Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The Manhattan District Attorney faces huge legal and political challenges, but the former President’s antics could help the prosecution’s case.

Assuming that Trump is indicted, Kravis and other former prosecutors said that whoever is appointed as the judge in the case, as well as the prosecutors, cannot ignore one type of comment from Trump: threats of violence against participants in the trial. A former prosecutor who asked not to be named but who was involved in the trial of a Trump associate told me that, if Trump makes statements that could incite physical attacks on the judge and prosecutors, or intimidate jurors, he could be held in contempt of court. Trump, throughout his Presidency and the two years since, has repeatedly disparaged judges and prosecutors who investigated him and his allies, declaring them to be corrupt and part of a “deep state” plot against him. In a fund-raising e-mail sent to supporters on Monday, he suggested that they are part of “George Soros’ globalist cabal of thugs.” Trump has also called Bragg, who is Black, a “racist.”

The former prosecutor said that Trump’s rhetoric could make Manhattan jurors reluctant to serve in a trial, fearing that they could face attacks from his supporters. “You could have jurors fearing physical harm if they serve on the case and fear that their identities will be revealed,” the former prosecutor said. “Judges are very sensitive about their courtrooms feeling unsafe.”

The judge could impose a limited gag order on Trump regarding his public statements about the trial. If Trump were to defy such an order, the judge could then take the extreme step of holding him in contempt of court and even jailing him. Kravis noted that Roger Stone, at one point in his case, posted a photo on social media of the judge, Amy Berman Jackson, which appeared to have the crosshairs of a gun next to her face. Berman Jackson subsequently barred Stone from posting on social media. Stone, known for his embrace of political dirty tricks dating back to Richard Nixon’s reëlection campaign, was ultimately convicted of seven felonies, including obstructing a congressional investigation and making false statements to Congress. Trump, before leaving office, commuted Stone’s three-year prison sentence and set him free.

Kravis said that prosecutors were unlikely to request a gag order, given that it would play into the former President’s narrative that he is being persecuted by Democrats who are trying to prevent him from running for President again. The situation, of course, is unprecedented. But Trump could use his position as a former President, and as the current front-runner for the 2024 Republican Party nomination, to make it more difficult for a judge or prosecutors to try to limit his public comments about his own trial. “For someone like Trump, who is a candidate for office, restricting their speech is different,” Kravis said. “It’s generally not a good look to be going into a court and asking for an order that prevents the defendant from making public statements about the case. In that circumstance, it's an even worse look.”

Sarah Isgur, a Trump critic who formerly served as the spokesperson for the Justice Department, under Attorney General Jeff Sessions, said that Bragg and his prosecutors should try to speak and conduct themselves in a manner that is the opposite of the former President’s habit of bombast and bullying. State bar rules in New York and elsewhere limit what prosecutors can publicly say about a defendant before and during a trial, in order to prevent jurors from being biased and to insure a fair trial. But prosecutors can hold press conferences after an indictment is released. Isgur urged Bragg to do just that. “This is your one chance to look like a human being, and to explain the charges in human terms,” she said. “You want to sound calm, unemotional. You want to just explain. You don’t want to try and sway.”

Isgur also said that, during the trial, prosecutors should not take steps that publicly humiliate Trump. When the former President is arraigned, for example, law-enforcement officials should not handcuff him, publicly release his mug shot, or parade him in front of the press, in a perp walk. “I wouldn’t do the handcuffs. I wouldn’t do a mug shot. I wouldn’t do the perp walk,” Isgur said, arguing that it would fuel a group that she referred to as “the beast”—online partisans who want to focus on what they see as biased and vindictive prosecutors. She added that Bragg “can’t win against the beast, so he should at least try to starve the beast.” (Trump’s mug shot, whatever Bragg’s wishes, is bound to be leaked. Trump, though, will likely blame Bragg.)

A former senior Justice Department official who asked not to be named agreed that Bragg should strictly obey rules barring prosecutors from publicly disparaging defendants. He said that in high-profile cases it is more important than ever to obey standard practices. “The prosecutors should emphasize that the defendant is presumed innocent and the charges are only allegations,” the former official said.

Trump, given his past behavior, is likely to behave badly. The legal rules and traditions that restrict Bragg’s conduct do not apply to him. His relentless attacks on Special Counsel Robert Mueller, an esteemed former prosecutor and F.B.I. director, swayed public opinion against both Mueller and the F.B.I. Outside the courtroom, in particular, Trump vs. Bragg will be a vast mismatch, with Trump running circles around prosecutors in the press. Kravis pointed out, though, that Trump’s public statements outside the court can be used against him during cross-examination, if he testifies. He said Bragg’s best hope may be that Trump’s conduct backfires with the jurors and voters. “A defendant’s public statements can be helpful,” he said. “They’re all admissible.”

READ MORE The Atlanta police foundation has helped Atlanta become the most surveilled city in the U.S. (photo: Elijah Nouvelage/Reuters)

The Atlanta police foundation has helped Atlanta become the most surveilled city in the U.S. (photo: Elijah Nouvelage/Reuters)

Exclusive: Roark Capital and Silver Lake Management showed to have a web of connections to the Atlanta police foundation

Private equity refers to an opaque form of financing away from public markets in which funds and investors manage money for wealthy individuals and institutional investors such as university endowments and state employee pension funds.

Research shared exclusively with the Guardian details links between Roark Capital, an Atlanta-based private equity firm which owns the country’s second-largest restaurant company, Inspire Brands, and a corporate backer of the Atlanta police foundation (APF).

Paul Brown, the CEO of Inspire Brands, whose portfolio includes fast-food franchises Dunkin’, Baskin Robbins and Arby’s, sits on the board of trustees of the APF, which is raising $60m from corporate funders to build Cop City in the Atlanta forest previously earmarked for a public park.

Police foundations are non-profits which raise private money from individual and corporate donors that is funnelled to police departments with little oversight or accountability. The APF has previously helped Atlanta police fund recruitment drives, surveillance cameras and Swat team equipment.

