Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The party has settled on a new playbook: shifting right and hoping demoralized voters are repulsed by Republicans

This isn’t just a fleeting tactic. This is now The Formula of Democratic Politics™, one with mixed results. In 2016, the Senate Democratic leader, Chuck Schumer, publicly bragged that the Formula would result in flipping enough moderate voters to secure a victory – just before the Formula’s epic failure handed Donald Trump the presidency.

Four years later, though, the Formula seemed to work – Democrats united to quash the primary against the quasi-incumbent Joe Biden, and Trump’s horrific first term allowed Biden to eke out a win with a flaccid campaign based on a meaningless platitude about “the soul of America”.

Now Democrats seem intent on using the Formula again – only this time, it’s even more risky because this is not a race against a sitting Republican president. In 2024, Biden is the incumbent playing defense, and data suggest that there’s not much enthusiasm for his re-election campaign, even among his own party.

A stat from the Washington Post illustrates this larger problem: “Biden has less support for renomination among Democrats than Trump, Obama and Clinton had from their parties,” the newspaper reports, noting that surveys show just 38% of Democrats want Biden to be the party’s nominee in 2024. CNN’s polling shows that right now, just one-third of Americans believe Biden deserves to be re-elected – lower than where Trump was at around this stage of his first term.

If there was a healthy, genuinely democratic culture among the Democratic party’s political class, the response to the prospect of depressed voter enthusiasm might be a serious primary challenge. There might be a traditional top-tier candidate – maybe a senator, a governor, or even a member of the House – who is both ambitious enough to run for president and worried enough about a Biden failure in a general election against Trump.

Such a primary would serve the additional benefit of testing Biden’s own re-election viability, and making sure he can handle the rigors of a campaign before he’s already the nominee.

But that hasn’t happened. The response has been the Formula.

First, Biden and Democratic leaders have rejected the FDR strategy of winning elections by making a show of delivering for the working class. They have instead made a show of putting their boots in the eye of dissatisfied voters as a way to brandish their “centrist” (read: corporate) credentials.

After a very good American Rescue Plan momentarily helped millions of people and boosted Biden’s standing among voters, Democrats cut off pandemic aid, jacked up taxes on the working class, stomped out a rail strike, expanded fossil fuel drilling amid the climate emergency, demagogued the crime issue, and reappointed Trump’s worker-crushing Federal Reserve chair – all while abandoning the minimum wage and healthcare promises they made in 2020. And then they spiked the football by bailing out Silicon Valley Bank tech moguls while the government moved to force up to 15 million people off Medicaid.

With voters now understandably ticked off, here comes the Formula’s primary-crushing phase.

There was the decision to move the first Democratic presidential primary to South Carolina – a state widely seen as a place where the party machine has the best chance to control the outcome against insurgent candidates.

More recently, there’s the effort to shut down the discourse: though a Fox News survey shows 28% of Democrats already saying they will vote against Biden in a primary contest, the Washington Post reports: “The national Democratic party has said it will support Biden’s re-election, and it has no plans to sponsor primary debates.”

So far, this phase of the Formula has been successful. Though Marianne Williamson and Robert F Kennedy Jr, are promising primary challenges, no elected official in the party seems willing to vigorously support even the concept of a primary, much less run in one.

No doubt every Democratic officeholder is deterred by the cautionary tale of Senator Bernie Sanders, who was shamed for the crime of momentarily considering a primary challenge to Barack Obama while the incumbent was bailing out banks amid the foreclosure meltdown. For his part, Sanders provided an early Biden re-election endorsement, not even holding out for any policy concessions.

So far, this part of the Formula has been successful in manufacturing a sense of inevitability and creating the illusion that there is no other path – even if voters might want one. As the Washington Post’s headline put it: “Democrats reluctant about Biden 2024, but they see no other choice”. Or as Sanders told MSNBC about his Biden endorsement: “I don’t think one has many alternatives here.”

Assuming Biden is the nominee, the Formula’s final phase will probably be anchored in Schumer’s 2016 assumption. Democrats will presume that come general election time, disgust with the Republican nominee will cure all the discontent, demoralization and disillusionment sown by a feeble left-punching incumbent and by the party’s heavy-handed primary suppression tactics.

Maybe that’s what ends up happening. Maybe voters will see the Republican nominee as so flagrantly grotesque that Biden will get four more years. But there’s mounting evidence that the opposite could happen, and that 2024 could be more like 2016 than 2020.

That’s hardly surprising. As gross as Republican politicians are, Democrats’ formula may not be sustainable over the long haul. There may be only so long that a party can ignore and suppress mass discontent and then just hope the other party’s extremism generates revulsion.

As FDR once warned: “The millions who are in want will not stand by silently forever while the things to satisfy their needs are within easy reach.”

READ MORE  Protesters clashed with security forces across France on Monday. (photo: Reuters)

Protesters clashed with security forces across France on Monday. (photo: Reuters)

Unions had been hoping for a vast turnout across France for the May 1 protests to further rattle Macron, who has been greeted by pot-bashing and jeers as he toured the country seeking to defend the reforms and relaunch his second mandate.

