Dear Marc,

It was my pleasure to contribute. In a world awash in lies, RSN is a lighthouse beacon in a hazardous and stormy sea.

Keep up the good work.

Bruce,

RSN Reader-Supporter

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

New negotiations would extend Trump’s legacy in the Middle East with a fresh Abraham Accords.

The Trump administration’s solution, spearheaded by Donald Trump’s senior adviser and son-in-law Jared Kushner, was to cut the Palestinians out of the question and organize a deal between Israel and its Arab neighbors around financial, military, and surveillance technology cooperation. The Abraham Accords were signed on September 15, 2020.

Kushner’s depiction of the plan was blunt. “One of the reasons the Arab-Israeli conflict persisted for so long was the myth that it could be solved only after Israel and the Palestinians resolved their differences,” Kushner wrote last year. “That was never true. The Abraham Accords exposed the conflict as nothing more than a real-estate dispute between Israelis and Palestinians that need not hold up Israel’s relations with the broader Arab world.”

That cooperation has continued, as Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has given Kushner’s investment fund some $2 billion and greenlit the financing of Israeli projects with it. Now, the Biden administration is moving swiftly to cement and extend Kushner’s deal, another nail in the coffin of Joe Biden’s campaign trail promise to make MBS a “pariah” due to his role in the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi.

Earlier this week, Axios reported that the U.S. was mediating negotiations between the Saudis, Israelis, and Egyptians for normalization of relations, following a secret meeting by CIA Director William Burns with MBS in April. The deal would hinge on the transfer of two Egyptian islands to Israel, a controversial course of action that in the past has drawn large protests from Egyptians. And, pressured by rising gas prices, Biden reportedly plans to meet with MBS later this year.

In another indication of the changing tides, the National Security Council convened a Deputies Committee meeting involving senior administration officials last week to discuss U.S. policy toward the Middle East, according to a U.S. intelligence office and a source close to the administration who required anonymity to talk about sensitive matters. (The NSC did not respond to a request for comment.) After that meeting, a source close to the administration expressed frustration at the lack of focus on human rights within that policy discussion.

While advocates of the Trump administration deal described the post-Abraham Accord framework as a peace agreement, experts warn that it only makes peace among authoritarian rulers, not with the general Arab public, for whom normalization of relations between Saudi Arabia and Israel absent meaningful rights for Palestinians remains intensely unpopular. Sarah Leah Whitson, executive director of Democracy in the Arab World Now, told The Intercept, “Normalization? What’s that looking like? An apartheid government signing a deal with unelected tyrants in the region? What kind of normal is that?”

In a region dominated by unelected autocrats, the will of ordinary residents is often disregarded. “The standing assessment is that the Saudi population does not support, but they do not have a voice,” the U.S. intelligence official said.

The meeting is one of several recent signs of quiet plans by the Biden administration to normalize relations with Middle East authoritarians in a regional grand bargain that extends Trump’s Abraham Accords. Last week, Saudi deputy defense minister Khalid bin Salman — brother of the crown prince — and Israeli defense minister Benny Gantz were in Washington, prompting speculation that the two had met. During a press briefing Thursday, Pentagon press secretary John Kirby said that “whether they’re meeting on the sidelines because they’re both in D.C. at the same time, I think you’d have to talk to either one of them.”

Given the unpopularity of these sorts of normalization schemes, one way to entice regional leaders is with promises of U.S. security guarantees — agreements by which the U.S. is required to provide a military response to attacks against regional partners enemies, like when the Houthis fired ballistic missiles at the United Arab Emirates earlier this year. But experts warn that such agreements will inflame regional tensions and make war more likely, particularly with Iran.

“The critical question is what’s in it for the United States?” said Trita Parsi, executive vice president of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, in an interview. If security guarantees came to pass, it would “significantly increase the risk of America getting dragged into war. It also increases the recklessness of America’s partners in the Middle East. They’re disincentivized from seeking reasonable diplomatic solutions and incentivized to pursue reckless policies with the impression that the United States will fix it for them at the end of the day.”

“The basis for this so-called peace is their common enmity with Iran. As such, for the peace to last, the enmity with Iran must last. The agreement reduces tensions between Saudi and Israel while cementing enmity with Iran. That is not a peace agreement.”

Mourners in Uvalde, Texas. (photo: Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images)

Mourners in Uvalde, Texas. (photo: Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images)

“They will get to go home to their family and mine will never come home again,” said the father of one child killed.

“While those babies were in there dying, they stood there with their thumbs in their asses trying to figure out what to do,” said Roger Garza, a friend of the family of teacher Irma Garcia, who was killed by the gunman as she tried to shield her fourth-grade students.

“I mean don’t we pay them to rush in and protect people? Somebody needs to be held accountable for this,” Garza told The Daily Beast.

Tragically, Irma’s husband, Joe Garcia, died of a heart attack a day after the shooting. Garza, who worked with Joe Garcia, believes Joe died of a broken heart, as does the rest of the family.

“I went to mass with Joe and Irma every single Sunday and they made me a better person,” Garza said. “Peter needs to answer for his actions and show up and talk to us,” he said, referring to Peter Arradondo, the chief of the Uvalde Consolidated ISD Police Department who was the initial incident commander on Tuesday as the murders were taking place. The Daily Beast has made numerous attempts to contact Arradondo but have been unable to reach him. Neither has anyone else in this community who is seeking answers.

“I know they were scared but so were those babies,” said Suzie Morales, who used to work at Robb Elementary School and knew both of the adult victims very well. “Line up and go in there and shoot the bad guy.”

Morales and Garza’s comments come after revelations Friday that even the most basic of protocols for an active shooter situation at the school wasn’t followed. The director of the Texas Department of Safety, Steven McCraw, admitted at a news conference Friday that authorities made “the wrong decision” and delayed confronting the gunman, leaving the children at his mercy for more than 40 minutes, until tactical units finally shot him. In another devastating admission, McCraw said more than a dozen police officers were actually standing in a school hallway even as desperate 911 calls were made from the besieged classroom.

