Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

nsigned, unexplained orders have reshaped American law.

Steve Vladeck, a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin and the author of the forthcoming The Shadow Docket, was one of the few legal observers who had been sounding the alarm on the Supreme Court’s use of emergency orders to make sweeping changes to American law outside of public scrutiny and regular procedure. Although emergency orders in time-sensitive cases had long been a part of the high court’s work, in recent years the volume, breadth, and partisan valence of the justices’ rulings in such matters had changed.

The conservative justices’ use of the shadow docket to make rapid, expansive rulings on important matters has since drawn public scrutiny and even criticism from both the Court’s Democratic appointees and Chief Justice John Roberts. Most recently, the Supreme Court stayed a ruling from a conservative judge outlawing the abortion drug mifepristone, an apparent retreat from the Court’s recent aggressive use of the shadow docket.

In his book, Vladeck notes that Justice Samuel Alito has “accused the shadow docket's critics of trying to intimidate the Court and undermine its legitimacy in the eyes of the public.” Vladeck explains, however, that he wrote the book not to delegitimize the Court, “but because I fear that the Court is delegitimizing itself, and that not enough people—the justices included—are noticing."

I spoke to Vladeck about his upcoming book, how the shadow docket has shaped American law, and whether public backlash to the Court’s conduct has had an effect on the justices.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Adam Serwer: What is the shadow docket? And why should people care?

Steve Vladeck: The term shadow docket is this evocative shorthand that Chicago law professor Will Baude coined in 2015, not as a pejorative, but just as an umbrella term to capture everything the Supreme Court does other than thoroughly explained, merits decisions [on the regular docket]. Will’s insight, which I’ve somewhat shamelessly appropriated, is that a lot of important stuff happens in the more technical side of the Court’s docket—important stuff that affects all of us, that shapes the law and lower courts, and that we sort of ignored at our peril. And what’s remarkable about that is that Will wrote that in 2015. And if anything, the last eight years have actually dramatically underscored just how right he was.

Serwer: How did the shadow docket change during the Trump administration?

Vladeck: It’s common for those who like to defend the Court to say, “There’s always been a shadow docket.” That’s true. The really big shift during the Trump administration is in how the Court used one slice of the shadow docket, what we might call the emergency docket. These are contexts in which a party is asking the Court to step in while a case is working its way through the courts, and either freeze a lower-court ruling or block government action that lower courts refuse to block.

And during the Trump administration, we see the Court intervening far more often, in non-death-penalty cases, where the emergency interventions are having statewide and nationwide effects. And so instead of the Court allowing an execution to proceed or freezing one, you have the Court allowing a Trump immigration policy to be carried out perhaps for three years, or freezing a state COVID restriction. That’s a huge qualitative shift. We also saw the Court doing this a lot more often. So there’s also a quantitative uptick. And all the while, the Court is hewing to its norm of not usually explaining any of these procedural orders. And so the Court is providing no rationale, no vote count, nor even telling us who wrote whatever the Court has said on the subject.

Serwer: How did COVID affect the shadow docket?

Vladeck: First we had the flurry of religious-liberty challenges to stay COVID-mitigation policies. And we saw these especially in blue states, where the claims were that COVID restrictions, insofar as they operated on houses of worship or other religious gatherings, violated the free-exercise clause.

Here we saw the Court’s most aggressive use of the shadow docket, repeatedly intervening—and especially after Justice Amy Coney Barrett replaced Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg—to block these policies in New York, to block them in California, to block them in Colorado, to block them in New Jersey. The COVID cases pushed the Court to expand the scope of religious-liberty protection in the Constitution entirely through these emergency orders, orders that were usually unexplained and never had the same process as merits cases. And that’s especially telling because all this is happening as the Court has on its merits docket cases that would have given the justices similar opportunities to expand the free-exercise clause.

That’s the first way. Then you have all of these election cases, where you have either states that try to make it easier to vote remotely because of COVID or states that don’t and then get sued. So you have an unusual concentration of election-related disputes, where the Court is put in the position of trying to decide what rules should attach to voting as we get closer and closer to the election. And we see, in both of those contexts … we see the Court using these emergency orders to shape policy, oftentimes without making any law. And, you know, I think, perhaps most perniciously in ways that tended to at least appear to favor Republicans over Democrats.

Serwer: Some people would say that the Supreme Court did exactly what should have been done in these religious-liberty shadow-docket cases: They were protecting people’s right to worship. How do you see those cases, and how do you see them having changed the legal landscape as far as religious liberty is concerned?

Vladeck: Reasonable folks are going to disagree about what the free-exercise clause ought to protect. The question is, if the Court is going to change the meaning of the free-exercise clause, should it be doing so through a series of emergency orders, where there hasn’t really been a full opportunity for briefing, where there was no oral argument, where there was really very little opportunity for friends of the Court to weigh in? Should [the Court] be doing this in a context in which they’re only supposed to grant relief, if the rights are already “indisputably clear”—that’s the standard for an injunction pending appeal? Or should they be doing it the normal way on the merits docket?

And so what’s remarkable about the COVID cases is that here’s a context where, instead of just using emergency applications and emergency orders to adjust the status quo, the Court willfully changed the underlying constitutional principles, perhaps added them in ways that we would think are defensible, if not even normally desirable—but in a way that really is not supposed to be what these kinds of procedural orders are for.

Serwer: Did you think that the Texas case regarding Senate Bill 8 and abortion was the first time the shadow docket really started drawing public notice outside of Court watchers and reporters?

Vladeck: Oh, absolutely. And there’s actually some media scholarship that backs this up. There was a study in the Chicago Policy Review that tracked references to the shadow docket in mainstream media outlets, and they skyrocketed after the September 2020 nonintervention in the Texas case. I think it was really the S.B. 8 case that put this on the map.

