Final Day, Trying Anything to Stay Close

We have taken a huge hit this month. Right now it the worst fundraising drive in our 21 year history. 100 donations today would change that.

Chip-in, we need it now.

Marc Ash

Founder, Reader Supported News

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

It can be dangerous to tell the truth. Why couldn’t she have said, “I love it, it’s one of your best”? His poems weren’t hurting anybody. Polar bears weren’t dying from them, they weren’t poisoning the rivers. Let the man be a bad poet and eventually he’ll find his way into marketing or lawn mowing or some other gainful employment.

That’s how I feel about COVID. Yes, people suffered, some terribly, but it also had its bright side. Millions escaped their cubicle jungles and got to work at home in their pajamas. We skipped big fundraising dinners and games where unmasked people sing the school fight song, emitting clouds of infected droplets with every “Fight, fight, fight,” and we regained the pleasure of staying home and playing Scrabble with a loved one. Colleges shut down and some kids who would’ve majored in women’s studies and wound up grinding out lattes at Starbucks went online and found out about Bitbond and earned a few million and retired to the Maldives. Some kids who planned to become novelists went into house painting instead and are happier.

We learned how to use the telephone again. Social media is what it is, but on the phone you can enjoy chitchat, banter, palaver, gossip. On Instagram, you just run up a flag, and on the phone you kid each other, tell jokes, banish loneliness, whereas with Twitter you’re just throwing manure at the barn wall. I don’t do FaceTime because I look like Cotton Mather with a migraine, but with audio I can be sort of charming.

While the virus hangs around, we’re all living in the present. Our kids and grandkids own the future and I worry about them. I worry how they will deal with medical insurance without reading the ream of microscopic print that grants the Company (hereinafter known as Beelzebub) the right to the client’s firstborn. I worry about the Supreme Court now that it has six federalists who commute to work on horseback.

I have no right to rag on the Court; I’ve done dumb things that make your mistakes look like inspired genius. When I retired in 2016, I gave away my company to my former employer for free, and a year later the CEO called me on the phone and fired me, no “Thank you” or anything. I said, “Okay.”

I once had a best-selling book and used the profits to open my own bookstore in a basement in St. Paul, expecting long lines of shoppers, but no, Amazon was taking over the world. It’s so easy to buy stuff from Amazon, you can do it in your sleep, and people do. Amazon owns the rights to the Bible. You can’t even use the word “ishkabibble” without paying them. The first hundred bucks in the collection basket at church goes to them because they own the Lord’s Prayer. So my bookstore floated away on red ink and I thought of having my head examined but shrinks don’t deal with dumb, it’s beyond their scope. Bookstore ownership was my dream and when we’re asleep the mind takes its own path. The most righteous are capable of dreams they could not confess to others for fear of excommunication. St. Paul had dreams he didn’t include in his epistles. Solomon did dumb things. Wisdom comes from experience, and experience includes stupidity. Theology is about truth but life is about banana peels.

So it’s good to see the world’s richest man pay $44 billion for Twitter. It’s a good investment, like cornering the market on mosquitoes. Think of the blood you’ll collect every year. The mind boggles as it never boggled before.

A man rides his bike past flames and smoke rising from a fire following a Russian attack in Kharkiv, Ukraine, Friday, March 25, 2022. (photo: Felipe Dana/AP)

A man rides his bike past flames and smoke rising from a fire following a Russian attack in Kharkiv, Ukraine, Friday, March 25, 2022. (photo: Felipe Dana/AP)

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: The head of the International Atomic Energy Agency is expressing alarm over safety issues at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant in Ukraine. Russian forces seized the plant in early March after a fight that led to a fire near one of the plant’s reactors. This week the Ukrainian government accused Russia of launching two cruise missiles that flew at low altitudes over the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. Ukraine says Russian missiles have also flown over two other nuclear power plants in Ukraine.

The IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi described the situation at the plant as a “red light blinking” issue. Zaporizhzhia is the largest nuclear power plant in Europe, and it’s located in the largest city in southeastern Ukraine still under Ukrainian control. During a news briefing Thursday in Vienna, Grossi addressed the reports of Russian missiles flying over nuclear power plants.

RAFAEL GROSSI: Any such development, if confirmed, would be extremely serious. I have been saying from the first day of this crisis that the physical integrity of nuclear facilities is an absolute must. And, of course, a missile going astray, or something like this, could have significant — a very significant impact. But we need to go back to Zaporizhzhia. It’s extremely important. In Zaporizhzhia, you have tens of thousands of nuclear material, plutonium, enriched uranium. And we have to be verifying that. So, it’s still the open question that we have at the moment.

AMY GOODMAN: IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi, speaking Thursday after returning from a trip to Ukraine, where he visited the Chernobyl nuclear power station on Monday, on the 36th anniversary of the plant’s meltdown. Russia seized Chernobyl in late February and occupied the highly contaminated area until late March. Grossi vowed to help Ukraine repair damage caused during Russia’s occupation. He praised workers at the plant for helping to prevent what could have been another nuclear disaster.

RAFAEL GROSSI: In this case, what we had was a nuclear safety situation that was not normal, that could have developed into an accident. I think the first credit must go to the operators, to these people here, because they carried on their work in spite of all the difficulties, in spite of the stress, in spite of the fact that they could not be working normally. They continued working as if nothing had happened, so they kept the situation stable, so to speak.

AMY GOODMAN: The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster was the worst nuclear meltdown in world history.

We’re joined now by Olexi Pasyuk. He is deputy director of the Ukrainian NGO Ecoaction, where his focus is on energy and nuclear energy, joining us from Ukraine.

Olexi, thanks for being with us once again. Can you talk about this week, I mean, the significance of the 36th anniversary of Chernobyl, with the IAEA director coming to mark that, and at the same time, a few days later, these reports that Russian missiles flew very low down over the largest nuclear power complex in Europe at Zaporizhzhia?

OLEXI PASYUK: Indeed. I mean, Chernobyl is exactly a place which demonstrates what the nuclear industry accident could be, right? It’s huge areas of land which continue to be polluted with radioactive materials. Back in '86, it was a huge impact for people who lived there. You had hundreds of thousands who had to flee. And it was an amazing cost, because, basically, it's still Soviet Union, which started to deal with the accident — it’s only recently we finally got safe containment of a destroyed reactor, which international community paid over $2 billion.

So, yes, and, of course, this is particularly kind of a great demonstration of the risk when Russians are coming. Russian army came and occupied Chernobyl power plant. I mean, that’s the site where we don’t have operating nuclear reactors, so it’s less of the risk of the accident of that scale, but we have spent nuclear fuel there, which could also be destroyed and have a release of radioactive materials in the air.

