Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Justice Elena Kagan’s dissent reads as strenuously as a vintage piece by, say, Clement Greenberg, slamming Harold Rosenberg.

The case, somewhat tedious to summarize in all its niceties, involves a 1981 photograph of the artist then still known as Prince taken by the photographer Lynn Goldsmith, which in 1984, during the Pop artist’s lifetime, was rather mechanically “Warholized,” with what basically amounted to eyeliner and a splash of paint, to illustrate a Vanity Fair article—and another of Warhol’s works based on the same photograph, which was licensed by his foundation, many posthumous years later, to Condé Nast (the parent company of Vanity Fair and The New Yorker), for use in a special-edition magazine published after Prince’s death. (Vanity Fair originally gave Goldsmith an artist-reference fee and a credit; on the second occasion, she was neither paid nor credited.) Goldsmith seems not to have known that Warhol had produced a series of works based on her own, aside from the agreed-upon 1984 Vanity Fair illustration. Did the Warhol redo of the Goldsmith portrait constitute fair use of an original image, or was it an unfair expropriation of someone else’s creativity for commercial ends? Justice Sotomayor, writing for the 7–2 majority, said, with surprising ferocity, that it was not fair use but copyright infringement, and so it needed to be paid for—exactly how much, and how the fee was to be assessed, remains to be decided.

Justice Kagan, speaking for a tenaciously aesthetic minority made up of her and Chief Justice John Roberts, awakening from the dogmatic slumbers in which he has dozed while his colleagues to the right strip away one minimal civil-rights protection after another, insisted that it was fair use—part of a fertile field of recycled images that make art art. Kagan’s dissent was not mild, either—it reads as strenuously as a vintage art-critical piece by, say, Clement Greenberg, slamming Harold Rosenberg—thus producing an image of two liberal Justices going hammer and tongs over brow-furrowing matters of aesthetics and the marketplace. Though some Court watchers will doubtless be disturbed by the absence of the traditional deference given by one Justice to another, others—given the tendency of the Court, on the right and dominant side, to use naked rationalizations for what are, transparently, previously arrived-at ideological diktats—will find the presence of actual argument enlivening. We live in an era of such ideological solidarity, for reasons good and bad, among people who are perceived to be on the same “side,” that any little peek of serious debate between them seems wholesome, not to mention welcome.

The two opinions certainly make for chewy reading, not least because the question of what is recycling and what is theft is one of the oldest and knottiest in the aesthete’s arsenal. A connoisseur of these things, with whom in a distant time I shared a bunk bed, has beautifully illuminated the subject from the specific view of what a working “appropriation” artist is to do now that appropriation has been put on warning. There will be some who feel that, if the decision stills the hand of the appropriation artist, it might not be wholly bad for the world’s store of beauty, appropriation being one of those things that may not be endlessly rewarding when placed in permanent rotation. John Cage’s famous composition “4’33”,” made up of silence, however interesting to contemplate in the singular instance, is, by definition, not necessarily super-rich in its echoing afterlife; an entire playlist made up only of ambient noise would be hard to endure. Similarly, having once had the Duchampian insight that a work of art might be whatever is deemed to be one, with a bicycle wheel or a urinal counting, if an artist decides so to decree it, one might not find it limitlessly entertaining if endlessly reproduced. In any case, appropriation tends to be judged appropriate as long as what’s being appropriated isn’t you, or yours. The aesthetics and the commerce of appropriation tend to bend to one’s interests of the moment. (I remember a famous appropriation artist of an earlier decade protesting the price of a knockoff modernist table, over a downtown dinner. “It wasn’t like it was original or anything,” she pointed out.)

Two additional knots might, however, be usefully braided around the subject. “Fair use” and “artistic expression” will remain much argued-over questions. But the concept of parody is one that, on the whole, seems easier to parse and is, perhaps for that reason, well supported by law. The Supreme Court itself, in 1994, allowed 2 Live Crew to replay riffs from Roy Orbison’s “Oh, Pretty Woman” to its own satiric ends. Justice Sotomayor’s opinion in the Warhol case cites that decision—Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.—and parody, generally, as a clear case of fair use, with the literal nature of the appropriation seen as essential to the satiric effect. So parody is privileged, and widely appreciated. Many for whom elements of Warhol will stick in their craw will have no difficulty delighting in Weird Al Yankovic, whose parodies depend on a strict deadpan fidelity to the originals that is, in many ways, Warholian. (In Yankovic’s parody of “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” almost every note and warble of the Nirvana original is reproduced; the brilliance resides in the self-referential lyric about Yankovic’s inability to understand what Kurt Cobain was singing about: “Now I’m mumbling / And I’m screaming / And I don’t know / What I’m singing.”)

And here one might find common ground between Justices Kagan and Sotomayor, if one accepts that the quality we think of as added artfulness in a borrowed image is almost always much closer to parody than to piety. Kagan writes, “Creative progress unfolds through use and reuse, framing and reframing: One work builds on what has gone before; and later works build on that one; and so on through time,” and she adds, “In declining to acknowledge the importance of transformative copying, the Court today, and for the first time, turns its back on how creativity works.” Though admirably erudite—it’s what an art historian would want a Justice to say—the analysis is perhaps a bit needlessly anodyne. The image of virtuous artists happily passing around pictures for general improvement belongs more to a progressive kindergarten than to the actual processes of art, which are more often moved by rancor, Oedipal drama, and competitive put-downs. The point of vital recycling is most often not to encourage communal creativity but to give a kick in the pants to the past. When Manet recycled a Raphael composition for “Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe,” he was not sincerely recycling a classic but mocking the dead hand of academic repetition. If there is a nod to Raphael in Manet’s picture, it is more in the nature of a wicked wink than a deep bow. Transformative copying transforms only when it has an edge, and that edge cuts.

In this light, Warhol’s early Campbell’s soup-can paintings and Brillo boxes can fairly be called—indeed, one understands them best if one sees them so—as parodies of the pretensions of high art as much as of the intensifications of advertising. Though Justice Sotomayor references a “commentary on consumerism,” that is not really what the invention of Pop art was most significantly about. What both Warhol and his contemporary Roy Lichtenstein were parodying in their work was the abstract and metaphysical ambitions of the Abstract Expressionist “action painting” that preceded them. By asserting the Whitman-esque thingness of the ordinary things that the Abstract Expressionists so strenuously rejected, Warhol and Lichtenstein were up to a kind of tense and subtle form of parody that, like all great parody, both mocks the source and flatters it by the attention paid.

