Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

In real life, the impending crackdown on abortion will probably involve more snitching and surveillance than militarized border checkpoints. People looking to terminate their pregnancies will be suspected of crimes, while providers, for now, will bear the brunt of the legal consequences. The liberal PAC MeidasTouch, which made the video, seemed more interested in scaring up money for Democrats than in giving its audience an accurate forecast. But its fantasy of our post-Roe dystopia gets one thing right: Wherever abortion is criminalized, there will be an army of law-enforcement officials waiting to punish it.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization has given states the green light to make abortion a crime at a time when Democratic leaders are scrambling to prove their tough-on-crime credentials. By throwing money at the police to boost its election odds, the party has all but ensured that red-state cops will be better equipped to enforce the looming regime — a civil-rights disaster the party’s constituents were counting on it to prevent.

This dire predicament is a result of Democrats wanting it both ways: to be seen as the party of democracy and civil rights and as that of bigger and tougher policing. As Dobbs shows, it’s always the former part of the ledger that is vulnerable to compromise.

The summer of 2020 now feels like ancient history. In response to the killing of George Floyd and what was likely the biggest protest movement in U.S. history, Democrats seemed poised to rein in the cops and shore up civil rights. They made extravagant shows of mourning for Floyd, donning kente stoles and kneeling on the Capitol floor. But their plans fizzled after the 2020 election, which left the party with a razor-thin majority in the Senate, allowing rogue congressional Democrats and concerns about inflation to stall much of President Biden’s agenda.

Party moderates laid their troubles at the feet of progressive activists who called for less spending on cops. To “save lives, we should not defund — instead, we must invest to protect,” 19 lawmakers wrote in a May 6 letter to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, even though Congress had just set aside $3.9 billion for law-enforcement grants in its 2022 government funding package — $500 million more than the year before. Biden tried to outflank the right by promising to spend more on them, urging local governments to use funds from his $1.9 trillion COVID-relief bill to fill police coffers. “Spend this money now,” the president begged officials this May. The White House estimates that last year at least 300 localities and more than half of U.S. states allocated $6.5 billion in federal money for “public safety.”

A lot of this was surely meant to be theater, a reflexive bid to save face ahead of the 2022 midterms. But Republicans have been wildly successful in seizing control of the U.S. legal apparatus and molding its agenda to their will, from the Supreme Court down to state and local prosecutors’ offices. And we do not have to guess how they will use their replenished arsenal.

The GOP has hardly been shy about its plan to institute its new anti-abortion regime. Thirteen Republican-controlled state legislatures had trigger laws in place to implement bans or tighter restrictions after the Dobbs ruling was handed down. Some providers had to send patients home from their waiting rooms for fear of being arrested. The Louisiana House of Representatives flirted with a bill that would have reclassified abortion as a type of homicide. Sixty-five members voted to amend it to make it less harsh; a stunning 26 did not.

The Supreme Court has punted the logistics of its decision down to the states. The details will be handled by a patchwork of local enforcement philosophies, the most forgiving of which are not sustainable. Dozens of blue-city prosecutors promised in June not to uphold laws criminalizing abortion, in effect signaling to local cops that arresting transgressors would not be worth their while. The move led Vox to declare that “district attorneys could be a last defense” against the wave of bans. But their recalcitrance is poor consolation when Republican attorneys general may be able to simply override their decisions and when prosecutors in less punitive neighboring states, where people might flee to get abortions, still relish playing tough. Indiana’s attorney general, for example, did a media blitz in which he suggested he might prosecute a doctor who performed an abortion on a 10-year-old rape victim from Ohio, though the doctor had not broken any laws. The DA’s office of Texas’s Tarrant County, home to more than 2 million people, tweeted ominously in response to the Court’s decision: “We followed Roe v. Wade when it was the law and we will follow Texas state law now.”

Dobbs is a reminder that what constitutes a crime is frequently arbitrary. If the right powerful people wish it so, there are few limits to what you can be charged with. There are doctors in Louisiana, Kentucky, and South Dakota who woke up on the morning of June 24 with jobs that were legal; that evening, those jobs could land them in prison. Their reality complicates the very notion of a crime wave: The Court’s decision — which will not actually end abortion — practically guarantees such a wave and, with it, a whole new class of criminals.

A lot of this was predictable, which makes the Democrats’ apparent lack of foresight all the more striking. Even before the January 6 coup attempt and GOP apologia that came after, it was clear that Republicans saw Democratic wins at the ballot box as, by their very nature, illegitimate and unlawful. False accusations of fraud coupled with suppression tactics have cast a pall of criminality over the mere act of voting blue. These are but a preview of what could be in store.

For the Supreme Court, it is clear that whatever rights are not explicitly guaranteed by the Constitution — such as same-sex and interracial marriage — and surely some that are, will remain in place only as long as Republicans allow them to be. The right to obtain contraception seems directly imperiled by Dobbs. It is underappreciated how much of a legal playground we live in, and how firmly the conservative movement has its hands on a bulldozer’s keys, ready to tear it all down.

So what happens when a lot more of us suddenly become criminals? And how do we move forward when Democrats, our self-styled protectors, continue to respond by shoveling money at the organs that will punish our crimes? Something has to give as more people are forced to rely on underground networks for safe abortions. Democratic leaders can keep up their myopic allegiance to law enforcement, or they can see how many more of their constituents are entering its crosshairs and fight for us.

