Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

An exclusive excerpt from the new book 'The Riders Come Out at Night' reveals the first days of a rookie officer who turned whistleblower — and the extreme brutality of a crew of rogue cops

Keith Batt, then a youthful rookie officer, was shocked by the flagrant violations of the law he witnessed while on patrol with the Riders. He blew the whistle, informing OPD’s internal affairs, and setting in motion a historic pair of criminal trials and a sprawling civil rights lawsuit. After a thorough investigation by the Alameda County District Attorney’s office, four of the Riders officers were indicted in Fall 2000 on dozens of charges, ranging from impersonating a police officer, filing false police reports, kidnapping, and assault with a deadly weapon. They were all terminated by OPD. One of them, Frank Vazquez, fled the country and remains a fugitive to this day, most likely in Mexico. Clarence Mabanag, Matthew Hornung, and Jude Siapno all stood trial, receiving hung verdicts in 2003 and a 2005 retrial and charges were eventually dismissed. Batt resigned from OPD and signed on as an officer in Pleasanton, a suburb 30 minutes south of Oakland where he still works.

The civil rights lawsuit brought on behalf of 119 of the Riders victims resulted in a binding reform program mandating sweeping reforms to OPD’s internal affairs process and street policing. That consent decree, known as the Negotiated Settlement Agreement, is still in effect today. Modeled partly on the consent decree used to bring the Los Angeles Police Department to heel in the wake of its Rampart scandal, Oakland’s reform program has gone on to shape many police reform efforts nationwide.

It’s possible that this year that a federal judge will finally give Oakland control over its police department once again — but it’s also possible other scandals lurk beneath the surface that point to systemic problems of violence and accountability that must still be addressed.

This exclusive excerpt from the new book ‘The Riders Come Out at Night’ by Ali Winston and Darwin, recounts the beginning of the reckoning of policing in Oakland, back in the summer of 2000 when Keith Batt went on his first patrol with the Riders.

Nobody really knows how Ghost Town got its name, but the moniker fits. Walled off from most of Oakland by freeways on its northern and eastern borders and warehouses to the west, Ghost Town—known formally as the Hoover-Foster neighborhood — has been haunted since the mid-twentieth century by the combined forces of racism, deindustrialization, and chronic unemployment. It was always a working-class community, but for most of its existence, Ghost Town residents could find decent-paying jobs on the East Bay’s burgeoning industrial waterfront. That changed starting in the 1950s as factories closed, and Oakland’s economy descended into a multi- decade decline.

White residents left the neighborhood, and much of the rest of Oakland, for the prosperity of expanding suburbs. At one point, a high proportion of houses and storefronts in Ghost Town were vacant and boarded up. Huey Newton, cofounder of the Black Panther Party (BPP), referred to West Oakland in his autobiography as a “ghost town but with actual inhabitants.” Newton’s sour comment stuck in the minds of locals, who started using the epithet themselves. If there was any doubt about whether the area should be called a ghost town, it was settled by the 1980s.

The federal “War on Drugs,” launched the previous decade by President Richard Nixon, transformed Ghost Town into a battlefield between rival dealers, and between dealers and cops. For the Oakland police, Ghost Town was hostile territory — a place to drive through cautiously while on patrol, meandering back and forth between West Street and San Pablo Avenue on long, numbered streets crowded with parked, semi-operable cars. In the 1990s Ghost Town truly felt abandoned. Darkness enveloped entire blocks of dilapidated bungalows, run-down apartment buildings, and weathered Victorians illuminated only by the neon glow of corner liquor stores. The sounds of gunfire and sirens were common. Murders were frequent. By this point, the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s were spent, no longer a counterforce offering hope and some measure of order to the mostly Black residents of Oakland’s flatlands. The social decay of racism and poverty could not be held at bay.

This was where Keith Batt found himself after having graduated from Oakland’s 146th police academy on June 2, 2000. Just twenty-three years old, Batt hailed from the small, liberal, mostly white Northern California city of Sebastopol — about as far away from the mean realities of West Oakland as could be. But he’d wanted to be a cop in a place unlike his hometown. He’d heard good things about the Oakland Police Department. It was a professional, hardworking agency in a challenging environment. It was also the first police department that offered him a position.

Boyish, clean-cut, and straitlaced, Batt majored in criminal justice at Sacramento State University. He was a top student in OPD’s academy and earned a reputation as one of the few trainees who would raise his hand to answer questions and volunteer for exercises. He was smart, confident, and energetic.

Batt got into policing for idealistic reasons and felt he could make a difference in a place like Ghost Town. What was obvious to him and other rookies was the scourge of gun violence, fueled by Oakland’s drug trade. The solution, accepted by most of society at the time, was to throw police at these complex social problems. Arrest the bad guys, lock up the dealers, and make the streets safe for the average person. Batt believed in this mission, and he felt certain that it could be accomplished with integrity and compassion for the community.

The recently appointed chief of police, Richard Word, had told the eager rookie that he was among the best of the best. For this reason, he and other fresh-faced cops equipped with the latest training from OPD experts would work shifts under the tutelage of veteran officers in one of America’s urban archetypes of segregation, poverty, and violence.

Batt’s field training officer, Clarence Mabanag, was an entirely different breed. “Chuck,” as he was known to other officers, sported a military-style buzz cut. Short, wiry, tough-talking, he had a reputation for arresting drug dealers by the dozens, often after foot chases that ended in scuffles. Although he was just a patrol officer, Mabanag was admired widely by other street cops and looked up to as a leader. How- ever, many also felt intimidated by him. In the locker room, Chuck led boisterous, foulmouthed shit-talking sessions that created an atmosphere similar to a high school football team’s inner sanctum. Police generally cultivate a sense of fraternity through ritual, language, and intense shared experiences. Mabanag, and OPD officers like him, created an in-group within this in-group. Their crew projected an overabundance of masculine confidence, and a sense among a few acolytes that they belonged to something special.

