Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The Biden administration has quietly decided to continue a Trump administration scheme whose ultimate goal is the privatization of Medicare. Americans would be outraged — if anyone knew about it.

Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), the leading group behind the effort, had been trying for some time to make its displeasure about the “direct contracting” program known. After collecting more than thirteen thousand signatures for a petition opposing the initiative, they’d asked repeatedly for a meeting with Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary Xavier Becerra to hand it to him. They called, emailed, left voice messages, all to no avail. The most they got was a single response from a staffer, sent the night before their DC visit, promising to set up a meeting sometime in the future.

The next day, the group marched into HHS headquarters, petition in hand, only to be stopped by security and told that was as far as they could go without an appointment. They’d have to ask someone to come downstairs and pick it up — only to learn there was no one available in the offices to do it. After close to an hour, the group left the petition with security and departed, having been blocked from carrying out one of the most basic and foremost rights enumerated in the constitution.

Locked doors, unreturned emails, a large crowd with no one around to hear it — nothing more perfectly captured the struggle of public health care advocates to raise the alarm about direct contracting, a pilot program begun under Donald Trump and continued under Joe Biden.

In the middle of a pandemic, and during what pundits describe as a fundamental shift in Americans’ views of the government’s role in their lives, an initiative to shoehorn for-profit companies between retirees and their Medicare coverage should in theory have prompted a public outcry. The only problem is, no one seemed to know it was happening.

“A Corporate Goldmine”

Over the past year, seniors around the country have been getting letters from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) informing them that they needn’t worry, but their doctor was now part of something called a direct contracting entity (DCE). “Your Medicare Benefits have not changed,” the letters stress no less than twice. “NO ACTION NEEDED,” they blare.

If you take it from CMS, DCEs are simply a collection of different health care providers “who agree to work together to keep you healthy” — an innovative new payment model to keep health care costs down and raise the quality of care up. For its critics, the initiative is something far less benign.

“What direct contracting does is turn the public side of Medicare into a corporate goldmine,” says Diane Archer, president of Just Care USA.

Under traditional Medicare, when a beneficiary gets care from a doctor, a hospital or any other health care provider, the program reimburses that provider directly at a set rate. Direct contracting adds a third party into the mix: Medicare makes a monthly payment to a DCE, which then decides what care a beneficiary will get, and uses that money to cover a specified part of their medical expenses — pocketing whatever they don’t spend as profit. While making cost-saving efficiencies usually means cutting out the middleman, direct contracting adds one in.

Critics like PNHP warn that the program comes with the same kinds of pitfalls as Medicare Advantage, the program that for the first time carved out a role of private insurers in the public Medicare system, when it was passed as part of a Reagan-era deficit reduction bill forty years ago. One is “upcoding,” the notorious practice where Medicare Advantage insurers make their patients appear less healthy than they really are, the better to drive up the payments they get from Medicare.

As a result, according to the very congressional agency set up to give policy advice on Medicare, the risk scores for patients under the semi-privatized system are 8 percent higher than for those on traditional Medicare, something one analysis determined cost taxpayers more than $106 billion in overpayments from 2010 to 2019.

After puffing up their profits at the taxpayer’s expense, Medicare Advantage insurers then tend work aggressively to minimize the costs on their end. A 2018 HHS inspector general report found inappropriate denial of care was rampant in the program, and a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis determined Medicare Advantage enrollees tended to pay more for longer hospital stays. It’s all well and good until you get seriously ill, at which point your out-of-pocket costs start soaring.

“The insurance companies are making twice as much money from Medicare Advantage than they do form employer-sponsored health insurance,” says Dr Ana Malinow, professor of pediatrics at the University of California San Francisco. “Workers have no more money, employers don’t, but who does? The government.”

Privatized by 2030

Malinow and others say that despite the similarities, direct contracting is even more pernicious than Medicare Advantage. That’s because direct contracting specifically targets those who have rejected this semi-privatized model, and chosen to stay in traditional Medicare. Those beneficiaries get a letter in the mail, open it up, and learn their doctor, and by extension, they, are now in a DCE. They’re assured all the while that everything is fine — that they’ll soon be getting “better quality care,” even — and never told if they can opt out, or how.

When DCE opponents won a Zoom meeting with Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) director Liz Fowler last December, she assured them it was possible to opt out — as long as you switched primary care providers. The attendees were shocked. Finding a new doctor is disruptive for anyone, let alone seniors who may have spent years with one they trusted, and it was deeply unpopular. Just think back to Barack Obama’s insistence that “you can keep your own doctor” under Obamacare, one of the most potent attacks on that health care reform effort. Besides that, it’s something easier said than done in rural areas short on health care choices.

But the 54 percent of the nearly $900 billion Medicare budget that’s still devoted to the program’s traditional version is too tempting to simply leave untouched by the for-profit health care industry. “The largest national insurers are positioning to become DCEs,” former CMS administrators Richard Gilfillan and Donald M. Berwick wrote last year.

That includes companies like Aetna, Alignment Health, Humana, and Clover Health, backed by Google parent company Alphabet. This isn’t the half of it, according to PNHP, which charges that virtually any company, even a venture capital firm, can apply to be a DCE and doesn’t need Congress to be approved. All are eager to take advantage of the looser rules around DCEs: while Medicare spending on administrative costs is in the single-digit percentages, and Medicare Advantage plans are forbidden by law from putting more than 15 percent of their premium revenue toward paying them, direct contracting has no such limit.

Critics also see something even more nefarious behind the initiative.

“The goal is to privatize all of Medicare through this program,” says PNHP president Susan Rogers.

It echoes the warnings of Gilfillan, Berwick, and virtually every other critic of direct contracting. Though a pilot program for now, CMS has made clear it wants to eventually move all enrollees of traditional Medicare into “a care relationship with accountability for quality and total cost of care by 2030” — vague jargon that nevertheless echoes the language direct contracting proponents use to talk about the program.

In other words, if the government has its way, by the end of the decade, every beneficiary of the traditional, entirely public Medicare will have a private, for-profit entity jammed between them and their health care. The largest remaining segment of the US health care system not dominated by corporate hands will become something else.

