing anything about them would cost too much.

This sentiment was echoed by John Sununu, then-President George H. W. Bush’s chief of staff, who worked to stop the creation of a global treaty to reduce carbon emissions soon after Hansen’s testimony. Sununu started a feud with the EPA administrator at the time, William K. Reilly, because he thought legislation to take on global warming would hinder economic growth. When Hansen was preparing to give Congress an update on the “greenhouse effect” in 1989, he was surprised by some strange edits on his draft testimony from the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, run by an ally of Sununu. They wanted Hansen to say his own science was unreliable and to encourage Congress to pass legislation only if it would immediately help the economy, “independent of concerns about an increasing greenhouse effect.”

Today, the country faces a similarly pivotal moment. When President Joe Biden took office a year ago, promising to “listen to the science” and “tackle the climate crisis,” the stars seemed aligned, with a political party in favor of climate action newly in charge of both houses of Congress. But Democrats’ narrow majority has made intra-party negotiations delicate, with Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia the fickle, final, coal-friendly vote. Once again, a focus on upfront costs is stymying a once-in-a-decade chance to pass comprehensive climate legislation.

Manchin’s complaints have centered on the sticker price. In September 2021, when Congress began considering Build Back Better, Biden’s package of social and climate policy programs, Manchin wrote an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal titled “Why I Won’t Support Spending Another $3.5 Trillion.” He asked his fellow Democrats to pick and choose which policies were really needed and to stop and consider how a big spending bill would exacerbate the problems of inflation and growing government debt. Another reason for a “strategic pause,” he went on, was to “allow for a complete reporting and analysis” of what the bill would mean “for this generation and the next.” The op-ed made no mention of climate change nor any consideration of how these future generations might fare on an unstable hothouse Earth.

Manchin is hardly alone in framing things this way. Economics has become the de facto language politicians use to debate public policy and how they evaluate solutions to alleviate planetary problems. Its persuasive power and rhetoric have been harnessed by the fossil fuel industry and its allies, who have argued for decades that climate action is a killer of economic growth, even as it has become increasingly evident that inaction is a wicked killer itself. A narrow focus on short-term costs and benefits has led to a failure of imagination, experts say: Amid an abstract debate of how to make any action on climate change economically efficient, the bigger picture of what really matters — who suffers, who benefits, whether the planet burns to a crisp — often gets lost.

“Sometimes there are other things that we might want to value besides efficiency,” said Elizabeth Popp Berman, a sociologist who wrote the new book Thinking like an Economist: How Efficiency Replaced Equality in U.S. Public Policy.

For months, headlines about Build Back Better highlighted the price tag, which was eventually trimmed from $3.5 trillion to $1.7 trillion. The coverage often missed the necessary context: Those trillions were budgeted over 10 years, or $170 billion a year. And yet Congress passed a $768 billion defense budget in December with little criticism from the mainstream media. Even Manchin voted for it. “Why Doesn’t the Pentagon Ever Get Asked, But How Will You Pay for It?” read one headline from the left-leaning The New Republic.

The general public has a “highly skewed” economic understanding of climate change, said Benjamin Franta, a historian who studies climate disinformation at Stanford. He said there’s “a tendency to focus on the cost of action and not the cost of inaction.” He blamed this, in part, on a coordinated industry effort to emphasize the price tag of climate policies, with no mention of who they help (thousands of lives saved) or even how they could save the government money in the long run.

Not long after LeVine advised Exxon to highlight the economic costs of climate policies, the fossil fuel industry began paying economists to produce research that made legislation look prohibitively expensive. When people talk today about climate change costing too much, “the industry’s fingerprints are on that message,” Franta said.

The field of economics started dominating discussions around government spending decades before that infamous Exxon meeting in 1989, and it’s often taken for granted that money is a light to guide legislation. For many politicians, the first step is recognizing that there’s a problem; and the second step, unless it’s seen as an existential threat like a world war, is figuring out if it’s cost-effective to fix it. This way of thinking even shapes the words they use to talk about nature: Forests are “natural resources,” fish are “stocks.”

“Economics is the mother tongue of public policy, the language of public life, and the mindset that shapes society,” wrote Kate Raworth, a self-described “renegade” economist at Oxford, in Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist.