Macron last month signed a law to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64, despite months of strikes against the bill.

In Paris, radical protesters threw projectiles at police and broke windows of businesses such as banks and estate agents, with security forces responding with tear gas and water cannon, AFP correspondents said.

One policeman, hit by a Molotov cocktail, has suffered severe burns to the hand and to the face, Paris police told AFP. The police said 46 people have been arrested in the capital alone so far.

Police had been given a last-minute go-ahead to use drones as a security measure after a Paris court rejected a petition from rights groups for them not to be used.

Police used tear gas in Toulouse in southern France as tensions erupted during the demonstrations,while four cars were set on fire in the southeastern city of Lyon.

In the western city of Nantes, police also fired tear gas after protesters hurled projectiles, AFP correspondents said. The windows of Uniqlo clothing store were smashed.

"Even if the vast majority of demonstrators were peaceful, in Paris, Lyon and Nantes in particular the police face extremely violent thugs who came with one objective: to kill cops and attack the property of others," said Interior Minister Gerald Darmanin on Twitter.

The CGT union said 550,000 people had turned out in Paris for the protests and 2.3 million across France. Government estimates, likely to be far lower, are due later.

'Page not going to be turned'

Macron and his government have tried to turn the page on the months of popular discontent, hoping to relaunch his second term after the reform was signed into law.

"The page is not going to be turned as long as there is no withdrawal of this pension reform. The determination to win is intact," said CGT chief Sophie Binet at the Paris protest.

"The mobilisation is still very, very strong," added Laurent Berger, head of the CFDT union.

"It is a sign that resentment and anger are not diminishing."

Monday marked the first time since 2009 that all eight of France's main unions have joined in calling for protests.

Radical ecological activists from Extinction Rebellion earlier sprayed orange paint on the facade of the glitzy Fondation Louis Vuitton museum in Paris, which is backed by the LVMH luxury goods giant.

In a separate action by a different environmental protest group, activists sprayed orange paint around the Place Vendome in central Paris, known for its jewellery shops, targeting the facade of the ministry of justice.

'Red card' to Macron

France has been rocked by a dozen days of nationwide strikes and protests against Macron and his pension changes since mid-January, some of which have turned violent.

But momentum has waned at recent strikes and demonstrations held during the working week, as people appear unwilling to continue to sacrifice pay.

When Macron attended the final of the French football cup on Saturday, he was met with activists waving red cards.

Almost three in four French people were unhappy with Macron, a survey by the IFOP polling group found last month.

Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne, with Macron's support, invoked in March the controversial article 49.3 of the constitution to ram the pension reform through parliament without a vote in the hung lower house.

In the Place de la Republique where the march started in the French capital, a huge vest with the slogan "Macron resign" was fixed to the giant statue symbolising the French republic at its centre.

"The law has been passed but has not been accepted, there is a desire to show discontent peacefully to have a reaction in response that shows a certain level of decency," said Celine Bertoni, 37, an academic in the central city of Clermont-Ferrand.

"I still hope that we are going to be told it will be withdrawn," she added.

"Macron has the impression that as he was elected he has all the power! But I want him to cede his place to the people," added Karine Catteau, 45, in the western city of Rennes.

May Day demonstrations on a smaller and less fractious scale took place across Europe, including Spain where flag-waving demonstrators joined more than 70 rallies under the slogan: "Raise wages, lower prices and share profits".

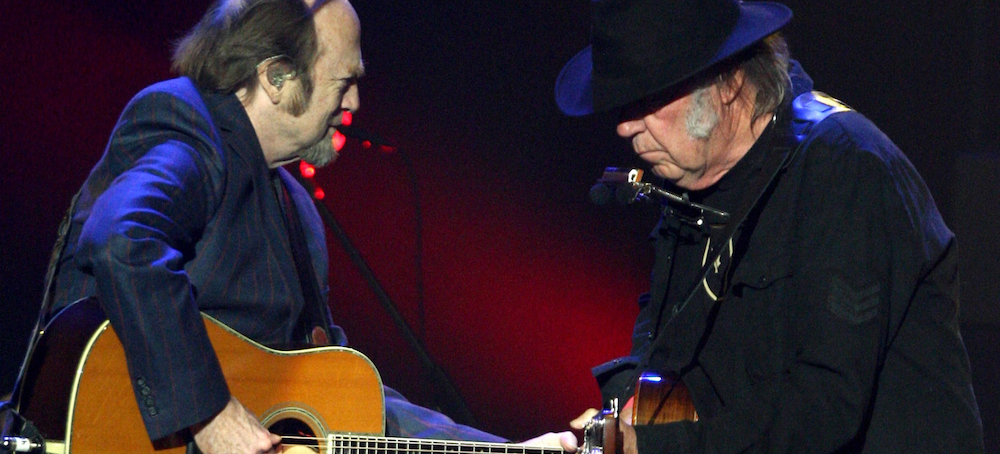

READ MORE  Musicians Stephen Stills and Neil Young perform on stage. (photo: Tommaso Boddi/WireImage)

Musicians Stephen Stills and Neil Young perform on stage. (photo: Tommaso Boddi/WireImage)

The rock legend discusses his all-star autism benefit, becoming an empty nester, and writing all those classic songs.