Paved With Corporate Greed

The road to this point has been paved by multiple administrations from both parties. CMMI, the CMS “innovation center” that came up with direct contracting, was created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Obama administration’s corporate-shaped, flagship health care reform effort. Originally meant to devise new health care payment models that would fix the spiraling costs and quality of care issues endemic to US health care, its mission was ripe for hijacking by the corporate interests that find a way to infiltrate every well-meaning government agency.

That moment came in 2018, when Trump’s HHS secretary appointed health care executive Adam Boehler to head CMMI, where he soon set the plans for direct contracting into motion. According to the Intercept, Boehler designed direct contracting with specific companies in mind, including Oxeon, the venture capital firm that had backed a number of DCEs-to-be, including the very start-up Boehler had left to join CMMI — and which he contracted with to staff the agency as it developed the initiative.

One would have thought the Trump program would have been nixed by the Biden administration, particularly with talk of the new president’s Rooseveltian ambitions and a coming revival of activist government. Instead, the administration simply canceled one iteration of direct contracting, and went ahead with a different one in April 2021, with more set to roll out this year.

The administration remains financially in thrall to the for-profit health sector. Biden’s campaign had been backed from the very start by the for-profit health care industry, and by the end of the general election, Biden had out-raised Trump among health care executives, insurance companies, and pharmaceuticals.

That includes the very officials responsible for direct contracting’s continuation. Fowler, the head of Biden’s CMMI, played a key role in drafting the insurer-friendly ACA, and had gone to work for pharmaceutical giant Johnson … Johnson prior to this current stint in Washington. Before all that, she’d served for two years as vice president of public policy for health insurer WellPoint. In 2014, WellPoint changed its name to Anthem — one of the big insurers involved in the direct contracting pilot through its subsidiary, CareMore.

Yet even Fowler appears to privately understand the folly of deepening the for-profit sector’s involvement in Medicare. Judy Albert, an ob-gyn and a clinical assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh, recalls Fowler telling her and other DCE critics in December that a single-payer system would be the best solution — if they were starting from scratch.

“I think part of that is they were playing to the audience,” she says. “But why don’t they try that for a model?”

Action Needed

For a long time, hardly anyone even knew about direct contracting, whether the public, the press — or even members of Congress. Members of PNHP recalled briefing eight lawmakers and their staffers about DCEs late last year, who were shocked to learn the program existed, let alone that the Biden administration had chosen to keep it going.

Since then, momentum for pushing back has gradually built. Archer says she and other DCE opponents began educating members of Congress about it early last year, and she credits Representatives Mark Pocan (D-WI), Katie Porter (D-CA), Lloyd Doggett (D-TX), and Bill Pascrell, Jr (D-NJ) with acting “swiftly and effectively,” writing a letter to HHS secretary Becerra in the middle of the year, to which he replied in August.

After the anti-DCE coalition’s briefing, Congressional Progressive Caucus cochair Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) gathered more than fifty signatures for another letter to Becerra this January, this one demanding an end to direct contracting and returning things to the status quo by the first of July this year. To kick off February, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) used her position as chair of the Senate finance subcommittee on fiscal responsibility and economic growth to denounce the program, warning of the “fiscal disaster” of inviting the “corporate vultures … already scamming Medicare” to skim more from the program, and calling on Biden to stop it.

But as welcome as they are, these are still relatively isolated actions, considering the stakes.

“What should be happening right now in Congress is not happening,” says Archer.

Meanwhile, with the issue gaining prominence, the health care industry is mounting its own pushback, reaching out to lawmakers to correct what they say is misinformation about the program, which they claim is simply focused on bringing “the virtues of organized groups into what is really a fragmented and dysfunctional model.”

On February 14, the National Association of ACOs (Accountable Care Organizations), an industry trade group representing DCEs, delivered to Becerra its own letter, calling on CMMI to “fix, don’t end, the direct contracting model.” Its suggestions include limiting the kinds of DCEs that can take part in the program, and a “rebranding and name change.” In turn, PNHP countered with its own letter arguing the opposite, one signed by twenty-four thousand health professionals.

It is still an uphill battle for the opponents of DCEs. Money talks in Washington, and past, current, and prospective DCEs have spent $2 million in 2021 alone lobbying Congress, CMS, HHS, and other bodies on issues that include direct contracting. That includes names like Oak Street Health, Clover Health, agilon health, and America’s Physician Groups, the DCE trade group that has been reaching out to lawmakers. Tenet Healthcare, a massive hospital operator, spent more than $4 million alone lobbying on a variety of issues this year, including direct contracting.

To beat back such well-funded efforts, opponents need to muster public outrage. But DCE opponents say it’s been slow going trying to get the national press to cover the issue, and even now, it continues to fly largely under the radar, with only a handful of mainstream outlets covering it. Should the issue pick up more champions in Congress, and inspire more coverage in the press, Americans learning about the risks of direct contracting may be inspired to pick up the phone and demand to their local representatives that CMS gets its government hands off their Medicare.

Joe Biden was elected on the promise of building on the progress of the Great Society. We may have to settle for simply preventing him from gutting one of its greatest legacies.

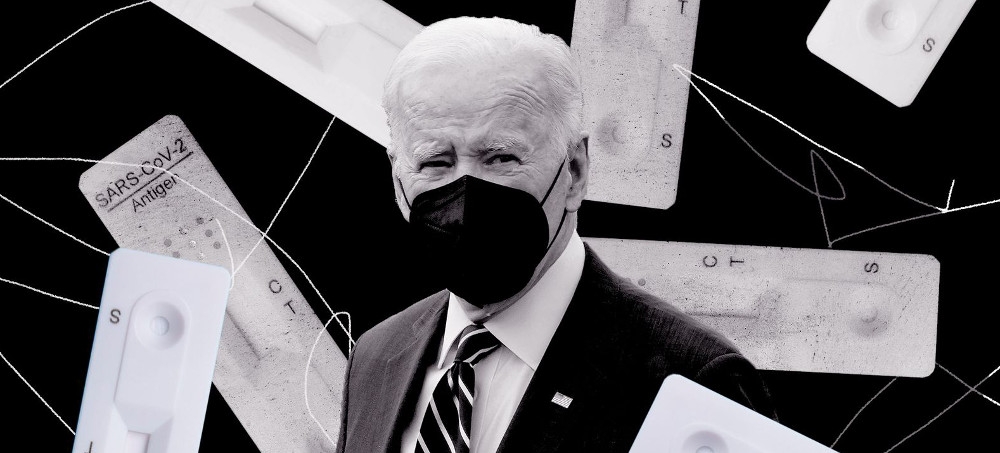

While campaigning, Biden said the U.S. needed the testing equivalent of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's War Production Board. (photo: Andrea Wise/ProPublic)

While campaigning, Biden said the U.S. needed the testing equivalent of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's War Production Board. (photo: Andrea Wise/ProPublic)

The day after his inauguration, President Joe Biden signed an order creating a Pandemic Testing Board, which he said would be modeled on FDR’s hugely successful Wartime Production Board. A year later, there’s little sign of Biden’s initiative.

