Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The arrests of a director and a playwright in Moscow signal a new chapter in the Putin regime’s eradication of dissent.

About a year earlier, I was startled to realize that Berkovich was still in Russia. Most of my extended circle had left in the days and weeks following the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, in February, 2022. Russian authorities had brutally disbanded protests, passed a set of laws banning antiwar speech, hounded independent media out of the country under threat of arrest, and banned Facebook. Those who stayed took a newly standard set of precautions, including “locking” their Facebook accounts so that only their “friends” could see their activity. Berkovich spent ten days in jail for protesting the invasion and then kept posting openly, publishing poems, and writing about her reactions to the war and her frustrations with her teen-age daughters, both of whom she had recently adopted.

I didn’t know her well. We met perhaps a decade ago, when I was still living in Moscow, and Berkovich, freshly graduated from the famed Moscow Art Theatre School, was involved in the production of a play based on interviews with people whose grandparents had been Stalin’s henchmen. The play was staged at the Sakharov Center, which was shuttered by the government last week. I had also seen one of the first plays that Berkovich directed, “The Man Who Didn’t Work,” which was based on an activist’s notes of the courtroom proceedings in the trial of the poet Joseph Brodsky. Soviet citizens were required by law to be engaged in productive work. Brodsky was found guilty of “malicious parasitism” and sentenced to internal exile and mandatory labor. (The play was staged at Memorial, a human-rights and history organization that was shut down by the government last year.)

In the play, a judge demands of Brodsky, “What did you ever do to benefit the motherland?”

“I wrote poetry,” Brodsky responds. “That is my work. I am certain that every word I’ve written will benefit many generations of people.”

. . . . “Tell the court why you didn’t work.”

“I worked. I wrote poetry.”

“Answer the question. Why didn’t you labor?”

“But I labored. I wrote poetry.”

“Why didn’t you study that at an institution of higher learning?”

“I thought . . . I thought it was a gift from God.”

I took my older kids to see both plays. For years afterward, Yolka, who was ten or eleven when she first watched them, would return to the one about Brodsky. When I was writing this column, I asked what had stuck with them, and Yolka texted back, “I remember it seemed a little too related to how it was in Moscow at the time.” Back then, this response would have sounded hyperbolic. Russia was cracking down on dissent, but poets weren’t going to jail for writing poetry.

Berkovich directed roughly a dozen more plays. Last year, her production of a play written by Petriychuk—now her co-defendant—won top honors at the Golden Mask, Russia’s leading theatre festival. The name of the play, probably best translated as “Finist, the Brave Falcon,” is a reference to a Russian fairy tale about an elusive male love object who has the ability to turn into a bird or a feather. The play is based on the stories of young Russian women who met ISIS fighters online, converted to Islam, married the men in virtual ceremonies, and went, or tried to go, to Syria to join the fight with their husbands. Many of the women were later arrested and prosecuted in Russia, and the play made use of the transcripts of their police interviews. It was a subtle, tender, and slightly absurdist portrayal of loneliness and the longing for love. The production opened with the cast singing, in English, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.”

Before the Russo-Ukrainian war, I didn’t know that Berkovich wrote poetry. The first poem that caught my attention went viral in the Russian blogosphere about a year ago, as Russia was staging its annual grand celebration of victory in the Second World War. In the poem, the ghost of a man who fought in the war visits his grandson in present-day Russia and asks him not to make use of his image or legacy. “We don’t need you to be proud of us / Nor to be secretly ashamed of us. / All I ask is that you / Make it so I am finally forgotten,” the grandfather pleads.

But then I’ll forget how we looked for that painting

In the Russian Museum

How I woke up wet

And you dressed me

How we read Prishvin together

And looked for the North and South Poles in the atlas

How you explained why planes

Leave a white stripe in the sky.

How you gave me

A magnifying glass.

That’s all right, the grandfather says

As he disappears.

None of that did you any good.

In times of crisis, Russians write poetry, and this was one of many poems making the rounds. Gradually, though, I realized that Berkovich was probably the poetic voice of this period. One after another, her poems, posted on Facebook, put words to the agony of wartime. Many of them had the form of litanies.

Needed: clothes for a woman

Age seventy-nine

From a city that no longer exists.

A T-shirt, size M, for Mariupol,

A jacket, size L, for Lysychans’k.

A bra with a B cup,

For Bucha and Borodyanka.

So began one poem. Another listed imaginary—but typical—cases of Russians getting arrested.

Andrey Alexandrovich Lozhkin

63 years old

A dentistHe raises a blindingly white sheet of paper overhead

His beard is flying in the wind

Everyone will be looking for him until morning

By then he no longer has a poster or a beard or any hope of getting out . . .Daniil Yegorovich Milkis

24 years old

A student, a nerdHe “likes” a joke on someone else’s Instagram

He has a girlfriend named Sonya and an inarticulate beard

He will send the ring with his lawyer

Sonya will say yes

He will talk about god and won’t be allowed to sit down in court

He’ll get four years and eight months

Thank god for that

The prosecutor asked for six years.

Like many people, I came to depend on Berkovich’s poems as a release for my own feelings. I nearly stopped marvelling at her decision to post openly. It helped that she interspersed the poetry with some decidedly prosaic rants, some about everyday life and some about politics. It was as though, in a way, she was the last person still living in prewar Moscow, where it was possible to use social media to say what you thought, if only to stay sane.

On May 4th, police searched the St. Petersburg apartment of Berkovich’s mother and grandmother (both women are well-known writers and human-rights activists) and detained Berkovich in Moscow. Petriychuk was detained at a Moscow airport. The following day, they appeared in court, where investigators asked that they be placed in pretrial detention. They are being charged with “justifying terrorism.” The charges are based on the play “Finist, the Brave Falcon.”

Meduza, an independent Russian news outlet working in exile, obtained a copy of the expert opinion that formed the basis for the charges against the two women. It says that the play contains elements of ISIS ideology and, simultaneously, “the ideology of radical feminism,” including “images of the denigration of women in an androcentric world in any space where a woman encounters men, which gives her the right to fight against this state of affairs.” Both perceived ideologies are seen as evidence of support for terrorist tactics. The charge can carry a penalty of up to seven years behind bars.

I have found it hard to write about the ongoing crackdown in Russia. After a while, it seemed that there was nothing left to say—even when, last month, the journalist and politician Vladimir Kara-Murza was sentenced to twenty-five years in prison for “high treason.” The sentence should have been shocking, but, just days earlier, the Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich had been arrested on analogous charges. The arrests of Berkovich and Petriychuk, though, do signal a new chapter. For the first time in the post-Soviet era, Russia has explicitly arrested people for creating art. They are not charged with high treason, like Kara-Murza, or espionage, like Gershkovich, or “discrediting the armed forces” or “spreading false information about the special military operation”—the charges created to punish journalists for covering the war—or for “hooliganism,” as the protest group Pussy Riot was, but for the content of a play they wrote and staged. And also, of course, in Berkovich’s case, for acting as though she could keep expressing her thoughts and feelings out in the open. On the other hand, even as I write this, I understand that the novelty is subtle, if it exists at all: parsing the distinctions in how the Putin regime eradicates difference is a fool’s errand.

Last Friday, as the two women were being charged, several dozen people gathered outside the courthouse in Moscow. After the hearing, one of Berkovich’s friends wrote on Facebook, in a post visible only to “friends,” “I wanted to write what I think, but then I remembered that I live in Russia and decided not to. You know anyway.” Berkovich’s own Facebook account has vanished.