“We were waiting outside and yelling about how we wanted to go in and storm the classroom,” said Javier Cazares, whose fourth-grade daughter, Jacklyn Cazares, was killed in the attack. “I came running and the police were in a panic trying to figure out what to do. Now we know children, including my daughter, were dying in there. That is what hurts. Knowing they could have maybe protected her and those other kids.”

Cazares wants to know why they didn’t do anything; it is a question that everyone here is asking.

“While those children sat in there with this madman, as many as 19 officers had to think about what to do,” said Ignacio Perez, who was doing his best to comfort Cazares. “I promise you these parents had a plan and were ready to act on it. Where was the bravery? In those kids. That is where it was.”

Equally baffling to families is why Chief Arradondo wasn’t able to use some sort of master key to open the door of the classroom after discovering that it had been locked. McCraw told reporters on Friday that Border Patrol Agents had to secure a key from a janitor before being able to access the classrooms.

“I feel like they are setting this up to have law enforcement walk away like heroes and some of them are,” said Garza. “But the rest who didn’t do anything are nothing more than cowards. The parents were braver than that and they at least had an idea of what to do.”

Cazares wants answers and no more excuses.

“I appreciate them at least telling us what happened, knowing that it would make us even more angry,” he said. “I just want to know that my baby girl didn’t die while they stood there and did nothing. I mean nothing but think.”

“Why did they wait so long?” Cazares said. “They will get to go home to their family and mine will never come home again.”

Amid the growing outrage over the botched police response, authorities in Uvalde have reportedly called in reinforcements from around the state to protect the local officers from potential threats.

The additional cops, from various agencies in other jurisdictions, will supplement Uvalde’s ranks for an unspecified period, and will also provide security for the mayor, officials with the Texas Police Chiefs Association told CBS DFW.

In the immediate aftermath of the May 24 massacre at Robb Elementary, Gov. Greg Abbott lauded the police response, insisting that officers had acted heroically and saved numerous lives. But he lashed out angrily when a different narrative later emerged, saying he was “livid” over having been “misled.” Federal agents on the scene said no one seemed to be in charge, and at one point, agonized parents waiting outside considered rushing the school themselves.

One Uvalde cop claimed there “was almost a mutiny,” telling People magazine that he and his colleagues “felt like cowards” for not storming the building earlier.

“It was the most frustrating situation of my entire career,” the unnamed officer said, adding, “It felt cowardly to stand off and let this punk, this kid, this 18-year-old asshole just go in and do whatever he wanted to do. There was a lot of arguing, a lot of cussing, a lot of people who were saying that we should just say fuck it and go in, but then what? We needed to have a plan, and the commander didn’t have a plan.”

In an interview Friday afternoon, one Robb Elementary teacher who survived the massacre told The Daily Beast that she’s focusing her blame specifically on the shooter, identified by authorities as 18-year-old Salvador Ramos.

“The only person I blame is that person that came into my school and killed my friends,” Nicole Ogburn said. “That’s the only person I am going to blame, because mistakes will be made in every panic situation.”

Ogburn, who was born in Uvalde and attended Robb Elementary, as did her own two kids, said she’s feeling protective of her hometown as its police force is lambasted by the press and on social media.

“Quit bashing and putting down others, because first and foremost, they’re just trying to put blame on somebody,” Ogburn said. “And the one person I blame is that young man, and I will not say his name because he does not deserve to be remembered. And he is. He’s gonna be remembered, his name is out there, his face is out there. But I will not have his name come out of my mouth.”

Groups documenting potential war crimes have been conducting interviews at the PTAK Humanitarian Refugee Center in Nadarzyn, Poland. (photo: Karolina Jonderko/WP)

Groups documenting potential war crimes have been conducting interviews at the PTAK Humanitarian Refugee Center in Nadarzyn, Poland. (photo: Karolina Jonderko/WP)

“Help us punish the criminals!”

At first, she was not sure whether it was relevant to share what happened when her 26-year-old son left their home in the Kyiv suburb of Irpin in search of water. “There were others that suffered more,” she explained. “Nobody was killed except for the dog.”

But, with the idea that her testimony could be important, she sat down to recount her ordeal to a researcher with a 46-question form.

Three months since Russia began its assault on Ukraine, efforts to document war crimes committed during the conflict are hurtling ahead, both inside and outside the country.

As Kyiv investigates a mammoth 11,816 suspected incidents, prosecutors in neighboring Poland have gathered more than 1,000 testimonies from refugees like Inna who could act as witnesses.

France has deployed an on-the-ground forensic team with expertise in DNA and ballistics, and Lithuanian experts are scouring territory in eastern Ukraine. Meanwhile, the International Criminal Court, or ICC, last week sent in a 42-member team, the largest such contingent it has ever dispatched.

All together, it amounts to an unprecedented endeavor, experts say, and it’s happening in real time.

In no other conflict has there been such a concerted push to lay the groundwork for potential war-crimes trials from the start, said Philippe Sands, a law professor at University College London who was involved in the case against Gen. Augusto Pinochet, the Chilean dictator.

But the array of investigations — involving more than a dozen countries and a slew of international and human rights organizations — has raised concerns about duplication and overlap. That could result in “tension” between national and international bodies over jurisdiction, according to Sands.

Experts caution, too, that it could be years before any high-level decision-makers are held to account — if they ever are.

“The crucial question, the one that I think we ought to be focusing our attention on, is how do you get to the top table?” Sands said. It’s one thing to sentence a Russian soldier for killing a civilian, as a Ukrainian court did this past week. But establishing provable links between top officials and the horrors that have unfolded in places such as Mariupol and Bucha is difficult and time-consuming.

“This raises the specter of a situation where, years down the line, you’ve prosecuted a number of low-grade soldiers or conscripts for dreadful things,” Sands said. “But the people at the top table, who are truly responsible, got off scot-free.”

In an exhibition center housing more than 5,600 refugees on the outskirts of Warsaw, Inna paused to compose herself as she tearfully described her family’s ordeal in Irpin, while a volunteer from the Polish government’s Pilecki Institute for historical research took notes.

In the first days of the war, the power went out, followed by gas and then water. By March 8, the water situation was desperate and the family had run out of everything they’d stored. Inna’s eldest son left to seek help from a neighbor, but he was brought back by seven or eight Russian soldiers who accused him of spying.

