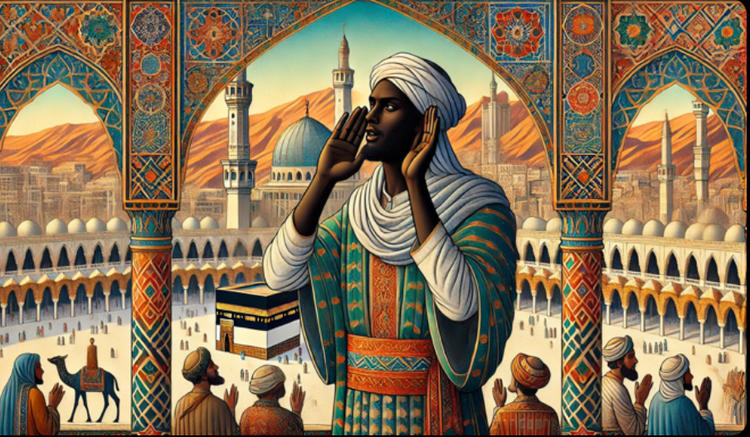

The Qur’an’s Celebration of Diverse Skin Colors: Forms of Equality in the Muslim Scripture I am reprinting part of this essay that appeared in Renovatio, the literary magazine of a small Muslim liberal arts college — Zaytuna — in Berkeley, Ca. The Qur’an is the most hated book in America that no one has ever read, and there are already new visa bans on Muslims deriving from severe misunderstandings […] |

The long struggle in the United States for racial equality, which has thrown up memorable and impassioned phrases, such as “We shall overcome,” “I have a dream,” and “Black lives matter,” has sought procedural equality for minorities, who systematically have been treated differently from the white majority by police. In this light, it has struck me that the Qur’an is remarkably uninterested in any distinction between the self and the barbarian, or between white and black. The world of late antiquity, to which the Qur’an was preached, was on the whole hostile to the idea of equality. The rise from the fourth century of a Christian Roman Empire under the successors of Constantine did nothing to change the old Greek and Roman discourse about civilized citizens and “barbarians.”1 In Iran’s Sasanian Empire, Zoroastrian thinkers and officials made a firm distinction between “Iran” and “not-Iran” (anīrān), and there was no doubt for Sasanian authors that being Iranian was superior in every way. Still, these civilizations at the same time transmitted wisdom about human unity. Socrates cheekily pointed out that pretenders to the robes of Greek nobility had countless ancestors, including the indigent, slaves, and barbarians as well as Greeks and royalty (Theaetetus 175a). Zoroastrian myth asserted that all mankind had a single origin in the primal man, Gayomart. The Qur’an was recited by the Prophet Muĥammad in the early seventh century, on the West Arabian frontier of both the Eastern Roman Empire and Sasanian Iran. In Arabian society of that period, one sort of inequality was based on appearance and on a heritage of slavery. Children of Arab men and slave women from Axum (in what is now Ethiopia) remained slaves and were not acknowledged by their fathers. Those who became poets were called the “crows of the Arabs.”2 Some sorts of hierarchy are recognized in the Qur’an, but they are not social or ethnic. Rather, they are spiritual. In late antiquity, those who argued for equality did not necessarily challenge concrete social hierarchies but rather concentrated on principle and on the next life.3 For Islam, as for Christianity, it is ethical and moral acts of the will that establish the better and worse (though the Qur’an does urge manumission of slaves as a good deed and promulgates a generally egalitarian ethos). The Qur’anic chapter of Prostration (32:18) says, “Is the believer like one who is debauched? They are not equal.” The two are not on the same plane, not because of the estate into which they were born or because one is from a civilized people and the other a barbarian but because of the choices they have made in life. In short, this kind of inequality is actually an argument for equality. The Chambers (49:13) observes, “The noblest of you in the sight of God is the most pious of you.” This is a theme to which we will return.

