Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The article below is satire. Andy Borowitz is an American comedian and New York Times-bestselling author who satirizes the news for his column, "The Borowitz Report."

According to the memo, written by the Fox News chairman, Rupert Murdoch, Carlson violated his contract by filling his texts with “premium fascist content” that should have been used on his show.

“The cable-news business is more competitive than ever,” Murdoch wrote. “Every drop of hatred and venom that our personalities produce must be deployed on their programs.”

The memo indicated that Carlson’s reckless decision to waste his most vividly racist comments in his texts has resulted in a policy overhaul at Fox.

“Going forward, there will be zero tolerance for any expressions of vile, abhorrent sentiments that Fox is unable to monetize,” Murdoch wrote.

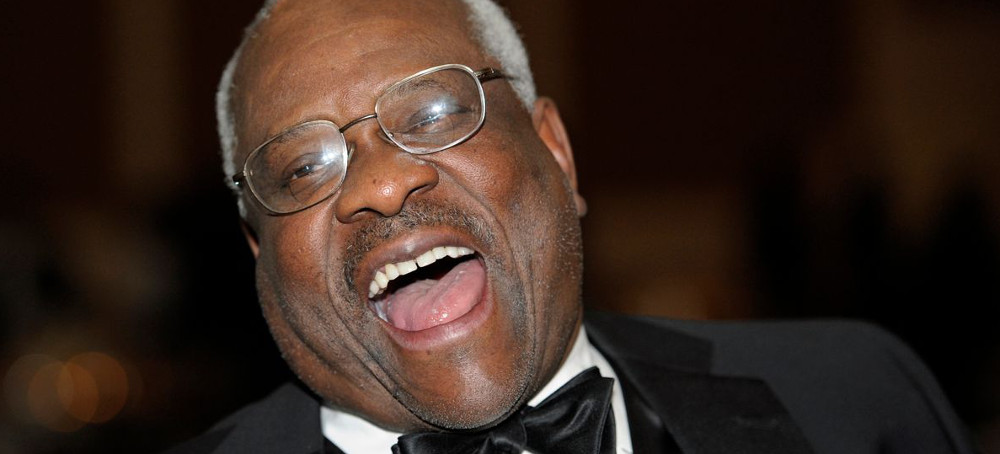

READ MORE  Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas laughs at a joke. (photo: AP)

Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas laughs at a joke. (photo: AP)

Who watches the philosopher kings with lifetime appointments?

Earlier this month, after ProPublica revealed that Justice Clarence Thomas frequently takes lavish vacations funded by billionaire Republican donor Harlan Crow, Thomas attempted to defend himself by claiming that this sort of “personal hospitality from close personal friends” is fine because Crow “did not have business before the court.”

As it turns out, that’s not true. As Bloomberg reports, the Supreme Court — including Justice Thomas — did briefly consider a $25 million copyright dispute involving a company that Crow was a partial owner of in 2005. At that point, Crow had already given a number of gifts to Thomas, including a $19,000 Bible that once belonged to Frederick Douglass.

As ProPublica later revealed, Crow even paid for the private school education of Thomas’s grandnephew, who Thomas said he is raising “as a son.” That includes tuition at a boarding school that charged more than $6,000 a month.

Similarly, if the rule is that justices must be extra careful when dealing with people who have business before the Supreme Court, then Justice Neil Gorsuch may also have violated this rule. According to Politico, a tract of land that Gorsuch owned with two other individuals was on the market for nearly two years before it found a buyer — nine days after Gorsuch was confirmed to the Supreme Court. The buyer was the chief executive of Greenberg Traurig, a massive law firm that frequently practices before the Supreme Court.

As Politico notes, “such a sale would raise ethical problems for officials serving in many other branches of government,” but the rules governing the justices are particularly lax.

There is a federal statute which requires all federal judges, including Supreme Court justices, to recuse themselves from any case “in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned,” but there is no effective enforcement mechanism to apply this vague law to a Supreme Court justice.

Meanwhile, while lower federal judges must comply with a lengthy Code of Conduct for United States Judges, the nine most powerful judges in the country are famously not bound by this code of conduct — although Chief Justice John Roberts has claimed that he and his colleagues “consult the Code of Conduct in assessing their ethical obligations.”

The result is that the nine most powerful officials in the United States of America — men and women with the power to repeal or rewrite any law, who serve for life, and who will never have to stand for election and justify their actions before the voters — may also be the least constrained officials in the federal government.

And much of the blame for this state of affairs rests with the Constitution itself.

The Supreme Court has resisted ethical reforms in the past

ProPublica’s report on Thomas’s vacations with his billionaire benefactor is hardly the first time Thomas has been in the news for ethically dubious behavior. It’s not even the first time he’s been in the news for ethically dubious behavior involving Harlan Crow!

The last time Thomas’s relationship with this billionaire made national headlines was probably 2011, after a series of news stories described some of the expensive gifts Thomas received from Crow and from organizations affiliated with Crow. That same year, Chief Justice Roberts used his annual Year-End Report on the Federal Judiciary to defiantly rebut calls to apply additional ethical rules to the justices.

Indeed, in his 2011 report, Roberts strongly implied that any attempt by Congress to ethically constrain the justices would be unconstitutional. The fact that the Code of Conduct applies exclusively to lower court judges, Roberts claimed, “reflects a fundamental difference between the Supreme Court and the other federal courts.”

The Constitution gives Congress the power to create lower federal courts, Roberts argued, and that empowers Congress to help oversee them. The Supreme Court, by contrast, is created by the Constitution itself, and that suggests that Congress has less power to constrain the justices.

Though Roberts wrote that the justices do voluntarily comply with some rules that apply to lower court judges, such as a federal law imposing “financial reporting requirements” on all federal judges, he rather ominously warned that the Supreme Court “has never addressed whether Congress may impose those requirements on the Supreme Court” — leaving the clear impression that his Court might start striking down ethical statutes if Congress insisted that the justices must comply with them.