That attention also produced some fascinating reactions. In response to that public blowback, we saw the first conservative attempts to defend what the Court had been doing, with Alito’s speech at Notre Dame and editorials in The Wall Street Journal. But we also see some of the justices shifting their behavior. There’s this remarkably cryptic, but I think important, concurring opinion that Justice Barrett, joined by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, writes in the main health-care-worker vaccine case, at the end of October 2021. Justice Barrett basically says, Hey, just because you make out your case for emergency relief, doesn’t mean we have to grant it.

In retrospect, I think she was signaling that perhaps she and Justice Kavanaugh were lowering the temperature, and are going to be a little more cautious in when they would vote for emergency relief going forward. That’s borne out by what’s happened in the last 18 months, by how much less often the Court has granted emergency relief, by how much more often we’re seeing some combination of Alito, Clarence Thomas, and Neil Gorsuch dissent from rulings regarding emergency applications.

Serwer: How are the lower courts reacting to the way the Supreme Court has been using the shadow docket?

Vladeck: I think the lower courts are in a bit of a sticky wicket, because in some of these cases, especially in the COVID religious-liberty cases, the Supreme Court has been instructing lower courts that its unsigned, unexplained orders are precedential—and that lower courts are erring, as the Court says in one case of the Ninth Circuit, by not following rulings where there was no majority rationale. So I think the lower courts are largely doing their best, but it’s really hard to know what to do if you are a principled, faithful, lower-federal-court judge, when the Supreme Court historically has said, If we don’t provide a rationale, we’re not giving you precedent to follow, and then the Court acts differently in this context.

I think we’re seeing a bit of a smorgasbord where some lower courts are just following what the Supreme Court has said, and some are just throwing up their hands and saying, Without more guidance from the Supreme Court, I’m just sort of stuck here. That’s perhaps the biggest point on which there ought to be consensus: Leaving aside who wins and who loses, the less the Supreme Court explains itself in this context, the harder it is for the relevant actors, for the lower courts, for the relevant government officials, to understand what their responsibilities are. That should presumably be something we all have common cause in ameliorating.

Serwer: How would you describe the Court’s use of the shadow docket in voting-rights cases?

Vladeck: What we saw in 2022 was a pair of decisions in the Alabama and Louisiana cases where—after pretty exhaustive efforts to take evidence and get to the bottom of the factual disputes—lower courts had said, Hey, states, you’ve got to redraw your maps because the current ones violate the Voting Rights Act. And the Supreme Court, despite these lengthy lower-court rulings, just says, Hey, states, no, you don’t.

That’s especially significant in this particular moment, because between Alabama and Louisiana directly, that’s at least two House seats. There’s also a federal judge in Georgia who said he would have blocked Georgia’s maps but for the unexplained stay in the Alabama case. So that’s three House seats. You know, there’s a New York Times report that suggests that somewhere between seven and 10 House seats might have been directly affected by the Court’s voting-rights cases on the shadow docket in early 2022. That’s control of the House. If all of those districts had been majority-minority districts, I don’t think it’s that remarkable a suggestion that many of them would have been safe seats for Democrats. Instead, they were all safe seats for Republicans. And so right there, you have an argument that unsigned, unexplained orders from the Supreme Court helped Republicans to take control of the House of Representatives.

Serwer: Last week, the Court took up a ruling where a lower-court judge banned the abortion pill, which is the most common way that women today get abortions. What do you make of the Court’s decision there?

Vladeck: There’s so much to say about the mifepristone case. One thing is, in some respects, this is actually more like an old-school emergency application, where you have this remarkable outlier ruling by a lower court. It’s highly possible that the justices just looked at the equities and said, Whatever the right answer is to this case on appeal, we’re not going to disrupt such an important medication while that appeal works its way through the courts, that we’re going to sort of preserve the status quo, first and foremost, and worry about the legal issues later. So in that respect, I think it was actually probably a page out of the older playbook.

I also think that it’s emblematic of why the shadow docket has become such an important part of any public discussion of the Supreme Court. Because the mifepristone case gets from an injunction, or at least a stay by a district judge, to a pretty important rule by the Supreme Court in two weeks. Ten years ago, that would have been unheard of, and it’s become, to a large degree, de rigeur—you know, the student-loan cases get to the Supreme Court remarkably quickly after they’re filed. Part of why the shadow docket has become so important is because we’re seeing more and more of these lower-court rulings that put pressure on the justices far earlier in cases than they’re used to, with far higher stakes at that stage in litigation than they’re used to.

If the Court is frustrated with how many of these cases are getting to it in this crazy expedited, record-free posture, the justices have a way of expressing that and saying, This is no way to run a railroad. And instead, what we’re seeing is just one emergency after another, for a Court that as recently as five, six, seven years ago, would maybe have gotten one of these cases a year.

Serwer: Do you think public criticism and internal dissent at the Court over the shadow docket has made a difference?

Vladeck: I do. I mean, I’ll never prove it. But I think it’s really hard to look at the overall data set and compare, for example, the October 2020 term to the last two terms and not see pretty significant shifts in at least how some of the justices are behaving. Not surprisingly, the shifts are principally centered on the three justices in the middle. So Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Barrett and Kavanaugh.

But it’s hard to believe that that’s a coincidence. And it’s hard to believe that the subtle but significant shifts in when the Court has granted emergency relief and how it’s behaving in these cases are unrelated to some of the public criticism, to some of the pushback.

I think that’s an important point unto itself. There’s such a fatalism these days about the idea that the Court is in any way subject to public criticism, responsive to public criticism. To me, the shadow docket might be an object lesson and how maybe it actually is [responsive to public criticism], especially when we’re talking about procedural critiques, as opposed to substantive ones.

