Final Day — We Surely Need a Good One

This is the last day of the month and we are not even close to where we need to be. We have made up a bit of ground in the past few days but it’s been tough and frustrating going.

Stop for just a moment and throw something in the hat.

In peace and solidarity.

Marc Ash

Founder, Reader Supported News

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The Russian leader’s assault on a sovereign state has not only helped to unify the West against him; it has helped to unify Ukraine itself.

Like many aging autocrats, Putin has, over time, remained himself, only more so: more resentful, more isolated, more repressive, more ruthless. He operates in an airless political environment, free of contrary counsel. His stagecraft—seating foreign visitors at the opposite end of a twenty-foot-long table, humiliating security chiefs in front of television cameras—is a blend of “Triumph of the Will” and “The Great Dictator.” But there is nothing comic in the performance of his office. As Putin spills blood across Ukraine and threatens to destabilize Europe, Russians themselves stand to lose immeasurably. The ruble and the Russian stock market have cratered. But Putin does not care. His eyes are fixed on matters far grander than the well-being of his people. He is in full command of the largest army in Europe, and, as he has reminded the world, of an immense arsenal of nuclear weapons. In his mind, this is his moment, his triumphal historical drama, and damn the cost.

Putin’s official media outlets echo his claim that the Army’s mission is to stop a Ukrainian “genocide” against the Russian-speaking population in that country. His deployment of distortion and deception as weapons is hardly unique. After the First World War, many German reactionaries and military leaders, in their humiliation, declared that they had not lost on the battlefield; instead, disloyal leftists, scheming politicians, and, above all, the Jews had stirred up labor unrest in the arms industry in order to undermine the war effort. This was the legend of the Dolchstoss im Rücken, the stab-in-the-back story that Hitler used to denigrate the Weimar Republic, in general, and the Jews, in particular, as he built support for his fascist movement and another war.

History is never a settled matter. American politics is no stranger to fierce arguments about the past. But, when an autocrat is the sole narrator of the national archive, history becomes subsumed into the instrumental aims of policy and control. This has long been the case in Russia. In 1825, Tsar Nicholas I put down the Decembrist uprising and then sought to expunge the affair from the official history books, lest the revolt be repeated. What little freedom scholars had under the Communist Party vanished when, in 1928, the All-Union Conference of Marxist Historians declared that the chief historian of the Soviet Union was its dictator, Josef Stalin. He was the putative author of “Kratki kurs”—“The Short Course”—which described how all of human history had led inexorably to the glorious revolution and the Communist Party; all his Bolshevik rivals were “White Guard pygmies whose strength was no more than that of a gnat.” No alternatives to “The Short Course” were permitted.

In 1956, Nikita Khrushchev took a step toward restoring history. In his so-called secret speech to the Communist Party leadership, he criticized Stalin for carrying out purges of Party members, inadequately preparing for war with Nazi Germany, and cruelly deporting and oppressing ethnic minorities. Khrushchev’s remarks, though concealed from the population, led to a short-lived “thaw,” and to the release of many thousands of Soviet political prisoners.

But it was not until Mikhail Gorbachev came to power that a Kremlin leader opened a true discussion of the past. “Even now, we still encounter attempts to ignore sensitive questions of our history, to hush them up,” Gorbachev said, in 1987, in a speech marking the seventieth anniversary of the October Revolution. “We cannot agree to this. It would be a neglect of historical truth, disrespect for the memory” of those who were repressed.

That speech proved shrewd and transformative. Gorbachev signalled that the time had come to examine the history of the Soviet Union, including the “secret protocols” of Stalin’s pact with Hitler, which paved the way for the annexation of the Baltic states and the brutal subjugation of Poland. Nearly overnight, Soviet citizens learned how the decisions had been made to invade Budapest, in 1956, Prague, in 1968, and Kabul, in 1979. One of the watersheds of the Gorbachev era was the creation, in 1989, of Memorial, an organization charged with exploring Soviet history and its archives and upholding the principles of the rule of law and of human rights. Putin’s regime, mobilizing against civil society, has tellingly designated Memorial a “foreign agent” and ordered the group to be shut down.

