Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

I don’t know exactly what Putin will do. But neither do you!

I had a wise and brilliant thesis advisor, Professor Alexander Dallin. In the first draft of my thesis, I repeatedly wrote “Khrushchev believed,” Brezhnev thought,” or the “Soviet Union wanted.” In the margins of that draft, Dallin dozens of times wrote, “how do you know?” Today, when reading the many analyses of Putin’s decision-making, or sharing my views on Putin’s thinking for that matter, I often hear Dallin’s voice in my head. “How do you know, Mike?”

I do know something about Putin and how decision-making works in Russia. I first met Vladimir Putin in the spring of 1991. I wrote my first article about him in The Washington Post, published on March 3, 2000, a few weeks before he got elected as president for the first time. I titled it “Indifferent to Democracy,” in which I warned about Putin’s autocratic proclivities. The most recent piece I devoted to Putin was published in The Washington Post on January 26, 2022, and titled “Vladimir Putin does not think like we do.”

Since 1991, I have followed his career very closely. In fact, I just did a quick word search on my resume, and it looks like the word “Putin” appears in titles of over 60 articles and books I have written, including From Cold War to Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin’s Russia and Russia’s Unfinished Revolution: Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. While serving in the U.S. government for five years from 2009-2014, first as the Senior Director for Russia and Eurasia at the National Security Council and then as the U.S. Ambassador to the Russian Federation, I attended almost every meeting and listened in on almost every phone call that Putin had with President Obama, Vice President Biden, Secretary Kerry, and National Security Advisor Donilon. During those five years in the U.S. government, I also frequently met with some of Putin’s closest advisors and read the highest level of classified U.S. intelligence about Putin. To this day, I continue to interact with U.S. government officials of the highest level about Putin.

And yet, I do not pretend to know with certainty how Putin thinks. I am especially nervous about declaring with confidence that I can predict how Putin would react if he began to lose his war in Ukraine. So, everyone else should also stop pretending that they know with certainty as well. All of us “Putinologists” must be humble in our assessments especially about Putin’s future behavior, which means worrying about worst-case scenarios, but also not assuming that these worst-case scenarios are the only possible outcomes – the only possible choices that Putin can make.

Let’s start by unpacking the most common assumption from the ever-growing expert community about Putin – that before ending his invasion, he needs to “save face.” Some Putinologists, veering into the discipline of psychology, claim that the Kremlin autocrat needs an off-ramp – often a euphemism for some chunk of Ukrainian territory – to end his invasion. Otherwise, as this line of analysis contends, he will do something crazy.

But why must Putin need to save his face in the first place? In front of whom? His generals? Far-right nationalists? Prigozhin? Kadyrov? Xi? The presumption in this argument is usually that there is some faction inside Russia that Putin needs to placate with a “win.” But this assumption is wrong for several reasons.

First, Russia is a dictatorship. A strong one. Putin faces no challengers from elites or society that a democratic leader might face when fighting or losing a war. People criticizing Putin for failing to achieve his initial objectives, which he clearly stated in his February 21, 2022, address, have no way to overthrow him or to even really criticize him. Putin jailed thousands of anti-war critics of the war with little trouble. If he wanted to do so, Putin could silence pro-war critics just as easily.

Second, again in part because Russia is a dictatorship, Putin can define victory in any way he wants. Tomorrow on television, Putin could declare victory by claiming that he (1) freed the people of Donbas from fascists, (2) protected “ethnic Russians” in Crimea, or (3) stopped NATO’s invading forces in Ukraine before they reached Russian borders. Sound kooky? If you think it does, you obviously haven’t been watching the craziness expressed every night on Russian state-controlled television as I have. Victory is often an elastic term in military conflicts, but this is especially the case in Putin’s Russia.

Third, if Putin ended his war tomorrow and claimed victory (as defined by him), the vast majority of Russians would support him. Survey data make this clear. Data from October 2022, however flawed, indicates that “60% [of responders] would support Putin if he launche[d] a new attack on Kyiv” and “75% would support Putin if he stop[ped] the war right now.” See more here. Putin doesn’t need to save face in front of the Russian people. They support him in war and will support him if he decides to end his war.

Another central argument made by the new army of Putin specialists is that the Russian leader will use his nuclear wagon against Ukraine if he begins to lose, and especially if Kyiv begins to use military force to restore sovereignty over Crimea. (The idea that Putin is going to launch a nuclear attack against the NATO countries is so far-fetched that it doesn’t deserve any attention.) This is a real concern. I think it’s very unlikely, but Putin might. I am certainly worried about this scenario even if it is a low-probability event. In fact, I am much more worried about this scenario than my colleagues in the Ukrainian government and parliament, who remind me that it is their families who get attacked, not my family, and hence we should listen to them more closely and stop deterring ourselves from providing better weapons out of fear of nuclear escalation. I agree. But I am also still worried. There is academic literature that discusses how leaders sometimes do crazy things – "gamble for resurrection" – in desperate situations. (See Hein Goemans, War and Punishment, 2000, and Downs and Rocke, “Conflict, Agency, and Gambling for Resurrection: The Principal-Agent Problem Goes to War,” AJPS, 1994.) Putin is an ideologically motivated risk-taker. I wrote about these proclivities in “Putin, Putinism, and the Domestic Determinants of Russian Foreign Policy,” International Security, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Fall 2020), pp. 95-139. You can read the article here.

But Putin is not crazy. He too can assess the very high risks of using a nuclear weapon because that action would (1) not end the war; Ukrainians would instead double down in their efforts to defeat Russia; (2) further isolate Putin and Russia from the rest of the world, including from China and India; (3) not be supported by large segments of Russian society and maybe not even his own generals; and (4) trigger massive new military assistance to Ukraine– ATACMs, jets, armed drones – from the West that Biden and other leaders so far have not provided out of fear of nuclear escalation. I don’t know how he tallies up the risks versus the rewards, but there is no doubt in my mind that Putin is assessing these costs against the benefits of using a nuclear weapon.