READ MORE  Federal prosecutors say Santos allegedly 'devised and executed a scheme' aimed at defrauding donors to his 2022 political campaign. (photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

Federal prosecutors say Santos allegedly 'devised and executed a scheme' aimed at defrauding donors to his 2022 political campaign. (photo: Andrew Harnik/AP)

Federal prosecutors say he allegedly "devised and executed a scheme" aimed at defrauding donors to his 2022 political campaign.

"This indictment seeks to hold Santos accountable for various alleged fraudulent schemes and brazen misrepresentations," said U.S. Attorney Breon Peace.

"Taken together, the allegations in the indictment charge Santos with relying on repeated dishonesty and deception to ascend to the halls of Congress and enrich himself."

According to the criminal indictments, Santos claimed the money would fuel his bid for office, but instead spent the cash on luxury designer clothes and to make a car payment and pay personal credit card bills.

Santos also faces a charge that in 2020, he fraudulently applied to receive unemployment benefits when he was employed and running for Congress in his first bid for public office.

"At the height of the pandemic in 2020, George Santos allegedly applied for and received unemployment benefits while he was employed and running for Congress," Nassau County District Attorney Anne Donnelly said in a statement.

Her office aided in the investigation.

The freshman lawmaker pushed the boundaries of conventional political scandal after his victory in last November's midterms. It was revealed that he fabricated most of the persona presented to voters.

Santos lied in interviews and campaign documents about his education, his professional accomplishments, his record as a champion volleyball player and his family's experiences in the Holocaust.

He also faced multiple investigations into how he raised and spent hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign cash, including a mysterious $700,000 gift he made to his own election effort.

It remains unclear where that money came from.

Santos, who has announced he plans to run for reelection in 2024, has become a pariah among many GOP leaders in New York, especially on Long Island.

The influential Nassau County Republican Committee distanced itself from Santos and called for him to resign.

Santos has remained defiant and at times even seemed to revel in the glare of media attention.

He has previously admitted to "embellishing" his resume, but repeatedly denied any criminal wrongdoing.

On May 6, Santos posted on Twitter a photo of a fortune cookie he said he had received at a meal.

"Life is more fun when you're the underdog competing against the giants," the fortune read.

The Santos controversy has created a political headache for Republicans, especially in New York, where GOP candidates face tough reelection fights next year.

Speaking Tuesday, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy said he wouldn't demand that Santos resign.

He compared the criminal charges against Santos to past cases involving Democratic lawmakers who remained in office while their cases played out.

"If a person is indicted, they're not on committees, they have the right to vote, but they have to go to trial."

Phone calls to Santos' congressional offices and to his attorney have gone unanswered. Santos also hasn't commented about the charges on Twitter.

Separate probes are also underway by the Nassau County district attorney in New York and the House Ethics Committee in Washington, D.C.

A statement released by the House panel in April stated an investigative subcommittee will examine whether Santos "engaged in unlawful activity" during his 2022 campaign.

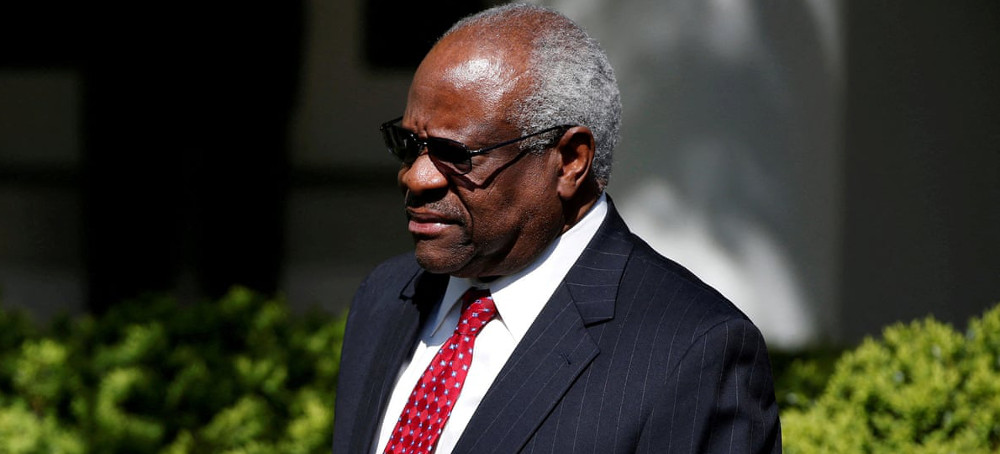

READ MORE  It was recently revealed that Harlan Crow paid for the private schooling of Clarence Thomas's great-nephew. (photo: Joshua Roberts/Reuters)

It was recently revealed that Harlan Crow paid for the private schooling of Clarence Thomas's great-nephew. (photo: Joshua Roberts/Reuters)

Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington says supreme court justice should resign over mega-donor gifts scandal

In an open letter to Thomas, Noah Bookbinder of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, or Crew, cited a “grave crisis of institutional legitimacy currently facing the supreme court”.

“For the sake of the court and for the sake of our democracy which depends on a judiciary that the public accepts as legitimate and free from corruption, we urge you to resign.”

He added: “Your conduct has likely violated civil and criminal laws and has created the impression that access to and influence over supreme court justices is for sale.”

Thomas has said he did not declare gifts from Crow including luxury travel and resort stays because he was advised not to do so, but will do so in future.

He has not commented on reports that Crow bought from him property in which his mother still lives rent-free; that Crow paid for the private schooling for Thomas’s great-nephew, who the justice said he was raising like a son; and that the conservative activist Leonard Leo secretively arranged payment of tens of thousand dollars to Ginni Thomas, the justice’s rightwing activist wife.

Leo and Crow deny wrongdoing.

In the case of the school fees, Thomas did declare a gift from another donor for the same purpose. Critics say this shows he knew he should have declared gifts from Crow.

Supreme court justices are notionally subject to ethics rules for federal justices but in practice govern themselves.

Democrats have called for Thomas to be impeached and removed. That is a nonstarter, as Republicans hold the House, where impeachment would begin, and will protect the 6-3 conservative majority which has handed down major rulings including the removal of abortion rights. Democrats have also called for ethics reform.

Senate Democrats sought to call the chief justice, John Roberts, to testify. Roberts refused. Democrats cannot use a subpoena to compel testimony – from Roberts, Thomas or any other justice – because without the ill and absent Dianne Feinstein of California they do not have the required majority on the committee.

Last week the judiciary chair, Dick Durbin, urged Roberts to confront the Thomas issue, saying the chief justice “has the power in his hands to change this”, adding that the “tangled web” around Thomas “just gets worse and worse by the day”.

On Tuesday, Crow rebuffed a request from the Senate finance committee, citing tax concerns, for a list of gifts given to Thomas. An attorney for Crow, Michael Bopp, called the request “a component of a broader campaign against Justice Thomas and, now, Mr Crow, rather than an investigation that furthers a valid legislative purpose”.

The committee chair, Ron Wyden, indicated Crow could now face a subpoena.

“The bottom line is that nobody can expect to get away with waving off finance committee oversight, no matter how wealthy or well-connected they may be,” Wyden said, promising to decide “how best to compel answers to the questions I put forward last month, including by using any of the tools at our disposal”.

Democrats on the judiciary committee also sent Crow a letter, asking for details of gifts to Thomas.

In his letter to the justice, Bookbinder said: “It has become clear that over the last several decades you have engaged in a longstanding pattern of conduct to accept and conceal gifts and other benefits received from … a billionaire political activist, and have disregarded your ethical duty to recuse yourself from cases in which you have a personal or financial conflict of interest.”