The police crackdown on community protests against Cop City have led to dozens of charges of domestic terrorism and the police killing of the environmental activist Manuel Paez Terán, known as “Tortuguita”. Police said Paez Terán shot at them first, but have not produced any body-cam or other video footage of the shooting.

The APF has helped Atlanta become the most surveilled city in the US in large part thanks to a program called Operation Shield.

The Silicon Valley firm Silver Lake Management, one of the world’s largest tech-focused private equity firms, has invested more than $1bn in Motorola Solutions, which designed and implemented the surveillance system for Operation Shield, according to a new report by the Private Equity Stakeholder Project (PESP).

Motorola has been criticised for providing hi-tech surveillance equipment used in US prisons, on the US-Mexico border and in the West Bank. Several European pension funds have divested from Motorola, and it was included in a UN list of companies “that had raised particular human rights concerns” by providing surveillance tools and other services to the Israeli government.

Operation Shield currently boasts more than 12,800 private and public interconnected cameras monitored by the police – the highest number per capita in the country. Motorola has sold more than $22m worth of products and services to the Atlanta police department since 2016.

Silver Lake Management has invested money from pension funds paid into by Texas and Ohio teachers and South Dakota and California state employees, according to PitchBook.

In 2022, Silver Lake added Shadowbox Studios (formerly Blackhall Studios), a television and film studio company, to its portfolio with a $500m investment. The studios are located south of the Cop City site.

At an APF meeting on the Cop City budget in February, the agenda included what appeared to be a discussion on a possible future relationship between Shadowbox and the APF. The meeting agenda included the following item: “Are there any scenarios where we can come up with some agreement to work with Shadowbox for them to help fund some components and in return they have access to use the facility for filming purposes?”

There is no evidence that Shadowbox had any knowledge of the agenda item or that it has contributed in any way to the APF.

“We’ve shown that private equity does have its hands in the controversy that is unfolding around Atlanta and its police force. Knowing the relationships Roark Capital and Silver Lake Management have with Cop City, [the Atlanta police department] and APF will give activists another tool to demand accountability for the recent violence and the destruction of the Georgia environment,” said Amanda Mendoza, PESP researcher and co-author of the report.

The private equity industry manages about $11tn globally. Asset managers and funds buy and restructure companies including startups, franchises, troubled businesses and real estate operations using their clients’ money. Yet unlike banks and other publicly listed companies, private equity firms are exempt from most financial disclosure rules, making it extremely difficult to track their assets – or risks.

It means people such as firefighters, nurses and teachers whose pensions are invested in private equity funds have little way of knowing if their retirement nest egg is financing police surveillance equipment, defence contractors, hospitals or coal plants.

The report Private Equity Profits from Destroying the Atlanta Forest is the latest attempt by researchers to uncloak the industry’s activity.

Roark Capital mostly invests in franchises like fast-food chains and in February 2023 claimed $33bn in assets under management. The company has lobbied against a federal minimum wage, and a 2020 report by the Government Accountability Office found employees at some Roark brands were among the most frequent recipients of food stamps in some states.

After protests swept across the US in response to the 2020 police killing of George Floyd, Inspire Brands CEO and APF board member Paul Brown posted a letter on LinkedIn calling attention to “violence” and “attacks” by protesters – without mentioning the police violence that triggered the protests. (Roark’s own CEO donated thousands of dollars to the former Georgia senator David Perdue as he promoted the big lie and sought to overturn the 2020 presidential election.)

Another Roark connection is Marshall Freeman, who for seven years served as chief operating officer of the APF and sits on the board of the Inspire Brands Foundation, the company’s philanthropic arm. Freeman has joined the Atlanta police department as a deputy chief administrative officer.

Roark has invested money from several public worker pensions funds, including those of firefighters and police in Colorado, Los Angeles city employees, Oregon and New York state workers, and Louisiana teachers, according to PitchBook.

“The enormous amounts of money at the disposal of private equity often comes from state employees and retirees, who would be very surprised to learn where their investments are going. That’s why it’s important to follow the money,” said Charles Mahoney, associate professor of political science at California State University who researches private equity investments in defence and national security.

Roark Capital did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Silver Lake declined to comment.

Atlanta is the US’s 38th most populous city, according to the 2020 census. The APF, a non-profit whose corporate backers also include UPS, Home Depot, Wells Fargo and Coca Cola, is the second-largest police foundation in the country after New York City.

According to LittleSis, a corporate finance watchdog group, “police foundations act as a backchannel for corporate and wealthy interests by funding policing even further, adding to already overinflated budgets without any required public oversight, approval, or accountability.”

The Atlanta police department was allotted a third of the city’s $700m budget in 2022, and has received additional money through the APF to expand its surveillance capacity and recruit more officers.

Less than a week after Atlanta police shot and killed Rayshard Brooks in the summer of 2020, the APF gave every officer in the city a $500 bonus.

The APF received a record $11.7m in donations in 2021, a figure likely to rise since Georgia passed new legislation expanding personal tax breaks last year. In addition to funding the police directly, the city has also given the APF more than $3.6m since 2016 for Swat team equipment, licence plate readers and thousands of cameras for Operation Shield.

Mendoza said: “When it comes to policing, which already faces severe accountability and transparency issues, private equity involvement adds an additional layer of opaqueness. This report is just scratching the surface in investigating how private equity has contributed to not only moving these dangerous projects forward but also supporting a devolving situation of violence in the city.”

Paez Terán was part of a broad social movement that opposes the $90m Cop City training complex planned for 85 acres of the South River forest, one of Atlanta’s largest remaining green spaces. The social movement also opposes plans to develop 40 acres of public park in the same forest.

