Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

“Hey Dalton - Andy Fiffick here,” he said. “We wrapped up some morning things quicker than we thought, so if you want/can come earlier than 1:30 we’re available.”

The state legislature had begun the crucial task of redrawing voting district lines after the 2020 census. Even small changes in the lines can mean the difference between who wins office, who loses and which party holds power. As the process commenced, Clyburn had a problem: His once majority Black district had suffered a daunting exodus of residents since the last count. He wanted his seat to be made as safe as possible. Republicans understood the powerful Black Democrat could not be ignored, even though he came from the opposing party and had no official role in the state-level process. Fortunately for them, Clyburn, who is 82 and was recently reelected to his 16th term, had long ago made peace with the art of bartering.

Tresvant made his way to the grounds of the antebellum Statehouse, a relic still marked by cannon fire from Sherman’s army. The aide carried a hand-drawn map of Clyburn’s 6th District and presented it to Fiffick and the other Republican committee staffers who were working to reconfigure the state’s congressional boundaries.

Some of Tresvant’s proposals appealed to Republicans. The sketch added Black voters to Clyburn’s district while moving out some predominantly white precincts that leaned toward the GOP. The Republicans kept Tresvant’s map confidential as they worked through the redistricting process for the following two months. They looped in Tresvant again near the end, according to public records obtained by ProPublica.

The resulting map, finalized in January 2022, made Clyburn’s lock on power stronger than it might have been otherwise. A House of Representatives seat that Democrats held as recently as 2018 would become even more solid for the incumbent Republican. This came at a cost: Democrats now have virtually no shot of winning any congressional seat in South Carolina other than Clyburn’s, state political leaders on both sides of the aisle say.

As others attacked the Republican redistricting as an illegal racial gerrymander, Clyburn said nothing publicly. His role throughout the redistricting process has remained out of the public view, and he has denied any involvement in state legislative decisions. And while it’s been clear that Clyburn has been a key participant in past state redistricting, the extent of his role in the 2021 negotiations has not been previously examined. This account draws on public records, hundreds of pages of legal filings and interviews with dozens of South Carolina lawmakers and political experts from both sides of the aisle.

While redistricting fights are usually depicted as exercises in raw partisan power, the records and legal filings provide an inside look that reveals they can often involve self-interested input from incumbents and backroom horse trading between the two parties. With the House so closely divided today, every seat takes on more value.

South Carolina’s 2021 redistricting is now being challenged in federal court by the NAACP. The organization contends that Republicans deliberately moved Black voters into Clyburn’s district to solidify their party’s hold on the neighboring swing district, the 1st. A three-judge federal panel ruled in January that aspects of the state’s map were an unconstitutional racial gerrymander that must be corrected before any more elections in the 1st District are held.

But Clyburn’s role already has complicated the NAACP’s case. The judges dismissed some of the group’s contentions partly because Clyburn’s early requests drove some of the mapping changes. The Republicans are now appealing the ruling to the Supreme Court, which has yet to decide if it wants to hear oral arguments in the case.

The redistricting process was the first South Carolina has undertaken since a series of Supreme Court rulings made it easier for states to redraw their districts. In 2013, the high court significantly weakened the Voting Rights Act, removing South Carolina and other Southern states, with their history of Black disenfranchisement, from Department of Justice oversight. And in 2019, the Supreme Court opened the door to more aggressive gerrymandering by barring federal court challenges on the basis of partisanship. But it can be illegal to draw lines based on race. Republican gerrymanders in Florida, Texas and several other states have recently been challenged for targeting Black voters.

The fight over the South Carolina redistricting has exacerbated racial wounds in a state where the growing white population now accounts for about 68% of residents, up from 66% a decade ago. Driven by the immigration of white retirees and a slow emigration of Black people, the state’s Black population has dropped over the years to just over a quarter of its 5.2 million residents. The GOP now controls all major state elected offices except for Clyburn’s seat.

Clyburn’s role highlights an underbelly of the redistricting process: In the South, Black Democratic incumbents have often worked with Republicans in power to achieve their own goals.

Few state Democrats will criticize Clyburn by name on the record. Bakari Sellers, 38, a former state Democratic lawmaker who once served on the redistricting committee, said, “There is a very unholy alliance between many Black legislators and their Republican counterparts in the redistricting process.” Clyburn’s district “is probably one of the best examples.” Moving that many Black voters into Clyburn’s district meant “we eliminate a chance to win” in other districts, he said.

“I’m not saying that we could win, but I’m saying we could be competitive, and people of color, those poor people, those individuals who have been crying out for so long, would have a voice,” Sellers said.

Clyburn speaks in the deep baritone of a preacher’s son, but his voice rises in anger when the subject turns to criticisms of his involvement in redistricting. Unfounded, he says.

In an interview, Clyburn said the redistricting plan signed by the Republican governor in early 2022 proves he did not get all that he wanted, mainly because his district lost its majority Black status. On questions about Tresvant’s work, a Clyburn spokesperson acknowledged that the office had “engaged in discussions regarding the boundaries of the 6th Congressional District by responding to inquiries” but did not answer detailed follow-up questions about his role. Tresvant did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

“Any accusation that Congressman Clyburn in any way enabled or facilitated Republican gerrymandering that wouldn’t have otherwise occurred is fanciful,” Clyburn’s office said in a statement, calling the notion a “bizarre conspiracy theory.” Clyburn agrees with the decision of the three-judge panel and “hopes it will be upheld.”

Backroom Deals

Clyburn’s district, the 6th, itself resulted from what political experts would later describe as a racial gerrymander. After the 1990 census, a federal court imposed a plan that gave South Carolina’s Black population, then about a third of the state, a fair shot at electing a member of Congress. It hadn’t done so since 1897.

The 6th’s boundaries brought in Black people from across the state to create a crescent-shaped district. Black people made up almost 6 in 10 residents. National Democratic Party strategist Bill Carrick, then a South Carolina campaign consultant, said race guided the GOP. “It was like the Republicans decided, ‘Let’s see how many African Americans we can put into one district — instead of our own,’” he said.

This redistricting technique is known as “packing.” Packing can be a double-edged sword, giving underrepresented communities a voice but also limiting them to one — and only one — member of Congress. Clyburn, the first Black person in modern times to head a South Carolina state agency, won the seat in 1992. He rose to prominence in Washington, climbing to the post of House majority whip by 2007. His 2020 endorsement helped Joe Biden seal the Democratic presidential nomination, and he was recently named a co-chair of Biden’s 2024 campaign.

Clyburn’s stature within the state was unparalleled. He had learned early in his career the value of backroom negotiations, at first dealing with staunch segregationists running the state government. His role in Washington required negotiating with GOP leaders to pass legislation though he would publicly criticize them when they rejected Democrat’s initiatives, like new voting rights proposals.

He is best known back home for delivering federal money. Clyburn’s name is emblazoned on taxpayer-funded structures all over the state, including a Medical University of South Carolina research center and an “intermodal transportation center” (otherwise known as a bus station) in his hometown, Sumter.

Clyburn also was willing to help local Republicans. When the family business of George “Chip” Campsen, a top GOP state leader, had a dispute with the National Park Service over how much it owed the federal government, Clyburn co-sponsored a Republican lawmaker’s bill to pressure the service into mediation. The parties then settled in 2002 on favorable terms to the Campsen family company. Clyburn’s office said he did nothing improper. (Campsen did not respond to a question about the deal.)

Clyburn’s ties with Republicans have come in handy during the previous redistricting battle. Clyburn has repeatedly angled to keep a majority Black constituency, according to documents and political observers.

Redistricting is meant to follow clear principles. Each congressional district’s population must be as similar as possible. Maps are supposed to be understandable, with counties and cities kept whole and lines following natural boundaries, like rivers or highways. And the process is designed to be transparent, guided by public input.

