Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Those most responsible for this global crisis must finally be held accountable.

To face this crisis, we must act quickly on two fronts: fostering international cooperation and holding accountable those most responsible for the crisis in the first place.

The latest report from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is clear and foreboding. If the United States, China and the rest of the planet do not act swiftly to cut carbon emissions decisively, our planet will face enormous and irreversible damage.

Let me be clear about that last part: If the entire world, led by its largest economies — the United States of America and China — does not get its act together quickly, we will leave our children and future generations a world that is increasingly unhealthy and uninhabitable.

Dealing with this crisis is so difficult and so complicated no individual nation can solve it alone. It is a global crisis. It requires the cooperation of every nation on Earth. Whether we like it or not, we are all in this together.

For example, the U.S. faces frightening impacts from climate change, but highly populated Asian countries are confronting even worse challenges. Sea levels on China’s coastline are rising more quickly than the global average. Major coastal cities like Shanghai, Tianjin and Shenzhen could face catastrophic flooding in years to come — creating havoc with the entire Chinese economy. Some project that Shanghai, a city of 24 million, could be underwater by the end of the century.

Developing a mutually beneficial relationship with China to save the future of this planet will not be easy. Sadly, “hawks” in both countries are working hard to create a new cold war.

But we — the United States, China and other countries around the world — still have time to aggressively combat climate change and prevent irreparable damage to our countries and the planet.

In addition to fostering international cooperation on climate change, in the United States, and around the world, we all must also ask a very simple question: How did we get here?

How did we get to a place in time where the health and well-being of the entire planet, and the lives of billions of people, is under enormous threat?

Recognizing the cause of this complicated crisis clarifies our way forward. Fortunately, the answer is straightforward. The scientific community, for many decades, has made it crystal clear that climate change — and all the dangers it poses in terms of drought, floods, extreme weather and disease — is the result of carbon emissions from the fossil fuel industry.

In the 1950s, physicist Edward Teller and other scientists warned executives in the fossil fuel industry that carbon emissions were “contaminating the atmosphere” and causing a “greenhouse effect” that could eventually lead to temperature increases “sufficient to melt the icecap and submerge New York.” That’s what they were saying 60 years ago!

The industry’s own scientists agreed. In 1975, Shell-backed research concluded that increasing atmospheric carbon concentrations could raise global temperatures and drive “major climatic changes.” The researchers compared the dangers of burning fossil fuels to nuclear waste. And beginning in the late 1970s, Exxon — now ExxonMobil — conducted extensive research on climate change that predicted current rising temperatures “correctly and skillfully,” according to a recent study.

The fossil fuel companies knew.

They knew they were causing global warming and threatening the very existence of the planet.

Yet, in pursuit of profit, fossil fuel executives not only refused to publicly acknowledge what they had learned, but, year after year, lied about that existential threat. And they continue to fund misinformation campaigns today.

So what happened to the CEOs who betrayed the American people and the global community? Were they fired from their jobs? Were they condemned by pundits on cable television and the editorial boards of major newspapers? Were they prosecuted?

Nope. Not a one of them. These CEOs got rich.

It’s obscene.

When a criminal walks into a store and shoots the clerk behind the counter, we make the moral judgment that this behavior is socially unacceptable, and that the gunman should be punished.

When a public official misuses and steals taxpayer money, we make the moral judgment that the embezzler should lose his job and, perhaps, be incarcerated.

Yet, when fossil fuel executives make calculated decisions that threaten millions of lives — and the planet itself — we are told that “it’s just business.”

That’s not acceptable.

That is why, earlier this week, I sent a letter to Attorney General Merrick Garland urging him to bring lawsuits against the fossil fuel industry in relation to its longstanding and carefully coordinated campaign to mislead consumers and discredit climate science in pursuit of massive profits. The letter was co-signed by Sens. Jeff Merkley, Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey.

Like the tobacco industry before them, the fossil fuel companies’ actions represent a clear violation of federal racketeering laws, truth in advertising laws, consumer protection laws, and potentially other laws. The Justice Department must hold them accountable.

More than 40 states and municipalities have filed lawsuits that seek to hold the fossil fuel industry liable in relation to its campaign of misinformation around climate change. The Justice Department must join the fight and work with partners at the Federal Trade Commission and other law enforcement agencies to file suits against all those who participated in the fossil fuel industry’s conspiracy of lies and deception.

The fossil fuel industry must begin to pay for the extraordinary damage it has caused and continues to cause every day. Climate change is an existential threat to every person on Earth. At every level, in every country, we must work together to save the planet for our kids and future generations. And those most responsible for this global crisis must finally be held accountable.

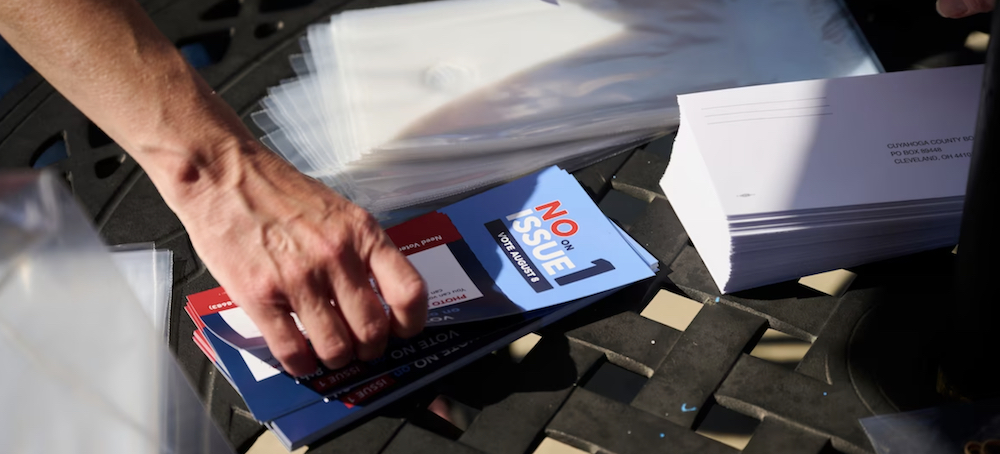

READ MORE  Volunteers assemble voter information packets in West Park, Ohio, on July 7, urging voters to vote "no" on State Issue 1. (photo: Dustin Franz/WP)

