Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Which is why he'd rather not, thank you.

In a statement issued Wednesday on the Republican’s behalf, Graham’s attorneys called the Fulton probe a “fishing expedition.” Lawyers Bart Daniel and Matt Austin indicated the senator did nothing wrong when he called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and his staff after the 2020 elections to ask about procedures for counting absentee ballots. “As Chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Senator Graham was well within his rights to discuss with state officials the processes and procedures around administering elections,” Daniel and Austin wrote.“Should it stand, the subpoena issued (Tuesday) would erode the constitutional balance of power and the ability of a Member of Congress to do their job.” They concluded, “Senator Graham plans to go to court, challenge the subpoena, and expects to prevail.”

Wait a moment. Leave aside the fact that Graham was no more representing the Senate Judiciary Committee when he contacted Raffensperger than he was representing the Sacred College of Cardinals. He was plainly calling as a campaign operative. Graham’s lawyers are telegraphing the fact that they intend to stretch the limits of the Senate “speech and debate clause” halfway to Neptune.

The “Speech and Debate” clause of the U.S. Constitution shields members of the House and Senate from being questioned in court about their legislative activities and the motivations behind them. But prosecutors are likely to argue that Graham was acting far outside of his official duties when he questioned the top elections official of another state.

In addition, the entire conservative judicial project is now moving headlong into giving state legislature nearly absolute authority over all elections. In that scenario, if we’re being completely honest, then Senator Lindsey Graham, United States Senator from South Carolina, has no damn business involving himself in how Fulton County, or the state of Georgia, run their elections. He’s free to argue this, and he might even get a sympathetic judge, but it’s a preposterous position for him to take. A grand jury in Georgia is no threat to separation of powers, especially in our modern states-rights context. But Senator Graham would rather not, because he knows what the grand jury wants to know.

Meanwhile, in Washington, Pat Cipollone, the former White House counsel, has decided that, yes, he will, but only within limits and behind closed doors. From NBC News:

The interview with Cipollone will be transcribed and videotaped, according to a person familiar with the matter. His appearance before the panel comes as a result of a subpoena issued to him last week. The committee didn't return a request for comment. Cipollone, considered a critical witness whose testimony lawmakers have suggested is a missing link, previously met with committee investigators in April for an informal interview. The former White House lawyer had previously resisted cooperating with and speaking formally with the panel.

Small steps, granted. But I can’t blame the committee for wanting to hear from Cipollone in private. He’s a reluctant witness cloaked in an arguable assertion of privilege. Better find out the parameters of what he’s willing to say to the committee first. Then, when (or if) they bring him out into a public hearing, they’ll know what they’ll get. The one thing this committee has been careful to avoid is having its public hearings hijacked the way the special Iran-Contra hearings were hijacked by the bluster and medals of Oliver North. Maybe, one day, even Senator Lindsey Graham will rediscover his constitutional duty, too. Or not.

U.S. basketball player Brittney Griner, who was detained in March at Moscow's Sheremetyevo airport and later charged with illegal possession of cannabis, is escorted before a court hearing in Khimki outside Moscow, Russia, July 1, 2022. (photo: Evgenia Novozhenina/Reuters)

U.S. basketball player Brittney Griner, who was detained in March at Moscow's Sheremetyevo airport and later charged with illegal possession of cannabis, is escorted before a court hearing in Khimki outside Moscow, Russia, July 1, 2022. (photo: Evgenia Novozhenina/Reuters)

The move is not expected to end her trial in Khimki, Russia, anytime soon. Even with a guilty plea in Russian criminal courts, the judge will continue to read the full case file into the record, and it could still go on for weeks or months.

Griner, who was detained at Moscow's Sheremetyevo Airport on Feb. 17, told the court that she packed vape cartridges accidentally and did not intend to break Russian law.

"I'd like to plead guilty, your honor. But there was no intent. I didn't want to break the law," Griner told the judge in English, which was then translated into Russian for the court.

The next court hearing was scheduled for July 14. Griner, who asked the judge for "time to prepare" her testimony, faces up to 10 years in prison if convicted of large-scale transportation of drugs.

"We of course hope for the leniency of the court,'' her lawyer, Maria Blagovolina, told reporters outside the court. "Considering all the circumstances of the case, taking into account the personality of our client, we believe that the admission of guilt should certainly be taken into account.''

The State Department issued a statement Thursday saying it continues to work for Griner's release.

Elizabeth Rood, deputy chief of mission at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, told reporters after the hearing that she spoke to Griner in the courtroom and shared a letter from President Joe Biden.

"She's eating well, she's able to read books and under the circumstances she's doing well,'' Rood said of Griner.

"I would like again to emphasize the commitment of the U.S. government at the very highest level to bring home safely Ms. Griner and all U.S. citizens wrongfully detained as well as the commitment of the U.S. Embassy in Moscow to care for and protect the interests of all U.S. citizens detained or imprisoned in Russia."

Before Thursday's hearing, Russian police escorted Griner, handcuffed and clad in a bright red T-shirt and sweatpants, into the courtroom past a crowd of journalists. She also held a photo of her wife, Cherelle.

Sources said the guilty plea to charges of drug possession and smuggling was a strategy to help facilitate a prisoner swap that could bring Griner home, and it also was a recognition that there was no way she was going to be acquitted.

U.S. officials and Russia experts have described the trial, which was in its second day, as "theater," with a guilty verdict seen as a foregone conclusion.

Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov warned Thursday that "attempts by the American side to make noise in public ... don't help the practical settlement of issues.''

The White House said Biden called Griner's wife on Wednesday to assure her that he's doing all he can to obtain the athlete's release as soon as possible. They spoke after Biden read a letter from Griner in which she said she feared she'd never return home.

There is no timetable for the length of the trial, but the real resolution to Griner's case is expected to be a deal that brings one or more Russians currently in U.S. custody back to Russia in exchange for the release of Griner and possibly another American, Paul Whelan, who has been detained in Russia since December 2018.

Russia has sought the release of an arms dealer named Viktor Bout, who is serving a 25-year sentence in the United States for supporting terrorism. But sources have said there are voices in the Biden administration who have argued against releasing Bout, who is known by the nickname "the Merchant of Death."

Experts have said any deal to release Griner would almost certainly require an admission of guilt by the American star, regardless of the facts. A source familiar with the strategy said that by pleading guilty, Griner gets that out of the way. And while it could complicate public reaction to her case, one source said the thought was to just get her home however possible and deal with the fallout when she returns.

Ryabkov noted that until Griner's trial is over, "there are no formal or procedural reasons to talk about any further steps.''

He warned that U.S. criticism, including a description of Griner as wrongfully detained and dismissive comments about the Russian judicial system, "makes it difficult to engage in detailed discussion of any possible exchanges.''

"The persistence with which the U.S. administration ... describes those who were handed prison sentences for serious criminal articles and those who are awaiting the end of investigation and court verdicts as 'wrongfully detained' reflects Washington's refusal to have a sober view of the outside world,'' Ryabkov said.

The trial of the Phoenix Mercury star and two-time Olympic gold medalist was adjourned after its start last week because two scheduled witnesses did not appear. Such delays are routine in Russian courts, and her detention has been authorized through Dec. 20.