But it has rarely worked out that way. Despite a recent history of moves to disenfranchise minority voters, Republicans have sometimes been able to capitalize on individual politicians’ self-interest. In the early 1990s, then-Republican National Committee counsel Benjamin Ginsberg seized upon Black disenchantment with white Southern Democrats’ gerrymanders to forge what has come to be known as the “unholy alliance” between the RNC and Black elected officials. Ginsburg told the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation in 1990 that the RNC would share its redistricting tools with minorities as part of a “natural alliance born of the gerrymander.” The upside for the Republican party is that Black voters in Southern states could be limited to as few seats as possible.

In 1994, the GOP took over the House and the Congressional Black Caucus reached its largest membership since Reconstruction. Redistricting “increased the political power of both groups,” said David Daley, author of “Ratf**ked,” a book on gerrymandering that delves into the history of the alliance between the GOP and Black Southern Democrats. “Republicans regained control of the House, and the Congressional Black Caucus grew to its largest numbers since Reconstruction.”

Clyburn is part of a generation of Black officials who lived through the Jim Crow era and cherished the protections of the Voting Rights Act. But many politicians who agree about the importance of the act say that the notion that Black politicians need majority Black districts to get elected is outdated. Because he’s been in office so long, “Jim Clyburn could win reelection with 20% Black voters,” said former Rep. Mel Watt of North Carolina. “He’s trying to protect the district for the candidate coming after him.”

Despite state and local resistance, the number of elected Black officials in South Carolina increased from 38 in 1970 to 540 in 2000 and continued growing. Yet complaints continued to flood into the Justice Department about gross abuses of voting rights, including biased handling of redistricting.

The last congressional redistricting overseen by the Justice Department in South Carolina was in 2011. Then, as now, the state’s population was booming, and it had gained another congressional seat, which both parties hoped to claim. As is the case today, Republicans controlled the legislature. The Democrats, however, could rely on the Justice Department, which had to preapprove the plan, to prevent gross abuses.

Both Clyburn and the NAACP were among those who publicly submitted their own maps as part of the state’s legal submission to the Justice Department. Clyburn’s map suggested that his district include a Black voting age population of nearly 55%, a higher level than what the NAACP’s map recommended.

Some Democrats proposed moving Black voters out of Clyburn’s district to create a new district, with the hope that the party could elect a second member of Congress. The Republican House speaker blocked the efforts.

Behind the scenes, some lawmakers believed Clyburn was working with the speaker. On a visit to Columbia, the capital, Clyburn went to the House map room and made suggestions to protect his position, according to a nonpartisan former House staff member, who asked not be named because he was not authorized to discuss his work.

During the process, Clyburn met privately with then-Republican state Rep. Alan Clemmons, head of that year’s redistricting panel, according to an account Clemmons later gave to local media. Clemmons said Clyburn had Tresvant act as his “eyes and ears,” the same role that he would take on in 2021. Tresvant “would request specific businesses and churches be included in Clyburn’s district,” according to a 2018 report by The Post & Courier of Clemmon’s account.

Clemmons, now an equity court judge, declined to comment, citing the judicial ethics code.

The 2011 redistricting plan also prompted a federal lawsuit, which unsuccessfully challenged Clyburn’s district as an illegal racial gerrymander. Clyburn did not testify, but in an affidavit, he accused Republicans of making “an intentional effort” to decrease the political influence of Black people by packing them into a single district. He said nothing about his own behind-the-scenes negotiations with Republican leaders.

The 2021 Strategy

Ten years later, Clyburn followed a familiar strategy when Republicans began redistricting again. For the first time, the Justice Department had no oversight role. This time, however, none of his actions were public.

Clyburn’s district had lost about 85,000 people. Each new district had to be drawn to represent 731,203 people. One obvious place to look for additional constituents would be the 1st District, just to the southeast along the coast. That district was overpopulated by almost 88,000. The First District was the last remaining swing district, with a history of tight races. In 2018, a Democrat had won by about 4,000 votes. Two years later, a Republican, Nancy Mace, won it by about 5,000. If the GOP could remove enough Black or Democratic voters from that district, it could give the party a lock on the seat.

The map Clyburn’s aide Tresvant had quietly brought to the GOP at the beginning of the 2021 process included suggestions that would help both Clyburn and the Republicans. His map gave his boss a larger portion of heavily Democratic Charleston County, drawing from Mace’s district. Clyburn’s suggested lines reflected a move of about 77,000 new people to his district, according to an expert who analyzed the maps for ProPublica.

Not every request of his was about race. Clyburn also sought to move an additional 29,000 people into his district from Berkeley County, which he split with Mace. Berkeley is a fast-growing area, adding white voters, but is also home to some of the state’s largest employers.

Clyburn didn’t only suggest adding Democratic voters. He was also willing to give up pockets of his district where elections were trending Republican. One such proposal would help Republicans seal control of the 1st. Clyburn suggested giving up about 4,600 people in Jasper County, an area that was trending Republican as white Northern retirees relocated there.

During the NAACP’s trial, some Republican senate aides said they did not rely on Clyburn’s map. But the staffer for Senate Republicans who was chiefly responsible for redrawing the lines testified that he used it as a starting point. And then the GOP went further. As the redistricting plan made its way through the legislature, Republicans further solidified their hold on the 1st District. Clyburn monitored their progress in calls to Democratic allies, according to two state senators who spoke with him during the period.

A plan proposed by Campsen, the state senator whose family company Clyburn helped years earlier, moved almost all of Charleston County’s Black and Democrat-leaning precincts to Clyburn. The shift gave Clyburn the city of Charleston, where he had deep connections, and consolidated the county’s major colleges and universities into his district, a political plus. The new borders for Clyburn gave him a number of small pockets of Black voters, including about 1,500 in Lincolnville, which juts out of the election map like an old-fashioned door key. “The congressman was hoping to get Lincolnville years and years ago” and finally succeeded in 2022, said the town’s mayor, Enoch Dickerson.

As a result of Campsen’s plan, the Black voting-age population of the 1st District fell to just over 17%, the lowest in the state. In the 2022 election, Mace beat her Democratic opponent by about 38,000 votes — a 14 percentage point landslide, up from her 1 percentage point in the previous election.

Clyburn said nothing publicly as some Democrats in Charleston County, led by former Rep. Joe Cunningham, protested Campsen’s plan. On the Senate floor, Campsen praised Clyburn and said Charleston County would be well served by having both Clyburn and Mace looking out for its interests.

“Jim Clyburn has more influence with the Biden administration perhaps than anyone in the nation,” Campsen said.

As Clyburn monitored the debate, Fiffick kept Tresvant in the loop, texting him again on Jan. 14, 2022, to share a link to the redistricting webpage. It’s unclear why Fiffick sent it.

Campsen’s plan was approved by the legislature and signed by the governor Jan. 26, 2022.

In the end, Clyburn didn’t get everything he wanted. Republicans moved all of rapidly growing Berkeley County to the 1st District. The percentage of Black voters in his district has dipped below 50%, the threshold he long sought to preserve.

The congressman soon got to work serving his constituents. Shortly afterward, Clyburn had Lincolnville added to a federal program that protects historic stops along the Gullah Geechee trail. In the 2022 election, Clyburn won 62% of the vote, lower than the 68% he won in 2020 but comfortable nonetheless.

Consequences

Soon after the new redistricting plan went into effect, the NAACP pressed ahead with its lawsuit against state Republican leaders, charging that many congressional mapping decisions were based predominantly on race. The case dealt with more than just the changes in Mace’s district that had an impact on Clyburn.

A three-judge federal appeals panel ruled that the plan’s division of the 1st and 6th districts was an unlawful racial gerrymander aimed at creating “a stronger Republican tilt” in Mace’s district. The court said that the movement of about 30,000 Black voters into Clyburn’s district was “effectively impossible” without racial gerrymandering.

But the court knocked down some of the NAACP’s claims. In several cases, it said, Clyburn had requested the mapping changes. The NAACP declined to comment.