But, of course, Zaporizhzhia, where you have reactors in operation and they continue to work now, is far more dangerous situation also because it was directly attacked. You know, I have to remind that this concern was in place back from 2014, when the war started in Ukraine, in eastern Ukraine, and it was just a couple of hundred kilometers away. And there was already then a discussion: What if missile basically goes the wrong way and attack reactors themselves or the nuclear spent storage facility, and we will have a release? But what happened is that, actually, we just had an attack when the site was shelled by Russian tanks. And it was a very serious accident, because there are different scenarios of what can go wrong at the nuclear power plant, and you don’t necessarily need to be directly hitting a reactor or storage to cause problem, because these are the systems where you constantly have to cool down the fuel, and if you have an interruption in the electricity supply and cooling systems stop operating, you start getting into this accident of fuel melting.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you comment on — despite the fact of the risks, there are reports that European nations are embracing the possibility investing in more nuclear energy to be less reliant on gas and oil. What would this mean? And also, what does it mean for Ukraine? What message do you have for them?

OLEXI PASYUK: Well, indeed, there are a few of these discussions, but I think there are different voices on that. For example, in Europe, with all the gas crisis, nuclear is being considered as one of the answers, not so much about building new reactors, because it’s long and very expensive, but also there is also an option to extend lifetime of existing reactors, like — and particularly Germany was looking into these options not to close reactors which they’re supposed to close. And they come up with the kind of assessment that it will not make sense, that the risks associated with nuclear is far bigger than benefits, particularly, for example, in this story with natural gas. The issue is that gas, to a large degree, is used for industry and for heating, while that would not be simply compensated by electricity. It’s a far more complicated issue.

But I think it’s interesting that now we have this demonstration of, you know, a rather theoretical story. It was always theoretical. What happens if there is a military attack on nuclear? And it was never properly considered. It was always seen as something not very realistic. But now everywhere it should be considered as the kind of setting up a nuclear bowling pole of a kind, let’s say, which can become attacked and have destruction. You know, it brings me back to my school time, when we have the big independence movement in late '80s in Ukraine, still as a part of the Soviet Union. And I was handed, you know, these leaflets on the streets of Kyiv, where there were a map of Ukraine with the reactors being shown. And the article basically was saying, “Look, Soviet Union, Russia have planted these nuclear bombs on our territory.” And, of course, it was this post-Chernobyl moment where the whole anti-nuclear movement was very much connected to independence. But now we're basically getting the proofs that it’s very real, it’s very practical, and that nuclear brings so many security issues that — yeah, that it isn’t worth it.

I also would point out on the political leverage that Russia is getting with nuclear technology. We currently have in European Union a number of countries which operate Soviet-designed reactors and which are dependent on Russian fuel. So, it’s similar to gas, you know? We constantly were talking about these gas wars between Ukraine-Russia, Europe-Russia. It was happening for the last couple of decades, when they would just cut on supply, but —

AMY GOODMAN: Well, let me ask you something, on that issue —

OLEXI PASYUK: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: — of Soviet reactors, Russian reactors. The U.S. and Europe are imposing a number of sanctions on Russian oil and gas. Interestingly, the U.S. is not imposing sanctions on Russian uranium, which it imports. Can you comment on this? Do you think it should be included in the sanctions list?

OLEXI PASYUK: Yes, it certainly should be. I think it’s — you know, this war is very important. As West don’t want to directly intervene militarily, it should use these economic tools. And Rosatom, this nuclear Russian company, this is exactly one of the tools which, as I just was saying, Russia is using as political tool internationally. And it should be basically under sanctions, as well.

There are some of the steps which are happening. For example, in Germany, there are some common joint companies which are reviewing their agreements with Russia. But most of the companies don’t. And I think this is also a moment which expose how much different countries, including U.S., are dependent on Russian nuclear industry.

So, yes, I definitely would say that all kind of sanctions on Russian energy supply, and nuclear, in particular, should be implemented. Unfortunately, it’s complicated. I think it’s problem that we don’t realize the scale. For example — for example, what happened in last week, that despite there is a ban on the plane flying to Russia from Europe, there was a special agreement to have one plane coming from Russia to Slovakia to bring nuclear fuel. So, I mean, that shows the scale of this kind of dependence and importance of that.

AMY GOODMAN: And you have this incredible irony that, of course, President Zelensky is really pushing hard for sanctions to be imposed by European countries and the U.S. on Russia oil and gas, but you’ve got the pipelines of Russia going through Ukraine to Europe, and Ukraine is not cutting those off. I think 30% of the fuel that goes through there — 30% of Europe’s fuel that goes through there is through Ukraine.

OLEXI PASYUK: Yeah, but because, I mean, it would be probably wrong politically for Ukraine now dictate Europe whether it buys it or not. It asks, right? So, of course, it’s important to maintain there, especially in the situation when the way out is really defeating Russia on the ground, which Ukraine is struggling to do. And it brings us back to the situation in Zaporizhzhia, you know? The reality is that we cannot guarantee nuclear safety in Ukraine unless the war is over. And we have to remember that Russian army is still staying at Zaporizhzhia power plant, which is still operating. And the issue is, we don’t know how it will be over, because now it’s a kind of a situation of some kind of unclear stability, when we don’t know what is happening on the station, but there is not active combat is happening. But at certain moment, Russian troops will need to retreat, and we don’t know how it will be happening and what will be happening then.

AMY GOODMAN: Olexi, we want to thank you so much for being with us. Olexi Pasyuk, deputy director of the Ukrainian NGO Ecoaction, focusing on energy, and particularly nuclear energy. Please be safe. Speaking to us from western Ukraine.

Next up, we go to the Pulitzer Prize-winning Atlantic journalist Ed Yong about the — what does he call it? — the “Pandemicene,” how the climate emergency could spark the next pandemic. Stay with us.

Demonstrators during the "Fight Starbucks Union Busting" rally in Seattle, Washington, Saturday, April 23, 2022. (photo: David Ryder/Getty)

Demonstrators during the "Fight Starbucks Union Busting" rally in Seattle, Washington, Saturday, April 23, 2022. (photo: David Ryder/Getty)

We have a rare opportunity to rebuild a fighting labor movement in the United States. To take advantage of it, workers must be armed with battle-tested strategies and tactics — and that means being willing to go on strike.

It began last fall with “Striketober,” a season of major strikes at John Deere, Nabisco, Kellogg’s, and elsewhere. Striketober was followed by a nationwide unionization drive by Starbucks Workers United (SBWU), which is still ongoing. Workers at eighteen Starbucks stores have won their union elections, and organizing committees have been declared in over 240 stores.

And in a historic vote at New York’s JFK8 warehouse, workers have won the first-ever Amazon union on US soil. With eight thousand workers, JFK8 is one of the biggest new unionized sites in decades. Workers at one hundred other Amazon facilities, along with workers at Walmart and Target, have since reached out to the independent Amazon Labor Union (ALU) to find out how to replicate this success in their workplaces.

The Billionaires Retaliate

In response to this wave of organizing, the bosses are going on the attack.

At Starbucks, executives are carrying out a union-busting and firing spree. Since February, at least eighteen workers have been fired for trying to unionize their stores.

