Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

There must be some freethinking Democrat who’s willing to get in the race.

He will most likely make this official in the next couple of months, and with the support of nearly every elected Democrat in range of a microphone. That is how things are typically done in Washington: The White House shall make you primary-proof. The gods of groupthink have decreed as much.

Unless some freethinking Democrat comes along and chooses to ignore the groupthink.

In private, of course, many elected Democrats say Biden is too old to run again and that they wish he’d step away—which aligns with what large majorities of Democrats and independents have been telling pollsters for months. The public silence around the president’s predicament has become tiresome and potentially catastrophic for the Democratic Party. Somebody should make a refreshing nuisance of themselves and involve the voters in this decision.

Ukraine's 72nd Brigade near Vuhledar, in the Donetsk region of Ukraine, on Saturday. (photo: Tyler Hicks/NYT)

Ukraine's 72nd Brigade near Vuhledar, in the Donetsk region of Ukraine, on Saturday. (photo: Tyler Hicks/NYT)

A three-week fight in the town of Vuhledar in southern Ukraine produced what Ukrainian officials say was the biggest tank battle of the war so far, and a stinging setback for the Russians.

The commander, Pvt. Dmytro Hrebenok, recites the Lord’s Prayer. Then, the men walk around the tank, patting its chunky green armor.

“We say, ‘Please, don’t let us down in battle,’” said Sgt. Artyom Knignitsky, the mechanic. “‘Bring us in and bring us out.’”

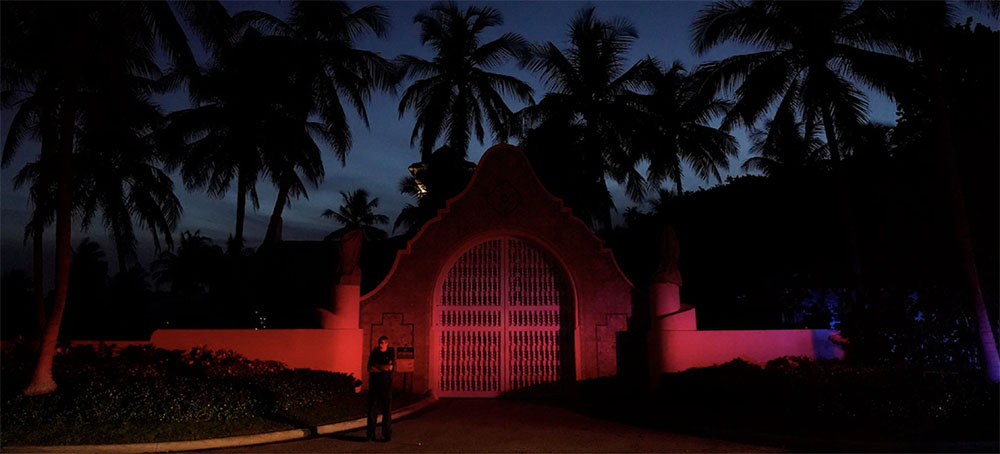

READ MORE  A man stands outside an entrance to former president Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago estate on Aug. 8, 2022, in Palm Beach, Fla. (photo: Wilfredo Lee/AP)

A man stands outside an entrance to former president Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago estate on Aug. 8, 2022, in Palm Beach, Fla. (photo: Wilfredo Lee/AP)

An exclusive look at behind-the-scenes deliberations as both sides wrestled with a national security case that has potentially far-reaching political consequences

Prosecutors argued that new evidence suggested Trump was knowingly concealing secret documents at his Palm Beach, Fla., home and urged the FBI to conduct a surprise raid at the property. But two senior FBI officials who would be in charge of leading the search resisted the plan as too combative and proposed instead to seek Trump’s permission to search his property, according to the four people, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe a sensitive investigation.

Prosecutors ultimately prevailed in that dispute, one of several previously unreported clashes in a tense tug of war between two arms of the Justice Department over how aggressively to pursue a criminal investigation of a former president. The FBI conducted an unprecedented raid on Aug. 8, recovering more than 100 classified items, among them a document describing a foreign government’s military defenses, including its nuclear capabilities.

Starting in May, FBI agents in the Washington field office had sought to slow the probe, urging caution given its extraordinary sensitivity, the people said.

Some of those field agents wanted to shutter the criminal investigation altogether in early June, after Trump’s legal team asserted a diligent search had been conducted and all classified records had been turned over, according to some people with knowledge of the discussions.

The idea of closing the probe was not something that was discussed or considered by FBI leadership and would not have been approved, a senior law enforcement official said.

This account reveals for the first time the degree of tension among law enforcement officials and behind-the-scenes deliberations as they wrestled with a national security case that has potentially far-reaching political consequences.

The disagreements stemmed in large part from worries among officials that whatever steps they took in investigating a former president would face intense scrutiny and second-guessing by people inside and outside the government. However, the agents, who typically perform the bulk of the investigative work in cases, and the prosecutors, who guide agents’ work and decide on criminal charges, ultimately focused on very different pitfalls, according to people familiar with their discussions.

On one side, federal prosecutors in the department’s national security division advocated aggressive ways to secure some of the country’s most closely guarded secrets, which they feared Trump was intentionally hiding at Mar-a-Lago; on the other, FBI agents in the Washington field office urged more caution with such a high-profile matter, recommending they take a cooperative rather than confrontational approach.

Both sides were mindful of the intense scrutiny the case was drawing and felt they had to be above reproach while investigating a former president then expected to run for reelection. While trying to follow the Justice Department playbook for classified records probes, investigators on both sides braced for Trump to follow his own playbook of publicly attacking the integrity of their investigation, according to people with knowledge of their discussions.

The FBI agents’ caution also was rooted in the fact that mistakes in prior probes of Hillary Clinton and Trump had proved damaging to the FBI, and the cases subjected the bureau to sustained public attacks from partisans, the people said.

Prosecutors countered that the FBI failing to treat Trump as it had other government employees who were not truthful about classified records could threaten the nation’s security. As evidence surfaced suggesting that Trump or his team was holding back sensitive records, the prosecutors pushed for quick action to recover them, according to the people familiar with the discussions.

While the people who described these sensitive discussions disagreed on some particulars, they agreed on many aspects of the dispute.

Spokespeople for the Justice Department and the FBI declined to comment for this story.

It is not unusual for FBI agents and Justice Department prosecutors to disagree during an investigation about how aggressively to pursue witnesses or other evidence. Often, those disagreements are temporary flare-ups that are debated, decided and resolved in due course.

While the FBI tends to have great discretion in the day-to-day conduct of investigations, it is up to prosecutors to decide whether to file criminal charges — and, like the prosecutors, the director of the FBI ultimately reports to the attorney general. The Mar-a-Lago case was unusual not just for its focus on a former president, but in the way it was closely monitored at every step by senior Justice Department officials. Attorney General Merrick Garland said he “personally approved” the search of Trump’s property.

It’s unclear how the investigation may have been reshaped if the two sides had settled their disputes differently. Had the criminal investigation been closed in June, as some FBI field agents discussed, legal experts said it’s unlikely agents would have yet recovered the items found in the FBI’s raid of Trump’s residence.

