Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

After eighty years, the site of a mass execution of Jews was about to be commemorated. Then Putin launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

On the afternoon of September 24th, there were explosions along Khreschyatyk, Kyiv’s central avenue, which continued for four days and set off a massive fire. Before retreating, the Soviets had mined the city. An area the size of Manhattan’s financial district was decimated; the rubble of destroyed buildings rendered streets unrecognizable and impassable. The ruins smoldered for weeks. The number of victims of the blasts and fires is unknown, but likely included more Ukrainian civilians than German troops.

On September 28th, the Germans papered the city with flyers instructing “all Jews of the city of Kyiv and its environs” to report to the corner of Melnikova and Dehtiarivska Streets, on the outskirts of town, by eight the following morning. They were to bring “documents, money, valuables, warm clothing, linens, etc.” The notices were unambiguous: “Those Jews who do not carry out this order and are found elsewhere will be shot dead.” The gathering place was near two cemeteries—one Russian, the other Jewish—and a railroad station. Many people assumed that the Jews of Kyiv were being deported, probably in retribution for the mining of the city.

More than two hundred and twenty-four thousand Jews lived in Kyiv before the war, according to a 1939 census. Many Jewish men and women joined the Red Army; others, who had connections or decent jobs, evacuated before the Germans entered the city. Some who remained disobeyed the order and went into hiding. Those who did report to the corner of Melnikova and Dehtiarivska Streets as instructed were, for the most part, the poor, the sick, the very young, and the elderly. German soldiers beat them with sticks, confiscated their belongings, and marched them to the edge of a deep ravine called Babyn Yar, where they were stripped naked and shot. Thirty-three thousand seven hundred and seventy-one Jews were murdered at Babyn Yar in thirty-six hours. This was among the first acts of mass murder of Jews during the Second World War, and it remained the biggest single mass execution of the Holocaust. After the massacre, the Germans continued to use the ravine as an execution site for Jews, Roma, the mentally ill, and others. In 1942, Germany established a P.O.W. camp next to Babyn Yar. When Soviet troops were poised to retake the city, in 1943, German soldiers ordered the inmates to remove bodies from the ravine and burn them.

After reclaiming Kyiv, Soviet authorities gave a group of foreign journalists a tour of Babyn Yar. The footage of that tour, along with pictures taken earlier by a Nazi photographer and a number of photos taken by a special Soviet state commission which were kept secret for seventy years, made up the visual record from the time. In 1946, while the Nuremberg trials were under way, a court in Kyiv tried fifteen German officers who had committed atrocities in Ukraine. Several witnesses and survivors testified. The court sentenced twelve of the defendants to death; they were hanged in the city’s central square, now known as Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square. But following those executions the Soviet Union banned any public discussion of what had happened to Kyiv’s Jews.

Babyn Yar was more than forty yards deep and stretched the length of several city blocks. Soviet authorities decided to fill it in by directing wastewater mixed with clay from nearby brickmaking plants to the ravine. In the early nineteen-fifties, a dam was constructed to contain the flow, turning the ravine into a murky lake. On March 13, 1961, the dam burst. The ensuing mudslide killed hundreds of people; their remains mixed with the bones of those who had been shot by the Germans.

For forty-five years after the end of the Second World War, the Soviet Union censored all documentation of the Holocaust, including any attempt to memorialize Babyn Yar. Even after the collapse of the U.S.S.R., twenty-five more years passed before a comprehensive memorial effort began. Then came a new war in Europe––Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

German forces carried out thousands of mass shootings of Jews in Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, western Russia, and the eastern territories of Poland, in what has become known as the Holocaust by bullets. German soldiers and police, as well as contingents of local collaborators, murdered more than two million Jews. For decades following the war, none of the killing sites were marked as places of Jewish extermination. A group of Soviet Jewish writers––including Vasily Grossman, Margarita Aliger, and Ilya Ehrenburg––assembled a compendium of testimony and documents, but censors banned its publication. According to Soviet historiography, the Nazis had targeted all Soviet citizens equally. “If you emphasized Jewish losses, you were a bourgeois nationalist,” Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, a professor of Jewish studies and history at Northwestern University, who grew up in Kyiv, told me.

In 1961, during a brief period of tentative liberalization known as the Thaw, Yevgeny Yevtushenko wrote a poem that began, “No monument stands over Babi Yar.” (Babi Yar is the Russian-language name of the ravine.) Yevtushenko became famous in the West for his courage in writing about a taboo subject. People outside Kyiv learned the name Babi Yar. But the obliteration of the site continued. Following the dam disaster, construction crews filled in the ravine. A new road was built alongside it and a residential neighborhood went up. In 1966, the Times published a dispatch with the headline “Boys of Kiev Play Ball on Babi Yar,” describing young working families who were now able to move “out to the fresh air of the suburbs from their old crowded and dingy apartments.” Not long afterward, the city built a television tower near the grounds and a TV-production center on the site of the old Jewish cemetery.

Yevtushenko was not the only Soviet writer to take on the subject of Babyn Yar. Around 1944, a teen-ager in Kyiv named Anatoly Kuznetsov, who lived near the site, began recording his memories. He ultimately assembled notes, interviews, and documents into a book, “Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel.” It was published in serial, censored form in the journal Yunost (Youth) in 1966, as the Thaw was coming to an end. In 1969, Kuznetsov defected to the U.K. and published the unexpurgated version, including the final lines of his original manuscript, which the censor had cut: “I wonder if we shall ever understand that the most precious thing in this world is a man’s life and his freedom? Or is there still more barbarism ahead? With these questions I think I shall bring this book to an end. I wish you peace.”

The sites of mass shootings in Vilnius, Lithuania; Riga, Latvia; and Kyiv became focal points for Jewish activism. People gathered, or tried to gather, at Babyn Yar every year, beginning in September, 1966, to mark the anniversary of the massacre. From the late sixties to the mid-eighties, at least nine of the commemorations’ organizers were arrested and given prison sentences of a year or longer; many more, including the dissident and future Israeli politician Natan Sharansky, were briefly detained when they attempted to travel to Babyn Yar. Nevertheless, in November, 1966, the Soviet state set down a plaque at the site; it read “A monument will be constructed here to Soviet people who fell victim to fascist crimes committed during the temporary occupation of Kyiv in 1941-1943.” Ten years later, the monument finally appeared: a mess of tangled bodies in struggle, forming a sort of pyramid. The inscription at its base said “Here, in 1941-1943, German fascist occupiers executed more than a hundred thousand citizens of Kyiv and prisoners of war.”

The Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. That year, Babyn Yar got a second monument and its first explicit reference to Jews: a large bronze sculpture of a menorah. More than two dozen markers followed, honoring, among others, Ukrainian nationalists, Jewish resistance fighters, Roma people, and several Ukrainian soccer players who had been gunned down at Babyn Yar after their team defeated a German team. Most of these are figurative sculptures, none of them physically or aesthetically linked to any of the others. In 2000, a metro station opened nearby. Residential development brought commerce: fast-food kiosks, a sports center, and a shooting range.

The quarter century following the Cold War saw the museification of the Holocaust. Cities from Berlin to Warsaw to Washington opened Holocaust museums and memorials. In 2005, Yad Vashem, the Holocaust museum and memorial in Jerusalem, unveiled a large new building. Even Hungary, which has gone to great lengths to obscure its wartime collaboration with Nazi Germany, commissioned a striking memorial: a row of life-size shoes, forged of iron, lining the embankment of the Danube in Budapest where Jews and others had been ordered to remove their shoes before they were shot.

“Holocaust recognition is our contemporary European entry ticket,” the historian Tony Judt wrote in his 2005 book, “Postwar.” “As Europe prepares to leave World War Two behind—as the last memorials are inaugurated, the last surviving combatants and victims honored—the recovered memory of Europe’s dead Jews has become the very definition and guarantee of the continent’s restored humanity.” But, as the last people alive at the time of the Babyn Yar tragedy died, the site continued to be an incoherent space: a city park peppered with sculptural markers that meant little to most visitors.

In 2014, thousands of Ukrainians who were angry with their pro-Russian government protested for months in Kyiv’s Independence Square, in what became known as the Euromaidan or the Revolution of Dignity. The President, Viktor Yanukovych, fled to Russia. Petro Poroshenko, a businessman and a former foreign minister, won the next election; his mandate was to establish closer connections with Europe.

