Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

In recognition of that fact, the march has a new route. It will finish somewhere on First Street, between the Capitol and the Court building, an acknowledgment of the enormous and somewhat nebulous task ahead: banning or restricting abortion in all 50 states. That task will involve not only Congress, the courts, and the president but also 50 individual state legislatures, thousands of lawmakers, and all of the American communities they represent.

It’s as though Captain Ahab suddenly harpooned Moby Dick and had to figure out his next step in life.

Dobbs triggered much celebration and self-congratulation among anti-abortion activists: Their decades-long strategy of undermining Roe via Supreme Court appointments by Republican presidents had finally borne fruit. But this development was obviously just a condition precedent to the movement’s ultimate goal of banning abortion entirely and everywhere. It raised a lot of new and difficult questions about where to move next and how quickly to do so while fundamentally changing the dynamics of the abortion debate.

Since the central legal battle has now been resolved, the most urgent task for anti-abortion activists is to rethink their alliance with the Republican politicians they rely on for further progress in ending reproductive rights. Yes, there have always been considerable differences of opinion within the anti-abortion ranks over strategy, tactics, and rhetoric. But intra-movement arguments that were largely theoretical when Roe was in place are suddenly very real, and their resolution must be coordinated with GOP elected officials, candidates, and opinion leaders. There is no question that while Dobbs led quickly to abortion bans wherever they were possible, it also produced a sea change in public opinion that has to be troubling to those for whom reversing Roe was just the starting point.

The Guttmacher Institute reports that, post-Dobbs, 24 states have enacted some sort of previously unconstitutional abortion ban. But at the same time, the abortion-rights side won every 2022 ballot test on abortion policy including three in the deep-red states of Kansas, Kentucky, and Montana and another in the key battleground state of Michigan. Perhaps of equal significance, candidates from a Republican Party that had maintained a steady partnership with the anti-abortion movement since at least 1980 ran away from the issue as quickly as it could in most competitive election contests. At the federal level, Republicans hid behind the ancient and entirely insincere pre-Dobbs claim that they wanted only to return the issue to the states. (If you think of fetuses as “babies” with an inalienable “right to life,” then that’s a contemptuous dodge; today, as in the antebellum era, “states’ rights” is just a veil for more absolute policy goals, whether it’s slavery or forced birth.) And in states where voters were allowed to weigh in, Republicans sometimes shrugged and deferred to the abortion-rights majority of public opinion.

So the challenge before anti-abortion activists isn’t just to reach internal consensus over short- and long-term goals and tactics; they also need to reimpose discipline on the GOP and its shifty politicians. Fortunately for these activists, they will have a lever via their influence on what looks to be a highly competitive 2024 GOP presidential nominating contest. Republican presidential candidates will find that support for a federal abortion ban is an absolute condition for the movement’s support. At the same time, Republicans at the state and local levels will be pressed to work toward the most extreme abortion policies that are politically viable wherever they run or hold office. If Republicans candidates stick with their impulse to avoid this sensitive issue, it could be deadly for the future of the “right to life” movement.

For all the post-Dobbs excitement over “babies being saved,” the anti-abortion movement needs to quickly make ground on public opinion or increase its control of GOP candidates. If it fails to do so, it could see the reemergence of pro-choice Republican candidates and elected officials, a nearly extinct species until now but one that could command some significant grassroots support within the party along with crossover appeal. If that happens, the nation’s abortion-rights majority will impose its will sooner or later, and reproductive rights may gain recognition nearly everywhere in law, if not in the Constitution.

READ MORE  Gov. Gavin Newsom at a news conference at The Unity Council on Monday in Oakland, California. (photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty)

Gov. Gavin Newsom at a news conference at The Unity Council on Monday in Oakland, California. (photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty)

Newsom’s state is reeling from 3 mass shootings in just 8 days.

California’s latest mass shooting happened on Monday afternoon, when seven people were shot dead by a 62-year-old man at two mushroom farms in Half Moon Bay, 30 miles south of San Francisco.