Roberts also offered a practical reason why the justices are left to decide for themselves whether they should recuse from individual cases. If a federal trial judge refuses to recuse from a case that they are legally required to step away from, that decision “is reviewable by a court of appeals.” And if an appeals court judge commits the same error, that “decision not to recuse is reviewable by the Supreme Court.”

But there is no higher court than the Supreme Court, and thus nobody that can review a justice’s refusal to recuse from a case — Roberts wrote that this is “a consequence of the Constitution’s command that there be only ‘one supreme Court.’” And Roberts argued that it would be “undesirable” to allow a justice’s colleagues to review their decision not to recuse because the other justices “could affect the outcome of a case by selecting who among its Members may participate.”

To date, Roberts’s 2011 annual report is probably one of the two most compressive defenses a justice has offered for the very weak ethical constraints that currently apply to the Supreme Court — and that report reads as much as an implicit threat to strike down new ethical laws as it does as an actual argument in favor of the status quo.

The other document is a tone-deaf response to the latest round of scandals that reiterates many of the same points. Signed by all nine justices —both Republican and Democratic appointees — it, too, defends their behavior, claiming that “Justices have followed the financial disclosure requirements and limitations on gifts” established by the ethical rules that govern lower court judges.

Those rules prohibit a judge from accepting gifts from “any ... person whose interests may be substantially affected by the performance or nonperformance of the judicial officer’s or employee’s official duties” — a rule that, if taken seriously, would preclude any Supreme Court justice from taking virtually any gift, because the Supreme Court sets federal policy for the entire nation. Every single American’s interests may be substantially affected by the Supreme Court.

In any event, both Roberts’s 2011 report and the Court’s more recent statement on ethics portray the Supreme Court as a unique institution that cannot be constrained by the same ethical rules that apply to less powerful judges, especially when it comes to recusals.

Those rules prohibit a judge from accepting gifts from “any ... person whose interests may be substantially affected by the performance or nonperformance of the judicial officer’s or employee’s official duties” — a rule that, if taken seriously, would preclude any Supreme Court justice from taking virtually any gift, because the Supreme Court sets federal policy for the entire nation. Every single American’s interests may be substantially affected by the Supreme Court.

In any event, both Roberts’s 2011 report and the Court’s more recent statement on ethics portray the Supreme Court as a unique institution that cannot be constrained by the same ethical rules that apply to less powerful judges, especially when it comes to recusals.

In 2004, the late Justice Antonin Scalia was asked to recuse from a case involving then-Vice President Dick Cheney, after Scalia invited Cheney to join him for an annual duck hunting trip (Scalia and Cheney wound up flying down to the trip together on Air Force Two). In refusing to recuse from the case, Scalia conceded that his recusal might be warranted “if I were sitting on a Court of Appeals” because lower federal judges who recuse from a case may be replaced by a different judge. On the Supreme Court, by contrast, “the Court proceeds with eight Justices, raising the possibility that, by reason of a tie vote, it will find itself unable to resolve the significant legal issue presented by the case.”

Additionally, Scalia argued that it would be “utterly disabling” to require justices to recuse from cases involving “the official actions of friends” within the federal government, because justices tend to be well-connected individuals with lots of friends in high political office. “Many Justices have reached this Court precisely because they were friends of the incumbent President or other senior officials,” Scalia wrote, warning that a too-low bar for recusal would force many justices to recuse from the large number of Supreme Court cases where a president or cabinet secretary is a party.

As a descriptive matter, Scalia is undoubtedly correct that the way to become a justice is to have lots of friends in high places. But that does not change the fact that Scalia argued that the nine justices must be the final word on disputes involving their personal friends and close political allies.

The Constitution makes it virtually impossible to discipline or remove a corrupt Supreme Court justice

Roberts’s 2011 report is correct about one thing: One major barrier preventing Congress (or anyone else) from imposing meaningful ethics reforms on the Supreme Court is the Constitution itself.

The Constitution provides that federal judges shall “hold their offices during good behaviour,” a provision that’s widely understood to require a judge to be impeached before they can be removed from office. And the impeachment process requires two-thirds of the Senate to vote to remove a justice from office — meaning that, in the current Senate, 16 Republicans would need to vote to remove Thomas, even if the GOP-controlled House agreed to begin an impeachment proceeding against him in the first place.

(Although a 2006 paper published by the Yale Law Journal argues that this understanding of the Constitution is wrong, that paper concedes that there is a “virtually unquestioned assumption among constitutional law cognoscenti that impeachment is the only means of removing a federal judge.”)

Similarly, the Constitution provides that all federal judges shall receive “a compensation, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in office.” So Thomas or another justice cannot have their salary reduced because they behave unethically, or have their pay docked to cover the cost of expensive gifts received from wealthy benefactors.

And there’s also another provision of the Constitution that effectively immunizes justices from any meaningful consequences so long as they remain loyal to the political party that put them in office to begin with. Federal judges are chosen by a partisan official, the president of the United States, and confirmed by other partisans in the Senate.

That means that both parties have an extraordinary incentive to appoint ideologically reliable judges to the courts, and to protect them. Once a staunch conservative like Thomas (or Gorsuch) is in office, Republicans have an overwhelming incentive to keep that justice in his seat regardless of whether the justice behaves unethically. This is especially true right now, when Democrats control both the White House and the Senate, and thus could replace Thomas with his ideological opposite.

The entire system is set up, in other words, in a way that rewards political parties that treat the judiciary as a partisan prize. It encourages presidents to appoint reliable partisans to the Supreme Court whenever they get the chance to do so. And, because neither party is likely to control 67 Senate seats any time soon, it also gives each party a veto power over any attempt to remove a justice — even if that justice is corrupt.

There are better ways to design a judiciary

The US federal system is unusual in that it makes it so easy for partisans to capture the judiciary. Many states, and many of our peer nations, have vastly superior systems that make it much harder for either political party to capture the judiciary, and that make it far less difficult to remove a judge who is unfit for office.