In 2016, the Ukrainian government organized a major commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Babyn Yar massacre. To become a European capital, it seemed, Kyiv had to memorialize its own landscape of the Holocaust. In late September, the words “Babyn Yar” could be seen on banners throughout Kyiv. The historian Timothy Snyder, whose book “Black Earth” provides an account of the Holocaust by bullets, came to Kyiv at the invitation of the government, delivered a public lecture on Babyn Yar, and appeared on seemingly every talk show. Poroshenko announced that a museum and memorial complex would be built in time for the eightieth anniversary of the massacre. The project would be underwritten by a group of wealthy Jewish Ukrainian-born businessmen: Mikhail Fridman, Pavel Fuks, German Khan, and Victor Pinchuk.

Most Holocaust memorials are public enterprises. The Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center was welcomed by the Ukrainian state, but it was a private undertaking that reflected the ambitions and desires of its backers. Fridman is a co-founder of Alfa Bank, Russia’s largest private bank; his net worth is estimated at around eleven billion dollars. In September, Fridman told me that Fuks, a developer, had called him to say that he was eyeing a plot of land near Babyn Yar and was thinking of establishing a museum there. Fuks had made his first millions in Russia; in 2014, he embarked on significant investments in Ukraine. Fridman brought in his business partner, Khan, who had made his fortune in energy, and Pinchuk, a Ukrainian businessman with interests in everything from steel to media. (In 2021, Fuks abandoned the project after he was accused by the Ukrainian government of having engaged in corrupt business practices, an allegation he denies.)

During the next couple of years, a team of researchers, curators, and architects developed plans for a project in the mold of other European Holocaust memorials: self-contained, respectful of the landscape and the life that had taken root there since the war. But the funders aspired to something more spectacular. In 2019, they put together a high-profile supervisory board that included Sharansky; Svetlana Alexievich, a winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature; and the president of the World Jewish Congress, Ronald Lauder.

To lead the project, the funders invited the Russian Jewish filmmaker Ilya Khrzhanovsky, who they knew could create on a grand scale. In 2005, he had begun a monumental film project, “Dau,” about the Nobel Prize-winning Soviet physicist Lev Landau. Khrzhanovsky had constructed an immense set in Kharkiv that conjured an entire world of the Soviet nineteen-forties and fifties: the apartments, furniture, appliances, clothes, and foodstuffs, as well as the paranoia, surveillance, and arrests. A rotating cast of nonprofessional actors took on assigned identities and inhabited them—and the period world—around the clock. The project ran in Kharkiv for five years, and Khrzhanovsky still hasn’t finished editing all the footage. In January, 2019, twelve feature films were screened as a single installation in Paris, followed by a two-film screening at the Berlin International Film Festival. Some other screenings were derailed by allegations of violence and exploitation on the set.

Khrzhanovsky’s central subject is humankind’s capacity for evil. “Dau” was a years-long Milgram experiment, and all of the resulting films portray people’s relationships to the allure and the threat of overwhelming authority. One of the lead amateur actors in the project was a Ukrainian former prison official; a small part went to a real-life Russian neo-Nazi, who played himself. Between 2015 and 2020, while he was editing “Dau,” Khrzhanovsky, who lives primarily in London, also created an installation in a building in Piccadilly—a kind of totalitarian house of horrors, featuring ghouls in Soviet secret-police uniforms. It doubled as a drinking club that brought together artists, writers, and billionaires, including Fridman and Pinchuk. Khrzhanovsky’s ambitions matched those of his funders: Europe’s last Holocaust memorial—whatever it became—would be its greatest.

Khrzhanovsky is forty-six, plump, boyish, and soft-spoken. He dresses in generously cut black suits and black trench coats that faintly suggest a visitor from the mid-twentieth century. I’ve talked to him several times in the past two years, in different cities. Last year, in Moscow and in Kyiv, we spent many hours discussing Babyn Yar and the talented people—both illustrious artists and newcomers—whom he had drawn into the project. But whenever I asked why one particular choice or another had been made, Khrzhanovsky replied, “Because that’s what is needed here.” I didn’t read this as evasion so much as a summing-up of his approach to art: make a world, populate it, and see what happens.

The offices of the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center are two large apartments on two floors of a building in Kyiv. Furniture, light fixtures, books, wall art, and even the dishes in the office kitchen were chosen to match the object of study. Without waiting for the new museum to be constructed, staff members had started to build what became a giant collection of artifacts and documents that might have belonged to Ukrainian Jews before the war. They scoured antique shops and online auctions; they bought entire family archives and trunks full of unsorted photographs and mementos. They were trying to compile a complete list of the Jews who lived in Ukraine before the massacre, and an accurate list of everyone who died at Babyn Yar.

Oleh Shovenko, the project’s deputy artistic director, told me that, in an antique store in Lviv, he found a chandelier from a synagogue that had been destroyed. Through an online shop hawking Nazi memorabilia, he bought an album of photographs of a German officer who posed at sites in various European cities and next to the bodies of murdered Jews. Shovenko dressed in vaguely nineteen-forties fashion and wore his wispy dirty-blond hair thrown back; he looked like every boy in my grandmothers’ black-and-white university pictures, taken just before they went off to fight in the Second World War. Shovenko had uncannily bright blue eyes. He told me that he wasn’t sure what the goal of the project’s huge collection was, but it had something to do with “understanding.”

“It’s like I can see a headline, ‘How could people kill thirty-four thousand other humans in the space of two days?’ ” he said. “I guess I’ve learned that social progress is like a house of cards. If you have no running water, no heat, and no electricity, it’s easy to spread xenophobia.”

Anna Furman, a deputy director who ran the Names Initiative, told me about creating what she described as “already the largest digital archive in Ukraine and, maybe, soon to be the largest in Europe.” Her job was to interview witnesses and survivors of the massacre and their descendants and to cross-check available testimony and archival documents, restoring a usable past for the city of Kyiv and for the families of the victims. “One person had the wrong name of his great-grandfather,” she said. “We found the correct name and address, and he told us, ‘Now when I walk down that street, I look in a different set of windows.’ ” The researchers were gradually filling in the list of people shot at Babyn Yar and supplementing it with the names of victims who died on the way to the ravine, or who didn’t make the journey. They found that some people, and entire families, had committed suicide rather than go to the killing site.

Over dinner by candlelight in the office, Maksym Rokmaniko, a thirty-year-old architect, told me about the reconstruction of the massacre site. Using techniques developed by the Israeli British architect Eyal Weizman, Rokmaniko’s group had created three-dimensional models based on the few available photographs. Rokmaniko pulled a new rendering up on his tablet. It showed piles of naked bodies—the perfect bodies of young men, as though drawn from Greek statues. “That needs to be adjusted,” Khrzhanovsky said. “It was mostly women, children, and old people.”

At the end of their workday, around eleven in the evening, as Sinead O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” played on a replica of a nineteen-thirties phonograph, I talked with Furman and several other staffers, all women, about what they had known of Babyn Yar before taking jobs at the memorial center. Dasha Dzhuromska, who was twenty-five, said that she didn’t learn of its history until after she finished high school. “We had nothing about it in school,” Kaleria Kozinets, the staff cook, said. She was forty-nine and Jewish. “When I told my father where I was working, he told me that my grandfather Ilya was there as a boy and survived because some man covered him with his body.” Kozinets had never heard this story. About twenty-five people are believed to have survived the massacre.

“Every time I go to Babyn Yar, I can’t stop thinking about the thirty-four thousand in two days,” Valeria Didenko, who was twenty-one and who worked as Khrzhanovsky’s assistant, said. “When Maksym showed us his model, it had only nine thousand bodies visible in it, and I thought, What’s thirty-four thousand like?”

They fell quiet. In six months, bombs began to fall on Kyiv again. In Kharkiv, Mariupol, Kherson, and other cities, people struggled to survive without heat or running water, and with dwindling supplies of food. Millions of refugees, almost all of them women and children, streamed into Europe. Bodies piled up in bombed-out buildings and in the streets. The dead numbered in the many thousands. In the first days of April, when Russian troops retreated from the suburbs of Kyiv, they left behind mass graves; streets strewn with bodies of civilians with their hands tied behind their backs, executed at close range; and bodies they had attempted to burn. None of this had been imaginable, much as the carnage of Babyn Yar was unimaginable.