The onslaught of union busting, with “captive audience” meetings and worker intimidation, has been increasingly accompanied by the cutting of employee hours, aimed particularly at worker leaders, in hopes of driving them out of their jobs. There is even a leaked recording of an all-managers meeting where executives urge store managers to accelerate the onboarding process of workers they are confident will vote against forming a union.

Former Starbucks CEO and multibillionaire Howard Schultz, who was brought back to lead this union-busting effort, said publicly that corporations were being “assaulted” by workers trying to unionize.

Meanwhile at Amazon, in the wake of the JFK8 vote, executives have initiated a legal filing against ALU in hopes of overturning the union election. They also ramped up their anti-union campaign at the second Staten Island Amazon facility (LDJ5), which began voting on April 25. Amazon’s charge is that ALU is an “outside organization” that wants to take a cut of workers’ hard-earned money in the form of dues. At LDJ5, ALU workers responded by circulating a flyer highlighting their key demands and stating, “Despite what Amazon tells you, a union isn’t some outside organization. It’s a legal recognition of our right to have a say at work as a group instead.”

Workers Take Up the Strike Tactic

In the face of attacks from the bosses, the best defense is a good offense.

In response to this offensive by Starbucks management, workers have begun striking at individual Starbucks stores. These actions have been mostly or entirely led by rank-and-file workers themselves.

In Buffalo in January, workers went on strike at the height of the Omicron wave over COVID safety issues. After five days on strike, they won a massive victory: paid time off for workers exposed to COVID, applied to all Starbucks stores nationally. This victory shows how effective strikes can be when they’re well organized with clear demands.

Another powerful example took place recently at Darwin’s Ltd., a coffee and sandwich chain in the Boston area. Workers organized for a union last fall and were granted voluntary recognition — but that hasn’t meant that the owner has simply accepted the union. Instead, management has been blatantly dragging out the bargaining process in the hopes of demoralizing workers and blocking the union after the fact.

Darwin’s United, the workers’ union, fought back. They carefully planned and organized for a short, synchronized seven-minute strike at all four store locations. Workers initiated the strike by addressing customers at each store from the inside, as you can see in this video, in which Darwin’s worker Sam White, a socialist and member of my organization, Socialist Alternative, effectively explains the reasons for their action. The video went viral, with more than 1.2 million viewers in just a few days.

The tactic proved highly effective. Darwin’s United won four more bargaining sessions in the following six weeks (after just one in the previous six weeks) along with a new disciplinary agreement including due-process requirements — a huge step forward for job security that management had ferociously resisted.

In two cities near Seattle, where I serve as a socialist on the city council, there have also been worker-led strikes in the last three weeks.

In March, in the state capital of Olympia, workers carried out a one-day strike at Cooper Point Starbucks, which I attended in solidarity. The workers were angry at hours cutting and other attacks by management, which have made it even more difficult to scrape by on the poverty wages they’re receiving. At the picket, workers explained how they understood that they had to stay and fight because quitting and going to another job is not the answer — jobs for Generation Z are abysmal all over.

Three weeks ago, in Marysville, an hour north of Seattle, Starbucks workers held a three-day strike to fight back against hours cutting and bad workplace conditions that led to two rat infestations this year. Again, my office and I participated in this strike. Workers campaigned around strong demands, talked to customers as they came up to the drive-through window, explained the reasons for their strike, and encouraged them to buy their coffee at other nearby locations.

By the third day, the store was fully shuttered, including the drive-through. Also on the third day, the workers formally announced the filing of their union cards for an election. Because they acted together, in a united fashion around clear demands, they were able to take strong, militant action even before they filed for an election.

Two weeks ago in Seattle, workers at two Starbucks stores also went on strike, including at a prominent downtown store. The downtown store workers were on strike for three days. There were some missteps: the second day’s picket started too late in the morning, leaving a window for management to keep the stores open, which they did. Nonetheless, the strikes were a major show of force in Starbucks’s hometown and Schultz’s own backyard.

Sharpening the Tool

The strike is the sharpest tool workers have to fight for their collective interests, as it exercises the power to withdraw their labor and interrupt the bosses’ profits.

Most of the major gains of the labor movement were won through effective use of the strike tactic. The successes of industrial unionism in the 1930s and 1940s, including the launch of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), was won on the shoulders of three major strikes in Minneapolis, Toledo, and San Francisco in 1934 (all led by socialists) and the historic General Motors sit-down strikes in 1936–37.

The 1970s saw a massive wave of strike action, driven in part by the rampant inflation of the period — which is again creating explosive conditions today — leading to the historic victory of a major expansion of unions into the public sector. But since then, strikes have largely fallen out of use. They’ve been low for decades, in parallel with the long decline of the labor movement.

This is not an accident but is directly connected to the rise of “business unionism” — in short, the idea that workers should quietly let labor leaders negotiate mutually agreeable contracts with the bosses (in reality they are often filled with defeats for workers) rather than actively organizing themselves. One of the hallmarks of business unionism is preventing strikes at all cost in exchange for a “seat at the table” to negotiate. Business unionists put their stress on the bargaining process. They fear antagonizing management by any real mobilization of workers, much less going on strike.

This bankrupt approach has helped lead to the lowest levels of unionization in over a century, with the private sector at only 6 percent union. We need to break with all these failed methods if we are to succeed in rebuilding a fighting labor movement. That means learning how to strike again.

But not all strikes and workplace actions are created equal — some are more effective than others. In working out best practices, we can learn lessons from strikes, organizing drives, and other workplace actions past and present.

The strike should be viewed as one key part of an overall class-struggle approach to winning gains for workers, recognizing that power in the bargaining room comes from building power outside, in the workplaces and on the streets.

To succeed in building for any workplace action, it’s vital to organize around strong demands. This is particularly crucial in a strike or unionizing effort, when workers are under fire from the bosses. Workers need to know what they are fighting for, what the union is about, and what the strike is about. As in any other workplace struggle, Starbucks Workers United’s organizing efforts could be vastly improved by the introduction of clear demands.

The leaders of the Amazon Labor Union’s historic victory at JFK8 put their demands front and center in their flyers, in their organizing meetings, and in their one-on-one conversations. They called for: $30-minimum starting pay; job security including union representation at all disciplinary meetings to protect from wrongful termination or mistreatment; abolishing Amazon’s mandatory overtime policy outside of “Peak” and “Prime” week; two thirty-minute paid breaks and an hour lunch; and real time off, including sick time, at least two weeks paid time off per year, and an end to the point system the company uses to determine unpaid time off.

These demands are concrete, clear, and have numbers attached. In contrast, when forced to agree to demands at all, business unionists strongly prefer vague demands, without numbers, or ones that are purely aspirational. This is because they don’t want a mobilized rank-and-file any more than they want a strike. When it’s unavoidable, they don’t want to be held answerable to anything concrete.