“Stephen was the most talented guy in CSNY,” the late David Crosby once told me. “He was the one who made those records happen. He was a force of nature. We fought a lot, but he usually won because he really knew how to make great records.”

At 78, Stills is, by his own admission, mellower and more thoughtful these days. But while he has slowed down considerably, the fire to make new music still burns hot, as he tells The Daily Beast below.

The two-time Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee is one of rock’s most enduring figures, having influenced generations with his songwriting and guitar playing, both as a solo artist and as a member of Buffalo Springfield, CSNY, and Manassas. In fact, his innovative approach to both acoustic and electric guitar, combined with distinctive harmonies, helped create the iconic “California sound” via classic compositions like “For What It’s Worth,” “Love the One You’re With,” “Helplessly Hoping,” “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” and “Carry On.” A true musician’s musician, Stills’ first solo LP is the only album to have ever featured both Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton.

Below, Stills talks about his Autism Speaks/Light Up The Blues benefit concert happening this weekend, the glory days of Buffalo Springfield and CSNY, his enduring friendship with Neil Young, and his new live album, Live At Berkeley 1971, taken from his legendary ’71 tour.

The Autism Speaks/Light Up The Blues shows have really grown over the last decade or so that you and Kristen [Stills, his wife] have been doing them. Tell me a little bit about how they started and why, and how you go about choosing the artists you ask to do them.

That’s three questions.

It is three. [Laughter.]

Yes, I can count like a horse. Well, my son Henry has Asperger’s [syndrome, a form of autism spectrum disorder], and that brought us into the world of the spectrum. And what I’ve discovered about the spectrum is that all the best people are on it, including me and most of my friends. So there’s a fine line between dysfunctional and interesting. And that’s not to make light of it. It was a brand-new thing, and just becoming a little epidemic, when he was first diagnosed. There was a lot of mystery and false assumptions about it. And so we’ve tried to lay those to rest. For instance, there is no cure—but there’s coping. And there’s lots that you can do to get to a normal life. There are varying degrees of it, of course, but like I said, if you’re not on the spectrum, well, all the best people are.

All the cool kids.

Yeah. Exactly.

And it seems in the decade you’ve been doing this, the perception has really changed, hasn’t it?

Yes, of course. But we can’t go to sleep. That’s one of the reasons we keep doing the shows. God knows it eats up half my year. My wife Kristen’s the producer, of course, and she’s gotten very adept at it, and she has a really good staff and everything. But getting artists this year was difficult because once the pandemic broke, everybody was like, “Oh, I want to work, I want to work, I want to work.” So a lot of people were booked. But a lot of people were playing fairly close to the gig [in Los Angeles], so we were able to nab them. So I guess it worked out.

Oh, any hints?

Willie Nelson, for one. And of course Neil Young, who sort of handed this off to me, the big charity thing. He wrapped up his Bridge School Benefit and said, “OK, Stephen, it’s your turn.” It really is a labor of love, but it’s a labor. It’s just a lot. And I’d especially like to reassure everybody that we’re raising money for the right organization and the right cause. But the place is small, so the thing sold out quick. We’ll have to do it again, but not till next year. But Willie has a show at the Hollywood Bowl, like, two weeks later, and Neil and I are going to drop in on his show, or so the Soviet commies would have us believe.

The disinformation campaign.

Yes, well, God help us if Neil Young became predictable. [Laughter.]

Well, let’s talk about that. That is an enduring partnership. Through all the ups and downs of Buffalo Springfield, and all the ups and downs of CSNY, you guys have always seemed to be able to work together in a musical partnership that really endures. Talk a little about why that partnership works so well from your point of view.

While we were children, we were mad. [Laughter.]

Hotheaded kids.

Yeah. It was Fort William, Ontario, which is now known as Thunder Bay. I was there with another little folk group. We were headliners and we did two shows on Saturdays, and this guy Gordy, who was the head of the thing, said, “Oh, I’ve got this pal I want to put in between you.” And it was Neil. He was doing exactly what I was doing in New York City, which was write folk songs with an electric guitar. [What] Neil was doing—it was fabulous. It was an eye-opener, and the band was sort of at loose ends, so we spent a week together, being introduced to each other and Neil introducing me to Canada, and we’ve been pals ever since. And that is an enduring thing. I mean, whatever happened, we were always pals.

Why do you think that relationship works so well?