Putin, who blames Gorbachev for defiling the reputation and the stability of the Soviet Union, and Boris Yeltsin, the leader who succeeded him, for catering to the West and failing to hold back the expansion of NATO, reveres strength above all. If he has to distort history, he will. As a man who came into his own as an officer of the K.G.B., he also believes that foreign conspiracy is at the root of all popular uprisings. In recent years, he has regarded pro-democracy protests in Kyiv and Moscow as the work of the C.I.A. and the U.S. State Department, and therefore demanding to be crushed. This cruel and pointless war against Ukraine is an extension of that disposition. Not for the first time, though, a sense of beleaguerment has proved self-fulfilling. Putin’s assault on a sovereign state has not only helped to unify the West against him; it has helped to unify Ukraine itself. What threatens Putin is not Ukrainian arms but Ukrainian liberty. His invasion amounts to a furious refusal to live with the contrast between the repressive system he keeps in place at home and the aspirations for liberal democracy across the border.

Meanwhile, Volodymyr Zelensky, the President of Ukraine, has behaved with profound dignity even though he knows that he is targeted for arrest, or worse. Aware of the lies saturating Russia’s official media, he went on television and, speaking in Russian, implored ordinary Russian citizens to stand up for the truth. Some needed no prompting. On Thursday, Dmitry Muratov, the editor of the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, and a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, said that he would publish the next issue in Russian and Ukrainian. “We are feeling shame as well as sorrow,” Muratov said. “Only an antiwar movement of Russians can save life on this planet.” As if on cue, demonstrations against Putin’s war broke out in dozens of Russian cities. Leaders of Memorial, despite the regime’s liquidation order, were also heard from: the war on Ukraine, they said, will go down as “a disgraceful chapter in Russian history.”

Lloyd Austin. (photo: Paulius Peleckis/Getty Images)

Lloyd Austin. (photo: Paulius Peleckis/Getty Images)

“He learned about it through the announcement. The announcement came right before the secretary was hosing one of his daily operations and policy synchronization meetings which was held this morning at 8:30,” the senior U.S. defense official said. “That announcement was discussed in the context of that meeting.”

Putin issued the alarming announcement about his nuclear forces on Sunday, claiming he was placing them on high alert in response to what he said were “aggressive” comments from NATO powers. The senior U.S. defense official would not touch on the status of U.S. nuclear forces, but is confident in the United States’ ability to defend the country, allies, and partners. “It is always a priority to be able to defend the homeland and to make sure our strategic deterrence is capable, viable and ready at all times,” the official said. The news comes just as Ukrainian President Zelensky’s office announced Ukraine has agreed to talks with Russian officials.

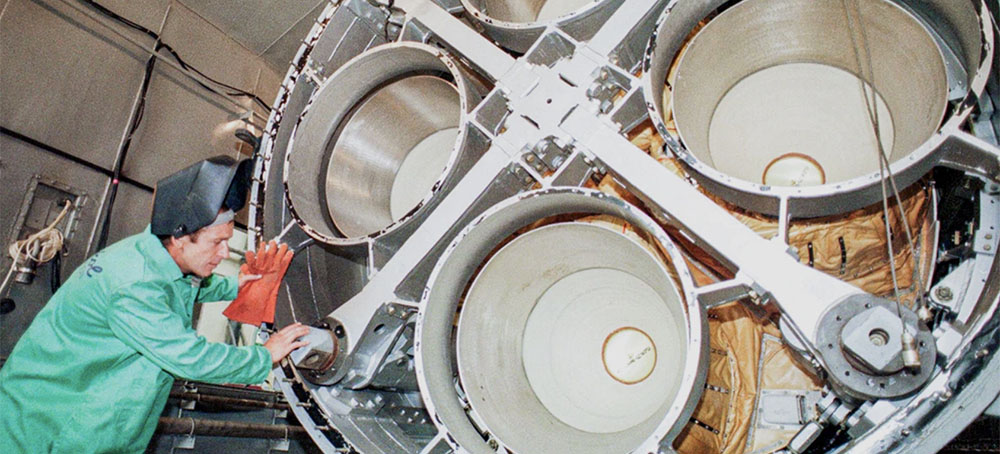

An engineer examines the engine of an SS-19 intercontinental ballistic missile in Dnipro, Ukraine, on July 26, 1996. Photo: Efrem Lukatsky/AP)

An engineer examines the engine of an SS-19 intercontinental ballistic missile in Dnipro, Ukraine, on July 26, 1996. Photo: Efrem Lukatsky/AP)

In the 1990s, world powers promised Ukraine that if it disarmed, they would not violate its security. That promise was broken.