Some inside the probe argued the infighting delayed the search by months, ultimately reducing the time prosecutors had to reach a decision on possible charges. Others contend the discussions were necessary to ensure the investigation proceeded on the surest footing, enabling officials to gather more evidence before they executed the search, people familiar with the dynamics said.

In November, before prosecutors had finished their work and decided whether to charge Trump or anyone else, he announced his campaign to retake the White House in 2024, leading Garland to appoint a special counsel, Jack Smith, to complete the investigation.

A collision course

From the moment the FBI and Justice Department received a formal referral on Feb. 7 from the National Archives and Records Administration to investigate missing classified records that could be in Trump’s possession, FBI investigators and federal prosecutors knew they were taking on a highly charged and sensitive case.

Archives officials reported that, after they had pleaded with Trump’s representatives for months, the former president had in January returned 15 boxes of government records he had stored at Mar-a-Lago since his presidency ended. Sifting through the boxes’ contents, archivists were shocked by what they found: 184 classified documents consisting of 700 pages. Archives officials said they had reason to believe Trump still had more sensitive or classified documents he took from the White House.

Prosecutors in the Justice Department’s national security division needed to answer two immediate questions: Was national security damaged by classified records being kept at Trump’s Florida club, and were any more sensitive records still in Trump’s possession?

Prosecutors and FBI agents were set on a collision course in April, when Trump through his lawyers tried to block the FBI from reviewing the classified records the Archives found. That set off alarm bells for prosecutors because it signaled he might be seeking to hide something, according to people familiar with the case. In preliminary interviews with witnesses in April and May, including Trump associates and staff, investigators were told of many more boxes of presidential records at Mar-a-Lago that could contain classified materials — similar in packaging to the boxes shipped there from the White House, and to those returned to the Archives in January, the people said.

The prosecutors and FBI agents began clashing in previously unreported incidents in early May, the people said. Jay Bratt, the prosecutor leading the department’s counterespionage work, advocated seeking a judge’s warrant for an unannounced search at the property to quickly recover any sensitive documents still there.

The FBI often conducts raids of properties without advance notice when investigators have reason to believe evidence is being withheld or could be destroyed. Some prosecutors saw guideposts in a related case a decade earlier, when Army Gen. David H. Petraeus lied to FBI agents about whether he had given classified information to a book author with whom he was having an affair. Agents executed a search warrant at Petraeus’s house and retrieved a cache of notebooks in which the prominent general improperly had stored extensive amounts of classified information.

But FBI agents viewed a Mar-a-Lago search in May as premature and combative, especially given that it involved raiding the home of a former president. That spring, top officials at FBI headquarters met with prosecutors to review the strength of evidence that could be used to justify a surprise search, according to two people familiar with their work.

Encountering resistance, Bratt agreed for the time being to subpoena Trump. On June 3, Bratt and a small number of FBI agents visited Mar-a-Lago to meet with Trump’s lawyer and collect any classified records the Trump team had found to comply with the subpoena. That day, Trump’s lawyer, Evan Corcoran, handed over an expandable envelope containing 38 classified records and produced a letter signed by another lawyer, Christina Bobb, asserting that a diligent search had been conducted and all classified records had been turned over.

Some FBI field agents then argued to prosecutors that they were inclined to believe Trump and his team had delivered everything the government sought to protect and said the bureau should close down its criminal investigation, according to some people familiar with the discussions.

But they said national security prosecutors pushed back and instead urged FBI agents to gather more evidence by conducting follow-up interviews with witnesses and obtaining Mar-a-Lago surveillance video from the Trump Organization.

The government sought surveillance video footage by subpoena in late June. It showed someone moving boxes from the area where records had been stored, not long after Trump was put on notice to return all such records, according to people familiar with the probe. That evidence suggested it was likely more classified records remained at Mar-a-Lago, the people said, despite the claim of Trump’s lawyers. It also painted for both sides a far more worrisome picture — one that would soon build the legal justification for the August raid.

By mid-July, the prosecutors were eager for the FBI to scour the premises of Mar-a-Lago. They argued that the probable cause for a search warrant was more than solid, and the likelihood of finding classified records and evidence of obstruction was high, according to the four people.

But the prosecutors learned FBI agents were still loath to conduct a surprise search. They also heard from top FBI officials that some agents were simply afraid: They worried taking aggressive steps investigating Trump could blemish or even end their careers, according to some people with knowledge of the discussions. One official dubbed it “the hangover of Crossfire Hurricane,” a reference to the FBI investigation of Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election and possible connections to the Trump campaign, the people said. As president, Trump repeatedly targeted some FBI officials involved in the Russia case.

A rift within the FBI

Against that backdrop, Bratt and other senior national security prosecutors, including Assistant Attorney General Matt Olsen and George Toscas, a top counterintelligence official, met about a week before the Aug. 8 raid with FBI agents on their turf, inside an FBI conference room.

The prosecutors brought with them a draft search warrant and argued that the FBI had no other choice but to search Mar-a-Lago as soon as practically possible, according to people with knowledge of the meeting. Prosecutors said the search was the only safe way to recover an untold number of sensitive government records that witnesses had said were still on the property.

Steven M. D’Antuono, then the head of the FBI Washington field office, which was running the investigation, was adamant the FBI should not do a surprise search, according to the people.

D’Antuono said he would agree to lead such a raid only if he were ordered to, according to two of the people. The two other people said D’Antuono did not refuse to do the search but argued that it should be a consensual search agreed to by Trump’s legal team. He repeatedly urged that the FBI instead seek to persuade Corcoran to agree to a consensual search of the property, said all four of the people.

Tempers ran high in the meeting. Bratt raised his voice at times and stressed to the FBI agents that the time for trusting Trump and his lawyer was over, some of the people said. He reminded them of the new footage suggesting Trump or his aides could be concealing classified records at the Florida club.

D’Antuono and some fellow FBI officials complained how bad it would look for agents with “FBI” emblazoned on their jackets to invade a former president’s home, according to some people with knowledge of the meeting. The FBI’s top counterintelligence official, Alan E. Kohler Jr., then asked the senior FBI agents to consider how bad it would look if the FBI chose not to act and government secrets were hidden at Mar-a-Lago, the people said.

D’Antuono also questioned why the search would target presidential records as well as classified records, particularly because the May subpoena had only sought the latter.

“We are not the presidential records police,” D’Antuono said, according to people familiar with the exchange.

Later, D’Antuono asked if Trump was officially the subject of the criminal investigation.

“What does that matter?” Bratt replied, according to the people. Bratt said the most important fact was that highly sensitive government records probably remained at Mar-a-Lago and could be destroyed or spirited away if the FBI did not recover them soon.

FBI agents on the case worried the prosecutors were being overly aggressive. They found it worrisome, too, that Bratt did not seem to think it mattered whether Trump was the official subject of the probe. They feared any of these features might not stand up to scrutiny if an inspector general or congressional committee chose to retrace the investigators’ steps, according to the people.

