Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Two new books, ‘The Riders Come Out at Night’ and ‘Shielded,’ underscore the stubborn persistence of violence by officers

The remark has proved sadly accurate. In the years before my book and in the years since, we have witnessed innumerable cases of Black people subjected to vicious beatings and unjustified killings. Technology has brought this brutality into our living rooms as Black and Brown people armed with smartphones have recorded cops doing the violent and racist things that we always said they did but that many White people apparently did not believe.

Now everyone could see it with their own eyes. The evidence was indisputable, like those grainy TV images from the 1950s and ’60s of police officers spraying water hoses and siccing dogs on civil rights activists. Except that this new movement didn’t need Dan Rather. It had Darnella Frazier, the teenager who recorded Derek Chauvin squeezing the life out George Floyd with his knee on Floyd’s neck. Nor did the movement need CBS, because the revolution no longer had to be televised. Darnella was on Facebook.

But the advancement in technology has not led to an advancement in racial justice. The police still kill more than 1,000 people each year, and those people are disproportionately Black and Brown. Attention has not yet meant progress.

Two recent books propose ways forward, but the limited hope they offer is overwhelmed by the depravity of the misconduct they describe, as well as the persistent failure of politics and law to hold law enforcement accountable. The reader is left wanting not so much to petition a legislature or file a lawsuit as to throw a brick.

“The Riders Come Out at Night: Brutality, Corruption, and Cover Up in Oakland” is investigative journalists Ali Winston and Darwin BondGraham’s deep dive into the brutal history of the Oakland, Calif., criminal legal system — one dare not refer to it as a criminal “justice” system after this searing exposé. “Shielded: How the Police Became Untouchable” is law professor Joanna Schwartz’s rigorous examination of why, most of the time, dirty cops get away with violating their badges.

Winston and BondGraham make the case that a “reactionary” workplace culture within law enforcement agencies causes most reform efforts to fail. Even when the Justice Department takes legal steps after a federal investigation to order changes at a local police department, “back sliding is common. New abuses constantly surface,” the authors write. “Resistance to change imposed from outsiders, especially civilians, is baked into police culture in the United States.” Exhibit A for Winston and BondGraham is the Oakland Police Department, which has undergone more reform attempts than any other department in the country.

The book, a detailed history of Oakland told through the lens of policing, contains lots of juicy details. Black Panther Party co-founder Huey Newton arrived in the city as a boy, his family landing there as part of the Great Migration. His life has the epic rise and fall of a Shakespearean character — from killing a racist cop in what Newton maintained was self-defense, and being prosecuted for allegedly killing a sex worker who called him “baby,” a name he detested, to earning a PhD from the University of California, and later being gunned down on the streets of Oakland by another Black man. We learn that Robert Mueller’s failure to bring Donald Trump to justice in the Russia investigation was foreshadowed by his failure, when he was head federal prosecutor in Northern California, to hold accountable a gang of Oakland police officers known as the “Riders.” The book’s most dramatic storyline follows their vicious assaults on the Oakland residents whom they were supposed to be serving and protecting, and the heroic but unsuccessful effort of a rookie cop to bring them to justice.

But that’s just one of literally hundreds of abuses. At times, the detail becomes tedious and the corrupt cops indistinguishable. Winston and BondGraham intend their narrative as a cautionary tale for other cities and, ultimately, present changes undertaken by the Oakland Police Department as a success story. They write approvingly of the city’s most recent police chief, LeRonne Armstrong, a reformer who got the job after the previous chief, Anne Kirkpatrick, was fired for not effectively implementing court-mandated improvements. They claim, after 380 pages: “It is possible to reform the police. That’s one lesson Oakland can offer for the rest of the nation.”

And yet.

Since the book was published, Armstrong himself has been fired by Oakland Mayor Sheng Thao after he allegedly gave special treatment to Michael Chung, a sergeant accused of official misconduct. Chung had backed his car into another car, causing $14,000 in damage, and fled the scene. His passenger in the car was his girlfriend, a police officer who reported to him. He had not disclosed this relationship, in violation of department regulations. In a separate incident, Chung fired his service weapon in an elevator at police department headquarters, failed to admit that he was the shooter and, in an apparent effort to avoid detection, tossed the bullet casing over the Bay Bridge. Chung was a rising star on the force and one of the highest-paid Oakland police officers, earning almost $500,000 in 2021 between his regular pay and overtime. For the hit and run, the only sanction he received, with Armstrong’s blessing, was training and counseling. After the elevator episode, Chung was placed on administrative leave.

After the incidents became a local scandal, Armstrong claimed he wasn’t aware of all the facts, but an independent investigation found that his comments were not credible or consistent with the evidence. The investigation attributed some blame to “a failure of leadership” and found “issues and shortcomings that go beyond the conduct of individual officers to the very question of whether the Oakland Police Department is capable of policing itself and effectively holding its own officers accountable for misconduct.”

“Still corrupt after all these reforms” might not be the coda Winston and BondGraham intended, but Schwartz would not be surprised. “Shielded” has its share of stories, too, told with enough passion and eloquence to support Schwartz’s faith in suing the bastards, that great American engine of social change. The book’s central argument is that civil rights litigation against individual officers would advance reform more effectively than the rare criminal prosecutions of trigger-happy cops or federal takeovers of local police departments. Similar lawsuits have worked for environmental justice and voting rights, but the main problem for policing is a judicial doctrine the Supreme Court made up called “qualified immunity,” which, in the context of law enforcement, frequently translates to “You can’t sue me, I’m a cop.”

Schwartz would get rid of that doctrine, placing more hope in local lawmakers and judges than in the federal government to lift the barriers that insulate police departments from civil rights suits. When a cop is found liable, Schwartz would also have some of the money come right out of the cop’s paycheck, as opposed to public coffers, which is what happens now in most jurisdictions. She believes that would be the strongest incentive for street officers to do the right thing.

“Shielded” was inspired by the national reckoning on race and policing after Floyd’s death. Because Chauvin’s conduct was so sadistic, it was tempting to think of it as idiosyncratic. Schwartz’s prescription would be most effective if the biggest problem were bad-apples cops. “We cannot wait for another viral video to restart our national conversation about police violence and reform,” she writes. But, inevitably, new videos of police misconduct have gone viral since Schwartz wrote those words, and they suggest a different problem: The system is working the way it’s supposed to work. Memphis cops brutalized Tyre Nichols as though they thought they were doing regular police work.

Last month, police officers stopped Nichols, a young Black man, for reasons that are still unknown. The original police report stated that Nichols was pulled over for reckless driving, but the Memphis police chief has said she has seen no evidence of that. In any event, that police report was full of lies, as was the police report for Breonna Taylor, which said she was uninjured though the cops had pumped multiple bullets into her body, and the police report for Floyd, which left out the fact that Chauvin had put his knee on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes.

The Memphis cops yanked Nichols out of the car, refused to tell him why he had been stopped and physically assaulted him, including shooting at him with a stun gun. Nichols did what I would have done if I was being attacked by a gang of thugs: He ran. One cop on the scene said, “I hope they stomp his ass,” and when the police caught him, roughly eight minutes later, that was exactly what they proceeded to do. At one point when Nichols had been beaten so badly he couldn’t stand, one officer held him up so another could punch him in the head. Nichols died three days later. Five officers, all Black, were fired and are now charged with second-degree murder.

The most infuriating — and scariest — thing about the beatdown of Nichols is how rote the brutality seems. Nichols weighed 145 pounds, while each of the five officers implicated in his death weighs more than 200 pounds. Their heft seems part of the job qualifications for working in their special unit, which was called “Scorpion” (the department “permanently deactivated” the unit one day after the videos were released). Like other specialized squads all over the United States, Scorpion’s mission was to demonstrate to the citizens of Memphis that it was the toughest, meanest gang on the streets. Concerned about this style of policing, President Barack Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing recommended that “law enforcement culture should embrace a guardian — rather than a warrior — mindset.” The Scorpion cops were warriors on steroids.

