Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Despite the billionaire touting that he wasn’t banning @ElonJet, Twitter has suspended it — as well as the personal account of its creator

ALSO SEE: Twitter Suspends Over 25 Accounts That Track

Billionaires' Private Planes

On Wednesday, @ElonJet was permanently suspended from Twitter, despite Musk previously writing that he would leave the account up to demonstrate his commitment to free speech. Later on Wednesday, Sweeney himself was suspended, and revealed to The New York Times that around 30 of his accounts that tracked flight information — ranging from celebrities to NASA — were also banned. Sweeney said he was told that his accounts had violated rules against platform manipulation and spam.

By Wednesday evening, Musk revealed a very different reason for removing Sweeney from the platform. He characterized the tracking of aircraft as a form of “doxxing” and stated that Twitter’s content moderation policies would remove “any account doxxing real-time location info.” Exceptions would be made if the location information was posted on a delay, he said.

While Musk has yet to produce any evidence linking Sweeney to threats against his family, he tweeted that a car carrying his son, X Æ A-12, had been “followed by [a] crazy stalker” in Los Angeles. “Legal action is being taken against Sweeney … organizations who supported harm to my family,” Musk posted before sharing a video of what appeared to be the alleged stalker’s license plate, and asking for help from followers in tracking down the individual.

The suspensions and frantic revisions to Twitter’s terms of service come days after Sweeney posted, from his personal account, a screenshot of an internal Twitter message provided to him by an anonymous employee who informed him that as of Dec. 2, @ElonJet had had its “visibility limited/restricted to a severe degree internally.” The internal message, from newly minted head of trust and safety Ella Irwin, read: “Team please apply heavy VF to @elonjet immediately,” VF meaning “visibility filter.”

Sweeney wrote to followers that the account was “search banned” and that it had been having visibility issues “for months now way before [Elon’s] takeover.” The shadowban was reportedly lifted a day before the account was booted from Twitter.

The screenshot of Irwin’s Slack message message is no longer visible following Sweeney’s suspension on Tuesday, which came hours after he tweeted about the suspension of the @ElonJets account. Twitter has apparently also begun restricting users’ ability to tweet links to the @ElonJets Instagram account.

The suspension is not surprising considering Musk’s previous attempts to persuade Sweeney to remove the account, and his reported affinity for booting accounts who annoy him now that he’s holding the reins of Twitter. It appeared @ElonJet might have been safe, though, Musk tweeted in November that his commitment to free speech was so sincere he would not ban “the account following my plane, even though that is a direct personal safety risk.”

In November of last year, Musk reached out to Sweeney and requested he take down the account, citing security concerns. When Sweeney refused, Musk offered him $5,000 (far less than the going rate for a horse). Sweeney countered that he would remove the account for $50,000 or a new Tesla, and then an internship after Musk rejected his bargaining. Musk ultimately blocked him.

Musk’s takeover of Twitter was heralded by his fans as a renaissance for free speech on the platform, a depiction Musk was happy to lean into. But the reality of Musk’s content moderation revamp has been defined by the billionaire exercising his own petty grievances with the platform and its users, and the obliteration of tools and teams that worked to make Twitter a safer place. Musk recently authorized the release of a multi-part “Twitter Files” series in order to “expose” Twitter’s internal content moderation practices. Irvin, the new head of trust and safety, indicated on Twitter that she had provided photos showing internal restrictions placed on certain conservative accounts accused of violating content moderation policies by Twitter to writer Bari Weiss.

Despite their participation in the public condemnation of the use of back-end moderation tools, in the case of @ElonJet, it seems Musk’s new head of enforcement is happy to wield those same powers.

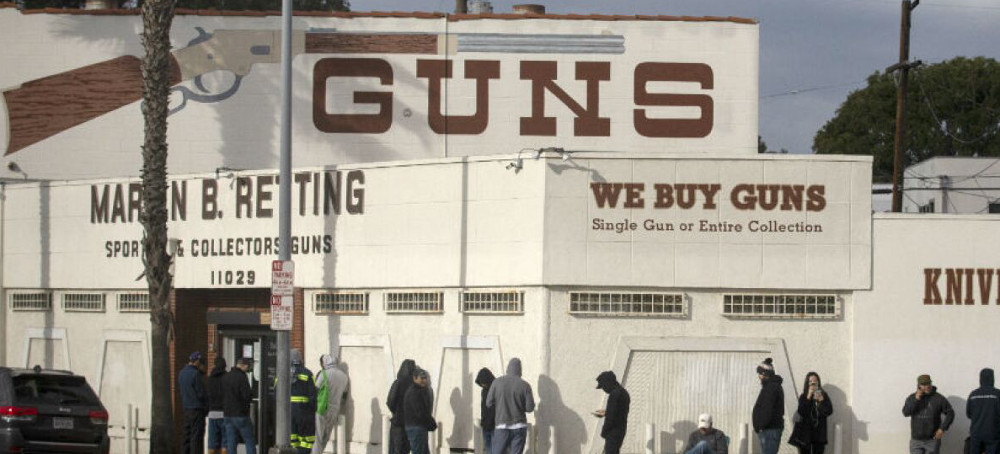

READ MORE  People wait in line outside to enter a gun store in Culver City, California, in March 2020. (photo: Patrick T Fallon/Reuters)

People wait in line outside to enter a gun store in Culver City, California, in March 2020. (photo: Patrick T Fallon/Reuters)

Estimated number of US gun owners has grown by 20 million in recent years, which experts say may lead to more firearm deaths

In a country where the leading cause of gun death is gun suicide, public health experts say a growth in gun ownership is likely to lead to more deaths.

In the 10 years since the mass shooting at Sandy Hook elementary school, the US gun safety movement has gained some political power, while the National Rifle Association has been weakened by internal disputes and legal battles. At the same time, overall gun ownership in the US appears to have grown.

People who choose to own guns are still a minority of the US population, with about a third of Americans saying they personally own a gun, and fewer than half saying they live in a house with a gun, according to survey estimates.

But the total number of American gun owners appears to have risen in recent years. One large survey conducted by Harvard and Northeastern University researchers estimates that the number of American gun owners rose by 20 million since 2015, from an estimated 55 million to 75 million people.

The number of Americans who choose to carry guns in public also appears to be rising, with 16 million people saying in 2019 that they carried a handgun at least once a month, and 6 million saying they did so daily, according to a new research study. That’s roughly double the number who said they regularly carried handguns in public in 2015.

Surveys over the past few decades show that an increasing proportion of Americans say they own a gun for self-defense, not hunting or recreation, said Deborah Azrael, a Harvard firearms researcher. In 2021, Gallup found, 88% percent of gun owners cited “crime protection” as their reason for owning a firearm.