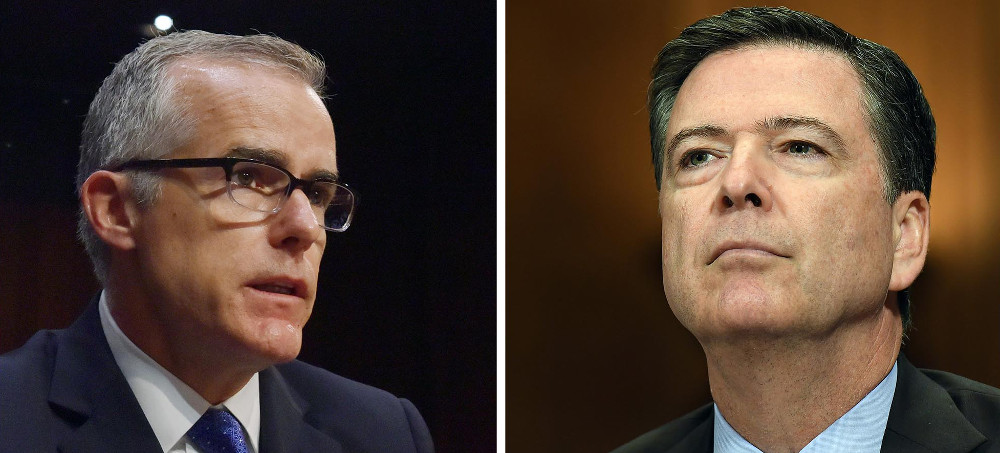

Andrew McCabe, left, and James Comey. (photo: Getty)

Andrew McCabe, left, and James Comey. (photo: Getty)

Former director James B. Comey and his deputy, Andrew McCabe, were selected for tax reviews the IRS says are random

The requests came a day after reports that the IRS initiated detailed reviews into the tax records of James B. Comey, the former FBI director, and Andrew McCabe, a deputy who later took over the agency. The two officials at the time had been primary targets of Trump’s ire after they probed the president in connection with his 2016 campaign, leading Comey to raise the possibility this week that the newly revealed audits amounted to political payback.

Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, said in a statement a “thorough investigation of this matter is crucial” — adding his panel would “look at what steps” it can take on its own.

“Donald Trump has no respect for the rule of law, so if he tried to subject his political enemies to additional IRS scrutiny that would surprise no one. We need to understand what happened here because it raises serious concerns,” Wyden said.

Rep. Kevin Brady (R-Tex.), the top Republican on the tax-focused House Ways and Means Committee, separately said in a statement he would support “investigating all allegations of political targeting.” But Brady pointed to assurances from Trump-appointed IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig, who said he had no communications with Trump, and the GOP congressman also mounted a political broadside against the agency for allegedly targeting conservatives under President Barack Obama.

The bipartisan political blowback nonetheless reflected the seriousness of the allegations and the long-simmering distrust of the IRS on Capitol Hill. For some, the news even invoked the specter of the disgraced Nixon administration, when the president leveraged the IRS — and its vast powers to look into Americans’ finances — to pursue his political enemies before he was forced to resign.

An investigation into the matter would be carried out by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, or TIGTA, which typically opens probes at lawmakers’ request. Wyden said that Rettig told him in a conversation that “any allegations of wrongdoing are taken seriously and are referred to the [inspector general] for further review.” A senior government official familiar with the matter, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss it, said Rettig had referred the issue to TIGTA. A spokesperson for TIGTA did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The IRS, meanwhile, stressed in a statement that Rettig personally “is not involved in individual audits or taxpayer cases,” which instead are handled by “career civil servants.”

“As IRS Commissioner, he has never been in contact with the White House — in either administration — on IRS enforcement or individual taxpayer matters,” the agency said. “He has been committed to running the IRS in an impartial, unbiased manner from top to bottom.”

For years, Trump has repeatedly and publicly attacked Comey and McCabe, calling for them to be charged with crimes and accusing them of pursuing a politically motivated witch hunt against him. While both men were investigated, and at times criticized for their conduct, neither was charged with any crime.

The types of IRS audits they experienced are designed to be rare and random. The likelihood that two people so loathed by the former president would get audited within the space of a few years raised concerns for Comey about possible political misuse of the IRS’s authority.

“I don’t know whether anything improper happened, but after learning how unusual this audit was and how badly Trump wanted to hurt me during that time, it made sense to try to figure it out,” Comey said in a statement. “Maybe it’s a coincidence or maybe somebody misused the I.R.S. to get at a political enemy. Given the role Trump wants to continue to play in our country, we should know the answer to that question.”

A lawyer for McCabe confirmed he, too, was audited.

The New York Times, which first reported the audits, said Comey’s audit began in 2019, focused on his 2017 tax return, the year he signed a seven-figure book deal. McCabe’s audit began in 2021, focused on his tax return for 2019, the Times said.

The McCabe audit was launched months into the Biden administration.

Since politically motivated abuses in the Nixon administration, the IRS has prided itself on systems designed to keep politics or personal motivations out of the agency’s tax review process. Asked for comment on the Comey and McCabe audits, the IRS said in a statement that privacy laws prevent it from discussing specific taxpayers.

“Audits are handled by career civil servants, and the IRS has strong safeguards in place to protect the exam process — and against politically motivated audits,” the statement said. “It’s ludicrous and untrue to suggest that senior IRS officials somehow targeted specific individuals for National Research Program audits.”

Two Vallejo police officers shot Mario Romero, who did not have a firearm, 30 times through the windshield of his Ford Thunderbird in 2012. It took the department four years to investigate the case, during which time each officer was involved in another fatal shooting. (photo: ProPublica)

Two Vallejo police officers shot Mario Romero, who did not have a firearm, 30 times through the windshield of his Ford Thunderbird in 2012. It took the department four years to investigate the case, during which time each officer was involved in another fatal shooting. (photo: ProPublica)

ALSO SEE: Ex-Cleveland Officer Who Fatally Shot Tamir Rice

Is Hired by Pennsylvania Borough

A California city’s flawed handling of fatal police shootings allowed six officers to use deadly force again before their first cases were decided. Experts say the department’s system "isn’t even basement standard practice” and needs oversight.

But that night, Foster was riding alone, swerving in and out of traffic lanes without a bike light, and caught the attention of officer Ryan McMahon, who pursued Foster in his car. Foster hit the brakes, and McMahon ordered him to “come over and sit in front of my car,” according to the officer’s deposition in a civil rights lawsuit filed by Foster’s family.

“Stop messing with me,” Foster responded before taking off on his bike in the opposite direction, McMahon recalled in his deposition testimony. The officer got back in his car and chased him down.

Foster soon fell from his bike and ran away. When McMahon continued the chase on foot, Vallejo policy required him to notify the department by radio. But that’s not what he did. Instead, he left his patrol car and followed Foster toward a dark walkway between two houses.

As they ran, McMahon tased the African-American man in the back without a warning, although officers are required to give one unless it puts them in danger. The officer later said he did so in part because he saw Foster grabbing his pants, causing him to think Foster had a firearm. Foster, who was unarmed, kept running but fell. As he tried to get up, McMahon pushed him, causing Foster to fall down a small flight of cement stairs, the officer testified in the lawsuit. McMahon then straddled his back.

