Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The speaker gave away his job security, but at least the House banned lobbyists from its gym.

It was the side agreements, though—the deals Speaker Kevin McCarthy made with hard-liners to resolve last week’s impasse that were not in the rules package—that caused the most angst before the vote.

[Read: A Complete List of Everything We Know Kevin McCarthy Gave Up to Be Speaker]

The most high-profile concession on the books was a restoration of a motion to vacate the chair—essentially a no-confidence vote in the speaker—to its pre-Pelosi status quo. This puts McCarthy under pressure to hew to the Freedom Caucus line right out of the gate.

When Pelosi regained the speakership in 2019, she changed that rule, allowing only a party leader or a majority of a party to try to oust the speaker. McCarthy would have liked to have kept that kind of job security. But the Freedom Caucus forced his hand, and McCarthy restored the old rule, which empowers any single member to force such a vote, and call his job into question.

To save face, McCarthy’s allies have been saying that this concession merely restores the rule to the way it was prior to Pelosi’s second four-year stint as speaker. That is true, but it misses some important context: This rule was a loaded gun sitting around for decades waiting for someone to pick it up. Then-Rep. Mark Meadows finally did in 2015, eventually leading to Speaker John Boehner’s retirement.

McCarthy will now take over a more radical and narrower majority than Boehner had; the gun has been reloaded; and there’s recent precedent for its having been used. For those who forced McCarthy into making all sorts of side agreements last week, this is their ultimate accountability mechanism to ensure he follows through.

A couple of the major side agreements McCarthy reportedly agreed to include giving hard-line Freedom Caucus members a critical three seats on the Rules Committee, and passing a 2024 budget capped at levels lower than 2022. Again, these aren’t in the rules package. They’re in a written gentlemen’s agreement somewhere, which Punchbowl News devilishly described as the “secret three-page addendum.”

We don’t know what else is in this mysterious codex. It’s secret! But the elements of the McCarthy deal with holdouts that would probably give most Republican swing-district members, defense hawks, and appropriators heartburn would be found in the Secret Three-Page Addendum. Already, there’s concern that one agreement—capping spending at 2022 levels—would necessarily lead to defense cuts. (Members who negotiated the deal, like Texas Rep. Chip Roy, argue that the caps can be met by going after non-defense discretionary spending alone. But there are plenty of Republicans who don’t want to cut domestic spending that much.)

That prompted Texas Rep. Tony Gonzales, for one, to declare himself a “no” on the rules package over the weekend. He was also worried about the restored motion to vacate the chair.

“I don’t want to see us every two months be in lockdown,” Gonzales told Fox News of the possibility of recurring speaker elections every time McCarthy angers, say, Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz. Gonzales was the only Republican to vote no.

South Carolina Rep. Nancy Mace had been undecided on the package heading into Monday, wanting more information on the “backroom deals” McCarthy cut with the holdouts. She was a “yes” in the end, but warned against backroom deals after she voted.

What may leaders have told these members who had concerns about the rules, or the Secret Three-Page Addendum? Perhaps to go along with all the tough talk about cuts for now, because they’ll ultimately be dead on arrival in the Senate, and then a real bipartisan deal will be cut.

Promising one side dramatic spending cuts and the other side that those cuts will never really happen: A guidebook for American legislative leadership.

And now, for a slew of other things in the rules package that caught our eye.

• It weakens the Office of Congressional Ethics.

• Proxy voting is gone.

• It establishes a Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic to look into, among other things, the “Federal Government’s funding of gain-of-function research.” (These are the dudes that will harangue Anthony Fauci.) It also tees up a vote to establish the Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government, which is expected to be Ohio Rep. Jim Jordan’s perch from which to go after the FBI.

• It requires the Congressional Budget Office to offer a so-called dynamic score of major legislation, i.e., to “incorporate the budgetary effects of changes in economic output, employment, capital stock, and other macroeconomic variables resulting from such legislation” into its score. They want CBO to make tax cuts look cheaper.

• It revokes House floor privileges from territorial governors and the mayor of Washington, D.C.

• It restores the Holman rule, which allows individual members to use the appropriations process to cut the salaries or staff positions of federal workers at specific agencies. In other words, they may just go after the jobs of individuals who are villains in the MAGA cinematic universe. (Another good moment to reiterate that all this legislation will slam into a wall called the Senate.)

