Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Trump’s 2024 orbit is loaded with DeSantis alums. Some say DeSantis made his staff’s lives miserable. They want to return the favor

These advisers, lawmakers, and operatives personally know DeSantis or used to work for him. Now, some of them are working to reelect Trump and have brought their intimate knowledge of DeSantis’ operations, and also what makes Trump’s likely 2024 primary rival tick. Just as importantly, some of the Team-DeSantis-turned-Team-Trump contingent have talked to the ex-president about how best to relentlessly mess with DeSantis, assuring Trump that the Florida governor is uniquely “insecure” and “sensitive,” and that it’s easy to get in his head, two such sources who’ve spoken to Trump tell Rolling Stone.

It’s one of the reasons why the open political warfare between Trump and DeSantis is only expected to get nastier in the coming months. “If Ron thinks the last couple months have been bumpy, he’s in for a painful ride,” says a third source, who used to be on Team DeSantis and is now in the Trump orbit.

This person continues, “The nature of the conversations among the people who used to work for Ron is just so frequently: ‘OK, how can we destroy this guy?’ It is not at all at a level that is normal for people who hold the usual grudges against horrible bosses. It’s a pure hatred that is much, much purer than that … People who were traveling with Ron everyday, who worked with him very closely over the years, to this day joke about how it was always an open question whether or not Ron knew their names … And that’s just the start of it.”

One Trump adviser who also knows DeSantis tells Rolling Stone, “Oh, I’ve told the [former] president several times how easy it is to mindfuck Ron,” adding they’ve told Trump that “[DeSantis] takes little slights and digs incredibly personally and doesn’t really let things go. [Trump] is aware that the Florida governor is tailor-made for him to effectively mess with, until Ron backs down.” Ironically, the title of the prominent pro-DeSantis super PAC is Never Back Down.

Though Trump seems eager to take advantage of DeSantis’ allegedly razor-thin skin, the ex-president and 2024 GOP frontrunner is similarly famous for his own hypersensitivity and penchant for obsessing over jabs from others. He spent time as president trying to convince his own female senior staffer that his penis wasn’t bizarrely shaped, as was alleged at the time. During his 2016 presidential campaign, he couldn’t help himself from feuding with a Gold Star family, simply because they criticized him. He kept feuding with John McCain even after the senator died. While he was leader of the free world, Trump secretly pressed lawyers and political aides on whether his government and Justice Department could investigate Saturday Night Live and other late-night comedy shows for being too mean to him. He directed his own White House staff to lean on Disney to censor late-night host Jimmy Kimmel, an anti-Trump comedian. And the ex-president was, of course, so keen on not letting go of the anti-democratic fiction that the 2020 election had been stolen from him that it caused a deadly riot.

Furthermore, Trump, similar to DeSantis, has his own lengthy running list of former loyalists and officials who’ve since become some of his most bitter enemies.

But no matter for Team Trump, which sees DeSantis’ own insecurities as a massive opportunity.

“Ron is not someone who can just ‘walk it off.’ I know because I made a lighthearted joke to him once, and he got mad and held it against me,” the Trump adviser adds. “Team Trump does not want to just beat him. Team Trump wants to humiliate him maybe more than they’ve ever wanted to humiliate anybody on a national stage … [and] that is what is driving a lot of this.”

DeSantis’ spokesperson did not respond to Rolling Stone’s request for comment on this story.

In recent months, Trump has spoken to an array of advisers, friends, and Republican lawmakers who’ve known or worked closely with DeSantis, and has at times solicited gossip and salacious, unverified details of the governor’s personal life. On top of that, the former president has brainstormed with several of these confidants various ideas for aggressive mudslinging messaging. According to two other sources with direct knowledge of the matter, among the potential targets they see are DeSantis’ physique, attire, appearance, voice, and social skills. They also believe he looks humorously clumsy in his ongoing feud with Disney.

Sometimes, Trump has privately noted that some of these elements would work well if incorporated somehow into eventual 2024 attack ads against DeSantis.

“Donald Trump is an animal. He’s a fighter. In 2016, he went further than what a so-called respectable politician was supposed to do, in how aggressive his attacks against opponents were. It offended some people, but now, he’s pushed the boundary of propriety so far that others are willing to go there in campaigning,” Michael Caputo, a former Trump administration official who remains close to the ex-president, tells Rolling Stone. He adds that some Trump allies are interested in perhaps even harsher attacks than Trump is. “There are people — including at the peripheries of the 2024 campaign — who go after DeSantis even harder, and get even rougher on the governor’s allies,” Caputo says.

Indeed, Trump has already demonstrated that virtually nothing is off limits in his campaign against DeSantis, who hasn’t even officially declared his 2024 candidacy yet. (The governor is clearly running a “shadow campaign” at this time, however.) Last month, the ex-president publicly suggested DeSantis might be gay. The month before that, Trump implied the Florida governor is a pedophile. That the allegations are baseless is not much of a concern to the 2024 Republican frontrunner.

“The only people who like Ron DeSantis are the people who have never met him,” Taylor Budowich, the head of the pro-Trump super PAC MAGA Inc. and Trump’s former spokesman, harshly commented to NBC News last week. Budowich, too, is a DeSantis alum, having worked with the DeSantis transition in Florida.

Stories of DeSantis colleagues and staffers describing the Florida governor as either cold or hostile are legion. Republican political operatives have slammed him as a man who is “missing the sociability gene” and “never says thank you,” even to major donors.

In a blistering 2021 piece, Politico reported on the existence of a so-called “support group” of “scarred” former DeSantis aides who meet to exchange stories on what they described as a nightmare boss that treated anyone not in his innermost circle “like a disposable piece of garbage.”

The irritation with DeSantis is evident in some of the embarrassing stories former staff have floated to the press. Former employees told The Daily Beast of the pudding incident, which reportedly involved the Florida governor shoveling the chocolate dessert into his mouth with three fingers to the disgust and amazement of those accompanying him on a flight to Washington, D.C. The detail went viral and provided the grist for a Trump-aligned super PAC ad riffing on the pudding incident and attacking DeSantis over Social Security policy.

The DeSantis campaign-in-waiting has been rocked by a series of rebukes from donors to members of the state’s Republican congressional delegation.

Over the past two weeks, members of Florida’s Republican congressional delegation have announced their support for Trump one by one and the steady drip-drip of endorsements hasn’t been accidental. As Rolling Stone reported, the slow rollout — planned to inflict maximum humiliation of DeSantis — was helmed in part by Susie Wiles, a former DeSantis aide whom the Florida governor blackballed from his political operation after she helped him win the 2018 governor’s race. According to people with knowledge of the matter, though, Wiles is more restrained, and less colorful, than other Trump acolytes in privately describing her bad experiences with DeSantis.

Rep. Greg Steube, who endured a dangerous fall and lengthy subsequent hospital stay, announced his support for Trump last week. In an interview with Politico, the Florida Republican said DeSantis had repeatedly snubbed or ignored him, including during his hospital stay, in contrast to what he described as a more solicitous and attentive Trump. On Friday, Steube went a step further and blasted DeSantis supporters in the state legislature for “carrying the water for an unannounced presidential campaign” and urged them “not to kowtow to the presidential ambitions of a Governor.”

Other former DeSantis associates have made their intentions toward DeSantisland abundantly clear.

Justin Caporale is a former Trump White House aide who went to work for the DeSantis administration only to return to the MAGA fold as Trump’s top advance man. According to RealClearPolitics, Caporale has already informed DeSantis aides that working on the Florida governor’s recent book tour would blackball them from a future in the Trump presidential campaign or any future Trump White House.

