Need to Pull a Rabbit From the Hat Today

We are down but not out. As bad as it looks right now, we absolutely positively can do this if we get on a roll.

The key is “you,” not someone else.

Donate folks, we are running out of time.

Marc Ash

Founder, Reader Supported News

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Long before Republicans nominated Donald Trump for president, let alone before Trump refused to acknowledge electoral defeat, the congressional scholars Thomas Mann and Norman Ornstein declared that the party had become “an insurgent outlier” that rejected “facts, evidence and science” and didn’t accept the legitimacy of political opposition.

In 2019 an international survey of experts rated parties around the world on their commitment to basic democratic principles and minority rights. The G.O.P., it turns out, looks nothing like center-right parties in other Western countries. What it resembles, instead, are authoritarian parties like Hungary’s Fidesz or Turkey’s A.K.P.

Such analyses have frequently been dismissed as over the top and alarmist. Even now, with Republicans expressing open admiration for Viktor Orban’s one-party rule, I encounter people insisting that the G.O.P. isn’t comparable to Fidesz. (Why not? Republicans have been gerrymandering state legislatures to lock in control no matter how badly they lose the popular vote, which is right out of Orban’s playbook.) Yet as Edward Luce of The Financial Times recently pointed out, “at every juncture over last 20 years the America ‘alarmists’ have been right.”

And over the past few days we’ve received even more reminders of just how extreme Republicans have become. The Jan. 6 hearings have been establishing, in damning detail, that the attack on the Capitol was part of a broader scheme to overturn the election, directed from the top. A Republican-stuffed Supreme Court has been handing down nakedly partisan rulings on abortion and gun control. And there may be more shocks to come — keep your eyes on what the court is likely to do to the government’s ability to protect the environment.

The question that has been bothering me — aside from the question of whether American democracy will survive — is why. Where is this extremism coming from?

Comparisons with the rise of fascism in Europe between the wars are inevitable but not all that helpful. For one thing, bad as he was, Trump wasn’t another Hitler or even another Mussolini. True, Republicans like Marco Rubio routinely call Democrats — who are basically standard social democrats — Marxists, and it’s tempting to match their hyperbole. The reality, however, is bad enough to not need exaggeration.

And there’s another problem with comparisons to the rise of fascism. Right-wing extremism in interwar Europe arose from the rubble of national catastrophes: defeat in World War I — or, in the case of Italy, Pyrrhic victory that felt like defeat; hyperinflation; depression.

Nothing like that has happened here. Yes, we had a severe financial crisis in 2008, followed by a sluggish recovery. Yes, we’ve been seeing regional economic divergence, with some ugly consequences — unemployment, social decline, even suicides and addiction — in the regions left behind. But America has been through much worse in the past, without seeing one of its major parties turn its back on democracy.

Also, the Republican turn toward extremism began during the 1990s. Many people, I believe, have forgotten the political craziness of the Clinton years — the witch hunts and wild conspiracy theories (Hillary murdered Vince Foster!), the attempts to blackmail Bill Clinton into policy concessions by shutting down the government, and more. And all of this was happening during what were widely regarded as good years, with most Americans believing that the country was on the right track.

It’s a puzzle. I’ve been spending a lot of time lately looking for historical precursors — cases in which right-wing extremism rose even in the face of peace and prosperity. And I think I’ve found one: the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.

It’s important to realize that while this organization took the name of the post-Civil War group, it was actually a new movement — a white nationalist movement to be sure, but far more widely accepted, and less of a pure terrorist organization. And it reached the height of its power — it effectively controlled several states — amid peace and an economic boom.

What was this new K.K.K. about? I’ve been reading Linda Gordon’s “The Second Coming of the K.K.K.: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition,” which portrays a “politics of resentment” driven by the backlash of white, rural and small-town Americans against a changing nation. The K.K.K. hated immigrants and “urban elites”; it was characterized by “suspicion of science” and “a larger anti-intellectualism.” Sound familiar?