When the family dog, Jimmy, went to greet them, a soldier shot the dog in the face, said Inna, whose last name was withheld for security reasons. “His lower jaw was destroyed,” she said.

The soldiers refused the family’s pleas to put the dog out of its misery, she said. Instead, they went inside and forced her sons and a friend staying with them to strip naked and lie down on the floor. “They were kept on the floor for around two or three hours,” she said. Eventually the soldiers left, after smashing phones and computers. The next day, the family risked the perilous journey out of Irpin, leaving behind Jimmy, whom they couldn’t bring themselves to kill.

“Do you remember what they were dressed in?” asks the volunteer, reading from the questionnaire. “Were they in uniform? Did you notice any special badges or patches.”

“Camouflage,” she answers. She can’t remember more. “Can it help anything?”

The Pilecki Institute’s Lemkin Center is gathering testimony both to serve as an oral history of the war’s atrocities and, if it might relate to a war crime, for referral to Poland’s public prosecutor.

The Polish prosecutor’s office said it has collected “very significant” testimonies from witnesses, alongside other evidence such as photographs and videos. “These activities are ongoing,” the office said, “they are extensive in nature, not a day goes by without us reaching new witnesses.”

Poland is one of 18 countries that have started their own criminal investigations into war crimes in Ukraine, according to Ukraine’s prosecutor general, Iryna Venediktova.

In the United States, where the State Department has asserted that war crimes have been committed by Russian troops in Ukraine, officials have said Washington could tap into its huge intelligence apparatus to assist investigations.

But with so many investigations underway, there is risk of organizations working at cross-purposes.

The U.N. special rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, Morris Tidball-Binz, last week praised the international mobilization but urged countries and organizations to better coordinate.

“Without coordination of responsibilities and of efforts between various bodies, there is a considerable risk of overlap and duplication to the detriment of the effectiveness and efficiency of investigations,” Tidball-Binz said in a news release. “Proper coordination can also prevent the re-traumatisation of victims and witnesses arising from being interviewed multiple times by different investigators, and ensure that interviews fit into the overall investigative strategy.”

To reduce that risk, the European Union is adjusting the mandate of Eurojust — the bloc’s agency for judicial cooperation — to allow it to maintain a bank of shareable evidence, such as satellite images, DNA profiles, and audio and video recordings.

Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine have also signed up to be part of a joint investigative team alongside the ICC, meaning evidence gathered by prosecutors in any of those countries can be shared for national or international prosecutions. Estonia, Latvia, the Czech Republic and Slovakia are also in the process of signing up, according to Venediktova.

That partnership is key to building to what Venediktova describes as a “judicial front” in the war.

But others such as Germany — which is now home to 700,000 Ukrainian refugees and therefore many potential witnesses — are not coordinating directly, Venediktova said.

Always conscious of its own dark history, Germany has emerged as a hub for war-crimes trials in recent years. Using the principle of “universal jurisdiction,” which enables prosecution of crimes committed in other countries, Germany was the first, and so far only, nation to try an official from the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad for crimes against humanity. A second lower-level official was convicted of serving as an accessory. In those cases, trials were possible because the perpetrators had ended up in Germany.

Germany has opened what it calls a “structural investigation” into war crimes in Ukraine, and in April, two former ministers, Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger and Gerhart Baum, lodged a criminal complaint against 33 Russian officials, urging Germany’s prosecutors to investigate them for war crimes.

“We are now urging the prosecutor to come forward very quickly, because the ICC is very slow,” said Baum, formerly minister of interior, noting that the ICC only just announced warrants for three Russian commanders involved in the war in Georgia 14 years ago.

Ukraine is not party to the statute that established the ICC, but its government has accepted the court’s jurisdiction over crimes committed on its territory and the country’s prosecutor general said her office will probably refer some cases to The Hague — whose mandate is to complement, rather than replace, national justice systems.

For Ukraine, the ICC’s involvement helps bolster the image of objectivity, Venediktova said. It also can prosecute cases involving graver charges such as genocide and crimes against humanity — which cover large-scale systematic attacks, rather than individual acts. “What we see in Bucha and Irpin, it’s crimes against humanity,” she said. “That’s why for me their involvement is very important.”

Still, experts say whether any high-level officials end up in court could depend in large part on the political situation in Russia.

While the two former German ministers concede that the chances of Russian perpetrators ending up in Germany is unlikely, they said they hope international warrants might act as a deterrent on the battlefield.

Others disagree. “I don’t think that’s the logic the Russians operate on,” said Andreas Schüller, head of the International Crimes and Accountability program at the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights. Since international sanctions have already restricted where Russian officials can go, international warrants, for now at least, would be symbolic to an extent.

Schüller said his organization, which worked extensively on documenting Syrian war crimes, is still sorting out how to be most useful on Ukraine. But it is still early, he said. What matters for the moment is less who is doing working on what, but that the documentation is happening.

“If you don’t start now, you will not have the opportunity in 10, 20, 30 years to act, if you don’t do your homework,” he said.

While the focus has been on Russian war crimes, rights groups are also working to document potential war crimes on the Ukrainian side, including the treatment of prisoners of war.

For Sands — whose 2016 book, “East West Street,” traces the intellectual origins of the Nuremberg war crimes trials after World War II back to the western Ukrainian city of Lviv — the key to getting more speedily to the “top table” of Russian officials revolves around prosecution of the lesser-known crime of aggression.

The Nuremberg Tribunal considered it to be the “supreme international crime” — the crime of waging the aggressive act itself. That, Sands argues, takes away the more difficult task of proving the intent of leading figures when it comes to atrocities on the battlefield.

Crimes of aggression are not under the jurisdiction of the ICC. So Sands has floated the idea of setting up an international tribunal to cover the crime. Since he wrote about it in a Financial Times column in February, the idea has taken off. On Thursday, the European Parliament voted for the E.U. to act to establish a tribunal.