Newsom’s comments, in which he called for the banning of high capacity magazines, came hours after a 72-year-old gunman wielding a customized rifle with a high capacity magazine killed 11 people in a dance studio in Monterey Park. Days earlier, on Jan. 16, a teenage mother and her baby were among six people killed in a shooting at a home in California’s Central Valley.

Newsom tweeted on Monday that he was in the hospital visiting victims of the Monterey Park shooting when he was told about the Half Moon Bay incident.

“At the hospital meeting with victims of a mass shooting when I get pulled away to be briefed about another shooting. This time in Half Moon Bay,” Newsom tweeted. “Tragedy upon tragedy.”

Speaking to CBS on Monday, in an interview broadcast after the Half Moon Bay shooting took place, Newsom addressed the spate of mass shootings in the U.S. in the first month of 2023 and lamented that nothing is being done to advance gun control laws.

“Nothing about this is surprising. Everything about this is infuriating,” he said. “The Second Amendment is becoming a suicide pact.”

Large capacity magazines do not belong on our streets. pic.twitter.com/kvYXFQBOQs

— Gavin Newsom (@GavinNewsom) January 24, 2023

When CBS’ host Norah O’Donnell pushed back, saying there were a lot of legal gun owners in the U.S., Newsom responded: “I have no ideological opposition to someone who is reasonably and responsibly owning firearms and getting background checks and being trained.”

Earlier in the day, Newsom attacked TV networks that “sell fear” about crime and immigration, singling out Fox News for the station’s typical response to mass shootings.

“Fox is a disgrace what they say, what these people say every single night,” Newsom said. “There’s xenophobia, they’re racial priming, what they have done to perpetuate crime and violence in this country, by scapegoating, and by doing not a damn thing about gun safety, not a damn thing for decades.”

Newsom then outlined how the network’s hosts have spent more than a decade normalizing mass killings by resisting calls for stricter gun control laws.

“It’s ‘not the right time, not the right time, not the right time.' Rinse, repeat. Not the right time, Sandy Hook, not the right time, rinse, repeat. Uvalde. Remember Uvalde? Remember? Rinse, repeat. You don’t remember the Borderline here, 13 people, look that one up. Rinse, repeat. Not a damn thing they do. And we know it. And we allow them to get away with that.”

READ MORE  Legal scholars and voting rights advocates remain on alert for a court ruling by this summer on what's known as the 'independent state legislature theory.' (photo: Mariam Zuhaib/AP)

Legal scholars and voting rights advocates remain on alert for a court ruling by this summer on what's known as the 'independent state legislature theory.' (photo: Mariam Zuhaib/AP)

Still, many legal scholars and voting rights advocates remain on alert for a court ruling by this summer on what's known as the "independent state legislature theory." It claims that under the U.S. Constitution, state legislatures have the power to determine how federal elections are run, without any checks or balances from state constitutions or state courts.

While the court may end up issuing a narrow ruling that broadly rejects this widely disputed idea, a court endorsement of the theory is still possible. And the court's adoption of even a limited version of it could usher in a wave of instability to the country's already beleaguered election system, including during next year's presidential race.

Here's what could happen if a majority of the justices endorse some version of this controversial theory:

It could lead to more lawsuits and bring uncertainty to upcoming elections

The case in which the theory has come up, Moore v. Harper, boils down to this: Who should have the last word on the redrawing of congressional voting districts in North Carolina — the state's legislature or its state Supreme Court, which struck down a legislature-approved map for violating the state's constitution?

On its face, the potential impact of how the U.S. Supreme Court answers that question may seem narrow.

But a ruling that sides with the Republican North Carolina state lawmakers who appealed the case would be a radical departure for the country's highest court, which has long deferred to state courts on how state constitutions should be interpreted.

And if a majority of the justices decide not to shut the theory out completely and instead adopt a less robust version, they could open the door to more U.S. Supreme Court appeals of other state court decisions about federal elections.

Every election cycle, the U.S. Supreme Court and lower federal courts could be "flooded with requests to second-guess state court decisions interpreting and applying state elections laws," warned a rare legal brief from the Conference of Chief Justices, which represents the top judges in every state.