OK, the modern G.O.P. isn’t as bad as the second K.K.K. But Republican extremism clearly draws much of its energy from the same sources.

And because G.O.P. extremism is fed by resentment against the very things that, as I see it, truly make America great — our diversity, our tolerance for difference — it cannot be appeased or compromised with. It can only be defeated.

Cassidy Hutchinson, a top former aide to Trump White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, is seen in a video of her interview with the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol on June 23. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Cassidy Hutchinson, a top former aide to Trump White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, is seen in a video of her interview with the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol on June 23. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Today Hutchinson, who had been an aide to former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows, will appear as the panel's surprise live witness for an unscheduled hearing, NPR has confirmed. The committee announced Monday that it would hold a hearing Tuesday "to present recently obtained evidence and receive witness testimony," but as of Tuesday morning it had not formally announced any witnesses or provided other details. To watch a livestream of the hearing starting at 1 p.m., click here.

The secrecy surrounding the hearing appears out of place; Hutchinson's cooperation with the committee has been an open, public fact.

Given the urgency of the hearing and the major pieces of information Hutchinson has already shared with the Democrat-led committee, expectations are growing that this former top Republican staffer will reveal something explosive when she sits down to testify.

What Hutchinson has said so far

Last week the former Meadows aide said in that video testimony that GOP Rep. Matt Gaetz had been asking for a pardon since "early December," and noted that Reps. Andy Biggs, Louie Gohmert, Mo Brooks and Scott Perry also sought pardons from the White House. John McEntee, a former White House aide, also said Gaetz had told him he asked Meadows for a pardon.

Hutchinson also testified she had heard that Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia had requested a pardon from the White House counsel's office. All of the members mentioned by name later denied the allegations.

The committee has shared video of two instances of her speaking about what the White House did leading up to, during, and after the violent attack on the Capitol. Earlier this month, some in Washington had posited she would testify at one of the committee's public hearings live.

Hutchinson previously testified that Meadows had been warned of "intel reports saying that there could potentially be violence on the 6th." She also told the committee that Meadows burned documents in his office after a meeting with Rep. Scott Perry, Politico reported, though it is not known what those documents were. During last week's committee hearings, Perry emerged as a key figure in former President Donald Trump's attempts to convince followers of a variety of lies about the soundness of the 2020 election.

Hutchinson has previously told the committee that she was around Meadows for a portion of Jan. 6, though not all of the events. She has also appeared in recorded testimony that former Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani, several of his associates and Meadows attended a meeting where they discussed having alternate electors in key swing states where Trump lost.

Politico also previously reported that Hutchinson has made a recent switch in legal counsel from Stefan Passantino, who reportedly still has close ties to Trump, to Jody Hunt of Alston Bird. Hunt is a former Justice Department attorney with close ties to former Attorney General Jeff Sessions.

A police officer holds one of a group of men, among 31 arrested for conspiracy to riot and affiliated with the white nationalist group Patriot Front, after they were found in the rear of a U Haul van in the vicinity of a North Idaho Pride Alliance LGBTQ+ event in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, U.S., June 11, 2022. (photo: John Rudoff/Reuters/Alamy)

A police officer holds one of a group of men, among 31 arrested for conspiracy to riot and affiliated with the white nationalist group Patriot Front, after they were found in the rear of a U Haul van in the vicinity of a North Idaho Pride Alliance LGBTQ+ event in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, U.S., June 11, 2022. (photo: John Rudoff/Reuters/Alamy)

The recent arrest of 31 fascists seemed to come out of nowhere. Newly-released documents show agents from the Bureau on the lookout for a long time

New documents show how Idaho cops and FBI agents were tracking white nationalists from Patriot Front months before the group was arrested this month for allegedly conspiring to attack a local LGBT Pride event in Coeur d’Alene.

Emails obtained through records requests by Property of the People, a Washington, DC-based transparency nonprofit, demonstrate that FBI agents in the area both reported and were updated on Patriot Front-related acts of vandalism as far back as August 2021. Those agents also helped Coeur d’Alene police prepare for Patriot Front’s alleged conspiracy to riot at a June Pride event, when local law enforcement arrested 31 members of the group.

