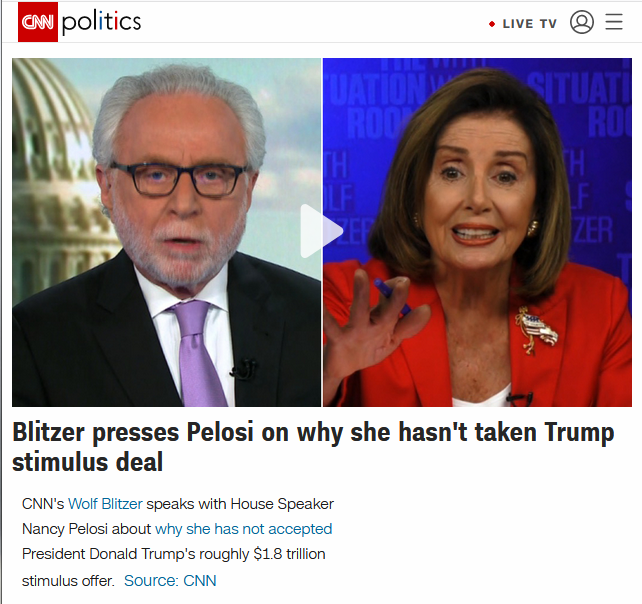

Both-Sidesing the Stimulus BillJULIE HOLLAR ![]()  The Washington Post caption (12/20/20) reads: "Senate leaders on both sides of the aisle each blamed the other for the long stint between the last coronavirus relief package and the deal reached December 20." When politicians know that blame will always be apportioned equally, they will have no fear of paying a political price for obstructionism. Nearly nine months after the CARES Act, Congress has finally passed a second economic stimulus. The bill, with a price tag of about $900 billion, falls far short of what Democrats and most economists say is necessary, as a result of continual Republican insistence that aid not reach the $1 trillion mark. But to hear corporate media tell it, the too little, too late stimulus story has been largely another example of both parties' intransigence. Way back in May, just two months after the $2 trillion CARES Act was enacted, House Democrats passed a $3 trillion follow-up stimulus that would have extended the initial act's $600 weekly unemployment benefits through January, provided a second round of direct $1,200 payments to individuals, offered $1 trillion in direct aid to state, local and tribal governments, expanded small business loans, and funded coronavirus testing, tracing and treatment. In July, Republicans responded to Democrats' May bill with a $1 trillion counter-offer, which included a corporate liability shield to prevent lawsuits against businesses that failed to make reasonable efforts to protect workers. Democrats passed a trimmed-down $2 trillion compromise bill in October. While the Senate never actually passed a follow-up bill for the House to consider, Republican Senate leaders declared the House legislation dead on arrival. Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell accused Speaker Nancy Pelosi, who seemed close to reaching an agreement with Trump Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin over the $2 trillion proposal, of negotiating in bad faith—essentially, trying to offer desperately needed aid to Americans as a way of causing rifts in the GOP, when they had much more important things to worry about, like confirming a rabidly right-wing Supreme Court justice to replace Ruth Bader Ginsburg—and declared that he wouldn't give the bill a floor vote, insisting at the time on a dramatically narrower $500 billion bill (The Hill, 10/15/20).  CNN's Wolf Blitzer (10/13/20) weighs in on the side of President Trump against Nancy Pelosi. While many outlets reported on McConnell's obstruction (e.g., Washington Post, 10/20/20), the mediascape still tended to fall back on blaming both sides, as in this CNN analysis by Matt Egan (10/27/20): The fragile economic recovery is losing steam. The pandemic is getting worse again. The risk of post-election chaos has never been higher. And yet lawmakers in Washington won't agree to a fiscal rescue package that is so obviously needed. Both sides of the aisle are betting they'll avoid the wrath of voters, despite this historic failure. The livelihoods of countless Americans will be worse off because of this political roll of the dice.

Some even blamed Pelosi for stymieing relief, as when CNN's Wolf Blitzer (10/13/20) lectured her for not accepting the GOP's insistence on the corporate liability shield, which would let companies off the hook for unethical practices that led, in some cases, to worker deaths: "Even members of your own caucus, Madame Speaker, want to accept this deal." The long history of McConnell's intransigence went completely down the memory hole when negotiations began again in earnest in recent weeks, with media reports replete with references to "lawmakers trad[ing] blame" (e.g., New York Times, 12/16/20; Washington Post, 12/10/20), but much less so with direct explanations of who has actually blocked relief. At the Post, the main subjects of the story were "bickering," "finger-pointing" and unidentified "lawmakers," rather than actual individuals or any party in particular: Congressional bickering over a new economic relief package escalated Thursday as lawmakers traded blame and put negotiations over critical legislation on the brink of collapse. And the finger-pointing even threatened to imperil a must-pass spending bill in the Senate, as lawmakers were still unsure whether they would be able to pass a measure by a deadline Friday night to avert a government shutdown.

