Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

An unusual and little-noticed missive from the former president maps out his defense against any charges relating to January 6.

Yet attached was something different from the usual: a more-than-nine-page document, double-spaced and footnoted, that seems to preview the defense Trump would use if he is charged in connection with the violent insurrection that day in 2021. The points it makes add up to a message that is extremely unconvincing as a matter of common sense—everyone saw what happened and how Trump encouraged the riot, and evidence since then has only reinforced his culpability—but might sow enough doubt with a jury to derail a conviction.

READ MORE  Louisiana State Police also released bodycam footage on Thursday, showing the moment Alonzo Bagley, 43, was shot dead near his apartment. (photo: Louisiana State Police)

Louisiana State Police also released bodycam footage on Thursday, showing the moment Alonzo Bagley, 43, was shot dead near his apartment. (photo: Louisiana State Police)

Louisiana State Police also released bodycam footage on Thursday, showing the moment Alonzo Bagley, 43, was shot dead near his apartment.

The cop, Alexander Tyler, has been charged with negligent homicide nearly two weeks after Alonzo Bagley, 43, died at his apartment complex on Feb. 3 following a call to police by his wife.

“Detectives with the Louisiana State Police Bureau of Investigations have reviewed body worn camera footage and other relevant evidence,” state police said in their announcement Thursday afternoon. “Based on their findings and in coordination with the Caddo Parish District Attorney’s Office, Troopers arrested Shreveport Police Officer Alexander Tyler this morning.”

Along with announcing the arrest, police also released some bodycam footage and a recording of the 911 call placed the evening Bagley was killed.

Bagley’s family said the footage proved he should not have lost his life that day.

“Alonzo was just so, so scared,” the family’s attorney, Ron Haley, said in a statement. “Everyone at the scene, including the perpetrator Alexander Tyler, knew Mr. Bagley should not have been shot that night. He wasn’t a threat. He deserved to live.”

According to the arrest warrant, police were called to Bagley’s home by his wife, who said he was drunk and threatening her and her daughters. After cops arrived, Bagley went into his bedroom, attempted to “grab something off a nightstand,” and then fled the apartment by jumping over the balcony handrail, police said. As Bagley ran through the apartment complex, Tyler shot him in the chest in an entryway.

“Oh, Lord. Oh, God. You shot me,” Bagley, who had his empty hands in the air, told the officer, according to the filing. Tyler and another officer called to the scene attempted to administer aid, but he was later pronounced dead.

According to the affidavit, Tyler, 23, told police that Bagley had approached him and that he “could not see his hands.” But the warrant states that “there were no known reports made to the responding officers that [Bagley] was in possession of a dangerous weapon…[and] no articulable facts were provided… that would justify the need for deadly force.”

In one of the bodycam videos released, two officers can be seen knocking on the door of Bagley’s apartment. He answers with a liquor bottle in hand and declines to step outside, then claims he needs to put his dog away and walks back into the apartment.

Officers follow him into a back bedroom and see Bagley jumping over the balcony outside the room. The officer wearing the body camera leaves the apartment to follow Bagley as he runs through the apartment complex. At one point, a loud gunshot rings out and Bagley can be seen collapsing against the side of a building. Another officer, who is already outside, then walks with a gun toward Bagley.

A second video shows Tyler chasing Bagley with his gun in his hand, before he cuts around a corner of a building and shoots.

“No, no, no, man! C’mon, dude!” Tyler anxiously pants, seemingly surprised at the severity of Bagley’s injuries.

At a press conference with Bagley’s family on Thursday afternoon, Haley said, “Flight is not a death sentence. Flight does not mean shoot to kill. Flight does not mean judge, jury and executioner. And that's what happened here.”

He questioned overall policing in the country, claiming no amount of training can remove cops’ bias towards Black and brown men. He slammed Shreveport police and accused Tyler of having previous disciplinary issues. Alternatively, he commended Louisiana State Police for taking swift action.

Bagley’s brother, Xavier Sudds, said he didn’t understand why Tyler immediately pulled his gun out.

“As a police officer, you have a calling to protect and serve,” he said. “I don’t feel like Shreveport police protected or served Alonzo Bagley, my brother, a son, a husband. They failed miserably.”

Bagley’s family criticized the local city government, claiming the mayor hadn’t provided any comfort in the nearly two weeks since Bagley’s death. Some also felt Tyler wasn’t properly charged.

“It honestly got me seeing him take his last breath. It really broke my heart; my heart’s still broken,” Sudds said. “I’m gonna keep saying that this is painful. I'm hurting. My family is hurting. We’re hurting as a people, and a call to justice is what is needed.”

In an interview with local news outlet KSLA following the presser, Tyler’s attorney, Dhu Thompson, said no officer ever wants to be in a situation like his client.

“All good officers don’t go out on the street, you know, wanting to shoot somebody in this situation,” he said. “He was put in an unfortunate situation. He’s not cavalier about this. He’s just as shook about this incident as any other reasonable officer would be.”

Gregory O’Neal, a childhood friend of Bagley’s, told The Daily Beast on Thursday that he’s still struggling to process what happened after viewing the “devastating” bodycam footage.

O’Neal and Bagley met as kids, and their friendship continued into their adulthood. They shared the same birthday, had mutual friends, and grew up in the same neighborhood, where O’Neal eventually became president of the residential association, he said.

“Being involved in a neighborhood and just seeing what’s going on in the community and then seeing things that are going on in the world, it’s definitely devastating when a person you grew up with ends up in a situation like this,” O’Neil explained.

According to CNN, Bagley sued Shreveport police officers, accusing them of assaulting him during a 2018 arrest. It’s unclear how that lawsuit was resolved.

O’Neal speculated that Bagley may have run away from the officers because of his previous encounter with police.