Moreover, Putin has other options to achieve his goals or defend his alleged “red lines” such as keeping Crimea. Most obviously, he could sue for peace. Yes, some leaders fight until death when losing wars. But history shows that other leaders also try to negotiate, as American leaders did, for instance, in response to losing in Vietnam and Afghanistan. Russian leaders have done so repeatedly throughout history too, including in Afghanistan as well as at the end of World War I, the Japan-Russia war, and even the first Chechen war (Yeltsin, suffering heavy losses, agreed to a ceasefire in exchange for territorial autonomy, but not independence.) Putin can do so too. The assumption that his only option is to double down by using a nuclear weapon is simply not accurate. He has options. Again, he could declare victory overnight, call for a ceasefire before he loses Donbas or Crimea, and then call upon European leaders to pressure Zelenskyy to stop fighting, especially before Ukrainian armed forces try to retake Crimea. Some, not all, European leaders would likely side with Putin in the name of peace, which would put Zelenskyy in a very difficult position. To come out of this war with a “saved face,” Putin has more options than just the nuclear one.

Finally, let’s interrogate the “rat in the corner” metaphor that so many newly minted Putinologists love to invoke to explain how Putin will react if he loses his face, or is embarrassed by defeat. Putin is highly motivated by grand majestic ideas and emotions and has a strong desire to be right next to Peter the Great or Catherine the Great in the history books. As such, Putin might lash out irrationally when faced with genuine defeat on the battlefield. (It’s hard to imagine Putin being mentioned in the same breath as Peter the Great if he does something so crazy as to use a nuclear weapon against his Slavic “brothers and sisters” in Ukraine.) I don’t know. But you don’t know either. Too many new Putin experts have bought into the Russian leader’s very cultivated image as a strongman, riding horses shirtless, flying MiGs, hunting in Siberia, swimming in an ice-cold lake, and all that. But his actual behavior in the past has been more complicated and not so macho and decisive. Indeed, a few times when he has been cornered and lost face, he backed down.

For instance, last October, Putin blocked 218 ships in the Black Sea, seeking to transport 40,000 tons of Ukrainian wheat to Ethiopia, despite the July deal to allow grain exports from Ukraine. Putin said that following drone attacks on the Black Sea fleet, he “could not guarantee safety of civilian ships.” United Nations, the West, and Turkey called him out on this bluff. Eventually, Putin gave in, backed down, and no escalation happened.

Even more dramatically, in 2015, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan warned Putin of potential consequences should he continue to violate Turkish airspace by flying Russian jets into Syria. Putin ignored Erdoğan’s warning. So, on November 24, 2015, Turkey shot down a Russian SU-34 jet after ignoring several warnings made in English and Russian. The world braced for a big showdown between Turkey and Russia. But nothing happened. Russia did not attack Turkey. Putin backed down.

Finally, though a long time ago, Putin did not march into Tbilisi after he invaded Georgia in August 2008. He stopped short of the Georgian capital and did not try to overthrow President Saakashvili, even though Moscow told Washington that Saakashvili’s overthrow was a condition for stopping the invasion (Read chapter 53 of Condi Rice’s book, No Higher Honor.) He backed down. In 2014, Putin also halted his military operation to capture “Novorossiya” in eastern Ukraine, because Ukrainian armed forces stopped him.

I don’t know what Putin will do if he starts to lose in Donbas or Crimea. And so don’t you. But we all should recognize that he is not suicidal, he is not crazy, and that he has options.

READ MORE  A Ukrainian soldier guards his position. (photo: Mstyslav Chernov/AP)

A Ukrainian soldier guards his position. (photo: Mstyslav Chernov/AP)

Russia has pummeled the city for more than seven months, reducing it to a charred and mutilated ghost town. Moscow has sent wave after wave of soldiers and Wagner Group mercenaries toward Ukrainian positions, sustaining heavy casualties. At several points, as Russian forces close in, the city has appeared on the verge of falling. But for months, Ukrainian fighters have stood their ground.

Before the war, Bakhmut was mostly known as a center of the salt industry. But the relentless, intensifying fight for control of the city — which analysts say holds little strategic importance — has made it a rallying cry and political battleground for both sides.

The situation there is the “most difficult” in the country, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said in an address this week. Ukrainian officials have signaled in recent days the country’s forces may pull out of Bakhmut soon. On Friday, the head of a the Wagner Group said his forces had “practically surrounded” the city.

Here’s what to know about the battle for the city.

Where is Bakhmut, and what was it like before the war?

Bakhmut is a city in the eastern Ukraine region of Donetsk, more than 400 miles southeast of Kyiv and 10 miles from the border of Luhansk. The industrial city, with a prewar population of some 71,000, was known for its salt and gypsum mines. It’s also the site of a winery established on the order of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin in 1950, which for decades produced the Soviet Union’s top-flight sparkling wine, before rebranding when Ukraine gained independence in 1991.

Bakhmut has been caught up in conflict since 2014, when Russia-backed separatists launched a push to capture Donetsk. The separatists briefly seized parts of the city that year, before Ukrainian forces drove them out.

In 2016, residents changed the Soviet-era name, Artemivsk, back to the city’s historical name of Bakhmut, which dates to 1571, when it was a Cossack settlement.

The city is located southeast of Kramatorsk, a major regional hub and administrative center in Donbas, which includes the regions of Donetsk and Luhansk.

After Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year, Bakhmut came under Russian shelling in May, as part of Russia’s effort to encircle Ukrainian forces in Donetsk and Luhansk. Moscow has said it aims to capture the entirety of the two regions, which are among those it claimed in September to have annexed.

Since then, the war has transformed Bakhmut into a burned-out husk of its former self. Only several thousand residents remain, many of whom are elderly. Drone footage taken recently by the Associated Press shows blackened storefronts and apartment buildings reduced to rubble, along empty, snow-covered streets.

In December, Zelensky said Russian forces had turned the city into “burned ruins.”

Why is Bakhmut important?

Bakhmut was “not a particularly symbolically or strategically important city” originally, said Karolina Hird, Russia analyst at the Institute for the Study of War. It’s more than 30 miles from the closest major cities, Kramatorsk and Slovyansk.

But it caught the eye of Yevgeniy Prigozhin, head of the Wagner Group, known for its brutal tactics and interventions in conflicts in Africa and Syria.

Prigozhin poured tens of thousands of mercenaries, many recruited from Russian prisons, into Bakhmut — showing remarkable willingness to sacrifice these fighters for incremental territorial gains. Wagner commanders have sent wave after wave of often poorly trained ex-convicts toward Ukrainian positions, sustaining heavy casualties in the process.

For Prigozhin, the battle represents a chance to showcase Wagner’s abilities — even at enormous human cost — as he jockeys with Russia’s military chiefs for influence.