Reading the Qur’an requires attention to what scholars of literature call “voice.” It switches among speakers with no punctuation or transition. Sometimes the omniscient voice of God speaks, but sometimes the Prophet does, and sometimes angels do or even the damned in hell. In chapter 80 (He Frowned), the voice of God addresses the Prophet Muĥammad personally, using the second-person singular. The passage is a rare rebuke of the Messenger of God by the one who dispatched him. In my translation, I have used small caps for the pronouns referring to Muĥammad. Initially, the divine narrates Muĥammad’s actions in the third person, but then God speaks directly to His envoy about delivering the scripture, here called “the reminder”:

The great historian and Qur’an commentator Muĥammad b. Jarīr al-Ţabarī (d. 923) quoted the Prophet’s third wife,`Ā’ishah, on the significance of this passage. She said, “‘He Frowned’ was revealed concerning Ibn Umm Maktūm. He came to the Messenger of God and began to say, ‘Guide me.’ The Messenger of God was with pagan notables. The Prophet began to turn away from him, addressing someone else. The man asked [plaintively], ‘Do you see any harm in what I say?’ He replied, ‘No.’” Despite his being blind, `Abd Allāh b. Umm Maktūm was later made a caller to prayer in the Medina period, according to another saying of`Ā’ishah. The man’s name underlines his marginality in Arabian society of that time. He is the son (Ibn) of “the mother (Umm) of Maktūm (his older brother).” Arabian names were patriarchal like those of the Norse, for instance “Erik Thorsson.” It was an embarrassment to lack a patronymic, to be defined only by one’s mother’s name. The blind`Abd Allāh b. Umm Maktūm would have been named with regard to his father if anyone had known who the latter was. Thus, he was a person of no social consequence in the small shrine city of Mecca. The plain sense of these verses is clear, whether this anecdote is historical or not. The Prophet is scolded by the voice of the divine for having turned his back, annoyed, when the blind nobody dared make a demand on his time and attention. What is worse, `Abd Allāh did so while Muĥammad was giving his attention instead to a gathering of the wealthy Meccan elite—those who thought they were “self-sufficient” and did not need God’s grace. The voice of the divine points out that Ibn Umm Maktūm’s soul was just as valuable as the souls of the pagan magnates, and it was possible that, with some pastoral care, he might accept the truth. The Prophet Muĥammad preached, according to the later Muslim tradition, from 610 to 632, and this incident is thought to have occurred early in his ministry. Was it 613? It is implied in the Qur’an that God intervened right at the beginning of Muĥammad’s career to underscore that the mission work had to proceed on the basis of the spiritual equality of all potential hearers. Skin color was used in many ways by authors in the ancient world and not always as a sign of inferiority or superiority, but there were undeniably forms where discrimination played a part. When the widely read Greek medical thinker Galen at one point described “Ethiopians,” he mentioned their outward attributes, such as frizzy hair and broad noses, but then went on to describe them also as mentally deficient.4 Solomon’s bride in the “Song of Songs” describes herself as black: “I am black and beautiful, O daughters of Jerusalem, like the tents of Kedar, like the curtains of Solomon.” This description caused late antique Christian authors some puzzlement, since they did not associate blackness with beauty or other positive attributes.5 The ancient world did not have a conception of race, a modern idea that emerged in its contemporary sense in the nineteenth century; it only had a set of aesthetic preferences around appearances. But some authors clearly did invest blackness with negative connotations. About the AuthorDeath shaded the Life of this Holocaust historian. The cancer Memoir he began in Hospital was a final ‘Act of Love’ By Tess Scholfield-Peters, University of Technology Sydney (The Conversation) – Mark Raphael Baker began writing his final book, A Season of Death, from his hospital bed, in the wake of his terminal pancreatic cancer diagnosis. His second wife, Michelle, would later observe: “More than a comfort or distraction, in him it was a need.” The […] |

By Tess Scholfield-Peters, University of Technology Sydney (The Conversation) – Mark Raphael Baker began writing his final book, A Season of Death, from his hospital bed, in the wake of his terminal pancreatic cancer diagnosis. His second wife, Michelle, would later observe: “More than a comfort or distraction, in him it was a need.” The renowned Jewish Australian author and academic died a year later, after 13 months of illness, aged 64. In 2022, after nearly four months of misdiagnoses and inaction from doctors – despite persistent complaints of unbearable abdominal pain – an MRI had finally revealed the grave news. Cancer would claim his life, as it had his first wife Kerryn in 2016 (aged 55), and his brother Johnny in 2017 (aged 62). He wrote:

How does one write the essence of a life once it has come to an end? Baker was no stranger to this question. Review: A Season of Death – Mark Raphael Baker (Melbourne University Press) His first book, The Fiftieth Gate: a journey through memory (1997), is an exploration of his parents’ Holocaust survival, told through the eyes of a son grappling with his connection to their trauma. When it was reissued for its 20-year anniversary in 2017, it had sold over 70,000 copies. His second book, Thirty Days: A Journey to the End of Love (2017), was written after his first wife, Kerryn, lost her ten-month battle with stomach cancer. Death shaded much of Baker’s life. Writing was his salve, a window to understanding and hope. Baker was director of the Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation and associate professor of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Monash University. Religion, which was central to his family and intellectual life, is woven throughout the memoir. Liminal grief

A Season of Death is short, at 253 pages. It is structured in five parts: Regeneration, Remarriage, Re-Creation, Retribution and Revelation. The repeated prefix “re” (meaning again, or back) speaks to the cyclical nature of life as Baker lived it. The book begins with Kerryn’s cancer diagnosis, seven years prior to his own. Baker writes, “That experience followed me; every breath I took felt like Kerryn’s last breath.” He continues:

Baker writes beautifully and eloquently about the liminality of existing in grief after such a profound death. Less than two years after Kerryn’s passing, Baker’s brother, Johnny, also died of cancer. This death was particularly difficult for Baker’s parents, who both survived the Holocaust. For many survivors of genocide – who’ve lost their family, their sense of place, everything – children become the centre of their universe. This was certainly the case for Baker’s parents:

‘Something was seriously wrong’

The book is written in a fragmented style, traversing past and present, shimmering between early childhood memories and life as an adult. We are with Baker through his courting of Michelle Lesh, who he had first known as the stepdaughter of his close friend, Raimond Gaita. Their relationship transformed and deepened through their shared intellectual and political interests, particularly concerning Israel-Palestine, and centred around travel and their respective careers. They were married in 2018 and in 2021 welcomed a daughter, Melila.

We are with him as he reflects on his parents’ survival of Holocaust Europe and the trauma they experienced. (Baker’s father died in 2020, three years after his brother Johnny. Baker’s mother, Genia, was 88 when he died in 2023.) And we are with him in the doctor’s office as his worst fear becomes reality.

For anyone touched by cancer, this feeling of bewilderment is familiar. Few diseases have a more profound physical and psychological impact. Baker observes, often with searing clarity, his own corporeal degeneration and his thoughts as he confronts his own mortality. “While no number of deaths could make me indifferent to what awaits me, watching a sequence of deaths in the family has made me more prepared,” he writes.

What is surprising is Baker’s persistent humour and palpable energy, despite the pain and despite the closeness of his ultimate demise. An act of love

A Season of Death is not an easy read. It is an intimate, at times harrowing portrait of grief and of death. What Baker has written is a final observation of his life, offering a rare perspective on death – and life as it comes to an end. To persevere with a writing project in the midst of such bodily trauma, to write through and towards death for his children, for his family and descendants, is an incredibly courageous feat. “Over the course of his illness Mark wrote almost every day, despite the ravages and debilitating side effects of his treatments, which often left him weary in body and mind,” write Lesh and his friend Raimond Gaita, in the book’s postscript. Baker passed away before the book was published, and Lesh and Gaita brought it to publication in his absence. In their postscript, they observe:

What lingers with the reader is a sense of the fragility and miracle of being alive for the very short time we each have. We are all going to die, and whether or not this fact is a preoccupation, it is moving to witness, through writing, an at once introspective and philosophical mind work through his imminent death.

Tess Scholfield-Peters, Casual Academic, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. About the AuthorThe Alarming Findings of AI Model that analysed Millions of Images of retreating Glaciers By Tian Li, University of Bristol; Jonathan Bamber, University of Bristol, and Konrad Heidler, Technical University of Munich (The Conversation) – The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average since 1979. Svalbard, an archipelago near the northeast coast of Greenland, is at the frontline of this climate change, warming up to […] |

By Tian Li, University of Bristol; Jonathan Bamber, University of Bristol, and Konrad Heidler, Technical University of Munich

(The Conversation) – The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average since 1979. Svalbard, an archipelago near the northeast coast of Greenland, is at the frontline of this climate change, warming up to seven times faster than the rest of the world.