The conversation turned to 2014, when more than a hundred Ukrainian protesters were shot as they rallied at Independence Square. Not long after, Russia occupied Crimea and fomented a war in the Donbas. Dzhuromska’s family lost their income because of the war and she had to quit university in Poland after one semester. Didenko spoke of the fracture of her mother’s family, which came from Donetsk, in the east: one uncle joined the Euromaidan and supported the Ukrainian Army while another declared himself Russian. Furman talked about seeing the dead bodies in Independence Square. “You ask how it’s possible to execute so many people in two days,” she said. “The thing is, it’s possible for people to execute people.” Furman and her colleagues weren’t comparing their hardships to the Holocaust. They were talking through the way life as you know it can end overnight.

When I visited Babyn Yar, it was close to the eightieth anniversary of the massacre, but the memorial complex that Poroshenko had promised five years earlier was not ready. Khrzhanovsky led me on a late-night tour. At an entrance to the park, we walked down a gravel path to an installation called the Mirror Field. The first thing I noticed was a howling sound—it seemed to come from the nearby road, and the structure, an elevated round mirrored platform with ten mirrored columns protruding upward from it, was amplifying the sound. (An electroacoustic organ is hidden in the installation’s base, augmenting ambient noise.) Then there was a crackling and, finally, a woman’s voice, saying the names of the dead.

“When you look here, you see yourself shot,” Khrzhanovsky said.

“What do you mean, you see yourself shot?” I asked. I wasn’t sure whether I was meant to look down into the mirror at my feet or straight ahead at one of the columns. Everything was riddled with holes, as though bullets had ripped through metal.

“You see yourself with holes,” Khrzhanovsky said. “Come, stand here.” He went on to explain that the holes matched the calibre of the bullets used by the executioners, and that the low-grade background hum matched frequencies that involved the numerical expression of the letters that made up the names of the dead. I couldn’t follow the explanation, and wasn’t convinced that Khrzhanovsky understood it, either.

Our footsteps on the mirrored platform made the sound of breaking glass. I have visited most Holocaust monuments and memorials in Europe: the small ones and the big ones, the elegant ones and the inept ones. I had tried to keep an open mind on my way to Babyn Yar, but the ride, in a luxury car, and Khrzhanovsky’s boastful tour had made this difficult. Now, though, I found myself moved. This monument was unlike any other: it was constructed of light, temporary material; it pulled you in without telling you exactly what to think; and it made you feel alone in a fragile, crackling, howling, grieving world. The woman’s voice was now replaced with that of a cantor in prayer.

Khrzhanovsky led me a short distance away from the mirrored platform and pointed to a boulder with a tiny viewfinder in it. I saw a rotating gallery of prewar photographs of some of the dead. We walked into an alley that runs along the edge of the park, and I heard something new: the sound of prayer had faded, and a woman’s voice, half whispering, said a name, then another. I now noticed that a speaker was mounted on every lamppost along the alley.

The next day, I went to Babyn Yar again, without Khrzhanovsky. I rented an electric scooter and rode around the park. Somehow, amid the young families with baby strollers and the teen-agers hanging out after school, the effect of the audio installations was more striking. In the alley, I felt that I kept overhearing names said just over my shoulder. Where once there had been silence, now you could hardly come to this park without being reminded of the massacre. It was like walking around Berlin, where the eye is always happening upon reminders of the Second World War: an information stand telling you that this was the site of Hitler’s bunker, or the Stolpersteine—the “stumbling stones” inlaid in sidewalks in front of the last residences of Holocaust victims.

Khrzhanovsky told me that he planned to create fifteen museums: of the Babyn Yar massacre itself, of the Holocaust in Ukraine and Eastern Europe, of local history, of the lost world of Ukrainian Jews, of the 1961 mudslide catastrophe, of the history of oblivion, and some others—he trailed off. More than half a dozen permanent installations had already been completed at the Babyn Yar site, including a tiny but fully functional wooden synagogue, designed by the Swiss architect Manuel Herz, built to open like a giant crank-operated pop-up book. The most controversial installation was Marina Abramović’s “Crystal Wall of Crying,” made of local coal interspersed with large, protruding crystals, a work that makes clear yet awkward reference to the Western Wall, in Jerusalem. In her artist’s statement, Abramović proposed that visitors lean against the wall and meditate on the tragedy of Babyn Yar. The crystals were positioned to align with the faces, chests, and bellies of people of different heights. The wall was ostentatious and tone-deaf, unlike her best work. It gave Khrzhanovsky’s detractors a symbol of how the over-all project at Babyn Yar had gone pretentiously off the rails.

“That wall is beyond critique,” Petrovsky-Shtern, the Northwestern history professor, said. “Whatever is done there needs to be modest, a noninvasive way of connecting all these sorrows.”

The difference between Khrzhanovsky’s showy approach and more conventional ways of memorializing the Holocaust goes beyond issues of dignity and taste. The primary purpose of most Holocaust memorials is to document the names and the fates of the victims, the customs and the traditions of the lost world, and to convey the scale of the tragedy. For Khrzhanovsky, this is only a part of the project. Early in his time in Kyiv, he shared a slide presentation with his staff and investors which leaked to Ukrainian media. It included references to building a labyrinth of narrow dark corridors with an interactive exhibit; it would be enhanced by facial-recognition technology that would chart a “separate path” for every visitor. The ideas were not wholly unrelated to existing Holocaust memorials: the main exhibit space of Yad Vashem is built to feel claustrophobic; the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, in Berlin, features rows of hundreds of concrete slabs that lean in, creating a narrowing and darkening path; and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, in Washington, D.C., encourages its youngest visitors to identify with a composite character named Daniel. But Khrzhanovsky’s leaked presentation gave rise to fears that he was going to create some kind of Holocaust theme park. (He later explained that the presentation contained results of a brainstorming session, and not anything near the final blueprint.)

Khrzhanovsky collaborated with Patrick Desbois, a French Catholic priest whose title at Georgetown University is professor of the practice of the forensic study of the Holocaust. Desbois, who wrote the book “The Holocaust by Bullets,” led the scientific committee for the Babyn Yar project, which he called a “historical and anthropological revolution”—the first museum to mark the site of a genocidal massacre. “Normally, we build countries on mass graves,” he told me over Zoom from Georgetown. “Where is the museum of the mass graves in Darfur? Who is going to visit the museum of the destruction of Native Americans in Costa Rica?”

Desbois shared Khrzhanovsky’s commitment to re-creating the context and the circumstances of the Babyn Yar massacre in every possible detail, including the inhabitants of what Primo Levi called the “gray zone”—the unwilling or unthinking assistants to the perpetrators. (Desbois found testimony from a man who had delivered sandwiches to the executioners.) Most of all, Desbois wanted to identify all the perpetrators: “The victims were not killed by a storm or a tsunami. Every one of them was shot by someone.” The hangings of some of the executioners, in Kyiv in 1946, were followed by a few other trials and punishments. In 1951, Paul Blobel, who had directed the mass executions in Ukraine, was hanged in Germany. Eleven more executioners were tried in Germany in 1967; they had long since returned to civilian life—one worked as a salesman and another as a bank director. A fourth trial, of three men, occurred in 1971. But most of the Babyn Yar executioners never faced justice.

“I want to reëstablish the responsibility of humans for mass crimes,” Desbois said. Unlike the annihilation of millions in death camps, mass murder by bullets still happens all the time, and usually goes unpunished.

When I told acquaintances in Kyiv that I was writing about the project at Babyn Yar, they sighed, rolled their eyes, or laughed uncomfortably. No one, it seemed, trusted the project—partly because it was privately funded, partly because it was directed by Khrzhanovsky, but most of all because of Russia. The project’s most outspoken opponent was Josef Zissels, a seventy-five-year-old former dissident and a leader of Ukraine’s Jewish community. I met with him in January at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, one of Ukraine’s largest and oldest universities, where he runs the Jewish-studies center. His primary objection to the project, he said, came from the sense that Putin and his imperial agenda were the forces behind it. Although all four of the rich men who were bankrolling the memorial were Jews who were born in Ukraine, they had benefitted from their connections to Russia, and three of them had carried Russian passports at some point. “It’s hybrid warfare,” Zissels said. “They are trying to foist memory that’s not our memory.”