Volunteers assemble voter information packets in West Park, Ohio, on July 7, urging voters to vote "no" on State Issue 1. (photo: Dustin Franz/WP)

With 2.7 million votes counted and 87% of precincts reporting, Issue 1 trailed 57% to 43%, a margin sufficient for the Associated Press the call the race even as more votes have yet to be tabulated.

Issue 1 opponents, including organized labor groups, Democrats and abortion-rights activists, declared a cathartic victory at a firefighters’ union hall in Columbus less than two hours after polls closed on Tuesday evening. The result was a rare rebuke of Republican power in Ohio reminiscent of the 2011 vote to repeal Senate Bill 5, a bill that scaled back collective-bargaining rights for government employees.

“I’m so happy I don’t know what to do with myself,” labor activist Deidra Reese began her speech by saying.

Issue 1 backers blamed voter confusion and the well-funded opposition campaign.

“You can spend $50 to 75 million dollars and convince anyone that what’s right is left and left is right. That’s what they’re doing right now,” said Mike Gonidakis, the Ohio Right to Life president who was a prominent Issue 1 backer.

“I think it was a question worth asking of the voters,” said Senate President Matt Huffman, a Republican who was a key figure pushing for the August election after a previous effort to place it on the May ballot stalled. “Not only because of the two issues on the ballot in November [abortion rights and recreational marijuana], but because of the six to 10 that are planned over the next couple of years.”

The fall of Issue 1 turns the page on the August election and attention almost immediately will focus on November, when Ohioans will vote on a ballot issue that would enshrine abortion rights in the state constitution. Issue 1′s failure will make it much more likely that the measure will pass. Polling and election outcomes in other states last year suggest the measure has a good chance of passing but not with 60% of the vote.

“What I think this really shows is Ohioans preserved their ability to make their own decisions without government interference,” said Dr. Marcella Acevedo, a Cleveland-area physician who’s one of the leaders of the abortion-rights campaign.

Issue 1 would have required 60% of voters to approve the abortion-rights issue or any other future proposed constitutional amendments, up from the longstanding 50% plus one-vote requirement. It also would have made it much harder for citizen groups to get amendment proposals on the ballot by requiring them to gather signatures from all 88 Ohio counties, instead of half, and eliminating a 10-day “cure” period for campaigns to gather more signatures if they initially fall short.

Describing Issue 1 as “a battle worth having,” Gonidakis downplayed the implications of a big loss on the prospects for anti-abortion groups defeating a proposed abortion amendment in November during a CNN interview. Gonidakis said there likely are voters who oppose abortion who voted against Issue 1, giving abortion opponents a higher ceiling in November than the “yes” coalition had for Issue 1.

“At the end of the day we’ve been laser focused on November since January,” Gonidakis said. “This was just step one in the process.”

Although the “no” campaign has bipartisan elements, its backbone is a left-leaning coalition of organized labor, abortion-rights activists and Ohio Democrats. The defeat of Issue 1 is one of the biggest wins for this group since 2011, when a similar coalition repealed Senate Bill 5.

“The results of this special election show the impact of a united labor movement,” Ohio AFL-CIO President Tim Burga said in Columbus on Tuesday.

Ohio Democrats have hoped that defeating Issue 1 in August and passing the abortion-rights measure in November could give them rare momentum heading into the 2024 election, when Sen. Sherrod Brown, one of the state’s few remaining statewide elected Democrats, will face what’s widely expected to be a tough reelection campaign.

The abortion issue loomed large over the campaign, including prompting Republican lawmakers to schedule Issue 1 for a vote in the first place.

But the pro-Issue 1 campaign generally sidestepped the issue, focusing their appeals to voters on arguing a 60% bar would prevent deep-pocketed groups from writing their interests into the state constitution, or reframing the issue as a protection against liberal groups that want to promote progressive views on gender in classrooms.

Both approaches are a tacit acknowledgment that abortion rights are politically popular, and that the abortion-rights amendment is likely to clear 50% in November.

The “no” campaign meanwhile framed Issue 1 as an attempt by politicians to take electoral power away from the public. Some ads mentioned abortion by accusing Republican Secretary of State Frank LaRose and others of trying to game the rules to block a vote on a policy a majority of Ohioans support. The campaign benefitted from some Republican support, including from former Attorney General Betty Montgomery and ex-Gov. Bob Taft, 2000s-era Republicans who opposed Issue 1.

The campaign against Issue 1 also benefitted from a resource advantage. The “no” side outspent the “yes” side, $12.5 million to $9.7 million on TV ads, though both sides spent roughly equal amounts on ads the final week before the election. National groups overwhelmingly funded both sides of the campaign, viewing Issue 1 as a trial balloon that potentially could be replicated in other states where abortion-rights advocates are preparing ballot issues, including Florida and Missouri.