Jason Jones, the FBI’s general counsel who is considered a confidant of FBI Director Christopher A. Wray, agreed the team had sufficient probable cause to justify a search warrant. D’Antuono agreed, too, but said they should still try to persuade Corcoran to let them search without a warrant, the people said.

The disagreement over seeking Corcoran’s consent centered partly on how each side viewed Trump’s lawyer. The prosecutors — as well as some officials at FBI headquarters — were highly suspicious of him and feared that appealing to Corcoran risked that word would spread through Trump’s circle, giving the former president or his associates time to hide or destroy evidence, according to people familiar with the internal debate.

Some FBI agents, on the other hand, had more trust in Corcoran — a former federal prosecutor who had recently returned to practicing law and represented Stephen K. Bannon, a former Trump adviser, against criminal contempt charges. The agents drafted a possible script they could use to pitch to Trump’s lawyer on a consensual search. D’Antuono’s team said they could keep surveillance on Mar-a-Lago and act quickly if they saw any scramble to move evidence. The prosecutors refused, saying it was too risky, the people said.

In the meeting, some attendees viewed Toscas, a Justice Department veteran who had worked with the FBI through the Crossfire Hurricane and Clinton email investigations, as a prosecutor whose words would carry special weight with the FBI agents. He told D’Antuono he had shared the agents’ skepticism, but was now “swayed” that the evidence was too strong not to get a search warrant, according to people familiar with the discussion.

“George, that’s great, but you haven’t swayed me,” D’Antuono replied.

Jones, the FBI’s general counsel, said he planned to recommend to Deputy FBI Director Paul Abbate that the FBI seek a warrant for the search, the people said. D’Antuono replied that he would recommend that they not.

The raid

But prosecutors appeared unwilling to wait and debate further, according to people familiar with the discussions. Olsen, the assistant attorney general for national security, appealed to senior officials in FBI headquarters to push their agents to conduct the raid. Abbate handed down his instructions a day later: The Washington field office led by D’Antuono would execute the surprise search.

On Aug. 5, FBI agents quietly sought and received approval from a federal magistrate judge in Florida to search Mar-a-Lago for documents. The search was planned for the following Monday, Aug. 8.

Prosecutors remained somewhat on guard until the day of the raid, as they continued to hear rumblings of dissent from the Washington field office, according to three people familiar with the case. Some of the people said prosecutors heard some FBI agents wanted to call Corcoran once they arrived at Mar-a-Lago and wait for him to fly down to join them in the search; prosecutors said that would not work.

Just days before the scheduled search, prosecutors got a request from FBI headquarters to put off the search for another day, according to people familiar with the matter. The FBI told prosecutors the bureau planned to announce big news that week — charges against an Iranian for plotting to assassinate former national security adviser John Bolton — and did not want the impact of that case to be overshadowed or complicated by media coverage of the Mar-a-Lago raid. It is common for the Justice Department and FBI to fine-tune the timing of certain actions or announcements to avoid one law enforcement priority competing with another. But prosecutors, fatigued by months of fighting with agents in the FBI’s field office, wanted no delay, no matter the reason, the people said. The search would proceed as scheduled.

FBI agents found ways to make the search less confrontational than it otherwise could have been, according to people familiar with the investigation: The search would take place when Trump was in New York and not in Palm Beach; the Secret Service would receive a heads-up a few hours before FBI agents arrived to avoid any law enforcement conflict; and agents would wear white polo shirts and khakis to cut a lower profile than if they wore their traditional blue jackets with FBI insignia.

On Aug. 8, FBI agents scoured Trump’s residence, office and storage areas, and left with more than 100 classified records, 18 of them top-secret. Prosecutors claimed vindication in the trove of bright color-coded folders that agents recovered.

Some documents were classified at such a restricted level that seasoned national security investigators lacked the proper authorization to look at them, leading to consternation on the prosecution team. They involved highly restricted “special access programs” that require Cabinet-level sign-off even for officials with top-secret clearances to review. The documents described Iran’s missile program and records related to highly sensitive intelligence aimed at China, The Washington Post previously has reported.

In late fall, Bratt and his team began sketching out the evidence that potentially pointed to Trump’s obstruction, with an expectation that the prosecutors together would soon make a recommendation on whether to charge the former president, according to people familiar with the case. Bratt’s team began to button up witness accounts and stress-test factual evidence against the law.

Meanwhile, in late October, amid news reports that Trump was looking to soon announce another bid for the presidency, Garland told aides he was seriously contemplating appointing a special counsel to take over the investigation, as well as a separate criminal probe looking at Trump and his allies’ effort to overturn the results of the 2020 election — a rare procedure designed to ensure public faith in fair investigations.

On Nov. 15, Trump took the stage in the Mar-a-Lago ballroom — at the same property where FBI agents had searched three months earlier — and announced that he would run for president again in 2024. The Justice Department’s national security division leaders who had pushed the FBI to be more aggressive pursuing Trump did not finish the investigation or reach a charging decision before a new chief took over.

On Nov. 18, Garland sent word to the prosecutors working on both of the probes to come to Justice Department headquarters for a meeting that morning. He wanted to privately inform them that he planned later that day to appoint a special counsel. Garland told them they could choose their next steps, but he hoped they would join the special counsel’s team for the good of the two investigations, people familiar with the conversation said.

Just after 2 p.m., Garland stood before cameras to announce he had appointed Smith to take over the investigations. Flanked by three of his top deputies, Garland said the Justice Department had the integrity to continue the investigations fairly but that turning them over to an outside prosecutor was “the right thing to do.”

“The extraordinary circumstances presented here demand it,” he added.

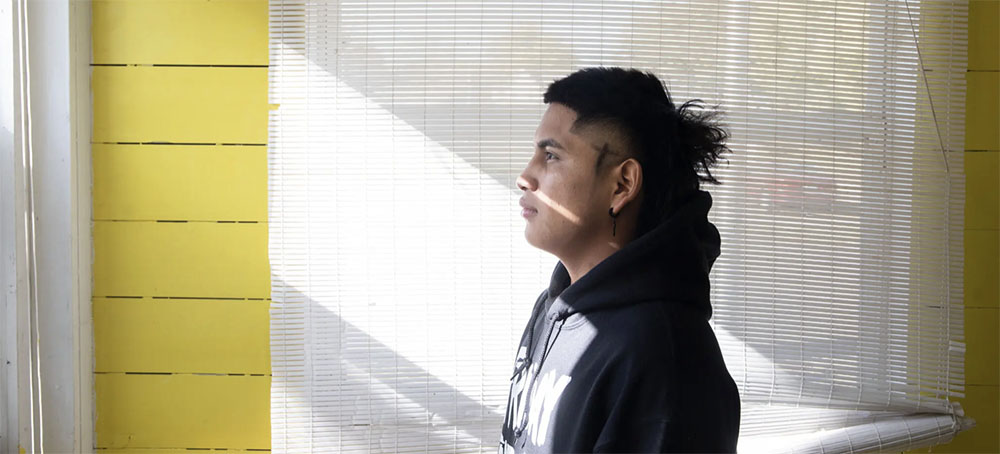

READ MORE  Oscar Lopez, a ninth grader, works overnight at a sawmill in South Dakota. On this day, he skipped school to sleep after a 14-hour shift. (photo: Kirsten Luce/NYT)