Paez Terán’s death was the first known killing by police of an environmental activist in the US. The police crackdown has continued since his death amid growing local opposition to Cop City. Community concerns include increasing police militarization and excessive force especially against Black residents, as well as losing part of a forest that had been included in 2017 plans to create what would have been the city’s largest

READ MORE Irina Zherebkina makes a final visit to Kharkiv National University's Center for Gender Studies, which she co-founded nearly thirty years ago. (photo: Mila Teshaieva/The New Yorker)

Irina Zherebkina makes a final visit to Kharkiv National University's Center for Gender Studies, which she co-founded nearly thirty years ago. (photo: Mila Teshaieva/The New Yorker)

Irina Zherebkina, who spent the first year of the war under bombardment in Kharkiv, still believes that peace must be imagined into being.

Irina and Sergey, who are sixty-three and sixty-five, respectively, live in a conspicuously neat and bright apartment in central Kharkiv. They have a white dining table, white couches, and white built-in bookcases, which seem to alleviate the heft of books, shelved tightly and stacked on most surfaces. The first time I visited, Irina had a burn on her cheek. During a recent power outage, she had slipped while using a candle to light her way to the bathroom.

Before the war, the Zherebkins didn’t know their neighbors. The building was heavy with the wealthy and the well connected, including several retired high-ranking military officials, and the philosophers didn’t feel at home among them. But once the war began the few people who remained in the building formed tight bonds. They pooled their resources to get food when most stores were closed and venturing outside was perilous. During air raids, a neighbor sometimes took shelter in the Zherebkins’ apartment—they have a big bathroom without windows. Like everyone in Kharkiv, the couple had learned to distinguish types of munitions by ear, and had established a hierarchy among them. Grad rockets, which make a terrifying whistling sound before impact, are more frightening than S-300 rockets, even though the S-300 does more damage. It makes its presence known only when it hits, with a loud bang: there is no time for dread.

In the early days of the war, Irina wrote an essay in the Boston Review, placing Vladimir Putin’s war in the context of what the philosopher Judith Butler has called “new fascism,” a global phenomenon that legalizes the “freedom to hate.” Irina called on the world not to conflate Putin and the Russian people, many of whom, she argued, didn’t support the war. It was important to reclaim and rejuvenate the ideas of solidarity and internationalism in order to fight Putin, she wrote.

Two days after the essay was published, a rocket hit close to the Zherebkins’ apartment building, and they decided to leave the city. They drove out to the countryside, in the direction of their dacha, a modest weekend cottage, but a bridge along their route had been blown up—they later learned that Ukrainian forces had destroyed it to make passage more difficult for the Russian troops. Irina and Sergey ended up in a house that belonged to an acquaintance. Several other families were also staying there, each occupying a bedroom. Unlike their dacha, the building had heat and running water. They encountered a kind of war fever in the countryside, a performance of war. Local men had put on uniforms and armed themselves. In anticipation of battle, some spent their days drinking and exchanging news. This was in the spring of 2022, when news seemed meaningful, when the course of the war seemed unpredictable, before everything, including bombs, became monotonous. After a month, Irina and Sergey returned home, to Kharkiv.

By then, Butler had read Irina’s essay, and proposed co-hosting an online international feminist conference on the war. With Sabine Hark, a German sociologist, they envisioned a panel of speakers that would include Ukrainian feminists, Western supporters, and Russian and Belarusian antiwar dissidents. Some Ukrainian feminists objected to including Russians and Belarusians. In the lead-up to the conference, arguments grew heated. Irina’s message about solidarity, internationalism, anti-nationalism, and nonviolence had inspired the event, but in wartime it suddenly seemed less than obvious. In the end, the conference included one Russian and one Belarusian participant.

Irina grew up in Chișinău, the capital of Moldova. She had wanted to be a philosopher since she was in seventh grade. “She wanted to change the structure of society,” Sergey said. They met at university, in Kyiv, and eventually found their intellectual home with a group of philosophers led by Valery Podoroga, a prolific postmodernist scholar whose former graduate students are now some of Russia’s best-known philosophers. After the Soviet Union broke apart, and even after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014, Irina and Sergey maintained relationships with colleagues and friends in Moscow, and continued to write and publish in Russian. Much to their relief, none of their Russian friends have supported Putin’s war. They feel relief, too, that Podoroga didn’t live to see this war: he died in 2020.

“For him, Michel Foucault was the most important writer,” Irina said.

“His ‘Discipline and Punish’ was the most important book,” Sergey said.

“And now they say Foucault is ‘propaganda of homosexuality,’ ” Irina said, referring to Russian propaganda that’s been used, among other things, to justify the war in Ukraine.

After university, Sergey got a job teaching in Kharkiv; Irina joined him there a few years later. In 1994, she co-founded the Center for Gender Studies at Kharkiv National University, which she modelled on gender-studies centers at American and British universities. She assumed that it would be one of many such centers in the post-Soviet, post-totalitarian world—none of Russia’s biggest universities had gender-studies programs—but the center in Kharkiv remained one of only a handful. Irina, Sergey, and their colleagues translated foundational Western texts into Russian, and Irina co-founded a summer school in gender studies that took place in Crimea and drew participants from Ukraine, Russia, other former Soviet colonies, and beyond. Kharkiv is a city of universities and colleges—more than forty of them—and was, before the war, home to hundreds of thousands of students, including tens of thousands who came from other countries. The center thrived there.

Nine years ago, Irina had a stroke. She believes it was her body’s response to the news of the first death at the protests that ultimately led to the Revolution of Dignity. Irina heard that the victim, a young man of Armenian descent, had been shot in the back of the head, and she feared that he’d been shot by one of the other protesters. (No evidence that this was the case has since emerged.) She collapsed.

“Many people died of heart attacks at that time,” Sergey said.

“Two of our neighbors have died of heart attacks since this war started,” Irina said.