The documents also show how conservatives’ Qanon-style rhetoric casting LGBT people as “groomers” and “pedophiles” has animated the far-right and shaped its targeting. Emails from city and law enforcement officials show threats against Coeur d’Alene’s LGBT groups came from a wider array of far-right groups than just Patriot Front.

“The rising fascist menace is a clear and present danger to what remains of American

Democracy,” Ryan Shapiro — executive director of Property of the People, which obtained the documents — told Rolling Stone.

Patriot Front was formed by founder Thomas Rousseau amidst from the infighting following the infamous 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, VA, where a white nationalist murdered counter-protestor Heather Heyer. Since then, an Anti-Defamation League primer says, “Patriot Front has been responsible for the vast majority of white supremacist propaganda distributed in the United States.”

Over the past two years, the group gained notoriety through a series of alternately menacing and clumsy flash marches in cities around the U.S., where members of the group wear matching outfits and travel in U-Haul storage vehicles while bearing homemade melee gear and masks to conceal their identities.

That’s what Rousseau had allegedly planned to do on June 11 during a North Idaho Pride Alliance (NIPA) when police there arrested him and 30 other members of the group for conspiracy to riot after an anonymous tipster warned the group had assembled “a little army.”

For at least a year before the arrests, FBI agents in the area were aware of the Patriot Front’s activities in Coeur d’Alene, according to emails from city officials and law enforcement.

In August of 2021, residents of the Coeur d’Alene metropolitan area began complaining about the appearance of Patriot Front propaganda posters around the city, prompting Coeur d’Alene Mayor Steve Widmyer to ask police to investigate.

“We need to catch these people. Disgusting,” Widmyer wrote in one August 2021 email.

The FBI had warned local police about the activity before. In a list of Patriot Front-related vandalism incidents, local police noted that the FBI had reported “two males” who they “reported walking up and down 4th St putting propaganda stickers on light poles that read ‘for the nation against the state,’” alongside Patriot Front’s website address. The feds were “Unable to locate the individuals involved,” according to call notes associated with the incident.

Also in that summer of 2021, Idaho police warned an FBI senior resident agent in an email that the city had recently been “papered with a number of large Patriot Front posters that advertises the website” for the group.

Neither the FBI nor Coeur d’Alene police immediately responded to questions from Rolling Stone.

When local police began tracking threats to NIPA’s planned Pride month events for June 11 of this year, the FBI also pitched in to help.

“At this point we are working with the local FBI here as well as our surrounding agencies to develop a plan for the CDA June 11th event,” a specialist from the Coeur d’Alene police’s crime analysis and intervention unit wrote in response to reports of far-right threats to the group.

Threats to NIPA’s event came not just from Patriot Front, as the arrests suggest, but a handful of far-right groups in the weeks leading up to June 2022. In April, a local Proud Boys chapter circulated calls from far-right activists that “groomers” would be gathering in a park in Coeur d’Alene for Pride Month. Multiplied in the weeks leading up to the event and grew to include harassment from a local far-right biker club, the “Panhandle Patriots.”

There, again, the FBI was monitoring the far-right ecosystem targeting the event. An Idaho Falls criminal intelligence analyst wrote to colleagues that the FBI had shared a tip that “Panhandle Patriot Club threatened to physically assault individuals taking part in the pride parade in Idaho Falls on 6/25/2022,” with one member allegedly saying “If gays want a war, we’ll give them a war.” (The Panhandle Patriots opted not to show up and confront NIPA’s “Pride in the Park” event).

It’s unclear just how much time and attention the FBI has spent monitoring Patriot Front, either in Idaho or elsewhere. But it does give an indication of the breadth of the Bureau’s monitoring of white nationalist groups. “They are actively providing information to local law enforcement so they can intercede to ensure the health and safety of others,” Renato Mariotti, a former federal prosecutor, told Rolling Stone.