One alternative to allowing partisan elected officials to choose judges is a merit-selection commission like the one used in the United Kingdom and in many US states.

In the British system, for example, Supreme Court justices are selected by a commission consisting of the Court’s current president, a senior member of the judiciary, and representatives from local judicial selection commissions in England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. The Lord Chancellor, a cabinet official, does have a single-use veto that they can use to reject the commission’s first choice for a Supreme Court appointment. But, if the Chancellor exercises that power, they cannot block the commission’s second choice.

Similarly, many US states use a system like the “Missouri Plan” to choose judges. Under Missouri’s judicial selection process, a seven-person commission includes “three lawyers elected by the lawyers of the Missouri Bar ... three citizens selected by the governor, and the chief justice, who serves as chair.” When a vacancy arises on the state supreme court, the commission selects three names and forwards them to the state governor, who must choose one of those three candidates within 60 days or else the commission will make the final decision.

Such commissions are not always 100 percent effective in removing partisanship from the judiciary — Arizona’s Missouri-style commission, for example, enabled the state’s former Republican governor to appoint at least two right-wing justices to the state supreme court. But they are better than the US federal system, where judicial selection is determined solely by partisans.

The idea behind these commissions is that judges should be selected by multi-member bodies that are difficult for one party to capture. In Missouri, for example, a majority of the seats on the commission that picks justices are controlled by the nonpartisan state bar or by a chief justice who was selected using this commission.

And they often work quite well in identifying competent judges that are acceptable to both political parties. In 2009, for example, then-Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin, a Republican, appointed Judge Morgan Christen to her state’s supreme court, after Christen was recommended by a Missouri-style commission. Democratic President Barack Obama later appointed Christen to a federal appeals court.

At least some states also have systems that allow supreme court justices to be disciplined or removed from power if they violate ethics rules or otherwise abuse their office.

Alabama, for example, has a nine-member body known as the Judicial Inquiry Commission, which is empowered to file charges against state court judges — including justices of the state supreme court — who engage in misconduct. These charges are then heard by a special Court of the Judiciary, which has the power to sanction or even remove state supreme court justices from office.

Like the Missouri Plan, Alabama’s system is not immune to partisan capture — it is still at least theoretically possible that the Court of the Judiciary could be filled entirely by rabid partisans. But there are two fairly prominent examples of Alabama’s system disciplining an out-of-control conservative judge even in this deeply red state.

Because of this system, Alabama twice stripped former Chief Justice Roy Moore of his judicial authority — once because Moore refused to follow a federal court order requiring him to remove a monument to the Ten Commandments from the state’s judicial building, and a second time because he told state probate judges to defy a US Supreme Court decision permitting same-sex couples to marry.

One virtue of Alabama’s system is that it keeps disputes about whether a judge or justice should be suspended or removed from office within the judiciary itself, thus obviating concerns that the legislature or executive might threaten judicial independence by bringing removal proceedings against a judge because they disagree with the judge’s decisions. Alabama’s Court of the Judiciary is made up entirely of judges who also serve on other courts within the Alabama judicial system.

All of which is a long way of saying that there are ways to design a constitution that preserves judicial independence, disciplines justices who behave unethically, and that, at the very least, diminishes partisanship within the judiciary. But we do not have that system at the federal level, and that’s why we’re stuck with justices like Clarence Thomas.

READ MORE  A few dozen Dream Defenders occupy the outer areas of the office suite of Gov. Ron DeSantis at the Florida Capitol on Wednesday, May 3, 2023, in Tallahassee, Florida. (photo: Ana Ceballos/Miami Herald)

A few dozen Dream Defenders occupy the outer areas of the office suite of Gov. Ron DeSantis at the Florida Capitol on Wednesday, May 3, 2023, in Tallahassee, Florida. (photo: Ana Ceballos/Miami Herald)

The Florida legislature passed a series of bills to defund diversity, equity, and inclusion programs at public colleges, and expand the state’s controversial “Don’t Say Gay” law

On Wednesday, the Florida legislature passed a series of bills that will defund diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, restrict professors from discussing issues of race and ethnicity, and prohibit schools from compelling teachers and staff from using a student’s preferred gender pronouns. DeSantis is expected to add his signature to the bills in the coming days.

In response, dozens of protesters from the human rights group Dream Defenders, occupied DeSantis’ Tallahassee office for a sit-in. “DeSantis likes to meet with his donors, the people who voted with him, his little pals, but he seems not to want to face the people who don’t actually like him,” one protester told the Tallahassee Democrat. “If he won’t face us, he shouldn’t be the governor.”

After hours in the Capitol, the protesters were arrested and forcibly removed from the premises, which could earn them a trespassing charge and a one-year ban from the Capitol grounds.

In a 27-12 party-line vote in Florida’s Republican-controlled Senate, they approved a massive expansion of the controversial “Dont Say Gay” bill, which was signed into law last year. The existing bill placed widespread restriction on discussions regarding issues of sexual and gender identity in K-12 classrooms.

The new law requires that all public schools treat it as a matter of policy that “a person’s sex is an immutable biological trait and that it is false to ascribe to a person a pronoun that does not correspond to such person’s sex.” Teachers would not be allowed to tell their students their own preferred gender pronouns, nor can teachers inquire about students’ pronoun preferences.

Additionally, the bill raises the hard ban on classroom instruction on issues of sexuality and gender identity from the third grade up to the eighth grade.

A separate bill, also passed on Wednesday, bars Florida’s public universities and colleges from using their funding to “promote, support, or maintain any programs or campus activities that espouse diversity, equity, or inclusion [DEI] or Critical Race Theory rhetoric.”

The wording of the bill has raised concerns that it will be weaponized against students and schools to prohibit academic courses, affinity groups, clubs, sororities and fraternities, or student unions associated with minority communities. An amendment proposed by State Rep. Angie Nixon to provide protections to some of these groups was struck down by House Republicans.

The bill would also create a governor-appointed board empowered to hire and fire university and college staff, including those with tenure.