"We're living in a moment in which these election rules really do matter with respect to turnout and control of Congress. And many state legislators are willing to do whatever it is that they can in order to further the power of their political party or of their political supporters," says Guy-Uriel Charles, an election law professor at Harvard Law School. "Whatever rules the court might set, it can expect that in many states and in many state legislatures, the boundaries are going to be pushed."

And as legal challenges push their way toward the U.S. Supreme Court, questions about whether various aspects of federal elections are legal could be left hanging in the air, adding uncertainty and making it harder for local officials to carry out ongoing elections.

An alternative solution to the case, which was discussed during December's oral arguments, could also lead to a legal mess, many court watchers warn. A number of the justices' questions were devoted to how the U.S. Supreme Court could set a standard for when it would step in to review a state court's decision about congressional elections that involves that state's constitution.

How much of a mess could be created would depend in large part on how high and clear that kind of a standard would be.

"There will be different views on when a state court has gone too far. And that is essentially the big problem with the middle-of-the road approach. It doesn't really resolve anything," says Stuart Naifeh, an attorney who manages the redistricting project at the Legal Defense Fund, which filed a friend-of-the-court brief opposing the theory.

It could make it easier for state lawmakers to ignore voting rights protected under state law

State constitutions enshrine many voting protections, such as the right to cast a secret ballot and guarantees of absentee or mail-in voting.

But some of those protections could go away in elections for Congress and for president if the U.S. Supreme Court rules that state constitutions cannot restrict state legislatures in deciding how federal elections are run, says David O'Brien, policy director for RepresentUs, an anti-corruption group that advocates for voting rights and that joined a legal brief against the independent state legislature theory.

"If we're looking at a world where those state constitutional guarantees are no longer a constraint on legislatures, then legislatures could start getting rid of things like that that we've just taken for granted for generations," adds O'Brien, who co-wrote a report on state election laws that could be affected by a Moore v. Harper ruling that adopts the theory.

While state lawmakers pushed to change election rules, whether existing state constitutional provisions should be enforced could be thrown into question.

And any state-level efforts to change the federal election process through a ballot initiative passed by a state's voters could also face more uncertainty. Reforms passed by ballot measures, such as the one that created Alaska's ranked-choice voting system for general elections, are often challenged in court.

"There's almost always litigation around the constitutionality of [these kinds of reforms]," says Anh-Linh Kearney, a research analyst at RepresentUs who co-authored the report with O'Brien. "It's pretty frequent that state supreme courts will weigh in on this."

And then the U.S. Supreme Court could be called to weigh in on a ballot initiative if the high court adopts some version of the theory.

The potential unraveling of state election law could also affect earlier state court decisions that have set how state constitutional provisions should be interpreted, including those that ban redrawing voting districts in a way that gives an unfair advantage to one political party over another, says Ethan Herenstein, an attorney at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, who helped file a friend-of-the-court brief against the theory and co-wrote a report on the election rules that it puts in danger.

"State courts are the only courts that are open to claims of partisan gerrymandering," explains Herenstein, in light of a 2019 U.S. Supreme Court decision. "If federal courts can't get involved to stop partisan gerrymandering and the ability of state courts to do so is constrained by a bad ruling in Moore v. Harper, that'll put the fight to end partisan gerrymandering on a slippery slope."

Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court's adoption of some form of the theory could pose a "real threat" to the "sovereignty and autonomy" of states and their constitutions at a great cost to voters, according to Kate Shaw, a law professor at the Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University in New York and co-host of Strict Scrutiny, a podcast about the Supreme Court.

"It's not that state constitutions are perfect by any stretch, but they do enshrine these democracy-related principles in a far more explicit way than the federal constitution does," Shaw says.

It could spark a legal challenge over recent reforms to the Electoral Count Act

Last month, in an attempt to avoid repeating the turmoil of the 2020 presidential election, which culminated in the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, Congress tried to clarify the process for counting Electoral College votes.

The reforms to the Electoral Count Act of 1887 specify that states must pick electors "in accordance with the laws of the State enacted prior to election day."