Americans’ perception of the risk of crime and violence has often not lined up with reality: Gallup also found that, for nearly three decades, large majorities of Americans said almost every year that crime had risen nationally since the year before, even in the years when it was falling sharply. In 2013, Pew found that the majority of the public was simply unaware that the country’s gun homicide rate had fallen nearly 50% since 1993.

In the past three years, the coronavirus pandemic, nationwide protests against police violence and the insurrection at the US capitol supercharged US gun sales, with an estimated 5 million Americans becoming gun owners in 2020 and 2021, researchers found.

The top reasons for buying a gun early in the pandemic, according to a survey of California residents, were concerns about lawlessness, concerns about people being released from prison, the “government going too far,” and “government collapse.”

“When social problems happen, guns are one of the tools at the disposal of Americans”, and for many Americans, they are “a familiar tool”, Jennifer Carlson, a sociologist who studies US firearms culture, told the Guardian in an early 2020 interview, as gun sales surged. “If there’s a run on toilet paper, what’s going to be next? It’s just the prudent thing to get a gun.”

The majority of US gun owners are still white men, and the largest proportion live in the South, according to survey data. But research studies and gun industry sources agree that the demographics of gun ownership is shifting, with women estimated to make up half of new gun purchasers since 2019, and people of color making up nearly half, according to one major survey. Between 2019 and 2021, an estimated 5% of Black adults in the United States bought a gun for the first time.

Because of the political influence of gun rights advocates, there is no official government data on how many Americans own guns, or even exactly how many guns there are in civilian hands. Estimates range from 345m to 393m to more than 420m, according to the firearm industry trade group’s most recent data.

While there’s lots of interest in the eye-popping total number of guns in the US, “what matters is how these guns are distributed across people and households”, said Matthew Miller, a Northeastern University professor who specializes in firearm research, and what that distribution means for their increased risk of gun suicide, homicide or accidental injury.

His 2021 study found that a surge of gun buying before and during the pandemic meant that an additional 5 million US children now live in households with guns.

The best proxy for US gun sales over time is examining the number of federal criminal background checks conducted on gun sales by licensed firearms dealers. (In many states, individuals can sell guns to each other without any background check.)

Two widely cited estimates, both based on the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms’ background check statistics, put the number of gun sales in the US since January 2013 at around 150m, though that figure is likely an undercount.

Because Americans can buy multiple firearms at one time with a single background check, and because some states also allow people with a concealed weapons license to buy guns without background checks, the actual number of gun sales in the past decade is almost certainly higher than 150m, said Mark Oliva of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, a gun industry trade group that estimates there were at least 152m guns sales since January 2013.

At the same time, the number of background checks over the past decade will also include some double-counting of the same guns re-sold between people, said Jurgen Brauer, the co-founder of Small Arms Analytics, a firearms data company. Brauer estimates that, by the end of December, the total number of US gun sales in the past decade will reach nearly 164m.

Gun deaths have been rising in recent years, with a stark 35% increase in the nation’s firearm homicide rate in 2020, but a study that examined the pandemic surge in gun sales and increase in gun murders at the state level found no evidence of a clear association.

There were nearly 21,000 firearm homicides and more than 26,000 firearm suicides across the US in 2021, according to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

READ MORE  A sign depicting former president Barack Obama, the late Rep. John Lewis and Martin Luther King Jr. appears outside a polling location during last week's runoff election in Georgia. (photo: Dustin Chambers/Bloomberg)

A sign depicting former president Barack Obama, the late Rep. John Lewis and Martin Luther King Jr. appears outside a polling location during last week's runoff election in Georgia. (photo: Dustin Chambers/Bloomberg)

And the timing is certainly conspicuous. That’s because Republicans have just come off yet another loss in a crucial Senate runoff — their third in the past two years.

Would the move obviously advantage the GOP? That’s not clear.

What is evident is that runoffs aren’t as favorable for the GOP as they once were. In 10 Georgia runoffs held between 1992 and 2018, Republicans won nine of 10 races and improved their vote shares in eight of the 10 races. That includes Raffensperger’s own 2018 race, in which he turned a 0.4-point edge on Election Day into a 3.8-point win.

In four of those races, Republicans overturned a deficit. The average shift over that span? In the GOP’s favor by more than five points, on the margin.

The story of the past two years has been very different. Democrats not only won all three Senate runoffs held after the 2020 and 2022 elections, they improved their performances over the general elections in each.

They gained about three points in each 2020 race and nearly two points in the 2022 runoff. In the former cases, they actually took fewer votes than Republicans on Election Day but later won. Democrats also closed the gap in another 2020 runoff, for the Georgia Public Service Commission, by more than two points (though their candidate ultimately lost).

Those are effectively four of the five best runoffs for Georgia Democrats in the last 30 years — and the three most consequential — all in the span of fewer than 24 months.

To be sure, there is a long history of officials changing election rules in ways that, not coincidentally, would seem to benefit their side. As FiveThirtyEight’s Geoffrey Skelley noted recently noted, that applies to the Georgia runoffs themselves.

The runoffs originated as a Jim Crow-era effort by White Georgians to dilute the political power of Black Georgians, as The Washington Post’s Matt Brown wrote recently. They were initially pushed by a segregationist state legislator who blamed his reelection loss on Black voters and later admitted the change was meant to suppress the Black vote.

Democrats lowered the runoff threshold from a majority to 45 percent in the mid-1990s after Sen. Wyche Fowler (D-Ga.) was forced into a runoff and then lost (he would have won outright under the new, lower threshold). Then Republicans took over the state and changed it back to a majority threshold after the lower one enabled Sen. Max Cleland (D-Ga.) to avoid a runoff in 1996 with less than 49 percent of the vote.

Another prominent example this century is Massachusetts Democrats repeatedly changing the state’s rules for Senate vacancies depending upon which party controlled the governor’s mansion and the ability to appoint a senator.

Raffensperger has said his recommendation was motivated by the burden that this system places on election officials, particularly after the GOP-controlled state legislature reduced the runoff period to four weeks after Election Day (runoffs were previously held in January). That placed the runoff right in the middle of the holidays and condensed officials’ work. And runoffs are more frequent now that Georgia is effectively a swing state: There have been six such elections since 2018 — after every major election — compared to eight total between 1992 and 2015.

Among the ideas Raffensperger has floated are expanding early-voting locations, lowering the threshold back down to 45 percent or adopting ranked-choice voting (as states like Alaska and Maine have). The last option is intriguing and would effectively create what advocates call an “instant runoff,” but it would seem to be a hard sell right now with Republicans who are skeptical of the idea — particularly after Trump-oriented Republicans struggled under the new system in Alaska.