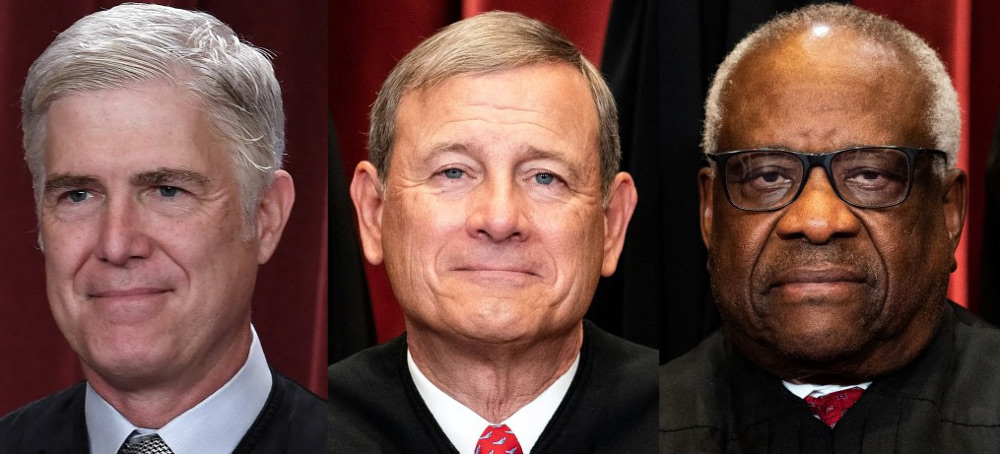

READ MORE  Justices Neil Gorsuch, John Roberts and Clarence Thomas. (photo: MSNBC)

Justices Neil Gorsuch, John Roberts and Clarence Thomas. (photo: MSNBC)

ALSO SEE: Overhaul of Supreme Court Ethics Runs Into GOP Opposition

Three conservative Supreme Court justices are now embroiled in a growing ethics scandal about their personal and financial connections. Recent reporting has revealed that Justice Neil Gorsuch sold property he co-owned to the head of a major law firm that has since had many cases before the court, Justice Clarence Thomas failed to disclose lavish gifts and payments from billionaire and conservative activist Harlan Crow, and the wife of Chief Justice John Roberts was paid over $10 million in commissions as a job recruiter placing lawyers at elite law firms. Legal experts and lawmakers are increasingly pushing for ethics reform on the high court, with the Senate Judiciary Committee holding a hearing on the issue on Tuesday. “Because they don’t have an ethics code, you don’t know whether they’re doing things in an above-board way,” says Vox senior correspondent Ian Millhiser. He also discusses growing frustration that California Senator Dianne Feinstein has not resigned her seat amid a prolonged absence from the Senate due to illness, which is stopping Democrats from confirming federal judges.

Democratic lawmakers have intensified their push to pass a Supreme Court ethics bill, after ProPublica revealed Clarence Thomas had failed to report frequent luxury trips paid for by the Republican billionaire Harlan Crow. For more than two decades, Thomas frequently joined Crow aboard his private yacht, jet and at his private estates. Thomas also failed to disclose that he had sold property to Crow, including a home where Thomas’s mother now lives rent-free.

Meanwhile, Politico has revealed Justice Neil Gorsuch sold 40 acres of property, just days after his Senate confirmation, to the head of one of the nation’s largest law firms, which has since had 22 cases before the Supreme Court.

And Business Insider reports the wife of Chief Justice John Roberts has been paid over $10 million as a job recruiter for placing lawyers at elite law firms, including some that have had cases before the court.

There are also questions about the finances of Clarence Thomas’s wife, the right-wing activist Ginni Thomas.

Senate Judiciary Chair Dick Durbin opened Tuesday’s hearing by talking about Justice Thomas.

SEN. DICK DURBIN: Last month we learned about a justice who for years has accepted lavish trips and real estate purchases worth hundreds of thousands of dollars from a billionaire with interests before the court. That justice failed to disclose these gifts, and has faced no apparent consequences under the court’s ethics principles. That justice claims that lengthy cruises aboard a luxury yacht are personal hospitality and are exempt under current ethical standards from even being reported. The fact that a Texas billionaire paid more than $100,000 for a justice’s mother’s home also seems to be an acceptable example because the justice insists that he lost money in the transaction. How low can the court go?

AMY GOODMAN: Joining us in Arlington, Virginia, is Ian Millhiser, senior correspondent at Vox, author of the book The Agenda: How a Republican Supreme Court Is Reshaping America.

Ian, welcome back to Democracy Now! Why don’t we just go through one scandal after another, and the fact that the chief justice, who is also being looked at for his wife’s $10 million that she made headhunting for law firms, many of them that have argued before the Supreme Court? Go through each of them and the fact that Chief Justice Roberts refused to testify.

IAN MILLHISER: Sure. So, you know, the biggest scandal here, I mean, the one that really should crystallize the mind, is what’s going on with Clarence Thomas. You know, this guy has accepted tens of thousands of dollars — by now hundreds of thousands of dollars — of gifts from a politically connected Republican donor for more than two decades. We have known about this for a long time. I mean, the earliest reporting I found about Thomas accepting gifts from Harlan Crow was a 2004 report in the L.A. Times about him accepting a $19,000 Bible. So, this is not acceptable. No employee of the federal government, that I’m aware of, is allowed to accept these kinds of gifts. If Thomas was in the House, if he was in the Senate, if he was in the White House, if he was anywhere else in government, this would not be allowed. If he was a lower court judge, this would not be allowed. And frankly, he should resign over this.