Well, because when we met, we were children. We were too young to hold grudges and all that stuff. And we were never that competitive, because we were so different. Although there were a few moments on lead guitar, but… I don’t know. We don’t misunderstand each other. With everything else, Neil and I always knew who we were together. We’re brothers. And brothers, you know, disagree, and get back with each other. Crosby used to talk about how we butted heads, and I call them glancing blows, but we ended up numb-skulled due to them. And anyway, we didn’t spend enough time together! You know, I just saw, last night, for the first time in years, the director’s cut of Woodstock. And that’s the funniest fucking movie I’ve ever seen. At 78, looking back on that, I was rolling. I was howling at how naïve and how earnest we all were.

Baby-faced.

Yeah. Well, I miss that chin. [Laughter.] And I was also very, very liquid. And I had more hair. And could sing higher and lower. Actually, I guess I can sing lower now. But it was hilarious because I was thinking about [how], you know, they were trying to force negotiations with the Vietnamese, and I kept thinking to myself, “Well, they were quaking in their boots watching this shit.” [Laughter.] Just, you know, ironies abounded. It was at once startling, embarrassing, and exhilarating at the same time, to see all of us and what we were about back then. We were certainly earnest in our search for enlightenment.

Yeah. The beginning of the journey. It’s a beautiful thing. You’ve obviously performed as a duo with Neil many times, and although Graham will be in Pittsburgh on the night of the show, I have to imagine David’s spirit is going to loom large. Your son Chris, who was going to tour with David, will be there, and David’s son James Raymond will be performing. Talk about all the legacy that’s going to be on stage at this show.

We don’t have time.

Moving on! [Laughter.]

Because everybody booked themselves, we didn’t have a time to rehearse. But I’ve got Promise of the Real backing me, and those kids, I can’t say enough about them. They’re just great. They’ve got the one thing you can’t teach, which is attitude. They’re wide open and just positive. And nothing’s personal. So I can go through the nitpicking that it takes to put together some of my arrangements, and they don’t think twice about it, and they keep trying until we get it. It’s been real refreshing for me, because we’re all rusty. Neil and I spent the first two weeks of rehearsing, just the two of us, trying to remember all the Buffalo Springfield songs and then playing the records and going, “Oh my God. That wasn’t even close!” [Laughter.] So we’ll be doing a couple of those. It’s going to be neat. Of course, Neil’s more interested in acoustic stuff, and I’m committed to the band. I really like playing in electric music, as you know.

You brought up working with a band. I want to talk about the new live album. I’ve always loved your 1975 live album, which was actually taken from the same ’71 tour, but this album is much longer, and it’s warts and all. The performances are just as they were, so the feel and the vibe of it is amazing. Talk a little bit about that ’71 tour and why it took so long for this particular show to see the light of day.

Well, I’d forgotten about it. [Laughter.] Actually, we found it during a deep dive in the vault. And the first thing that struck us was that the recording is just great. The horn players, The Memphis Horns, were great. And Steve Fromholz, even though he was far too big to have as a partner for me—he was, like, [Mike] Finnigan-sized—he and I were a great blend on guitar. So this is the rest of that era, and yeah, some of the singing is like, I don’t know, I think I closely resemble an irritated dog. [Laughter.] And everything is real fast and it has a lot of energy. But it’s real powerful, too. Dallas Taylor [the drummer] had a lot to do with that feel. I would design the arrangements and then I would go back up in the balcony of the theater where we rehearsed and I’d watch while Dallas put the band through their paces. It was just fabulous. What a great ensemble.

I want to talk about your playing. I’m not sure younger musicians, or even younger fans, realize how highly regarded you were among your peers at the time. You were playing with Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton. You were in that league, as far as they were concerned. But does it bother you that younger fans may know you for the songs but might not think of you as a first-class guitarist first?

What do you mean, “were?” [Laughter.]

Well, you’re still here, so you get to tell the tale.

Well, I just spoke to Eric last week, so those relationships and that respect is still there. Now, I’m stealing from Jeff Beck—things like front tension and using the volume knob and really intricate stuff. Though I’ll never be as good as Jeff Beck. Ever.

Well, that’s a whole other…

We lost the greatest one of all, I think, this year.

Agree.

He was fabulous, although he was very hard to track down and play with because he was the original “I quit the band to work on my car.” He literally did that. “Where’s Jeff?” “He went home.” “Why?” “Well, he got the new small box Chevy and he wanted to build it and put it in the 32.” He was like that, meticulous and mercurial, but a great guy. We’re going to miss him. So anyway, there’s a lot of that in my playing now. I was pretty good back then, but I’m better now, and have some sober time under my belt, so I’m playing with a lot more clarity. I’ve picked up the banjo again. And I don’t get to play bass on stage, but I play a lot on the records. I love playing bass.

Talk a little bit about your songwriting process. There are some amazing songs on this record, songs from the Springfield records and CSNY, but your first couple of solo records and Manassas were really amazing achievements. Do you even remember your writing process from that time?

