Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Biden wrapped up 2022 with positive momentum. He had achieved an impressive slate of historic legislation through the soon-to-end 117th Congress despite the thinnest possible majority in the Senate (including the recalcitrant Manchin and Sinema) and not much more breathing room in the House. He had led a strong response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine by repairing alliances frayed by the former guy in the White House. And he had seen his fellow Democrats outperform historical trends in the midterm election.

To be sure, as Biden and his team entered 2023, they could see some rocky shoals looming ahead. Inflation, while starting to trend in a downward direction, remained a concern, along with fears about a possible recession. The situation at the U.S.-Mexico border continued to defy easy solutions. And while Biden’s approval ratings had improved from their nadir, they still were well below water.

Furthermore, control of the House of Representatives was changing hands. Instead of a productive partner in Nancy Pelosi, the White House (and the rest of us) would be bombarded by “message bills” that have no chance of becoming law, along with investigations into the likes of Hunter Biden and Anthony Fauci.

Now, into this mix, arrives a new challenge to the Biden presidency — and a vivid reminder that the presidency entails being buffeted by surprises and events beyond your control. As we go to our news sources today, the leading story is again one that was nowhere on the horizon even a few days ago. After the saga of classified documents being taken to and hidden at Mar-a-Lago by the previous president, it turns out that Biden has also had classified documents in his possession at his home and office. And they were there for a while.

These revelations raise questions that demand answers. How did this happen? Who was responsible? Was any sensitive information put in jeopardy? Now that Attorney General Merrick Garland has appointed a special counsel to investigate, the job of acquiring those answers falls to Robert Hur, a former federal prosecutor with a deeply conservative pedigree who was also a Trump appointee.

Make no mistake, as much as you may want to believe otherwise, this is a serious matter. Misuse of highly classified national security materials is a crime under most circumstances — as it should be. People accused of it are pursued internationally. People convicted of it often serve heavy jail time.

Remind yourself of that, then recall the important American legal principle that no person is above the law and you have the reality of what serious trouble President Biden could be in over this matter.

Many legal observers predict that Hur will end up finding nothing of concern. But given the number of unknowns still lurking, this story could develop in unexpected ways. Also, special counsels sometimes start digging for the sake of digging. And investigations started for one reason morph into new and unexpected directions. We will now see where this goes. What if Hur decides to seek indictments? What then?

It was completely predictable that Republicans would latch onto these revelations to cry foul about double standards and to attack President Biden. Trump and others close to him are facing multiple investigations. Any way to muddy the waters and try to convince the public that even if they don’t like what Trump did, Biden did it too, is in the Republicans' interest.

The facts, as we know them now, however, suggest the two cases have important differences. Whereas Trump hid the documents he appears to have knowingly taken, Biden’s team seems to have been the ones to find the documents and report them to the National Archives, who in turn immediately notified the Department of Justice. When a second set of documents was found, it appears Biden’s team contacted the DOJ directly. But the timeline and nature of the communication, at least in the public record, remains murky.

Nevertheless, on the one side (Trump) we seem to have deliberate action. On the other side, we may, may, have a mistake. But we must be careful not to come to concrete conclusions at this point. New revelations could shift these understandings. All of us should hope that the investigations into both Trump and Biden seek out the unbiased truth.

Meanwhile, as Republicans howl about the scandal du jour, it’s important to note a few more points of context. To attack Biden on classified documents is to admit that there was something very wrong with what Trump did as well. And furthermore, when it comes to the legal jeopardy in which Trump finds himself, one can make the case that the documents investigation, as serious as it is, pales in gravity next to charges that the former president tried to orchestrate a coup to overthrow America’s constitutional order.

One also wonders how all of this is playing out in the country at large, especially if the facts remain as we currently know them. Will this hurt Biden politically with the general electorate? Will it have staying power beyond a few more news cycles in outlets that aren’t Fox News?

Biden’s approval ratings continue to improve, as do the numbers around inflation. The dysfunction of the Republican-controlled House has already been on display, along with the desperation of its new speaker. If the message from voters in the last midterms was “eschew extremism for positive action,” it seems to have been lost on the likes of Kevin McCarthy.

Buckle up — 2023 is likely to be a wild and bumpy ride.

READ MORE  The towers of Brazil's congressional building are seen from the damaged Supreme Court building in Brasília's Plaza of Three Powers after the assault of Jan. 8. (photo: Rafael Vilela/WP)

The towers of Brazil's congressional building are seen from the damaged Supreme Court building in Brasília's Plaza of Three Powers after the assault of Jan. 8. (photo: Rafael Vilela/WP)

ALSO SEE: 'We Will Die for Brazil': How a Far-Right Mob Tried to Oust Lula

The bolsonaristas had camped on the sprawling green space since the right-wing leader’s October election loss to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. They, like Bolsonaro himself, refused to recognize Lula’s victory, even after the leftist was sworn in Jan. 1. For weeks, they had called on the military to stage a coup to keep Bolsonaro in power.

It was an idea that observers in and out of Brazil saw as far-fetched. But when top Lula administration officials arrived at the army headquarters Sunday night with the aim of securing the detention of insurrectionists at the camp, they were confronted with tanks and three lines of military personnel.

“You are not going to arrest people here,” Brazil’s senior army commander, Gen. Júlio César de Arruda, told new Justice Minister Flávio Dino, according to two officials who were present.