READ MORE  Iran's national flag flutters in the wind as the Milad telecommunications tower and buildings are seen in the background, Tehran, Iran, March 31, 2020. (photo: AP)

Iran's national flag flutters in the wind as the Milad telecommunications tower and buildings are seen in the background, Tehran, Iran, March 31, 2020. (photo: AP)

Videos show security forces using lethal force at mourning events

The Washington Post analyzed 18 cases of state violence at mourning events — focusing on three where security forces used fatal force — interviewing eyewitnesses and human rights observers and reviewing dozens of videos and images.

Many of the cases were from the predominantly Kurdish northwest, fitting a pattern of disproportionate use of state force against ethnic minorities. Visual evidence shows national police units and Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps using live fire and less-lethal weapons on mourners.

In the Iranian Shiite funerary tradition, there is the burial itself, followed by memorial gatherings on the third and seventh days after the death, followed by a third, a “chehellom,” on the 40th day. Many of those killed have been elevated as martyrs by the protest movement, with each public display of mourning inspiring new rounds of demonstrations — and new repression by the state.

One of the uprising’s earliest viral images was from the funeral of Javad Heydari, who was killed on Sept. 22 in the northern city of Qazvin during an anti-government demonstration. Videos showed his sister cutting her hair over Javad’s casket — a sharp departure from the past, when families of those killed by the state would bury their loved ones in private, pressured by authorities to keep quiet.

[Videos show evidence of escalating crackdown on Iranian protests]

Iran’s clerical rulers understand the power, and danger, of public grief. In July 1978, religious leaders organized large protests around the death of a popular opposition figure. Crowds marching in funeral processions in Mashhad chanted slogans against the ruling Pahlavi monarchy. Riot police reportedly fired into the crowds, killing around 40 people. Seven months later, the Islamic revolution would overthrow the shah.

Iranian security forces have killed at least 530 protesters since September, according to the U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency, and protests have been more sporadic in recent weeks. On March 21, Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, struck a triumphal tone, saying the government had put down the unrest. “The Islamic republic proved that it is strong,” he said.

“They want to scare the population, and they want to convey the message that ‘we won’t let you rest even if you’re dead,’” said Shahin Milani, the executive director of the Connecticut-based Iran Human Rights Documentation Center, which has worked to verify state attacks on mourning events.

A spokesman for Iran’s mission to the United Nations in New York did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Death at a chehellom

Hadis Najafi was killed Sept. 21 during an anti-government protest in Karaj, a large city near Tehran. Najafi’s death received widespread attention because she was close in age to Mahsa Amini — the 22-year-old whose death in the custody of Iran’s “morality police” sparked the uprising — and had a large following on Instagram and TikTok.

Forty days after her death, on Nov. 3, thousands of people headed to the Beheshte Sakineh cemetery on the outskirts of Karaj for Najafi’s chehellom. Government forces blocked the highway exit that leads to the cemetery, according to eyewitnesses. Videos show mourners walking along the highway, trying to make their way in.

Unable to reach the gravesite, mourners spread out across the city. Farther south, hundreds marched along Beheshti Boulevard, on the northern edge of the Khorramdasht neighborhood. There, a video verified by The Post shows the moment that 17-year-old Mehdi Hazrati was shot and killed.

In the video, protesters are seen throwing rocks toward the security forces, some of which are clad in black body armor. Mark Pyruz, an expert on Iran’s security services, identified the officers wearing black body armor as riot police — a unit under the national police force, or FARAJA. As Hazrati walks toward the police, a gunshot rings out. His body slumps to the ground.

“The gunshot sounds like a clear muzzle blast,” said Steven Beck, a forensic gunshot analyst who reviewed the video for The Post, suggesting it came from a smaller firearm. “It is not a big gun like a sniper rifle,” he added.

“The shooter, without hesitation or making a mistake, took aim at close range and aimed exactly at the head and shot [Hazrati],” according to a Karaj resident whose mother recorded the video, which later made its way to activists. Too afraid to speak to journalists, the woman shared her account with her son, who spoke to The Post on her behalf.

The Iranians interviewed for this story spoke on the condition of anonymity, fearing reprisals from the authorities.

In the chaos that followed, the government said protesters assaulted a member of the Basij, a volunteer paramilitary under the command of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, or IRGC, the country’s most feared military force. Fifteen people were arrested, and five of them were sentenced to death in what Amnesty International described as “sham trials.” Mohammad Mehdi Karami, 22, and Seyyed Mohammad Hosseini, 39, were hanged on Jan. 7; the death sentences for the other three men are under review by the judiciary.

In mid-December, mourners gathered again at Beheshte Sakineh cemetery, this time for Hazrati’s chehellom, according to a video posted to Telegram by the Iranian citizen journalist account Mamlekate. In the video, a family member claims that Hazrati’s parents were put under house arrest, preventing them from visiting his grave.

‘More and more ruthless’

On Dec. 31 in Javanrud, a Kurdish city in western Kermanshah province, a crowd of hundreds gathered for a chehellom for seven protesters killed by security forces. But as mourners reached the Haji Ibrahim Cemetery, they were met by a large contingent of government forces.

“A policeman from the special police forces used a speaker attached to one of their vehicles to tell people to go home,” a 29-year-old Javanrud resident told The Post. “He said, ‘This is a holy place. Don’t let there be any blood spilled here.’ In a way he was making both a request and a threat.”

One video from the cemetery shows more than 20 officers in dark uniforms and body armor. The Post showed these videos to Pyruz, who identified forces from the FARAJA’s Special Unit, as well as from the IRGC’s Ansar al-Rasoul Brigade and what appear to be plainclothes operatives.

“[The security forces] were clearly outnumbered by multiples,” Pyruz said. “This is typically where one observes the application of lethal force — when police or IRGC/Basij are at an overwhelming numerical disadvantage in confronting a resisting force of protesters.”

Afshon Ostovar, an associate professor at the Naval Postgraduate School in California who focuses on Iranian national security, also analyzed the videos. “When the military gets involved, it means that the protests have become a national security concern,” he said, referring to the deployment of the IRGC. “Typically, that means the military is authorized to use greater degrees of violence than the police, including lethal violence to put down the protests.”

When riot police failed to contain the crowd, IRGC forces opened fire, eyewitnesses said. “The Revolutionary Guard started to shoot at us. People didn’t even make a single move. We were just standing in the same place and were chanting protest slogans,” said another Javanrud resident who was there that day.

Borhan Elyasi, 22, was killed during the crackdown, according to Hengaw, a Kurdish human rights group. Hengaw shared graphic footage online claiming to show Elyasi bloody on a hospital stretcher, and his death was confirmed to The Post by locals.

“People rushed him to the hospital, but he didn’t survive,” said a staff attorney for the Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (IHRDC) who has documented the incident in Javanrud and dozens of others like it at mourning events across the Kurdish region. “The Iranian government has become more and more ruthless and shameless in using live ammunition in the light of the day.”

“It is unknown why they started shooting at people, because I have seen it in different videos from different angles that they could have stopped people from entering the cemetery,” the attorney added, pointing to video posted by Hengaw that shows mourners fleeing the area amid clouds of tear gas.

‘They martyred poor Borhan’

On Nov. 15, Foad Mohammadi was killed in a protest in Kamyaran, in Kurdistan Province in the west of the country, near the border with Iraq. The following day, people gathered outside Mohammadi’s family’s home in Kamyaran to pay their respects and to express outrage at his killing.

“We saw that we were surrounded by security forces in uniforms, civilian clothing. Basijis [members of the IRGC’s volunteer wing], intelligence agents, they were all over the area. People were chanting protest slogans like ‘Women, life, freedom’ and ‘Martyrs don’t die,’” a Kamyaran resident told The Post.

A video filmed outside Mohammadi’s parent’s house and verified by The Post captures the moment that a 32-year-old named Borhan Karami is shot and killed. There are at least four audible gunshots in the footage; Karami collapses after the third shot. Before Karami is hit, he appears to point in the direction of the gunfire.