Body camera footage shows Foster lying on the pavement without fighting back when McMahon, standing next to him, fired his Taser once more. Then the officer struck Foster in the head and body with a 13-inch metal flashlight, Foster’s family alleged in court records. As McMahon swung to hit again, Foster caught the flashlight and tried to get up.

While some facts of the case are disputed, what happened next is not: McMahon shot Foster seven times. Autopsy records show he hit Foster once in the head, four times in the back and twice on the left side of his body, killing him.

“It’s all good,” McMahon said as backup arrived minutes later. “He’s down. He’s down.”

A diverse waterfront city of 125,000 located in the San Francisco Bay Area, Vallejo has garnered national attention in recent years for its rate of police killings, which far outpaces those of all but two California cities, San Bernardino and South Gate, according to a 2019 NBC Bay Area report. Eight families of people killed by police over the last decade have filed civil suits against Vallejo, which has paid out more than $8.3 million in settlements so far, with three cases ongoing. (The single largest settlement, $5.7 million, went to the Foster family.) In July 2020, Open Vallejo exposed a tradition in which officers bent their badges to mark their fatal shootings.

Now, Open Vallejo and ProPublica have looked at what happens inside the department after those killings occur, examining more than 15,000 pages of police, forensic, and court files related to the city’s 17 fatal police shootings since 2011. Based on records that emerged after dozens of public records requests and two lawsuits filed by Open Vallejo, the news organizations found a pattern of delayed and incomplete investigations, with dire consequences.

In the Foster case, when top department leadership ultimately reviewed reports and evidence more than a year and a half after Foster was killed, it found McMahon had violated department policies — both by pursuing Foster on foot without notifying the department and without backup and by failing to turn on his body camera before using deadly force. (While McMahon only turned on his body camera after he fired, the camera is designed to automatically capture 30 seconds of pre-activation footage.)

“Officer McMahon failed to recognize his safety and the safety of the suspect Ronnell Foster outweighed apprehension for a minor traffic/pedestrian violation,” then-police chief Joseph Allio wrote in a memorandum. Allio ordered that McMahon “attend a 1 to 3-day course on officer safety and tactics focusing on critical incidents.”

But by the time that training was ordered, the officer had been involved in the killing of another African-American man.

According to our first-of-its-kind review of Vallejo’s investigations of police killings, six of the department’s 17 fatal shootings between 2011 and 2020 involved an officer using deadly force while still under investigation for a prior killing. In three of those cases, including McMahon’s, department officials noted officers’ initial mistakes in their reports, but not until after their second killing. In all three, the investigation into the second killing also revealed significant tactical errors, like not considering the use of nonlethal weapons. In one case, officials identified the same mistake in two killings involving the same officer.

Investigations Into Police Killings Were Ongoing When the Same Officers Used Deadly Force Again

Vallejo's reviews of police killings have dragged on for years. Six times since 2011, the incident was still under review when the same officer was involved in another fatal encounter.

The news organizations also found that the department consistently failed to properly complete essential investigative tasks and took more than a year on average to close its administrative investigations of fatal shootings — methods that experts say are at odds with best practices promoted by the U.S. Department of Justice and used by police agencies around the country.

“This isn’t accepted practice. This isn’t even basement standard practice,” said Louis Dekmar, the police chief in LaGrange, Georgia, since 1995, and a former civil rights police monitor for the U.S. Department of Justice. “Any agency that takes that long is saying that this isn’t a priority.”

Officials in the Foster case mishandled a crucial piece of evidence, police records show, then took months to request that the crime lab analyze it for fingerprints. Nineteen months passed between the killing and the submission of investigative findings to the police chief. Only then was the chief able to fully assess the case and consider discipline for that shooting. McMahon later testified that he feared for his life and that Foster, holding the flashlight, faced him “in a boxer type stance.” But body camera footage does not support the officer’s claim that Foster was facing him, and an expert for Foster’s family who reviewed enhanced footage and other forensic evidence concluded that Foster had immediately turned away. McMahon remained on the job, and was later fired over his involvement in the killing of another man, during which, a department investigation found, he endangered a fellow officer by shooting from behind him. He did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

In a March phone call, Shawny Williams, Vallejo’s police chief since November 2019, agreed to an interview but declined to schedule it; after we shared our findings with the department in writing, he provided a statement that pointed to recent administrative changes, like implementing a yearly crisis intervention training and requiring officers to use de-escalation tactics when possible before engaging with a suspect. Williams also noted proposed reforms to how the department investigates its fatal shootings — some of which mirror recommendations first made to the department by a law enforcement consultant two years ago. Among them: a deadline for officials to produce their findings once all the evidence has been gathered.

Williams declined to answer questions about any specific cases.

“While I cannot comment on critical incidents which occurred prior to my arrival, or on ongoing matters, I can confirm that overall, the VPD continues the process of implementing police reforms,” the chief wrote. “All the above changes are designed to create enhanced internal accountability and will provide a more transparent process for our department and the community.”

“A Remarkable Amount of Incompetence”

While there is no universal timeline for internal investigations, guidelines developed for the Department of Justice by a group of local police officials say departments should, at minimum, complete their probes before any statute of limitations on officer discipline expires (one year, in California, with some exceptions). “It is preferable,” the group wrote, “to conclude investigations within 180 days.”

But in some of the DOJ’s own reviews of police departments across the country, it has pushed for even shorter deadlines when it comes to investigating an officer’s use of force, including fatal shootings.

In 2012, for example, the Justice Department mandated that the East Haven Police Department in Connecticut complete deadly force investigations within 60 days and forward a report to the chief, who has 45 days to complete the review. And in 2014, the DOJ required a similar deadline in Albuquerque for reviews of serious uses of force.

But in Vallejo, Open Vallejo and ProPublica found that the police department has taken an average of 20 months to review fatal shootings, from the time of a police killing to the date a chief signed off on the investigation.

A number of mistakes drove delays in Vallejo and undermined the integrity of investigations. One core problem: Some witnesses to killings reported long delays before officers took their statements.

That’s what happened in 2012, after Jaime Alvarado and his wife, Rocio Alvarado, said they witnessed Vallejo police shoot their neighbor Jeremiah Moore, a young man whose mother said he was on the autism spectrum.

Police had responded to 911 calls about loud noises coming from Moore’s home, including the sound of glass breaking. Although officers and an intoxicated witness later claimed Moore had been armed with a .22-caliber rifle, Jaime Alvarado said Moore was naked and unarmed, with his hands up and shaking from fright, when he was shot and killed by a Vallejo officer. (A forensic analysis could not find Moore’s fingerprints on the rifle, which was recovered in his home, while a later one found small traces of his blood on it.)

Alvarado said he tried to approach a Vallejo officer a few hours after he saw the killing through his second-floor window, but was told that “we don’t have time to talk” and to “get inside the house.” No one from the department tried to contact him after that, he said.

“They would not pay attention to me,” Alvarado told Open Vallejo and ProPublica.

According to Alvarado, detectives didn’t take his statement until several months later, after an attorney hired by Moore’s family to sue the city facilitated the interview. Yet there is no record of that interview in Vallejo’s case file, and the department ultimately cleared the officer in the killing. Neither the Moore family attorney nor the police department responded to questions about Alvarado’s account. The Moore family’s lawsuit was settled in 2016 for $250,000.

