Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Our twenty-first-century culture of performed remorse has become a sorry spectacle.

“Least said, soonest mended” is advice from another century, candle and quill, ox and cart. This past March, the day after Will Smith smacked Chris Rock at the Oscars and failed to apologize to him during his acceptance speech, he apologized on his Instagram account: “I was out of line and I was wrong.” Twitter blew its top! “This is bullshit,” one guy tweeted. “Any normal person is in jail.” Plainly, the Instapology was insufficient. In July, Smith apologized again, in a nearly six-minute video in which he looked as harried and trapped as Steve Carell in “The Patient,” a prisoner in a basement rec room. “Disappointing people is my central trauma,” Smith said into the camera or, actually, multiple cameras. “I am trying to be remorseful without being ashamed of myself, right?” Twitter blew its top! It was either not enough or, oh, my God, please stop. One online viewer sympathized: “Literally me when my mom forces me to apologize to my siblings.” As for Chris Rock, he reportedly said, onstage, “Fuck your hostage video.” By then, Twitter was blowing its top about something else.

It’s easy to blow your top, God knows. If you’re being treated like crap, and nothing you’ve tried has put a stop to it, or if the former President of the United States keeps on saying horrible, wretched things, and you notice that some rich nitwit is getting slammed on Twitter for doing the same thing that’s been done to you, or for saying what the ex-President just said, it can feel good to watch that nitwit burn. But that feeling won’t last. And when that nitwit apologizes it won’t be enough. And the world will have become just a little bit rottener.

Rating apologies and listing their shortcomings started out as a BuzzFeed kind of thing, and then it pretty quickly became a corporate kind of thing: human resources, leadership institutes, political consulting. In 2013, the Harvard Business Review published an essay on the Power Apology. Knowing how to apologize on Twitter became crucial to brand management. “It’s easy to say sorry, but knowing how to say it effectively on Twitter is an essential skill that both brands and celebrities should learn,” a communications manager advised not long afterward, offering nine lessons “on the art of the Twitter apology.” You could do it well, or you could do it badly. Likely, this could be quantified: you’d see it in the price of your stock, the number of your Twitter followers, or the percentage change in your Netflix viewership. As of 2022, even Forbes rates apologies. It seldom helps your vote count, though: politicians who apologize tend to suffer the consequences, which is why they generally brazen these things out.

It’s a good idea to say you’re sorry when you screw up, and to say it well, and to mean it, and to try to make amends. But are people getting worse at that? Or are celebrity publicists, political advisers, corporate lawyers, higher-ed administrators, and media-relations departments just avoiding lawsuits, clearing profits, heading off student protests, and directing news stories by advising people to (a) demand apologies and (b) make them? “Examples of failed apologies are everywhere,” the psychiatrist Aaron Lazare wrote in “On Apology,” a book published not last week but nearly two decades ago. Distressed at a seeming explosion of cheap, showy, and insincere apologies, Lazare got curious about where they’d all come from, like the day you find ants swarming your kitchen counter and yank open all the cupboards, exasperated. He dated what he called the “apology phenomenon” to the nineteen-nineties, but he struggled to understand what had driven this change. He suspected that it may have been due, in part, to “the increasing power and influence of women in society,” because women apologize a lot, he explained, and like to be apologized to. As far as I know, no one asked him to apologize for that comment. But if he’d made it today he’d be in the soup.

Rituals of atonement and forgiveness lie at the heart of most religions, a testament to the human capacity for grace. On Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, Jews fast and pray and repent. Jesus brought this spirit to Christianity and taught his followers to pray to God to “forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.” The early Christian church developed what became the Sacrament of Reconciliation: confession, and penance. There are many steps to atonement in Islam, from admitting a wrong to making restitution and asking for God’s forgiveness. Jews, Christians, and Muslims make themselves right with God. Buddhists, who worship no god, make themselves right with other people. Hindus practice Prayaschitta, rituals of absolution. Mainly, it’s the forgiveness and the atonement that matter.

Apology, though, has a different history. You can confess without apologizing and you can apologize without confessing, and this might be because, historically, an apology is a justification—a defense, not a confession. As the philosopher Nick Smith pointed out in “I Was Wrong” (2008), the word “apology,” in English, didn’t suggest a statement of regret until around the sixteenth century, when, in Shakespeare’s “Richard III,” Buckingham begs Richard’s pardon, for interrupting his prayers, and Richard says, “There needs no such apology.” Medieval Christians practiced what the historian Thomas N. Tentler called “a theology of consolation,” consisting of four elements—sorrow, confession, penitence, and absolution—whose purpose was reconciliation with God and with the body of the faithful. In “Forgiveness: An Alternative Account,” Matthew Ichihashi Potts, a professor of Christian morals at Harvard Divinity School, offers what he calls “a modest theological defense of forgiveness.” His argument follows that of the philosopher Martha Nussbaum, who, in “Anger and Forgiveness” (2016), argued that forgiveness isn’t salutary for either party if, in order to give it, you insist on an apology. Potts calls this “the economy of apology.” It’s not better than vengeance, since to demand an apology and to delight in the offender’s grovelling is vengeance by another name. His evidence doesn’t come from Twitter; it comes mainly from novels, including Marilynne Robinson’s “Gilead” and Toni Morrison’s “Beloved.” Forgiveness, for Potts, is not an exchange—forgiveness granted in return for the opportunity to witness a spectacle of abasement and self-loathing—but a promise not to retaliate. Demanding an apology in exchange for forgiveness can never constitute healing, or deliver justice; it is, instead, a pleasure taken by people who delight in witnessing the suffering of those in their power (if only briefly). There is no such thing as a failed apology, then, only an abuse of power, because all forgiveness, Potts writes, “begins and ends in failure”: it does not, and cannot, redeem or undo pain and loss; it can only demand the necessary attention to pain and loss, as a reckoning, as an act of grief. Forgiveness is, therefore, a species of mourning, a form of sorrow.

Within the early Christian West, acts of public supplication—begging pardon—required confession and might require restitution, but not the scripted public apology in the sense the SorryWatchers want. The same distinction can be made within the history of Judaism. In the twelfth century, the Spanish-born Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, known as Maimonides, wrote a commentary on the Torah and the Talmud that included a section on teshuvah, or “repentance,” an extended reflection on the commandment that “the sinner should repent of his sin before God and confess.” But, as the Jewish historian Henry Abramson remarked in a recent study, “The Ways of Repentance,” Maimonides warned against public confession that “can also be an expression of personal arrogance: ‘Look how good I am at doing teshuvah! ’ ” Watch my apology video on YouTube!