That board had sweeping powers to shift the country’s economy to support the war effort, and it ultimately oversaw a reported 40% of the world’s munition production during World War II.

“It’s how we produced tanks, planes, uniforms, and supplies in record time,” the Biden campaign website said. “And it’s how we can produce and distribute tens of millions of tests.”

The day after his inauguration, Biden signed an executive order creating the Pandemic Testing Board. He said he would be putting the “full force of the federal government” behind expanding testing.

A year later, though, it’s remarkably hard to tell what the board has done.

As far as we can find, the group has put out no press releases, held no hearings and made no announcements. Biden’s executive order states that the head of the board would be, or be chosen by, the White House’s head of COVID-19 response. That’s Jeffrey Zients, but when we contacted him, he didn’t respond.

When we asked White House officials about the Pandemic Testing Board — who was on it and what actions it had taken — they declined to answer our questions and pointed us to the Department of Health and Human Services.

That agency did respond to our inquiries about the board, but its answers offered few details about the board’s work. It did not say who is on the panel or what decisions it has made.

“The Pandemic Testing Board serves as the forum where agencies across the federal government which are involved in testing can describe emerging challenges and what they are learning,” the agency said. “It provides a mechanism for addressing policy and implementation issues regarding the supply and distribution of tests, as well as increasing access to and affordability of tests in the community.”

The agency’s full statement also notes that the board has met regularly and has been split into two groups, one focused on test supply and the other on testing policies.

Public health experts told us they, too, hadn’t heard much about the board.

“I had assumed that they jettisoned these plans,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and professor at Johns Hopkins University. “If it still exists, it is certainly very low profile,” said Lawrence Gostin, a professor of global health law at Georgetown University. The country’s first coronavirus testing czar, Adm. Brett Giroir, said he knew little about it as well. “It is rumored to have met, but I did not see public disclosure or reports from the meetings.”

Of course, the inner workings of a board are less important than whether the government is getting the job done. But as ProPublica detailed in November, the Biden administration has been slow to roll out wider testing — just what the board was created to do.

In October, White House officials reportedly disregarded a proposal from testing experts to send rapid tests directly to Americans in anticipation of a COVID-19 spike during the holidays. Press secretary Jen Psaki also infamously dismissed the idea in a December briefing.

Later that month, the Biden administration announced it would send tests directly to Americans. But the tests are arriving just as the omicron wave is receding, and critics have argued that the effort shortchanges communities of color.

“I think it’s damn well about time,” said David Paltiel, a professor of public health at Yale University. “It’s never too late, but some of us have been screaming and yelling about the idea for more than 18 months.”

There was no shortage of money for expanding testing. As part of last year’s stimulus package, Congress appropriated nearly $48 billion for testing, contact tracing and other efforts to prevent the spread of COVID-19. That is in addition to $48 billion set aside for testing in 2020.

But just like with the board’s activities, details about where exactly the money has gone have been hard to come by. Since the Biden administration hadn’t released a breakdown, we submitted a request for specifics more than two months ago.

Sens. Richard Burr, R-N.C., and Roy Blunt, R-Mo., sent a letter on Jan. 3 asking for similar information. After Burr’s office shared what it had learned, the Biden administration sent ProPublica a one-page rundown of COVID-19 spending last week.

The allocations thus far include: $10 billion for testing in schools, $9 billion for manufacturing testing supplies, nearly $5 billion for testing uninsured individuals, and more than $4 billion for testing and mitigation measures for high-risk populations. Nearly $3.9 billion went toward free community testing at pharmacies and federally qualified health centers, and $2.9 billion went to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for expanding labs and testing capacity. More than $1.9 billion has gone toward COVID-19 testing of unaccompanied minors at the U.S.-Mexico border. About $3.6 billion is listed as simply “activities previously planned for PPPHCEA,” a reference to the 2020 Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act. The Indian Health Service received an additional $1.5 billion. Another $4.4 billion is still pending allocation.

Mara Aspinall, an Arizona State University professor and an adviser to the Rockefeller Foundation on the subject of COVID-19 testing, has been tracking HHS press releases to figure out how the stimulus funds have been spent, since the numbers are not publicly disclosed. She said testing should have been more of a focus since the beginning of the pandemic, but there’s still plenty left to do.

“There are a lot of indications that the federal government and state governments are understanding the power of the information that tests bring,” she said. “But what we can’t repeat is the error of last spring thinking it was over and therefore not continuing to focus.”

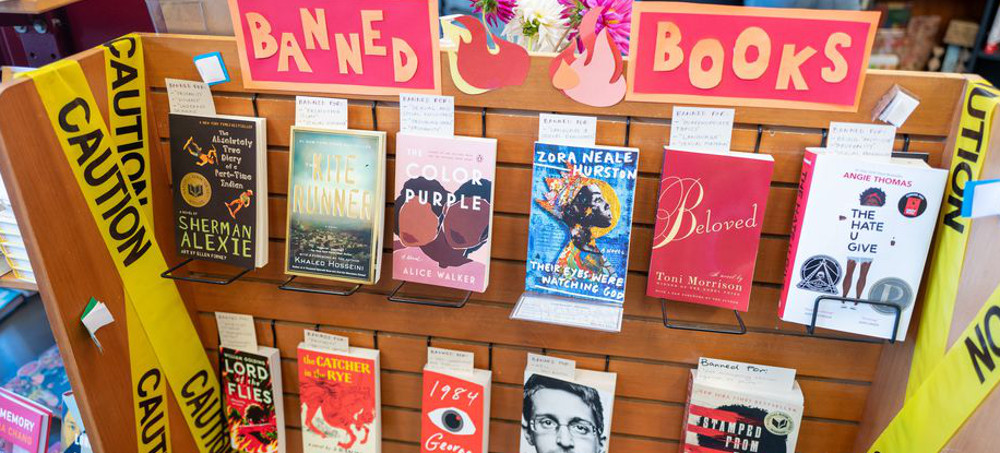

A display of banned or censored books at Books Inc., an independent bookstore in Alameda, California, October 16, 2021. (photo: Smith Collection/Getty)

A display of banned or censored books at Books Inc., an independent bookstore in Alameda, California, October 16, 2021. (photo: Smith Collection/Getty)

What’s at stake? Who gets to control the story of America.