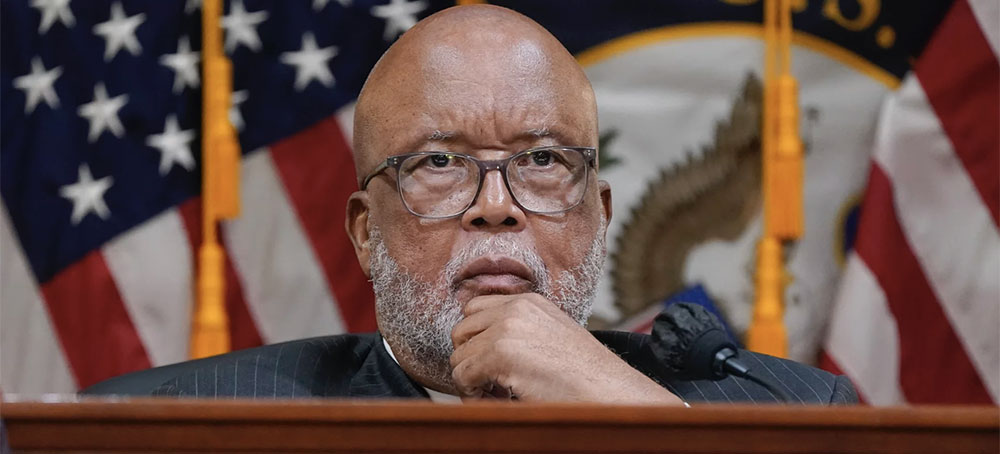

Chairman Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., listens as the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol holds a hearing at the Capitol on Tuesday. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Chairman Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., listens as the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol holds a hearing at the Capitol on Tuesday. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

The House select committee leading the investigation is asking the federal agency to turn over reportedly deleted text messages from the days surrounding the attack as well as any relevant action reports. The Secret Service has until Tuesday to produce agents' phone records, that some believe may shed light on President Donald Trump's actions during the riot.

"We need all the texts from the fifth and sixth of January," Jan. 6 committee member Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif,. told ABC News. "We need to get this information to get the full picture."

Lofgren added that she and the rest of the nine-member panel investigating the insurrection were shocked to hear that the Secret Service does not seem to back up their phone data.

The Secret Service has recently garnered attention after former White House aid Cassidy Hutchinson testified to the Jan. 6 committee. According to Hutchinson, Trump had a heated exchange with his Secret Service detail after demanding to be driven up to the Capitol on the day of the insurrection.

Anthony Guglielmi, a spokesperson for Secret Service, told NPR that his agency plans to "swiftly" respond to the panel's subpoena though it's unclear what records will be retrievable.

The Secret Service insists the Jan. 6 probe has had its "full and unwavering cooperation"

The erased phone data was brought to light earlier this week by Joseph Cuffari, the inspector general for the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees the Secret Service. In a letter to Congress, Cuffari accused the Secret Service of erasing relevant text messages after his office requested such records and generally causing confusion and delays to his office's investigation.

Guglielmi has repeatedly denied that the agency "maliciously" deleted text messages and disputed claims that his agency has been uncooperative.

"The January 6th Select Committee has had our full and unwavering cooperation since its inception in March of 2021 and that does not change," Guglielmi said in a statement to NPR.

According to Guglielmi, some of the department's phone data were lost due to a "pre-planned, three-month system migration" that required agents to reset their mobile phones at the beginning of 2021.

He said that while some text messages were lost by the time of Congress' inquiry, the Secret Service was able to turn over phone data from 20 agents including former Uniform Division Chief Tom Sullivan who had received a text message from the chief of the U.S. Capitol Police on Jan. 6, 2021, requesting emergency assistance.

Guglielmi added that over the last 18 months, the Secret Service has provided dozens of hours of formal testimony from special agents as well as over 790,000 unredacted emails, radio transmissions, and operational and planning records.

What might happen if the Secret Service doesn't comply

If the Secret Service is unable to turn over the deleted messages, the next major question will be if that's intentional, according to Ankush Khardori, a former federal prosecutor.

"There's a big factual difference between the inadvertent loss of communications and a deliberate effort to delete these communications," Khardori told NPR. "Really what you would want to know is what are the Secret Service's record keeping rules, regulations and protocols, did anyone run afoul of them and in the worst case scenario, did someone make a deliberate effort to destroy these communications."

To get to the bottom of what happened, he said Congress may launch an investigation into the Secret Service's record keeping system or call for members of the Secret Service to testify.

Khardori said it's too soon to tell but the Jan. 6 committee's probe into an agency of the executive branch is significant.

"It's not that unusual for Congress to seek information from the executive branch, including through subpoenas, but this is different because it's more public, more assertive, more aggressive and it suggests concern among at least some members of the committee that the Secret Service hasn't been forthright with their answers," he said.

The next Jan. 6 committee hearing is scheduled at 8 p.m. ET Thursday, with a specific focus on Trump's failure to act to stop the insurrection.

A pharmacist helps a customer at a CVS in Washington, DC, on April 4. (photo: Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call/Getty Images)

A pharmacist helps a customer at a CVS in Washington, DC, on April 4. (photo: Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call/Getty Images)

Under this Supreme Court, patients could struggle to obtain lifesaving drugs like methotrexate.

The drug is the most common pharmaceutical treatment for ectopic pregnancies, a life-threatening medical condition where a fertilized egg implants somewhere other than the uterus — typically a fallopian tube. If allowed to develop, this egg can eventually cause a rupture and massive internal bleeding. Methotrexate prevents embryonic cell growth, eventually terminating an ectopic pregnancy.

And so many patients who take methotrexate say they have become the latest victims of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization — the decision overruling Roe v. Wade.

It’s unclear how widespread this phenomenon is, though the problem is serious enough that the Arthritis Foundation put out a statement warning that “arthritis patients who rely on methotrexate are reporting difficulty accessing it,” and that “at least one state — Texas — allows pharmacists to refuse to fill prescriptions for misoprostol and methotrexate, which together can be used for medical abortions.”