Richard Pildes, a professor of constitutional law at New York University School of Law, who advised the U.S. House and Senate on the reforms, says the changes were intended to underline that the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power to control when electors have to be chosen. According to federal law, that deadline is Election Day, the last day of voting.

"When Congress says, as it has since the mid-19th century, that the electors must be chosen by the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November, that means state legislatures cannot just ignore [the popular vote] after the fact and decide they want to appoint a slate of electors," Pildes says.

Still, some other legal scholars are concerned that a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Moore v. Harper that adopts some version of the independent state legislature theory could spur a legal challenge next year to the Electoral Count Reform Act's requirement that state laws about how electors are chosen for the 2024 presidential election must be enacted before Election Day.

"It seems like it would place a lot of doubt over Congress' power to supervise certain aspects of the state's conduct of the elections," says Jack Beermann, a professor at Boston University School of Law who has written about the process for counting electoral votes.

A potential challenge by a state's lawmakers could try to apply the theory's understanding of a state legislature's special "independent" legal status to the Constitution's Electors Clause, which says:

"Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress."

One scenario after Election Day 2024, Beermann suggests, could involve state lawmakers deciding that instead of allocating all their state's electoral votes to the state-level winner of the popular vote, the electoral votes would be split up in some other way, such as the "congressional district method" used by Maine and Nebraska.

"They could readjust the rules in order to get their preferred candidate," Beermann says, adding that a state legislature may try to argue in court that its move "would be binding, because Congress has no business telling them when they have to pass those laws" because of the independent state legislature theory.

But J. Michael Luttig — a retired federal judge who consulted with the U.S. House and Senate on the Electoral Count Reform Act and who is serving as an attorney for one of the groups challenging the theory in Moore v. Harper — points out that this kind of move would likely run up against due process protections under the Constitution's 14th Amendment.

Luttig adds that he urged Congress to underscore its power to prevent states from changing laws about the electoral count process after Election Day by including in the Electoral Count Reform Act a reference to the Constitution's Necessary and Proper Clause, which gives Congress the authority to "make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper" for carrying out its powers. A bill passed by the House in September 2022 included a mention of the clause.

"Once they added that recitation of the necessary and proper powers that reside in the Congress, then I do not believe that there's an argument around the Electoral Count Reform Act now by virtue of the independent state legislature theory, even if the Supreme Court were to adopt the most aggressive version of that theory," Luttig says.

No reference to the clause, however, ended up in the act. But Luttig adds that courts could still rely on that part of the Constitution to uphold the law.

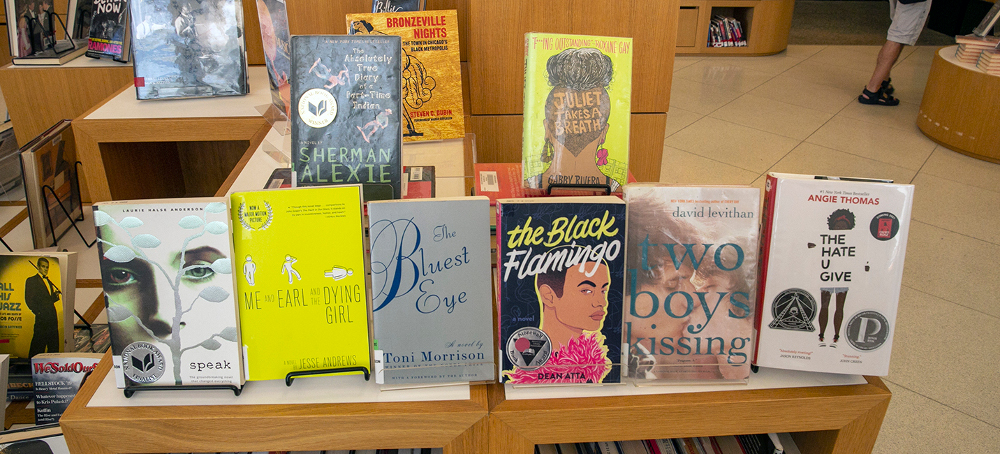

READ MORE  Florida's new bill goes into effect prohibiting material unless deemed appropriate by a librarian or 'certified media specialist.' (photo: Ted Shaffrey/AP)

Florida's new bill goes into effect prohibiting material unless deemed appropriate by a librarian or 'certified media specialist.' (photo: Ted Shaffrey/AP)

State’s new bill goes into effect prohibiting material unless deemed appropriate by a librarian or ‘certified media specialist’

If a teacher is found in violation of these guidelines, they could face felony charges.