In Tennessee, a school board yanked Art Spiegelman’s graphic Holocaust memoir Maus from the eighth grade curriculum. Last fall, a Texas legislator launched an investigation into 850 books he argued “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex,” including The Legal Atlas of the United States and Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery.” In December, a Pennsylvania school district removed the LGBTQ classic Heather Has Two Mommies from school libraries.

“There’s definitely a major upsurge” in school book bannings, says Suzanne Nossel, CEO of the free speech organization PEN America. “Normally we hear about a few a year. We would write a letter to the school board or the library asking that the book be restored, and very often that would happen.”

In contrast, Nossel says, this year she finds herself hearing from different authors by the day about their books being banned. And the bans, too, are much more forceful than they’ve been before. “Some are an individual school board deciding to pull something from a curriculum or take it out of the library,” she says. “But there are also much more sweeping pieces of legislation that are being introduced that purport to ban whole categories of books. And that’s definitely something new.”

While the extremes to which the most recent book bannings go are new, the pattern they follow is not. Adam Laats, a historian who studies the history of American education, sees our current trend of banned books as being rooted in a backlash that emerged in the US in the 20th century. That backlash, he says, was against “a specific kind of content, seen as teaching children, especially white children, that there’s something wrong with America.”

Looking at the school book bannings of the 1930s against the bannings of the 2020s can show us how history repeats itself — even when we attempt to bury our history.

“Was this country founded on liberty? This is a fundamental question.”

In the 1920s, Harold Rugg, a former civil engineer turned educational reformer, put together a highly respected line of social science textbooks. “Lively and readable, they are the most popular books of their kind, have sold some 2,000,000 copies, are used in 4,000 U. S. schools,” Time magazine reported in 1940. It added ominously: “But recently the heat has been turned on.”

“They were intended to be a more progressive take on American society,” Laats says. “The banning of those books is almost creepily familiar compared to today.”

Rugg’s textbooks brought a Depression-era sense of class consciousness to their account of American history. They asked pointed questions about how class inequality persisted so sternly across the US, and whether America really was, as advertised, the land of opportunity.

For some objectors, these were questions no one had any business asking America’s children: They were un-American, subversive, and potentially Communist. As a jingoistic patriotism spread across the country in the lead-up to World War II, school boards, facing a wave of anti-Rugg sentiment, banned and even burned copies of the textbooks.

“They went from being one of the most commonly used books in schools to becoming unfindable,” says Laats.

Rugg’s class-conscious American history didn’t emerge all on its own. It was part of a larger shift in the way the country was beginning to think about itself, says education historian Jonathan Zimmerman.

“In the early 20th century, the history profession, well, it professionalized,” says Zimmerman. “People got PhDs, they went to Germany, they learned how to do archival research. And they started to ask some different and hard questions. If the American Revolution is a fight for freedom, why are there 4 million enslaved people? Why would a third of white people be Tories and go to Canada? Some of that critique started to get into textbooks, and there was this huge backlash.”

The challenges to books that questioned America’s narrative of ideological innocence and purity didn’t only come from reactionary WASPs. “German Americans, Polish Americans, Jewish Americans, and African Americans, they are the ones that kept this out,” says Zimmerman. Groups that were in the process of clawing their way into being included in the American founding myth, after all, had a vested interest in keeping that myth going, the better to access the social capital that came with it.

“If you diminish the revolution, in their minds, you’re diminishing their respective contributions to it,” says Zimmerman.

By and large, those groups were successful. Over the course of the 20th century, the great founding myth of America has found room to include and celebrate the contributions of all sorts of groups — not just the founders, but also immigrants and women and foreign allies and people of color. But Zimmerman argues that this inclusion has by and large happened uncritically. “You put all these new groups into the story, but the title of the book is still Quest for Liberty: Rise of the American Nation,” he says.

Zimmerman argues that the most recent slew of conservative book bans is responding to a real change in the way American history is taught. That change was most famously codified by The 1619 Project, a New York Times essay series spearheaded by Nikole Hannah-Jones that reframes the American story as one beginning in 1619, when the first slave ships came to America. And this new narrative, like Ruggs’s book before it, challenges a heroic narrative of liberty and freedom in which anyone might want to be included.

“The 1619 Project is not a demand for inclusion. It isn’t,” says Zimmerman. “I mean, it’s not against inclusion, of course; those people want inclusion, but that’s not the point. It says, Okay, when we do start including, what happens to that big story? Is it a quest for liberty? Was this country founded on liberty? This is a fundamental question.”

“With the 1619 Project,” says Laats, “the core of the controversy is roughly: Is history the celebration of the founding fathers? Or is history a celebration of a broader root of freedom fighters, especially including enslaved people and Indigenous people as the true freedom fighters?” The question at stake is, Laats argues: Who are we as Americans?

“A co-option of the winning terms by the losing side”

One of the oddities of this recent round of book bannings is that it comes just after a long, outraged news cycle of conservatives arguing that the left had become too censorious, with calls to remove classics like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from school curricula and Little House on the Prairie author Laura Ingalls Wilder’s name stripped from a children’s literature award. This conversation arguably reached its peak just last year when publishers faced furious backlash from the right after sending two Dr. Seuss books out of print because of their racist imagery.

“The cancel culture is canceling Dr. Seuss,” declared Fox … Friends host Brian Kilmeade in March 2021.

The disconnect between last year’s outrage and this year’s is striking.