That act of protection, which Lula administration officials say gave hundreds of insurrectionists time to escape arrest, is one of several indications of a troubling pattern that authorities are now investigating as evidence of alleged collusion between military and police officials and the thousands of rioters who invaded the institutions at the heart of Brazil’s young democracy.

Those indications also include a change in the security plan before the insurrectionists gathered outside the federal buildings on Sunday, police inaction and fraternization as they began entering the buildings, and the presence of a senior officer of the military police who had told superiors he was on vacation.

This article, based on interviews with more than 20 senior Lula administration and judicial officials, protest organizers, participants, data miners and others, includes previously unreported details of the five-hour attack that shook Latin America’s largest country, with echoes of the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol.

Brazil’s military command did not respond to a request for comment.

Authorities are also working to identify the authors of messages on social media calling for the Sunday demonstration and the donors who funded buses to carry participants to the capital.

Before Sunday, the military had twice blocked authorities from clearing the bolsonarista camp, according to statements by Col. Fábio Augusto Vieira, the former commander of the military police of the Federal District of Brasília, that were provided to The Washington Post. Vieira has been detained in connection with security lapses during the riots.

The insurrectionists tore through the modernist government buildings of Brasília’s Plaza of the Three Powers, smashing glass, destroying furniture, slashing paintings and stealing weapons, documents and other trophies. Their plan, administration officials believe, was to trigger a law that would have allowed the military to restore order in the capital.

The investigation has also engulfed a key figure from Bolsonaro’s administration: Anderson Torres, Brasília’s security chief at the time of the insurrection and Bolsonaro’s justice minister. After the riot, authorities found a draft decree in Torres’s home declaring a “state of defense” to override Brazil’s electoral court and overturn Lula’s election victory. Investigators say they believe it was written between Dec. 13 and 31, when Bolsonaro was still president.

Torres, who was in Florida during the insurrection, has not challenged the authenticity of the document but said it was meant for the trash bin. He has denied any connection to the riots. Torres returned to Brazil on Saturday morning and was promptly arrested.

Bolsonaro spent years sowing doubt in Brazil’s electoral system, calling Lula a thief and stoking his supporters’ belief that if his opponent won, it could only be through fraud. Lula’s victory was affirmed by Brazil’s electoral court, the United States and other governments around the world. Bolsonaro authorized his chief of staff to lead a transition but never conceded.

On Dec. 30, in his most extensive public remarks since his loss, Bolsonaro called the result unfair. Then he decamped to Orlando, skipping Lula’s inauguration and its ceremonial passing of the presidential sash, a symbolic affirmation of democracy.

Still in Kissimmee, Fla., when his supporters began rioting, he was publicly silent for several hours. He condemned the violence, while also noting past violence by Brazil’s left.

Brazil’s Supreme Court on Friday agreed to a petition by prosecutors to investigate Bolsonaro as part of its probe into the “instigators and intellectual authors” behind the riot.

“There were a lot of conniving agents,” Lula told reporters last week. “There were a lot of people conniving from the military police. A lot of people conniving from the Armed Forces. I am convinced that the door of the [presidential palace] was opened for these people to enter because there is no broken door. That is, someone facilitated their entry here.”

On the night of the riot, Lula administration officials say, the president’s chief of staff, his justice and defense ministers, and the new security chief for the capital named to replace Torres arrived at the Space Age-style army headquarters at about 10:20 p.m. to negotiate the detention of insurrectionists and others in the protest camp. Military commanders agreed to allow security officials under Lula’s control to raid the camp, but not until 6 a.m. Monday. Administration officials say they believe that gave the military time to warn relatives and friends there to leave.

The security forces are one target in a rapidly expanding probe of an assault that has once again highlighted the danger to Western democracies from far-right extremists fueled by misinformation.

Investigators, working around the clock, are tracing the origins of social media posts that called on “patriots” to assemble and bring Brasília to a halt, accounts of businesses linked to the buses that brought rioters to the capital and data contained on 1,300 cellular phones seized from alleged insurrectionists.

Authorities have said they are investigating financial links to Brazil’s agribusiness interests, whom Bolsonaro championed while in office and who they say helped pay for the buses. Investigators say they are operating under the premise that Brazil’s large agricultural exporters are unlikely suspects, and are instead focusing on smaller companies tied to the illegal deforestation that flourished under Bolsonaro’s permissive approach to the environment. They note that a man arrested on Christmas Eve in connection to a bombing attempt in the capital came from Pará state in the Amazon region — a part of the country where illegal agribusiness thrives.

“Those who were involved in the coup d’etat were especially those involved in agribusiness outside the law,” Dino, the justice minister, told The Post. “The ones who occupy indigenous lands, public land, smuggle pesticides, fertilizers. People who operate in illegal mining. That’s the segment that’s going to appear.”

Sen. Carlos Portinho, the former leader of Bolsonaro’s government in the Senate, condemned the violence but also placed some of the responsibility for the security lapses on the Lula administration.

“Now we know 48 hours before Sunday, they were warned this could happen, and 20 hours before Sunday, they dismounted all the security planning,” Portinho said. “This is national security. I think it was a general lack in the government of Brasília but certainly as well in the Ministry of Defense and Lula.”

Lula’s government has said it was aware of plans for a protest but said the security plan was downscaled without their knowledge by pro-Bolsonaro state officials.

Social media posts calling bolsonaristas to the capital mention the company and name of one Brazilian billionaire close to Bolsonaro repeatedly. But authorities say they do not yet have enough evidence to pursue that figure.