The new guidelines for the Florida law, known as HB 1467, outline the books be free of pornographic material, suited to student needs and their ability to comprehend the material, and appropriate for the grade level and age group.

In order to determine if the books meet these guidelines, certified media specialists must undergo an online training developed by Florida’s department of education.

With only a few or even one media specialist present in each school, the process to vet books is lengthy.

Scrutiny of teaching material in Florida schools heightened under the leadership of the rightwing Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, whose administration says it is actively working to “protect parental rights”, which includes a prohibition on childhood education on gender, sexual orientation and critical race theory.

DeSantis has emerged as a legitimate rival to Donald Trump in the Republican party. The former US president has already declared his 2024 candidacy for another White House run, while DeSantis is widely expected to do so later this year.

As part of his appeal to the party’s rightwing base DeSantis has sought to portray himself as a culture war warrior, cracking down on LGBTQ rights and taking conservative stances on the fight against Covid-19 and a host of other issues such as immigration.

In 2021, he announced the Stop Woke (Wrongs to Our Kids and Employees) Act to “give businesses, employees, children and families tools to fight back against woke indoctrination”.

Teachers have condemned the new guidelines.

The Manatee Education Association union president, Pat Barber, told local TV station Fox 13: “We have people who have spent their entire careers building their classroom libraries based on their professional and educational experience and understanding of the age of the children they teach.”

Barber added: “Now, their professional judgment and training are being substituted for the opinion of anyone who wishes to review and challenge the books. We’re focused on things that cause teachers to want to walk away from education because they can’t focus on their mission of educating children.”

Some teachers are even covering up their library books with paper.

Don Falls, a history teacher at Manatee high school, told the Herald-Tribune newspaper: “If you have a lot of books like I do, probably several hundred, it is not practical to run all of them through [the vetting process] so we have to cover them up.”

More school districts in Florida are expected to follow suit as a result of such policies this year. The state’s education department issued a deadline of 1 July 2023 for when “the superintendent of schools in each district must certify to the FDOE Commissioner that all school librarians and media specialists have completed this training”.

READ MORE Construction workers in San Francisco, California. (photo: Paul Chinn/Getty)

The Federal Trade Commission has proposed banning “noncompete clauses” in labor contracts. It’s a win for workers, but the FTC’s rationale — a blind devotion to “competition” as the solution to injustices in the labor market — is wrongheaded and dangerous.

Earlier this month, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) proposed a new rule that would ban noncompete clauses in labor contracts. The rule, which is part of the agency’s effort to enforce the federal ban on unfair methods of competition, has received ample coverage and support in the mainstream press. Yet it also raises a host of questions about the relationship between labor law, antitrust, and notions of competition.

In the following text, which first appeared on the website of the Law and Political Economy Project at Yale Law School, Columbia University economist Suresh Naidu reflects on the problematic yet widespread assumption that monopoly (or monopsony) power is the fundamental driver of inequality in the labor market and that “more competition” is the solution.

But behind the no-noncompete consensus lies an unsettling division. The rule comes as a blanket ban from the FTC, under the aegis of increasing competition. In a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed, Chair Lina Khan reiterated that antitrust law stipulated preserving competition, regardless of what other sources of countervailing power exist (e.g., union neutrality).

Competition itself should not be the primary desiderata for the labor market. For one thing, employers have considerable power even in decentralized, competitive markets, so the scalpel of antitrust is poorly suited, compared to either labor law or macroeconomic policy, to tackle the bulk of the monopsony power in the labor market. Regulators can police the behavior of large employers with bureaucratic modes of worker control, but have a harder time neutralizing the diffuse workplace despotism of many small businesses.