In addition to clear demands, it’s also essential to win a strong majority of workers to the strike. A strong majority does not have to mean consensus — unanimous support is unusual even in the strongest of strikes, and workers can’t be held up waiting for complete agreement. Some workers can also be won over through a dynamic strike, as happened in Marysville where a worker who did not initially join the strike did so on the third day and helped shut down the store completely.

Consensus or not, strikes should be carefully and thoroughly prepared. In West Virginia, where a historic education victory kicked off the “Red for Ed” teacher rebellion in 2018, there were many months of strike preparation, including doing community outreach and developing rank-and-file organizing committees independent of the union leadership, with a clear program of demands.

This isn’t to say that strikes can’t be quickly organized when needed. In Marysville, the strike “came together pretty much overnight,” according to rank-and-file leader Katelyn McCoy, after two baristas were forced to run the entire store on their own for over six hours — one nine-months pregnant and the other on a 10.5-hour shift without breaks. But even when strikes develop quickly, workers should work in earnest to effectively organize themselves, as Marysville workers successfully did.

Short energetic strikes are usually best. This is because the pressures of strikes on workers, including the economic burden, are very real — if the strike is not moving forward and becomes stalled, the bosses will take advantage. It can be fatal to base a strike on the “one day longer, one day stronger” approach, as the Sand and Gravel leadership did in the recent unsuccessful five-month strike in the Seattle area.

Solidarity can play a key role in the success of a strike. The bosses want workers to feel isolated when they go on strike. We need the opposite: the widest possible working-class support. That’s why we’ve helped build rallies in Seattle to support Starbucks workers here, inviting coffee workers from around the region and country to speak and building wider support in the labor movement.

Finally, rank-and-file democracy is crucial. At JFK8, the Amazon Labor Union created a broad organizing committee of dozens of workers to ensure that workers had a real say in the key decisions of the unionizing drive. This kind of structure can be highly effective in developing the best fighting tactics and building worker engagement. ALU’s constitution also has strong democratic structures, even including a requirement that all its elected officials accept an average worker’s wage — a key block on the development of bureaucracy in a union, which is in turn critical to maintaining a class-struggle approach.

Rebuilding a Fighting Labor Movement

The strike is a crucial tactic, and there’s no way that Starbucks or Amazon will be unionized nationally without workers using it. But in the process of unionizing, the strike tactic must be combined with others to build broad, grassroots, public campaigns. Mass rallies, community outreach, national days of action, and other such tactics will also be essential.

As socialists, it is our role to help chart an alternative path alongside workers who want to be part of a serious fightback, and not abandon them to the cautious methods of labor leaders who seek to negotiate unity with the bosses.

Under capitalism, working people have been taught that they should keep their heads down, that they should not be divisive, and that they should be good team players (or “partners”) in their workplaces rather than organizing directly against the bosses for the needs of their class. In an all-out fight with the billionaire class, victory or defeat can be determined by whether workers are armed with class-struggle strategies and tactics — including being prepared to withhold their labor power in the struggle for their collective interests.

A huge space has opened up to rebuild a fighting labor movement in the United States. The need could not be more urgent, and history does not offer us endless opportunities. We need to make the most of this one.

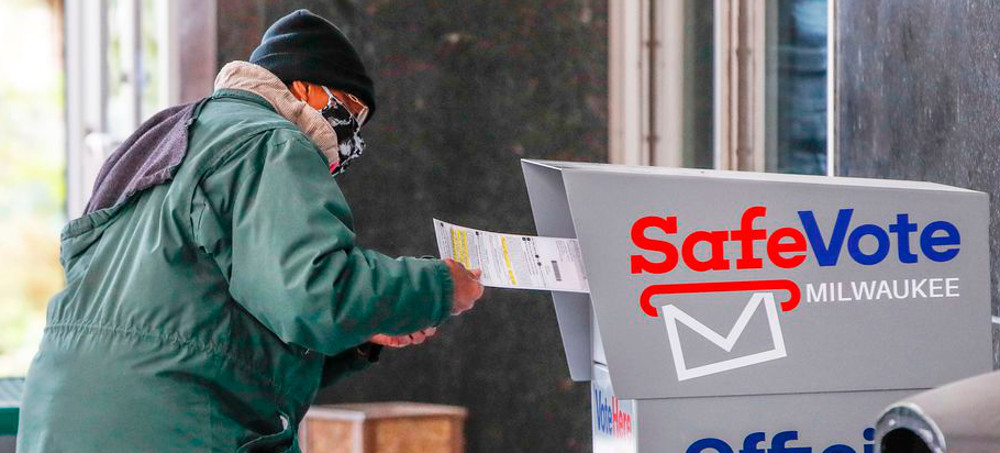

A woman deposits her ballot in an official ballot drop box in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on the first day of in-person early voting in the 2020 general election. The drop boxes have since been banned. (photo: Kamil Krzaczynski/Getty)

A woman deposits her ballot in an official ballot drop box in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on the first day of in-person early voting in the 2020 general election. The drop boxes have since been banned. (photo: Kamil Krzaczynski/Getty)

The pandemic helped improve accessibility, but new election barriers in states like Wisconsin are rolling back gains for thousands of voters with disabilities.

When it is election season, however, she is unable to get her ballot into a mailbox. She has relied on relatives, a caregiver, or a friend to physically place her ballot in one. Now, under a recent Wisconsin circuit court ruling mandating that only a voter, and not a designee, can submit an absentee ballot, it has effectively become illegal for Chambers to vote.

“Since I have had my disability, I have always voted absentee ... because the barriers to get to the voting polls in time can be very difficult for me,” she wrote in testimony used in court and compiled by the federally funded nonprofit Disability Rights Wisconsin.

Testimony from Chambers and other Wisconsin voters describing the painstaking effort they must make to cast a vote in their state helps paint a picture of how new ballot restrictions nationwide are presenting novel challenges for voters with disabilities. A concerted nationwide effort on the part of Republicans, including in Wisconsin, has sought to roll back voting expansions through shortening voting hours, limiting absentee and early voting, limiting dropbox availability, establishing additional voter ID requirements for mail-in voting, and more. All of these measures make it harder for people with disabilities to vote, voting rights activists and experts told Vox, and the efforts are already having an outsize effect.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 26 percent of American adults live with some type of disability; many have mobility issues or cognition difficulties, and have trouble living alone. Despite these challenges, people with disabilities made significant voter turnout gains in 2020, due in part to nationwide efforts to make it easier to vote during the pandemic. As many as 17.7 million people with disabilities (62 percent of all voters with disabilities) reported voting in the November 2020 general election, up from 16 million (56 percent) in the 2016 general election, according to data from the Program for Disability Research at Rutgers University and the US Election Assistance Commission.

Voting by mail increased during the pandemic for people with and without disabilities, but people with disabilities were more likely to use the option: Just over half of voters with disabilities voted by mail before Election Day, compared to 40 percent of voters without disabilities, according to the Rutgers research.