Crow insists he is simply good friends with Clarence and Ginni Thomas, with whom he refrains from discussing politics or business before the court. But outlets including the Guardian have shown that groups linked to Crow – a collector of historical memorabilia including paintings by Hitler – have had business before the court during his friendship with Thomas.

Bookbinder said reports about Thomas were “contributing to a catastrophic decline in public confidence that threatens to undermine the entire federal judiciary”. Public polling shows confidence in the court at historic lows.

Bookbinder told Thomas: “We know of no other modern justice who has engaged in such extreme misconduct.”

In 1969, Justice Abe Fortas resigned from the court, in part for accepting payment for outside activity. Fortas was paid $15,000 to teach summer school and took $20,000 from a foundation run by a convicted fraudster.

Bookbinder continued: “Indeed, [Thomas’s] receipt of consistent, lavish gifts and favors from a billionaire with an interest in the direction of the court is so far outside the experience of most of the American people, and so far beyond what most would consider acceptable, that it cannot help but further diminish the court’s credibility.”

He also charged Thomas with failing to recuse himself from cases involving his wife’s “personal or financial interests”, notably after the 2020 election, in a case regarding whether to release documents related to Donald Trump’s attempt to stay in power.

Thomas was the sole justice to say the documents should not be released. When they were, they showed Ginni Thomas’s involvement in Trump’s election subversion.

Bookbinder said: “It is increasingly difficult for people to trust that you are making decisions only based on the law and a commitment to justice.

“… The judiciary is built entirely upon a foundation of public trust. If that falls away, the institution will fail. While we appreciate your many years of public service, your conduct has left you with only one way to continue faithfully serving our democracy.

“For the sake of our judiciary and the sake of people’s faith in its legitimacy, you must resign.”

READ MORE  Texas National Guard soldiers added a layer of concertina wire along the border with Mexico in El Paso on Monday. (photo: Todd Heisler/The New York Times)

Texas National Guard soldiers added a layer of concertina wire along the border with Mexico in El Paso on Monday. (photo: Todd Heisler/The New York Times)

Gov. Greg Abbott is expanding state law enforcement on the border as some state leaders appear eager to test the waters on how far Texas can go in enforcing immigration law.

As Mr. Abbott began speaking on Monday from a lectern emblazoned with the words “Securing the Border,” about 200 soldiers from the National Guard hustled onto the planes.

“They will be deployed to hot spots along the border to intercept, to repel and to turn back migrants who are trying to enter Texas illegally,” the governor said, barely audible over the roar of the engines. Then he turned to watch the planes take off.

For two years, Texas has engaged in a multibillion-dollar attempt to arrest and deter migrants who cross into the state from Mexico, deploying helicopters and drones, National Guard troops patrolling the border in camouflage and state troopers racing down highways in black-and-white SUVs. The state has bused thousands of migrants to East Coast cities like New York and lined the reedy banks of the Rio Grande with concertina wire.

But the number of crossings into Texas has only increased.

Now, a new surge of migrants is already arriving at the U.S. border with the expected end on Thursday of a public health measure, known as Title 42, that for the past three years had allowed the government to rapidly expel a large number of migrants who arrived at the border.

Texas is doubling down on its response, not only sending more soldiers and police officers to the border but also pushing legislation that would impose new state penalties on migrants and human smugglers, as well as create a border police force and “border protection courts” to enforce state controls.

Mr. Abbott, a Republican, blames the Biden administration for undermining his state’s efforts so far to limit the number of migrants arriving from Mexico.

“If we were acting in isolation, we would have secured the border,” he said. “While Texas is doing everything possible to stop people from crossing the border, the president of the United States is setting out the welcome mat.”

The legislative actions, some of which were expected to pass the State House this week, would expand and make permanent elements of the border enforcement program that Mr. Abbott unveiled in March 2021 known as Operation Lone Star. Through the program, Mr. Abbott has pushed the envelope of what the law allows, using his power as governor to send the National Guard and state police to the border, and employing state trespassing laws to arrest migrants when they cross private land.

But states cannot enforce federal immigration law — that is up to the federal government — and Mr. Abbott has thus far resisted calls from some far-right conservatives to declare that Texas is being invaded, order the state police to arrest any migrants found in Texas and return them over the border to Mexico.

For now, when National Guard troops or state officers encounter migrants at the border, they most often turn them over to U.S. Border Patrol agents, who take them into custody under federal law, a process that allows many to stay and pursue asylum claims.

The bills now before the State Legislature — particularly a measure that would make it a state crime for migrants to cross from Mexico into Texas — would mark a big step toward a more direct state role in immigration enforcement and could run afoul of current constitutional precedent, several legal experts said.

Civil rights groups, immigrant advocates and Democratic lawmakers have opposed the bills as a cruel distraction from the need to provide aid to the desperate people who are making their way to the United States after fleeing poverty and violence. “The real issue at the border is that it’s a humanitarian emergency so we need a humanitarian response,” said Alexis Bay of the Texas Civil Rights Project. “We’ve seen all sorts of deterrence policies but people are still coming to the border.”

On Tuesday, the State House in Austin had been scheduled to discuss several big pieces of border legislation, including H.B. 7 and H.B. 20, which would create the new system of border courts and border police. Democrats delayed consideration of the bills for much of the day.

Some Texas officials, including the attorney general, Ken Paxton, have expressed an eagerness to take the question of state jurisdiction to court in the apparent hope that more conservative justices on the Supreme Court may be prepared to give broader authority to states like Texas to enact their own immigration laws.

Mr. Paxton said as much during a Senate committee hearing in March, when he told lawmakers that the state should set out to test the landmark 2012 case in Arizona in which the U.S. Supreme Court found that state enforcement of immigration law impermissibly intruded on federal authority. “We should test to see if the states can protect themselves, given the circumstances we’re in that we’ve never been in before,” Mr. Paxton said.

A particularly direct challenge to existing law would come from one bill, already passed in the State Senate, that would make it a violation of state law for someone who is not an American citizen to cross into Texas from a foreign country other than at a legal port of entry — something that is already a violation of federal law.

“It’s hard to imagine a more stark intrusion, a more direct intrusion by a state on what is traditionally thought of as the realm of federal immigration law,” said Pratheepan Gulasekaram, a law professor at Santa Clara University in California who has studied state efforts to regulate immigration.

In the short term, Texas has been readying itself for the end of Title 42 by creating teams of soldiers who can rush to areas where a large number of migrants are arriving. That has been the approach in cities like El Paso, where officials said soldiers had been placing miles of concertina wire near the border and providing an increased presence to discourage crossings.

“The surge is coming before Title 42 ends, is what is happening,” said Maj. Sean Storrud, who commands hundreds of National Guard soldiers stationed in El Paso.

Major Storrud — a high school math teacher from Marlin, Texas, when not called up by the Guard — said that what had been a mile-long barrier of concertina wire back in December had grown to more than 17 miles of wire, anti-climbing barrier and shipping containers. “It is a mixed media fence,” he said. “The idea is to divert them to the legal points of entry.”

But in many places, migrants have created holes allowing them to pass through the sharp wire, sometimes in full view of National Guard troops. The additional troops who were among those who flew into El Paso from Austin on Monday will in part be tasked with watching the fence and making sure no one tries to cross, Major Storrud said.

“The c-wire is only as effective as the soldiers who are guarding that wire,” he said, using an abbreviation for concertina wire.

