Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Which is to say, none. The Trump Three are driving the train now, with Alito and Justice Clarence Thomas shoveling the coal.

1) If you had any doubts remaining that Chief Justice John Roberts has completely lost control of the Supreme Court, this draft opinion should allay them permanently. Let's say Roberts didn’t leak the text himself, or arrange for it to be leaked—and I don’t believe this was some gutsy clerk acting alone. Handing the majority opinion to Justice Samuel Alito to write, and expecting Alito to devote himself to half-measures, was a huge and obvious error in judgment. But I would argue that it’s also an indication that Roberts knows even his cosmetic moves toward moderation are doomed, because the carefully engineered conservative majority is as far beyond his control as the House Republican caucus is beyond the control of Kevin McCarthy. The Trump Three are driving the train now, with Alito and Justice Clarence Thomas shoveling the coal. Roberts can devote himself exclusively to crushing voting rights and unleashing corporate money power, the two tent-poles of his career.

2) The Supreme Court already is asking for the FBI to probe how the leak happened and who’s responsible. The political right is howling for someone’s head, hoping against hope that the noise they make will obscure the very real threat Alito poses to the continued relevance of the 14th Amendment. This likely will come to nothing because this leak was clearly authorized.

3) As historian Kevin Kruse pointed out on the electric Twitter machine, it’s a good day to revisit the famous speech the late Senator Edward Kennedy made years ago opposing the nomination of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court.

Robert Bork’s America is a land in which women would be forced into back-alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, school children could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of the government.

Conservatives have never stopped whining about this speech. They blame it for “politicizing the process,” which is historically absurd. (Hi, I’m Abe Fortas. Have we met?) If Kennedy hadn’t made Bork so sad, the argument goes, then Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett wouldn’t have felt it necessary to deceive their asses off before the Senate. Turns out Kennedy was wrong, though. It’s not Robert Bork’s America. It’s Sam Alito’s.

4) And finally, there’s this passage from the leaked opinion that says more than it purports to say.

But the three Justices who authored the controlling opinion “called the contending sides of a national controversy to end their national division” by treating the Court’s decision as the final settlement of the question of the constitutional right to abortion. As has become increasingly apparent in the intervening years, Casey did not achieve that goal. Americans continue to hold passionate and widely divergent views on abortion, and state legislatures have acted accordingly. Some have recently enacted laws allowing abortion, with few restrictions, at all stages of pregnancy. Others have tightly restricted abortion beginning well before viability. And in this case, 26 States have expressly asked this Court to overrule Roe and Casey and allow the States to regulate or prohibit pre-viability abortions.

You know who else "held passionate and widely divergent opinions on abortion"? Michael Griffin, who killed Dr. David Gunn; and Paul Hill, who killed Dr. John Britton; and John Salvi, who killed Shannon Lowney and Lee Ann Nichols; and James Kopp, who killed Dr. Barrett Slepian; and Scott Roeder, who killed Dr. George Tiller; and Robert Dear, who killed Officer Garrett Swasey, Ke'Arre M. Stewart, and Jennifer Markovsky, the latter of whom was accompanying a friend to the clinic. And then there's the champion of them all, Eric Rudolph, who killed Officer Robert Sanderson when Rudolph blew up a clinic in Birmingham, Alabama, and who killed Alice Hawthorne when he blew up Centennial Park during the Atlanta Olympic Games, and who somehow evaded capture for five years, during which time he bombed the clinic in Birmingham.

If we were to expand the search for "passionate and divergent opinions" to include attempted murders, bombings that mercifully killed nobody, the stalking of doctors, and acts of serious vandalism, it would cause this post to run into thousands of words. That would only depress us all further. But I note that, almost immediately after Politico’s scoop posted, Randall Terry, the original anti-choice fanatic, reappeared in front of the Supreme Court to dance and sing and to torment the people who had gathered there in protest. When Scott Roeder killed Dr. George Tiller in church, Terry called the victim a “mass murderer.” I guess that’s a passionate and divergent opinion, for sure.

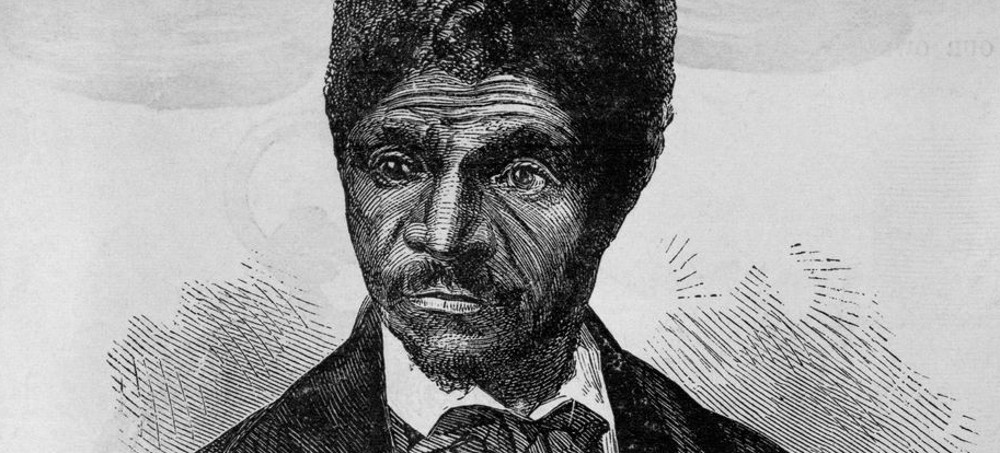

Dred Scott, whom the Supreme Court of the United States described as a being "of an inferior order." (photo: Getty)

Dred Scott, whom the Supreme Court of the United States described as a being "of an inferior order." (photo: Getty)

The Court was the midwife of Jim Crow, the right hand of union busters, and the dead hand of the Confederacy, and is now one of the chief architects of America’s democratic decline.