In “On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World,” the rabbi Danya Ruttenberg translates Maimonides into a step-by-step guide for our world, for which she provides modern-day examples. The first step is “naming and owning harm” (one of her examples: “I finally understand how my decision to hold a writer’s retreat at a plantation sanitizes the horrors of slavery”); the second is “starting to change.” Step three: restitution. Step four: apology. Step five: making different choices. These are kindhearted ideas, and Ruttenberg’s book is full of hope and counsel about repair through restitution. But her prescriptions also come close to insisting on the suppression of dissent. She says that “starting to change,” for Maimonides, might have involved “tearful supplication,” but that “these days this process of change might also involve therapy, or rehab, or educating oneself rigorously on an issue about which one had been ignorant or held toxic opinions.”

“This book started on Twitter,” Ruttenberg writes, which is something of a tip-off. “Twitter gamifies communication,” the philosopher C. Thi Nguyen has argued; it’s custom-built to do things like score apologies, to drag users into a rating system that has nothing to do with morality. An unforgiving god rules Twitter, where the modern economy of apology runs something like this: If you express what I believe to be a toxic or ignorant opinion, you must apologize according to my rules for apology. If you do, I may forgive you. If you don’t, I will punish you, and damn you unto eternity.

The practice of establishing and enforcing strict requirements for public apology is not a human universal. It happens only here and there, and now and again. You see it in fiercely sectarian times and places—like twenty-first-century social media, or seventeenth-century New England.

Consider a case from October, 1665, when the Massachusetts legislature assembled in Boston to attend to a docket of ordinary affairs, a day in the life of a puritanical theocracy. It set the price of grain: wheat, five shillings a bushel; barley, four shillings sixpence; corn, three shillings. It addressed a petition filed by three Native men, including the Pennacook sachem Wanalancet, regarding an Englishman’s claim to an island on the Merrimack River. It warned one unhappy, estranged couple, Mr. and Mrs. William Tilley, that he must “provide for hir as his wife, … that shee submit hirselfe to him as she ought,” or else he would be fined and she would be imprisoned. In honor of God’s having graced the colony with abundant rain during the summer and mercifully diverted a fleet of Dutch ships from an invasion, the legislature appointed November 8th “to be kept in solemn thanksgiving,” but, because a plague was still raging in London, a sign of God’s wrath, it declared November 22nd “a solem day of humilliation.” And it condemned five men who had dared to practice a heretical religion, Baptism, at which announcement one colonist, Zeckaryah Roads, blurted out “that the Court had not to doe wth matters of religion.” He was detained as a result.

For the things they said—words whispered, grumbles muttered, prayers offered, curses shouted—dissenters, blasphemers, and nonconformists in seventeenth-century New England faced censure, arrest, flogging, the pillory, disenfranchisement, exile, and even execution. Quakers might have their ears cut off. For holding toxic opinions, one blasphemer was sentenced to have the letter B “cutt out of ridd cloth … sowed to her vper garment on her right arme.” Those who wished to avoid or mitigate these consequences might apologize in public. Mostly, apologies followed a script. The Six Steps to a Good Apology! Disappointing People Is My Central Trauma: How to Avoid the Eight Worst Apologies of 1665! Earlier that year, just months before Zeckaryah Roads dared to voice dissent, Major William Hathorne, of Salem—an ancestor of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s—issued a public apology for his own (now lost to history) error: “I freely confesse, that I spake many words rashly, foolishly, … unadvisedly, of wch I am ashamed, … repent me of them, … desire all that tooke offence to forgive me.” That did the trick. You went off script at your peril, as the historian Jane Kamensky demonstrated in her masterly book “Governing the Tongue” (1997). In the sixteen-forties, observers deemed Ann Hibbins’s apology—essentially, for being abrasive, and a woman—“very Leane, … thin, … poore, … sparinge.” It saved her neck, but not for long: in 1656, Hibbins was hanged to death as a witch. Still, there was one other option: after John Farnham refused to apologize for countenancing heresy, and was therefore banished, he said the day he was kicked out of the church “was the best day that ever dawned upon him.” I mean, fuck it, there was always Rhode Island.

Lately, online, you can find modern apologies ranked by the same standards once so punctiliously applied by Puritan divines. “I doe now in the presence of god … this reverand assemblage freely acknowledg my evell,” Henry Sewall confessed in a church near Ipswich in 1651, although, as he pointed out, he’d been forced to make that apology “as part of ye sentence” he’d been given by the Ipswich court. He squeaked by with that one, but just barely. Modern SorryWatchers might rate it Garrison Keillorian.

In 1665, for intimating that the government ought not to banish people for being Baptists, or kill them for being Quakers, Zeckaryah Roads did what he had to do, as chronicled in the meeting records, “acknowledging his fault, … declaring he was sorry he had given them any offence, …c.” Easy to say from here, of course, but I wish to hell he hadn’t.

The twenty-first-century culture of public apology has its origins in the best of intentions and the noblest of actions: people seeking collective justice without violence for terrible, unimaginable acts of brutality, monstrous wickedness, crimes against humanity itself. In the aftermath of the Second World War, churches and nation-states began issuing apologies for wartime atrocities and historical injustices. Some of the abiding principles that lie behind this postwar wave of collective apologies also found expression in “restorative justice”—individuals making amends to their victims, sometimes as an alternative to incarceration or other kinds of force and violence. The idea gained influence in the nineteen-seventies, when it intersected with the victims-rights movement, and its particular demands for apology as remedy. And you can easily see why. Prosecutors—for years, decades, centuries—had failed to act on allegations of sexual misconduct, had ignored or suppressed evidence of police brutality and predatory policing; in a thousand ways, the criminal-justice system had failed women and children, had failed the poor and people of color. For some, “restorative justice” held out the prospect of a better path. By the nineteen-nineties, schools and juvenile-justice systems had begun using restorative-justice methods, often requiring, of public-school students, public apologies. Meanwhile, in the United States, church membership was falling from around seventy-five per cent in 1945 to less than fifty per cent by 2020. In many quarters, public acts began taking the place of religious ritual, political ideologies replacing religious faith. The national public apology took on the gravity and solemnity of a secular sacrament: Ronald Reagan apologizing, in 1988, for the imprisonment of more than a hundred thousand Japanese Americans during the Second World War (and providing limited reparations); David Cameron apologizing, in 2010, for Bloody Sunday; or the Prime Ministers of Canada apologizing, in 2008 and 2017, for the practice of taking Indigenous children from their homes and confining them to schools where, maltreated, neglected, and abused, they suffered and died.