Now, as a feminist philosopher and an anti-nationalist living in and thinking about war, Irina was troubled by feminist colleagues’ rush to mobilize around nationalist rhetoric. She was also unsettled by some well-meaning foreign supporters. In May, the philosopher Paul B. Preciado came out against supplying arms to Ukraine. “We don’t have to send weapons,” Preciado wrote. “We need to send peace delegations to Russia and Ukraine. We must peacefully occupy Kiev, Lviv, Mariupol, Kharkiv, Odessa. We all have to go. Only millions of non-Ukrainian and unarmed corps can win this war.” Writing on Facebook, Irina acknowledged that Preciado’s proposed strategy was consistent with Butler’s philosophy of nonviolence, but objected that the proposed strategy “implied a discriminatory, racist division of human lives into ‘Ukrainian’ and ‘non-Ukrainian,’ those that are more and less significant, or, in Butler’s terms, more and less grievable.” By suggesting that Putin wouldn’t bomb millions of “non-Ukrainians,” Preciado seemed to be conceding that millions of Ukrainians were bombable. (“I have never objected to Ukrainian self-defense,” Butler told me. The conference “was very difficult for people who espoused nonviolence, because we also saw the necessity of Ukrainian military self-defense against Russian aggression. If the implication is that I, like Preciado, object to sending arms to Ukraine, that would be emphatically wrong.”)

After the invasion, the university went fully online. (Some classes had been virtual since the beginning of the covid-19 pandemic.) All of Irina’s graduate students, many of whom have children, left Kharkiv—some to go abroad, others for safer parts of the country. International students left the country, too. This, in turn, meant that the university lost much of its funding. In August, 2022, the university didn’t renew her contract. Soon after Irina lost her job, the London School of Economics offered her a position. She worried this meant that, as an academic from war-torn Ukraine, she was now, as she put it to me in a text, a “marketable commodity.”

She also worries that university education in Ukraine is, meanwhile, being relegated to the status of a luxury. And she worries that a series of laws has restricted Ukrainians’ access to books in Russian, by Russians, or published in Russia. That list inevitably includes much contemporary philosophy, including the Zherebkins’ own writing and translations: Irina and Sergey are not Russian, but they have written in Russian and published in Russia. Last year, Irina, like all university instructors who had not themselves been educated in Ukrainian, had to sit for a Ukrainian-language exam. She enjoyed studying for it, even though she hates being told what to do, and when and where to show up. She went in for the exam and aced it. That day, February 21st, Putin delivered a speech asserting that there was no such thing as a Ukrainian people or Ukrainian language.

Irina worries that Volodymyr Zelensky, the President of Ukraine, is amassing dictatorial powers. Martial law has been in effect in Ukraine since the start of the full-scale invasion; Zelensky has used martial law to regulate broadcast television and ban several opposition parties. Perhaps even more important, Ukrainians have all but stopped criticizing the government. But it is a philosopher’s job to think critically and speak naïvely. At the online conference co-organized by Butler, Irina suggested that Zelensky is living in a state of terror, and facing an impossible choice. He cannot choose to negotiate because he must submit to the will of the people, who want to keep fighting the war. Irina believes that peace must be made, imagined into being. Even at a gathering of feminist thinkers, this was not a popular statement.

A couple of weeks after my last visit with Irina and Sergey, I was at Rutgers University, listening to a speech by Nadya Tolokonnikova, a founder of the Russian protest-art group Pussy Riot. Tolokonnikova recalled that, as a philosophy student in Moscow a dozen years ago, she had been looking for feminist philosophy in translation. (She had tried and failed to read Butler in the original English.) She finally found translations by the Zherebkins and learned of the existence of the Kharkiv Center for Gender Studies. I texted Irina. She responded several hours later: “Well, that means there is a point to continuing to do what we do. As soon as we have heat, water, and electricity again.” Russia had unleashed a barrage of rockets. There had been no light for much of the preceding two days.

I asked how she and Sergey were managing. “We are talking to each other, as we always do,” Irina responded. “They bring water about in trucks and we fill cannisters.”

Irina had told me that the London School of Economics had set a deadline for her arrival: March 16th. I asked when they were planning to go. They’d leave on March 14th, Irina said—the last possible day.

“I am ashamed to be leaving when my country is under bombardment,” she added.

Irina and Sergey took the train on March 14th, from Kharkiv to the Polish border town of Chełm, got a ride from Chełm to Warsaw, and boarded a plane there, arriving in London on the evening of March 16th, to just meet their deadline. At the last minute, Keti the cat was denied boarding in Warsaw and had to stay with an acquaintance there, until a way to transport her to London was found.

“It’s hard to get used to living without the bombing and air-raid sirens,” Irina texted me. “We miss our neighbors, who don’t have the option to leave, and we feel guilty. We can’t wait to get back to Kharkiv after this accursed war is over.”

READ MORE  Donald Trump faces scrutiny in other ongoing investigations that could come with charges of their own. (photo: Bernard Smailowski/AFP)

Donald Trump faces scrutiny in other ongoing investigations that could come with charges of their own. (photo: Bernard Smailowski/AFP)

The proceedings — from New York, Georgia and the federal Department of Justice — all have the potential to upend the 2024 presidential race, in which Trump has already announced his candidacy.

Trump has survived plenty of investigations already — remember the Mueller investigation? How about the Ukraine impeachment inquiry? — but criminal charges, and a subsequent arrest, could have a dramatic effect on his 2024 campaign. Never before has a former president been charged with a crime.

Here are the active investigations:

The Stormy Daniels hush money investigation (Manhattan District Attorney's Office)

This criminal case centers on a $130,000 hush money payment to Stormy Daniels, an adult film actor, made just before the 2016 election in order to quiet her allegations of an affair with Trump.

Daniels, whose real name is Stephanie Clifford, says that she and Trump had an affair at a celebrity golf tournament in 2006. As Trump's campaign for president picked up steam, she offered to sell her story to gossip magazines. In October, executives at the National Enquirer, a publication long friendly to Trump, alerted Trump's personal lawyer, Michael Cohen.

Cohen reached an agreement with Daniels to pay her $130,000 in exchange for keeping her story quiet. Her attorney received the money from Cohen on Oct. 27, less than two weeks before the election.