“As things look right now, what are the chances of snaring one of the top people? No, it doesn’t look likely,” Sands said. But in 1942, people would have said the same thing, he added. “Of course, three years later, you know, Hermann Göring was in the dock at Nuremberg,” he said of the Nazi military leader sentenced to death in 1946 for war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes of aggression.

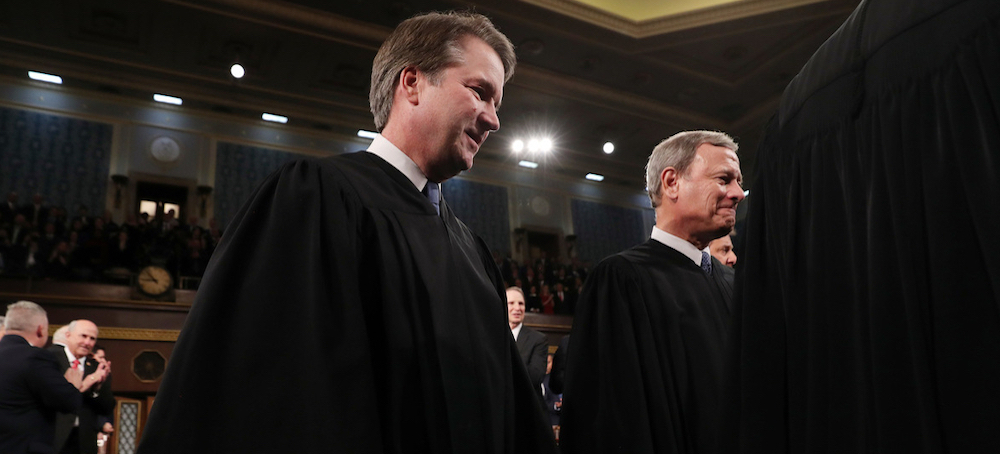

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Embracing the state’s claim that “innocence isn’t enough,” the court destroyed a lifeline for people who received poor lawyering at trial.

The 6-3 decision in Shinn v. Martinez Ramirez was authored by Justice Clarence Thomas, who wrote that Jones and David Martinez Ramirez, another man on Arizona’s death row, should not have been allowed to present new evidence in federal court showing that they had received ineffective assistance of counsel at trial. In Jones’s case, the evidence dismantled the state’s original theory of the crime, prompting U.S. District Judge Timothy Burgess to vacate his conviction. If not for the failures of Jones’s trial attorneys, Burgess wrote in 2018, jurors likely “would not have convicted him of any of the crimes with which he was charged and previously convicted.”

The Supreme Court’s May 23 ruling renders this evidence — and Burgess’s core findings, which were twice upheld by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals — moot. The majority agreed with Arizona’s contention that under the 1996 Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, or AEDPA, which sharply limits federal appeals, the hearing in Jones’s case should never have taken place. “In our dual-sovereign system, federal courts must afford unwavering respect” to trials in state court, Thomas wrote. Federal courts “lack the competence and authority to relitigate a state’s criminal case.”

The decision is a devastating blow to Jones, who has always insisted on his innocence. But it also slams the courthouse door on countless incarcerated people whose lawyers failed them at trial. “The court’s decision will leave many people who were convicted in violation of the Sixth Amendment to face incarceration or even execution without any meaningful chance to vindicate their right to counsel,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in a dissent joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan.

Sotomayor described Thomas’s opinion as “perverse” and “illogical,” in part because it eviscerates the court’s own 2012 ruling in Martinez v. Ryan, another case out of Arizona. That decision created a much-needed remedy for defendants who received poor representation both at trial and in state post-conviction proceedings. Under the stringent rules governing federal appeals, a defendant who fails to challenge their trial lawyer’s performance in state court is forbidden from bringing that evidence to federal court. But Martinez created an exception. It held that if the failure to develop such evidence in state court was due to a post-conviction lawyer’s own ineffectiveness, the defendant should be excused — and allowed to bring an ineffective assistance claim in federal court.

The ruling in Martinez v. Ryan was narrow. Limited to those with “substantial” claims of poor lawyering, which is difficult to prove, it offered a possible path to relief, not a guarantee. Still, it was a rare lifeline to people on death row, many of whom had been represented by lawyers who were overworked, underpaid, and often unqualified. Notably, the 7-2 majority in 2012 included Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito, neither of whom raised concerns at the time over how the decision might be reconciled with AEDPA’s procedural hurdles.

Yet both justices joined Thomas, one of two dissenters in Martinez, in weaponizing AEDPA to gut the 10-year-old ruling — an emblem of the court’s newly aggressive indifference to its own legal precedent. Law professor Leah Litman, an expert on AEDPA and constitutional law, compared the decision to the leaked draft opinion in Dobbs v. Mississippi, which stands to overturn Roe v. Wade. Both, she wrote in an article for Slate, make clear “that the court’s conservative supermajority is hellbent on smashing and grabbing precedent and constitutional rights no matter the consequences.”

Perverse and Illogical

Jones was sent to death row for the rape and murder of his girlfriend’s 4-year-old child, Rachel Gray. The child arrived at a Tucson hospital early in the morning on May 2, 1994, and was declared dead on arrival. An autopsy showed a blow to her abdomen, which ruptured her small intestine, developing into a fatal case of peritonitis. Investigators seized on Jones without considering how or when the child sustained the injury. At trial, prosecutors relied on circumstantial evidence and dubious forensic testimony to convince jurors that Jones had repeatedly assaulted Rachel the day before she died. His trial attorneys called no witnesses at the guilt phase aside from his 12-year-old daughter.

Jones’s case seemed like the perfect example of what the Martinez ruling was designed to address. Not only had his trial lawyers failed to investigate the medical evidence that provided the basis for his conviction, but his post-conviction attorney also failed to do the same. At Jones’s evidentiary hearing in 2017, medical experts debunked the narrow timeframe during which the state claimed Jones had assaulted Rachel, showing that her fatal injury could not have developed so quickly. A slew of additional witnesses shed light on shocking investigative failures by the Pima County Sheriff’s Department.