“If you don’t like cancel culture, so-called; if you don’t like Twitter mobs; if you don’t like protesters on campus who reject conservative speakers; that’s one thing,” says PEN’s Nossel. “But to respond to that with legislative bans on curriculum with prohibitions on certain books and ideas in the classroom is to introduce a cure that’s far worse than any disease. If you put threats to free speech in a hierarchy, there’s just no question that legislative bans based on viewpoint and ideology are at the top of the list.”

Laats argues that this sort of abrupt about-face from the right, too, is part of a larger historical pattern.

“The 20th-century pattern is pretty clear, if you take the 100-year perspective,” Laats says. “There has been progress on racial issues. It might feel depressingly stuck, but if you compare it to 1922 or even 1962, there has been progress. Same with LGBTQ rights. The difference is enormous. And with every stage of this broadening of who is considered a true American, there’s been a co-option of the winning terms by the losing side.” The anti-abortion movement is met by the pro-abortion movement; the LGBTQ rights movement on the left is met with claims of religious persecution from the right.

Laats points to Dinesh D’Souza and William F. Buckley as “masters” of this strategy. “It’s this style of conservatism that is intimately familiar with more progressive attitudes in society, in a way that more progressive pundits tend not to be as familiar with conservative ideas,” he says. “Because progressive ideas — though it might not feel like it, especially not for the last presidency — progressive ideas have become more and more dominant.”

Zimmerman and Nossel both say that conservatives’ success at banning books from schools should demonstrate that the left had become too willing to censor over the past decade.

“What I worry about is that free speech is losing its moorings on both the left and the right,” says Nossel.

“I‘m not equating the two, because this has the teeth of law, what we’re talking about now,” says Zimmerman. “A state legislature passing laws that you can’t make kids feel uncomfortable is different from Dr. Seuss getting a couple books taken off the internet.” But, he adds, there is enough of a continuity between the two cases on principle that he feels the left has put itself in a difficult strategic position. “You cannot protect Beloved if you’re purging Huck Finn,” he says.

Zimmerman says he still thinks it’s reasonable for citizens to respond to the books that are taught in schools, and even to protest them in certain cases.

“In the 1960s, there were history textbooks in this country, including in the North, that still described slavery as a mostly beneficent institution devised by benevolent white people to civilize savage Africans,” says Zimmerman. “You know why it changed? Because the NAACP and the Urban League created textbook committees that went into school boards and demanded that racist textbooks not be used.”

Zimmerman suggests that objecting to a book because of its potential to harm students, which is a subjective measure, is less effective than objecting to a book because of its untruthfulness. “Of course [the textbook committees] said the books were racist, because they were,” he says. “But they also said that they were false, which they were. To me, that’s a much more appropriate line of argument in these discussions.”

Laats argues that no matter what strategy liberals take, it’s unlikely people will stop arguing about the books we use in schools anytime soon.

“Whoever gets to control what kids are reading gets to control the definition of, quote-unquote, the real America,” he says. “That resonates with a lot of people.”

Brandon Jackson, 50, was convicted in the late 1990s by a law rooted in the Jim Crow era that allowed for a non-unanimous jury verdict. (photo: Henrietta Wildsmith/The Shreveport Times)

Brandon Jackson, 50, was convicted in the late 1990s by a law rooted in the Jim Crow era that allowed for a non-unanimous jury verdict. (photo: Henrietta Wildsmith/The Shreveport Times)

This was his second time before the board. In late 2020, he was denied parole, and his ailing mother Miss Mollie Peoples had a heart attack shortly after. “It wasn’t the cause but it helped,” Mollie told Al Jazeera.

“The heart can only take so much.”

As I watched her face at the bottom of the screen, I worried what would happen if his parole was refused this time.

Al Jazeera’s Fault Lines spent the better part of 2021 investigating Brandon’s conviction. In partnership with The Lens, a non-profit newsroom based in New Orleans, we explored every aspect of Brandon’s life and case. We learned so much and our reporting had drawn considerable publicity around his case. It felt like there might be a wind at his back this time.

Brandon was convicted by a non-unanimous jury in 1997 of an armed robbery of a restaurant in Bossier City, Louisiana. He denied any involvement.

At his trial, two of the 12 jurors were Black and they voted not guilty, but their objections did not matter.

Louisiana was holding on to a law passed in 1898 during the Jim Crow era that allowed for split juries. The law was designed to mute the voices of Black jurors and convict more Black defendants so they could be eligible as labour for convict leasing programmes.

It was stunning to us that, nearly 125 years after the law was originally passed, it was still affecting lives today. Although split juries were ruled unconstitutional in 2020, a later ruling said the state would not have to give new trials to people jailed under the law.

Contradictory testimony

Our first order of business was to comb through the court transcripts and evidence presented at the trial.

One thing stuck out to us immediately. Brandon’s defence lawyer attempted to introduce a videotape during the trial, even wheeling out a television and video player into the courtroom to get it set up.

But the tape was never played for the jury and nobody was certain what was on it. In a controversial ruling, the judge didn’t allow it to be played, citing “attorney-client privilege”.

We asked for it through a public records request and had it digitised so we could watch it.

Cameras rolling, we first watched it with Claude-Michael Comeau, Brandon’s current attorney who was overseeing his appeals based on the non-unanimous nature of his conviction.

On the tape, we immediately recognised Joseph Young, the state’s star witness at the trial. In fact, he was the only individual who identified Brandon as one of the armed robbers that night. On the tape, he directly contradicted the testimony he had delivered in court, and it was one of a number of times he was caught changing his story.

That was not the only dubious thing surrounding Young’s testimony. He was the one in possession of weapons he claimed were used in the robbery as well as some of the cash. He was given probation and, on the stand, even admitted that he was testifying in hopes of receiving a lighter sentence.

We went to Young’s home to see if he would speak to us, but he never answered the door.

Tracking down the jurors

Another crucial aspect of the reporting process for us was tracking down the jurors on the trial.

We had a polling slip with the names of the 12 jurors, but the trial happened so long ago that we were not sure we would be able to locate them. In fact, we found obituaries for several of the jurors who had died and it was not looking good.

We were able to reach one woman on the phone who had voted against convicting Brandon but all of my subsequent phone calls went to her voicemail.