More than half of Svalbard is covered by glaciers. If they were to completely melt tomorrow, the global sea level would rise by 1.7cm. Although this won’t happen overnight, glaciers in the Arctic are highly sensitive to even slight temperature increases.

To better understand glaciers in Svalbard and beyond, we used an AI model to analyse millions of satellite images from Svalbard over the past four decades. Our research is now published in Nature Communications, and shows these glaciers are shrinking faster than ever, in line with global warming.

Specifically, we looked at glaciers that drain directly into the ocean, what are known as “marine-terminating glaciers”. Most of Svalbard’s glaciers fit this category. They act as an ecological pump in the fjords they flow into by transferring nutrient-rich seawater to the ocean surface and can even change patterns of ocean circulation.

Where these glaciers meet the sea, they mainly lose mass through iceberg calving, a process in which large chunks of ice detach from the glacier and fall into the ocean. Understanding this process is key to accurately predicting future glacier mass loss, because calving can result in faster ice flow within the glacier and ultimately into the sea.

Despite its importance, understanding the glacier calving process has been a longstanding challenge in glaciology, as this process is difficult to observe, let alone accurately model. However, we can use the past to help us understand the future.

By Tian Li, University of Bristol; Jonathan Bamber, University of Bristol, and Konrad Heidler, Technical University of Munich

(The Conversation) – The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average since 1979. Svalbard, an archipelago near the northeast coast of Greenland, is at the frontline of this climate change, warming up to seven times faster than the rest of the world.

More than half of Svalbard is covered by glaciers. If they were to completely melt tomorrow, the global sea level would rise by 1.7cm. Although this won’t happen overnight, glaciers in the Arctic are highly sensitive to even slight temperature increases.

To better understand glaciers in Svalbard and beyond, we used an AI model to analyse millions of satellite images from Svalbard over the past four decades. Our research is now published in Nature Communications, and shows these glaciers are shrinking faster than ever, in line with global warming.

Specifically, we looked at glaciers that drain directly into the ocean, what are known as “marine-terminating glaciers”. Most of Svalbard’s glaciers fit this category. They act as an ecological pump in the fjords they flow into by transferring nutrient-rich seawater to the ocean surface and can even change patterns of ocean circulation.

Where these glaciers meet the sea, they mainly lose mass through iceberg calving, a process in which large chunks of ice detach from the glacier and fall into the ocean. Understanding this process is key to accurately predicting future glacier mass loss, because calving can result in faster ice flow within the glacier and ultimately into the sea.

Despite its importance, understanding the glacier calving process has been a longstanding challenge in glaciology, as this process is difficult to observe, let alone accurately model. However, we can use the past to help us understand the future.

AI replaces painstaking human labour

When mapping the glacier calving front – the boundary between ice and ocean – traditionally human researchers painstakingly look through satellite imagery and make digital records. This process is highly labour-intensive, inefficient and particularly unreproducible as different people can spot different things even in the same satellite image. Given the number of satellite images available nowadays, we may not have the human resources to map every region for every year.

Photo by Chris-Håvard Berge on Unsplash

A novel way to tackle this problem is by using automated methods like artificial intelligence (AI), which can quickly identify glacier patterns across large areas. This is what we did in our new study, using AI to analyse millions of satellite images of 149 marine-terminating glaciers taken between 1985 and 2023. This meant we could examine the glacier retreats at unprecedented scale and scope.

When mapping the glacier calving front – the boundary between ice and ocean – traditionally human researchers painstakingly look through satellite imagery and make digital records. This process is highly labour-intensive, inefficient and particularly unreproducible as different people can spot different things even in the same satellite image. Given the number of satellite images available nowadays, we may not have the human resources to map every region for every year.

Photo by Chris-Håvard Berge on Unsplash

A novel way to tackle this problem is by using automated methods like artificial intelligence (AI), which can quickly identify glacier patterns across large areas. This is what we did in our new study, using AI to analyse millions of satellite images of 149 marine-terminating glaciers taken between 1985 and 2023. This meant we could examine the glacier retreats at unprecedented scale and scope.

