Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

But on the night of Oct. 15, massive fires tore through Evin, killing at least eight people and injuring 61, according to state media. Families of prisoners fear the true toll is much higher.

The disaster coincided with demonstrations that have swept across Iran over the past month and a brutal crackdown by the country’s security forces, who have killed dozens of protesters and arrested thousands more. Some of those detained have been taken to Evin, where rights groups have documented a long history of torture and other abuses.

Extraordinary videos from the night of the fire show people shouting, “Death to the dictator” and “Death to Khamenei,” a reference to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and a rallying cry of demonstrators, as shots are fired and flames rise above the prison.

To understand what happened that night, The Washington Post analyzed dozens of photos and videos, spoke to activists, lawyers, former prisoners and families of current prisoners, and consulted with experts in arson, weapons and audio forensics.

The findings are damning: At least one fire that night appears to have been started intentionally at a time when prisoners are locked in their cells. The most deadly fire erupted near the scene of the arson. As prisoners tried to flee the fire, guards and other security forces assaulted them with batons, live ammunition, metal pellets and explosives.

The fires

The unrest started that Saturday about 8:45 p.m., according to a video posted by Mizan, the news site of Iran’s judiciary. The video claims that a fight broke out in Ward 7 and that prisoners then set fire to a nearby textiles workshop.

Satellite imagery analyzed by The Post does, indeed, show extensive damage to the roof of the two-story building in the center of the prison that houses the textiles workshop, as well as a religious hall called a hussainiya on the level below.

That was not the only fire in the prison that night, however, and it was probably not the first.

Before any flames were visible from the outside of the textiles workshop, videos show at least three individuals throwing flammable liquid onto a fire atop an adjacent building in Ward 7, according to Phillip Fouts, a certified fire investigator. The fire on the roof probably didn’t catch, he said, because of a lack of combustible material. Satellite imagery taken in the aftermath shows only minimal damage.

Yet visuals show another fire blazing high into the air inside the grounds of Ward 7, close to where the arsonists had previously fed the flames on the rooftop. This second fire appeared to originate by the entrance to Ward 7, near a guard station, according to a former inmate who spent several years inside Evin. He spoke to The Post on the condition of anonymity, fearing backlash from the government.

The Post cannot confirm how the fire inside Ward 7 started, but its proximity to the intentional fire is telling. And it is the fire inside Ward 7 — which the government later blamed on prisoners without providing evidence — that offered a pretext for the chaotic and deadly crackdown on inmates that followed.

The gates to the wards were locked at 5 p.m. each night after roll call, according to the former prisoner. Families of current prisoners say their movements have been further restricted since the protests broke out last month. This makes it unlikely that inmates could have accessed any of the three areas where the fires broke out.

Amnesty International has reported that the sounds of gunshots and screaming in Ward 7 could be heard by prisoners in neighboring wards as early as 8 p.m., well before the first flames were visible, and that “authorities sought to justify their bloody crackdown on prisoners under the guise of battling the fire.” Iranian state television later said that security forces were responding to a “premeditated” escape plan by prisoners.

“This was a strange incident that happened at a time that the prisoners should be sleeping,” said Saleh Nikbakht, a lawyer who has several clients in Evin, speaking to The Post by phone from Tehran. “This was a big event.”

Ward 7 houses thieves and financial criminals, according to the government, though the former inmate told The Post that more violent criminals were also held there. Just as importantly, it borders Ward 8, where dissidents and political prisoners are held, and where the smoke from the fire eventually spread.

A deadly crackdown

As noxious smoke poured from Ward 7 into Ward 8, labor rights activist Arash Johari began to cough and gag, he told his family.

Johari, 30, said he and the rest of the prisoners in Ward 8 faced a stark choice: smash through the gates or suffocate. As they burst through the locked doors and spilled into the prison yard they were met by enraged guards, who brutalized them with batons, bullets and tear gas, according to family members who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of repercussions from authorities.

Steven Beck, an audio forensics expert, and researchers at Carnegie Mellon University separately analyzed videos provided by The Post and found that more than 100 distinct gunshots were fired. Both analyses identified automatic gunfire “consistent with an AK-47” as well as sounds that were likely to have come from handguns and rifles.

Mohammad Khani, a dissident in Ward 8, was blasted in the chest with metal pellets and took a bullet in his side, according to a family member, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Beck determined there were also at least two explosions “consistent with grenades.” Amael Kotlarski, a senior analyst and weapons experts from Janes, the intelligence defense provider, examined footage and audio provided by The Post and concluded stun grenades were probably launched into the prison, “judging by the flash and audible blast” heard in the video.

“[Johari] said he had been beaten in the head with a baton and that he was dizzy and felt nauseous,” said his family member. “He also said he had blurred vision and his head was bleeding.”

The experiences of Khani and Johari that night could not be independently verified by The Post, but they were consistent with the findings of Amnesty, as well as with past investigations by The Post documenting the use of excessive force against protesters in Iran.

Reinforcements were dispatched to Evin to deal with the unrest, including “security forces, judicial forces, the Basij and special police units,” prison official Heshmatollah Hayat Al Ghaib said in the judiciary video. The Basij is a paramilitary branch of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and has taken a leading role in the violent suppression of demonstrators.

The fire at Evin had been put out and the unrest was brought under control shortly before midnight, according to the government, though people who have family and friends living around the prison told The Post that gunfire could still be heard as late as 2 a.m. Sunday.

Three buses full of prisoners from Ward 8, including Johari, were sent from Evin to Rajai Shahr prison, about 40 miles west, according to Johari’s family member. The judiciary video shows these buses being escorted by police cars with flashing red lights.

Johari was promised an X-ray for his head injuries at Rajai Shahr but authorities did not follow through, his family said.

Khani contacted his family Sunday to tell them he had been badly wounded. His relatives fought for him to get outside medical care and prison authorities eventually relented, taking him to a nearby hospital.

The bullet in Khani’s side was approximately two fingers deep inside his body and required surgery, his family member said, alleging that the doctors did not stitch his wound up properly or give him antibiotics before sending him back to Evin. He can only walk now with the aid of other political prisoners in Ward 8, they said.

Dozens of other families flocked to Evin on Sunday morning to get news of their loved ones. They were turned away by soldiers until a large crowd had formed and began beating on the gate, demanding answers. Many mothers, thinking their children were dead, wailed with grief.

“When families went up as a group to ask questions [the guards] insisted that people come up one-by-one or else guards would be called to beat them,” said Johari’s relative, who talked to families at the prison that day. “All they kept saying is ‘Go home and we’ll contact you.’”

Farther away, other families were gripped by a similar fear. Among those held at Evin are Siamak Namazi and Emad Sharghi, two Iranian American business executives.

When the unrest broke out Saturday night, Namazi was moved from Ward 4 to Ward 2A, which is run by the IRGC, according to his brother Babak. Namazi could hear the gunfire and smell the smoke during the unrest, his brother told The Post in a telephone interview from Dubai.

“It’s important for President Biden to see how close we came. It could have been Siamak and Emad who got killed,” said Babak. “It shows the literal urgency and the life-threatening situation that they’re in.”

Russian Commander Alexander Chaiko unleashed a pattern of violence that left hundreds of civilians beaten, tortured and executed in territory under his command. (photo: AP)

Russian Commander Alexander Chaiko unleashed a pattern of violence that left hundreds of civilians beaten, tortured and executed in territory under his command. (photo: AP)

Soldiers providing security peered from behind fences, their guns bristling in every direction. Two Ka-52 Alligator attack helicopters circled overhead, providing additional cover for Col. Gen. Alexander Chaiko as he escorted an aid convoy in March from the schoolhouse on Tsentralna street that Russian officers commandeered as a headquarters.