Paradoxically, analysts say, the city has also taken on outsize political importance for both sides in part because the fighting has been so intense there.

Since Ukrainian forces mounted successful counteroffensives in the fall and took back territory Russia had captured earlier in the war, the fighting has largely stagnated along the 600-mile front line. Bakhmut is one of the only places where Russian forces have made gains — so for Moscow, capturing the city would provide an important morale boost.

For Ukrainians, Bakhmut has become an emblem of resistance. The slogan “Bakhmut holds” is a rallying cry. When Zelensky visited Bakhmut in December, he called the besieged city “the fortress of our morale.”

The following day, during a surprise trip to Washington, Zelensky presented a flag from Bakhmut to Congress, and compared the battle to a famous turning point in the American Revolutionary War.

“Just like the Battle for Saratoga, the fight for Bakhmut will change the trajectory of our war for independence and for freedom,” he told U.S. lawmakers.

How has the battle developed?

Since September, Bakhmut has often seemed to be on the brink of falling, and Ukrainian officials have emphasized that the heaviest fighting is being waged there. But Ukrainian troops clung on through a cold winter, lobbing artillery at Russian forces.

Over the past week, fighting has intensified, with Russian forces stepping up attacks and seeking to encircle Bakhmut and the remaining Ukrainian troops there.

On Friday, Prigozhin said his fighters have “practically surrounded” the city. The Institute for the Study of War, citing geolocated footage, said Thursday that pro-Kremlin forces have made gains in areas near Bakhmut.

But Ukrainian soldier Yuriy Syrotyuk, who is stationed in the north of the city, told The Washington Post Friday the battle continues to rage, and Ukrainian forces were still in control of some areas and had not been ordered to retreat. Other Ukrainian solders said further reinforcements were being deployed, while some specialized units were told to move to nearby fallback positions.

Inside Bakhmut, the battle has become a “grinding, urban conflict of basically Wagner groups trying to force themselves into the center of the city, block by block,” Hird said.

As Russian forces made gains in recent weeks, some Ukrainian officials have indicated that troops could withdraw.

Zelensky said last month that Ukraine would keep a hold on Bakhmut, but “not at any cost.”

“Our military is obviously going to weigh all of the options. So far, they’ve held the city, but, if need be, they will strategically pull back because we’re not going to sacrifice all of our people just for nothing,” Alexander Rodnyansky, an economic adviser to Zelensky, told CNN this week.

What could a Russian victory in Bakhmut mean?

If Russian forces drive Ukrainian troops out of Bakhmut, it would represent a rare military victory for Russia in recent months, and a symbolic win for the Kremlin.

Within Russia, that outcome could provide a boost to the status of the Wagner Group and Prigozhin. Already, Wagner fighters’ plodding progress in Bakhmut has allowed Prigozhin to “very successfully increase his own standing” with Russian military commanders, Hird said, since he could say he is “the only one leading any troops to victory right now.”

In terms of its strategic value, however, analysts say such a victory would be Pyrrhic. The city itself is essentially destroyed. It could give the Russians a launch point from which to drive northwest along the E40 highway to Slovyansk, or north to the town of Siversk.

But Russian forces have tried and failed to take these cities in the past. And the Ukrainians have dug fallback defenses in nearby communities, likely to make any Russian advance difficult.

“The two paths of advance that taking Bakhmut might open up for them aren’t really good options,” Hird said, calling them “highly attritional.”

Even if Ukraine withdraws from Bakhmut, it has already succeeded in wearing down Russian forces and their Wagner colleagues. The White House recently estimated about 30,000 Wagner fighters have been injured or killed in the months-long battle.

The staggering losses and resources spent could make it harder for Moscow to mount an effective defense in the south, where Ukraine is probably preparing to launch a spring counteroffensive, Hird said.

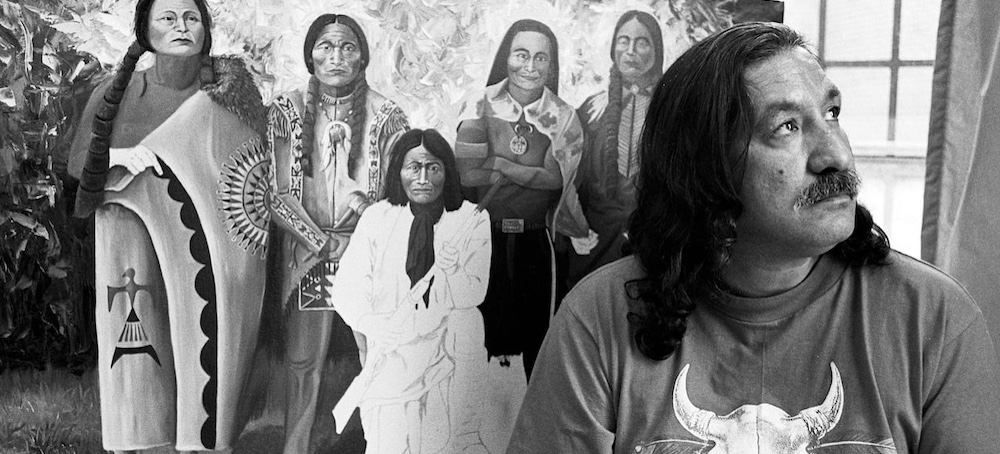

READ MORE  Leonard Peltier has been in prison for over four decades. (photo: Jeffry Scott)

Leonard Peltier has been in prison for over four decades. (photo: Jeffry Scott)

American Indian activist Leonard Peltier was wrongly convicted in the 1970s and is now the longest-held indigenous political prisoner in the United States. He should be granted clemency and released from prison immediately.

Recent investigations by the US Department of the Interior into the federal Indian boarding school system have confirmed Peltier’s version of history and what Native people have been saying for generations: that the boarding system was a horrific, sprawling network, encompassing more than four hundred schools across thirty-seven states or then-territories and targeting countless Native children. For more than 150 years, government officials stole Native children from their families, and many never returned home. Federal agents punished, and sometimes imprisoned, recalcitrant parents for keeping their children away from schools where their languages, their sense of self, and sometimes their very lives were taken from them. The child removal policy aimed to destroy Native families and weaken resistance to land seizures.