Economists themselves, however, haven’t always been comfortable with the authority granted to them. “The ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed, the world is ruled by little else,” wrote John Maynard Keynes, the English economist whose ideas overhauled how governments spent money, in the 1930s. “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

Thanks largely to the success of Keynes’ ideas, the field’s privileged role in government only expanded from there. During World War II, economists helped the U.S. government find ways to finance the war and use military resources more efficiently; in the aftermath, they helped with rebuilding Europe and became embedded in the U.S. government more officially.

The Truman administration formed the Council of Economic Advisers in 1946, making economists the first social scientists with a presence in the president’s inner circle. Economic theory became more of a mathematical “science” as it incorporated computational modeling — giving it the appearance of being more scientific, and thus more authoritative than ever.

In 1965, inspired by how economists were managing the Pentagon’s budget with cost-focused analysis, President Lyndon B. Johnson decided to expand the approach to other agencies. By the late 1970s, economic thinking had pervaded government policy, guiding legislation around poverty, health care, and the environment. In 1975, the Congressional Budget Office was formed to provide nonpartisan budget analysis for lawmakers, “formalizing that this is the way we should think about legislation,” Berman said.

The rising influence of money-driven decision-making had the effect of narrowing debates over public policies, dialing down ambitions to address environmental crises, compounded by a shift in focus among many mainstream economists to the risks of rising government debt and inflation. Consider the foundational pieces of environmental legislation in the United States, the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act of the early 1970s. They put in place strict standards for controlling pollution, regardless of economic consequences. But by 1990, environmental policy had moved away from this moral framework that stigmatized polluters, according to Berman.

“There was a big push to try to reframe environmental policy around thinking about really considering cost explicitly,” she said. Pollution was simply seen as an “externality” to put a price on, rather than something to try and stop altogether. A top-down regulatory approach had been replaced by a cost-sensitive strategy, which is inherently at odds with ambitious government action. “I think many of the landmark pieces of social policy legislation wouldn’t have existed if we had thought like that about them at the time,” Berman said.

By the time that Hansen testified before Congress in 1988, some people already viewed legislation to address the problem of the “greenhouse effect” as a threat to economic growth. Bush’s chief of staff, Sununu, worked to block climate initiatives at every turn. He saw efforts to restrict emissions as part of a larger, conspiratorial plot by environmentalists — some of whom worried that the combination of economic and population growth would lead to societal collapse. “Some people are less concerned about climate change and more concerned about establishing an anti-growth policy,” Sununu told the New York Times in 1991. The following year, he convened a “Workshop on Global Climate Change” for economists to discuss how reducing emissions would harm growth.

The American Petroleum Institute, the oil industry’s largest lobbying group, took a similar tack and began commissioning studies to put numbers behind the idea that climate policies would hurt the economy. In 1991, David Montgomery, an economist at the consulting firm Charles River Associates, calculated that a carbon tax — a fee imposed on fossil fuels — of $200 a ton would shrink the country’s economy by 1.7 percent by 2020, a finding that appeared in the Associated Press, CNN’s Moneyline, and the New York Times.

“The costs [of climate policy] would be high,” Montgomery told USA Today in 1992. “Economic benefits are uncertain, distant, and potentially small.”

The 30-year-old strategy is still going strong. When former President Donald Trump announced that he would pull the U.S. out of the Paris climate agreement in 2017, he repeatedly cited industry-funded estimates of its cost, dropping peculiarly specific numbers: “2.7 million lost jobs by 2025,” “$3 trillion in lost GDP,” “households would have $7,000 less income.” These statistics, Stanford’s Franta said, were from some of the same industry-funded economists that had been quoted in newspapers in the 1990s.

In February, the leaders of several organizations working to undermine climate action — the Heartland Institute, Competitive Enterprise Institute, and JunkScience.com — held a press conference to discuss Biden’s “harmful climate agenda” ahead of his State of the Union address. “Overwhelmingly, Americans do not want to pay for the cost of climate action, especially when such actions will hold negative consequences for the economy and America as a whole,” a media advisory describing the event said. (Grist’s requests to attend the event never received a response.)

“We see a rinse-and-repeat pattern with climate legislation,” Franta said. “It’s often the same players, it’s often the same talking points. You know, ‘This is too expensive. It’s not going to work.’” Whenever the federal government was considering taking action — from when the Clinton administration proposed a carbon price in 1993 to when Senators John McCain and Joseph Lieberman introduced a bipartisan national cap-and-trade program in Congress in 2003 — the industry trotted out economists’ models that conveniently ignored the economic upsides of the policy.