It was one of three investigations among the 17 killings in which Vallejo detectives interviewed one or more eyewitnesses months later or did not interview them at all, despite a county policy that states department officials are responsible for “immediately” securing crime scenes, including identifying and sequestering witnesses in order to obtain their statements. In each of these cases, the witnesses’ accounts directly contradicted claims by police that the victims had been armed.

But it was not the only type of delay. In 11 of the 17 cases, investigators did not meet a 30-day goal set by the county to complete their reports. Detectives often took even longer to request analysis on important evidence, such as bullets fired by officers, fingerprinting, DNA samples and weapons allegedly carried by the victims. In six investigations, Vallejo sent requests for evidence testing to a crime lab half a year or more following the killings. In most of those cases, the delayed analyses appear to have hampered the investigations or led to cases being closed by investigators before some forensic reports could be included.

In Foster’s case, detectives didn’t seek fingerprint testing of the flashlight that McMahon claimed Foster used as a weapon until eight months after the killing. When they finally made a request, the lab could not find Foster’s fingerprints. Experts say long delays can cause biological evidence to degrade.

“The consequences of delayed resolutions of investigations are severe,” the Justice Department wrote in its investigation of the Chicago Police Department in 2017, triggered after a white officer fatally shot Black teenager Laquan McDonald. “Memories fade, evidence is lost, and investigators may not be able to locate those crucial witnesses needed to determine whether misconduct has occurred.”

For years, the Solano County district attorney based their decisions about whether to charge Vallejo police officers primarily on evidence gathered by Vallejo officials. This made some of the detectives’ missteps especially meaningful. For example, in three of the killings from 2012, prosecutors cleared officers before all the evidence in the case had been analyzed by forensic experts.

“Either there is a remarkable amount of incompetence or it’s malicious,” said Seth Stoughton, a professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law and former Florida police officer, about the Vallejo Police Department. “Neither should be acceptable.” Stoughton testified as a national police standards expert for the prosecution in the trial of former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, who was convicted of the murder of George Floyd.

Williams, the Vallejo police chief, declined to answer specific questions about the numerous delays.

Solano County’s current district attorney, Krishna Abrams, who took office shortly after the officer involved in the Moore shooting was cleared, also declined to comment on the findings of this investigation.

However, Abrams wrote in a statement that her office has continued to make it a priority to use best practices for investigating officer-involved fatal incidents. She pointed to rule changes from 2020 that require that future investigations of Vallejo killings involve criminal investigators from other departments in the county. She did not comment, however, on another rule change made that year that removed a 30-day target for detectives to complete their reports.

While Investigations Drag, Officers Kill Again

As Vallejo’s investigations dragged on, sometimes for years, officers who had killed patrolled the city’s streets, their mistakes unaddressed. In three cases, department officials flagged officers’ actions only after they were involved in another killing, police records show.

Officer Sean Kenney killed Anton Barrett in May 2012. Kenney was still under investigation for that shooting when, on the morning of Sept. 2, 2012, he and his partner, Dustin Joseph, pulled up in front of the home of a man named Mario Romero. Romero, who identified as Black, Indigenous and Latino, was sitting in his parked Ford Thunderbird with his brother-in-law, police and court records show. The two white officers claimed that the young men seemed shocked to see them approaching and that Romero’s car was encroaching on the sidewalk, according to the officers’ depositions in a civil rights lawsuit filed by Romero’s family. Kenney also claimed that a similar vehicle had been involved in a shooting the prior month.

Within seconds and without exchanging a word, Kenney and Joseph exited their vehicle and started firing, according to Joseph’s deposition. Then, Kenney jumped on the hood of the Thunderbird, according to court and police records.

The officers fired 31 rounds in total, striking Romero, a father of one, 30 times in the face, neck, forearms, chest and left side of his body. His brother-in-law was hit once in the pelvis and survived. Officers pulled both men from the car after the shooting.

Joseph told detectives that Romero had briefly gotten out of the car and grabbed the butt of a gun in his waistband, though officials never found a firearm. Kenney claimed he recovered a pellet gun wedged between the rear portion of the driver’s seat and the center console. Two weeks after the incident, the officers were sent back to patrol. While police experts said many departments don’t prohibit this, they also said that having officers with open deadly force investigations go out on patrol can be dangerous for officers and community members alike.

It would take detectives another eight weeks to interview Romero’s three sisters, eyewitnesses in the case who contradicted the officers’ accounts. They said they never saw Romero with a firearm and that their brother remained inside the car during the incident.

Before those interviews happened, though, Kenney had killed again.

On Oct. 21, 2012, the day after Romero’s funeral, Kenney fatally shot Jeremiah Moore, the young man who Alvarado said was unarmed. It was Kenney’s third deadly incident that year.

The next year, on March 20, 2013, Joseph and two others were involved in the fatal shooting of 42-year-old William Heinze, who had barricaded himself in a house with a firearm during a mental health crisis. It was Joseph’s second deadly incident in just over six months.

In 2014, with investigations into those two killings pending, Joseph received a departmental Life-Saving Medal for a separate event and was promoted to corporal. Kenney, with three open deadly force investigations, was awarded the Medal of Valor for his role in the Moore shooting, according to Kenney’s deposition.

Roughly two years after the Romero shooting, the department’s Critical Incident Review Board finally issued findings in the administrative probe. The panel is supposed to evaluate whether officers’ use of force was justified.

In October 2014, it flagged the officers’ tactics during the incident. The board found that Kenney placed himself in a “tactically disadvantageous position with a potentially armed subject” when he jumped on the hood of Romero’s car, and noted officers could have waited at their car for backup, records show. Nevertheless, officials noted, “The board felt that the officers relied upon their past training to successfully endure this dangerous and rapidly evolving incident.”

It still recommended additional training, without specifying whether the training was intended for the two officers or the department as a whole. The board then failed to forward its own completed report to supervisors for nearly a year. During that time, the city settled the lawsuit for $2 million.

Yet another year would pass before then-Vallejo Police Chief Andrew Bidou assessed the case for disciplinary, training and policy considerations. Bidou approved the board’s findings, but he did not take further action in the case, the files show. By then, criminal accountability had been ruled out, too. The district attorney had declined to file charges three years earlier. His report noted that Vallejo investigators had interviewed Romero’s sisters long after the incident; the prosecutor suggested that the delay made their statements less credible than the officers’ accounts. He was also missing forensic analyses that would later show that the DNA and fingerprints taken from the pellet gun could not be matched to Romero.

“If that investigation had been run properly, Kenney would have been off the street and he wouldn’t have killed my son,” asserted Lisa Moore, the mother of Jeremiah Moore, Kenney’s third shooting victim, about Vallejo’s handling of the case. “Four years, that’s a long time to figure out ‘Oh, we messed up. What did we do wrong so that this doesn’t happen again?’”

Kenney retired from the Vallejo Police Department in 2018, after the board cleared him in the Moore shooting. He declined to comment for this story. As for Joseph, the Vallejo board ultimately flagged officers' tactics during his second deadly incident, and recommended training. Joseph, who did not respond to requests for comment, left Vallejo in 2019 to join the nearby Fairfield Police Department, where Fairfield officials said he is currently on leave.

“With This Delay There Is No Justice”

The review board’s actions in the Romero case were not an anomaly.