Apology came to play a role, too, in therapy, including family therapy, in twelve-step recovery programs, and in H.R. dispute-resolution procedures. Conventions that were established for heads of states and churches making public apologies to entire peoples against whom they had committed atrocities came to be applied to apologies from one individual to another, for everything from violent crime to petty insult. The person became the collective. Eve Ensler’s 2019 book, “The Apology,” in which she imagines the apology her father never offered for sexually abusing her, is dedicated to “every woman still waiting for an apology.” The particular injury became the universal harm. “We all cause harm,” Danya Ruttenberg writes in her book on repentance. “We have all been harmed.”

But the origins of the Twitter apology orgy lie elsewhere, too, and especially in the idea that many kinds of speech can be harm, a conviction central to the brand of feminism founded in the nineteen-nineties by the legal theorist Catharine MacKinnon. (Her book “Only Words” was published in 1993.) In 2004, in “On Apology,” Aaron Lazare tried to figure out when the number of public apologies began to explode. He counted and identified a rise in the number of newspaper articles about apologizing, beginning his analysis in the early nineteen-nineties and identifying a peak in 1997-98. He found this puzzling. But, historically, it makes sense: his chronology nicely lines up with Anita Hill’s testimony at the Clarence Thomas hearings, in 1991, and with the breaking of the Monica Lewinsky scandal, in 1998. Thomas maintained his innocence, and although Clinton went on television later that year and admitted to the relationship, many viewers found his apology inadequate. And neither man seemed sorry, either, except insofar as they both quite plainly felt very, very sorry for themselves.

The refusal of Thomas and Clinton to apologize for the ways in which they had harmed women took place on television. And the whole spectacle, with its scripted expectation of apology and contrition, drew its sensibility from television. In the nineteen-eighties and nineties, the stock soap-opera plotline—betrayal, hurt feelings, and misunderstanding followed by tearful apology, reconciliation, and reunion—became a hallmark of the daytime talk-show circuit. Oprah and Phil Donahue staged churchy apologies in front of studio audiences, choreographed for maximum emotional intensity, and advancing the idea that every possible political, economic, or social injustice, from child abuse to police brutality and employment discrimination, could be addressed by a two-shot, a few closeups, and Kleenex. Donahue mounted an especially perverse sorrywatching spectacle in 1993. The year before, after a jury acquitted four Los Angeles policemen who beat Rodney King and riots broke out in angry, anguished protest, a group of Black men pulled Reginald O. Denny, a white man, out of his truck and beat him nearly to death. Henry Keith Watson, charged with attempted murder, was found not guilty, and was convicted only of misdemeanor assault. After Watson got out of jail, Donahue brought Denny and Watson together in front of an almost entirely white audience for a two-part apology special. “Are you sorry?” Donahue asked Watson, again and again, as the audience grew tense and even tenser. “I apologize for my participation in the injuries you suffered,” Watson said to Denny. Then Watson eyed the audience: “Is everybody happy now?” Everybody was not.

Demanding public apologies on daytime television and deeming those apologies insufficient was an occasional thumb-wrestling match between two seven-year-olds sitting on a green vinyl school-bus seat on the ride to second grade compared with the daily, Roman Colosseum-style slaughtering that takes place online. It’s not that people don’t do and say terrible things for which they ought to atone. They do. Some of those things are crimes. Many are slights. Very many are utterly trivial. A few are almost unspeakably evil. But, on Twitter at its worst, all harm is equal, all apologies are spectacles, and hardly anyone is ever forgiven.

In 2017, at the height of the #MeToo movement, Matt Damon tried to rate harm. “You know, there’s a difference between, you know, patting someone on the butt and rape or child molestation, right?” he said in an interview on ABC News. “They shouldn’t be conflated, right?” At that, Minnie Driver tweeted her ire, and later told the Guardian, “How about: it’s all fucking wrong and it’s all bad, and until you start seeing it under one umbrella it’s not your job to compartmentalise or judge what is worse and what is not.” Damon apologized, and said that he’d learned to “close my mouth.”

In 1993, Phil Donahue seemed to think that, by asking Henry Keith Watson to apologize to Reginald Denny in that studio, he was bravely addressing the problem of racism in America. Twenty years from now, what’s been happening on Twitter will likely look exactly as grotesque and cruel and ineffective as that two-part, syndicated apology special. Will Donald Trump or anyone in his inner circle ever apologize for anything—for tearing toddlers from their parents’ arms, for inciting neo-Nazis, for grift, fraud, sedition? Never. Will responding to the gaffe of the day by demanding a six-step apology usher in an age of justice for all, or an end to iniquity? No. There’s a reason Puritanism did not prevail in America; it tends to backfire. In 2018, during an exchange on Twitter, the television writer Dan Harmon apologized for sexually harassing the writer Megan Ganz, and then made a heartfelt video, elaborating. “We’re living in a good time right now, because we’re not going to get away with it anymore,” he said, referring to sexual misconduct. And I hope that’s true. But very little evidence suggests that calling people out on Twitter, self-righteous indignation followed by cynical apology, is making the world a better place, and much suggests that the opposite is true, that Twitter’s pious mercilessness is generating nothing so much as a new and bitter remorselessness.

“I don’t give a fuck, ’cause Twitter’s not a real place,” Dave Chappelle said last fall, in his Netflix special “The Closer.” In June, on the Amazon Prime series “The Boys,” a made-for-television Captain America-style superhero named Homelander, who is secretly a villain, recited a rehearsed apology on television, only to unsay it later, in an unscripted outburst. “I’m not some weak-kneed fucking crybaby that goes around fucking apologizing all the time,” he said, seething. “I’m done. I am done apologizing.” Around the time the episode appeared, the actor who plays Homelander, Antony Starr, who was found guilty of assault and released on probation, told the Times, unabjectly, “You mess up. You own it. You learn from it.” No “I am listening,” no “I am going to rehab.” None of it. It was as if he got away with going off-script because his character already had. And Homelander won’t be the last to make that “I’m done” speech. “I’m done saying I’m sorry,” Alex Jones yelled in a courtroom in September during a trial to assess the money he’ll be required to pay the parents of very young children who were killed in a mass shooting, a shooting that Jones has for years insisted never happened, because those children, he told his audience, never existed. Jones has been found liable for defamation. Even the hundreds of millions of dollars in damages he was ordered to pay to the families whose despair he worsened, and on whose affliction he feasted, goes nowhere near far enough. And neither does any apology.

Twitter is blowing its top, some very angry people very loudly demanding apologies while other very angry people demand the denunciation of the people who are demanding apologies. Dangerously, but predictably, the split seems to have become partisan, as if to apologize were progressive, to forget conservative. The fracture widens and hardens—fanatic, schismatic, idiotic. But another way of thinking about what a culture of forced, performed remorse has wrought is not, or not only, that it has elevated wrath and loathing but that it has demeaned sorrow, grief, and consolation. No apology can cover that crime, nor mend that loss.