He talked about what Ukrainians and some Russians call pobedobesiye (literally, “victory mania”), which forms the foundational historical myth and the central public ritual of Putin’s Russia. Every year, the Soviet victory in the Second World War is celebrated with greater fanfare and bigger fireworks, military parades, and reënactments. For months leading up to May 9th, when the country celebrates Victory Day, Russians wear orange-and-black commemorative ribbons on their clothes and bags. The especially zealous decorate their vehicles with slogans such as “Onward to Berlin” or “1941-1945. We could do it again.” One popular decal features two stick figures in the act of anal intercourse; the top has a hammer and sickle for a head, the bottom a swastika.

The Russian memory project is explicitly anti-Western. What the world calls the Second World War, Russia calls the Great Patriotic War. What for most of the world began on September 1, 1939, for Russia started on June 22, 1941, when the non-aggression pact between Hitler and Stalin ended and the war between the two countries began. The U.K., the U.S., France, and many other Allied countries look back on the war with a sense of both tragedy and victory, but the triumphalism in Russia is more pronounced. Now Russian leaders brand real or imagined challengers to their power as Nazis.

Some critics suspected that Khrzhanovsky’s project, in keeping with Russian propaganda that increasingly labelled Ukrainians as Nazis, would focus on local collaborators in war crimes. In 2021, Sergei Loznitsa, one of the best-known Ukrainian directors, made a documentary, “Babi Yar. Context,” under the auspices of the memorial center; other members of the Ukrainian film community charged that the movie was “filled with the narrative accusing . . . the people of Ukraine of collaboration in the mass killings of the Jewish population.” In fact, “Babi Yar. Context,” which employs footage shot by German and Soviet propagandists, does not address the question of collaborators.

I spent many days talking with members of the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center team and combing through the materials they had produced. I encountered occasional pockets of ignorance, primarily on matters of Soviet Jewish history, but didn’t see any indication that the project or its funders were promoting a Russia-centric, much less a Putin-style, narrative. Few on the team had been educated in Russia or had lived there for a significant amount of time. Khrzhanovsky had spent the majority of the past two decades in Kharkiv and London.

Fridman told me, “I expected that we’d encounter resistance, but I never thought we’d be called agents of the Kremlin.” He was born in Lviv. Both of his grandmothers were from Kyiv and had been lucky to leave Ukraine in 1941 with their children. Fridman’s great-grandparents perished in the Holocaust; Fuks, Khan, and Pinchuk had lost relatives, too. At least seven of Khan’s family members were killed at Babyn Yar. (Khrzhanovsky’s maternal grandmother, too, fled Ukraine in 1941.) Sure, the funders of the memorial had made their money in Russia—it was a good place to do business—but they had complicated relationships with the country. Several years ago, Fuks renounced his Russian citizenship.

I asked Zissels what aspects of Khrzhanovsky’s project reflected the Kremlin’s historical narrative. “I can’t prove it,” he said. “But I can feel it.” The apprehension, it seems, was a fear of contagion. The problem with Putin’s revisionist history is not just the centrality of the Soviet Union and Soviet military glory; it’s that, like all Russian propaganda, it intentionally sows chaos. The effect is to produce a preferred historical narrative and a sense of nihilism—a consensus that good and evil are indistinguishable, that nothing is true and everything is possible. This was what made it hard for so many Ukrainians to trust a project funded by people who still did business in Russia. Khrzhanovsky’s avowed obsession with the nature of evil, his willingness to examine it at close range, only fed the distrust.

Putin launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24th. A few days later, Khrzhanovsky was on the phone with Anna Furman, who had been in charge of compiling the list of victims at Babyn Yar. Khrzhanovsky was begging: “Anechka, you know how this goes. Please take your mother and leave.” Furman and her mother ended up going to western Ukraine, as did a few other staff members; still others left for Poland. Shovenko, the artistic director, and Didenko, Khrzhanovsky’s assistant, surprised everyone by announcing that they were getting married. After a small ceremony (Khrzhanovsky attended via Zoom), Didenko went to Lviv, and Shovenko reported for duty with the Ukrainian Army.

Khrzhanovsky used to say, “Babyn Yar is not in the past—it is now.” But he didn’t realize that “now” meant now. He is no longer surprised that so many Ukrainians were suspicious of his work on the memorial. “When I came to Kyiv, I knew that Putin was a scumbag, that the Donbas was at war, that his troops were helping fight it, but I didn’t realize the extent of it, and the Ukrainians did,” he told me from London in March. The memorial center has reoriented itself toward helping Ukrainians flee to safety, starting with Holocaust survivors, other elderly people, and the disabled. “It’s clear that there won’t be a Babyn Yar memorial the way we envisioned it,” Pinchuk told me in late March, from his home in London.

Fridman was one of the super-rich Russians to be sanctioned in response to the war, initially by the European Union and then by the United Kingdom. He complained to the media that the sanctions were unfair, but he resigned from the memorial center. Days later, the E.U. sanctioned Khan, and he, too, resigned. That left Pinchuk. On my computer screen, a month into the war, he still looked and sounded shocked. “This is just beyond, beyond,” he said. “It was impossible to imagine. It’s genocide.” He told me that he was focussing his time and money trying to get military equipment and humanitarian aid to Ukraine.

Desbois’s Ukrainian team of six researchers of mass murder were now interviewing victims and witnesses of new Russian war crimes. By the first week of April, they had completed thirty-seven investigations in Bucha, Mariupol, Irpin, Kherson, and Kharkiv. The day before Desbois and I spoke, the team had interviewed a young Ukrainian man who had been tortured by Russian troops for three days. The Russians had demanded that he confess to being a Nazi.

Putin, in his speech on the eve of the February invasion, called the Ukrainian government—which is led by a Jewish President, Volodymyr Zelensky—one of “radicals and nationalists.” He said that Ukraine had no right to exist as a state and accused it of perpetrating “genocide” against ethnic Russian and Russian-speaking populations. Several passages in the address sounded like warmed-over segments from Hitler’s 1938 Sudetenland speech, delivered in the run-up to Germany’s invasion of Czechoslovakia. Within a few days of Russian troops entering Ukraine, a symbol of the Russian war emerged: the letter “Z,” which first appeared on Russian military vehicles and spread to public transport, official documents, T-shirts, and billboards; it was also painted on the apartment doors of activists and journalists who opposed the war. Russians, in fighting a war of annihilation, had adopted a symbol that looked and functioned like the swastika; Ukrainians were now fighting their own great patriotic war.

On March 20th, Zelensky addressed the Knesset, the Israeli parliament. He invoked the Holocaust and Babyn Yar. “This is a large-scale and treacherous war aimed at destroying our people,” he said. “Destroying our children, our families. Our state. Our cities. Our communities. Our culture. . . . That is why I have the right to this parallel and to this comparison. Our history and your history. Our war for our survival and World War II.” About a week later, speaking over video to leaders of the European Council, Zelensky recited the names of member countries, thanking them for their support. When he got to Hungary, which has refused to send military aid to Ukraine, Zelensky asked Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to visit the Holocaust memorial on the Budapest waterfront: “Look at those shoes. And you will see how mass killings can happen again in today’s world. And that’s what Russia is doing today.”

Petrovsky-Shtern told me, “From a purely historical standpoint, there is no comparison” between the Holocaust and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. “Jews were a stateless nation. No one protected them. Ukrainians are on their own land, protected by landscape, their own army, and growing world opinion.” But, he added, “from the point of view of rhetoric, the comparison makes sense. He is saying, They are coming to erase us.”

When this war is over, Europe will no longer be defined by the history of the Second World War. The next era of European history, whenever it begins, will be the aftermath of the war in Ukraine.

I most recently visited Kyiv at the end of January. For International Holocaust Remembrance Day, on January 27th, the memorial center had originally planned a conference, a ceremony, and the opening of its biggest installation so far, a tumulus-shaped building with Rokmaniko’s models inside. The installation wasn’t finished, and some of the conference events were cancelled. The office seemed in disarray. Several employees had left their jobs. In the library, two young staff members were sorting through newly acquired identity documents for people presumed to have died at Babyn Yar. When Dasha Dzhuromska and I walked in, conversation turned to the center’s plans for safeguarding the collection in case of war, and then to the staffers’ plans for saving themselves and their families. Would they flee? Arm themselves? Learn to drive? A Russian invasion was all anyone talked about, and yet it seemed impossibly unlikely.