Similarly, one Times story (12/8/20) explained that "the logjam over a new stimulus package—with negotiators intent on playing hardball rather than compromise—has been a constant source of frustration," while another (12/2/20) put the classic both-sides spin on it: For months, Republicans have blamed Democratic leaders for insisting on the expansive plan and blocking smaller pieces of aid—like new loans for small businesses—from advancing. Democrats have accused Mr. McConnell of blocking an agreement and failing to compromise.

It's not clear that McConnell would have agreed to anything this time around if not for the Georgia Senate runoffs, which will determine control of the Senate. In a private call reported by the Times (12/16/20), McConnell made the case to fellow Republicans that they needed to pass a stimulus, and to include direct cash payments, because the party's candidates in Georgia were "getting hammered" by their Democratic opponents for the GOP's failure to act. In other words, not because the American people are getting hammered by unemployment, poverty and Covid, but because Republicans might lose their ability to do things like block more generous aid in the future. In the final "compromise" stimulus bill, Republicans gave an inch while Democrats gave a mile, with the result coming in under $1 trillion—almost exactly what the GOP initially proposed back in July—with a good portion of it clawed back from unused funds in the original CARES Act. As Sen. Bernie Sanders told Politico (12/14/20): “What kind of negotiation is it when you go from $3.4 trillion to $188 billion in new money? That is not a negotiation. That is a collapse." (Estimates place the total new money in the final bill at around $350 billion.) The only major item from the Republican wish list that Democrats succeeded in blocking was the corporate liability shield, which, while an important victory, still leaves the final outcome far short of what most economists say would be necessary to even begin to address current needs. It offers only $300 per week of extended unemployment benefits, and for only 11 weeks; the original compromise bill had it at 16 weeks, but to keep the total cost under $1 trillion to satisfy Republicans, negotiators stole from unemployment benefits to help fund the new round of stimulus checks. At the Washington Post (12/20/20), a caption under a brief video of statements by McConnell and Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer explained that "Senate leaders on both sides of the aisle each blamed the other for the long stint between the last coronavirus relief package and the deal reached December 20." Nowhere in the article did the reporters give any indication of where that blame might most appropriately lie. Readers of the Reuters version of the story (12/21/20) would have basically no idea what was at stake or who was responsible: Lawmakers set aside issues that had frozen negotiations for months, including liability protections sought by Republicans and state and local government aid sought by Democrats. A last-minute dispute over emergency-lending programs administered by the Federal Reserve was also resolved.

It's not "the perils of sustained Washington inaction" that left "governors and mayors on the ropes," as the Washington Post (12/19/20) had it, but the insistence of Republican Senate leaders that aid to states and cities not be part of the follow-up Covid relief bill. Even when describing how dire the economic pain around the country could be from jettisoning state and local aid papered over the blame for such pain, outlets featured the passive voice in their headlines and peppered it throughout their articles: "Aid to States and Cities Likely to Be Cut Out of Stimulus Deal, Leaving Governors and Mayors on the Ropes," announced the Washington Post (12/19/20), which warned of "the perils of sustained inaction by Washington." No doubt in part as a result of such reporting, more members of the public—despite overwhelmingly opposing the major sticking point for Senate Republicans, the liability shield—see Democrats as responsible for "delays in the passage of additional coronavirus stimulus and aid," according to a December Data for Progress poll (12/6/20). It's not just Republican respondents; only 21% of independents picked Republicans over Democrats (27%) or "both" parties (43%). It's hard to imagine such numbers if more outlets reported on the stimulus negotiations with the candor of a recent analysis by Jordan Weissmann in Slate (12/18/20), which carried the headline, "Republicans Are Fighting Hard to Bankrupt States." And the implications reach far beyond the immediate economic impacts of the current stimulus bill. If the Republicans take even one of the two Georgia runoff races, McConnell will continue to control the Senate, which would mean Biden's ability to offer more needed aid in the future would be strictly limited. The Georgia runoffs, in other words, are about much more than simply control of the Senate; that control will determine what kind of relief people get as our long Covid winter drags on—which is yet another thing the media haven't been forthcoming about. In the Washington Post, "What You Need to Know about the Georgia Senate Runoff Elections" (12/17/20) gave a rundown of the who, what, when and why, plus things like "How these races will determine control of the Senate." What was missing was any mention of the very concrete implications of Senate control, and how they might impact readers' lives, which is exactly what McConnell is counting on to keep his party from getting hammered in that special election. |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.