In March, The American Historical Association wrote a public letter outlining their concerns regarding the legislation.

“We express horror (not our usual ‘concern’) at the assumptions that lie at the heart of this bill and its blatant and frontal attack on principles of academic freedom and shared governance central to higher education in the United States,” the letter states. “This is not only about Florida. It is about the heart and soul of public higher education in the United States and about the role of history, historians, and historical thinking in the lives of the next generation of Americans.”

READ MORE  South Carolina state senator Sandy Senn, a Republican, makes a last-minute argument before the senate passes an abortion ban in September 2022. (photo: Sam Wolfe/Reuters)

South Carolina state senator Sandy Senn, a Republican, makes a last-minute argument before the senate passes an abortion ban in September 2022. (photo: Sam Wolfe/Reuters)

As states continue to bring in tighter restrictions on abortion, internal divisions within the GOP are starting to show

As states continue to bring in tighter restrictions on abortion following the fall of Roe v Wade, internal divisions within the Republican party on the issue are starting to show.

Divisions became most apparent last week in the deep red states of South Carolina and Nebraska, where Republicans roundly rejected further attempts to curtail abortion rights last week.

In South Carolina on Thursday, all five female senators – three of them Republican – led a filibuster that ultimately blocked a bill which would have banned abortion from conception with very few exceptions.

That was the third time a near-total ban on abortion has failed in the Republican-dominated senate in South Carolina since Roe was overturned last summer.

“We told them, ‘Don’t take us down this path again for the third time in six months – you will regret it.’ And so we made them regret it,” said state senator Sandy Senn, who spoke at length on the senate floor on Thursday, of the male Republican senators continually pushing abortion restrictions in her state – including in an earlier attempt this year to make abortion a crime punishable by the death penalty. Abortions remain legal until 22 weeks in the state, which has become a safe haven for abortion in a region with increasingly limited options.

With nothing having changed since the last two times the senators brought the bill, Senn said her Republican counterparts knew another abortion ban had no hopes of passing. But with an election looming in 2024, she believes they are keen to flaunt their anti-abortion positions.

“He was just trying to flex his Republican credentials,” she said of Shane Massey, the senate leader, who voted in favor of the bill. “He wants people to know, ‘I want a strict ban, I want no abortion. I’m going to try it for the third time and lose, but it’s not my fault that we lost – it’s these Republicans who voted against me.’”

In Nebraska, an attempt to bring a six-week abortion ban failed by a single vote in the majority Republican chamber. Merv Riepe, a Republican senator who had initially co-sponsored the bill chose to withhold his vote on Thursday, becoming an unlikely player in the bill’s demise, having voted in its favor as recently as two weeks prior.

But Riepe had raised hesitations about the bill back in March, telling local press that six weeks might not be enough time for a person to realize they are pregnant and get an abortion.

He did propose an amendment to the bill on Thursday, proposing a ban on abortion after 12 weeks, but other Republican legislators rejected it, saying they had already compromised enough.

Barrett Marson, a GOP strategist based in Arizona, said that these increasingly visible tensions may speak to a difficulty that Republicans are having trying to balancing different wings of the party.

“There is a tension between the base of the Republican party and moderate Republicans. The hardcore base wants outright bans on abortion. But the broader electorate, and certainly a substantial amount of right-leaning independents and moderate Republicans, want to keep abortion legal but rare,” said Marson.

Those tensions are certainly becoming clear on the national stage, with growing numbers of Republicans sounding the alarm that the party should not lean too far right on abortion, especially since last year’s midterms showed a string of victories for abortion rights that seem to suggest the party’s stance on the issue is out of sync with the general public.

Recent weeks have also seen a number of Republican presidential hopefuls trying to walk back the party’s stance on abortion. Last week, the former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley asked the party for a “humanizing, not demonizing” conversation on abortion. Donald Trump has indicated he thinks a federal abortion ban – touted by Senator Lindsey Graham last year – a losing proposal for 2024.

Following a supreme court decision to keep access to a crucial drug in medication abortions widely available for the time being, the Republican congresswoman Nancy Mace said told ABC she agreed with the ruling.

“I want us to find some middle ground,” Mace said. “I represent a very purple district … As Republicans, we need to read the room on this issue, because the vast majority of folks are not in the extremes,” she said.

Mace criticized a recent decision by the Florida governor, Ron DeSantis, to sign a six-week abortion ban in his own state – a bill she said he “signed in the dead of the night”.

“We are going to lose huge if we continue down this path of extremities … [People] want exceptions for rape and incest, they want women to have access to birth control. These are very commonsense positions that we can take and still be pro-life,” Mace said.

Senn’s own decision to join the filibuster in South Carolina, she said, was about principle – but she added that the politics are also compelling.

“As far as in my state, 53% of the Republican voters agree with me. And in my district, 70% agree with me,” she said.

“I don’t want any woman to have an abortion. I hope she doesn’t have to, but I’m not going to judge her. And she has to have a meaningful opportunity to make her decision,” she said.

Senn supports a ban after 12 weeks, with exceptions for people who have been raped, victims of incest, or whose life is threatened by a pregnancy – and said she continues to be shocked by fellow Republican who disagree with that stance.

“The baby is not even a baby at that point. In my state, 19 lawmakers in our house of representatives signed on to a bill that would make a woman guilty of murder if she had an abortion at any stage,” she said, referring to a recent bill. “I just wish we had more people in the middle, with common sense on all issues. And on this issue, why not have some mercy?” she asks.

Marson, the strategist, believes the mixed messaging from the party could end in catastrophe for Republicans in 2024 if they don’t heed those calls.

“We don’t have to guess what will happen. Just a little over six months ago, we saw what the issue of abortion does to the electorate – it pushes them to Democrats,” he said.

“We’ve seen states like Kansas, one of the more conservative states in the country, reject abortion bans. A six-week ban that doesn’t allow for exception of rape and incest and life of the mother – that’s a campaign-ender for a Republican,” he said.