After Trump was elected president, Cohen was reimbursed with a total of $420,000, to account for taxes and other costs. Some of the reimbursement checks were signed by Trump himself, who has admitted to repaying Cohen for money paid to Daniels. He has denied having the affair.

According to court records, the Trump Organization's top executives falsely identified the reimbursements as a "retainer" for "legal services."

Now, the grand jury is examining whether Trump committed a felony under New York state law by falsifying business records to cover up another crime — like the violation of campaign finance laws with the hush money payment.

The case is being brought by Alvin Bragg Jr., who was elected district attorney of New York County in 2021. He took over the case from his predecessor, Cyrus Vance Jr., who had opened a broad criminal inquiry into Trump's business activities while Trump was still president.

Earlier this month, reports emerged that prosecutors in the Manhattan district attorney's office had offered Trump the chance to testify before a grand jury. In New York, that's usually a signal that charges are coming soon, as potential defendants must have the opportunity to answer questions in the grand jury before an indictment. (Trump declined the offer to testify.)

The Georgia 2020 election interference investigation (Fulton County District Attorney's Office)

The Georgia case centers on the actions of Trump and his allies in the weeks following the 2020 presidential election, as they pressured state officials to undo his loss in the state.

After Trump narrowly lost the state, he repeatedly called Georgia state officials to pressure them to find ways to change the outcome — including the infamous call to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger on Jan. 2, 2021, in which he instructed the Republican Raffensperger to "find 11,780 votes." Trump also called Gov. Brian Kemp and the state attorney general to urge them to contest the election results.

The inquiry has also examined efforts to send slates of fake electors to the Electoral College to say that Trump won, rather than Joe Biden.

The investigation is led by Fani Willis, the top prosecutor in Fulton County, Ga., where a special grand jury spent eight months hearing from more than 70 witnesses. Their work was finalized in early January. A portion of their report was released last month, but a judge ruled that most of it should remain confidential, for now.

Willis has said decisions on indictments are "imminent." It's not clear if Trump would be among those charged. Possible crimes for him or others could include soliciting election fraud, giving false statements to government bodies and racketeering.

A pair of investigations into Trump's actions around Jan. 6 and his mishandling of classified documents (the U.S. Department of Justice)

The U.S. Department of Justice has two ongoing investigations into possible criminal actions by Trump. Both probes are being led by Special Counsel Jack Smith, who was appointed by Attorney General Merrick Garland last year.

One of the investigations centers on how Trump handled classified documents after his presidency ended. Last June, a lawyer for Trump certified that a "diligent search" for classified documents had been conducted at his Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida and all documents found had been turned over to federal authorities. But two months later, an FBI raid recovered more than 100 additional documents.

(President Biden has been embroiled in his own classified documents scandal after files were found to be improperly stored at his Delaware home and a think tank office in Washington he previously used. A different special counsel has also been appointed to investigate that.)

Smith is also looking at Trump's attempt to interfere with the 2020 election. As part of that probe, prosecutors have interviewed numerous Trump allies and aides. They've also subpoenaed former Vice President Mike Pence, whom Trump pressured intensely to overturn the election results during the certification process on Jan. 6.

Prosecutors are also reportedly investigating the finances of Save America, a Trump-affiliated political action committee.

The DOJ investigations are ongoing. There's not much known about when charges, if any, would come. But as the 2024 election draws closer, any indictment is sure to draw accusations of political motivations.

READ MORE People worked their way through cars while participating in a public auction day at the Memphis Police Impound Lot. (photo: Brad J. Vest/The New York Times)

People worked their way through cars while participating in a public auction day at the Memphis Police Impound Lot. (photo: Brad J. Vest/The New York Times)

After a brief conversation in which she tried to lure him to a nearby motel, Mr. Jones said, he drove away but was soon stopped by the police and yanked from his truck. The 70-year-old welder said that with just 86 cents in his pocket, he had neither the intent nor the money to solicit a prostitute, as the officers were claiming.

His protests were to no avail. Mr. Jones was cited, and his truck, along with the expensive tools inside, was seized. The charges were eventually dropped, but the truck and his work equipment remained corralled in a city impound lot for six weeks, when prosecutors finally agreed to return it in exchange for a $750 payment.

“It’s nothing but a racket,” Mr. Jones said.

Police departments around the country have long used asset forfeiture laws to seize property believed to be associated with criminal activity, a tactic intended to deprive lawbreakers of ill-gotten gains, deter future crimes and, along the way, provide a lucrative revenue source for police departments.

But it became a favored law-enforcement tactic in Memphis, where the elite street crime unit involved in the death of Tyre Nichols on Jan. 7, known as the Scorpion unit, was among several law enforcement teams in the city making widespread use of vehicle seizures.

Like Mr. Jones, some of the people affected by the seizures had not been convicted of any crime, and defense lawyers said they disproportionately affected low-income residents, and people of color.

Over the past decade, civil rights advocates in several states have successfully pushed to make it harder for the police to seize property, but Tennessee continues to have some of the most aggressive seizure laws in the country.

While some states now require a criminal conviction before forfeiting property, Tennessee’s process can be much looser, requiring only that the government show, in a civil process, that the property was more likely than not to have been connected to certain types of criminal activity — a less rigorous burden of proof. Tennessee allows local law enforcement agencies to keep the bulk of the proceeds of the assets they seize.

And the process for getting property back in the state can be prohibitive for those who have little money or the ability to hire a lawyer: Those who fail to file a claim and post a $350 bond within 30 days automatically forfeit their property.

“Tennessee’s forfeiture laws are among the nation’s worst,” said Lisa Knepper, a senior director of strategic research at the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit law firm that has called for changes in state and federal forfeiture laws.

In Memphis, some of the more than 700 vehicles seized last year were taken from people who were ultimately found guilty of serious criminal charges. But other residents reported in interviews that they were compelled to pay large fees to recover their vehicles even when they had not been convicted of any crime.