It is unclear from the video who fired the fatal shot, but the Kamyaran resident said he saw anti-riot forces open fire. “Maybe about five or 10 meters away from me, I saw that all of a sudden, a young person fell to the ground. He hit the asphalt with his head. People ran away,” the eyewitness recounted. “We ran over and saw that the shooters were still standing right there on the street. They martyred poor Borhan.”

The chief justice of Kurdistan Province, speaking to a local news site, confirmed that Karami was fatally shot in the head but stated that “no officer was present when this person was shot.”

“The government showed no interest in doing investigation in this case,” said the IHRDC staff attorney, who has also reviewed Karami’s case. “No person has been held accountable for his murder.”

Hengaw shared a video online that purports to show a gathering of mourners at Karami’s nighttime burial on Nov. 16. “Mother, don’t mourn for your child, we promise to avenge him,” the crowd chants, before reverting to the protest movement’s defining slogan: “Death to Khamenei.”

READ MORE  Indian boarding school survivor Matthew Warbonnet poses with ceremonial feathers in his backyard in Snohomish County, Washington. (photo: Rolling Stone)

Indian boarding school survivor Matthew Warbonnet poses with ceremonial feathers in his backyard in Snohomish County, Washington. (photo: Rolling Stone)

In 1819, the federal government instituted a program of state-sponsored abductions and forced assimilation of Native American children. It lasted 150 years and spawned a legacy of horrific abuse. Now, survivors and their descendants are speaking out

“You know,” he says, haltingly, “I can’t remember anything before the mission school. But I remember too much about the mission school.”

Warbonnet, Sicangu Lakota, first shared his experiences at St. Francis before Congress in May 2022, one of numerous survivors of the country’s Native American boarding schools — a federal program of forced assimilation that stretched from 1819 to 1969 at more than 400 educational institutions nationwide — who testified to horrific abuses they suffered there. The testimony took a lot out of him, he says, due to a resurgence of emotional and psychological pain.

One of Warbonnet’s earliest memories was the anguish of being separated from his family at just six years old. He’d been excited to go to school for the first time when his parents dropped him off at St. Francis in September of 1952. But that changed when he realized he wasn’t going back home.

“That night, of course, I started missing my parents,” he says. “You get lonely. Some of us would be crying.” There was a priest monitoring the children in what Warbonnet describes as a cubicle in the middle of the room. If the boys continued to cry, he says, the priest beat them. “He’d come out of that room and he’d pull the first kid out of his bed and start slapping him. Well, that taught me to choke things down, you know? I was just scared.”

Though his sisters were at the school in the girls’ dormitory, he wasn’t allowed to speak to them. He was only permitted to see his parents on holidays and summer break. The boys were made to do physical labor and regimented chores while learning the language of the white man. Seven days a week, they were forced to attend Catholic mass. They were told they were rotten for being born Indians. Physical abuse continued for years.

Across his kitchen table, Warbonnet lays out instruments similar to those that were used on him for punishment at the school: a thick leather belt with metal grooves, a willow stick, and a braided rope the children named “the Jesus rope.” Warbonnet made the replicas when he began sharing his story, to help people visualize the brutality to which the children were subjected. Whippings were so severe, Warbonnet explains, that it was standard to be sent to the infirmary to recuperate, sometimes for hours, or even days. He came to refer to the razor strap as his friend, because, he says, “it taught me not to feel when they were hitting me.” Priests would even use cattle prongs to electrocute the children. Warbonnet didn’t know what the tool was at the time, only that it burned his flesh and left marks that are still visible on his backside.

Warbonnet says there aren’t many St. Francis survivors who are still alive. Some of his classmates died from addictions, others by suicide. His body trembles and he begins to sob as he recalls his attempt to take his own life during a summer break after completing the eighth grade. His father found him hanging from a rope attached to a tripod used to pull motors out of vehicles that his father used to work on.

“I was ashamed of who I was,” he says, “because I didn’t know who I was.”

WARBONNET’S STORY IS one of countless tales from Indian boarding school survivors and their descendents that have emerged amid a wave of reckoning around the colonial, systematic efforts of the United States government and churches to eradicate Native communities. Hundreds of thousands of Native American children were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to these schools under the Indian Civilization Act Fund of 1819 and the Peace Policy of 1869 which adopted the mandatory Indian Boarding School Policy. The motto of that policy — “Kill the Indian, save the man” — is a quote by Richard Henry Pratt, a Union Army brigadier general who is considered the father of the movement to integrate Native children into white American society. Pratt established the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania in 1879, which became the model for other Indian boarding schools across the country.

As a part of this program, Native children as young as three were stolen out of the arms of their parents. For years, Warbonnet harbored intense anger toward his parents for leaving him at St. Francis, until he came to learn that they’d had no choice. “This was a question that really bothered myself and a lot of the kids,” he says. “We hated our parents for sending us. We didn’t understand why that was. So when we grew up later, we found out that there was a law at that time which was being used against Indian parents. If they didn’t send their kids to school, they would be put in jail.”

Warbonnet’s parents had attended St. Francis themselves, although they didn’t talk about it with their children. Warbonnet suspects it was too traumatic for them. But his father carried his own permanent scars: In second grade, he ran away from the school in the dead of winter and froze all of his toes off. “My dad used to joke with us that he went into the military and didn’t have toes because he got captured and they tortured him,” Warbonnet says. “He said the enemy cut off a toe every day until all his toes were cut off and then he was rescued.”

Warbonnet learned the truth from his cousin as a teenager. He then confronted his father, who told him the real story. His father died at age 62 from a gangrene infection in his feet.

“In the end, that’s what killed him,” Warbonnet says, his voice breaking. He adds, “I can understand why he didn’t tell me the truth. Because one thing I never wanted to do was hurt my kids. I didn’t want them to be hurt when they learned what happened to me at that place.”

Some Native children were taken thousands of miles away from their families, and in many cases never made it back home. They were doused in kerosene to ward off infection or lice, their hair — which is sacred for many tribes and cut only during periods of mourning — cut short. Banned from speaking their language, their Indian names stripped and replaced with European ones. Placed in barrack-style housing, given numbers as identification, made to wear uniforms. They performed manual labor and suffered malnutrition. Physical, verbal, sexual, emotional, spiritual, and cultural abuse were rampant.

“The U.S. has some internal searching inside that we have to do as a collective,” says Deborah Parker. The CEO of the Native American Indian Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) — a network of Native academics, researchers, tribal leaders, boarding school survivors and their descendants working to establish a Congressional Truth Commission — Parker, 52, is at the helm of the efforts to expose the damages inflicted by the insidious 150-year program.

The purpose of the commission, Parker explains, would be to thoroughly investigate the losses that occurred through this violent genocide. To date, there has never been a full accounting of the number of children forced to attend these schools in the United States (between 2007 and 2015, there was a $72 million investigation into similar schools in Canada), or the number of children who were abused, died, or went missing from them. The commission would also examine the long-term impacts on the children and their families and hold subpoena power over churches, organizations, and the federal government to hand over records from the former boarding schools. Parker helped write the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act, which was originally introduced in Congress in September 2021 and she hopes could pass by the end of this year.

“Once the bill is introduced [during this session] then we really have to hit Washington, D.C.,” Parker says. “We need tribal leaders. We need a lot of folks to really help push this bill. Then those records will need to come forward and be examined by the commission, who will draft their recommendations to the Senate and House and to the President. From there, we will see what’s recommended for the U.S. to be holding themselves accountable.”

A driving force behind that push is Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland. The first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, Haaland launched the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative in June 2021, which comprises both an extensive investigation by the Department of the Interior into such schools and a “Road to Healing” tour, a series of public hearings where she and other government officials listen to survivors and families recount their stories.