One of the economists who used to analyze climate policies at Charles River Associates, Paul Bernstein, now advocates for passing a price on carbon emissions and volunteers with the Hawaii Chapter of the Citizens’ Climate Lobby. He regrets that his models only looked at the costs, not the benefits.

“I think the models are good, I think the economics is good,” Bernstein told Grist. “But one problem with it is the messaging around not telling the whole story. That’s, I guess I would say, my biggest regret … Almost always, all we were asked to do is report on the costs. And in terms of benefits, the benefits we reported were the amount of emissions that were reduced, but there were no dollar figures attached to that.”

For a long time, Berman said, economists didn’t have the tools they needed to calculate the benefits of regulatory policy; it was more straightforward to calculate the costs. As corporations that wanted to avoid regulation started pushing for more attention to costs, they formed alliances with economists, who weren’t necessarily hostile to environmental policy, but simply wanted to make it more cost-effective. “That just lined up really well with also what industry was trying to achieve in weakening environmental protections,” Berman said. They became “unintentional allies” in making cost and cost-effectiveness “the central way of thinking about environmental outcomes.”

This kind of thinking lingers, even in international reports that warn about the dangers of inaction. A report out this week from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for example, calculated the costs of addressing rising temperatures separately from its benefits. In the report’s summary for policymakers, the panel noted that policies to cut global emissions in half by 2030 could hinder global economic growth “a few percent” by 2050 — if you ignore all the real-world costs that come with a hotter planet as well as the benefits of cutting emissions (less air pollution, healthier and more productive people). Why consider this hypothetical, unrealistic scenario at all? In a study from the journal Nature in November, researchers from Europe and Canada argued that these “overly pessimistic” calculations provide “a skewed image to policy-makers,” drawing their attention to the cost of taking action.

Such economic models render key aspects of this planetary problem invisible, from soaring temperatures and oppressive heat waves to the slow unraveling of Earth’s life-supporting ice, ocean, and land systems. As John Sterman, an expert on complex systems at MIT, once observed, “The most important assumptions of a model are not in the equations, but what’s not in them; not in the documentation, but unstated; not in the variables on the computer screen, but in the blank spaces around them.”

Of course, opponents of a particular policy, whether it’s health care reform, public transit projects, funding education, or providing emergency relief, frequently point to its upfront cost. “GOP senators balk at $1.9 trillion price tag for Biden’s COVID-19 bill,” read a headline from CBS News last year.

Climate change is simply an egregious example because the cost of doing nothing is astronomical. Economists estimate that by around 2030, the consequences of heating up the planet could include a $240 billion COVID-like economic shock every five years. Democrats have leaned into this message — in November, Biden tweeted that “every day we delay, the cost of inaction increases.” The upper-end estimate for the price tag of unchecked global warming? $551 trillion, more money than currently exists on Earth.

Many politicians still haven’t come to terms with those estimates. Last month, Sarah Bloom Raskin, Biden’s nominee for a top post at the Federal Reserve Board, was forced to withdraw after facing opposition from Republicans and Manchin for making the case that the central bank has a role to play in shifting away from carbon-heavy assets and helping to prevent a climate change-fueled financial crisis. In her withdrawal letter, Raskin wrote that she feared that “many in and outside the Senate are unwilling to acknowledge the economic complications of climate change and the toll it has placed and will continue to place on Americans.”

In the past, the price of failing to address climate change seemed theoretical, decades down the line. Today, we’ve already begun paying for it. Last year alone, the United States spent $145 billion on the 20 worst climate and weather disasters, from the wildfires in the West to Hurricane Ida in the Gulf of Mexico. In fact, 2021 was the third costliest year for disasters in U.S. history, according to a recent report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

More severe weather patterns are already impeding economic growth. Climate change has slashed agricultural productivity in North America by roughly 13 percent over the last 60 years (though other factors have increased overall productivity), according to a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in February. Americans are beginning to grasp the situation. In a recent survey by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, a third of respondents said they were not just concerned, but alarmed about global warming. Political action in the U.S., however, has been slow to catch up.

After the House of Representatives passed Build Back Better last November, the bill stalled in the Senate. It all fell apart in December, when Democrats failed to meet Manchin’s demands to trim the bill by cutting other policy items, such as expanding child tax credits. Now, seven months before the midterm elections, when Democrats risk losing their narrow majorities in the House and Senate, discussions around Build Back Better are restarting — amid political turmoil caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and surging gasoline prices.