So we went to Shreveport to try to meet her but when we knocked on her door, there was nobody home. Things were looking bleak. We returned the next evening and, to my surprise, she opened the door.

“I am not interested in taking part in your project,” she said as she started to close the door on us.

Then out of nowhere Fault Lines correspondent Natasha Del Toro asked: “Do you like seafood?”

The door remained open a crack. I explained that if she would just meet us for dinner we could explain more about the project and she would not need to commit to doing an on-camera interview with us.

Later that evening, we broke bread with a round of Bloody Marys and the famous fried “shrimp buster” at Herby K’s, a Shreveport institution that has been around since the 1930s.

She later explained her hesitancy to us. She was worried that if her bosses found out that she was speaking out about this conviction, there could be blowback for her at work.

“They think a lot like the people on the jury did: ‘He’s a criminal, let’s get him off the street. Let’s lock him up … Or maybe, even, he’s a Black man, let’s lock him up,’” she told us.

When she was younger, she had an encounter with the Ku Klux Klan in Bossier Parish that she could never shake from her memory. We agreed to protect her identity and blur her name out of the documents if she would give us her account of the trial.

Hers turned out to be one of the most compelling parts of our story.

She explained that she tried to speak up in that jury room about the lack of evidence presented at the trial, but nobody would listen. Ninety-nine years after the original Jim Crow-era law was passed, it worked exactly how it was designed: The voice of a dissenting Black juror was ignored. Another Black man was being sent to prison.

Was there no way out?

We knew there was only one more person with the power to do something about Brandon’s case, and that was the Bossier Parish district attorney, Schuyler Marvin. We called his office but never heard back. So we decided we would try to track him down.

We ended up driving more than five hours from New Orleans to Bossier Parish to knock on the door of his home. He was not there, but we spoke to his daughter and explained that we were trying to reach him.

She said she would call him on our behalf and have him call us. We started the long drive back to New Orleans, and I apologised to the team. We had spent a lot of energy tracking him down and as it was late in our production schedule, we really only had that one chance to speak to him. My colleagues said not to worry – sometimes it takes weeks to get someone on camera.

But about half an hour later, Natasha’s phone rang in the car. We all looked at each other and, sure enough, it was Schuyler Marvin.

Our cinematographer Singeli Agnew scrambled to turn the microphone on and get the camera rolling. Natasha turned on her speakerphone and we filmed the interview while she was driving. She asked him why he refused to look at Brandon’s case, given all the evidence we had uncovered.

He claimed he knew the racist roots of the law but was not familiar with this particular case. “I’ve only been the DA for 20 years,” he said as if he was new to the job. He promised to take a look at the details and get back to us.

It was more than a month later when he finally sent us a letter saying he was not going to retry the case purely based on the non-unanimous nature of the conviction. It appeared that in this conservative corner of the state, there was going to be no way out of prison for Brandon.

Reunited with his mother

That brings us back to his parole hearing on February 11, 2022. Brandon’s fate and that of his mother was in the hands of a three-judge panel. The conversation mostly focused on Brandon’s criminal history and a disciplinary write-up he received in 2019. His record otherwise was impeccable, and he was clearly a good candidate for release.

When the judges began to reveal they were voting to grant him parole I was overwhelmed with emotion.

When we started this project I remember thinking about whether it would be possible or not to see Brandon walk free. In our conversations, Brandon and I always said that we hoped the result of our project would be to shed light on this racist practice. We were not making a claim of innocence. We were out to prove that the law that convicted him was racist and wrong. Hundreds of people still remain behind bars due to non-unanimous convictions.

We did everything we could to get more publicity for the case. The Shreveport Times and The Lens continued to cover the story after our documentary aired. We did interviews on NPR stations to try and spread the word about these convictions rooted in the Jim Crow era.

A lot of people have asked me: “Do you think Brandon would have been granted parole if it wasn’t for your story?”

The truth is, we’ll never really know. And in the end, it doesn’t really matter. Brandon was able to walk free again and hold his mother’s hand just as they had always dreamed of doing.

Workers and supporters hold signs after filing a petition requesting an election to form a union outside the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) regional office in the Brooklyn Borough of New York, Monday, Oct. 25, 2021. (photo: Kevin Duggan)

Workers and supporters hold signs after filing a petition requesting an election to form a union outside the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) regional office in the Brooklyn Borough of New York, Monday, Oct. 25, 2021. (photo: Kevin Duggan)

Workers at the Staten Island warehouse, known as JFK8, will cast their ballots between March 25 and 30, according to the Amazon Labor Union, a labor group that is seeking to represent JFK8 workers.

The election will take place in-person, in a tent outside the warehouse, the group said in a tweet. That’s a departure from the National Labor Relations Board’s protocol in recent elections. Over the past year, many union drives have taken place via mail-in ballots as a safety measure due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Amazon spokesperson Kelly Nantel told CNBC in a statement: “We remain skeptical that there are a sufficient number of legitimate signatures to support this election petition. But since the NLRB has decided the election will proceed, we want our employees to have their voices heard as soon as possible.”

An NLRB spokesperson confirmed Amazon and ALU reached a tentative election agreement.

The election comes as Amazon is in the middle of another high-stakes union drive at its Bessemer, Alabama, warehouse. The NLRB began distributing ballots to Bessemer warehouse workers earlier this month, as part of a rerun election ordered by the labor agency after it determined Amazon improperly interfered in an election held last year. Votes are set to be counted on March 28.

It also faces another potential labor battle on Staten Island. Earlier this month, ALU filed a petition to hold an election at a nearby facility, known as LDJ5.

ALU is made up of current and former Amazon employees, including Chris Smalls, a former management assistant at JFK8 who was fired in March 2020. Amazon said Smalls was dismissed as a result of violating company policies. But his firing attracted scrutiny nationwide from lawmakers and labor advocates who contended he was dismissed for criticizing workplace conditions, as well as organizing a walkout to demand stronger coronavirus safety measures.

Members of the Asian American Commission gather in Massachusetts to condemn racism. (photo: Getty)

Members of the Asian American Commission gather in Massachusetts to condemn racism. (photo: Getty)

But the recent increase in anti-Asian hate incidents in the United States has prompted him to invert part of his family’s quintessential American immigrant story. Wu, 20, has decided to seek a better life for himself elsewhere, over safety concerns that have been elevated following headlines of gruesome killings of Asian Americans in New York.