Fifteen minutes away, in the village of Ozera, the lives of three men were about to take a dramatic turn for the worse. While Chaiko was directing Russia’s attack on Kyiv from Zdvyzhivka, the men were brought to the village by Russian troops, who interrogated and tortured them and then shot them in the garden of a large house about a kilometer (less than a mile) from where the general now stood.

The deaths of these men were part of a pattern of violence that left hundreds of civilians beaten, tortured and executed in territory under Chaiko’s command.

This wasn’t the work of rogue soldiers, an investigation by The Associated Press and the PBS series “Frontline” shows. It was strategic and organized brutality, perpetrated in areas that were under tight Russian control where military officers — including Chaiko himself — were present.

War crimes prosecutors in Ukraine are trying to gather evidence against Chaiko, who earned a global reputation for brutality as leader of Russia’s forces in Syria. And international human rights lawyers said evidence gathered by AP and “Frontline” was enough to merit an investigation of Chaiko at the International Criminal Court.

___

This story is part of an AP/FRONTLINE investigation that includes the War Crimes Watch Ukraine interactive experience and the documentary “Putin’s Attack on Ukraine: Documenting War Crimes,” on PBS.

___

‘WE DO NOT TAKE PRISONERS’

The map seized by Ukrainian forces is almost as tall as a man. It’s frayed, creased and deeply outdated — describing towns as they no longer exist. A single red line snakes down from Belarus, along the western flank of the Dnieper River, through Chernobyl and toward Zhuliany airport, in Kyiv.

On the back are a scrawled date — Feb. 22, 2022 — and the stamp of a Russian military unit — No. 07264, Russia’s 76th Guards Airborne Assault Division.

At 7 a.m. on Feb. 24, the commander of that division, Maj. Gen. Sergei Chubarykin, ordered his troops to cross into Ukraine from Belarus and fight their way to Kyiv, Ukrainian prosecutors say. Chubarykin reported to Chaiko during the initial phase of the war, two Ukrainian officials told the AP and Frontline.

Boy soldiers — some not much bigger than their guns — perched on top of their tanks, shouting: “Now we will take Kyiv! Kyiv is ours!” witnesses said.

The troops moving toward the capitol had been ordered to block and destroy “nationalist resistance,” according to the Royal United Services Institute, a London think tank that has reviewed copies of Russia’s battle plans. Soldiers used lists compiled by Russian intelligence and conducted “zachistki” — cleansing operations — sweeping neighborhoods to identify and neutralize anyone who might pose a threat.

“Those orders were written at Chaiko’s level. So he would have seen them and signed up for them,” said Jack Watling, a senior research fellow at RUSI who shared the battle plans with the AP.

While there is nothing necessarily illegal about that order, it was often implemented with flagrant disregard for the laws of war as Russian troops seized territories across Ukraine.

Witnesses and survivors in Bucha, as well as Ozera, Babyntsi and Zdvyzhivka — all areas under Chaiko’s command — told the AP and “Frontline” that Russian soldiers tortured and killed people on the slightest suspicion they might be helping the Ukrainian military. Sweeps intensified after Russian positions were hit with precision, interviews and video show, and soldiers, in intercepted phone calls obtained by the AP, told their loved ones that they’d been ordered to take a no-mercy approach to suspected informants.

Soldiers told their mothers, wives and friends back in Russia that they had killed people simply for being out on the street when “real” civilians would have been in the basement, calls the Ukrainian government intercepted near Kyiv show.

On March 21, a soldier named Vadim called his mother: “We have the order to take phones from everyone and those who resist — in short — to hell with the f------.”

“We have the order: It does not matter whether they’re civilians or not. Kill everyone.”

The slightest movement of a curtain in a window — a possible sign of a spotter or a gunman — justified slamming an apartment block with lethal artillery. Ukrainians who confessed to passing along Russian troop coordinates were summarily executed, including teenagers, soldiers said.

“We have the order not to take prisoners of war but to shoot them all dead directly,” a soldier nicknamed Lyonya said in a March 14 phone call.

“There was a boy, 18 years old, taken prisoner. First, they shot through his leg with a machine gun, then he got his ears cut off. He admitted to everything and was shot dead,” Lyonya told his mom. “We do not take prisoners. Meaning, we don’t leave anyone alive.”

The Dossier Center, a London-based investigative group funded by Russian opposition figure Mikhail Khodorkovsky, verified the identity of the soldiers who made those calls by cross-referencing Russian phone numbers, linked social media accounts, public reporting and information in leaked Russian databases.

‘THAT’S WHERE PEOPLE WERE KILLED’

Fierce Ukrainian resistance and poor planning pushed Russian troops off their planned line of attack. Some of them ended up in Bucha, where Ukrainian prosecutors say the 76th Guards Airborne Assault Division participated in a lethal cleansing operation on March 4 along Yablunska street, the deadliest road in occupied Bucha and the site of an important Russian command center.

Others settled with thousands of other troops in Zdvyzhivka, a tiny village half an hour north of Bucha that became a major forward operating base for the assault on the capitol, according to Ukrainian military intelligence and audio intercepts obtained by AP.

Russian troops dug into the woods around Zdvyzhivka, building virtual cities that stretched for several kilometers beneath the tall pines and poplar trees. They left gaping trenches sized for tanks, semi-permanent bunkers reinforced with logs and sandbags, rough-hewn tables and benches. There was even a field sauna, photographs and intercepts show.

The Russians set up their most sensitive infrastructure along Tsentralna street, the main north-south artery in town. They took over the village council building, a cultural center and a school and set up headquarters in the large white kindergarten. At the main intersection, near the pond, Russians turned a Baptist church into a field hospital, took over a forestry administration building and commandeered a large ostrich farm for their vehicles and supplies. In the fields behind the church, locals watched helicopters ferry in supplies and evacuate the wounded.

Checkpoints faced in every direction. It was so difficult to cross the checkpoint going south on Tsentralna that locals tried to bypass it, wending their way along a footpath that skirted the pond instead. One woman told AP she tried three times before she was allowed to pass and get back to her own home.

Tania, who was afraid to give her last name, lives on this southern stretch of Tsentralna street. She stayed in Zdvyzhivka with her children during the occupation, hemmed in by Russian checkpoints on both sides.

It seemed like tanks were parked in every yard, Tania said. Troops took over dozens of abandoned homes.

There is one house on Tania’s stretch of Tsentralna, between the checkpoints, that stands out. It is the biggest, ritziest compound around. Beyond its high brick wall, an elegant circular driveway leads to a large pinkish house. A stone path winds through the back garden, an oasis of fenced-in green with manicured hedges, thick trees, two gazebos, a basketball court, banks of garden planters. At the far back fence, a small door opens onto the woods beyond.

The soldiers who came and went from that compound were older, professional, spoke like educated men, Tania and other neighbors said. They had cars with drivers. They told people what to do. Everyone figured they were officers.

“That’s where people were killed,” Tania said, squinting down the street and pointing to the compound.

WHAT THEY FOUND IN THE GARDEN

Life under the occupation of Chaiko’s forces was tense and terrifying, local residents told AP and Frontline.

Andrii Shkoliar lives on Tsentralna street with his extended family, a few houses down from the luxurious compound. On March 18, Shkoliar and his wife were walking nearby to a relative’s house when a dark-colored UAZ Patriot sped past, stopped abruptly and drove back to them.