“I think the officer responded out of—I’m not gonna say fear, but he had different options he could’ve chose[n],” O’Neal told The Daily Beast. “Just firing a shot, there are a lot of other opportunities that he could have taken at that point.”

READ MORE  East Palestine community holds meeting over health and safety concerns but Norfolk Southern Corporation skips event. (photo: AP)

East Palestine community holds meeting over health and safety concerns but Norfolk Southern Corporation skips event. (photo: AP)

ALSO SEE: What's Known About the Toxic Plume From the Ohio Train Derailment

Officials for the railroad company pulled out hours earlier, infuriating some residents who said they wanted answers from the company.

The mayor pleaded with the crowd at East Palestine High School to remain civil as they called out questions and occasionally booed after answers. The meeting was the latest effort to quell concerns and ballooning distrust, nearly two weeks after a Norfolk Southern freight train derailed and a controlled burn of chemicals onboard forced residents to evacuate temporarily.

Linda Murphy, 49, who attended the meeting with her husband, Russell, pressed officials about the difficulty of getting her water tested. Dead fish were turning up in a creek near her house, Ms. Murphy said, and the smell of chemicals hung in the air. “I don’t understand how we can have this issue and everything is O.K.”

READ MORE  Gov. Glenn Youngkin delivers his State of the Commonwealth address. (photo: Alexa Welch Edlund/Times-Dispatch)

Gov. Glenn Youngkin delivers his State of the Commonwealth address. (photo: Alexa Welch Edlund/Times-Dispatch)

Glenn Youngkin essentially kills bill passed in Democratic-led state senate to ban search warrants for menstrual data on tracking apps

A bill passed in the Democratic-led state senate, and supported by half the chamber’s Republicans, would have banned search warrants for menstrual data stored in tracking apps on mobile phones or other electronic devices.

Advocates feared private health information could be used in prosecutions for abortion law violations, after a US supreme court ruling last summer overturned federal protections for the procedure.

But Youngkin, who has pushed for a 15-week abortion ban to mirror similar measures in several Republican-controlled states, essentially killed the bill through a procedural move in a subcommittee of the Republican-controlled House.

Citing unspecified future threats to the ability of law enforcement to investigate crime, Maggie Cleary, Youngkin’s deputy secretary of public safety, told the courts of justice subcommittee it was not the legislature’s responsibility to restrict the scope of search warrants.

“While the administration understands the importance of individuals’ privacy … this bill would be the very first of its kind that I’m aware of, in Virginia or anywhere, that would set a limit on what search warrants can do,” she said, according to the Washington Post.

“Currently any health information or any app information is available via search warrant. And we believe that should continue to be the case.”

The panel voted on party line to table the bill, meaning it is unlikely to resurface during the current legislative session.

Abortion rights advocates contend that with Youngkin’s efforts to push a 15-week abortion ban, with limited exceptions, failing to advance in either legislative chamber, the governor is looking for other avenues.

“The Youngkin administration’s opposition to this commonsense privacy protection measure shows his real intentions, to ban abortion and criminalise patients and medical providers,” said Tarina Keene, executive director of Repro Rising Virginia, in a statement provided to the Guardian.

Youngkin has insisted that any abortion restrictions would target doctors, not women who have the procedure.

The administration has also attempted to portray a united front among Republicans for abortion restrictions, arguing it is a consensus issue. But the defection of the nine senate Republicans over the menstrual data bill follows one of their number, Siobhan Dunnavant, speaking out last month against Youngkin’s 15-week proposal.

Dunnavant, an ob-gyn doctor, condemned the bill as “extreme”, according to the Virginia Mercury, and said she could not support it unless it contained an exception for severe fetal abnormalities to 24 weeks. Under current Virginia law, the procedure is legal for all women until the 27th week of pregnancy.

The wrangle over menstrual data tracking has parallels with a controversy in Florida, in which high school athletics officials last week backed away from a “humiliating” proposal requiring girls who wanted to play sports to answer questions about menstruation on medical forms.

Critics said the requirement aligned with a push by the Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, to curtail transgender rights, an allegation denied by high school officials.

READ MORE  The Tesla gigafactory in South Buffalo. (photo: Chris Caya/WBFO News)

The Tesla gigafactory in South Buffalo. (photo: Chris Caya/WBFO News)

Tesla Workers United, the group who are leading the unionization attempt, have filed a complaint with the U.S. National Relations Board alleging that Tesla has illegally terminated the employees "in retaliation for union activity and to discourage union activity."

If successful, the Buffalo workers would be the first union at the multi-billion dollar company, since previous unionization efforts have failed. The union push at the gigafactory is happening with support from Workers United Upstate New York, the group who facilitated the first unionized Starbucks in the country on Elmwood Avenue in Buffalo.

Sara Costantino is a worker and member of the organization committee to form a union at the plant. She spoke with WBFO’s Holly Kirkpatrick about this week's events. Listen to the interview by clicking the link at the top of the page, or read the transcript, below.

WBFO: You're part of the organizing committee for Tesla Workers United who announced Tuesday that you intend to form a union along with Workers United Upstate New York. However, it was reported that yesterday that dozens of people were terminated or let go from the Tesla gigaplant in Buffalo. What happened yesterday?

Costantino: Well, we walked in the door and everything was going pretty normal. And then a few people were walked out and their desks were boxed up. And we were a little worried. And then more people came out, and were walked out, and we got scared. And then it just became more and more and more, and we got angry. This isn't okay.

WBFO: How many people were fired yesterday from Tesla?

Costantino: We have about 30 that we're aware of.

WBFO: And are you aware of the reason they were told that they were being let go?

Costantino: They were told it was for performance reasons. Now we have performance reviews every six months; these reviews weren't supposed to happen until the end of March. So they moved that timeline up.

WBFO: How did other workers there react?