The historic event was that Politico published an unprecedented leak of a draft majority opinion, by Justice Samuel Alito, which would overrule Roe v. Wade and permit state lawmakers to ban abortion in its entirety in the US. Alito’s draft opinion is not the Court’s final word on this case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, but the leaked opinion is the latest in a long list of signs that Roe may be in its final days.

The other event that also occurred last night is that I sent two tweets. One praised whoever leaked Alito’s opinion for disrupting an institution that, as I have written about many times in many forums, including my first book, has historically been a malign force within the United States. And a second celebrated the leak for the distrust it might foster in such a malign institution.

The former tweet was phrased provocatively, and it attracted some attention from those on the right, including Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX). So let me clarify that I do not advocate arson as a solution to the Republican Party’s capture of the Supreme Court. I metaphorically compared the leak of Alito’s opinion to lighting the Court on fire because, as Chief Justice John Roberts noted in his statement on the leak, the Court has extraordinarily strong norms of confidentiality that it zealously protects.

The fact that someone inside the Court’s very small circle of trust apparently decided to leak a draft opinion is likely to be perceived by the justices, as SCOTUSBlog tweeted out Monday night, as “the gravest, most unforgivable sin.”

To this I say, “good.” If the Court does what Alito proposed in his draft opinion, and overrules Roe v. Wade, that decision will be the culmination of a decades-long effort by Republicans to capture the institution and use it, not just to undercut abortion rights but also to implement an unpopular agenda they cannot implement through the democratic process.

And the Court’s Republican majority hasn’t simply handed the Republican Party substantive policy victories. It is systematically dismantling voting rights protections that make it possible for every voter to have an equal voice, and for every political party to compete fairly for control of the United States government. Justice Alito, the author of the draft opinion overturning Roe, is also the author of two important decisions dismantling much of the Voting Rights Act.

This behavior, moreover, is consistent with the history of an institution that once blessed slavery and described Black people as “beings of an inferior order.” It is consistent with the Court’s history of union-busting, of supporting racial segregation, and of upholding concentration camps.

Moreover, while the present Court is unusually conservative, the judiciary as an institution has an inherent conservative bias. Courts have a great deal of power to strike down programs created by elected officials, but little ability to build such programs from the ground up. Thus, when an anti-governmental political movement controls the judiciary, it will likely be able to exploit that control to great effect. But when a more left-leaning movement controls the courts, it is likely to find judicial power to be an ineffective tool.

The Court, in other words, simply does not deserve the reverence it still enjoys in much of American society, and especially from the legal profession. For nearly all of its history, it’s been a reactionary institution, a political one that serves the interests of the already powerful at the expense of the most vulnerable. And it currently appears to be reverting to that historic mean.

Alito wants abortion supporters to play a rigged game

There have only been three justices in American history who were appointed by a president who lost the popular vote, and who were confirmed by a bloc of senators who represent less than half the country. All three of them sit on the Supreme Court right now, and all three were appointed by Donald Trump.

Indeed, if not for anti-democratic institutions such as the Senate and the Electoral College, it’s likely that Democrats would control a majority of the seats on the Supreme Court, and a decision overruling Roe would not be on the table.

So it is ironic — for that reason, and others — that Alito’s draft opinion overruling Roe leans heavily on appeals to democracy. Quoting from an opinion by the late Justice Antonin Scalia, Alito writes that “the permissibility of abortion, and the limitations upon it, are to be resolved like most important questions in our democracy: by citizens trying to persuade one another and then voting.”

If Alito truly wants to put the question of whether pregnant individuals have a right to terminate that pregnancy up to a free and fair democratic process, polling indicates that liberals could probably win that fight on a national level.

In fairness, polling on abortion often misses the nuances of public opinion. Many polls, for example, allow respondents to say that they believe that abortion should be legal “under certain circumstances” or in “most cases,” leaving anyone who reads those polls to speculate under which specific circumstances people think that abortion should be legal.

Perhaps the best evidence that proponents of legal abortion could win a fair political fight, however, is the Supreme Court’s own polling. After the Court allowed a strict anti-abortion law to take effect in Texas last fall, multiple polls found the Supreme Court’s approval rating at its lowest point ever recorded.

But public opinion may not matter much in the coming political fight over abortion, because Alito and his fellow Republican justices have spent the past decade placing a thumb on the scales of democracy — making our system even less democratic than one that already features the Electoral College and a malapportioned Senate.

Alito authored two opinions and joined a third that, when combined, almost completely neutralize the Voting Rights Act, the landmark legislation that took power away from Jim Crow and ensured that every American would be able to vote, regardless of their race.

Similarly, the Court’s Republican majority held in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019) that federal courts will do nothing to stop partisan gerrymandering. Alito is also one of the Court’s most outspoken proponents of the “independent state legislature doctrine,” a doctrine that, in its strongest form, would give gerrymandered Republican legislatures nearly limitless power to determine how federal elections are conducted in their state — even if those gerrymandered legislatures violate their state constitution.

One of the most troubling aspects of this Court’s jurisprudence is that it often seems to apply one set of rules to Democrats and a different, more permissive set of rules to Republicans. Last February, for example, Alito voted with four of his fellow Republicans to reinstate an Alabama congressional map that a lower court determined to be an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

In blocking the lower court’s order, Alito joined an opinion arguing that the lower court’s decision was wrong because it was handed down too close to the next election.