Parody can, in other words, be a big thing. One need not get stuck on the Duchampian mechanical moves to support an idea of fertile and creative recycling in a comic-ironic mode, of a kind which is already seemingly secure in law. And here we may glimpse the bottomless ocean of potential parodic recycling that lies within the new domains of artificial intelligence. The reason that A.I. can do what it does is that it draws on a vast reservoir of other people’s inventions. If it can imitate Winslow Homer or Richard Avedon or any other artist—and it can—it’s because it has gained access to a lot of Homer and Avedon and didn’t ask first if it could. The harm done here is by the relentless scavenging of other people’s creativity in order to create a creativity, however ersatz or shallowly grounded, of its own. Comforting though it may be to see the new A.I. as essentially a parody of intelligence, it may also show us parody’s limits.

In that sense, Justices Kagan and Sotomayor may both be, so to speak, arguing over the architecture of sandcastles while a tsunami of artificial appropriation threatens to shortly wash them, and us, away. But, then, all aesthetics are an argument about the architecture of sandcastles. Or, as James Thurber put it—and let us, while repurposing his thought, politely name him as its initiator, or rather its imitator, since he had, as we all must sooner or later, borrowed the phrase from another—“the claw of the sea-puss gets us all in the end.”

READ MORE  Erdoğan at a rally in Sivas on Tuesday. (photo: Muhammed Selim Korkutata/Anadolu Agency)

Erdoğan at a rally in Sivas on Tuesday. (photo: Muhammed Selim Korkutata/Anadolu Agency)

The results come after one of the most hotly contested presidential elections in recent times for the influential NATO member.

Turkish public broadcaster TRT called the presidential election for incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

State-run news agency Anadolu’s vote count shows Erdoğan leading opposition candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu 52.11% to 47.89% with 98.52% of the vote counted.

"We have completed the second round of the presidential election with the favor of our nation," Erdoğan said following the tally. "I would like to express my gratitude to my people who made us live this democracy holiday. We will deserve your trust."

Erdoğan’s apparent triumph in the Turkish Republic’s centenary year comes after one of the most hotly contested presidential elections in recent times.

Voters went back to the polls for the runoff election after Erdoğan and Kilicdaroglu each failed to secure more than 50% of the votes in the first round of voting on May 14.

Although Turkey is a NATO ally and it holds elections, the country of 84 million has slipped further toward authoritarianism under Erdoğan and kept close ties with Russia.

Kilicdaroglu, the joint candidate of an alliance of opposition parties, vowed to reverse the country's tilt away from democracy.

It was the chance for change in a country where Erdoğan’s AK Party has been in power since 2002. Erdoğan, 69, became prime minister the following year and began serving as president in 2014.

Erdoğan had trailed in opinion polls that followed a campaign dominated by the fallout from the devastating earthquake this year and the country’s economic turmoil. But he led the first round of voting and only narrowly fell short of outright victory.

The steep cost-of-living crisis dominated the agenda, along with a backlash against millions of Syrian refugees as both candidates sought to bolster their nationalist credentials ahead of the runoff.

Kilicdaroglu has led the secular, center-left Republican People’s Party, or CHP, since 2010. He had previously said he intended to repatriate refugees within two years by creating favorable conditions for their return, but he subsequently vowed to send all refugees home once he was elected president.

Erdoğan, meanwhile, courted and won the backing of the nationalist politician Sinan Ogan, the former academic who was backed for president by an anti-migrant party but eliminated after finishing third in the first round of voting.

On the campaign trail, Ogan said he would consider sending migrants back by force if necessary.

Ahead of the first round, Erdoğan also increased wages and pensions, and subsidized electricity and gas bills in a bid to woo voters, while leading a divisive campaign that saw him accuse the opposition of being “drunkards” who colluded with “terrorists.” He also attacked them for upholding LGBTQ rights, which he said were a threat to traditional family values.

Turkey also held legislative elections on May 14, and Erdoğan’s alliance of nationalist and Islamist parties won a majority in the 600-seat Parliament. As a result, some analysts suggested this would give him an advantage in the second round because voters were unlikely to want a splintered government.

Kilicdaroglu, a soft-spoken 74-year-old, built a reputation as a bridge builder and recorded videos in his kitchen in a bid to talk to voters during the campaign.

His six-party Nation Alliance promised to dismantle the executive presidential system narrowly voted in by a 2017 referendum. Erdoğan has since centralized power in a 1,000-room palace on the edge of Ankara, and it is from there that Turkey's economic and security policies and its domestic and international affairs are decided.

Along with returning the country to a parliamentary democracy, Kilicdaroglu and the alliance have promised to establish the independence of the judiciary and the central bank, institute checks and balances and reverse the democratic backsliding and crackdowns on free speech and dissent under Erdoğan.

The results will have myriad ramifications outside Turkey, which enjoys a strategic location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. Despite being a NATO member, the country has maintained close ties with Russia and blocked Sweden’s membership in the Western military alliance.

Turkey boasts NATO’s second largest armed forces after the U.S., it controls the crucial Bosporus Strait and it is widely believed to host U.S. nuclear missiles on its soil.

Together with the U.N., Turkey brokered a vital deal that has allowed Ukraine to ship grain through the Black Sea to parts of the world struggling with hunger.

READ MORE  Senator Sheldon Whitehouse: 'The ethics reporting law that is at the heart of the Clarence Thomas ethics reporting scandal is a law passed by Congress.' (photo: Shutterstock)

Senator Sheldon Whitehouse: 'The ethics reporting law that is at the heart of the Clarence Thomas ethics reporting scandal is a law passed by Congress.' (photo: Shutterstock)

Democrat Sheldon Whitehouse insists legislature has power to make justices follow ethics code but ‘It is not going to be easy’

“It is not going to be easy,” Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island told NBC’s Meet the Press in an interview to be broadcast on Sunday. “The work that we’re doing on ethics in the court ought to be easy. And yet it’s not. It’s partisan also.

“So I think that the first step is going to be for the judicial conference, the other judges, to put some constraints around the supreme court’s behavior and treat the supreme court the way all other federal judges are treated.”

Supreme court justices are nominally subject to federal ethics laws but in practice govern themselves.

Thomas has said he did not declare gifts from Crow including luxury travel and resort stays, a property purchase involving his mother and school fees for a great-nephew because he was informally advised he did not have to. He has said he will do so in future.

Observers have said Thomas clearly broke ethics laws. Democrats have called for Thomas to resign or be impeached, the former unlikely, the latter a political non-starter.