No. [Laughter.] I went on a tear. I mean, I had a decade of just nonstop productivity and then started running out of gas. Now, they come a little slower, but they’re a little more thoughtful and much better lyrically. Although some of those lyrics are pretty good, there’s some bad rhymes in there. Oof. There’s some stinkers. But that’s just me. I had a great time doing it, when the songs would just fall out. Some of them would happen in 15 minutes and some of them would happen in five months, as I was crafting them and trying to nail that illusive third verse.

I’d love to know what we might expect from you after this. Will you be working with Neil? Will you maybe be making another record? Maybe with Judy Collins again?

I have no idea. Honestly. I’m waiting for the next thing to appear. I mean, you can’t get me away from here, now that I’ve gotten used to being a homebody and sitting down with my children at night for dinner. But once the youngest finally goes away to college, then I’ll be an empty nester and I’ll probably be out there more. But travel just sucks these days. And the thought of a 14-hour bus ride is… frightening. But we’ll see what happens.

READ MORE  U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. (photo: Sarah Silbiger/Reuters)

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. (photo: Sarah Silbiger/Reuters)

Yellen acknowledged the date is subject to change and could be weeks later than projected, given that forecasting government cash flows is difficult. But based on April tax receipts and current spending levels, she predicted the government could run short of cash by early June.

"Given the current projections, it is imperative that Congress act as soon as possible to increase or suspend the debt limit in a way that provides longer-term certainty that the government will continue to make its payments," Yellen wrote in a letter to House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif.

The warning provides a more urgent timetable for what has been a slow-motion political showdown in Washington.

House Republicans are demanding deep spending cuts and other policy changes in exchange for raising the debt limit. President Biden has insisted he won't negotiate over the full faith and credit of the federal government.

On Monday, President Biden invited McCarthy to a meeting at the White House on May 9 with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, D-N.Y., along with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky. According to a White House official, Biden plans to use the meeting to stress the urgency of avoiding a default, while discussing a separate process to address government spending.

The government technically reached its debt limit in January, but Yellen said then that she could use emergency measures to buy time and allow the government to keep paying bills temporarily.

Other forecasters have predicted those emergency measures will last through midsummer or beyond. But the first two weeks of June have long been considered a nail-biter, before an expected inflow of quarterly tax payments on June 15.

Yellen urged lawmakers not to take any chances.

"We have learned from past debt limit impasses that waiting until the last minute to suspend or increase the debt limit can cause serious harm to business and consumer confidence, raise short-term borrowing costs for taxpayers, and negatively impact the credit rating of the United States," she wrote.

"If Congress fails to increase the debt limit, it would cause severe hardship to American families, harm our global leadership position, and raise questions about our ability to defend our national security interests," she added.

READ MORE  Strikes in Hollywood usually coincide with broader upheaval in the industry. (photo: Stephanie Diani/NYT)

Strikes in Hollywood usually coincide with broader upheaval in the industry. (photo: Stephanie Diani/NYT)

"The companies' behavior has created a gig economy inside a union workforce, and their immovable stance in this negotiation has betrayed a commitment to further devaluing the profession of writing," the WGA said in a statement Monday night. "From their refusal to guarantee any level of weekly employment in episodic television, to the creation of a 'day rate' in comedy variety, to their stonewalling on free work for screenwriters and on AI for all writers, they have closed the door on their labor force and opened the door to writing as an entirely freelance profession."

The WGA said picketing would begin Tuesday afternoon.

In a statement sent to NPR sent shortly before the announcement of the strike call, AMPTP said it had presented a package proposal to the guild "which included generous increases in compensation for writers as well as improvements in streaming residuals." According to that statement, the studio's alliance told the WGA it was prepared to improve that offer "but was unwilling to do so because of the magnitude of other proposals still on the table that the Guild continues to insist upon. The primary sticking points are 'mandatory staffing,' and 'duration of employment' — Guild proposals that would require a company to staff a show with a certain number of writers for a specified period of time, whether needed or not."

Since negotiations began in March, the WGA had been asking for higher wages, healthcare benefits and pensions, and in particular, better compensation when their work shows up on streaming platforms such as Netflix and Amazon Prime.

"Driven in large part by the shift to streaming, writers are finding their work devalued in every part of the business," the guild said in a bulletin to its members. "While company profits have remained high and spending on content has grown, writers are falling behind."

The strike comes at a time when there are increasing concerns about the profitability of streaming, and fears of a possible economic recession. Companies such as Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery, Amazon and Netflix have laid off thousands of employees.

Still, Alex O'Keefe, one of the writers of the Hulu series The Bear, says that the writers aren't getting a fair cut of what studios are making. "I'm really grateful to work on a show about the everyday struggle that so many Americans are living through," he told NPR. "But at the same time, I've seen that there's complete lack of care towards our working conditions. It makes it so difficult to produce the content that then makes them millions and millions of dollars."

O'Keefe says even though The Bear was a hit, "I don't get paid every time somebody watches it. I don't get paid every time somebody says, 'yes, chef.' I don't expect to make the majority of the profits or anything like that. I just added my spice. It was a whole operation to cook up that show. But we don't receive the residuals that people associate with television shows."