Antonio Ingram, an assistant counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, said lawyers for Republican leaders tried to shift the emphasis to Clyburn’s early requests. He said it was “inappropriate to blame a congressman for the General Assembly’s decision to pass discriminatory maps.”

Republican leaders appealed the panel’s decision and asked the Supreme Court to reject the racial gerrymandering charge.

If the court orders that the map be redrawn, it could have ripple effects on Clyburn’s district and other parts of the state. Although a Republican challenger gained ground on him in 2022, he’s considered a shoo-in if he chooses to seek reelection, no matter how the lines are drawn.

Taiwan Scott, who lives in Mace’s district and is the lead plaintiff in the NAACP lawsuit, said racial gerrymandering has deprived Black voters of fair congressional representation. A small businessman in Hilton Head, Scott said Black people are showing disapproval by declining to vote.

“It is bigger than myself. It’s systemic,” he said.

READ MORE  The UN expert Juan Méndez said he had been moved by the 'harrowing pain of victims and their families, and the resounding calls for accountability.'(photo: Martial Trezzini/EPA)

The UN expert Juan Méndez said he had been moved by the 'harrowing pain of victims and their families, and the resounding calls for accountability.'(photo: Martial Trezzini/EPA)

Historic two-week tour of US ends with call for nationwide commitment to address racial discrimination in dealings with law

UN experts completed their first official visit to the US as part of a system of global inquiries set up by the human rights council after the police murder of George Floyd in May 2020. As they ended their tour on Friday in Washington DC, the experts called for a nationwide commitment to address discrimination suffered by Black Americans in their daily dealings with the law.

“In the US, racial inequity dates back to the very creation of this country and there’ll be no quick fixes,” said Dr Tracie Keesee, one of two independent UN experts who conducted the visit. “To this day, racial discrimination permeates through encounters with law enforcement – from first contact, arrest, detention, sentencing and disenfranchisement.”

What was needed was a “whole government approach”, Keesee added. “This needs to be more than a slogan and calls for reform.”

In the course of their 15-day mission Keesee and Juan Méndez of Argentina, visited six US cities: Washington, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Chicago, Minneapolis and New York. Their mission was to investigate excessive use of force, militarised policing, racial profiling and other human rights violations by law enforcement and penal agencies against Black Americans.

As they crisscrossed the country, the experts had emotional encounters with families of the victims of police killings and other law enforcement abuses. In Minneapolis, where a white police officer murdered George Floyd on 25 May 2020, the panel spent time with the mothers of Philando Castile and Amir Locke, who were also killed by law enforcement in the city.

Locke’s mother, Karen Wells, told the visiting experts: “You are probably wondering, why is there an empty chair right here? Because that’s where Amir should be sitting. All of the families now have an empty chair.”

Presenting their preliminary findings, Keesee said that they had witnessed a pattern that could be traced to what she called the “deep intrinsic legacy” of slavery and legalized discrimination. She said that across the country there remained “a lack of awareness and acknowledgment of the extent to which racial inequities” were still prevalent.

The result was a “culminating exhaustion in the Black community”, the UN expert said.

Méndez, a former UN special rapporteur on torture, said that he had been moved throughout the visit by the “harrowing pain of victims and their families, and the resounding calls for accountability”.

“We support those calls for accountability,” Méndez said.

He was heartened by successful prosecutions of police officers involved in high-profile killings such as that of Floyd. However, many more cases remained unresolved, suggesting a continuing degree of impunity.

Méndez added that their mission would be calling on the US justice department to make “more serious and proactive” use of its powers through consent decrees to intervene in the inner workings of local police departments to address some of the most egregious abuses. “More robust government action is needed,” he said.

The UN experts will present their final report to the human rights council in Geneva in September or October. They indicated that among the demands they are likely to make is a call for better nationwide data and record keeping.

In the absence of a national database, Méndez said, police officers who had complaints of misconduct or excessive force filed against them were allowed to continue serving, in some cases going on to be involved in killings of Black people. He added: “The mechanism also received allegations of police officers who were previously guilty and or disciplined for misconduct, afterwards being hired by a different police department.”

Among other likely demands signaled by the experts were:

- A call for an end to racial profiling in policing.

- A dramatic reduction in the use of solitary confinement in US jails and prisons, and the total abolition of isolated incarceration for children under 18.

- Passage of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act which tackles racial bias and excessive use of force but which has stalled in Congress.

- An end to stereotyping of Black women and girls as angry and “aged up”.

- Rooting out of white supremacist law enforcement officers to ensure that they no longer wear the badge.

The completed visit marks an intensification in the UN’s focus on racial justice in America in the aftermath of the Floyd killing and the summer of protests it triggered across the US and around the world. A year after Floyd died, the then UN high commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet, lamented what she called the “insufficient” steps taken in the US to “stop people of African descent from being killed”.

Fatal police shootings affecting all races and ethnicities have continued unabated since the summer of Black Lives Matter protests. The average still runs at a rate of almost three people daily.

In April 2021, the human rights council set up what it called the Expert Mechanism to Advance Racial Justice and Equality in law enforcement (EMLER). It is part of a network of independent UN experts and monitors used to cajole governments to do more to address human rights violations in their territories.

Though they have no powers to enforce their findings, UN experts have shown themselves able to profoundly influence domestic political debate, especially within the US. In June 2018, the Donald Trump White House’s then ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, pulled the US out of membership of the human rights council, complaining that it was a “cesspool of political bias”.

Haley, who is currently vying with Trump for the Republican presidential nomination in 2024, made her move just days before the UN monitor on extreme poverty delivered a withering report on US deprivation after a similar two-week tour of the country. In October 2021, the Joe Biden White House reversed course, re-entering the US into the human rights council.

Keesee and Méndez’s visit has already sparked debate within the US over unaddressed police brutality. Minnesota’s Democratic congresswoman Ilhan Omar told the Guardian after the experts’ stopover in Minneapolis that “state-sanctioned violence” against Black people “continues to happen at the same rate, if not higher”.

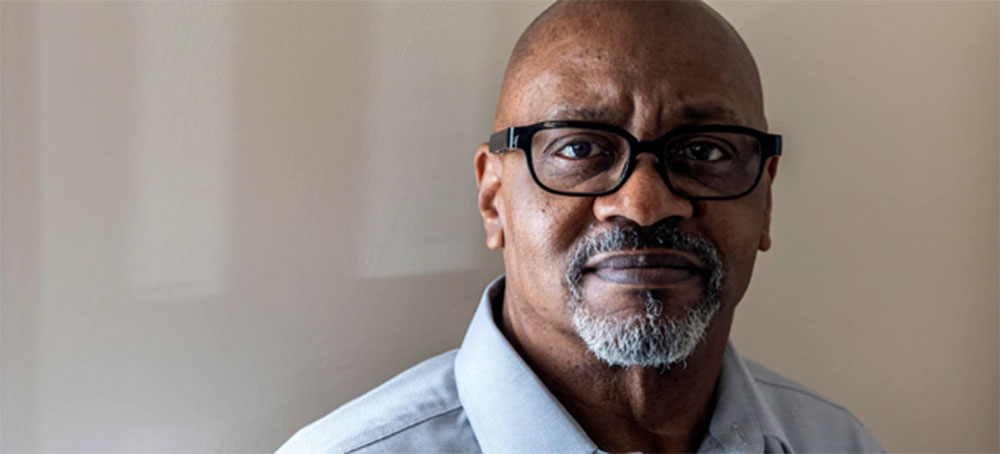

READ MORE  Louis Sloan, of Tallahassee, recently retired after 16 years with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. (photo: Mark Wallheiser/WP)

Louis Sloan, of Tallahassee, recently retired after 16 years with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement. (photo: Mark Wallheiser/WP)

They worked for a statewide police agency charged with protecting the governor and investigating major crimes. But last summer, they were enlisted in a highly unusual effort: laying the groundwork for a politically charged operation — ordered by Gov. Ron DeSantis — to fly border crossers from San Antonio to the liberal haven of Martha’s Vineyard.