But then, in late March, the Court enjoined Wisconsin’s state legislative maps, due to concerns that those maps may give too much political power to Black people. March is, of course, closer to the next Election Day than February. So it is difficult to square the March decision with the approach Alito endorsed in February — though it is notable that the March decision by the Supreme Court benefited the Republican Party, while the previous decision was likely to benefit Democrats.

I could list more examples of how this Court, often relying on novel legal reasoning, has advanced the Republican Party’s substantive agenda — on areas as diverse as religion, vaccination, and the right of workers to organize. But really, every issue pales in importance to the right to vote.

If this right is not protected, then liberals are truly defenseless — even when they enjoy overwhelming majority support.

The Court’s current behavior is consistent with its history

In Marbury v. Madison (1803), the Supreme Court held that it has the power to strike down federal laws. But the actual issue at stake in Marbury — whether a single individual named to a low-ranking federal job was entitled to that appointment — was insignificant. And, after Marbury, the Court’s power to strike down federal laws lay dormant until the 1850s.

Then came Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), the pro-slavery decision describing Black people as “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Dred Scott, the Court’s very first opinion striking down a significant federal law, went after the Missouri Compromise’s provisions limiting the scope of slavery.

It’s not surprising that an institution made up entirely of elite lawyers, who are immune from political accountability and cannot be fired, tends to protect people who are already powerful and cast a much more skeptical eye on people who are marginalized because of their race, gender, or class. Dred Scott is widely recognized as the worst decision in the Court’s history, but it began a nearly century-long trend of Supreme Court decisions preserving white supremacy and relegating workers into destitution — a history that is glossed over in most American civics classes.

The American people ratified three constitutional amendments — the 13th, 14th, and 15th — to eradicate Dred Scott and ensure that Black Americans would enjoy, in the 14th Amendment’s words, all of the “privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

But then the Court spent the next three decades largely dismantling these three amendments.

Just 10 years after the Civil War, the Supreme Court handed down United States v. Cruikshank (1875), a decision favoring a white supremacist mob that armed itself with guns and cannons to kill a rival Black militia defending its right to self-governance. Black people, the Court held in Cruikshank, “must look to the States” to protect civil rights such as the right to peacefully assemble — a decision that should send a chill down the spine of anyone familiar with the history of the Jim Crow South.

The culmination of this age of white supremacist jurisprudence was Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which blessed the idea of “separate but equal.” Plessy remained good law for nearly six decades after it was decided.

After decisions like Plessy effectively dismantled the Reconstruction Amendments’ promise of racial equality, the Court spent the next 40 years transforming the 14th Amendment into a bludgeon to be used against labor. This was the age of decisions like Lochner v. New York (1905), which struck down a New York law preventing bakery owners from overworking their workers. It was also the age of decisions like Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923), which struck down minimum wage laws, and Adair v. United States (1908), which prohibited lawmakers from protecting the right to unionize.

The logic of decisions like Lochner is that the 14th Amendment’s language providing that no state may “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” created a “right to contract.” And that this supposed right prohibited the government from invalidating exploitative labor contracts that forced workers to labor for long hours with little pay.

As Alito notes in his draft opinion overruling Roe, the Roe opinion did rely on a similar methodology to Lochner. It found the right to an abortion to also be implicit in the 14th Amendment’s due process clause.

For what it’s worth, I actually find this portion of Alito’s opinion persuasive. I’ve argued that the Roe opinion should have been rooted in the constitutional right to gender equality — what the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg once described as the “opportunity women will have to participate as men’s full partners in the nation’s social, political, and economic life” — and not the extraordinarily vague and easily manipulated language of the due process clause.

Indeed, one of the most striking things about the Court’s Lochner-era jurisprudence is how willing the justices were to manipulate legal doctrines — applying one doctrine in one case, then ignoring it when it was likely to benefit a party that they did not want to prevail.

In Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), for example, the Supreme Court struck down a federal law that prohibited goods produced by child labor from traveling across state lines. The reason Congress structured this ban on child labor in such an unusual way is because the Supreme Court had repeatedly held prior to Dagenhart that Congress could ban products from traveling in interstate commerce — among other things, the Court upheld a law prohibiting lottery tickets from traveling across state lines in Champion v. Ames (1903).

But the rule announced in Champion and similar cases was brushed aside once Congress decided to use its lawful authority to protect workers.

The Court also did not exactly cover itself in glory after President Franklin Roosevelt filled it with New Dealers who rejected decisions like Lochner and Hammer. One of the most significant Supreme Court decisions of the Roosevelt era, for example, was Korematsu v. United States (1944), the decision holding that Japanese Americans could be forced into concentration camps during World War II, for the sin of having the wrong ancestors.

The point is that decisions like Alito’s draft Dobbs opinion, which would commandeer the bodies of millions of Americans — or decisions dismantling the Voting Rights Act — are entirely consistent with the Court’s history as defender of traditional hierarchies. Alito is not an outlier in the Court’s history. He is quite representative of the justices who came before him.

The judiciary is structurally biased in favor of conservatives

In offering this critique of the Supreme Court, I will acknowledge that the Court’s history has not been an unbroken string of reactionary decisions dashing the hopes of liberalism. The Court’s marriage equality decision in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), for example, was a real victory for liberals — although, as several commentators have noted, there is language in Alito’s draft Dobbs opinion suggesting that, if Roe falls, LGBTQ+ rights could be next.

But the Court’s ability to spearhead progressive change that does not, like marriage equality, enjoy broad popular support is quite limited. The seminal work warning of the heavy constraints on the Court’s ability to effect such change is Gerald Rosenberg’s The Hollow Hope, which argues that “courts lack the tools to readily develop appropriate policies and implement decisions ordering significant social reform,” at least when those reforms aren’t also supported by elected officials.