Peltier was nine years old when a government agent snatched him and his sisters away from their grandmother and placed them at the Wahpeton Boarding School in North Dakota. He remembers his grandmother crying, barely understanding the words of the person taking her grandchildren. He recalls parents singing “that way they do when someone has passed” as their children were loaded onto buses. “Maybe that day was my introduction to this destiny I did not choose,” Peltier wrote last year about his harrowing first day of boarding school. That episode, which he called “one of horror,” has haunted Peltier for life.

Last month marked Peltier’s forty-eighth year behind bars, locked away in a federal penitentiary in Florida, far from his family and homelands, and serving two consecutive life sentences for killing two FBI agents on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in June 1975, a crime he says he did not commit. His supporters consider his life of incarceration a collective punishment for indigenous people’s long history of defiance against US government policies. He is the longest-held indigenous political prisoner in the United States.

A nearly five-decade-long campaign to free Peltier has drawn the support of millions, including many Native nations, politicians, activists, celebrities, and world leaders. In the 1980s, more than seventeen million Soviet citizens sent petitions to Washington calling for Peltier’s release. Their government granted him political asylum and sent him a physician to examine his ailing eyes. The Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, where Peltier is enrolled, has urged President Joe Biden to free its elderly citizen and has prepared for his return home. Even a former federal prosecutor who helped keep Peltier in prison has petitioned for his clemency. Last year, United Nations experts recommended Peltier’s immediate release after finding that his imprisonment was so excessive it amounted to arbitrary detention.

Despite all appeals, the FBI remains the most outspoken opponent of freeing Peltier. “Retribution seems to have emerged as the primary if not sole reason” for Peltier’s continued imprisonment, Coleen Rowley, a retired FBI agent who was close to his case, wrote in a letter to Biden last December urging Peltier’s release. She called the FBI’s near half-century campaign an “emotion-driven ‘FBI family’ vendetta” against Peltier and the American Indian Movement.

Leonard Peltier, AIM, and the Fight for Native Rights

Born in 1944, Peltier joined the American Indian Movement (AIM) during the group’s heyday in the 1960s and 1970s. AIM had been formed in 1968 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, partly to end Native family separation and police violence. Two studies from 1969 to 1974 found that 25 to 35 percent of all Native children had been separated from their families and placed into institutions, foster care, or adoptive families. Many of AIM’s founders, like Peltier, had survived boarding schools only to face racism and inner-city poverty, incarceration, or the threat of having their families broken apart. AIM’s purpose was to build an alternative to this grim reality and to fight for Native rights.

Post–World War II Indian policy in the United States sought to formally end relations between the government and American Indian nations. “Termination policy” abolished more than one hundred tribes and removed millions of acres of land from federal trust status, opening them up for privatization and resource extraction. “Relocation policy” aimed to finish what termination had started by inducing hundreds of thousands of Native people to leave their reservations to find employment in far-off urban centers like Chicago, Cleveland, Denver, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Urban poverty and discrimination replaced rural, reservation poverty. These assimilationist policies gave rise to the Red Power movement in the 1960s.

Urban Native activists began occupying abandoned federal property to dramatize their demands, famously taking over the Alcatraz prison island in San Francisco Bay in 1969. AIM followed suit, leading a nationwide takeover of Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) offices in 1970 in protest of discriminatory hiring practices that privileged white employees over American Indian employees. The actions helped transform AIM from a local Twin Cities, Minnesota organization into a national movement.

By 1972 AIM had chapters in every region of the United States, and the same year, Peltier formerly joined AIM. He followed the movement to Washington, DC, taking over BIA headquarters during the Trail of Broken Treaties, which sought to reestablish treaty-making and nation-to-nation relations with the United States.

That action drew the ire of tribal leaders in the Oglala Lakota Pine Ridge Reservation, located largely in South Dakota, who banned AIM leaders from the reservation. Dissident Oglalas called on AIM to take a stand at Wounded Knee, abolish the tribal council, and reinstate the validity of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty and the traditional Lakota government. They obliged — for seventy-one days, beginning on February 27, 1973, Oglalas and members of AIM occupied Wounded Knee, South Dakota on the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Following the highly publicized takeover, violence and terror gripped the Pine Ridge. Dick Wilson, the autocratic tribal president, led a vicious crackdown on reservation dissidents, who sought to overturn a corrupt tribal council system that catered to outside economic interests and the assimilationist policies of the BIA. AIM allied itself with the “traditionals,” those who defended Lakota spirituality, sovereignty, and treaty rights. Elders, like Celia and Harry Jumping Bull, called upon Peltier and AIM for protection from Wilson’s vigilante “goon squad” and the FBI, who were waging a low-intensity dirty war against AIM and its supporters in the aftermath of Wounded Knee.

Two months before the firefight that would change Peltier’s life — and following the 1974 acquittal of AIM leadership involved in the Wounded Knee takeover — the FBI issued an internal position paper entitled “FBI Paramilitary Operations in Indian Country,” a how-to plan for confronting AIM in a battlefield-type situation. The report referred to an area outside the village of Oglala as having bunkers that would require a paramilitary force to overtake. The month before the firefight, FBI personnel, mostly SWAT team members, swarmed the Pine Ridge Reservation. One FBI map of the Jumping Bull property identified “bunkers” that turned out to be crumbling root cellars. Tensions were high, and the FBI appeared ready for war.

On June 25, 1975, FBI agents Ronald Williams and Jack Coler wore plain clothes and drove unmarked vehicles into the Jumping Bull ranch — outside Oglala on the western side of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation — while supposedly serving a warrant for assault and theft of a pair of cowboy boots. The agents never identified themselves, and a firefight erupted, catching a family with small children in the cross fire.

The shooting roused Peltier and his AIM group, which included Native youths, some of whom returned fire. One hundred fifty FBI agents, BIA police, and local vigilantes surrounded the property shortly after the shooting started. Peltier, his group, and local residents barely escaped through a barrage of bullets.

When the shooting stopped, three lay dead. The FBI claims Williams and Coler were shot in the head at close range. Joe Stuntz, a twenty-three-year-old member of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, was also killed. An unknown police agent shot Stuntz in the head. No one was ever prosecuted for his murder.

Meanwhile, Peltier and his group split up. Some of the youngsters returned to pay their respects at Stuntz’s funeral. Peltier and the others went underground. But the FBI, leading one the largest manhunts in its history, eventually caught up with them, eager to mete out its version of justice.