Changing the runoff rules would almost certainly be dead on arrival if Republicans were still overperforming in them. But it’s far from certain that Democrats will continue benefiting from them, which might be why some prominent Democrats and civil rights groups appear open to the idea.

Democrats seem to have benefited in the 2020 runoffs because control of the Senate was at stake while President Donald Trump focused on trying to overturn his reelection loss — a move that some (including, sort of, Trump) wagered potentially hurt GOP turnout. And in last week’s runoff, the GOP appeared hamstrung by the flawed candidacy of their nominee, Herschel Walker; he had performed better on Election Day, it seemed, because more popular Republicans like Gov. Brian Kemp (R) were also on the ballot. Those are unusual dynamics that are unlikely to be replicated in future runoffs.

But runoffs do appear to have, at the very least, lost much of their utility for the GOP. Now we’ll see if other Georgia Republicans agree that it’s time to do away with (or reform) them.

READ MORE  Junior Rosario in an apartment he moved into in Lowell, Massachusetts, in October 2010. Rosario, who previously lived for 15 years on the street, was helped by the Housing First program in Massachusetts. (photo: Steven Senne/AP)

Junior Rosario in an apartment he moved into in Lowell, Massachusetts, in October 2010. Rosario, who previously lived for 15 years on the street, was helped by the Housing First program in Massachusetts. (photo: Steven Senne/AP)

“Housing first” works, but it takes money, commitment, and, well, housing.

Advocates and researchers have never had stronger evidence about the best way to most effectively house people who need it: a model known as “housing first.” As the name suggests, its focus is getting people into permanent housing and offering them support services, rather than requiring them to address mental health conditions, substance abuse, or job training first.

The housing-first model has enjoyed strong bipartisan support, and growing evidence about its effectiveness, for nearly three decades. But now it’s facing challenges on several fronts. Rising rents and a chronic shortage of affordable housing has meant it’s grown ever harder to find units for homeless people. The National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates a shortage of 7 million homes for the poorest renters in the US. Unreliable and shrinking budgets for social services have also meant people given housing are not always offered the support they’d need to really thrive under the housing-first model.

Homelessness on the streets and in shelters steadily declined throughout President Barack Obama’s second term, but the numbers began to tick back upward starting in 2017. In some high-cost cities like San Francisco, Austin, and Seattle, the highly visible crisis began sparking concern and political backlash.

Now “housing first” itself is experiencing new and unprecedented politicization. The model has been embraced by Congress, HUD, housing researchers, and national homeless organizations, but has faced growing criticism in the past few years.

The Republican-led backlash is leading to new punitive approaches, including in liberal cities. Last month, New York City Mayor Eric Adams announced a controversial new plan that could allow homeless individuals with mental illness to be involuntarily hospitalized. In April, the San Francisco Chronicle published an investigation into some of the dilapidated hotels where the city housed the formerly homeless. “This is Housing First policy in action,” declared a local journalist in a conservative policy magazine.

Some lawmakers have made clear that their new policies for homelessness should be seen as a rebuke to the housing-first model. A new Missouri law criminalizing sleeping outside on state-owned land was modeled on a template crafted by the Cicero Institute, an Austin-based conservative think tank founded in 2016 that’s opposed to housing-first policies. Stateline found nine bills introduced in six states in the past two years based on the Cicero template, but Missouri’s marked the first to pass that includes language preventing state and federal homeless dollars to be used on permanent housing.

“It’s easy to say there’s more people experiencing homelessness so ‘housing first’ must have failed, but the intervention isn’t causing homelessness,” said Ann Oliva, the CEO at the National Alliance to End Homelessness, who previously spent a decade working at HUD. “More people are struggling to afford and find housing, and homeless assistance services can’t keep up with the need.”

Still, the housing-first approach has notched successes — most notably in Houston, Texas, a city that has maintained a dedicated political commitment to housing first over the past decade. More than 25,000 people in Houston have been moved into housing over the past 10 years, yielding a remarkable 63 percent drop in homelessness since 2011.

“It’s challenging work every day, there’s a thousand barriers to overcome, but we have to do it because there is no other choice,” said Marc Eichenbaum, the special assistant to Houston’s mayor for homeless initiatives.

Housing first — and the backlash against it — explained

When Sam Tsemberis, the founder and CEO of the national organization Pathways to Housing, pioneered the housing-first model in New York City in 1992, it was a sharp departure from the previous consensus on homelessness policy.

Under the old approach, known as “housing readiness” or “treatment first,” people had to meet certain goals of stability and independence, like achieving sobriety or landing a job, to earn access to permanent housing. Housing first, by contrast, saw housing as integral to recovery, not a reward for achieving it.

In 2000, Tsemberis and his colleagues published results comparing Pathways clients with those housed through the “housing readiness” approach. Over a five-year period, 88 percent of Pathways clients remained housed compared to 47 percent of the control group.

A 2004 randomized controlled trial, the gold standard of social science research, backed up their findings. Among 225 homeless people with mental illness, participants assigned to housing-first programs obtained housing earlier and remained more stably housed compared to the control group. Another such trial, published in 2007, found that among 260 participants experiencing homelessness in New York City suburbs, those assigned to housing-first programs were more likely to maintain permanent independent housing than the control group over a four-year period. Other studies found the model was not only effective but was saving cities money.

The remarkably robust body of research has changed how policymakers and experts in the US and around the world view homelessness.

George W. Bush’s homelessness czar, Philip Mangano, promoted housing-first models around the country. Salt Lake City, Utah, was among the first large cities in the US to embrace the model in 2005, and by 2014 it was featured in numerous publications for its success in reducing homelessness.

International leaders took notice. In 2008, Canada launched the world’s largest randomized controlled trial of housing-first programs in five cities, following more than 2,000 individuals with serious mental illness over two years. The results, published in 2014, found the housing-first model was remarkably successful compared with Canada’s traditional “treatment first” approach to homelessness. Over the past decade, studies in several European countries have found similarly positive outcomes for participants. The most empirically rigorous study tracked hundreds of individuals in four French cities between 2011 and 2016, and found the randomized housing-first participants were more stably housed, spent significantly fewer days hospitalized, and saved cities money compared to those in traditional homeless treatment programs.

The evidence has found housing first works better than other approaches for all kinds of unhoused people — from individuals who are chronically homeless and experiencing serious mental health conditions to families in emergency shelters and suffering primarily from economic hardship.