In the videos released by the Memphis Police Department, Nichols does not appear to fight or otherwise threaten the officers; indeed, he is as polite as a man can be when he is being tortured to death. He says, “Please stop.” Maybe that’s why in the videos you hear the officers occasionally call Nichols “bro”; it’s their way of communicating that it’s nothing personal. The videos depict the police as not so much angry as hard at work, putting in time. As they beat Nichols, they pause occasionally to catch their breath. One cop stops to tie his shoes. Near the end of the videos, as a bloody and bruised Nichols is propped against a squad car, the cops do what a work team does when it successfully completes a project: fist bumps and congratulations all around.

Near the end of “Shielded,” Schwartz notes that the criminal legal system “desperately needs repair,” a claim that seems confirmed by the book’s exceptionally lucid and well-argued analysis. Still, when an apparently innocent citizen like Nichols is tortured and executed by armed agents of the state, reform seems not only unambitious but inadequate. And, of course, if the system is not broken — if it is working the way it is supposed to work — there is nothing to fix. The persistence of police violence, evidenced in all the viral videos and national reckonings, suggests that this is how many Americans prefer that some people be policed.

READ MORE  Fox News host Maria Bartiromo invited Trump campaign attorney Sidney Powell on her show to discuss allegations of election fraud based on an email laying out claims even the writer called 'pretty wackadoodle.’ (photo: Slaven Vlasic/Getty Images)

Fox News host Maria Bartiromo invited Trump campaign attorney Sidney Powell on her show to discuss allegations of election fraud based on an email laying out claims even the writer called 'pretty wackadoodle.’ (photo: Slaven Vlasic/Getty Images)

Joe Biden's victory caused Fox News personalities to all but melt down on the air. Off the air, a sense of crisis pervaded the private conversations of the network's executives and stars. Viewers who supported then-President Donald Trump abandoned Fox in droves after its Election Night team became the first in the nation to project that Biden would win the pivotal state of Arizona.

Desperate to win back the Trump supporters, Fox News and the Fox Business Network turned at least a dozen times to a pro-Trump attorney named Sidney Powell who, when pressed for evidence, forwarded a memo entitled "Election Fraud Info" to Fox anchor Maria Bartiromo. Bartiromo hosted Powell on her Fox News show the day after receiving it.

'Like time travel in a semi-conscious state'

The author of the memo in which Powell and Bartiromo put so much stock offered detailed and utterly false claims of how Dominion Voting Systems helped rig the election for Biden. She also shared a bit about herself, writing that she gains insights from experiencing something "like time-travel in a semi-conscious state."

The existence of the memo, its enigmatic author, and her role in Fox's broadcasts surfaced in a devastating 178-page legal brief filed by Dominion Voting Systems and made public last week by a Delaware court. The election-tech company has sued Fox News for $1.6 billion for defamation over the airing of false claims that it engaged in election fraud.

Powell's source also volunteered that the wind tells her that she's a ghost, though she doesn't believe it.

The woman, who is not named in the legal brief, wrote that she knew the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia had been killed during a week-long human hunting expedition at an elite social club. (Scalia, a favorite of many Fox News hosts, died in 2016 of a heart attack, according to local officials in Texas, where he died.)

And the woman asserted that the late Fox News chairman Roger Ailes and Fox Corporation founder Rupert Murdoch "secretly huddle most days to determine how best to portray Mr. Trump as badly as possible." By the time the woman wrote her memo, Ailes had been dead for more than three years.

"Who am I? And how do I know all of this?... I've had the strangest dreams since I was a little girl," the woman wrote in the email shared by Powell with Bartiromo and Dobbs. "I was internally decapitated, and yet, I live."

This all appeared in the same memo that claimed Dominion's software flipped votes from Trump to Biden, and tied the election company to a conspiracy involving Democrats Nancy Pelosi, then the House speaker, and Sen. Dianne Feinstein.

"The full force of the email's lunacy comes across by reading it in its entirety," Dominion's legal brief states. "Spurred by the November 8 Bartiromo broadcast," the election tech company's legal team wrote, "the wild Dominion allegations entered the mainstream." Dominion began sending journalists and executives at the network regular messages attempting to set the record straight - and putting the network on notice, according to the filing.

David Clark, then the senior executive over Fox's weekend shows, later said under oath to Dominion's lawyers that he "would not have allowed that claim to be aired," had he known this memo was the sole foundation of the "crazy" theories.

Dominion Voting System's lawyers would not comment further to NPR. Fox News and parent company Fox Corp. declined to comment on the email. More broadly, Fox has accused Dominion of mischaracterizing the record and cherry-picked quotes without the proper context.

Fox hosts and executives ridiculed Sidney Powell and her claims, while giving them a platform

Fox News stars and executives privately reviled their newsroom colleagues who told viewers that such claims were baseless, because such fact-checks alienated viewers.

Yet in some of the same conversations, the hosts and executives ridiculed Powell and her election-fraud claims. Their private communications and sworn testimony were also part of Dominion's filings.

"Sidney Powell is a bit nuts," Fox host Laura Ingraham wrote to stars Tucker Carlson and Sean Hannity on Nov. 15, 2020.

"Sidney Powell is lying," Carlson told his producer in a note the next day.

"Terrible stuff damaging everybody, I fear," Murdoch texted to Fox News chief executive Suzanne Scott on Nov. 19, after seeing Powell and Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani relaying unfounded claims of election fraud on the air. Scott agreed.

Others admitted under oath that they also shared those sentiments.

"[T]hat whole narrative that Sidney was pushing, I did not believe it for one second," Hannity said in a deposition conducted nearly two years later by Dominion's lawyers.

One of Dominion's attorneys asked Bartiromo while she was being deposed whether the email was "nonsense." The Fox News anchor agreed that it was.

Memo shared with Eric Trump, the former president's son, according to Dominion's legal filings

That's not how Bartiromo responded at the time.

On Nov. 7, just four days after Election Day, Powell sent Fox Business host Lou Dobbs and Bartiromo the memo. Powell appeared on Dobbs's show that day to push easily discredited conspiracy theories involving the CIA and Dominion. That night, Fox News followed other networks in projecting that Biden had won the presidential election.

Bartiromo replied glowingly to Powell, saying she had endorsed the information in the memo during a conversation with one of Trump's sons: "I just spoke to Eric … told him you gave very imp info."

The very next day, Nov. 8, Bartiromo invited Powell on her show and encouraged her to present her claims of fraud anew. "We've talked about the Dominion software," Bartiromo said to Powell on her show, Sunday Morning Futures. "I know that there were voting irregularities. Tell me about that."

Powell responded: "That is where the fraud took place, where they were flipping votes in the computer system or adding votes that did not exist."

She continued, "There has been a massive and coordinated effort to steal this election from 'We the people' of the United States of America."

Privately, Tucker Carlson texted to an associate that night, "[t]he software sh-- is absurd... Half our viewers have seen the Maria clip."

Bartiromo is a veteran financial journalist, with earlier stints at CNN and CNBC, where she became a star anchor. She joined Fox a decade ago to help give Fox Business greater cachet and respectability. She hosts 17 hours across Fox Business and Fox News each week.

Producer testifies 'wackadoodle' memo now not fit for air

Even before Election Day, Clark and Fox News chief political anchor Bret Baier separately told the network's top news executive, Jay Wallace, that Bartiromo was pushing false claims of fraud on social media.

By Nov. 8, Fox Business Network senior vice president Gary Schreier was warning the channel's president, Lauren Petterson, that Bartiromo "has GOP conspiracy theorists in her ear and they use her for their message sometimes."

As Dominion's lawyers noted, however, such skepticism about Bartiromo from senior executives did not inspire them to block her program that day or from rebroadcasting it hours later.

Bartiromo was not alone in possessing the memo; Dobbs received it too, and Bartiromo had shared that memo with a senior producer and top booker, Abby Grossberg.

Asked about it under oath by Dominion's attorneys late last summer, Grossberg said the memo "isn't something that I would use right now as reportable for air, no," according to the legal filings. Grossberg is now a senior producer and top booker for Fox's Tucker Carlson.