European and Ukrainian dignitaries and several Ukrainian rabbis gathered in the tiny synagogue. The interior is intricately painted with prayers, blessings, and a menagerie of animals, all in the colorful style of synagogues in western Ukraine that were destroyed in the Second World War. Vitali Klitschko, the former heavyweight boxer and now the mayor of Kyiv, said, “We stand in a place where innocent people were killed. . . . We are a peaceful nation. We have not attacked anyone. But we will defend our land. And we will especially remember this day.” He spoke in Ukrainian. Moshe Azman, the chief rabbi of the Brodsky Synagogue, in Kyiv, spoke in Russian. “I want to address my words to all the world’s leaders,” he said. “Remember what happened in Babyn Yar. . . . It’s easy to start a war. Let’s all do everything to make sure a war doesn’t start. I pray that the Lord may place righteous thoughts in the minds of all authorities.”

After the speeches ended, the visiting dignitaries piled into vans that took them back to the center of Kyiv. It was snowing heavily. The sky was dark. From a distance, the mirror installation looked like a bottomless pit, the columns like birch trees. I walked down to the reflective field and stood for a few minutes, as the sky started clearing and a hint of blue appeared at my feet. There was no wind, no howl. The names of victims and the prayers sounded in stillness.

I walked away from the installation, past the remains of a soccer goal, into what felt like a half-abandoned industrial zone. It housed a hip coffee shop, the shooting range, and the sports complex. On March 1st, a Russian missile, possibly meant for the television tower, hit near the sports complex. It burned, and four people burned with it. Several people affiliated with Babyn Yar sent me video recordings of the burning bodies. A witness, likely a firefighter, can be heard saying, “So, Russians, who are you fucking fighting? This is a child.” Unlike the last war fought in Ukraine, this one will leave ample visual evidence.

Ukrainians in the eastern city of Kharkiv take shelter in a basement on Sunday. The city, which is close to the Russian border, has been hard hit throughout the Russian invasion. Residents are bracing for a new Russian offensive in the eastern part of Ukraine. (photo: Sergey Bobok/AFP/Getty Images)

Ukrainians in the eastern city of Kharkiv take shelter in a basement on Sunday. The city, which is close to the Russian border, has been hard hit throughout the Russian invasion. Residents are bracing for a new Russian offensive in the eastern part of Ukraine. (photo: Sergey Bobok/AFP/Getty Images)

ALSO SEE: Russia Will Not Pause Military Operation

in Ukraine for Peace Talks

So as the war enters a new phase, what does this mean for both sides?

The advantage of fighting at home

Ukraine has so far made the most of one key asset during times of war — the home-field advantage.

"People are motivated to defend their territory when it's their home turf, more than people are motivated to attack it," said Gideon Rose is with the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of How Wars End.

"You can see that the soldiers and the mercenaries on the Russian side are not particularly motivated, whereas the Ukrainians defending their homes are."

An invading army like Russia has to pack everything it needs — weapons, fuel, food, medical supplies. And Russian troops have been sleeping outside for weeks during the rough Ukrainian winter.

As Russia regroups, it's concentrating forces in eastern Ukraine, just across the border from Russia. That could improve its troubled supply lines.

But Kori Schake at the American Enterprise Institute believes "the Ukrainians will still have big advantages."

"Everybody knows where all the streets go. Everybody knows who lives where, whereas the Russians are fumbling their way around a foreign country," she added.

Here's one remarkable fact of this war: Russia still hasn't captured a single major city.

The Russians are on the outskirts of several cities, where heavy fighting plays out daily. And the Russians were within 10 miles of the capital Kyiv during the early days of the war, which began on Feb. 24.

But they recently retreated from around the capital Kyiv, heading north into neighboring Belarus. Those troops are being resupplied, according to the Pentagon, and at least some are expected to travel across Belarus and Russia, and rejoin the fight in eastern Ukraine.

But just getting there poses some challenges, says Schake.

"The Ukrainians have interior lines of communication. They can move troops inside their own country," she said. "The Russians have to go out and around [Ukraine], extending the mileage on tanks and everything else."

Russia had no single commander in charge as it attacked Ukraine from the north, east and the south. U.S. and European officials now say that Russia has put Gen. Aleksandr Dvornikov in overall command.

He was overseeing the southern sector of the war, which included Russia's heavy bombing of the coastal city of Mariupol.

Dvornikov, 60, previously served as the commander of Russian forces in Syria, where they supported Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad. The Russian forces helped stabilize Assad in Syria's civil war, but were also blamed for frequent attacks on hospitals and other civilian targets.

Analysts say a single commander in Ukraine might be able to provide better command and control over Russian forces, which so far have been plagued by poor planning, logistics problems and a tough Ukrainian defense.

The next phase is likely to be concentrated battles in the east

In the first stage of the war, the Ukrainians were highly successful with ambush attacks, using small, mobile weapons, like Javelin and Stinger missiles supplied by the U.S. These weapons are fired from the shoulder of a single soldier, and can take out a tank or a low-flying plane.

But the Ukrainians are pleading for heavy weapons, like tanks and big artillery guns, that could be critical in the fighting to come. They are getting some of what the want — but so far in small numbers.

The Czech Republic has sent a few tanks. Britain is chipping in with armored vehicles. Slovakia has sent an S-300 anti-aircraft system that can bring down high-flying Russian fighter jets.

But it's nowhere near the scale of what Russia possesses.

"They just need everything," said Lawrence Freedman, professor emeritus of war studies at King's College London. "You know, wars are very greedy in using up material."

Freedman said the fighting in the east could feature entrenched battles more suited to Russia's large, hulking weapons.

"The Ukrainians talked about it being like a World War Two battle," he said. "The two sides could be hammering away at each other with artillery."

Yet he also notes that Russia's military struggles so far could multiply as the fighting grinds on.

"They are badly damaged. They've lost a lot of kit. They've lost a lot of people. The morale will be down. They're scraping around for reserves," said Freedman. "The army is just not as strong as it was six weeks ago. Indeed, it's it's been in many respects degraded."

The Pentagon and European officials estimate that Russia has lost somewhere between 20 to 30 percent of the combat strength it sent into Ukraine.

A test of endurance for both sides

There are no signs the war will end quickly. Many military analysts are forecasting months of fighting. U.S. Gen. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joints Chiefs of Staff, testified to Congress last week that he expects the war to last years.

So how much endurance can each side can each side muster?

On the Ukrainian side, about a quarter of the population has been driven from their homes, many cities and towns have been badly battered, and the economy is in ruins.

But the war has united Ukrainians, who've shown a strong will to fight, and no appetite for compromise, says Schake.

"The overwhelming majority of Ukrainians want Russia pushed out of their country, and that's a powerful force preventing a negotiated settlement," Schake said.

Russian leader Vladimir Putin didn't get the quick and easy victory he expected, and now faces a protracted conflict as well as sweeping Western sanctions that are expected to shrink Russia's economy by 10 percent or more this year.

Putin cut his losses and withdrew troops from northern Ukraine, opting to pursue scaled-back ambitions in the east, where pro-Russian forces have controlled territory in the Donbas region since 2014.

Putin still has the military resources to carry on the war indefinitely. And even if the war keeps going badly for Russia, Putin is likely to keep on fighting until he works his way through the "five stages of grief," according to Gideon Rose.

"Denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance," Rose said. "What ultimately has to happen is Putin has to accept defeat and choose to walk away, choose to retrench. And that is something that is a psychological process, not just a strategic process."

And that, he says, could take a long time.

Honduran migrant Eric Villanueva carries his son, Eric, 7, onto the shore of the Rio Grande after crossing the U.S. border from from Mexico on July 9, 2021. (photo: Paul Ratje/AFP/Getty Images)

Honduran migrant Eric Villanueva carries his son, Eric, 7, onto the shore of the Rio Grande after crossing the U.S. border from from Mexico on July 9, 2021. (photo: Paul Ratje/AFP/Getty Images)

No one should be surprised at reports that migrant children are still being abused at U.S. facilities.