A tall, blond soldier with a beard who appeared to be of higher rank stepped out of the Russian-made SUV, demanding to know why they’d broken curfew.

“I give you one hour to go and come back or you’ll be like this one in the car,” the Russian told him.

Shkoliar peered through the back window of the SUV at a man slumped against the window, eyes bound with tape, his hands behind his back.

On their way back, Shkoliar and his wife saw the same UAZ Patriot parked in front of the officers’ compound.

The next day, March 19, Ukrainians launched a precision strike, knocking out a Russian storehouse at the ostrich farm on Tsentralna, according to village head Raisa Kozyr. Russian troops sprang into action, searching door to door and checking documents.

The same blond officer and driver of the UAZ Patriot, along with a third man, appeared at Shkoliar’s front door and pulled everyone out of the house to search for weapons. They said they’d kill everyone if they found anything.

“We were saying goodbye to our lives,” Shkoliar recalled. “What else could we do?”

The sweeps consumed the whole village.

Vitalii Chernysh was picked up that afternoon as he rode his bike through a field. Chernysh said soldiers found a photo of Russian military vehicles someone had sent him on the messaging app Viber on Feb. 25 and hauled him off with three other people, bound and blindfolded, to a nearby barn. It was below freezing, and none of the prisoners was dressed for the cold.

As night deepened, they chatted with the Russian guarding them. “He said more captured people were brought over,” Chernysh recalled. “From Bucha, from Ozera, from Blystavytsia and somewhere else. ... In short, they gathered people.”

The next day, Chernysh was taken, blindfolded, to a field and accused of being a spotter.

“Where are the nationalists?” the soldiers demanded. They poured gasoline on him and pretended to set him on fire. They ordered him to run through what they said was a minefield. Still blindfolded, Chernysh struggled to his feet and tried to follow the soldiers’ commands: “Go right. Go straight. Go faster.” Then they beat his legs again, with what felt like a wooden plank.

Chernysh began to wish they’d just kill him.

Finally, a man Chernysh thought was of higher rank came over, examined his phone and told the soldiers to take Chernysh home.

Photos taken shortly after his ordeal show large, livid bruises on the back of his swollen legs. Days later, Russia’s Ministry of Defense released a video of Chaiko pinning medals on soldiers near Zdvyzhivka.

“All units, all divisions are acting the way they were taught,” he said in the March 24 video. “They are doing everything right. I am proud of them.”

When Russian forces retreated a week later, the bodies began to surface.

Bucha, a pleasant town outside Kyiv, quickly became a global symbol of Russia’s wartime atrocities and case No. 1 for Ukrainian war crimes prosecutors. Retreating soldiers left behind the bodies of over 450 men, women and children — almost all bore signs of violent death.

But the slaughter wasn’t limited to Bucha. It was repeated in town after town, village after village. Including in Zdvyzhivka.

“We didn’t know what was happening around us,” said Kozyr, the village head. “What was happening in the woods. And we knew people were missing.”

On March 30, Yevhen Pohranychnyi went to the luxurious home Russian officers had used. Now that they were gone, he wanted to check on his neighbor’s cat and see how badly the house had been looted.

The house was trashed, photographs show. Drawers had been ripped from desks and dressers. Clothes, books and papers were strewn all over the floor. What the Russians hadn’t stolen, they’d smashed.

Pohranychnyi made his way out the back, to the far end of the long garden. There, as night was falling, he found something far worse: the bodies of two men — one with a crushed skull curled up like a child, his joints at strange angles; the other with red marks around his neck, who had bled out from his head and face onto a pink cloth.

The next morning, he brought the village head, the village priest and others to the site. Three more bodies had appeared overnight. The blood was fresh. Some of them had their eyes and hands bound. Two seemed to be dressed in clothes that weren’t their own.

Three of those men — Mykola “Kolia” Moroz, Andrii Voznenko and Mykhailo Honchar — were picked up from nearby Ozera between March 15 and March 22 on suspicion of acting as spotters for the Ukrainian military, eyewitnesses told AP and “Frontline.” Moroz was captured the day after a precision strike on a Russian position hidden in the woods outside Ozera, a drone video analyzed by the Center for Information Resilience, a London-based nonprofit that specializes in digital investigations, shows.

AP and “Frontline” visited that garden in July and found bullet casings and a zip tie on the ground and bullet holes in the fence where the men were found — indications that they had been killed on the premises of the house frequented by Russian officers in one of the most tightly guarded sections of Zdvyzhivka in late March.

All told, 17 people have been found dead in Zdvyzhivka — a village of 1,000 before the war.

CHAIKO IN CHARGE

Chaiko has been sanctioned by the U.K. for his actions in Syria and Human Rights Watch says Chaiko may bear command responsibility for widespread attacks on hospitals and schools and the use of indiscriminate weapons in populated areas during a notorious campaign in Idlib province in 2019 and 2020. At least 1,600 civilians were killed; some 1.4 million were displaced, according to the group.

In Ukraine, prosecutors say they don’t have proof Chaiko ordered specific crimes, but it is clear that atrocities were committed under his watch.

In June, the U.S. State Department sanctioned Russia’s 76th Guards Airborne Assault Division and its 234th Guards Airborne Assault Regiment, as well as the 64th Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade, for atrocities in Bucha.

Those units were all under the ultimate command of Chaiko, Ukrainian authorities told AP.

But Chaiko’s responsibility extended beyond Bucha.

To try to understand who might have been involved in the deaths of the men from Ozera, the AP obtained data about their cell phone activity from the Ukrainian government. On March 21, the day Russian soldiers captured Voznenko, his cell phone pinged the same cell tower as 40 Russian phone numbers — an indication of who was nearby when he was abducted.

The Dossier Center found explicit references to specific Russian military units in recent work history databases for 14 of those phone numbers. Nine came from units Ukrainian authorities told the AP were under Chaiko’s command. The formal wartime command structures for the rest are unclear, but four are from unit 62295, an airborne regiment based in Ivanovo, northeast of Moscow. That unit was in Ozera, along Chaiko’s front in the war, according to Russian phone numbers left behind on scraps of paper in Ozera that the Dossier Center traced to specific soldiers.

Days before the bodies of Voznenko and the others were found mutilated in the garden in Zdvyzhivka, two eyewitnesses spotted Chaiko again, about a kilometer (less than a mile) down the road at his headquarters in the village.

Both men independently identified him as Chaiko when AP and “Frontline” showed them a photograph of the colonel general in July.

“It’s him,” said Mykola Skrynnyk, 58, who served in the Soviet army in the 1980s, and says he exchanged a few words with the general. “Now I understand why there was so much security.”

“When you look at everything that was happening in Zdvyzhivka, it becomes evident that this is not just a singular case, this is their policy for the territory they capture,” said Taras Semkiv, a war crimes prosecutor in the office of Ukraine’s prosecutor general.

As top commander, Chaiko obviously “would have to be aware of what was happening near his headquarters located in the same village,” he said. “It’s only logical.”

But, he added, “This has to be proven. And I think we will do it.”

There’s no concept of command responsibility in Ukrainian law, but if prosecutors can demonstrate that Chaiko played a key role in implementing illegal policies of the Russian Federation, or should have known what his troops were doing and was in a position to stop, or punish, their behavior, he could be charged for war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide in an international court.

Toby Cadman, an international human rights lawyer in London who is working to hold Russia legally accountable for atrocities in Syria, said the evidence AP and “Frontline” collected was enough to merit an investigation of Chaiko at the International Criminal Court.

“Significant events like this can then fall through the cracks, they don’t get properly investigated,” he said. “A case file could be taken to the ICC, because half the job is done.”