Two days after the fateful Bartiromo appearance, Powell turned up on Fox's air once more, this time on Ingraham's primetime Fox News show. Powell asserted, "We have demonstrable, statistical and mathematical and computer evidence of hundreds of thousands of votes being injected into the computer systems repeatedly."

She didn't. Republican and Democratic state and local officials disputed and disproved her claims. So did Trump administration election integrity officials - as did some Fox News journalists. No matter. Powell showed up on Fox News and the Fox Business Network airwaves again and again - with Dobbs, Jeanine Pirro, and Hannity, often explicitly implicating Dominion.

On Nov. 29, Bartiromo landed the first interview with Trump since Election Day, telling him, "This is disgusting and we cannot allow our elections to be corrupted."

Powell popped back up on Fox News the very next day.

"We've got evidence of corruption all across the country in countless districts," Powell told Hannity on Nov. 30, without presenting any evidence. "The machine ran an algorithm that shaved votes from Trump and awarded them to Biden. They used the machines to trash large batches of votes that should've been awarded to President Trump. And they used the machines to inject and add massive quantities of votes for Mr. Biden."

Powell was not the only Trump surrogate who had Fox's ear, or seen by its viewers, but her claims were repeatedly amplified, embraced, and given extraordinary air time. Bartiromo has never been publicly rebuked and has not been punished for her role in pushing these falsehoods; in January 2021 she tried out for Fox News' coveted 7 p.m. weekday slot now held by Jesse Watters. The next month, Fox forced out Dobbs the day after another voting tech company called Smartmatic sued the network.

Of Fox's main opinion stars, only Tucker Carlson directly challenged Powell on the air during the post-election season. "We took her seriously," Carlson told viewers on Nov. 19, 2020. "She never sent us any evidence, despite a lot of requests, polite requests. Not a page. When we kept pressing, she got angry and told us to stop contacting her."

Powell had spoken at a Trump campaign press conference earlier in the day in which she spun a web of already debunked false assertions. Carlson said, "She never demonstrated that a single actual vote was moved illegitimately by software from one candidate to another. Not one."

Even so, Carlson privately echoed Fox News executives angered by their news-side colleagues who publicly noted the false claims made by Powell and others publicly, including on Fox shows. They argued it fed the outrage of Trump fans toward the network.

On Jan. 26, 2021, three weeks after the violent siege of the U.S. Capitol by Trump supporters seeking to block congressional certification of Biden's win, Carlson invited on one of his main advertisers: Mike Lindell, the founder of MyPillow and a chief proponent of pro-Trump claims of election fraud.

Carlson gave Lindell plenty of time to make wild claims about Twitter, the media, and Dominion. On Carlson's show, Lindell dared Dominion to sue him, saying he had the evidence of voting fraud but "they don't want to talk about that."

"No, they don't," Carlson said tersely. Dominion filed its lawsuit against Fox News two months later.

READ MORE  Vice-President Kamala Harris. (photo: Bonnie Cash/EPA)

Vice-President Kamala Harris. (photo: Bonnie Cash/EPA)

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Over the weekend at the Munich Security Conference, Vice President Kamala Harris accused Russia of committing not just war crimes but crimes against humanity in Ukraine.

VICE PRESIDENT KAMALA HARRIS: The United States has formally determined that Russia has committed crimes against humanity. And I say to all those who have perpetrated these crimes, and to their superiors, who are complicit in these crimes, you will be held to account.

AMY GOODMAN: Secretary of State Tony Blinken followed up on Harris’s comments by saying in a statement, “We reserve crimes against humanity determinations for the most egregious crimes. These acts are not random or spontaneous, they are part of the Kremlin’s widespread and systematic attack against Ukraine’s civilian population,” Blinken said.

We go now to Geneva, Switzerland, where we’re joined by the longtime human rights attorney Reed Brody, who’s brought historic legal cases against former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, former Chadian dictator Hissène Habré and others; author of To Catch a Dictator: The Pursuit and Trial of Hissène Habré. He’s former counsel for Human Rights Watch.

Reed, thanks so much for joining us. Can you talk — I don’t know if people caught the shift right now for exactly what Vice President Harris, and I expect tomorrow President Biden in Poland will be saying.

REED BRODY: Well, Vice President Harris basically said what we all know to be true, which is that Russian forces are committing crimes against humanity in Ukraine. Secretary Blinken used — and, in fact, they both used the legal definition, which is crimes committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack on a civilian population. I think we all believe that, you know, the bombing of hospitals and schools, the torture, the sexual violence, the attacks on civilian infrastructures, the deportation of children, these all amount to crimes against humanity. I’m not sure, to be honest, what the — you know, why the statement was made, what legal significance it has that the U.S. has determined that crimes against humanity have been committed. She also talked about how the authors of these crimes will be held to account.

And, of course, as we’ve discussed before, there is a massive justice mobilization in Ukraine, surpassing any precedent by orders of magnitude. You have 66,000 war crimes cases opened by the Ukrainian prosecutor’s office. The International Criminal Court has opened its largest field operation ever. A dozen other states have jumped in to open up cases on their own soil. Many others have supplied assistance, financial, technical assistance to Ukrainian prosecutors. So there is a huge amount of investigation in real time like we have never seen before.

I don’t know what new this is going to bring. I mean, perhaps President Biden is going to explain. Obviously, the U.S., you know, has a very ambiguous relationship, in general, with international justice. It is not a member of the International Criminal Court. It does support, actually, under the Democratic administrations, including the Biden administration — support the work of the International Criminal Court. But we’ll have to really see what this declaration means. I mean, it is a very strong statement, and I think, in many — it is a welcome statement. Crimes against humanity are being committed by Russian forces in Ukraine.

AMY GOODMAN: Reed, we just had you on two weeks ago talking about the issue of war as a crime of aggression, and the problem that poses for the United States, because many might say, “Yes, that’s exactly what’s going on here, but for the United States to say that is to go against its previous positions.”

REED BRODY: Well, of course, I mean, the U.S. position on justice is — you know, on international justice is riddled with double standards. Look, the U.S.'s principal objection to the International Criminal Court is not that they're investigating Africans or they’re investigating these people; the U.S.'s principal objection is that the ICC purports to investigate crimes committed by citizens of nonstate parties. So, the U.S.'s big objection is that the ICC could, and was, until it was deprioritized by the prosecutor, investigate alleged U.S. war crimes in Ukraine. U.S. is not a party, but — excuse me, Afghanistan. U.S. is not a party, but Afghanistan is. The ICC, similarly, is investigating alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity by Russian forces, even though Russia, like the United States, is not a party to the ICC, but is allegedly committing war crimes and crimes against humanity on the territory of a state, Ukraine, which is a party.

The same double standard comes in, or would come in, in terms of aggression prosecutions. Now, Vice President Harris did not talk about the crime of aggression. And one interpretation of why she made such a strong statement on crimes against humanity this weekend is so that she didn’t have to talk about the crime of aggression, because the U.S. is tiptoeing around this issue, for the reason that you mentioned, Amy. The U.S., and the only reason —

AMY GOODMAN: I mean, right now we’re coming up on the 20th anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, right? In March of 2003.

REED BRODY: Exactly. The only reason the ICC does not — which is investigating Russia, nonparty state, investigating their alleged crimes against humanity and war crimes in Ukraine, but not their aggression, is — and many would say the only reason the ICC hasn’t already indicted Vladimir Putin for the crime of aggression, which was the supreme international crime at Nuremberg, is that the United States, Britain and France insisted, against the majority of the other states, that the ICC should not be able to exercise its aggression jurisdiction against nonstate parties, like the United States, France and Britain, but also like Russia.

So, I mean, again, it’s a very welcome statement, I believe, by Vice President Harris. Russia — these are massive crimes. I mean, we all continue to be shocked and horrified by these crimes. But America has to — the United States has to come to grips with the fact that, whether it’s crimes like the Bush administration, crimes against detainees in Guantánamo, in Abu Ghraib, in secret prisons, that were never dealt with, or the illegal invasion of Iraq by the United States in 2003, in 2002, you can never — you know, you can’t have it both ways. And the tools of international justice should not only be aimed at enemies and outcasts.