In Wisconsin, however, ballot assistance was banned for the state’s April 5 primary, overwhelming a voter hotline set up by the advocacy group Disability Rights Wisconsin with calls from voters questioning whether their ballots would be counted.

“These restrictions are problematic on so many levels, not only for people with disabilities but especially for people with disabilities, and there’s a lot at stake with our next election coming up in August,” said Barbara Beckert, the director of external advocacy for southeastern Wisconsin for Disability Rights Wisconsin, which staffs the hotline and informs voters with disabilities of their rights, and audits polling locations.

In Wisconsin, a bipartisan effort to distribute more than 500 drop boxes as a secure way to cast absentee ballots also led to high voter turnout — more than 72 percent of the state’s voting-age population voted — for the 2020 general election. In June 2021, two voters, backed by the conservative group Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, sued the Wisconsin Elections Commission in Teigen v. Wisconsin Elections Commission, challenging the legality of drop boxes for absentee voting. The plaintiffs asked the court to ban drop boxes across the state and require voters to mail or return their own ballots directly to clerks. Under their interpretation of the Wisconsin statute that concerns absentee ballots, a voter must physically mail or deliver only their own ballot, and not that of someone else.

The voters who filed the lawsuit cited a fear of “ballot harvesting,” a term linked to vote-by-mail conspiracy theories that conservatives use to describe ballot collection and submission by a person or organization on behalf of voters. It is illegal to ballot harvest or “ballot traffic” in states such as Georgia and Arizona; in January, a conservative state judge sided with the Wisconsin plaintiffs, blocked the use of drop boxes, and prohibited people from returning ballots on behalf of someone else in Wisconsin, too.

Despite appeals by organizations including Disability Rights Wisconsin, the state Supreme Court eventually upheld the lower court’s decision, allowing the prohibitions to take effect for the April 5 election. A final ruling in the case is expected in June, and the outcome could affect two important August primary races: Democratic Gov. Tony Evers and Republican Sen. Ron Johnson are both seeking reelection.

“2020 was probably the most accessible election we’ve seen,” said Michelle Bishop, the voter access and engagement manager at National Disability Rights Network. “We made a lot of changes in response to Covid, which also happened to be best practices for making voting more accessible for people with disabilities. But we are still in the period of pushback to all of those positive changes.”

It’s only gotten harder for people with disabilities to vote

Wisconsin is not the only state that has implemented new restrictions that make it particularly difficult for voters with disabilities to access the ballot and cast a vote.

During its March primary, Texas rejected nearly 23,000 mail-in ballots, or about 13 percent of ballots cast, according to an Associated Press investigation, an unusually high number considering that the number of rejected ballots during a general election typically doesn’t surpass 2 percent. Most of the ballots were rejected on the grounds that the voters failed to meet identification requirements established under Texas’s new voting law. The law requires that voters provide their driver’s license number or the last four digits of their Social Security number when applying for a mail-in ballot, and write that same number on the ballot when sending it in. Democrats have argued that the new ID requirement simply makes it harder to vote, and disability rights activists point out how the requirement has already affected voters with disabilities.

Florida and Georgia have adopted similar bills that impose restrictions on mail-in voting. More states may join the effort. According to the Brennan Center, a liberal nonprofit law and and public policy institute, at least 18 bills in five states would require voters to provide their driver’s license number, Social Security number, or voter record number when applying for a mail-in ballot. One Arizona bill would essentially create the same effect as the Wisconsin ban, requiring voters to present an ID when returning a mail-in ballot. The ID would need to be that of the person turning in the ballot.

“We are looking at a number of states that are putting restrictions on ballot drop boxes, rolling back curbside voting, preventing the passing out of food and water in lines, adding new ID requirements, shortening timelines for submitting and requesting mail-in ballots, and restricting who can drop off a ballot,” said Sarah Blahovec, the voting and civic engagement director at the National Council on Independent Living. “These changes give people with disabilities fewer options, which then compounds with other issues as well. There are disabled people in poor and minority communities who are impacted even more than if you consider it just from a disability perspective and don’t consider these other factors.”

At every turn, people with disabilities face barriers that make it harder to vote. They may not have access to transportation, they may have difficulty getting out into their communities because of a health condition, or their polling places may not be accessible. Many people with disabilities are non-drivers.

In Wisconsin, 30 percent of the population are non-drivers, which means they often don’t have a driver’s license, and the state does not have automatic voter registration. For those for whom transportation is not a barrier, they must navigate the limited hours of the Division of Motor Vehicles, which is one place they register to vote. If a voter lives in a rural area, it might take them 45 minutes in each direction to get to a DMV that is only open during the day. While Medicaid covers transportation for medical appointments, it doesn’t cover visits to the DMV. Then, multiple documents, such as birth certificates and Social Security cards, are required to begin the process of getting an ID.

“This is a huge problem for people with disabilities who may be living in a group home or in an environment where they don’t have a lot of control over their lives,” Beckert said. They may not have control or even possession of their documents.

Voters who identify as “indefinitely confined,” an official designation recognized by the state, have also been threatened by Republicans’ wish to change these voters’ entitlements. Because of disability, age, physical illness, or other infirmity, these voters always need to vote absentee. This group is sizable in Wisconsin, because the state has many more people with significant disabilities (those with severe cognitive or physical impairment that limits their ability to function independently) living in the community instead of in assisted living facilities. Because they typically vote absentee and are not drivers, Wisconsin lawmakers determined they don’t need to provide a photo ID to vote. But challenges to Wisconsin’s laws, like Republicans’ SB 204 bill, introduced in the state Senate last year, allege that this allowance leaves the door open to fraud.

Similarly, conservative operatives were outraged that people in assisted living facilities were automatically mailed ballots during the pandemic without the supervision of a special voting deputy, who would have overseen the process. The pandemic prevented these supervisors from visiting such facilities. Operatives have contended that the people in assisted living should not have been sent ballots without supervision due to the alleged potential for fraud. “It’s discriminatory to suggest that because someone lives in a nursing home or because they have some kind of cognitive loss, they can’t vote. That is not what Wisconsin law says,” Beckert said.

Like other activists across the country who are fighting restrictive new voting laws in court, Wisconsin activists who appealed the lower court’s ruling have argued that the restrictions violate federally protected rights. For example, the right to request that someone else return an absentee ballot is protected by Section 208 of the Voting Rights Act, and the Americans with Disabilities Act states that “no qualified individual with a disability shall, by reason of such disability, be excluded from participation in or be denied the benefits of the services, programs, or activities of a public entity, or be subject to discrimination by any such entity.” That language makes bans on drop boxes or voter assistance illegal, activists say. But winning on these grounds in court will take time as lawsuits work their way through judicial hoops.

The voting rights long game

While the right to vote is under siege, disability rights activists say they’re focused on thinking about creative solutions for expanding access to the ballot box even when their outlook on the present is bleak. Speaking out about policy recommendations — and not just about the many challenges that voters face — is key, activists told Vox.