The other scandals, I think, show that the court is being very dumb by not having an ethics code. So, if you look at what happened with Neil Gorsuch, Gorsuch sold a plot of land. He sold the plot of land to someone who is a lawyer that runs a law firm that practices in front of the Supreme Court. If the court had an ethics code, there’s a way to do that transaction in a way that’s above board. You’d want an outside regulator or someone to look at the transaction, make sure it was at arm’s length, make sure it was fair market value, make sure that the buyer didn’t know who the seller was, the seller didn’t know who the buyer was. You know, there are ways that you can set up an ethics code so that justices can go about their business. But because they don’t have an ethics code, you don’t know whether they’re doing things in an above-board way. You don’t know — you know, they have no way to defend themselves when they get caught doing something like this. And suddenly, you know, the Roberts and Gorsuch incidents, I think, are much less serious than what happened with Clarence Thomas, but every scandal starts to look egregious, like what you have with Justice Thomas.

AMY GOODMAN: And explain also, with chief justice himself and how, obviously, he’s personally profiting because Jane Roberts is his wife, but the significance of this $10 million, actually more than that.

IAN MILLHISER: Right, yeah. So, Jane Roberts works as a legal recruiter. She works as, apparently, a very high-level legal recruiter, who helps firms that want to hire a lawyer find, you know, good lawyers, probably very specialized lawyers, that they can hire. And she’s made a lot of money doing this, you know, more than $10 million over the last several years.

Again, this is why the court needs an ethics code. I mean, you can imagine a situation where she had a law firm that was hiring our mergers and acquisitions partner. Law firms do this work all the time, where, you know, there’s one thing going on in one part of the firm that could create a conflict of interest relating to another part of the firm, and so you wall that off. If the Supreme Court had an ethics code, they could put in rules in place to make sure that the justices’ spouses can have their careers, but they are walled off in ways that do not impact the justices themselves.

But the court doesn’t have an ethics code. So, again, first of all, we have no way of knowing what’s going on here. Second of all, you know, there aren’t any formal checks in place to make sure that Jane Roberts’s work isn’t influencing what John Roberts does. And third, you know, because Roberts can’t point to any kind of code that he has followed, there is no way for him to defend himself when something like this arises.

AMY GOODMAN: And then, back to Clarence Thomas and his wife Ginni, how is it possible that he doesn’t recuse himself on, for example, an insurrection ruling, which she’s so been deeply implicated, everything from text messages with Trump’s Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, pushing states to overturn their elections?

IAN MILLHISER: Yeah, I mean, the thing with Clarence Thomas, he just doesn’t think the rules apply to him. I mean, that’s been true. If you look at his rulings, you know, he doesn’t believe in following precedent. He is perfectly fine with sweeping aside 80 years of law if he likes the way that it was done in 1918 better. He doesn’t think the rules apply to him. He doesn’t think the ethics rules apply to him.

And the court has said, fairly consistently, that it’s up to each justice to decide when they want to recuse. You know, the court has said that because they say they don’t with the other eight justices to remove other justices from cases, and that could change the outcomes. But again, the alternative is that you have Clarence Thomas ruling on all these cases where he or his family presents a fairly clear conflict of interest, and nothing can be done about it, because the only way to discipline a justice is through impeachment, and that requires 67 votes in the Senate. That requires 16 Republican senators to vote to remove Clarence Thomas from office. And, you know, that’s just not happening. Republicans have rallied behind Thomas.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to go to Republican Senator Ted Cruz of Texas defending Clarence Thomas’s actions.

SEN. TED CRUZ: Well, if that’s the standard, going and traveling and being paid for by others, then guess what. Just about every Supreme Court justice has done so, and done so in much greater numbers. Justice Thomas was appointed in 1991. In the time since then, he has taken 109 reported trips, five international trips. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was appointed in 1993, two years later. In the time she was on the court, she took 157 trips, including 28 international trips. Mr. Payne, yes or no, do you think Ruth Bader Ginsburg was corrupt?

<KEDRIC PAYNE: No.

SEN. TED CRUZ: Nor do I.

AMY GOODMAN: That clip ended with Ted Cruz questioning Kedric Payne of the Campaign Legal Center, who testified at Tuesday’s hearing. Talk about the significance of this, and then, I mean, what kind of ethics code you think should be put in place for the Supreme Court. Aren’t federal judges now extremely angry around the country? They have much stricter rules.

IAN MILLHISER: Right. Yeah. Well, to respond directly to Ted Cruz, the standard is not that you can’t get reimbursed when you travel somewhere. You know, if a university wants to bring Justice Ginsburg or Justice Thomas, for that matter, to give a talk at that university, they’re allowed to pay for the justice’s flight and hotel room. That’s just a reimbursement, so the justice isn’t left to pay for a trip when they’re doing a favor for another institution. That’s fine.

What happened with Clarence Thomas isn’t that he is going to a university, giving a speech and getting his plane ticket paid for. What happened with Clarence Thomas is that he went on a lavish vacation to Indonesia, where he was flied on the private plane of a billionaire, you know, a very politically connected billionaire, and then he took his vacation on the billionaire’s superyacht.

And, you know, if Ted Cruz can’t tell the difference between being reimbursed for a work trip and having a lavish vacation paid for by this billionaire, I mean, I don’t even know how we can have a conversation with someone who doesn’t understand the distinction between those two things.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, as I mentioned federal judges, what kind of restrictions they have to abide by, I also wanted to ask you, speaking of the appointment of judges, about the growing calls for Senator Dianne Feinstein, the chair [sic] of the Judiciary Committee, to resign. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez recently said, quote, “Her refusal to either retire or show up is causing great harm to the judiciary — precisely where repro[ductive] rights are getting stripped. That failure means now in this precious window Dems can only pass GOP-approved nominees.”

IAN MILLHISER: Yeah.

AMY GOODMAN: Talk about what’s going on. I mean, we’re not just talking about shingles here.