Earlier this year, researchers in California announced results from a seven-year randomized trial of chronically homeless individuals in Santa Clara. The study found those in the housing-first group spent 90 percent of their nights housed on average since the study began, and made less use of psychiatric emergency services and more use of outpatient mental health services compared to the control group. “The experiment intentionally sought to try housing first for the very most complicated patients — those who society says are most hard to house — and it worked,” said study co-author Margot Kushel, who directs UCSF’s Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative.

But in recent years, conservative think tanks like the Manhattan Institute and the Heritage Foundation began ramping up their criticisms of housing first. Although Trump’s HUD Secretary Ben Carson praised the model publicly on multiple occasions, Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers released a report on homelessness in 2019 casting doubt on its effectiveness.

The Trump White House then appointed Robert Marbut, a longtime critic of housing first, to lead the US Interagency Council on Homelessness; the agency later published a report focused on the “drawbacks” and “concerning results” of housing first, and encouraged leaders to reconsider requiring sobriety and other treatments in exchange for housing assistance. (Twelve national homelessness organizations called the report “ineffective and dishonest.”)

President Joe Biden has renewed the federal government’s commitment to housing first, campaigning on the model and making it a priority for his administration with funds from the American Rescue Plan. His team has also emphasized eviction prevention, a typically ignored cause of homelessness.

Some conservatives are now drawing attention to a study published in 2021 looking at 73 chronically unsheltered individuals in Boston over 14 years. While 82 percent of program participants receiving permanent supportive housing were still housed after one year, only 36 percent still had housing after five years, and only 12 percent after 10 years. Almost half of the participants died while housed, including from conditions like cirrhosis, heart disease, and cancer.

“The human wreckage wrought by Housing First was revealed last year in Boston,” conservative commentators proclaimed this summer in The Hill.

Boston study subjects were offered fewer support services than is endorsed under the Pathways model, such as a multidisciplinary team that’s available 24/7 with full wraparound services. Study co-author Jill Roncarati told me their findings should not be used as an argument against housing first. “We firmly believe everyone should have housing, and a continuum of housing, where individuals can enter independent living options and then have access to whatever else they need in support,” she said.

“Giving folks the keys to affordable housing and leaving [them alone] will work for most families, and quite likely for individuals without serious psychiatric and medical problems ... but people with psychiatric and medical problems need more,” added Beth Shinn, a Vanderbilt professor and leading national researcher on homelessness.

Some cities are watering down housing first. That doesn’t work.

The housing-first model calls for providing individuals with permanent housing, but it doesn’t claim that housing alone is enough. Regular check-ins by trained case managers are required, as are making social and medical supports readily available. Having the services be voluntary, experts say, preserves an individual’s sense of autonomy, leading generally to higher uptake.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, some cities say they’re implementing housing-first policies, but leaders then lack the funding, services, or available housing units to make the model work sustainably and well.

Likewise, HUD, though it has embraced the housing-first model, has often deemphasized the importance of follow-up services that Pathways to Housing stresses.

“The housing-first language can be so sloppy, but the data suggests that fidelity to Sam [Tsemberis]’s model matters,” said Shinn. In the Canadian study, for example, researchers found that participants in programs that adhered more closely to the Pathways model had better outcomes in terms of housing stability, quality of life, and community integration than those in programs with looser definitions of housing first.

HUD has shifted away from spending its budget on supportive services, including health care, drug treatment, and education. As of 2021, according to a HUD spokesperson, 22 percent of HUD’s competitive homeless assistance funds went to supportive services, compared with 68 percent for housing. (In 1998, 55 percent of HUD’s budget was spent on supportive services and 45 percent was awarded for housing). The agency’s hope is that other local, state, and federal programs — like Medicaid — can fund supportive care.

This vision has proved effective for helping houseless veterans. In 2008, a housing first program began combining housing vouchers for veterans provided by HUD with case management and clinical services provided by the VA. Experts agree that the program has been successful, with homelessness among veterans declining some 55 percent since 2010.

But for unhoused people who aren’t veterans, consistent and reliable social services have been harder to guarantee. “Because the VA is a full-service health care provider, it was relatively easy to maintain” those supportive services, said Oliva, of the National Alliance to End Homelessness. “We haven’t really been able to systematically create that same level of connection nationwide with other types of mainstream systems.”

And while social services are voluntary for housing-first participants, Tsemberis told me that many mistakenly assume that no follow-up is then required for individuals after getting housing unless the tenant wants it. “The home visit is not optional, whether the person is agreeing to treatment or not,” Tsemberis said of his Pathways model. A trained case manager is supposed to regularly check in, help a person manage their life and apartment, and encourage them to consider health, mental health, and addiction support.

Roncarati, the Boston study co-author, said she agrees their results suggest more intensive supports are needed to help certain sub-populations of people experiencing homelessness. “The housing-first models that have been replicated are probably underfunded and there needs to be more support and different types of housing available,” she told me, though noted some acutely struggling individuals did “extremely well” in independent living, and researchers were “sometimes very pleasantly surprised.”

The strengths and challenges of Houston, Texas

Houston, Texas, has stood out in the United States for its dedicated commitment to implementing housing-first policies, earning positive national media coverage this year in the New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Times, and Smart Cities Dive, among others. Earlier this month, the housing advocacy group California YIMBY published a report heralding Houston’s housing-first experiment, arguing California has not been able to replicate it primarily because Houston has more abundant housing. The group praised Houston’s land use policies — including its lack of a traditional zoning code — for substantially increasing Houston’s housing supply and lowering its costs.

Leaders in Houston agree their housing supply has helped them over the last decade, but cautioned against seeing their city as some housing utopia. Much of the credit, they say, goes to the slow, dogged work of earning trust from private-sector landlords, having a strong mayor system that remained all-in on housing first, and strategically leveraging federal dollars, including from the seven federally declared disasters the city has had in the last seven years. Houston puts no local general operating funds into homelessness receives scant funds for it from its state legislature, and Texas has not expanded Medicaid.

“The theory that Houston’s success at reducing homelessness is because of its lack of zoning is a red herring,” Eichenbaum, the special assistant to Houston’s mayor for homeless initiatives, told me. “The reality is while we might not have the typical zoning that many cities have, we do zone through ordinance and the hardest piece is still siting a location. We still have to deal with NIMBYism.”

Houston began its housing-first efforts in 2011, and at the time, the city had a higher apartment vacancy rate which helped leaders more easily move unhoused individuals into open units. But the secret wasn’t that Houston’s housing code allowed them to build new units for homeless individuals easily; it was the large supply of existing apartments considered moderately priced for vouchers.

“Even without zoning there can be a lot of backlash, and the neighborhoods can still prevent new housing,” said Ana Rausch, the vice president of program operations at Coalition for the Homeless of Houston/Harris County.