The decision to disarm was portrayed at the time as a means of ensuring Ukraine’s security through agreements with the international community — which was exerting pressure over the issue — rather than through the more economically and politically costly path of maintaining its own nuclear program. Today, with Ukraine being swarmed by heavily armed invading Russian troops bristling with weaponry and little prospect of defense from its erstwhile friends abroad, that decision is looking like a bad one.

The tragedy now unfolding in Ukraine is underlining a broader principle clearly seen around the world: Nations that sacrifice their nuclear deterrents in exchange for promises of international goodwill are often signing their own death warrants. In a world bristling with weapons with the potential to end human civilization, nonproliferation itself is a morally worthwhile and even necessary goal. But the experience of countries that actually have disarmed is likely to lead more of them to conclude otherwise in future.

The betrayal of Ukrainians in particular cannot be understated. In 1994, the Ukrainian government signed a memorandum that brought its country into the global Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty while formally relinquishing its status as a nuclear state. The text of that agreement stated that in exchange for the step, the “Russian Federation, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the United States of America reaffirm their obligation to refrain from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine.”

Ukraine’s territorial integrity has not been much respected since. After the 2014 annexation of the Ukrainian territory of Crimea by Russia — which brought no serious international response — Ukrainian leaders had already begun to think twice about the virtues of the agreement they had signed just two decades earlier. Today they sound positively bitter about it.

“We gave away the capability for nothing,” Andriy Zahorodniuk, a former defense minister of Ukraine, said this month about his nation’s former nuclear weapons. “Now, every time somebody offers us to sign a strip of paper, the response is, ‘Thank you very much. We already had one of those some time ago.’”

Ukrainians are not the only ones who have come to regret signing away their nuclear weapons. In 2003, Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi made a surprise announcement that his nation would abandon its nuclear program and chemical weapons in exchange for normalization with the West.

“Libya stands as one of the few countries to have voluntarily abandoned its WMD programs,” wrote Judith Miller a few years later in an article about the decision headlined “Gadhafi’s Leap of Faith.” Miller, then just out of the New York Times, added that the White House had opted “to make Libya a true model for the region” by helping encourage other states with nuclear programs to follow Gaddafi’s example.

Libya kept moving forward. It signed on to an additional protocol of the International Atomic Energy Agency allowing for extensive international monitoring of nuclear reserves. In return, sanctions against the country were lifted and relations between Washington and Tripoli, severed during the Cold War, were reestablished. Gaddafi and his family spent a few years building ties with Western elites, and all seemed to be going well for the Libyan dictator.

Then came the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings. Gaddafi found that the same world leaders who had ostensibly become his economic partners and diplomatic allies were suddenly providing decisive military aid to his opposition — even cheering on his own death.

Promises, betrayals, aggression: It’s a pattern that extends even to countries that have merely considered foreclosing their avenues to a nuclear deterrent.

Take Iran: In 2015, the Islamic Republic signed a comprehensive nuclear deal with the U.S. that limited its possible breakout capacity toward building a nuclear weapon and provided extensive monitoring of its civilian nuclear program. Not long afterward, the agreement was violated by the Trump administration, despite the country’s own continued compliance. Since 2016, when Trump left the deal, Iran has been hit with crushing international sanctions that have devastated its economy and been subjected to a campaign of assassination targeting its senior military leadership.

The nuclear deal was characterized at the time as the first step toward a broader set of talks over regional disputes between Iranian and U.S. leaders, who had been alienated since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Instead, the deal marked another bitter chapter in the long-troubled relationship between the two countries.

To date, no nuclear-armed state has ever faced a full-scale invasion by a foreign power, regardless of its own actions. North Korea has managed to keep its hermetic political system intact for decades despite tensions with the international community. North Korean officials have even cited the example of Libya in discussing their own weapons. In 2011, as bombs rained down on Gaddafi’s government, a North Korean foreign ministry official said, “The Libyan crisis is teaching the international community a grave lesson.” That official went on to refer to giving up weapons in signed agreements as “an invasion tactic to disarm the country.”

Perhaps the starkest contrast to the treatment of Ukraine, Libya, and Iran, however, is Pakistan, which developed nuclear weapons decades ago in defiance of the United States. Despite being criticized at the time for contributing to nuclear proliferation and facing periodic sanctions, Pakistan has managed to insulate itself from attack or even serious ostracism by the U.S. despite several flagrant provocations in the decades since. Today Pakistan even remains a security partner of the U.S., having received billions of dollars of military aid over the past several decades.