Despite that vow, a new whistleblower letter reported by Vice News this week provides the latest in a long list of examples of how the United States has continued to fail migrant families, particularly migrant children.

Sent to members of Congress from the Government Accountability Project on behalf of whistleblowers who worked at the Fort Bliss emergency intake facility last spring, the letter describes conditions that amount to child abuse. Allegations include children being denied basic needs and being subjected to unsafe conditions, and of “a culture of secrecy lacking any method to address numerous concerns in which bullying, rioting and sexual harassment of children went unaddressed.”

These latest revelations appear to corroborate a July report from NBC News, with audio from Fort Bliss, that included “allegations of sexual misconduct by staff toward minors, acknowledgment that the children were running low on clean clothes and shoes, and a reluctance by officials to make public the scope of the facility's Covid outbreak.”

How much have we learned as a country over these past 11 years and three presidential administrations? Apparently not enough. Despite all the attention given to what former President Donald Trump’s administration did to separate families, the majority of Americans — at least those who support Democrats — have tended not to care as much about family separations and awful conditions before or after Trump.

Migrant children and families have rarely mattered to modern-day American presidents, unless it’s election season.

During a tense presidential debate exchange in 2020, Joe Biden called Trump’s family separation policy “criminal,” but minutes later, admitted to mistakes that were made in carrying out an Obama administration policy that tried to dissuade unaccompanied migrant children from showing up in the United States but led to children being crowded in cages. In admitting to that mistake, Biden said, "It took too long to get it right.”

But have we ever gotten it right?

“One month into his term, it's starting to look like Biden overpromised on rapid changes to an immigration system groaning under the strain of decades of neglect, abuse and competing priorities under outdated laws,” fellow MSNBC columnist Hayes Brown wrote in February 2021.

Part of Biden’s promise not materializing falls squarely on Republicans, especially those on the nativist, white supremacist Trump wing. Long gone is the party that only nine years ago was pushing for a bipartisan immigration bill. Now the GOP is all-in, no questions asked, on enforcement, detention, deportation and exploitative political theater — such as Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s promise this week to bus migrants to Washington, D.C.

Democrats, though, lack backbone or bravery, and this week’s whistleblower letter proves that the mistakes of the past have never been corrected. The current enforcement-heavy immigration machine originated in the mid-1990s under Bill Clinton, the president praised by Democrats in campaign ads for his hardline immigration stances. A 1996 law he signed has essentially dictated immigration enforcement to this day, and as a country we have never looked back. Presidents Bush, Obama, Trump and Biden have just been passing the baton from one to another, especially after the September 11 attacks, which led to the creation of a new agency called Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE.

When it came to migrant children, however, the 1997 Flores settlement was supposed to ensure they were not subjected to the same enforcement treatment as adults. While the most notable violations of this settlement occurred during Trump's term, family detentions and violations of Flores were happening under the Obama administration as well. Those violations might not have been on the same level as what Trump did, but they happened.

That’s why nobody should be surprised about a whistleblower letter during Biden’s administration. According to this week's count by the Department of Health and Human Services, close to 17,000 migrant children are being held. Health and Human Services is agency that created emergency intake centers, such as the one at Fort Bliss.

Meanwhile, according to what Vice News reported, Health and Human Services insists that all is well now.

“We act quickly to address any concerns and have proactively closed sites that didn’t meet our standards,” an agency spokesperson told the outlet in response to the whistleblower letter. “It remains our policy to swiftly report any alleged instances of wrongdoing to the appropriate authorities.”

Yet the patterns persist. The United States immigration system has emphasized enforcement and detention for years, ignoring the human faces and the lives behind the numbers. At some point, there needs to be a deeper reckoning of what has failed. It’s not just the way those policies have been carried out; it’s the policies themselves.

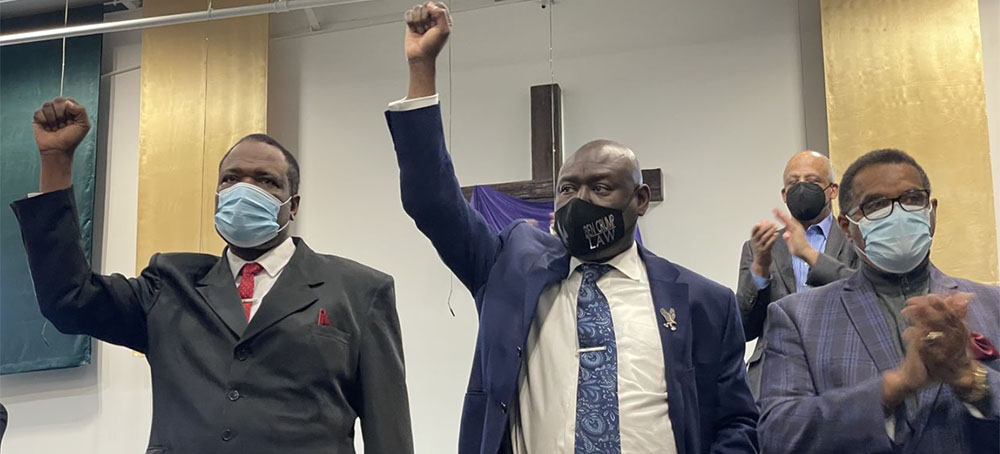

(From left): Kent County Commissioner Robert Womack and Ben Crump, a national civil rights attorney, raise their fists high in support of the family of Patrick Lyoya. A community conversation, which featured Crump as a speaker, was held at the Renaissance Church of God in Christ in the Family Life Center in Grand Rapids on Sunday, April 10, 2022. (photo: M Live)

(From left): Kent County Commissioner Robert Womack and Ben Crump, a national civil rights attorney, raise their fists high in support of the family of Patrick Lyoya. A community conversation, which featured Crump as a speaker, was held at the Renaissance Church of God in Christ in the Family Life Center in Grand Rapids on Sunday, April 10, 2022. (photo: M Live)

“Justice for Patrick!” shouted Crump, holding a clinched fist high in the air, inside the Renaissance Church of God in Christ in the Family Life Center in Grand Rapids.

“Justice for Patrick!” the packed crowd responded.

Crump — who has represented the families of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Trayvon Martin — was one of half a dozen speakers to take part in a community conversation forum Sunday, April 10, at the Grand Rapids church.

The forum, organized by Kent County Commission Robert Womack, featured Black clergyman from all over Grand Rapids and other Black community leaders.

Womack reached out to Crump the days following Lyoya’s death and shared the news.

“This is about a broken-hearted family,” Crump said, standing side-by-side with members of Lyoya’s family. “A broken-hearted Black family, who yet again has lost a loved one unjustly at the hands of the individual who was supposed to protect her son.”

The fatal police shooting occurred on April 4, when an officer conducted a traffic stop on a vehicle with a license plate that was not registered to it. A fight ensued, police said, that ended when the officer fired his weapon and killed Lyoya.

In the days after the shooting, calls grew louder for police to release video footage. These came as Kent County Prosecutor Chris Becker asked police not to release any evidence, including footage, until the investigation is complete.

“We are here demanding truth, transparency that will lead us to justice,” Crump said Sunday.

“When this video is made public, it is going to make people all over the world be emotional,” Crump said. “And it’s only right that they’re emotional because it demonstrates their humanity to see a human being life end in such an unnecessary manner … and such a horrific manner.”

Peter Lyoya, Patrick’s father, said Michigan State Police recently showed him cruiser dashcam video. He claimed the officer shot Patrick Lyoya in the back of the head while he laid face down on the ground. Grand Rapids police have not yet revealed what the video shows.

Grand Rapids Police Chief Eric Winstrom has committed to releasing the video by noon Friday, April 15.

On Saturday, April 9, hundreds of supporters marched through the city’s Boston Square neighborhood with members of Lyoya’s family. They marched to the Center for Community Transformation, where a candlelight vigil was held.

A pro-union poster is seen on a lamp pole outside a Starbucks location in Seattle's Seattle. (photo: Toby Scott/SOPA Images/Lightrocket/Getty Images)

A pro-union poster is seen on a lamp pole outside a Starbucks location in Seattle's Seattle. (photo: Toby Scott/SOPA Images/Lightrocket/Getty Images)

Starbucks fired the 20-year-old barista and organizer just days before employees begin voting on whether to unionize.