“It is a significant case. It is a strategically important area. It is a strategically important individual,” he said. “Everything about it makes it a significant matter to look at,” he said.

The ICC declined to comment, citing confidentiality.

NEVER AGAIN?

While they seek more specific evidence, Ukrainian prosecutors have indicted Chaiko for the crime of aggression, a broad charge that seeks to hold him responsible for helping to plan and execute an illegal war in Ukraine.

They say he was in Zdvyzhivka from March 20 until March 31, directing the assault on Kyiv — that is, at the same time the three men from Ozera were killed and Chernysh was tortured.

Chaiko’s trial is expected to begin soon in Ukraine. But the dock will almost certainly be empty.

The International Criminal Court has a better chance than Ukraine of extraditing, or capturing, Chaiko one day. It is currently the only international forum that can hold leaders criminally responsible for wartime atrocities. But it is not a simple task.

The ICC doesn’t have jurisdiction over Russians for the broad crime of aggression because Russia — like the U.S. — never agreed to give it authority to do so. Instead, prosecutors must link commanders with specific crimes.

That makes it hard to build cases against leaders like Chaiko — and Vladimir Putin.

A growing number of people are calling for the creation of a special tribunal for the crime of aggression in Ukraine — similar to those set up for conflicts in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia — to address this gap in international law. They say it would be the best way to make Putin pay.

“The crime of aggression is called the mother of all crimes,” Ukraine’s foreign minister, Dmytro Kuleba, told the AP and Frontline. “You don’t have war crimes if you don’t have the crime of aggression. So the best way to prosecute personally President Putin is to have a special ad hoc tribunal for the crime of aggression.”

It’s not clear whether Kuleba and his allies will succeed. They face political opposition from powerful nations who don’t want to see their own leaders in the dock and from the chief prosecutor of the ICC, Karim Khan, who said his court can handle prosecutions on its own.

“We have clear jurisdiction,” he said in an interview in July. “Victims don’t have much tolerance in my view for vanity projects or distractions.”

The Kremlin did not respond to AP’s requests for comment.

But there is no sign Moscow has sanctioned Chaiko for the very public atrocities committed on his watch. Instead, Putin praised Chaiko for his actions in Syria, awarding him the title “Hero of Russia” in 2020 and promoting him to colonel general in June 2021.

Cadman, the international human rights lawyer in London, watched with dismay as Russian atrocities in Syria — under the leadership of some of the same men, including Chaiko — went unanswered.

“If we do not act decisively now,” he said, “it will not end in Ukraine.”

An image reportedly posted to social media on Wednesday shows an unveiled woman standing on top of a vehicle as thousands make their way toward Aichi cemetery in Saqez, Mahsa Amini's home town in the western Iranian province of Kurdistan, to mark 40 days since her death. (photo: AFP)

An image reportedly posted to social media on Wednesday shows an unveiled woman standing on top of a vehicle as thousands make their way toward Aichi cemetery in Saqez, Mahsa Amini's home town in the western Iranian province of Kurdistan, to mark 40 days since her death. (photo: AFP)

Teargas also used against protesters gathered in home town of 22-year-old Kurdish woman, says rights group

“Security forces have shot teargas and opened fire on people in Zindan Square, Saqqez city,” Hengaw, a Norway-based group that monitors rights violations in Iran’s Kurdish regions, tweeted without specifying whether there were any dead or wounded. It said more than 50 civilians were injured by direct fire in cities across the region.

Witnesses confirmed shots were fired, while the Iranian government said security forces had been forced to respond to riots. Iran later tried to block internet access in the region.

The 40th day after a death traditionally marks the end of mourning, and appeals had gone out for protesters to take to the streets, a call that was answered in Tehran, Isfahan and Mashhad. Reports of teargas being fired in Iran were backed by video evidence.

Despite a ban by the security forces, the biggest gathering was in Amini’s home town of Saqqez in the western Kurdistan province. Amini died on 16 September, three days after she was arrested by the morality police for being dressed inappropriately. An official inquiry said she collapsed due to a pre-existing condition, an explanation rejected by Amini’s family, who have been prevented from choosing any doctors on the medical examination panel.

Her death sparked unexpected protests involving many students and schoolgirls, removing and burning their headscarves and confronting security forces on the street.

Mourners headed to Amini’s gravesite on Wednesday morning even though the security services had warned her family not to hold the ceremony, threatening that “they should worry for their son’s life”, according to activists. As many as 10,000 mourners attended, arriving on foot as well as in cars and on motorcycles.

“Death to the dictator,” mourners chanted at the Aichi cemetery outside Saqqez, before many were seen heading to the governor’s office in the city centre. Iran’s Fars news agency said about 2,000 people gathered in Saqqez city and chanted “woman, life, freedom”.

Images shared by Hengaw showed the heavy presence of security forces overnight in Saqqez. They had reportedly shut entrances to the city and closed roads leading to Aichi cemetery and Amini’s graveside.

In one video the group chant: “Kurdistan, Kurdistan, the graveyard of fascists.” But they also address claims that the protests are part of a Kurdish separatist movement by saying there is solidarity in Tehran and Kurdistan.

The shootings appear to have happened when a smaller group marched to the governor’s office in Saqqez.

The protests extended far beyond Iranian Kurdistan to many cities around the country, with one group of students at Amirkabir University in Tehran chanting at the police: “We are free women, you are the whores.” Large groups gathered at the universities of Isfahan and Ahvaz, and at Azad University and Shahid Beheshti University in Tehran, while a giant poster of Iran’s revolutionary leader was burned down at Mashhad.

Hengaw said strikes by workers were under way in Saqqez as well as Divandarreh, Marivan, Kamyaran and Sanandaj, and in Javanrud and Ravansar in the western province of Kermanshah.

Kurdistan governor Esmail Zarei-Kousha accused Iran’s foes of being behind the unrest.

“The enemy and its media ... are trying to use the 40-day anniversary of Mahsa Amini’s death as a pretext to cause new tensions but fortunately the situation in the province is completely stable,” he said, quoted by state news agency IRNA.

Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, the British-Iranian dual national held in jail in Tehran for five years, speaking in London at a Thomson Reuters conference, fought back tears as she praised the new internet generation on the streets of Iran “risking their lives and fighting for freedom”.

Apologising as she wiped away tears, she said the response to Amini’s death “sparked rays of hope for all of us, not just in Iran but across the globe, that hopefully justice will prevail”. She said Amini’s name had become the code for freedom.

Zaghari-Ratcliffe added that “the new, very different generation know a lot about freedom, they want a more transparent government, better lifestyle, freedom of speech and decent jobs, they know about rights and they are prepared to take risks to get it”. She said this generation had learned about freedom from the internet, TikTok and satellite TV, and would not back down.

She said: “Today the regime is not only fighting to maintain its power, but for its survival. The foundation of the Islamic Republic is based on terror. They survive in a system of repression. They have no limits to their brutality and oppression. The security forces arrest protesters and put them in solitary confinement, which is one of the most brutal yet less physical violent forms of torture.”

The west, she said, had a responsibility to ensure that Iranian state censorship was overcome, and to hold the Iranian regime to account.

The regime will be hoping the 40th day protests are a last gasp for the demonstrations, rather than a moment they reignite. Iranian judicial officials announced this week that they would put more than 600 people on trial for their role in the protests, including 315 in Tehran, 201 in the neighbouring Alborz province and 105 in the south-western province of Khuzestan.