The Trials

The circumstances surrounding the June 1975 firefight — which a US Commission on Civil Rights investigation described as part of an FBI “reign of terror” against AIM and its supporters — were enough to convince an all-white jury in Cedar Rapids, Iowa in 1976 to acquit Peltier’s codefendants of murder charges on grounds of self-defense.

Bob Robideau and Dino Butler’s defense offered evidence of the FBI’s history of misconduct, which had recently been revealed during high-profile Senate hearings spearheaded by Idaho senator Frank Church. Church himself testified at the trial that “certain groups” — like the Communist Party, the Black Panthers, and the antiwar movement — “were targeted for surveillance [by the FBI] at least in part because of political attitudes.” AIM, too, faced its share of FBI harassment: disruptive informants, bad-jacketing campaigns, and paranoia-inducing surveillance.

The evidence presented was so damning that Peltier would be free today if he had been tried alongside Butler and Robideau. But he was prosecuted separately, with the government selecting a less sympathetic judge and less favorable venue (Fargo, North Dakota).

Peltier had fled after the shoot-out to Canada, where he was arrested and extradited to the United States based on false affidavits given by Myrtle Poor Bear, who claimed to be Peltier’s girlfriend at the time and an eyewitness to the agents’ killings. She was neither, nor had she ever met Peltier before his trial. Poor Bear later recanted her story, claiming she was coerced and threatened by FBI agents to provide false testimony. Other witnesses said FBI agents also threatened them or coerced their testimony.

FBI bullying of witnesses, however, was not allowed to be presented as evidence to the jury, nor was the climate of fear the FBI had created on the reservation. The prosecution withheld important ballistics evidence, it was later revealed, that could have been exculpatory. And one juror openly admitted to the court that she was “prejudiced against Indians” yet was allowed to remain on the jury.

In April 1977, the jury found Peltier guilty, and the judge sentenced him to two consecutive life sentences. “I have done nothing to feel guilty about,” Peltier told the judge. “The only thing I am guilty of and which I was convicted for was of being Chippewa and Sioux blood and for believing our sacred religion.”

On appeal, the government was forced to drop its theory that Peltier personally shot the agents due to lack of evidence. It instead pivoted to an accusation of aiding and abetting their murder. When asked whom Peltier was aiding and abetting, US Attorney Lynn Crooks answered, “whoever did the final shooting.” He added: “Perhaps aiding and abetting himself.”

Putting aside the absurdity of aiding and abetting oneself, Peltier could not have aided and abetted his codefendants, because aiding and abetting self-defense is not a crime. And according to the government’s own account, his codefendants were the only people close to the agents’ bodies during the firefight.

The theory upon which Peltier’s conviction now rests “is that he was guilty of murder simply because he was present with a weapon at the Reservation that day,” former US Attorney James Reynolds write in a 2021 letter to President Biden asking for Peltier’s clemency. Reynolds worked on Peltier’s prosecution and appeals cases, but believes today that his prosecution and continued incarceration “was and is unjust.” The prosecution was “not able to prove that Mr. Peltier personally committed any offense on the Pine Ridge Reservation.”

In a phone interview, Peltier told me that the facts of his case prove his innocence — but that the truth alone has not set him free.

Freedom for Peltier

Three days before the Jumping Bull shoot-out, the Church Committee decided to investigate FBI surveillance of AIM. But the decision was hushed up the day after the firefight. The International Leonard Peltier Defense Committee and Oglala members have been calling for a congressional investigation into the murders, rapes, and beatings that went uninvestigated or unsolved during that reign of terror.

According to Coleen Rowley, the former FBI agent, the bureau “indoctrinated” new agents at Quantico in the prosecution’s version of Peltier’s case in the 1980s. While FBI agents have restricted First Amendment rights, they made an exception for Peltier, she said, encouraging agents to write op-eds against his release and even marching in front of the White House during the final days of the Clinton administration to oppose a possible presidential pardon. Rowley is a rare dissenting voice as a retired FBI agent once close to Peltier’s case.

But there are more unanswered questions about Peltier’s case and uncertainty about his freedom. In a recent message to supporters, he spoke about his fear of never getting out of prison, or of only having a limited amount of time with his family before he leaves this world for the next.

February marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Wounded Knee occupation, but the wounds of the past have not been healed. The 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act, which aimed to reverse the Native family separation that took away Peltier and countless others, is on the chopping block at the Supreme Court. And the Biden administration has been silent about Peltier’s clemency application — his only legal chance at freedom.

“I live in the nation’s fastest-growing reservation in the United States,” Peltier once said about his predicament in federal prison.

But in a recent statement to supporters, Peltier expressed hope and encouraged them to teach their children “to plant a food forest or any plant that will provide for them in the future.”

“Plant a tree for me,” Peltier said.

READ MORE  "As a recent chilling exposé in the New York Times underscores, exploitation of child workers is flourishing at the intersection of failures in labor and immigration law." (photo: Kirsten Luce/NYT)

"As a recent chilling exposé in the New York Times underscores, exploitation of child workers is flourishing at the intersection of failures in labor and immigration law." (photo: Kirsten Luce/NYT)

ALSO SEE: Feds Expand Probe Into Migrant Child Labor in Slaughterhouses

The US’s miserly welfare state is known for forcing people to work rather than shielding them from the most exploitative jobs. And in Iowa, GOP lawmakers are taking the Dickensian cruelty further: they’re considering loosening restrictions on child labor.

Our most generous social supports — including health insurance, pensions, and paid leave — are offered as “fringe benefits” attached to some jobs. A second tier (including Social Security) structure social insurance benefits around wage-based contributions. And what’s left of direct assistance for the poor increasingly mandates employment — invariably low-wage and highly exploitative.

The “work first” logic of US social policy is animated by the “principle of less eligibility,” a remnant of Elizabethan poor law holding that alternatives to wage labor can never pay more than the leanest and meanest of jobs. And, as scholars Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward argued in Regulating the Poor (1971), that principle would and could be calibrated to labor market conditions: generous supports to dampen social unrest when labor markets were slack, miserly benefits when workers were needed.

The US deference to markets (and employers) is exacerbated by federalism — the discretion afforded states in setting eligibility thresholds and benefits. State legislatures, skittish about business investment and easily swayed by right-wing national lobbies, have proven reliable laboratories of autocracy and austerity.