Given the mortal hazards that nuclear weapons pose to life on Earth, nonproliferation remains a worthwhile collective goal. Humanity will not benefit from a renewal of the nuclear arms race, and the ideals behind a U.S.-backed rules-based liberal order are morally attractive. A world in which they were truly applied would probably be a fairer and more peaceful one than what has existed in the past, yet we must also recognize that the liberal order can and will fail. That lesson is especially true for small nations outmatched by great powers.

Given the tragedy we are witnessing in Ukraine today — where, despite its past assurances, the international community has remained a passive observer — leaders of small countries must be forgiven for thinking twice before sacrificing their deterrent, regardless of what the leaders of great powers already armed with nuclear weaponry may say.

Vladimir Putin. (photo: Alexey Druzhinin/Bloomberg)

Vladimir Putin. (photo: Alexey Druzhinin/Bloomberg)

The threat of nuclear weapons never went away. But Putin’s invasion of Ukraine makes it visible again.

Another part of his speech seemed to make his meaning clear. “Today’s Russia remains one of the most powerful nuclear states,” Putin said. As justification for the invasion, Putin also made unfounded claims that Ukraine was on a path to build its own nuclear arsenal. “There’s no evidence of that at all,” said Hans Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists.

The Russian invasion has relied entirely on conventional weapons — tanks rattling down highways, bombers flying overhead, ships landing in the port city of Odesa — and experts told Vox that in the absence of a shocking escalation, that isn’t likely to change.

Still, Putin’s remarks were a stark reminder that nuclear weapons aren’t just the boogeymen of a bygone age, but remain a key part of the security order that emerged after the end of World War II. By Kristensen’s count, Russia has about 6,000 nuclear weapons and the United States has about 5,500. Either nuclear arsenal is large enough to kill billions of people — but also to serve as a deterrent against attack.

In recent decades, the so-called nuclear order has remained fairly stable. The seven other countries known to have nuclear weapons have much smaller arsenals. Most countries in the world have signed onto the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which limits the development of nuclear weapons. We asked three researchers of nuclear arms control about the risks the world faces now and what we might be able to do about them.

How worried should we be about the threat of nuclear weapons right now?

While Putin’s remarks are certainly cause for concern — especially since they introduced the largest military operation in Europe since the Second World War — the scholars who spoke to Vox said a nuclear strike is still unlikely. “I think there is virtually no chance nuclear weapons are going to be used in the Ukraine situation,” said Matthew Bunn, a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School and former adviser to President Bill Clinton’s Office of Science and Technology Policy.

The main reason, Bunn said, is that the United States and its NATO allies have made it clear that they will not send troops to Ukraine. Without the threat of military intervention, Putin has little reason to use his nuclear weapons, especially since Russia has a staggering numbers advantage over the Ukrainian military.

“His objective is not to bring the world to nuclear war,” said Paul Hare, senior lecturer in global studies at Boston University. “His objective is to simply swallow Ukraine — and restore not just the [power of the] Soviet Union, but the Tsarist empire.”

Still, said Kristensen, “I’m more worried than I was a week ago.” He pointed out that NATO increased its readiness levels for “all contingencies” in response to Putin’s speech, and with increased military buildup comes increased uncertainty. “That’s the fog of war, so to speak,” Kristensen said. “Out of that can come twists and turns that take you down a path that you couldn’t predict a week ago.”

What does Russia’s nuclear arsenal look like? How does it compare to others in the world?

Russia’s roughly 6,000 warheads make it the country with the largest nuclear arsenal. Kristensen said most of those warheads are in reserves, with only about 1,600 deployed as land, sea, and air-based weapons, such as missiles in silos or bombs dropped by planes. (When the USSR fell apart at the end of the Cold War, there were nuclear weapons left behind on Ukrainian soil, but Ukraine returned them to Russia.)

The countries known to have nuclear weapons are Russia, the US, China, France, the UK, Pakistan, India, Israel, and North Korea. That includes every permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, which have been working to modernize their nuclear weapons over the past few decades, and three members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. The total number of weapons has dropped by about 80 percent since the end of the Cold War, from an estimated 70,300 in 1986 to 12,700 in early 2022.