In some cases, pharmacists are reportedly reluctant to fill methotrexate prescriptions in states where abortion is illegal, and doctors are similarly reluctant to prescribe it. In other cases, pharmacists may refuse to fill valid methotrexate prescriptions because they personally object to abortion, even in states where the procedure remains legal.

The phenomenon of patients struggling to obtain therapeutic drugs that can be used in abortion care appears to be severe enough that, on Wednesday, President Joe Biden’s administration released a four-page “Guidance to Nation’s Retail Pharmacies.” It informed them that federal laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of disability or pregnancy may require pharmacists to fill prescriptions for drugs like methotrexate. (The question of whether a particular denial by a particular pharmacist violates federal law will depend on the specifics of the case.)

Ultimately, however, laws are only as good as the courts that interpret them. And disputes over whether states can ban mifepristone, or whether pharmacists can simply refuse to dispense certain drugs, are likely to be resolved by the same justices who gave us Dobbs.

At best, that means a lot of confusion for patients until the courts sort these issues out. And, given this Court’s hostility toward abortions and sympathy for religious conservatives, it is likely that many patients will be denied prescription drugs.

Federal civil rights law probably requires pharmacists to dispense lawful drugs, but this Supreme Court is likely to give an exemption to religious conservatives.

It is always dangerous to predict what kind of laws may emerge from the fever swamps of the Texas state legislature. But red states are probably less likely to enact a blanket ban on drugs like methotrexate, which have many therapeutic uses unrelated to abortion, than they are to ban drugs like mifepristone that are primarily used in abortion care.

Even if drugs like methotrexate remain legal in all 50 states, however, individual pharmacists may refuse to dispense them, and doctors may be reluctant to prescribe them — out of a misguided belief that the drug is illegal, a fear of being targeted by overzealous prosecutors, or a religious or moral objection to abortion.

In its Wednesday guidance, the Biden administration argues that federal civil rights laws prohibiting “discrimination on the basis of sex and disability” may require pharmacists to dispense certain drugs even after Dobbs. The primary anti-discrimination law governing health care, which was enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act, prohibits discrimination by “any health program or activity” that receives federal funding through a program like Medicare or Medicaid. So most doctors, hospitals, and pharmacies are covered by this law.

Suppose, for example, that “an individual experiences severe and chronic stomach ulcers, such that their condition meets the definition of a disability under civil rights laws.” If a doctor prescribes the drug misoprostol, which is used to prevent stomach ulcers but is also used in medication abortions, then a pharmacy “may be discriminating on the basis of disability” if it refuses to dispense this drug “because of its alternative uses.”

Similarly, the guidance argues that a pharmacist may violate federal sex discrimination laws, which also prohibit discrimination on the basis of pregnancy, if it refuses to dispense methotrexate to a patient with an ectopic pregnancy.

Even if federal civil rights law does require pharmacists to dispense these and similar drugs, however — and that question will need to be litigated — it is likely that this Supreme Court will permit pharmacists with religious objections to those drugs to ignore federal law.

In June 2016, the Supreme Court announced that it would not hear Stormans v. Wiesman — a case involving a pharmacy that refused to dispense emergency contraception, in violation of a state regulation, because the owners objected to this form of contraception on religious grounds. The timing of this refusal to hear the case was significant: Justice Antonin Scalia had died just a few months earlier, depriving the Court’s Republican appointees of the majority they’d enjoyed for many years.

Without the votes he needed to take up the case, Justice Samuel Alito wrote an absolutely livid dissent in Stormans, accusing the state of “hostility to pharmacists whose religious beliefs regarding abortion and contraception are out of step with prevailing opinion in the State.” Notably, Alito’s opinion was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, the most moderate member of the Court’s current six-justice conservative majority.

It is exceedingly likely, in other words, that if a similar case were to arise today — perhaps a case involving a pharmacist who objects, on religious grounds, to dispensing drugs like methotrexate, mifepristone, or misoprostol — that this Supreme Court would side with the pharmacist. It’s also likely that this Supreme Court would show similar solicitude to a doctor or other health provider who refuses to prescribe a medication because of a religious objection.

In a densely populated city, that kind of decision is likely to inconvenience many patients, who might have to walk several blocks to a different pharmacy in order to get their prescription filled. But in rural areas where patients could have to drive to another town to find another pharmacist, one pharmacist’s refusal to fill their prescription could be a very serious imposition — and that’s assuming that the pharmacist in the next town doesn’t also have religious objections to certain drugs.

In sparsely populated areas, in other words, patients are not only likely to struggle to find abortion care. Patients with common conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or psoriasis may also struggle to fill their prescriptions, even if they take these drugs for reasons that have nothing to do with a pregnancy.

Nikole Hannah-Jones. (photo: Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

Nikole Hannah-Jones. (photo: Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

The settlement may resolve any potential legal action, but what she’s owed is far more than what was offered.

“The steps taken to resolve the lingering potential legal action posed by Ms. Hannah-Jones will hopefully help to close this chapter and give the university the space to focus on moving forward,” David Boliek, chair of the university’s board of trustees, said in a statement.

While the chapter may be closed, according to the News & Observer of Raleigh, N.C., the settlement was for less than $75,000, and many believe Hannah-Jones is deserving of more.

Back in 2021 during the time of her original appointment, the acclaimed New York Times Magazine writer was criticized by conservatives who were intimidated by her involvement with the 1619 Project, which reexamined the history of American slavery and its legacy. University faculty, students, and academics outside of the institution quickly came to Hannah-Jones’ defense after the decision was made, but the professor had plans of her own.