“Tomorrow we meet FDLE at 0900 and have a full day on the schedule,” wrote Perla Huerta, a former Army counterintelligence officer working with the FDLE agents, in a text message released by the governor’s office; migrants later said they were lured onto the flights with false promises by Huerta, who has not commented on the claims or her work for a private contractor involved in the operation.

The statewide police force’s on-the-ground involvement in planning the Sept. 14 flights speaks to how DeSantis has increasingly deployed FDLE outside its traditional portfolio and in support of his own political agenda, according to a Washington Post review of court documents, state records and interviews with more than a dozen current and former administrators and agents, many of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity because of fear of retribution.

FDLE members surveilled buses traveling through Florida with unaccompanied migrant children as the governor bashed President Biden’s immigration policies. They rounded up felons alleged to have voted illegally as DeSantis touted a new election crimes office popular with the right wing. And they were asked to scrutinize the crime-fighting record of a Democratic prosecutor who had repeatedly clashed with the governor.

Inside FDLE, many members balked at these directives from the governor’s office, which they viewed as political stunts orchestrated to raise DeSantis’s national profile, The Post’s interviews found, and some who openly resisted the governor’s priorities were pushed out. Several former top officials spoke on the record with The Post for the first time regarding their concerns about executive overreach into law enforcement — which they said escalated after DeSantis installed a new FDLE chief last spring.

“For me it was a stain on the agency when it got involved in this even though there is no large-scale election fraud,” said former FDLE bureau chief Louis Sloan, who retired two years earlier than planned because of the voter arrests and turnover inside the agency. “We’re enforcing someone’s political agenda — the governor’s.”

DeSantis, a likely presidential contender in 2024, has built a reputation as a culture warrior in the GOP by weaponizing state government against school districts that required masks, companies that balked at his education policies and private venues that hosted drag performances.

But the former FDLE officials say that the governor is taking a particularly dangerous risk by politicizing a statewide police force with a $300 million budget, almost 2,000 employees and the broad power to launch criminal investigations and make arrests. FDLE is responsible for investigating major violent, drug, economic and computer crimes and public corruption — including potential complaints about the governor’s office.

“FDLE is more politically directed and controlled by the governor than in its 50 years of existence,” said Jim Madden, who retired as an FDLE assistant commissioner in 2014 after 24 years with the agency. “If citizens can’t rely on an independent, nonpolitical statewide police agency, it’s one of the worst things that can happen.”

The governor’s office did not respond to a detailed list of questions from The Post about his oversight of FDLE. Deputy press secretary Jeremy Redfern instead pointed to a recent report from a statewide grand jury, impaneled at DeSantis’s request and overseen by the statewide prosecutor under Republican Attorney General Ashley Moody, that blasted the Biden administration’s treatment of unaccompanied minors who cross the border and its failure to properly vet all caregivers who take them in.

“The Biden Administration is failing to secure our nation’s borders, and Governor DeSantis will continue to fight back,” Redfern said.

Court documents show the governor tapped FDLE last year to serve as the lead investigator for the grand jury’s work, which would later fuel his talking points on illegal immigration. The agency declined to comment on its role. In response to The Post’s questions about the governor’s influence, the agency said in a statement that it “serves the public” and its “mission has not changed.”

DeSantis has suggested that FDLE should report exclusively to him, though the Florida constitution gives shared oversight to the governor and Cabinet. He’s consolidated power under a 2022 law that allowed him to swiftly anoint new FDLE leadership, while also significantly cutting down on the Cabinet meetings meant to provide oversight of the agency.

DeSantis has cited Founding Father Alexander Hamilton as his inspiration.

“He would not have liked the fact that you have a Cabinet system of government where the executive power is splintered in certain areas,” DeSantis said during a news conference last year. “For example, FDLE. The head of that agency is all four Cabinet members acting together. There is not actually one person who is accountable for FDLE.”

“Hamilton hated that,” he continued. “He thought there had to be one person that was accountable, one person that could make the decisions and you would have a very clear chain of command.”

Consolidating control

FDLE was established more than a half century ago “to promote public safety and strengthen domestic security” in the state, according to its mission statement.

Florida’s Constitution sought to keep gubernatorial power over the agency in check by having FDLE report to both the governor and Cabinet, which includes the state’s elected chief financial officer, attorney general and agriculture commissioner. That arrangement didn’t always prevent political conflicts, however.

DeSantis’s Republican predecessor, Rick Scott, pushed out FDLE commissioner Gerald Bailey in 2014 after Bailey defied what he viewed as overtly political demands, including for a voter fraud probe. News organizations sued Scott and the Cabinet, alleging that they had violated open meetings laws by discussing Bailey’s replacement through their aides. A court later ordered state officials to be more transparent when hiring an FDLE chief. Scott declined to comment on the matter.

Bailey’s successor, Rick Swearingen, sought to dispel any perception that he was “the governor’s boy,” vowing, “If I’m asked to do anything illegal, unethical or immoral, I can walk away tomorrow.” In 2018, when Scott again demanded that FDLE investigate voting fraud amid a recount in his Senate race, a spokesman for the agency said it could not launch a probe without referrals from election officials.

The balance of power changed last March, under a new law allowing a majority of the three-member Cabinet to approve the governor’s pick for FDLE chief instead of requiring a unanimous vote. Republican lawmakers said the change was overdue since 2003, when the Cabinet shrank from six to three members. The lone Democrat on the Cabinet at the time, Agriculture Commissioner Nikki Fried, denounced the legislation as a “power grab.”

Bailey told The Post he didn’t agree with the change. “It means less independence for the agency and more allegiance to a single politician,” said Bailey, who has worked as a law enforcement consultant since he left state government.

Swearingen, who had faced mounting pressure under DeSantis to be more aggressive on immigration and election fraud, abruptly resigned without explanation soon after the new law was signed.

“Now we’re in a situation where we have an opportunity to focus on some other issues,” DeSantis said in March 2022 after Swearingen announced his retirement. Swearingen declined to comment to The Post and has never spoken publicly about his departure.

At the next Cabinet meeting in August, it took less than a minute for DeSantis to install a new FDLE chief.

DeSantis nominated Mark Glass, the director of the Capitol Police, who had served as the interim commissioner since May. Five years earlier, Glass was transferred out of his job as an FDLE director into a new role with reduced pay, according to his personnel file, which classified the move as a demotion. The file, which The Post obtained, includes a request from Glass at that time to be reassigned “due to my current family needs.” FDLE pointed to Glass’s positive job reviews and did not make him available for an interview.

Although the settlement from Bailey’s ouster requires FDLE appointees to undergo a public interview, none of the Cabinet members asked Glass any questions about his background or vision for the agency, according to video of the August 2022 Cabinet meeting on a state website. His nomination was immediately seconded by the chief financial officer, Republican Jimmy Patronis. “He has a lot of ideas for the agency, ready to serve in this capacity so I would second that as well,” added Moody, the attorney general.

“Good call,” DeSantis quickly responded. “Okay. Congratulations Commissioner Glass.”

Fried was silent. The governor never called for a vote.

Fried, who now serves as chairwoman of the Florida Democratic Party after an unsuccessful gubernatorial bid, said she wasn’t opposed to Glass personally but criticized a process she said reflected DeSantis’s unilateral approach to governing. Though Glass still reports to the Cabinet, DeSantis has drastically reduced the frequency of its meetings.

Since 2020, the Cabinet has met only 12 times — a stark contrast to Scott’s two terms, when it met an average of more than once per month, public records show.

“His style is to govern alone,” Fried said. “He doesn’t want input, particularly dissent.”

DeSantis, Moody and Patronis did not respond to questions about Glass’s hiring process and the decline in Cabinet meetings.

Arrested for voting

Trump’s false claims that voter fraud led to his 2020 defeat — despite carrying Florida by a three-point margin — had placed DeSantis in a politically awkward spot. The governor rebuffed calls for a costly, Arizona-style audit as he and other Republican leaders cast the state’s election as a national model.