But in Thomas’s view, this hearing was nothing more than an “improper burden imposed on the states” by the Martinez decision. The “sprawling” seven-day hearing “included testimony from no fewer than 10 witnesses, including defense trial counsel, defense post-conviction counsel, the lead investigating detective, three forensic pathologists,” and more, he wrote. The hearing covered “virtually every disputed issue in the case, including the timing of Rachel Gray’s injuries and her cause of death. This wholesale relitigation of Jones’ guilt is plainly not what Martinez envisioned.”

In her dissent, Sotomayor pointed out what should have been obvious to the court that handed down the Martinez ruling just a decade ago: Such a thorough hearing “was necessary only because trial counsel failed to present any of that evidence during the guilt phase of Jones’ capital case,” she wrote. “The District Court’s hearing was wide-ranging precisely because the breakdown of the adversarial system in Jones’ case was so egregious.”

The notion that Jones’s hearing was a misapplication of Martinez only really made sense to those who believed that the ruling should be a remedy on paper alone. This had been at the heart of Arizona’s argument for years; prosecutors insisted that even if Martinez allowed Jones to use new evidence to bring forth a claim that his trial lawyers had been ineffective, he was not actually allowed to use that evidence to prove it.

The confusion over such logic was on display at the oral argument in Jones’s case before a 9th Circuit panel in 2019, during which the judges seemed stupefied. When they asked why a judge would allow a claim to be brought if they couldn’t consider the evidence, Arizona Assistant Attorney General Myles Braccio replied that a judge could just look to the state court record. “But that doesn’t make sense if the claim wasn’t developed in state court,” one judge replied. Another called it a “Catch-22.”

At the Supreme Court argument in December, the conservative justices clearly grasped the problem. Thomas kicked off the questions. Why give a defendant the chance to bring a previously barred claim of ineffective assistance of counsel only to forbid them from presenting the evidence to support it? he asked. “It seems pretty worthless.” Justice Brett Kavanaugh noted that in Martinez, the court “obviously carefully crafted an opinion to give you the right to raise an ineffective assistance claim, to make sure it’s considered at least once, and this would really gut that in a lot of cases.”

In the end, this is precisely what the justices decided to do. “While we agree that any such … hearing would serve no purpose,” Thomas wrote, “that is a reason to dispense with Martinez hearings altogether.” In a nod to Arizona’s repeated contention at oral argument that “innocence isn’t enough” for Jones to prevail in this case, Thomas cited the court’s decision in Herrera v. Collins, which famously held that there was no constitutional prohibition against executing someone for a crime they did not commit. In a case like Jones’s, he wrote, federal intervention is “an affront to the state and its citizens who returned a verdict of guilt after considering the evidence before them.”

A Lot at Stake

I first wrote about Barry Jones in 2017, in advance of the evidentiary hearing in Tucson. At that time, there was no reason to suspect that Martinez was in peril. In fact, the Supreme Court had extended the ruling to apply to defendants in Texas and other states whose appellate procedures differed from Arizona’s. Although lawyers for incarcerated people were working hard to use Martinez to win relief for their clients, few had effectively availed themselves of the decision.

Jones was about to be an exception. In the years since his 1995 trial, the central evidence against him had largely fallen apart. Even the pathologist who conducted Rachel’s autopsy and took the stand against Jones at trial, Dr. John Howard, seemed to acknowledge that his testimony had been misleading. At the trial of Jones’s girlfriend, Angela Gray, who was sentenced to eight years in prison for her failure to take her daughter to the hospital the night before she died, Howard estimated that Rachel’s fatal intestinal wound was “most consistent” with occurring 24 hours or longer before her death. Yet at Jones’s subsequent trial, Howard said the injury was consistent with being inflicted 12 hours before Rachel’s estimated time of death — precisely the window the state used to implicate Jones.

Jones’s lead trial attorney, Sean Bruner, failed to confront Howard with the discrepancy. “I could have cross-examined him on that 24-hour/12-hour thing, and I missed that,” Bruner told me in 2017. For his own part, Howard explained in an affidavit that he only answered the questions he was asked on the stand. If trial attorneys had asked whether Rachel’s abdominal injury could have happened “more than 24 hours before her death, I would have answered the question in the affirmative.”

Burgess, the judge, seemed disturbed by Howard’s willingness to change his opinions from one moment to the next. “You understand that in these trials there was a lot at stake, right?” he asked at the 2017 hearing. Yet Howard continued to shift his analysis on the stand, saying that the abdominal injury could have taken place “a few hours, typical of a day or the same day as death,” while adding that “it could be just a few hours, it could be 24 hours, it could potentially, or at least in theory, be longer.”

The evidence that Jones had raped Rachel also failed to stand up to scrutiny. Although Howard said that injuries to the child’s vagina had been inflicted at the same time as her abdominal trauma, experts who reviewed the case for Jones’s federal defenders flatly disputed this. Dr. Janice Ophoven, a renowned pediatric pathologist, testified that the injury was likely “weeks old.” Another pathologist said that he would not even put it in the same context as the abdominal injury: “It’s not in the death timeline.”

The vaginal injury was key to law enforcement’s original suspicion of Jones. He had been the one to drop off Rachel and her mother at the hospital, where Pima County Sheriff’s Detective Sonia Pesqueira examined the child herself, finding her covered in bruises, with blood in her underwear. Later that morning, before an autopsy had been conducted, Pesqueira aggressively interrogated Jones, accusing him of killing Rachel and falsely claiming that his own daughter had accused him of hurting the child. Yet she neglected to collect key evidence that could have connected the child’s injuries to the perpetrator, such as the clothes she was wearing the previous day. When part of a pair of underwear was tested for DNA years later, there was nothing that matched Jones.

At the evidentiary hearing, prosecutors insisted that Pesqueira had “followed the evidence of guilt for Rachel’s injuries, and that road led directly to Jones.” Besides, they said, her investigation was irrelevant since the hearing was limited only to the question of whether Jones’s defense attorneys had been ineffective. “Law enforcement has nothing to do with this case,” Braccio said.

But Burgess disagreed. “The evidentiary hearing in this case has demonstrated that the police investigation was colored by a rush to judgment and a lack of due diligence,” he wrote. “Effective counsel would have brought this to the jury’s attention.” For example, there were numerous alternate suspects at the Desert Vista Trailer Park in Tucson where Gray and Jones lived. Pesqueira had no answer for why she neglected to investigate any of them — or why she ignored evidence that Gray herself had physically abused her children.