If the troops flying out of Austin were sent on a familiar mission, they had at least been given a new name — the “Texas Tactical Border Force” — one that echoed the name of the state-level border police force being considered by Republican leaders in the State House.

The bill to create a separate “Border Protection Unit” within the Texas Department of Public Safety has been a priority of the House speaker, Dade Phelan. It has raised concerns among immigrant-rights advocates, because an initial draft would have allowed the new unit to deputize ordinary citizens to participate in operations, giving the color of state authority to private armed groups that have long operated in Texas.

Mike Vickers, who runs the Texas Border Volunteers, said his group had been patrolling on private land to act as lookouts and report suspicious activity to law enforcement for 16 years.

“We think it’s a great idea,” he said of the bills. He said opposition to the legislation was coming from “all these Democrats" who believed it would mean “a bunch of gringos out there wanting to arrest anyone with brown skin. It’s so stupid. But that’s kind of their mind-set.”

Last month, Mr. Vickers appeared at a rally in Austin along with the musician Ted Nugent and other conservative figures to support the legislation and urge Mr. Abbott to more directly challenge the federal government on immigration enforcement.

“It remains to be seen how this civilian unit will operate,” Mr. Vickers said. “But if they can coordinate it with law enforcement, I think it will be great.”

READ MORE  Pharmacy benefit managers have become known as the mysterious middlemen of the pharma trade - and as a useful scapegoat for drug companies seeking to deflect blame from their own pricing practices. (photo: iStock)

Pharmacy benefit managers have become known as the mysterious middlemen of the pharma trade - and as a useful scapegoat for drug companies seeking to deflect blame from their own pricing practices. (photo: iStock)

How pharmacy benefit managers found themselves the targets of a bipartisan push on drug prices.

Pharmacy benefit managers are companies that, behind the scenes, determine what patients have to pay for medications. They manage insurance benefits for prescription drugs, dictating which drugs are covered by insurers and what costs patients will face when they fill their prescriptions.

To do that, they negotiate discounts, or rebates, with drug manufacturers and afford privileged status to the companies that give them the best deals.

And over the past few decades, as the prescription drug market has evolved and become more lucrative, so have PBMs. They run their own mail-order and specialty pharmacies. More recently, they have begun merging with health insurers, creating behemoth companies with the power to determine where and how billions of dollars are spent within the US health system.

Pharmacy benefit managers have become known as the mysterious middlemen of the pharma trade — and as a useful scapegoat for drug companies seeking to deflect blame from their own pricing practices.

Now the Senate, as part of forthcoming prescription drug legislation, appears poised to impose new rules on them. The committee overseeing health care debated last week a slew of measures requiring PBMs to be more transparent about their business and cracking down on some of their moneymaking practices. Several PBM CEOs will testify before the committee on Wednesday.

“While the pharmaceutical industry blames the PBMs for high drug prices, the PBMs blame the pharmaceutical industry for high drug prices,” Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) said to open last week’s hearing. “The reality is both of them are right.”

Experts generally agree that these companies play a role in driving up drug costs for some US patients, even as they negotiate discounts with drugmakers that benefit others, and that the amount of secrecy about their financial arrangements warrants scrutiny.

But reforms to the PBM industry aren’t a cure-all for making drugs more affordable: Sanders said the PBM measures being considered in the Senate would not meaningfully lower the cost of medicine for most people, even if they would bring more accountability and transparency to the sector.

So reforming PBMs can’t be the end of the country’s debate over drug prices. But it’s an important step.

How PBMs evolved to play a critical role in US health care

If you’ve ever had a prescription filled, you’ve likely dealt with a pharmacy benefit manager — whether you realized it or not. Most people have their benefits managed by one of three companies: Express Scripts, CVS Caremark, and OptumRx, which together control about 80 percent of the market.

The primary function of pharmacy benefit managers is exactly what it sounds like: managing coverage for prescription drugs on behalf of health insurers.

In the 1960s, when the precursors to modern-day PBMs first emerged, most people paid for their medications out of pocket. This was in part because there were comparatively few drugs to take — certainly not the highly specialized treatments for hypertension, high cholesterol, and other chronic conditions that are commonplace today; while data from 60 years ago is scarce, the number of drugs being prescribed per American has grown by almost 50 percent since just the mid-1990s.

When Medicare was first created in 1965, it was “common” for private health plans to exclude coverage for prescription drugs. (Medicare did not begin covering outpatient prescription drugs until the mid-2000s.) But the US pharmaceutical industry soon began to develop more advanced, costlier drugs, and employers and their health insurers realized they would need to pick up some of the cost for those new treatments.

As they added that coverage in the 1970s and ’80s, the first PBMs formed within health insurers, according to Taylor Christensen, a physician who has researched their history and business practices. They were made up of early coders who connected the health insurer’s formulary, the information on the drugs the plan would cover and at what cost to the patient, to pharmacies across the country. This meant that, instead of filing a claim with their insurer, the patient could pay the out-of-pocket price at the pharmacy.

Soon, the employees specializing in pharmacy benefits saw a business opportunity. Through their work, they had a clearer look at how the costs of prescription drugs affect people’s behavior. They saw that lowering a drug’s copay, for example, led to more people taking that medicine versus a more expensive option, which saves the insurance company money. And rather than conduct that work for one company in-house, they realized they could spin their business off and become independent.

In the 1980s and ’90s, the modern standalone PBMs were founded with a simple pitch to health insurers: We can save you money if you delegate your prescription drug benefits to us. “They figured out they could do it better than each in-house insurance group,” Christensen said.

Health insurers decided that was a good deal. Then PBMs saw another business opportunity. Already in business with insurance companies, they turned around and made a pitch to drug companies, too: Through our formularies — which can give priority to certain medications with those lower copays — we can direct more customers to your medications.

But PBMs wanted a deal in exchange, and drug rebates were born.

Unlike more conventional commercial rebates, prescription drug rebates are invisible to the patient. When a patient fills their prescription, the drug company pays a pre-negotiated rebate to the PBM, providing a discount off the list price. The PBM then passes all or most of that rebate to the health plan; in the latter case, it keeps a cut for itself.

And so the modern pharmaceutical market took shape. Drug manufacturers develop (or acquire) medications. After FDA approval, they produce these drugs. They sell those medicines to wholesalers, who distribute them to individual pharmacies. Health insurers contract with PBMs to determine copays, and the PBMs negotiate rebates with drug companies.

All this determines what a patient pays in the pharmacy when it’s time to pick up their meds.

Over time, the importance of PBMs grew. Breakthrough treatments for all kinds of serious conditions that plague Americans came onto the market, with ever-increasing price tags. The launch of Medicare Part D in 2006 provided prescription drug coverage to the people who use prescription drugs the most: seniors.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, patients paid almost 60 percent of the cost of their medications out of pocket in 1990. That share had fallen to 15 percent by 2018. Insurers, in turn, picked up more and more of the tab, with their share of drug costs doubling from 26 percent in 1990 to nearly 50 percent in recent years.

PBMs expanded their operations to grab a bigger share of the pie. They started operating mail-in pharmacies, cutting out the brick-and-mortar stores, and specialty pharmacies that handle certain high-cost medications. They also merged with one another — so much so that Express Scripts, CVS Caremark, and OptumRx now dominate the PBM market.

And in recent years, PBMs, their pharmacy businesses in tow, have begun reintegrating with the health insurers from which they were spawned. Today, CVS owns the health insurer Aetna, in addition to its own PBM business and its own specialty pharmacy business. Cigna and United Healthcare have purchased Express Scripts and OptumRX, respectively, and their parent companies have their own specialty pharmacies. Those deals gave the insurers a better window into the mysterious finances of the PBMs and let them keep all of the rebates being negotiated with drugmakers.

