Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

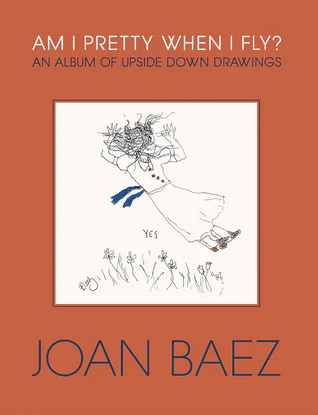

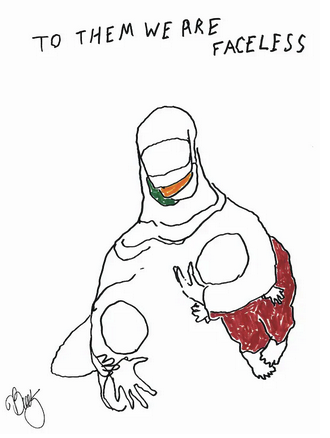

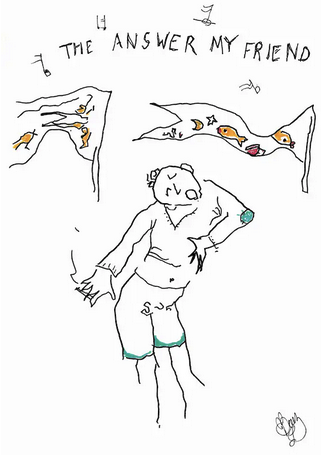

In a new book, ‘Am I Pretty When I Fly?,’ the singer-songwriter explains her attraction to visual art — and shares some of her recent works

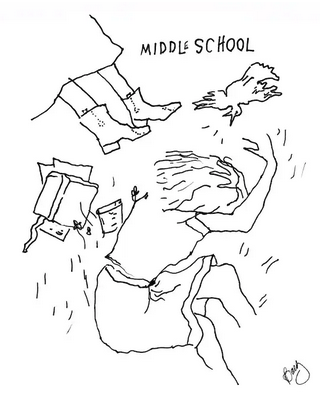

I drew my way through the torture known as middle school, and then on through high school. First it was five dollars apiece for portraits of Jimmy Dean (my last entrepreneurial venture), then portraits of Albert Einstein and Jawaharlal Nehru for my mom. I even drew every class project my teachers would allow me to: the study of human hair, how I imagined God to look.

Decades later, as an adult, I dabbled more with color. I worked with chalk, crayons, charcoal, pastels, watercolors, markers and colored ink, and I used brushes, fingers, hands, all in my own deliciously undisciplined fashion.

When I was in my 70s, I had a burgeoning — soon to be overwhelming — desire to use “real” paints. I assumed that would mean oils. But a local artist introduced me to acrylics, with which, at the time of this writing, I’ve now had a ten-year affair. I began with collages and worked in my kitchen on heavy, all-purpose art paper until the table was no more than a makeshift studio with no place left to put so much as a coffee mug. I moved myself and my paints into what until then had been an uninsulated pool house.

One day, I decided to paint a portrait. Assuming a portrait would take months to master, I trepidatiously put brush to canvas and found to my delight that the results weren’t half bad. I went on to paint portraits of people who had made social change through nonviolence — Gandhi as a college student, the Dalai Lama as a boy, Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, Greta Thunberg, and many more. I’ve since had two successful exhibits.

Decades ago, I don’t remember exactly when, I started making drawings upside down. I arrived at the upside-down drawings by chance.

Somewhere in my teenage years, probably out of boredom, I taught myself how to write backward, starting with EINAOJ ZEAB, my new name. I worked my way through the Greek alphabet: AHPLA ATEB, AMMAG, ATLED, and so on.

I still write backward as a form of therapy when I need to get to the root of a blockage or calm the buzzing heat of a panic attack. It’s as though the appropriate wires cross in my brain when I write backward, which allows information otherwise unavailable to surface.

Later, I began drawing with my left hand instead of my right. Like writing backward, using my nondominant hand opened a different compartment in my brain. I discovered that the results were less restrained and more fluid, and therefore more interesting to me. They didn’t look like the objects I was drawing, but it didn’t matter.

The same went for contour drawing, where you’re supposed to keep your eyes on the subject you’re drawing, not what your pencil is doing, checking the results only occasionally — the process has something of a tightrope-walk thrill about it and is fun, so you accept the lopsidedness of the final product.

After years of writing backward and drawing with my left hand, drawing upside down seemed a natural progression. Here is the process that developed:

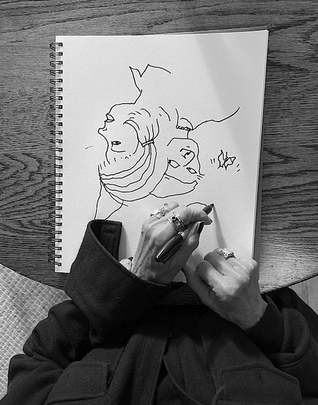

I start moving my pen or pencil around upside down on the paper — napkin, tablecloth, scrap — as though the drawing is being made for someone sitting opposite me at the table. Sometimes I have an idea of what I want to draw, but often I just let the pen or pencil start swooping around the page. Once I start to see what’s developing, I begin embellishing, often adding randomly the human form, a floating fish, a flower.

Eventually, I turn the drawing right-side-up and see if it needs anything to make it feel complete, in which case I reverse it again and add bits and pieces. Back right-side-up again and the real magic happens: I listen for what the drawing says to me. When a phrase (usually a pun) comes to my mind and resonates, I turn the paper one more time and write the phrase upside down.

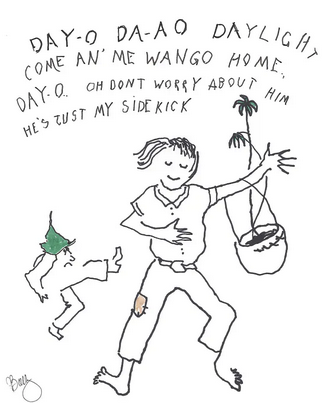

For instance, one of my drawings shows an upside-down girl with flowers in a basket. When righted, the images turn out to look more like palm trees. “Day-o, day-ay-ay-o, Daylight come and me wan’ go home” emerges from some other pocket of my brain: By the time I was 15, I had memorized all of Harry Belafonte’s repertoire, and “Day-O” was his best-known hit.

The little elf that was supposed to be dancing turns out to be kicking the girl, and the words “Oh don’t mind him, he’s just my side kick” spring up, and there and then the entire progression happens before I even realize what I’m doing.

I know perfectly well there is a neurological explanation for this whole upside-down method. I’m just not interested. Someone could likely explain why I’m keen on drawing this way, what’s happening during the process, and why the finished piece ends up the way it does. Also not interested.

We don’t need an explanation for every damn thing. There’s a lot to be said for letting go and doing something simply because it feels right.

From “Am I Pretty When I Fly?” by Joan Baez. Copyright 2023 by the author and reprinted with permission of Godine.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.