Crow denies wrongdoing and claims never to have discussed with Thomas politics or business before the court. The Guardian has shown Crow to have had business before the court during his friendship with Thomas.

Crow has also donated to groups linked to Ginni Thomas, the justice’s far-right activist wife who supported Donald Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 election.

Whitehouse’s NBC host, Chuck Todd, said: “It’s pretty established Congress can’t [impose ethics law on the supreme court], right?”

The senator said: “No, it absolutely can.”

Todd said: “Well, it doesn’t mean it’s constitutional.”

Whitehouse said: “Yes, it does. It means it’s constitutional because the laws that we’re talking about right now are actually laws passed by Congress. The ethics reporting law that is at the heart of the Clarence Thomas ethics reporting scandal is a law passed by Congress.”

Todd repeated the argument about separation of powers, between the legislature (Congress), executive (presidency) and judiciary, which lawyers for Crow and Roberts himself have cited in refusing to cooperate with information requests from the Democratic-run Senate judiciary and finance committees.

Whitehouse, a member of both panels, countered: “Certainly we can do the administrative side of judicial … I’ll be the first one to concede, if there’s a case in the judicial branch of government, we in the Congress have nothing to say about it.

“But in terms of administering how the internal ethics of the judicial branch are done – heck, the judicial conference which does that is a creation of Congress.”

The senator also called the Roberts court a “fact-free zone as well as an ethics-free zone”.

Referring to suggestions justices should pledge to observe ethics laws during the confirmation process, Whitehouse said: “We saw how the pledges on Roe v Wade went in the confirmation process.”

Roe, the 1973 ruling which guaranteed the right to abortion, was last year struck down by a 5-4 majority, all three justices appointed by Donald Trump (Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett) voting in the majority.

In the words of Factcheck.org: “A close examination of the carefully worded answers by the three Trump appointees … shows that while each acknowledged at their hearings that Roe was precedent, and should be afforded the weight that that carries, none specifically committed to refusing to consider overturning it.”

Whitehouse continued: “You get on to the court, and there you are, and there’s no process for determining what the facts are. That’s part of the problem here.

“When Justice Thomas failed to recuse himself from the January 6 investigation that turned up his wife’s communications [with Trump officials], he made the case that that was OK because he had no idea that she was involved in insurrection activities.

“That is a question of fact. That’s something that could have, and should have, been determined by a neutral examination. And so the problem with the supreme court is that they’re in a fact-free zone as well as an ethics-free zone.”

Whitehouse has campaigned against so-called “dark money” in US politics. Asked if he trusted the federal court system to be fair and impartial, he said: “Usually, I think the trial courts are very strong.

“I think … we’ve seen honest courtrooms make amazing differences with Dominion v Fox, with the parents at Sandy Hook against the creep who was pretending that their children’s murder wasn’t real, and now with the judgment against Donald Trump.

“So honest courtrooms are really important to cut through to the truth. When you get to the supreme court, if it’s an interest in which the big rightwing billionaires are concerned, [it’s] very hard to count on getting a fair shot.”

Asked if he was saying donors like Crow dictated how justices voted, Whitehouse said: “That would be what the evidence suggests.

“I think the statistics are pretty stunning at how often the judges who came out of the Federalist Society” – a conservative group which works to shape federal nominations – “do what they’re told by the amicus groups that come in on behalf of the right wing.”

READ MORE  Vendors sell various goods to shoppers at 'the Thieves' Market' in Baghdad. (photo: Claire Harbage/NPR)

Vendors sell various goods to shoppers at 'the Thieves' Market' in Baghdad. (photo: Claire Harbage/NPR)

The last time we were here, as the Iraq War droned on almost 20 years ago, Westerners could scarcely go outside without becoming a target. Today, not even a hard glance. We've come to find a piece to the puzzle we've been trying to solve.

We've been investigating a horrible incident from April 2004 that killed two Marines and an Iraqi man when a mortar was accidentally dropped on a schoolhouse in Fallujah.

The Marines knew almost immediately it was an accidental case of "friendly fire" — the deadliest such Marine-on-Marine attack in decades — and they opened an investigation. But the families of the dead Marines were told it was enemy fire and didn't get the truth for three years. It seems the son of a prominent politician — Marine 1st Lt. Duncan D. Hunter — was involved in the mishap. His father, Duncan L. Hunter, was chairman of the powerful House Armed Services Committee at the time. Rather than tell the truth, the Marine Corps buried the report of its investigation for years.

But that report? It never even mentions the death of a third man, an Iraqi man named Shihab. His family still didn't know the truth.

Just finding Shihab's name was a challenge. The Marines wounded that day in Fallujah hardly knew him, because Shihab was there working with an Army psychological operations team, which drops leaflets and broadcasts messages, trying to assist the local population and irritate the insurgents. We eventually found one of those Army soldiers, Duane Jolly, who described his fond memories of Shihab.

Jolly recalled how Shihab refused to repeat some of the Army team's messages, the ones with rough language or sexual content.

"He was quite devout," recalls Jolly, a retired sergeant major. "He was like, 'I wanna help you in every way, but I'm not gonna lower myself, in the eyes of my God.'"

Shihab was Shia, and Fallujah was a Sunni area, turning more violent with al-Qaida moving in. He was nervous about going there. Jolly convinced him it would be OK.

"I told him, 'Don't worry buddy. You know, if people start shooting at us, you just get behind me. I guarantee I'll take care of you.' And that's the part, you know, of therapy that I still have a hard time with and still do."

Awadh al Taei, from NPR's Baghdad office, spent months tracking down Shihab's family. We gave him a photo of Shihab. He went to hospitals, the morgue, government offices. Finally he went to a neighborhood food store, where the manager thought he knew the family and said he would contact them. Soon after, a young man showed up, kind of nervous. Awadh showed him the picture, and the young man pulled a similar one from his wallet and started to cry. It was Shihab's youngest brother, Arkan.

The family lives in an apartment behind a mechanic's garage in the city. And when we came to Baghdad, Awadh arranged for Arkan to come to our hotel. It was kind of an audition. He wanted to check us out.

When he arrives, Arkan is clearly nervous and edgy. He glances around the lobby of the upscale hotel at the passing businessmen, wonders if he's being watched. He's clearly worried about neighbors seeing Westerners visit the family home.

"I'm scared. I'm terrified about the situation," Arkan tells us.

Interpreters like Shihab are essential when American troops operate around the world. Not only do they help Marines and soldiers understand the language, they also help them avoid cultural mistakes, taboos. And they often can save American lives, telling them what neighborhoods to avoid or when to take extra precautions, maybe preventing a gun battle by soothing an angry tribal sheikh.