READ MORE  Steve Kirsch, a tech entrepreneur turned anti-vaccine activist, at a conference in Atlanta for future COVID and vaccine-related litigation that he helped organize and fund. (photo: Lisa Hagen/NPR)

Steve Kirsch, a tech entrepreneur turned anti-vaccine activist, at a conference in Atlanta for future COVID and vaccine-related litigation that he helped organize and fund. (photo: Lisa Hagen/NPR)

Recently, he stood before a gathering of more than 250 lawyers in Atlanta while wearing a custom black T-shirt designed like a dictionary entry for the phrase "misinformation superspreader."

"Our definition is it's someone who's basically pointing out the truth and it just happens to disagree with the mainstream narrative we're known as misinformation spreaders, because what they're trying to do is they're trying to control the narrative," Kirsch told NPR.

By "they," Kirsch means a network of pharmaceutical companies, governments, doctors and journalists that he argues are covering up a pandemic-driven plot to poison the world for profit.

The scientific consensus shows COVID vaccines are safe and significantly reduce the chances of death or serious illness. While many Americans may share a distrust of pharmaceutical companies and healthcare systems, there is no evidence of the kind of conspiracy alleged in these circles.

In recent years, Kirsch has become an increasingly vocal and generous funder of the anti-vaccine movement. He helped organize and fund the conference to map out strategies for anti-vaccine and COVID-19-focused litigation as the pandemic winds down.

Their proposed targets include hospitals, school systems, medical licensing boards and, the holy grail, pharmaceutical companies that make vaccines.

"My goal is to expose every single one of these a**holes," Kirsch told the audience, to uproarious applause.

The lawyers met as the anti-vaccine movement is at a crossroads. The COVID-19 pandemic brought in new energy and supporters but is fading from public life. On May 11, the federal government's public health emergency will expire. To keep the cause alive, some in the movement are trying to build up a legal arm.

The legal conference drew a mix of people who've advocated against vaccines for years before the pandemic, and those, like Kirsch, who are more recent converts. He said he actually got two Moderna shots when COVID vaccines became available.

Kirsch's path to the conference started with an effort to find treatments for COVID.

From funding research to organizing lawyers

"When the pandemic hit, I put in a million dollars of my own money and raised another $5 million dollars. We started the COVID 19 Early Treatment Fund and we started funding early treatments," said Kirsch.

The goal was to run trials on existing treatments that might help combat the virus. Reporting by MIT's Technology Review found the project had brought together highly respected biologists and drug researchers who believed in the work. But when some of the research seemed to run into dead ends, Kirsch reportedly began to clash with the scientists he was funding.

"If the data is is is bad and doesn't make sense and the study was badly done, then I have a right to reject it," said Kirsch. "And so the point is that if a study is well done, you'll see that I will like the study."

Kirsch has a tendency to offer large sums of money to anyone willing to debate his assertions.

"But they won't do that. They won't get into any discussion with me because they don't want to answer a single question," Kirsch said.

Jeffrey Morris has tried to engage with Kirsch for years. In his spare time, the professor of biostatistics at the University of Pennsylvania has gone line by line through some of Kirsch's claims, providing answers, context and explanations. They once had a long conversation over Zoom.

"And it was an interesting discussion, you know, because he admitted that he was not a scientist and didn't think like one. And so I was trying to connect with him and help him understand the leaps he was making in his arguments to get him to think more carefully. Because I could tell he was someone with a lot of energy and passion on the issue," said Morris, who has watched Kirsch pull millions of views on some of his COVID vaccine content.

When someone makes a dramatic claim that vaccines are killing millions, it's their burden to show the evidence, said Morris, not the other way around.

"They're presuming that they have the entitlement that what they're saying can be presumed to be true without them demonstrating rigorously that it's true, and that it is the responsibility of society and the scientific community to prove them wrong. And if they fail to prove them wrong, or if they don't show up, then they're really offended. And then to them, that just proves their guilt. It proves the cover up," he said.

As government cover ups became a regular talking point for Kirsch, the researchers abandoned his early treatment project. Two years and $2 million later, he's hoping to organize a sustained legal insurgency against public health agencies, drug manufacturers, hospitals and schools.

Attorney Pete Serano traveled from Washington State, where he represents three doctors accused of spreading false statements about COVID-19 and said finding a supportive community of lawyers and experts he can call for help is "monumental."

"You know, it really felt like it was me against the world, even though there were probably maybe half a dozen to a dozen lawyers in Washington fighting. It still feels - it's extremely lonely. It's extremely difficult," said Serano.

Conference organizers asked reporters not to record entire presentations. But one thing Serano and other attendees heard again and again from speakers: In this room, you're among heroes.

"There are people who are tremendously intellectually talented and gifted in so many ways who are using those talents to fight for your rights, to fight for my rights," said Serano.

Creating a new body of law

The fights include everything from suing educators who enforced mask mandates, to demanding vaccination status be made a protected class, like race or sexual orientation. Thousands of lawsuits pushing back against public health measures have been filed since the pandemic.

The goal of this conference is to bring lawyers behind these suits together, study all that legal spaghetti on the wall and analyze what has and hasn't worked. They mean to probe for weak points in the law, build a network of experts and plaintiffs, and, they hope, inspire new laws.

Conference organizers like attorney Warner Mendenhall want to ensure a steady supply of lawyers who see opportunity, whether ideologically aligned with the anti-vaccine movement or not.

"I hate to say this but greed is good in this instance," said Mendenhall on a webinar promoting the event. "So if lawyers can see that they can get rich, and we're trying to prove that you can - we haven't yet, but we will - it'll bring lawyers in simply for the money."

Fears about vaccines are not new. The current legal structure around vaccines is the result of a wave of lawsuits in the 1970s and 80s. It tries to balance individual freedom with public health needs, according to Anjali Deshmukh, a pediatrician and professor of administrative law at Georgia State University.

"It's not only about protecting us, but it's about protecting our community. And that's a different calculus, where it's now within the government's interests to make sure that these diseases are not spreading," Deshmukh said.