By any standards, Mabanag was also a problem officer, with the paper trail to prove it. Since he joined the department in 1988, dozens of citizens had filed complaints against Mabanag, including nineteen allegations of excessive force, several complaints over false arrests and false reports, and a 1998 accusation that he used a racial slur. Those arrested by the live-wire patrolman called him quick-tempered, violent, and insensitive. Whereas most officers catch less than a handful of misconduct complaints in their entire careers, Mabanag collected them like baseball cards.

One man, Antonio Wagner, filed a complaint with the city’s Citizens’ Police Review Board (CPRB) claiming that Mabanag punched him in the mouth and handcuffed him during an arrest. Then Chuck lifted Wagner off the ground and dangled him like a yo-yo by the cuffs. Mabanag had also been sued three times in federal court over accusations of brutality. He was also a killer. In 1992 he fatally shot a twenty-six-year-old man who allegedly pointed a gun at other officers (the shooting was ruled in policy by OPD). By 1999, so many people had filed complaints and sued the OPD over Mabanag’s misconduct that his superiors removed him from the field training program after six years.

But in September 1999 Chief Word reinstated Mabanag to the FTO program aft he’d participated in the department’s early intervention program, a series of training courses intended to straighten out the behavior of “high-risk” officers.

Word wasn’t particularly distinguished as an officer. In fact, virtually no one outside the agency had heard of him when Mayor Jerry Brown appointed him to lead the OPD in 1999. Even so, the new chief —at thirty- seven, the youngest in department history — was liked by many old-timers. He had his own reputation as a leathery cop’s cop, and, like Mabanag, Word had worked in the Special Duty Unit (SDU), an anti-narcotics program that, at the time, formed the core of the Oakland Police Department. SDU was one of the force’s hardest-charging units during the chaotic 1980s and 1990s. Its members were known for busting down the doors of cocaine and heroin dealers, and SDU squads racked up thousands of felony arrests over the span of a few decades. At one point in the 1990s, these specialized units overwhelmed the Alameda County District Attorney’s Office with so many felony drug and weapons possession cases that it simply couldn’t charge them all. Word’s rise to chief signaled a return to a more aggressive brand of policing, one that had waned slightly in the late 1990s under the previous chief, Joseph Samuels, and the previous mayor, Elihu Harris. And Mabanag’s reappointment to the FTO program further cemented this shift in attitude.

In a speech before Batt’s graduating class, Word described Mabanag and his peer group of FTOs as the “cream of the crop.” What the chief meant was that Batt was privileged to have the opportunity to train with one of the OPD’s elite patrol officers. Mabanag and his crew epitomized the department’s style of law enforcement and would turn soft rookies into hardened, streetwise officers capable of surviving “Croakland,”2 as some police referred to it cynically. During the academy, a few senior OPD officers working as trainers gave Batt a sense of what kind of trainer Mabanag was. One officer told him not to worry if Mabanag teased him ruthlessly and cruelly. “If he’s making fun of you, it means he likes you,” the cop explained. “If he doesn’t talk to you, that means he doesn’t like you.” In the locker room one day, several of the other trainees told Batt that Mabanag had asked about him, remarking disdainfully that “he better not be some kind of pussy.”

Mabanag and many other senior officers weren’t just physically aggressive. They were openly contemptuous of the idea of constitutional rights for suspects. As soon as they started patrolling together, usually with Mabanag driving and Batt seated shotgun, Mabanag told the rookie to forget what he’d been taught in the academy. Real police work was different. Real police work wasn’t pretty. It was physical, ugly, and dangerous.

True to his reputation, Mabanag bullied Batt incessantly. It began the day they met, with Mabanag dismissively calling his charge “Ike”—short for “I know everything.” It was his way of shutting down the rookie’s concerns about following department policy and abiding by the letter of the law. Mabanag wanted Batt to know that only a few methods worked on Oakland’s streets. He wanted to humble the newcomer, who had performed well in the police academy but was genuinely naïve about Oakland’s dangers. Batt, Mabanag also said, needed to show that he was a “soldier.”

This wasn’t just Mabanag’s view but a message that field training officers throughout the department were getting from the top. New cops needed to be seasoned properly. Criminals in West Oakland were heavily armed and contemptuous of law enforcement. Cops had to be even more dangerous than the bad guys. Another message was that it was time to take back West Oakland from drug dealers. Some local residents who led several of the city’s politically influential neighborhood crime prevention councils— effectively pro-police lobbies that also campaigned for their favored politicians — were calling for more hard-nosed tactics.

To impart this lesson about how he felt Oakland should be policed, Mabanag turned field training into a showcase of OPD methods. On their first night out that summer, Mabanag promised Batt he’d get him into a street fight. Batt initially thought his FTO was joking but soon found out that Mabanag was dead serious.

All police academy graduates are permitted to take a well-deserved short vacation before their first official day in uniform. On June 18, a rested Batt showed up at the Police Administration Building ready to work his first “dogwatch” shift — the inherently dangerous hours from dusk to dawn. He was riding with Mabanag in a well-worn Ford Crown Victoria, the OPD’s standard patrol car. A call came over the radio for a 10851: California police code for a stolen vehicle.

When they arrived at the Adeline Street address given to them, they were greeted by two men. The owner of the stolen car stood in his front yard, clutching his vehicle’s paperwork and ready to give the officers a re- port. The man’s cousin, Kenneth Soriano, was there, too, with his pet Rottweiler tied up behind a waist-high chain-link fence. The dog was barking at the officers.