“Every single week, you see a new attack in the news,” Wu said in a phone interview from London, where he attends college. “It angers me because you can see your grandparents, your parents or aunts or uncles or cousins or brothers or sisters” in the people who were killed, he said.

On Sunday, Christina Yuna Lee, a 35-year-old Korean American woman, was found stabbed to death in her New York City apartment. The man suspected of killing Lee had followed her into the apartment building from the street, according to surveillance video. And last month in New York, Michelle Alyssa Go, 40, was killed after being pushed onto the subway tracks.

The authorities in both cases have not said the killings were hate crimes or motivated by race, but the episodes have put Asian Americans across the country on high alert, amid an increase in anti-Asian hate incidents during the pandemic. The San Francisco Police Department said last month that it had seen a 567 percent increase in anti-Asian hate-crime reports in 2021. Nationally, there was a 73 percent increase in anti-Asian hate crimes in 2020 over the previous year, according to FBI data.

The uptick has accentuated the reckoning among Asians and Asian Americans outside the country over their relationships with the United States, which for some were already fraught with concerns over political and societal issues like gun violence.

Wu attends King’s College London and had planned on returning to the United States after graduating. But “with how things are shaping out, moving back has been thrown out the window,” he said.

Erin Wen Ai Chew, a 39-year-old Asian Australian woman in Sydney, often spends time in Southern California, where her husband is from. Chew said she would often be cautious in the United States — for example when walking the streets of Los Angeles alone — but “that vigilance and that safeguard will definitely go up a lot more now” with the increased concern over hate crimes.

“Being Asian, looking Asian, having a Chinese background,” Chew said, “all of these things do not play in our favor at the moment.”

Elderly Asian Americans have been the victims of attacks throughout the pandemic, and last week, a South Korean diplomat was punched in the face in New York City in an unprovoked attack, police said. In March, eight people — mostly Asian women — were killed in a shooting rampage across spas in the Atlanta area. Authorities in the case were initially hesitant to label the attack as racially motivated, though prosecutors later said they would pursue hate-crime charges against the White man, Robert Aaron Long, accused in the killings.

To be sure, the United States is still a desired landing point for Asian immigrants. Among recent immigrants to the United States, Asians are the second-largest ethnic group and are projected by the Pew Research Center to be the largest by 2055. Asians who live in other rich countries have the luxury of declining economic opportunities in the United States that those in less wealthy nations may yearn for.

Chew, founder of the Asian Australian Alliance advocacy group, said that while the recent killings in the United States may not have been categorized as hate crimes, stereotypes of Asian women in Western societies should be taken into account.

“The negative stereotypes that Hollywood has been putting out over a number of decades has really impacted how people view Asians as being weak, vulnerable and those that will not fight back,” she said. “And that really puts a target on how Asian Americans are seen.”

Wu, the college student, said he “wasn’t really worried” about hate crimes before the pandemic, but the Atlanta shootings and the recent killings in New York “terrified me.”

Ji-Yeon Yuh, a professor of Asian American studies at Northwestern University, said that while the United States has a long history of anti-Asian sentiment, young Asian Americans are generally less aware of it because they are too young to remember waves of violence and many schools don’t teach such history.

“The anti-Asian violence and the overall increase in blatant racism in the United States has probably pushed [some Asian Americans] to take offers [abroad] that they might not have otherwise, or extend their stay” if they are already living outside of the country, she said.

“For a lot of people who have lived here for a while, you get used to living without that,” Jane Jeong Trenka, who was born in South Korea and raised in the United States before moving back permanently in 2005, said of the tension in the United States. She recalled an incident when she last visited, in 2013, in which a man pounded on her car window, “telling us to go back to our own country.”

“You don’t even realize how comfortable you are,” Trenka said, “until one day you kind of think about having to go back to the United States, and you’re like, ‘Hell, no. Why would I put up with that every day again?’ ”

“Sometimes I feel a little bit lost,” Wu, who had not previously lived in Britain and has no family in Europe, said of his decision not to return to the United States.

“I feel like I’ve chosen a hard path,” he added. “But it’s not one that’s unfamiliar. Because this is what my parents did.”

Visitors walk through Chaco Culture National Historical Park. (photo: Getty)

Visitors walk through Chaco Culture National Historical Park. (photo: Getty)

Federal data reveal the plan does little to stop drilling and may push future development into Indigenous communities.

“It is not difficult to imagine centuries ago children running around the open space, people moving in and out of doorways, bringing in their harvest or preparing food for seasons to come,” Haaland said of the Chaco complex, where multi-story ruins rise from the floor of a wide canyon. “We’re here because President Biden and I heard your voices and are taking important steps to take care of our land, our air, and our water.”

Haaland’s speech came days after the Department of Interior announced it was considering a 20-year moratorium on new federal oil and gas leasing within a roughly 10-mile radius around the park, an approximately 950,000-acre area referred to as the buffer zone. Along with shielding the site from fracking facilities that have encroached on the area in recent years, the action was touted as part of the Biden administration’s larger effort to curb greenhouse-gas emissions while promoting environmental justice and tribal consultation.

But a review of federal leasing data by Grist suggests that the protections are a superficial fix, as they will likely do little to impede the recent influx of oil and gas development. Although the federal government plans to prevent new leasing on hundreds of thousands of acres within the Chaco buffer zone, oil and gas companies with existing leases can continue to extract minerals within its boundaries.

According to data provided by the Bureau of Land Management, there are 310 active wells on 88 active federal leases covering nearly 100,000 acres within the buffer, and federal protections do nothing to stop the companies holding those leases from obtaining permits to drill more. That means that even under the agency’s plan, hundreds of new wells could be drilled in the area at any time in the future.

“There’s still going to be development going on in that 10-mile buffer, and there’s nothing to prohibit that,” said Carol Davis, director of Diné CARE, a Navajo-led environmental organization. Davis adds that the Interior’s moratorium could push drilling outside the buffer and into communities, “and that’s going to expose people to the adverse health impacts that are a result of oil and gas fracking.”

In fact, BLM is also considering a plan that could allow up to 3,100 new wells to be developed outside the buffer zone, adding to the roughly 21,000 active wells in the region.