Oslo-based group Iran Human Rights said the security forces’ crackdown on the Amini protests had killed a total of at least 141 demonstrators, in an updated death toll on Tuesday.

The US on Wednesday placed more than a dozen Iranian officials on its sanctions blacklist for the crackdown. The White House later said it was “concerned that Moscow may be advising Iran on best practices to manage protests, drawing on ... extensive experience in suppressing” opponents.

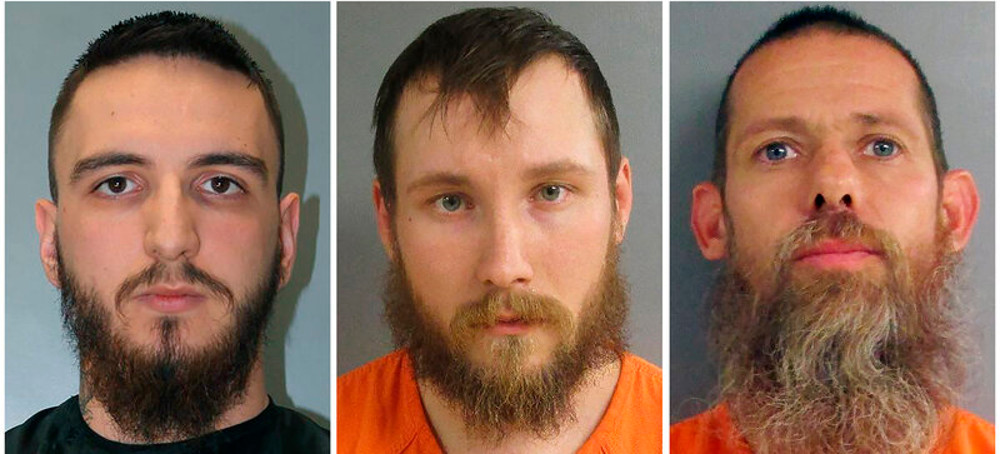

Paul Bellar (from left), Joseph Morrison and Pete Musico, who were accused of supporting a plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, were convicted of all charges Wednesday. (photo: AP)

Paul Bellar (from left), Joseph Morrison and Pete Musico, who were accused of supporting a plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, were convicted of all charges Wednesday. (photo: AP)

Joe Morrison, his father-in-law Pete Musico, and Paul Bellar were found guilty of providing "material support" for a terrorist act as members of a paramilitary group, the Wolverine Watchmen.

They held gun drills in rural Jackson County with a leader of the scheme, Adam Fox, who was disgusted with Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and other officials in 2020 and said he wanted to kidnap her.

Jurors read and heard violent, anti-government screeds as well as support for the "boogaloo," a civil war that might be triggered by a shocking abduction. Prosecutors said COVID-19 restrictions ordered by Whitmer turned out to be fruit to recruit more people to the Watchmen.

"The facts drip out slowly," state Assistant Attorney General Bill Rollstin told jurors in Jackson, Michigan, "and you begin to see — wow — there were things that happened that people knew about. ... When you see how close Adam Fox got to the governor, you can see how a very bad event was thwarted."

Morrison, 28, Musico, 44, and Bellar, 24, were also convicted of a gun crime and membership in a gang. Prosecutors said the Wolverine Watchmen was a criminal enterprise.

Morrison, who recently tested positive for COVID-19, and Musico watched the verdict by video away from the courtroom. Judge Thomas Wilson ordered all three to jail while they await sentencing scheduled for Dec. 15.

Defense attorneys argued that the three men had broken ties with Fox by late summer 2020 when the Whitmer plot came into focus. Unlike Fox and others, they didn't travel to northern Michigan to scout the governor's vacation home or participate in a key weekend training session inside a "shoot house."

"In this country, you are allowed to talk the talk but you only get convicted if you walk the walk," Musico's attorney, Kareem Johnson, said in his closing remarks.

Defense lawyers couldn't argue entrapment. But they attacked the tactics of Dan Chappel, an Army veteran and undercover informant. He took instructions from FBI agents, secretly recorded conversations and produced a deep cache of messages exchanged with the men.

Whitmer, a Democrat running for reelection on Nov. 8, was never physically harmed. Undercover agents and informants were inside Fox's group for months. The scheme was broken up with 14 arrests in October 2020.

Fox and Barry Croft Jr. were convicted of a kidnapping conspiracy in federal court in August. Daniel Harris and Brandon Caserta were acquitted last spring. Ty Garbin and Kaleb Franks pleaded guilty.

READ MORE Gov. Greg Abbott after a Houston press conference in 2017. (photo: Pu Huang/The Texas Tribune)

Gov. Greg Abbott after a Houston press conference in 2017. (photo: Pu Huang/The Texas Tribune)

“Our number-one priority as public servants is to follow the law,” Abbott, who served as Texas attorney general before he was elected, told staffers, according to his autobiography. Adhering to the law was “a way to ignore the pressure of politics, polls, money and lobbying.”

The Republican governor-elect said he rejected the path of Democratic President Barack Obama, whom he had sued 34 times as attorney general. Abbott claimed that Obama had usurped Congress’ power by using executive orders, including one to protect from deportation young people born in other countries and brought to the United States as children.

Now, nearly eight years into his governorship, Abbott’s actions belie his words. He has consolidated power like no Texas governor in recent history, at times circumventing the GOP-controlled state Legislature and overriding local officials.

The governor used the pandemic to block judges from ordering the release of some prisoners who couldn’t post cash bail and unilaterally defunded the legislative branch because lawmakers had failed to approve some of his top priorities. He also used his disaster authority to push Texas further than any other state on immigration and was the first to send thousands of immigrants by bus to Democratic strongholds.

Abbott’s executive measures have solidified his conservative base and dramatically raised his national profile. He is leading Democrat Beto O’Rourke in polls ahead of the Nov. 8 election and is mentioned as a potential 2024 GOP presidential contender. But his moves have also brought fierce criticism from some civil liberties groups, legal experts and even members of his own party, who have said his actions overstep the clearly defined limits of his office.

“Abbott would make the argument that Obama had a power grab, that he was trying to create an imperial presidency by consolidating power. That’s exactly what Abbott is doing at the state level,” said Jon Taylor, chair of the political science and geography department at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

At least 34 lawsuits have been filed in the past two years challenging Abbott’s executive actions, which became bolder since the start of the pandemic. Abbott used his expanded power at first to require safety measures against COVID-19, similar to what other governors did. But after pushback from his conservative base, he later forbade local governments and businesses from imposing mask and vaccine mandates. He also forced through Republican priorities, including an order that indirectly took aim at abortions by postponing surgeries and procedures that were not medically necessary.

Lower courts have occasionally ruled against Abbott, but Texas’ all-Republican highest court has sided with the governor, dismissing many of the cases on procedural grounds. Other challenges to Abbott’s use of executive power are still pending. In no case have the governor’s actions been permanently halted.

Abbott’s office did not respond to multiple requests for an interview or to questions from ProPublica and The Texas Tribune. In responding to the lawsuits, his legal team has defended his actions as allowed under the Texas Disaster Act of 1975, which gives the governor expansive powers.

Several of Abbott’s allies also declined to comment or didn’t return phone calls. Carlos Cascos, a former secretary of state under Abbott, said that in the end, it is up to the courts to decide whether the governor’s actions are unconstitutional.

“Until there’s some final judgment, the governor can do it,” Cascos, also a Republican, said. “If people want to change the rules or laws, that’s fine, but you change them by going through a process.”

Legal experts concede that Abbott has been successful so far, but they insist his moves exceed his constitutional authority.