The first report issued as part of the investigation was released in May 2022. It documented 408 federal Indian boarding schools that operated across 37 states or then territories, including 21 schools in Alaska and seven schools in Hawaii. Marked and unmarked burial sites of children who didn’t make it out alive were found at approximately 53 different schools. The department expects the number of identified burial sites to rise.

“The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies — including the intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication inflicted upon generations of children — are heartbreaking and undeniable,” Haaland said in a press release that accompanied the report. “We continue to see the evidence of this attempt to forcibly assimilate Indigenous people in the disparities that communities face. It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous peoples can continue to grow and heal.”

As for the tour, Haaland will have visited a total of eight tribal communities throughout the United States upon its completion this fall, from Oklahoma to Hawaii, Michigan, Arizona, South Dakota, and more. The testimonies she’s gathered will be used to create a permanent oral history and to create recommendations on mental health support and healing initiatives.

NABS representatives have attended every “Road to Healing” tour stop, and on April 23 Parker will welcome its arrival on her home turf, the Tulalip reservation, which rests on the Puget Sound about 40 miles northwest of Seattle. The load of the responsibility and corresponding generational heartache she carries is heavy, she says.

“I can’t think of anything more evil than the taking of and abusing children,” Parker says, her voice cracking with emotion. “Some want to believe that this didn’t happen, because they’ve lived their lives off the back of people who have suffered great harm in this country — and in this case children, Native American children and their families. I see poverty on reservations. I see depression. I see sadness and grief, loss of life. And few people understand what that means and why — that thousands of our people were murdered [through colonization]. Children were taken from their mothers and grandmothers. Fathers, uncles; they were brutally taken.”

Parker can speak to this devastating legacy personally. Her own family did not escape the horrors of the Indian boarding school era.

ON A FOGGY MARCH AFTERNOON, Parker sits in a small room adjacent to what once was the dining hall at the Tulalip Indian Boarding School, recounting her great-great-grandmother’s story of being taken to these grounds at the start of each school year. She describes a time when she crouched with the elder matriarch, Hariette Shelton-Dover, under the family’s kitchen table, following orders to stay as still as possible and not breathe a word. Parker thought it was a game, until Shelton-Dover explained that they were re-enacting how would hide in hopes she wouldn’t be taken from her family. But each time she crouched under the table before the start of another school year, she’d be found. It was the police who would arrive to tear her out of her parents’ arms forcing her to go to the Tulalip school.

“These children couldn’t get out of these places, it was a prison for them,” declares Parker, looking around the room. We are in one of the last remaining buildings of the sprawling former school grounds.

Parker recalls her grandmother sharing about her long, lonely years here, where she attended from age five until her late teenage years. How she tip-toed around school staff in fear of punishment for being caught speaking her Snohomish Lushootseed language. Half of her school days were spent learning American academics, the other half performing tedious manual labor such as mopping floors, washing dishes for over 200 children, and working in the dreaded laundry room operating an industrial-sized ironing machine that Shelton-Dover witnessed other students’ hands be mangled in. Flashbacks of constant hunger pangs due to inadequate meals permeated her adult life as she worked to overcome the effects of physical, verbal, and emotional abuse.

In her 1991 autobiography, Tulalip, From My Heart, Shelton-Dover recalled a nun hitting her with a strap made out of a horse and buggy harness, which cut her skin and made it bleed: “The straps wrapped around my whole body. She was a tall woman, big and strong. She swung her arms way out, and she made that strap swing around my neck and she nearly knocked me out. She could hardly breathe, she was so mad. I went sailing across the hall and my head crashed into the wall.”

Shelton-Drover grew up to become a wife, mother, and grandmother, a college graduate, and tribal chairwoman. She reestablished the once federally banned First Salmon Ceremony, done annually in August to honor the return of the first king salmon of the season at the Longhouse near Tulalip Bay — the ancient spiritual center of the Tulalip. (Salmon are a staple diet for the tribe and the ceremony of feasting, singing traditional songs, and recounting the story of an alliance between the fish, the Tulalip, and many other bands in the Puget Sound area is widely celebrated.) She lived a rich life to the age of 86. But her time at the Tulalip boarding school still reverberates through her family.

Today, it’s empty inside the colonial-style building of the old school. Its wooden floors are polished to a shine, the industrial kitchen has been updated with modern appliances and plumbing in the near century since its closing. From time to time, the space is used to host community events. Still, echoes of crying children can be heard here, says Parker. Her long, chestnut colored hair softly frames her face as she scans the room. She squeezes her almond shaped brown eyes shut and winces.

“The kids were marched everywhere. This was a concentration camp,” she says. She pauses to gaze out a paneled window toward the picturesque ocean bay, whose surrounding lands her ancestors have inhabited for time immemorial.

The Tulalip (meaning “small-mouthed bay”) reservation has a population of 2,700. Encompassing 22,600 acres along the coast, it’s the traditional territory of the Duwamish, Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Skagit, Suiattle, Samish, and Stillaguamish people. Tulalip’s borders are framed by giant evergreen forests, the city of Marysville to the east and the towering Olympic and Cascade mountains. The tribe’s crest of an orca whale is carved into public buildings and traditional artworks like paintings, cedar carved paddles, masks, and large sculptures depict ancient legends throughout the Tulalip community.

The boarding school, which operated from 1857 to 1932, served as a hub for thousands of Native children who were shipped in from neighboring reservations. Yet, hardly anyone speaks about what happened here.

“It’s been such a deafening silence,” Parker says. “The schools did a really good job of making sure our kids almost never talked again.”

FINALLY, THANKS TO HAALAND’S “Road to Healing” tour and the work for organizations like NABS, that is changing. The last Indian boarding school in America closed in 1978, when Native American parents gained the legal right to deny their children’s placement in boarding schools via the Indian Child Welfare Act. But the distressing testimonies of survivors live on through the generations. Parker has taken in hundreds of accounts from boarding school survivors across America and describes them as “unimaginable — beatings, strangulation, and being chained to radiators. I mean, just being taken from your family alone is traumatic.”

There are recurring themes from survivors that Parker struggles to comprehend.

“Another one of the things we’ve heard throughout the country are stories about incinerators. Stories of young girls having babies from priests after being raped, and then we’ve heard that these babies had to be disposed of right away. There are just repeated stories about the smell of burning flesh. Every time we hear it…it’s just sickening.”

There are 31 unidentified graves on the southern half of the Mission Beach cemetery in Tulalip. The first boarding school campus was located not far below the cemetery, on the southern bank of Tulalip Bay, before it burned down in 1902. It was later moved to its current location. Parker, local historians, and the tribal chairwoman believe some of the nameless graves could belong to children who died under unknown circumstances at the school. Parker also thinks there could be bodies that have never been found.

“There’s a burial mound possibly under the old school grounds,” Parker tells Tulalip Chairwoman Teri Gobin in Gobin’s office, as the two discuss potential strategies to begin the painstaking process of identifying lost children.

“OK, yes, we will search the school grounds,” Gobin says, reaching for a file folder on her desk. She presents us with copies of a letter dated Oct. 29, 1889. The letter is written by the former Tulalip Indian agent and Catholic missionary Eugene Casimir Chirouse.

Chirouse wrote to the then Secretary of the Interior, Columbus Delano, outlining the contents of “objects” he collected from Tulalip “without cost.” One item he lists is the skull of a young Tulalip girl. “The small skull is that of […] a child of 5 or 6 years of age,” he wrote. “Her parents are still living and they do not know that the skull of their child has gone to Washington.”

The letter surfaced only recently. Gobin’s late father, Stanley Jones Sr., was an avid researcher and had discovered it amongst the records in the National Museum in Washington, D.C. Both Parker and Gobin are furious that the child’s remains were taken. Even though over 100 years have passed, they’re determined to find out where the child’s skull is and bring her home to be laid to rest.