These business arrangements have created a lot of anxiety among policy experts and lawmakers — and with good reason.

Why PBMs are under scrutiny from lawmakers

The trouble starts here: Nobody outside of the PBMs and drug manufacturers really knows the size of the rebates being negotiated.

PBMs argue that is a necessary condition of their job. If everybody knew the size of the rebates they are securing, they would start to lose their leverage and thus their ability to get a better deal for their customers. But this impenetrability has helped create the image of PBMs as a mysterious conduit in the pipeline between pharma and patients.

“Over time, questions have been raised whether PBMs are overcompensated for their services,” said Stacie Dusetzina, a health policy professor at Vanderbilt University. “The lack of transparency makes it impossible to judge and makes everyone suspicious. There is a dramatic lack of clarity on how their business model typically works.”

PBMs generally make money in one of two ways: Either they earn a percentage of the rebates they negotiate with drug companies on health plans’ behalf or on a per-prescription fee basis paid by the insurer. But because their books are locked in a proverbial black box — even for a publicly traded company like Express Scripts, their contracts with drugmakers are generally considered to be trade secrets — it can be difficult to tell from the outside how a company makes its money.

There is some evidence of clever accounting on the part of PBMs: A 2019 Government Accountability Office report concluded that PBMs kept just 1 percent of rebates, but Christensen interviewed a former PBM employee who said the real share is closer to 20 percent. From the outside, it’s impossible to know which is true.

“No one has clear information about how they’re getting paid, so it’s hard to say if they’re getting paid too much,” Dusetzina said.

The rebate structure also can create perverse economic incentives that could result in patients paying more money for medications. Drugmakers now know that they will have to negotiate rebates with PBMs, which can motivate them to set higher list prices — prices that are eventually borne by some consumers or, in the case of Medicare patients, by the government.

“When the starting price of a drug rises, and the PBM negotiates a rebate, the PBM appears successful,” said Robin Feldman, a law professor at UC Hastings who studies the pharma market. “It’s like a store that raises the price of a coat before putting it on sale.”

PBMs can also now use their contracts to funnel business away from retail pharmacies to the specialty pharmacies they own, creating a potential conflict of interest, and there is some evidence that this practice is becoming more common.

PBMs could also provide a way around federal regulations that require insurers to spend a certain percentage of their revenue on actual medical claims. As the scholars at the Brookings Institution recently wrote, insurer payments to other entities owned by the same parent company — such as PBMs — can still count as medical spending under those rules, even if the money ultimately ends up staying inside the larger business organization.

How a bipartisan Senate deal would affect PBMs

When the drug company Mylan was criticized in 2016 for the EpiPen’s egregious price hikes, Mylan CEO Heather Bresch and other leaders in the drug industry testified before a Senate committee and pointed the finger squarely at PBMs.

“So you get this pressure year after year that tends to escalate the price increases,” Ron Cohen, then the chairman of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, a biotech trade group, told the committee, explaining how the rebates negotiated by PBMs drove up list prices.

Until that hearing, PBMs had been frequently ignored in the US health care discourse. One person who was working at the Department of Health and Human Services at the time told me the CEO’s comments were what brought PBMs to their attention.

In response, those companies have argued that focusing on their business is a distraction from the egregious pricing practices perpetrated by pharmaceutical companies.

“EpiPens are expensive because Mylan raised the price of EpiPens,” Steve Miller, chief medical officer at Express Scripts, said in a 2016 interview. “To blame it on distributors ... is just ridiculous.”

But in the view of many lawmakers and experts, as Sanders articulated at last week’s hearing, both sectors bear part of the blame.

The EpiPen price scandal of 2016 was just one of many controversies (Martin Shkreli, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, the ever-growing cost of insulin, the enormous opening prices of the hepatitis-C cures) that have made drug prices one of Congress’s top priorities in recent years. Last year, lawmakers for the first time authorized Medicare to negotiate prices for a limited number of drugs directly with drugmakers. They also placed a cap on out-of-pocket costs for insulin for people on Medicare.

But Bresch, intentionally or not, also put PBMs on the radar — and seven years later, Congress is on the verge of acting to rein in the industry. Sanders and his Republican counterpart on the health committee, Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, recently announced a deal on legislation that would be the first significant attempt by Congress to address the PBM industry. It is expected to clear the Senate health committee this week.

Experts and lawmakers alike caution that these provisions are a first step. The bill starts chiefly with simply forcing more transparency from PBMs. They would be required to share more information with health plans on prescriptions and discounts; they would also need to disclose information about, for example, any arrangements that could lead to prescriptions being funneled to the mail-order or specialty pharmacies owned by the PBM. They would be required to submit the same information to the federal government too. Another provision would ban the practice of “spread pricing,” in which a PBM charges the health insurer more money for a drug than is paid to the pharmacy to acquire it.

Eventually, the plan is for these measures to be folded into a larger legislative package focused on drug pricing that Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer hopes to bring to the Senate floor in the coming weeks.

Still, reforming PBMs doesn’t fundamentally change a US pharmaceutical market that gives companies carte blanche to set whatever list prices they want for new drugs. It doesn’t affect the gamesmanship that can prevent generic drugs from coming to the market and thereby keeping prices elevated long after the initial patents expire. It also doesn’t change the long-running trend of health plans shifting more of the cost of medical care onto patients through high-deductible plans and other benefit designs.

Some of those issues will be addressed in the legislative package the Senate is pulling together. But others will be part of a later debate — one that Sanders, even as he excoriated PBMs for their worst practices, promised would be coming.

“For anyone here who believes this is going to be end of the work we do here on prescription drugs, I have bad news for you,” Sanders said at his committee’s hearing last week. “This isn’t the end, but the beginning.”

READ MORE  Fursan Hanani outside his home in Khirbet Tana. (photo: Courtesy of Jaclynn Ashly)

Fursan Hanani outside his home in Khirbet Tana. (photo: Courtesy of Jaclynn Ashly)

Israeli military zoning in the West Bank sanctions the demolition of Palestinian structures while green-lighting settler farmsteading. As settlements grow, Palestinians are being pushed underground as they are forced to seek shelter in caves.

Mattresses and blankets are piled in the corner and a dusty mirror is hanging on the cavern’s exterior. “The Israelis can’t reach us underground,” says Hanani, whose permanent, stone home has been razed by Israeli authorities several times over the years. The entrance to this cave has also been dismantled on a few occasions, along with his container homes and tents.

The further Hanani retreats into these ancient caves that protrude from the hills in Khirbet Tana, the safer he feels. There are some forty families who reside in Khirbet Tana, consisting of about two hundred fifty people, many of whom are closely related. They are shepherds, a traditional livelihood practiced here for generations.

For many decades, these shepherds would follow the climatic patterns of the West Bank, migrating seasonally to Khirbet Tana during the winter months to graze their sheep and goats. During the summers, they would gradually return west to Beit Furik where the weather was cooler and the meadows remained green. Over the years, some built permanent stone homes in Khirbet Tana for their families and developed small-scale agricultural farms.

But these shepherds’ traditional way of life is now endangered by Israel’s more than half century military occupation of the West Bank. Just a few years after the Israeli army took control of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip in 1967, the area of Khirbet Tana was repurposed for Israeli military training and declared a “firing zone.” This was in spite of the fact that Palestinian shepherds had been dependent on these lands to sustain their livelihoods for generations, long before Israel occupied the region.