Britanni Nichols, who writes for the ABC show Abbott Elementary, says that between seasons, she used to be able to live off residuals she got when the network re-aired an episode she wrote. She got half her original writing fee each time. Now, when her episodes are sold to the streamers, she gets just 5.5 percent of her writing fee.

"You're getting checks for $3, $7, $10. It's not enough to put together any sort of consistent lifestyle," she told NPR. "It can really be a real shock. ... sometimes you get a stack of checks for $0.07."

Writers in Hollywood are basically gig workers with a union, constantly looking for their next job.

And TV writers say that streaming translates to less work and less money, with studios asking for series to last eight to 10 episodes a season, rather than the traditional 22 episode seasons on network TV.

Even writers on hit shows say they not living some kind of lavish Hollywood dream lifestyle; O'Keefe says he's basically broke in between gigs.

"I live a very working class existence and there's nothing to be ashamed about it," he says. "But yeah, I've reached a point that I don't know how I can continue to survive in this business as it is."

Nichols says while she's been working steadily on Abbott Elementary, her next gig isn't guaranteed.

"It could be right back to a really sort of bad situation where I'm again, struggling to pay rent. And that shouldn't be the case for someone who's going to be a decade into their careers, working for an Emmy-winning television show," she says. "I don't think anyone would look at my career and say, 'oh, that person still has to worry at this point,' but that's just where things are right now."

Other TV writers say they're now being asked to work on spec in what are called "mini rooms": They work alone on scripts that may or may not get greenlit, with no guarantee they'll get to be in the official writer's room even if the show does get picked up.

Another concern by the WGA is the use of artificial intelligence in creative content.

In anticipation of a strike, studio executives had reportedly been stockpiling scripts for months.

"We have a large base of upcoming shows and films from around the world. We could probably serve our members better than most," Ted Sarandos, co-CEO of Netflix, told investors during a recent earnings call. "We do have a pretty robust slate of releases to take us into a long time."

Sarandos said the last writer's strike, in 2007, was "devastating" for everyone, including viewers. Hollywood production shut down for 100 days, and the local economy lost an estimated $2.1 billion. The effect on viewers was felt immediately on late night TV shows and other daily productions.

Back then, writers were asking for better compensation when their work went on DVD's and internet downloads, like iTunes. This time, much of it has to do with the streamers.

READ MORE  "The report comes days after Vice shuttered its Vice News Tonight program, and amid waves of media layoffs and closures, including the end of BuzzFeed News." (photo: VICE)

"The report comes days after Vice shuttered its Vice News Tonight program, and amid waves of media layoffs and closures, including the end of BuzzFeed News." (photo: VICE)

Plan comes amid waves of media layoffs and closures, including shuttering of BuzzFeed News

The company, whose assets include Vice News, Motherboard, Refinery29 and Vice TV, has been involved in sale talks with at least five companies in a bid to avoid filing for bankruptcy, according to the New York Times.

Vice, which hit a valuation of $5.7bn in 2017 as media giants including Rupert Murdoch, WPP and Disney clamoured for a slice of its youth appeal, has been seeking a sale at a price tag of about $1.5bn.

Last week the company – which has been evaluating its future since plans to float using a special purpose acquisition vehicle (Spac) collapsed two years ago – announced it was cancelling its popular Vice News Tonight as part of a restructuring that could result in more than 100 staff being made redundant.

In February, Fortress Investment Group, the company’s debt holder, extended a $30m funding line to enable Vice to pay overdue bills to vendors. The same Nancy Dubuc, who took over as chief executive from controversial co-founder Shane Smith in 2018, announced her surprise departure.

If a sale cannot be agreed – suitors are said to be seeking a sub-$1bn deal – a bankruptcy process would see Vice continue to operate normally while an auction process is run.

“Vice Media Group has been engaged in a comprehensive evaluation of strategic alternatives and planning,” the company said in a statement. “The company, its board and stakeholders continue to be focused on finding the best pathway for the company.”

Vice, which began as a punk magazine in Montreal almost three decades ago, expanded into digital media and TV striking deals with companies including Sky and HBO.

The promise of successfully tapping the media habits of a global youth audience attracted hundreds of millions of dollars of investment from companies including Disney, which explored a $3bn-plus deal to buy Vice in 2015. Disney wrote off its $400m investment in Vice as worthless in 2019.

Vice was among a generation of fast-rising digital media upstarts such as BuzzFeed that once threatened to supplant legacy media companies with the recipe for attracting millennial audiences.

Last week, BuzzFee, which has a market value of just $75m after a disastrous initial public offering last year, announced the closure of the remainder of its once highly lauded BuzzFeed News operation and that it was cutting 180 staff across the rest of the business.

READ MORE A Kajang woman prepares vegetables for a wedding feast. (photo: Peter Yeung/WP)

A Kajang woman prepares vegetables for a wedding feast. (photo: Peter Yeung/WP)

After the spiritual leader, the Ammatoa, goes silent, groups of men wearing dark indigo sarongs jump to their feet and head into the forest carrying an offering of rattan baskets full of rice, bananas and lighted candles.