Oscar Lopez, a ninth grader, works overnight at a sawmill in South Dakota. On this day, he skipped school to sleep after a 14-hour shift. (photo: Kirsten Luce/NYT)

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: We begin today’s show looking at a shocking investigation by The New York Times exposing the forced labor of migrant children as young as 12 at factories across the United States. Over 100 unaccompanied migrant children, mostly from Central America, describe grueling and often dangerous working conditions, including having to use heavy machinery, being subjected to long hours and late-night shifts at facilities that manufacture products for major brands and retailers, such as Hearthside Food Solutions, the makers of Cheerios, Fruit of the Loom, Whole Foods, Target, Walmart, J.Crew, Frito-Lay and Ben … Jerry’s. Others were forced to work as cleaning staff at hotels, at slaughterhouses, construction sites, car factories owned by General Motors and Ford, in serious violation of child labor laws. At least a dozen migrant child workers have been killed on the job since 2017, according to The New York Times.

The disturbing revelations prompted the Biden administration to announce Monday a wide initiative to crack down on the labor exploitation of migrant children. White House Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre called The New York Times investigation “heartbreaking.”

PRESS SECRETARY KARINE JEAN-PIERRE: At the president’s direction, the Department of Labor and the Department of Health and Human Services announce new actions to crack down on child labor violations and ensure that sponsors of unaccompanied migrant children are vigorously, rigorously vetted. Child abuse — child labor is abuse, and it is unacceptable. Again, it is unacceptable. This administration has long been combating a surge in child exploitation, and today the Department of Labor and HHS announce that they will create a new interagency task force to combat child exploitation. They will also increase scrutiny of companies that do — that do business with employers who violate child labor laws, mandate follow-up calls for unaccompanied migrant children who report safety concerns to the HHS hotline, and audit the sponsor vetting process for unaccompanied migrant children over the next four weeks.

AMY GOODMAN: The Labor Department has already launched an investigation into Hearthside Food Solutions, which produces and packages food for other major companies, like General Mills, Frito-Lay and Quaker Oats. Democracy Now! reached out to Hearthside Food Solutions to invite a company spokesperson to join us on the program. They declined the request but sent us a statement to read on air. The statement reads, in part, “We take the allegations in the article seriously and have committed to these immediate next steps: We have engaged a renowned, global advisory firm, and an independent law firm, to conduct an independent review of Hearthside’s employment practices, third-party employee engagements, plant safety protocols, and our standards of business conduct. Following the review, we are committed to enhancing our policies and practices in line with our advisors’ recommendations,” they said.

For more, we’re joined by two guests. Hannah Dreier is the Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter at The New York Times whose major investigation, published Sunday on the front page, is headlined “Alone and Exploited, Migrant Children Work Brutal Jobs Across the U.S.” Her follow-up piece, published Monday, headlined “Biden Administration Plans Crackdown on Migrant Child Labor.” She’s joining us from here in New York.

You traveled to Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, Minnesota, South Dakota and Virginia for this story, speaking to more than a hundred migrant child workers in 20 states, Hannah. Can you lay out the scope of this investigation, what you found? And were you shocked by the speed of the Biden administration’s response? And your evaluation of what that is?

HANNAH DREIER: Thank you so much for having me, Amy.

I mean, when I started this reporting, I thought that we might find that some kids were working agricultural jobs, maybe dishwasher jobs. I never anticipated that we would find the scope of children working these really industrial, adult, dangerous jobs in all 50 states. So, really, what I discovered is, I think, a child labor scandal in this country. We have more and more kids coming over without their parents, and they’re being released to situations where they have to pay their own rent, provide their own living expenses. They’re under huge pressure to send money back home. And they’re ending up in some of the most brutal jobs in this country. So, I talked to kids outside of slaughterhouses when they were getting off their shifts at 7:00 in the morning. I talked to kids who are working as roofers at the top of buildings, kids who had gotten seriously injured. Like you say, we found many examples of kids who had died on these jobs.

And it’s in the supply chain of, you know, so many corporations. At the end of this reporting, I just felt like it was inescapable, like so many of the things that I personally consume, like Cheerios, have this labor somewhere in the supply chain.

And yeah, I mean, the response was overwhelming. We were told that the Biden administration worked over the weekend, and Biden approved these changes like on Sunday afternoon, a day after the story ran. It’s really gratifying. The people who I’m talking to believe that there’s still a lot to be done, but some of these changes really do seem like they will start to address this problem.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And, Hannah, in your investigation, how recent is this development? In other words, there was enormous pressure following the end of the Trump administration to remove unaccompanied minors from detention facilities. Is this a recent phenomena, or did this — has this been building for years now?

HANNAH DREIER: This is something that I think has been building for maybe the past 10 years, and part of it has to do with the changing nature of the children who are crossing the border. Ten years ago, there were far fewer children, maybe 6,000 children a year. Now we’re seeing 150,000 a year. And those children were often coming to reunite with their parents. So, they would cross the border and be released to a parent, who often would take care of them. Often that parent would have paid to have them brought up. And now what we’re seeing is it’s much more common for parents to be sending these children, and the children are under pressure to send back remittances. So the dynamic of who’s coming has changed.

And we’ve also seen a labor shortage. I’ve seen a couple dynamics that have sort of created a perfect storm for this phenomenon to really explode since 2021. And what the people who work with these kids out in the field are telling us is that they’ve seen this huge shift in the last three years — middle schools where every eighth-grader in the last three years has started working, federal investigators who used to focus on sex crimes and are now instead focusing on pulling 12- and 13-year-olds out of factory jobs. It’s been sort of a slow shift, and then, in the last two or three years, this really rapid change.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And your story indicates that HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra did put enormous pressure on other government agencies, as well as his own agency, to move the unaccompanied minors out of the detention facilities. How do you assess the role of Secretary Becerra?

HANNAH DREIER: You know, a lot of advocates, lot of people in immigration world were really excited about Becerra and about the change that they thought might happen at HHS after the Biden administration took over. But what happened was there was this huge crunch at the border, where all of a sudden children were sort of getting piled up in jails that are run by Customs and Border Protection, because there wasn’t enough capacity in the child welfare organization that’s supposed to take care of these children. That’s Health and Human Services. So there was suddenly all of this media attention to kids sleeping on the floor, sleeping under those silver space blankets.

And what people inside HHS say is that Becerra started putting immense pressure on them to discharge these kids more quickly. So, every day would start with a call, and the call would be “How many kids have been discharged from care today? How many kids are still there?” And what people who work at all levels of that agency say is that it created a situation where kids were being pushed out too quickly to people who weren’t vetted. And a lot of people inside the agency told me, you know, “He would always say, 'Why can't we run this like an assembly line? We need to be more efficient. Henry Ford would never have gotten rich if he had run his assembly lines like this.’” And I was very skeptical. I mean, that’s a really intense thing to say when you’re talking about the most vulnerable children in this country. But somebody eventually leaked us a video of him sort of berating staff and saying that on tape. So, I think he himself is probably under a lot of pressure, but there’s a lot of disappointment within the agency and among immigration advocates about how that’s been handled.