In 2021, Memphis Police Chief Cerelyn Davis came forward with the city’s plan to combat growing incidents of reckless driving and drag racing with vehicle seizures,. This happened at around the same time that the city was launching the Scorpion unit — an acronym for the department’s Street Crimes Operation to Restore Peace in Our Neighborhoods.

No longer would police officers be merely issuing citations to reckless drivers who endangered others, she said, seeming to acknowledge that such seizures might not ultimately stand up in court.

“When we identify individuals that are reckless driving to a point where they put other lives in danger, we want to take your car, too,” she said. “Take the car. Even if the case gets dropped in court. We witnessed it. You did it. You might be inconvenienced for three days without your car. That’s enough.”

Mayor Jim Strickland was also a strong supporter of the seizure policy and even proposed destroying cars used by drag racers and other reckless drivers. “I don’t care if they serve a day in jail,” he said last year. “Let me get their cars, and then once a month we’ll line them all up, maybe at the old fairgrounds, Liberty Park, and just smash them.”

Police officers said it was on suspicion of reckless driving that they first pulled over Mr. Nichols, a 29-year-old Black man who died after a long and brutal beating by Scorpion officers. Five officers have been charged with murder in the case. Chief Davis subsequently said that she had seen nothing to support the reckless driving allegation. Nichols’s car was taken to the city’s impound lot.

The Scorpion unit was touted for its record of seizing drugs, cash and cars. In just the first few months of its operations, the city reported that the elite unit had seized some 270 vehicles.

Many of the vehicle seizures have revolved around drugs. In those instances, according to several defense lawyers, the agency often seized a vehicle based on a claim that it was being used in a drug-dealing operation — a common basis for such seizures in many cities, intended to deprive drug dealers of their profits and the ability to continue their work.

But even some of those not convicted of a crime said they spent weeks without a car while trying to navigate a complicated court process.

Filing a claim in court requires posting a $350 bond. Sometimes, defense lawyers said, the authorities managing the case may offer to release the car without requiring a court hearing if a person pays a fee that can amount to thousands of dollars.

Shawn Douglas Jr. lost his car in the fall after being stopped at a Memphis gas station by officers who reported finding two clear baggies containing marijuana inside a backpack.

Mr. Douglas was soon in handcuffs, arrested on suspicion of a felony drug infraction, an allegation he denied. His car was sent to impound.

In an interview, Mr. Douglas said one of the arresting officers commented to him about his 2015 Dodge Charger: “He said, ‘That would be a great police vehicle. When we take those vehicles we hope people don’t come get them back so we can do drug busts out of them.’”

Months later, Mr. Douglas’s criminal charges had been dropped, but his car was still in police custody. He was only able to recover it after paying $925, records show; crews towed it out to a dusty lot and handed it over to him, its battery dead. Mr. Douglas had to struggle with battery cables to get it started.

“It cost a lot of money,” Mr. Douglas said. “It puts you back on everything and creates more stress. When you can’t pay bills, you can’t do anything.”

Neither the police department nor the district attorney’s office responded to questions about the forfeiture cases of Mr. Douglas and others interviewed for this article, and they only briefly addressed the city’s forfeiture policy.

In Memphis, as in many cities, revenues from such impound and forfeiture fees are returned to support policing activities, becoming a regular source of revenue.

Memphis has not disclosed how much money it generated for the hundreds of vehicles that were forfeited. The city did report seizing some $1.7 million in cash last year, winning forfeiture of nearly $1.3 million.

This income is most often being generated from the city’s poorest residents, defense lawyers said.

“It’s unfair to a lot of the poorer citizens in Memphis,” said Arthur Horne, who has represented such clients. “It’s a huge tax.”

Vehicle seizures have never been a priority in the city’s overall crime-fighting strategy, Chief Davis said in a brief interview, adding that any money gained from forfeitures was not essential to police operations.

“We haven’t put a high level of priority on asset forfeiture here in Memphis,” she said. “We put more of a priority on violent crime, reducing violent crime.”

“It’s not like we’re out trying seize vehicles. We have a budget to support the police department.”

Erica R. Williams, the communications director for the Shelby County District Attorney’s Office, says that prosecutors do not receive any share in proceeds from vehicle forfeitures.

“We attempt to handle these cases as quickly as possible in an effort to minimize the difficulty caused by the seizure of a vehicle, while simultaneously seeking to accomplish the spirit of the statute,” she said, which was to “discourage engagement in future offenses.”

Seven states do not give forfeiture revenues to law enforcement. A few states, such as New Mexico, Maine and North Carolina, do not permit civil proceedings and allow forfeiture only after criminal convictions.

A bill pending in Congress proposes a series of new rules that would raise the standards for the government to win forfeiture, give access to lawyers for people trying to recover their property and end profit incentives by sending revenues to the Treasury Department’s general fund.

John Flynn, the president of the National District Attorneys Association, said efforts seeking to limit forfeitures have at times brought together lawmakers on the left and the libertarian right. But he said such efforts could go too far, undermining a law-enforcement tool that he said provides a deterrent to wrongdoers and turns over illegal criminal profits to those trying to fight crime.

“From a prosecutor’s standpoint, any money or vehicles or property gained through illegal conduct should be forfeited,” Mr. Flynn said.

He said safeguards allowed people to present evidence that their property was not acquired through illegal means.

In Memphis, at the city’s crowded impound lot north of town, cars towed in from around the city for various reasons mix with recovered stolen vehicles and cars seized by the police. Tow trucks buzz in regularly, and a fine coat of dust from a nearby limestone supply company settles over everything.

A dozen shoppers were on hand one recent morning looking at a GMC Denali that was up for auction. It looked to be in mint condition on the passenger side, but 20 or so bullet holes dotted the driver’s side door.

Further down the lot, Kyle Lyons was standing next to a pile of belongings that he had retrieved from his 2010 BMW, which had been seized in July by police officers who said they had found heroin in the vehicle. Mr. Lyons, who said he had struggled with addiction, was hoping to get back thousands of dollars worth of Craftsman tools that had been taken along with the car — equipment he needed to work.