Hannah-Jones told the university that she was considering legal action on the grounds of discrimination. Feeling the pressure to respond, the board of trustees decided to grant her tenure a month later. The damage however, had already been done. Hannah-Jones declined the reluctant offer, and joined the faculty of Howard University.

In a statement released on Saturday, the NAACP Legal Defense Fund who represented Hannah-Jones, said that they “believe that the settlement is a victory for the right to free expression — a cornerstone of our democracy that has too frequently been infringed or ignored when claimed by Black people and people from other marginalized groups.”

“Ms. Hannah-Jones is grateful to have this matter behind her,” said Janai S. Nelson, the president and director-counsel of the Legal Defense Fund. “And she looks forward to continuing her professional work committed to using the power of investigative journalism to expose the truth about the manifestations of racism in our society and training the next generation of aspiring journalists to do the same at her academic home of Howard University.”

Mark MacGann. (image: Getty Images/Reuters/Guardian UK)

Mark MacGann. (image: Getty Images/Reuters/Guardian UK)

Regulators entered Uber’s offices only to see computers go dark before their eyes

“hi!” she typed in a message that’s part of a trove of more than 124,000 previously undisclosed Uber records. “My laptop shut down after acting funny.”

But her computer’s behavior was no mystery to some of her superiors.

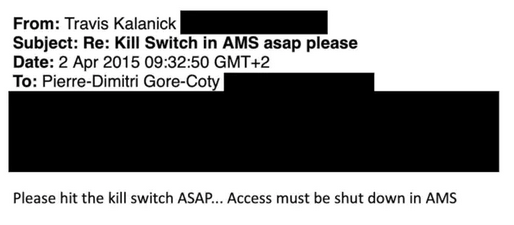

Uber’s San Francisco-based chief executive, Travis Kalanick, had ordered the computer systems in Amsterdam cut off from Uber’s internal network, making data inaccessible to authorities as they raided its European headquarters, documents show.

“Please hit the kill switch ASAP,” Kalanick had emailed, ordering a subordinate to block the office laptops and other devices from Uber’s internal systems. “Access must be shut down in AMS,” referring to Amsterdam.

Uber’s use of what insiders called the “kill switch” was a brazen example of how the company employed technological tools to prevent authorities from successfully investigating the company’s business practices as it disrupted the global taxi industry, according to the documents.

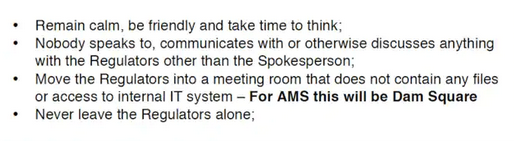

During this era, as Uber’s valuation was surging past $50 billion, government raids occurred with such frequency that the company distributed a Dawn Raid Manual to employees on how to respond. It ran more than 2,600 words with 66 bullet points. They included “Move the Regulators into a meeting room that does not contain any files” and “Never leave the Regulators alone.”

That document, like the text and email exchanges related to the Amsterdam raid, are part of the Uber Files, an 18.7-gigabyte trove of data that former top Uber lobbyist Mark MacGann provided to the Guardian. It shared the trove with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, a nonprofit newsroom in Washington that helped lead the project, and dozens of other news organizations, including The Washington Post. The files, spanning 2013 to 2017, include 83,000 emails and thousands of other communications, presentations and direct messages. MacGann was the company’s head of public policy for Europe, the Middle East and Africa from 2014 to 2016.

They show that Uber developed extensive systems to confound official inquiries, going well past what has been known about its efforts to trip up regulators, government inspectors and police. Far from simply developing software to connect drivers and customers seeking rides, Uber leveraged its technological capabilities in many cases to gain a covert edge over authorities.

In written responses to questions, Uber acknowledged that the company made numerous missteps during the time covered by the files, an era when Kalanick, who was ousted by the board in 2017, led the company. “We have not and will not make excuses for past behavior that is clearly not in line with our present values,” said company senior vice president Jill Hazelbaker. “Instead, we ask the public to judge us by what we’ve done over the last five years and what we will do in the years to come.”

Devon Spurgeon, a spokeswoman for Kalanick, said in a statement to The Post that Uber’s expansion efforts were led by more than 100 people in dozens of countries — with approval from the company’s legal, policy and compliance teams.

“Uber, like most other businesses operating overseas, used tools that protect intellectual property and the privacy of their customers, and ensure due process rights are respected in the event of an extrajudicial raid,” Spurgeon said. “They are a common business practice and not designed or implemented to ‘obstruct justice.’ These fail-safe protocols do not delete any data or information and all decisions about their use involved, were vetted by, and were approved by Uber’s legal and regulatory departments. Notably, Mr. Kalanick did not create, direct or oversee these systems set up by legal and compliance departments and has never been charged in any jurisdiction for obstruction of justice or any related offense.”

According to the documents and interviews with former employees, the company used a program called Greyball to keep authorities from hailing cars — and potentially impounding them and arresting their drivers.

It used a technology called “geofencing” that, based on location data, blocked ordinary use of the app near police stations and other places where authorities might be working. And it used corporate networking management software to remotely cut computers’ access to network files after they had been seized by authorities.

The Post was unable to learn whether authorities ultimately gained access to all the data they were seeking in such cases. Bloomberg News, which first reported on the kill switch in 2018, reported that in at least one case, Uber turned over records not initially available to authorities after they produced a second search warrant.

While some of these technologies have been reported previously, the Uber Files provide the most extensive, behind-the-scenes account of how Uber executives ordered their deployment to gain advantages over authorities.