The details uncovered by the investigation relate mostly to what officials describe as the surface of the plot: a network of smaller businesses, including transportation and tourism companies based in Brazil’s south, a Bolsonaro stronghold.

Government lawyers have asked a federal court to block $1.3 million in assets belonging to 52 people and seven businesses. The businesses are allegedly part of a network of local sponsors and organizers that in some cases helped raise donations for the Sunday gathering.

One is a small rural agribusiness union in Castro in Paraná state. Its Facebook page, which is no longer available, includes a group photo with a Bolsonaro campaign poster and a letter last year expressing solidarity with protesters against an “excessively activist” Supreme Court, a frequent target of bolsonarista criticism.

The union said it defends democratic values and legal orders expressed in the Brazilian constitution. “We do not condone demonstrations that transcend the limits of the established order,” it said in a statement published Friday by the news outlet O Globo.

Other businesses on the list appear to be small tourism or transportation agencies whose buses were used by protesters. Two of them acknowledged renting out vehicles but said they did not know they would be used to transport people to the capital to participate in an insurrection. At least one has denied transporting protesters.

Word of the buses spread through WhatsApp groups as well as Telegram and YouTube channels.

The Brazilian technology firm Palver monitors more than 17,000 public WhatsApp groups and other social media used to organize the trips. Many of those who asked for donations, Palver President Felipe Bailez said, were relatively obscure — YouTubers with 50,000 or fewer followers, for example.

Bus organizers and protesters have described the event as the expression of a grass-roots movement in which many bolsonaristas paid for their own bus tickets or gathered small donations from friends and family. But thousands of WhatsApp messages tell a different story, Bailez said, with local organizers offering to cover bus rides, meals and other expenses free of charge.

“I think there were [more powerful] authorities and entrepreneurs and politicians and hardcore bolsonaristas involved in this,” Bailez said. “But I really believe there was a lot of organic engagement from small-business owners and people in various cities of Brazil. … I don’t think it was completely planned by one person or a group of people.”

Rodrigo Jorge Amaral, 44, owns a tourism company in Florianópolis, the capital of Santa Catarina state on Brazil’s southern coast. He had just traveled to Brasília to protest Lula’s inauguration when he started to receive messages about another trip. Some came from U.S. phone numbers, with California and Florida area codes.

“Are you going to Brasília?”

Members of his local pro-Bolsonaro WhatsApp groups, some of whom had come together for a trucker strike in 2018, knew he owned a bus. He started responding to the messages with a cut-and-pasted response.

“BRASÍLIA URGENT,” he wrote. A bus would be leaving the island city from a pier at 8 p.m. Jan. 6. He initially charged people 650 reals, or about $127, But organizers gathered enough donations, Amaral said, that they were able to cover the trip. He would not identify the donors, saying they were worried about being targeted by authorities.

Amaral said his group arrived in Brasília after protesters had already entered the buildings. He said he knew people wanted to go inside the buildings but not to damage them.

Many who traveled to Brasília have said they did not know about plans to storm the buildings. Still unclear is when and how the mob decided to invade the buildings — and whether anyone in particular gave the order.

Bailez, who has scoured WhatsApp messages from that day, said he hasn’t seen a direct instruction.

“I saw some guy saying, ‘I’m here in Brasília and we’re taking over the Congress,’ and some other guy saying, ‘We’re going to explode this building.’ Some other guy would say, ‘We need to destroy everything.’

“I think that they started getting excited, and it was like a snowball.”

But he did notice WhatsApp accounts using a bomb emoji as early as two days before Sunday’s riot. In one national WhatsApp group, there was also a step-by-step plan on what to do before entering government buildings. The manual told protesters never to start an invasion without a crowd and never to try to take “two powers at the same time.”

One man in the southeastern state of Espírito Santo said he was organizing a bus to travel to Brasília but was spooked by messages circulating in a Telegram group called “Taking power.”

On the day before the riot, he said, it became clear to him that some wanted to try to enter government buildings. He decided to cancel his bus, he said.

“After Bolsonaro announced he was going abroad, they sensed they needed to change the strategy,” the man said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss the sensitive matter.

“They needed to separate the men from the boys,” he said. “Only the men who could act upon it should come to Brasília.”

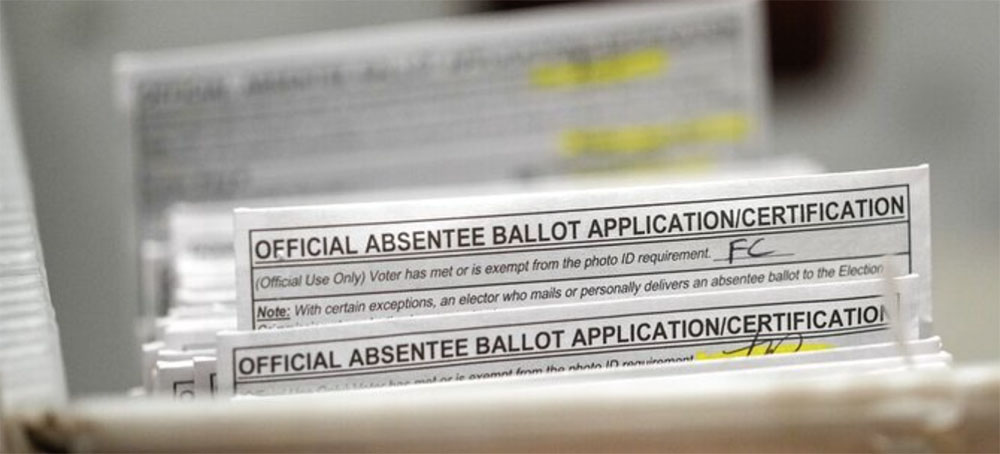

READ MORE  Absentee ballots are seen during a count at the Wisconsin Center for the midterm election on Nov. 8, 2022, in Milwaukee. (photo: Morry Gash/AP)

Absentee ballots are seen during a count at the Wisconsin Center for the midterm election on Nov. 8, 2022, in Milwaukee. (photo: Morry Gash/AP)

The pace of ballot counting after Election Day has become a target of conservatives egged on by former President Donald Trump. He has promoted a false narrative since losing the 2020 election that fluctuating results as late-arriving mail-in ballots are tallied is a sign of fraud.