Costantino: I think we were all on the same boat. Like truthfully, I think in the beginning, it was like, what the heck is going on? And then it was, are we all losing our jobs? And then it was, oh, so you think you can scare us?

WBFO: Can we just talk a little bit about why you intend to form a union? What are the goals or the desired outcomes for you?

Costantino: Of course, our biggest thing right now is that we just want a voice with our company. We have no way of really fighting for things that we want, whether that's work from home privileges, whether that's better vacation, sick pay, whether that's flex scheduling, we can start earlier, start later, or whatever it is, we don't have that voice. And that's really our biggest thing we're fighting for right now.

WBFO: The Tesla CEO Elon Musk has voiced his opposition to labor unions in the past, and other unionization efforts at Tesla haven't been successful, including some efforts that happened at South Buffalo as well. What makes you think that this attempt is different?

Costantino: I think this time, we're just so exhausted. It doesn't matter what they hand us, doesn't matter what they're going to do to us. We're going to fight. We deserve to be here. We believe in what Tesla is doing. And we want to be a part of it. But it should be better for us.

WBFO: You do sound like you enjoy working there somewhat -you say that you believe in what Tesla does.

Costantino: I truly love my job. It's just we deserve better. And I will fight for that. You know, I don't think anyone should work for a company who sees them as robots.

WBFO: Sara Costantino, thank you for your time today

Costantino: Thank you, Holly, I appreciate it.

WBFO called Tesla on their number provided online, but was unable to get through.

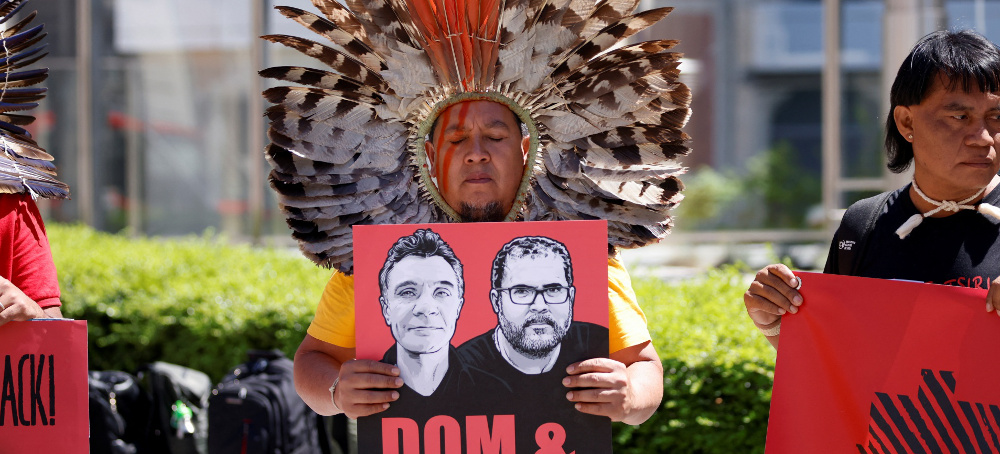

READ MORE  People attend a service honoring Dom Phillips and the Bruno Pereira in São Paulo, Brazil, in July 2022. (photo: Marcelo Chello/AP)

People attend a service honoring Dom Phillips and the Bruno Pereira in São Paulo, Brazil, in July 2022. (photo: Marcelo Chello/AP)

Visit is part of push by Lula’s government to beat back illegal miners, loggers and poachers who wrought environmental havoc

Leaders of Univaja, the Indigenous association for which Pereira worked in Brazil’s Javari Valley, said senior politicians, including justice minister Flávio Dino and the minister for Indigenous peoples Sônia Guajajara, would travel there on 27 February.

The visit is part of a high-profile push by president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s new government to beat back the illegal miners, loggers and poachers who wrought environmental havoc during the four-year term of his far-right predecessor Jair Bolsonaro.

Last week special forces operatives from the environmental protection agency Ibama and federal police launched what is expected to be a months-long operation to drive tens of thousands of illegal miners from the Yanomami Indigenous territory after claims its 28,000 inhabitants had faced “genocide” under Bolsonaro.

Beto Marubo, one of Univaja’s main leaders, said the government delegation would be taken to the decrepit riverside base which guards the entrance to the Javari Valley territory, the world’s largest refuge for Indigenous tribes living in isolation.

The ministers would also be taken to the spot where Phillips, a British journalist who reported for the Guardian, and Pereira, a Brazilian Indigenous expert, were shot dead on 5 June last year as they traveled by boat down the Itaquai River.

“We will show them,” said Marubo. “This is going to be a historic moment.”

As the activists spoke, the Brazilian newspaper O Globo reported that the defense ministry planned to launch a “mega-operation” in the Javari Valley on the same day as the ministerial visit. The springboard for that operation will reportedly be Atalaia do Norte, the isolated river town Phillips and Pereira were trying to reach when they were attacked by a trio of men apparently enraged by Pereira’s defense of the region’s Indigenous communities.

The Univaja activists welcomed the new government’s moves to protect Indigenous communities and the environment but voiced skepticism about the “mega-operation”. Rather than a cinematic, headline-grabbing crackdown, Beto Marubo said they wanted to see a forceful, long-term intervention that would protect Indigenous communities and activists from ongoing violence.

“The threats continued [after Phillips and Pereira were murdered]. The invasions continue. We are constantly being threatened … No one is safe in our region – be they Indigenous people or those we call ‘the whites’,” said Paulo Marubo, Univaja’s president.

Paulo Marubo said urgent government action was now needed in the Javari Valley – which, as well as environmental crime, has become a major thoroughfare for cocaine produced over the border in Peru – “so that what happened to the Yanomami Indigenous territory doesn’t happen here”.

“We lost a great friend,” he said of Pereira. “And we do not feel safe on our own land … There is no security in our region … We are human beings too. We have lived on these lands for thousands of years … and we are the greatest protectors of the forest.”