Several miles east of the buffer, the BLM has also approved dozens of drilling permits near a series of mesas considered sacred by the Navajo Nation. Despite conducting an environmental review that projected one well per parcel, BLM has already approved at least 118 drilling permits on eight of those parcels, according to legal documents filed by Diné CARE.

“There is absolutely zero restraint from the Bureau of Land Management and the Biden administration at this point,” said Jeremy Nichols, climate and energy program director with WildEarth Guardians. “The mineral withdrawal is good politics — it’s good optics — but it’s not going to turn the tide because there are existing leases within the buffer, and outside the buffer it’s business as usual.”

A thousand years ago, Chaco Canyon was a bustling, central trade hub. The ancestral Puebloans built monumental “great houses” along the margins of the high-desert valley and conducted trade using an expansive network of roads. The largest of the ancient structures at the UNESCO World Heritage Site likely contained more than 600 rooms and took three centuries to complete. Chaco flourished between 850 and 1250 AD, before being abandoned.

Contemporary Pueblos are the descendants of the ancestral Puebloans that built Chaco, and although they no longer inhabit the same area, many Pueblo people retain a cultural and spiritual connection to the sandstone structures and other sites dispersed throughout the region. The outlying areas are now home to Navajo families who reside either on the sparsely populated plateau, or in the tiny towns that dot the landscape, like Nageezi, Counselor, and Ojo Encino.

In the 1920s, natural gas deposits were discovered in the basin, and by the early 2000s, fossil fuel extraction occurred throughout the region. Then, around 2010, with the advent of new hydraulic fracturing methods, such as horizontal drilling, fracking began in earnest in the southern part of the basin, near the Chaco ruins, where companies tapped into oil and gas deposits that were difficult to access using vertical drilling techniques.

Many of those new wells were concentrated on public lands managed by the BLM, which owns a large portion of land surrounding Chaco Canyon, along the eastern edge of the Navajo Nation. Ownership of lands in the area is often referred to as a “checkerboard” of federal, state, private and tribal lands. Some of those tracts are also so-called “Indian allotments,” lands which the federal government distributed to individuals and families as a way to break up reservations and assimilate Indigenous people by making them landowners. Between 2014 and 2019 alone, the BLM approved more than 350 drilling permits in the greater Chaco region.

In the mostly Navajo communities that make up the area, the drilling boom resulted in wells that are in some places a few hundred feet from homes. A cluster of wells releases toxic emissions less than 2,000 feet from the Lybrook Elementary School, where an almost entirely Native American student population is exposed to a rotten-egg odor of hydrogen sulfide, a byproduct of the frequent flaring that occurs when excess gas is burned off to avoid methane emissions.

In 2019, New Mexico legislators, including then-U.S. Representative Haaland, introduced the Chaco Cultural Heritage Area Protection Act, which would have banned oil and gas leasing within a buffer zone permanently. The bill passed the House but died in the Republican-controlled Senate. Once Haaland was appointed Secretary of Interior, she took matters into her own hands, crafting the 20-year withdrawal proposal, which went into effect in January.

But companies currently operating within the buffer could still obtain permits to drill one, or multiple, wells on a given parcel. Based on the average number of wells on each active, federal lease in northwestern New Mexico, the existing leases inside the buffer could see more than 200 additional wells in the future. And that potential well count excludes the development that could occur on the much smaller portion of land within the buffer consisting of state and private land, as well as Indian allotments.

Because Indian allottees can lease their lands to oil and gas companies for royalty payments, the Chaco proposal became a point of contention in the region. Many Navajo allottees were concerned that the leasing ban would affect their royalty payments or eliminate their ability to lease out their lands, leading to opposition that ultimately resulted in the Navajo Nation withdrawing from the proposal after initially signaling support. According to the BLM, the withdrawal will not affect the ability of allottees to lease their land for oil and gas interests.

“We are not a monolith, and there were dissenting voices among allottees,” said Mario Atencio, a member of Diné CARE whose family owns an allotment just outside the buffer. He added that the most vocal opponents “claimed to represent allottees, but they don’t represent me.”

In the past year, Diné CARE and WildEarth Guardians have filed multiple legal challenges against the BLM for its approval of hundreds of lease sales and drilling permits in the greater Chaco region, including more than 100 permits issued to EOG Resources, a former Enron affiliate that amassed 40 parcels covering 45,000 acres of public land under the Trump administration.

“Right now, they’re bulldozing a road in a very sacred place,” Atencio said. He added that the lack of tribal consultation “feels no different than the Trump administration.”

Among the groups’ concerns is that BLM’s Farmington Field Office continues to allow drilling based on an outdated resource management plan, a document that forecasts the pace and scale of future oil and gas development. Because the plan was created in 2003 — before the advent of horizontal drilling — the groups argue that BLM has had no way of analyzing the “increased risks and impacts” of the new drilling technologies.

A proposed amendment to the plan estimates that between 2,300 and 3,100 new wells could be developed in the area over the next 20 years.

“That’s not a cap on what [BLM] can approve. That’s just what their best guess is,” said Kyle Tisdel, an attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center. “And the problem is that they’re just doing whatever industry says that industry wants to do.”

When the Interior Department announced the 10-mile buffer around Chaco in November, Haaland emphasized that the withdrawal would coincide with an “honoring Chaco” process that would include formal consultations with tribes and a series of ethnographic studies exploring the area’s cultural history. Pledges to engage in meaningful tribal consultation are often met with distrust in Indigenous communities given the federal government’s horrendous track record when it comes to considering human rights and tribal sovereignty. But the historic appointment of Haaland, who is a member of the Laguna Pueblo, gave many Indigenous people hope that their voices would finally be heard.

Julia Bernal, director of Pueblo Action Alliance, spent the past five years fighting for federal protections against fracking in the Chaco region. And while Bernal believes more should be done to protect the environment and public health in the area, she said the Interior Department’s stated commitment to incorporating Indigenous knowledge and studies is “unprecedented,” and a credit to Haaland’s investment in the issue.

“Based on my own conversations with [Haaland], it’s not like she has the ability to implement extreme change even though she’s in this position,” Bernal said. “It’s always hard to convey why land and water and air are culturally and spiritually important, and not just for economic gain.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.