This constraint on the judiciary’s ability to effect progressive change was most apparent in the aftermath of perhaps the Court’s most celebrated decision: Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Brown triggered “massive resistance” from white supremacists, especially in the Deep South. As Harvard legal historian Michael Klarman has documented, five years after Brown, only 40 of North Carolina’s 300,000 Black students attended an integrated school. Six years after Brown, only 42 of Nashville’s 12,000 Black students were integrated. A decade after Brown, only 1 in 85 African American students in the South attended an integrated school.

The courts simply lacked the institutional capacity to implement a school desegregation decision that Southern states were determined to resist. Among other things, when a school district refused to integrate, the only way to obtain a court order mandating desegregation was for a Black family to file a lawsuit against it. But terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan used the very real threat of violence to ensure few lawsuits were filed.

No one dared to file such a lawsuit seeking to integrate a Mississippi grade school, for example, until 1963.

Indeed, much of the South did not really begin to integrate until Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which allowed the Justice Department to sue segregated schools, and which allowed federal officials to withhold funding from schools that refused to integrate. Within two years after this act became law, the number of Southern Black students attending integrated schools increased fivefold. By 1973, 90 percent of these students were desegregated.

Rosenberg’s most depressing conclusion is that, while liberal judges are severely constrained in their ability to effect progressive change, reactionary judges have tremendous ability to hold back such change. “Studies of the role of the courts in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,” Rosenberg writes, “ show that courts can effectively block significant social reform.”

And, while such reactionary decisions may eventually fall if there is a sustained political effort to overrule them, this process can take a very long time. Dagenhart was decided in 1918. The Court did not overrule it, and thus permit Congress to ban child labor, until 1941.

There are several structural reasons courts are a stronger ally for conservative movements than they are for progressive ones. For starters, in most constitutional cases courts only have the power to strike down a law — that is, to destroy an edifice that the legislature has built. The Supreme Court could repeal Obamacare, but it couldn’t have created the Affordable Care Act’s complex array of government-run marketplaces, subsidies, and mandates.

Litigation, in other words, is a far more potent tool in the hands of an anti-governmental movement than it is in the hands of one seeking to build a more robust regulatory and welfare state. It’s hard to cure poverty when your only tool is a bomb.

So, to summarize my argument, the judiciary, for reasons laid out by Rosenberg and others, structurally favors conservatives. People who want to dismantle government programs can accomplish far more, when they control the courts, than people who want to build up those programs. And, as the Court’s history shows, when conservatives do control the Court, they use their power to devastating effect.

This alone is a reason for liberals, small-d democrats, large-D Democrats, and marginalized groups more broadly, to take a more critical eye to the courts. And the judiciary’s structural conservatism is augmented by the fact that, in the United States, institutions like the Electoral College and Senate malapportionment give Republicans a huge leg up in the battle for control of the judiciary.

Of course I do not believe that we should literally light the Supreme Court of the United States on fire, but I do believe that diminished public trust in the Court is a good thing. This institution has not served the American people well, and it’s time to start treating it that way.

Rep. Ro Khanna has been an outspoken supporter of canceling student debt. (photo: Getty)

Rep. Ro Khanna has been an outspoken supporter of canceling student debt. (photo: Getty)

Now, as a member of Congress, I’ve spoken to young people across the country and asked them what Democrats can do to make their lives tangibly better. From San Jose to West Virginia, I hear the same answer: Cancel student debt. President Biden has the authority to do this with the stroke of a pen for borrowers struggling to make ends meet. The more forgiveness, the better.

It’s time to do it, Mr. President.

Canceling student loan debt for working- and middle-class Americans is the right thing to do. No one should be prevented from pursuing higher education because they can’t afford the financial burden it poses. Furthermore, it makes economic sense: Relief from student debt would help young people buy homes, build wealth and otherwise grow our economy.

Student loan debt was a defining issue during the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) released a plan to cancel debt up to $50,000 for those making $100,000 or less, and would help 95 percent of borrowers, and I’m an original co-sponsor of the House bill that is based on this plan. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) said he’d cancel it all. Even then-candidate Joe Biden told participants at a town hall in Miami, “I’m going to make sure that everybody in this generation gets $10,000 knocked off of their student debt.”

As president, Biden has the power to cancel student loan debt — in fact he has already used this authority to do so, but only for a small group of Americans. Using the Higher Education Act of 1965, Biden eliminated nearly $20 billion in student loans for select borrowers defrauded by for-profit colleges, individuals with permanent disabilities and those working in public service. He also paused federal student loan repayments and forgave interest payments on these loans to relieve the burden during the pandemic.

These are vital steps for our nation, but this is a moment that demands bold action. If he can suspend interest payments, he can forgive the principal. If he can cancel student debt for some, then he can cancel it for all those in need.

Forgiving student loan debt is progressive economic policy, not regressive, as critics wrongly maintain. According to an analysis by the Roosevelt Institute, the people who would benefit most from debt cancellation are those with the least amount of wealth. This relief would be particularly meaningful for the millions of Americans who never received a college degree but did incur student debt — and who are more than four times as likely as their graduating counterparts to default on it.

Student loan forgiveness is also essential to overcome the racial wealth gap. Black students are more likely than their White counterparts to take out student loans and struggle to pay them off. The Roosevelt Institute analysis found that canceling up to $50,000 in student loan debt would immediately increase the wealth of Black Americans by 40 percent.

Another myth is that Americans without college degrees will have to pay for student debt relief. This is simply not true. To avoid adding to the national debt, we could pay for student debt cancellation with Biden’s proposed billionaire tax and institute a transaction tax on Wall Street speculation. As for implementation, the Education Department has demonstrated capability to deliver Pell Grants and other federal student aid targeted by household income.