• It attempts to enforce “single-subject bills.” Conservatives get angry at the way leaders logroll disparate pieces of legislation in order to sneak its more controversial components across the finish line. The requirement itself, though, reads as somewhat porous, requiring bill sponsors to merely submit for the record “a statement setting forth the single subject of the bill or joint resolution.” Just say it’s about “politics stuff,” like I tell my editor.

• It bars former members (or their spouses) who are lobbyists from using the House gym, a steamy haunt for corruption.

With their rules and a pathway to restoring American fiscal sanity in place, Republicans immediately turned to pass their first big policy item of the new Congress: defunding Democrats’ recent expansion of IRS enforcement. Republicans’ bill would add $114 billion to the debt.

READ MORE  Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors has described her family's shock after watching the LAPD take down her cousin in the middle of the street. (photo: Los Angeles Police Department)

Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors has described her family's shock after watching the LAPD take down her cousin in the middle of the street. (photo: Los Angeles Police Department)

ALSO SEE: LA Police Chief Admits He Is 'Deeply Concerned'

Over Two Recent Fatal Police Shootings

When he died, Anderson—who at least one bystander claimed had tried to steal a car—became the third man of color to perish after a violent encounter with the LAPD in the span of a week. The department’s own chief took the unusual step of quickly suggesting at least one of the fatalities could have been avoided.

When the family watched the video prior to its public release, some viewed it in the police station itself. Others watched at home and over Facetime, Cullors told The Daily Beast.

She described her family’s initial reaction as “devastated” and “disgusted.”

“From his brother Chris just being like ‘How did they do that to him?,’ ‘How did this end up leading to his death,?’ to his sister saying ‘That was too much’ … to his auntie —my cousin— just crying uncontrollably,” Cullors told The Daily Beast.

“Like, It's so traumatic, I can’t unsee that,” she said. “No one deserves to die begging for their life.”

Body-camera footage shows Anderson, 31, repeatedly yell, “They’re trying to George Floyd me!” as cops restrained him in the middle of the street on Jan. 3. One officer held his elbow on Anderson’s neck as he was pinned to the ground. Simultaneously, after police issued a slew of warnings, another officer appeared to tase Anderson for nearly 30 seconds straight.

The disturbing incident unfolded after a car crash in Venice, police said.

Police footage shows cops placing Anderson in handcuffs. A news release from the LAPD says he was then taken into custody and transferred by ambulance to a hospital in Santa Monica, where he was pronounced dead from cardiac arrest about four hours after the use of force.

Anderson was a 10th-grade English teacher at a majority-Black public charter school in Washington, and was in Los Angeles visiting family and friends, the Washington Post reported, citing Cullors.

“He really saw himself as a mentor to young people,” Cullors told The Beast. “He really saw himself as someone to help young people — especially young Black people.”

Los Angeles Police Chief Michel Moore said Wednesday that “it’s unclear” what role Anderson’s struggle with police played in his death. He said Anderson was in an “altered mental state” and claimed that a preliminary blood test showed he had cannabis and cocaine in his system.

Dr. Melina Abdullah, co-founder of Black Lives Matter Los Angeles, said Wednesday that she believes Anderson’s death was the result of police violence, full stop.

“Keenan’s murder is absolutely horrific,” Abdullah said, as the Guardian reported. “LAPD is not calling it a ‘killing,’ but calling it an ‘in-custody death.’ But Keenan was tased to death. We know LAPD caused Keenan’s death.”

The Los Angeles County Medical Examiner’s Office website indicated Anderson’s cause of death was still under investigation.

Anderson was at least the third person to die after an encounter with police in Los Angeles less than a week into 2023. The others, 45-year-old Takar Smith and 35-year-old Oscar Sanchez, were gunned down by officers.

Cops said Sanchez was killed after police, equipped with shields, responded to an area in South L.A. after receiving 911 calls that a man—later identified as Sanchez—was throwing a knife and metal objects at cars as they drove by on Jan. 3.

Once officers arrived at the scene, they said Sanchez was armed with a “makeshift spear” and metal chain on the second floor of an abandoned residence. Once cops yelled for him to come down, he can be heard on body-cam footage yelling back in Spanish, “You’re not going to rob me, idiot.”

Officers then entered the residence, but it was unclear what, exactly, happened next, as a shield blocked at least one body camera. An officer is heard yelling “put that down” shortly before six gunshots rang out.