But the law is not fixed, she added, and well-funded, well-organized groups can be a powerful force.

"And I think like we saw with Roe v Wade, you had a case that was passed 50 years ago and then had various chips away at it until the ground crumbled," said Deshmukh.

The civil rights movement, organized labor and women's rights advocates have also relied on a potent mix of court battles and ground campaigns to sway public sentiment.

"The court of public opinion is more important than I think we give credit to in both law and medicine. We can have all the science in the world, we can have laws that make sense, but laws change. Science is not always convincing when you're coming from a place of fear," said Deshmukh.

Cases don't even have to succeed in court to have an impact, Deshmukh said. Influencers and headlines can frame settlements, technical legal outcomes or compelling, emotional testimony as victories for one side or another. She said these lawsuits also come at a time when the Supreme Court is weakening the powers of many regulators.

With the COVID national emergency order set to end, keeping COVID-related grievances alive in the courts may also help sustain the larger movement against vaccines.

Serano, the lawyer from Washington State, says the kinds of cases that brought him here may become the bulk of his work for years.

"I plan on being that 80 year old guy talking about what it was like in the 2020s and COVID 19 and telling some young whippersnapper lawyer about how we did it back when," he said.

READ MORE  Next week marks the first anniversary of the killing of Shireen Abu Akleh, a Palestinian-American journalist who was fatally shot by Israeli forces on May 11, 2022. (photo: Ammar Awad/Reuters)

Next week marks the first anniversary of the killing of Shireen Abu Akleh, a Palestinian-American journalist who was fatally shot by Israeli forces on May 11, 2022. (photo: Ammar Awad/Reuters)

Department of State official reiterates US is pressing Israel to ‘review its policies’ after Al Jazeera reporter’s killing.

At a news briefing on Wednesday, which coincided with World Press Freedom Day, Vedant Patel repeatedly told reporters that Washington is seeking accountability by asking Israel to review its military rules of engagement.

“[Reviewing] rules of engagement sounds like it’s something to deter and prevent this [from] happening again,” one visibly frustrated journalist said. “Is there an active effort of the US seeking accountability from Israel?”

Patel responded, “There is an active effort. And since Shireen’s tragic death, we have continued to press Israel to closely review its policies and practices on rules of engagements and consider additional steps to mitigate risk of civilian harm and protect journalists.”

Next week will mark the anniversary of the killing of Abu Akleh, a Palestinian-American reporter who was fatally shot by Israeli forces on May 11, 2022, while covering a military raid in the city of Jenin in the occupied West Bank.

Al Jazeera Media Network said that day that she was “assassinated in cold blood”.

But Washington has rejected efforts to seek accountability for the killing at the International Criminal Court (ICC), drawing condemnation from press freedom and Palestinian rights advocates who have called on US President Joe Biden’s administration to demand justice.

Israel, which rights groups accuse of imposing a system of apartheid on Palestinians, receives at least $3.8bn in US security assistance annually.

Adam Shapiro, director of advocacy for Israel-Palestine at Democracy for the Arab World Now (DAWN), a US-based rights group, said Washington’s response to the killing of Abu Akleh has been “pathetic from the start”.

He told Al Jazeera on Wednesday that the Biden administration’s approach to the case has been to “express thoughts and prayers” while trying to “make it go away”.

‘Unintentional’

Although the US has not conducted its own investigation into the case, Patel said on Wednesday that the killing of Abu Akleh was “unintentional”. He did not provide any evidence to back up that assessment, which echoed Israel’s claims.

Several investigations by rights groups and media outlets, as well as witness accounts, have cast doubt on the assertion that Abu Akleh’s killing was accidental, noting that she was identifiable by her press gear when she was fatally shot.

Abu Akleh also was not in the immediate vicinity of any fighting, the reports found.

Washington called for accountability in the case early on and said the journalist’s killers “should be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law”.

However, after Israel acknowledged that there was “high possibility” its army fired the shot that killed Abu Akleh but ruled out a criminal investigation into what happened, US officials appeared to drop the call for prosecuting the perpetrators.

Israeli leaders also openly rejected US requests to review its military’s rules of engagement last year. “No one will dictate our rules of engagement to us,” then-Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid said.

Israeli and US media outlets reported in November 2022 that the FBI had launched an investigation into the killing, and Israeli officials have ruled out cooperating with the purported probe. The US Justice Department has declined to confirm the investigation.

Earlier this week, Democratic Senator Chris Van Hollen sent a letter to Secretary of State Antony Blinken urging the release of a new report on the incident drafted by the United States Security Coordinator (USSC).

Last year, the USSC — which oversees and encourages security cooperation between Israeli and Palestinian officials — said the Israeli military “was likely responsible for the death of Shireen Abu Akleh”.

It added, however, that there was “no reason to believe that this was intentional but rather the result of tragic circumstances”.

The statement was not a result of a full investigation, US officials said at the time, explaining that it served as a summary of Israeli and Palestinian probes. A Palestinian Authority investigation had said weeks earlier that Israeli forces deliberately fired at Abu Akleh “with the aim to kill”.

On Wednesday, Patel at the State Department said he has not seen the new USSC report, but his understanding is that it came to the “same conclusion”.

“I don’t have any additional updates or assessments to offer on this report,” he said.

World Press Freedom Day

Earlier on Wednesday, US officials paid tribute to journalists on World Press Freedom Day, taking the opportunity to renew calls for the release of Wall Street Journal reporter Evan Gershkovich, who is imprisoned in Russia.

“Journalism is not a crime — it is fundamental to a free society,” Biden said in a statement that failed to mention Abu Akleh.

Blinken also released a statement decrying attacks on reporters and calling for the immediate release of Gershkovich, whom Washington has formally designated as wrongfully detained. The top US diplomat did not mention Abu Akleh, either.

Blinken also joined Washington Post columnist David Ignatius for an event marking World Press Freedom Day, but the killing of the Al Jazeera journalist was not raised in their 30-minute discussion.