AMY GOODMAN: Reed Brody, I want to thank you for being with us, war crimes prosecutor, former counsel for Human Rights Watch, author of To Catch a Dictator: The Pursuit and Trial of Hissène Habré.

Next up, as the Centers for Disease Control warns teen girls face record levels of depression and hopelessness, we look at the role of social media. Back in 30 seconds.

READ MORE  A federal judge in Michigan issued a national injunction to prevent Starbucks from firing anyone engaged in union organizing. (photo: Brittany Greeson/NYT)

A federal judge in Michigan issued a national injunction to prevent Starbucks from firing anyone engaged in union organizing. (photo: Brittany Greeson/NYT)

A nationwide injunction restrains the company from dismissing labor organizers and could help reinstate ousted workers more quickly.

The move is the first nationwide judicial mandate related to the labor campaign that has led to the unionization of more than 275 company-owned Starbucks stores in little more than a year. Starbucks said it would appeal the decision.

Experts said the injunction would allow the National Labor Relations Board to come before the judge and seek more rapid reinstatement of workers who it believed had been terminated for union organizing. Normally, the process could take months or even years.

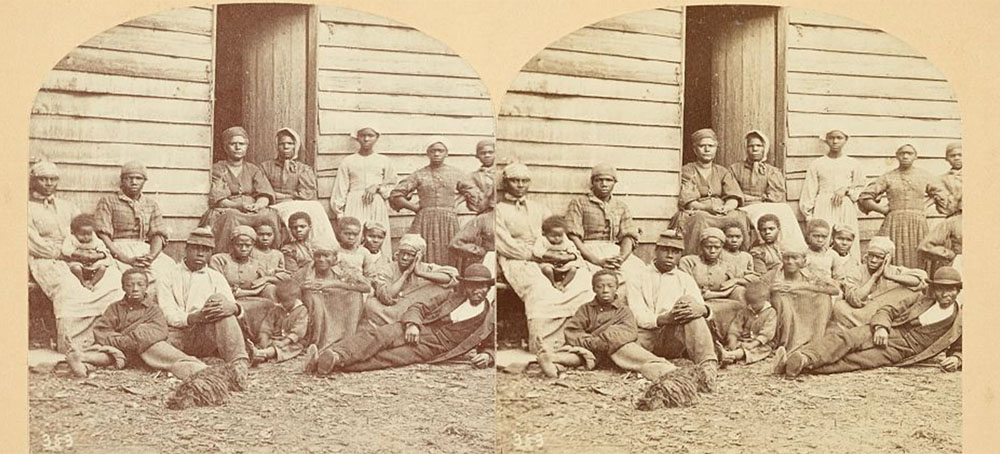

READ MORE  Stereograph showing a group of escaped slaves, including men, women, and children, gathered outside a building at the Foller Plantation in Cumberland Landing, Pamunkey Run, Virginia. May 14, 1862. (photo: James F. Gibson/Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons)

Stereograph showing a group of escaped slaves, including men, women, and children, gathered outside a building at the Foller Plantation in Cumberland Landing, Pamunkey Run, Virginia. May 14, 1862. (photo: James F. Gibson/Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons)

Today, on Presidents’ Day, we rightly celebrate Abraham Lincoln for helping end slavery. But we shouldn’t forget the unstoppable force that also brought down the Slave Power: the several million slaves who left the plantation, many of whom joined the Union Army.

Yet we know that from the onset of the war, slaves were increasingly forthcoming about their views. On Christmas Eve 1861, Kentucky whites watched as sixty slaves paraded “singing political songs and shouting for Lincoln.” That winter, as white Unionists sabotaged railroad bridges in the Upper South, Confederate authorities also began blaming disgruntled slaves for arson. At year’s end they blamed unsupervised slaves encamped in Charleston for a fire that swept through the city, destroying hundreds of buildings.

Elsewhere in South Carolina, authorities followed rumors into a swamp where they found an encampment of runaways growing their own crops. Soon after, Confederates in Adams County, Mississippi, found that field slaves had stashed arms and supplies in a similarly isolated maroon. Even as slaveholders repeated rumors of armed slave insurrections, they reported remarkably more pragmatic plans, such as that for “a stampede” of a hundred slaves into the wilderness or toward Union lines.

The authorities responded ruthlessly to maintain their power. Arkansas slaveholders executed blacks for an alleged plot at Monroe, while similar executions took place in May and June across the river in Mississippi. At New Orleans a dozen ships burned at anchor and, “on more than one plantation, the assistance of the authorities has been called in to overcome the open resistance of the slaves.” Similar rumors stirred central Kentucky and Tennessee.

At first, Federal authorities — even those who later became prominent emancipationists — balked at allying themselves with slave insurrection. In the war’s first weeks, General Benjamin F. Butler assured Maryland officials that his troops would prevent a servile insurrection there. As late as August 1862, Butler, then in Louisiana, worried that “an insurrection [that] broke out among the negroes” threatened whites. He squelched “the incipient revolt . . . by in- forming the negroes that we should repel an attack by them upon the women and children.” That fall, a threatened rebellion north of Thibodeaux concerned officials of the Federal occupation.

Confederate paranoia aside, African Americans sustained organizations of their own that pressed their own agenda. Black resistance to slavery had forced white supporters to help shape a new “underground railroad.” Even in the most contested and supervised circumstances in Virginia, enslaved black workers established and maintained their own associations. A Union prisoner at Staunton and a spy at Richmond stumbled onto these societies “composed almost exclusively of colored men.”

The growing numbers of aggrieved nonslaveholders, including armed Confederate deserters and escaped Union prisoners, provided slave rebels a growing number of whites ready to transgress the color bar. Civilian authorities far from Federal lines clamored for martial law and the assignment of troops to suppress small bands of armed blacks. Increasingly, Confederates feared a convergence of “deserters from our armies, Tories and runaways.”

By early 1864 Confederate officials in South Carolina reported “five to six hundred negroes” not in “the regular military organization of the Yankees” who “lead the lives of banditti, roving the country with fire and committing all sorts of horrible crimes upon the inhabitants.” Florida officials reported “500 Union men, deserters, and negroes . . . raiding towards Gainesville,” while similar groups formed to commit “depredations upon the plantations and crops of loyal citizens and running off their slaves.” At Yazoo City, Mississippi, they not only attacked such private estates but successfully burned the courthouse.

At times, black resistance fueled the worst Confederate fears, nowhere more famously than in Jones County, Mississippi. A Confederate conscript and deserter named Newton Knight organized and captained a small but effective band of guerrilla fighters.

The rolling strike of the slaves defied the official policies of both governments and made itself the great incontrovertible and irreversible fact of the war. It established the foundations for a substantive interracial cooperation and forced the capitulation of one of those contending governments to rethink and expand its war goals.

Through the summer of 1862, even as President Abraham Lincoln remained aloof from abolitionist proposals, he decided to expand the Union’s goals as commander in chief. In September, though, the president issued his “preliminary proclamation” of emancipation.

The Federal Government and the Transition to Wage Labor

The Federal government accepted emancipation because it had no alternative. The farther the Union armies penetrated into the South, the denser population of slaves responded with a general, though not universal, abandonment of the plantations.

On the Carolina coast, in the lower Mississippi Valley, and in the later march through Georgia, the numbers of enslaved workers who abandoned their labors and escaped to freedom came to outnumber the Union troops who seized and garrisoned these areas. Those who had been the most powerless and downtrodden people on the continent had placed emancipation beyond the control of presidents and generals.

African Americans had never entirely been strangers to wage labor. Some slaves as well as free blacks had participated in labor activities and organizations. The Waiter’s Protective Union at New York, a decade before the war, had surely not been unique. Almost as soon as the war ended, ongoing black labor discontent gave rise to local “ringleaders” and “troublemakers.” A South Carolina freedman named Sandy was described as one who “works when he chooses, and only such work as he chooses to do . . . all the time exciting the people with falsehoods and rebellions principles.” He and his followers appealed persistently to the Freedmen’s Bureau, but Federal concerns proved to be nothing if not ambiguous.