Mabanag began by asking about the missing car, but then switched his line of questioning to the Rottweiler. “Is that dog tied up?” Before either man could answer, he provided his reason for asking: “I don’t want to have to shoot your dog if he bites me. I’ve done it before.”

Soriano, confused and wanting to discuss his cousin’s missing car, took offense and told Mabanag in a slightly slurred voice, because he was drunk, “I wouldn’t do that if I were you. If you did that, I’d do you, too.”

De-escalation was not in Mabanag’s vocabulary. He responded by telling the twenty-year-old that he was under arrest for public intoxication, even though he was standing on his family’s property. Soriano refused Mabanag’s questionable orders, so the officer began wrestling with him. By this time, a small group of neighbors had gathered; they seemed stunned at how what was supposed to be a routine stolen car report had erupted into a physical confrontation. Batt, too, was surprised by the speed at which Mabanag moved to arrest Soriano, but he knew he had to protect his partner, so he tried holding back the onlookers from approaching. Mabanag, meanwhile, was still grappling with Soriano and barking, “Forty-eight!” into his shoulder radio — the code for requesting backup.

The owner of the stolen car pleaded with Mabanag to stop, but this was the fight the seasoned FTO had promised his rookie, and he wasn’t about to back down. Taking cues from his supervisor, Batt attempted to help Mabanag restrain Soriano. Not that the young man was fighting back. Instead, he tried to avoid being arrested by going stiff and holding on to the fence. Mabanag wrapped his arm around Soriano’s neck and attempted a carotid hold to cut off the flow of blood to his brain, but the hold slipped, choking off Soriano’s breath. He released his grip on the fence and sputtered, “I give up, I give up.” Mabanag responded by throwing Soriano to the ground face-first. The young man’s head and chest slammed against the pavement. Swiftly, two other officers appeared. Francisco “Frank” Vazquez and Jude Siapno ran up from their patrol car and immediately began punching and kicking Soriano as Batt attempted to cuff him. After pummeling him, the officers stuffed him into the back seat of a patrol car.

Mabanag, dusting himself off, ordered Batt to write the arrest report and to be sure to add that Soriano elbowed him, even though the detained man hadn’t thrown a blow at any of the four officers. Nevertheless, the trainee complied and scribbled the report. In a separate arrest report that Mabanag later wrote himself, he withheld the fact that he, Siapno, and Vazquez forcefully subdued Soriano. Mabanag showed this passage to Batt, explaining that the omission would help them avoid scrutiny from supervisors and the Internal Affairs Division. This was how you did the job and avoided the paper pushers and rats in the PAB: Oakland’s Police Administration Building.

Mabanag and Batt then drafted a statement for Soriano to sign. The two officers then drove Soriano to the Oakland City Jail on Seventh Street next to the Police Administration Building for booking. Not long after, Mabanag pulled over, parked the car, and took out his clipboard with Soriano’s signed statement. He looked over at Batt and said, “Hey, kid, let me show you a trick.” At this point, Soriano’s partially filled-out statement said only that he had resisted arrest. On several blank lines at the bottom, just above the man’s signature, signed under duress, Mabanag wrote in Soriano’s voice the following: “I’m sorry for giving the police a hard time. The officers were not the ones who beat me. I guess I was just mad cause somebody threatened my family earlier, and my temper got the best of me. That’s why I took it out on the police. This is a true statement.”

It was utter fiction, but Batt understood immediately that this was his FTO’s way of concealing the brutal beatdown and humiliating Soriano by forcing him to sign a false confession exonerating the officers. The large cut and bruise on Soriano’s forehead, caused when Mabanag threw him to the sidewalk, and any other injuries he might have sustained from both the chokehold and Vazquez’s and Siapno’s punching him, were explained away as being due to a fight earlier in the evening with someone else.

This was Batt’s very first taste of the real OPD, and it didn’t sit well with him. Although Soriano was never charged with a crime, seeing him prosecuted was never the point. The punishment the OPD officers wanted to exact was meted out on the street in the form of a demeaning assault. It was a stark warning to Soriano, his family, and the entire neighborhood that someone like him — a Black man offended by a threatening remark — should never challenge an Oakland police officer.

A few nights later, Mabanag decided that he and Batt would accompany a group of officers to serve a search warrant on a Chestnut Street house where a drug dealer had reportedly set up shop. Frank Vazquez wrote the warrant and led the raid. He pounded on a metal security door. Then, without giving anyone inside a chance to open up, officers used “the hook,” a large pry bar–like tool, to force it open.

A woman inside the house, Janice Stevenson, began screaming, asking the police what was happening. The hook failed to rip the door off, and she opened it. The officers poured inside. Vazquez promptly drew his gun and pressed it against Stevenson’s head.

“Bitch, we got you now,” one of the cops gloated.

The officers tore through the house and threw the occupants’ belongings on the floor. Batt was stationed out front in case anyone inside the house tried to escape. Beside him was Jerry Hayter, a grizzled sergeant who was in charge of overseeing the dogwatch squad. Not much time had passed when a single gunshot from behind the house pierced the air. Batt was alarmed. Even Hayter raised his eyebrows at the noise, but moments later, Officer Jude Siapno’s voice came over the radio stating that the “K3,” police code for shots fired, was a dog he had just killed.

Siapno and Mabanag had found the woman’s dog tied up to a post in the basement. It wasn’t threatening anyone. However, Siapno wrote in his report that the animal was untethered and lunged at him, and that he fired a single hollow point bullet into its brain in self-defense.