“This is not unusual, Mariotti added. “When I would conduct long-term investigations of criminal organizations, I would frequently direct federal law enforcement and agents I was working with to tip off local police departments, if we came across information that there may be a serious danger to the health or safety of others. Oftentimes, we would not tell the departments how exactly we came across this information, but we would do this even if we were investigating a different crime or conducting a separate long-term investigation.”

Gov. Rick Snyder. (photo: Saul Loeb/Getty Images)

Gov. Rick Snyder. (photo: Saul Loeb/Getty Images)

The Michigan Supreme Court deemed the indictments against ex-Gov. Rick Snyder and eight others invalid.

State laws merely “authorize a judge to investigate, subpoena witnesses, and issue arrest warrants,” but “do not authorize the judge to issue indictments,” the court’s 6-0 opinion reads.

Attorney General Dana Nessel took office in 2019, and assembled a new team to investigate Snyder and a slew of advisers and officials who were in charge when Flint’s water supply became contaminated with lead beginning five years earlier. An outbreak of Legionnaire’s Disease in 2014 and 2015 was attributed to issues with the city’s water, as well.

Their alleged crimes included, among others, misconduct in office, willful neglect of duty, and involuntary manslaughter. Genesee County Judge David Newblatt reviewed the evidence and issued indictments as a so-called “one-man grand jury,” Tuesday’s opinion argues.

Newblatt “considered the evidence behind closed doors, and then issued indictments against defendants,” the opinion states, noting that—unlike a grand jury made up of citizens, a “one-man grand jury,” that is, a judge, do not require a jury oath and thus “cannot initiate charges by issuing indictments.”

Nakiya Wakes, who moved to Flint in June 2014, told The Daily Beast on Tuesday that she was shocked and dismayed at the news. A year after arriving in the city, Wakes suffered two miscarriages. Her children, Jalen and Nashauna, both tested positive for lead in their blood after the family settled in Flint.

“It’s straight BS,” Wakes said in a phone call following the court’s decision. “Nobody is being held accountable for their actions. This, for all of us, it’s like we have no justice at all... There were deaths from Legionnaire’s Disease, all these kids were poisoned. We don’t know what’s going to happen to us 10, 15 years down the line, and nobody is being held accountable.”

In the Flint case, the accused were denied a preliminary examination of the evidence, according to the court.

“Given the magnitude of the harm suffered by Flint’s residents, it was paramount to adhere to proper procedure to guarantee to the general public that Michigan’s courts could be trusted to produce fair and impartial rulings for all defendants regardless of the severity of the charged crime,” the opinion says.

“The prosecution cannot cut corners—here, by not allowing defendants a preliminary examination as statutorily guaranteed—in order to prosecute defendants more efficiently. The criminal prosecutions provide historical context for this consequential moment in history, and future generations will look to the record as a critical and impartial answer in determining what happened in Flint.”

The crisis in Flint unfolded in April 2014, when the city switched its water supply from Detroit’s system to the Flint River. The nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) later called the cost-saving move a “story of environmental injustice and bad decision making.”

The plan was meant to be temporary, with water being pumped from the Flint River into homes only until a new pipeline from Lake Huron could be completed. In the meantime, Flint residents soon noticed that something was wrong with their water, which now looked, smelled, and tasted bad. As it turned out, old pipes were leaching lead into the water going to people’s homes, while government officials insisted everything was fine.

A year later, water samples collected by researchers would reveal an extremely serious problem, with lead far exceeding acceptable levels set by the federal government. In 2016, another study found that the level of lead in Flint children’s bloodstreams had nearly doubled since 2014, with numbers tripling in some parts of the city.

“Lead is a potent neurotoxin, and childhood lead poisoning has an impact on many developmental and biological processes, most notably intelligence, behavior, and overall life achievement,” wrote lead author and pediatrician Mona Hanna-Attisha. “With estimated societal costs in the billions, lead poisoning has a disproportionate impact on low-income and minority children. When one considers the irreversible, life-altering, costly, and disparate impact of lead exposure, primary prevention is necessary to eliminate exposure.”