Associations for mutual aid sprang up across the South, some achieving considerable size and influence. The Church Pension Society of Freedmen at Columbia, South Carolina, appeared quickly enough to hint at older networks among blacks. African Americans in Tennessee established two prominent mutual-aid societies at Memphis and Chattanooga, the former strong enough to support on its own two hundred indigent freed people.

Other associations, such as the Union Progressive Association, organized blacks or sometimes racially mixed memberships. This “literary society of the colored men of Boston” sponsored a celebration of emancipation that drew “a very large attendance, a considerable portion of those present being white.

Most dramatically, the unexpectedly disastrous level of casualties opened one avenue of work, traditionally reserved for whites, to African Americans. As events drove the white South to an ever-heavier reliance on conscription and coercion, the Union turned to black troops. Strikers accounted for most of the roughly quarter-million soldiers who served in the “colored volunteer” regiments, where they performed the same work being performed by whites, though not at the same pay or under the same terms.

Nevertheless, military service imposed similar experiences upon black and white men, and many responded with an acknowledgement of the familiar. “You would be astonished,” Sergeant George Washington Beidelman of the Philadelphia Typographical Union assured his father, “to see in what short time these rough and uncouth, and hitherto despised and ignorant men, attain proficiency as good soldiers — both in drill and discipline. We have many visitors daily — both citizens and soldiers, and all are surprised and delighted. I think the Government has ‘hit the nail on the head’ in this instance; for it is evidently fast becoming its strongest arm for the suppression of the rebellion.”

Despite the Lincoln administration directive to commission black officers, the military high command placed whites in charge of such regiments. Many in power retained the racist expectations that the entire project was but a disaster in the making. Other white officers generally ascribed lesser status to a “nigger colonel” and, with many of the white soldiers, initially accorded black men in arms little respect. Finally, Confederate policy was to regard all black soldiers as slave rebels and their officers as instigators of slave rebellion, liable to summary execution.

Early on, radical abolitionists such as Elizur Wright urged black recruitment as an essential mechanism of a sweeping social reconstruction. Various African Americans became involved in such military activities through the work of a number of important recruiters. Martin R. Delany, James McCune Smith, William H. Day, and Peter Humphries Clark — who had long-standing, if selective, association with white radicals and labor reformers — seemed to see equal participation in the military as a means of fostering a more equal participation in the wider society.

Along the western border of the war, former Chartist and socialist Richard J. Hinton served in the First Kansas Colored, and then the Second Kansas Colored, the Seventy-Ninth and Eighty-Third United States Colored Troops. William H. T. Wakefield, future vice presidential candidate of the United Labor Party, served as a lieutenant among Arkansas black soldiers. The presence of such officers should not obscure the generally miserable experience of African Americans in uniform.

Whites generally chafed under the brutal discipline and hardship of nineteenth-century military life, but most black soldiers faced far worse. More than whites, they got pay, food, and shelter that often looked more symbolic than real. When they responded, as did members of the Corps d’Afrique at Fort Jackson December 1863, the full force of military law fell upon them. While the shadow of such insubordination and its repression might be short among whites, it remained a long, dark, and brooding presence over the African-American experience.

The Politics of Class and Slave Liberation

As Typographical Union brother Beidelman struggled to recover from wounds in both legs gotten at Gettysburg, he reflected on the war’s impact on his own racial views. He entered the war a small-town Jacksonian Democrat with no love for abolitionists or blacks.

However, he decided that emancipation came from “the house of the Lord — the refiner’s fire that will purify our nation.” He publicly challenged a bishop back home who had sermonized that slavery had not in itself been a sin. Recovering at a camp where they trained new black regiments, Beidelman had a transformative experience of interracial camaraderie. “Thank God, the inhuman and hell-begotten prejudices, which would deprive these people of the dearest privileges of men and citizens, are fast disappearing; and a new order of things will no doubt attend the results of this great rebellion and the cleaning out of the Augean stables of our political system.” By his death on March 14, 1864, Beidelman messed and socialized with his new black comrades and wrote of them with open admiration.

African Americans found some strong allies for equality, often with close ties to the abolitionist and antebellum labor currents. However, they were too few, too far between, and too preoccupied with the war to matter greatly until later, and then it proved far too little to counterbalance the great social weight of the plantation elite, particularly as it forgave the nation for its defeat and came back to the exercise of power. Moreover, even as the mass slave strike secured emancipation, Federal responses struggled to translate the achievement into an act of government philanthropy that had nothing to do with what the slaves or abolitionists had done.

But from a labor perspective, the slave strike repressed an uncompromising and overwhelming appeal to numbers. It introduced a qualitatively new kind of mass action.

READ MORE  An artisanal miner carries a sack of ore at the Shabara artisanal mine near Kolwezi on October 12, 2022. (photo: Junior Kannah/AFP/Getty Images)

An artisanal miner carries a sack of ore at the Shabara artisanal mine near Kolwezi on October 12, 2022. (photo: Junior Kannah/AFP/Getty Images)

Cobalt Red examines the tech-fueled “modern-day slavery” in the Congo

Kolwezi is tucked in the hazy hills of the southeastern corner of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Although most people have never heard of Kolwezi, billions of people could not conduct their daily lives without this city. The batteries in almost every smartphone, tablet, laptop, and electric vehicle made today cannot recharge without Kolwezi. The cobalt found in the dirt here provides maximum stability and energy density to rechargeable batteries, allowing them to hold more charge and operate safely for longer periods. Remove cobalt from the battery, and you will have to plug in your smartphone or electric vehicle much more often, and before long, the batteries may very well catch on fire. There is no known deposit of cobalt-containing ore anywhere in the world that is larger, more accessible, and higher grade than the cobalt under Kolwezi.

Cobalt is typically found in nature bound to copper, and the copper-cobalt deposits in the Congo stretch in varying degrees of density and grade along a four-hundred-kilometer crescent from Kolwezi to northern Zambia, forming an area called the Central African Copper Belt. The Copper Belt is a metallogenic wonder that contains vast mineral riches, including 10 percent of the world’s copper and about half the world’s cobalt reserves. In 2021, a total of 111,750 tons of cobalt representing 72 percent of the global supply was mined in the DRC, a contribution that is expected to increase as demand from consumer-facing technology companies and electric vehicle manufacturers grows each year.1 One might reasonably expect Kolwezi to be a boom town in which fortunes are made by intrepid prospectors. Nothing could be further from the truth. Kolwezi, like the rest of the Congolese Copper Belt, is a land scarred by the mad scramble to feed cobalt up the chain into the hands of consumers across the globe. The scale of destruction is enormous, and the magnitude of suffering is incalculable. Kolwezi is the new heart of darkness, a tormented heir to those Congolese atrocities that came before— colonization, wars, and generations of slavery.

The first European to cross the heart of the African continent in a single trip from east to west, British lieutenant Verney Lovett Cameron, ominously wrote this about the Congo in The Times on January 7, 1876:

The interior is mostly a magnificent and healthy country of unspeakable richness. I have a small specimen of good coal; other minerals such as gold, copper, iron and silver are abundant, and I am confident that with a wise and liberal (not lavish) expenditure of capital, one of the greatest systems of inland navigation in the world might be utilized, and from 30 months to 36 months begin to repay any enterprising capitalist that might take the matter in hand.

Within a decade of Cameron’s missive, “enterprising capitalists” began pillaging the “unspeakable richness” of the Congo. The great Congo River and its capillary-like tributaries provided a built-in system of navigation for Europeans making their way into the heart of Africa, as well as a means by which to transport valuable resources from the interior back to the Atlantic coast. No one knew at the outset that the Congo would prove to be home to some of the largest supplies of almost every resource the world desired, often at the time of new inventions or industrial developments — ivory for piano keys, crucifixes, false teeth, and carvings (1880s), rubber for car and bicycle tires (1890s), palm oil for soap (1900s+), copper, tin, zinc, silver, and nickel for industrialization (1910+), diamonds and gold for riches (always), uranium for nuclear bombs (1945), tantalum and tungsten for microprocessors (2000s+), and cobalt for rechargeable batteries (2012+). The developments that sparked demand for each resource attracted a new wave of treasure seekers. At no point in their history have the Congolese people benefited in any meaningful way from the monetization of their country’s resources. Rather, they have often served as a slave labor force for the extraction of those resources at minimum cost and maximum suffering.