Footage shows Sanchez being placed in handcuffs and carried to the base of the stairway, where paramedics rendered aid. Cops said he died later that day in the hospital, and that a utility knife was recovered at the scene.

Smith was killed the day prior, on Jan. 2, after cops responded to a home where his wife called a non-emergency number saying he was “acting crazy,” was off his medication for schizophrenia, was violating a restraining order, and “likely” had a knife, cops said.

Chief Moore expressed doubt about his patrol officers’ decision to proceed in engaging Smith instead of calling the department's Mental Evaluation Unit. That unit pairs officers with county social workers trained in de-escalating standoffs, a sort of police-reform benchmark in the BLM era.

The chief said at a news conference he had “concern” over “the actions of our officers and supervisors not acting on information regarding this individual’s prior mental health issues or current mental health issues.”

Once at the scene, body-camera footage showed officers and Smith arguing for several minutes at the front door to the apartment, with cops insisting he step outside and Smith refusing, despite threats he’d be tased.

The argument escalated once Smith retreated to the apartment kitchen, where body-cam footage shows he grabbed a butcher knife. Smith then puts the knife down and creates a barricade between himself and the officers, after which they tased him, but Smith then picked up the knife again and raised it above his head.

This action appeared to prompt cops to open fire on Smith, killing him.

Chief Moore said Wednesday that he was releasing body-cam footage for each encounter now—as opposed to waiting 45 days, which department policy allows—because of “substantial public interest” in a series of tragedies that “deeply concerned” him.

Anderson taught at Digital Pioneers Academy in southeast Washington, D.C. for roughly six months and was “beloved by all,” the school CEO and founder, Mashea Ashton, said in a statement Wednesday.

Ashton said Anderson was the third member of the school community to be killed in the last 65 days. “We are committed to supporting his family and working together to honor Keenan’s memory,” Ashton wrote.

Los Angeles cops say the incident preceding Anderson’s death began around 3:38 p.m. on Jan. 3, when officers were flagged down after a traffic crash at the intersection of Venice Boulevard and Lincoln Boulevard.

In a statement, cops said a motorcycle officer spotted Anderson “running in the street” and “exhibiting erratic behavior,” and that he pursued after other drivers suggested that Anderson may have caused the crash.

The officer eventually reached Anderson and they began to talk, with Anderson repeatedly suggesting someone was trying to kill him.

Anderson then became visibly agitated with the officer and was claiming that someone was putting stuff into his car. Shortly after, Anderson tried to run away, which sparked the struggle between Anderson and cops that was captured by body cameras in the middle of the street.

Cullors said she grew up going to barbecues and playing baseball in the park with other family members and Anderson.

“ I remember him as a kid — just big eyes and big smiles,” she told The Daily Beast. “Based off of the video … you can see that he was just kind, you know? I think the most painful thing about watching the video was hearing him ask for help.”

Body-camera footage of the incident ends with a subdued Anderson being placed in the back of an ambulance. A Los Angeles police spokesperson told The Daily Beast on Thursday it would not immediately release the names of cops involved in the arrest of Anderson.

As an adult, she said her cousin, was a “really powerful educator, a loving sibling, a father, mentor, and that “he loved his child.”

Cullors said that despite her years of organizing for BLM, she had never had a family member die in police custody. It was a sober reminder, she said, that “in this fight as Black people, we’re not separate from the Black people we are fighting for.”

And despite the BLM movement, and a national reckoning on race and policing following the death of George Floyd, in 2022 the number of people who died at the hands of police rose compared to the previous year, according to the Mapping Police Violence project.

“He was stolen from us,” Cullors told The Daily Beast.

“What will it take? How many killings? How much trauma do Black people need to endure in order for us to transform this place?” she later added.

READ MORE  Netanyahu's extreme-right coalition threatens Israel's democracy. (photo: AFP)

Netanyahu's extreme-right coalition threatens Israel's democracy. (photo: AFP)

Decency and reason can still prevail, but more than ever Israel needs its Jewish friends abroad.

The summer of 1982 was one of the lowest points in Israeli history. All of the ambivalence over Israel that would divide the Jewish people in the coming decades began to coalesce then, when Israel was fighting a war in Lebanon that large parts of the Israeli public regarded as unnecessary and deceitful.