“President Biden and Secretary Blinken omitting the Israeli military’s brutal murder of Shireen Abu Akleh during World Press Freedom Day shows a dehumanizing disregard toward Palestinians, as well as a weak commitment by this administration to freedom of the press,” Ahmad Abuznaid, executive director of the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights, told Al Jazeera in an email.

Shapiro, of DAWN, also described Washington’s failure to mention Abu Akleh in official statements on Wednesday as “utterly outrageous”.

“I think, for Shireen, it’s undoubtedly because it was Israel who killed her that the United States wants it to go away,” he said. “But the fact that she was also from Al Jazeera is a secondary factor that I think shouldn’t be ignored.”

READ MORE  The egg industry brutally grinds up billions of male chicks each year because they can't lay eggs. But new tech could change that. (photo: Adobe Stock)

The egg industry brutally grinds up billions of male chicks each year because they can't lay eggs. But new tech could change that. (photo: Adobe Stock)

The egg industry brutally grinds up billions of male chicks each year because they can’t lay eggs. But new tech could change that.

While the female chicks go on to lay the more than 1.2 trillion eggs humans consume annually, 6.5 billion male chicks each year are hatched, only to be quickly snuffed out. That’s because they don’t lay eggs, so they’re of no use to the egg industry, and because they don’t grow as big and fast as other chicken breeds, they’re of no use to the chicken meat industry. Even though culling costs egg producers an estimated $500 million a year, it makes more economic sense to just kill the males on day one, rather than spend an additional dollar raising them.

Undercover investigations into hatcheries have drawn some public attention to male chick culling, enough that in recent years a number of European countries, including Germany and France, have gone so far as to ban the practice, giving hatcheries and egg producers a few options: raise male chicks for meat (albeit inefficiently), raise “dual-purpose” breeds (ones that lay a relatively moderate number of eggs and grow to a moderate size), import hens from neighboring countries, or shut down operations.

But there’s another option: They can use emerging technology to identify the sex of the chick while still in the egg so they can destroy it before it hatches, before the chick can feel pain.

That last possibility has gained momentum in recent years. Since 2019, five companies have managed to commercialize in-ovo — meaning in egg — sexing technology that enables them to identify the sex of the chick around either day nine or day 12/13 from when the egg incubation starts, depending on the approach. Such advances have already saved tens of millions of male chicks from being born, only to be swiftly culled. It’s estimated that 10 to 20 percent of Europe’s hen flock now comes from cull-free hatcheries.

But there’s a catch: Scientists believe that chick embryos could potentially feel pain as early as day seven of their 21-day incubation period. That means that even with the most advanced in-ovo sexing, male chick embryos could still be experiencing suffering.

A new preprint study, funded by the German government and conducted by researchers at the Technical University of Munich, provides some evidence that chicken embryos may not be capable of feeling pain until much later in the incubation period, after day 12.

Researchers applied potentially painful stimuli like heat and electricity to chicken embryos from day 7 to day 19 of their 21-day incubation, measuring their heart rate, blood pressure, brain activity, and movement, all in an effort to uncover whether the stimuli translated to experienced pain. Brain activity only began on day 13, movement from beak stimulation increased significantly on day 15, blood pressure increased significantly on day 16, heart rate jumped on day 17, and body movement increased significantly on day 18.

The findings arrive at a critical juncture for the effort to end the annual shredding and gassing of 6.5 billion male chicks. Beginning in 2022, Germany required hatcheries to destroy male chick embryos prior to hatching, and starting in 2024, German hatcheries must destroy eggs containing male embryos before day seven of incubation. That would require in-ovo sexing technology that works earlier than any company has yet been able to commercialize.

As a result of the new study, however, Germany’s Ministry of Food and Agriculture has suggested the government will instead require hatcheries to destroy eggs before day 13, which means the companies that cull at days 9 and 12 are in the clear (France’s ban on chick culling, which went into effect in January of this year, starts on day 15).

The study also provides clarity to policymakers elsewhere — Italy’s ban goes into effect in 2026 but doesn’t yet stipulate a cull-day threshold, while the European Commission is expected to eventually ban the practice continent-wide.

But the German study may not be the final word. Future research could determine the pain threshold to be sooner or later than day 13.

“We have to see whether this will become the new consensus or whether more confirmatory research has to be performed,” said Matthias Corion and Simão Santos, leading in-ovo sexing researchers at the MeBioS division from the Department of Biosystems at the University of Leuven in Belgium, over email to Vox.

Animal advocates are cautiously optimistic. “I think that we need to be very flexible,” said Sharon Nuñez Gough, president of Animal Equality, an animal rights group that has campaigned in Europe to end male chick culling. “I think if [German policymakers] move it up to day 13 it’s wonderful ... but there could be studies that come out in a couple of years that say no, it’s actually day 11 or it’s actually day 10.”

Jörg Hurlin, managing director of in-ovo sexing company Agri-AT noted over email to Vox that the study leaves the door open to pain perception beginning even later: “[T]he scientists only say that from the 12th day of incubation, a pain sensation can no longer be excluded, but they do not prove it either.”

Despite the scientific and political tailwinds behind efforts to phase out male chick culling, they face strong headwinds with the global egg industry under pressure to take on other costly issues, like converting barns to cage-free and bringing record prices down amid high inflation and a deadly bird flu outbreak that has resulted in the death of tens of millions of hens.

Those challenges aside, ending the culling of 6.5 billion male chicks is a critical and doable low-hanging win for animal welfare — if the technology can further advance.

There’s more than one way to sex an egg

One thing the in-ovo sexing field has going for it is that there are so many ways to identify the sex of chickens before they hatch, which is why some 13 companies and academic teams have sprung up over the last decade to turn their theories into workable technology.