READ MORE Bernie Sanders. (photo: Antonella Crescimbeni)

Bernie Sanders. (photo: Antonella Crescimbeni)

The 2016 Democratic presidential primary may, finally, be over

This was Sen. Bernie Sanders’ (I-Vt.) scientific assessment of the 2022 midterms. He watched returns at home in Vermont — “I try to keep out of D.C. except when necessary,” he offers — and stayed up until four in the morning waiting for results. The night had been full of bright spots for the 81-year-old Democratic socialist, but the most promising had been John Fetterman’s decisive win in Pennsylvania’s U.S. Senate race. “There’s no candidate who ran who was more strongly identified with the working class of Pennsylvania than John Fetterman,” Sanders says. “He really hit a nerve that I hope we can all learn from.”

Fetterman’s candidacy had a Rorschach test quality to it, one that led most corners of the Democrats’ big tent to claim his win as their own. To Sanders, Fetterman’s victory validated the Vermont senator’s conviction that Democrats can win if they embrace a working-class oriented economic message. Sanders had set out on the campaign trail last month out of concerns that his party wasn’t doing enough to lift that message up.

But as he looked around at Democrats in the midterms’ final days, he saw a party that had, even in the smallest ways, taken up some sliver of his ambition. House progressives “had the best night ever” as a new slate of left-wing federal lawmakers won their races. Young people turned out to vote, shoring up Democratic victories in places where they were far from guaranteed. Even Sanders’ more centrist colleagues, like Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), had run on banning stock trades among members of Congress. Rep. Tim Ryan (D-Ohio), with whom Sanders has often clashed, “deserves credit as well” for keeping Ohio’s U.S. Senate race competitive on a workers-first platform.

There’s been a tendency, ever since Sanders’ dark horse 2016 presidential primary run, to view divides in the Democratic party through an ideological lens — one that makes it feel like the primary never really ended. Sanders himself remains far from satisfied with the state of the county or party: “Democrats have got to stand up for the working class,” he says when asked what the party should focus on over the next two years. But the Democrats who won on Tuesday night looked much more like champions of that vision than ever before.

“It’s hard to deny that in the last few weeks, from the president on down, more and more discussion about the economy,” Sanders shared in his post-election assessment. “And I’ll tell you, I think that had a very strong impact.

Sanders joined Rolling Stone to discuss election outcomes, the state of the party, and what he hopes Democrats will focus on as they retain control of the Senate.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Your chief concern heading into the midterm elections was that Democrats weren’t doing enough to talk about the economy — about the dangers Republicans posed to economic well-being and the agenda that Democrats should champion going forward. Do you feel like the party came around to stronger economic messaging in the final days of the campaign?

It’s hard to deny that in the last few weeks, from the president on down, more and more discussion about the economy, more and more discussion about Republican efforts to cut Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. And I’ll tell you, I think that had a very strong impact.

I think it’s fair to say — a lot of great campaigns out there, great people — but the marquee race was Pennsylvania. I know his stroke kind of distorted the whole campaign and changed focus onto his health, but there’s no candidate who ran who was more strongly identified with the working class of Pennsylvania than John Fetterman. And he ended up winning — despite his stroke, which raised so many questions — a very strong victory. I think, frankly, if he had not had that stroke and continued along after he won the primary, I would not have been surprised if he won by double digits. I don’t know if you listened to his victory speech on Election Night. He said, ‘I tried to get to every county in the state. I know, we didn’t turn every county blue, but I wanted to talk to working class people.’ And I think in that sense, he really hit a nerve that I hope we can all learn from.

Even in Ohio, Tim Ryan lost, but he got close to 47 percent of the vote and ran way ahead of where people thought he would be. He deserves credit as well.

So look, the issue of abortion, enormously important. Democrats appropriately took on an extreme right-wing Supreme Court. The issue of Trump’s threats to democracy — enormously important. We have to stand up for democracy and I think that was a very, very important factor in this election. But I think — when you are seeing working people falling further and further behind massive income and wealth inequality, massive homelessness, people can’t afford their rent, people can’t afford health care — it would be absurd to ignore the economy.

I’m glad you mentioned abortion, since exit polling seems to credit that issue with delivering the election for Democrats. But it sounds like you’re giving abortion and the economy credit.

Tens of millions of people vote and they all have their different main interests. For some people, abortion was the only issue. For some people, the economy was the only issue. For some people, defending American democracy or climate change was the only issue. But I think there is not one issue.

By the way, if you look at states like Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, Arizona, young people played a decisive role. I think Republican opposition to addressing the crisis of climate change played a role in that, as well as economic issues. So you know, any campaign has multiple issues, but abortion, very important, democracy, very important. And creating an economy that works for all, not just a few, also important. I think Fetterman would be the example of that.

During your run for president in 2016 and 2020, you argued that young people would eventually come out and support this kind of agenda — an agenda that focuses on working people, that speaks with authority about climate change, for example. I’m wondering if you’re feeling validated in that work from where you’re sitting right now.

Now, none of these things are exact science, but according to a number of exit polls, I’m just reading this right here, young people in Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, and Arizona supported Democrats by over 70 percent in those states. So the support among young people for Democrats was very high. Turnout was good, not as high as I would like. During my campaign blitz we worked with NextGen [America, a political organization focused on youth voter engagement. The reason for its existence is to get more young people voting and involved in the political process. So yeah, I think we did a good job on that.

What should your party’s priorities be for the next two years?

We must continue to protect a woman’s right to control her own body. We have got to do everything we can to defend American democracy. One of the other factors not talked about, I think, enough is the degree to which billionaire money impacted this election. It’s disgusting. As I mentioned, I was in Pittsburgh with Summer Lee. She had to run against millions of dollars of AIPAC super PAC money coming in the last couple of weeks, and she ended up beating it back. This is a major, major problem.

So when you’re looking at democracy, it’s not just Trump. It is the Citizens United Supreme Court decision, which has got to be dealt with. I think the last thing that I would say is, if you look at Biden’s popularity, its ups and its down, you will find that it was at its highest peak in I think March of 2021, when we passed the American Rescue Plan. Because they were hurting both from a health point of view, they were hurting from an economic point of view, they wanted their government to respond to their needs — we did it. And if you look at the provisions in Build Back Better, enormously popular.

So I think in the next few years, the Democrats have got to stand up for the working class in this country, which is being battered. Inflation is hurting people today. Working people are making less in real inflation adjusted dollars than they made 50 years ago. Can you believe it? I mean, unbelievable, despite the huge increase in worker productivity. So I think our focus has got to be to take on the greed of the one percent and the CEOs in the corporate world and create an economy that works for all, not just a few.