But there are still bitter sectarian divisions in Iraq and lingering anger at those who worked for the Americans. Arkan says the family has had to move a dozen times since Shihab died, fearful of neighbors, of rumors, of whispers that will force them to flee again.

Arkan said that as a teen he was badly beaten by militia members because of his brother's work. Some Iraqis see them as sell-outs, even traitors. That's why we're not using Shihab's surnames. Even today, his family is in danger because of his work with the Americans.

Arkan calls the next morning and tells us we can come to the family home to talk with him, his older sister, who is the matriarch of sorts, and a younger sister, Aliaà — but only after dark, when the mechanics who work in the attached auto shop have left. He tells us to keep a low profile.

The neighborhood we're headed to is in southern Baghdad. Early in the war, it was pretty much a no-go zone — a mixed neighborhood of Sunni and Shia that descended into sectarian clashes. This area was once a launching zone for rockets fired toward the government buildings and embassies in what was called the Green Zone.

We slip into the auto repair shop. Arkan is there, smiling, and leads us through to the back, squeezing between a tool bench and a white car with its hood up. We walk out a back door and along a dimly lit walkway, to another building in the back of the garage. He invites us into a bright sitting room with whitewashed walls, high ceilings and couches set along three sides.

As we're settling in, and they bring cups of tea and trays of baklava, the older sister, Nidhal, is talking with Awadh. He's explaining why we're here, and they're becoming more and more animated.

Nidhal and Awadh talk back and forth in a flurry. Awadh finally tells us that Nidhal wants to know if her brother was killed by the Americans. We tell her yes, that's why we're here, that Shihab's death was all a mistake. She's shocked. Nidhal says Shihab's death caused them incredible hardship. She's had to work as a housekeeper and take care of sick people to make ends meet.

We tell them about the Marines who were killed, about the friendly fire incident, about how we spoke with the families of the dead, and how a widow of one of those dead Marines, Elena Zurheide, shared her copy of the investigative report. We tell them the American families were all lied to as well.

And we tell them how we tried for more than a year to get a name for Shihab, until we found the Army psychological operations soldiers who worked with him at the schoolhouse. We tell them how the soldiers told us that as they dressed Shihab's wounds, shortly before he lost consciousness, he spoke of his family and how proud he was of them.

Nidhal bows her head and sobs.

Nidhal tells us their mother died when the kids were little. Their father was an intelligence officer. But eventually, he became disillusioned with Saddam Hussein's regime and came under suspicion. She says he was assassinated by Iraqi agents in Dubai, leaving the children — four boys, two girls — all on their own.

In this family of orphans, the two eldest became like mom and dad, she says. Nidhal worked to help Shihab finish college — then he became the main breadwinner. After the invasion, he signed up as an interpreter for the Americans.

Nidhal tells us that when the Americans first arrived, they all loved them. Shihab would bring the family to the train station to see the U.S. soldiers.

Shihab did much for the family, they say. Arkan says Shihab taught him taekwondo and chess. He showed them woodworking and made them little toys. And he taught them all how to swim — he'd take the whole family down to the river.

The youngest, Aliaà, tells us Shihab insisted they all study. He had a small library and if they finished a book, he would reward them, let them watch cartoons on his computer or from a DVD.

The family desperately needed the money Shihab got as an interpreter, which Nidhal tells us was good money. He planned to buy the family a house one day.

Nidhal said the last time she saw him was in early April of 2004, shortly before he left for Fallujah.

"We stayed up late talking. But then, when he told me he was going to Fallujah, how the situation was escalating, an ominous feeling rose up," Nidhal says. "I told him this might be our last farewell. Three days after he went away, I had a dream. Shihab was there and he told me, 'They're sending me to Arizona.' And I asked him, 'Why Arizona?' And he told me, 'Because it's beautiful over there.'"

The day that American soldiers in armored vehicles arrived in their neighborhood looking for Shihab's family, the neighbors wouldn't say anything, fearful of talking with the Americans. But then a friend of Shihab's told them he was killed and they must retrieve his body from the morgue.

The family buried Shihab in the holy city of Najaf. Afterward, Nidhal and the oldest brother were asked to go to the Green Zone to meet with an American general. She doesn't remember his name but says he was heartbroken and started to tear up, telling them Shihab was killed by "terrorists."

The officer gave them Shihab's clothing and possessions, a certificate of appreciation for his service to the American military on behalf of Maj. Gen. James Mattis — then the Marines' ground commander in Iraq — and $9,000 in cash.

At that time, families of U.S. service members received a "death gratuity" of $100,000. And most got a $250,000 insurance payout.

Then Shihab's family members tell us something surprising, kind of tragic. Another of their brothers, Ammar, went to work for the Americans after Shihab was killed. He did it to avenge his brother. They say Ammar moved to the U.S. more than a decade ago. They think he's still working with the American military, but they haven't heard from him for two years.

We hand them a copy of the investigative report. Arkan can read English, but we had the summary translated to Arabic. We tell them, again, it was all a mistake.

Arkan becomes more and more angry, starts to yell in broken English. Why did the American officer say Shihab was killed by terrorists?

"Why he didn't tell the truth?" Arkan says. "Why he a liar to us? That I want to know. Why he's a liar to us."

We tell them the American families were lied to as well. The families of the dead Marines, Robert Zurheide and Brad Shuder, were initially told it was hostile fire, and heard rumors of friendly fire within weeks. And they learned the truth three years later after the Marines were called to Capitol Hill and were forced to tell the truth in congressional hearings.

But Shihab's family has been living with a false story for nearly two decades. Nidhal tells us she always stood up for the Americans when Iraqis would speak badly about them. She said she had a deep faith that the American soldiers were more honorable than Saddam and Iraqi politicians, saying the Americans "rid us of so much agony and suffering."

"I felt that way right up until this moment," she says. "I was such a fool. I was so wrong."

We talk for a while longer, answer what we can. We're surprised when, despite all the anger and disappointment, Arkan tells us he still wishes he could move to the U.S. someday.

They ask if we have any advice for them, how they might approach the American government for more help, maybe a job for Aliaà or Arkan. Aliaà says when Shihab died, "we lost both spiritually and financially." We tell them that's a question for the American Embassy.

The U.S. Embassy in Baghdad wouldn't comment for this story, suggesting we reach out to officials who were at the embassy back in 2004.