Once his car was gone, he said, he had lost nearly everything else.

“Everything I use to make money with was gone,” Mr. Lyons said. “I couldn’t work, couldn’t go out and buy no more. I was homeless for four months.”

He has left Memphis and moved home to Kentucky. His car is still impounded.

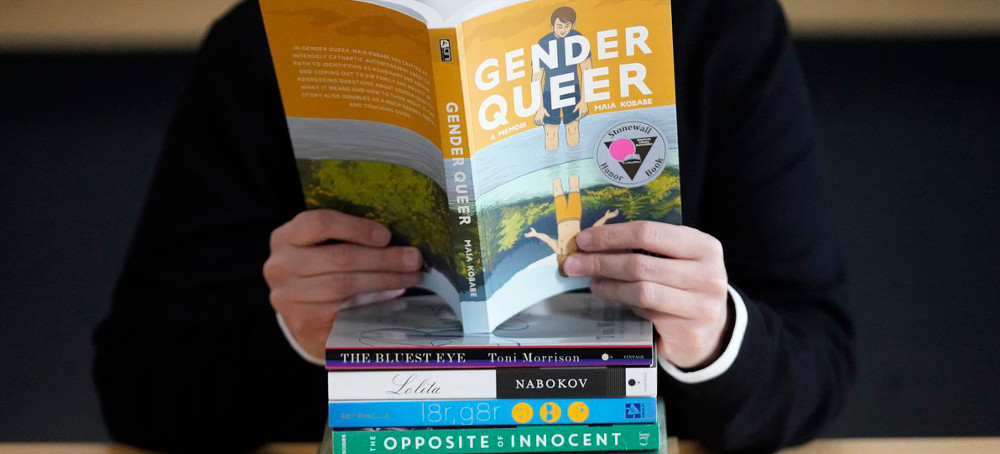

READ MORE The American Library Association has recorded more than 1,200 attempts to ban or restrict access to books across the U.S. last year. (photo: Rick Bowmer/AP)

The American Library Association has recorded more than 1,200 attempts to ban or restrict access to books across the U.S. last year. (photo: Rick Bowmer/AP)

Conservative groups are trying to restrict availability or ban books covering topics such as race and gender identity.

More than 1,200 challenges were compiled by the association last year, nearly double the then-record total from 2021 and by far the most since the ALA began keeping data 20 years ago.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, who directs the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. “The last two years have been exhausting, frightening, outrage inducing.”

Thursday’s report not only documents the growing number of challenges but also their changing nature. A few years ago, complaints usually arose from parents and other community members and referred to an individual book.

Now, the requests are often for multiple removals and are organised by national groups, such as the conservative Moms for Liberty, which has a mission of “unifying, educating and empowering parents to defend their parental rights at all levels of government”.

Last year, objections were filed against more than 2,500 books, compared with 1,858 in 2021 and 566 in 2019. In numerous cases, hundreds of books were challenged in a single complaint. The ALA bases its findings on media accounts and voluntary reporting from libraries and acknowledges that the numbers might be far higher.

Librarians around the country have reported being harassed and threatened with violence or legal action.

“Every day professional librarians sit down with parents to thoughtfully determine what reading material is best suited for their child’s needs,” ALA President Lessa Kanani’opua Pelayo-Lozada said in a statement.

“Now, many library workers face threats to their employment, their personal safety, and in some cases, threats of prosecution for providing books to youth they and their parents want to read,” she said.

Caldwell-Stone said some books have been targeted by liberals because of racist language, notably Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, but the vast majority of complaints come from conservatives, directed at works with LGBTQ or racial themes.

They include Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer, Jonathan Evison’s Lawn Boy, Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give and a book-length edition of the 1619 Project, the Pulitzer Prize-winning report from The New York Times on the legacy of slavery in the US.

Bills facilitating the restriction of books have been proposed or passed in Arizona, Iowa, Texas, Missouri and Oklahoma, among other states.

In Florida, where Governor Ron DeSantis has approved laws to review reading materials and limit classroom discussion of gender identity and race, books pulled indefinitely or temporarily include John Green’s Looking for Alaska, Colleen Hoover’s Hopeless, Margaret Atwood’s dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale and Grace Lin’s picture story Dim Sum for Everyone!

More recently, Florida’s Martin County School District removed dozens of books from its middle schools and high schools, including numerous works by novelist Jodi Picoult, Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Beloved and James Patterson’s Maximum Ride thrillers, a decision that the bestselling author has criticised on Twitter as “arbitrary and borderline absurd”.

DeSantis has called reports of mass bannings a “hoax”, saying in a statement released this month that the allegations reveal “some are attempting to use our schools for indoctrination”.

Some books do come back. Officials at Florida’s Duval County Public Schools were widely criticised after they removed Roberto Clemente: The Pride of the Pittsburgh Pirates, a children’s biography of the late Puerto Rican baseball star.

In February, they announced the book would again be on shelves, explaining that they needed to review it and make sure it didn’t violate any state laws.

READ MORE  Apache Stronghold, a Native American group, protests outside a court in Pasadena, California, to protect their sacred land from a copper mine in Arizona, March 21, 2023. (photo: Mike Blake/Reuters)

Apache Stronghold, a Native American group, protests outside a court in Pasadena, California, to protect their sacred land from a copper mine in Arizona, March 21, 2023. (photo: Mike Blake/Reuters)

In court, the feds said Oak Flat would be in the hands of mining giants Rio Tinto and BHP by early summer.

In oral arguments Tuesday, the U.S. Forest Service said it was nearing completion of an environmental impact study that will transfer land east of Phoenix, to two of the world’s largest mining companies for the purpose of building of one of the largest copper mines on the planet. The massive project will hinge on the destruction of Chi’chil Biłdagoteel, a mountain otherwise known as Oak Flat, that is sacred to many Native American tribes, particularly the San Carlos Apache, who consider the area among their most holy of sites.