“I’m not sure any other governor in recent Texas history has so blatantly violated the law with full awareness by the Supreme Court, and he’s been successful at every turn when he had no power to exercise it. It’s amazing,” said Ron Beal, a former Baylor University law professor who has written widely on administrative law and filed legal briefs challenging Abbott’s power. Although Texas Supreme Court justices are elected, Abbott has appointed five of the nine members of the state’s highest court when there have been vacancies.

Some Republicans also fault the governor’s actions. Nowhere was that more pronounced than when Abbott vetoed the Legislature’s budget last year after Democrats fled the state Capitol to thwart passage of one of the strictest voting bills in the country. The governor contended that “funding should not be provided for those who quit their job early.”

The move, which spurred a lawsuit from Democratic lawmakers, would have halted pay for about 2,100 state employees who were caught in the crosshairs.

Former state lawmakers, including two previous House speakers — Joe Straus, a Republican, and Pete Laney, a Democrat — as well as former Republican Lt. Gov. Bill Ratliff, weighed in on the dispute, filing a brief with the state’s Supreme Court calling the governor’s action unconstitutional and “an attempt to intimidate members of the Legislature and circumvent democracy.”

In response to the lawsuit, state Attorney General Ken Paxton argued that Abbott used his constitutional authority to veto the Legislature’s budget and that the courts didn’t have a role to play in disputes between political branches.

The Supreme Court agreed, saying it was not a matter for the judicial branch to decide. In the end, lawmakers passed a bill that restored the funding that Abbott had vetoed. Staffers didn’t lose a paycheck.

“It was a terrible thing to do, to threaten those people who do all that work, and threaten not to pay them while the governor and the members of Legislature were still going to get paid. How cynical is that?” said Kel Seliger, an outgoing Republican state senator from Amarillo who has split with his party’s leadership on various issues as it has shifted further right.

Weak Governor?

Research groups consistently rank Texas as a “weak governor” state because its constitution limits what the governor can do without legislative authorization. Executive officers such as the lieutenant governor and the attorney general are also independently elected, not appointed by the governor, further diluting the power of the office.

“The way the constitution is designed, unless it’s specified in the constitution, you don’t have that power. Period. And that’s why I think you can look at a whole variety of his actions as violating the constitution. He just doesn’t have it. He asserts it, and he gets away with it,” said James Harrington, a former constitutional law professor at the University of Texas at Austin who founded the Texas Civil Rights Project. Harrington initially filed a brief defending Abbott’s early use of pandemic-related executive orders limiting crowd sizes and the types of businesses allowed to remain open, but he said the governor’s later orders fell outside of the bounds of the law.

The weak-governor structure was created by the framers in 1876 who believed that Edmund Jackson Davis, a former Union general who led Texas following the Civil War, abused his powers as governor. A Republican who supported the rights of freed people, Davis disbanded the Texas Rangers and created a state police force that he used, at times, to enforce martial law to protect the civil rights of African Americans. He also expanded the size of government, appointing more than 9,000 state, county and local officials, which left a very small number of elected positions.

Currently, the governor’s office accrues power largely through vetoes and appointments. While the Legislature can override a veto, governors often issue them after the legislative session ends. The governor is the only one who can call lawmakers back.

During a typical four-year term, a governor makes about 1,500 appointments to the courts and hundreds of agencies and boards covering everything from economic development to criminal justice. The longer governors serve, the more loyalty they can build through appointments.

Abbott’s predecessor, Republican former Gov. Rick Perry, set the stage for building power through appointments. Over 14 years, Perry, a former state representative who became Texas’ longest-serving governor, positioned former employees, donors and supporters in every state agency.

Perry could not be reached for comment through a representative.

In contrast to his predecessor, Abbott, a jurist with no legislative experience, found other avenues to interpret and stretch the law. Abbott has benefited from appointments and vetoes, but he has also taken advantage of emergency orders and disaster declarations like no other governor in recent state history.

Disaster declarations are generally used for natural calamities such as hurricanes and droughts and are useful legally for governors who could face legislative gridlock or state agency inaction if going through normal channels. Abbott’s use of such tools has grown even as his party holds a majority in the state Legislature.

In his eight years as governor, Abbott has issued at least 42 executive orders. Perry signed 80 orders during his 14-year tenure, though they rarely brought controversy. He once required human papillomavirus vaccines for girls but backtracked after pushback from the Legislature.

“Rick Perry experimented with and developed a number of tools that former governors had,” said Cal Jillson, professor of political science at Southern Methodist University. “That he sharpened appointments would be one of those, executive orders would be another of those, the use of the bully pulpit would be a third. And Abbott went to school on that.”

Aiding Abbott in his push to strengthen executive power have been what is essentially a Republican-controlled state with no term limits for officeholders, a Legislature that meets every two years and innate fundraising skills that have helped him draw about $282 million (adjusted for inflation) in campaign contributions in the decade since he first ran for governor. He has used some of that haul to oppose candidates for office, including those in his own party, who have crossed him.

“It’s surprising that even the legislative leadership in the Republican Party has acquiesced to the degree they have because the powers that Abbott has accrued have to come from somewhere else, and it’s coming from them,” said Glenn Smith, an Austin-based Democratic strategist.

Last year, state lawmakers filed 13 bills aiming to curb the governor’s powers under the state’s disaster act, including Republican proposals that would require the Legislature’s permission to extend executive orders, which the governor now does every 30 days.

For instance, in 2019 Abbott issued an executive order to extend the state’s plumbing board after it was on track to shut down because of legislative inaction. He was able to do so by using his power under a disaster declaration that he first issued when Hurricane Harvey pummeled the state in 2017. He continued to renew the disaster declaration for nearly four years.

Abbott similarly continues to renew his 2020 COVID-19 disaster declaration even as he downplays the severity of the pandemic.

During the last legislative session, the only measure that passed — and was signed by Abbott — is a bill that removed the governor’s authority to restrict the sale, dispensing or transportation of firearms during a declared disaster.

“He governs like a judge, and that’s where the autocratic side comes out,” said state Rep. Lyle Larson, a Republican lawmaker whom Abbott tried to oust in 2018 after he pushed a measure that would make the governor wait a year before appointing to boards anyone who donated more than $2,500 to his campaign. The San Antonio lawmaker, who defeated Abbott’s preferred candidate at the time, has decided not to seek reelection.

Methodically Creating a Powerhouse

Abbott’s tenacity at building the power of the office can be traced back to his recovery after an oak tree fell on him while he was jogging at age 26, paralyzing him from the waist down, said Austin-based Republican consultant and lobbyist Bill Miller.

“He’s had setbacks in life that he’s overcome with tremendous success, and you don’t achieve that unless you’re persevering and a tough individual, and he’s both in the extreme,” Miller said.

At 32, Abbott was elected as a Harris County district judge, then was plucked from the bench by former Gov. George W. Bush, who elevated him to fill a vacancy on the Texas Supreme Court, a recommendation of Bush’s political adviser Karl Rove. Abbott ran for state attorney general and served 12 years before his election as governor in 2014.

He began testing the limits of his executive power quickly after his election.

In June 2015, six months into his first term, Abbott analyzed the state budget and vetoed more than $200 million in legislative directives that provided specific instructions to agencies on how certain funds should be used.

The move eliminated funding for various projects, including water conservation education grants and a planned museum in Corpus Christi. Abbott called some of the projects “unnecessary state debt and spending.”

The head of the Legislative Budget Board at the time argued that the governor had overstepped his authority because while he could veto line-item appropriations, he could not override the Legislature’s instructions to state agencies.