If Democrats want to regain the trust of people across the country both young and old, rural and urban, and across lines of race, gender and class, we need to deliver on the things that materially improve people’s lives. I’m encouraged that Biden has committed to make a decision by Aug. 31 on student loan cancellation and has told my colleagues he is inclined to do something.

The best way to start the new school year for everyone saddled with crushing student loans would be for Biden to free them of this burden.

The Supreme Court's official opinion place the US in a very small club of countries that have moved to restrict access in recent years. (photo: Alex Brandon/Getty)

The Supreme Court's official opinion place the US in a very small club of countries that have moved to restrict access in recent years. (photo: Alex Brandon/Getty)

What role did dark money play in the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade? We speak with reporter Andrew Perez about how conservative anti-abortion groups and right-wing extremists have funneled millions of dollars into promoting politicians and Supreme Court justices to ultimately curtail reproductive rights. A dark money network led by the Federalist Society’s Leonard Leo has spent at least $10 million promoting each of President Trump’s picks for the Supreme Court and another $10 million blocking Merrick Garland’s nomination in 2016, says Perez, senior editor and investigative reporter at The Lever.

The Supreme Court’s anticipated reversal of federal constitutional protections of abortion rights is out of step with the views of a majority of Americans, as well as the Democratic majority in Congress and President Biden. Some put the number, the percentage of Americans for abortion at 70%.

For more, we’re joined by Andrew Perez, senior editor and reporter at The Lever. He co-wrote the new piece “The Roe Disaster — And What To Do About It: Reproductive rights are on the chopping block because of dark GOP schemes and Democrats’ duplicity — but this fight is not over,” writes Andrew Perez.

Andrew, why don’t you take it from there? Follow the dark money trail for us.

ANDREW PEREZ: Sure. Yeah, so, Leonard Leo is a longtime senior executive at the Federalist Society, and he played a huge role in building this court the way it is and making it so that it’s poised to overturn Roe v. Wade. And so, since 2005, he’s been leading a dark money network, and its owners are pretty much unknown. We really have no idea who’s been funding it. But they’ve been highly influential. They’ve run a lot of TV ads, boosting candidates or boosting judges. And they also helped play a role in fighting Merrick Garland’s nomination in 2016, which obviously didn’t advance. And he also got to help make the court picks for Trump as his chief judicial adviser.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And could you talk a little bit more specifically about the amounts of money involved here — you’ve traced enormous sums that were plowed into building support for Justice Amy Coney Barrett and Brett Kavanaugh — and how the network actually operated?

ANDREW PEREZ: Sure. I’d say it’s probably like, you know, nearly $10 million per pick. That’s sort of what they said they were spending, what Judicial Crisis Network said it was going to be spending. You know, that group and its kind of affiliates also then definitely donated some millions of dollars to other groups that were supporting, you know, both Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett. And they also said that they spent around $10 million to block Garland’s nomination in 2016.

JUAN GONZÁLEZ: And this wasn’t just money spent on the Supreme Court, right, in terms of the impact of Leonard Leo on many other lower federal court appointments by both President Trump and President Bush?

ANDREW PEREZ: Definitely, yeah. They have been active, especially recently, on some lower court nominations. And they’ve also been really involved in state supreme court fights, like in Wisconsin. And I believe that they also helped finance an effort in Nebraska to basically reinstate the death penalty.

Given how the history of tech censorship has gone, it would be surprising if PayPal's censure of Consortium News and MintPress News is where the current trend ends. (photo: Marques Thomas/Unspash)

Given how the history of tech censorship has gone, it would be surprising if PayPal's censure of Consortium News and MintPress News is where the current trend ends. (photo: Marques Thomas/Unspash)

Over the past week, PayPal canceled without explanation the accounts of two prominent independent news outlets. It escaped notice by the mainstream press, which spent the weekend congratulating itself over the freedom to criticize the powerful.

Consortium News, founded by the late Associated Press investigative legend Robert Parry in 1995 as one of the web’s very first independent, reader-funded news outlets, reported over the weekend that PayPal had “permanently limited” its account, just as it was launching its Spring Fund Drive. According to editor-in-chief Joe Lauria — a former longtime United Nations correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and others — the company said it would hold onto the thousands of dollars accumulated in the outlet’s account for 180 days and reserved the right to seize the money entirely to pay for unnamed “damages.”

According to Lauria, Consortium News was neither warned that they were at risk of censure nor given a reason for it in either PayPal’s initial email or a follow-up call with a customer service representative. PayPal’s back office didn’t give a reason for the action, and there was no existing case against the outlet. Lauria reported he was informed of the move by the customer agent, who only mentioned that an “investigation and review” revealed “some potential risk associated with this account.” Given the outlet’s critical coverage of the Ukraine war, and given the far-reaching steps already taken in the “information war” over the conflict, Lauria writes that it’s “more than conceivable” the outlet is being punished for its Ukraine coverage.

A few days earlier, MintPress News, a left-wing web-based outlet based out of Minnesota, had been similarly informed by PayPal that it was banned from the company after a review allegedly turned up an unspecified “potential risk” with its account. The outlet’s founder and executive editor, Mnar Adley, told Jacobin that, as with Consortium News, the outlet received no prior warning from PayPal and was told their existing balance would be held by the company for half a year. This isn’t the first time MintPress has been financially targeted, Adley says; GoFundMe terminated two different fundraisers she had been running for years, suddenly saying they had violated the site’s terms of service.

In this case, PayPal’s net went beyond the organization itself and targeted one of its journalists, too, with senior staff writer Alan MacLeod having his personal account canceled at the same time. PayPal told him it had detected “activity in your account that’s inconsistent with our User Agreement,” something he calls “patently absurd” because the last time he had used PayPal was to buy a £5 Christmas gift in December. MacLeod and Adley both say they had fortunately withdrawn funds shortly before the cancellations, but the loss will still have lingering effects. MintPress was pulling in roughly $1,000 a month from readers’ membership payments through the service, Adley says, while MacLeod notes it could hurt his ability to be paid for future reporting.