But as “election integrity” became a leading talking point on the right, DeSantis launched a voting fraud unit last year in which FDLE would play a key role.

Republican lawmakers passed a bill in 2022 creating the unit and allowing the governor to help the FDLE chief choose agents to investigate voting crimes. Under Swearingen, FDLE pushed back on the plan, arguing that there was insufficient fraud for several full-time agents. Lawmakers adjusted the bill’s language to allow those assigned to the election unit to work on other issues.

“It’s like they were in search of a problem,” said Cynthia Sanz, who retired as an FDLE assistant commissioner in 2014 but keeps tabs on the agency where she worked for three decades. “I never saw any indication of widespread organized election fraud or voting fraud. ”

In Glass, DeSantis found a publicly supportive partner. Glass stood by his side in August when he announced the statewide sweep of 20 felons who had allegedly voted illegally in 2020. “I want to thank Governor DeSantis for his commitment to making sure Florida is a national leader when it comes to having secure elections,” Glass said.

Although a constitutional amendment approved by Florida voters in 2018 made it easier for felons to regain voting rights after completing their prison sentences, the change did not apply to people convicted of murder or felony sex offenses. Police body-camera footage first obtained by the Tampa Bay Times and the Guardian shows FDLE agents gently explaining to several bewildered Miami-Dade and Tampa-area residents that they were being arrested for voter fraud because they were ineligible under the amendment.

“Oh my God!” says one 55-year-old Tampa woman as she puts her hands behind her back to be handcuffed.

“I know you’re caught off guard. I understand,” says one male agent.

“I voted but I didn’t commit no fraud!” the woman responds.

Several people working at FDLE as well as former agency officials told The Post they cringed at the scenes of mostly Black people being arrested by contrite agents. Two men were pulled from their homes in their underwear.

“It’s hard to see an FDLE agent apologizing for making an arrest,” Bailey said. “An agent of that caliber of law enforcement agency should be proud of any arrest they make.”

Attorney Jason Blank, who is representing one of the voters arrested in the sweep, said the state faces an uphill battle to prove that his client and other defendants willingly and knowingly broke the law, since election officials had approved their applications and mailed them registration cards. Six of the 20 cases have been dismissed, so far. Five other defendants accepted plea deals that resulted in no jail time. Only one case has gone to trial, resulting in a split verdict; the defendant was sentenced to two years probation.

The first arrests from DeSantis’s election police take extensive toll

“There’s no doubt that governor weaponized FDLE to effectuate his political motives,” Blank said. “These are people who simply want to exercise the foremost right of every American citizen.”

Sloan, the FDLE supervisor who retired early, is Black, and he said the televised footage of the arrests made him think about what his parents and grandparents had endured to vote, particularly his grandfather who had been active in the NAACP. Sloan is a registered Democrat but said he had no problem working under Republican governors in the past.

As agency leaders he respected were pushed out, Sloan decided to retire at the age of 60, even though it diminished his retirement savings.

“The politicization of government is concerning,” he said. “I loved serving the people of Florida, but it’s been tainted.”

Targeting migrants

In the summer of 2021, as apprehensions at the southern border surged, DeSantis seized on the issue that once helped propel Trump to the White House.

He staked claim to being the first governor to respond to a request for assistance from the governors of Texas and Arizona, dispatching 50 officers from FDLE and two other state agencies to the border to back up Texas patrols. DeSantis trumpeted the effort at a July 2021 news conference in Del Rio, Texas, claiming that most of the border crossers at that juncture were headed to Florida. Democrats blasted the governor for diverting law enforcement officers away from the state they are supposed to protect.

As DeSantis lashed out at the Biden administration’s border security policies, he saw opportunities for FDLE to crack down on illegal immigration. In September 2021, the governor signed a sweeping executive order directing FDLE to collect detailed information on migrants transferred to Florida by the federal government and encouraging officers to pull over vehicles suspected of transporting migrants.

At a news conference several weeks later, the governor accused the Biden administration of “dumping” dozens of planeloads of illegal immigrants in Jacksonville in the past several months. He suggested they were a threat to public safety, pointing to a Honduran migrant who had posed as a minor and was charged that day with stabbing a Jacksonville man to death. “This is not the way you keep people safe,” DeSantis said of the flights. “It’s reckless and it’s wrong.”

The flights largely carried unaccompanied minors later transported to sponsors or government-approved shelters. Federal law requires these unaccompanied minors to be transferred to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services within 72 hours, except in exceptional circumstances.

Under Swearingen, tension between the governor’s office and FDLE peaked as the agency was directed to photograph migrants boarding the buses in Jacksonville and follow them to their destinations. FDLE members raised concerns about whether they were violating the civil liberties of the migrants, who were not criminal suspects, The Post’s interviews found.

In a statement to The Post, FDLE said the federal government did not respond to its requests for information about the flights and who was on them. Referring to the Honduran immigrant who later pleaded guilty to second-degree murder, FDLE said: “The failure of the federal government to report transporting unaccompanied children and undocumented migrants into Florida posed a potential — and in at least one case a lethal — threat to Florida’s citizens and visitors.”

A spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services said it does not identify unaccompanied children under its care to protect their privacy and security. The agency declined to comment on how the Honduran migrant got to Florida.

By the spring of 2022, Swearingen was out and Glass had taken over. DeSantis secured $12 million in the state budget for migrant relocation and designated FDLE as the lead investigator for the grand jury, which was impaneled to look into smuggling and trafficking. And in August, FDLE agents joined the surveillance team that traveled to the border town of Del Rio, Tex.

The group included Larry Keefe, the governor’s public safety adviser, James Montgomerie of Vertol Systems, an aviation firm that records show later received more than $1.5 million from the migrant relocation program, and Huerta, who was working for Vertol Systems, according to the texts released by the governor’s office. They surveyed an airport and warehouses and discussed the number of people crossing the border, as the Miami Herald reported.

“Perla and I are headed to dinner with the two FDLE agents,” Keefe wrote to Montgomerie on Aug. 15.

Keefe, Montgomerie and Huerta did not respond to requests for comment from The Post. The messages between them were released after the Florida Center for Government Accountability, a watchdog group, sued the governor for public records related to the flights.

One month later, Fox News was given exclusive access to broadcast video of dozens of migrants getting off two planes flown from San Antonio to Martha’s Vineyard, a vacation spot favored by wealthy Democrats like former president Barack Obama.

News organizations scrambled to learn about the recruiter who, according to interviews with the mostly Venezuelan migrants, had enticed them with promises of jobs and housing on the other side of the journey. Shortly after the flights, FDLE spokeswoman Gretl Plessinger told The Post that Huerta “is in no way affiliated with FDLE.”

Asked about the texts showing agents working with Huerta in August, FDLE’s statement to The Post stressed that agents did not have contact with the migrants flown to Martha’s Vineyard.

“The steady influx of undocumented migrants into Texas and other border states represents a threat to the security of Florida,” the statement said. “We have long investigated human smuggling, human trafficking, and drug trafficking — state crimes commonly associated with criminals who enter, or bring victims into, the U.S. illegally.”

DeSantis held another news conference in February attacking the Biden administration’s border policies and endorsing stronger penalties for human smuggling, along with other recommendations made by the grand jury. Glass was by his side.

“I just want to tell you what a pleasure it is to work for Governor DeSantis,” he said. “We have a Florida governor who gets it and he understands it, especially when it comes to law enforcement and public safety … These federal failures are requiring Florida fixes and this is the man to fix it.”

Suspending a prosecutor

DeSantis’s suspension of a Democratic prosecutor last year also demonstrated the governor flexing executive power over FDLE.

After the U.S. Supreme Court last summer overturned the constitutional right to abortion, Hillsborough State Attorney Andrew Warren joined prosecutors nationwide in pledging not to prosecute abortion-related crimes. DeSantis had sparred with Warren for years and recently signed a law banning abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy.