But the most important witnesses were the experts who showed that Rachel’s fatal injury could never have led to her death so quickly. One was an independent pathologist who agreed back in 1994 to study the microscopic slides from Rachel’s autopsy but never received the materials from Jones’s trial attorneys. “Rachel’s small bowel laceration was not inflicted on May 1, 1994,” he wrote in a 2017 affidavit, and “Jones’s jury was misled to believe otherwise.” Another doctor testified that there were “no reported cases in medical literature in which this type of injury has resulted in death in less than 48 hours.”

Ophoven, the pediatric pathologist, pointed to the physical evidence as well as Rachel’s symptoms to show how the injury to Rachel’s small intestine had become deadly over time. Whatever caused the injury, Ophoven said, the subsequent inflammation typically associated with such abdominal trauma had spread slowly to her abdominal cavity, making it harder to detect. One neighbor had told investigators that Rachel looked gray and unwell on April 30 — two days before her death, which was an important clue. “The gray color is kind of specific to this kind of process,” Ophoven testified. Yet Pesqueira admitted that she dismissed the statement at the time. “I thought she was giving me the wrong day,” she testified.

In his 91-page order, Burgess wrote that such testimony could well have convinced a jury not to convict Jones of murder. His lawyers’ investigative failures “pervaded the entire evidentiary picture presented at trial.” But today, as far as the Supreme Court is concerned, this partial and distorted picture is the only one that matters. The evidence presented at the hearing has been completely swept away.

Killing an Innocent Man

On the day after the Supreme Court’s ruling, Jones’s longtime attorney, Arizona Assistant Federal Defender Cary Sandman, was still grappling with what had happened. Although he’d swiftly assembled his legal team to discuss next steps, it would take another day for him to bring himself to read the decision. At 70, Sandman had hoped to welcome Jones to the outside world as one of the final capstones to a long legal career. Instead, he went to see Jones at the Arizona penitentiary where he remains with no clear way out.

The court’s decision fulfilled Sandman’s worst fears. “There was no reason to take that case unless they were gonna basically neuter Martinez,” he said. After the oral argument in December, Sandman echoed what legal observers were saying: The justices had asked all the right questions. But in the end, this only made the ruling more cruel. “The majority’s Kafkaesque decision will condemn many to wrongful imprisonment, or worse, death,” Sandman said. “All in the name of state’s rights.”

For attorney Bob Loeb, who argued for Jones before the court, Thomas’s one-paragraph summary of the facts in the case was infuriating to read. “On May 1, 1994, Barry Lee Jones repeatedly beat his girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter,” it began. Never mind that this time frame and the medical claims it relied on had been repeatedly debunked. In a statement, Loeb wrote that the decision was “tragic for Barry Jones, who remains in prison notwithstanding evidence which the district court determined undercut the murder charge against him — evidence showing that the conviction was based on assertions that were scientifically untrue.”

If there is any hope for Jones going forward, it could lie with the office that sent him to death row in the first place. In the years I’ve reported on Jones’s case, the Pima County Attorney’s Office, which is home to a Conviction and Sentencing Integrity Unit, has repeatedly sidestepped inquiries as to when the office might reinvestigate the conviction. In an email last year, the head of the unit, Jack Chin, wrote that while his office “has a general policy against the death penalty, and all capital sentences which are in our jurisdiction and responsibility will be looked at closely and carefully,” he had “not spent a great deal of time” looking at Jones’s case. Chin did not respond to emails following the Supreme Court’s ruling.

In the meantime, Jones is starting to see neighbors marched to the execution chamber. After an eight-year hiatus on executions, the state killed 66-year-old Clarence Dixon by lethal injection earlier this month, struggling for 25 minutes to find a vein. Next month Arizona plans to execute another man convicted in Tucson who insists upon his innocence. In an email shared by Sandman, Jones wrote that he was “still processing the news” about the Supreme Court’s ruling. “Putting on a brave face, but underneath I am as scared as I have ever been,” he wrote. “If they can put me back on death row, and they did, then there ain’t a doubt in my mind that they could justify killing an innocent man.”

Donald Trump. (photo: Erin Schaff/NYT/Redux)

Donald Trump. (photo: Erin Schaff/NYT/Redux)

The Jan. 6 committee says the emails prove that John Eastman’s infamous coup memo was “the culmination of a monthslong effort” to overturn the election.

John Eastman, the author of the now-infamous memo that plotted how Vice President Mike Pence and congressional Republicans could try to block President Biden’s election certification on Jan. 6, admitted in a private email weeks earlier that the plot was “dead on arrival” if state legislatures didn’t officially approve the “alternate electors” for Trump. When they refused to do so, he reversed course and encouraged Trump’s team to try to block Congress from certifying Biden’s win even without that shred of legal justification, leading to the chaos at the Capitol on Jan. 6.

The email was made public late Thursday night in a court filing by the House Select Committee investigating Jan. 6, and offers further proof that Eastman’s Jan. 6 coup memo wasn’t a one-off but rather, as the committee puts it in its court filing, “the culmination of a monthslong effort to corruptly subvert the results of the 2020 election.”

“Most prominently, new evidence produced by Dr. Eastman illustrates his contemporaneous involvement with the submission of the fraudulent slates of Trump electors that were the basis for his legal arguments regarding the vice president,” the committee’s attorneys wrote in the 57-page memorandum.

At that time, Eastman and Trump were trying to pressure GOP-controlled state legislatures in states Trump had lost to say that he’d actually won those states and certify slates of “dueling” Electoral College elector slates for him. That would have created an actual constitutional crisis, with Congress forced to choose which slate to adopt. Republican state lawmakers, governors and secretaries of state refused to go along with this plot at the time, however, depriving Eastman’s plot of the legal legitimacy it needed to have a chance on Jan. 6.