Made up of two to six ranked officers from within the Vallejo PD, the Critical Incident Review Board reviews an investigation, identifies whether officers violated any policies and makes recommendations to the chief, according to the department’s policy manuals. Our analysis of the 17 cases found those reviews were consistently delayed. In 11 cases, the panel sent its report up the chain of command more than one year after the incident. And in six of those cases, the board sat on its findings for months before forwarding them, delaying the review of the chief of police, who makes the final decision on discipline, according to the analysis by Open Vallejo and ProPublica. In two cases from 2011 and 2012, the department was unable to show that a final administrative review was completed.

The news organizations’ analysis found that the board often cleared officers even when it noted problems with how they had handled a shooting. In fact, the CIRB never determined that any officers had violated department policies, according to the department’s records. Often, it recommended training. But in at least a few of those cases, there is no evidence in training and investigative files that the involved officers completed it.

In two cases in which the chief considered potential discipline, he opened yet another investigation because the board’s probe was insufficient, creating additional delays. All these delays by both the CIRB and the chief matter in part because California law gives departments only one year to impose discipline once officials learn of an incident, though that timeline is paused during a criminal investigation. (That timeframe expired in one of the 17 killings that we reviewed.)

Experts said Vallejo’s approach is fundamentally flawed.

“That’s the whole purpose of having a disciplinary process in place: to assess quickly whether or not officers have engaged in misconduct, and if they’re a threat to the public, to get them removed from the department and off the streets,” said Judge LaDoris Hazzard Cordell, a former Superior Court judge for the County of Santa Clara. From 2010 to 2015, Cordell served as the independent police auditor for the city of San Jose, which created the office in 1993 following the beating of Rodney King by the Los Angeles Police Department.

“What is happening in Vallejo is quite the opposite: It's just delay, delay. And with this delay there is no justice,” Cordell said.

Over and over, the board seemed to miss opportunities to help the department fix practices that contributed to those killings. Despite delays, the CIRB did, in fact, note plenty of problems: officers who didn’t turn on their body cameras, failed to use less lethal options, mismanaged crime scenes or did not wait for backup. But, time and again, the board reports neither called out individual officers for problematic behavior nor recommended policy changes as a result of the failures they repeatedly identified.

The most common problem identified by the CIRB in its reviews of killings was that officers acted without sufficient “cover,” meaning they didn’t properly use structures like cars for protection when confronting civilians, amplifying the risk to themselves and others in already-dangerous situations. When officers don’t take cover, “they put themselves in jeopardy — they create jeopardy,” said Dekmar, the former civil rights police monitor for the U.S. Department of Justice. “That results in a use of force that may have been avoided.” Investigators noted cover issues in six of Vallejo’s 17 killings since 2011.

It first surfaced in the 2012 case of Marshall Tobin, a 43-year-old Black man who was sitting in his car sobbing over his phone when two officers, both under deadly force investigations for prior killings, approached him. Police had received a call about an armed man in a parking lot. After Tobin emerged from his car, officers tased him and then fired at least 11 rounds at him, killing him. The officers told investigators that after he was tased, Tobin had reached for a gun in his waistband. They did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

A year and a half later, the CIRB found in its review that the officers had approached Tobin on foot, “leaving the cover and concealment of the vehicles.” It recommended additional department training in how to use cover, but it did not officially flag the officers’ behavior or find that they had violated a policy. (Two months after that, one of those two officers, from inside his patrol car, shot at a Latino man fleeing a traffic stop — the officer’s third fatal incident in two years. The board approved of the shooting, and the chief cleared him.)

At some point after the Tobin killing, then-police chief Joseph Kreins, who reviewed seven fatal shootings between 2012 and 2014, did add a clause to the policy manual that “encouraged” officers on vehicle pursuits to “remember the importance of cover, concealment, and safe distance.” But in 2015, despite the board’s findings in the Romero and Tobin shootings, the next chief of police, Andrew Bidou, removed it. Neither Kreins nor Bidou responded to requests for comment.

The issue emerged again in 2017, when officers killed Jeffrey Barboa, a father of one who police said was wanted for an armed robbery. Following a high-speed pursuit that ended in a crash, Barboa had approached officers while holding a knife over his head. The officers, standing within 15 feet, did not step back, police records show. As Barboa slowly walked toward the officers, they fired approximately 50 rounds at him, hitting him at least 30 times in the chest, face, neck, arms and legs.

More than 28 months after that shooting, in December 2019, the CIRB found in its report that had the officers taken cover or put more distance between themselves and Barboa, they would have created time to communicate with him and “deploy less-lethal alternatives.” “It is this positioning that likely caused the situation to speed up,” the board wrote.

Nevertheless, the review board responded as it usually did: It identified no policy violation or specific officer at fault and issued a list of training recommendations with no accompanying plan to implement them. There is no evidence in the department’s reports that Vallejo officials took further action in the case.

Multiple reports were made to organizations and institutions responsible for the welfare and protecting athletes regarding a former University of Toledo soccer coach, yet the reports were either not considered, not investigated, or received no response. (photo: Franck Fife/Getty)

Multiple reports were made to organizations and institutions responsible for the welfare and protecting athletes regarding a former University of Toledo soccer coach, yet the reports were either not considered, not investigated, or received no response. (photo: Franck Fife/Getty)

In the second part of an exclusive investigation, the Guardian can reveal that multiple organizations and institutions tasked with the welfare and protection of athletes failed to consider, investigate or address repeated allegations of sexual misconduct against Toledo soccer coach Brad Evans

The university took five years to acknowledge the sexual misconduct allegation – only after the current coach of the University of Toledo women’s team filed a report to the school’s Title IX office in 2020. The reported victim of the alleged sexual misconduct was Candice Fabry, a former student, athlete and assistant coach at the university, as exclusively reported by the Guardian.

In a 2020 letter to Fabry informing her of the 2020 report, the university’s Director of Title IX and Compliance Vicky Kulicke wrote: “The Title IX office is aware that this was reported also to the University of Toledo’s Human Resources in 2015 and addressed at that time.” The 2020 report was made to the university by the women’s soccer team’s current coach Thomas Buchholz-Clarke, who succeeded Brad Evans after his 2015 resignation.

The reported allegation was against Evans, head coach of the women’s soccer program at the University of Toledo from 2001 to 2015. Evans’ 13-season reign at Toledo saw the team bring home four Mid-American Conference tournament titles in the NCAA’s top-flight Division I.

As the Guardian has exclusively reported, that success came at a high price for some former players and staff. The true story behind Evans’ sudden resignation from the University of Toledo women’s soccer program in 2015 was never fully explained while the coach pursued a successful career elsewhere after quietly leaving the Toledo program.

Over a three-month period the Guardian has spoken with former players, coaches, University of Toledo staff, and families of former University of Toledo students, to be able to reveal for the first time allegations of sexual assault and sexual coercion, a hostile environment for players, how the university managed reports about his behavior, and how a lack of transparency by the university allowed Evans to still hold prominent positions within the sport in the US with little accountability.

On Wednesday, following the Guardian’s report of Evans’ alleged sexual misconduct, the United States Soccer Federation suspended his coaching license.