IAN MILLHISER: Right, yeah. I mean, Dianne Feinstein is probably in the final years, or, if not in the final years, quite possibly in the final weeks or months of her life. She is ill. And her illness seems to prevent her from doing her job. And the concern is that, first of all, because she’s on the Judiciary Committee, her vote is needed to vote nominees out of the Judiciary Committee. There is a process, I believe, to discharge a nominee who does not get a Judiciary Committee vote, but it’s very time-consuming. It also means that on the floor, you know, with that 51st senator there, Democrats need either Kyrsten Sinema or Joe Manchin to vote for something if they want to pass a bill, if they want to confirm a nominee. Without Dianne Feinstein, they need both Sinema and Manchin. So they have to appease these two rather conservative members of this caucus who have idiosyncratic views. You know, Sinema tends to disagree with the Democratic Caucus in different ways than Manchin, and so it’s not always easy to wrangle both of them.

So it’s a serious problem that there is this seat that is essentially vacant right now. It’s the California seat. It’s the most populous state in the union, and it only has half as many senators as it should right now. You know, I mean, I think that the calls for Dianne Feinstein to resign are well founded at this point. You know, she has had a tremendous career, but the most important thing isn’t that Dianne Feinstein gets to die knowing that she died a senator. The most important thing is that the people of California have representation.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, what rules should be put in place, Ian, for the Supreme Court?

IAN MILLHISER: So, the rules would have to be really — some of the rules would have to be really complicated. I mean, some of them would be very simple. I think a simple rule, you know, you could do something like what the House of Representatives does, which says that if you accept a gift of more than $250, first of all, it would need to come from a personal friend or something like that. And second of all, some sort of body needs to review it to make sure that the gift isn’t in some way corrupting.

And then you’re going to have to have — you know, where it gets complex is you have to have serious conversations about, “OK, what if the justice has a spouse with their own career? How do we make sure that the justice’s work is walled off from their spouse so that one doesn’t influence the other?” You have to ask questions like, “OK, if there’s something like this land transaction with Neil Gorsuch, how do you make sure that an outside body reviews it to make sure that the transaction is at arm’s length, that the transaction was at fair market value, and that the justice wasn’t in some way enriched by whatever the transaction was?”

So, you know, it’s going to have multiple pieces to it. But again, the biggest crisis right now is that you have a justice accepting all of these lavish gifts from a billionaire, and whatever the rules say, that can’t possibly be allowed.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, I want to thank you, Ian Millhiser, for joining us, senior correspondent at Vox, author of the book The Agenda: How a Republican Supreme Court Is Reshaping America. And a correction: It’s not Dianne Feinstein who’s chair of the Judiciary Committee; it is Dick Durbin.

READ MORE  Former Fox host Tucker Carlson. (photo: Seth Wenig/AP)

Former Fox host Tucker Carlson. (photo: Seth Wenig/AP)

A message in discovery led to the eventual firing of the Fox News host, the New York Times reports

The message, discovered on the eve of the jury trial for Dominion Voting Systems’ defamation lawsuit against Fox News, reportedly led to the abrupt firing of Carlson — who hawked racist rhetoric on his show Tucker Carlson Tonight for years.

The former host reportedly sent the message on Jan. 7, 2021 to one of his producers after Trump supporters attacked the Capitol on on Jan. 6, 2021.

In the message, Carlson described how Trump supporters beat “an Antifa kid.” Carlson then expressed a desire to see the men kill the person he had described as the Antifa kid. “Jumping a guy like that is dishonorable obviously,” he wrote. “It’s not how white men fight. Yet suddenly I found myself rooting for the mob against the man, hoping they’d hit him harder, kill him. I really wanted them to hurt the kid. I could taste it.”

“Then somewhere deep in my brain, an alarm went off: this isn’t good for me,” Carlson continued. “I’m becoming something I don’t want to be. The Antifa creep is a human being. Much as I despise what he says and does, much as I’m sure I’d hate him personally if I knew him, I shouldn’t gloat over his suffering. I should be bothered by it. I should remember that somewhere somebody probably loves this kid, and would be crushed if he was killed,” Carlson continued, per the report. “If I don’t care about those things, if I reduce people to their politics, how am I better than he is?”

The previously unreported text was part of redacted court filings. Fox’s board reportedly worried that Carlson’s text would become public if he testified on the stand, and told Fox executives it was contracting a third-party law firm to review Carlson’s conduct.

Carlson, long the network’s foremost purveyor of white supremacist rhetoric and the “great replacement” theory, was ousted from Fox last week.

READ MORE

ADDED: THIS IS ONLY PART OF THE STORY!

Fox Has a Secret ‘Oppo File’ to Keep Tucker Carlson in Check, Sources Say

LINK Over the past two years, scores of rioters with military experience have been arrested in connection with the Capitol attack. (photo: Jason Andrew/The New York Times)

Over the past two years, scores of rioters with military experience have been arrested in connection with the Capitol attack. (photo: Jason Andrew/The New York Times)

Prosecutors say the former agent, who worked counterterrorism in the New York field office before leaving bureau in 2017, called police officers Nazis and illegally entered the Capitol.

The former agent, Jared L. Wise, was arrested on Monday and faces four misdemeanor counts, including disrupting the orderly conduct of government and trespassing, after agents received a tip in January 2022 that he had been inside the Capitol, according to a criminal complaint.

Mr. Wise, 50, told the police they were like the Gestapo, Nazi Germany’s feared secret police, the complaint said. When violence erupted, he shouted in the direction of rioters attacking the law enforcement officers, “Kill ’em! Kill ’em! Kill ’em!”

Mr. Wise raised his arms in celebration after breaching the Capitol in a face mask, and he escaped through a window, the complaint added.

Over the past two years, scores of rioters with military experience have been arrested in connection with the Capitol attack. But Mr. Wise is the rare former federal agent to have been charged. The F.B.I. said agents first found Mr. Wise living in New Braunfels, Texas, before he moved to Bend, Ore., in June.