Nowhere is this more nakedly on display than Iowa, once a “purple” state and now a purveyor of brazen anti-labor policies like loosening restrictions on child labor, which GOP lawmakers are now considering.

Iowa’s War on Workers

Iowa has been governed by a conservative Republican trifecta since 2016. When the pandemic hit, Governor Kim Reynolds and the Republican legislature chafed at the push to shut down the economy and only reluctantly passed the unemployment benefits extended and expanded by federal law. The Reynolds administration facilitated and celebrated Donald Trump’s April 2020 executive order (a document drafted by Midwestern meatpacking interests) ensuring “that processors of beef, pork, and poultry (‘meat and poultry’) in the food supply chain continue operating and fulfilling orders to ensure a continued supply of protein for Americans.”

And then, as soon as it could, the state pulled the plug on COVID-era protections and supports. In late 2020, Iowa Workforce Development retroactively adjusted its eligibility criteria for unemployment insurance and began clawing back benefits. In summer 2021, Iowa joined the roster of conservative states that bailed out of the federal pandemic programs prematurely — needlessly impoverishing and endangering their workers to score a thin political victory. Later that fall, it tightened the work-search requirements for those still unemployed.

It was straight out of the Elizabethan playbook: reluctantly offer social supports (a meager commitment, since the expanded and extended UI benefits were all federal dollars) when recession was unavoidable, and slash the generosity or accessibility of those benefits as soon as you wanted everyone back in the mills and mines.

In January, the Iowa legislature took another step down this Dickensian road, proposing a sweeping relaxation of its child-labor standards. The Iowa bill “relating to youth employment,” approved by committee in early February, would permit children as young as fourteen to work in industrial freezers and meat coolers. With a waiver from Iowa Workforce Development, children as young as fifteen could work on assembly lines and load or unload products weighing up to fifty pounds. The bill also loosens hours restrictions on work during the school year. And, of course, it shields employers from liability if a child worker is injured or killed at work — effectively stripping the right to workers compensation.

While masquerading as an effort to expand work opportunities for Iowa teenagers, the child-labor proposal has the fingerprints of the state’s low-wage, high-risk employers all over it. Only eight lobbies have publicly registered in support of the bill. Three of those (Americans for Prosperity, the Opportunity Solutions Project, and the National Federation of Independent Business) are notoriously anti-worker national groups that routinely trawl statehouses supporting such bills. The other five (the Iowa-Nebraska Farm Equipment Dealers Association, the Home Builders Association of Iowa, the Iowa Association of Business and Industry, the Iowa Hotel and Lodging Association, and the Iowa Restaurant Association) represent Iowa employers whose routine violation of child-labor laws would be washed away by regulatory waivers.

It is hard to underestimate the looming danger and damage.

Federal child-labor laws, first proposed over a century ago, were consistently rebuffed by the state legislatures — especially from the Jim Crow South — which also refused to ratify a constitutional amendment that would have prohibited the practice. It was not until the passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) in 1938 that federal law took action against “oppressive child labor.”

But the FLSA was riddled with holes. Large swaths of the economy (including agriculture) were left out, and the child-labor provisions regulated only the transport of goods across state lines, not their actual production. So even as the scope and reach of the FLSA expanded, the regulation of child labor depended heavily on states’ willingness to enumerate their own (often locally specific) lists of prohibited occupations, industries, and practices.

The Iowa bill turns that logic on its head. Instead of identifying occupations or worksites in Iowa that put young workers at risk, it exempts or waives protection when and where employers complain about a labor shortage.

The perils of child labor are well documented. The earliest regulations were motivated by a desire to free children from exploitative, dangerous occupations and to improve school attendance. Current research backs up those concerns: lightly regulated youth employment “comes with high psychological and social costs,” and young workers suffer workplace injuries and fatalities at much higher rates than older workers.

And such problems are getting worse. As a recent chilling exposé in the New York Times underscores, exploitation of child workers is flourishing at the intersection of failures in labor and immigration law. Last year, the Department of Labor concluded investigations involving 3,876 minors employed in violation of child-labor laws, a more than threefold jump since 2015.

Iowa’s bill would dump its young people into workplaces notorious for flouting safety regulations and for their coziness with state regulators — a problem dramatized by the pandemic but scarcely confined to it. The state’s rate of worker fatalities (at 4.9 per 1000) is 40 percent higher than the national rate. Of the 150 complaints of dangerous working conditions lodged in the first six months of the pandemic, all but five were closed by Iowa Occupational Health and Safety Administration with no inspection of the workplace in question.

The proposed bill protects employers from liability for injuries to young workers, and even those with recourse to workers’ compensation can’t count on much. In 2017, Iowa overhauled its workers’ compensation law — dramatically reducing benefits by toying with the definition of “permanent disability” and shifting much of the burden of workplace injuries onto workers and their families.

Making Iowa a Better Place to Work

The unspoken admission behind the child-labor bill is this: Iowa has a persistent labor shortage because it is a lousy place to work. The share of private sector workers covered by a collective bargaining contract has fallen from 21.5 percent in the early 1980s to just 4.8 percent today. The minimum wage ($7.25) hasn’t been raised since 2008, and its real (inflation-adjusted) value is now just over $5 an hour. One in seven Iowa workers is a victim of wage theft, with losses averaging over $3,765 a year for those affected.

Little wonder the state is shedding workers. Outside the state’s scattered metropolitan counties, decent employment options are fleeting. Over two-thirds (68 of 99) of Iowa counties lost population between 2010 and 2020. Iowa has one of the worst rates of “brain drain” (the percentage gap between the number of college graduates produced in a state and the number living there) in the nation.

One approach, notably absent in the anterooms of the state capitol, would be to make the Hawkeye State a better place to work — we face a shortage of good jobs, not a shortage of workers. So raise wages. Make it easier for workers to organize. Enforce basic labor standards. Hold employers accountable. Seems like a better option than backfilling labor markets with children.

READ MORE  Starbucks employees and supporters react as votes are read during a viewing of their union election. (photo: Joshua Bessex/AP)

Starbucks employees and supporters react as votes are read during a viewing of their union election. (photo: Joshua Bessex/AP)

This week, white-collar workers at Starbucks signed an open letter in solidarity with baristas, Bernie Sanders announced he will force Howard Schultz to testify before a Senate committee, and the NLRB condemned the company for ignoring worker’s fundamental rights.