The planned ministerial visit to the Javari is another highly symbolic gesture of how Brazil’s attitude towards the environment and environmental defenders has changed since power passed from Bolsonaro to Lula on 1 January.

After Phillips and Pereira went missing, Bolsonaro’s administration faced international condemnation for dragging its heels with the search effort. Bolsonaro claimed the men had embarked on an “ill-advised adventure”. No ministers visited the Javari region in the days or months after their murders.

Lula’s ministers, in contrast, have voiced solidarity with the families of the murdered men and the Indigenous communities whose plight they were chronicling when they died. After Lula’s election last year, his environment minister, Marina Silva, said the new government would battle to honour the memory of the rainforest martyrs killed trying to safeguard the Amazon.

READ MORE  Oxbow Calcining's Port Arthur plant, owned by Bill Koch, emits more than double the amount of sulfur dioxide than the average U.S. coal-fired power plant. (photo: Jacque Jackson/Grist)

Oxbow Calcining's Port Arthur plant, owned by Bill Koch, emits more than double the amount of sulfur dioxide than the average U.S. coal-fired power plant. (photo: Jacque Jackson/Grist)

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, or TCEQ, had installed an air monitor near the plant a few months earlier and was allowing Oxbow to capture nearly real-time data. The data was technically available to the public on request, but Oxbow was the only company in the state to have sought it — and it used the information to its advantage. Every time the wind blew in the direction of the monitor and the readings ticked upward, Holtham and other Oxbow employees were alerted. Then they improvised ways to decrease the brownish-yellow sulfurous plume spilling out of the smokestacks, stopping the company from running afoul of the law.

The Port Arthur plant was built in the 1930s and has been grandfathered in as an exception to the landmark federal environmental laws of the 1970s. The facility has four cavernous, cylindrical kilns that are constantly rotating, each about half the length of a football field. Raw petcoke, the bottom-of-the-barrel remainder from refining crude oil, is fed into the kilns and heated to temperatures as high as 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit — a fourth of the temperature of the surface of the sun. The intense heat helps burn off heavy metals, sulfur, and other impurities into the air. It emits more than double the amount of sulfur dioxide, which can cause wheezing and asthma attacks, than the average U.S. coal-fired power plant.

Holtham struggled to find the best way to stop setting off the monitor that January day. At 2 p.m., 12 hours into the ordeal, he increased the air being forced through one of the kilns, in hopes of dispersing the emissions. When that didn’t sufficiently decrease the sulfur dioxide readings, he contemplated shutting down one of the four kilns.

At 6 p.m., he finally turned one of them off. But the damage was already done: A year later when the data from the monitor was reviewed and certified, TCEQ staff would see that the facility had clearly exceeded the federal one-hour standard for sulfur dioxide by nearly 20 percent. The emissions were so high that they set off a monitor more than 2 miles away.

Such exceedances are bound to have an effect on human health. Studies have shown that even short-term exposure to sulfur dioxide can increase the risk of strokes, asthma, and hospitalization. Multi-city studies in China have found that a roughly 4 ppb increase in sulfur dioxide levels is correlated with a 1 to 2 percent increase in strokes, pulmonary diseases, and death. The asthma rate in the residential neighborhood surrounding the plant, West Port Arthur, which is more than 90 percent Black, is 70 percent higher than the national average, according to federal data. And Black residents in Jefferson County, where Oxbow is located, are 15 percent more likely to develop cancer and 40 percent more likely to die from it compared to the average Texan.

62%

Oxbow emissions often spiked above federal standards, hitting percentages as high as this in 2017-2018

In 2017 and the first half of 2018, Oxbow’s emissions often spiked above federal standards by as much as 47 ppb — 62 percent higher than the limit. And all through that time, Holtham and his colleagues continued to improvise. They turned down fans that spewed the emissions into the air, increased the amount of air forced through the kilns, and even tried a chemical treatment. They regularly turned off certain kilns when the sulfur readings at the monitor got too high.

Oxbow has argued that these operational changes were “experiments” that the company conducted to try to bring the plant into compliance. The goal, Oxbow lawyers have said, was to identify a set of operational conditions that would keep them in the good graces of regulators.

Oxbow acknowledges in court records that these “experiments” were conducted for at least a year. But a Grist analysis of 2.5 years of internal operational data shows that, for at least another year, Oxbow’s kiln modifications continued — and occurred primarily when the wind blew in the direction of the air monitor, a likely violation of the Clean Air Act. We spoke to more than 40 public health and environmental researchers, former Oxbow employees, and environmental attorneys and reviewed thousands of pages of legal filings and public records from state and federal agencies. We found that the data Oxbow collected — which was filed in a Texas district court during an unsuccessful suit against the company — show that high winds in the direction of the air monitor predicted decisions to shut down kilns, which reliably led to the monitor registering lower sulfur dioxide levels. About 40 percent of the time, at least one of a subset of kilns were shut down when the wind was blowing to the north.

However, when the wind was not blowing Oxbow’s pollutants toward the monitor throughout this one-year period, the facility did not alter its operations. By ensuring that the monitor was incapable of recording a comprehensive, untampered view of the facility’s emissions, experts say Oxbow flaunted environmental law — in essence, by guaranteeing any air violations would not be detected — and continued to deteriorate air quality in the area.

“There is clearly a criminal violation of the Clean Air Act,” said Joel Mintz, an emeritus professor of law at Nova Southeastern University in Florida and former enforcement attorney with the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA.

Mintz reviewed Grist’s findings and said that Oxbow’s actions are “fairly egregious” violations of the law. He added that the EPA should open “an investigation with the Justice Department pursuing criminal action.” Presented with Grist’s findings, an EPA spokesperson said the agency “will follow up based on the information” provided.