In a nearly two-hour hearing, an 11-judge panel on the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Pasadena, California, peppered lawyers on both sides of the high-stakes legal fight with an array of complex case law questions raised by the project. Begun nearly two decades ago, the battle for Oak Flat sits at the intersection of Indigenous rights and dispossession, religious liberty, public lands and private sales, and a growing demand for so-called green energy solutions in an era of climate catastrophe.

“As the court is aware, this case is not about an agency action. It’s about an act of Congress, in which Congress considered demands on a piece of property, balanced those interests, and made a decision,” said Joan Pepin, an attorney for the Forest Service, the agency that exchanged the land in a controversial deal nearly a decade ago. “It decided that Oak Flat should be transferred to Resolution Copper so the third-largest copper ore deposit in the world can be mined.”

The legislation in question — the Southeast Arizona Land Exchange and Conservation Act — was the product of a proposal then-Arizona Sens. John McCain and Jeff Flake added to a must-pass defense authorization bill late one night in 2014. The addendum, known as a rider, incurred no congressional debate. Described by the San Carlos Apache as a “midnight backroom deal,” the law transferred Oak Flat to Resolution Copper, a British-Australian concern jointly owned by the extractive giants Rio Tinto and BHP, both of which had sought access to the wildly lucrative ore deposit for years.

The project centers on a mountain on the 2,200-acre area known as Oak Flat Campground, part of the Tonto National Forest, that has served as a centerpiece of Apache religious ceremony and cosmology since before settler expansion into the West. To access the ore underneath, Resolution Copper will use a technique known as block cave mining, which over several years will turn the sacred mountain into a two-mile-wide crater deep enough to hide a skyscraper.

Initiation of construction hinges on the publication of an environmental impact study from the Forest Service, which, under the law passed in 2014, starts a 60-day countdown before the transfer of the land from the federal government to the mining company must happen.

Luke Goodrich, the lead attorney for Apache Stronghold, an Arizona-based nonprofit that brought the lawsuit to stop the transfer, told the panel of judges that the destruction of Oak Flat was a direct and flagrant violation of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Violation of the statute requires the imposition of a “substantial burden” on a person or group’s ability to practice their faith.

“A fine is a substantial burden, but here the government is doing something far worse,” Goodrich said, “not just threatening fines, but authorizing the complete physical destruction of Oak Flat, barring the Apaches from ever accessing it again and ending their core religious exercises forever.”

In January 2021, five days before leaving office, the administration of President Donald Trump released a study supporting the creation of the Oak Flat mine. Apache Stronghold filed a federal lawsuit seeking a preliminary injunction to stop the project the following month.

Unsuccessful in the attempt, the group then filed an emergency appeal to the 9th Circuit. Six hours before its deadline to respond passed, the Forest Service — by then, in March 2021, under the leadership of President Joe Biden — announced that it was withdrawing the environmental impact study and postponing the land transfer.

A three-judge panel of 9th Circuit dismissed Apache Stronghold’s case in October 2021 but agreed to hear the case again before a full panel last winter. The unusual decision set the stage for Tuesday’s hearing.

While the postponement of the project had given opponents of the mine a moment of respite in the long-running battle, the government’s testimony this week confirmed that the Biden administration is moving forward with a new environmental impact study and stands behind the controversial land swap.

“We said spring,” Pepin told the panel of judges Tuesday. “It could be shading over into early summer by the time that 60-day notice is given, but it is coming out in the near future, so I do believe this case is justiciable.”

While Apache Stronghold’s religious freedom argument has drawn support from an array of faith-based organizations across the country, proponents of the mine argue that the project would bring in 3,700 jobs and add $1 billion each year to Arizona’s economy.

David Debold, an attorney representing extractive industry associations, told the court that a win for the plaintiffs in the case “would erect huge and insurmountable obstacles” to the sale of government land to private entities. “The damage to private enterprise would be profound if the purchaser of federal property could only use that property later as though it were the federal government,” Debold said. “That is the rule that is being argued for here, although not in so many words.”

The judges took the arguments into consideration. The panel has offered no indication when it will rule on the case. Should the judges again rule in favor of the mining companies and the federal government, the plaintiffs are likely to take the case to the Supreme Court.

Following the hearing, defenders of Oak Flat gathered in the rain to debrief and pray. Goodrich, the Apache Stronghold attorney, said there was no disputing the core facts of the case. “This is not a theoretical matter,” he said. “This is a people matter. This is about the people and their freedom: freedom to be Apache, to be Indigenous, to be Americans.”

After the day’s testimony, there was no longer any question where the Biden administration stood. “The government didn’t hold back today,” Goodrich said. “It said it for everyone to hear — everyone in the courtroom to hear, everyone in Indian Country to hear, and everyone in the whole country to hear. The government thinks it has blanket authority to do whatever it wants with the land that it’s taken from Indigenous peoples, even destroying central sacred sites and ending religious exercises forever.”

Wendsler Nosie Sr., former chair and councilmember of the San Carlos Apache and a veteran activist who has spent much of his life fighting the Oak Flat mine, joined in addressing the tribe’s supporters. “This country is a corporate country. It’s not even thinking about our children, the Earth, the things that give us life,” Nosie said. “The corporate world is waiting for this case to finish because they are in line for their exemptions. And if this happens, how we gonna stop that?”

Nosie’s remarks were followed by comments from his granddaughter, Naelyn Pike. Like her grandfather, Pike has devoted her life to stopping the mine. Among its many sacred attributes, the mountain at Oak Flat is used for coming-of-age ceremonies for young Apache women. Having been one of those young women herself, Pike worried that the space would no longer exist for the generations that come after her.

“This land is sacred. This land is holy. It may not have four walls or a steeple. It may not be a mosque, but this is my religion and my spiritual belief from my ancestors and to the yet to be born,” she said. “We have to fight for those who are not here so that they can go to Oak Flat, and they can pray and be one — because the United States government assured us today that their land is their land and that they can take it away, that they can say what I believe in, and what you believe in, does not matter.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.