Things have gotten harder in Houston since the pandemic. Average apartment rents across the city have increased 12 percent since 2019, according to the real estate firm CoStar, and within older buildings, rents have jumped nearly 14 percent. “In many Houston neighborhoods, the days of a one-bedroom for $1,000 are long gone,” reported the Houston Chronicle in September.

Homeless advocates say they’re now something of a victim of their own success; Houston leaders were so successful at moving individuals experiencing homelessness into apartments that more apartment complexes now have low vacancy rates, making them newly attractive to investors. Some of these complexes have been purchased by new owners who now have little interest in renting to homeless people.

One asset Houston has is a strong mayor system, and two successive mayors who’ve maintained consistent support for the housing-first strategy. This makes housing first easier to coordinate than in a place like Los Angeles, for example, where 15 elected city council members all compete for power with each other and the city’s mayor.

But Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner is serving his final year now of his term-limited tenure, and advocates say they don’t know what their next mayor will want to do or what will happen when federal pandemic money dries up.

Though Houston’s future strategy is unclear, researchers agree that the city’s land use policies merit broader attention now. Increasing housing supply and helping people afford housing will be key to any successful effort to end homelessness. Zillow economists reported in 2018 that communities can expect a more rapid increase in homelessness in areas where people spend more than 32 percent of their income on rent. In 2020, the US Government Accountability Office found that every $100 increase in median rent is associated with a 9 percent increase in the estimated homelessness rate.

“It’s pretty clear that exclusionary zoning drives up housing costs, and if you have higher housing costs you’re going to have more homelessness,” said Shinn. “If we’re going to reduce homelessness, that means making housing affordable, and there’s a lot of things that go into housing affordability, and one of them is zoning.”

READ MORE  Used tires stacked at a Goodyear auto service location in South San Francisco, California, July, 2020. (photo: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg)

Used tires stacked at a Goodyear auto service location in South San Francisco, California, July, 2020. (photo: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg)

Before he clocked out, he did it again.

Goodyear shipped both specimens to a lab to measure the amount of a chemical called ortho-toluidine. The results, reviewed by ProPublica, showed that the worker had enough of it in his body to put him at an increased risk for bladder cancer — and that was before his shift. After, his levels were nearly five times as high.

It's no secret that the plant's workers are being exposed to poison. Government scientists began testing their urine more than 30 years ago. And Goodyear, which uses ortho-toluidine to make its tires pliable, has been monitoring the air for traces of the chemical since 1976. A major expose even revealed, almost a decade ago, that dozens of the plant's workers had developed bladder cancer since 1974.

What is perhaps most stunning about the trail of sick Goodyear workers is that they have been exposed to levels of the chemical that the United States government says are perfectly safe.

The permissible exposure limit for ortho-toluidine is 5 parts per million in air, a threshold based on research conducted in the 1940s and '50s without any consideration of the chemical's ability to cause cancer. Despite ample evidence that far lower levels can dramatically increase a person's cancer risk, the legal limit has remained the same.

Paralyzed by industry lawsuits from decades ago, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration has all but given up on trying to set a truly protective threshold for ortho-toluidine and thousands of other chemicals. The agency has only updated standards for three chemicals in the past 25 years; each took more than a decade to complete.

David Michaels, OSHA's director throughout the Obama administration, told ProPublica that legal challenges had so tied his hands that he decided to put a disclaimer on the agency's website saying the government's limits were essentially useless: "OSHA recognizes that many of its permissible exposure limits (PELs) are outdated and inadequate for ensuring protection of worker health." This remarkable admission of defeat remains on the official site of the U.S. agency devoted to protecting worker health.

"To me, it was obvious," Michaels said. "You can't lie and say you're offering protection when you're not. It seemed much more effective to say, 'Don't follow our standards.'"

The agency has also allowed chemical manufacturers to create their own safety data sheets, which are supposed to provide workers with the exposure limits and other critical information. OSHA does not require the sheets to be accurate or routinely fact-check them. As a result, many fail to mention the risk of cancer and other serious health hazards.

In a statement, Doug Parker, the assistant secretary of labor for occupational safety and health, acknowledged the agency's impotence. "The requirements of the rulemaking process, including limitations placed by prior judicial decisions, have limited our ability to have more up to date standards," he said. "Chemical exposure, including to o-toluidine, is a major health hazard for workers, and we have to do more to protect their health."

Agency officials did not reply to a follow-up question asking what more they will do.

Goodyear, in a statement, said it "remains committed to actions to address ortho-toluidine exposure inside our Niagara Falls facility." The company said it requires workers to wear protective equipment, invests in upgrades like ventilation and offers regular bladder cancer screenings "at no cost" to workers. It pointed out that ortho-toluidine levels at Goodyear's Niagara Falls plant had plummeted over the past decades and that the levels have "consistently been far below the permissible exposure limits as set by government regulators," meaning 5 parts per million.

James Briggs worked for 20 years in the Niagara Falls plant before taking a job with the United Steelworkers union, which represents dozens of Goodyear employees there. While pushing for changes that would reduce its members' exposure to ortho-toluidine at the plant, the union has essentially given up on eliminating the risk.

"If I could have my way, would I like to be able to wave a magic wand and take the risk away? Yes, I would," he said. "Everybody that works in that plant realizes there's some risk that comes with it. They all get it. We tell them. It's part of the orientation for new employees."

Gary Casten never got such a talk when he started at the plant in 1965, he alleged in court testimony. A devoted union leader, bowler and Yankees fan, he let the government test his urine in 1990; he, too, had a chemical level five times as high after his shift than before it. More than once in his 39 years at Goodyear, Casten's lips and fingernails turned blue, a well-known sign of ortho-toluidine poisoning.

Still, it came as a shock to Casten when he was diagnosed with bladder cancer in 2020. "If you looked up 'nice' in the dictionary, you'd see a picture of Gary," said Harry Weist, one of his former co-workers. Casten underwent surgery and chemotherapy and lost his strength and his appetite. It soon became clear that the cancer had spread.

Along with dozens of other Goodyear employees, he sued the chemical companies that manufactured the ortho-toluidine used at the plant; workers' compensation law prevented them from suing their employer. When asked at a legal proceeding in April 2021 whether anyone had warned him about the risks, he said, "If I had been told that from the first day I walked through the gates, I wouldn't have worked there."

He died four months later.

Last year, the grim tally of Goodyear plant workers' bladder cancer diagnoses reached 78.

The recent test results suggest it is likely to keep climbing.