Ohio becomes the third right-leaning state in the past two years to defeat a proposal to hike the number of votes state constitutional amendments must get to pass. Voters in Arkansas and South Dakota overwhelmingly defeated similar measures last year, although those proposals saw nowhere near the spending that surrounded Issue 1, and lacked the crucible that the abortion issue provides.

Ohio is one of the 17 U.S. states where voters can propose state constitutional amendments. Since it was put into place in 1914, voters have approved 19 of 71 citizen-initiated amendments, most recently in 2017, when voters overwhelmingly approved a proposal expanding rights for crime victims. Nine of the 19 amendments that passed failed to clear 60%, including a 2009 measure that legalized casino gambling, and a 2006 measure hiking the minimum wage to $6.85 an hour, although it’s since gone up with inflation.

There has been for years a push and pull between majority parties in the states that allow citizen-initiated constitutional amendments and outgroups that have used them to pursue policies that the dominant party refuses to take up. In 1992, Ohio Republicans successfully convinced voters to impose term limits on state legislators, helping dislodge entrenched rural Democrats like Vern Riffe, who served as Ohio House speaker for 20 years.

But increasingly in recent years, constitutional amendments have become a path for national left-leaning groups to get voters in red-leaning states to approve populist economic ballot issues, like expanding Medicaid eligibility or hiking the minimum wage. This tension between left-leaning ballot-issue groups and Republican lawmakers intensified after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in in June 2022. Groups like Planned Parenthood and the ACLU successfully introduced and passed an abortion-rights amendment in Michigan, and are pursuing them in Ohio, Missouri and Florida.

Although Issue 1 was close tied to the November abortion vote, its defeat also preserves better odds for future ballot issues, including potential 2024 measure to hike the minimum wage to $15 or a redistricting reform effort backed by Maureen O’Connor, a Republican who retired from the Ohio Supreme Court last year.

READ MORE  Donald Trump. (photo: Erin Schaff/NYT/Redux)

Donald Trump. (photo: Erin Schaff/NYT/Redux)

ALSO SEE: Copy of Trump-Pence Electors Memorandum

The House Jan. 6 committee’s investigation did not uncover the memo, whose existence first came to light in last week’s indictment.

The existence of the Dec. 6, 2020, memo came to light in last week’s indictment of Mr. Trump, though its details remained unclear. But a copy obtained by The New York Times shows for the first time that the lawyer, Kenneth Chesebro, acknowledged from the start that he was proposing “a bold, controversial strategy” that the Supreme Court “likely” would reject in the end.

But even if the plan did not ultimately pass legal muster at the highest level, Mr. Chesebro argued that it would achieve two goals. It would focus attention on claims of voter fraud and “buy the Trump campaign more time to win litigation that would deprive Biden of electoral votes and/or add to Trump’s column.”

READ MORE A military officer paid respects to Ian Fishback, a paratrooper and Special Forces officer who dared to challenge the Army on its soldiers’ sustained abuse of Iraqi and Afghan men in their custody. (photo: Lindsay Morris/NYT)

A military officer paid respects to Ian Fishback, a paratrooper and Special Forces officer who dared to challenge the Army on its soldiers’ sustained abuse of Iraqi and Afghan men in their custody. (photo: Lindsay Morris/NYT)

Ian Fishback, who left the Army with the rank of major, was a dissident-in-uniform who died at the age of 42 after entering a dizzying mental health spiral.

The ceremony, held on a bright morning at Arlington National Cemetery, came almost two years after Mr. Fishback, 42, died of cardiac arrest while in court-mandated mental health care in Michigan. Among those who gathered were much of his family along with fellow veterans, former students and many admirers.

They came to pay respects to a paratrooper and Special Forces officer who dared to challenge the Army on its soldiers’ sustained abuse of Iraqi and Afghan men in their custody. The ceremony also offered a morning for his family and supporters to reflect on what they regard as his unnecessary death while awaiting care from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

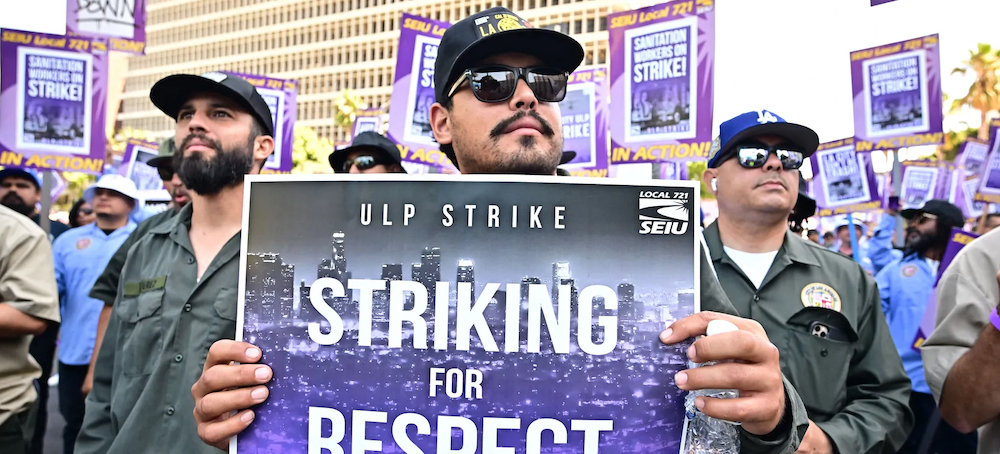

READ MORE Los Angeles city workers walk off the job for a 24-hour strike in Los Angeles, California, on August 8, 2023. The walkout is the first major city worker strike in at least 15 years, and it means residents will face an array of service disruptions, from trash-pickup delays to swimming-pool closures. (photo: Frederic J. Brown/AFP)

Los Angeles city workers walk off the job for a 24-hour strike in Los Angeles, California, on August 8, 2023. The walkout is the first major city worker strike in at least 15 years, and it means residents will face an array of service disruptions, from trash-pickup delays to swimming-pool closures. (photo: Frederic J. Brown/AFP)

Airport employees, sanitation workers, and more have authorized their first strike in 40 years.