Second, competition is often the source of many labor market harms (including, historically, racial conflict), and can easily destroy existing norms of fairness and networks of solidarity, as was recognized by the Clayton act. Other sources of countervailing power can be broken by an activist antitrust regime exclusively focused on competition as the preeminent property of functioning markets.

Finally, by relying too much on competition, we forgo other, deeper and more democratic, principles that could undergird an expansive notion of economic non-domination. Ironically, owing to our history of coerced labor, American law has deep resources for fighting unfree labor contracts. One of the earliest uses of the 13th Amendment came with the 1867 anti-peonage statute, which outlawed the widespread indentured servitude in the newly added New Mexico territory. We could have gone after noncompetes under the banner of “no contractual surrender of liberty,” encompassing binding arbitration, nondisclosure, no-strike clauses, and yellow-dog contracts as well as noncompetes, rather than the narrower mandate of “more competition.” Although labor rights generally have been won as forms of economic regulation, rather than as entrenched freedoms, there’s no reason to concede to that. And in the context of wider interest in rethinking the Constitution and ideas of economic freedom, it might be time to bring those ideas back to the fore as a way of thinking about the labor market generally.

READ MORE  Indigenous people of Brazil protest about the murders of British journalist Dom Phillips (pictured left) and his guide, Bruno Pereira. (photo: Cris Faga/Shutterstock)

Indigenous people of Brazil protest about the murders of British journalist Dom Phillips (pictured left) and his guide, Bruno Pereira. (photo: Cris Faga/Shutterstock)

Police chief says Rubens Villar Coelho, whose nickname is Colômbia, ordered the murders of the British journalist and Brazilian Indigenous expert

Rubens Villar Coelho, whose nickname is Colômbia, was first arrested on separate charges last July – one month after the two men were murdered in the Javari valley region of the Amazon. He was released in October but was rearrested last month for breaking his bail terms.

On Monday afternoon, the federal police chief for Amazonas state, where the Javari valley is located, told reporters that investigators had concluded Villar Coelho – who has been accused of running an illegal fishing racket in the remote border region – had ordered the murders.

“I have no doubt that Colômbia was the mastermind,” Alexandre Fontes said at a press conference in the state capital, Manaus, according to the Brazilian news website G1.

Three other men are currently in custody for the murders and stand accused of shooting Phillips and Pereira as they travelled down the Itaquaí River on the morning of 5 June 2022. They are Amarildo da Costa Oliveira, Jefferson da Silva Lima and Oseney da Costa de Oliveira.

Fontes said investigators had gathered evidence that Villar Coelho provided the first two of those men with the ammunition that was used to commit the murder.

Fontes claimed the 16-gauge shotgun used in the crime had been provided by Amarildo da Costa Oliveira’s brother, Edvaldo da Costa Oliveira, “in the knowledge that it would be used to murder Bruno and Dom”.

Villar Coelho had also paid for Amarildo da Costa Oliveira’s initial defense lawyer, Fontes added.

Villar Coelho denied involvement in the crime after being detained last July.

Phillips, 57, a longtime Guardian contributor and foreign correspondent, travelled to the Javari valley with Pereira as part of research for a book he was writing called How to Save the Amazon.

At the time of the murders, 41-year-old Pereira, a revered Indigenous specialist and explorer, had been helping Indigenous communities in the Javari valley set up monitoring teams to defend their rainforest homes from illegal mining, poaching and fishing gangs with links to organized crime.

The murders sparked international outrage and exposed the damage done to Brazil’s environment and Indigenous communities during the far-right government of Jair Bolsonaro, who lost last October’s election and is currently in the US.

On Sunday, Bolsonaro’s successor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, accused the rightwing populist of committing genocide against the Yanomami people of the Amazon by dismantling Indigenous protections and encouraging the illegal gold miners who have invaded that and other Indigenous territories.

Speaking to the Guardian recently in Brasília, Beto Marubo, a Javari leader who was close to Pereira, said Indigenous activists had seen no sign of the security situation improving in the region despite the outcry over the murders.