The 2020 Kulicke letter sent to Fabry acknowledges that the University of Toledo knew about allegations of sexual misconduct in 2015 but did not adequately address them at the time. Instead of pursuing the sexual misconduct claim, the university investigated Evans for “verbal harassment” following an allegation from an undisclosed source. Still, the university stopped short of disciplinary action against Evans when he abruptly resigned for what he described as “inappropriate relationships”.

In an emailed statement to The Guardian, the University said:

UToledo did conduct an investigation following a report by a student-athlete in January 2015 of verbal harassment by Brad Evans, who was at the time the Head Coach of the women’s soccer team. The investigation did find that Mr. Evans’ conduct toward student-athletes may have violated the University’s Standards of Conduct policy, however, the case was not referred for possible disciplinary action because by the conclusion of the investigation in March 2015, Mr. Evans had already resigned his position effective Feb. 23, 2015.

In a follow-up email to the Guardian, the university did not respond to specific questions about previous allegations made by athletes and families and said there were “no additional reports” relating to alleged misconduct by Evans.

“I was contacted by Human Resources and met with an investigator and a university lawyer,” recalls Marley Merritt*, a former University of Toledo staff member who said she felt pressured into entering a sexual relationship with Evans, about the 2015 investigation into Evans alleged misconduct.

“I remember leaving the interview and thinking they never got the full story. They never asked the right questions. I felt they just checked the box to say that they did an interview. I went back to them and requested a second meeting. I had more information to tell them. They just weren’t asking. At the second meeting there was just an investigator. I had dates and exact details and was ready to talk about it but they never asked specific questions.”

The 2015 investigation was not the first time the university had received reports about the behavior of Brad Evans, either. In late 2012, after four years on the University of Toledo’s soccer team, Rachael Kravitz and her younger sister Heather – who was also briefly part of the soccer program – called a meeting with university administration. The two women were accompanied by their parents, Roger and Cindy, and presented years of documented notes detailing what they described as “abusive behavior” within the University of Toledo women’s soccer program.

“I realized I don’t have the love for soccer that I used to have,” Rachael Kravitz, who graduated in 2013, says today. “I tried to play soccer after my college career and I lasted maybe an indoor season. I was still mad at it. Toledo was disgusting to me. I can’t wear a Toledo soccer shirt. When my husband wears Toledo stuff, I’m like uggghhh. I have no interest in doing any alumni-related activities. I have other things in my life right now.”

During her time at the university, Kravitz kept a notebook detailing meetings with soccer program staff, comments made to her and other players at training sessions, and incidents that occurred at training and games. Her parents did the same. They are careful to note that there was no one specific dramatic incident they identify as a red flag. Instead, they have a catalog of long-standing behavior resulting in an oppressive and toxic environment.

“The behaviors allowed other people think it was OK to treat people in a certain way,” Rachael Kravitz says. “A couple of people mentioned to me that he would say things about my breasts. He didn’t say it in front of me but it eventually got back to me.”

According to a former University of Toledo player under Evans who also worked as an assistant coach on the program after graduation, the longtime coach set what he considered to be “high standards” for the team.

“He was strong on ‘team first’,” says Jennifer Whipple, a starting goalkeeper for Toledo from 2003 to 2006 before spending three years as an assistant coach with the team.

“In meetings there was yelling, people were made to cry, players were [considered] selfish or weren’t good teammates,” Whipple tells the Guardian. “These were stories I heard often from teammates and that I witnessed as a coach. As a player this never happened to me, though. [Brad] seemed to like drama. He even told me after the 2008 season that he needed to create some tension so people didn’t get too comfortable. He said he couldn’t stand things being calm for long.”

“He called in two players who he wondered if they were in a romantic relationship,” Whipple adds. “When they came in they looked confused and he said ‘I heard that this is going on’. There was always this idea that you were being watched by someone.”

The Kravitz family meeting in November 2012 included Dr Kay Patten-Wallace, the University of Toledo’s senior vice-president of student affairs, and Kelly Andrews, the senior associate athletic director. Rachael, Heather and her parents brought documentation to the office of Patten-Wallace and described events that had taken place within the program that they were concerned about. Roger Kravitz recalls Kelly Andrews countering that the university had received glowing reports of Brad Evans.

“I can show you a box full of them,” Roger Kravitz recalls Andrews saying. “Why are your kids still here? Why don’t they leave if it is that bad?”

Cindy responded: “Because they have done nothing wrong”.

“I walked away from the meeting thinking nothing is going to happen from this,” recalls Roger Kravitz.

Cindy tried to be optimistic: “We thought that if we can help just one other person from being abused then it will be worth it. We hoped something would trigger change but we didn’t expect it.”

An assistant coach – speaking to the Guardian on condition of anonymity for fear of personal and professional repercussions – recalls meeting Kelly Andrews in 2014 and detailing a list of observations about Evans’ behavior and the team environment.

“I said ‘You are sitting on a timebomb’,” the assistant coach recalls. “That is when she said to me [that she has] all these letters from all these parents and players saying what a wonderful experience they had with the University of Toledo soccer program under Brad.”

A year later, in 2015, Brad Evans resigned from his 14-season stint leading the University of Toledo women’s soccer program. In a statement to the Guardian, Evans said:

In 2015 I was asked to answer questions about my relationships with some past co-workers. It was clear that my interactions with those co-workers demonstrated poor judgment on my part, and were against university policy, and resigning was best for all involved.

With the help of counseling, I have learned a lot about the causes of my behavior. I am extremely lucky to have the support of my wife in this process. Together, I continue to learn to become a better person.

I am deeply sorry to have disappointed so many individuals, but I continue to work on making a positive future.

Thank you for the opportunity to provide my perspective.

“I was there when he informed the team,” recalls Marley Merritt, a former member of the university staff. “The team was not expecting it. It was a surprise. Kelly Andrews and the assistant coaches [were there]. It was right before a practice. Brad Evans walked in, was able to tell the team and control the narrative that he resigned because of inappropriate relationships. It was ridiculous. It gave him all the power.”

Recalls an assistant coach: “We were happy that he was going to be out of coaching because [a news story] said he was going to go work for his mom.” The Toledo Blade also reported claims by Evans he was not forced out and was ending his coaching career. Evans, however, was not done. Soon, he would return to coaching with Ohio Youth Soccer Association North and a top local youth club.

In 2017, the Ohio Youth Soccer Association North, Evans’s latest employer (Ohio North and Ohio South merged in 2020 to create the Ohio Soccer Association), received a copy of a report sent to the University of Toledo in 2015 by Candice Fabry. The report alleged she had been sexually assaulted by Evans in 2007. At the time of the 2007 alleged assault, Fabry was in transition from student-athlete at the University of Toledo to an assistant coach with the women’s soccer program led by Evans.

Prior to the Ohio Youth Soccer Association North receiving the Toledo report, Fabry had detailed her experience to the association’s president Paul Emhoff and executive director Jen Fickett. Emhoff’s reaction, according to Fabry, was that “Brad seems like such a nice guy” and that an “article said he resigned from Toledo for an inappropriate relationship”.

In 2020, Ohio North and South soccer associations merged to become the Ohio Soccer Association. Under the new administration Brad Evans became head of coaching education and head coach for the state’s Olympic Development Program, positions he still holds. Jen Fickett is now the Ohio Soccer Association’s Safe Soccer Director. Ohio Soccer Association did not respond to multiple requests for comment on issues raised by the Guardian’s reporting.