In the Los Angeles service worker strike — which includes sanitation workers, airport employees, traffic officers, and engineers — a core issue centers on hundreds of vacancies that have long gone unfilled. Union workers say they’ve had to shoulder added tasks due to those staffing shortages, and that has left people extremely overworked and forced to take on recurring overtime. These stressors have led Los Angeles city workers in the union to authorize the first strike they’ve staged in over 40 years.

The plan, according to the leadership of the SEIU Local 721 union, to which the city’s service workers belong, is to picket and rally in front of City Hall and at the Los Angeles International Airport for one day in a bid to “shut down” Los Angeles and compel the city to address their concerns. Service workers are integral to the city’s daily functions including everything from shuttle buses to trash pickup to airport operations, and disruptions are expected in all of these areas.

“The message we’re sending is that our workers are just fed up. They’ve reached a breaking point. And we need these folks in the city to come back to the table for the good of the city,” David Green, SEIU Local 721 executive director and president, told the Washington Post.

The union is calling the city out specifically for unfair labor practices and is accusing LA leaders of failing to bargain in good faith. The union says the city hasn’t properly negotiated on a number of issues after saying it would do so following a one-year agreement that was made between the two parties in 2022.

The city, meanwhile, claimed in a statement to the New York Times that it has been engaged in bargaining since January. “The city will always be available to make progress 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass told the Times.

The union and the city are poised to sit down again for talks next week.

The Los Angeles service workers’ strike adds to a wave of strikes that have taken place this summer amid a labor movement resurgence fueled by higher living costs, a tighter labor market, and inequities made clearer by the pandemic. In LA alone, there is an ongoing strike of both the Screen Actors Guild and the Writers Guild of America as their members push for better compensation and fairer residual payments. Additionally, hotel union members of Unite Here Local 11 have been striking in Los Angeles intermittently throughout the summer to call for higher wages and improved benefits.

Why this has been a summer of strikes

The Los Angeles service workers’ strike is part of an uptick in such actions in the last two years. As Vox’s Rani Molla reported, 2022 and 2023 have seen an especially high number of work stoppages compared to prior years, and they’ve seen both strikes and increased organizing taking place across a broad spectrum of industries.

“All these different struggles, all happening at the same time, in all these different industries, involving all these different groups of workers, all making these connections between their struggles,” Barry Eidlin, an associate professor of sociology at McGill University, told Molla. “You’re seeing that in a way that I have not seen in my lifetime.”

There are multiple reasons we’re witnessing this surge in strikes and a bolstering of the labor movement, Molla explains. For one, inflation has led to increases in living costs that have not been met with commensurate increases in wages. And even as corporations have seen strong profits during the pandemic, much of that hasn’t been shared with workers on the front lines who are doing the bulk of the labor. The inequities of this dynamic have been further exacerbated by the fact that many front-line workers were publicly praised and hailed for the personal risks they took during the pandemic, but then not properly compensated for it.

Additionally, workers have been empowered by a relatively strong labor market and low unemployment rate, which has meant that they have more leverage in certain industries to push forward such demands. Coincidentally, several major unions have contracts that are up for negotiation or poised to expire this year, leading to more collective actions happening at this time.

Experts also say there has been a major increase in what’s known as “horizontal solidarity,” or workers in different industries supporting one another’s strikes or inspiring them. Such backing stems from shared frustrations and threats that people in different industries have faced, including the rise of artificial intelligence, climate change, and stagnant wages.

“The unions themselves have increasingly understood, ‘Hey, next time it could be us,’” Susan Schurman, a professor at Rutgers University’s labor and management school, told Molla. “Part of it is just understanding that the economy is now much more interconnected.”

READ MORE  Jim LaBelle, 76, at home in Anchorage. LaBelle is an Indian boarding school survivor who as a child was addressed by a number instead of his name. (photo: Salwan Georges/WP)

Jim LaBelle, 76, at home in Anchorage. LaBelle is an Indian boarding school survivor who as a child was addressed by a number instead of his name. (photo: Salwan Georges/WP)

Forced by the federal government to attend the schools, Native American children were sexually assaulted, beaten and emotionally abused

Taken from their homes on reservations, Native American children — some as young as 5 — were forced to attend Indian boarding schools as part of an effort by the federal government to wipe out their languages and culture and assimilate them into White society.

For nearly 100 years, from the late 1870s until 1969, the U.S. government, often in partnership with churches, religious orders and missionary groups, operated and supported more than 400 Indian boarding schools in 37 states, according to the first investigation into the schools by the U.S. Interior Department. Government officials and experts estimate that tens of thousands of Native children attended the schools over several generations, though no one knows the exact number. Thousands are believed to have died at the schools. Many others were sexually assaulted, physically abused or emotionally traumatized.