“After 2020, we thought we’d be spending so much more of our time promoting policies to make our elections more accessible and inclusive,” Beckert said. “People with disabilities have historically faced a lot of barriers to exercising their right to vote, but things moved in a direction that we didn’t anticipate, so we’d like to get a chance to put our recommendations out there.”

Beckert’s list of policy recommendations is long, and touches several categories, including how to effectively train election administrators to support voters with disabilities, loosening voter ID requirements, improving transportation options and accessibility at polling locations — ideas that may already be in effect in other states.

Because Wisconsin’s elections are decentralized, the training that’s provided to poll workers varies, with many of them unfamiliar with the rights and accommodations that voters with disabilities are entitled to, Beckert told Vox. For example, voters with disabilities are entitled to having an assister complete their ballot, and to using an accessible voting machine and curbside voting.

On a national scale, activists have also been advocating for automatic voter registration, which could enhance the accuracy of voter registration rolls by reducing the number of voters who have to update their voter registration with clerks or at their polling location on Election Day. In the same vein, activists reject any push that would ask election clerks to match a driver’s license signature with a voter’s signature during registration or the absentee voting process. According to Beckert, many disabilities can lead people to change their signature over time. Voters with disabilities might also use electronic equipment that could inadvertently alter their signature.

At the National Council on Independent Living, Blahovec also has policy recommendations, which are an even broader attempt to help national lawmakers recognize how commonly accepted voting practices limit voters with disabilities. The Freedom to Vote Act, Democrats’ landmark voting legislation that was defeated in January, would have mandated paper ballots. The mandate would have pleased election security advocates, but would have disenfranchised voters who are blind or have low vision or other print-related disabilities.

“The disability community has pushed for a carve-out and for accessible fully electronic systems but have been unable to get that into the legislation,” Blahovec said. Another major problem with systemic inaccessibility is that efforts to improve accessibility are just not funded, Blahovec said. The Accessible Voting Act, which was introduced and stalled in the House in 2021, would have given states grants to improve accessibility to voting. “When accessibility isn’t funded, people with disabilities are left behind, and states don’t even have the resources to fix the issues,” Blahovec said.

Voting rights are about the long game, activists told Vox. “As a country, we are moving in the right direction, and I try to keep that in mind in the moments when there is pushback to progress,” said Bishop, of the National Disability Rights Network. “These aren’t battles that we are all going to win today.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-VT, speaks at a rally outside an Amazon facility on Staten Island in New York. Sanders is pressuring President Biden to cut off anti-union companies from federal contracts. (photo: AP)

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-VT, speaks at a rally outside an Amazon facility on Staten Island in New York. Sanders is pressuring President Biden to cut off anti-union companies from federal contracts. (photo: AP)

“How you handle Manchin, how you handle Sinema and the other conservative Democrats is one of the challenges that the Democrats have got to deal with,” Sanders, who caucuses with the Democrats, said in a new Vanity Fair article. “But the current strategy is an absolute political failure.”

Sinema and Manchin, among the chamber’s most conservative Democrats, have repeatedly blocked or forced scale-backs of President Biden’s top priorities. After months of negotiations, Manchin outright rejected the Build Back Better bill, a sweeping package to confront climate change and expand the social safety net, while both senators blocked voting rights legislation.

“What happened is you had people like [Manchin and Sinema] who sabotaged our efforts, what we were trying to do,” Sanders told Vanity Fair. “Ever since then, the Democratic Party has stumbled and fallen further and further behind.”

Manchin’s and Sinema’s offices didn’t respond to The Hill’s request for comment.

Sanders’s opinion of his two colleagues is no secret. During a December appearance on MSNBC, Sanders blasted the duo as “arrogant” for blocking Democratic priorities.

“I do not respect the arrogance of any member of the Senate who says, ‘You know what? I’m going to torpedo this entire bill, supported overwhelmingly by the American people,'” Sanders said. “You’ve got two people saying, ‘You know what? Hey, if you don’t do it my way — I don’t care what the president wants, I don’t care what 48 of my colleagues want — it’s my way or the highway.’”

“That, I regard as arrogance,” he added.

Under Biden’s nearly $2 trillion proposal, Build Back Better would have tackled several progressive priorities including implementing universal prekindergarten, creating a federal paid family leave program, expanding Medicaid coverage and lowering prescription drug costs.

However, with the evenly split Senate, Democrats could not afford to lose a single vote, giving each member of the caucus an outsized role in negotiations, as Biden conceded in a CNN town hall last year.

“Look, you have 50 Democrats, every one is a president. Every single one,” he said. “So you got to work things out.”

Lawmakers recently have expressed hope about rebooting talks on a scaled-back version on Build Back Better, though time is running short with Republicans expected to take control of the House in November’s midterm elections.

Land Defenders stand atop construction equipment. (photo: Columbia Journalism Review)

Land Defenders stand atop construction equipment. (photo: Columbia Journalism Review)

In western Canada, land defenders keep filming

Over the next two days, the Gidimt’en Checkpoint posted a series of updates as RCMP officers enforced the court injunction. Those posts relayed crowdsourced reports of police actions, photo and video updates from the ground, and requests for solidarity actions—from hosting rallies to pressuring pipeline investors to calling provincial and federal government officials—to the account’s twenty-nine thousand followers. Amanda Follett Hosgood, a reporter for The Tyee, an outlet based in British Columbia, wrote on Twitter at the time, “If you’re not already following @Gidimten this is the best way to get updates…”

Several people on-site recorded the arrests of land defenders. In one video, police in tactical gear advance upon a group of defenders huddled in song and prayer around a Wet’suwet’en elder, and arrest them one by one. A voice can be heard yelling, “I’m media! I’m media!” Near the video’s end, a caption reads, “15 people were arrested including two Wet’suwet’en elders, 3 Haudenosaunee members, 3 Legal Observers, and one journalist.”

Another, shot by Michael Toledano, a filmmaker working on a documentary for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, begins inside a tiny, shed-size cabin, where he and Amber Bracken, a photojournalist for The Narwhal, are with five land defenders. In the footage, police can be seen scouring the camp. There’s a din of shouting, barking, and machinery in the background; then comes the crack of an ax against a door, followed by the sound of a chainsaw as it cuts through the door of the cabin. A rifle is visible through the gap in the door. “Get your fucking gun off me!” Sleydo’, a land defender, says. The rifle stays on the group. And then, one by one, those inside the cabin, including Toledano, are grabbed by police, forced out of the cabin, and arrested. Following his release from custody, Toledano wrote that he would be “publishing this footage as soon as possible.”

Both videos were released via the Gidimt’en Checkpoint Twitter account in the days following the arrests. On the morning of November 24, the account posted a two-minute edit of Toledano’s footage, along with text offering a longer, unedited clip to “news organizations that want access.” By day’s end, video of the arrests led news outlets across Canada and beyond, including the Toronto Star, Democracy Now, and a host of others. The CBC aired nearly seven minutes of film by Toledano, during which Toledano is heard telling a police officer that he is “filming a documentary for CBC television.” “No problem,” an officer replies. “You’re under arrest.”