In 2019, Candice Fabry reported her experiences to SafeSport, a non-profit organization that emerged from the 2017 Protecting Young Victims from Sexual Abuse and Safe Sport Authorization Act of 2017. The organization bills itself as having exclusive authority to investigate and resolve allegations of sexual misconduct in Olympic and Paralympic sport. After two telephone conversations with representatives from SafeSport, Fabry never heard from the organization again.

The common pattern in this story, besides the allegations against Evans from multiple individuals? Multiple reports were made to organizations and institutions responsible for the welfare and protecting athletes. Yet the reports were either not considered, not investigated, or received no response.

“It’s supposed to be the best years of your life,” says Cindy Kravitz, the mother of Rachael and Heather, soccer players who reported their concerns to the university. “What was mind-boggling to us was how the team was winning. They were broken and beaten. Knowing some of the stuff going on behind the scenes, how could they even get out of bed in the morning?

Adds father Roger Kravitz: “At what point is your child at risk for hurting herself? That was always at the back of our minds.”

Three words perhaps sum up the experience of Candice Fabry. She pauses and smiles before saying them. It’s not, however, a happy smile. It’s a smile of someone who is tired – yet persistent.

“I told them,” says Fabry.

The prime minister who spent his career using lies and deflection to wriggle out of scandal has finally found a crisis entirely of his own making that he couldn't survive. (photo: Leon Neal)

The prime minister who spent his career using lies and deflection to wriggle out of scandal has finally found a crisis entirely of his own making that he couldn't survive. (photo: Leon Neal)

The prime minister who spent his career using lies and deflection to wriggle out of scandal has finally found a crisis entirely of his own making that he couldn’t survive.

He was savaged by his own ministers who dramatically quit his government in a record-breaking tsunami of disgust.

They couldn’t take any more of his bare-faced lies.

Johnson likes to think of himself as a British history buff. Obsessed with Winston Churchill, he had perhaps fantasized about leading a country through a generation-defining crisis more often than anyone. He may have thought his call of duty was to see through the Brexit project—one which he officially completed in 2020 but that mess continues to unravel. His handling of the COVID crisis will forever be overshadowed by his attempts to cover up a string of parties held inside Downing Street while the rest of the country was locked down.

Johnson will announce his resignation Friday, but he will hope to limp on as PM until a replacement is chosen by the Conservative Party in October.

He will go down in history as one of Britain’s worst prime ministers, with a record-eviscerating 55 ministerial resignations from his government in 48 hours.

The 58-year-old became one of Britain’s most high-profile politicians long before he held any real power. His controversial journalism career, followed by his appearances on television panel game shows during his early years in politics, saw him become a household name. Johnson’s bumbling, clownish persona and ramshackle appearance made it easy for him to stick out from the dusty gray relics who sat next to him on the benches of Parliament.

But it was always just a persona. Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson, born in New York in 1964, was bred for power and ruthlessly clung to it until the day that he was finally forced out. His great-grandfather Ali Kemal was an interior minister in the Ottoman Empire. His father, Stanley, was a diplomat and member of the European Parliament. Johnson was educated at Eton College—the illustrious school that’s pumped out 20 prime ministers over the centuries.

He went from Eton to study at Oxford University, where, already highly skilled in the art of making people pay attention to him, he was voted in as president of the Union. Soon after graduating, in 1987, he arrived on the national stage as a young journalist—but not for the right reasons. He was very publicly fired from The Times of London within months of starting for completely making up a quote on his very first front-page story. It was the first, but certainly not the last time Johnson brazenly attempted to mislead the British public.

Had he been less determined—or not as well-connected—that could well have been the end of his career. As it happened, after a brief penance at some local newspapers, he joined the conservative Daily Telegraph as its Brussels correspondent, where he virtually invented the brand of brash “Euroscepticism” that he would use decades later to persuade voters to leave the European Union. Far from being a fatal weakness, his ability to stretch the truth and then package it into a memorable turn of phrase became the very basis of his success.

From there, on the strength of his outwardly affable persona and increasing notoriety in journalism, he stood for and was elected to Parliament in 2001. He stayed for seven years until, in 2008, he spotted an even better opportunity to increase his public profile. He was elected mayor of London and was re-elected again in 2012. During his time, he was able to showcase his ability to deal with a crisis when a series of violent riots erupted in the city in 2011, and he triumphantly oversaw the successful 2012 Summer Olympics a year later.

His time in London’s City Hall was seen as a success, although his former colleagues later told The Daily Beast that was largely in spite of Johnson, who they described as an incredibly lazy man who doesn’t care about detail and would frequently just make things up.

Nevertheless, in 2015, Johnson announced that he wanted to return to Parliament and, now that he was armed with some leadership experience, it was clear to everyone that he was there to fulfill his long-held dream of becoming prime minister. The incumbent leader, David Cameron, had been Johnson’s rival for decades. They attended Eton and Oxford together, and Johnson seethed as the slightly younger Cameron rose above the wannabe-world-king in power. In 2016, ahead of the Brexit referendum, the schoolboy rivalry erupted into public view.

Johnson’s decision to join and then lead the campaign for Britain to leave the EU—against the prime minister’s campaign to remain—was not a matter of principle but a calculated gamble to enhance his chances of power. He knew that, even if he lost, it would only be after a lot of invaluable TV news coverage that showed him as a leader. Famously, Johnson wrote two columns on the weekend he announced his decision. One put forward his case to remain, and the other put forward his case to leave. He decided to publish the Leave column.

The gamble paid off. The Leave campaign won a shock victory and Johnson became the public face of a campaign that clearly resonated with a slim majority of voters in Britain. It wasn’t an ethical or truthful campaign—its central message was to take back control of a mythical £350 million that Johnson falsely claimed the U.K. sent to the EU every week. It also published misleading dog-whistle warnings about 76 million people from Muslim-majority Turkey flooding into Britain through the EU.

But Johnson won, Cameron resigned, and only a separate rivalry with his fellow Leave campaigner Michael Gove—who stood for leader alongside Johnson to divide the vote and stop him from winning—prevented Johnson from becoming PM three years before his eventual rise to the top job.

The winner of that leadership contest, Theresa May, appointed him as foreign secretary—Britain’s most senior diplomat. Having just fallen short of becoming prime minister, Johnson seemed uninterested in the role and his time was predictably marred by a series of high-profile errors. One of his junior ministers later recalled that clearing Johnson’s mistakes was a “full-time activity” and said he became known in other countries as Johnson’s “pooper scooper” because he was forced to clear up his mess so many times.

Johnson quit as foreign secretary in July 2018, claiming in his resignation letter that the U.K. was headed “for the status of a colony” if May’s Brexit plans were adopted—plans that were largely similar to the ones he would eventually use to leave the EU in 2020. Nevertheless, his resignation freed him from the restrictions of government and allowed him to wait for May to fail—or, rather, act as a quiet catalyst for that outcome in the background—so he could step in and save the day when the Brexit project faltered.

That day finally came in 2019, when May’s Brexit deal was repeatedly rejected by Parliament and she resigned. He stood and was voted in as Conservative leader and, as leader of the largest party, he was also automatically installed as prime minister. Soon afterward, he called a general election in December 2019 and his blunt message to “get Brexit done” was endorsed by voters who gave him a landslide victory. He led Britain out of the EU in January 2020.