But after that attempt failed, Eastman reversed himself. Trump backers in the swing states that Biden won had gathered and pretended to be electors on the day the states submitted their electors to the Electoral College. Eastman essentially admits in this email that these people were basically just cosplaying at being electors without any actual official approval from their state legislatures—but days later he emailed Trump campaign adviser Boris Epshteyn that “the fact that we have multiple slates of electors demonstrates the uncertainty of either,” and asserted “that should be enough” to pull things off on Jan. 6.

The emails show how ham-handed and legally dubious this effort was—but how easily a future election could be thrown into chaos if even a few more bad actors go along with a similar plot. If Republican legislators had agreed to chuck out their states’ election results and instead try to install Trump electors, or if the GOP governors of some of those states had refused to sign off on the certifications of those elections, that would have given legal pretext for Congress to try to block Biden’s victory, which would have led to an ugly court fight. If Pence had gone along with the plot, it may have failed legally but it would have created vastly more uncertainty and a much higher risk of an actual constitutional crisis.

Trump and his allies are now trying to use the midterm elections to install as many cronies in those key positions as possible, so that by the time the 2024 election comes around, they’re better-positioned to try again if they lose a close election.

Eastman was caught on hidden camera admitting as much last year, saying he was still working with state legislators to try to overturn the 2020 results, months after Biden’s inauguration.

The committee filed the memorandum as part of an attempt to get Eastman to release 600 emails he claims are attorney-client privilege between himself and the Trump campaign. A judge has forced him to release most of his other emails with the team.

The emails show that Eastman knew not only that his plan to try to get then-Vice President Mike Pence to block President Biden’s election certification wasn’t legal—but that he seems to have beenlying when he said he’d seen proof of widespread voting fraud during a speech to Trump supporters on January 6, shortly before a segment of that crowd rioted and overran the U.S. Capitol.

In that speech, Eastman confidently asserted that “dead people voted” and “machines contributed to that fraud,” claims he admitted weeks earlier that he hadn’t seen evidence of.

But in these emails, Eastman admits that he had “no idea” if the Trump campaign had actually compiled real evidence of widespread fraud in all the states they were contesting.

“I haven’t even had a chance to look at that website link I sent—but was told everything is assembled there,” he replied when asked for evidence of fraud to supply to GOP members of Congress. “Is that not the case?”

Flor de Maria Erazo, 49, cries over seeing her son at a detention center. (photo: Fred Ramos/WP)

Flor de Maria Erazo, 49, cries over seeing her son at a detention center. (photo: Fred Ramos/WP)

Police, military and judicial system face pressure to implement mass arrest and incarceration policy, experts say.

It was around 9pm, Gutierrez recalls, and many of his neighbours were soon standing next to him, their hands cinched with the same plastic ties.

“Why are they saying that they want more?” Gutierrez remembers asking himself about the conversations he overheard between the heavily armed members of the Salvadoran military. In total, 21 men including Gutierrez were handed off to the police, the only institution with the power to carry out arrests in El Salvador.

“Just because the state has given them the authority, they think that they can supposedly do whatever they want and no one can say anything,” Gutierrez told Al Jazeera in an interview.

The arrests came amid a sweeping anti-gang crackdown that began in late March in response to a spike in homicides.

President Nayib Bukele and his party have defended their response – including the use of a “state of exception” that suspends certain civil liberties – as necessary and successful in the fight against gang violence, which the Central American country has long grappled with.

But the police, military and judicial system have faced explicit and implicit pressure to implement the government’s mass arrest and incarceration policy, experts say. Sources also told Al Jazeera that police have been tasked with filling an arrests quota, something rights groups say has led to arbitrary detentions and threatens to overwhelm an already overburdened penitentiary system.

‘Order from above’

Police have been told to fill an arrest quota since the start of the state of exception, according to Marvin Reyes, general secretary for the Movement of Workers of the Salvadoran National Police, a police union with roughly 3,000 members nationwide, who said he has received reports from dozens of members of the organisation.

The quota varies depending on the size of the municipality, and has fluctuated throughout the state of exception, Reyes said. The countrywide quota reached as high as 1,000 per day around the end of April, then dropped to about 500 daily arrests across different police sectors, he told Al Jazeera.

Now, there is no daily quota but police must meet a general goal post by the end of the state of exception, he said. The military is also expected to contribute to this quota by identifying people for arrest and then referring them to the police, Reyes said.

The president’s office, the National Police and the ministry of justice and public security did not respond to Al Jazeera’s requests for comment on the quotas. A police spokesperson denied the existence of quotas in a statement to the Reuters news agency this month, saying that such an order is considered a serious offence and urging staff to report it.

As of May 25, the National Police said more than 34,500 people had been arrested for alleged gang ties and other gang-related offences, such as extortion. Bukele has said there are an estimated 70,000 gang members in El Salvador, and on Wednesday, the legislature voted to extend the state of exception for another 30 days to continue the government’s “war” on gangs.

According to Reyes, by the time the state of exception was meant to expire on May 27, police had been told they needed to detain 35,000 people.

But Gutierrez told Al Jazeera he has no gang ties.

He was released less than 24 hours after being detained, he said. When he asked the police officer why he was being detained and investigated for potential gang connections, he said the officer replied: “We have to go through the process, because the order comes from above.”

Reyes said people like Gutierrez who are detained and then released are still included in the police force’s total number of arrests. Arrests should “not be a competition”, but rather should focus on “searching for who is really a criminal”, he added.

Judicial system

Many of the people detained under the state of exception have been charged with “illicit association”, meaning that they are accused of working with a gang or criminal group in some way, according to a report by Human Rights Watch and Salvadoran NGO Cristosal.

As part of the crackdown, legislators also passed a reform to increase penalties for gang-related crimes and reduced the age at which children can be charged for belonging to gangs or “terrorist” groups from 16 to 12.

Yet Reyes said many of the people arrested have not been investigated previously for gang connections. Several families also recently told Al Jazeera that their relatives investigated for this crime have no gang ties.

Judges would usually have discretion to allow these people to wait for their hearings outside of prison, given that cases can take years to weave their way through the Salvadoran justice system.

But the Bukele administration has taken steps to limit judicial independence under the state of exception, and has expressed a clear preference for mass incarceration, said Hector Carrillo, director of access to justice at the Foundation for the Study of Law (FESPAD), a Salvadoran NGO.