I don’t surprise you by saying that, right?

READ MORE A man on Sunday walks in the yard of a prison in Kherson, Ukraine, where he said Russian jailers killed prisoners for disobedience or for being suspected resistance fighters, known as partisans. (photo: Wojciech Grzedzinski/WP)

A man on Sunday walks in the yard of a prison in Kherson, Ukraine, where he said Russian jailers killed prisoners for disobedience or for being suspected resistance fighters, known as partisans. (photo: Wojciech Grzedzinski/WP)

Black sedans with tinted windows and missing license plates arrived at all hours, disgorging Ukrainian detainees with bags over their heads. Screams began to escape the three-story structure, piercing the once-calm neighborhood, residents said.

Sometimes, the gates would open, and a detainee would be dumped on the street, physically and mentally broken. Other captives were sent to a larger prison, or never seen again. “If there is a hell on Earth, it was here,” said Serhiy, 48, who lives across the street and whom The Washington Post is only identifying by first name to protect him from retribution.

Days after Russian forces fled in retreat, surrendering the only regional capital Russia had managed to seize since the start of its invasion, the horrors that occurred in this stately 18th-century port city are just starting to come into focus.

During a visit to the city on Monday, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said occupying Russian forces had committed “hundreds” of atrocities in the Kherson area, though he said the precise number was not yet known.

What is already apparent, however, is that the Russians here operated a detention system on a scale not seen in any of the dozens of other cities, towns and villages liberated by Ukrainian forces in recent weeks.

An outline of mass incarceration was already appearing on Saturday and Sunday, when a dozen people told The Post that they had either been detained themselves or were searching for someone who had been taken. Many approached reporters on the street, asking for help in finding their loved ones.

Some Kherson residents were arrested because they were accused of being freedom fighters. Others said locals were locked up because they had Ukrainian tattoos, wore traditional clothing, took selfies standing near Russian troops, or simply dared to say “Slava Ukraini” — Glory to Ukraine.

A mother was arrested in front of her teenage son and held for two months on a suspicion of helping Ukrainian forces.

A 64-year-old man was detained and beaten with a hammer for fighting — eight years ago.

A priest was arrested and sent to Crimea, according to a congregant. Even the mayor was arrested. Still, no one knows where he is.

“We’re talking about thousands of people,” said Oleksandr Samoylenko, head of the regional council of Kherson. “On any given day, the Russians had 600 people in their torture chambers.”

Samoylenko said it would take time to figure out how many people were detained, how many remain missing, and if mass graves, like those found in other liberated areas, would also be discovered here.

“A lot of people have disappeared,” Samoylenko said, adding that he feared the city’s name would soon join the ranks of cities such as Bucha, Irpin and Izyum, which are now synonymous with Russian atrocities.

“It was a nightmare,” he said.

‘Everyone could hear the torture’

What could set Kherson apart is the emerging scale of abuses.

Located where the Dnieper River meets the Black Sea, Kherson, with a prewar population of nearly 300,000, is by far the biggest city to be liberated. It was also the first to be occupied. Of cities that fell under Russian occupation, only Mariupol, which suffered severe destruction and remains under Russian control, is bigger.

And as a regional capital crucial to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s plan to annex the regions of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, Kherson city is a window into the Russian military- administrative machine.

Moscow-backed officials took over the regional administrative building downtown and began pumping out social media messages urging residents to obtain Russian passports to continue receiving their pensions and other benefits.

Some residents said officials offered cash payments — in Russian rubles — to get people to take a Russian passport. Schools were ordered to implement Russian curriculums, and Ukrainian nationalist songs were banned.

“Russia is here forever,” billboards vowed.

As the Russian forces fled last week, however, that administrative state collapsed. Moscow-backed officials moved their headquarters to the small town of Henichesk, a port city on the Sea of Azov, closer to illegally annexed Crimea.

The deputy head of the Kherson occupation administration, Kirill Stremousov, who had criticized Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu and other Russian military commanders over battlefield setbacks, died in a car accident last week on the same day that Shoigu approved the retreat from the city.

Even the pro-Russian billboards are now being torn down.

What remains, however, is the architecture of mass incarceration, and many missing people.

Most people who spoke to The Post said they or their loved ones were first taken to the drab concrete building in the north of the city.

Serhiy said he often saw Russians drag Ukrainian prisoners out of black sedans with bags on their heads and take them inside.

“Everyone could hear the torture, the screams, the shouts,” he said.

The building, a former youth detention center, was easy to adapt into a torture chamber. Most people who spent time in or around the place believed it was run by officers of the FSB, Russia’s feared Federal Security Service.

“The rooms were ready for them,” said a nearby neighbor, Ihor Nikitenko, 57.

“They brought everyone they could get their hands on: partisans, activists, you name it,” his wife, Larysa Nikitenko, 54, said as the couple shopped at a store next to the detention center.

Almost as often as prisoners arrived, others were thrown onto the street, confused, half-naked and often seriously injured, they said.

Oleksandr Kuzmin said he was held in the detention center for a day, during which people he suspected to be FSB agents smashed his leg with a hammer — all because he had fought against Russian-backed separatists in Donbas nearly a decade ago. In occupied towns, Russian forces routinely searched for men with prior military experience, often demanding that other residents identify them.

Kuzmin said that in a room below his cell, he could hear people screaming in pain, and he said a young man brought into his cell told him that he had been arrested for helping others access hryvnia, the Ukrainian currency, which Russia was trying to replace with the ruble.

The Russians had shocked the young men with electricity on his nipples and penis, Kuzmin said.

Prisoners were forced to say, “Hail Putin” or “Hail Russia” to receive meals, according to neighbors who had spoken to detainees after their release. Those who refused received electric shocks.

‘We wanted to kill them so badly’

While residents of the neighborhood could hear the torture inside, they said they could also see the Russians enjoying themselves. Russian men came into shops on the street to buy food and copious amounts of alcohol. They also brought in women who appeared to be prostitutes, several locals said.

“We wanted to kill them so badly but we had to smile to their faces because we knew that one wrong word could land us in there,” Serhiy said.

In a house just a few blocks away, Yuriy, 68, described how his son ended up in the detention center and is still being help captive in Crimea. The son, Roman, 38, had been part of a local territorial defense unit. When the Russians occupied Kherson in early March, his unit stayed and became resistance fighters, or partisans, smuggling weapons between safe houses and sometimes carrying out missions.

The Post is only identifying Yuriy and Roman by first name to avoid putting them at risk, or jeopardizing the son’s safe return.