That’s still a lot of nukes. “There has been much discussion about whether that means Russia has a sort of trigger-happy nuclear posture,” Kristensen said. “It’s hard to pin down. if Russian officials were asked to sit down around a table and entirely consider how many tactical nuclear weapons were needed, purely based on real, strategic rationales, I suspect that number would quickly drop to a lot less [than what it is today].”

Does Putin have a reason to consider using nuclear weapons?

From a strategic standpoint, the experts said, there’s no reason for Russia to use nuclear weapons. But they said Putin himself was the biggest source of uncertainty. “The element of emotion and anger that’s crept into Putin’s statements in particular is striking,” said Hare. “Normally we’ve associated Russia’s diplomatic style with a kind of laconic, almost sarcastic manner.”

It’s worth remembering, Kristensen added, that Putin often makes allusions to Russia’s nuclear arsenal as a show of strength. In 2015, he said in a Russian state TV documentary that he had considered putting Russian nuclear forces on alert during the Russian annexation of Crimea a year prior.

This could be a sign that Putin’s nuclear rhetoric is more bark than bite, but Kristensen wasn’t ready to say that for sure. “He lives in a very small bubble, and he’s deeply paranoid,” Kristensen said. “He’s willing to do really not very rational things.”

Is the fear of a nuclear war enough to stop countries from using nuclear weapons?

“The physical fact of a nuclear weapon’s destructive power absolutely creates fear,” said Bunn. Nuclear deterrence — the idea that one country wouldn’t dare attack another for fear of a nuclear strike — was the major security policy of the Cold War period, and experts say it remains very much alive today. As my colleague Zack Beauchamp recently wrote, the threat of nuclear weapons is the reason the US won’t send troops to Ukraine.

But nuclear deterrence clearly didn’t end all wars. The existence of nuclear weapons “didn’t help us in Vietnam, they didn’t help us in Iraq, they didn’t help us in Afghanistan,” Bunn said. “Nuclear weapons aren’t useful for the majority of the security and well-being challenges that the United States faces.”

Since the Cold War, it’s been widely accepted that nuclear deterrence would help ensure that the borders of Europe would not be challenged. The Ukraine crisis, said Hare, is casting some doubt on that idea. “The credibility of deterrence hasn’t been tested for decades,” Hare said. “The whole international order is sort of being thrown up in the air. Is the Ukraine attack going to be a prelude to an attack on, say, the Baltic states that are even more vulnerable, or is Putin going to be satisfied with Ukraine?”

The answer, Hare said, will shape how the United States and its NATO allies decide to deploy their forces — conventional and nuclear — around the world. “We’re starting to see large powers begin to sort of entertain the thought of limited tactical nuclear weapons use scenarios, in a way that they didn’t spend very much time thinking about 10 years ago,” said Kristensen. These are the sorts of unlikely scenarios that have been tossed around in war games as contingencies since the Cold War, and could entail strikes on isolated military targets that are far from population centers, for example.

“The theory is very much like it was during the Cold War,” Kristensen explained. “You just sort of have some smaller nukes that you can pop off here and there, to force an adversary to take an off-ramp during a conflict.”

Is the world doing a good job keeping nuclear weapons under control?

For the most part, global efforts to prevent nuclear weapons from spreading, like the Non-Proliferation Treaty, have been strikingly successful. But these efforts need constant attention and maintenance. “Globally, the nuclear order is in pretty bad shape,” said Bunn. North Korea continues to build up its nuclear arsenal, India and Pakistan appear to be engaging in an arms race to build up short-range tactical nuclear weapons, and hostility is ratcheting up between the US, Russia, and China.

“People should pay attention,” said Kristensen. “They have to be vigilant about holding their governments accountable, and make sure that the policies that are in place and the way they’re implemented are constructive, that they actually lead to improving the situation rather than making it worse.” A key US-Russia agreement to limit nuclear-armed missiles, known as the New START Treaty, is set to expire in February 2026, and the degraded relations between the United States and Russia will make negotiating a renewal much harder.

“The huge increase in US-Russian hostility will lead to increased risks of conflict and make it more difficult to work with Russia,” Bunn said. “Whether it’s working to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons to other countries or improving security for nuclear weapons and materials and facilities, all of that goes better if the United States and Russia are working together. And they’re not going to be doing that for some time to come.”

There is some good news, Bunn said. There are promising signs for the reinstatement of the Iran nuclear deal, which would affirm the principles of the Non-Proliferation Treaty. “It’s important to remember that only 5 percent of the countries in the world have nuclear weapons,” Bunn said. “Every other state has pledged to never develop nuclear weapons.”