“I don’t think that the public is ready to admit what their ancestors did,” says Gobin. A traditional woven cedar headband rests atop her caramel-streaked hair. She sits stoically glancing at a view of thick forest being quenched by falling rain outside her office window.

“You know, most people in the U.S. have no idea about the damage that was done,” says Gobin, drawing in a deep breath and leaning back into her chair. Her grandfather attended the Tulalip boarding school and her father was shipped to the Chemawa Indian School in Oregon. Barely any family in Indian country was left untouched by this legacy of trauma. “It’s about time. Our history has been hidden — the attempted genocide of our people. We have been resilient and survived through it, but they’ve taken away so much. There’s still a lot of healing that needs to happen.”

The crumbling, graffiti-covered remnants of a concrete federal prison built to jail any Indians who stepped out of line, or who were caught practicing traditional ceremonies or speaking their language, remain on the rocky banks of Tulalip Bay. It’s located approximately 10 yards south of the former Indian boarding school. And sometimes children were sent there, including Tulalip tribal member Chelsea Craig’s great-grandmother, Cecilia Young, in 1900.

“They pulled her out of bed in the middle of the night,” says Craig. Just five years old at the time, her grandmother had been caught speaking a word in her Lushootseed language, and a concrete cell was her penalty. Craig says her grandmother became terrified when water from the rising tide started flooding into the cell. “She was in that jail cell for three days and three nights just for saying one word. And she had to float because of the water in there. Grandma said she didn’t think she was gonna make it.”

Young spent the next 14 years at the school, experiencing physical and sexual abuse, according to Craig. Despite going on to become a celebrated matriarch living to the age of 91, she never completely shook the afflictions of Indian boarding school.

Still, Craig believes her grandmother returned to her own when she died. With tears in her eyes, Craig describes being at Young’s deathbed, her grandmother’s hands hanging over the sides of her hospital bed during her last breaths. “She says, ‘Oh, I’m just touching the water. I’m in a canoe.’” Young would come to pick her up in the summers in a canoe and bring her out to traditional territories. Once they got far enough away from the boarding school, they would go through a ceremony of bathing, dipping in the Salish Sea to wash off all that sickness that she was living with. “And so, I know now, she’s whole,” Craig says.

Craig named her first daughter after her late grandmother’s Indian name, Celum — the name Young proudly carried until it was stripped from her and replaced with the English name Cecelia. Now, Craig is working to undo the harms of Indian boarding school for children of this generation. She is the assistant principal of Quil Ceda Tulalip Elementary, the first tribal person to hold the position. For eight minutes every morning, she hosts an assembly where the children gather to sing and drum a Tulalip song, dance, and conduct a sharing session in the form of the ancestral Longhouse tradition. Craig is also developing programming around the medicine wheel, holistic teachings, and “decolonizing the classroom” experience.

“They might not be sexually assaulting kids and beating them [at schools today], but the boarding school mentality still exists,” she says, such as expecting children to conform, using control, silence, or erasure of who they are to become “educational soldiers.” She continues, “Everything that you see here, everything that the air touches in school, is a colonized space. Everything needs to be reimagined.”

To that end, the Quil Ceda school has “pod” groups — modeled after clans or pods of Orca whales — where children can be connected to each other and be paired with a counselor if needed. “So, the idea is, we’re a collective in a family,” Craig explains. “And we have this room where, if kids were having a hard time, they’d be sent there to get comfort.”

Craig believes the children are the walking prayers of their ancestors, and it’s her job to carry out the healing process in her grandmother’s memory. “I think that she would laugh and just be amazed that we’re able to be ourselves. Even just to see our language in this space, I know she’d be happy.”

AS MATTHEW WARBONNET prepares to once again testify at the upcoming “Road to Healing” tour, he admits he’s struggling to cope. He’s experiencing nightmares, flashbacks, and bouts of crying. He worries the public process of truth-telling might be “opening a can of worms” for other survivors who may not be able to handle the anguish. Warbonnet insists he isn’t speaking out for his own healing, because it doesn’t help him. He’s speaking out because he wants the truth to be known and for the perpetrators to be held to account.

“I’m more depressed now than I’ve been in years,” he says. “I sat that night [before I testified to Congress] and cried. My wife knows when I’m quiet, she knows there’s something wrong.”

Earlier, Warbonnet had told me there was “a lot of rage” inside him when he was a boy. He was able to quell it, he’d said, with the help of his Lakota parents: “I talked to my dad about these things when I was at school and he gave me a song. And he says, ‘Only you have the power to decide how you’re going to live today. No one else. You can live it being angry and mean or you can live in appreciation for what the Creator has given you.’ So every day at that school, in my mind, in my heart, I would sing that song [he gave me]. And I never allowed those sons of bitches to decide how I was going to live.”

As an adult, he vowed not to use drugs or drink alcohol, because he saw what it did to many of his former classmates. “Because that rage was in me,” he’d explained, “and I knew it didn’t take much for it to come out. [My siblings and I] did not become abusers of ourselves, of our families, of our communities. Dad set a good example for us.”

But it’s clear some of that rage still lives inside him. As talk turns to the Catholic church, it peeks out.

When Pope Francis apologized to Indian Residential School survivors in Canada at the Vatican in the spring of 2022, and then to survivors during his “penitential pilgrimage” that July, Warbonnet says it seemed more like a smoke-and-mirrors foray. He’s not sure an apology from the Pope or other authorities would be of any benefit in the United States.

“What the hell are they gonna do?” he shouts. Suddenly, his demeanor shifts and his hands wave in front of him as he denounces the atonement. “Take a look at all these damn communities. What the fuck are they going to do? They can’t be sorry. Are they sorry that the communities are like that? That our children are committing suicide? What the hell are they sorry for? I’m sorry they’re not in there, helping.”

Tears stream through the grooves of wrinkles on his face as he heaves to catch his breath. He says he wants repatriation in the form of financial resources and federal reserve land returned to Native communities, which are key in helping to restore culture and identity: “Do they have a program that carries out to the future? Some say ‘Oh, we have to give these people money for something that happened a hundred years ago’, blah, blah, blah. I say to them, ‘Restore to us those federal lands that are not being occupied right now and go back to the children and grandchildren and take responsibility for what they did to those kids.’”

Later, on the grounds of the former Tulalip Indian boarding school, Parker is saying a prayer. She’s overlooking the ocean while standing on the manicured back lawn. Softly gripping her ceremonial rattle in her right hand, she sings a traditional Tulalip song, belting out the language that the boarding school attempted to eradicate. Her lips tremble and an outpouring of grief wets her eyes as she proclaims the silence is broken.

“You can’t do this amount of harm to a people and to the earth and think that nothing is going to take place, because it will,” she says, adding that she is unwavering in her quest to secure justice for survivors, no matter how long it may take.

“There’s a memory in our pathways, there’s a memory on this earth, and that can’t be erased. And we must work to heal. We have to look at the atrocities of the past. Healing looks like each person who went through the boarding school system, or who had a family member who went through the boarding school system, that they have a voice and they have knowledge that’s needed for them to understand what happened. And for boarding school survivors to feel that they’re finally free to come out of the darkness.”