Batt’s discomfort with the senseless killing of the dog was evident to others at the scene. But Mabanag bragged to Batt that he’d shot six dogs before. The remarks were a none-too-subtle way of telling the trainee that he should get used to putting down dogs. All through the 1990s, OPD officers frequently killed dogs in what can be described only as sport. Occasionally, they were justified in killing an unleashed and menacing pit bull. But many times, the animals were leashed. Cops were often accused of cutting the leashes afterward to cover up the needless loss of life. The animal killings served another purpose: as punishment for people the officers suspected of operating drug houses or hiding fugitives.

Batt and another rookie, Steve Hewison, were made to dispose of the dog’s carcass later that night. The officers, having discovered crack cocaine and a sawed-off .22-caliber rifle in the basement, arrested Stevenson. Frank Vazquez stole some of the crack, which he used later to pay an addict for information about another drug supplier—this, according to a conversation that Keith Batt witnessed. The drugs were used to make yet another con- trolled drug purchase that served as the basis for another search warrant.

At a lineup the next evening, before they started their shift, Sergeant Hayter joked in front of the assembled group of officers, including Siapno, Vazquez, Batt, and Mabanag, that there were “two versions of the story” regarding the killing of the dog. One version, he chuckled, was that the dog was just “licking Jude’s hand” when Siapno put a bullet between its eyes. The other was that the dog had growled and lunged at him.

Batt’s first week on the force continued like this, filled with vulgar displays of power, impunity, and dishonesty by his training officer and half the other cops they worked with. He followed Mabanag around West Oakland, sometimes just the two of them, but often with others, chasing down narcotics suspects in chaotic pursuits that frequently ended in beatings. In the small hours of the morning before the sun came up, Batt and the rest would change out of their uniforms and drive home to sleep away the first half of each day. However, the newbie cop was losing sleep over the transgressions he witnessed. It wasn’t just that officers were brutalizing people and filing false reports; some of them appeared to take pleasure in these crimes.

On the night of June 26, Mabanag and Batt were driving along Thirty- Fourth Street in West Oakland when they spotted a man who seemed to be acting strangely. In Ghost Town, the mere fact that he was walking down the street at ten thirty was enough to raise suspicion. During the height of the OPD’s version of the stop-and-frisk policy, simply being Black was cause enough for officers to detain a person and search for weapons and drugs. Mabanag pulled up alongside the pedestrian and hit the brakes.

“Grab that guy,” he ordered his trainee.

Batt rushed from the car and cuffed the man, who was already protesting that he’d done nothing wrong. They placed him in the back seat, then searched the area for drugs. Mabanag explained that panicked suspects usually tossed their contraband into weeds or over fences. After briefly scanning the ground and bushes, he came up with two small rocks he claimed were crack cocaine. The patrolman took out his notebook and began scribbling a report as Batt looked on. Then Mabanag handed the rookie his notes and told him, “Copy it.”

It was a strange command, but Batt dutifully began copying the report word for word in his own handwriting. However, when he got to the part that said that he had witnessed the man throw contraband on the ground, Batt paused.

“I didn’t see that,” he said.

To write it would be a lie. Cops are supposed to tell the truth, even if it means not having the complete, ironclad evidence needed to charge some- one for a suspected crime.

Mabanag ignored the rookie’s complaint and explained that in order to send the man to prison, they needed to link him directly to the narcotics. The best way to do that was for Batt to write that he’d seen the man drop the crack cocaine that Mabanag recovered almost immediately. If his decade on Oakland’s streets had taught the veteran anything about the law, it was that prosecutors needed particular kinds of evidence and statements in order to secure a guilty plea or conviction, and Mabanag was eager to provide these gifts.

But Mabanag’s dishonesty bothered Batt in a deeper way. It wasn’t even clear to Batt whether his superior had actually discovered the narcotics on the ground that night. He could have planted the evidence there. Mabanag and many other officers would later be accused of having planted drugs on numerous suspects over the years and also paying informants with drugs they’d confiscated from others. Batt hadn’t been on the job for even a week, but his mind swirled with suspicion.

Mabanag certainly wasn’t the only FTO who had trainees copy falsified police reports. Frank Vazquez had also recently ordered Hewison, another graduate of the 146th police academy, to copy an arrest report stating that he’d observed a suspect toss a bag filled with forty-eight crack rocks between two houses just before he was captured. Hewison had seen no such thing, but, fearing a bad write-up, which could put a quick end to his police career, he agreed to falsify his report.

Much of what the Oakland PD did in Ghost Town and other predominantly Black and Latino areas of the city in the late 1990s and early 2000s involved this kind of policing. Between responding to calls such as car thefts and domestic violence, cops would jump out on anyone who might be buy- ing or selling weed, cocaine, and heroin or other narcotics. Anyone they recognized as being on probation or parole was also an immediate target for a stop-and-frisk.

West Oakland cops such as Mabanag, Siapno, Vazquez, Hayter, and many others had become so zealous in their mission that, by the late 1990s, they’d earned a nickname: the Riders. It came from a favorite story that was told and retold in OPD locker rooms and went something like this: A Black man was driving through West Oakland one day when a policeman stopped him and cited him for a traffic violation. Pleasantly surprised by the officer’s courteous and businesslike demeanor—no insults, no brutality, no requests to search the car, just a simple ticket — the driver thanked him for being “nice.”

This puzzled the officer. “Why are you thanking me for being nice?” he asked.

“Because you all aren’t always so nice,” the man explained. “Like at night. This isn’t at all what it’s like at night. At night, the Riders come out.”

READ MORE  Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio) exits the House floor Monday. (photo: Jabin Botsford/WP)

Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio) exits the House floor Monday. (photo: Jabin Botsford/WP)

Democrats describe the panel as an unprecedented breach of protocol

The subcommittee, approved on a party-line 221-211 vote, will be empowered to investigate any federal agency that collects information about Americans, even in cases of an ongoing criminal investigation — a carve-out at odds with the Justice Department’s long-standing practice of not providing information about ongoing investigations.