I had joined an Israel that was, for the first time, bitterly divided over the perception of threat. War had always united Israelis; now war was dividing them. Once inconceivable, huge anti-government demonstrations took place even as the Israel Defense Forces were fighting at the front. Reservists completing their month of service would return their equipment and head directly to the daily protests outside the prime minister’s residence in Jerusalem. If an external threat could no longer unite us, what would hold this fractious people together?

These days, as Israel faces another historic internal crisis, I find myself thinking a great deal about the summer of ’82. Then we lost our unity in the face of an external threat. Now we’ve lost our unifying identity as a Jewish and democratic state.

The new governing coalition of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is a mortal danger to our internal cohesion and democratic legitimacy—a historic disgrace. Each day seems to bring some new, previously unimaginable violation of a moral and national red line. My ordinarily insatiable appetite for Israeli news has been reduced to skimming the headlines; the details are too painful.

READ MORE  Climate activists protest on the first day of the ExxonMobil trial outside the New York State Supreme Court building on Oct. 22, 2019, in New York City. (photo: Angela Weiss/Getty)

Climate activists protest on the first day of the ExxonMobil trial outside the New York State Supreme Court building on Oct. 22, 2019, in New York City. (photo: Angela Weiss/Getty)

Oil company drove some of the leading science of the era only to publicly dismiss global heating

A trove of internal documents and research papers has previously established that Exxon knew of the dangers of global heating from at least the 1970s, with other oil industry bodies knowing of the risk even earlier, from around the 1950s. They forcefully and successfully mobilized against the science to stymie any action to reduce fossil fuel use.

A new study, however, has made clear that Exxon’s scientists were uncannily accurate in their projections from the 1970s onwards, predicting an upward curve of global temperatures and carbon dioxide emissions that is close to matching what actually occurred as the world heated up at a pace not seen in millions of years.

Exxon scientists predicted there would be global heating of about 0.2C a decade due to the emissions of planet-heating gases from the burning of oil, coal and other fossil fuels. The new analysis, published in Science, finds that Exxon’s science was highly adept and the “projections were also consistent with, and at least as skillful as, those of independent academic and government models”.

Geoffrey Supran, whose previous research of historical industry documents helped shed light on what Exxon and other oil firms knew, said it was “breathtaking” to see Exxon’s projections line up so closely with what subsequently happened.

“This really does sum up what Exxon knew, years before many of us were born,” said Supran, who led the analysis conducted by researchers from Harvard University and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “We now have the smoking gun showing that they accurately predicted warming years before they started attacking the science. These graphs confirm the complicity of what Exxon knew and how they misled.”

The research analyzed more than 100 internal documents and peer-reviewed scientific publications either produced in-house by Exxon scientists and managers, or co-authored by Exxon scientists in independent publications between 1977 and 2014.

The analysis found that Exxon correctly rejected the idea the world was headed for an imminent ice age, which was a possibility mooted in the 1970s, instead predicting that the planet was facing a “carbon dioxide induced ‘super-interglacial’”. Company scientists also found that global heating was human-influenced and would be detected around the year 2000, and they predicted the “carbon budget” for holding the warming below 2C above pre-industrial times.

Armed with this knowledge, Exxon embarked upon a lengthy campaign to downplay or discredit what its own scientists had confirmed. As recently as 2013, Rex Tillerson, then chief executive of the oil company, said that the climate models were “not competent” and that “there are uncertainties” over the impact of burning fossil fuels.

“What they did was essentially remain silent while doing this work and only when it became strategically necessary to manage the existential threat to their business did they stand up and speak out against the science,” said Supran.

“They could have endorsed their science rather than deny it. It would have been a much harder case to deny it if the king of big oil was actually backing the science rather than attacking it.”

Climate scientists said the new study highlighted an important chapter in the struggle to address the climate crisis. “It is very unfortunate that the company not only did not heed the implied risks from this information, but rather chose to endorse non-scientific ideas instead to delay action, likely in an effort to make more money,” said Natalie Mahowald, a climate scientist at Cornell University.

Mahowald said the delays in action aided by Exxon had “profound implications” because earlier investments in wind and solar could have averted current and future climate disasters. “If we include impacts from air pollution and climate change, their actions likely impacted thousands to millions of people adversely,” she added.

Drew Shindell, a climate scientist at Duke University, said the new study was a “detailed, robust analysis” and that Exxon’s misleading public comments about the climate crisis were “especially brazen” given their scientists’ involvement in work with outside researchers in assessing global heating. Shindell said it was hard to conclude that Exxon’s scientists were any better at this than outside scientists, however.