Republican lawmakers said during debate on the Ohio legislation that even if Trump's claims aren't true, the skepticism they have caused among conservatives about the accuracy of election results justifies imposing new limits.

The new law reduces the number of days for county election boards to include mailed ballots in their tallies from 10 days after Election Day to four. Critics say that could lead more ballots from Ohio's military voters to miss the deadline and get tossed.

This issue isn't confined to Ohio.

Three other states narrowed their post-election windows for accepting mail ballots last session, according to data from the nonpartisan Voting Rights Lab. Similar moves pushed by Republican lawmakers are being proposed or discussed this year in Wisconsin, New Jersey, California and other states.

Ohio's tightened window for receiving mailed ballots is likely to affect just several hundred of the thousands of military and overseas ballots received in any election. Critics say any number is too great.

“What kind of society do we call ourselves if we are disenfranchising people from the rights that they are over there protecting?” said Willis Gordon, a Navy veteran and veterans affairs chair of the Ohio NAACP’s executive committee.

Republican state Sen. Theresa Gavarone, who championed the tightened ballot deadline, said Ohio's previous window was “an extreme outlier” nationally. She said Ohio's military and overseas voters still have ample time under the new law.

“While there is certainly more work to do, this new law drastically enhances Ohio’s election security and improves the integrity of our elections, which my constituents and citizens across the state have demanded," she said.

Republicans’ claims that Ohio needs to clamp down in the name of election integrity run counter to GOP officials' glowing assessments of the state's current system. Ohio reported a near-perfect tally of its 2020 presidential election results, for example, and fraud referrals represent a tiny fraction of the ballots cast.

Board of elections data shows that in the state’s most populous county, which includes the capital city of Columbus, 242 absentee ballots from military and overseas voters were received after Election Day last November. Of that, nearly 40% arrived more than four days later and would have been rejected had the new law been in effect.

In 2020, a federal survey administered by the U.S. Election Assistance Commission found that Ohio rejected just 1% of the 21,600 ballots cast by overseas and military voters with the 10-day time frame in place. That compared with 2.1% nationally, a figure attributed mostly to voters missing state ballot deadlines.

All states are required to transmit ballots to registered overseas and military voters at least 45 days before an election, or as soon as possible if the request comes in after that date.

Former state Rep. Connie Pillich, an Air Force veteran who leads the Ohio Democratic Party’s outreach to veterans and military families, rejects arguments that the relatively small number of affected ballots is worth the trade-off.

“These guys and gals stationed overseas, living in the sandbox or wherever they are, doing their jobs, putting themselves in harm’s way, you’re making it harder for them to participate,” said Pillich, who led an unsuccessful effort to have GOP Gov. Mike DeWine veto the bill.

“I can tell you everyone I've talked to is livid and upset,” she said.

Those familiar with submitting military ballots said applying for, receiving and filling out a mailed ballot requires extra time for those who are deployed. Postal schedules, sudden calls to duty, even extra time needed to consult family back home about the candidates and issues are factors. Ohio’s new law also sets a new deadline — five days earlier — for voters to request a mailed ballot, a move supporters say will help voters meet the tightened return deadline.

Neither the Ohio Association of Election Officials nor the state's elections chief, Republican Secretary of State Frank LaRose, asked lawmakers to shrink the existing 10-day window for receiving mailed ballots.

Aaron Ockerman, a lobbyist for the election officials' group, said the seven-day post-election window called for in an early version of the legislation was a compromise that county election directors decided they could live with.

“They felt the vast, vast majority of the ballots have arrived within eight days,” he said. The group opposed making the window any shorter, on grounds that voters — including those in the military — would be disenfranchised.

Research by the Voting Rights Lab shows Ohio joined three other states — Republican-controlled Arkansas and Iowa, and Nevada, where Democrats held full control at the time — in passing laws last year that shortened the post-election return window for mailed ballots. Five states lengthened theirs.

Nationwide, a little more than 911,000 military and overseas ballots were cast in 2020. Of those, about 19,000, or roughly 2%, were rejected — typically for being received after the deadline, according to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission.

The Secure Families Initiative, a national nonpartisan group advocating for military voters and their families, is trying to push state election laws in the other direction, toward broader electronic access to voting for service members and their families.

Kate Marsh Lord, the group's communications director, said they were “deeply disappointed” to see DeWine sign the Ohio bill.

“In fact, I’m an Ohio voter — born and raised in Columbus — and I’ve cast my Ohio ballot from as far away as Japan," she said. "HB458 set out to solve a problem that didn’t exist, and military voters will pay the price by having their ballots disqualified.”

Marsh Lord, currently in South Carolina where her husband is stationed in the Air Force, said mail sometimes took weeks to reach her family when they lived in Japan.