In Flint, almost 9,000 kids were drinking lead-poisoned water for a year-and-a-half, according to the NRDC.

Once a vibrant manufacturing town, Flint began a slow decline in the 1980s. With its population cleaved in half, more than 37 percent of people in Flint now live below the poverty line.

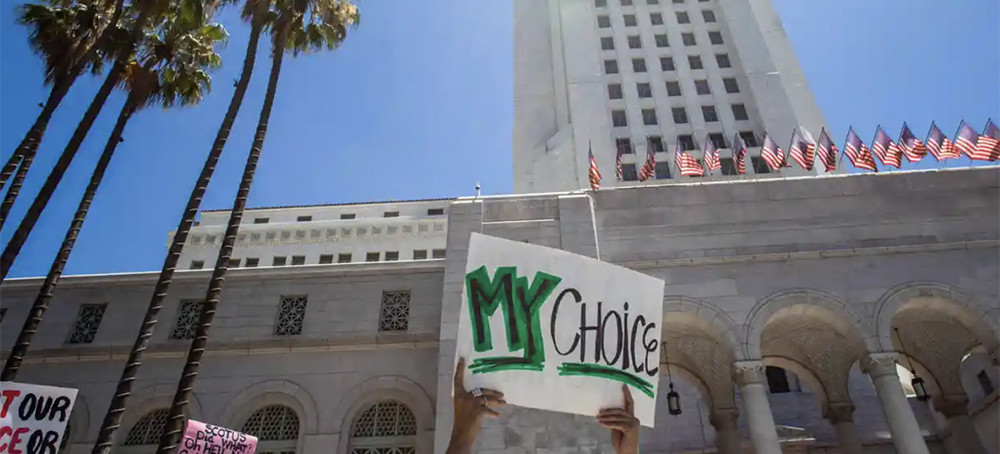

People protest in front of city hall in downtown Los Angeles, on 25 June. (photo: Apu Gomes/AFP/Getty Images)

People protest in front of city hall in downtown Los Angeles, on 25 June. (photo: Apu Gomes/AFP/Getty Images)

The amendment added to this year’s ballot is part of Democrats’ aggressive strategy to expand access to abortion

The court’s ruling on Friday gives states the authority to decide whether to allow abortion. California is controlled by Democrats who support abortion rights, so access to the procedure won’t be threatened anytime soon.

But the legal right to an abortion in California is based upon the “right to privacy” in the state constitution. The supreme court’s ruling declared that a right to privacy does not guarantee the right to an abortion. California Democrats fear this ruling could leave the state’s abortion laws vulnerable to challenge in state courts.

To fix that, California lawmakers on Monday agreed to put a constitutional amendment on the ballot this year that would leave no doubt about the status of abortion in California.

The amendment would declare that the state “shall not deny or interfere with an individual’s reproductive freedom in their most intimate decisions, which includes their fundamental right to choose to have an abortion and their fundamental right to choose or refuse contraceptives”.

California joins Vermont in trying to protect abortion in its state constitution. The Vermont proposal, also on the ballot this November, does not include the word “abortion” but would protect “personal reproductive autonomy” – although there is an exception “justified by a compelling state interest achieved by the least restrictive means”.

Meanwhile, four conservative states – Alabama, Louisiana, Tennessee and West Virginia – have constitutions that say a right to an abortion is not protected, according to the Guttmacher Institute, an abortion rights group.

The amendment in California is part of Democrats’ aggressive strategy to expand access to abortion in response to the US supreme court’s ruling. Last week, Gavin Newsom signed a law aimed at shielding California abortion providers and volunteers from lawsuits in other states – a law aimed at blunting a Texas law that allows private citizens to sue people who help women in that state get an abortion.

California’s massive budget includes more than $200m to expand access to abortion in the state. The money would help pay for abortions for women who can’t afford them, scholarships for abortion providers and a new website listing all of the state’s abortion services in one place.