The new work provided “further amplification” of Exxon’s misinformation, said Robert Brulle, an environment policy expert at Brown University who has researched climate disinformation spread by the fossil fuel industry.

“I’m sure that the ongoing efforts to hold Exxon accountable will take note of this study,” Brulle said, a reference to the various lawsuits aimed at getting oil companies to pay for climate damages.

A spokesperson for Exxon said: “This issue has come up several times in recent years and, in each case, our answer is the same: those who talk about how “Exxon Knew” are wrong in their conclusions. In 2019, Judge Barry Ostrager of the NY State Supreme Court listened to all the facts in a related case before him and wrote: “What the evidence at trial revealed is that ExxonMobil executives and employees were uniformly committed to rigorously discharging their duties in the most comprehensive and meticulous manner possible….The testimony of these witnesses demonstrated that ExxonMobil has a culture of disciplined analysis, planning, accounting, and reporting.”

READ MORE  The Jefferson Parish Sheriff's Office in Louisiana has been unlawfully destroying its deputies' disciplinary records for at least 10 years. (photo: AP)

The Jefferson Parish Sheriff's Office in Louisiana has been unlawfully destroying its deputies' disciplinary records for at least 10 years. (photo: AP)

A Sheriff in Louisiana Has Been Destroying Records of Deputies' Alleged Misconduct for Years

Richard A. Webster, ProPublica

A lawsuit brought by the family of an autistic teen who died while in custody found the Jefferson Parish Sheriff's Office destroyed the disciplinary records of a deputy involved in the case.

The finding comes at a time when the sheriff’s office is facing multiple lawsuits involving allegations of excessive force, racial discrimination and wrongful death at the hands of Jefferson Parish deputies. Attorneys have accused Sheriff Joe Lopinto of failing to discipline deputies and a lack of transparency when it comes to releasing records that might shed light on their history of complaints and disciplinary action.

The illegal destruction of disciplinary records can make it harder to hold deputies accountable in a court of law or track problem officers moving from department to department, said Sam Walker, emeritus professor of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska at Omaha.

The sheriff’s office was recently the subject of a year-long investigation by ProPublica and WWNO/WRKF, which found that JPSO rarely sustains complaints against its deputies. The sheriff’s office refused to provide the news organizations with copies of unsustained complaints, calling it overly burdensome and an invasion of privacy. The agency said it couldn’t even provide the number of complaints filed, stating such a number “does not exist.”

Like all public agencies, the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office is required by law to secure approval from the Louisiana State Archives, a division of the Secretary of State’s Office, before destroying its public records. It also is required to secure approval for policies, or schedules, dictating how long public records are to be retained before they are eligible for disposal.

The sheriff’s office failed to do either, records show. The only JPSO records retention policy on file with the state concerns body-worn and vehicle-mounted cameras. That was approved in November. The sheriff has not sought approval for retention policies concerning any other public record, including disciplinary files, according to the state archives.

As for securing permission to destroy public records, state archivist Catherine Newsome said, “We do not have any disposal requests on file for JPSO.” The state archives maintains records of disposal requests for 10 years.

Newsome said the archives conduct “ongoing outreach” with agencies throughout the state regarding records retention policies, but there is little more they can do.

“We’re not a law enforcement or compliance agency. We don’t have any stick,” Newsome said. “There’s nothing in any of the statutes that say, ‘If an agency doesn’t do this within 30 days, the secretary can fine them $500 or penalize them.’ It is incumbent upon the agencies themselves to comply with these statutes.”

There are more than 4,000 state, parish and local agencies that must comply with state retention records law. The state archives have only four data analysts and a supervisor to handle the workload, making it extremely difficult for them to ensure every agency is following the law, Newsome said.

Destroying, damaging, altering or removing public records “required to be preserved in any public office or by any person or public officer” is punishable by up to a year in prison, a fine of up to $1,000 or both.

JPSO attorney Danny Martiny said the agency could not comment because of pending litigation. The sheriff’s office has denied all wrongdoing in court filings.

“Because They Are Expunged”

The records retention issue was recently raised as part of a federal civil rights lawsuit filed against Lopinto and seven deputies, among others, by the family of 16-year-old Eric Parsa in New Orleans federal court. The teenager died in January 2020 after sheriff’s deputies attempted to restrain him outside the Westgate Mall in Metairie. Parsa had a violent meltdown caused by his severe autism, according to the lawsuit. The suit asserted that one of the deputies, who weighed more than 300 pounds, sat on him for at least nine minutes.