“Even if I were to get my ballot in the mail a week ahead of time, a lot of times with the military postal service and the Postal Service in general, there are delays,” she said. "So that shortened window doesn’t allow as much time for things that are really out of military voters’ control.”

She said it's even more challenging for active-duty personnel deployed to remote areas — “the people on the front lines of the fight to defend our democracy and our freedom and the right to vote around the world. Those are the people who will be most impacted by this change.”

READ MORE  Migrants arrive by bus from Texas to Philadelphia. (photo: Bastiaan Slabbers/Reuters)

Migrants arrive by bus from Texas to Philadelphia. (photo: Bastiaan Slabbers/Reuters)

A woman showed up to Texas with her 10-year-old daughter – only to be bussed to Philadelphia, a city she had never heard of

But when workers at the shelter near the US-Mexico border, where she and her daughter Danna, 10, were staying, showed the Colombian mother a map, she became worried. They were pointing to a city more than 80 miles (128km) away from Newark, New Jersey, where she hoped to join family members and wait for her immigration court hearing.

“They simply explained to me that there was a ride for free somewhere … and from there, we had to find our way,” Diana said, hugging Danna, who had been diagnosed as a newborn with retinopathy of prematurity, an eye disease that affects premature babies which has left her virtually blind.

They had few options so they boarded a bus provided by the authorities in Texas, where the right-wing Republican governor last year started transporting asylum seekers to northern, Democratic-led cities without coordinating with the destinations, dropping them off in New York, the street outside vice-president Kamala Harris’s residence in Washington and Chicago.

Diana, 37, asked fellow passengers if they knew where they were going and she was told Philadelphia, a place she had never heard of. As they journeyed across America in the chilly November weather, it was cold on the bus and Danna developed flu-like symptoms and couldn’t sleep. Food was in short supply and there was no medical attention available.

During the last stretch of a three-day ride, Danna’s health worsened and she was pale and sweating feverishly, her mother said, before they finally entered Philadelphia before dawn.

“When we arrived early in the morning, I got scared because I saw a big crowd through the window,” Diana told the Guardian.

In fact, the people at the city’s 30th Street station were there to welcome the 28 asylum seekers from the bus. When they realized Danna was sick, she was rushed to the hospital in an event that made national headlines and sparked a new burst of outrage from critics of Texas governor Greg Abbott.

In her first interview since the incident, Diana said that she’d alighted, then anxiously gotten back on the bus until one of the volunteers found her and reassured her.

“I didn’t want to alert anyone about my daughter’s fever because I was afraid we were going to be deported,” she told the Guardian in late December.

Blanca Pacheco, co-director of the New Sanctuary Movement, a grassroots immigration advocacy group in Philadelphia, had spotted Diana at the bus station. Born in Ecuador and now living in the US for more than two decades, Pacheco reassured the pair that they were safe.

“I remember Diana hugging her daughter… I told her she didn’t have to worry, that I would go with her in the ambulance. Later, I hugged her in silence and she broke down in tears,” Pacheco told the Guardian.

Danna was rushed to the emergency room of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and treated for acute dehydration and high fever.

A month later, Diana and Danna had been able to reach the relative sanctuary of her relatives’ home in Newark, where five of her Colombian relations live while they, too, go through the asylum application process. From there, she gave an exclusive interview to the Guardian.

All six adults were paying close attention to the TV news in Spanish.

“We always watch TV, hoping that we hear good news,” Diana said.

Danna bounced around on a queen-sized bed in the cramped apartment. She didn’t speak, but her mumbling-type noises signaled something to her older brother, who picked her up in his arms and rushed her off to use the bathroom.

On top of her neonatal sight problems, Danna was diagnosed with autism at the age of five. Autism spectrum disorder can have many genetic and environmental causes but the family had watched her symptoms really develop in 2014, after they became quite isolated when Diana witnessed the killing of a sister-in-law during a spate of violence in their home city of Bogotá.

Ever since, Diana said, the entire family lived in fear of becoming victims of violence, too, which is why she requested to withhold her and Danna’s last names and didn’t want to be photographed.

The family kept out of the murder investigation, afraid of possible retaliation, and withdrew significantly from their community, after which Danna increasingly experienced communication and behavioral difficulties, Diana explained.

Eventually, deepening danger in the community and Danna’s healthcare needs prompted Diana in late 2021 to plan to leave her daughter in Bogotá and head overland towards the US.

She knew that the eye disease alone would preclude Danna from being able to endure the hardships at the infamous Darién Gap, the mountainous jungle connecting Panama with South America, let alone cross the rest of Central America on foot. So Diana embarked on the perilous journey without her daughter and made it to Mexico City early last year with one goal in mind, buying an air ticket for Danna.

She got a job in Mexico City’s largest wholesale market, selling shoes until she had saved up enough for Danna to fly from Colombia and the two of them to reach Ciudad Acuña, which stands on the south side of the Rio Grande across the border from Del Rio, Texas.

“I had heard that the healthcare system here is good for kids like my daughter,” Diana said. She hoped an American specialist institution would be able to help her. “She needs a place where doctors can treat her right, help her with her communication skills and to advance in her education.”

In Ciudad Acuña, she paid a man to put Danna on his shoulders and carry her across the river that marks the line between Texas and Mexico. The Rio Grande can provide a benign crossing or, all too often, a death trap with hidden depths and currents, depending on the day or place.