Thomas E. Caldwell, a member of the Oath Keepers who was convicted in November of felony charges stemming from the Jan. 6 riot, had once worked with the F.B.I. And Mark S. Ibrahim, an active-duty agent for the Drug Enforcement Administration, was charged in July 2021 in connection with the riot. His case has not yet gone to trial.

The Justice Department’s investigation of the Capitol attack, already the largest it has ever conducted, has resulted in more than 1,000 arrests, with the possibility of many more to come.

From 2004 to 2017, Mr. Wise worked on counterterrorism matters at the F.B.I. in the New York field office. He was briefly detailed to Libya to help agents investigate the terrorist attack in Benghazi, Libya, in 2012, that killed four Americans. Mr. Wise left the bureau after his supervisors became unhappy with his work, and his career had stalled, a former senior F.B.I. official said.

Mr. Wise later joined the conservative group Project Veritas under the supervision of a former British spy, Richard Seddon, who had been recruited by the security contractor Erik Prince to train operatives to infiltrate trade unions, Democratic congressional campaigns and other targets.

At Project Veritas, according to a former employee with direct knowledge of his employment, Mr. Wise used the code name Bendghazi and trained at the Prince family ranch in Wyoming with other recruits. Mr. Wise took part in an operation against a teachers’ union and apparently left Project Veritas in mid-2018, the former employee said.

READ MORE  The logo for McDonald's is seen on a restaurant in Arlington, Virginia, January 27, 2022. (photo: Joshua Roberts/Reuters)

The logo for McDonald's is seen on a restaurant in Arlington, Virginia, January 27, 2022. (photo: Joshua Roberts/Reuters)

Agency investigators found the 10-year-olds who received little or no pay, the Labor Department said. The franchisees were fined $212,000 in total.

Louisville's Bauer Food LLC, which operates 10 McDonald’s locations, employed 24 minors under the age of 16 to work more hours than legally permitted, the agency said. Among those were two 10-year-old children. The agency said the children sometimes worked as late as 2 a.m., but were not paid.

“Below the minimum age for employment, they prepared and distributed food orders, cleaned the store, worked at the drive-thru window and operated a register,” the Labor Department said Tuesday, adding that one child also was allowed to operate a deep fryer, which is prohibited task for workers under 16.

Franchise owner-operator Sean Bauer said the two 10-year-olds cited in the Labor Department's statement were visiting their parent, a night manager, and weren't employees.

“Any ‘work’ was done at the direction of — and in the presence of — the parent without authorization by franchisee organization management or leadership," Bauer said Wednesday in a prepared statement, adding that they've since reiterated the child visitation policy to employees.

Federal child labor regulations put strict limits on the types of jobs children can perform and the hours they can work.

The Kentucky investigations are part of an ongoing effort by the Labor Department's Wage and Hour Division to stop child labor abuses in the Southeast.

“Too often, employers fail to follow the child labor laws that protect young workers,” said division Director Karen Garnett-Civils. “Under no circumstances should there ever be a 10-year-old child working in a fast-food kitchen around hot grills, ovens and deep fryers.”

In addition, Walton-based Archways Richwood LLC and Louisville-based Bell Restaurant Group I LLC allowed minors ages 14 and 15 to work beyond allowable hours, the department said.

READ MORE  Palestinian Khader Adnan, an Islamic Jihad spokesman who went on a 66-day hunger strike while he was imprisoned in an Israeli jail. Adnan died in Israeli custody early Tuesday. (photo: Majdi Mohammed/AP)

Palestinian Khader Adnan, an Islamic Jihad spokesman who went on a 66-day hunger strike while he was imprisoned in an Israeli jail. Adnan died in Israeli custody early Tuesday. (photo: Majdi Mohammed/AP)

Khader Adnan, a leader in the Islamic Jihad militant group, is the first Palestinian prisoner to die since Palestinian inmates began staging protracted hunger strikes about a decade ago. His death raises the potential for renewed violence between Israel and Palestinian militant groups as violence surges in the West Bank.

Shortly after his death was announced, Palestinian militants in the Gaza Strip fired a volley of rockets into southern Israel. Palestinians called for a general strike in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and protests were expected later in the day.

Palestinian prisoners have for years gone on lengthy hunger strikes to protest their detentions and to seek concessions from Israel. The tactic has become a last recourse for resistance against what Palestinians see as unjust incarcerations. The prisoners often become dangerously ill by refusing food but deaths are rare.

Palestinian prisoners are seen as national heroes and any perceived threat to them while in Israeli detention can touch off tensions or violence. Israel has often conceded to demands to release prisoners or shorten their sentences after they staged life-threatening hunger strikes.

Adnan, 45, began his strike shortly after being arrested on Feb. 5.

He had gone on hunger strikes several times after previous arrests. That included a 55-day strike in 2015 to protest his arrest under so-called administrative detention, in which suspects are held indefinitely without charge or trial.

Several Palestinians have gone on prolonged hunger strike in recent years to protest being held in administrative detention. In most cases, Israel has eventually released them after their health significantly deteriorated. None have died in custody, but many have suffered irreparable neurological damage.

Israel's prison service said Adnan had been charged this time with "involvement in terrorist activities" but had refused medical treatment while legal proceedings moved forward. It said he was found unconscious in his cell early Tuesday and transferred to a hospital where he was pronounced dead.

Palestinian groups called for a general strike in the Gaza Strip, Jerusalem and in cities across the West Bank on Tuesday, with schools and business closing for what organizers called a day of "general mourning."

The Israeli military said the missiles fired from the Hamas-controlled Gaza Strip fell in open territory, causing no damage. The Islamic Jihad militant group said in a statement that "our fight continues and will not stop."