READ MORE  Corky Cochran, fire chief of the Livingston Volunteer Fire Department. Blocked crossings can hamper response times for ambulances and the fire department. (photo: Lee Powell/WP)

Corky Cochran, fire chief of the Livingston Volunteer Fire Department. Blocked crossings can hamper response times for ambulances and the fire department. (photo: Lee Powell/WP)

Nationwide, longer and longer trains are obstructing rural intersections, preventing paramedics from getting to emergencies, including a baby who died after his mom waited and waited.

For decades, those living along Glover Road in Leggett, Tex. — a rural community with fewer than 150 residents about 80 miles from Houston — wrote letters, sent emails and called authorities pleading that trains stop blocking the neighborhood’s sole point of entry and exit for hours. Some residents and a county judge sent letters addressed to the railroad company, warning of a “greater catastrophe,” including a toxic train disaster.

“Should there be a derailment … we would be dead ducks, having no evacuating route,” Pete Glover, the man whom the street is named after, wrote in a 1992 letter to the railway company. “If some home caught afire,” he added. there’d be “no way for firetrucks to serve them.”

To many in the community, their worst fears were realized in 2021, when baby K’Twon Franklin died. His mother, Monica Franklin, had found the 3-month-old unresponsive in her bed the morning of Sept. 30, and called 911.

Paramedics responded, but a Union Pacific train blocked their path on Glover Road, according to Franklin and a local police report. It took more than 30 minutes for them to carry K’Twon into an ambulance. Two days later, the baby died at a hospital in Houston. “Unfortunately, the delay has cost my child’s life,” Franklin, 34, told The Washington Post.

Over the past decade, rail corporations have been running more lengthy freight trains — some as long as three miles — partly to save fuel and labor costs. As they do, they are blocking rural and urban intersections, stoking anger and contributing to tragedies and calamities.

Much of the nation’s focus has been on a long Norfolk Southern train that derailed in East Palestine, Ohio, in February, sparking a toxic fireball and prompting state and federal investigations. But while Congress has shown some renewed concern about rail safety, there has been little focus on an everyday safety threat — long trains blocking first responders from getting to emergencies.

It is happening across the country. In Tennessee, a man died of a medical emergency after an ambulance crew was held up at a train crossing. In Oklahoma, a man perished from a heart attack after first responders were stuck behind a train at the only entrance to their street.

Since 2019, the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) has operated a digital portal where citizens can report obstructions caused by trains. So far this year, there have been more than 1,400 reports of first responders blocked by trains. There have also been documented cases of frustrated pedestrians crawling under stopped trains, only to be injured or killed when the train starts moving.

In Texas, K’Twon’s mother has filed a lawsuit against Union Pacific, claiming its routine blockage of the Glover Road intersection prevented paramedics from reaching her child, thereby causing his death. In response, the railway company has offered its sympathy and said it is working to resolve problems at intersections in Leggett and other communities.

“Our hearts go out to K’Twon’s family on this tragic situation,” the company said in a statement. “Union Pacific is in the early phases of litigation discovery, investigating the overall factual timeline, including whether the presence of a train had any impact on first responders’ ability to revive K’Twon. We understand the impact blocked crossings have for community residents and work diligently to reduce the amount of time trains occupy the crossing.”

Many residents of Leggett put little stock in such pledges.

Schools superintendent Jana Lowe is one of several local leaders and residents who have been writing and calling Union Pacific for years, warning that obstructions at the Glover Road crossing — such as school buses delayed for hours — could lead to something more horrific.

“I fairly believe that this cost a child’s life, that they weren’t able to get there on time,” she said. “It’s heartbreaking. It could have been avoided.”

In his 25 years as a locomotive engineer, Eddie Hall saw his trains grow longer and longer. He can recall when they were just over a mile in length. Before going on leave last winter, he was driving a three-mile-long Union Pacific train with as much as 18,000 tons of mixed freight on his regular Tucson-to-El Paso route.

He has seen his line of freight cars disrupt traffic for hours in small and rural towns, he said adding that in Tucson, trains can block the downtown’s four railroad crossings for as long as an hour.

“Whatever they block, they block,” said Hall, who now leads the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen. “The carriers really don’t take into consideration how long we sit on rail crossings.”

Trains have mushroomed in length for a simple reason — to save money and generate profits for railway companies and their shareholders. Roughly two decades ago, activist investors started pressuring railway corporations to become more efficient by reducing labor and fuel costs. So railroads adopted an operating model that cut crews and consolidated trains, known as “precision scheduled railroading.” By using longer trains, rail companies are operating fewer shorter trains, increasing fuel efficiencies and decreasing costs and their carbon footprints, industry officials say.

It has paid off. BNSF Railway and Union Pacific, the two largest railroad corporations in the nation, have reported record earnings in recent years. U.S. railroads have paid out $196 billion on stock buybacks and dividends to shareholders since 2010.

Rail industry officials say the use of longer trains has also helped improve safety, and they point to an overall decline in derailments. But in the aftermath of the East Palestine spill, federal regulators have warned that long trains deserve closer review and can contribute to derailments.

About 1,000 trains derail annually nationwide, according to the FRA, including a spate this year.

After the Ohio incident, a train derailed on the Swinomish Reservation in Anacortes, Wash. in mid-March, spilling diesel fuel. Also in March, a train passing through Springfield, Ohio, went off its tracks — prompting a shelter-in-place order — and a small town in Minnesota was evacuated after a train carrying ethanol derailed and caught fire.

An FRA advisory last month urged railroads to make sure that engineers are adequately trained to handle long sets of freight cars and that locomotives don’t lose communication with devices at the end of trains that can help trigger the brakes in an emergency. Federal regulators also highlighted safety risks associated with blocked crossings, particularly how stopped trains can impede access to emergency services.

The FRA’s recommendations stopped short of mandating limits on train sizes, which some labor unions and local communities have demanded. Members of Congress and state lawmakers in at least five states have proposed establishing length restrictions in the wake of the Feb. 3 Norfolk Southern derailment in Ohio. In that incident, federal investigators have said that an overheating wheel bearing led the 149-car train to derail. The train’s length, approximately 1.8 miles long, has not been identified as a potential factor.

Union Pacific CEO Lance Fritz said in an earnings call last month that accident data doesn’t show that long trains are riskier. He said that since 2019, train length is up by about 20 percent in his railroad’s network, while mainline and siding derailments are down by 26 percent.

“There’s zero corollary between train length and derailments,” Fritz said.

Labor unions, however, say longer trains tend to require more maintenance because greater stress is placed on the equipment, and they cause greater conflicts in communities.

“When you have first responders trying to get from one side of the track to another, in a small town like that, you’re putting the public safety at risk,” Hall said.