Like Consortium News, MintPress has been critical of US policy toward the Ukraine invasion. In recent days, MacLeod has published pieces scrutinizing the newly formed and popular-in-the-West Kyiv Independent, exposed TikTok’s hiring of numerous NATO and other national security personnel for top posts, and, ironically, criticized online censorship efforts to do with the war.

“The sanctions-regime war is coming home to hit the bank accounts of watchdog journalists,” says Adley.

Seeds Long Planted

Regardless of what you might think about either publication’s output — like any publication, a reasonable reader will find pieces at both that they agree and disagree with — this is a frightening attack on press freedoms. Faceless tech bureaucrats have unilaterally cut two serious independent media outlets off from a vital source of funding with no prior warning, no ability to appeal, and no explanation besides a vague reference to “potential risk,” all at a time when critical debate about the most dangerous conflict in most Americans’ lifetimes is being stifled in a climate of fear and repression.

The seeds for this latest action were sown over a decade ago, when PayPal, under pressure from the US government, froze the account of WikiLeaks. At the time, the whistleblowing publisher had released a series of data troves revealing previously undisclosed Western war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan, before releasing a searchable database of 250,000 State Department cables.

Commentators warned at the time that the move would set a dangerous precedent and would be used against other publishers in the future. Equally foreboding is PayPal’s partnership, announced last year, with the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), an organization with a history of hostility to the Left and pro-Palestinian advocacy, which it attacks under the guise of combating antisemitism. Eight months after announcing the two would work together on “uncovering and disrupting the financial pipelines that support extremist and hate movements,” ADL chief executive Jonathan Greenblatt has announced the organization would put “more concentrated energy toward the threat of radical anti-Zionism” and declared, in what appears to be a hardening of its previous official line, that “anti-Zionism is antisemitism.” (It’s not.)

On other fronts, the ADL has recently relaxed its anti-extremist vigilance. Only two months ago, the group played down the threat of the far right in Ukraine, claiming it was a “very marginal group with no political influence and who don’t attack Jews,” a claim that is, to put it mildly, questionable. PayPal’s moves against independent left-wing news outlets, coupled with its ongoing partnership with the ADL, is ominous, and may well foreshadow more targeting of independent media outlets and reporters who dissent from the ADL’s right-wing stance on the Israel-Palestine conflict.

All of this comes days after as the press indulged in its annual hobnobbing with government officials at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. Host Trevor Noah has been widely applauded for his speech, marveling that despite lightly roasting the president — an unremarkable, mandatory feature of the annual event — he was “going to be fine” and that “in America, you have the right to seek the truth and speak the truth, even if it makes people in power uncomfortable.” That right, apparently, doesn’t extend to the independent press.

Given how the history of tech censorship has gone, it would be surprising if the censure of Consortium News and MintPress News is where this ends, particularly with PayPal’s actions receiving no pushback, criticism, or even notice outside of independent media. But mainstream press outlets would be foolish to ignore the issue. Tech censorship may be overwhelmingly focused on independent outlets for now, but given recent precedents, it’s only a matter of time before a president — one less friendly toward the press — uses the union of tech companies and government power to train the crosshairs on them.

A man walks past a pro-unification mural in Belfast. (photo: Clodagh Kilcoyne/Reuters)

A man walks past a pro-unification mural in Belfast. (photo: Clodagh Kilcoyne/Reuters)

Sinn Féin, a nationalist party that supports reunification, is predicted to get the post of first minister for the first time.

This is because Sinn Féin, an Irish nationalist party that supports the reunification of Northern Ireland with the Republic of Ireland, is widely predicted to secure the majority of the votes and as such become entitled to the post of first minister.

It would be the first time in the history of the state that a nationalist has held this role instead of Unionist politicians, who favour Northern Ireland remaining part of the United Kingdom.

Northern Ireland was created in 1921, designed to have a permanent Unionist majority.

However, the majority has been on the decline for decades, and the two main unionist parties saw significant losses in the 2017 election.

This is partly due to changing demographics.

The results of the 2021 census due later this year are expected to show that the proportion of the population coming from a Catholic background, from whom Irish nationalist parties draw most of their support, is now larger than those from a Protestant background.

No less than a threat

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), which has been the largest party since 2007, has painted Sinn Féin becoming the largest party as no less than a threat to Northern Ireland’s very future.

Party leader Jeffery Donaldson said Sinn Féin becoming the largest party would put them “one step closer to delivering their plans for a border poll”, or a vote on the constitutional future of the province.

While technically the holder of the office of first minister makes little practical difference – the two largest nationalist and unionist parties must work together under the terms of the post-civil war settlement – the timing of it would have huge symbolic importance.

Many feel that their place in the union with Great Britain is shaken, Dr Deirdre Heenan, professor of social policy at the University of Ulster, told Al Jazeera.

“They feel vulnerable. Political unionism is in complete disarray,” Heenan said.

Sinn Féin taking the post of first minister “is psychologically important for Unionists who are already reeling from betrayal by [UK Prime Minister] Boris Johnson, from fallout from Brexit, the protocol and the border in the Irish Sea”, she said.

The DUP has refused to confirm whether they will serve alongside a Sinn Féin first minister.

Under the cross-community framework of the 1998 Good Friday agreement, such a refusal will prevent the formation of a government.

Sinn Féin’s election to lose

Sinn Féin Northern Ireland leader Michelle O’Neill has said her priority in this election is “to show that real change is possible”.