The subcommittee, which will be housed under the Judiciary Committee and led by that panel’s chairman, Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), is expected to have resources akin to the House select committee that investigated the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol — a concession extracted last week from GOP leaders by hard-line detractors of Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) in exchange for the votes necessary to make him the new speaker.

The broad resolution also explicitly authorizes the select committee to seek access to highly classified information provided by intelligence agencies to the House Intelligence Committee. Members of that panel are often briefed on extremely sensitive information with contents that, if widely shared, could damage national security and endanger the lives of American intelligence officers and their assets.

“Its mandate is whatever Jim Jordan wants to do,” said one congressional investigator who works on oversight issues and who, like others in this report, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal discussions and plans.

Republicans, who have accused Attorney General Merrick Garland of abusing investigative powers to target conservatives, have compared the new committee to the Senate Church Committee formed by Democrats in 1975 to investigate civil liberties abuses by intelligence agencies. Democrats have countered that the committee has been born out of the grudge match over the FBI’s investigation of one person: Trump.

“Jim Jordan and Kevin McCarthy claim to be investigating the weaponization of the federal government when, in fact, this new select subcommittee is the weapon itself,” Rep. Jerrold Nadler of New York, the ranking Democrat on the House Judiciary Committee, said in a statement. “It is specifically designed to inject extremist politics into our justice system and shield the MAGA movement from the legal consequences of their actions. In order to become Speaker of the House, Kevin McCarthy sold out our democracy by handing power-hungry Jim Jordan subpoena power and a green light to settle political scores under the phony pretext of rooting out conservative bias.”

The Justice Department declined to comment on the proposal.

Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.) told reporters Tuesday that he will be serving on the subcommittee, but it’s unclear who else will be tapped by GOP leadership.

Rep. Nancy Mace (R-S.C.) said after the vote to form the committee: “Jim Jordan is the most powerful chairman in Congress, with broad discretion on what he wants to investigate now. What I’m interested in seeing is who will be sitting on this committee. [Jordan] gets to handpick.”

While the resolution establishing the subcommittee is ambitious — alarmingly so to Democrats, who view the panel as a political attack machine disguised as an oversight body — how it will work in practice remains to be seen.

The Justice Department has at times quarreled with congressional committees over what information should or should not be shared with Congress, including during the Trump administration when Jordan and others accused the Justice Department of unfairly targeting the president.

Such fights can drag on for months and occasionally flare into uglier confrontations, such as when the GOP-controlled House in 2012 voted to hold Attorney General Eric Holder in contempt over Republicans’ unsatisfied demands for Justice Department documents.

While some of the panel’s expected membership sets the stage for potential confrontations with the Biden administration, some Democrats and intelligence officials are already voicing concern about the chilling effect the Republican effort may have on ongoing investigations.

Some Republicans, for example, have already expressed skepticism about reauthorizing one of the government’s crown jewels of intelligence gathering: Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, which expires later this year. It’s possible that Republicans will hold the program hostage if the Justice Department and other relevant agencies decline to answer the subcommittee’s requests, though such threats have proved hollow in the past.

The new panel will consist of eight Republicans and five Democrats, and unlike on other committees, members of the subcommittee do not have to serve on the Judiciary Committee to be appointed. Democrats are not planning to boycott the committee, according to people familiar with the matter, as McCarthy did when he pulled his picks to serve on the House Jan. 6 panel. It’s also possible that some lawmakers who are currently under investigation by the Justice Department may be taking part in the examination of federal investigations.

Rep. Scott Perry (R-Pa.), whose phone was taken as part of a Justice Department investigation of the use of illegitimate electors in efforts to overturn Joe Biden’s victory in 2020, declined to recuse himself from possibly sitting on the subcommittee, telling ABC News over the weekend that being a subject of an investigation shouldn’t be disqualifying.

“Why should I be limited, why should anybody be limited, just because someone has made an accusation? Everybody in America is innocent until proven otherwise,” Perry said. “I would say this: The American people are really, really tired of the persecution and instruments of federal power being used against them.”

Democrats also predict that the new panel will worsen the relationship between intelligence agencies and Congress, because of concerns about political battles over classified information.

Congressional investigators anticipate the subcommittee will need to hire a team of outside litigators to handle a looming fight over congressional oversight authority that could end up in the Supreme Court.

“There are already grand jury regulations and rules that will prevent the Justice Department from complying with subpoenas related to ongoing investigations — like the January 6 investigation — but Jordan will likely say that he’s authorized by Congress, so they will end up in court,” said a second congressional investigator. “This isn’t going to end anytime soon.”

READ MORE  Supporters of former President Jair Bolsonaro clash with security forces as they raid the National Congress in Brasilia. (photo: Getty Images)

Supporters of former President Jair Bolsonaro clash with security forces as they raid the National Congress in Brasilia. (photo: Getty Images)

Brazil's judicial authorities have ordered the arrest of top public officials after rioters stormed key government buildings in Brasília.

The officials also include Brasília's former public security chief Anderson Torres and others "responsible for acts and omissions" leading to the riots, the attorney general's office said.

Mr Torres denies any role in the riots.

Colonel Fábio Augusto, the police commander, was dismissed from his role after supporters of ex-President Jair Bolsonaro stormed Congress, the presidential palace and the Supreme Court.

The rioting came a week after President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, widely known as Lula, was sworn in.

The dramatic scenes involved thousands of protesters, some clad in yellow Brazil football shirts and waving flags, who overran police and ransacked the heart of the Brazilian state.

Of the approximately 1,500 people arrested and brought to the police academy after the riot, officials say that nearly 600 have been taken to other facilities, where police officials have five days to formally charge them.