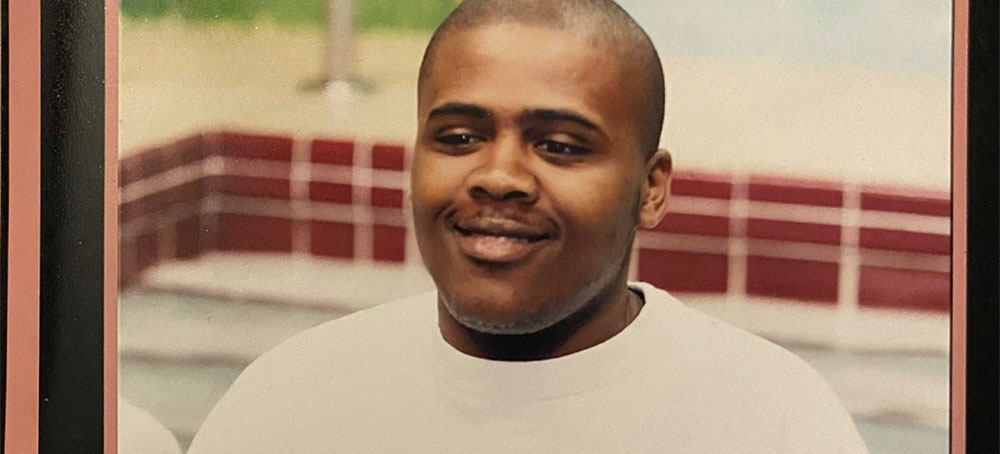

READ MORE  Lashawn Thompson, 35, died in the Fulton County Jail in Atlanta in September 2022. His family's attorney, Michael Harper, said Thompson's body was covered with insect bite marks. (photo: Michael Harper/NPR)

Lashawn Thompson, 35, died in the Fulton County Jail in Atlanta in September 2022. His family's attorney, Michael Harper, said Thompson's body was covered with insect bite marks. (photo: Michael Harper/NPR)

Kaepernick personally reached out to Thompson's family to offer his support, Crump said Thursday.

"We want to thank Colin Kaepernick for helping this family get to the truth and soon," Crump said at a news conference outside the Fulton County Jail in Atlanta, where Thompson had died. Kaepernick did not attend the news conference.

Thompson, 35, was found dead in September 2022 after being held at the jail's psychiatric wing for about three months. At the time, the Fulton County Medical Examiner's Office ruled that the cause of his death was "undetermined," but his family says the jail's deplorable conditions played a role.

Not only was Thompson's cell filthy, but his body was covered in insect bites, including on his ears, mouth and nose, Crump said in a statement.

"It is completely unacceptable to force inmates to live in appalling conditions where they are subjected to insects, grime, and infections," Crump said. "No one should be treated that way."

Attorney Michael Harper, who is also representing Thompson's family, said the inmate was "eaten alive by insects and bed bugs."

The Fulton County Sheriff's Office told NPR member station WABE it has launched an investigation into Thompson's death. The sheriff's office also acknowledged that the facility is "dilapidated and rapidly eroding" — adding that officials have approved $500,000 to address the issue of pests.

Still, his family, along with their attorneys, have called for the closure of the jail and requested a criminal investigation into Thompson's death. His family has not yet filed a lawsuit, but one is coming, according to WABE.

Kaepernick has paid for other autopsies

Last year, Kaepernick launched the Autopsy Initiative, offered through his Know Your Rights Camp organization, to offer free, secondary autopsies to family members of anyone whose death is "police-related."

"The Autopsy Initiative is one important step toward ensuring that family members have access to accurate and forensically verifiable information about the cause of death of their loved one in their time of need," he said.

Kaepernick's publishing agency did not immediately respond to NPR's request for comment Friday morning.

READ MORE  Tyrell Monroe, 13, and his brother Justin Monroe, 12, in their neighborhood in Washington. (photo: Marvin Joseph/WP)

Tyrell Monroe, 13, and his brother Justin Monroe, 12, in their neighborhood in Washington. (photo: Marvin Joseph/WP)

What the sixth-grader does know is that “not all cops are actually going to help you in the situation that you’re in,” he said, recalling his mother’s advice. Like many Black moms, Katrice Fuller, has had “the talk” with her young sons. It’s a rite of passage for Black children, the somber conversation about the special rules they must adhere to when talking to police, where to place their hands when pulled over in a traffic stop, tips on how to avoid becoming a target. People are more likely to think they’re dangerous, they’re told, so be careful.

But a new fear is creeping into “the talk” in the wake of the recent shooting of a Black teen in Kansas City, Mo. There have been tearful conversations, new rules about interacting with strangers and, for some, a sense of resignation. It’s another sign, parents say, that Black children, particularly boys — which research has found are often seen as older and bigger than they are by people of other races — are at risk.

On a quest to pick up his siblings from a friend’s house, 16-year-old Ralph Yarl mistakenly rang the doorbell of the wrong home. The White man who opened the door, Andrew Lester, 84, told police that he was “scared to death” by the late-night visitor, shooting him twice — once in the head and then again in the arm after Yarl fell to the ground.

With each new tragedy, there is also a growing sense of desensitization to the violence affecting Black children, families say. While parents say they are doubling-down on measures to keep their children safe, from tracking their movements through cellphone apps to stacking their schedules with activities to avoid trouble, they say it can feel futile in a climate hostile toward Black children.

“The Ralph Yarl story did shake me,” said Fuller, a D.C. resident, who has four sons, including Justin, who range in age from 3 to 13 years old. “It’s not uncommon that my 12- and 13-year-olds would grab their little brothers from an activity or something.”

Yarl survived the April 13 shooting and has returned home to recover, but Yarl’s mother, Cleo Nagbe, has said the “residual effect” of Yarl’s injuries is going to stay with her son “for quite a while.” A GoFundMe started by Yarl’s aunt has raised more than $3 million and he has spoken to President Biden. Lester, meanwhile, has been charged with two felonies, including first-degree assault, and faces up to life in prison. He pleaded not guilty.

The Kansas City, Mo., shooting has sparked protests across the state by activists who complained local police didn’t act quickly enough to arrest Yarl’s shooter and rekindled debate about the easy access of guns and when it’s appropriate to use lethal force for self-defense.

It’s also prompted many conversations within Black households about how teens can avoid similar situations.

Matthew, 14, a Black eighth-grader at a private Catholic school north of Atlanta, learned about the shooting from his mother.

“My mom said, ‘Did you hear about that boy who was shot when he went to pick up his siblings?’ I didn’t know, and she told me about it, and it made me feel like that could happen to me when I start driving,” said Matthew.

The teenager, who plays basketball, football and runs track, has 12- and 10-year-old siblings. If he’s ever tasked with bringing them home, he’ll be careful, Matthew said.

“I’ll make sure I’m at the right house. I’ll call my brother and ask him to come outside,” he said. He has also been thinking of ways to stop the next shooting, Matthew said. “This wouldn’t happen as much if gun control was a thing. People aren’t going to run outside and kill you with a knife. People are less likely to be harmed if they couldn’t use guns.”

Matthew’s mother, Almaz, 49, said it’s easy to imagine her children in Yarl’s place.

“I just want my son to know what the world is like and to be careful. Children are so innocent and unaware, and I can totally see any of my children making a mistake like that,” said Almaz, who asked that her family’s last name not be published to protect their privacy. “And even now, I considered sending my daughter across the street to give her Girl Scout cookies to a customer, but I said, ‘No, no, no.’ She could go to the wrong house.”

Ty Jones, a Black Atlanta 14-year-old, says he doesn’t want to be paralyzed by the fear of what might happen to him if he knocks on the wrong door. “I thought about it happening to me,” said Jones, who loves baseball and music. “But if I walk around being scared of everything and everyone around me, I won’t get anything done.”

His mom says she hasn’t spoken to him specifically about Yarl. “If you’re having these heavy conversations as frequently as these horrible things are happening, I personally feel that’s stealing his childhood and any joy he can have as a kid,” said Tisha Jones, 40.

It’s just another burden for children already navigating a world in which they are often singled out because of their skin color, Jones said.

“We don’t want to exist in fear, but especially as he is getting older and will be going out in the world more independently, I can’t help but worry,” she said. “I know that all moms worry, but there is an extra layer of worry. To know that a judgment can be passed on him on sight because he’s a Black boy, it’s just scary.”

Thirteen-year-old Tyrell Monroe, the brother of Justin Monroe, says he has been thinking about his safety in the days since Yarl was shot but doesn’t want the threat of violence to affect his everyday life. “When I’m outside, I don’t think about it as much, but I’m still conscious about it,” he said. To avoid trouble, he keeps to himself. “I try to be in my own lane when I’m outside.”