“We were just kind of flabbergasted. In all of your 150-plus years of precedent in state government, this had never been seen before,” said a longtime capitol attorney who asked to not be identified for fear of retribution. “It was kind of shocking to me that he was an attorney, was the attorney general, was on the (Texas) Supreme Court and, in my opinion, has such little value for the Texas Constitution and disrespect for the separation of powers. Such disrespect for a coequal branch of government.”

Over the years, Abbott continued to insert himself in decision-making that had previously not been in the purview of the governor’s office. His actions drew little public scrutiny because they involved procedural matters.

For instance, state agencies must typically seek public comment before publishing final regulations in areas such as the environment and education. But Abbott wanted to review proposed regulations before their public release. In 2018, his office directed agencies to first run them past the governor.

Citing a 1981 executive order by Ronald Reagan, Abbott’s chief of staff wrote that presidential review of proposed regulations helped to “coordinate policy among agencies, eliminate redundancies and inefficiencies, and provide a dispassionate ‘second opinion’ on the costs and benefits of proposed agency actions.”

But insisting on a review of agency proposals could give his office influence over matters that should not be left to the executive branch, critics said. For example, Abbott’s office could suggest softening regulations for emissions, which could be favorable to the oil and gas industry. While agency leaders do not have to comply, the boards and commissions overseeing them are often appointed by the governor.

Byron Cook, a Republican former state lawmaker from Corsicana, criticized Abbott’s request at the time and continues to believe that the governor overstepped his authority. “I think it’s a dangerous precedent, and I don’t think it’s in the best interest of the people in the state because it circumvents the legislative process,” Cook said in a recent interview.

At the time, Abbott’s office defended his line-item veto and his request to review agency rules as measures that were within his constitutional authority.

It’s unclear how much influence Abbott has wielded over that process in the past six years because the governor’s office is fighting the release of records to ProPublica and the Tribune that would show its interactions with state agencies.

While some lawmakers like Cook openly resisted Abbott’s push to grow the powers of the executive branch, Perry and Abbott have faced limited pushback because few have wanted to cross them, several former and current lawmakers told ProPublica and the Tribune.

“Somebody’s got to push back, but pushing back very often brings retribution, and so people are very careful,” said Seliger, who filed a bill in one of last year’s special legislative sessions aimed at removing the governor’s line-item veto power.

The measure was mostly symbolic because only Abbott has the power to decide what topics will be addressed in a special session — and Seliger’s bill was not among them.

Pushing an Agenda

As the pandemic hit Texas, Abbott reacted like most other governors struggling with an unprecedented public health crisis. He declared a public emergency on March 13, 2020, and issued a string of executive orders to deal with pandemic safety.

Abbott initially faced at least 10 lawsuits from business owners and conservative activists insisting his restrictions on businesses and crowd control violated the constitution. Charles “Rocky” Rhodes, a professor of state and federal constitutional law at South Texas College of Law Houston, said many of Abbott’s early actions were allowed under the disaster act’s sweeping provisions.

Legal challenges mounted as Abbott, in response to criticism from conservative groups and lawmakers, shifted course and asserted his disaster authority to control local government responses to the crisis and to impose his policy priorities. Rhodes pointed to an order forbidding employers from imposing vaccine mandates on employees. He said Abbott pushed “beyond the scope of his authority” and against federal vaccine mandates.

A string of legal actions filed by local governments and school districts in state and federal courts alleged that Abbott has tried to usurp the power of local entities, including the courts, by issuing orders that prohibited them from taking their own measures to deal with rising infection rates. Abbott’s legal team has defended the orders as within the scope of his expansive powers under the disaster act.

Two Texas parents who signed on as intervenors in a lawsuit against Abbott brought by La Joya and other independent school districts — Shanetra Miles-Fowler, a mother of three in Manor, and Elias Ponvert, a father of four in Pflugerville — told ProPublica and the Tribune that they saw Abbott’s order as political.

A lower-court order delayed implementation of Abbott’s prohibition against local governments imposing mask and vaccination mandates. The timing allowed parents to get through “the most dangerous months of the COVID pandemic,” said attorney Mike Siegel, who represented parents in the La Joya lawsuit. “Our fight likely saved the lives of students and staff who were facing a terrible choice of missing school or risking infection.” The masking cases are still pending at the Texas Supreme Court.

Abbott also used his disaster emergency powers to block judges from releasing prisoners who had not posted pretrial bail, prompting a lawsuit from 16 county judges and legal groups who argued that he had exceeded his constitutional powers. Abbott’s order also restricted the release of some charged with misdemeanors on time served with good behavior. His order said the disaster act gave him broad authority to control entrance and exit into facilities and the “occupancy of premises.”

In a court filing, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers argued that Abbott’s executive order “violates the separation of powers, interferes with judicial independence, violates equal protection and due process of law, and constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.”

Abbott had been trying unsuccessfully since 2017 to make it harder for those accused of violent crimes, or any prior offenses involving threats of violence, to get out of jail without posting cash bonds. When COVID-19 struck, some counties began releasing prisoners to try to reduce jail populations. In Harris County, where Abbott had once served as a judge, the jail was overflowing, and a federal judge in Houston had ordered the county to begin releasing about 250 prisoners per day.

Elizabeth Rossi, an attorney with the Civil Rights Corps, a nonprofit group that has represented plaintiffs in a lawsuit against Harris County challenging its felony bail practices, said Abbott’s “heartless and cruel” order impacted tens of thousands of prisoners held in Texas jails. “The human effects were really visceral,” she said.

One inmate, Preston Chaney, 64, died of COVID-19 while awaiting trial in the Harris County jail for three months, unable to post a small bond on charges that he stole lawn equipment and frozen meat.

Maurice Wilson, a 38-year-old with diabetes who served time in Harris County on drug possession charges, said he was terrified by the spread of COVID-19 as he sat in jail on a $10,000 bond. He was one of the many prohibited from release under Abbott’s order because of a prior misdemeanor assault conviction.

The Texas Supreme Court ultimately ruled that the Harris County judges and other plaintiffs lacked standing because they had not suffered injury and overturned a temporary restraining order that had halted enforcement of Abbott’s order. Abbott finally got a bail-reform package through the Legislature and signed it into law in September 2021. It formalized some aspects of his executive order.

What Abbott has tried to do is “make himself the chief prosecutor, the chief lawmaker and, with bail, the chief judge,” said Jessica Brand, a lawyer who represented a law enforcement group in the case. “We do not live in a kingdom, however, and such behavior is totally inconsistent with the framework of government this state has adopted.”

Power Concentration

Abbott’s power consolidation came to a head last year as his administration embarked on the state’s most ambitious and costly border initiative to date.

On May 31, 2021, about four months into President Joe Biden’s term, Abbott became the first governor in recent history to issue a border disaster declaration, which he said was needed because the federal government’s inaction was causing a “dramatic increase” in the number of people crossing into the state. The disaster declaration gave the governor more flexibility to shift funds, increase penalties for some state trespassing charges against immigrants and suspend rules, including those governing state contracts.

Abbott had already succeeded in securing more than $1 billion for border security during the Legislative session for the deployment of Department of Public Safety troopers and National Guard members under Operation Lone Star.

The governor launched the initiative in March of that year, contending it was necessary to stem the smuggling of drugs and people into the country through Texas. Under the disaster declaration that Abbott used to bolster his authority over the operation, immigrants charged with criminal trespassing for crossing the border through private property could be punished by up to a year in jail. He could also use state funds to build barriers.