The budget also includes $20m to help women pay for the logistics of an abortion, including travel, lodging and child care. But the Newsom administration says the money can’t be used to help women from other states where abortion is illegal or severely restricted come to California to get the procedure.

A dozen other bills are pending that would support those seeking and providing abortions such as allowing some nurse practitioners perform abortions without the supervision of a doctor and block disclosure of abortion-related medical records to out-of-state entities.

In Uvalde, Texas, two police squad cars approach San Antonio Express-News photographer William Luther while he was trying to take photographs outside a funeral from a public sidewalk on June 5. (photo: Yi-Chin Lee/Houston Chronicle)

In Uvalde, Texas, two police squad cars approach San Antonio Express-News photographer William Luther while he was trying to take photographs outside a funeral from a public sidewalk on June 5. (photo: Yi-Chin Lee/Houston Chronicle)

Reporters came to Texas to tell the story of the Robb Elementary School massacre. But ‘we were seen as enemies’ by police, they say.

Nevertheless, a phalanx of uniformed bikers confronted Gill outside the cemetery gates. They called themselves “Guardians of the Children” and claimed to be working with police officers who stood watch.

“I’m not trying to disturb anyone, guys,” Gill told the bikers, in a video he posted online. “I’m not trying to ask anybody any questions. I just wanted to watch. That’s all we can do, right?”

But the bikers followed and harassed journalists anyway, Gill wrote in the Chronicle. When he accidentally bumped into a Guardian who claimed to be a paramedic, the bikers accused him of assault and battery. “As a public servant, that’s kind of a felony,” the biker-paramedic said in the video.

A month after 19 children and two educators were killed at Robb Elementary School, a picture is emerging of a disastrous police response, in which officers from several law enforcement agencies waited for an hour outside an unlocked classroom where children were trapped with the attacker. But journalists who have flocked to Uvalde, Tex., from across the country to tell that story have faced near-constant interference, intimidation and stonewalling from some of the same authorities — and not only bikers claiming to have police sanction.

Journalists have been threatened with arrest for “trespassing” outside public buildings. They have been barred from public meetings and refused basic information about what police did during the May 24 attack. After several early, error-filled news conferences, officials have routinely turned down interview requests and refused to hold news briefings. The situation has been made even more fraught by the spider’s web of local and state agencies involved in responding to and investigating the shooting, some of which now blame each other for the chaos.

“Our reporters have covered [the 2017 massacre in] Sutherland Springs, the Fort Hood shooting, and some are very experienced, having been embedded with military in Afghanistan, covered revolutions in Latin American, and none of them could remember an experience like this,” said Marc Duvoisin, editor in chief of the San Antonio Express-News. “The interference was so intense and without an identifiable public safety purpose.”

Duvoisin has complained to Uvalde city leaders and some police chiefs — one of whom apologized, he said. Some of his journalists nevertheless asked not to be sent back to Uvalde, or confessed to feeling guilty for their work there. Harassment became so bad that the newspaper’s photo director told photographers to document their treatment by police.

One photographer, William Luther, reported that police repeatedly pushed journalists back from a cemetery procession on May 31: first into the street, then onto a sidewalk where a taqueria owner had previously given them permission to stand. He said an officer falsely told him that the owner had demanded he leave, and threatened him when he offered to apologize: “If you go into that taqueria, I’m going to arrest you.”

Police were documented repeatedly obstructing photographers in public areas over the following days, sometimes standing or parking vehicles directly in front of their cameras. Both Texas Department of Public Safety officials and Uvalde police did not respond to requests for comment.

“The police were not letting us work,” said Antonio Guillen, a photographer for the Univision station in San Antonio. “We were seen as enemies.”

Meanwhile, law enforcement agencies have resisted releasing information that could shed light on how police responded to the attack. Duvoisin said the “information crisis” in Uvalde began the moment school officials posted a notice on Facebook that Robb Elementary school had been locked down.