Uber discussed or invoked the kill switch — code-named Ripley — more than a dozen times in at least six countries over a two-year span, according to the new documents and previous reporting on the tool. References to Greyball appear repeatedly, in countries including Denmark, Belgium and Germany. The documents show that, in at least some cases, Uber’s legal department in San Francisco was aware of the use of the kill switch.

Uber employees sometimes expressed concern about the use of technological tools amid multiplying government investigations. In a text exchange in January 2016, officials in Europe discussed the pros and cons of building an alternative version of the Uber app.

“Point is more to avoid enforcement," wrote Thibaud Simphal, then general manager for Uber in France.

Simphal, who is now Uber’s global head of sustainability, said in a recent statement: “From 2014 to 2017, Uber has been in the news both for its positive impact on mobility and the economic opportunities it has created and for certain practices that do not comply with the frameworks and requirements of the countries in which we have developed. We have publicly acknowledged this. Our current CEO, Dara Khosrowshahi, has been transparent about these issues since his arrival, and has made significant reforms to the company’s culture.”

Kill switch

Uber’s tactics were born out of more than stubbornness. To top Uber executives, they were existential. What started as a simple idea in 2008 — to offer on-demand taxi service in private cars — had burgeoned by 2015 into a bona fide Silicon Valley “unicorn,” a start-up rapidly multiplying in value but one that hemorrhaged money, requiring regular cash infusions from investors.

It faced fierce rivalry from companies such as Didi in China, Yandex in Russia, Ola in South Asia and Lyft in the United States. Uber competed in part by luring customers to its app with steep discounts, and it recruited drivers with generous incentives.

The business model also relied on overcoming legal barriers to competing with a taxi industry that was heavily regulated in much of the world. Authorities dictated the colors of those competing vehicles, the licensing and insurance rules for drivers, and how and when drivers worked.

Uber insisted on designating its drivers as independent contractors rather than full-time employees. The company said the distinction afforded drivers more work flexibility, but it also freed Uber from the obligation to pay them costly benefits while limiting its own legal liability.

Confrontations also developed between authorities and the company over its business practices. Uber sometimes would not comply with cease-and-desist orders if it believed immediate enforcement actions were unlikely, two former employees said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to describe sensitive matters.

“I don’t have any comment on whether that was the case back then, but that’s certainly not how we would respond today,” said Uber spokesman Noah Edwardsen.

Such confrontations forced questions about long-established taxi regulations into view. Negative articles about arrests and other clashes, meanwhile, increased public awareness of the service, a former employee told The Post.

Kalanick exuded an overt hostility toward the taxi industry — which he dubbed “Big Taxi” — and the regulators, he argued, protected it from competition, the documents and news reports show.

In the period covered in the documents, Uber was embarking on an aggressive expansion in countries such as Spain, France, the Netherlands and Belgium — many of which outlawed paid transport in private personal vehicles.

Regulators barged in, conducting raid after raid, in an effort to prove Uber was flouting the law, while police conducted stings to catch drivers in the act.

Inside Uber’s offices, however, law enforcement agents were sometimes surprised to find that the computers — as many as two dozen simultaneously — would go black. That was the experience of one individual close to a raid in Paris on March 16, 2015, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to candidly describe the events.

That same month in Amsterdam, the company’s Europe hub, company executives worried about a looming crackdown and likely raid by transport authorities to collect evidence, the documents show.

Uber was making preparations that included moving documents off-site and compiling a list of office employees “to ensure an IT kill gets everyone,” according to an email at the time from Zac de Kievit, European legal director for Uber.

Uber also was finalizing its Dawn Raid Manual, which was shared by email with employees in Europe. While other companies give written guidance on how employees should interact with authorities, Uber’s was striking in its details. The manual, labeled “CONFIDENTIAL -- FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY,” formalized many of the strategies Uber would employ against regulatory raids, the documents show.

Uber did not respond to questions about the raid manual.

‘Unexpected visitors’

On several occasions, including twice in Montreal in May 2015, authorities entered the company’s offices only to find devices such as laptops and tablets resetting at the same time, court documents showed.

The kill switch helped thwart authorities by locking devices out of Uber’s internal systems. Although it was used internationally, the kill switch was controlled centrally by Uber’s San Francisco IT department and through another location in Denmark to protect local employees who might otherwise be accused of obstruction or forced to override it, two former employees said. According to the documents, Uber used it to cut access to devices that could have been seized in raids, sometimes while authorities searched for evidence within Uber’s offices.

Uber officials eventually began hitting the kill switch as soon as they considered a raid imminent, the documents show. The action blocked the laptops from accessing information held on remote servers, former employees said, making the devices unable to retrieve even email.

Some employees engaged in stall tactics so the kill switch could be activated before police got their hands on their devices by, among other strategies, asking that the police or tax authorities wait together in a room without computers until local lawyers arrived, according to the documents and interviews with people familiar with the tactics.

“The procedure was, if you have law enforcement, you try to buy time by greeting them, and call San Francisco,” said one of Uber’s former lawyers in Europe, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe the tactics. “Even if it was 2 a.m. in San Francisco, there were people who were supposed to react.”

Many companies use kill switches or other remote administration tools to cut off devices when employees are fired or lose them. Inside Uber, workers were told they would also be used in case of “unexpected visitors,” a term that covered angry passengers or drivers as well as police or other authorities, according to former executives.

Uber was never charged criminally with obstruction of justice, and the company said it shut down machines mainly so that investigators did not see more than they were entitled to. When investigators later asked for specific documents, the company generally furnished them, said former employees.