AMY GOODMAN: Hannah, I’d like to ask about the children. If you could tell us some of their stories? That’s really the heart of your story, as you talk about Cristian, who works in a construction job instead of going to school, 14 years old; Carolina, who packages Cheerios at night in a factory. Talk about each of them and also how you found them. How difficult was it for you to find them?

HANNAH DREIER: I mean, these kids were not hard to find. And I think that’s part of what you’re seeing with these Department of Labor reforms. Inspectors just have not been looking for them in a proactive way. I came to — I went to different cities and towns, and usually the next day I already was speaking to children who are working these illegal, exploitive jobs.

I talked to Cristian in southern Florida. He was living in a house full of other unaccompanied minors, other kids who had come across the border without their parents. All of them were working full time. None of them had gone to school. Cristian had come when he was 12, two years ago, and immediately, the next day, started working full time in construction. He told me that he doesn’t know how to read, and he would like to learn English, he would like to learn how to read, but he can’t go to school because he has a debt to pay off, he has to pay rent. And I went to a construction site and talked to him as he was putting the roof on a building, and he told me he had already fallen twice that year. He was working with power tools. He was just sort of balancing precariously on the edge as he was trying to bend some rebar. And, I mean, he’s a child. It’s not what he wants to be doing. But he was released to this situation, and there’s just sort of no support there for him to get out of it.

And in Michigan, I talked to a lot of children who are working in a factory packaging Cheerios. They also package Lucky Charms and Cheetos. And these are kids who were in school. I met them at school. And some of the kids I met at school told me, “Oh yeah, we have to leave early now because we have to go to our factory job.” And I was just shocked. But I went to this factory, and, sure enough, there they were, walking out after the shift. And this is a place where you’re working with really industrial machinery. The machines have sliced off people’s fingers. One woman who was doing this kind of work was pulled in by a hairnet, and her scalp was ripped open. I mean, it’s a serious, adult kind of place to work. And these kids are balancing it with, you know, seven days of school, as well, so they’re exhausted.

AMY GOODMAN: And tell us about Nery Cutzal from Guatemala, how they met their sponsor. Again, these children are here legally. And then talk about the children who have died.

HANNAH DREIER: I mean, I think that’s such an important point. These are not undocumented children. They’re not children who snuck in, and nobody ever found out about them, and now they’re sort of living a subterranean life. These are children who had turned themselves in at the border, usually asked for asylum, and were released to live with somebody who the government thought would protect them. The government can’t release them unless they’re sure that it’s a trustworthy adult who is taking these kids on. And in some cases, they’re being released to complete strangers.

So, in Nery’s case, he met a man on Facebook when he was 13. The man said that if he wanted to come to the U.S., he would help him. He would let him go to school. And instead, Nery shows up; the man picks him up from the airport and immediately hands him a list of debts that this kid now has. So he’s charging him thousands of dollars for his journey to this country. He charged him for filling out the paperwork that he had to send to the government in order to get him released. He charged him $45 for the dinner of tacos that they had that night. And then he told Nery that he had to go find his own place to live, find a job, and start paying back this debt. And, you know, Nery doesn’t speak any English. He has never worked. He was in school when he was in Central America. And we’ve seen the text messages between him and this man. The man starts threatening him and saying, “You don’t matter to me. I’m going to mess you up.” He threatened Nery’s family. And these kids are just on their own in these situations, with, you know, very little resources and very few ways out.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: You mentioned that federal inspectors generally are not looking for these kinds of violations, but I’m sure that several of these workplaces that you went to were unionized, to one degree or another. Is there any sense on your part that the organized labor movement was — that leaders in some of these places were aware of this? Because they could certainly complain, and therefore trigger some kind of inspection.

HANNAH DREIER: So, many of these children are coming in through staffing agencies. I had initially thought that the unions would be a really important resource in this reporting. And when I went to them, they told me, “No, there’s no children here. You know, we have these other sort of workplace issues.” But then, in some cases, I would go back to the same workplace and see children on the night shift.

And I think part of what’s going on here is there’s sort of two labor streams. There are the official employees, and those are people who have to provide government IDs. There’s a lot more regulation and protection. And then there are these kids who come in through the staffing agencies. And that’s like a total free-for-all, where the staffing agencies — people who work at the staffing agencies have told us that they know they’re sending children to work at these factories. People who sent children to work packaging Cheerios say they knowingly did this and that the factory knowingly accepted these kids. But because there’s sort of this one layer of remove, the factories don’t get in trouble. It’s the staffing agencies that get in trouble when there’s a crackdown.

AMY GOODMAN: And the children who have died, Hannah?

HANNAH DREIER: I mean, child labor laws exist for a reason. They’re not just there because kids should go to school and they should get enough sleep. They’re really there because this work is dangerous. Kids are much more likely to get injured on the job. And they’re supposed to protect kids’, like, physical safety.

So, what we found, talking to these kids who are working jobs that they’re not supposed to be in, that are illegal for children, is that the rate of injury is extremely high. And in some cases, children have died days after being released to a sponsor. In one case in Alabama, a 15-year-old fell 50 feet off of a warehouse where he was helping replace a roof. It was his first day on the job. He had been released to his brother. Here in Brooklyn, where I live, a 14-year-old was killed on his bike. He was a food delivery worker. And he was living in a house full of strangers, trying to send money back to his family, and was hit by a car. Another case that really struck me was a 16-year-old who died when he fell out of an earth mover that he was driving. And, to me, the idea that a 16-year-old would be in a position to be driving a 35-ton vehicle is just inconceivable. But this is what happens when you have kids working the jobs that for almost a century they’ve been specifically prohibited from being in.

AMY GOODMAN: I want to bring Greg Chen into this conversation. Hannah Dreier, who we’re talking to, is the Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times reporter who did this just jaw-dropping exposé, “Alone and Exploited.” Gregory Chen is the senior director of government relations for the American Immigration Lawyers Association. Can you talk about, legally, what recourse these children have?

GREGORY CHEN: Thank you so much for having me on the show here.

And this is an extremely challenging situation. And when you use the word “legally,” what recourse do these children have, the first thing that comes to mind for me, as a practicing lawyer who represented children back in the 1990s in San Francisco, is that children don’t have any knowledge or understanding of what their legal rights are. Many of these children who are coming from different countries, that have very limited English-speaking capacity or skills, and they simply won’t understand that there is legal system of labor laws to protect them. And they are also afraid that their immigration status here in the United States is going to be in jeopardy if they report any such violations.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And I wanted to ask you — in terms of response of the Biden administration, this is certainly one of the fastest responses by a government agency to an exposé that I can recall. Your sense of what some of the proposals are of the Biden administration to address this issue?