Once safely in Del Rio, they claimed asylum – an exercise that is an international right but has been made increasingly difficult at the US border in recent years and became yet more restricted last week when Joe Biden announced new border rules that advocacy groups slammed as putting “more lives in grave danger”. Biden then made a brief and controversial first visit to the border as US president.

Meanwhile, the day after the debacle of Danna’s health emergency, Dominick Mireles, Philadelphia’s emergency management director, fired off a stern letter to Nim Kidd, the chief of the Texas division of emergency management, a copy of which has been seen by the Guardian.

Mireles wrote “to request that you uphold a core tenet of our profession: collaboration”.

It went on: “Your bus of asylum seekers that arrived yesterday took the city of Philadelphia and its partners by surprise. As you may have heard, a child required emergency medical care upon arrival.”

The letter had a list of measures expected by the Philadelphia authorities, including 72 hours notice prior to buses arriving, health screening, notification of passengers with disabilities or special needs, families being kept together and buses reporting to a “safe and secure location of choice, not a street corner”.

Pacheco said it was the New Sanctuary Movement that got a tip-off from a fellow organization in Texas that a bus carrying asylum seekers from Colombia, Cuba, Nicaragua, Panama, Ecuador and the Dominican Republic was en route to Philadelphia.

A city source familiar with the handling of asylum seekers told the Guardian last week that there had been no response to the letter and Texas officials have still not coordinated any plan with Philadelphia, despite sending more buses.

In Newark, Diana and her relatives watched more news reports as the TV anchor explained the latest border restrictions, and she pointed at images on the screen of migrants struggling to cope at the border, especially in El Paso around Christmas.

“We live under this expectation of being deported at any time,” she said.

But with immigration courts badly backlogged, in a system the US president admits is “deeply broken”, Diana’s asylum hearing is not until October 2025.

Before that, as soon as she is eligible to work, she plans to pay for treatment for Danna.

READ MORE  Students walk to classes on the Indiana University in Bloomington, Ind., in 2021. A student was stabbed on a bus near campus. (photo: Darron Cummings/AP)

Students walk to classes on the Indiana University in Bloomington, Ind., in 2021. A student was stabbed on a bus near campus. (photo: Darron Cummings/AP)

An 18-year-old Indiana University student was stabbed multiple times in the head while riding a local bus in Bloomington, Ind., this past week.

Indiana University in Bloomington confirmed that the victim was a student enrolled there and said it was an incident of "anti-Asian hate." Police did not provide details about the victim except that she was from Carmel, a city north of Indianapolis.

Bloomington is a college city southwest of Indianapolis. About 10% of the city's population identifies as Asian, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The Bloomington Police Department said the attack took place on Wednesday afternoon less than a mile from Indiana University's Bloomington campus.

The suspect, Billie R. Davis, 56, has been charged with attempted murder, aggravated battery and battery with a deadly weapon, according to court documents.

Local police said surveillance footage from the Bloomington Transit bus showed that the suspect and the victim had no interactions prior to the assault. The victim appeared to be getting off the bus when another passenger struck her repeatedly in the head with a knife, according to the affidavit. The attacker then left the bus and walked away.

When emergency responders arrived on scene, the victim was in immediate pain and bleeding, police said. She was quickly transported to an area hospital, where it was determined that the bleeding came from stab wounds on her head.

Police said they were able to identify and track down the suspect with the help of an unnamed witness who followed Davis out of the bus after the attack and alerted law enforcement of the suspect's location.

Although the investigation is ongoing, the unprovoked assault against a person of Asian descent follows increased reports of hate crimes against Asians beginning in 2020.

In a statement released on Saturday, Bloomington Mayor John Hamilton described the attack as a "racially motivated incident," adding that his staff is working to support the victim and the local Asian community.

"I want to state categorically that here in the city of Bloomington we deplore any form of racism and discrimination, especially hate based violence," he said.

Indiana University's vice president for diversity, equity and multicultural affairs, James Wimbush, said the attack "sadly reminded that anti-Asian hate is real and can have painful impacts on individuals and our community."

The university's Asian Culture Center also spoke out earlier.

"We should not be fearing for our lives on public transportation. Taking the bus should not feel dangerous," the group wrote in a statement.

The center said the attack sent "a familiar jolt" through Indiana's Asian community. In 2016, an 18-year-old student, Yue Zhang, was attacked with a hatchet by a man who wanted to bring about "an ethnic cleansing" in Nashville, Ind. In 1999, graduate student Won Joon Yoon was shot to death outside a church by a self-proclaimed white supremacist.

On Friday, the group also hosted a listening circle for students to come together in processing feelings of fear, sadness, anger and anxiety.

READ MORE Police fire teargas in Cusco on Wednesday. (photo: Ivan Flores/AFP/Getty Images)

Police fire teargas in Cusco on Wednesday. (photo: Ivan Flores/AFP/Getty Images)

ALSO SEE: Peru's Violent Unrest Shows No Signs of Stopping

Country reeling as police unleash deadly violence on Pedro Castillo’s supporters, ramping up anger and inciting more protests and blockades

“Let there be no more deaths, let his be the last,” she said between sobs. “We don’t want his death to have been in vain,” she told the Guardian by phone.

She sat in the waiting room as coroners carried out a postmortem examination on her brother’s body on Thursday morning. Remo Candia, 50, had been rushed to the city’s Antonio Lorena hospital the night before with a gunshot wound to the abdomen but medics could not save him.

“He was just exercising his right to protest and they shot him at point-blank range,” said Lisbeth.