First, dozens of the company’s own white-collar workers went into open revolt, releasing a letter to the public making clear their support for the baristas and opposing new back-to-office rules.

Then, Bernie Sanders’s office announced that the committee he chairs in the US Senate will seek a subpoena to force Howard Schultz, the outgoing CEO of Starbucks, to testify under oath about the company’s labor practices.

Finally, a National Labor Review Board (NLRB) administrative judge issued a ruling against the company stating, in a two-hundred-plus page document, that Starbucks had engaged in “egregious and widespread misconduct demonstrating a general disregard for the employees’ fundamental rights” in Buffalo, New York.

And that was just Wednesday.

“Things are starting to boil to the top,” said Boston-based barista Sky Bauer-Rowe. “It just needs a little bit more temperature.”

At about 9:00 a.m., Bloomberg broke a story about an open letter by several dozen white-collar employees of the union lending support to their barista coworkers. The workers, many of whom hold tech roles, criticized the company for “tampering with the federal right of store partners to have fair elections, free from fear, coercion, and intimidation.”

The letter also drew attention to the signatories’ own workplace issues, slamming Starbucks for a “poorly planned ‘return to office’ mandate” that “[prioritized] corporate control.”

The workers said, “We love Starbucks, but these actions are fracturing trust in Starbucks leadership.”

The move didn’t come out of nowhere; according to the Starbucks Workers United (SBWU) union, the white-collar workers had been coordinating with baristas in Seattle, where the company is headquartered. The open letter was signed by forty-four workers by name and had an additional twenty-two anonymous sponsors.

Soon after the signatories released the letter, Bernie Sanders’s office announced that Schultz will face a vote on a subpoena. An executive body of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP), which Sanders chairs, will vote on March 8.

“Unfortunately, Mr. Schultz has given us no choice, but to subpoena him. A multi-billion-dollar corporation like Starbucks cannot continue to break federal labor law with impunity,” Sanders said in a release.

Bauer-Rowe reacted, “I’m very critical of politicians in general. . . . but then I see Bernie Sanders, putting a whole committee together to subpoena Howard Schultz. Wow, that’s more than any politician has ever done for us.”

While Sanders had previously hinted at a possible subpoena, his office had stayed mum until yesterday about whether that step would indeed be taken.

Sanders added, “For nearly a year, I and many of my colleagues in the Senate have repeatedly asked Mr. Schultz to respect the constitutional right of workers at Starbucks to form a union and to stop violating federal labor laws.”

He continued, “Mr. Schultz has failed to respond to those requests. He has denied meeting and document requests, skirted congressional oversight attempts, and refused to answer any of the serious questions we have asked.”

If Sanders’s committee moves forward with a subpoena, Schultz would be forced to testify and face questions about Starbucks’s union busting from the Vermont firebrand — along with other senators — under penalty of perjury.

But the day wasn’t over. At about 2:00 p.m., the NLRB administrative judge issued his ruling that Starbucks had violated federal labor law hundreds of times in Buffalo alone.

Stores in the Buffalo region were the first to organize in this latest wave of Starbucks unionizing, and there was little public attention to Starbucks’s illegal responses until SBWU achieved its first win in a store election in December 2021.

Workers, though, have long alleged that Starbucks had engaged in massive union busting in Buffalo, including store closures, firings, and other direct interference with the right to organize under the cover of night. With the support of parent union Workers United, SBWU workers registered hundreds of allegations of illegal union busting by Starbucks with the NLRB.

“It’s very validating to have this two-hundred-plus page document basically saying, ‘You’re right. He did all these things,’” said Casey Moore, an SBWU spokesperson.

If it is held up on potentially multiple appeals, the decision would reinstate and/or compensate dozens of workers for illegal union busting they endured, including seven who were fired. The judge ordered dozens of other remedies as well.

For example, the judge also ruled that a store that was illegally shut down will have to be reopened. Starbucks will also be forced to acknowledge to all of its baristas nationwide, through its electronic channels, a detailed and lengthy list of what it has been ordered to commit to by the NLRB.

The administrative judge is requiring that the notice be posted in all of the company’s stores for the duration of the organizing campaign. Schultz himself will personally have to read the notice to all Buffalo workers or do so on video.

While the judgment will not have immediate effect — it can be appealed within the NLRB and then in court — it continues to build SBWU’s case in the court of public opinion.

Moreover, the constant stream of legitimized allegations is regularly giving the “progressive” company black eyes in public. These threats to the company’s brand include unlawful firings, illegal hours cuts, selective benefits and raises to nonunion stores, and general interference with the freedom to organize.

And some on the business side are starting to take notice too; the company faces a shareholder vote on whether to hold an external examination of Starbucks’s labor practices at its upcoming annual meeting.

Taken together, Wednesday’s events were a breakthrough in holding Starbucks — and Howard Schultz himself — accountable for illegal union busting that baristas have long alleged, even as the chief executive prepares to go behind the scenes again.

With spring mornings waiting around the corner, baristas see daylight. “I feel like the walls are closing in on him and he can’t run anymore,” said Bauer-Rowe.

READ MORE  Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich attends a cabinet meeting at the Prime Minister's office in Jerusalem. (photo: Reuters)

Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich attends a cabinet meeting at the Prime Minister's office in Jerusalem. (photo: Reuters)

Growing number of groups demand Israeli minister be sanctioned and barred from coming to the US for 'incitement of genocide'

In separate statements, a number of groups ranging from organisations focused on human rights in the Middle East to rabbinical groups in the US have called for Washington to deny Smotrich a visa over his comments.

Democracy for the Arab World Now (Dawn) on Wednesday called for both Smotrich's visa to be revoked and for him to face sanctions. The rights group stated that his comments could amount to "incitement of genocide".

"The US should immediately sanction Bezalel Smotrich for directly and brazenly encouraging mass violence against civilians," Adam Shapiro, advocacy director for Israel-Palestine at Dawn, said in a statement.

"The United States must not give the impression that it condones his hateful and violent ideology and policies, and anything less would make the Biden Administration culpable in whatever violence comes next."

The Adalah Justice Project has started an online petition demanding Smotrich be banned from the US, and so far has received more than 3,000 signatures.

"A state representative calling for the burning of homes and killing of people should not be given a platform to spread his racism and incite more violence against Palestinians," Sumaya Awad, communications director at the Adalah Justice Project, told Middle East Eye.