GREGORY CHEN: So, the announcements by the Biden administration are laudable in terms of the speed that they’ve implemented them or they’ve announced them. By and large, what they are talking about here is increasing Department of Labor and Health and Human Services investigations of these kinds of situations and also improving the screening and vetting of families that might sponsor these children, usually relatives who are going to take care of the children after they are released from government custody, which happens when they first arrive, and then, in addition, after these children are released, what kinds of post-release services are going to be given to these children to make sure to check on them, so that after a month or three months, you know, are they still living there, what is their health situation, are they going to school. Those are all steps that the federal government has announced they will be doing more of, because they haven’t been able to check on all these families.

What is missing here — and this is very important, given the fact that, as Hannah described — and what we’re seeing statistically is that the number of children coming to the United States, particularly from Central American countries, has increased dramatically, from — about 10 years ago, we had 13,000, 14,000 children coming every year. Now we are looking at 130,000 children that came just last year. And these are children who are fleeing persecution, violence and poverty. And many of them are afraid to come to the United States because of the challenges of crossing the border and because the United States has made it much more difficult to seek asylum. And when they get here, if they don’t have stable humanitarian legal release, such as asylum, they’re going to be afraid to report anything bad that happens to them while here in the U.S., including labor violations. So, what the Department of Homeland Security needs to do, and the Biden administration needs to do, is to look at more ways of ensuring asylum access and humanitarian protection for children and for other people who are coming here seeking protection.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And just briefly, because we have less than a minute on this segment, but I wanted to ask you in terms of the penalties that employers of these staffing agencies face. Just last week, the Department of Labor found a company called Packer Sanitation Services guilty of having 102 children as young as 13 years old working across eight states, and it only got a $1.5 million fine for that.

GREGORY CHEN: Yeah, so, the important thing here is that we need more resources put into investigations to ensure that fines and any other penalties can be imposed, and that Congress should be looking at this from a labor perspective. But I would also urge Congress to look at reforming our U.S. asylum laws and our U.S. immigration system overall. The fact is that the asylum system is closing, is becoming more restrictive, both because of congressional pressure and because the Biden administration is putting more blocks on asylum seekers being able to come here. And we haven’t had Congress reform our humanitarian or our family or employment-based visa system in three decades now. That’s 30 years where people who are coming here don’t have the pathways needed to have a safe, stable life here in the United States. And we have thousands, millions of people who are living here, including children, who are in that tenuous status. Anybody who is in a tenuous status that doesn’t have permanent legal status is going to be fearful of reporting labor violations like this. And that vulnerable, second-class population in the United States is not something that’s healthy for the country, even as immigrants contribute so much to our society, our communities and our economy.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, we want to thank you both so much for being with us, Gregory Chen, with the American Immigration Lawyers Association, and Hannah Dreier, for your superb exposé in The New York Times. We’ll link to your piece, “Alone and Exploited.” And just to read a few lines from that piece to underscore, “[While] H.H.S. checks on all minors by calling them a month after they begin living with their sponsors, data obtained by The Times showed that over the last two years, the agency could not reach more than 85,000 children. Overall, the agency lost immediate contact with a third of migrant children.”

Next up, we look at how Brazil’s new president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, could play a key role in peace talks to end the war in Ukraine. We’ll speak with his foreign policy adviser, Celso Amorim. Stay with us.

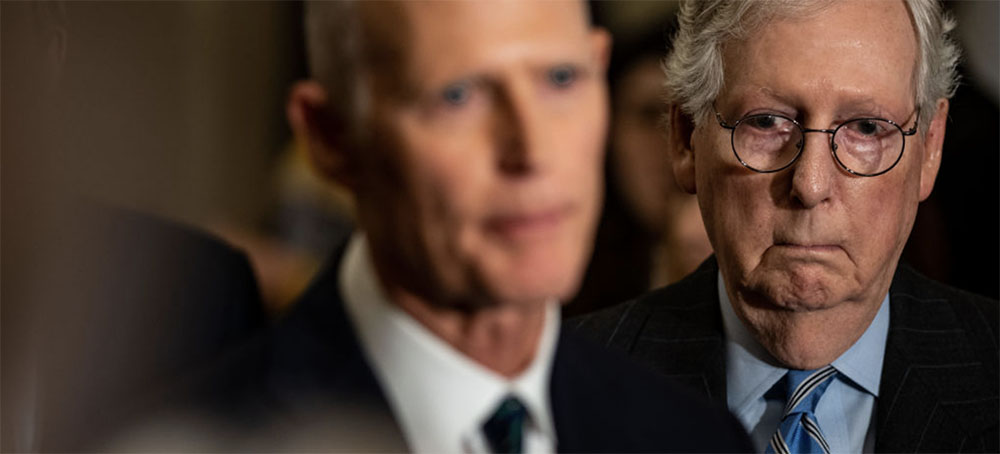

READ MORE Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY) listens as Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) speaks during a press conference on Capitol Hill, November 2022. (photo: Kent Nishimura/LA Times)

Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY) listens as Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) speaks during a press conference on Capitol Hill, November 2022. (photo: Kent Nishimura/LA Times)

Republicans hate Social Security and Medicare, but the programs’ universal structure makes them too risky to take on. We need more programs like that.

Scott appeared to relent the next day, saying he would now exclude Social Security, Medicare, and veterans’ benefits from the proposed “sunset” requirements. But then on Tuesday, he once again asserted the need to “fix” Social Security and Medicare, without specifying how. With this shift, Scott merely got in line with the more traditional Republican rhetoric about supposedly “fixing” or “strengthening” Social Security by privatizing it.

In the same Fox Business segment in which he finally got on-message about “fixing” Social Security and Medicare, Scott spoke with ghoulish glee about budget cutting, claiming that when he was governor of Florida he personally went through the state’s entire budget to find more programs to cut. “There’s four thousand lines in the budget in Florida. I went line by line and said, we are not going to fund this if it doesn’t meet its purpose,” Scott said.

That’s pretty standard Republican bluster — for everything except Social Security and Medicare. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy went through a similar song and dance a few weeks earlier before eventually backing off direct calls to cut the programs. Rick Scott’s recent comments stood out because, up until this week, he was embarrassing the party by saying too directly what most Republican politicians really think. Aside from the military and police, the GOP has barely ever seen a government program it didn’t want to reduce, hobble, privatize, or eliminate.

So what makes Social Security and Medicare different? Why are Republicans hesitant to go after these programs, and why do they couch their hostility to them in unusually tepid language when they do?

One immediate factor is Donald Trump. While Trump’s history on Social Security is muddled at best, more recently he has recently come out strongly against cuts to Social Security and Medicare. “Be careful, Rick, and most importantly fight for Social Security and Medicare. THERE WILL BE NO CUTS,” Trump posted on his Truth Social account last week.

As with most things Trump, it is unclear whether he actually believes what he says or whether the issue is simply a convenient cudgel to attack Ron DeSantis and other potential rivals. Either way, the rest of the GOP has been forced to react to his pronouncements, which in this case means a less aggressive stance against the popular programs than they might otherwise like.