Leggett, an hour north of Houston, is an unincorporated community surrounded by farms and cattle ranches, a part of the Gulf Coastal Plain once carpeted by vast timberlands. At one point, there were as many as 20 sawmills in the area, and the railroad was at the center of the region’s early economy, delivering pulpwood to a paper mill near Houston.

These days, the residents of Glover Road, a mile-long dirt road bordering the train tracks, receive little benefit from the railroad, and must cope with some hazards. Long trains carrying ethanol, fertilizers and other chemicals stop at a nearby switching station multiple times a day, often blocking the single crossing that connects Glover Road and its two dozen homes to the rest of Polk County.

“One time they sat there for three hours,” recalls Kathy Crowhurst, a resident of 18 years who owns the Good Ol’ Daze retirement community. She said her tenants — ages 55 to 98 — have had to cancel doctor’s appointments or wait on the other side of the tracks to get home. Schoolchildren are often late to class when the train blocks school buses.

In 2021, a train blocked a firetruck on its way to a house fire on Glover Road, said Corky Cochran, chief of the Livingston Volunteer Fire Department, which includes Leggett in its territory. Fortunately, another truck had already made it to the scene and they didn’t need more water. Good luck, Cochran said, “or the fact that God has been on our side.”

Another scare came on Jan. 19. That night, Crowhurst’s fiancé Pete suffered a stroke and her 911 call coincided with a train pulling into town.

“We waited and waited,” said Crowhurst, with no help showing up just after 8 p.m. Finally, she saw flashlights and two paramedics hurrying across the tracks and the half-mile stretch to her house.

It took about 30 minutes for the emergency crew to get him to the hospital. Her fiancé, who was battling brain cancer, survived the stroke, but Crowhurst said it was a dangerously close call.

Trains block the Glover Road crossing several times a day, and are unpredictable in their timing and duration, residents say. Trains on the main single track pull to a siding track so one coming in the opposite direction can go through. That was the cause of the obstruction that prevented paramedics from quickly reaching baby K’Twon, Union Pacific said in a statement.

Every time there’s an incident, Crowhurst, 65, notifies Polk County Judge Sydney Murphy, who sends an inquiry to the railroad. Murphy said residents have been pleading for relief for decades, while she has been asking Union Pacific to help with at least one road option that would improve access for residents on the wrong side of the tracks.

The solution would be to build a short connector road to another crossing, giving Glover Road residents a way out. They could then cross the tracks and drive 15 minutes to Livingston, the nearest town. Or if all crossings were blocked in Leggett, they could take the long way to Livingston, about a 45-minute drive.

In its statement, Union Pacific said it is committed to working with communities — including Leggett — to resolve issues with blocked crossings. But local officials and residents say that, despite the county and state facilitating land acquisition, the railroad has not made it a priority.

“They’re so slow-moving and now we have a deceased baby,” Murphy said.

Along with nagging concerns about safety, many in Leggett say they’ve lost the most basic of liberties — the freedom to move around. Simple everyday errands — such as a trip to the dog groomer or a visit to the doctor — generate uncertainty.

Joyce Davis, 76, who has lived in the community her whole life, said she has friends who are hesitant to visit, fearing they will get stuck by a blocked train. She hears it so often, she said, it has become a running joke.

“Don’t come over here on your lunch hour, just in case,” she said she tells her friends.

Like many of her neighbors, Franklin had repeatedly called Union Pacific to report trains blocking Glover Road, the only way in and out of the trailer where she lived at the time with her two daughters, her then-partner and K’Twon. She said she had prayed for a baby after years of being told she could not have more children.

Sometimes, Franklin said, a stopped train would prevent the school bus from picking up or dropping off one of her daughters. Her complaints to Union Pacific, Franklin said, went unanswered.

She remembers having a conversation about train delays with Lowe, the schools superintendent, just before the worst day of her life, Sept. 30, 2021.

That morning, after leaving her bedroom, Franklin returned to check on K’Twon, she said. But the curly haired baby didn’t move when she touched him. Alarmed, Franklin, a registered nurse, checked for his pulse. He still had some color on his face, Franklin recounted. She called 911 and started to perform CPR while talking to the operator.

The operator instructed her to continue until help could arrive. But when paramedics found their path blocked by a train, they were forced to crawl under the train cars, according to a Polk County Sheriff police report, and Franklin grew increasingly desperate.

She ran toward them with the baby in her arms. There, on a cross tie, Franklin and a paramedic continued CPR for several minutes, she said.

Finally, the train moved on and paramedics were able to hustle K’Twon into their ambulance, more than half an hour after Franklin had called 911, she said.

When he died two days later, Franklin was grief-stricken and angry. Later, she made plans to move her family far away from Leggett.

“I can’t live close to a train track,” she said, adding that even the sound of a train horn haunts her.

As public concern mounts over derailments and blocked crossings, state and federal leaders in both parties are calling for tougher regulation of railway companies.

After the toxic disaster in Ohio, two Republican U.S. senators, Marco Rubio of Florida and J.D. Vance of Ohio, sent Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg a pointed letter. In it, they questioned why the federal government wasn’t doing more to police railroads that are “moving more freight with fewer workers.”

“It is not unreasonable to ask whether a crew of two rail workers, plus one trainee, is able to effectively monitor 150 cars,” the senators wrote in their Feb. 15 letter.

The Railway Safety Act, which would require railroads to maintain a toll-free number where people can report blocked crossings, advanced this month to the Senate floor, where it will probably need 60 votes to pass. The legislation also would set standards for trackside safety detectors, apply new rules to trains transporting hazardous materials and curb efforts by railroads to reduce their workforces.

On the state level, at least five legislatures — in Arizona, Iowa, Missouri, Virginia and Kansas — were reviewing bills this year to restrict train lengths. Most are looking at restricting the length of trains to 1.6 miles.

It is still an open question, however, if states hold the legal authority to regulate railroads, which have long enjoyed protection under the 1887 Interstate Commerce Act.

Last year, for instance, the Ohio Supreme Court struck down that state’s law that set a five-minute limit on how long stopped trains can block crossings. The court ruled that federal law preempts such state restrictions.

In response, the attorneys general of 18 states and the District called on the U.S. Supreme Court to affirm state authority to regulate blocked railroad crossings “in the interest of public safety.” It is not known whether the high court will take the case.

In March, the U.S. Supreme Court invited the federal government to offer its position on whether state and local governments can regulate how long trains can block railroad crossings. It could be at least the fall before the nation’s highest court decides whether to take the case.