Some European legal experts said using a tool such as a kill switch is legal only before a government authority produces paperwork entitling them to look for specific documents. But afterward, cutting access could break national laws, they said.

“If a raid by a supervisor or economic investigator has already begun, and it has been made clear that copies of records are being requested, a company may no longer intervene by making them inaccessible,” said Brendan Newitt, of De Roos & Pen Lawyers in the Netherlands. “The same applies if regular investigators have already started, for example, a computer or network search to obtain the records.”

In France, a prosecutor involved in the initial investigation could add new charges based on a kill switch “if it turns out that it is not automated, that there is a human action leading to a disconnection and that there is a will to obstruct justice,” said Sophie Sontag Koenig, a teacher at Université Paris Nanterre with a doctorate in criminal law who specializes in technology issues.

Uber’s Hazelbaker said, “Uber does not have a ‘kill switch’ designed to thwart regulatory inquiries anywhere in the world" and that it has not used one since Kalanick’s replacement, Khosrowshahi, became chief executive. Although software that remotely isolates devices is standard for companies to use in cases of lost or stolen laptops, Uber said “such software should never have been used to thwart legitimate regulatory actions.”

The statement from Kalanick’s spokeswoman said, “Travis Kalanick never authorized any actions or programs that would obstruct justice in any country.” She also rejected as “completely false” any allegation that he “directed, engaged in, or was involved” in any activity that may have obstructed justice.

Local operations managers, who had a great deal of autonomy in running their own offices, often made the initial requests for activation of the kill switch, said former employees. That would lead to consultations with the general manager of the relevant global region as well as top executives in California, according to former executives and the documents. Employees sometimes copied top officials including Kalanick and general counsel Salle Yoo. San Francisco executives typically issued the final command, said several former employees.

“On every occasion where I was personally involved in ‘kill switch’ activities, I was acting on the express orders from my management in San Francisco,” Mark MacGann, Uber’s former top lobbyist in Europe, said in a statement.

The former European lawyer for Uber who spoke on the condition of anonymity said colleagues sometimes raised objections with Yoo.

“Of course we highlighted it to Salle, that this is not how you should proceed in Europe,” the lawyer said. “But that was kind of disregarded. There was a bigger mission behind it: ‘Everyone is wrong, and we are right.’ ”

Yoo provided the following statement in response to requests for comment:

“During my time at Uber, we developed systems to ensure the company acted ethically and consistent with the law in the countries where we operated. Working with outside counsel, my team and I instituted policies to safeguard the company’s data and made it clear that the policies were never designed to prevent or inhibit the company’s cooperation with regulators and local authorities. If I had learned of any illegal or improper behavior, I would have immediately taken steps to stop it.”

Corporate siege mentality

Looking back, a corporate siege mentality and poor training contributed to serious mistakes in judgment, said another former Uber executive from this era.

“That’s rookie bulls---,” the executive said of cutting access after a raid had begun. “It’s cowboy culture, no governance, improper compliance controls.”

In one instance, documents show de Kievit, the European legal executive, sent direct instructions copying Kalanick and Yoo regarding a raid in Paris in November 2014.

“Please kill access now,” de Kievit wrote, according to an email from the trove of internal Uber documents.

He soon followed up with another email, “Please let me know when this is done.”

The kill was done 13 minutes after the initial request, the documents show.

“They have not been too aggressive so far, but we are taking no risks,” de Kievit wrote to policy and strategy head David Plouffe, referring to authorities.

Plouffe, a former campaign manager and adviser to President Barack Obama, said that his time at Uber coincided with a “fierce debate about how and whether ridesharing should be regulated,” during which some within Uber wanted “to go too far.”

“I did my best to object when I thought lines would be crossed — sometimes with success, sometimes not,” Plouffe said in a written statement.

De Kievit, who is now an attorney in Australia, did not respond to questions emailed to his law office in Melbourne or voice-mail messages on his cellphone.

In addition to the kill switch, executives sometimes used a comprehensive remote-control program called Casper, a commercial software suite Uber tailored for its own use, the documents show. Casper could cut network access even after devices were removed by authorities, documents and interviews reflect.

Fake view

Uber employees shielded activity in the app with Greyball, which falsely indicated to suspected authorities that no Uber rides were available near them, in an effort to thwart investigations and enforcement actions, the documents show.

Greyball was created as a fraud-fighting tool to limit scammers’ access to the app, a former executive said, and was at times used to frustrate violent Uber opponents hunting drivers. But Uber operations executives took control of the program and redeployed it against the government, former employees said.

The company used geofencing, meanwhile, to limit where people could access the regular version of its app. Uber employees could create a geofence targeting a police station so anyone in or near the building would see the Greyball version of the app, which Uber sometimes called Fake View, the documents show. It banned riders it suspected were government employees.

As Danish transport authorities began an investigation of Uber in January 2015, Uber strategized to impose one such digital shield around its activities, changing how its app behaved near government facilities, according to an internal email saying, “Blackout geofences around main police stations.”

The documents show Greyball was a preferred response mechanism for areas where Uber was alleged to be operating outside existing laws or regulations. As Uber brainstormed ways to dodge authorities in Italy, Spain, the Netherlands and Belgium, executives discussed Greyball as a way to avoid detection.

“It feels to me like greyballing is better than banning, as the greyball user is likely to think that there’s just no supply out there (as opposed to being banned, or not seeing the view at all),” Uber’s Pierre-Dimitri Gore-Coty, then Western Europe regional general manager, wrote in an email in October 2014.

Spurgeon, speaking on behalf of Kalanick, said the CEO never authorized or directed Greyball to be used “for any illegal purpose.”