For decades, Bunn added, about one in every 10 US lightbulbs was powered by uranium from decommissioned Russian warheads, which was sent to American nuclear power plants — a reminder that the world actively worked together to turn a tool of destruction into a force for good. “That’s remarkable,” Bunn said. “It’s never been true before in human history that the most powerful weapon available to our species was widely forsworn.”

People make their way to the border crossing with Poland in Mostyska, Ukraine, on Feb. 26, after Russia launched its invasion. (photo: Thomas Peter/Reuters)

People make their way to the border crossing with Poland in Mostyska, Ukraine, on Feb. 26, after Russia launched its invasion. (photo: Thomas Peter/Reuters)

Thousands more are still trying to get through the clogged borders, waiting in the cold for hours on end in cars or on foot with just the bare minimal belongings. As of Saturday, there was a nearly nine-mile backlog at the crossing into Poland, with some people waiting for 40 hours in 28-degree temperatures at night, according to a spokesperson with the U.N. refugee agency, Chris Melzer.

The scale of the exodus has not been seen in Europe in years. What could become Europe’s biggest humanitarian emergency since 2015 — when more than 1 million refugees mainly from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan arrived and triggered a continentwide crisis over whether to accept or reject those fleeing — is swiftly unfolding.

So far, European leaders and communities say they are ready to welcome Ukrainian refugees — including countries such as Slovakia, Hungary and Poland, which have previously hardened their borders and policies in the face of other waves of refugees amid a backlash from the far-right.

In contrast to 2015 when many European countries were hostile to sharing the burden of so many refugees, German Interior Minister Nancy Faeser said Sunday that Germany was ready to offer Poland and other Eastern European countries support to handle the sudden surge in Ukrainians.

Meanwhile, the situation keeps getting more grave: The United Nations warned Friday that up to 5 million of Ukraine’s 44 million people could become refugees if Russia’s attacks on Ukraine continue. It’s mainly women, children and the elderly fleeing — as males ages 18 to 60 are barred from leaving Ukraine after President Volodymyr Zelensky called on Ukrainians to take up arms and defend the country.

New challenges continue to emerge. A data-wiping software hit a Ukrainian border control station that was processing people fleeing the country into neighboring Romania on Friday, a cybersecurity expert at the checkpoint told The Washington Post.

“It’s massively hitting the border control,” said the expert, Chris Kubecka. “They are processing people with pen and pencil.”

In many cases, volunteers with locally funded food, clothes and warm rooms await those arriving.

“I see that there is a huge response from regular citizens,” said Polish women’s rights activist Marta Lempart, whose group, the All-Poland Women’s Strike, has in days gone from protesting abortion restrictions to organizing immediate shelter, food, medical care and other donations for Ukrainians arriving.

“We have calls [for donations] from all over Europe and the world,” she said. “We have to do this. Ukrainians fight for us and they fight for European human values.”

Poland, which has seen the biggest influx, pledged to set up reception centers along its 300-mile border to offer food, medical care and other resources. This month, thousands of soldiers from the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division deployed there to help with preparations.

Some 45,200 Ukrainian refugees crossed into Poland in just 15 hours Saturday, said Melzer of UNHCR.

“We will do everything to provide safe shelter in Poland for everyone who needs it,” Polish Interior Minister Mariusz Kaminski said Thursday.

Poland is already home to around 2 million Ukrainians, many of whom fled there after Russia’s 2014 takeover of Crimea and the start of the eight-year-long war in eastern Ukraine. The United Nations has estimated that another 1 million to 3 million Ukrainians could join them.

Other neighbors, such as Hungary and Slovakia, are sending troops to their borders to aid with the intake of refugees. In Romania, volunteers are similarly queuing to offer food and free accommodation. Ukrainians do not need a visa to enter these countries, as they can stay anywhere in the European Union’s Schengen Area for up to 90 days visa-free. (This agreement is set to change at the end of 2022.)

Ireland, which is not part of the Schengen Area, said Thursday that it would waive its visa requirement for Ukrainians. The first minister of Wales, Mark Drakeford, said his “nation of sanctuary” was ready to welcome Ukrainians.

Other governments, including Britain’s, have pledged to help Ukraine but have not loosened or clarified their immigration policies.

Ukraine is not a member of the European Union — the main alliance of European countries that Russian President Vladimir Putin considers an existential threat.