But more importantly, the simple and universal structure of Social Security and Medicare makes them much harder to undermine. Nearly every voter in the United States either receives significant benefits from the programs or will in the future, and those who don’t currently receive benefits almost certainly know and love multiple people who do. Eligibility for the programs is virtually universal and enrollment is comparatively simple. The programs are minimally means-tested (though, unfortunately, not completely free of means testing), and comparatively easy for voters to understand. Lacking active grassroots movements to preserve and expand them and connect them to the greater common good, they might not quite qualify as “engines of solidarity.” But their broad, simple appeal makes them incredibly popular — and thus durable.

In short, they are unlike most social spending in the United States, which Democrats and Republicans alike have structured as convoluted patchworks of programs subject to complicated income and behavioral requirements that can vary significantly according to location, as can application processes and benefits. The fact that each program has its own separate eligibility criteria helps keep the constituencies for social spending atomized. When social spending programs are difficult to access and aren’t provided to many people who would benefit from them, they feel remote, or perhaps like charity. Since many voters are either only faintly aware of such programs, or perhaps upset that they don’t benefit from them, it is easy for Republicans to go “line by line” and cut them.

Unfortunately, while they might not have as much fun cutting social spending as the GOP, the Democratic Party has little interest in structuring social spending in a universal, and thus more durable, way. They have so far refused to budge on Republicans’ calls to cut Social Security and Medicare. That’s good, but rather than learn from what makes the programs so popular, Democrats have moved in the opposite direction. The party let broader social programs enacted during the pandemic, like universal free school lunch and an expanded child tax credit, expire before they had time to take root.

The elimination of the latter program was particularly egregious. No one denied it took millions of children out of poverty, and they were immediately thrown back into it as soon as the program was killed. Had the program continued for another decade, might it have become as untouchable as Social Security? For Democrats, it appears that was a liability, not an asset.

READ MORE  Members of the 'Mara 18' and 'MS-13' gangs are seen in custody at a maximum security prison in Izalco, Sonsonate, El Salvador, on Sept. 4, 2020. (photo: Yuri Cortez/AFP)

Members of the 'Mara 18' and 'MS-13' gangs are seen in custody at a maximum security prison in Izalco, Sonsonate, El Salvador, on Sept. 4, 2020. (photo: Yuri Cortez/AFP)

“A common-sense project,” Bukele called it.

The reality is that the scale of the project defies common sense — and easy comprehension. And the social implications of the endeavor are no less striking. The citizens of El Salvador have tacitly accepted Bukele’s unprecedented crackdown on crime, and, for the time anyway, are ignoring its broader ramifications.

The unveiling of the prison came in typical Bukelian fashion. He took over the country’s airwaves to share a 35-minute video of himself touring the facilities (it was soon posted on his popular Twitter feed, the presidency’s de facto press office). He can be seen arriving at the jail in a caravan of black SUVs. “Welcome to the Center for the Confinement of Terrorism, a key part in our battle against the gangs,” Osiris Luna Meza, director of El Salvador’s penitentiary system, said.

Bukele is then shown X-ray machines, surveillance towers and a fully staffed security perimeter. A “riot intervention squad,” armed to the teeth, salutes him. The tour then goes to the cells, meant to hold groups of “terrorists,” and the extreme solitary confinement area, where inmates will be kept completely in the dark — a widely condemned practice.

“They won’t see any daylight, Mr. President,” Luna Meza, whom the U.S. government has placed on a list of officials suspected of corruption in El Salvador, proudly told Bukele.

Spanning about 410 acres in an isolated region of El Salvador, the jail is the latest example of Bukele’s punitive state. And it is slated to become the largest, and most overcrowded, prison in the world.

The only images available come from the government itself. Since only a handful of foreign journalists have been granted access and given carefully arranged tours, claims of the jail’s readiness, layout and operation have not been independently verified.

The project’s finances have also been kept secret. “Contracts were granted capriciously,” reporter Jaime Quintanilla, who covers Bukele’s infrastructure projects, told me. “Nuevas Ideas [Bukele’s party, which controls Congress] passed legislation that allows them to skip basic accountability.” For now, the ministry in charge of such projects has sealed any information on the construction of the country’s jails. There is no official information as to which companies were granted the likely lucrative contracts to build it, although two of Bukele’s preferred contractors were apparently favored. “No one knows how it was all financed,” journalist Óscar Martínez, who runs the independent newspaper El Faro, told me. “If, in terms of security, this is similar to a dictatorship, in terms of public spending, this is already a dictatorship.”

The prison is no white elephant, however. It is a necessity born of Bukele’s policies. Since March of last year, his government has been prosecuting a war on the country’s infamous gangs. To do so, Bukele declared a state of emergency, which has since seemingly become permanent.

At least 60,000 Salvadorans have been imprisoned as a result of the crackdown, including hundreds of minors, often in what a recent joint report by Human Rights Watch and Cristosal calls “indiscriminate raids.” The report paints a chilling portrait of authorities run amok, arresting Salvadorans with “no apparent connections to gangs’ abusive activity,” sometimes acting merely on “appearance or social background.” As of November, 90 detainees had died in custody, according to the government’s own numbers.

Even before the crackdown, El Salvador had one of the highest incarceration rates per capita in the world. After the crackdown, the country might extend its lead in this grim statistic.

Incarceration figures in El Salvador have always been difficult to verify. We have only official figures, which have not been updated for the past year. Martínez, however, estimates the total number of prisoners in custody today to be around 100,000 people, a staggering figure for a country of 6.5 million.

Nevertheless, the arrests have succeeded in bringing down crime. According to official statistics, homicides decreased by more than a factor of 10 since 2015. Much of that decline cannot be attributed to the crackdown, even if homicides bottomed out at a remarkable low last year — a statistic Bukele frequently trumpets.

But the real sea change is on the ground, where citizens report that extortion has all but disappeared. Salvadorans have gained a palpable sense of security in their everyday lives at the expense of due process, democracy and transparency. Most seem to be fine with the trade-off. Bukele himself is immensely popular, as is the state of emergency he has declared. Protests against him have fizzled.

That said, nothing guarantees the long-term success of this extravagantly punitive approach. Systemic opacity has made it impossible for independent journalists to verify what it will cost Bukele to fund his sprawling security apparatus. Maintaining an indefinite state of emergency and a high incarceration rate won’t come cheap, and the country’s economy is not healthy.

He could also be playing with fire by creating such a huge police state. Security forces have a nasty habit of becoming powerful interest groups of their own, and could even attempt to seize power if their demands are not met.

And then there are the prisoners themselves. Leaving aside the very real human rights implications, Bukele’s strategy carries potentially big downside risks. Even if he manages to keep tens of thousands of “terrorists” behind bars, cut off from the world outside, gangs tend to thrive in jail. (In fact, some of El Salvador’s most notorious gangs grew inside the United States’ prison system.) Who is to say that these men, who are now being denied their rights and left to rot in questionable conditions, won’t eventually become a bigger threat? And after all, they cannot be detained indefinitely.

Salvadorans may yet come to regret their Faustian bargain.