According to the latest public data, Oxbow still emits more sulfur dioxide than any facility in Texas aside from five coal- and gas-fired power plants. One simple but pricey solution is to install sulfur dioxide scrubbers, which run emissions through a slurry of chemicals to mitigate their toxicity. But for at least three decades, in four different states, Oxbow has been trying to outrun environmental regulations that might require this expensive step. Oxbow’s creative use of real-time official regulatory data has not only helped it stay in business — it’s also helped the company rake in an estimated $80 million in sales a year.

The costs of continuing to pollute are felt most acutely by those who live near the plants. The three plants Oxbow currently operates in Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma are the largest sulfur dioxide polluters in their respective counties — which combined are home to more than 750,000 people — and taken together emit more than 38,000 tons of sulfur dioxide a year.

“You gotta force air in because it feels like my lungs are closing up. You never get used to it.”

Ronald Wayne, a 65-year-old resident of West Port Arthur.

In 2021, environmental groups and a legal aid firm filed a civil rights complaint against TCEQ, asking the EPA to investigate Oxbow’s use of “dispersion techniques,” including the monitor alert system it set up. The groups also modeled sulfur dioxide concentrations based on Oxbow’s maximum permitted emissions. The model found the maximum concentration around the facility would have been eight times as high as the 75 ppb threshold.

The modeling results “demonstrate that Oxbow is likely emitting [sulfur dioxide] in amounts greater than in its permit,” the complaint claimed. “Without intervention from the EPA, this lax regulation of Oxbow’s operations is likely to continue.”

“They’ve been causing air quality conditions that we now know are harmful to human health since this thing began operating,” said Colin Cox, an attorney with the nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project, one of the groups that filed the complaint.

Brad Goldstein, a spokesperson for Oxbow, called Grist’s review of the company’s data “flawed” and said that the findings are “reckless and unsupportable.” He added that the company is “proud of its compliance record,” emphasizing that the sulfur dioxide readings at the monitors in Port Arthur are consistently below federal standards. “Oxbow values its reputation as a responsible corporate citizen and will vigorously defend it,” he said. Holtham, the plant manager, declined multiple interview requests. (Accounts of his activities are drawn from sworn depositions he provided in court.)

For those like Ronald Wayne, a 65-year-old longtime resident of West Port Arthur, the combined emissions from Oxbow and the town’s other industries have meant never getting used to the stench of sulfur, a rotten-egg smell that just “stink, stink, stink.” He’s woken up to find his car coated in a layer of thin yellow or black dust, and changes the ruined filters on his air conditioner three or four times a month.

Worst of all, he’s become accustomed to waking up in the middle of the night gasping for air. “You gotta force air in because it feels like my lungs are closing up,” Wayne said. “You never get used to it — and then again, there’s nothing you can do about it.”

The rules that Oxbow is required to follow are due to the fact that sulfur dioxide is one of six “criteria air pollutants” listed by the federal Clean Air Act, which requires the EPA to periodically assess them and set safe levels for their concentration in the air.

There’s no question that the act has resulted in tremendous gains in cleaning up the nation’s air. Sulfur dioxide levels nationwide have decreased by 92 percent since the 1990s, and the days of acid rain are well behind us. But in recent years, progress on improving air quality has stalled, if not reversed. Americans experienced more days of “very unhealthy” and “hazardous” air between 2018 and 2021 than anytime in the last two decades.

One reason for the hindered progress is the carve-out that the Clean Air Act of 1970 provided for polluting facilities that were already in operation when it was enacted, including at least two Oxbow facilities. In order to make the legislation politically palatable, these facilities were “grandfathered” in and were able to retain their original emissions limits as long as they didn’t significantly modify their operations. The provision provided a perverse incentive to keep old and dirty plants in operation and delay upgrading them.

Grandfathered facilities also benefit from another facet of the Clean Air Act: its prioritization of the concentration of pollutants, as opposed to volume. Since the Act requires counties to meet specific air quality concentration thresholds, dilution is often the preferred solution, rather than actually reducing the raw volume of pollutants that emerge from industrial processes. Some of these dispersion methods, such as increasing stack heights to legal limits or slowing the rate of emissions, are widely employed and legally permissible. Others, such as changing operations depending on climatic conditions, could be considered illegal.

By its own admissions in court, Oxbow conducted “75 experiments” from January 2017 through June 2018 in order to “see how various operating procedures would affect the dispersion of the plumes.” The “dispersion protocol” that the modeler and others developed involved changing the amount of air fed through the kilns, the amount of coke being processed, and operating temperature depending on one primary atmospheric condition: wind direction.

Such operational changes appear to violate the Clean Air Act under two separate provisions. One section prohibits dispersion techniques that include “any intermittent or supplemental control of air pollutants varying with atmospheric conditions.” Another clause lists penalties including up to two years in prison for any person who knowingly “falsifies, tampers with, renders inaccurate, or fails to install any monitoring device or method required to be maintained or followed.”

Mintz, the former EPA enforcement official, said that Oxbow’s activities appear to be in violation of these provisions. “They have knowingly rendered inaccurate their device,” said Mintz. “If they had some sort of permission from the government to experiment as they did, that might be a defense, but doing it unilaterally, I don’t think so. It would be up to a court to decide, but I don’t think that should be, in my judgment at least, a basis for not prosecuting them.”

Bill Koch is the lowest-profile of the famously wealthy Koch brothers. Known for their outsized role in Republican politics and helping gut government action on climate change, the Kochs have collectively given millions to conservative causes. But Bill Koch’s most public endeavors thus far have been his vendettas against those who have sold him counterfeit wine. He claims to have spent $35 million tracking down counterfeiters, including when a con man sold him four bottles allegedly owned by Thomas Jefferson for over $400,000.