For weeks, the Russians were looking for Roman. They finally caught him on Aug. 4 and took him to the detention center, where he was beaten for several days. After two or three weeks, Roman was transferred to a prison downtown — a fate that befell many of those accused of more-serious offenses.

At the prison downtown, inmates let Roman use a smuggled telephone to call his dad. For the next two months, Yuriy was able to leave painkillers, medicine, cigarettes and candy for his son at the larger detention center, though he was never allowed to see him.

He dealt with Ukrainian prison officials, he said, and filled out Ukrainian documents from the 1980s that were written in Russian. When he last spoke to his son on Oct. 20, there was no hint that anything was about to change. But a day or two later, Yuriy heard that many of the prisoners had been taken to Crimea.

After almost a month of searching, Yuriy said he finally learned Roman was alive and being held in Simferopol, the capital of Crimea. Yuriy said he has no idea what will happen to his son, who, as a resistance fighter, is facing serious charges. Even if his son is released, Yuriy said has no idea how Roman will return home.

“He has no documents, no passport, no nothing,” he said.

Others also told The Post they suspected friends or family members had been sent to Crimea as the Ukrainian armed forces advanced on Kherson city.

Some believed their loved ones might be much closer: just across the Dnieper River in the Russian-held town of Chaplynka. But others said they had no idea where to start looking.

Oleksandr Zubrytskiy approached reporters on the street outside the detention center to ask for help finding his best friend, Petro Pikovskiy. Pikovskiy, 62, had gone out looking for his son who had been arrested by the Russians, only to vanish himself, Zubrytskiy said.

‘Work for us or leave’

Serhiy Didenko, 42, was walking to join the celebration in Kherson’s main square on Sunday morning when he saw smoke rising from the large prison complex downtown where he used to work.

Didenko stepped over broken glass and followed inside after a team of soldiers who were clearing the building of mines and booby traps. Potatoes, presumably spilled by fleeing Russians a few days earlier, were strewn along the path into the building. Elsewhere inside, riot gear was scattered on the floor as if tossed aside in a hurry.

“I can’t express how I feel right now,” Didenko said, examining his office, from which the Russians had stolen a television, microwave, even an old sofa. Eventually, he summoned the words: “Pure anger.”

The Russians had arrived at the building on May 12, he said, and delivered an ultimatum: “Work for us or leave.” He chose the latter, and this was his first time back in the building.

The 700-person detention center had been half-full when he left, Didenko said. But it quickly filled with suspected partisans, activists or anyone bold enough to raise their voice to a Russian.

The new jailers put some of the prisoners to work building wooden structures for military trenches, according to two men who had been locked up since before the war began. Maksym Karynoi and Serhiy Tereshchenko, both 41, said they believed they were singled out because of their past military service fighting Russian separatists.

The Russians also introduced themselves to the inmates with terror, throwing hand grenades and randomly shooting inside the massive Soviet-built complex, according to three other inmates who were also already serving sentences when the prison was taken over.

“One person refused to get on his knees, so they shot him,” said Andriy, a rail-thin 35-year-old prisoner who asked that his last name not be used. “They left his dead body in the cell for 24 hours.”

Andriy and two other inmates told The Post that they believed the Russians had executed some of the suspected partisans.

“There would be one person on either side,” said another inmate, Vardan Maglochyan, 61. “They would drag them outside. Then we’d hear gunshots.”

They never saw those inmates again, they said.

The Post was unable to inspect the building where the inmates believed the men were killed because it was on fire and the roof was collapsing on Sunday. The fire could have been caused by Ukrainian demining teams detonating explosives the occupiers left behind. But the inmates had another explanation. They said they believed the Russians were destroying evidence.

Neighbors suspected something similar across town, at the detention center, where smoke began to pour from the upper floors on Friday night, just a few hours after the last Russians had left Kherson.

READ MORE Donald Trump. (photo: Erin Schaff/NYT/Redux)

Donald Trump. (photo: Erin Schaff/NYT/Redux)

Justice department filing claims former US president kept secret documents in drawer at Mar-a-Lago with other files from after his time in office

The former US president kept in the desk drawer of his office at the Mar-a-Lago property one document marked “secret” and one marked “confidential” alongside three communications from a book author, a religious leader and a pollster, dated after he departed the White House.

The mixed records could amount to evidence that Trump wilfully retained documents marked classified when he was no longer president as the justice department investigates unauthorised possession of national security materials, concealment of government records, and obstruction.

The classification status of the two documents is in dispute after Trump claimed that all documents at Mar-a-Lago had been declassified before he left office, though no such evidence has emerged and his lawyers have not repeated it in court.

New details about the commingled documents came in a eight-page filing submitted by the justice department on Saturday to Raymond Dearie, the special master examining whether the 103 documents seized by the FBI should be excluded from the evidence cache.

The justice department said towards the end of the filing: “Because plaintiff [Trump] can only have received the documents bearing classification markings in his capacity as president, the entire mixed document is a presidential record.”

The commingled records appear to have some significance to the criminal investigation, since the two classified documents were the only ones found in Trump’s office besides those contained in a leather-bound box and one additional document that the FBI seized during its search on 8 August.

The leather-bound box contained some of the most sensitive records found at Mar-a-Lago: seven documents marked “top secret”, 15 marked “secret”, two marked “confidential”, as well as 45 empty folders with “classified” banners and 28 folders marked “Return to Staff Secretary/Military Aide”.

Trump has attacked the investigation as a partisan effort designed to hurt him politically, as analysts speculate he will announce his 2024 campaign on Tuesday.

The Guardian identified the nature and location of the commingled documents at issue by comparing the unique identifier numbers with a spreadsheet filed by the justice department showing they were part of “Item #4” seized by the FBI, which is described in another filing as “Documents from Office”.

The documents investigation is expected to intensify in the coming weeks, with the midterm elections largely finished and federal investigators closing in on several key witnesses.

The justice department gained testimony last Friday from top Trump adviser Kash Patel about claims that all the documents seized from Mar-a-Lago were declassified, after he was forced to take limited immunity and appear before a federal grand jury in Washington.

It comes after federal investigators also obtained contradictory accounts from Walt Nauta, a former White House valet who followed Trump to Florida after his presidency, about removing boxes from a storage room at Mar-a-Lago that was used to keep some documents marked classified.

The justice department has also attempted in recent weeks to compel Trump to return more government documents that it believes to be in his possession, prompting some of Trump’s lawyers to discuss ideas such as having an outside firm certify that no more records remain, say people close to the matter.