In August, Abbott used his power to reconvene lawmakers for a special session where they again increased funding for border security by an additional $2 billion. Over the next few months, the governor continued to deploy National Guard members to the border with no end date for their mission.

As costs ballooned, Abbott chose not to bring lawmakers back for another special session. Instead, with help from a handful of Republican lawmakers and some state agency leaders, Abbott dipped at least twice into other agencies’ coffers to shift another nearly $1 billion to support an operation that has been plagued with problems since it began.

An investigation by ProPublica, the Tribune and The Marshall Project found that the state’s reported success included arrests unrelated to the border or immigration and counted drug seizures from across Texas, including those made by troopers who were not directly assigned to Operation Lone Star. Reporting by the Tribune and Army Times also exposed poor working conditions, pay delays and suicides among National Guard members deployed as part of the operation. And the Department of Justice is investigating potential civil rights violations related to Abbott’s directive to prosecute immigrants for trespassing. A spokesperson for the DOJ said she didn’t have any information to provide on the investigation.

Abbott’s office has previously said the arrests and prosecutions “are fully constitutional.”

Still, Abbott continues to expand the scope of the operation with no end in sight.

In April, the governor used the powers he had tested and amassed to announce his latest step under the umbrella of Operation Lone Star: Texas would transport migrants arriving at the border to Washington, D.C., later expanding the initiative to New York and Chicago. Once again, he used the powers of the disaster declaration and tasked the state’s emergency agency with carrying out the measure.

Since then, more than 12,500 people have been bused at a cost of about $14 million, according to state records. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, also Republicans, followed Abbott’s lead with their own initiatives. A Texas county sheriff is conducting a criminal investigation into the treatment of immigrants, and the D.C. attorney general is examining immigrant busing into Washington by Texas and Arizona. All of the governors have defended their actions as legal.

“I can’t remember that the governor has ever used state powers for this type of militarized border enforcement,” said Barbara Hines, founder and former director of the University of Texas Law School Immigration Clinic.

“What he’s doing under the guise of emergencies, disasters, invasions, whatever misnomer Abbott wants to give it to enforce federal immigration law,” she added, “I think that’s illegal.”

READ MORE Voters arrive to cast their ballot at a polling station. (photo: AP)

Voters arrive to cast their ballot at a polling station. (photo: AP)

An anonymous right-wing group is stoking fear throughout the state just days before midterm elections.

The anonymous group, which calls itself “Ben Sent Us,” a reference to Ben Franklin, has mailed out threatening letters en masse to more than a dozen county-level Democratic Party chairpersons in the state, vowing that members “will be locating your homes” and warning that those who are seen as allowing election fraud “will be considered a traitor and dealt with accordingly, as will you.” Ordinary residents in the state have also reported being targeted with ominous election fliers that warn someone is “watching” them.

It’s unclear who’s behind the propaganda campaign, but law enforcement agencies are taking the threats seriously after armed men in masks and tactical gear intimidated, filmed, and followed scared voters outside a ballot drop box in Maricopa County last week.

The website for Ben Sent Us, which was registered overseas on Aug. 30, doesn’t provide any clues as to who’s in charge. The page is hosted through OrangeWebsite, which is best known for being an anti-censorship registrar where you’ll find a host of alt-right, scam, and other sites on the platform as it allows payment in bitcoin.

The website contains a video that depicts a man being hanged as text on the screen reads, “When you’re texting, we are watching. When you’re making the drop, we are watching.” A printable flier on the website also depicts a noose.

Whether it’s a prank or a credible threat, the letters and fliers have spooked politicians and voters across the Grand Canyon State. The group responsible was cited four times in a lawsuit filed Monday in federal court in Phoenix. The suit goes after Clean Elections USA founder Melody Jennings, who organized the efforts to gather at ballot drop boxes in Maricopa County and has promoted Ben Sent Us on social media.

Brian Bickel, chairman of the Election Integrity Commission in Pima County, described the letter he received as “derogatory,” “inflammatory” and “intimidating.”

His colleague on the board, Misty Atkins, had a similar reaction.

“It was intimidating,” Atkins told The Daily Beast. “It was clearly meant to scare Democratic voters away, because it was addressed to the Democratic Party. I was so shocked when I read it.”

The letters draw inspiration from conservative commentator Dinesh D’Sousa’s discredited documentary 2000 Mules and the right-wing ecosystem of debunked ballot conspiracies that accompanies it. Arizona Senator Raquel Téran, who chairs the Arizona Democratic Party, blamed the state’s slate of Donald Trump-endorsed political newcomers for allowing groups like Ben Sent Us to crop up in Arizona.

“The recently reported voter intimidation in Arizona is a direct result of the blatant lies Republicans like Blake Masters, Kari Lake, Mark Finchem and Abe Hamadeh are spewing about our elections,” Téran said, referring to the state’s GOP nominees for U.S. senator, governor, secretary of state and attorney general.

Arizona Democratic Party spokesperson Morgan Dick confirmed several Democrats, including Téran, received “threatening” letters from Ben Sent Us in recent weeks. She said she filed a report with the FBI. An FBI spokesperson could not immediately be reached for comment.

“It certainly is very scary for anyone to receive that sort of threatening language,” Dick said.

Just ask Tucson resident Dan Roper, who was alarmed to find a creepy election flier stuck to his car—and many others in the lot—at a movie theater on Sept. 24. The note read “I’m watching you…”

“I think it’s a pretty obvious attempt to intimidate people and promote completely baseless claims of election fraud,” Roper said. “Some people spend their Saturday knocking on doors to help elect a candidate, while this group spent theirs trying to scare people.”

Roper said it’s untenable “to make Arizonans afraid that they’re being watched at the polls and in their daily lives, or that their vote won’t count even when they’ve done nothing wrong.”

The group engaged in similar leafletting campaigns around the same time in Flagstaff and Tempe, a major city in the Phoenix metro.

“We are aware of these flyers,” Tempe Police Officer Thomas Byron Jr. said. “At this time, we are looking into this incident and will continue to monitor for similar and related incidents.”

READ MORE Emperor penguins are seen in Dumont d'Urville, Antarctica April 10, 2012. (photo: Martin Passingham/Reuters)

Emperor penguins are seen in Dumont d'Urville, Antarctica April 10, 2012. (photo: Martin Passingham/Reuters)

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said emperor penguins should be protected under the law since the birds build colonies and raise their young on the Antarctic ice threatened by climate change.

The wildlife agency said a thorough review of evidence, including satellite data from 40 years showed the penguins aren’t currently in danger of extinction, but rising temperatures signal that is likely. The agency's review followed a 2011 petition by the environmental group Center for Biological Diversity to list the bird under the Endangered Species Act.

Climate change has caused colonies to experience breeding failures, according to the government. The Halley Bay colony in the Weddell Sea, the second-largest emperor penguin colony in the world, experienced several years of poor sea ice conditions, leading to the drowning of all newborn chicks beginning in 2016, the government said.

The endangered status will promote international cooperation for conservation strategies, increase funding for conservation programs and require federal agencies in the United States to act to reduce threats.

Tuesday's designation was described as a warning that emperor penguins need “urgent climate action” in order to survive by Shaye Wolf, the climate science director at the Center for Biological Diversity.

“The penguin’s very existence depends on whether our government takes strong action now to cut climate-heating fossil fuels and prevent irreversible damage to life on Earth,” Wolf said.

The 1973 Endangered Species Act is credited with bringing several animals back from the brink of extinction, including grizzly bears, bald eagles, gray whales and others. The law has frustrated some drilling and mining industries among others, which can be stopped from developing areas deemed necessary for species survival.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.