Israel fought an 11-day war with Palestinian militants in Gaza, including Islamic Jihad, in May 2021.

Meanwhile in the West Bank, where Israeli-Palestinian violence has surged over the past year, Israeli officials said a suspected Palestinian shooting attack lightly wounded an Israeli man.

Israel is currently holding over 1,000 Palestinian detainees without charge or trial, the highest number since 2003, according to the Israeli human rights group HaMoked.

That figure has grown in the past year as Israel has carried out almost nightly arrest raids in the occupied West Bank in the wake of a string of deadly Palestinian attacks in Israel in early 2022.

Israel says the controversial tactic helps authorities thwart attacks and hold dangerous militants without divulging incriminating material for security reasons. Palestinians and rights groups say the system is widely abused and denies due process, with the secret nature of the evidence making it impossible for administrative detainees or their lawyers to mount a defense.

READ MORE  Photographer and oceanographer Anne De Souza photographs a forest of giant kelp near Monastery Beach in Carmel, California. (photo: Jennifer Adler)

Photographer and oceanographer Anne De Souza photographs a forest of giant kelp near Monastery Beach in Carmel, California. (photo: Jennifer Adler)

Kelp forests are majestic, life-sustaining ecosystems. Climate change imperils them.

Sink below the waves, however, and a whole other realm appears. Under the sea here, near Point Loma, is a forest as beautiful as any other. It’s made not of trees but of strands of giant kelp, a species of algae that can grow taller than a 10-story building.

Tethered to the seafloor and buoyed by air-filled chambers, the kelp strands undulate with the current, moving in slow motion. Schools of fish, seals, and other aquatic critters weave through the stalks like birds through a forest canopy.

“Diving into a forest is like descending into a cathedral,” Jarrett Byrnes, a marine ecologist at the University of Massachusetts Boston, said of kelp forests. Light from the surface filters through blades of kelp as if they’re stained glass, said Byrnes, who’s been diving kelp forests for more than 20 years. “It’s just amazing.”

Our planet has a number of great forests — the Amazon, for example, or the boreal forest of Canada and Russia. These iconic ecosystems not only support an incredible diversity of wildlife but store vast amounts of carbon that might otherwise heat up the planet. It’s not hyperbole to say that our existence depends on them.

But equally important are the forests of the sea. Found in cold waters across roughly a quarter of the world’s coasts, kelp forests are the foundation of many marine ecosystems. They underpin coastal fisheries, helping sustain the seafood industry. They also absorb enormous amounts of pollution and help sequester planet-warming gases. A recent study valued these benefits at roughly $500 billion a year, worldwide.

Yet for all they are worth, scientists know surprisingly little about kelp forests. Globally, data on how they’re responding to climate change and other threats, such as the spread of non-native species, is incomplete. Conservation efforts — which have been ramping up in recent years, especially on land — have largely overlooked these marine environments.

What biologists do know suggests that many of these forests are in trouble. And a lengthy new review published this week by the United Nations indicates that kelp forests have declined globally. “Kelp have suffered widespread losses across much of their range,” the report states — and climate change stands to make things worse.

The full story, however, is much more complicated.

A spectacular undersea world that we all rely on

Kelp forests have a lot in common with their land-based counterparts. They form three-dimensional structures that provide homes to animals. They often have a canopy. And kelp stalks themselves look a bit like trees: They have root-like anchors, a central structure similar to a trunk, and leaf-like blades.

Yet there are a few key differences. For example, kelp is not a plant but a kind of algae, a group of aquatic organisms in an entirely different kingdom of life (home to things like pond scum and Florida’s red tide). They also grow far faster than trees — as fast as two feet per day, depending on the species.

Some kelp species, like the giant kelp common off the coast of San Diego, reach the surface to form a canopy. Others top off many feet down, creating an understory. And these forests are quite widespread, covering an area of ocean up to five times greater than that of all coral reefs, according to the new report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

These forests support a stunning diversity of life. Kelp blades and anchors (known as holdfasts, the closest thing they have to roots) provide shelter for young fish, a place for adult fish to spawn, and food for invertebrates like urchins and other creatures. One study found that a single stalk of kelp in Norway supported roughly 80,000 organisms across 70 distinct species. Over 1,000 species of plants and animals are found in some kelp forests in California.

This is especially relevant for people who eat seafood. Research has demonstrated that many popular commercial species including pollack, lobster, and abalone spend at least part of their lives in kelp forests and depend on their existence. A new study in the journal Nature illustrates just how valuable these environments are to the seafood industry: A single hectare of forest contributes an average of roughly $30,000 a year to fisheries, the authors found.

The benefits don’t stop there! As they grow, kelp forests, like those on land, absorb a lot of pollution including fertilizer runoff from farmland and compounds of carbon (much of which enters the ocean from the atmosphere). They’re helping offset much of our planet-warming emissions, for free. The Nature study, which examined a handful of services that kelp provide, conservatively estimates that these habitats sequester at least 4.9 megatons of carbon from the atmosphere each year. “Pound for pound,” kelp remove as much as (or more) carbon than other ecosystems, such as terrestrial forests or mangroves, the study’s lead author, marine scientist Aaron Eger, told Vox.

Combined, the services provided by kelp forests globally — supporting fisheries, cleaning up pollution, and sequestering carbon — are worth half a trillion dollars a year, the study found. And that doesn’t take into account other potential benefits, such as coastal protection (kelp forests may tamp down waves, helping limit the impact of storms, the UNEP report found).

In short: Kelp help.

Are kelp forests at risk?

The simple answer is yes.

The most recent global analysis, based on data through 2012, found that global kelp forests are declining on average at a rate of about 1.8 percent per year. A more recent review that only considers long-term data (which is more reliable; kelp forests can vary a lot from year to year) points to a more troubling trend. It finds that more than 60 percent of the kelp forests scientists have studied over a period of 20 years or more have declined.