Many of the people arrested under the state of exception have been transferred to pre-trial detention while their cases make their way through the system, a process that could take six months but can also be extended by a judge.

A reform passed under the state of exception limits judges from granting alternative measures to pre-trial detention, such as bail or house arrest. Carrillo said the reform is unconstitutional and violates the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, to which El Salvador is a party.

Carrillo said his organisation has not documented an explicit practice of pressuring judges to make certain decisions under the state of exception. But he said the political context in El Salvador sends an implicit message to judges who would contradict Bukele and his party’s policies.

The government “has tried to equate any questioning of its decisions — whether it be from media or civil society — to support of criminal groups,” Carrillo told Al Jazeera. “So if a judge has that in his or her mind at the moment of making a decision in a courtroom, there is no guarantee of the free exercise of justice.”

Another reform passed last year allows the Supreme Court, stacked by Bukele loyalists, to name and transfer judges. When a judge ruled in April that a case lacked evidence to convict 42 gang members for homicide, Bukele called on the Supreme Court to exercise this power to “remove judges complicit with organised crime”.

The court transferred the judge to a new court shortly after. It has also used this power to transfer a judge who rejected a defamation lawsuit filed by a legislator from Bukele’s party and another who granted bail to two members of the past government and ordered another to house arrest.

“When we see public declarations of the president of the republic against judges, that gives us a sense of what judges can be interpreting,” said Carrillo. “There is an open external interference towards the judicial profession.”

Antonio Duran, a judge who was transferred to a different court in September 2021 after speaking out against the Bukele administration, said the lack of independence in the court system during the state of exception is a result of the erosion of independent institutions.

Duran said that process began on May 1 of last year, when members of Bukele’s party assumed a supermajority in El Salvador’s legislative assembly and immediately moved to remove the attorney general and Supreme Court judges.

“The Supreme Court has been co-opted completely, and kidnapped by the executive branch,” Duran told Al Jazeera. “There is no separation of power. It does what the presidential house says.”

One of the reports found evidence EU vessels fished without authorization in the Indian Ocean, where the main catches include skipjack, bigeye and yellowfin (pictured) tuna. (photo: Giordano Cipriani/Getty Images)

One of the reports found evidence EU vessels fished without authorization in the Indian Ocean, where the main catches include skipjack, bigeye and yellowfin (pictured) tuna. (photo: Giordano Cipriani/Getty Images)

Reports handed to EU claim vessels likely to have entered coastal states’ waters where stocks are dwindling

EU purse seine (a type of large net) fishing vessels were present in the waters of Indian Ocean coastal states, where they were likely to have carried out unauthorised catches, and have reported catches in the Chagos archipelago marine protected area and in Mozambique’s exclusive economic zone.

Two investigations were made of fishing in the Indian Ocean, one conducted by the group OceanMind and another by the charity Blue Marine Foundation along with Kroll, the corporate investigation company. The first report found evidence, from the publicly available data published by the EU from its fishing fleet from 2016 to 2020, that EU vessels fished in the region, where the main catches include the skipjack, bigeye and yellowfin tuna species. Blue Marine Foundation subsequently established that the vessels were not authorised.

The second report, by Blue Marine Foundation and Kroll, examined data from ships’ monitoring software, called the automatic identification system (AIS), and found that some vessels in the region had switched it off, which could be an indication of unauthorised fishing.

Populations of tuna are under increasing pressure as industrialised fishing fleets cash in on the growing market for the popular fish. The expansion of tuna fisheries could lead to extinction, scientists have warned.

The latest NGO findings, presented to government representatives at a meeting of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission in Seychelles this week, highlight the problem of illegal, unreported or unregulated (IUU) fishing around the world, and of EU vessels taking catches from the depleting stocks of developing countries.

The analysts also found instances where vessels had “gone dark” – turned off monitoring through the AIS, which transmits a ship’s position and is a safety tool that can also be used to ensure fishers keep within the rules – at key points, suggesting they may have engaged in IUU fishing.

Some EU vessels in the western Indian Ocean went dark for an average of three-quarters of the period from 1 January 2017 to 30 April 2019, according to the Blue Marine Foundation findings.

The Guardian has spoken to a person familiar with the licensing situation, who confirmed EU vessels have had no licences to fish in Somali waters since 2013. Blue Marine Foundation said the Indian authorities also confirmed they had not issued licences to EU vessels.

Anne-France Mattlet, the tuna group director for the EU fishing trade association Europêche, said: “The EU purse seine vessels did not fish in Somalian waters.”

An official for the European Commission said: “The EU has a strict zero tolerance for IUU. In order to fight IUU in the IOTC convention area, the EU has also tabled a proposal to establish a high-sea boarding and inspection scheme, based on the work already done within the IOTC.

“This would be an important tool to control better the fishing activities in the high seas and continue to fight against IUU fishing. We have also tabled a proposal to improve the traditionally weak IOTC compliance process, by putting more emphasis on the categorisation and follow-up to established situations of non-compliance.”

The spokesperson said fishing crews may have valid reasons for switching off their AIS technology, and that the transmission power and signal can vary from place to place.

“[Going dark] does not imply that they fish illegally. The AIS might be switched off under certain circumstances by professional judgment of the master,” the spokesperson said. “The information given by the AIS may not be a complete picture of the situation in the area and of the vessel’s activity.”

Charles Clover, the executive director of Blue Marine Foundation, defended its claims. “The report showing the locations of EU vessels is based on the findings of a study commissioned by Blue Marine Foundation and undertaken by OceanMind – a highly reputable organisation – which in turn was based on publicly available data reported by the EU and published by the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission on its website,” he said.

“This data shows, for example, evidence of fishing on the part of vessels flagged to Spain in the waters of Somalia, in 2017 and 2018, and India, in 2018 and 2019.”

He added: “There is evidence to suggest that some of these fleets are fishing in coastal states’ waters without any kind of authorisation and we call on the European Commission to investigate these instances as a matter of urgency.”

The Guardian also approached the Spanish government for comment.

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.