Earlier on Tuesday, the federal intervenor in public security accused Mr Torres of "a structured sabotage operation".

Ricardo Cappelli, who has been appointed to run security in Brasília, said there was a "lack of command" from Mr Torres before government buildings were stormed.

Lula's inauguration on 1 January was "an extremely successful security operation," Mr Cappelli told CNN.

What changed before Sunday was that, on 2 January, "Anderson Torres took over as Secretary of Security, dismissed the entire command and travelled", he said.

"If this isn't sabotage, I don't know what is," Mr Cappelli added.

Mr Torres said that he deeply regretted the "absurd hypotheses" that he played any part in the riots.

He said the scenes, which occurred during his family holiday, were lamentable and said it was "the most bitter day" of his personal and professional life.

Lula has accused security forces of "neglecting" their duty in not halting the "terrorist acts" in Brasília.

Public prosecutors asked on Tuesday for a federal audit court to freeze Mr Bolsonaro's assets in light of the riots.

The former president, who has condemned the riots, has not admitted defeat from October's tight election that divided the nation, and flew to the US before the handover on 1 January.

On Monday, he was admitted to hospital in Florida with abdominal pain relating to a stabbing attack during his election campaign in 2018. Reports say he left the hospital on Tuesday.

Mr Bolsonaro said on Tuesday that he intended to return to Brazil, telling CNN that he would bring forward his departure from the US, which was originally scheduled for the end of January.

A day after the riots, heavily armed officers started dismantling a camp of Mr Bolsonaro's supporters in Brasília - one of a number that have been set up outside army barracks around the country since the presidential election.

Mr Torres, who previously served as Mr Bolsonaro's justice minister, was fired from his role as Secretary of Public Security on Sunday by Brasília governor Ibaneis Rocha.

Mr Rocha was himself later removed from his post for 90 days by the Supreme Court.

Lula has also taken aim at the security forces, accusing them of "incompetence, bad faith or malice" for failing to stop demonstrators accessing Congress.

"You will see in the images that they [police officers] are guiding people on the walk to Praca dos Tres Powers," he said. "We are going to find out who the financiers of these vandals who went to Brasília are and they will all pay with the force of law."

Video shared by the Brazilian outlet O Globo showed some officers laughing and taking photos together as demonstrators occupied the congressional campus in the background.

Protesters had been gathering since the morning on the lawns in front of the parliament and up and down the kilometre of the Esplanada avenue, which is lined with government ministries and national monuments.

Despite the actions of the protesters, in the hours before the chaos, security had appeared tight, with the roads closed for about a block around the parliament area and armed police pairs guarding every entrance into the area.

The BBC had seen about 50 police officers around on Sunday morning local time and cars were turned away at entry points, while those entering on foot were frisked by police checking bags.

According to Katy Watson, the BBC's South America correspondent, some protesters aren't just angry that Mr Bolsonaro lost the election - they want President Lula to return to prison.

Mr Bolsonaro has gone very quiet since losing October's elections, she said, adding that in not publicly conceding defeat, he's allowed his most ardent supporters to remain angry over a democratic election that he legitimately lost.

The former president condemned the attack and denied responsibility for encouraging the rioters in a post on Twitter some six hours after violence broke out.

On Tuesday, his son, Brazilian Senator Flavio Bolsonaro, said people should not try to link his father to the riots, stating that he has been silently "licking his wounds" since losing the election.

READ MORE  Pro-choice campaigners rally at the Texas state capitol in Austin. (photo: Eric Gay/AP)

Pro-choice campaigners rally at the Texas state capitol in Austin. (photo: Eric Gay/AP)

More than 38,000 signatures collected for proposal that would decriminalize abortion in city despite statewide ban

Abortion in Texas has been banned since August 2022, following the supreme court decision to overturn Roe v Wade last summer.

The campaigners hope to pass what they are calling the San Antonio Justice Charter, which would also end criminalization for low-level marijuana possession, and put limits on police use of no-knock warrants and chokeholds.

San Antonio, Austin and Waco – all in Texas – already passed resolutions to de-prioritize the investigation of abortion crimes through their city councils in 2022, at the same time as a string of progressive district attorneys across the country vowed to resist state abortion bans that came into effect when the federal right to abortion ended in June.

Other cities and towns have also tried to wrest the abortion issue out of state hands – the New Orleans city council passed a similar resolution in July 2022, and Rodnor, Pennsylvania, passed an ordinance trying to pre-empt any future abortion ban, should one take hold in the state.

Anti-abortion advocates have also used similar logic to create so-called “sanctuary cities for the unborn” in states where abortion rights are protected.

But the San Antonio initiative would be the first of its kind explicitly banning law enforcement from criminally investigating abortion. “[Currently], police are still actually allowed to make arrests or conduct investigations for so-called abortion crimes,” said Mike Siegel, the co-founder of Ground Game Texas, one of the groups organizing around the petition.

“But if the voters approve our justice charter, police will be banned from taking any enforcement action.”

It is also the first example of a group attempting to undermine state policy at the city level through a ballot proposal – so far, city councils, not citizens, have been the ones passing initiatives bucking state laws on abortion.

“It’s not just city council members passing a resolution. The strategy is to show that thousands and thousands of San Antonians do not want to have abortion be a crime in the city,” said Rachel Rebouché, interim dean at Temple Law School.

The city clerk’s office has until 8 February to verify the signatures. Organizers say they have collected well beyond the 20,000 signatures required to put the initiative on the May ballot, in anticipation of some signatures being rejected – as is common during the verification process.

If the initiative passes in May, it will throw up novel legal questions over whether state law trumps local law in such cases. Those questions could be tested in court.