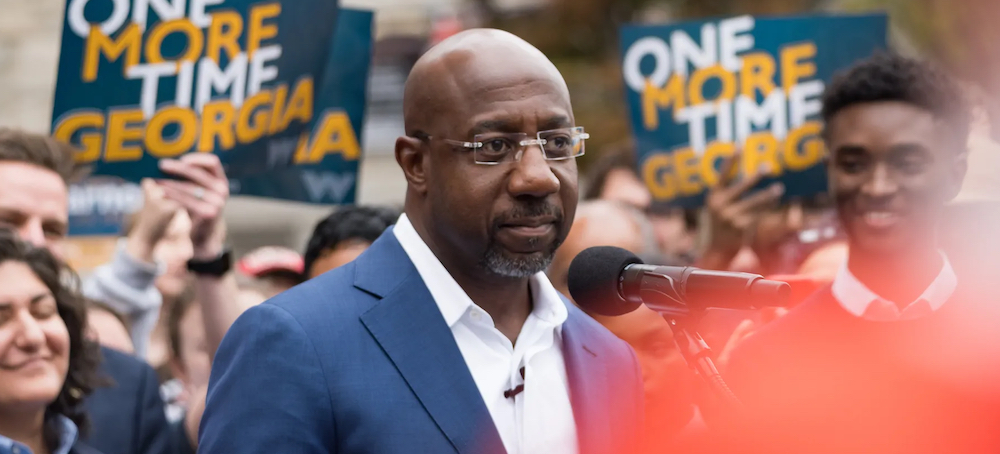

READ MORE Sen. Raphael Warnock speaks at a press conference on November 10 about his runoff campaign, in Atlanta, Georgia. (photo: Megan Varner/Getty Images)

Sen. Raphael Warnock speaks at a press conference on November 10 about his runoff campaign, in Atlanta, Georgia. (photo: Megan Varner/Getty Images)

A split Congress is likely, but a Warnock win would still benefit Democrats.

Typically, the midterm elections serve as a referendum on the party that holds the White House, with the president’s party losing seats in Congress if not necessarily ceding full control. In 2018, for example, Democrats swept the House of Representatives, picking up 40 seats in the House for the majority while Republicans gained two seats in the Senate to maintain their majority.

The typical result is that the president’s party loses Senate seats, which has happened in 13 of the last 19 midterm elections, as FiveThirtyEight reported Friday. But Democrats, if Warnock wins reelection in December, will have picked up a seat and flipped one as well in Pennsylvania, with John Fetterman replacing Sen. Pat Toomey (R), following his win over Mehmet Oz.

Although it’s not likely that Democrats will be able to push through aggressive, landmark legislation with such a slim majority — particularly if they end up losing the House, which looks likely as of this reporting — there will be some critical advantages to keeping it.

As Vox’s Li Zhou wrote Saturday, the split Congress does have its disadvantages but with a majority in the Senate, Democrats will be able to confirm federal court judges with a simple majority. That will provide an important counterweight to the raft of federal judges appointed by former President Donald Trump and confirmed by a Republican Senate. Supreme Court, federal district court, and circuit court judges enjoy lifetime appointments, and they have the ability to shape legal interpretation and policy for decades to come. With 116 vacancies — and 62 of those lacking nominations, Zhou wrote — Democrats can make plenty of impact over the next two years.

A Democratic majority in the Senate will also retain power over which bills come to the floor for discussion — meaning they can reject approved bills from a Republican-led House, Zhou wrote.

However, a GOP House can also do a fair bit of damage if it decide to conduct the investigations House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy has threatened or impeach President Joe Biden and other top officials. A split Congress also probably means bitter battles over issues like funding the government and raising the debt ceiling, Vox’s Rachel M. Cohen, Dylan Scott, and Li Zhou wrote earlier this month. Should Republicans win the House, as they seem poised to do, they wrote:

House Republicans are prepared to hold any increase to the debt ceiling hostage in exchange for cuts to other programs like clean energy investments and Social Security. In that case, the House and Senate could face an interminable standoff that could put the United States on the verge of defaulting on its debt, a scenario that could have devastating consequences for the economy.

Here’s why Georgia is still important to win

Those advantages will be amplified should Warnock win the runoff in December.

If Warnock keeps his seat, Democrats won’t have to depend on Vice President Kamala Harris to cast a tie-breaking vote, and they would have more leverage over Sens. Joe Manchin (WV) and Kyrsten Sinema (AZ), the more conservative members of the party, in order to get legislation passed.

Manchin and Sinema both put up guardrails to Biden’s signature legislation, the Build Back Better Act. That legislation, in a greatly reduced form, passed as the Inflation Reduction Act, with both senators’ vote; however, monumental parts of the legislation, like free universal pre-kindergarten, had to be abandoned.

There’s also more breathing room for Democrats if Warnock wins his race, should there be any vacancies or absences, as in January when Sen. Ben Ray Luján of New Mexico suffered a stroke ahead of the crucial vote to confirm Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court.

Democrats won’t be able to do everything they want — that means the filibuster will probably remain in place, and Biden’s promise to enshrine abortion protections into law probably won’t come to fruition in a divided Congress.

As Vox’s Andrew Prokop wrote, Democrats do have a path to a slim majority in the House, but it’s far from assured. As of this writing, Democrats have secured 204 seats in the House, while Republicans have secured 211; 218 seats are needed to win the majority.

But the likelier outcome is that Republicans take the House with a slim majority.

Here’s what Dems are doing to push Warnock over the edge, and here’s what the GOP is doing for Walker

Warnock, who took office in 2021, has already won a runoff for his Senate seat, as did Sen. Jon Ossoff, another Georgia Democrat. In his first runoff, against incumbent Republican Sen. Kelly Loeffler, Warnock won by 2 percentage points.

The end result of Tuesday’s contest showed Warnock slightly ahead of Walker, with 49.4 percent of the vote to Walker’s 48.5 percent. A Libertarian candidate, Chase Oliver, racked up 2.1 percent, ultimately preventing either major-party candidate from getting the majority.

Unlike many other states, Georgia requires a candidate to win 50 percent of the vote or face a runoff, a vestige of the South’s racist, segregationist past during the post-Civil War Reconstruction era. As Cal Jillson, a professor of political science at Southern Methodist University, explained to CNN in a Friday interview:

In several Southern states after the end of slavery and after Black men were allowed to vote, Black people were a majority of the electorate. There were some states where Black people were 40% or so of the electorate.

So, the White people who were in control of the legislatures used the runoff to ensure that if there were multiple candidates in the first election and a Black person ran first or even second, the White vote could consolidate in the runoff and defeat that Black candidate.