FDLE officials were asked by the governor’s office that summer to produce crime statistics that would help build the governor’s case against Warren, according to a deposition in the federal lawsuit Warren filed against the governor.

Keefe, the governor’s adviser, described in the deposition obtained by The Post how the research on Warren included talking to law enforcement leaders and pressing FDLE for crime data. FDLE collects crime statistics from local law enforcement agencies and shares it with the FBI and other states.

“I know that the general counsel’s office had some interactions with FDLE having to do with crime statistics and data,” Keefe said. “There was some inquiry into those things.”

In August, DeSantis suspended Warren, arguing that his refusal to enforce specific laws translates to neglect of duty and incompetence. But the order does not contain any criminal allegations that would have warranted the involvement of the state’s police force in examining his record as a prosecutor, said Jean-Jacques Cabou, a lawyer representing Warren.

“We were stunned to see FDLE play any role in the Governor’s illegal suspension of Mr. Warren,” he said. “This is not a law enforcement investigation.”

FDLE said in its statement that the agency’s mission includes “more than criminal investigations” and that maintaining crime statistics is part of its job. The governor’s office did not respond to questions about FDLE’s role in Warren’s suspension.

Help from the legislature

Following his landslide reelection last fall, DeSantis is turning to GOP supermajorities in the legislature to help him further engage law enforcement in support of his political goals — and to provide legal cover for his past efforts.

In a special legislative session earlier this year, as judges were tossing out illegal voting cases because the statewide prosecutor lacked jurisdiction, the legislature handed the power to handle election fraud charges to the prosecutor appointed by the attorney general. In the same session, lawmakers passed a measure allowing state officials to relocate migrants from anywhere in the United States — not just from Florida — in response to a lawsuit over the flights to Martha’s Vineyard.

On Tuesday, lawmakers approved a sweeping bill cracking down on illegal immigrants that directs FDLE to assist the federal government in enforcing immigration laws. The bill includes $12 million for additional migrant flights.

DeSantis is also seeking to increase state spending on the FDLE-assisted election crimes office, as well as the Florida State Guard, a long-defunct force reestablished last year with a $10 million budget. One budget proposal would more than triple the size of the force to 1,500 with a budget of roughly $100 million and a wide-ranging mandate. Guard members would carry weapons and be able to make arrests.

A person familiar with the negotiations who was not authorized to speak publicly said the governor’s office has contemplated using guard members to monitor ballot boxes, track illegal immigrants and respond to protests. The governor’s office did not respond to questions about that proposal.

Glass, the FDLE chief, backed a bill passed this week that would shield the governor’s travel from public disclosure — even his past trips. FDLE is in charge of the governor’s travel in state-owned vehicles. Florida House leaders also added $3.8 million this week to FDLE’s budget for protecting the governor and his family.

The additional money and public records exemption come as DeSantis is making numerous out-of-state appearances at book signings and political events before an expected announcement that he’s joining the 2024 presidential race. Glass told lawmakers last month he was “comfortable” with the new restrictions on public records and said it was necessary to protect the “security posture” of FDLE agents.

Republican lawmakers have defended the immigration and election-related initiatives as part of a broader effort to maintain law and order. But FDLE veterans are concerned that the agency is growing too beholden to the governor.

“When you politicize a law enforcement agency, it’s very dangerous,” said Sanz, the former assistant commissioner. “It runs the risk of becoming the governor’s personal police force.”

READ MORE  Migrants wake up while camping on a street in downtown El Paso, Texas, Sunday, April 30, 2023. (photo: Andres Leighton/AP)

Migrants wake up while camping on a street in downtown El Paso, Texas, Sunday, April 30, 2023. (photo: Andres Leighton/AP)

ALSO SEE: Biden to Send 1,500 Active-Duty Troops to the Southern Border

While the Trump administration launched Title 42 as a “temporary” measure to supposedly prevent the spread of COVID-19, it was used instead as a blunt enforcement tool to expel migrants, including families, children and legitimate asylum seekers from the United States. Sadly, Title 42 will leave much human suffering in its wake, and yet, it has not strengthened our asylum system or border management.

Latinos, like all Americans, expect that our government will effectively manage our borders and thoroughly vet those who seek to enter as refugees, to join family or for work. Our community does not support open borders, nor do we tolerate seeing children in danger, families separated and detained or people suffering. We want a functioning immigration system that is humane, efficient and secure.

The federal government has taken some constructive steps that help ease the strain on the border. The Biden administration has moved to restore public and private partnerships to stimulate investments, job growth and community stability in Central America. Such regional cooperation gets in front of what drives people to leave their countries in the first place. We also support the administration’s parole program, which allows migrants from certain countries to come legally to the U.S. for humanitarian reasons. This eases the amount of vetting that happens on our southern border; it’s also far safer for people to come with a visa than a smuggler.

These efforts still fall short, however, of addressing our border challenges, much less when Title 42 ends. Aware of this, the Biden administration proposed an asylum rule that would encourage people to seek refuge closer to home and to enter the U.S. at our southern border with an appointment using a smartphone app.

While UnidosUS supports such efforts to help refugees avoid the dangerous journey north or to enter the U.S. in a legal and orderly manner, we strongly oppose the asylum rule.

The heart of our objections to the Biden asylum policy is that what the administration touts as incentives will in fact significantly limit access to asylum. The rule, paired with the Department of Homeland Security’s plan to swiftly expel migrants under Title 8 and to deploy 1,500 troops on the border, will result in denying refuge to the most vulnerable migrants, including families with children. It’s also unclear if the incentives will work. Ongoing monitoring is needed to ensure meaningful access to asylum in transit countries and vigorous improvements of the CBP One app are critical, given its reported and significant problems. In the end, refugees will be returned to life-threatening danger in their home countries and this is the asylum rule’s fatal flaw.

While there are no quick fixes to the humanitarian challenges on our southern border — thanks to restrictionists in Congress who have obstructed bipartisan immigration reform for decades — there are solutions.

The Menendez Plan, proposed by Sen. Bob Menendez (D-N.J.) offers pragmatic and forward-looking solutions to manage migration and refugees in the Americas and secure our borders. Instead of severely limiting asylum access, the administration should invest deeper in hemispheric cooperation and further expand avenues for humanitarian migration. We also need to strengthen our asylum processes, which require an integrated system of multi-agency reception facilities, legal services and representation, trained adjudicators and well-resourced court proceedings that timely move asylum cases forward while protecting due process.

For this, the government needs the resources. We call on Congress to fund the above-mentioned solutions to restore fairness to the asylum process, improve humanitarian conditions at the border and ensure communities have the resources they need to welcome newcomers. Doing so will provide a path forward for members of Congress serious about addressing the dire humanitarian situation on the border and hold accountable anti-immigrant lawmakers who just want to take selfies there.

President Biden took office after campaigning on a pledge to use more humane immigration policies than his predecessor. Creating incentives to reduce irregular migration, investing in border resources to respond to humanitarian migration and increasing funding for legal services and community-based organizations that support asylum seekers is the right approach and consistent with his promises.

READ MORE  People raise their hands as they leave a shopping center following reports of a shooting, in Allen, Texas, on Saturday. (photo: LM Otero/AP)

People raise their hands as they leave a shopping center following reports of a shooting, in Allen, Texas, on Saturday. (photo: LM Otero/AP)

An officer from the Allen Police Department heard gunshots at Allen Premium Outlets at 3:36 p.m. while out on an unrelated call. He then located and "neutralized" the shooter, said Brian Harvey, the police chief for the Allen Police Department, during a Saturday night press conference. The shooter is believed to have acted alone, he said.

The officer then called for emergency personnel, the department said in an earlier tweet, and a multi-agency response helped secure the mall.

"This is an ongoing, active investigation," Harvey said.

Seven people, including the shooter, were pronounced dead on the scene, and nine people were transported to area hospitals, said Allen Fire Department Chief Jonathan Boyd. Of the nine hospitalized, two people have since died, three are in critical condition, and four are in stable condition, he said.