“It essentially pits the city against the state,” said Rebouché. “It could be one of the first cases that we see litigated where the city is sued, or questioned by the state, which could assert its power that state law should override city policy.”

Siegel believes the campaigners are on strong legal footing, because San Antonio is a so-called “home rule” city, which, under the Texas constitution, enjoys some autonomy from the state.

Whatever its fate, Rebouché said the symbolic message of the effort is a powerful one. “It may not have legal force … but it certainly does something similar to Kansas, or Kentucky, where it became clear that there is popular antipathy for these abortion restrictions,” she said.

Siegel said he hoped San Antonio will be a blueprint for similar ballots in other cities in Texas. If successful, he believes this could be a substantial roadblock to the Texas abortion ban, because the state relies heavily on city police.

He said: “City police make up the vast majority of law enforcement in the state of Texas. If we can convince the big cities to say ‘we won’t use our police’, that will take away most of the state’s ability to enforce these laws.”

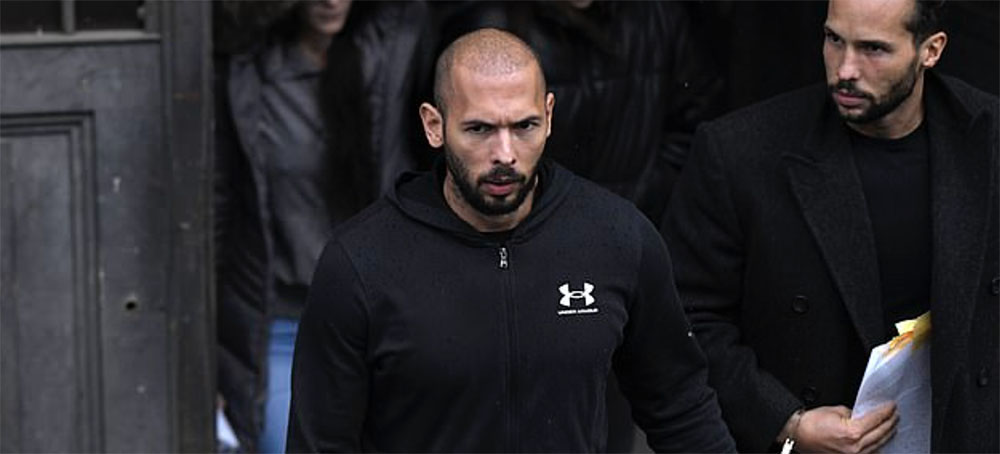

READ MORE  Andrew Tate is pictured leaving court yesterday alongside brother Tristan as their appeal was denied. (photo: AP)

Andrew Tate is pictured leaving court yesterday alongside brother Tristan as their appeal was denied. (photo: AP)

Why millions of men admire internet misogynist Andrew Tate.

The 36-year-old American-born, British-raised former kickboxing champion was arrested on December 29 in Bucharest, Romania, on charges of rape and human trafficking. Tate employed as many as 75 women in a webcam business; some have accused him of imprisoning them and forcing them to perform sex work. Many of his fans are expressing support for his plight, arguing that Tate is a positive force on men and that the Romanian government is trying to silence him for telling the truth. Tate has encouraged that view. As he was being led away in handcuffs, he could be heard telling cameras that “the Matrix has attacked me,” and he tweeted, “It seems every generation’s great revolutionaries suffer from unfair imprisonment.”

Tate is just one of many figures who make up the “manosphere,” an internet ecosystem that combines self-improvement advice with casual and sometimes violent misogyny. Robert Lawson, an associate professor in sociolinguistics at Birmingham City University in the UK and author of the forthcoming Language and Mediated Masculinities, studies how men communicate with each other online. He spoke to Today, Explained’s Noel King about why Tate appeals to some misogynistic men today.

Below is an excerpt of the conversation between Lawson and King, edited for length and clarity. There’s much more in the full podcast, so listen to Today, Explained wherever you get your podcasts, including Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and Stitcher.

Noel King

When did you become aware of Andrew Tate? Do you remember when this guy crossed your radar?

Robert Lawson

I’m interested in language and masculinity, particularly in media spaces. And so unfortunately, through my line of research, I have to spend time on the less enjoyable, less pleasant parts of the internet. So I spend time on manosphere subreddits, manosphere blogs, forums, and so on, trying to understand how masculinity gets configured and understood in these places. I think it was in one of those forays that Tate originally popped up, and it would probably have just been something that was linked to a Jordan Peterson video or a Ben Shapiro video or a Steven Crowder video. This is what’s occasionally called the “intellectual dark web.” YouTube’s algorithms put it through to my front page.

From there, what YouTube’s algorithms do and a lot of other social media sites do: They start to feed you more of the same content. The idea is to drive engagement, and to drive ad views in particular. It becomes a really dangerous pathway from one form of content that might seem fairly innocuous to potentially more extremist and more radical content.

I was interested in why this guy was so popular. What is it that he’s selling that people are buying? If you go on any YouTube video of him at all and you read the comments under the video, they’re almost all universally positive, praising Tate for how insightful, how brave, how inspirational he is. There’s very few dissenting voices on those YouTube comments.

Noel King

As you listened to Andrew Tate, talk to me about where your mind went on the question of: This man appeals to millions of people — why?

Robert Lawson

I think that he is so seductive to such a big audience because the image of masculinity that he sells is one that’s very rooted in traditional male characteristics. He’s very big on this idea of the alpha male, the man that’s in control, that always knows what he’s doing, that always gets what he wants, that has everyone waiting [on] them hand and foot, and this idea that he’s infallible. I think some men can see that as a particularly attractive trait, but he’s also big on conspicuous consumption. He lives a very jet-set lifestyle: fast cars, private planes, mansions, expensive holidays away.