“The program was designed and used to protect Uber drivers from harassment and assault from taxi drivers—an unfortunate occurrence during the early days of Uber,” she wrote. “Government regulators were aware of the harassment and assaults Uber drivers suffered at the hands of taxi drivers, and the program was meant to try and protect Uber’s drivers. Notably, neither Mr. Kalanick nor anyone else at Uber has ever been accused of or charged with any offense related to Greyball by any enforcement agency.”

Spurgeon further characterized the resistance to Uber as it challenged the taxi industry in many important markets, saying: “To do this required a change of the status quo, as Uber became a serious competitor in an industry where competition had been historically outlawed. As a natural and foreseeable result, entrenched industry interests all over the world fought to prevent the much-needed development of the transportation industry.”

In Germany, a Munich official in 2014 had managed to ride with several Uber drivers, whom the company then expected would receive sternly worded letters from authorities, as other drivers had received at the time, according to the documents. The letters accused Uber drivers of transporting passengers without the necessary paperwork.

Uber then sought to prevent the Munich official from riding with any more drivers.

“He drove with 4 other drivers before we were able to Greyball/ban,” said the September 2014 email from Cornelius Schmahl, an Uber operations manager.

Schmahl, in response to a Post request for comment, replied with an image showing a single sentence. It was a quote sometimes misattributed to Thomas Jefferson: “If a law is unjust, a man is not only right to disobey it, he is obligated to do so.”

Uber used another tactic during a crackdown by authorities in Brussels in January 2015. The company, which had received a tip that an enforcement action was coming, learned that authorities were using people that Uber described as “mystery shoppers” to order rides with the intention of impounding the vehicles when drivers arrived.

Faced with this threat, Uber had employees sign up and pose as mystery shoppers — with the intention of snarling the operation. It blocked newly signed up users from ordering cars. It used geofencing to screen rides in the area where the crackdown was taking place. And it told employees to advise drivers to circle around or claim to be stuck in traffic rather than fulfilling ride requests deemed suspicious.

Uber employees planned to watch all of this play out on its “Heaven” view computer system that allowed them to watch trip activity across an area in real time, documents show.

Employees sometimes had reservations about Uber’s tactics.

“Of course, it gave pause,” said the former Uber lawyer in Europe who spoke on condition of anonymity. “But what Travis was saying was, ‘Do something and ask for forgiveness later.’ ”

U.S. prosecutors launched an investigation into Greyball after its disclosure by the New York Times in 2017 but have brought no charges.

Some Uber employees paid a price for their alleged efforts to circumvent regulators. Gore-Coty and Simphal were taken into custody in 2015. They were later convicted of complicity in operating an illegal transportation service and fined, but avoided jail time.

Gore-Coty, who is still an executive for Uber, said in a recent statement: “I was young and inexperienced and too often took direction from superiors with questionable ethics. While I believe just as deeply in Uber’s potential to create positive change as I did on day one, I regret some of the tactics used to get regulatory reform for ridesharing in the early days.”

In another case revealed by the Uber Files, de Kievit emailed the company leadership on April 10, 2015, to say he had been arrested in the Amsterdam office. He also said that Dutch authorities had asked him whether he had ordered equipment disconnected and told him he was being charged with obstruction of justice.

Two Dutch government officials, a prosecutor and a transport law enforcement official, recently confirmed that an Uber employee was arrested that month, though they declined to name the person. The prosecutor said the case was settled.

One of the former Uber executives said, reflecting on that era, “It was like a religion inside the company that we had to beat taxi and we had to beat other ride-share competitors, whatever it cost.”

Hazelbaker, the Uber spokeswoman, said the company has not used Heaven or Greyball since 2017 and now works cooperatively with authorities worldwide.

Raid dilemma

During a different raid, in Paris on July 6, 2015, Uber employees faced an internal battle: Comply or obstruct?

Paris executive Simphal wrote to colleagues saying that local authorities had arrived and that they wanted access to computers. MacGann, the lobbyist, replied by text that the Paris staff should play dumb as Uber centrally cut access to device after device.

But one escaped their reach — that of Gore-Coty, Uber’s general manager for Western Europe.

“F--- it seems Pierre’s laptop was not KS,” Simphal wrote, referring to the kill switch.

He instructed Gore-Coty to try to close an open browser tab that could provide access to Uber’s systems, according to the documents.

“But lawyers are saying that the moment we obstruct they will take us and staff into custody,” Simphal wrote to colleagues as the search continued. “They have full access right now on Pierre’s computer and are browsing through everything. Should we continue getting them full access? Or block knowing it means custody and being charged with obstruction?”

Internal communications suggest Uber wanted to give the appearance of complying. “I would give them access to the computer but in the background we cut access” to online systems, de Kievit responded by text message.

Asim Ghafoor is a Dawn board member and a US civil rights attorney who previously served as a lawyer to slain journalist Jamal Khashoggi. (photo: Dawn/Middle East Eye)

Asim Ghafoor is a Dawn board member and a US civil rights attorney who previously served as a lawyer to slain journalist Jamal Khashoggi. (photo: Dawn/Middle East Eye)

Dawn says the UAE detained its board member Asim Ghafoor on politically motivated in absentia conviction

Dawn said in a statement on Friday that Ghafoor, who sits on the group's board of directors, was arrested on Thursday at Dubai airport en route to Istanbul to attend a family wedding.

The rights group said the Virginia-based attorney is being held "on what appears to be a politically motivated in absentia conviction".

"Detaining Ghafoor on the basis of an in absentia conviction without providing him any information, notice, or opportunity to defend himself against is a flagrant violation of his due process rights," said Sarah Leah Whitson, Dawn's executive director.