READ MORE  The Norfolk Southern freight train that derailed in East Palestine, Ohio, was still on fire at midday on Feb. 4, the day after the crash. (photo: Gene J. Puskar/AP)

The Norfolk Southern freight train that derailed in East Palestine, Ohio, was still on fire at midday on Feb. 4, the day after the crash. (photo: Gene J. Puskar/AP)

Revealed: The US is Averaging One Chemical Accident Every Two Days

Carey Gillam, Guardian UK

Gillam writes: "Such accidents are happening with striking regularity."

Guardian analysis of data in light of Ohio train derailment shows accidental releases are happening consistently

But such accidents are happening with striking regularity. A Guardian analysis of data collected by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and by non-profit groups that track chemical accidents in the US shows that accidental releases – be they through train derailments, truck crashes, pipeline ruptures or industrial plant leaks and spills – are happening consistently across the country.

By one estimate these incidents are occurring, on average, every two days.

“These kinds of hidden disasters happen far too frequently,” Mathy Stanislaus, who served as assistant administrator of the EPA’s office of land and emergency management during the Obama administration, told the Guardian. Stanislaus led programs focused on the cleanup of contaminated hazardous waste sites, chemical plant safety, oil spill prevention and emergency response.

In the first seven weeks of 2023 alone, there were more than 30 incidents recorded by the Coalition to Prevent Chemical Disasters, roughly one every day and a half. Last year the coalition recorded 188, up from 177 in 2021. The group has tallied more than 470 incidents since it started counting in April 2020.

The incidents logged by the coalition range widely in severity but each involves the accidental release of chemicals deemed to pose potential threats to human and environmental health.

In September, for instance, nine people were hospitalized and 300 evacuated in California after a spill of caustic materials at a recycling facility. In October, officials ordered residents to shelter in place after an explosion and fire at a petrochemical plant in Louisiana. In November, more than 100 residents of Atchinson, Kansas, were treated for respiratory problems and schools were evacuated after an accident at a beverage manufacturing facility created a chemical cloud over the town.

Among multiple incidents in December, a large pipeline ruptured in rural northern Kansas, smothering the surrounding land and waterways in 588,000 gallons of diluted bitumen crude oil. Hundreds of workers are still trying to clean up the pipeline mess, at a cost pegged at around $488m.

The precise number of hazardous chemical incidents is hard to determine because the US has multiple agencies involved in response, but the EPA told the Guardian that over the past 10 years, the agency has “performed an average of 235 emergency response actions per year, including responses to discharges of hazardous chemicals or oil”. The agency said it employs roughly 250 people devoted to the EPA’s emergency response and removal program.

‘Live in daily fear of an accident’

The coalition has counted 10 rail-related chemical contamination events over the last two and a half years, including the derailment in East Palestine, where dozens of cars on a Norfolk Southern train derailed on 3 February, contaminating the community of 4,700 people with toxic vinyl chloride.

The vast majority of incidents, however, occur at the thousands of facilities around the country where dangerous chemicals are used and stored.

“What happened in East Palestine, this is a regular occurrence for communities living adjacent to chemical plants,” said Stanislaus. “They live in daily fear of an accident.”

In all, roughly 200 million people are at regular risk, with many of them people of color, or otherwise disadvantaged communities, he said.

There are close to 12,000 facilities across the nation that have on site “extremely hazardous chemicals in amounts that could harm people, the environment, or property if accidentally released”, according to a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report issued last year. These facilities include petroleum refineries, chemical manufacturers, cold storage facilities, fertilizer plants and water and wastewater treatment plants, among others.

EPA data shows more than 1,650 accidents at these facilities in a 10-year span between 2004 and 2013, roughly 160 a year. More than 775 were reported from 2014 through 2020. Additionally, after analyzing accidents in a recent five-year period, the EPA said it found accident-response evacuations impacted more than 56,000 people and 47,000 people were ordered to “shelter-in-place.”

Accident rates are particularly high for petroleum and coal manufacturing and chemical manufacturing facilities, according to the EPA. The most accidents logged were in Texas, followed by Louisiana and California.

Though industry representatives say the rate of accidents is trending down, worker and community advocates disagree. They say incomplete data and delays in reporting incidents give a false sense of improvement.

The EPA itself says that by several measurements, accidents at facilities are becoming worse: evacuations, sheltering and the average annual rate of people seeking medical treatment stemming from chemical accidents are on the rise. Total annual costs are approximately $477m, including costs related to injuries and deaths.

“Accidental releases remain a significant concern,” the EPA said.

In August, the EPA proposed several changes to the Risk Management Program (RMP) regulations that apply to plants dealing with hazardous chemicals. The rule changes reflect the recognition by EPA that many chemical facilities are located in areas that are vulnerable to the impacts of the climate crisis, including power outages, flooding, hurricanes and other weather events.

The proposed changes include enhanced emergency preparedness, increased public access to information about hazardous chemicals risks communities face and new accident prevention requirements.

The US Chamber of Commerce has pushed back on stronger regulations, arguing that most facilities operate safely, accidents are declining and that the facilities impacted by any rule changes are supplying “essential products and services that help drive our economy and provide jobs in our communities”. Other opponents to strengthening safety rules include the American Chemistry Council, American Forest … Paper Association, American Fuel … Petrochemical Manufacturers and the American Petroleum Institute.

The changes are “unnecessary” and will not improve safety, according to the American Chemistry Council.

Many worker and community advocates, such as the International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace … Agricultural Implement Workers of America, (UAW), which represents roughly a million laborers, say the proposed rule changes don’t go far enough..

And Senator Cory Booker and US Representative Nanette Barragan – along with 47 other members of Congress - also have called on the EPA to strengthen regulations to protect communities from hazardous chemical accidents.

“The East Palestine train derailment is an environmental disaster that requires full accountability and urgency from the federal government. We need that same urgency to focus on the prevention of these chemical disasters from occurring in the first place,” Barragan said in a statement issued to the Guardian.

‘We’re going to be ready’

For Eboni Cochran, a mother and volunteer community activist, the East Palestine disaster has hardly added to her faith in the federal government. Cochran lives with her husband and 16-year-old son roughly 400 miles south of the derailment, near a Louisville, Kentucky, industrial zone along the Ohio River that locals call “Rubbertown.” The area is home to a cluster of chemical manufacturing facilities, and curious odors and concerns about toxic exposures permeate the neighborhoods near the plants.

Cochran and her family keep what she calls “get-out-of-dodge” backpacks at the ready in case of a chemical accident. They stock the packs with two changes of clothes, protective eyewear, first aid kits and other items they think they may need if forced to flee their home.

The organization she works with, Rubbertown Emergency Action (React), wants to see continuous air monitoring near the plants, regular evacuation drills and other measures to better prepare people in the event of an accidental chemical release. But it’s been difficult to get the voices of locals heard, she says.

“Decision-makers are not bringing impacted communities to the table,” she said.

In the meantime React is trying to empower locals to be prepared to protect themselves if the worst happens. Providing emergency evacuation backpacks to people near plants is one small step.

“Even in small doses certain toxic chemicals can be dangerous. They can lead to long term chronic illness, they can lead to acute illness,” Cochran said. “If there is a big explosion, we’re going to be ready.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.