In the meantime, the FRA says it is working with the National Academy of Sciences on a study of trains that are longer than 7,500 feet. The study — mandated by Congress in the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure deal — is expected to be complete later this year, as is a report the FRA is preparing for Congress on blocked intersections.

The agency’s database of rail crossing complaints provide a snapshot of what communities are facing: “Late for work, lost wages,” reads one complaint from Villa Grove, Ill. “Students can’t get to school,” someone reporting up to 2 hours of delays in Keyser, W.Va., said. “Local businesses are unable to work,” said another in Los Angeles.

The FRA said it has not investigated specific instances in which blocked crossings delayed emergency response, saying those cases would be a matter for local officials and law enforcement. It says that it “continues to encourage railroads to prevent and minimize adverse impacts caused by blocked crossings.”

The Association of American Railroads, which represents the industry, says limiting train length to 7,500 feet, as some state lawmakers have proposed, could increase U.S. freight train fuel consumption by about 13 percent. The solution, the industry says, is to work with communities to minimize the frequency of blocked crossings. The association says crews are trained to reduce the occurrence of blocked crossings, and dispatchers are alerted when crossings are blocked and have authority to address obstructions. But with more than 200,000 grade crossings across the United States, some impacts are inevitable, the industry says, citing those as the trade-off of transporting goods.

“Railroads are aware of their impact on communities, particularly grade crossings, and sympathize with those who may be affected by train movement,” the AAR said in a statement. While the association declined to comment on specific cases where blocked crossings delayed first responders, it added that shipping goods by rail reduces freight truck shipments, thereby reducing congestion on roads and highways.

In Leggett, Walter Peden recently surveyed his family’s old homestead, which burned down years ago, along with many other homes nearby, including his wife’s grandmother’s house, which he said caught fire last year.

Train blockages did not contribute to firefighter response to any of those blazes. Still, Peden is somewhat resigned to the fact that trains will block fire crews and paramedics from reaching his property and others on Glover Road. “Trapped,” he said, describing how he feels.

Not everyone is giving up.

Murphy said she’ll keep lobbying for a fix to the Glover Road crossing. She concedes, though, that small communities lack the funding and clout to get infrastructure built quickly, even when the public is at risk.

“It’s extremely concerning, not just for me, not just for Polk County, but across the entire United States,” Murphy said. “In rural communities you can’t just say, ‘We’ll go to the next crossing’ because there is no next crossing.”

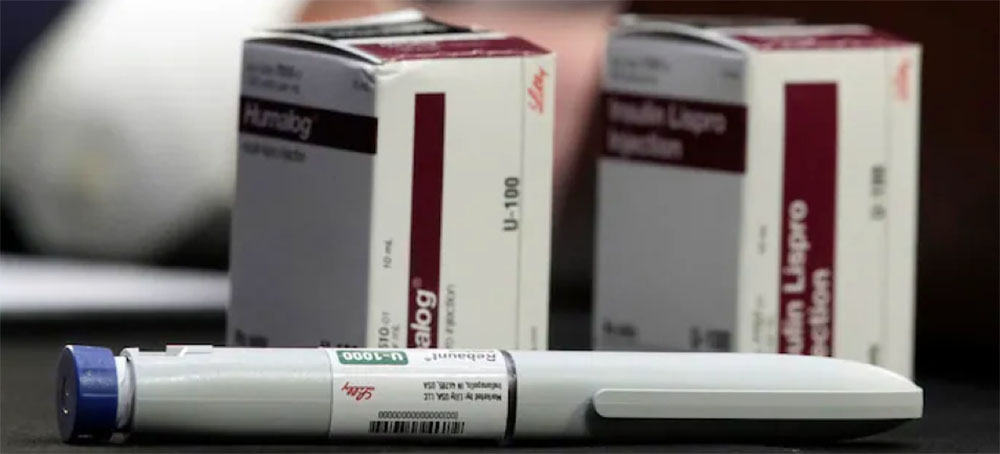

READ MORE  Insulin. (photo: Carolyn Kaster/AP)

Insulin. (photo: Carolyn Kaster/AP)

The money will go into a fund that insulin users can tap into if they don’t qualify for the $35-a-month cap

Under the settlement, those unable to qualify for the $35-a-month cap ― people who no longer use Eli Lilly insulin or those now enrolled in the Medicare and Medicaid programs ― may tap into the $13.5 million fund, which is also being used to pay administration costs and fees for the plaintiffs’ attorneys.

About 7 million Americans use insulin daily to treat their diabetes, but the prices of the four most popular types have tripled over the past decade, according to the American Diabetes Association.

Attorneys for the insulin buyers said some users gave accounts of resorting to extreme measures to afford insulin, including starving themselves to control their blood sugar levels and intentionally slipping into ketoacidosis, a serious complication of diabetes, to receive insulin from hospital emergency rooms.

A 2022 study in the Annals of Internal Medicine estimated that 1.3 million Americans ration their insulin because of the cost.

“We are incredibly pleased to culminate this important case and over six years of hard-fought litigation on behalf of millions of individuals who rely on insulin every day,” said James Cecchi, of the firm Carella Byrne, who served as co-lead counsel for plaintiffs in the lawsuit.

The settlement still must be approved by the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey.

“The settlement contains no admission of liability or wrongdoing by Lilly,” a company spokesperson said, adding that “the agreement is a reflection of our continued commitment to close gaps in the U.S. health-care system for people with diabetes.”

In March, Eli Lilly announced that it was cutting the price of its commonly prescribed insulin by 70 percent.

The class covered by the lawsuit includes “anyone in the U.S. who paid any portion of the purchase price for any Lilly insulin product, for themselves or on behalf of any family member of dependent” from Jan. 1, 2009, up to the final approval order for the settlement. Under the agreement, eligible insulin buyers would be able to obtain and file claims forms on the settlement website.

Upon preliminary approval of the settlement, attorneys for the plaintiffs plan to serve subpoenas to the six largest pharmacy benefit managers and the seven largest retail pharmacy chains in the United States to gather the “transactional data” that will be used to verify settlement claims.

Between the $13.5 million settlement and the four-year cap, “our experts calculate that this will save these consumers $500 million in payments for their insulin over the four-year period,” said Steve Berman, the court-appointed co-lead counsel for the insulin buyers in the lawsuit.

READ MORE  Alan Robertson looks out over the dunes on Tybee Island, Georgia. He is a consultant who helped the city acquire grant money to repair the dunes. (photo: Emily Jones/Grist)

Alan Robertson looks out over the dunes on Tybee Island, Georgia. He is a consultant who helped the city acquire grant money to repair the dunes. (photo: Emily Jones/Grist)

How advocates are helping understaffed communities field complicated federal grants.