Sharon Gilman, 20, a student at nearby North Carolina State University, had worked at Starbucks since May 2020 and also trained other baristas at the store. Gilman told VICE News Sunday that she didn’t purposely break the three-compartment sink while she was washing dishes, and that she believes she was fired for being a pro-union employee who’d spoken to the press.

“My name was on the letter, my name was on the press release when we went public,” Gilman told VICE News. “I think this is Starbucks' way of making a statement of what could potentially happen if we were to vote yes for the union.”

The Raleigh store is one of more than 200 that have filed for a National Labor Relations Board election since the first store, in Buffalo, voted to unionize in December, according to a tracker compiled by labor outlet More Perfect Union. Workers at 15 of 16 stores where results have been counted since have voted for a union, including six in New York last week.

Workers at the Raleigh store will begin their vote on union representation later this week.

The incident in question happened on Feb. 13, just one day before Gilman and six other coworkers published an open letter to then-Starbucks CEO Kevin Johnson stating their intent to form a union at the Starbucks store. That night, Gilman was washing dishes in the back of the house and was cleaning the floor drain using the spray head of the sink when the spray head snapped.

“The sink just kind of fell off the wall onto me,” Gilman said. “I wasn't injured, but it did fall off and I was holding it up and there was water spraying.”

“I heard her scream when it happened, and could see how scared she was when the sink collapsed on her,” Elsa Englebrecht, another Starbucks worker and leader in the union campaign, said in a statement provided Sunday by the union.

Gilman said she and her co-workers took photos and video of the broken sink, which was later fixed. But more than a month later, on March 26, Gilman arrived at work to find her district manager wanting to talk to her, which she assumed was about the union.

The district manager instead told her she needed to write a statement about the sink, said a repairman had determined the sink couldn’t have been broken by accident, and that the store had video of when the sink broke. In an email, Starbucks spokesperson Reggie Borges told VICE News that “video footage confirmed [Gilman] forcefully pulled on the hose until it snapped.”

On Saturday, two weeks after she found out she was under investigation, Gilman was fired.

Gilman told VICE News that she didn’t break the sink on purpose. “Nothing memorable happened [that night]. I was not frustrated. I was not angry,” Gilman recalled of that night. She also said that she doesn’t believe she has the physical strength to break the sink in the manner she was accused of doing.

“I was in disbelief. I don’t work out. I’m not a freaking macho man,” Gilman told VICE News. “As a 20-year-old female, I didn't know that I had the strength to pull, to break a metal sink clear off the wall.”

Gilman did not admit to wrongdoing in the statement she wrote to her manager about the sink, but she said she couldn’t argue with the company’s interpretation of the video. Both the company and Gilman also confirmed that she originally said she was cleaning the back of the sink and then later said she was cleaning the floor drain; Gilman said she initially didn’t remember everything about the situation at the time she was asked.

“I've never been fired from a job before,” Gilman, who said she’d never been written up in the nearly two years she worked at the store, told VICE News. “I think I had a little bit of a panic attack when it happened. I didn't know what to do.”

Both Gilman and the company also said she was offered a chance to watch the video but declined.

“I suppose I just didn’t see the point in arguing back to them, because at the end of the day they’re corporate and I’m just a barista. They’ll see what they want to see,” Gilman said. “There are partners at my store that have broken company policies, but their names weren’t on the letter or in the press release, so they’re safe.”

“I’m 20 years old, a junior in college, overwhelmed with everything, and this just sprung on me a month and a half after the whole thing happened,” Gilman said. “I didn’t see the point in arguing with them because I’m replaceable. It’s sad but true.”

“At the end of the day, they can just hire a new person and go on with their lives,” she added.

Workers at this particular Starbucks store have complained of malfunctioning equipment in the past. In the letter sent to Johnson, workers raised a particular incident in December—which some employees at the store now refer to as “fume-a-geddon”—in which the plastic encasement of a store oven melted and the store’s lobby was filled with fumes and smoke.

“This incident led to one of our best shift supervisors leaving the company because she no longer felt supported,” the partners wrote in the February letter. “We will no longer tolerate an unsafe work environment.”

Alyssa Watkins, a shift supervisor and lead organizer at the store, told VICE News that after the ovens began to fail, she suffered from lightheadedness and a migraine that lasted for more than two days. Watkins filed a complaint with the North Carolina Department of Labor’s OSHA division on Dec. 6, but in February, the agency notified her that it closed the complaint after the store replaced the ovens.

Though this particular Raleigh store opened only two years ago, Gilman said the store often has trouble with espresso machines and card readers not working. “It’s not an abnormality for something like this to happen at our store,” she said.

Gilman is not the first organizer at a Starbucks store to be fired. Starbucks Workers United, the union representing Starbucks workers, told VICE News last week—before Gilman was fired—that it believes at least 16 Starbucks workers have been fired in retaliation for their union activity.

“Our ballots are supposed to be mailed at the start of this week, and the incident they're firing her for happened two months ago,” Watkins said in a statement provided by the union. “It's very clear this is an effort to stop our unionization.”

Starbucks has repeatedly insisted it has not retaliated against organizers. “We have in no way, shape, or form retaliated against a partner because of their interest in unions or unionization efforts,” Borges told VICE News Friday. “There's been no situation where that action was taken strictly because that partner has an interest in unionization or has unionization ties."

But in a few similar cases the NLRB has heard so far, they’ve disagreed. In March, the agency issued a complaint against Starbucks after it fired Phoenix barista Alyssa Sanchez and suspended shift supervisor Laila Dalton, finding that the company retaliated against them. Dalton was fired April 4, the same day interim CEO Howard Schultz held a town hall with employees where he said unions were “assaulting” American companies like Starbucks.

In February, the company fired seven pro-union Memphis workers after they gave a local news crew an interview inside their store. Bloomberg News reported Friday that the NLRB found the firings were illegal and will file a complaint against the company unless it settles with the workers, which the NLRB confirmed in an email to VICE News.

Starbucks Workers United said in a release that they will file a charge with the NLRB against Starbucks over Gilman’s firing, and that a protest at the store is set for Monday morning.

“In terminating Sharon, Starbucks continues to treat us inhumanely, and displays a callous disregard for the right of Starbucks partners to unionize,” the union said in a Sunday press release.

President Nayib Bukele speaks in San Salvador, El Salvador on January 5, 2022. (photo: Camilo Freedman/APHOTOGRAFIA/Getty Images)

President Nayib Bukele speaks in San Salvador, El Salvador on January 5, 2022. (photo: Camilo Freedman/APHOTOGRAFIA/Getty Images)

Nayib Bukele has overseen multiple violent crackdowns on basic civil liberties across El Salvador during his time as president. With his recent declaration of martial law against gangs, it’s only getting worse.

In a single weekend, El Salvador experienced its highest homicide toll since its twelve-year US-backed civil war: seventy-four dead in forty-eight hours, with sixty-two murders on Saturday, March 26 alone. The act of mass terror appears to have been ordered by the leadership of the nation’s most powerful criminal gang, MS-13. Victims were largely chosen at random. Delivery workers, commuters, street vendors, and shop patrons were gunned down in broad daylight, their bodies displayed in public view across twelve of the country’s fourteen departments.

Bukele responded in kind. Security forces laid siege to working-class neighborhoods, conducting indiscriminate arrests that saw over six thousand people disappeared into the country’s miserably overcrowded jails in less than a week. The president has inundated social media with images of police brutality and collective punishment, even branding the campaign with the hashtag #GuerraContraPandillas (“war against gangs”). The crackdown, however, is no innovation. Instead, it is a return to the same US-backed security strategies that spawned the current crisis.

The Art of the Deal

President Bukele made much of a drop in murders since his 2019 election, attributing the reduction to the success of an ill-defined “territorial control plan.” March’s horrific spectacle, however, demonstrated that organized crime remains more powerful than ever. The carnage confirmed what the government continues to deny: the administration had brokered a secret agreement with the gangs to suppress the homicide rate.

Government negotiations with gangs in El Salvador is nothing new. From the municipal to the national level, governance without compromises with these powerful illicit actors is all but impossible. In 2012, the leftist FMLN government began clandestine talks with the imprisoned gang leadership, using religious mediators and international observers to broker a truce between the two rivals in exchange for alleviating prison conditions.