The coroner ruled the teen’s death an accident as a result of excited delirium, with “prone positioning” as a contributing factor.

When attorneys for the family deposed Deputy Nick Vega, one of two deputies accused in the lawsuit of sitting on Parsa prior to his death, they asked him about his disciplinary history. Vega referred to several complaints that had not been revealed to the family’s attorneys during discovery, as required by law.

JPSO’s standard operating policy states that disciplinary records will be maintained for three years. After that period has expired, they will be “automatically expunged on a monthly basis from the date of complaint” for internal affairs cases and “citizen complaints and the date of occurrence” for disciplinary reports. The records will not be deleted if litigation has been filed against an employee, or if a court orders certain records to be preserved, according to the policy.

Though the sheriff’s office has an internal policy, the law requires it to submit that policy to the state for approval, which it has not done. And as the plaintiffs later noted in a court filing, automatic expungement — without first seeking state approval — is also against the law.

In October, Andrew Clarke and William Most, attorneys representing the Parsa family, filed a motion seeking court sanctions against the sheriff’s office for the destruction of disciplinary records. Beyond the apparent state law violations, they claim the sheriff’s office also violated a 2020 state court order the family secured mandating that it maintain all records relevant to the case.

“But despite all this, JPSO did not stop the destruction of officer disciplinary records. It was not until nearly a year later — after the January 2021 filing of this lawsuit — that JPSO began preserving disciplinary records,” the attorneys wrote.

The lawsuit claims the sheriff’s negligence in handling public records speaks to a more systemic problem of failing to “properly supervise, discipline or otherwise hold accountable deputies who failed to comply with the law.”

“Their disciplinary history may show a history of excessive restraint or force, or episodes casting doubt on credibility,” the attorneys wrote. “That history is now unavailable because JPSO destroyed it.”

In a response filed with the court, JPSO claimed it was not ordered or obligated to stop destroying disciplinary records prior to the lawsuit being filed in January 2021. Further, the agency said “to ensure that any relevant deputy was not subject to” Internal Affairs complaints, “the Sheriff had an officer review attendance records to confirm that none was absent due to suspension, which he argues proves no significant disciplinary action near or after the incident.”

The sheriff’s office accused the family of filing the motion for “harassment purposes.”

U.S. Magistrate Judge Donna Phillips Currault in a November ruling found that JPSO should have known that “evidence regarding the disciplinary and training histories of the officers involved in the incident” leading to Parsa’s death “would be relevant to potential future litigation” and had the “duty to preserve that evidence” by March 2020 at the latest. However, the family failed to prove JPSO destroyed evidence in “bad faith” or with a “desire to suppress the truth.” They also failed to prove that evidence relevant to the case had been lost, she stated in denying the request for sanctions.

Ashonta Wyatt, a leader in Jefferson Parish’s Black community who has pushed for reforms of the sheriff’s office, said the real problem with the agency is that it operates free of oversight.

“Who governs them? Who holds them to account?” Wyatt said of the sheriff’s office. “It’s not like you can go to a mayor, like you can in New Orleans, where the mayor is the governing person for the chief of police. There’s no governing body for them. They operate on an island.”

Other Large Agencies Keep Records for Far Longer

The New Orleans Police Department’s disciplinary records are “effectively retained forever,” according to NOPD’s Public Affairs Division.

“Our state-approved record retention states ‘active + 10 years,’ defining ‘active’ to be as long as the department exists, meaning these records should be kept until 10 years after NOPD no longer exists,” the division stated in an emailed response. NOPD secured approval from the state for its policy, along with the destruction of any documents.

The Louisiana State Police doesn’t dispose of disciplinary records until one year after the end of someone’s employment, according to a September report by the Louisiana Legislative Auditor entitled “Louisiana State Police: Comparison with Law Enforcement Agencies in Southern States.” The Texas Highway Patrol keeps them for five years after the end of a person’s employment, the Alabama Highway Patrol for six years and the South Carolina Highway Patrol for 15.

Emily Dixon, a coauthor of the auditor’s report, said securing state approval for the preservation and disposal of disciplinary records is vital to public safety given deputies or officers might move from parish to parish.