Now a reckoning is underway as Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna tribe whose grandparents were stolen from their homes and sent to boarding schools, tours the country to expose the devastating legacy of the schools on families and tribes. At the same time, a major nonprofit group, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, is collecting tens of thousands of documents on Indian boarding schools to build an interactive, digital archive that is expected to launch later this year.

“We made it through this Indian holocaust,” said Deborah Parker, chief executive of the Healing Coalition and a member of the Tulalip Tribes. “We made it to a place right now where we can finally talk about this pain and find enough strength to just stand up and say that our lives mattered and the lives of our children mattered.”

The Washington Post talked to four survivors of Indian boarding schools who attended the institutions in the late 1940s and 1950s and are now in their 70s and 80s. Some have never spoken publicly about their experiences, which left them deeply scarred. One 86-year-old Kiowa recounted being sodomized by another student at age 10. A 72-year-old Sioux described being snatched from her first-grade classroom by two strangers in suits and driven to a South Dakota boarding school, with no chance to say goodbye to her family. An Alaska Native man said he spent six years being referred to by a number instead of his tribal name. A Chippewa woman remembers watching her mother cry as she climbed aboard a green bus bound for a school 100 miles from her home. She was 7 years old.

Here are their stories:

Ramona Klein, 76

Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, North Dakota

The large dark-green bus pulled up to the elementary school on the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa reservation in Belcourt, N.D., in 1954.

At 7 years old, Ramona Klein reluctantly climbed aboard. She took a window seat on the side of the bus where she could see her mother standing outside, holding two of her younger siblings by the hand. Her mother wiped away tears.

Klein didn’t fully understand she was headed to the Fort Totten Indian boarding school, 100 miles from her home. Looking back now, she said she believes her mother didn’t want to send her and her seven siblings away but didn’t have any other options.

Living in a small house with no electricity and no running water on the reservation, her parents grew flax and had a small herd of cattle, but nearly lost what little they had as they tried to care for one of her brothers who’d undergone a botched surgery for a broken arm. When she was 10, her father died of a heart attack, leaving her mother with eight children younger than 16.

“There just weren’t any resources to take care of us,” said Klein, a retired educator and mother of two who now serves on the Healing Coalition’s board.

At Fort Totten, Klein and the other kids on the bus were taken into a laundry room, where she was told to sit on a high stool.

“One of the first things they did was cut my long hair that was down my back,” Klein said. With black combs dipped in kerosene, a matron brushed her hair to kill head lice, even though she had none.

“I remember watching my hair fall to the floor,” Klein said, noting that she got the nickname “Butch” because her hair was cut so short.

Her daily routine started at 6 a.m. with making her bunk bed. The covers had to be tight enough so a coin bounced off them. If not, she’d have to redo it. She then had to do “details,” or chores such as cleaning floors and bathrooms.

For meals, she and other young girls were marched to the cafeteria. Boys ate on one side; girls on the other. They weren’t allowed to talk to one another, and she rarely saw her siblings.

Most mornings, they were served burnt toast. Lunch and dinner were often barley soup or mush, a mix of cornmeal and milk. Klein was always hungry, she said. Sometimes, she would smuggle a milk carton and a packet of sugar from the cafeteria, hide it on the windowsill of her room and wait until lights were turned off. She’d pull it out when it was nearly frozen, shake it up and add the sugar.

“That was my first homemade ice cream,” she said.

Only the bigger girls in the upstairs dorm were allowed to watch television, so the younger girls were often bored. “We had no playground with swings, or a slide, a teeter-totter or merry-go-round,” she said. “There were no puzzles, toys or books.”

Klein invented her own games. At night, she’d take a mattress and a blanket, wake up her classmates and pull them around on it in the hallways as if it were a sled. Sometimes they’d ride the mattress down the stairs.

“We’d make sounds and be laughing, and the matron would get up and come,” Klein said. She’d bring out a broom and what was called the “board of education,” a paddle with holes at one end. Klein said she’d be told to kneel on the broom handle and then she’d be whacked several times with the paddle.

“She would hit me so bad, I’d have bruises on me. … All on my back and buttocks,” Klein said. “I remember thinking, ‘You’re not going to get the best of me,’ and I refused to cry.”

In class, she said, teachers repeatedly told her “Indians can’t learn” or “Indians aren’t smart.” Often, she was ordered to sit in the corner of the classroom and wear a dunce hat, she said.

And then there was the abuse. For two of the four years Klein attended Fort Totten, she said, she was sexually molested by the adult son of one of the school’s matrons — the term used to describe boarding school employees, regardless of whether they were women or men. She still has flashbacks from the sound of keys on a chain, because he would take his mother’s keys and let himself into the girls’ dorm and inappropriately touch her at night while she was supposed to be sleeping.

“He’d have those keys and I could hear them jingling,” she said. “I’d smell that Brylcreem hair cream of his and then … his hands seemed so big.

“No child should ever be touched in the way he touched me.”

She never told her mother about it, didn’t discuss it with anyone until years later in a support and counseling group.

“It’s a lifelong scar,” Klein said. “It’s a lifelong wound.”

Donald Neconie, 86

Kiowa, Oklahoma

Donald Neconie was 10 when an older student at Riverside Indian School in Anadarko, Okla., began attacking him.

The 17-year-old — nicknamed “The Big Guy” — crept into his bunk bed in a dorm room.

“I felt a hand on my mouth, and the next thing I know, he took off my underclothes and molested me,” Neconie said. It happened “almost every night” for years to him and at least three other boys, Neconie said.

“He’d turn us over and bury our heads and do this,” he said.