Scores of Palestinians have been arrested for entering these areas and, over the decades, the village of Khirbet Tana has been demolished on numerous occasions. Tired of constantly having to rebuild what the Israelis destroyed, these Palestinians decided to move their lives underground, where they say the Israeli army more or less leaves them alone.

Israeli policy in the region has decimated many of these traditional shepherding communities. Khirbet Tana is now the last remaining herding hamlet in the area of Beit Furik — and among the last in the West Bank.

Yet, Israeli settlements in the West Bank, considered illegal under international law, have been permitted to expand into these closed military zones. As they continue to grow, Palestinians in Khirbet Tana are being pushed further and further underground.

“This is my land and home,” Hanani says, squinting his eyes as he scans the rolling hills surrounding him. “I need space for my goats and sheep. But every time we build anything, we are forced to wait in fear for the day the Israelis come to destroy it.”

“So we also feel safer in the caves,” he continues. “It’s hard to sleep in the tents because we’re always worried that Israelis will come in the night and demolish them.”

Land Grabs

“This is the cave where I was born,” says sixty-eight-year-old Muhammad Tawfiq Nasasra, pointing at a cavern opening in the ground. He balances himself on a walking stick and slowly strolls across the village’s rocky terrain.

According to residents, their ancestors traditionally resided in caves. Without cars or roads, they relied on donkeys for transportation, making it impractical to carry construction material to this highly remote area. The villagers have also long used tents for shelter, which can easily be moved and transported as they follow behind their animals grazing on the surrounding hills.

Israel declared the village a firing zone in the 1970s — unbeknownst to the Palestinian residents. According to Dror Etkes, founding director of the Israeli rights organization Kerem Navot, the process of declaring hundreds of thousands of acres of land closed for military zones started just a few weeks after Israel’s occupation of the West Bank in 1967.

Close to 436,141 acres of the entire West Bank are today defined by the Israeli army as closed military areas for various purposes, of which 53 percent are designated as firing zones. These vast areas mainly served the rural and Bedouin shepherding population. The traditional bounds of their pasturage reached from east of the central range that lies west of the Jordan Valley and stretches from Yatta in the southern West Bank to Tubas in the northeastern West Bank.

“There was no Israeli military infrastructure that existed in these areas at this point that could have allowed Israel to convert these lands into training areas,” Etkes tells me. “So it is clear that the idea behind declaring these areas as closed military zones was and still is mainly a political tool to limit the ability for Palestinians to access very large parts of the West Bank.” A result of this land grab is the creation of massive reserves for the future expansion of settlements.

Ariel Sharon, the late Israeli prime minister, said it himself in 1981. In a forty-year-old document found in the Israel State Archives, the then minister of agriculture proposed at a meeting of the Ministerial Committee for Settlement Affairs that land in the South Hebron Hills be allocated to the Israeli army for live-fire training. Sharon put forward the idea in light of the “expansion of the Arab villagers from the hills.”

“We have an interest in expanding and enlarging the shooting zones there, in order to keep these areas, which are so vital, in our hands. . . . Many additional areas for training could be added, and we have a great interest in [the army] being in that place,” Sharon added.

According to Nasasra, a road was constructed in the 1980s that linked Khirbet Tana to the town of Beit Furik. This allowed the residents to construct homes from stone and cement blocks for the first time. About thirty stone homes were built.

Nasasra says life began to dramatically change in the 1990s, when the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Israel signed the Oslo Accords. Following the signing of Oslo II in 1995, the West Bank was divided into three distinct areas, A, B, and C.

Areas A and B, where the Palestinian Authority at least partially controls civil and security matters, comprise about 39 percent of the area of the West Bank. The rest — 61 percent of the West Bank — was designated as Area C, where Israel retains full civil and security control. All of Israel’s some two hundred settlements — where more than half a million Israelis live in violation of international law — are located in Area C.

Khirbet Tana’s lands also fell under Area C, overturning the lives of its residents. Palestinian construction in Area C is prohibited, unless Israeli-issued building permits are in hand. But such permits are nearly impossible for Palestinians to obtain. They are therefore left with no alternative but to construct buildings without proper documentation, which condemns them to a perpetual cycle of reconstruction every time Israeli officials show up to destroy their buildings.

According to the United Nations, last year, Israel demolished or seized 953 Palestinian structures throughout the West Bank. This is the highest number of demolitions carried out since 2016. As a result, more than one thousand Palestinians have been displaced.

Having been one of the first Palestinian families to construct a stone home in Khirbet Tana in 1982, Nasasra says his family was deeply proud of the structure. But soon after the Oslo II Accord was signed, Israeli bulldozers came and demolished it, he says.

Nasasra leads me to a large heap of stones scattered across the ground. It is all that is left of his family’s old home that was demolished nearly thirty years ago.

Left With Nothing

Yusef Hanani, thirty-three, and his family built a five-room stone house in 2000. “It was the first time I ever had a modern house,” Yusef says. “It made me very happy. I loved that house.” It also cost him and his father 100,000 Israeli shekels (about $27,500) — a total that took the family years to save.

But the house only stood for less than five years.

In July 2005, the Israeli civil administration, the military unit responsible for implementing Israel’s civilian policies in the West Bank, demolished nearly all the village’s buildings. It further blocked up the entrances of the caves — an attempt to forcibly remove the shepherds from the land.

Yusef says he tried to intervene in the demolition of his family’s home. “But the soldiers took me, tied me up, and pointed guns at me,” he says. “I felt very bad. It took us our whole lives to save up that money. They left me with nothing. ”

Israeli human rights group B’Tselem has documented Khirbet Tana’s misfortunes.

As they note, even though the firing zone had been inactive for at least fifteen years, Israeli authorities demolished the homes and animal pens of Palestinian residents owing to them not having Israeli-issued permits.

According to Etkes, after the Oslo agreements, “Israel basically moved its military training system mainly to the Naqab, in the southern part of the country. So the military bases that were used in the later ’70s, ’80s, and early 1990s for training have in most cases been dismantled.” This includes Firing Zone 904A, where Khirbet Tana is located.

“The bottom line is that the vast majority of this area has not been used for military training for thirty years or so,” Etkes continues. “And that’s true for many other areas declared as closed military zones for training.” According to Kerem Navot, about 80 percent of the overall area declared closed for military training purposes is not actually used for training.

Army training is sometimes carried out in zone 904A, albeit very rarely. According to Etkes, “These areas are still training zones so the army has to come and do something once in a while,” he says. “But it’s very rare they do it.”

“The vast majority of the area is not being used,” he continues. “When they do come, they use a very small piece of the overall training zone, and it’s not even close to Khirbet Tana.”

A Backyard for Settlements

Over the years, Israeli authorities have carried out numerous demolitions in Khirbet Tana, destroying homes, livestock pens, water cisterns, and tents. Only the local mosque, which was built in the Ottoman era more than a century ago, has remained standing.

The community’s local school, built with funding from the European Union, has not been spared; Israeli authorities have demolished it at least three times. The school was rebuilt about four years ago and now consists of a metal container, with a set of swings and a single slide in front. It has an active demolition order against it and could be demolished any day, residents say.

For about a decade, residents in Khirbet Tana petitioned the Israeli High Court of Justice (HCJ) seeking to have the civil administration prepare a master plan for the village instead of demolishing their homes. By law, the Israeli army is permitted to remove people from a shooting zone unless they are permanent residents. The state claims that these Palestinians are in fact nomads and not permanent residents of Khirbet Tana; therefore, they are not protected by the law.