Reporters and editors could not reach any authorities in Uvalde able to give basic information over the next several hours, he said. There were no briefings by local police, no statements of facts about the events, and few, if any, returned calls. The first public address came not from local authorities, as is common after mass shootings, but from the Texas governor, several hours after the carnage ended.

It is not unusual for public information to be lacking in the aftermath of a catastrophe, or for locals to be rankled when hordes of reporters converge on a small town. But the pattern of miscommunication, stonewalling and intimidation in Uvalde has surprised even journalists with decades of experience, and led some to suspect it is intentional.

State officials held a disastrous news conference two days after the attack, in which Texas Department of Public Safety spokesman Victor Escalon ignored pleas to provide information in Spanish (Uvalde County’s population is mostly Hispanic), and lacked basic information such as how long it took police to arrive after the first 911 call. “Could anybody have got there sooner?” he said told reporters. “You gotta understand, small town.”

In the weeks since, officials have refused to release information that might explain why officers missed opportunity after opportunity to confront the attacker earlier and potentially save lives.

The Texas Tribune and ProPublica have jointly submitted 70 requests for public information to state, local and federal agencies, seeking records such as ballistic reports and death certificates. They have received two “partial” releases, according to Sewell Chan, the editor in chief of the Texas Tribune, which has done some of the most extensive reporting on the Uvalde tragedy. He said several agencies have not responded or have asked the state attorney general to review the request — a process that typically takes months.

Uvalde Mayor Don McLaughlin last week accused state authorities of selectively releasing information to scapegoat local law enforcement officials, rather than DPS officers who also responded to the shooting. “I actually wonder who the hell’s in charge of this investigation, because you can’t get a straight answer,” McLaughlin said.

But transparency watchdogs suspect the bureaucratic confusion is an excuse for delay. “It’s a convenient prop,” said Kelley Shannon, the executive director of the Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas. “It’s an excuse. They can release any information they want.”

Sen. Roland Gutierrez, a Democrat representing Uvalde, filed a lawsuit last week against DPS to compel it to disclose its records. A coalition of news organizations that includes the parent companies of CNN, CBS News, ABC News and TelevisaUnivision is discussing similar legal action.

Meanwhile, journalists keep running into obstacles as they try to gather information on the ground.

At a committee hearing in Uvalde last week of Texas House legislators investigating law enforcement officials’ response to the massacre, a fire marshal announced that all reporters would have to leave the building and wait outside in triple-digit heat.

The journalists were “intimidating” people, the marshal explained, as a CNN correspondent kept recording video of the eviction.

More than headlines or public fascination is at stake. Definitive answers about the shooting could lead to criminal charges, guide future law enforcement responses during mass shootings and may provide some comfort to the victims’ families.

But for the time being, it’s often a struggle just to snap a photo.

“In no way would I compare this to reporting under an authoritarian regime,” said Chan, the Texas Tribune editor. But the roadblocks to information erected by city and state officials, he said, “should trouble anyone who cares about the free press’s role in our democracy.”

Peru. (photo: Marcos Reategui/Getty Images)

Peru. (photo: Marcos Reategui/Getty Images)

Out of work and short on cash and food, a fishing community in Peru is simultaneously paralyzed by exhaustion and ready to boil over.

On January 15, the oil tanker Mare Doricum released oil that, over the course of the month, spread over approximately 100 square kilometers — an area almost twice the size of Manhattan that includes two protected areas. Additionally, the oil contaminated an estimated 37,000 tons of sand.

Despite initial outrage, the spill has been all but pushed out of the media cycle in a country that is undergoing a prolonged political crisis. Yet now, five months later, affected communities are still reeling. Though the Peruvian government is pursuing civil and criminal action against Repsol and other parties, fishers still can’t go out to sea, and most of the traditional seafood eateries in Ancón are closed. Across the region, the oil spill continues to be responsible for a slew of lingering effects.