'The system is broken'

Created in 1970 in response to mounting injuries, illnesses and deaths from workplace hazards, OSHA was supposed to issue regulations based on scientific research conducted by its sibling agency, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

At first, the pair got off to a somewhat promising start, with OSHA using NIOSH research to issue more protective standards for lead, arsenic, benzene, asbestos and several other carcinogens. "The goal of the early administrators was to set lower and lower and lower standards so that industries could adapt and ultimately eliminate the use of these materials," said David Rosner, a historian of public health at Columbia University.

But within a few years, asbestos, which was already well established as a carcinogen, presented a political challenge. "For asbestos, NIOSH said nothing other than a number approaching zero can be considered safe," said Rosner. "But then they sent that science over to OSHA, and OSHA realized if you do that you're going to have to shut plants everywhere."

Chemical companies pounced, warning that OSHA's standards would lead to job losses amid a recession; they turned the agency into "a whipping boy for why American industry was in chaos," as Rosner put it. By 1973, the Asbestos Information Association/North America suggested that health-based regulation of its members' product might be a "nefarious conspiracy afoot to destroy the asbestos industry."

Two years later, the director of NIOSH declared that there was "virtually no doubt that asbestos is carcinogenic to man" and proposed lowering the safety threshold. But OSHA hedged. It acknowledged that no detectable level of asbestos was safe, but put off changing its standard due to a legal requirement to take "technical and economic factors" into consideration.

While OSHA eventually updated its asbestos standard more than a decade later, lawsuits helped chill — and ultimately all but freeze — progress on setting limits for most chemicals by requiring the agency to do more and increasingly complex analyses.

One such suit, brought by the American Petroleum Institute and decided by the Supreme Court in 1980, challenged OSHA's limit for benzene. Although there was no scientific question that benzene causes leukemia, the court decided that, before setting a new standard, OSHA would have to first establish that the old one put workers at "significant risk" of harm. Another lawsuit, filed by the lead industry, left OSHA responsible for not just calculating the costs of complying with its standards but also demonstrating "a reasonable likelihood" that they would not threaten "the existence or competitive structure of an industry."

Faced with massive requirements for updating a single limit, in 1989 OSHA tried another tack: lowering and setting safety thresholds for 428 chemicals at once. The move could have prevented more than 55,000 lost workdays due to illness and an average of 683 fatalities from hazardous chemicals each year, according to the agency's estimates.

But that attempt was stymied, too. The American Iron and Steel Institute, the American Mining Congress, the American Paper Institute, the American Petroleum Institute and the Society of the Plastics Industry were among the dozens of trade associations that joined to sue OSHA, criticizing the agency's decision to lump the chemicals together and claiming that they had inadequate time to respond to the proposed changes. While most unions supported the agency's effort, some sued OSHA as well, arguing that some of the updated standards were not protective enough.

In 1992, the court of appeals vacated all of the safety limits that OSHA had set and updated three years earlier, finding that the agency had failed to prove that exposure to the chemicals posed a significant risk of health impairments and that the proposed changes were not economically and technologically feasible for the companies that used the chemicals.

By the time he was appointed to run OSHA in 2009, Michaels was well aware of the risks of the chemical used at Goodyear. Just before he took the helm of the agency, he devoted a chapter of his book about industry influence over science to ortho-toluidine, chronicling the cancers at the Niagara Falls plant and the fact that manufacturers had evidence of the chemical's carcinogenicity as far back as the 1940s.

But given how onerous the limit-setting process had become — and how many other chemicals were in even more desperate need of accurate limits, in part because greater numbers of workers were exposed to them — he decided not to attempt to update the ortho-toluidine standard.

In the past 25 years, OSHA has updated just three standards.

Forced by a lawsuit, in 2006 the agency issued a standard for chromium, the carcinogen featured in the movie "Erin Brockovich," which was also causing cancer at exposure levels far below its outdated limit. In 2016, OSHA issued a protective standard for silica, a cancer-causing dust that millions of workers are exposed to each year. And, in 2021, OSHA finalized an exposure limit for beryllium, an element whose prior limit was more than 70 years old. Every year, thousands of shipyard and construction workers are exposed to beryllium, which can scar the lungs and cause cancer. Each update took more than a decade to complete as the agency amassed the voluminous data it needed to justify the changes.

While the 1972 standard for asbestos was just five pages long, the one for silica stretched across 600 pages. "And that's mostly because of the requirements that followed all these lawsuits," said Michaels, who worked on the silica standard throughout his time as administrator and is now a professor at the George Washington University School of Public Health.

Michaels argues the problem isn't the agency itself as much as its small budget and the court-imposed burdens resulting from the lawsuits.

"Don't blame OSHA," said Michaels. "The system is broken."

'A form of self regulation'

Tucked in a binder in the foreman's office at the Goodyear plant is another tool that might have helped workers. Since 1983, OSHA has required chemical manufacturers to create safety data sheets: documents that present clear information about a chemical's hazards. Workers and employers consult these to make decisions on what kinds of precautions to take.

OSHA does not routinely check to see whether the data sheets contain inaccuracies or even require them to be accurate. Companies must note carcinogens as cancer-causing only if they are on OSHA's own very truncated list, which notably omits ortho-toluidine. OSHA specifies that companies "may" rather than "must" rely on the National Toxicology Program or the International Agency for Research on Cancer for determinations on whether a chemical causes cancer.

In comments submitted to OSHA in 2016, the advocacy groups Earthjustice, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the BlueGreen Alliance said the agency's hands-off approach ignored the inherent conflicts of interest.

"Allowing manufacturers to disregard hazard assessments by two authoritative bodies and to conduct their own hazard assessment of products in which they have significant financial investment is a form of self-regulation that will undoubtedly compromise transparency, accurate and timely disclosure of information, and ultimately workplace health and safety," the environmental organizations wrote.

The groups suggested the agency should take the job of evaluating chemicals away from the companies that make them. But OSHA again failed to act. As a result, experts say, the safety data sheets for hazardous chemicals are still riddled with errors.

Almost one-third of more than 650 sheets for dangerous chemicals contain inaccurate warnings, according to a study, published today, that was conducted by the BlueGreen Alliance, an organization that focuses on the intersection of labor and environmental issues, and Clearya, a company that alerts consumers to the presence of toxic chemicals in products. Of 512 sheets for carcinogenic chemicals the groups reviewed, 15% did not mention cancer in the hazards identification section, and 21% of 372 safety data sheets for chemicals that pose a risk to fertility and fetal development omitted that fact.

Even sheets for well-known carcinogens like benzene and vinyl chloride often don't include warnings that they cause cancer. One for asbestos, for example, fails to say in its hazard section that the mineral causes lung cancer and mesothelioma, instead warning only of skin irritation, serious eye irritation and the possibility of respiratory irritation.