Yet, despite the historic implications of a nationalist taking the first minister post, a Sinn Féin victory this week will paradoxically not result from any surge in support for the party.

Indeed, polling shows that their share of the vote will be down slightly compared with the last election.

The upset will instead come from the DUP losing votes, as they are on track to do. They were only the largest party by one seat in the last election, and several of these will be difficult to maintain.

In this context, Sinn Féin knows the election is theirs to lose, said Heenan, and this is evident in their campaigning.

“They have taken the most minimalist approach to electioneering, to campaigning, to being in the media, being in the public,” she said.

“What they absolutely do not want is to drop the ball and get embroiled in controversy, galvanising the Unionist vote,” Heenan added.

Former DUP leader Arlene Foster’s comments comparing Sinn Féin to greedy crocodiles in 2017 helped galvanise voters, providing nationalists “with a rallying banner”, unionist commentator Alex Kane wrote at the time.

“There is an irony in the fact that while Sinn Féin seemed likely to take on the first minister role, this is not a reflection of a huge sea change or a surge in Northern Ireland of people saying we want Irish unity,” Heenan said.

“This really is about, in the terms of the two main parties, who loses the least seats,” she said.

Party in chaos

The DUP’s problems are a combination of issues, including party mismanagement, their handling of Brexit, and the Northern Ireland protocol – a post-Brexit trade barrier with the rest of the UK, which many unionists strongly oppose.

The party has had three leaders in less than a year, with one resigning after a term of just three weeks.

This amounts to a considerable change in fortune from just a few years ago, when a record number of DUP MPs elected saw them form a “confidence and supply” agreement with the UK’s ruling Conservative party.

However, there is a feeling that “the DUP squandered the balance of power at Westminster when they had this unique opportunity to wield influence, and that they haven’t played their hand very well”, said Jon Tonge, professor of politics at the University of Liverpool and co-author of The Democratic Unionist Party: From Protest to Power.

“The DUP’s best years are probably a bit behind it”, he said.

Protocol

DUP leader Donaldson has insisted that there must be significant movement on the post-Brexit trade barrier with the rest of the UK before he goes back into government, saying in the final televised leaders’ debate last night that the Northern Ireland protocol has “changed our constitutional status and we can’t ignore that”.

The protocol, which creates a trade border in the Irish sea to avoid a land border on the island of Ireland, is fiercely contested by all unionist parties and an important issue for many unionist voters.

While the actual economic impact of the protocol on Northern Ireland is contested, it is perceived by many to be a weakening of the link with the rest of the UK and that its place in the union was under threat.

Border post staff working at the two main ports were temporarily withdrawn following threats and intense rioting last April – with cars being hijacked, bins set on fire, and an empty bus petrol-bombed – was attributed in part to tensions around the protocol.

Anti-protocol rallies this year have featured a picture of a major unionist leader deemed not sufficiently “loyal” with a noose around his neck, while there was a paramilitary bomb threat on the Irish foreign minister when we was speaking in Belfast in March.

Other issues

While the protocol is of concern for many unionist voters, it is not the most important one.

Coming out of a pandemic and into a cost-of-living crisis, people are more aware of the importance of a government “that functions and delivers and is there to take those day-to-day decisions,” said Liz Nelson, a political commentator in Belfast.

All parties have thus also sought to emphasise bread-and-butter issues and focus on day-to-day priorities.

This election is also likely to show increased support for parties that are neither unionist nor nationalist.

Alliance leader Naomi Long delivered a series of good results in local and other elections in 2019.

Polls show them becoming the third-largest party – they are currently fifth – almost tying with the DUP.

Such a result would be as important a shift in Northern Ireland’s politics as a Sinn Féin first minister.

The smaller Green party and socialist People Before Profit are also expected to increase their vote share.

The presence of smaller parties on the campaign trail has been notable, Nelson said.

“It’s been the smaller ones who have [come] to my door multiple times, having conversations with my neighbours. It’s not been the big parties who showed up, and I think that that is risky,” she said.

“I don’t think that big parties can be assured of anybody’s vote this time around, just because they might have had it the last time. I think people are fed up.”

Pro-industry groups in New Mexico are pushing out what some experts have called 'sky is falling' messaging. (photo: Getty)

Pro-industry groups in New Mexico are pushing out what some experts have called 'sky is falling' messaging. (photo: Getty)

Fossil fuel interest groups are telling New Mexicans: let us keep drilling or the state’s education system will collapse

“What do all of these have in common?” a 6 April Facebook post by the New Mexico Oil and Gas Association (NMOGA), asked. “They are powered by oil and natural gas!”

Here in New Mexico – the fastest-warming and most water-stressed state in the continental US, where wildfires have recently devoured over 120,000 acres and remain uncontained – the oil and gas industry is coming out in force to deepen the region’s dependence on fossil fuels. Their latest tactic: to position oil and gas as a patron saint of education. Powerful interest groups have deployed a months-long campaign to depict schools and children’s wellbeing as under threat if government officials infringe upon fossil fuel production.

In a video spot exemplary of this strategy, Ashley Niman, a fourth-grade teacher at Enchanted Hills elementary school tells viewers that the industry is what enables her to do her job. “Without oil and gas, we would not have the resources to provide an exemplary education for our students,” she says. “The partnership we have with the oil and gas industry makes me a better teacher.”

The video, from September last year, is part of a PR campaign by NMOGA called “Safer and Stronger”. It’s one of many similar strategies the Guardian tracked across social media, television and audio formats that employs a rhetorical strategy social scientists refer to as the “fossil fuel savior frame”.

“What NMOGA and the oil and gas industry are saying is that we hold New Mexico’s public education system hostage to our profit-motivated interests,” said Erik Schlenker-Goodrich, executive director of the Western Environmental Law Center. “There’s an implied threat there.”