READ MORE  A 'water and life' anti-mining protest camp in Guapinol in late 2018. (photo: Guapinol Community)

A 'water and life' anti-mining protest camp in Guapinol in late 2018. (photo: Guapinol Community)

Two environmental activists were killed on Saturday after they opposed an open-pit iron oxide mine in a reserve.

On Saturday, Aly Dominguez, 38, and Jairo Bonilla, 28, from the village of Guapinol in Honduras’s eastern Colon Department were killed by unidentified men. Local police attributed the deaths to a robbery.

“It’s vital that an independent investigation is carried out into the killing of the two defenders in Guapinol, Honduras,” Lawlor said on Twitter on Wednesday.

“Which must take into account the possibility that they have been retaliated against for their work defending human rights,” she added.

Dominguez and Bonilla had co-founded the Municipal Committee for the Defense of Common and Public Goods for the city of Tocoa, some 8km (5 miles) from Guapinol.

According to the environmentalist group, they had since 2015 put up a strong resistance to the operation of an open-pit iron oxide mine in a forest reserve, a concession they say was illegally granted to a company of influential businessman Lenir Perez.

Inversiones Los Pinares, the company operating the mine, argues the concession is legal. It did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Authorities said Dominguez and Bonilla were on motorcycles working their day jobs collecting service payments for a regional cable television company when they were attacked in a secluded area.

Colon police spokesperson Angel Herrera told local media the crime was motivated by an attempt to rob the money they were carrying.

But Guapinol Resiste, the environmentalist group Dominguez and Bonilla belonged to, rejected this claim on Wednesday.

“It was not a robbery. They were killed for defending the rivers from illegal mining. Justice for Aly and Jairo,” the group said on its Facebook group. It also pointed out that the criminals did not take the money, which was instead later handed over to their employer.

Many environmentalists and local communities in Central American countries oppose open-pit mining and the building of hydroelectric dams, which can pollute rivers, contaminate water supplies and displace populations.

In March 2016, Indigenous leader and environmentalist Berta Caceres, who was fighting the construction of a hydroelectric dam in western Honduras, was murdered. Six hired assassins and two executives of a firm promoting the dam’s construction were later convicted.

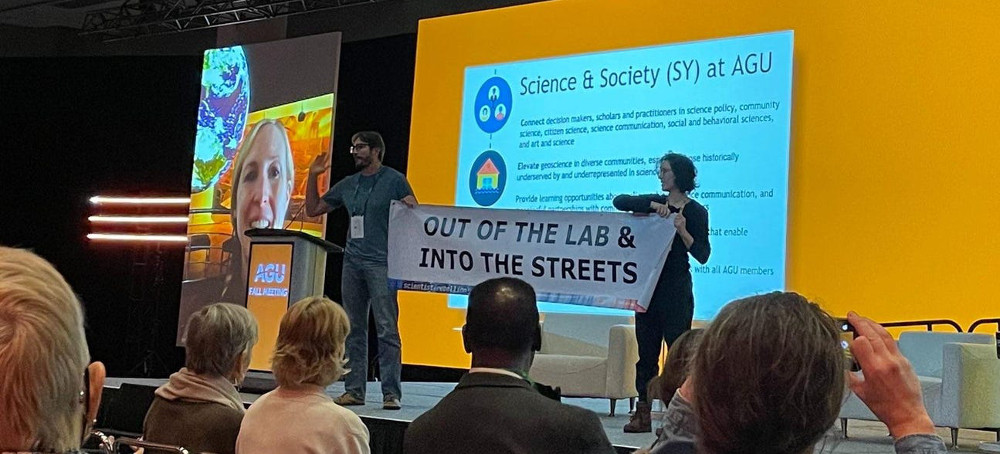

READ MORE  Peter Kalmus (left) and Rose Abramoff (right) unfurled a banner onstage during a lunchtime plenary at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union. (photo: Rose Abramoff)

Peter Kalmus (left) and Rose Abramoff (right) unfurled a banner onstage during a lunchtime plenary at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union. (photo: Rose Abramoff)

Soon after this brief action, the A.G.U., an organization with 60,000 members in the earth and space sciences, expelled us from the conference and withdrew the research that we presented that week from the program. Eventually it began a professional misconduct inquiry. (It’s ongoing.)

Then, on Jan. 3, Oak Ridge, the laboratory outside Knoxville where I had worked as an associate scientist for one year, terminated my employment. I am the first earth scientist I know of to be fired for climate activism. I fear I will not be the last.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.