While the inaccuracy of safety data sheets is a global problem, companies in the U.S. are among the worst offenders, according to the analysis by the BlueGreen Alliance and Clearya. Safety data sheets in the U.S. are far more likely to be missing information about health hazards than those in Europe, their analysis showed. In part, that's because of differing approaches to regulating chemicals.

"In other jurisdictions like Europe, Australia and Japan, they say, 'There's a list of chemicals we're concerned about, and here's how we're classifying them.' So they can't play around with the truth," said Dorothy Wigmore, an industrial hygienist based in Canada.

By law, OSHA can fine companies no more than $14,502 for each violation of its hazard communication standard, which amounts to a slap on the wrist for most companies, according to experts. The agency most recently responded to a complaint at the Goodyear plant in 2015, when it issued a citation for violation of its Respiratory Protection Standard but did not issue a fine.

Of the regulatory approach to safety data sheets in the United States, Wigmore said, "It's a series of situations that are just designed to let all kinds of hazards get out into the marketplace."

'Impermissible secrecy'

The primary law governing the regulation of chemicals in the United States, called the Toxic Substances Control Act, contains a provision designed to keep chemical makers honest and the public informed.

If companies that manufacture, import, process or distribute chemicals find any evidence that their products might present a substantial risk to human health or the environment, they must immediately share that information with the Environmental Protection Agency.

DuPont, which had supplied ortho-toluidine to the Goodyear plant since 1957, had just that kind of information back in 1993. An industrial hygienist named Tom Nelson who worked at DuPont calculated that the permissible exposure level was at least 37 times too high to protect workers.

Almost three decades later, an attorney named Steven Wodka stumbled upon Nelson's calculations while reviewing thousands of documents he had obtained from the company through discovery, in cases his clients — Goodyear plant workers, including Casten — brought against DuPont. The information should have been public. Yet, when Wodka checked Chemview, an EPA database that contains such information supplied by companies known as 8(e) reports, he found no mention of Nelson's bombshell discovery. The agency did make public five reports that DuPont submitted about the chemical, but none disclose the calculations showing just how ineffective the permissible exposure level is.

In January 2021, Wodka wrote to the agency to report that DuPont was violating the 8(e) provision of the chemicals law by withholding information about just how dangerous ortho-toluidine is.

"There is a direct connection between DuPont's failure to abide by this statute and the continuing cases of bladder cancer in the Goodyear workers in Niagara Falls, New York," the letter stated, before urging the EPA administrator to "enforce this statute to its full extent against DuPont."

After months of silence, Wodka received a response from the EPA this September. "We did not take further enforcement action because we had a document that demonstrated that they met their 8e obligations," Gloria Odusote, a program manager in the agency's waste and chemical enforcement division, wrote to Wodka. She said the document contained "confidential business information" and was exempt from public disclosure.

The kind of exemption she cited was designed to allow companies to keep secret information that could give their competitors a window into their business practices, such as manufacturing processes and chemical formulas whose disclosure could "cause substantial business injury." But companies routinely use the exemption to shield all kinds of information, including the names of chemicals, the amounts produced and the location of plants that make them. The chemicals law forbids companies from claiming health and safety studies as confidential business information.

"EPA can't keep this information secret," said Eve Gartner, an attorney who directs the Toxic Exposure … Health Program at Earthjustice. The agency's failure to list the document on Chemview and make it available to the public upon request, she said, "adds an additional layer of impermissible secrecy."

DuPont declined to comment, noting in an email that ortho-toluidine was produced by "E.I. du Pont de Nemours … Co., not DuPont de Nemours," as the company now calls itself after relaunching in 2019. It has settled all 28 lawsuits in which Wodka represented Goodyear workers with bladder or urothelial cancer.

EPA officials said they are looking into the matter.

'Shouldn't have to struggle like this'

On a snowy November morning in western New York, Harry Weist awaited his next cystoscopy. A 66-year-old retired Goodyear worker with a graying buzz cut and a horseshoe mustache, Weist has already undergone dozens of these tests, in which a tiny camera is inserted through his urethra and into his bladder. On three occasions, in 2004, 2019 and 2020, the images revealed cancerous tumors that had to be surgically removed.

It can take days and sometimes weeks for the pain and discomfort from the surgery to ease. What never goes away, though, is the dread about the cancer that future probes will find. "My doctor said it's not if it will return, but when," Weist said.

During his 34 years working at the Goodyear plant, Weist ran the Super Bowl pool, served in the union and became "thick as thieves" with a few of his co-workers. He also breathed in fumes so stinging and strong that he was left gasping for air. But on that November day, he preferred to think about the lifelong friends he made at the plant.

One, a close relative who has also had three bouts of bladder cancer and undergone chemotherapy, radiation and surgery to treat it, has gotten a job delivering car parts at age 84 to cover some of his medical costs. According to Weist, the family member (who declined to be interviewed) is so loyal to the company that "if you cut him, he would bleed Goodyear blue." Weist makes the joke affectionately; the men remain close, even as they sharply disagree about their former employer.

"He says we made these bills so we're going to pay them," Weist said. It is difficult to definitively prove the cause of any individual cancer. But Weist feels sure his and that of his relative were due to decades of extreme exposure to a chemical known to cause bladder cancer. "I tell him, 'Goodyear gave us cancer. We worked at their factory and wound up getting bladder cancer. You shouldn't have to struggle like this.'"

Weist thinks often of Casten, who died at 74, leaving behind a daughter and grandkids who called him Popcorn. Like his old friend, Weist would have made a different choice had he been warned about the risks of working around ortho-toluidine. "Of course I wouldn't have taken the job if I knew I was going to go through this," he said.

Last year, NIOSH scientists published a risk assessment of ortho-toluidine that put the finest point yet on exactly how dangerous the chemical is — and how egregiously wrong the permissible exposure limit remains. OSHA says it strives to keep worker risk under one in 1,000, meaning one in every thousand people being harmed, after the Supreme Court suggested this threshold more than four decades ago. To bring the risk at the Goodyear plant to that range, the safety threshold for ortho-toluidine in the air should be about one three-thousandth that level, the assessment concluded.

The current permissible limit, 5 parts per million, is the same as 5,000 parts per billion. Yet even just 10 parts per billion in the air would cause each 1,000 exposed workers to contract between 12 and 68 "excess" cases of bladder cancer, meaning the number they'd likely develop above the number expected in the general population, according to the study.

The average amount of ortho-toluidine in the air at the plant is even higher: 11.3 parts per billion, according to testing completed by Goodyear in 2019. The company said that it has continued to measure air concentrations of the chemical in the plant since then, but declined to share results of that testing with ProPublica.