Awad added that the US should also be pressured to ban groups "from raising money for illegal settlements built on Palestinian land and whose occupants most recently set ablaze the Palestinian village of Huwwara".

When asked during a press briefing on Thursday whether the US would issue such a ban, State Department spokesperson Ned Price said: "We don't speak to individual visa records - nor as a general matter - to a particular individual's eligibility for a US visa."

Price on Wednesday called Smotrich's remarks "repugnant" and "disgusting" and called for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to disavow the comments.

"It is time for Biden to end US complicity in Israel's violent apartheid. Under no circumstances should Bezalel Smotrich be permitted to visit the US," Beth Miller, political director of Jewish Voice for Peace Action, told MEE.

Rift between Israel and Jewish Americans

On Sunday, hundreds of Israeli settlers attacked Palestinian towns and villages near Nablus, following a shooting that killed two Israelis in the town of Huwwara earlier that day.

In the rampage on Huwwara and other Palestinian villages, at least one Palestinian was killed and nearly 400 were wounded. Israel's police have arrested 10 people for suspected involvement in the attack.

Before and after the mob violence took place, several Israeli politicians, including Smotrich, appeared to encourage or support the settlers' actions.

Smotrich is expected to visit the US later this month and will meet with the New York-based Israel Bonds organisation.

He does not have any meetings scheduled with the Biden administration, and two US officials told Axios that "even if he asked for meetings with Biden officials, he likely wouldn't get them".

In addition to rights groups and progressive Jewish organisations, some liberal Zionist groups also condemned Smotrich's remarks and called for him to be denied entry.

The pro-Israel group Americans for Peace Now is circulating its own petition urging Biden to deny Smotrich entry.

“Smotrich's comments are even more dangerous now that Israel’s de jure annexation of the West Bank has made him effectively the governor of the territory, with broad oversight over most areas of civil administration,” said Rabbi Jill Jacobs, CEO of T’ruah, a Jewish human rights group representing more than 2,300 rabbis and cantors in North America.

Jacobs called on the Biden administration to decline any meetings with Smotrich if he is allowed into the country and also urged US Jewish groups to refuse to engage with him.

The calls add to a growing rift between the broader Jewish American community and the Israeli government, headed by Netanyahu and a far-right coalition.

READ MORE  Minnesota may soon face a legal challenge from its next-door neighbor, North Dakota. (photo: Andrew Cullen/Reuters)

Minnesota may soon face a legal challenge from its next-door neighbor, North Dakota. (photo: Andrew Cullen/Reuters)

Interstate feuds threaten to make the difficult task of getting regional power grids off fossil fuels even more complicated.

Not long after Minnesota’s governor signed the law, the North Dakota Industrial Commission, the three-member body that oversees North Dakota’s utilities, agreed unanimously to consider a lawsuit challenging the new legislation. The law, North Dakota regulators said, infringes on North Dakota’s rights under the Dormant Commerce Clause in the United States Constitution by stipulating what types of energy it can contribute to Minnesota’s energy market.

“This isn’t about the environment. This is about state sovereignty,” North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum, the chair of the Industrial Commission, said. Minnesota Governor Tim Walz, a longtime proponent of clean energy legislation, was quick to respond. “I trust that this bill is solid,” he told reporters. “I trust that it will stand up because it was written to do exactly that.”

The potential showdown illuminates an underappreciated obstacle to the energy transition: interstate beef. Feuds between neighboring states threaten to make the difficult task of getting regional power grids off fossil fuels even more complicated and expensive.

North Dakota hasn’t filed a lawsuit yet, but the Industrial Commission has requested $3 million from the state legislature for legal fees on top of $1 million the commission has already allocated to the effort from its “Lignite Research Program” — an initiative funded by taxes on fossil fuel revenue that researches and develops new coal projects in the state.

It’s no mystery why North Dakota was so quick to go on the offensive. Most of the state’s power comes from coal, and it sells some 50 percent of the electricity it generates to nearby states. Its biggest customer is Minnesota. Minnesota’s new law stipulates that all electricity sold in the state come from renewable sources on a set timeline — 80 percent carbon-free by 2030, 90 percent by 2035, and 100 percent by 2040. That means that North Dakota’s coal-fired power will be squeezed out of Minnesota’s electricity market.

North Dakota regulators are confident they’ll prevail in a legal dispute, but Burgum said the state is waiting to see whether Minnesota will amend its law before taking the disagreement to court. “This is something where if they make a small change we can avoid the certainty of a lawsuit that’s probably going to have a certain outcome to it,” the governor said in early February. The state successfully sued Minnesota over a 2007 law that sought to ban coal imports to the state from new sources. But outside legal experts aren’t so sure the plaintiffs will be victorious this time.

“Minnesota is under no legal duty to prop up North Dakota power plants,” Michael Gerrard, founder of Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, told Grist. The state would find itself in legal trouble if it discriminated between in-state and out-of-state power plants, he said. For example, if Minnesota’s law accepted coal-fired power from plants inside its own borders but banned coal power from North Dakota, that would certainly violate federal interstate commerce law. But that’s not what Minnesota has proposed. The state is requiring clean power across the board, from in-state and outside sources.

Gerrard pointed to a comparable 2015 case in Colorado. A fossil fuel industry group sued the state over a renewable energy standard it passed in 2004 — the very first clean energy standard passed by popular vote in the U.S. The group argued the standard overstepped Colorado’s authority under the U.S. constitution, a similar argument to the one North Dakota is threatening to make. But a federal court upheld the standard. The decision was written by Neil Gorsuch, who is now one of the more conservative judges on the U.S. Supreme Court.

“We have one of the conservative Supreme Court justices saying that a state clean energy standard is fine,” Gerrard said. “So I think the outlook, if this case gets to the Supreme Court, would be favorable to Minnesota.”

That’s significant, especially from a climate perspective. With Republicans in control of the U.S. House of Representatives, the chances of new climate legislation passing in this Congress are slim. Looking ahead, Gerrard said, the progress that does take place on combating climate change will likely happen at the state level. “Certainly the moves by some of the blue states to do more on climate change are going to be some of the central elements of climate action for the next two years,” he said. He expects red states and the fossil fuel industry to continue to sue to try to stop clean energy mandates. “Industry will fight back,” he said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.