A lunch on Sunday was the last time she saw the cheerful, popular leader of Urinsaya Collana, the Quechua-speaking campesino community in Anta province where the family lives.

A father of three children – the youngest aged just five – Remo had led farmers from his village to join the protests in Cusco’s regional capital, demanding the resignation of President Dina Boluarte over the 41 civilians who have died in violent clashes with the security forces in little more than a month.

The spiralling violence began when former leader Pedro Castillo was forced out of office and detained on rebellion charges in early December after attempting to dissolve congress and rule by decree in the hope of avoiding a third impeachment trial.

Boluarte, his vice-president, succeeded him but became quickly unpopular as police unleashed deadly violence on Castillo’s supporters, in turn ramping up anger and inciting more protests and blockades.

There was visceral grief and anger in Juliaca, near Peru’s border with Bolivia, as it reeled from the most lethal bout of violence in more than a month of anti-government protests. Under curfew, the city was subdued on Wednesday as mourners, in their thousands, followed the caskets of at least 17 protesters and bystanders who had been killed – without exception – by gunshot wounds.

The dead included a 31-year-old medical student who was helping an injured protester and a 17-year-old girl who volunteered at an animal shelter.

The remains of a police officer were also found in a burned-out patrol car. His companion, who suffered head injuries, says they were attacked by a mob.

Candia was mortally wounded as protesters tried to storm the airport in Cusco, the gateway to Machu Picchu, the country’s pre-eminent tourist attraction. The protesters were demanding Boluarte’s resignation but, analysts say, the anger runs deeper and is rooted in a decades-old schism between the political elite in Lima and the marginalised Indigenous and peasant communities in the Andes and the Amazon.

In Castillo, a former schoolteacher with no previous political experience, many rural Peruvians thought they found a leader who represented them. Despite allegations of corruption, and accusations that he had surrounded himself with cronies and had little grasp of how to govern, many sided with him as he faced down the deeply unpopular opposition-led congress and hostile media.

In poor, largely Indigenous Puno, where close to 90% of the population voted for Castillo in 2021 on his promise to lift up the poor, Governor Richard Hancco said dialogue with Boluarte’s government was out of the question.

“For us, this is a murderous government. There is no value given to life,” Hancco said. “It is completely unacceptable that a government causes more than 40 deaths and there has not been a single resignation.”

Even by the security forces’ standards, Monday’s violence represented a brutal escalation, said Javier Torres, editor of regional news outlet Noticias Ser. “Our security forces are accustomed to shooting people but I think that here they have crossed a line that has not been crossed before.

“It was a massacre – I can’t find any other term to describe it,” he added.

Omar Coronel, a sociology professor and Peru’s Pontifical Catholic University, said Boluarte’s government has formed a tacit coalition with powerful far-right lawmakers who have portrayed the protesters as “terrorists”, a throwback to Peru’s internal conflict with the Shining Path in the 1980s and 90s. Known as terruqueo in Peru, it is a common practice used to dehumanise protesters with legitimate grievances.

“The police force in Peru is used to treating protesters as terrorists,” said Coronel. “The logic is people who protest are enemies of the state.”

Given the utter distrust in political institutions and rising clamour for Boluarte to step down, the plan to bring forward elections by two years to 2024 is too far off, said Torres. “If it continues like this, it will be protest, followed by massacre, and that is just not viable,” he said.

The UN human rights office has demanded an investigation into the deaths and injuries while Peru’s attorney general’s office has opened an investigation for genocide and homicide into the Boluarte and her leading ministers.

At the morgue in Cusco, Lisbeth Candia veered between sorrow and rage. “Why must so many lives be spent just because that woman does not want to leave the government?” she asked.

“She must go. We don’t want her. We want her to pay for the death of my brother, for the deaths of so many,” she said furiously. “We want to live in a new homeland, where we’re not considered second-class citizens.”

READ MORE  Federal environmental and pipeline safety specialists at the site of the oil spill on Dec. 13, 2022. (photo: EPA)

Federal environmental and pipeline safety specialists at the site of the oil spill on Dec. 13, 2022. (photo: EPA)

Meanwhile, federal agencies dispatched pipeline and environmental experts to the scene.

And the state set about sampling water and searching for injured animals.

All of this costs taxpayers — from transporting and housing workers to cladding them in waders that require special disposal because the gear becomes permanently contaminated.

TC Energy, the Canadian company behind the spill, will have to repay some, but not all, of the public money spent on handling it.

This week, several government agencies expressed confidence that they will ultimately recover their expenses.

In the case of the federal and state governments, laws and binding orders apply.

Washington County emergency manager Randy Hubbard said that he isn’t aware of any laws that require TC Energy to reimburse a local government, but the company has vowed to do so.

“From day one TC Energy has been very adamant and forthcoming about offering to cover any County related expenses,” he said in an email, “including but not limited to labor, resources or materials.”

TC Energy reported an annual revenue of more than $13.3 billion and a net income of more than $2 billion in its most recent yearly report.

The Keystone is the company’s biggest pipeline system for oil and carries crude from Canada to refineries in the Midwest and the Gulf Coast. The system has spilled numerous times, but the rupture in Kansas that released an estimated 588,000 gallons of tar sands crude oil was the biggest spill to date.

State and federal expenses

A wide array of government agencies responds to inland oil spills.

At least two Kansas agencies say they can get TC Energy to reimburse for their efforts responding to the spill.