Some companies employ noninvasive imaging to look inside the egg, which is what Agri-AT uses in its Cheggy machine, scanning 20,000 eggs per hour at nine hatcheries across Europe. It’s fast and low-cost, but it only works for brown eggs, and it identifies the sex on day 13 — meaning the embryos could feel pain — though it can stun them prior to killing them, rendering them insensitive. It can also work on day 12, though it’s less accurate. The company is currently trialing a new approach with researchers at the Technical University of Dresden to identify the sex as early as between day four to day six of incubation.

Orbem, another company that uses noninvasive imaging, recently deployed its technology in a French hatchery and says it works on day 12 and for both white and brown eggs.

Another approach is allantoic sampling, which entails making a tiny hole in the egg and extracting fluid for rapid analysis, not unlike the amniocentesis tests used on pregnant people. It’s nearly 100 percent effective as of around day eight or nine of incubation, though it’s slower and costlier than the imaging technology. Three companies in Europe have commercialized this approach and grocery shoppers in Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and elsewhere in Europe can find both eggs and egg-based products under the Respeggt brand that come from supply chains free of male chick culling, with an additional cost of around one to three Euro cents per egg or more. (Aldi, one of the largest grocers in Europe and Germany, has pledged to phase out male chick culling from its egg supply in Germany, but declined to answer questions about the status of its progress.)

And there are other approaches in the innovation pipeline. Late last year, an Israeli research center successfully gene-edited DNA into chickens so that when their eggs are exposed to blue light, the DNA is activated and the development of male embryos stops. Gene editing is potentially much cheaper and faster (once the technology is fully developed) than the other approaches, but it likely faces steep political hurdles: Many European countries have slow regulatory processes for genetically edited food, and the same consumers who might be willing to pay extra for cull-free eggs could balk at a gene-editing process. It’s worth noting, however, that the eggs consumers eat won’t be genetically altered — female embryos are genetically left untouched.

“Farmers will get the same chicks they get today and consumers will get exactly the same eggs they get today,” one of the Israeli researchers told the BBC.

The promising if shaky start to the end of male chick culling

Despite the burst of innovation, experts say no single approach has yet met all six criteria hatcheries require to scale up: the ability to process a high volume of eggs (20,000 to 30,000) per hour, effective for both white and brown eggs, 98 percent or higher accuracy, low cost, sex identification early in the incubation period, and high hatchability rates. That has kept the egg industry from fully adopting any of them, and while regulation is coming down the pike (or already in place), lack of clarity about which day of incubation will be the cut-off further complicates matters.

“There is always a trade-off somewhere,” said Corion and Santos over email. “Hatcheries are reluctant to adopt a technology right away because these technologies are still in development and when they invest, they want it to hold for years.”

Robert Yaman of Innovate Animal Ag, a new organization based in the US that aims to speed up the development of animal welfare technology, said that while in-ovo sexing isn’t where it needs to be, it will get there.

“With any sort of industrial agricultural technology, it just takes time to roll out,” Yaman said. “Once the technology is ready, you’re not going to see it in every country around the world the next day. It’s going to take time to manufacture the equipment, to work on those commercial partnerships. And so I think if you look at the rate of progress and speed of uptake, it’s actually going very well.”

While it’s impressive that an estimated 10 to 20 percent of Europe’s hen flock now comes from cull-free hatcheries, a shift that occurred from 2019 to 2023, there have been some unexpected consequences to Germany and France’s laws.

Public policy often lags behind technological change, but the case of male chick culling is the opposite: Germany banned the practice in 2019 (the ban went into effect in 2022) when the technology was just starting to go online in European egg hatcheries. While the technology has been adopted relatively quickly, and policymakers have moved uncharacteristically fast on the issue, many egg companies are holding out until the technology develops further — and have found loopholes around the law in the meantime.

According to the German magazine Der Spiegel, many male chicks hatched in Germany were raised for meat, and at least 300,000 male chicks have been hatched and transported to other countries to be raised for meat, including Poland, where animal welfare standards are weaker. Many German egg producers are importing egg-laying hens from the Netherlands to stock their farms.

France’s ban went into effect at the start of 2023, but egg producers received permission to continue culling male chicks from white chicken eggs as complying with the ban required the allantoic sampling approach, which is costlier. (Most eggs in France are brown; white eggs account for just a little over 10 percent of the egg supply — however, the company Orbem, which just launched, can sex both brown and white eggs). One animal rights group called the carve-out a “betrayal.”

The US, by contrast, has moved far slower on the issue, with the only significant contribution coming from the Foundation for Food … Agriculture Research — an organization that collaborates with industry and academia — and its Egg-Tech Prize, which is offering up to $6 million in prizes to in-ovo sexing researchers and startups. Open Philanthropy, a foundation that funds animal welfare initiatives, contributed up to $3 million to the contest.

In 2016, the United Egg Producers (UEP) — the US egg industry’s main trade group — called for the elimination of male chick culling by 2020, but in 2021 said, “[A] method that meets the food safety, ethical standards and scalable solutions needed for the United States is not yet available.” UEP declined responding to questions, but did recently tell Ag Funder News that nothing had changed since its 2021 statement. This means that American consumers, unlike their European counterparts, have no real way to buy eggs free of the taint of culling.

However, USPoultry — an organization representing egg and poultry trade groups, including UEP — donated toward the Egg-Tech Prize in 2020.

“You tend to think of the US as an innovation leader and technological leader but I think this is one area where we’re kind of falling behind,” Yaman said.

Carmen Uphoff, COO of Respeggt, said the company hopes to expand into the US soon and help pioneer a new higher-welfare egg category, like organic or cage-free.

“Hatcheries don’t like to do chick culling, it’s just they didn’t have any other solutions until now,” she said, later adding, “The technology is actually there and could be ordered ... the market is ready.”

As is the case with so many other animal welfare issues, the US is lagging years behind Europe. If that holds true on the matter of ending the brutal culling of billions of male chicks, America’s egg supply probably won’t have cull-free eggs anytime soon. But if the technological and political progress continues at the pace it has, it could only be a matter of time until in-ovo sexing isn’t just the more ethical choice for US egg producers, but also the more economical one.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.