He doesn’t feel free, Tyrell says, including to do simple things outside, like telling jokes. People might not understand his dark sense of humor, he says. And “it could put me in danger.”

Personal safety was already a frequent topic at home after repeated shootings of young people in the District. Last month, a former classmate, 17-year-old Dalaneo Martin, was fatally shot in the back by U.S. Park Police. The Justice Department has opened a civil rights investigation into Martin’s shooting.

This week, the brothers recited their mother’s reminders to be aware of their surroundings and look out for each other. If they found themselves in danger, they would try their best to de-escalate the situation and get away.

Underneath their cool exterior, their mother senses something else may be going on. “They don’t push to go outside, they don’t push to go to social gatherings,” she said. She worries they are becoming desensitized to the violence affecting Black children. “It’s just another one, another one, another one,” Fuller said.

And she knows there are limits to how much she can do.

Tyrell, the 13-year-old, is approaching six feet tall and has locs growing past his shoulders, which his mom fears can make it more likely others will see him as a threat. The 13-year-old is also on the autism spectrum, inviting even more assumptions.

“He stims. His hands might flap, eyes will flutter,” she said, referencing some of the repetitive behaviors Tyrell displays in stressful situations. She warned him: “They won’t think ‘Oh, I’m looking at you as a kid on the spectrum, a 4.0 [GPA] student.’ They can’t see that looking at you.”

News about racist incidents, along with racism itself, takes a toll on young people’s mental health, research shows. In a survey conducted by the AAKOMA Project, a mental health nonprofit, 18 percent of young people of color said they had experienced “racial trauma often or very often” in their lives.

More than half of the respondents said they have dealt with anxiety, depression or both, said Alfiee Breland-Noble, a psychologist and AAKOMA Project founder. Children are not only reeling from racism but other stressors, including the lingering effects of the social isolation they experienced during the pandemic.

“These young people are experiencing the negative impacts of what it means to have a marginalized identity,” said Breland-Noble, who has a Black 16-year-old son. She added that many parents assume their children are too young to have anything to worry about, but data show that’s not true. “The first thing parents have to do is, we have to be willing to close our mouths and open our ears … we have to acknowledge that our young people are dealing with things that sometimes we don’t know anything about.”

Elani Dwyer, an 18-year-old high school senior from East Orange, N.J., said that she is not confident that anything will change anytime soon.

“You’re always going to be seen as a threat, as much progress as this country or the world will ever make, because there’s so many stigmas and stereotypes about the Black community, it’s going to be so hard,” she said.

Until recently, Dwyer lived and attended high school in Radnor, Pa., a mostly White and affluent suburb of Philadelphia, through a program called A Better Chance that places students of color in homes in the suburbs with adult supervision.

Dwyer said that she felt isolated at the school and in the community and it began affecting her mental health. She decided to leave in the middle of her senior year and transfer to a school in her hometown. The four years of living in a mostly White community took a toll on her, she said.

“You have to put your best foot forward at all times,” said Dwyer. “But it shouldn’t even be like that, where you have to prove to people that you’re not a threat. It’s exhausting. You get burnt out. Being in a community where you don’t feel welcomed is exhausting.”

America needs to address its gun problem and systemic racism, she says, but society may already be broken at a more fundamental level.

“At the end of the day, it’s like you don’t feel safe anywhere to be honest, there’s just a lot of stuff happening so it’s about being cautious,” she said. “We need to go back to the basics, just being kind to other people, kindness is really important and people overlook that a lot and take that for granted.”

READ MORE  An Ohio voter, Lysha Ingle, signs a petition to place an amendment protecting abortion rights in the state constitution on the ballot in November. (photo: Maddie McGarvey/NYT)

An Ohio voter, Lysha Ingle, signs a petition to place an amendment protecting abortion rights in the state constitution on the ballot in November. (photo: Maddie McGarvey/NYT)

After abortion rights supporters swept six ballot measures last year, Republican legislatures seek to make it harder to get on the ballot, and harder to win if there is a vote.

Now, with abortion rights groups pushing for similar citizen-led ballot initiatives in at least six other states, Republican-controlled legislatures and anti-abortion groups are trying to stay one step ahead by making it harder to pass the measures — or to get them on the ballot at all.

The biggest and most immediate fight is in Ohio, where a coalition of abortion rights groups is collecting signatures to place a constitutional amendment on the ballot in November that would prohibit the state from banning abortion before a fetus becomes viable outside the womb, at about 24 weeks of pregnancy. That would essentially establish on the state level what Roe did nationwide for five decades.

Organizers were confident that the measure would reach the simple majority needed for passage, given polls showing that most Ohioans — like most Americans — support legalized abortion and disapprove of overturning Roe.

But Republicans in the state legislature are advancing a ballot amendment of their own that would raise the percentage of votes required to pass future such measures to a 60 percent supermajority. The measure has passed the Ohio Senate and is expected to pass the House this week.

The Republican measure — which would require support from only 50 percent of voters to pass — would go before voters in a special election this August.

“There are a lot of elected officials leading state legislatures that are being unapologetic, brazen, relentless — choose your adjective — about the fact that they don’t care what voters think on this issue and that their ideological stance on this is going to dictate the outcome,” said Kelly Hall, executive director of the Fairness Project, which supports citizen-sponsored ballot initiatives across the country as a check on gerrymandered state legislatures.

Republicans in Ohio have said openly that their efforts to make ballot amendments harder to pass are aimed at blocking abortion rights. They are putting their measure on the ballot in August, typically a time of low turnout. It will not include the word “abortion,” which abortion rights supporters say will make it hard to engage their voters.

The House sponsor of the ballot amendment for the 60 percent threshold argued in a letter to colleagues that without it, “all the work accomplished by multiple Republican majorities will be undone, and we will return to 19,000+ babies being aborted each and every year.”

Mike Gonidakis, the longtime president of Ohio Right to Life, an anti-abortion group, said that he had worked on behalf of the legislative leadership to get 60 House Republicans to publicly declare that they would support putting the amendment on the ballot in August if the speaker brought it for a vote. Mr. Gonidakis spent his family spring vacation in Florida rounding up that support. “This has been a labor of love,” he said.

He sees abortion as a “policy decision,” not a right, and said that policy should be left to the legislature alone. “Our Constitution is for our constitutional rights, not weed or gambling or abortion,” he said.

Republican-led legislatures in five other states are leading similar efforts to block citizen-led measures. The North Dakota legislature this month approved a bill boosting the signature requirement for proposed constitutional amendments and requiring them to win approval in both primary and general elections.

And in Arkansas, after voters last fall soundly rejected a constitutional amendment proposed by the legislature stiffening the requirements to get a measure on the ballot, the legislature simply passed new requirements as state law. Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed the law last month.

While some legislators have targeted citizen-led initiatives on redistricting, voting rights for felons and legalized marijuana, abortion opponents and supporters alike agree that the Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe has supercharged the push for citizen ballot measures and Republican efforts to deter them.

Republicans were surprised by how forcefully voters turned out to reject anti-abortion laws last year, even in red states.

In Kansas, the Republican-controlled legislature put forward a ballot initiative that would have reversed a 2019 state supreme court ruling finding a right to abortion in the state Constitution. It was placed on the ballot in the August primary, when turnout is typically low, but abortion rights groups mobilized to defeat it.

In November, voters defeated a similar measure in Kentucky, along with an anti-abortion law in Montana. At the same time, they approved measures to recognize a constitutional right to abortion in Vermont, California and Michigan.

The decision to raise the threshold to 60 percent in Ohio probably was not an arbitrary choice, said Chris Melody Fields Figueredo, executive director of the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center, which works to support progressive ballot measures.