The rapacious appetite for cobalt is a direct result of today’s device-driven economy combined with the global transition from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy. Automakers are rapidly increasing production of electric vehicles in tandem with governmental efforts to reduce carbon emissions emerging from the Paris Agreement on climate change in 2015. These commitments were amplified during the COP26 meetings in 2021. The battery packs in electric vehicles require up to ten kilograms of refined cobalt each, more than one thousand times the amount required for a smartphone battery. As a result, demand for cobalt is expected to grow by almost 500 percent from 2018 to 2050 and there is no known place on earth to find that amount of cobalt other than the DRC.

Cobalt mining in towns like Kolwezi takes place at the bottom of complex supply chains that unfurl like a kraken into some of the richest and most powerful companies in the world. Apple, Samsung, Google, Microsoft, Dell, LTC, Huawei, Tesla, Ford, General Motors, BMW, and Daimler-Chrysler are just some of the companies that buy some, most, or all their cobalt from the DRC, by way of battery manufacturers and cobalt refiners based in China, Japan, South Korea, Finland, and Belgium. None of these companies claims to tolerate the hostile conditions under which cobalt is mined in the Congo, but neither they nor anyone else are undertaking sufficient efforts to ameliorate these conditions. In fact, no one seems to accept responsibility at all for the negative consequences of cobalt mining in the Congo — not the Congolese government, not foreign mining companies, not battery manufacturers, and certainly not mega-cap tech and car companies. Accountability vanishes like morning mist in the Katangan hills as it travels through the opaque supply chains that connect stone to phone and car.

The flow of minerals and money is further obscured by a web of shady connections between foreign mining companies and Congolese political leaders, some of whom have become scandalously rich auctioning the country’s mining concessions while tens of millions of Congolese people suffer extreme poverty, food insecurity, and civil strife. There was not a single peaceful transfer of power in the Congo from 1960, when Patrice Lumumba was elected to be the nation’s first prime minister, until 2019, when Félix Tshisekedi was elected. In the interim, the country was subjected to one violent coup after another, first with Joseph Mobutu, who ruled the Congo from 1965 to 1997, followed by Laurent-Désiré Kabila’s reign from 1997 to 2001, followed by his son Joseph Kabila from 2001 to 2019. I use the words rule and reign because Mobutu and the Kabilas ran the country like despots, enriching themselves on the nation’s mineral resources while leaving their people to languish.

As of 2022, there is no such thing as a clean supply chain of cobalt from the Congo. All cobalt sourced from the DRC is tainted by various degrees of abuse, including slavery, child labor, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and toxic working conditions, pathetic wages, injury and death, and incalculable environmental harm. Although there are bad actors at every link in the chain, the chain would not exist were it not for the substantial demand for cobalt created by the companies at the top. It is there, and only there, where solutions must begin. Those solutions will only have meaning if the fictions promulgated by corporate stakeholders about the conditions under which cobalt is mined in the Congo are replaced by the realities experienced by the miners themselves.

Today’s tech barons will tell you that they uphold international human rights norms and that their particular supply chains are clean. They will assure you that conditions are not as bad as they seem and that they are bringing commerce, wages, education, and development to the poorest people of Africa (“saving” them). They will also assure you that they have implemented changes to remedy the problems on the ground, at least at the mines from which they say they buy cobalt. After all, who is going to go all the way to the Congo and prove otherwise, and even if they did, who would believe them?

READ MORE  Students drink bottled water during their math class at Wilkins Elementary School in Jackson. (Joshua Lott/WP)

Students drink bottled water during their math class at Wilkins Elementary School in Jackson. (Joshua Lott/WP)

Jackson, Mississippi, Still Has No Reliable Water. Racial Distrust and Political Brinkmanship Fueled the Crisis.

Robert Samuels and Emmanuel Martinez, The Washington Post

Excerpt: "As government at every level tries to untangle generations of systemic failure, residents in Jackson, Mississippi, still have no reliable water."

As government at every level tries to untangle generations of systemic failure, residents in Jackson, Miss., still have no reliable water

“Please do something about our water,” Javaris pleaded to Michael Regan, the EPA administrator. Sometimes, the water from pipes came out thick and oily and brown. Other times, the water did not come out at all. That morning, pressure was so low that classes were canceled, costing precious learning time.

“I am not a plumber,” Javaris said later, as he recalled the November 2021 conversation. “I’m 11.”

Regan promised to do everything he could to help. But the problems got worse. Since Regan’s first visit 15 months ago, there have been at least 150 instances when the city has told subdivisions, schools, hospitals and churches in Jackson that their water might be unsafe to drink, according to data compiled by The Washington Post. The city’s main supply has been shut off at least four times, including one stretch last summer when residents subsisted without drinkable water for 45 days. During the holidays, an arctic blast froze Jackson’s pipes again, delaying Christmas gift exchanges while residents began a familiar scramble for bottled water.

The national attention dissipated after last year’s the state of emergency, but the state of normalcy is just as unsettling. At Wilkins, even when there is no calamity, Javaris and his classmates take bottles of water with them to flush toilets. There’s no water to wash their hands — the teacher must provide hand sanitizer. Green tape covers drinking spouts in the hallway. In this almost-exclusively Black community in the heart of the South, it is still a privilege for children to use the water fountain.

Sometimes, pools of black goo emerge when residents draw baths in their homes. When water pressure goes low suddenly, residents run outside with buckets and break open fire hydrants.

“We can’t trust that we’ll get water,” said Ray Charles, 61, after one such incident in the fall. “This is what we are used to. And it’s a damn shame.”

This account of why an American city of 150,000 has failed to provide its residents with a basic necessity of life — and how that has devastated the community — is based on more than four dozen interviews with residents, water experts, civic leaders, and local, state and federal officials; as well as a review of water policy studies, city records, staff emails and three decades of infrastructure plans. The Post also analyzed the locations and frequency of notices issued since 2017 advising residents to boil their water.

The review made clear that Jackson’s water crisis was not the result of one bad weather event or a single case of human error or even short-term neglect. It is a tragedy years in the making — born of racial distrust, political brinkmanship and systemic failure at every level of government.

Decades of suspicion and animus between a conservative White political power structure and a liberal majority-Black city have consistently led to circular arguments about who is to blame for the problem and who should be responsible for fixing it. That tension persists today in the state Capitol, as lawmakers battle over new legislation that, if passed, would chip away at Jackson’s elected leaders’ ability to run their own city.

As the two sides have sparred, water shut-offs have become more frequent, more widespread and more routine with each year — especially in the city’s least affluent neighborhoods.

In those communities, residents fear the consequences of this continued crisis, especially for children and pregnant people who are vulnerable to a host of health problems that result from ingesting lead and other contaminants in water.

An NAACP civil rights complaint against the state filed in September with the federal government pointed to those concerns, quoting nine public health experts who stated that “contaminated drinking water, such as that in Jackson, contributes to higher rates and more severe incidences of illness and disease in Jackson than in other areas with better overall health baselines.”

State officials have lambasted the city for hatching incomplete plans, ignoring paperwork and mismanaging public finances.

“Absolute and total incompetence” is how Mississippi’s White Republican governor, Tate Reeves, described Jackson’s handling of its two water plants, which are teetering on a total breakdown.

“Racist” and “paternalistic” is how Jackson’s Black Democratic mayor, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, described Reeves’s treatment of his city to The Post. During Lumumba’s tenure, state lawmakers have rejected at least 135 bills that would have given grants or loans to Jackson.