"Whatever trumped up legal pretext the UAE has cooked up for detaining Ghafoor, it smacks of politically motivated revenge for his association with Khashoggi and DAWN."

A senior US administration official, when asked by reporters about the detention, said the United States was aware of it but could not say whether President Joe Biden planned to raise the issue in bilateral talks with UAE President Mohamed bin Zayed on the sidelines of an Arab summit in Saudi Arabia.

"Certainly I think we have points on that about the importance of consular access and everything else," the official said, according to Reuters, adding "there's no indication that it has anything to do with the Khashoggi issue".

Saudi journalist Khashoggi was killed by Saudi agents in 2018 at the kingdom's Istanbul consulate in an operation that US intelligence says was approved by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The prince has repeatedly denied involvement.

Lost contact

According to Dawn, Ghafoor, who had also acted as a lawyer to Khashoggi's fiancee, Hatic Cengiz, sent a text message early on Thursday saying that two plainclothes UAE security agents had approached him at the airport while he waited for his flight.

The security agents told Ghafoor they needed to take him to Abu Dhabi "to clear a case against him".

He was then transported to the capital in a police wagon, Dawn said, adding that it had lost contact with him after he sent a photo of himself in the vehicle.

The rights group urged the Biden administration to secure Ghafoor's release, adding that a senior State Department official had given an assurance that they were working to resolve the matter.

It cited US consular officials, who say they have met the civil rights attorney following his detention, as confirming that Ghafoor is being held in a Criminal Investigative Division detention facility in Abu Dhabi on charges related to an in absentia conviction for money laundering

Ghafoor stated he had no knowledge of any legal matter against him, Dawn said.

Biden has said he would raise human rights during his trip to Saudi Arabia, in which he met the UAE president.

Rights groups say the UAE has jailed hundreds of activists, academics and lawyers in unfair trials on broad charges.

The UAE has rejected such accusations as baseless and says it is committed to human rights under the country's charters.

An investigation by US lawmakers found cryptomining companies use as much energy as nearly every home in Houston, Texas. (photo: Stephen Shaver/REX/Shutterstock)

An investigation by US lawmakers found cryptomining companies use as much energy as nearly every home in Houston, Texas. (photo: Stephen Shaver/REX/Shutterstock)

An investigation revealed that companies use enough energy to power Houston, and contribute to growing carbon emissions

Cryptomining is a highly energy intensive process involving the use of specialized computers running constantly to solve complex math problems in order to create new virtual coins.

Energy use in the industry is greater than that of entire countries. The US has become the center of cryptomining after it was banned in China. More than a third of the global computing power dedicated to mining bitcoin, the largest cryptocurrency, comes from the US, Senator Elizabeth Warren and five other Democrats reported in a letter to the Environmental Protection Agency.

“The results of our investigation … are disturbing … revealing that cryptominers are large energy users that account for a significant – and rapidly growing – amount of carbon emissions,” the letter states. “It is imperative that your agencies work together to address the lack of information about cryptomining’s energy use and environmental impacts.”

The congressional Democrats have asked the EPA and the Department of Energy to require cryptominers to disclose emissions and energy use, noting that regulators know little about the full environmental impact of the industry.

The lawmakers solicited information from seven of the largest US cryptomining companies, including Stronghold, Greenidge, Bit Digital, Bitfury, Riot, BitDeer and Marathon, about their energy sources and consumption and the climate impacts of their operations. The data revealed that the industry is using a substantial amount of electricity, ramping up production and creating significant carbon emissions at a time when the US needs to drastically reduce emissions to combat the climate crisis.

Emissions data from three companies, Bit Digital, Greenidge and Stronghold, indicated their operations create 1.6m tons of CO2 annually, an amount produced by nearly 360,000 cars. Their environmental impact is significant despite industry claims about clean energy use and climate commitments, the lawmakers wrote.

“Bitcoin miners are using huge quantities of electricity that could be used for other priority end uses that contribute to our electrification and climate goals, such as replacing home furnaces with heat pumps,” the letter states.

“The current energy use of cryptomining is resulting in large amounts of carbon emissions and other adverse air quality impacts, as well as impacts to the electric grid.”

The power demands of the industry are also coming at a cost to consumers, the letter states, citing a study that found cryptomining operations in upstate New York led to a rise in electric bills by roughly $165m for small businesses and $79m for individuals.

In Texas, which has become a cryptomining hub, the industry is expected to continue to expand significantly in the coming years, increasing the amount of electrical load to nearly a third of the grid’s current maximum capacity over the next four years and straining the system, according to a report from the Verge.

“The more crypto mining that comes into the state, the higher the residents should expect the electricity prices to become,” Eric Hittinger, a professor at Rochester Institute of Technology, told the outlet.

The cryptocurrency market has crashed in recent months, dropping in value from more than $3tn in November 2021 to less than $1tn.

WALL STREET ON PARADE is a newsletter that has offered these articles about the CRYPTO industry:

Over 1,600 of the Brightest Scientific Minds in Technology Have Signed a Letter Calling Both Crypto and Blockchain a Sham

As Bitcoin Crashes 34 Percent in a Week, U.S. Congressman Ted Budd Pushes Bank Regulator to Approve More Crypto National Bank Charters

As the Speeding Crypto Train Crashes, Scientific and Engineering Experts Tell Congress that Both Crypto and Blockchain Were a Sham from the Beginning

After Crypto Money Piled into Campaign Coffers of Senators Lummis and Gillibrand, They Introduced a Sweetheart Legislative Bill for Crypto

Crypto Billionaire Sam Bankman-Fried Is Dangling $1 Billion in Political Donations; But He Wants Dangerous Crypto Derivatives Trading in Return

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.