One group that is still suffering are the fishers Repsol hired to help clean up the spill. Juan Carlos Riveros, scientific director in Peru for the international advocacy organization Oceana, says Repsol paid out-of-work fishers 50 soles, or $13 U.S. dollars, per day to clean up the soiled beaches. The company “gave them nothing but a cotton suit, a surgical mask, and a garbage shovel,” Riveros says. Some fishers claim to be experiencing symptoms of prolonged oil exposure, including rashes, headaches, and arthritis-like symptoms.

“What [Repsol] did was nothing short of criminal,” says Riveros. (There is no official documentation on the aftereffects of the spill on the health of the hired fishers, as the Ministry of Health says that it has not conducted any medical assessment.)

The spill has also disrupted local food security. Though Peru is home to one of the richest fishing grounds on the planet, second only to China, much of the country’s catch goes to producing fish meal for global livestock and aquaculture. Peruvians still largely rely on artisanal fishers. But in the wake of the spill, the government issued a ban on fishing that has been extended indefinitely, leaving coastal communities struggling to obtain affordable protein.

Héctor Samillán, a shellfish fisher and president of the association of shellfish fishers in Ancón, says he used to bring crabs or sea snails home every day. “My kids only had to boil some rice for us to have a great meal. Now that’s gone,” Samillán says.

The fishing ban has put fishers like Samillán out of work for months. Though thousands have turned to temporary jobs as construction workers, delivery drivers, or security guards, there are only so many jobs to go around. Fishing elsewhere is also not easy. “I can’t just move to another town and start fishing there,” Samillán says. “They already have quotas and permits in place; there’s no room for us there.”

Fishers grounded by the spill are supposed to be receiving compensation from Repsol, which pledged a provisional $750 U.S. dollars monthly to each affected fisher, according to Peru’s prime minister Aníbal Torres. Yet the compensation effort has been sporadic and incomplete.

That effort is made all the more difficult by the fact that even establishing the number of affected fishers is not easy. While Peru’s artisanal fishery is responsible for up to 20 percent of the country’s total catch, the number of artisanal fishers is unknown to the government, and approximately 60 percent of artisanal fishing vessels are “informal,” meaning they lack a fishing permit. Both Repsol and the Peruvian government have repeatedly argued that this has made it impossible to calculate the true extent of the damage.

But the gulf between official statistics and the reality they are supposed to represent appears to be massive. This might be in part because, unlike other countries, Peru has no agency in charge of coordinating the actions surrounding the spill. While the Peruvian Ministry of Production decided around 5,000 people warranted economic compensation, a different state agency, the National Consumer Protection Authority, calculated the number to be closer to 700,000.

Yet even the fishers who are receiving compensation have only seen two rounds of payments in the five months since the spill, and there is no confirmation on when or whether a third one is coming. Many fishers and sellers say they have been left out of the compensation register. The National Institute of Civil Defense in Peru, the agency in charge of keeping the register, stated it would publish an updated list in early June but didn’t.

The disjointed compensation effort and lack of transparency from both the government and Repsol have caused a rift in this once-cooperative community.

Since 2012, Ancón fishers have been implementing self-imposed quotas and fishing seasons to ensure the sustainability of the fish and shellfish populations in the area. But with experts warning it might take years before there are viable populations to fish in the region again, Samillán fears that sacrifice might have been in vain.

“For over 10 years, I made the decision to bring home less money and convinced others to do the same,” he says. “I knew the future was in sustainability, but it’s all gone down the drain.”

The opacity and confusion surrounding compensation is pushing people to the brink. Some are angry at being left out of negotiation packages. Others, like a fish vendor who argued with fishers at the port for “giving the bay up for a bag of lentils” right before being chased off, are accusing beneficiaries of selling out to Repsol.

Jesús Huber, a 60-year-old artisanal fisher, says he is tired of waiting. Disappointed and overwhelmed by debt, he wonders whether more extreme measures are needed.

“I think it is time to block major highways because peaceful protesting is not working anymore. I’m done,” he says, to the approving nods of his fellow fishers.

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.