Last year, New Mexico brought in $1.1bn from mineral leasing on federal lands – more than any other US state. But the tides may be turning for the fossil fuel industry as officials grapple with the need to halve greenhouse gas emissions this decade. Before mid-April, the Biden administration had paused all new oil and gas leasing and the number of drilling permits on public lands plummeted.

In response, pro-industry groups are pushing out what some experts have called “sky is falling” messaging that generates the impression that without oil and gas revenue, the state’s education system is on a chopping block. NMOGA did not respond for comment.

Since February, NMOGA has flooded its social media pages with school-related motifs like buses and books, but also with images of empty, abandoned classrooms accompanied by reminders about how the state’s schools “rely on oil and gas production on federal land for more than $700m in funding”. Elected officials have parroted this framing. “This is a matter of critical importance to all, but especially to New Mexico’s schoolchildren, who have suffered greatly during the pandemic,” state representative Yvette Herrell co-wrote in the Santa Fe New Mexican, in February.

But tax, budget and public education funding experts say linking the federal leasing pause to a grave, immediate risk to public education is deceptive.

“Any slight reductions stemming from pauses or other so-called ‘adverse’ actions would have zero immediate effect on school funding overall, much less whether students get the services they need to recover from the ill effects on their learning from the pandemic,” said Charles Goodmacher, former government and media relations director at the National Education Association (NEA), now a consultant. The sale of leases does not lead to immediate drilling, he said. Often, companies sit on leases for months or years before production occurs.

And as it happens, New Mexico currently has a budget surplus from record production.

Industry attempts to convince New Mexicans that the state’s public education system is wholly dependent on oil and gas are based on a tough truth: decades of steep tax cuts have indeed positioned fossil fuels as the thunder behind Democratic-led New Mexico’s economy. In 2021, 15% of the state’s general fund came from royalties, rents and other fees that the Department of the Interior collects from mineral extraction on federal lands. Oil and gas activity across federal, state and private lands contributes around a third of the state’s general fund of $7.2bn, as well as a third of its education budget.

The commissioner of public lands, Stephanie Garcia Richard, herself a former classroom teacher, has been at the forefront of efforts to diversify the New Mexican economy since she was elected to manage the state’s 13m acres of public lands in 2018.

“When I ran, in my first campaign, we talked a lot about how a school teacher really understands what every dime that this office makes means to a classroom.”

Garcia Richard takes pride in being the first woman, Latina and teacher to have been elected to head the office, which oversees about $1bn in revenue generation each year. Since 2019, she’s launched a renewable energy office and outdoor recreation office to raise money from those activities, though Garcia Richard doesn’t believe that money will ever fully make up for oil and gas revenue. “I don’t want anybody ever to think that I have some notion that the revenue diversification strategies we’re pursuing right now somehow make a billion dollars.”

New Mexico’s attorney general, Hector Balderas, a Democrat, is another top state official charged with managing the state’s energy and economic transition.

Given the same geographic features that make New Mexico the “land of enchantment”, the state is positioned to become a national leader in solar energy, Balderas said. But four of the state’s major solar farms are severely behind schedule.

Balderas, who has accepted $49,900 in campaign contributions from oil and gas over seven election cycles, said that a sudden disruption in new oil and gas leasing such as the blanket moratorium the Biden administration originally proposed in January last year, would have an outsized impact on New Mexico’s most vulnerable.

“You would cut out nearly a third of the revenue that we rely on to fund our schools and our roads and our law enforcement community,” he said. “I don’t think environmental activists really think about that perspective: how progressives have cleaner air but then thrust original Americans like Native American pueblos into further economic poverty.”

Some on the receiving end of oil and gas revenue stress that not all educators and students embrace fossil fuel industry money in public schools. Mary Bissell is an algebra teacher at Cleveland high school in Rio Rancho, who co-signed a letter in November, along with more than 200 educators, asking NMOGA to “stop using New Mexico’s teachers and kids as excuses for more oil and gas development”.

Bissell says in spite of how cash-strapped schools may be, many of her colleagues don’t want oil and gas money. “I’m not going to teach my kids how to find slope based on fracking,” she said of her math courses. Bissell characterized NMOGA’s attempt to portray educators as a unified force beholden to oil and gas funding as “disgusting.”

In some states, including Rhode Island and Massachusetts, state attorneys general have taken it upon themselves, as the leading law enforcement and consumer protection officials, to sue oil and gas companies for deceiving consumers and investors about climate change through their marketing. Balderas’s office said it was not actively pursuing that strategy.

Seneca Johnson, 20, a student leader with Youth United for Climate Action (Yucca), is from the Muscogee Nation of Oklahoma. Johnson grew up in New Mexico, and knows first hand about the state’s underfunded schools. “I remember in elementary school we would have a list: bring three boxes of tissues, or colored pencils,” she said, speaking of Chaparral elementary school in Santa Fe. “As students and as teachers, [you’re] buying the supplies for the classroom.”

Johnson remembers being told as a child that the schools she attended ranked second worst in the nation. If New Mexico’s education system is indeed that bad, she said, how can officials continue to think that accepting a funding structure that delivers such a consistently poor result is a good idea?

“At the end of the day the system that we have now that is being paid for by oil and gas doesn’t work, and we know it doesn’t work,” Johnson said. “It’s the whole ‘Don’t bite the hand that feeds you’ kind of mentality,” she said, linking the industry’s patronizing messaging around its support for schools to a direct legacy of colonization.

“I don’t want to have to rely on this outside entity. I don’t want to have to rely on this broken system. I want better for my kids and their kids and my whole community.”

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.