Now, two Black candidates will face off for the first time in a Georgia Senate runoff, and money is pouring into the runoff. The website Open Secrets, which tracks political fundraising and spending, noted that the Georgia Senate race was the second-most expensive federal race this cycle, second only to the Pennsylvania race between Fetterman and Oz.

Now, headed into a runoff in just four short weeks — as opposed to the nine weeks candidates had to fundraise, strategize, and get out the vote before Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp signed a law last year limiting the time period before a runoff election — funds are already pouring into the campaigns.

Warnock’s campaign is receiving funding and logistical support from grassroots efforts like the New Georgia Project, as well as the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC), which has already committed $7 million to fund ground operations, according to Politico.

“We know talking directly to voters through a strong, well-funded ground-game is critical to winning in Georgia, and we’re wasting no time in kick-starting these programs in the runoff,” DSCC head Sen. Gary Peters (D-MI) told Politico in a statement.

Organizing for Walker are conservative groups Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America and its affiliated PAC Women Speak Out, which will spend at least $1 million on Walker’s runoff campaign, in addition to the $1.1 million already spent. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s super PAC, the Senate Leadership Fund, will support Walker’s ground operations, to which Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp will contribute his data and canvassing infrastructure, according to the Washington Post.

In the midterm contest, Warnock benefited from split ticket voting, in which some voters chose popular Republican governor Kemp but declined to vote for Walker. Those votes were concentrated in metro areas, particularly Atlanta. Now that Kemp is no longer on the ballot, it remains to be seen whether his popularity will give Walker a boost.

Georgians can begin early voting on or before November 28, depending on when the general election results are certified.

Palestinians stand next to the car that was carrying 19-year-old Sanaa al-Tal, who was shot by Israeli forces, in the town of Beitunia, near the city of Ramallah in the occupied West Bank, on November 14, 2022. (photo: Abbas Momani/AFP)

Palestinians stand next to the car that was carrying 19-year-old Sanaa al-Tal, who was shot by Israeli forces, in the town of Beitunia, near the city of Ramallah in the occupied West Bank, on November 14, 2022. (photo: Abbas Momani/AFP)

Fulla Rasmi Abdelazeez Masalmeh, 15, was shot and killed by the Israeli army while in a vehicle near the town of Ramallah.

The Palestinian health ministry identified the victims as 15-year-old Fulla Rasmi Abdelazeez Masalmeh. “She was due to turn 16 on her birthday tomorrow. She was killed when occupation soldiers fired at her during a raid on Beitunia,” it said in a statement on Monday.

Palestinian officials initially wrongly identified the victim as a 19-year-old woman named Sanaa al-Tal.

According to the official Palestinian news agency Wafa, another Palestinian, 26-year-old Anas Hassouneh, was injured and arrested in the shooting.

Masalmeh, who was shot while she was in a car, hails from the town of al-Thahiriyeh south of Hebron city in the southern occupied West Bank.

News and images of the incident were circulated by local media at 4am (01:00 GMT), and her killing was confirmed several hours later.

A witness told Wafa, that Masalmeh and Hassouneh were in a vehicle driving up a road, unaware that Israeli forces had stationed themselves at several points until they were surprised by the army’s presence.

“When they tried to turn around, they found other soldiers opposite them who started shooting at them without any notice,” the witness, who lives in the area, said, adding that the car was shot at three times by soldiers stationed on different corners as it tried to get away.

The witness added that Israeli soldiers pulled Hassouneh, who was driving the car, out of the vehicle and that he was bleeding, while Masalmeh died at the scene.

An Israeli army statement said soldiers spotted a “suspicious vehicle accelerating towards them during an operation by security forces”, according to Israeli media. The forces signalled for the vehicle to stop, but it accelerated towards them, after which they fired at the vehicle, the statement said.

Surveillance video shared widely on social media appeared to show the car slowly pulling up in the area before being shot at by soldiers stationed nearby. Al Jazeera could not independently verify the footage.

Diaa Qurt, head of the Beitunia municipality, told Al Jazeera that the Israeli army had raided the town, which lies west of Ramallah, to carry out arrests, during which confrontations broke out.

“These youth were in the car… The army was suspicious of the car, and then shot at the car,” Qurt said. “For them to be killed in the blink of an eye is a crime.”

The Israeli army, Qurt said, handed over the girl’s body to Palestinian medics, who transferred her to Ramallah’s public hospital.

He noted that the army had detained three Palestinian men from Beitunia on Sunday night.

“As an occupied Palestinian people, the Israeli army has the power to shoot and kill our youth even if they are only throwing rocks during confrontations. They also shoot at mere passersby or people in their cars,” he said.

The Palestinian ministry of foreign affairs on Monday called for “international measures to force the occupying state to stop its aggression against our people”, in response to the killing.

It said the “latest victim of this aggression was the girl who was martyred this morning in Beitunia”.

Israeli forces carry out raids and arrests across the occupied West Bank on a near-daily basis, as part of an attempt to crack down on armed groups operating in the Palestinian territory.

The army regularly shoots live ammunition during such raids, often leading to the killing or injury of residents, including uninvolved individuals.

So far in 2022, the Israeli army has killed 197 Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and besieged Gaza Strip, including 43 children. According to the United Nations, the number of Palestinians killed by Israel in the occupied West Bank this year is the highest it has been in 16 years.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has noted in previous reports that Israeli forces “often use firearms against Palestinians on mere suspicion or as a precautionary measure, in violation of international standards”.

READ MORE Deforestation near Humaita, in Amazonas state, Brazil. (photo: Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Deforestation near Humaita, in Amazonas state, Brazil. (photo: Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

According to data published today by Brazil’s national space research agency INPE, deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon amounted to 904 square kilometers in October, raising the accumulated forest clearing through the first 10 months of the year to 9,494 square kilometers, the highest tally since Brazil implemented its current near-real-time tracking system in 2006. By comparison, at this time last year, accumulated deforestation stood at 7,887 square kilometers.

The figures came less than two weeks after Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva narrowly defeated Jair Bolsonaro in a run off election. Lula, who presided over a sharp drop in Amazon forest deforestation during his terms in office between 2003 and 2010, made saving the Amazon a key part of his bid for the presidency in contrast to Bolsonaro, whose administration has dismantled the infrastructure that underpins conservation in the Amazon.

Deforestation in the Amazon has surged under Bolsonaro, last year reaching the highest level in 15 years.

Numerous scientific reports have warned that the Amazon is approaching a tipping point where deforestation and the impact of climate change will drive vast areas of rainforest to transition to a drier savanna-like ecosystem. Such a shift would release billions of tons of carbon through tree death and increases in fires, while diminishing rainfall across large swathes of South America and negatively impacting the region’s forest-depedent people and wildlife.

This article was originally published on Mongabay.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.