That measurement along with pre- and post-shift urine samples from workers at the plant "provide conclusive evidence that the Niagara Falls workers are still absorbing ortho-toluidine into their bodies during the workshift," Wodka wrote to OSHA in March in a petition co-authored by a physician and a toxicologist who have served as expert witnesses in Goodyear worker cases, as well as an epidemiologist who previously worked for the American Cancer Society and the U.S. Public Health Service.

The occupational health experts asked OSHA to update the standard. Specifically, they asked that the permissible exposure limit in air for eight hours be reduced from 5,000 parts per billion to 1 part per billion and that the agency require companies to clearly inform their workers that the chemical causes bladder cancer.

OSHA has not responded to their petition.

READ MORE  Shipping containers line the U.S. and Mexico Border at Coronado National Memorial in Cochise County, Arizona. (photo: Rebecca Blackwell/Bloomberg)

Shipping containers line the U.S. and Mexico Border at Coronado National Memorial in Cochise County, Arizona. (photo: Rebecca Blackwell/Bloomberg)

Protesters Block Construction of Arizona Border Wall Made of Shipping Containers

Alicia Victoria Lozano, NBC News

Lozano writes: "What started as a small demonstration has turned into a two-week standoff as residents and environmentalists fight outgoing Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey's effort to wall off sections of the U.S.-Mexico border with shipping containers."

READ MORE  The area impacted by the Keystone pipeline rupture and subsequent oil discharge into Mill Creek near Washington, Kansas. (photo: EPA)

The area impacted by the Keystone pipeline rupture and subsequent oil discharge into Mill Creek near Washington, Kansas. (photo: EPA)

The pipeline, owned by Canada-based TC Energy, had previously leaked about 12,000 barrels of oil in 22 separate incidents since it began operating in 2010, according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report published last year.

In that sense, last week’s spill is historically significant in its own right. But pipeline safety experts and environmental advocates say the rupture is also an example of what’s at stake as federal lawmakers consider overhauling the environmental review process for energy infrastructure—a move that could fast track billions of dollars of new fossil fuel pipelines already in the process of being built across the nation.

Speeding that federal approval process has become one of the oil and gas industry’s top priorities in the next Congress. A streamlining proposal that was championed by West Virginia’s Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin was effectively blocked in the Democratically controlled House of Representatives. But with Republicans taking control of the House in January, the industry sees a new opportunity to advance what perhaps could be a more sweeping plan—one spearheaded by the GOP that could pick up fossil fuel-friendly Democrats in the Senate like Manchin, though approval there would most likely be difficult.

“Permitting reform is essential for us,” Frank Macchiarola, senior vice president of the American Petroleum Institute, said during a post-election forum in November.

Although much of the industry’s focus has been gaining approvals for natural gas pipelines, like the Mountain State Pipeline project in West Virginia favored by Manchin, the United States has more proposed oil pipelines in the works than any other nation, according to a recent analysis by the Global Energy Monitor in California. Some 1,800 miles of new U.S. oil pipelines—$8 billion worth of infrastructure projects—are in the works, mostly in the Permian basin of Texas.

It is part of a worldwide trend. Global Energy Monitor estimated that there currently are nearly 15,000 miles of oil pipelines proposed or under construction worldwide. That’s despite growing calls from the public to transition to renewable energy as a way to curb climate change, another major criticism from environmentalists who oppose Manchin’s push to overhaul the federal permitting process.

With the investigation ongoing, the cause of last week’s spill in Kansas is still unclear. But environmental groups have questioned whether it was related to a special permit the Keystone pipeline received from the Trump administration in 2017, making it the only oil pipeline in the U.S. that can run on a higher pressure than federal regulation allows. The pipeline has seen a notable uptick in incidents since that permit was issued, including three significant spills in the last five years.

In fact, last week’s spill now puts Keystone’s safety performance below nationwide averages, according to reporting by CBS News. And according to the nonprofit watchdog organization Pipeline Safety Trust, Keystone has averaged one significant failure per year during its lifetime.

Bill Caram, Pipeline Safety Trust’s executive director, said in an interview that Keystone’s track record raises serious questions about how and why the pipeline received its permits, and he worries that streamlining that process for the sake of saving the industry money could result in more spills like the one in Kansas.

“As far as permitting reform, I think the continued spills on this pipeline illustrate the risks pipelines pose, especially when there are construction and pipe integrity issues,” Caram said.

TC Energy didn’t respond to questions from Inside Climate News, but the company announced Monday that it has so far recovered about 2,600 barrels of crude. Much of the spill had flowed downstream into a nearby local creek that connects to the larger Missouri River basin. State and federal officials have said that the spill appears to be contained, and that so far there’s no evidence that drinking wells have been contaminated or that wildlife has been harmed.

Richard Kuprewicz, who has worked in the energy sector for 50 years and is president of the pipeline safety consulting firm Accufacts Inc., said it’s still too soon to draw conclusions about the cause and environmental impacts of last week’s spill. But the fossil fuel industry’s outsized influence on federal energy policy is well known, he said, and if the Keystone investigation reveals that last week’s oil spill was caused in part by a failure in the regulatory process, he hopes that Congress takes the issue seriously.

“I understand … on these multibillion dollar projects—with the time value of money—that yeah, we want to rush these things through,” he said. “But if it turns out that it’s something where there was a serious gap in the regulations, we need to address that.”

Pipeline operators have long touted their ability to run their infrastructure safely, often pointing to new technological advances that help them detect and mitigate leaks more quickly. But past reporting from Inside Climate News has revealed those technologies often miss the leaks they’re designed to catch, aren’t always built into projects in the first place and are susceptible to human error even when they are running properly.

Research also suggests that climate change itself poses a growing threat to fossil fuel infrastructure, including pipelines. More frequent and destructive extreme weather, rising sea levels and rapid temperature swings and melting permafrost in the Arctic can directly damage pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure that wasn’t designed with global warming in mind. A study published this year in the Journal of Marine Science and Engineering found that climate change can increase oil spill risks in the coastal and offshore regions. And our own reporting on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline shows how melting glaciers and shifting land mass pose a serious threat to that pipeline system.

For Kuprewicz, he hopes Congress weighs all these factors before they commit to making any major changes to the federal permitting process. “Congress needs to be very careful that they balance what’s good for the country, what’s good for the population,” he said. “Money can make a group of very smart people do incredibly stupid things. And time and time again, I see that.”

Thanks for reading Today’s Climate. And a special thanks to my colleague Bob Berwyn for his help researching and writing today’s issue. I’ll be back in your inbox Tuesday.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.