One night after drinking a bottle of stolen vodka, Neconie and the other boys got up the courage to tell a matron about the abuse. She said she’d “look into it,” Neconie recalled. But later that day, the local sheriff came and got him and the other victims. He took them to a jail, where they were forced to stay the night.

“We ratted on him, and we became the prisoners,” Neconie said. The next day, Neconie and the other boys were taken back to the boarding school in handcuffs.

“That jailing was to teach us and others a lesson — ‘keep your mouth shut,’” Neconie said.

As far as Neconie knows, “The Big Guy” was never charged.

For decades, Neconie used the internet to track the man. In the mid-1990s, he saw him in person at a powwow in Maryland. The man sat at a drum, and the two made eye contact.

“He knew me,” Neconie recalled. “He glanced at me and then never looked at me again.”

His attacker has since died, but the nightmares remain for Neconie.

“Nobody ever talked to us. They never gave us any counseling,” he said. “We held it inside of us, all welled up. Nothing can make it go away.”

It was only about a year ago that he told his wife of 56 years and family about what happened to him at the boarding school, just seven miles from his childhood home.

At age 8, he was sent to Riverside — one of the country’s oldest and largest off-reservation boarding schools — and stayed until he was nearly 20, going home only twice. He describes it as “12 years of hell.”

On occasion, his parents came to visit, but they had to stay in their car with the windows rolled down while he stood on the curb to talk to them. No gifts or money could be given.

“We couldn’t go toward them,” Neconie said. “We couldn’t go near them.”

Three of his 10 siblings also went to boarding schools, and he was the only one who graduated. He served in the Marines, then worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs as a tribal claims office clerk and later as a specialist for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

When he and his wife were raising their three kids, Neconie said, he was strict with them: “If they got out of line, they’d get a whooping.” He said he inflicted on them “the pain I’d brought from that boarding school. ... I wasn’t always the kindest to my kids. I regret doing that to them.”

When one of Neconie’s sons heard that Haaland, the nation’s first Native American to serve as a Cabinet secretary, was making a trip to Riverside last summer to listen to boarding school survivors, he encouraged his father to go. At first, Neconie wasn’t interested. He’d been back only once and cried as he watched crews tear down an old dorm where he’d once lived with other Kiowas and boys from the Navajo and Hopi tribes.

Eventually, he changed his mind and testified at the school, which remains open but now champions Indian culture.

“It may be good now, but it wasn’t back then,” Neconie told Haaland. “We were sodomized. ... And people knew that was going on and did nothing to stop it.”

He believes that Indian boarding school survivors should get not just an apology but reparations, like those given to Japanese Americans for their incarceration during World War II.

“I didn’t think I was an animal,” Neconie said, “but they treated us like we were. … Nothing could ever make me forget — or forgive — what they did to us.”

Jim LaBelle, 76

Iñupiaq, Alaska

The social workers arrived at the family’s one-room shack in Fairbanks, Alaska, in 1955 and gave Jim LaBelle’s mom a stark choice: give up her two boys for adoption or send them to an Indian boarding school.

At the time, she was newly widowed and struggling to feed her sons, who sometimes scavenged with her for something to eat at the edge of the local dump. She was also an alcoholic, LaBelle said.

LaBelle, then 8, and his younger brother, then 6, were sent to the Wrangell Institute, about 700 miles from their home. His mother was in tears, he said, and “kept apologizing.”

“She said, ‘You’re going to have to go away for a while,’” he said. “We got that it was some kind of school, but we didn’t know where or how far or how long we’d be there.” LaBelle stayed at Wrangell for six years and then spent four years at a second boarding school in Alaska.

He remembers, on that first night at Wrangell, how one boy started quietly crying and then others joined him. “You’d hear some crying out ‘Mama, mama.’ But no mama came.”

LaBelle, whose Iñupiaq name is Aqpaiuq, which means “fast runner,” was fluent in his language when he left home, but after he saw other students being slapped and shaken when they were given commands in English they couldn’t understand, he learned to keep quiet.

Like the other children, he was assigned a number every year he was at Wrangell, and can still recall them: 71, 68, 57, 52, 51, 64. “One boy who didn’t know any English when he came,” LaBelle said, “thought his number was his name.”

During his first few weeks at the boarding school, LaBelle said, he and many of his bunkmates got sick from the salted meats and cans of processed vegetables and powdered milk they were served instead of their traditional diets of walrus, seal, moose, salmon, wild potatoes, celery and blackberries. Often, he said, they were given huge portions of food and forced to clean their plates.

“Our stomachs would be cramping. We’d have headaches and vomit and soil the beds and our clothes,” he said. “The matrons would get pissed off and beat us for getting sick.”

The kids were disciplined for talking back, not paying attention, not following orders, or giving the wrong answers in class. He’d get demerits for no reason, he remembers.

“I didn’t even know what I’d done wrong sometimes,” he said, “and I’d be punished.”

The punishment he feared most was known as “going through the gantlet.” Kids were forced to undress, then run up and down between other kids who stood in two lines with belts.

“The matrons would tell the other kids to use them on us,” he said. “There’d be 15 or 20 kids on each side hitting us as we ran.”

On occasion, LaBelle said, he was told to go to the blackboard at the front of a classroom to do a math problem. He said he was so scared of getting it wrong, he froze. The teacher, he said, would yell at him, “You’re wasting my time.”

“He’d give me these stares of anger, meanness and just disgust,” LaBelle said.

He was told by some matrons that his mom was evil for practicing her traditional Native ways of singing, drumming and dancing. When he went home in the summers, he said, he would be so ashamed of being seen in public with his mom that he’d ignore her.