In 2015, the HCJ concluded the legal proceedings and accepted the state’s position that the structures were illegally constructed, due to the shepherds residing in Khirbet Tana seasonally — overlooking the fact that some continue to reside there permanently. In the near decade since the HCJ ruling, the residents of Khirbet Tana have been trapped in a vicious cycle of displacement and frequent demolitions.

This ruling was “a clear expression of the narrow interpretation that the government authorities, with the backing of the HCJ, give to the concept of ‘permanent residency’ in this context,” Etkes has stated. “This interpretation strikes a mortal blow to the economy and tradition of many Palestinian communities that have earned their livelihood from shepherding for generations.”

Numerous other petitions have been submitted by Palestinians through the HCJ against evictions in these training areas. They have all been met with the same state response.

Most recently, in May last year, the HCJ ruled to reject a petition from families of about eight herding hamlets in Masafer Yatta, the Arabic name for the sprawling hills south of Hebron in the southern West Bank. The families are among thirteen hundred Palestinians living in an area Israeli authorities declared a firing zone since the 1980s.

These communities are now facing immediate expulsions from their lands and homes.

Carefully treading over the crushed stones of his family’s former home, Nasasra’s thirty-two-year-old son, Moiyad, leads me to a large hole protruding from a rocky hill — one of the two underground caves the family has now moved into. Over the years, they have expanded the interior of the cave to create more space as their family grew, enlarging the living quarters.

“If God wills, one day we will be able to build again above the ground,” Moiyad says. “But for now, we have no choice but to stay in these caves until that day comes.”

The sloping hills of Khirbet Tana stretch out in all directions; they seem almost untouched by human activity. Palestinians are prohibited from building in this area — and are literally forced underground — but the vast area of Firing Zone 904A has “become a backyard for the settlement of Itamar and its outposts,” Etkes says.

Two Sets of Rules

Itamar was established in 1984 on lands confiscated from nearby Palestinian villages — including Beit Furik. It now has a population close to fifteen hundred. Two of its outposts, legally dubious bulkheads often serving as extensions of government-approved settlements, are located within Firing Zone 904A. While Israel considers its settlements in the West Bank legal, the outposts are considered illegal under Israeli domestic law. Despite this, they often receive tacit government support or even public funding. Many are also retroactively legalized.

Nestled in between the hills a few kilometers from Khirbet Tana, one can view a small livestock farm in the distance. It is named Yzhak Basus Farm, after the Israeli who established it about two years ago. His livestock pen appears as a blackened square on the desolate landscape.

This is one of the four Israeli shepherd outposts established around Khirbet Tana, some of which have been settled by individual Israeli families. According to Etkes, these outposts are strategically located to eventually take over the vast majority of Firing Zone 904A.

“Hill 777,” also referred to as Givat Arnon, is considered an outpost of Itamar and was established in the late 1990s. It is located on the edges of the firing zone, but still within its borders. The Itamar Cohen Farm, settled in 2014 and which Etkes says is among the West Bank’s most violent outposts, is centrally located inside the middle of the firing zone. Yzhak Basus Farm is located outside the firing zone, close to its border with the adjacent Firing Zone 904.

According to Etkes, the purpose of the Itamar Cohen Farm outpost is to extend its control over the territory stretching from the outpost to Hill 777, as well as the region between it and the Yzhak Basus Farm. Itamar Cohen is already connected to Hill 777 with a road. “The idea is to connect the entire system of the outposts that are east of Itamar with the larger settlement of Itamar,” Etkes adds. “Itamar Cohen is one link that connects this entire chain of outposts with the Alon Road [Israeli settler bypass road built in the West Bank] to the east.”

Etkes explains that these shepherd outposts are part of a larger strategy employed by Israel since the 1970s, in which tens of thousands of acres of open areas in Area C are expropriated by Israeli authorities through the allocation of “grazing lands” to shepherd outposts and farms. In recent years, “the phenomenon mushroomed in terms of area size, resources invested, and destructive repercussions for the Palestinian communities.”

According to a report published last year by Kerem Navot, there are currently seventy-seven farm outposts in the West Bank, designated for sheep and cattle grazing. The great majority of these outposts was established over the last decade and consists of a territory that totals some sixty thousand acres — a little less than 7 percent of the entire Area C.

The report notes that about twenty thousand acres, or a third of the total area seized by settlers through grazing, are located within areas declared by the Israeli military as “firing zones,” on the eastern edges of the West Bank. The report states that “these outposts are the spearhead of a violent land-grabbing system, well planned and generously funded by various state and quasi-state bodies,” which include the Israeli military, the Israeli civil administration, regional and local settler councils, the World Zionist Organization’s Settlement Division, the Ministries of Agriculture and Education, and the new Ministries of Settlement and Intelligence.

“All are preoccupied with what has recently been referred to as the ‘Battle for Area C,’ meaning the coercive transfer of Palestinians from the area . . . and their enclosure in isolated enclaves,” the report continues. “They are designed to uproot Palestinian grazing and farming communities from public or private lands, and turn them into lands that only settlers can use.”

In this process, settler violence becomes an essential tool to promote this objective. According to Kerem Navot, the farm outposts have in recent years seen some of the most violent incidents in the West Bank. Rights groups have long documented the use of settler violence against Palestinians and the role of violence in Israel’s long-term goal of taking over Palestinian lands.

According to B’Tselem, “Settler violence against Palestinians is part of the strategy employed by Israel’s apartheid regime, which seeks to take over more and more West Bank land.”

“The state fully supports and assists these acts of violence, and its agents sometimes participate in them directly,” the group states. “As such, settler violence is a form of government policy, aided and abetted by official state authorities with their active participation.”

Consequently, countless incidents involving threats, harassment, and assaults on Palestinian farmers and shepherds have occurred around these outposts in recent years, often in the presence and even with the full support of military or police forces.

Seeking Safety Underground

“Why can he live and build here, but we can’t?” Nasasra asks, pointing to the Yzhak Basus Farm in the distant valley. “We were here before them. But he is Israeli and we are Palestinian — that’s the only difference.”

According to Nasasra, the family on the Yzhak Basus Farm often calls the Israeli army if the Palestinians’ sheep or goats venture toward that area. Hanani tells me that he had once farmed wheat and barley, but about ten years ago the settlers from another farm began attacking him if he attempted to access his lands.

“Since then, I haven’t been able to grow anything,” Hanani says. “I lost access to all that land. There’s nothing that I can do about it. They have guns and an army protecting them. How can I defend myself against them? We are powerless here.”

Etkes tells me that while the Israeli government will likely adjust the area of Firing Zone 904A in the future to create the necessary conditions to legalize the outposts located there, it has “no interest in legalizing Palestinian villages or hamlets.” Hill 777, which is located inside 904A, was one of nine settler outposts that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu approved for legalization in February.

“This whole area [of Khirbet Tana] is really the best example of how an area originally declared a closed military zone has been gradually taken over by settlers,” Etkes says.

As these outposts are permitted to grow and expand, Yusef has been retreating deeper underground. He proudly shows off the cave he has extended into a comfortable home for his wife and three small children. It was after his stone home was destroyed in 2005, and his container home shortly thereafter, that he sought refuge in the cave.

It took him about four years to finish constructing and renovating the cave, only working during the safety of night. “You cannot work during the day,” Yusef says, standing by the cave’s entrance and puffing on a cigarette. “We are scared that if the army hears us they will come to stop us. So we have to make sure we don’t make too much noise.”