Since Regan visited Wilkins, he has tried to use the might of the federal government to resolve the issue. For decades, the department largely left the city and the state to handle their disputes. But in October, the agency opened a civil rights investigation into whether the state has treated the city fairly. In November, the EPA worked with the Justice Department to file a court order against the city — a necessary step that allowed them to bring in an outside manager to oversee the water system.

In December, the department helped to usher in a massive new infusion of money — $600 million tucked into the spending bill signed by President Biden — to help fund new operators, training programs and maintenance.

But even as city leaders greeted the federal money as a potentially game-changing win, there were worries that funds would fall into the same decades-long squabbles that have stifled the city’s progress. About $150 million is supposed to be sent directly to Jackson, officials said. The other $450 million must go through the state’s coffers first — leaving residents wary of possible meddling.

“If the state wants to play chicken, we’re game for that,” Regan told leaders at a community roundtable in September, according to a recording obtained by The Post. “But I believe that if we work together with the state of Mississippi … I believe that the resources can be where they need to go.”

At the meeting, Charles Taylor, the head of Mississippi’s NAACP chapter, reminded Regan that he was dealing with a state that rejected funds to expand Medicaid, returned money for rental assistance and is ensconced in a scandal involving using welfare dollars to make sweetheart deals with celebrities — all decisions that disproportionately affected Black people.

The crisis has been unfolding during a period in which the country struggles with when, or if, it should address the lingering impact of centuries of structural racism. The debates are not theoretical in Jackson. For residents, the stakes are clear: If those issues remain unaddressed, Javaris’s school might never have reliable running water.

As residents sat in blocks-long lines waiting for free bottled water in last year’s summer heat, City Council Vice President Angelique Lee received an invitation.

Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann wanted to meet with her in the state Capitol to discuss solutions to the water crisis. Lee wanted the opportunity to chat, but she was skeptical; she had heard of so many times when the state’s leaders had come up with plans that the city found offensive.

This meeting, much to her dismay, featured one of those plans: Hosemann offered his staff to write her a resolution calling for the city council to give up oversight of Jackson’s water system. Instead, power over the water system would be turned over to a regional board of nine people, mostly chosen by state leaders. Only three members would be chosen by Jackson’s leadership.

Hosemann, whose office acknowledged “many meetings” about Jackson’s water plants but declined to discuss specifics, presented the plan as a way to get more experienced personnel running the system.

But it played into Lee’s worst suspicions.

To Lee, the history of racial terrorism and Jim Crow laws showed that many White leaders feel Black people don’t have the ability — or shouldn’t have the power — to manage public resources. They lived in a region in which Black farmers had land seized from them, losing the chance to build intergenerational wealth. And in the past decade, Lee had witnessed the state’s failed attempt to oversee the city schools and another effort to take over the city’s airport, which is awaiting a court ruling.

“I remember [former mayor] Tony Yarber saying, ‘They’re trying to take our resources,’” Lee said. “It’s not just the water. The state has a history of underfunding things that are Black-related.”

Ashby Foote, a council member who is White and its lone Republican, did not think the idea was so bad if it brought help to the city. He warned that the past can sometimes cloud the judgment of the present. “We have more baggage than Samsonite when it comes to this stuff,” Foote told The Post. “The challenge is what we can do today to solve the crisis today. I don’t know that it’s necessarily productive to fall back into the narrative of, ‘This is the Whites being mean to a Black city, blah, blah, blah.’”

Lee could not ignore that narrative. Alarmed, she contacted Lumumba, who shared her worries.

“There is a consistency in what is taking place,” Lumumba warned. “We just have to be vigilant enough to pay attention.”

The possibility that the state government could usurp control played in the back of the minds of Jackson officials each time they discussed the crisis. They had to work with state leaders — but did not fully trust them.

The focus of discussions might have been about water, on its face. Under the surface, though, Lee and Lumumba saw another episode in a long battle for a Black city’s right to determine its own fate.

When the O.B. Curtis Water Treatment Plant was christened in 1994, news reports show, Mayor Kane Ditto said the project would ensure “residents have safe clean water for many, many years to come.” Sitting on the city’s northern border, the additional facility was intended to meet the needs of a community that had relied on one plant built in the early 1900s.

By the time Harvey Johnson became the city’s first Black mayor in 1997, Jackson had a serious problem. A study showed the existing pipes would be unable to withstand pressure from the new water facility. The pipes were old and corroded and small, some as tiny as two inches in diameter.

The most troubled pipes tended to be in the city’s poorest and Blackest neighborhoods. Johnson was unsurprised. He had seen a similar pattern across the state, in which the disparities between access to water in Black neighborhoods and in White neighborhoods were so stark that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit in 1971 asserted that cities could not discriminate against races when distributing municipal services. That case, Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, reflected the legacy of water policy in Mississippi.

Johnson estimated that fixes to the water and sewer system would cost $400 million. But he needed to figure out how to get the funds to a city that was losing money, people and power.

Once a sprawling metropolis of 200,000, the capital city’s population had been decreasing since the 1970s, after White families settled in the suburbs following a court mandate to integrate schools.

And when Johnson became mayor, he felt that he was treated as if he lacked the know-how to do the job, despite his background as a city planner. Even for something as small as landscaping flowers at a state park near city hall, he recalled skeptical state officials asking him: “Do you have a plan for that?”

It reminded him of the premonition that former Atlanta mayor Maynard Jackson, the first Black leader of a major city in the South, shared when Johnson entered office: “You will have high expectations from your Black residents and high anxiety from the Whites.” Johnson said he had to find ways to balance both.

"I think the opposition was because of who I was, not the position that I occupied,” Johnson said. “You feel it. It’s just like when you go into a department store and all of a sudden you got somebody walking around, seeing if you are going to take anything.”

Johnson became widely known for his decision to take Confederate flags out of city buildings and to take down a portrait of Andrew Jackson that hung over the chambers in City Hall. None of these acts endeared him to the mostly rural, White lawmakers in the state Capitol who regularly rejected his proposals for financing.

In 2009, the state legislature finally approved a bill Johnson hoped could help raise more money for city operations. The bill would allow the city’s residents to vote on a 1 percent sales tax to raise money, which would generate around $13 million a year.

There was a caveat: The ballot question included the creation of a commission that would oversee how the money was being spent — with less than one-third of the members being from the city’s actual government.

Johnson found the offer insulting but put the measure on the ballot in 2012 as the city’s problems continued to accrue. The measure passed. But then came another financial setback. That same year, in the twilight of his third term, the EPA discovered that the city had been dumping untreated sludge into the Pearl River, a primary source for Jackson’s reservoir. The discovery forced the city to plan more than $400 million in repairs over the ensuing 18 years, according to news reports.

Debts rising, Johnson and the city council looked for alternatives to raising water rates on their residents.

In 2013, new Mayor Chokwe Lumumba – the father of the current mayor — and the city council implemented a deal with a German tech company named Siemens that offered to build more accurate meter readers, potentially saving $120 million a year.

With the Siemens contract and the new 1 percent sales tax approved by voters, city leaders hoped they could have enough money to fix the pipes.

But by then, the O.B. Curtis plant had begun to deteriorate.

The massive system was hard to maintain as staff took higher-paying jobs in the suburbs, leaving the remaining workers to conduct draining, days-long shifts. At times, the plant’s staffing dwindled from 35 to seven, according to city records previously reported in USA Today.

By 2015, the state’s health department reported that parts of the plant were clogged with dirt and grime. The pumps were so out of whack that they could not properly filter water. The problems continued to worsen as pipes aged.

Over time, inspection records show, the state found 55 cracks per every 100 miles of pipe — almost four times higher than the EPA’s acceptable standard.

In sum: The city’s water system was potentially dangerous, unsanitary and inefficient — as much as 50 percent of water was lost when it flowed through Jackson’s leaking pipes.

Citing Jackson’s “significant deficiencies,” the EPA in 2020 issued a blistering report to the city’s mayor.

“The city of Jackson failed to fully implement lead and copper tap monitoring requirements,” one part read.

“The city of Jackson failed to conduct public education tasks and failed to provide required consumer notifications related to lead action level exceedences,” another said.