And then he has really traditional and, to my mind, outdated views about what a relationship should look like, and what the role of men and women in those relationships should be: The man is not just the protector but the patriarch, the provider. What he says goes, it’s his way or the highway; women are only there to attend to the house, to look after the kids, to really be in service of the relationship. I think my immediate reaction was probably one of sadness that this is the image of masculinity that sells.

Noel King

What is it about the society that we’re living in in 2023 that makes Andrew Tate acceptable and attractive to millions of men?

Robert Lawson

One of the best accounts that I’ve read as to why young men in particular find this articulation of masculinity and someone like Tate advocating for it is Michael Kimmel’s idea of aggrieved entitlement. It’s based on the idea that over the course of the last 20 to 30 years, the world has changed in a way that has decentered primarily young, white men, and they’ve moved from the center of society to the margins of society.

Someone like Tate is attractive because he recenters young white men in a really obvious and very explicit way and basically says, “You’re important, you’re needed, your masculinity is needed to fight against all of the changes that are happening in the world. The world is no longer for you or wants to invest in you.” No longer are women reliant on men financially or emotionally. Someone like Tate basically says we will fight against that, by reclaiming this sense of primal, traditional masculinity. And that’s a story that goes all the way back to even the 1980s.

A lot of what Tate is saying in some sense isn’t actually new. It’s a rearticulation of a crisis of masculinity discourse that we see back in the 1970s, back in the 1980s, through the men’s movement led by people like Robert Bly and so on, where there was a sense of reconnecting with your own masculinity as a way of fixing the world. He’s only another entry in a long line of other men who have done something similar.

Noel King

Does your research show us anything about whether these young men who are impressed or seduced by Andrew Tate are fundamentally hateful people? Are they fundamentally misogynist, or are they unmoored young men who are being taken for a ride by a misogynist con artist?

Robert Lawson

Someone like Tate tries to normalize misogyny. He makes it seem socially acceptable. He wraps it up in a discourse of rationality: “This is just the way that the world is. This is just the way that people are.” I don’t think we can say that the men that engage with this content are fundamentally misogynistic. It might be that through a process of repeated engagement with his content, of posting on forums about him or on Twitter or on YouTube comments or whatever, that they may be nudged toward these positions. But that’s what a lot of radicalization looks like: taking someone from one position and gradually moving them along that path of radicalization, where viewpoints which initially seemed extreme become normalized.

Noel King

So the question then becomes, if not Andrew Tate, then what? We want to do better than this man. Where should young men be able to go if they want optimism and strength and attention to men’s issues, if we can call them that, but without the misogyny, without the hatred of women?

Robert Lawson

So first and foremost, I would say that young men shouldn’t be looking at social media personalities for what it is to be a man. They’re much better off looking within their local communities, their families, and their friendship networks to emulate masculinities that they find supportive, nurturing, and healthy. Places like community groups are really important spaces for young men to meet other men that they can look up to and that they can be mentored by. For those young men who are really struggling with their own sense of masculinity and what it is to be a man, things like counseling can be really helpful, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with seeking those kinds of forms of support out.

As far as the manosphere goes, I have hopes — not high hopes but some hopes — of what a more progressive manosphere may look like, one that’s free of the misogyny and the anti-feminist stances that we see in a lot of manosphere spaces. Whether that will actually come to pass is an open question. But Tate sells this really romanticized, and to me quite superficial, idea of what it is to be a man. I know loads of men. I don’t know anybody who acts or talks or behaves like Andrew Tate. Tate is a Hollywood form of masculinity, but it’s one that is as deep as a puddle. There’s no substance. The men that I look up to — people like my dad, teachers I had in school, instructors I had when I was in my youth groups — those are the men that have given me the biggest lessons of my life. Those are the men that I will continue to look up to and learn from. And there’s men out there like that that other young men can aspire to be like and look up to and learn from and be guided by. But I don’t think Andrew Tate is the one that we should be putting up on a pedestal.

READ MORE  Planes remained at their gates at Newark Liberty International Airport on Wednesday morning. (photo: Jeenah Moon/NYT)

Planes remained at their gates at Newark Liberty International Airport on Wednesday morning. (photo: Jeenah Moon/NYT)

The Federal Aviation Administration said it had lifted a pause on all domestic departures, but thousands of flights were still delayed. There was no evidence of a cyberattack, the White House said.

Here’s what to know:

- More than 5,000 flights within, into or out of the United States had been delayed on Wednesday, according to FlightAware, a flight tracking service. The delays were spread across the country and affected multiple carriers.

- Passengers across the country said their plans had been scuttled, with airport employees sometimes knowing little more than passengers.

- President Biden said that he had spoken with Pete Buttigieg, the transportation secretary, and that he had asked him to report back when a cause for the failure had been identified. There was no evidence of a cyberattack, the White House said.

Three of the bison on the American Prairie reserve in Montana. Between 30 million and 60 million bison once roamed the United States. (photo: NYT)

Three of the bison on the American Prairie reserve in Montana. Between 30 million and 60 million bison once roamed the United States. (photo: NYT)

Bison once numbered in the tens of millions in the United States. Now, a nonprofit is working to restore the shortgrass prairie, where the American icons and their ecosystem can thrive again.

Snorting and quietly bellowing, their feral odors riding the wind, they slowly trot across the prairie hills, eager to maintain distance from the truck.

This knot of bison — colloquially referred to as buffalo, though they are not the same species — is part of a project to rebuild a vast shortgrass prairie not only to return large numbers of bison here, but also to eventually restore the complex and productive grassland ecosystem the animals once engineered with their churning hooves, waste, grazing and even carcasses.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.