Democrats, including Manchin, have agreed on many of the climate aspects of the bill, which would put $555 billion toward incentives for renewable energy and green transportation. But the funding is tied up with all the other elements of the package — like prescription drug reform and more affordable health insurance.

And all of them come with a price tag.

Economics provides a useful way of looking at the world, but it isn’t the only way. So how do we fill in what economic models have so often left out, all those blank spaces, and make what’s been hidden visible? There are a lot of different ideas, from highlighting the benefits of climate action when it comes to drawing up legislation to focusing on more concrete, local needs that get lost in big-picture debates.

Adie Tomer, an infrastructure policy and urban economics expert at the Brookings Institution, has proposed scoring legislation for “climate impacts, not just budgetary impacts.” That could mean that every bill would get a standardized metric (like “greenhouse gas emissions per dollar”) that would help track progress toward emissions-cutting goals, as well as help politicians and voters understand “the sometimes-invisible climate impacts of legislation,” Tomer wrote in a blog post with Caroline George, a research assistant at Brookings Metro.

“We do not yet have a standard form of legislative environmental scoring in the United States,” Tomer told Grist. That makes it hard for people to compare the outcomes of, say, the Clean Electricity Performance Program introduced in the House of Representatives last year — which would have rewarded utilities for producing clean power — to the clean energy tax credits currently being considered as part of Build Back Better.

Several countries already use a form of green budgeting. France, for instance, does an environmental analysis of its budget before it even goes up for discussion, providing information to the members of the National Assembly on what the bill would mean for climate change, land use, water resources, waste systems, and plant and animal species. “The long-run costs are what also needs to be communicated,” Tomer said. “It’s not just, ‘Hey, these are the budget impacts upfront,’ but in fact, ‘What could be the long-term impacts on society?’”

Others want to get away from the big-numbers approach altogether and focus on specific, local needs. Shalini Vajjhala, a former Obama administration official who now helps cities prepare for the threats brought on by climate change, says that generalities aren’t helping. “Nobody needs to hear that we need trillions of dollars for adaptation,” she said. To drive more money toward climate projects, people need to hear what it needs to be spent on, where it could go, and who, specifically, would benefit. What will prevent a wildfire from burning down the neighborhood? How can we stop homes from flooding in the next hurricane?

Steering conversations toward something concrete and vivid — and away from polarizing topics like climate change and far-off future scenarios — can speed up action, Vajjhala said. “When people are debating about doing something, I will ask, you know, ‘Are you aware of how much money you’re losing if you don’t do this?’”

Take transit agencies as an example. Extreme heat melted streetcar cables in Portland last summer. Hot temperatures can warp steel tracks and overheat engines and have caused long delays for trains in the Bay Area and speed restrictions on Amtrak trains on the East Coast in recent years. So during heat waves, transit agencies have been sending out fewer trains and running them more slowly, Vajjhala said. That means older adults and transit-dependent workers are stuck outside waiting for the train on the hottest days of the year, and in the meantime, transit agencies are also “hemorrhaging money,” she said. Pointing this out changes the direction of a conversation: It’s no longer about “if” or “when,” but simply “how” to fix it.

As for economists, they’re getting better at quantifying why avoiding catastrophic climate change is worth so much. Franta says there’s a new generation of economists looking at the costs of flooding, storms, droughts, heat waves, wildfires, and other disasters, quantifying the damages and how much can be attributed to climate change. “I think society needs them to step up and do that full analysis, you know?” Franta said. “Not just do part of the picture, not just look at the cost of a policy because that’s what they are hired to do, but use it to serve society and look at the entire problem with the entire picture.”

Economics is a necessary part of policy discussions, but it has come to dominate them to the point that people have started to see other perspectives as irrational and unreasonable, Berman said. The moral arguments that once brought the Clean Air Act into being have ceded ground to approaches that tinker with the market. Relying on clean energy tax credits, as Build Back Better does, is a lot less ambitious, and harder for normal people to understand, than declaring that you’re going to try to completely phase out fossil fuel production.

“Applying economics in a political context isn’t necessarily going to get us to where we want to go in political terms, right?” Berman said. “There’s a gap between abstract models of how things should work and what it actually takes to create change in the world.”

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.