The small barrier island’s stormwater system, fed by storm drains across the coastal community, funnels into a pipe that comes out on the beach at the southern tip of Tybee. But that pipe gets regularly buried by sand.

“What happens is when it gets covered with sand, and the tide rises, there’s nowhere for the stormwater to go,” said Alan Robertson, a Tybee resident and consultant for the city.

The water backs up in the system and wells up out of the drains, flooding the roads. It’s a chronic problem, he said, that the city is trying to solve.

“The city has to clear this every day,” Roberston said.

Tybee’s not alone. All over the country, old stormwater systems struggle to keep up with increased rainfall due to climate change. Rising sea levels and groundwater — also from climate change — squeeze the systems from the other end. Infrastructure like roads, hospitals and wastewater plants need to be shored up against flooding. Residents need protection from heat, wildfire, floodwater, and other climate impacts.

All of that is expensive. The good news for local governments tackling these problems is that lots of state and federal money is out there to fund resilience projects. The recent federal infrastructure law and Inflation Reduction Act are adding hundreds of billions of dollars to the pot.

But there’s also bad news: The money is often hard to actually get, and that difficulty can amplify inequities for communities that need help the most.

“All these great numbers and these great programs means absolutely nothing if communities that need it most can’t have access to it,” said Daniel Blackman, a regional administrator for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The funding often comes through competitive grants, with applications that are complicated and highly technical. They take time and expertise that under-resourced local governments often lack.

“One of the major capacity constraints of a lot of these local governments are that they have few grant writers on staff,” said Michael Dexter, director of federal programs for the Southeast Sustainability Directors Network.

Local government staff with plenty of work on their plates can often struggle to keep track of the different funding opportunities, coordinate the necessary partners, or come up with the local match funding some grants require.

“A lot of communities shy away from going after grant funds just because of that,” said Jennifer Kline, the coastal hazard specialist with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Coastal Management Program.

Without a dedicated, expert grant writer and plenty of staff, communities may miss out on these huge amounts of money. That’s especially true in communities of color where old, racist policies discouraged investment and growth, according to Nathaniel Smith, founder of the Partnership for Southern Equity and a 2018 Grist 50 honoree.

“If you look at many of the communities that face the greatest challenges, a lot of times people just assume that it happened by happenstance,” Smith said. “And that couldn’t be furthest from the truth.”

He pointed to redlining, a set of policies under which banks refused loans in areas deemed to be high-risk, which were primarily Black neighborhoods, as well as the construction of highways that obliterated thriving Black communities. There were also federal policies that encouraged suburbanization and white flight from cities. When schools are funded with property taxes so that wealthier and whiter areas have better equipped schools, that also amplifies the inequities, he said.

“All of these things have helped to facilitate a competitive advantage of, in particular, white communities and well-resourced communities,” Smith said.

For many of the same reasons, those same historically disinvested places — often communities of color — stand to be hit hardest by climate change: They often have less shade to reduce heat, are less protected from flooding, and the people who live there face more of the health problems that climate change makes worse.

The Biden administration is trying to address this disparity with its Justice40 initiative, which promises to put 40 percent of federal climate funding toward historically disadvantaged communities. The process for identifying those communities has been criticized for some of the metrics it uses, for failing to account for cumulative burdens, and for not explicitly incorporating race. Because it’s broken down by census tract, Dexter said, the program can miss “localized need.” In places where a poor neighborhood is near a wealthier one, for instance, the average income across the tract could be too high to qualify.

“There’s still obviously uncertainty about how that’s gonna be implemented in some of these various different grant competitions,” he said.

And communities that qualify still have to successfully apply for and win those grants.

Through a program called the Justice40 Accelerator, Smith’s group and several partners offer funding and technical support to help eligible places get that money. The program has so far trained two cohorts, a total of 100 environmental and community groups from across the country. Along with grant writing help and mentorship, the accelerator provides $25,000 to each participating organization to help them develop their proposals.

“It takes real resources and time and support to ensure that local communities are positioned to compete,” Smith said.

So far, the program boasts an 81 percent success rate for its cohorts’ grant applications, totaling more than $28 million in funding awarded.

Many of the state and federal agencies that dole out grants offer help as well. The EPA, for instance, recently announced $177 million in funding for 17 of what it’s calling Environmental Justice Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers. Their goal is to help “underserved and overburdened” communities access federal funds. The centers, mostly based at universities or environmental groups, will provide training on grant writing and management as well as practical assistance like translation services for community outreach and meetings.

“It’s not going to solve every problem,” said Blackman. “But what it’s going to do is it’s going to address the concern you have in those individuals being able to write and access federal funding and grants.”

Kline’s DNR Coastal Management Program also provides assistance in finding and applying for grants. Dexter said his group, the Southeast Sustainability Directors Network, does too.

What’s not clear is whether all of that is enough.

“I was going to say that’s the $100 million question,” Dexter joked. “No, that’s the $1 trillion, multiple-trillion-dollar question.”

And it’s just one of the looming questions in these early stages of the IRA and infrastructure law rollouts. No one knows yet if there’s enough help for places that need it, or if those communities know the help is out there. It’s also unclear whether the assistance programs will help local governments not just apply for and win grants, but administer them and deliver the projects on time — itself a time-consuming and difficult process.

There’s some reason for hope, Dexter said, even as communities scramble for funding and groups like his scramble to provide enough support: The new federal laws are designed to offer funding over several years, instead of immediately. This is an important lesson learned, he said, from 2009’s American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and its heavy emphasis on “shovel-ready” projects. This time, some of the funding can be used for planning, and there is a bit more time for cities to get their ducks in a row.

“Hypothetically, that leads to this great scenario where a community might come in, in year one, access planning funding, and then by year three or four be able to access the implementation funding for that project,” Dexter said.

That’s exactly the system Tybee Island is working with now. Robertson maintains a spreadsheet of projects that need funding. He has plans for how some of the work can unfold over multiple grant cycles.

“We’re in a pretty good space now,” he said. “We can be much more responsive to many more opportunities because we have identified these projects.”

While stormwater remains a problem, the city has gotten grants to build protective dunes and elevate flood-prone houses.

But Tybee Island got lucky: Robertson, a resident with grant-writing experience, stepped up after Hurricane Matthew devastated the island in 2016. The city contracted with him, and he deliberately worked to build up this grant capacity.

As the wave of new federal funding comes, other communities are looking for similar help.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.