Marubo voiced hope that the men’s killers would be brought to justice under Brazil’s new government.

“We hope – and we will continue to demand from the new government and authorities – that there is justice for Dom and Bruno ,” he said.

Relief that police had formally accused Villar Coelho, a notorious and feared figure in the region where Phillips and Pereira were killed, was tempered with ongoing suspicions that their murders were part of a bigger conspiracy in a region awash with environmental crime and drug trafficking, reportedly involving cartels from Colombia and Mexico.

The Javari valley, which is home to the world’s largest concentration of isolated Indigenous tribes, has become a major highway for cocaine and marijuana smuggling in recent years, with huge shipments of drugs being moved by river from Peru into Brazil and then on to Europe.

Eliesio Marubo, a representative of Univaja, the Indigenous NGO for which Pereira had worked, said the federal police conclusions had confirmed the murdered activist’s suspicions that Villar Coelho was involved in the fishing gangs that preyed on the supposedly protected Javari valley Indigenous territory. But Marubo said many questions remained.

“Who is bankrolling these people so they are able to continue their criminal activities? Why is it that so many politicians in the region helped these criminals? Why is this criminal organization still operating in the region?” he asked, pointing to a November attack on another of the Javari’s Indigenous leaders.

Marubo said Javari activists wanted a “far-reaching investigation” which “truly showed who killed Dom and Bruno”.

READ MORE  Scientists say climate change is forcing the polar bears to spend more time inland than in the past. (photo: Ulf Mauder/Getty)

Scientists say climate change is forcing the polar bears to spend more time inland than in the past. (photo: Ulf Mauder/Getty)

Polar bear attacks are exceedingly rare. Between 1870 and 2014, there were only 73 documented attacks by wild polar bears across Canada, Greenland, Norway, Russia, and the United States, resulting in 20 human deaths, according to a 2017 study. Still, the recent mauling has raised questions about whether the impact of global warming heightens the risk of attacks by polar bears, which are powerful predators.

No individual attack can be attributed to climate change, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says it is still investigating the circumstances of the Alaska attack.

But rising temperatures are melting the sea ice that polar bears navigate to find mates, raise cubs and hunt seals to sustain their high-fat diet. The shrinking ice has put the population of polar bears at risk of decline.

Scientists say climate change is forcing the Arctic carnivore to spend more time inland than in the past — raising the possibility of run-ins that could be dangerous both for humans and bears.

Before last week, the last deadly bear attack in Alaska was in 1990, according to Geoff York, a senior director of conservation at the environmental group Polar Bears International, who co-wrote the 2017 paper. The bear at the time, like others that may attack, showed signs of starvation.

“Animals in poor body condition are just more likely to take risks. They’re more likely to be desperate and to do things that a healthy bear typically wouldn’t do. And those are the bears specifically that people have to be worried about,” York told The Washington Post.

Federal wildlife managers say the loss of ice is “the primary threat to polar bears,” which are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

“Human-polar bear interactions are expected to increase as polar bears spend more time on shore in more places,” York said.

Researchers have reported seeing an “increased presence” of polar bears on land and in coastal areas, from Alaska, to Baffin Bay near Greenland, to Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean north of mainland Europe.

And some communities in proximity to the large creatures have tried to reduce the risks of human-bear encounters, including polar bear patrols in Russia and Canada, for instance.

Earth is now losing 1.2 trillion tons of ice each year.

Jon Aars, who has led the Norwegian Polar Institute’s polar bear program since 2003, notes that Svalbard has “strict rules for how you behave when you’re out,” teaching residents warning systems and requiring they carry weapons if in the field.

The conditions and hunger of polar bear populations varies, according to Aars, who said the bears in Svalbard were “still in quite good shape.” While it’s more dangerous to meet a hungrier or younger bear, they could attack even if well-fed, he added.

The bears, meanwhile, “do the best out of the situation, they look for alternatives when there’s no ice,” Aars said. But, he added: “I think it’s not very likely that they will be able to survive in areas where you have no sea ice at all.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.