“The Earth is angry with us,” said Budi, a barefoot boy crouching on the hut’s edge. “That is why the weather is getting worse. There are more rains and floods. It is getting hotter. It is because we have sinned.”

This ritual is known as the Andingingi, held once a year by the Kajang, a tribe from the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. Like many parts of the world, their land has been hit by more extreme weather because of climate change. But as satellite imagery shows, the Kajang’s dense primary forest is free from roads and development, soaking up violent rains that devastate other parts of the island.

As global deforestation continues at alarming rates, the empowerment of Indigenous peoples such as the Kajang is emerging as a key way to protect the world’s rainforests. A spate of recent research suggests that when armed with land rights, these communities, whose members manage half the world’s land and 80 percent of its biodiversity, are remarkably effective custodians.

Meanwhile, doubts have arisen about the effectiveness of carbon offsets and other programs aimed at curbing deforestation despite the billions of dollars poured into them.

Indigenous cultures “have contributed to reduce forest destruction in various ways,” concluded a landmark U.N. review of more than 300 studies in 2021.

The Kajang offer a window into how Indigenous groups go about that work. The community lives according to the Pasang Ri Kajang, an ancestral law passed down orally through legends and tales. It tells of how the first human fell from the sky into their forest, making it the most sacred place on Earth.

In practice, that means the forest is at the center of life. The Kajang rely on subsistence agriculture, with no industry or commerce to speak of. Cutting trees, hunting animals and even pulling up grass is prohibited on most of the land. Modern technology, such as cars and mobile phones, is not allowed within the traditional territory.

“The tree is just like a human body,” said Mail, a 28-year-old Kajang who, like many Indonesians, has only one name. “If we preserve the forest, we preserve ourselves. … But if the forest is destroyed, there will be nothing for the bees, nothing for the flowers and nothing for life.”

Handing over forest control

So far, Indigenous tribes have received little legal, financial or institutional backing, advocates say. A 2021 report by the nonprofit Rainforest Foundation Norway found that over the past decade, Indigenous peoples received less than 1 percent of donor funding for fighting deforestation.

Yet policy is now beginning to shift in recognition of the role they can play in protecting the land. A global study published in the scientific journal Nature Sustainability in 2021 found that across the tropics, Indigenous lands had 20 percent less deforestation than nonprotected areas. Another analysis, from 2016 by the nonprofit World Resources Institute, shows deforestation rates inside lands controlled by Indigenous communities in Bolivia, Brazil and Colombia were two to three times lower than outside these areas.

“This is primarily because their livelihoods and worldviews are more compatible with seeing humans as living in and with nature rather than converting it to other uses,” said Anne Larson of the Center for International Forestry Research, a global nonprofit.

At the U.N. Climate Change Conference in 2021, also known as COP26, world leaders pledged $1.7 billion of funding for these communities, calling them “guardians of forests.”

Lessons on how to provide that support can be learned from Indonesia, which has thousands of ethnic groups living across its more than 350,000 square miles of tropical forest, the world’s third largest behind Brazil and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In December 2016, the Indonesian government officially recognized more than 50 square miles of rainforest as belonging to nine of the country’s tribes — including the Kajang — following a landmark ruling by the nation’s highest court. “We all know that since a long time ago Indigenous peoples have been able to manage customary forests in a sustainable manner based on existing local wisdom,” said President Joko Widodo at the time. “These values are important for us to remember in today’s modern times.”

In a case brought by the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples of the Archipelago (AMAN), an Indonesian nonprofit, the Constitutional Court ruled in 2013 that the state should transfer ownership of what are called customary forests to the Indigenous peoples who had historically governed them according to custom. Until then, all of Indonesia’s forests fell under state control.

“That was a huge victory,” said Sardi Razak, AMAN’s regional manager for South Sulawesi. “That was the first step in finally giving back the rightful ownership of these lands to the people.”

Since 2016, Indonesia’s recognized customary forests have grown to more than 580 square miles — nearly twice the size of New York City — across more than 100 tribes, according to the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. In October 2022, the government designated the first customary forests in Papua, the country’s most heavily forested area. Nearly 100 more recognitions could soon follow — taking the total to over 3,800 square miles.

Meanwhile, the rate of primary forest loss in Indonesia has declined every year since 2016, according to the most recent data available, and is now at its lowest level since at least 2002.

The recognition of customary forests, along with government efforts to protect peatlands and mangroves and to tighten regulations on logging, oil palm and mining permits, has helped drive that reduction, Razak said.

Kajang forest guardians

The Kajang are a showcase of Indonesia’s experiment. For years, local forest rangers have helped protect a wealth of native wildlife, including deer, monkeys, wild boars and tropical birds, as well as four rivers, whose watersheds supply several villages outside Kajang land.

Seen from above, the Kajang homes are dots across a vast green expanse of tropical rainforest spanning about 12 square miles.