“On the whole, when we look at kelp forests over a long time period and in temperate latitudes, we’re seeing strong declines,” said Kira Krumhansl, a marine ecologist who led the global analysis and was a co-author of the more recent review. Those declines are most severe in regions closer to the equator where the water is warmer, such as Baja California, Western Australia, and southern New England, said Krumhansl, who works at Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

This pattern points to a major force behind shrinking kelp forests: climate change.

Kelp like to grow in cold, nutrient-rich water, yet rising global temperatures — fueled by power plants, gas-powered cars, and so on — are making the oceans warmer and fueling epic marine heat waves. That has pushed some kelp forests past their thermal limits, especially if they’re already in the warmer reaches of their range.

An added twist is that warm waters tend to hold fewer nutrients, which makes it harder for forests to grow, according to Byrnes, the biologist at UMass Boston.

Another reason why kelp forests have declined is overfishing and the loss of marine predators. Cod, lobster, and sea otters, among other animals, prey on sea urchins. Urchins, in turn, graze on kelp. When fishing nets capture urchin predators, urchins proliferate and mow down kelp forests.

This process can create what are called urchin barrens, eerie stretches of sea floor covered in little more than prickly orbs. You can find these barrens all over the world, from California to Tasmania to Japan. (Degraded kelp forests are also increasingly being replaced by mats of algae that form a turf on the sea floor and prevent the kelp from recovering.)

Two things that make the story of kelp more complicated

Although research shows that, on average, kelp forests are declining worldwide, some marine biologists are hesitant to make sweeping conclusions about the global trend.

One reason why is that kelp forests vary dramatically from place to place. Many forests have eroded or vanished entirely, though some seem to be fine or are even expanding. “Every spot on Earth has a different story,” said Tom Bell, a marine scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

A recent study co-authored by Bell documented steep declines in kelp forests along the West Coast, following a spate of intense marine heat waves between 2014 and 2016. While forests in parts of Northern and Central California have yet to recover these losses, some of those off the coast of Oregon have grown substantially.

“In some locations, we found jaw-dropping recovery in canopy-forming kelps,” said Vienna Saccomanno, a co-author of the recent study and ocean scientist at The Nature Conservancy, an environmental group. “These places are important glimmers of hope.”

Kelp forests also appear to be growing in parts of the Arctic. The ocean there is warming, making the water more tolerable for kelp (yet still cold enough for these algae to survive). Melting ice, meanwhile, frees up space for forests to take root. But this trend is not universal or well understood. Melting ice can also make the water cloudier, potentially limiting the growth of kelp forests.

Some parts of the ocean, including the coast of South Africa, are also anomalously cooling, causing kelp forests to increase, Byrnes said.

The other barrier to describing clear trends in kelp forests is a lack of data. Much of the planet’s kelp forests have yet to be mapped, and they’re rarely monitored, according to UNEP. The 2016 global analysis — which remains the most comprehensive assessment to date — only analyzed data for about a third of the regions home to kelp forests. Information is especially limited in places like the tip of South America and in parts of Africa, Byrnes said.

“The lack of information about certain parts of the world really worries me,” Byrnes said. “We don’t know what’s happening. And sometimes it can be alarming.”

Kelp forests are harder to monitor than most other ecosystems. Often, marine biologists get in the water and count kelp stands by hand, which is expensive, labor intensive, and requires some special skills. Kelp forests can extend for miles.

“It is a challenge to monitor [kelp forests], and that’s partly why they haven’t been as much of a focus for conservation or engagement,” Krumhansl said. “Nobody actually sees them. They’re not like a forest on land that you can walk through and see the changes happening for yourself.”

To an extent, tech is helping fix this problem. Instead of diving into a forest, scientists can now analyze images of the ocean taken by satellites for subtle changes in color that correspond to kelp forest canopies.

Bell’s recent analysis was based entirely on this approach. He used satellite-based data from Kelpwatch, a website he and other scientists designed to make this kind of data freely accessible. (You can do a similar analysis yourself on the website, though for now there’s only data for the west coast of North America.)

There’s one big caveat to this new era of kelp forest monitoring: Satellites, at least for now, can only detect canopy-forming kelp. And just a portion of kelp species form canopies, Byrnes said. That means we may not have a clear picture of these habitats for decades.

The future of kelp forests

In the years to come, kelp forests may still face a raft of problems including overfishing and the spread of invasive species. But none are likely to be more threatening to their long-term existence than climate change.

The oceans are warming, and marine heat waves — extended periods of abnormally hot temperatures — are almost certainly becoming more common. Since the 1980s, the frequency of marine heat waves has doubled, according to a 2021 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a UN group that studies warming.

That’s a problem for kelp, Krumhansl said. “They are cold-adapted species,” she said. “So the future doesn’t look great.”

Yet there are things that countries and environmental advocates can do to lessen the damage and give kelp forests a chance at survival.

One approach is to protect kelp forests with marine parks. Right now, these ecosystems are underrepresented in the world’s network of protected areas, according to UNEP, yet they’ve been shown to help kelp forests recover. By safeguarding marine predators, such as lobsters and sea otters, parks can keep urchin populations under control.

Another approach is to manually remove urchins from a reef — an activity that is oddly satisfying to watch — or kill them en masse with poison, which can be highly effective in restoring kelp forests, according to a recent review. (There are plenty of other approaches to kelp forest restoration and an entire organization working toward that cause.)

The good news is that when you take away some of these threats, kelp forests can quickly bounce back, Byrnes said. Kelp is resilient. And again, it grows incredibly quickly. “Kelp is just phenomenal,” Byrnes said. “As long as the conditions are right, it will grow and it will thrive.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.