Gidimt’en Checkpoint was established in December 2018 by Wet’suwet’en land defenders—a group of people including Wet’suwet’en citizens, allies from other First Nations, and non-Indigenous supporters—who are opposed to the construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline and want to halt unauthorized incursions and construction on territory that was never legally handed over to Canada. Since the checkpoint’s establishment, however, ongoing coverage of the Wet’suwet’en resistance has been hard to come by. The land-defense camps themselves are remote, located off logging roads, with no reliable cell service. Exclusion zones set up by the RCMP—tactics that have been challenged in court—further limit access to the camps, including for reporters. National media has mainly prioritized coverage of the resistance when conflict flares; local media, which includes a handful of rural town papers owned by one publisher, has on occasion dubbed the land defenders “dissidents” and, like other outlets around the country, relied on syndicated content from the Canadian Press.

As it is, newsrooms don’t necessarily prioritize sustained, nonviolent opposition in editorial decision-making. “The public eye wants violence and destruction, but turns away from our quiet resistance,” wrote Anne Spice, a Tlingit sociologist, and Denzel Sutherland-Wilson, a Gitxsan land defender, in the New Inquiry in 2019. “People are less interested in our governance systems operating as they should.”

Though the lands of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation are unceded—a fact recognized by Canada’s Supreme Court in a 1997 ruling—conflicts between the Wet’suwet’en and industry, provincial, and federal forces have been unfolding for years. Media coverage was largely reserved for brief moments of arrests and physical engagement. That began to change in February 2020, when RCMP raids on Wet’suwet’en territory drew national media attention and sparked solidarity movements across the country.

“There was this buildup of militarized RCMP that happened, and people could see it, so that gave mainstream media plenty of time to get organized and get reporters out there,” Franklin López, an independent filmmaker, says. RCMP officers also detained or turned away several journalists who were present to document Wet’suwet’en opposition; since then, similar dynamics have played out between law enforcement authorities and journalists at land-defense protests around the country.

Through its social media accounts, the Gidimt’en Checkpoint alerts newsrooms and others to updates from the ground. A post from October 2020 shows hunting efforts interrupted by encounters with pipeline employees and police; others, from late last year, show the peaceful occupation of a drill-pad site, where a cabin has been constructed, or warn of archaeological sites imperiled by the pipeline’s path. Such updates may not necessarily spur coverage from the broader Canadian media ecosystem; still, they are often the only lens into the Wet’suwet’en land-defense community between moments of heightened conflict. (The Gidimt’en Checkpoint website also includes a Wet’suwet’en 101 media backgrounder for journalists trying to get up to speed on the struggle.)

The content published by Gidimt’en Checkpoint comes together from different sources at camp, Wickham says. Some is from trained videographers; some is created by people using cellphone cameras, GoPros, or scrappy camcorders. Once footage is compiled, it goes through a review process, during which a few people handy with editing consult with Wet’suwet’en leadership on key moments to include. Given time limits on certain platforms, there’s pressure to keep video reports concise and hard-hitting. Editing is carried out on-site, in tiny cabins; edited videos are uploaded via satellite internet.

There’s a “colossal distance” between the Gidimt’en Checkpoint resources and “an extractive industry that has probably millions of dollars in the media budget,” Wickham says. (The Coastal GasLink project is valued at $6.6 billion.) The land defenders at Gidimt’en Checkpoint, she says, are working with cellphones and “laptops held together with duct tape.”

Neighboring First Nations maintain their own media projects, some in solidarity with their Wet’suwet’en neighbors. In the town of New Hazelton, a few hours north of Gidimt’en in Gitxsan Nation territory, Gitxsan allies have set up rail blockades and a community camp. The camp, established on November 18, 2021, has also been raided by the RCMP. In November, officers arrested Denzel Sutherland-Wilson, who coauthored the New Inquiry essay. A land defender was present to record the arrest; in footage, Sutherland-Wilson can be heard yelling that he can’t breathe. Footage of the arrest was shared on a Gitxsan account called Git’luuhl’um’hetxwit Media, which often shares @Gidimten’s work and vice versa. Within days, several Canadian news outlets covered Sutherland-Wilson’s arrest, embedding the video footage in their stories.

“It honestly feels at times like you’re fighting an information war,” says Kolin Sutherland-Wilson, Denzel’s brother, a Gitxsan land defender and spokesperson for his wilp. “Often documenting on social media is our only avenue for actually telling the stories of what we’re dealing with.”

Kolin, who has been involved in land defenders’ documentary efforts, taught himself to edit video on Premiere Pro, and has shared work through Git’luuhl’um’hetxwit Media. Rural communities in British Columbia around Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en are served by local papers; several are published by Black Press, whose founder, David Black, years ago met with a provincial press council to discuss his papers’ editorial policy and his own opposition to a treaty recognizing the Nisga’a Nation’s rights to its territory, and who once proposed construction of a bitumen refinery—a $13.2 billion project necessitating a pipeline like the one Coastal GasLink hopes to build—in Kitimat, on the British Columbian coast. While those papers have covered defenders’ opposition to the pipeline, including Denzel Sutherland-Wilson’s arrest, their publisher’s previous stances leave Kolin skeptical of their commitment to covering Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en sovereignty.

Earlier this year, Hosgood, the Tyee reporter, revealed that security personnel for Coastal GasLink had attempted to turn away journalists covering Gidimt’en. “Three years into the dispute that has made international headlines, seen dozens of people arrested and caused the high-profile three-day detention of two journalists taken into custody at this site in November, the person tasked with enforcing the injunction on behalf of Coastal GasLink appears not to understand its contents,” she wrote.

Hosgood is based in Smithers—about an hour and a half by car from the RCMP checkpoints near Gidimt’en, closer than many other reporters. She has traveled to the site on several occasions; on November 18, she made the trek to the logging road, where, she says, her efforts to gain access were delayed and initially rejected by an RCMP officer. When she was finally escorted up the logging road, it was just in time to see police processing the people they had arrested. She says she spent hours on Twitter refreshing @Gidimten for updates.

“They were the best source of information,” Hosgood says. “Having a video of what took place gives you a starting point: it helps you visualize what happened and determine what questions need to be asked.”

Last week, posts from the @Gidimten account detailed a series of recent RCMP visits to the site. Following the posts, Matt Simmons—a journalist for The Narwhal who, like Hosgood, is based in Smithers—traveled to the site to speak with land defenders, narrowly missing a visit by RCMP officers. “During times when the conflict between land defenders, industry, and RCMP escalates, the presence of people filming interactions on the ground and sharing them widely helps inform my decision on when I should be physically present to document,” Simmons tells CJR via email. “Gidimt’en Checkpoint social media posts—especially video footage—have repeatedly proved useful to my reporting, in that it’s a relatively easy way to stay informed on ongoing developments, without having to invest a significant amount of time heading out to the location in-person.”