Having already achieved his central campaign promise a month into his new government, Johnson was set to start work on creating the rest of his legacy when reports about a new virus started seeping out of China.

Johnson’s initial response was—in fitting with the rest of his career—light-hearted and controversial. Earlier in March, as other countries were deploying powerful counter pandemic measures, Johnson paid a visit to a hospital that was treating virus patients and later boasted to reporters that he shook everyone’s hand there. Britain also initially pursued a policy of allowing the disease to spread, relatively untested and unchecked, in an apparent departure from the approaches taken across the rest of the world.

However, the policy changed when a bombshell report on the likely catastrophic impact of coronavirus stiffened policy in London. Johnson switched from being relatively flippant about the disease to taking on a starker tone with the public. He settled into the role of quasi-wartime prime minister until April of that year, when he nearly died from the virus, but then he recovered to lead the nation through the pandemic for the rest of 2020 and 2021.

Up until much more recently, it didn’t seem as if Johnson had a terrible pandemic. Cases and death rates were, broadly speaking, in line with similarly sized European nations, and Britain had one of the fastest and most successful vaccine rollouts on the planet. That was followed up by a similarly rapid booster rollout as the Omicron variant threatened to disrupt Christmas last December.

But people didn’t know until late last year that, while they were living in solitude and mourning loved ones in 2020 and 2021, Johnson was partying. A deluge of reports exposed the high jinks that were going on in 10 Downing Street while the rest of Britain was living through one of its grimmest national moments. They included a boozy party the night before Queen Elizabeth II sat distanced from her family at Prince Philip’s funeral, as well as a surprise birthday bash for Johnson in June 2020 where people enjoyed cake and finger foods.

As more and more lockdown-busting parties were exposed, many of Johnson’s supporters in his Conservative Party abandoned him, and those who didn’t found it increasingly difficult to publicly defend his ridiculous actions. One of his lawmakers, asked why the prime minister thought it was a good idea to attend a birthday party while the rest of the nation was strictly locked down, claimed with a straight face that Johnson was “ambushed by a cake.”

Johnson managed to survive the immediate fallout from Partygate, but his authority was fatally undermined.

Ministers who were sent out to lie for the prime minister over the parties refused to do so again when a new scandal hit No. 10 this week. It wasn’t the revelation that Johnson had employed a man with a history of sexual-harassment allegations to his name that forced a revolt from within his own ranks; it was the ever-changing set of excuses that did for him. They evolved each day, once the previous position had been exposed as another lie.

Sajid Javid, the health secretary, was the first to quit, and he explained to the House of Commons on Wednesday that he had been stung by previous untruths peddled by Johnson’s team. He said assurances were given to him personally by No. 10 that there was no truth to the party allegations before he did media interviews defending the PM. Those assurances turned out to be lies.

Javid said he had given Downing Street the benefit of the doubt on that occasion but would not be making the same mistake this time. “And now this week again, we have reason to question the truth and integrity of what we’ve all been told. And at some point, we have to conclude that enough is enough,” he said.

Too many lawmakers in Johnson’s party were no longer willing to tarnish their own reputations by defending the indefensible.

Johnson arrived in office hoping to emulate his hero Winston Churchill, and he was even handed an unprecedented global crisis to test his mettle. He failed to rise to the challenge and leaves his office as a disgraced liar and a punchline. For anyone who watched him bullshit his way to power, the only surprise is that, this time, it actually had consequences.

Virgilio Trujillo Arana, a 38-year-old Indigenous Uwottuja man and defender of the Venezuelan Amazon, was shot dead on 30 June. (photo: Getty)

Virgilio Trujillo Arana, a 38-year-old Indigenous Uwottuja man and defender of the Venezuelan Amazon, was shot dead on 30 June. (photo: Getty)

“Whatever happens, happens,” he said, in a video recorded before his death. “[But] without land, we disappear. That’s why we defend our territories.”

Trujillo, 38, served as the coordinator of the Indigenous Territorial Guard in the Autana municipality, in the state of Amazonas in southern Venezuela. He was also the founder of Ayose Huyunami, a unit defending Indigenous lands from criminal groups and illegal mining.

On Thursday, he was shot dead in the city of Puerto Ayacucho by a gunman who opened fire in broad daylight.

His murder has left his family and the Uwottuja community fearful and infuriated. Many of those who knew him asked not to be named out of concern for their own safety.

“It’s the first time I have suffered such a great loss … [Trujillo] – may he rest in peace – was the one who took the first step to defend our home,” said a family member.

Trujillo’s murder has been perceived by human rights defenders as an attack not just on one individual, but against an entire community and its efforts to protect a way of life.

On the night of his killing, other members of the Indigenous guard received death threats, and one member said that the murder had had a catastrophic impact on morale.

“Right now, I’m devastated and I feel incapable of fighting,” the guard said. “We’ve seen the price for this fight, and it’s very painful. Time may be running out for us. As frontline defenders, we’re all being threatened.”

But Trujillo and the Indigenous guards’ mission seems more important than ever.

In 2016 Venezuela’s leader, Nicolás Maduro, designated an area larger than Portugal as a strategic development zone for the exploitation of gold and other precious minerals.

Amazonas state is not part of this area, known as the Orinoco Mining Arc, and mining has been prohibited there since 1989. But the prohibition has not stopped mafia gangs and Colombian rebel groups from digging gold in the jungle – bringing violence, crime and environmental destruction with them.

Trujillo’s death came amid a wave of threats and violence against rainforest defenders across the Amazon. Last month, the Brazilian Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips were murdered in the Brazilian Amazon and activists have faced intimidation and violence in Ecuador, Peru and Colombia.

In Venezuela alone, 32 Indigenous and environmental leaders have been killed over the past eight years, according to the Odevida human rights organization.

“Virgilio Trujillo was not any Indigenous man. He was the defender of the Amazon,” said Armando Obdola, director of the Indigenous organization Kapé Kapé.

His death sits at the centre of a network of interlinked crises, said Tamara Taraciuk, acting director of Human Rights Watch’s Americas division.

Related: Venezuela’s gold fever fuels gangs and insecurity: ‘There will be anarchy’

“Virgilio’s death exposes some of the most difficult human rights challenges facing Venezuela today: the brutal control that armed groups exercise over illegal mining in the country; the struggle of Indigenous groups, who have been largely forgotten by authorities; and the uselessness of Venezuela’s judiciary to investigate abuses independently and hold those responsible accountable,” she said.

After the murder and the death threats, most members of the Indigenous guard were too afraid to show up at Trujillo’s funeral – and they have all avoided speaking out publicly about what happened.

“We’re entering a situation of passivity and fear,” says Obdola. “But this should be a moment of awakening.”

Trujillo’s family has called for a full investigation, but some blame Venezuelan authorities for his death. Virgilio had previously worked alongside units of the country’s army to protect Indigenous lands. After a string of death threats, he had applied to the interior ministry for protective measures more than a year ago, but his requests went unanswered.

“Unfortunately, the government system and these armed groups formed an alliance,” said a family member. “Instead of protecting the land, they engaged in corruption and smuggling.”

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.