In a written statement, Medical City Healthcare, a Dallas-area hospital system, said it was treating eight people between the ages of 5 and 61.

A dash cam video posted on social media appears to show a shooter exiting a vehicle on the driver's side before opening fire in front of the outlet mall.

Several police vehicles, armored trucks and ambulances responded to the scene. Hundreds of people, some with their hands raised, were evacuated from the area and police were seen directing them away from the mall.

The Associated Press quoted Fontayne Payton, 35, who was at an H&M store when he heard gunfire through the headphones he was wearing. "It was so loud, it sounded like it was right outside," he said.

Police Chief Harvey said: "I hope it goes without saying that our deepest sympathies are with the families of the victims."

"This is a tragedy," Harvey said. "People will be looking for answers. And we're just sorry that those families are experiencing that loss."

Texas Gov. Gregg Abbott issued a statement saying he had been in contact with Allen Mayor Ken Fulk and Texas Department of Public Safety Director Steven McCraw. "Our hearts are with the people of Allen, Texas tonight during this unspeakable tragedy," the governor said, adding that he had "offered the full support of the State of Texas to local officials to ensure all needed assistance and resources are swiftly deployed, including DPS officers, Texas Rangers, and investigative resources."

U.S. Rep. Keith Self, whose congressional district includes Collin County, tweeted: "We are devastated by the tragic news of the shootings that took place at the Allen Premium Outlets today. Our prayers are with the victims and their families and all law enforcement on the scene," Self wrote.

A White House official released a statement saying President Biden had been briefed on the shooting and was in touch with law enforcement and local officials to offer support.

Allen, with a population of about 109,000 people, is located about 25 miles north of downtown Dallas.

A vigil is scheduled for 5 p.m. on Sunday at Cottonwood Creek Church in the city of Allen.

READ MORE  Demonstrators listen to a speech at a protest in Khartoum, Sudan, in 2019, in the days following the overthrow of President Omar Hassan al-Bashir. (photo: Muhammad Salah/WP)

Demonstrators listen to a speech at a protest in Khartoum, Sudan, in 2019, in the days following the overthrow of President Omar Hassan al-Bashir. (photo: Muhammad Salah/WP)

But even amid the euphoria immediately after the overthrow of President Omar Hassan al-Bashir, who had terrorized the country for 30 years, the seeds of today’s conflict already had been sown.

Since the latest fighting exploded on April 14, Sudan’s citizens have been trying to identify the juncture at which their nation turned off the democratic path and headed down the road to a withering conflict between two generals battling for power. The fighting has killed at least 500 civilians — and probably far more — while sparking an exodus of tens of thousands of refugees, crippling aid operations that fed millions and threatening to set alight one of the world’s most unstable regions.

Some say the roots of today’s conflict can be traced back to Bashir, who fostered rival paramilitary units and armed groups to head off potential challengers in a nation that has experienced a string of coups and attempted coups.

For others, the cause was fatal flaws in the structure of the hybrid civilian-military government set up with international backing after Bashir was deposed. This arrangement concentrated power in the hands of the men with guns.

Still others point to the failure of the United States and other foreign powers to sanction the two generals when they jointly overthrew that hybrid government in 2021. Instead, foreign governments tried to coax the rival generals toward democratic reforms.

Ultimately, it boils down to one question: How do you get the men with money and guns to give up their weapons?

Sudan’s armed forces never really relinquished power during the country’s democratic uprising, even as Sudan’s peaceful revolution was capturing the imagination of many abroad. When Bashir was ousted on the night of April 10, 2019, his own officers arrested him. The army was still in charge. His intelligence chief already had been holding secret meetings with opposition supporters in a top-security prison to court civilian support, Reuters later reported.

In the days that followed, a deal was hammered out. The military, headed by Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, would form a Sovereignty Council government with civilian representatives. Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo — universally known as Hemedti and head of the powerful paramilitary Rapid Support Forces — also was a key player. Abdalla Hamdok, a civilian, was appointed prime minister but had little real power under the new, internationally backed transitional constitution.

“The writing was always on the wall,” Hamdok recounted. “Revolutions come in cycles, and 2019 was the high.”

Justin Lynch, a co-author of the book “Sudan’s Unfinished Democracy,” said there were obstacles to civilian rule from the beginning. “If the international community did everything right, it’s still not clear that the revolution would have succeeded,” he said. “After the transitional constitution was signed, it was always clear the military were going to keep power.”

The military and the RSF kept all the guns. Their business interests, including chunks of state-owned companies and private enterprises, gold mines and petroleum operations, remained untouched.

But Hamdok had an ace up his sleeve. With Sudan facing skyrocketing inflation and about $60 billion of debt, he was a liberal economist with whom international financial institutions could do business. When South Sudan seceded in 2011 after decades of civil war, Sudan lost about 75 percent of its oil production, 66 percent of exports and half of the government’s revenue. Bashir’s government began printing money to pay for fuel and bread subsidies. People’s anger grew along with the price of bread.

Hamdok had hoped he could deliver relief, cementing his place at the table, if international lenders released financial assistance quickly enough. But his government had to navigate a gantlet of reforms before funds would flow. It had to design and negotiate a reform package, demonstrate progress on reforming exchange rates and fuel subsidies, and clear the country’s arrears with major creditors. Sudan also was eager for the United States to drop its designation of the country as a sponsor of terrorism, a circumstance that dated to the Bashir era.

“One can speculate that had those things happened faster … it would have been much easier to maintain support,” said Magdi M. Amin, a former adviser to Sudan’s Ministry of Finance.

But those delays were not the chief problem, he added. The main problem arose when civilian investigators started probing the extensive business interests of the RSF and the military. Suddenly, the danger that civilian government represented to the men with guns outweighed the potential benefits.

Former finance minister Ibrahim al-Badawi said the June 2021 deal he negotiated with a consortium led by the International Monetary Fund laying out conditions for debt relief was a direct threat to the generals and their allies. Companies producing weapons and ammunition were to be audited, he said, and the business interests of the security forces examined.

The generals “are very careful observers,” he said. “The most significant clause in that agreement was anti-corruption and closer oversight of the ministry of finance.”

After the generals jointly ousted the hybrid government in October 2021, Hamdok tried to salvage its achievements by negotiating a return to civilian rule. But he resigned three months later, saying the military had no intention of sharing power. Meanwhile, the generals jailed the members of the anti-corruption committee and began systematically to reverse its work.

International debt relief and budgetary support was immediately suspended. But neither Hemedti nor Burhan faced targeted sanctions from Washington or other foreign capitals, even after security forces mowed down young demonstrators protesting what they called the theft of their revolution.

Instead, diplomats from the “Quad” of countries — the United States, Britain, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — tried to persuade the two generals to agree to a power-sharing arrangement that diplomats hoped would pave a path to democracy. The African Union, United Nations mission and a regional trade bloc known as the Intergovernmental Authority on Development also backed the talks.

“There was no accountability for the coup of 2021. We didn’t see any sanctions. We didn’t even see the State Department calling it a coup. The U.S. sort of set the tone for the response,” said Kholood Khair, the founding director of the Khartoum-based think tank Confluence Advisory. “There was no support for protesters, some of them wrongfully accused of capital crimes. … It was inconvenient for the narrative of the generals as reformers.”

The generals also got a lift from regional powers. Gold from mines owned by Hemedti’s family members flowed to markets in the UAE, where he maintained access to extensive business interests. Burhan enjoyed support from Egypt’s military-backed government.

Diplomats from the Quad helped to midwife a draft deal in December that was meant to lead to a civilian government and benefited the RSF far more than the military, thus increasing pressure on Burhan to reject the deal, Khair said.

“Because Hemedti had very cleverly aligned himself with Sudan’s democrats, the international community was not listening to any of the naysayers. They were wedded to this political process at all costs,” Khair said. But he added, “The central conflict between the generals was always obvious.”