When he’s not chasing after con artists, Koch runs Oxbow’s industrial empire, which operates a coal mine in Colorado and coke plants in Argentina, Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma. New environmental regulations have periodically led Oxbow to consider installing sulfur dioxide scrubbers at its coke plants, but for decades it found alternate ways to comply.

In 2010, however, the EPA dropped a bombshell by lowering the limit for ambient sulfur dioxide concentration from 140 ppb averaged over 24 hours to 75 ppb averaged over one hour. The rule, which withstood multiple legal challenges from industry, required that states draw up a list of the top sulfur dioxide emitters and require them to prove their emissions could stay within the new limits. At the time states began to implement the EPA’s plan, Oxbow operated plants in Illinois, Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma. In all four states, the company was shortlisted as a major sulfur dioxide polluter.

Oxbow’s plant in Lemont, Illinois, had already been the target of multiple EPA inspections and enforcement actions. It emitted as much as 7,000 tons of sulfur dioxide a year and was using an expired permit that appeared to cap emissions around half that. A monitor about two miles away was recording readings close to or above 100 ppb, which put it in the EPA’s and state’s crosshairs when the new sulfur dioxide rules took effect.

Oxbow had considered scrubbers but found they would cost north of $50 million — “not in the cards economically,” an executive would later recall. Given that it had about 30 percent extra capacity at its other plants, Oxbow shuttered the Lemont plant that year and spread its operations among the company’s other three locations.

Unwilling to put scrubbers in its other facilities as well, citing costs, Oxbow attempted to prove through its own modeling that its other plants could stay below the new 75 ppb standard. It’s unclear what the company’s internal modeling found, but Oxbow abandoned the effort in 2016 and elected to have state agencies place monitors near its plants instead. As David Postlethwait, the former plant manager of Oxbow’s facility in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, later put it, executives believed “the air models tend[ed] to overestimate emissions” and monitoring with “real data” would be more reliable. Modeling is the cheaper option — for both Oxbow and the state agencies. Monitors cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to purchase, install, and operate. Oxbow bore some of those costs.

The EPA must collect three years of data to determine compliance — meaning monitors bought the company at least three more years to comply with the rule. It was a common strategy: Of the 25 Texas facilities that were at risk of violating sulfur standards, more than half elected to show compliance through monitoring data.

As the state agencies in Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma purchased the monitors and decided where to install them, Oxbow set up a task force that came up with sophisticated software to track the monitors’ readings. Although the monitors were continuously recording sulfur dioxide readings every minute, the state environmental agencies at the time were only posting one-hour averages on the website. Oxbow wanted close-to-real-time data and negotiated access to directly download readings at five-minute intervals from the monitors. It could take up to 30 minutes before the readings reached Oxbow servers, but it provided enough of a lead time for plant managers to track when sulfur dioxide levels were ticking up.

Oxbow employees then gathered meteorological data — specifically wind direction and wind speed — and added it to the software that was recording the monitor readings. A number of plant managers, environmental engineers, and executives were given access to the data, and the software sent them emails when the wind was blowing in a 30-degree band over the monitor and recorded levels above a set threshold. The company replicated the system for its facilities in Louisiana and Oklahoma, similarly negotiating access for five-minute data from the respective state environmental agencies.

The fact that employees had spent months setting up this software was no secret. A senior Oxbow employee provided updates to Bill Koch. A December 2017 memo to Koch, made public in court filings, noted that employees were running “dispersion testing under various preselected scenarios for each facility when conditions warrant.”

Control room operators started noticing changes, too, once the monitors were installed. Milton Fuston, who was the main operator at the plant in Enid, Oklahoma, said that he received calls from a supervising engineer telling him to reduce the amount of coke being fed through the plant or to make other operational changes to reduce emissions. Some of these calls came during his night shifts, he said, when the engineer wasn’t at the plant. It led Fuston, who worked at the plant for more than a decade before leaving in 2019 when the long and taxing shifts began taking a toll on his body, to believe that the monitor readings were driving the changes.

“In the beginning, every one of my nights I’d get a call to shut it down,” Fuston told Grist, though he added that he wasn’t directly told about a strategy to avoid pinging the monitor. “Some days we’d go three days of shutting it down. [Other days they’d] let us spin, shut it down, let us spin, shut it down.”

Kurk Paul, who worked as a production supervisor at the Baton Rouge plant, recalled having to field complaints about the dust coming from the plant. Chad Sears, who worked at the Oklahoma plant, said the emissions were so thick that a public pool nearby was often covered in a layer of dust. Oxbow, he said, was paying for pool cleanup as a result.

“When you’re on the highway driving there in the summer, there’s so much dust and smoke in the air, it looks like the whole place is on fire,” Sears said. “It’s like a black hole.”

The clearest picture of Oxbow’s operations emerges in Port Arthur, where the company was sued by a contractor. Since the superheated coke has to be cooled down before it can be shipped off to customers, Port Arthur Steam Energy, or PASE, saw a business opportunity to capture the excess heat, use it to generate steam, and sell the steam to a nearby Valero refinery. A portion of the profits was to be shared with Oxbow. For many years it seemed like a win-win deal — and perhaps an efficient and even “green” process, since it used energy that otherwise would have gone to waste.

But the contractual relationship between Oxbow and PASE soured in 2017 after TCEQ installed the monitor. Oxbow claimed PASE’s operations were to blame for the Port Arthur plant’s high sulfur dioxide readings. The company said that when PASE captured the stream of hot gases as the coke was being processed and cooled it down, the emissions were released from its smokestacks at lower temperatures. As a result, the emissions were less likely to disperse into the air and more likely to be picked up by the monitor for exceeding limits. Oxbow ended its contract with PASE in June 2018 as a result, effectively running PASE out of business.