In other red and purple states — Michigan, Kentucky and Kansas — the vote for abortion rights was between 52 and 59 percent.

“When they’re raising the passage threshold to 60 or 65 percent, it’s often just a percent or a couple of points above what has been needed to pass initiatives in the past,” she said.

One Republican lawmaker who opposes the new limits on initiatives in Arkansas, State Senator Bryan King, said he believes the lure of power, not partisan politics, is the driving force behind them.

“I don’t think this is a party issue. This is a control issue,” he said. “It’s trying to fence off challenges to whatever decisions a government makes.” That desire for control has been constant, he said, regardless of which party ruled the state over the past two decades.

Mr. King has joined a lawsuit seeking to strike down the new restraints on ballot initiatives in Arkansas. “One of the core beliefs I was taught in being a Republican is that we should make it easier for citizens to get things on the ballot and challenge what government does,” he said. The new Arkansas law, he said, “simply crossed the line.”

In Missouri, the Republican-led legislature is on the verge of putting a constitutional amendment on the November ballot raising the approval threshold for proposed constitutional amendments to 60 percent, from 50 percent. Voters, however, would be unlikely to know that the measure would do that. The proposal, passed by the House and sent to the State Senate, specifies that it be described on the ballot only as a measure to require voters to be properly registered U.S. citizens and Missouri residents — which the state Constitution already requires.

The chief sponsor of the measure, State Representative Mike Henderson, did not respond to phone and email requests for comment. In debate on the House floor, Republicans said they were not trying to deceive voters.

Legislatures began accelerating bans and other restrictions on abortion beginning a decade ago, after Republicans took control of more statehouses. Ohio has been at the forefront of those attempts. It was among the first states to attempt a so-called heartbeat law, banning abortion after roughly six weeks of pregnancy, when many women do not realize they are pregnant. (That law passed in 2019 and went into effect after Roe was overturned but has been temporarily blocked by a state court.)

The state made national headlines in July after a 10-year-old rape victim had to travel to Indiana to get an abortion because a doctor said her pregnancy was beyond six weeks.

Republicans in Ohio first filed the measure to increase the percentage of votes required to pass citizen-led amendments a week after the elections in November. It failed to pass, after demonstrators flooded the Statehouse and shouted from the legislative galleries.

Sponsors refiled the measure in the new term, adding the provision for an August election, which is estimated will cost $20 million. Their amendment would also add new requirements to get proposed amendments on the ballot: Proponents would have to collect signatures from at least 5 percent of the residents in all 88 counties in the state, up from the current 44.

The measure would also do away with the so-called curing period, which allows the proponents a week to collect additional signatures to make up for those that authorities disqualified.

Abortion rights groups say they are trying to gather 700,000 signatures, well above what they need to get their measure on the ballot before the July 5 deadline. And they are finding strong support as they canvass parks, shopping centers, concerts and athletic contests.

“I have circulated for ballot initiatives before. This is the first time in my life that I have not had to explain what I am carrying,” said Cole Wojdacz, the field manager for Pro Choice Ohio and one of the lead organizers for Ohioans for Reproductive Freedom. “People are chasing me down asking me if I have petitions. It’s like an awakening.”

Their first hurdle, however, is the Republican-led initiative in August. They fear it will be hard to motivate voters to the polls on what seems like an esoteric change to ballot law.

Just four months ago, Republicans in the legislature led passage of a law doing away with most August elections because they cost taxpayers too much and, as Secretary of State Frank LaRose argued at the time, had “embarrassingly low turnout.”

Mr. LaRose, a Republican who supports the August election to raise the threshold for ballot measures, added that August elections tend to mean “just a handful of voters” make big decisions. “The side that wins is often the one that has a vested interest in the passage of the issue up for consideration,” he said in his written testimony at the time. “This isn’t how democracy is supposed to work.”

READ MORE  Okinawa. (photo: Richard Atrero de Guzman/NurPhoto)

Okinawa. (photo: Richard Atrero de Guzman/NurPhoto)

Leaders say PFAS contamination from military bases is threatening Indigenous lives and rights.

The foam contained per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals.” Used in a wide variety of consumer products, PFAS have been found in air, water, and the blood streams of humans and animals across the world and can impact health causing low birth weights, cancer, and liver damage.

More than 15 percent of Okinawa is occupied by American and Japanese military bases. In 2022, water tests conducted by the government of Okinawa revealed PFAS levels up to 42 times higher than Japan’s national water standards with contamination found in drinking and bathing water for roughly 450,000 people, about a third of the island’s population. Local residents, many of whom are Indigenous Ryukyu Uchinaanchus, say the latest firefighting foam incident was another example of the harm caused by U.S. military installations on their land.

“What happened shows that they don’t care,” said Masaki Tomochi, who is Ryukyu Uchinaanchu and a professor at Okinawa International University. “They don’t care about us.”

The U.S. military is building a new base on Okinawa that marine experts and the Okinawa prefectural government say could threaten marine ecosystems, including coral reefs and thousands of marine species, desecrate Ryukyuan ancestor remains, and bring even more pollution and contamination. This week, a group of Ryukyu Uchinaanchus is at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues calling for urgent intervention, including the halt of construction of the new base in Henoko, release of military groundwater test data, and the closure of all 32 U.S. military bases on Okinawa. They are also demanding the recognition of their rights as Indigenous peoples, which Japan refuses to grant, despite multiple recommendations from U.N. agencies, including the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and the Human Rights Committee to do so.

But without acknowledgement from the Japanese government, Ryukyuans have limited options. They say the United Nations is their only pathway to justice, and request that the Permanent Forum arrange a meeting between Ryukyuan leaders and Japan to talk, for the U.S. to create a chemical clean up plan, and immediately provide clean drinking and bathing water to all affected people.

“Our people have been fighting for so long,” said Koutarou Yuuji, Ryukyu Uchinaanchu and a PhD student at the University of Hawai’i at Hilo. “The bases are still there. Nothing happens.”

The independent, Indigenous Ryukyu Kingdom was annexed by Japan in 1879, when it became a prefecture in Japan’s empire. After World War Two, the United States took control of Okinawa for over twenty years, finally returning control to Japan in 1971. The agreement allowed for the U.S. military to maintain bases on the island and was made despite a movement that included violent protests by Ryukyuans for independence rather than a return to Japanese rule. Amid tensions with China, Japan and the U.S. cite Okinawa’s proximity to Taiwan as a key strategic reason for maintaining bases on the island.

“The lack of consultation with the Ryukyuan Peoples is a prime example of how neocolonial actions ignoring the Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) principles can magnify existing negative circumstances and create new ones,” Permanent Forum member and Standing Rock Sioux descendant Geoffrey Roth said, referencing the international human rights standard that grants Indigenous peoples control over development projects on their land.

In 2019, Japan recognized the Ainu as Indigenous peoples, but has continued to resist Ryukyuan claims. Ryukyuans say that this is largely because acknowledging them as Indigenous would threaten Japan’s ongoing relationship with the U.S. military. “FPIC has never existed in Okinawa, especially when it comes to the U.S.,” Alexyss McClellan-Ufugusuku, a member of the Association of Comprehensive Studies for Independence of the Lew Chewans and a PhD Candidate at U.C. Santa Cruz, said.

The Ryukyuans allege that U.S. military bases contribute to a host of environmental issues, including water contamination, noise pollution, erosion, and deforestation. In 2019, 70 percent of voters said they did not support the construction of the new base. Despite the vote, construction has proceeded.

“Being able to come to the Permanent Forum allows us to advocate in a different way outside of Okinawa,” McClellan-Ufugusuku said. “It also allows us to see connections between ourselves and Indigenous peoples all around the world. We’re not the only ones with water pollution issues. We’re not the only ones with U.S. base issues.”

The United States Department of Defense and the Japanese Government did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.