LaBelle, a Navy veteran and father of four who worked in the oil and gas industry and for state government, became a professor of Native studies at the University of Alaska Anchorage. He now serves as president of the Healing Coalition, which is pushing Congress to create a commission to investigate the way the schools operated, examine church and government records of the schools and identify where children were buried.

He will always live with what he endured at boarding school, he said. He watched as a 12-year-old friend was punched so hard by a matron for “mouthing off” that he was left unconscious and had to be taken to a hospital.

“When he came back, his mouth and jaw were wired shut,” LaBelle remembered, “and he had to eat and drink through a straw.” The matron was never reprimanded. “It was a reminder,” LaBelle said, “what they could get away with.”

“I developed this fantasy of getting back at him for years,” he said of the matron. Later, he would look at obituaries to see if the matron had died. “I never forgot him or his face,” LaBelle said, “or what he did to my friend.”

Dora Brought Plenty, 72

Standing Rock Sioux, South Dakota

The two men in black suits and ties arrived with no warning.

Dora Brought Plenty, orphaned at 4 when her mother was murdered, had been living with her grandparents on the Standing Rock Sioux reservation in South Dakota and attending a nearby day school. Then one day in 1956, the two White men showed up in her classroom and spoke to her teacher.

“She pointed at me,” remembered Brought Plenty, whose mother was from the Standing Rock Sioux Turtle Clan and also Canadian Assiniboine and whose father was Black and of the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe. “They came toward me, grabbed me by my little arms, jerked me up out from the desk, out the door, to a black car.”

She was 6½ years old and too terrified to ask who they were or where they were taking her. She had no chance to say goodbye to her grandparents, she said, and never saw her grandfather again. The men drove her to the Pierre Indian School, nearly 200 miles from her home.

Once there, she was told to climb up on a stool. A matron “jerked my head back and cut off my braids,” Brought Plenty said. “I remember seeing them hit the floor.”

When she asked for her clothes, a matron told her, “We’re going to teach you.” She took her to a dark basement in just her undershirt and panties and left. Hours passed before another matron came, took her to her dorm, threw a nightgown at her and ordered her to bed.

The next day, she got the school’s uniform — a white shirt with a Peter Pan collar, pedal pusher pants and saddle shoes. She was taken to church and asked if she was Catholic or Episcopal. When she said she thought they were the same, they put a metal cross in her hand, told her she’d be Episcopal and said she should “go pray for forgiveness for who you are.”

Brought Plenty became known by her assigned number — 199. When she whispered in Lakota to another classmate, a teacher told her to put out her hands and smacked her knuckles with a ruler. Another frequent punishment: She was taken to a hallway, where she was told to kneel and stretch out her arms with her palms up. Bricks were put in each hand and she was left in that position for hours.

“They beat me so bad at times, threatening that when they finished with me,” she said, “I’d never remember a word of my Indian language.”

She thought about running away during her 4½ years at Pierre, which is now tribally run with classes on Native culture and history. Escape seemed impossible, she said, because she didn’t know what direction her home was in.

In second grade, one of her friends, Lucy, did run away with another girl. They were caught and brought back. After they returned, a matron rang a bell. She ordered all the girls in Brought Plenty’s dorm to get out of bed. Get hand towels, she told them, and go to the washroom. Wet the towel with hot water, don’t wring it out, and stick open safety pins in it. Form two lines, she told them, and as the runaways walked by naked, smack them with the hot towels and pins.

“When Lucy got to me she looked at me, eye-to-eye,” Brought Plenty said. “I couldn’t hit her. She was my friend. I just stared at her.” A matron grabbed Brought Plenty, ripped off her nightgown and pushed her into the gantlet. The other girls hit her.

“It was horrible,” Brought Plenty said. “I think I was in shock.”

She didn’t see Lucy again.

In class, Brought Plenty would draw trees, the Black Hills and animals as a way, she said, “to get my mind away.” But sometimes she’d be caught, and her creations would be crumpled up and thrown away. Then her artwork impressed one teacher, who asked her to draw pictures of fish and other animals that were used in science classes.

“I figured out what they liked and realized I wasn’t going to get hit if I did what they liked,” she said. “I quickly realized at a young age that my art could save me.”

She was chosen for piano lessons, but had to fight with other girls to practice at the one piano, Brought Plenty said. All of them scrubbed floors, sometimes with bleach and a toothbrush, and wiped down walls or shined chrome counters, earning “spare time” to play jacks or basketball or to go skating. Brought Plenty stayed at Pierre until she was in the fifth grade.

For years, Brought Plenty, who went on to work as an HIV educator, teach art and library sciences at elementary schools in the Dallas area and raise four children, struggled with bouts of depression. Sometimes she punished herself by isolating from her family. She stopped showering — a flashback to years at Pierre when matrons stood in the shower area. “They’d jerk back the curtains,” she said, “to look at you and call you names.”

“They’d call us ‘you damn dirty Indians’ and only allow us to shower once a week,” she recalled.

Brought Plenty tried to get help. At 13, she went to a doctor and told him she wanted to hurt herself. “He told me, ‘That’s nonsense,’” she recalled. At 16, she started cutting herself — a coping habit that continued off and on into her late 50s. At 21, a psychiatrist prescribed Valium that left her feeling “zoned out.” She said she attempted suicide three times.

About eight months ago, Brought Plenty started to draw and paint to show her experiences at boarding school. In one of her pictures, a young Indian girl runs as a nun chases her. The girl is her, and she’s wearing a white shirt with a Peter Pan collar just like the one Brought Plenty wore at boarding school.