“They just killed this green-air process,” Ray Deyoe, one of the co-founders of PASE, told Public Health Watch and the Investigative Reporting Workshop. “Just because Bill Koch didn’t want to go sell one Picasso or one of his Billy the Kid statues or whatever to pay for his scrubbers in Port Arthur.” PASE sued, alleging that Oxbow had been trying to “game the monitor.”

PASE initially won in a Jefferson County court but lost the appeal. The companies then proceeded to arbitration, where a panel of former judges ruled in Oxbow’s favor, ordering PASE to pay administrative fees and $500,000 plus interest. When PASE appealed the judgment in a Harris County district court, it lost. While these proceedings bankrupted PASE, the litigation provides an incredibly detailed window into Oxbow’s operations. The discovery process and depositions led to Oxbow handing over thousands of pages of internal documents. Key among them is a spreadsheet of the five-minute data Oxbow collected from TCEQ’s monitor alongside information about whether each of its four kilns were on at any given time. The spreadsheet, which was filed in the Harris County court, contains wind direction, wind speed, sulfur dioxide monitor readings, and kiln behavior information at five-minute intervals from January 2017 through June 2019.

Grist analyzed the dataset from August 2018, after Oxbow ended its contract with PASE, to July 2019. We found that winds blowing north, high wind speeds, and periods in which the winds were shifting toward the monitor predicted shutdowns.

When we looked at monitor readings 24 hours before and after a kiln was shut down, we found that readings tended to spike in the 24 hours following a shutdown decision, while they were relatively stable in the preceding 24 hours — suggesting that shutdowns were executed in advance of known changes in environmental conditions.

Oxbow’s operations in March 2019 are particularly illustrative. Even with just two kilns operational, the readings began ticking upward in the early hours of March 8. That morning, Oxbow reduced the feed into two of the kilns by two tons per hour — but it seemed to make no difference. By lunchtime Oxbow had registered five-minute readings above 75 ppb even though by then it was operating at just 25 percent of its average capacity.

Nevertheless, ultimately the maneuvering worked. The wind changed direction, and the readings dropped enough to lower the average that would determine compliance. When the state regulator eventually crunched the numbers, it reported the highest one-hour average for March 8 as 49.2 ppb — well below the federal threshold.

In response to detailed questions about Oxbow’s operations in March 2019 and Grist’s analysis, Goldstein, the Oxbow spokesperson, said that the company “sees no reason to relitigate our previous dispute with PASE for your purposes.”

“The case is now closed,” he said. “Oxbow prevailed and the entire file is a matter of public record. The answers to your questions can be found at the courthouse.”

States have few incentives to intervene when allegations of gaming air monitors surface. After PASE executives dragged Oxbow into court, they met with TCEQ staff to explain how they believed the company was cheating the monitor. But nothing came of the meeting; TCEQ didn’t investigate whether Oxbow was using the data inappropriately.

“TCEQ was trying their best to get through this monitoring program and sort of sweep all of this under the rug,” said Ray Deyoe, a PASE co-founder. “Because here we are squealing about this … and instead of helping us and going in and really doing something about it, it just seemed like they were turning a blind eye.”

TCEQ continues to provide five-minute monitoring data to Oxbow. The agency told Grist that the information is public and available to anyone who seeks it — it’s just that no other company in Texas has.

High monitor readings spell trouble not just for Oxbow but the entire county, TCEQ, and the state. When the EPA finds that a county is in “nonattainment” of a certain ambient air quality standard, it requires the state to come up with a plan of action to cut pollution. The state environmental agency in turn typically requires polluting facilities in the entire county to reduce emissions, a costly and time-consuming endeavor. The process of developing such a plan is also expensive, taking up a significant amount of resources within the agency and racking up employee work hours. And if states don’t come up with a sufficiently stringent plan, the EPA can take over and withhold federal funding.

Louisiana appears to have followed Texas’ lead. The state Department of Environmental Quality did not respond to specific questions about the access that it gave Oxbow to monitoring data, but internal emails, available through court records, between Oxbow employees confirm that the company was able to access near real-time monitoring data for its Louisiana plant as well. During this time, the monitor did not register any sulfur dioxide levels above 75 parts per billion, and after three years of monitoring, the Louisiana environmental agency decommissioned the monitor and Oxbow was found to be in compliance with the air quality standard.

In Oklahoma, where Oxbow operates a calcining facility in Kremlin, roughly 100 miles north of Oklahoma City, regulators took a different tack. Initially, the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ, granted Oxbow the ability to access monitoring data directly. But a few months into the arrangement, the agency received an anonymous complaint that the company was using the data to change its operations such that it didn’t set off the monitor. As a result, the agency ended Oxbow’s access to the monitor.

“In order for DEQ to continue to certify to EPA that the data being gathered by the monitor is accurate and depicts the true [sulfur dioxide] levels that exist and will exist in the future, DEQ has determined that it can no longer provide five-minute data to Oxbow via the .csv link,” the then-air quality director wrote to Oxbow executives. A spokesperson for the agency told Grist that it never restored the company’s access. “No entity currently receives five-minute data,” the spokesperson said.

At more than 150 feet tall, Oxbow’s massive smokestacks stick out like beacons in the industrial corridor in Port Arthur. The yellowish-brown plume from the plant carries far and wide. When the cloud cover is low, the emissions stagnate, forming a sulfurous haze around the plant. Sometimes the stench is so strong that Hilton Kelley, a Goldman Environmental Prize winner and local activist, can smell the sulfur when he steps out of his restaurant, Kelley’s Kitchen, almost three miles away.

“It smells like somebody is tarring their roof,” Kelley said. “It can make your throat itchy and can make your eyes burn.”

Exactly how far the pollution is carried depends on a number of factors including the height and diameter of the stacks. The taller a stack, the farther the plume drifts. Tall stacks, a 2011 Government Accountability Report found, increase the distance that pollutants travel and harm air quality in regions further away. They do nothing, of course, to decrease the amount of pollution spewed into the air. Rather, taller stacks are a dodge to reduce the concentration of pollutants while doing nothing to decrease their magnitude. As a result, stack heights have risen steadily over the years.