Insights from 1985 to today

We found that the vast majority (91%) of marine-terminating glaciers across Svalbard have been shrinking significantly. We discovered a loss of more than 800km² of glacier since 1985, larger than the area of New York City, and equivalent to an annual loss of 24km² a year, almost twice the size of Heathrow airport in London.

The biggest spike was detected in 2016, when the calving rates doubled in response to periods of extreme warming. That year, Svalbard also had its wettest summer and autumn since 1955, including a record 42mm of rain in a single day in October. This was accompanied by unusually warm and ice-free seas.

We found that the vast majority (91%) of marine-terminating glaciers across Svalbard have been shrinking significantly. We discovered a loss of more than 800km² of glacier since 1985, larger than the area of New York City, and equivalent to an annual loss of 24km² a year, almost twice the size of Heathrow airport in London.

The biggest spike was detected in 2016, when the calving rates doubled in response to periods of extreme warming. That year, Svalbard also had its wettest summer and autumn since 1955, including a record 42mm of rain in a single day in October. This was accompanied by unusually warm and ice-free seas.

How ocean warming triggers glacier calving

In addition to the long-term retreat, these glaciers also retreat in the summer and advance again in winter, often by several hundred metres. This can be greater than the changes from year to year.

We found that 62% of the glaciers in Svalbard experience these seasonal cycles. While this phenomenon is well documented across Greenland, it had previously only been observed for a handful of glaciers in Svalbard, primarily through manual digitisation.

We then compared these seasonal changes with seasonal variations in air and ocean temperature. We found that as the ocean warmed up in spring, the glacier retreated almost immediately. This was a nice demonstration of something scientists had long suspected: the seasonal ebbs and flows of these glaciers are caused by changes in ocean temperatures.

In addition to the long-term retreat, these glaciers also retreat in the summer and advance again in winter, often by several hundred metres. This can be greater than the changes from year to year.

We found that 62% of the glaciers in Svalbard experience these seasonal cycles. While this phenomenon is well documented across Greenland, it had previously only been observed for a handful of glaciers in Svalbard, primarily through manual digitisation.

We then compared these seasonal changes with seasonal variations in air and ocean temperature. We found that as the ocean warmed up in spring, the glacier retreated almost immediately. This was a nice demonstration of something scientists had long suspected: the seasonal ebbs and flows of these glaciers are caused by changes in ocean temperatures.

A global threat

Svalbard experiences frequent climate extremes due to its unique location in the Arctic yet close to the warm Atlantic water. Our findings indicate that marine-terminating glaciers are highly sensitive to climate extremes and the biggest retreat rates have occurred in recent years.

This same type of glaciers can be found across the Arctic and, in particular, around Greenland, the largest ice mass in the northern hemisphere. What happens to glaciers in Svalbard is likely to be repeated elsewhere.

If the current climate warming trend continues, these glaciers will retreat more rapidly, the sea level will rise, and millions of people in coastal areas worldwide will be endangered.

Tian Li, Senior Research Associate, Bristol Glaciology Centre, University of Bristol; Jonathan Bamber, Professor of Glaciology and Earth Observation, University of Bristol, and Konrad Heidler, Chair of Data Science in Earth Observation, Technical University of Munich

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Svalbard experiences frequent climate extremes due to its unique location in the Arctic yet close to the warm Atlantic water. Our findings indicate that marine-terminating glaciers are highly sensitive to climate extremes and the biggest retreat rates have occurred in recent years.

This same type of glaciers can be found across the Arctic and, in particular, around Greenland, the largest ice mass in the northern hemisphere. What happens to glaciers in Svalbard is likely to be repeated elsewhere.

If the current climate warming trend continues, these glaciers will retreat more rapidly, the sea level will rise, and millions of people in coastal areas worldwide will be endangered.

Tian Li, Senior Research Associate, Bristol Glaciology Centre, University of Bristol; Jonathan Bamber, Professor of Glaciology and Earth Observation, University of Bristol, and Konrad Heidler, Chair of Data Science in Earth Observation, Technical University of Munich

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.