“Artwork,” she said, “allows me to heal. It’s my freedom.”

READ MORE  A grizzly sow and cubs forage along Obsidian Creek in Yellowstone National Park. (photo: Jacob W. Frank/National Park Service)

A grizzly sow and cubs forage along Obsidian Creek in Yellowstone National Park. (photo: Jacob W. Frank/National Park Service)

The latest data shows the population of grizzly bears in and around the park at 965. That's more than quadruple the number that existed when they were first protected by the Endangered Species Act in 1975.

Despite their fearsome reputation, though, grizzly bears would rather avoid people than attack them. By the numbers, visitors to the heart of grizzly country in Yellowstone National Park have about the same likelihood of being killed by a falling tree as being killed by a grizzly.

That's despite a lot more people in the area. A record 5 million people visited Yellowstone National Park in 2021. Even more frequent the surrounding mountains and forests. In that enormous region, the animals have killed a total of 10 people since 2010.

"When you think of that, and you combine that with a population of almost a thousand grizzly bears, it is actually remarkable that there are so few serious incidents," said Frank van Manen, who leads the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team. He said attacks are still so rare that statistically, the data doesn't show any kind of an upward trend at all. His group of federal, state, and tribal biologists has documented how the growing number of grizzlies has expanded into territory that's three times larger today than it was 50 years ago. That's only been possible because people who live here have been willing to learn and adapt.

"It's totally possible for people and bears to coexist on the landscape," van Manen said. "I think in the greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, we have shown that that is the case."

Human responsibility

For rancher and retired educator Hannibal Anderson, coexistence is part of daily life. "It's the human responsibility to figure out where the risks are," he said.

He lives about 30 miles northeast of where the hiker was attacked and killed, and he's walking to where bears have been grazing on his ranch just outside Yellowstone National Park. He says a sow and her cub have been here just about every night. He points to an area where bears have clawed away dirt, almost like tilling the soil, to get at the roots of a non-native plant called caraway that flourishes in the area. The bare patch of earth is a stark contrast to the lush, green grass extending to the jagged peaks above.

Anderson's family moved here in the 1950s. Growing up, he says grizzlies weren't much of a concern. But starting in the 2000s, as other food sources like Whitebark pine declined, grizzlies showed up in droves, searching for that tasty caraway. Grizzlies are ordinarily solitary creatures. But at the right time of day, at the right time of year, he says 15 or more grizzlies could be grazing within sight.

Walking back to his barn, he bumped into Ellery Vincent, a range rider. It's her job to spend time with Anderson's cattle herds. Riders can help fend off bears, and also help just to perceive what's going on across the landscape. Today, she saw something potentially alarming.

She says she got a funny feeling as she was riding. Not long after, "I saw the runny scat and then all the birds everywhere." She had a hunch that might indicate that a grizzly's killed one of their calves.

Anderson says they've lost cows before. But not many. "Not enough to raise alarms with regard to the number of bears," he said.

But he does recognize their negative impacts. All the digging creates conditions ripe for unwanted plants to colonize. He's never personally had a scary encounter, but he's acutely aware that grizzlies have attacked elk hunters nearby. Even walking out the back door at night these days is an exercise in caution.

In response, Anderson's family has changed the way it ranches. In addition to employing range riders like Vincent, they raise slightly older, larger cows, keep them close together to activate their herd instincts, and move them to different places at different times. All that makes them harder for grizzlies to kill. It's a lot more work. But he sees it as a deeper alignment with his belief system.

"I don't see the world as a place where humans just get to trump everything else," he said. "I consider it a really fundamental responsibility of being human to serve the ecological integrity of wherever we live."

For Anderson, grizzlies and other predators, like wolves, are a crucial part of that ecological system.

But most elected leaders in the states surrounding Yellowstone don't see it that way. They say people have done enough adapting to bears and it's time to "delist" them, or remove federal endangered species protections. After last month's attack, two Montana congressmen tweeted exactly that. They suggested state management could reduce grizzly numbers and potentially prevent tragedies like that one.

Grizzly biologist Frank van Manen says there are a number of bureaucratic hurdles to clear in order for delisting to occur. But he said the Endangered Species Act was created to recover populations and then remove protections when they're no longer needed. Today, he said the population is well over the target numbers set by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. He added that the data shows a striking trend recently. That rapid growth of both population and range has slowed down in recent years. The population, he says, is starting to regulate itself.

"From a biology or an ecology standpoint, recovery to me means bringing a population back to what the habitat supports and that's basically where we are right now," he said.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has removed protection for Yellowstone-area grizzlies twice since 2007. Bear advocates sued, and courts overturned both attempts at delisting. But this year, the agency launched a new analysis on grizzly recovery for bears in and around both Yellowstone and Glacier national parks. Politicians from the region have introduced legislation to delist through Congress, too.

A little north of rancher Hannibal Anderson's property, a coalition of hunting groups has erected a billboard that reads: "Delist grizzly bears to support a conservation success story."

Anderson says delisting wouldn't make much of a difference in what goes on on his ranch. But he's heard both sides of the debate go at it for years.

"I'm not sure one or the other is particularly right or wrong," he said. "The bigger question to me is: what kind of relationship do the humans, wherever they are, want to have with the grizzly bear?"

So whatever happens, Anderson will keep putting his values into practice, trying to create a landscape that nourishes both people and bears.

"It's a lot easier said than done, I understand."

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.