When media broke the story, however, the public reaction was polarized. The Obama administration’s classification of MS-13 as a transnational criminal organization struck a further blow against open dialogue. As the deal entered a second, more public phase in 2013, incorporating municipal authorities to provide prevention and rehabilitation programs, El Salvador’s right-wing Supreme Court forced the ouster of the FMLN defense minister who had been a key broker of the truce.

The deal began to unravel, and murders resumed their upward course. In 2015, the high court designated both MS and the 18th street gang terrorist organizations, specifically outlawing any “agreements” or “negotiations.” With homicides at all-time highs, the FMLN reverted to the repressive security methods of the past.

Bukele, whose political career began in the FMLN, directed his government to prosecute former FMLN president Mauricio Funes and Defense Minister David Munguía Payés for their role in the truce. But the sharp reduction in homicides under his administration, coupled with a sinister surge in forced disappearances, prompted suspicions of a secret pact. These were corroborated by local reporting.

El Salvador’s refusal of US extradition requests for fourteen indicted MS-13 members in June 2021, four of whom were since released from their maximum security prisons, raised further questions. Whatever the terms of the arrangement, the recent killings, together with Bukele’s venomous reaction, suggest that the deal has fractured.

Made in the USA

The birth of MS-13 and the 18th street gang in the streets and prisons of Los Angeles is only one aspect of the US origins of El Salvador’s gang crisis. Key to the current situation are the zero-tolerance policing strategies that, along with the refugees deported for alleged gang ties, were exported to El Salvador by the US government.

“For decades, the US has poured tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars into punitive and militarized methods of combatting violence and insecurity in El Salvador,” explains Yesenia Portillo, program director of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES).

For ruling elites, after the civil war’s negotiated end in 1992, policing became key to containing the social fallout of neoliberal restructuring and the unfulfilled promises of peace. Researchers like Elana Zilberg have documented how the draconian anti-gang policing strategies pioneered in Los Angeles in the 1990s were zealously imposed on postwar El Salvador. The far-right administrations that governed between 1989 and 2009 eagerly implemented these zero-tolerance policies, which were translated in El Salvador as “mano dura” or “iron fist.” These campaigns of mass arrests and punitive reforms effectively criminalized poor young men across the country.

Plan Mano Dura was implemented under President Francisco Flores in 2003 and included the first postwar deployment of the military in police patrols, a tragic reversal of the demilitarization gains of the 1992 Peace Accords. In 2004, President Antonio “Tony” Saca followed up with Plan Súper Mano Dura, further increasing sentences and straining the capacity of the national prison system. Saca also imposed an anti-terror law modeled on the Patriot Act that, in addition to prosecuting alleged gang members, was deployed against leftist protesters. Over thirty thousand accused gang members were arrested between 2003 and 2005.

These repressive strategies only radicalized the gangs, making their structures more complex and sophisticated. As Zilberg writes, “Limiting access to public space, mass incarceration, and increased deportation all induce closer ties by actively promoting association between gang members on local, regional, national, and transnational scales.” Today, El Salvador has the second-highest incarceration rate in the world. (You can guess who retains first place.)

In addition to helping model legislation and policy, the US government takes an active role in training El Salvador’s law enforcement. Dating back to a 1995 Clinton administration initiative, the International Law Enforcement Academy in San Salvador finally opened in 2005. Under the banner of combating transnational organized crime, US agencies from the IRS to the FBI and the DEA sponsor courses for officials from across Latin America, drawing comparisons from critics to the infamous School of the Americas.

Meanwhile, the State Department’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) runs its own programs, like the Gang Resistance Education and Training (GREAT), which certifies cops to preach against the twin evils of joining gangs or migrating to the US in Salvadoran elementary schools. The INL has also spent over $2 million since 2012 on a Police Athletics League in El Salvador.

Other initiatives focus specifically on incarceration. The US has trained dozens of Salvadoran maximum security prison officials on topics from inmate transport to “riot control and baton use.” US funding also supports the expansion and fortification of prison infrastructure, like thirty maximum security cells in the Zacatecoluca prison built in 2014.

The United States also directs local law enforcement operations. In 2007, the FBI created its first Transnational Anti-Gang Task Force (TAG) in El Salvador, comprised of agents from the FBI and State Department, together with Salvadoran police and prosecutors. These task forces now operate in Honduras and Guatemala as well. In 2013, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)’s Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) signed a memo of cooperation with the Salvadoran police to support the work of Transnational Criminal Investigative Units (TCIUs) that operate in El Salvador through ICE and the State Department.

Since 2012, the Justice Department’s Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Development, Assistance and Training (OPDAT) operates three State Department–funded Resident Legal Advisors in El Salvador. In November 2020, the Department of Justice announced 572 arrests in El Salvador of alleged gang members as part of Operation Regional Shield. Through this program, Central American prosecutors trained by the FBI, HSI, and OPDAT work with local TAG and TCIUs to carry out investigations that brought charges against over eleven thousand alleged gang members between 2017–2020.

Then there’s the security aid. Between 2013 and 2018, El Salvador received $10.5 million in foreign assistance from the Department of Defense (DoD), allocated as foreign military financing and military education and training. From 2016 to 2020, the DoD provided $15 million in foreign military financing alone. Since 2008, millions more have been provided through the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), modeled on the disastrous Merida Initiative with Mexico.

Even though Congress cut the $1.9 million El Salvador had been receiving in Foreign Military Financing to purchase US weapons and equipment in 2020, the country continues to benefit from CARSI and Pentagon spending. In August 2021, as the State Department decried the “decline of democratic governance” under Bukele, the US Embassy celebrated a donation of twelve MD 530F helicopters to the Salvadoran Air Force.

Grifter’s Paradise

The thirty-day state of exception enacted on March 27 suspends freedom of association and the right to an attorney, extends the period of detention without cause from seventy-two hours to fifteen days and authorizes police intervention into personal communications. Punitive reforms approved on March 30 raise sentences for gang membership to up to thirty years for adults and ten years for children as young as twelve. Bukele’s lawmakers authorized judges to rule over proceedings anonymously. They also appropriated additional funding for Defense and Public Security, increasing a military budget that, even adjusted for inflation, was already well above its civil war peak.

Like the repressive campaigns of the past, these measures can easily be deployed against dissidents. Another law, hastily approved April 5, broadly criminalizes reporting on gang activities and is being denounced by the press as censorship.

The state of exception may have been copied and pasted from the pandemic lockdown, but it occurs in a markedly deteriorated democratic context. In 2020, Supreme Court resistance to rampant constitutional and human rights violations provoked a protracted constitutional crisis. But after the 2021 midterms, the president’s newly installed legislative majority illegally ousted all five magistrates and the attorney general, replaced them with loyalists, then proceeded with a sweeping purge of the lower judiciary. The administration has done away with all checks on executive power, clearing the way for total impunity.

In the meantime, the president is shoring up his base. For his domestic constituency, he assumes the role of a vengeful savior against the satanic forces of criminality, spewing bellicose macho bravado online. Bukele ridicules human rights and due process concerns, accusing advocates of siding with the gangs and conspiring with the opposition. He announced ration cuts for the incarcerated, threatening to starve inmates if murders spike again. For his foreign fans, however, he continues to portray El Salvador as a beacon of liberty, courting international investment from assorted crypto concerns.

The weekend that homicides surged, Bukele was busy entertaining a delegation of foreign bitcoin investors. Former Blockstream executive Samson Mow joined Mexican oligarch Ricardo Salinas Pliego and bitcoin evangelists Stacy Herbert and Max Keiser, touring the country in a private jet to hype the government’s proposed emission of bitcoin bonds and geothermal-powered bitcoin mining. As the country entered martial law, the crypto dignitaries partied in an exclusive beach hotel.

Bukele’s authoritarianism — the militarized repression, the state surveillance of journalists and dissidents, the political persecution — sits in apparent contradiction with his sales pitch for crypto-utopia. But this has been the libertarian fantasy all along: vast social inequality, sustained at gunpoint. Unrestricted capital accumulation has long required antidemocratic, even violent state intervention — Eduardo Galeano once observed that US-backed Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet threw people in prison “so the prices could be free.”