The Port Arthur plant has had its stacks raised at least twice in the last few decades, once in 2005 before Oxbow’s purchase of the plant and again in 2018, when Oxbow found that the plant was violating sulfur dioxide limits. Holtham, the plant manager, notified TCEQ in September that Oxbow was replacing one of its stacks with a new structure that would be 20 feet taller — and almost three feet narrower, another strategy that forces emissions out higher into the air. The change “will provide additional loft of the plume” and “provide better dispersion from the Kiln 4 stack which will lower off-property ambient concentrations of air contaminants,” Holtham wrote. Oxbow’s stacks are now among the tallest in Texas, according to a Grist analysis of nearly 10,000 stacks at similar industrial operations.

Replacing the stack had a marked effect on the “experiments” that Oxbow was running. In 2017 and early 2018, prior to replacing the stack, Kiln 4 exhibited a similar shutdown bias to the other kilns when the wind blew in the direction of the monitor: It was down 11 percent of the time when the wind was blowing north (versus 8 percent for other wind directions). But in 2019, after the stack was raised, any such correlation between wind direction and whether the kiln was on disappeared. The overall wind-direction distribution at the site didn’t change, but after its replacement, Kiln 4 was virtually never shut down during periods when the wind blew in the direction of the monitor.

Oxbow continues to argue against installing scrubbers in filings with state regulators. Over the last couple years, states have been developing plans to reduce smog in national parks, and Oxbow’s facilities have been flagged as a major contributor to regional haze in all three states they operate in. The environmental agencies in Louisiana and Oklahoma required the company to conduct a “four-factor analysis” investigating different equipment that would reduce emissions, the cost of compliance, and any environmental impacts not related to air quality that may result. In Oklahoma, Oxbow claimed all three options that it explored were “economically infeasible.” In Louisiana, it claimed installing scrubbers would cost at least $88 million a year. And Texas’ plan to reduce regional haze left Oxbow out even though the Port Arthur plant releases more than 10,000 tons of sulfur dioxide a year, making it one of the largest polluters in the state.

Residents who live around the Oxbow facilities have been complaining about its pollution for years. Brannon Alberty, a pediatrician, first called the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, or LDEQ, about Oxbow in 2016. Alberty grew up in Baton Rouge and was used to seeing plumes spewing from smokestacks. But the plume from Oxbow’s facility was different. It had a hazy orangish-brown color and was bigger than anything he’d seen from any other facility in the area. Driving home from work on Highway 61, Alberty saw the plume multiple times a week.

“I’m not like an environmentalist or anything like that, but it’s just one of those things that clearly anybody can look at and say, ‘This isn’t right,’” he said.

Between 2016 and 2018, Alberty called LDEQ to report the plume multiple times. Each time, LDEQ checked the facility’s monitoring records and told him the company was operating within the limits established in its permit. Fed up, Alberty called local TV stations and newspapers. He called the EPA, and he even tried to get his neighbor, an attorney, to see if there was a class action lawsuit that could be filed. Eventually, Alberty decided to look at the health data he had access to at his hospital. He found that ER visits and asthma rates in the ZIP codes in and around Oxbow were two to three times higher than the rest of the state.

Armed with this information, he called the state epidemiologist’s office and flagged the numbers for them. The state health agency took his complaint seriously and in 2019 published a report on the childhood asthma rate in East Baton Rouge. The report doesn’t list Oxbow as the cause for higher asthma rates, but in a map of industrial facilities in the area, the company is named.

Like Alberty, John Beard has been complaining about Oxbow’s emissions in Texas for years. Beard, a local activist and executive director of the Port Arthur Community Action Network, has testified in front of the state legislature and shown up at TCEQ permit hearings, advocating for stricter emissions limits on Oxbow and other polluters. Most recently, Beard teamed up with an environmental group and a legal aid firm to petition the EPA to examine TCEQ’s decisions to renew two permits. The EPA sided with the environmental groups last year in one of the cases and has directed TCEQ to reexamine Oxbow’s recordkeeping and air quality monitoring requirements. The groups have also filed a separate civil rights complaint against TCEQ over Oxbow’s emissions with the EPA.

Specifically, the complaint requests that the agency look into TCEQ “tacitly approving Oxbow’s dispersion techniques,” by failing to investigate the company’s practices. The complaint has since been accepted by the EPA and the agency is currently investigating.

Oxbow did not respond to specific questions about whether it continues to run such experiments to this day. The data submitted to the court cover the company’s operations from January 2017 through June 2019. In a deposition in November 2019, Holtham, the plant manager, said that the company was still running experiments based on wind direction and other parameters because “we still have emissions” and “we want to find out what process parameters” to run in order to operate on a permanent basis.

According to TCEQ, the agency continues to provide near-real-time monitoring data to Oxbow. At the very least, Oxbow made operational changes based on wind direction from 2017 through half of 2019. If those experiments continue to this day, it raises serious questions about the validity of the monitoring data that the EPA relied on to certify Jefferson County’s air quality. In 2021, after examining air quality data from 2017 to 2020, the EPA declared that the county was in compliance with the sulfur dioxide standard.

Nevertheless, over his decades of advocacy on behalf of Port Arthur residents, Beard has come to identify Oxbow as a “serial polluter.”

“If you came to Port Arthur, walk the streets and you ran into someone and you ask them, ‘Do you know of anyone who either had cancer, died from cancer, [is] currently undergoing treatment, or has been treated for cancer,’ you will not find a single person of adult age who will tell you they don’t know of anybody in this whole city,” he said. “That’s scary. In a city of 55,000, that’s scary.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.