Hosgood adds that the information shared via the @Gidimten account and others like it can be crucial in a conflict whose participants don’t necessarily share information readily. She says she filed a Freedom of Information Act request to access RCMP body-camera footage from the November arrests, but so far has not heard back. “Gidimt’en and other social media accounts like that are providing information that other sources just don’t,” she says.

Accounts such as @Gidimten provide some measures of safety and accountability, Wickham, the checkpoint media coordinator, says. They are also the only way, sometimes, to tell the news. “We’re left with the folks that are actually on the ground, being arrested, and being invaded to document in whatever way they’re able,” she says.

'Warming waters are cooking creatures in their own habitats.' (photo: Shutterstock)

'Warming waters are cooking creatures in their own habitats.' (photo: Shutterstock)

Warming waters are cooking creatures in their own habitats. Many species are slowly suffocating as oxygen leaches out of the seas. Even populations that have managed to withstand the ravages of overfishing, pollution and habitat loss are struggling to survive amid accelerating climate change.

If humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase, according to a study released Thursday, roughly a third of all marine animals could vanish within 300 years.

The findings, published in the journal Science, reveal a potential mass extinction looming beneath the waves. The oceans have absorbed a third of the carbon and 90 percent of the excess heat created by humans, but their vast expanse and forbidding depths mean scientists are just beginning to understand what creatures face there.

Yet the study by Princeton University earth scientists Justin Penn and Curtis Deutsch also underscores how much marine life could still be saved. If the world takes swift action to curb fossil fuel use and restore degraded ecosystems, the researchers say, it could cut potential extinctions by 70 percent.

“This is a landmark paper,” Malin Pinsky, a Rutgers University biologist who did not contribute to the paper, said in an interview. “If we’re not careful, we’re headed for a future that I think to all of us right now would look quite hellish. ... It’s a very important wake-up call.”

The world has already warmed more than 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) since the preindustrial era, and last year the oceans contained more heat energy than at any point since record-keeping began six decades ago.

These rising ocean temperatures are shifting the boundaries of marine creatures’ comfort zones. Many are fleeing northward in search of cooler waters, causing “extirpation” — or local disappearance — of once-common species.

Polar creatures that can survive only in the most frigid conditions may soon find themselves with nowhere to go. Species that can’t easily move in search of new habitats, such as fish that depend on specific coastal wetlands or geologic formations on the sea floor, will be more likely die out.

Using climate models that predict the behavior of species based on simulated organism types, Deutsch and Penn found that the number of extirpations, or local disappearances of particular species, increases about 10 percent with every 1 degree Celsius of warming.

The researchers tested their models by using them to simulate a mass extinction at the end of the Permian period, when catastrophic warming triggered by volcanic eruptions wiped out roughly 90 percent of all life on Earth. Because the models successfully replicated the events of 250 million years ago, the scientists were confident in their predictions for what might happen 300 years in the future.

Penn and Deutsch’s research revealed that most animals can’t afford to lose much more than 50 percent of their habitat — beyond that number, a species tips into irreversible decline. In the worst-case emissions scenarios, the losses would be on par with the five worst mass extinctions in Earth’s history.

These changes are already starting to unfold. In the 1980s, a heat wave in the Pacific eliminated a small, silvery fish called the Galapagos damsel from the waters off Central and South America. A hot spot along the coast of Uruguay has driven mass die-offs of shellfish and widespread shifts in fishermen’s catch. Japanese salmon fisheries have plummeted as sea ice retreats and warmer, nutrient-depleted waters invade the region.

The danger of warming is compounded by the fact that hotter waters start to lose dissolved oxygen — even though higher temperatures speed up the metabolisms of many marine organisms, so that they need more oxygen to live.

The ocean contains just one-sixtieth as much oxygen as the atmosphere, even less in warmer areas where water molecules are less able to keep the precious oxygen from bubbling back into the air. As global temperatures increase, that reservoir declines even further.

The heating of the sea surface also causes the ocean to stratify into distinct layers, making it harder for warmer, oxygenated waters above to mix with the cooler depths. Scientists have documented expanding “shadow zones” where oxygen levels are so low that most life can’t survive.

Deoxygenation poses one of the greatest climate threats to marine life, said Deutsch, one of the study’s co-authors. Most species can expend a bit of extra energy to cope with higher temperatures or adjust to rising acidity. Even some corals have found ways to keep their calcium carbonate skeletons from eroding in more acidic waters.

“But there’s no price organisms can pay to get more oxygen,” Deutsch said. “They’re just sort of stuck.”

This climate-driven marine die-off is just one piece of a broader biodiversity crisis gripping the entire globe. A recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that warming has already contributed to the disappearance of at least 400 species. A separate U.N. panel has found that about 1 million additional species are at risk of extinction as a result of overexploitation, habitat destruction, pollution and other human disruption of the natural world.

A comprehensive new assessment published Wednesday in the journal Nature showed that more than 20 percent of reptile species could vanish. Turtles and crocodiles are most at risk, with more than half of each group at least vulnerable to extinction in the near future.

The consequences for communities that rely on reptiles for food, pest management, culture and other services could be profound.

“If we start messing up ecosystems and the services they provide, it has knock-on effects,” said assessment co-author Neil Cox, manager of the biodiversity assessment unit at the International Union for Conservation of Nature. “I think threats to biodiversity are as severe as climate change, we’re just underestimating them.”

Yet the two crises are closely intertwined, added Blair Hedges, an evolutionary biologist at Temple University and contributor to the reptile assessment. Climate change can accelerate the demise of populations already destabilized by habitat degradation or hunting. Ecosystems that lose key species may be less able to pull carbon out of the atmosphere or buffer against climate impacts.

The researchers highlighted the plight of the Virgin Gorda least gecko, a thumbnail-size reptile that dwells in moist pockets of soil on Caribbean hillsides. The creation of national parks on islands where the gecko is found helped avert habitat loss that could have doomed the species. But now its home is drying out from climate change, once again raising the specter of extinction.

“If you have multiple threats ... working together, often even when you think one of them is under control, then the other one turns out to be even more of a threat,” Hedges said.

Though the danger to animals — and the humans who depend on them — is undeniably dire, Pinsky, the Rutgers biologist, urged against giving in to despair.

In an analysis for Science that accompanied Penn and Deutsch’s report, he and Rutgers ecologist Alexa Fredston compared marine animals to canaries in a coal mine, alerting humanity to invisible forces — such as dangerous carbon dioxide accumulation and ocean oxygen loss — that also threaten our ability to survive. If people can take action to preserve ocean wildlife, we will wind up saving ourselves.

“It’s scary, but it’s also empowering,” Pinsky told The Post.

“What we do today and tomorrow and the rest of this year and next year can have really important consequences,” he added. “This is not ‘once in a lifetime’ but maybe ‘once in a humanity’ moment.”

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.