“The Kajang forest is a dark spot on maps,” said Willem van der Muur, a land tenure specialist who carried out fieldwork with the Kajang. “It’s one of the only rainforests in that region that has been preserved. That’s thanks to the customary law.”

The group’s territory is divided into fifteen outer villages, plus an inner circle with four villages that form the tribe’s sacred territory.

The philosophy of Kamase Mase, living simply and taking no more than needed to subsist, underpins their lifestyle here. The Kajang live in stilt houses with thatched roofs and clapboard walls. They walk barefoot and wear only black or indigo clothes, emphasizing equality, humility and a connection to Earth.

“We must keep the tradition,” said Jaja Tika, a weaver who is unsure of her age but believes she is at least 70. “As long as we live, the forest will exist.”

There are even stronger controls over the Kajang’s forest, which covers 75 percent of their land. The majority of it can’t be used, save for a few exceptions such as performing rituals and harvesting timber to build a house. The Kajang’s leader, the Ammatoa, ensures that rules are followed, and violators face fines or even expulsion.

One afternoon at the Ammatoa’s house, a wooden structure on poles, a member of the Kajang was being interrogated for cutting down a tree planted by his father and attempting to sell the timber.

The man sat on bamboo floor slats in a corner of the room, flanked by a dozen of the Ammatoa’s counselors smoking tobacco.

“You tried to sell your heritage,” said the 87-year-old leader, with a flash of anger across his face.

He slapped his chest and recited a traditional verse: “Take care of the forest,” he said. “Tree leaves create rain. The roots keep water. And take care of the lungs of the earth.”

The Ammatoa then sent the offender away; his fate would be determined later.

Fending off outside threats

More serious threats to the Kajang’s forest have come from companies. Over the decades, conflicts have flared with PT London Sumatra (LONSUM), a rubber plantation firm that owns a concession overlapping some Kajang territory.

Tensions came to a head in 2003, when 1,500 protesters occupied the concession, declaring LONSUM, which has links to the Dutch colonial period, had obtained it through illegal land grabbing. Police and security forces fired at the protesters, killing four and injuring at least 20. “It was a time of great violence,” said Jumarling, a Kajang forest ranger. “Blood was shed trying to protect our lands.”

LONSUM did not respond to requests for comment.

Land disputes are common in Indonesia, home to rich mineral resources. According to a report by the Agrarian Reform Consortium, an Indonesian advocacy group, there were 212 agrarian conflicts across 34 provinces in 2022, covering about 3,800 square miles of land.

The bolstering of Indigenous land rights gives communities like the Kajang tools to fend off illegal development. The process of obtaining recognition involved hundreds of meetings between Kajang leadership, regional government staff, members of the Forestry Agency and several NGOs.

“Many didn’t know until then that their own forest was technically owned by the government,” said Andi Buyung, a Kajang member who was chairperson of the local government’s Bulukumba Regency from 2014 to 2019. “But now everyone has a better understanding, and this recognition carries extraordinary weight. If any company approaches them, they know their right to the land.”

Now, offenders can be punished under both the customary law, which includes fines of up to 12 million rupiah ($790), a huge amount of money in local terms, and district laws, which can lead to jail time. The Ammatoa relies on a group of eagle-eyed forest rangers to patrol the sacred territory and spot violations. “They’re like my smartphone,” he said.

Yet Indigenous rights advocates say the government is slow to process claims, and less than 10 percent of the potential 53,000 square miles is currently in the process of recognition.

The Kajang, who believe they possess nearly 80 square miles of land, requested recognition of around 12 square miles of forest, but received only 1.2. “It was far from our expectations,” said Hasbi Berliani, program manager for Kemitraan, a local NGO that was part of the Kajang’s negotiations.

The government has been trying to speed up the process, according to Yuli Prasetyo, an official at the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. “We are amending ministerial regulations to make it easier,” he said.

But communities must also contend with district governments, which must greenlight any customary forest. They “might be tempted to give out concessions for mining or logging to bring in money,” said van der Muur.

The next generation

Now the Kajang face another threat. Modernization, particularly in the tribe’s outer villages where the Pasang is not followed as strictly, is beginning to change how some Kajang perceive traditional rules. Younger generations, who are going to cities to study, have begun to use cellphones and wear factory-produced clothing.

But some want to follow their forebears and carry on as pioneers of Indonesia’s community-led forest management.

After graduating from college in the city of Makassar, Ramlah, the 38-year-old daughter of the Ammatoa, refused to give up her roots and returned to help lead a women’s weaving cooperative, which sells handmade sarongs at local markets.

The sarongs, worn by all Kajang, are traditionally made by spinning locally grown cotton into yarn, weaving it into cloth using a loom made from local timber, and then dyeing it with the leaves of the indigo plants they cultivate.

“The most important thing in life is the forest,” said Ramlah, sitting among a group of weavers on a sun-dappled veranda. “But modernity is important, too. Finally, the national and Indigenous laws are in unison. We have the power to strengthen us.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.