But Ylva Johansson, the European commissioner for home affairs, told Euronews on Wednesday that the E.U. was “quite well prepared” to absorb Ukrainian refugees as a matter of “unity” and “solidarity.”

“We are looking into the support from the E.U. asylum agency with processing asylum applications, the support from Frontex with registration and border management, and the support from Europol as well,” she said.

The Ukraine crisis has pushed some countries to reform their policies. While Austria did not accept Ukrainian refugees during the 2014 Crimea crisis, Austrian Chancellor Karl Nehammer said Thursday that he would welcome them in this time as a part of Europe — the very idea that Putin rejects.

“We are a European family, and families stand by each other,” he said.

Slovakian officials said Saturday that the country will provide monthly stipends to Slovakians who support and house displaced Ukrainians. Back in 2015, however, the country declared it would not accept Syrian refugees — unless they were Christian.

These kinds of disparities have frustrated refugee advocates, who have long criticized European leaders for pledging to support refugees while falling short on funding programs and maintaining often harsh, unwelcoming restrictions.

In recent years, European countries have aimed to stop — at times violently — the flow of largely non-White and non-Christian migrants and asylum seekers fleeing other conflicts and wars in the Middle East, Afghanistan and Africa.

In November, Poland forcibly denied entry to asylum seekers from the Middle East and Africa who became caught in a geopolitical standoff between Russia and Europe as they tried to enter from neighboring Belarus.

In 2015, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban built a fence to cut off one of the migrant routes. More recently, he supported a law making it a crime to help immigrants who entered Hungary illegally to apply for asylum.

Backlash to the influx of refugees in 2015 and 2016 emboldened the far-right in some European countries and led to a wave of anti-immigrant sentiment and policies.

Pakistani-American Zahir Jaffer convicted for murdering Noor Mukadam, the daughter of a former diplomat, arrives in court before the case verdict in Islamabad on February 24, 2022. (photo: Farooq/AFP)

Pakistani-American Zahir Jaffer convicted for murdering Noor Mukadam, the daughter of a former diplomat, arrives in court before the case verdict in Islamabad on February 24, 2022. (photo: Farooq/AFP)

Zahir Jaffer tortured and beheaded Noor Mukadam last July, in a killing that sparked massive outrage over violence against women.

The verdict, which was announced on Thursday, comes months after 27-year-old Noor Mukadam’s body was found in the home of Zahir Jaffer, the son of a prominent business tycoon, in July.

Police said Jaffer, 30, a Pakistani-American citizen, confessed to killing Mukadam for refusing his marriage proposal, although he later denied it. He was charged with raping, murdering, abducting and confining Mukadam, whose father is Pakistan’s former ambassador to South Korea.

“This case is for all the daughters of Pakistan,” the victim’s father, Shaukat Mukadam, told reporters outside the court after the sentencing on Thursday afternoon. “The society and media came to our side, the entire nation and the world was on our side.”

Jaffer was among 13 people indicted in October for their alleged involvement in Mukadam’s murder. Those indicted included Jaffer’s parents, his household staff and employees of a local rehab who had been called instead of the police after Mukadam died.

The police investigators who obtained footage from CCTV cameras installed in Jaffer’s house said shortly before her death, Mukadam tried to escape from Jaffer’s house by jumping from the second floor and fleeing through the main gate.

Unable to open the locked gate, Mukadam hid inside a watchman’s room next to the gate, the footage showed. Jaffer is later seen breaking into the room and dragging Mukadam back into the house. Her body was discovered by police shortly after.

On Thursday, Jaffer was sentenced to death by hanging. Two members from Jaffer’s household staff were given 10-year prison sentences on charges of abetting, confining a kidnapped person and withholding information about a plan to commit an offence.

Jaffer’s parents were acquitted from charges of aiding and abetting Mukadam’s murder. The rehab’s employees were also exonerated.

The case has captured the country’s attention for months and triggered widespread outrage and protests against instances of gender-based violence in Pakistan.

But while Jaffer’s sentencing has been widely welcomed, many have condemned the acquittal of his parents, who were in contact with their son over the phone during the night Mukadam was killed and were later charged with “hiding evidence and being complicit in the crime.”