By state law, TC Energy must repay the Kansas Department of Health and Environment. If the company fails to pay, the same law instructs the attorney general to sue.

The Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks said it, too, will recuperate its costs. The agency is tracking staff time, mileage and equipment.

The federal government, meanwhile, could rack up costs not just through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, but also for support from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the U.S. Department of Transportation and more.

Some of that spending of tax dollars will get repaid.

This month, TC Energy agreed to an EPA order that binds the company to reimburse direct and indirect costs within 30 days of being billed.

That includes, for example, the federal government monitoring TC Energy workers and contractors pulling oil from the creek. And the reimbursement order applies retroactively to costs dating back to the spill more than a month ago.

But other federal activities fall outside the order — such as sending pipeline safety enforcers to Washington County.

USDOT’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration said it doesn’t have the authority to seek reimbursement.

County government expenses

The county has already submitted documentation of its costs to the company, Hubbard said. (The Kansas News Service has filed a public information request for the records.)

County emergency workers provided boots on the ground critical to a swift response.

At about 12:30 a.m. on Dec. 8, TC Energy called in a possible leak to a federal hotline for oil spills. By about 1:30 a.m., Hubbard and the county’s road supervisor got involved. The county worked with the company to dam Mill Creek, where thousands of barrels of oil were sliding downstream.

“A better part of the first day was spent building this dam,” Hubbard said in an email. “Additionally, our Road and Bridge crew spent a better part of the first 2 days putting down rock and prepping/grooming roads in the immediate area to better support the anticipated arrival of heavy equipment for the response.”

Hubbard praised TC Energy’s efforts, saying he had witnessed its commitment to remediating the area, keeping workers safe and communicating with landowners.

“TC Energy has been great to work with throughout the entirety of this unfortunate event,” he said. “Additionally, TC Energy has used, and continues to use local contractors whenever possible.”

The company announced it would donate $7,500 to equip local emergency responders with better mobile and radio equipment. It also said it would match donations made by the public to Washington County Hospital.

More about the oil spill

Here are more details about the spill.

1. State environment officials are now finding less benzene and other chemicals downstream from the four-mile stretch of creek that TC Energy isolated last week.

That stretch had already been dammed to hold back floating oil but water continued to flow downstream beneath the surface. As of last week, TC Energy is temporarily diverting water from upstream of the spill, allowing it to bypass and seal off four miles of stream while the cleanup continues.

This week, the state announced that contamination is decreasing downstream in Mill Creek and the river it feeds into, the Little Blue. However, it says people shouldn’t touch Mill Creek anywhere downstream of the spill site. They should keep their pets and livestock away, too.

The Kansas News Service has asked the state for the results of weekly water sampling.

Families who rely on private wells in the area or who use water from Mill Creek or the Little Blue for livestock and ponds can ask TC Energy to test their water. (Email public_affairs_us@tcenergy.com or call 1-855-920-4697.)

2. Oil-soaked animals get treated at a rehabilitation shelter.

“This area is heated, covered, protected, and staffed by a team of wildlife rehabilitation professionals and biologists,” a spokesman for the EPA said by email. “The lead in this response has over 20 years of experience in wildlife rehabilitation and oiled wildlife response.”

Reporters have not been allowed to visit the spill site or the animal rehabilitation shelter, or interview the Fish and Wildlife Service, which works on wildlife matters at the site.

The total number of dead animals isn’t clear, but includes at least one beaver that succumbed despite attempts to treat it.

Scores of fish died, even though oil spills in water bodies generally don’t take the same toll on fish as they do on turtles, birds and mammals that penetrate the oil slick to enter and leave the water. Scientists say the impact on fish increases when oil spills happen in shallow water.

3. Neither the state nor the federal government have released photos of injured, dead or rehabilitated animals that the Kansas News Service has asked for. Kansas says it is withholding the photos because it is investigating the oil spill.

4. TC Oil signed a consent order this month with the EPA that requires it to clean up Mill Creek and its banks.

The company has to recover the spilled oil from the creek and its banks, and remove contaminated soil and plants that could lead to more chemicals reaching the water.

This oil recovery has to continue until the EPA and Kansas Department of Health and Environment agree it is finished. The Fish and Wildlife Service and Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks can also give input.

TC Energy also has to monitor for contamination downstream, but the order doesn’t specify what methods it should use. The Keystone spilled dilbit in Kansas, a special product from the Canadian tar sands that doesn’t behave like traditional crude oil. A National Academies of Sciences study found little in the way of reliable options to detect dilbit once it begins moving below the surface in moving water.

The federal consent order makes no mention of special requirements related to cleaning up dilbit, though top scientists have urged the federal government to change its policies and procedures to distinguish dilbit spills from regular crude oil spills.

5. It's unclear whether the federal government considers the consent order to apply to the entire spill site.

When the pipeline burst, it spewed crude oil into the air that splattered across acres of agricultural land, in addition to the oil that poured into the creek.

The Kansas News Service asked whether the EPA’s consent order applies to all land affected by the spill, not just the creek and its banks.

The EPA replied: “The current order is issued pursuant to the Clean Water Act. It requires the Respondent to conduct removal actions to abate and mitigate the imminent and substantial threat to Mill Creek and adjoining shorelines that is presented by the discharge of oil from the ruptured pipeline.”

But the EPA added that it “continues to coordinate with KDHE on a comprehensive cleanup strategy.”

The EPA also says KDHE may require TC Energy to perform work “that is beyond EPA’s Clean Water Act authority.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.