Tensions grew over the draft deal, which was to be finalized in April, with differences arising over accountability for civilian deaths, corruption and, most of all, a timeline for integrating the RSF into the military and for power-sharing between the two forces. Hemedti wanted to keep his forces separate for another decade, thus maintaining his power base and retaining a status equal to that of Burhan, the de facto head of state. The military wanted the RSF integrated within two years.

Army leaders always had been uneasy about the RSF, which Bashir set up in 2013 to function as a front-line force in the war in the Darfur region. The RSF was drawn from local Arab militias known as the Janjaweed — “devils on horseback” — who were unleashed against the ethnic groups of African rebels who had challenged exploitation by the elite in Khartoum. The conflict killed about 300,000 people and eventually led the International Criminal Court to indict Bashir on charges of war crimes and genocide. The army generals feared that the RSF, with its independent command structure and financing, was growing into a rival for power.

Even into April, negotiations between the RSF and the armed forces continued over the power-sharing agreement, along with civilian representation and support from Western and Middle Eastern diplomats, according to former justice minister Nasredeen Abdulbari, who was leading efforts to draft a new transitional constitution. He said discussions between representatives of the two sides were still underway just hours before fighting broke out.

At the same time, both sides had been building up their forces in strategic locations. Air force planes from Egypt, which had close ties to Burhan, had arrived at the Merowe airfield north of Khartoum. The RSF had sent troops there and also moved many fighters and vehicles into the capital city.

It is still not clear which side fired the first shot on April 14 or who ordered it fired. If it was the army, it is not clear whether it was Burhan’s men or a rogue faction — Islamist officers loyal to the former president, Bashir — who pulled the trigger.

But within hours, full-scale battles involving airstrikes and artillery bombardment had erupted in cities across the country.

Many of Sudan’s pro-democracy activists say the latest fighting is not the end of their struggle. “The people do not trust either of these men. The revolution is not yet over,” said Elfatih Adam, an economics graduate and activist from Darfur. “This war is just one more stop on the way.”

READ MORE  President Joe Biden speaks about climate change at Brayton Power Station in Somerset, Mass., last year. His administration is preparing to announce carbon regulations on power plants. (photo: Evan Vucci/AP)

President Joe Biden speaks about climate change at Brayton Power Station in Somerset, Mass., last year. His administration is preparing to announce carbon regulations on power plants. (photo: Evan Vucci/AP)

Historically strict EPA regulations on coal- and gas-fired power plants are due out next week. They face legal and political peril.

The proposal from EPA, expected to be formally unveiled next week, makes key trade-offs in its efforts to slash the power industry’s greenhouse gas output without running afoul of a skeptical Supreme Court, according to four people briefed on the upcoming regulations.

EPA is expected to rely on advanced technologies rarely if ever employed in the U.S. power industry, such as capturing coal plants’ carbon pollution before it hits the atmosphere or blending hydrogen into the fuel mix at natural gas plants.

But it could also exempt hundreds of the nation’s dirtiest gas plants from strict pollution limits, these people said. That may lessen the rules’ legal peril and keep more units online, but it may also provide fewer benefits to the low-income, Black or Hispanic communities where the dirtiest plants are disproportionately located.

The proposal will be a capstone of President Joe Biden’s climate efforts before he faces voters next year and follows the historically aggressive pollution standards his agencies have proposed for oil and gas, cars and other industries. Its fate will likely determine whether the U.S. comes within reach of meeting his pledges to cut carbon pollution. It could also help Biden win support in 2024 from climate-minded voters turned off by some recent administration decisions favoring fossil fuel production.

If it succeeds, the rule would transform the U.S. economy by accelerating the dwindling of coal as a major power source, just as EPA’s proposals to limit car and truck pollution aim to spur a rapid shift to electric vehicles.

But the effort faces dangers. One is from the courts, which rejected both the Obama and Trump administrations’ attempts to enact climate rules for power plants. And Biden’s rule is coming so late in his term that if a Republican wins the White House next year, the new administration could sweep it away.

Supporters say Biden has no choice but to go big.

Biden will need both the power plant and automobile rules to reach his climate goals, said Bob Perciasepe, who was EPA’s deputy administrator under then-President Barack Obama. “You have to do these things. There’s no other way to do it.”

Opponents are eager to pounce. West Virginia Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, a Republican who led a Supreme Court fight last year that constrained EPA’s ability to tackle carbon emissions at power plants, last week vowed: “We’ll be ready.”

‘We need to go further’

As a presidential candidate, Biden promised to cut the economy’s carbon emissions in half by 2030, compared with 2005. That’s now the U.S. commitment to the rest of the world in the Paris climate deal.

But the U.S. can’t reduce its climate pollution that sharply without much steeper, faster cuts from the power grid, the nation’s second-largest carbon source. (Transportation is No. 1.)

Zero-carbon wattage is needed to provide power to new corners of the economy, including electric cars. And the power sector is a comparatively easy target for cuts that can buy extra time to bring down emissions from other sources, such as industry and agriculture, that are even more practically and politically challenging.

The grid has already shed more than a third of its greenhouse gas emissions since 2005, mainly thanks to the fracking boom that helped cheap natural gas gobble market share from coal.

Then last year, Congress approved $369 billion in clean energy investments and incentives in the climate law Democrats have dubbed the Inflation Reduction Act. Analysts said that moved the U.S. economy within striking distance of the 50 percent target — to about a 40 percent reduction by 2030, according to the research firms Energy Innovation and Rhodium Group.

The power plant rule could help make up the difference.

“When it comes to carbon pollution, the IRA made a significant down payment,” said Sam Ricketts, a co-founder and senior adviser at Evergreen Action. “But we need to go further.”

With Republicans now controlling the House and another presidential election on the horizon, EPA’s standards are the administration’s last, best chance of narrowing that gap before his term ends.

The administration’s environmental allies are demanding no less, saying EPA must propose game-changing rules for the power sector — both to address the climate emergency and to avoid dampening climate-minded voters’ enthusiasm. Biden has taken heat from climate activists lately in the wake of his administration’s approval of the massive Willow oil and gas project in Alaska.

“We applaud the positive steps Biden is taking with EPA regulations, but it’s not enough,” said Michael Greenberg, a spokesperson for the youth-led group Climate Defiance that protested at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner last weekend. “He needs to step up to the plate and stop extraction on federal lands and stop approving new projects.”

Rule may spare the dirtiest plants

The four people briefed on the draft rules and granted anonymity to speak freely said EPA is eyeing a pollution standard that is based on a technology not now used in the U.S. power industry — capturing the carbon pollution from all coal-fired power plants, most new gas plants and large existing gas units that run consistently.

New gas plants that are being built to run at high capacity would either capture their carbon emissions or opt for an alternative way to comply with the rule, the people said: blending hydrogen, which one day might produce few emissions, into their fuel.

The standards for existing plants would offer enough flexibility that some could keep running without undergoing expensive retrofits. And owners of some plants could choose to shut them down rather than comply with the rule.

The template tracks roughly with what influential green groups like Evergreen Action, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Clean Air Task Force have advocated.

On the other hand, the rules are also expected to set lighter standards for gas plants that run only infrequently — so-called peaker plants that provide electricity during times of highest demand. The country has about 1,000 such plants, which are dirtier and less efficient than power plants that run consistently. They’re also more likely to be located in urban areas, with the dirtiest ones sited near communities of color.

Some environmental groups have expressed concern about going easy on those plants. But setting a standard that the peaker plants can’t practically meet could expose the rule to trouble in court or compromise the reliability of the grid, some legal experts told E&E News this week.

Much of the industry argues that carbon capture isn’t ready for prime time even for standard power plants. But environmentalists point to the Inflation Reduction Act’s generous incentives for the technology, as well as carbon capture systems already used overseas and in U.S. industrial facilities, to argue that it is “adequately demonstrated,” as federal law requires.

They argue EPA need not base its standard on a technology that is in wide use already.