He has painted the doorway light blue and constructed a window on the cave’s ceiling to bring more light into the dark underground cavern. The family also repurposed and expanded an underground well to house their goats and sheep — along with creating an impressive underground water system. They used small tools, chiseling away at the rocks for many nights until the cavern grew into a larger space and channels were dug that could transport the water.

“It makes me angry that we are still living in the same way our grandparents were,” Yusef says, taking a long drag from his cigarette and shaking his head in frustration. “We should be more developed by now. We should at least have permanent homes to live in. None of this is fair. But at least we have these caves to shelter us from the demolitions. If it wasn’t for these caves none of us would be able to survive here.”

READ MORE Fernando Trujillo, right, has studied Amazon river dolphins since he was a college student in the 1980s. In 1993, he co-founded the Omacha Foundation, which focuses on conserving animals and ecosystems. (photo: Andrés Cardona/The Washington Post)

Fernando Trujillo, right, has studied Amazon river dolphins since he was a college student in the 1980s. In 1993, he co-founded the Omacha Foundation, which focuses on conserving animals and ecosystems. (photo: Andrés Cardona/The Washington Post)

“The dolphins!” Fernando Trujillo exclaimed, startling the team. “They’re right there!”

The 15 passengers swiveled their heads and the captain sped to the spot. It was a rare sight, an endangered species emblematic of the Colombian Amazon, considered sacred by the region’s Indigenous communities: the pink dolphins.

And here were six of them — all females, including four calves. These particular dolphins lacked the light pink hue found in some members of the species. But still, they mesmerized.

The team leaped into action: Members covered each dolphin’s eyes to reduce the stress to come. They paid close attention to their breathing. They kept their bodies wet at all times, except for their blowholes, which Trujillo would monitor and protect.

Trujillo, who has devoted decades to researching these dolphins, had brought his team here at the confluence of the Meta and Orinoco rivers to take blood and tissue samples. They would study their physical health. But through them, they hoped to learn much more — including how the mining of gold and other extraction activity is threatening human life here.

In the Amazon, river dolphins are the canaries in the coal mine — “the sentinels of the aquatic ecosystems,” said Jimena Valderrama, 27, a veterinarian who has worked with Trujillo for three years: “They accumulate what we dispose of in the rivers.”

Among the scientists’ biggest concerns was the dolphin’s exposure to mercury, a heavy metal used in mining that can cause lethal damage to the brain, heart and kidneys, and what it might suggest about the exposure of the people, near and far, who eat fish from the river.

Tests revealed that three of the dolphins had an average of 3.45 micrograms of mercury per liter of blood — a level Trujillo called “alarming.”

“If we find a fish with 1.2 micrograms … we shouldn’t eat it,” he said. But he’s seen worse: The highest mercury levels in river dolphins in all of South America have been found here in the Orinoco Basin, he said, where they can surpass 30 micrograms.

It isn’t just Colombia. High mercury levels have been noted in the dolphins of Florida’s Everglades and the dolphin-hunting town of Taiji, Japan.

The Orinoco River, which divides Venezuela and Colombia in the Amazon, has been polluted by mining for gold and coltan in the Orinoco Mining Arc. The region has been designated for gold extraction by Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro but is controlled largely by illegal armed groups. To extract the gold, miners often use mercury. The World Health Organization identifies mercury as one of 10 chemicals “of major public health concern.”

“If the Mining Arc is to go on, it’d be better if all’s done legally, controlled and monitored,” said Leonardo Sánchez, a researcher with the Sotalia Project in Venezuela. Around Venezuela’s Lake Maracaibo, dolphins are a traditional dish. The locals there, Sánchez laments, have taken to cooking them with coconut to reduce the iron flavor.

When mercury reaches rivers, it’s ingested by fish that are eaten by humans as far away as Bogotá.

Studies on mercury levels in human populations near the Orinoco River have been limited, Trujillo said. When The Washington Post asked about his own level, he got tested — and found it was more than 10 times that of the dolphins: 36.25 micrograms.

After 30 years of studying dolphins in these waters, Trujillo, too, has been poisoned.

Trujillo, 55, has studied Amazon river dolphins since he was a college student in the 1980s. In 1993, he co-founded the Omacha Foundation, which focuses on conserving animals and ecosystems. (In the language of the Indigenous Tikuna people, “Omacha” means the dolphin that turned into a person.)

He has worked with organizations including the World Wildlife Fund, the Whitley Fund for Nature and, with other scientists from the Orinoco and Amazon regions, the South American River Dolphin Initiative. Recognized as one of the few global authorities on river dolphins, he has become a familiar face in documentaries and features on the Amazon region.

Trujillo began investigating mercury levels in this region some 15 years ago. His first tests, on fish for human consumption from the Amazonian Trapeze, the stem of Colombia that extends south between Peru and Brazil, showed high levels. Fish from the Orinoco river basin yielded similar results. Then it was the dolphins’ turn.

“That’s why dolphins are an indicator: If they have a problem, so do we, as we share food habits,” said Saulo Usma, freshwater program coordinator of the World Wildlife Fund for Colombia. “What’s worse, even though dolphins are giving us this information, authorities from both countries are not assessing if the fish we eat contain mercury.”

Trujillo’s efforts to sound the alarm have at times put his own life in danger. His warning about high mercury levels in catfish on Colombian television in 2021 drew death threats. He took to wearing a bulletproof vest and engaging a bodyguard when traveling in the Amazon.

Trujillo says a politician once told him that it would be impossible to protect the whole river. “So tell us which parts we must protect to preserve the dolphins,” the politician said.

Trujillo declined to identify the politician. But he hoped his trip to the Orinoco and Meta rivers might help answer the question. If the six dolphins that the team safely captured are related — the Omacha Foundation is awaiting the results of genetic tests — planners might be able to develop conservation efforts directed at female dolphins.

Individual females don’t range as widely as males — they linger in locations where they can keep their food and offspring safe. It’s particularly important, Trujillo said, to identify and protect these areas: “If those places are deteriorated, the calves might not survive.”

Trujillo has led more than 40 expeditions worldwide. This was the fifth binational expedition — he was accompanied by government officials from Colombia and Venezuela. His hope was to get both governments to work together to protect the rivers.

The dolphins, Trujillo said, make good “ambassadors.” Human affection for the animals can lead government officials and the general public to pay attention to the broader issues confronting the Amazon.

“If we stop deforestation, which releases the natural mercury in the Amazon soil, and work on clean mining technologies, we can have a better future,” he said. “All we need is determined political actions.

“The mercury problem has a solution, and that’s what’s sad about it.”

Before this trip, Trujillo said, he was afraid to measure his own mercury levels.

There’s no consensus on how much mercury exposure for humans is too much. Some authorities believe levels above 5 micrograms per liter should raise alarms; others say levels below 20 can be considered normal. But either way, Trujillo’s results are cause for concern.

On receiving his report, Trujillo feared for the people, especially in Indigenous communities, who live along the riverbank. Then he thought of the people across Colombia and beyond who eat fish from the Orinoco or Amazon rivers. “Everybody should know their mercury levels,” he said.

But in Puerto Carreño, the small city at the confluence of the Meta and Orinoco rivers, there’s no lab to run blood tests for mercury. The dolphins’ samples were flown hundreds of miles for processing. In Colombia, only a few entities are certified to perform the test.

Trujillo is now trying to diminish the impact of the mercury in his body. He has met with a toxicologist and has begun to follow a strict diet rich in selenium, which can reverse its toxic effects. He avoids eating fish and shellfish.

But he knows the metal in his blood could someday cause great harm to his nervous system.

“I know I hold a ticking bomb inside me that can go off at any moment.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.