O.B. Curtis was not the gem the city had expected. Mary Carter, a former plant manager who complained about being overworked, referred to it with a dreary nickname: “My problem child.”

he 1 percent sales tax commission had done little to fix the problem child.

A battle began almost immediately over who should have the power to determine how the money would be spent. City leaders argued that they had a right to draft plans to improve roads and water systems on their own. But members such as Pete Perry, the head of the Hinds County Republican Party and a gubernatorial appointee, bristled that the city was working without them. In some instances, Perry said, city officials would request money for one purpose and spend it on another.

Perry, who is White, told The Post that the city’s leaders were treating the rest of the board like mushrooms — “keeping us in the dark and feeding us bulls---.”

“We have a right to draw up plans, with y’all’s input, because that’s what the law said to do,” Perry said he tried to explain to city officials. “You’re not supposed to hand it to us.”

The relationship with Siemens, the company that was paid to fix the water meters, was also in disarray. City staff continued to find broken meters that were installed incorrectly, creating even more financial pain for the city, according to court documents.

As revenue from the water and sewer system continued to dry up, the city’s water supply was becoming even more broken.

More residents and businesses began receiving alerts that their water might be unsafe because of problems with pipes connecting to each of the city’s 60,000 water meters. Those warnings, issued in the media and on the city’s website, instructed people to boil water used for “cooking or baking, making ice cubes, taking medication, brushing teeth, washing food, mixing baby formula or food, mixing juices or drinks, feeding pets, washing dishes and all other consumption.”

In 2019, there were 10,000 times when the city alerted that a water meter was connected to a pipe producing questionable water, The Post’s analysis shows. Just one year later, the number skyrocketed to 115,000.

The problems happened in some communities so often that receiving boil water notices became a disturbingly frequent part of life.

The city’s less affluent communities were the most impacted, according to an analysis of six years of boil water notices. Families living in neighborhoods with a median household income of less than $50,000 a year received notices twice as often as those who lived in wealthier parts of town.

The daily difficulties piled up for residents. Sheila Davis, 62, complained that each morning, her faucet would spew colors that went from brown to green to yellow to clear. Diedre Long, a paralegal who is part of the NAACP complaint, estimated spending $125 a month on water bottles. She worried about her adult daughter, who is colorblind and could not gauge whether the water looked safe to drink. Imelda Brown, 74, complained of water so oily that she would not even use it to make dinner.

In the suburbs, newly constructed highways led to outdoor malls with Apple Stores and upscale neighborhoods with water fountains. In Jackson, restaurants were opting to use paper plates. Portable toilets lined school sidewalks. Sometimes, during a water shut-off, schoolchildren would be bused across the county line just so they could have a hot lunch or shower after football practice — a form of reintegration that only solidified distinctions between them and others.

Concerned at how frequently schools were closing because of low water pressure, Erica Jones of the state teachers union sent representatives to survey parents near the check-cashing store, the supermarket and the local Piggly Wiggly. In more than 1,300 interviews, they found that well over 90 percent of parents said they did not trust the city’s water supply.

They were nervous for their children. Charles Wilson III, 61, had vowed to be a great dad to his youngest boy, Charles V. He had lost Charles IV as an infant, and he could not bear the idea of seeing another son suffer.

He had thought water was the solution. So, as a single father, he mixed the baby formula himself. He fixed his boy soup. He’d chide his child if he grabbed a soda after coming home from play. “Drink water,” Wilson told him.

During prekindergarten, Wilson’s youngest son began complaining of headaches and had frequent fits of diarrhea. Wilson said doctors often dismissed the boy’s complaints — a familiar experience, according to surveys showing that racial bias often leads medical professionals to under-treat Black patients for pain compared with how they treat White patients. By the time lawyers began investigating the health impacts of Jackson’s water supply, Wilson’s youngest son, now 6, had trouble focusing and regulating his mood.

“I thought water was basic,” Wilson said. “And then to learn those pipes have been messed up for years — years — and I knew nothing.”

Wilson is a part of a pending class-action lawsuit alleging negligence from the city in treating its water supply. His attorney, Corey Stern, was the architect of a similar lawsuit in Flint, Mich., that resulted in a $600 million settlement with the state. What Stern has seen in Jackson is far worse than Flint, he said. The crisis in Michigan took time to resolve, but the problems abated after city leaders switched back from the new water supply to an old one.

In Jackson, Stern said, he found a “comedy of errors from the jump.” Decades of neglect had built upon decades of neglect.

“It’s not to minimize Flint, but when you look at Jackson, I don’t know how Mississippi could have failed so badly,” Stern said. “In Flint, the problem covered one administration. Jackson covers multiple governors, city councils, multiple state officials and mayors.”

Jackson officials said they do not comment on pending litigation.

A U-shaped staircase stands in the back of Jackson’s city hall, adorned with photos of those mayors. Ascending, smiling portraits of White mayors are hung on one side. The city’s Black leaders preside on the other side, starting with Johnson.

The display ends with a portrait of Mayor Lumumba, who captured national headlines when he was elected in 2017 a part of a cohort of new Black lawmakers that were now leading major cities in the South. They vowed to find new solutions to old problems, carrying a wave of activism that ignited throughout the country after the election of former president Donald Trump.

Lumumba also wanted to carry the legacy of his father, the civil rights activist and former mayor after whom he was named, in helping to restore dignity to the residents. And for him, the ultimate indignity was the exploitation of Black residents.

Still, as he searched for new solutions, he faced the consequences of the unaddressed problems of the past. He tried to recoup money by suing Siemens, citing “fraud” and a “bait-and-switch,” according to court documents.

The city and the company reached a settlement in 2020 in which Jackson got back the $90 million it had paid.

A Siemens spokesman declined to comment on the settlement, referring to a joint statement that said: “Although the project did not end as either party hoped, the City recognizes the efforts of Siemens personnel to identify solutions to challenging issues throughout the course of its work.”

The settlement money vanished quickly after attorney’s fees and loan repayments. And because the water bills were still inaccurate, Lumumba did not feel comfortable forcing residents and businesses to pay them. Budget records show that, as of 2020, residents owed the city more than $65 million in unpaid water bills.

If the deficit was created through the acts of man, the system’s weaknesses were vulnerable to acts of nature, deepening the problem.

Heavy rains meant more unprocessed water would have to be filtered through a busted system that already had trouble functioning. Freezes were known to lead to pipe bursts.

The high-profile water shut-offs of 2021, which brought national media attention and prompted the visit by the EPA’s Regan, gave some local officials hope that they might finally get the help they needed. That year, they asked the state for $47 million — a number they figured was reasonable. The state offered just $3 million for corrosion control for the older of Jackson’s two water plants – nothing for Curtis, “the problem child,” the source of most of the city’s troubles.

Local lawmakers watched angrily as the state legislature allocated more than a billion dollars in loans and grants to other parts of the state, for what they saw as far less consequential concerns. The state purchased furniture for a country music museum and helped to finance boat ramps, football fields, a children’s museum and an aquarium. Forty-three bills drafted to help Jackson died in committee.

“These are the politics: There’s a real feeling that if Jackson had a Republican — or a White person — representing us, we wouldn’t be dealing with this,” said city council member Aaron Banks, who is Black. “And so, in some people’s mind, that carries over into what they do and how they vote legislatively.”

Banks acknowledged that there were problems with the city’s proposals. Gov. Reeves, who did not respond to requests for comment, told reporters at the time that Jackson needed “to do a better job collecting their water bill payments before they start going and asking everyone else to pony up more money.”

Some Democrats from the city council to the state legislature were stunned by the city’s lack of preparation to make its case. To justify the $47 million, the city had distributed a vague PowerPoint presentation to state and federal lawmakers listing needed repairs and their costs. The plan did not describe where the money would come from, nor did it include details about increasing staffing or how the money would be managed.

Rep. Bennie G. Thompson (D-Miss.), whose district includes Jackson, lambasted the city for going months without a lobbyist to help. Members of both parties in the state legislature blamed the city council for giving Jackson a bad reputation through public disputes about how it operates other services, such as garbage pickup.