Many have questioned whether the couple’s acquittal, in contrast to the sentences handed out to Jaffer’s employees, was the result of class discrimination. Without providing evidence, they have accused Jaffer’s parents of flexing their wealth and connections to manipulate the judgment in their favour. Some have expressed apprehension that Jaffer could eventually be acquitted through appeals or that he would get life imprisonment instead.

Lawyers representing Jaffer and his parents did not respond to VICE World News’ requests for comment.

According to the judgment, Jaffer’s parents were acquitted because of insufficient evidence. “There is no text message or transcript of the call to establish the actual conversation between the main accused and his parents,” read the court ruling. “Merely on the basis of telephonic connection alone…with their son it cannot be presumed that they passed on the instructions to kill Ms. Noor Mukadam or passed on the direction… to destroy the evidence.”

But as far as the verdict on the household staff is concerned, many believe that the power dynamic at play between the employer and the employees should have been taken into consideration.

“While the parents were acquitted based on the evidence that was produced in court, there should have been some nuance in the judgment around the house staff as well keeping in mind their class and that they had been under the influence of their employer,” lawyer Nighat Dad told VICE World News.

Pakistan has more than 8.5 million domestic workers, many of whom are overworked, underpaid and vulnerable to physical and psychological abuse from employers. Systemic poverty, class inequality, illiteracy and rarely-enforced legal protections collide to enable rampant employer-based exploitation.

“The trend that I have seen from law enforcement to the courts is a very different attitude towards people from the working class in comparison to people from the higher class,” Dad said. “This shows an internalised bias towards class in Pakistan which broadens this discrimination between working class and upper class folks.”

Buttons for the Krewe of Tradition based in Houma. (photo: Kezia Setyawan/NOPR)

Buttons for the Krewe of Tradition based in Houma. (photo: Kezia Setyawan/NOPR)

In 2020, the year before Mardi Gras parades were nixed due to the pandemic, city officials said more than 1,000 tons of trash were collected in New Orleans. For two groups — one based in New Orleans and the other Houma, the reduction of harmful trash post-parades starts with changing the throws.

New Orleans-based Grounds Krewe is one of several nonprofit organizations working to reduce trash and environmental impact caused by Mardi Gras festivities.

“It's basically a teaching moment, turning Mardi Gras from this huge embarrassing wasteful moment into a way to educate people about throws and what they could be and the vision for a local throw economy,” Davis said.

The group was formed in 2017 by Brett Davis, where they have expanded to multiple ventures including TrashFormers, a marching krewe that collects waste as they pass by parade crowds, to building a local throw catalog.

In collaboration with ArcGNO, GroundsKrewe volunteers are collecting throw donations and setting up recycling stations on parade routes this weekend.

“We found if we work the first weekend, people actually are still enthusiastic about keeping their throws,” Davis said. “But by the second weekend, they've seen so many parades, they're happy to donate stuff.”

Davis has seen the expansion in the group’s local throw catalog. This year, the group has sold over 17,000 individual throws to riders and various parades across the state, compared to 2020 when more than 2,000 food throws were sold.

“The interest has been really good considering that we're still sort of recovering from the interruption and cancellation from last year,” Davis said.

This year, the group prepared 1,000 throw packages for the Krewe of Iris, which rolls Saturday morning and is getting the first Krewe-branded collection of eco-friendly throws. Items include red beans, bamboo toothbrushes, jambalaya mix and more.

Davis, who said the group's throws are both functional and made by Louisianans, is hopeful to see more krewes and parades take part in the local throw economy.

In Houma, the Krewe of Tradition started in 2013 with the goal to revive the tradition of masquerading on Mardi Gras Day. The group will host their annual foot parade and costume contest on Feb. 27 in Houma and encourages all participants to come in costume and bring eco-friendly throws to hand out during this walking parade.

The group started handing out their signature pecan throws after it was suggested by longtime krewe member Sally Gautreaux, who suggested something local and plentiful to the area. Organizer Shannon Eaton said krewe members create each handmade throw to share with attendees.

“And we recently started attaching pin backs to them so that they’re wearable art and also magnets so that they're functional instead of just a pecan and that sits on your mantel or coffee table,” Eaton said. “We want it to actually have a function in the partygoer’s life.”

This year, the krewe has also been invited to speak at the Jazz Fest’s Folklife Village for their throws. Eaton said that the push towards an environmentally friendly carnival season is all just a part of a bigger trend in which more and more people are participating.

“I want people to know we didn't invent the concept of sustainable throws — we just jumped on the bandwagon,” Eaton said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.