Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

When a young American lights out for the territories in the second decade of the 21st century, where does he go? For John Jacobi, the answer was Chapel Hill, North Carolina — Occupy had gotten him interested in anarchists, and he’d heard they were active there. He was camping out with the chickens in the backyard of their communal headquarters a few months later when a crusty old anarchist with dreadlocks and a piercing gaze handed him a dog-eared book called Industrial Society and Its Future. The author was FC, whoever that was. Jacobi glanced at the first line: “The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race.”

This guy sure gets to the point, he thought. He skimmed down the paragraph. Industrial society has caused “widespread psychological suffering” and “severe damage to the natural world”? Made life more comfortable in rich countries but miserable in the Third World? That sounded right to him. He found a quiet nook and read on.

The book was written in 232 numbered sections, like an instruction manual for some immense tool. There were two main themes. First, we’ve become so dependent on technology that the real decisions about our lives are made by unseen forces like corporations and market flows. Our lives are “modified to fit the needs of this system,” and the diseases of modern life are the result: “Boredom, demoralization, low self-esteem, inferiority feelings, defeatism, depression, anxiety, guilt, frustration, hostility, spouse or child abuse, insatiable hedonism, abnormal sexual behavior, sleep disorders, eating disorders, etc.” Jacobi had experienced most of those himself.

The second point was that technology’s dark momentum can’t be stopped. With each improvement, the graceful schooner that sails our shorelines becomes the hulking megatanker that takes our jobs. The car’s a blast bouncing along at the reckless speed of 20 mph, but pretty soon we’re buying insurance, producing our license and registration if we fail to obey posted signs, and cursing when one of those charming behavior-modification devices in orange envelopes shows up on our windshields. We doze off while exploring a fun new thing called social media and wake up to big data, fake news, and Total Information Awareness.

All true, Jacobi thought. Who the hell wrote this thing?

The clue arrived in section No. 96: “In order to get our message before the public with some chance of making a lasting impression, we’ve had to kill people,” the mystery author wrote.

“Kill people” — Jacobi realized that he was reading the words of the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, the hermit who sent mail bombs to scientists, executives, and computer experts beginning in 1978. FC stood for Freedom Club, the pseudonym Kaczynski used to take credit for his attacks. He said he’d stop if the newspapers published his manifesto, and they did, which is how he got caught, in 1995 — his brother recognized his prose style and reported him to the FBI. Jacobi flipped back to the first page, section No. 4: “We therefore advocate a revolution against the industrial system.”

The first time he read that passage, Jacobi had just nodded along. Talking about revolution was the anarchist version of praising the baby Jesus, invoked so frequently it faded into background noise. But Kaczynski meant it. He was a genius who went to Harvard at 16 and made breakthroughs in something called “boundary functions” in his 20s. He joined the mathematics department at UC Berkeley when he was 25, the youngest hire in the university’s then-99-year history. And he did try to escape the world he could no longer bear by moving to Montana. He lived in peace without electricity or running water until the day when, maddened by the invasion of cars and chain saws and people, he hiked to his favorite wild place for some relief and found a road cut through it. “You just can’t imagine how upset I was,” he told an interviewer in 1999. “From that point on, I decided that, rather than trying to acquire further wilderness skills, I would work on getting back at the system. Revenge.” In the next 17 years, he killed three people and wounded 23 more.

Jacobi didn’t know most of those details yet, but he couldn’t find any holes in Kaczynski’s logic. He said straight-out that ordinary human beings would never charge the barricades, shouting, “Destroy our way of life! Plunge us into a desperate struggle for survival!” They’d probably just stagger along, patching holes and destroying the planet, which meant “a small core of deeply committed people” would have to do the job themselves (section No. 189). Kaczynski even offered tactical advice in an essay titled “Hit Where It Hurts,” published a few years after he began his life sentence in a federal “supermax” prison in Colorado: Forget the small targets and attack critical infrastructure like electric grids and communication networks. Take down a few of those at the right time and the ripples would spread rapidly, crashing the global economic system and giving the planet a breather: No more CO2 pumped into the atmosphere, no more iPhones tracking our every move, no more robots taking our jobs.

Kaczynski was just as unsentimental about the downsides. Sure, decades or centuries after the collapse, we might crawl out of the rubble and get back to a simpler, freer way of life, without money or debt, in harmony with nature instead of trying to fight it. But before that happened, there was likely to be “great suffering” — violent clashes over resources, mass starvation, the rise of warlords. The way Kaczynski saw it, though, the longer we go like we’re going, the worse things will get. At the time his manifesto was published, many people reading it probably hadn’t heard of global warming and most certainly weren’t worried about it. Reading it in 2014 was a very different experience.

The shock that went through Jacobi in that moment — you could call it his “Kaczynski Moment” — made the idea of destroying civilization real. And if Kaczynski was right, wouldn’t he have some responsibility to do something, to sabotage one of those electric grids?

His answer was yes, which was almost as alarming as discovering an unexpected kinship with a serial killer — even when you’re sure that morality is just a social construct that keeps us docile in our shearing pens, it turns out setting off a chain of events that could kill a lot of people can raise a few qualms.

“But by then,” Jacobi says, “I was already hooked.”

Quietly, often secretly, whether they gather it from the air of this anxious era or directly from the source like Jacobi did, more and more people have been having Kaczynski Moments. Books and webzines with names like Against Civilization, FeralCulture, Unsettling America, and the Ludd-Kaczynski Institute of Technology have been spreading versions of his message across social-media forums from Reddit to Facebook for at least a decade, some attracting more than 100,000 followers. They cluster around a youthful nickname, “anti-civ,” some drawing their ideas directly from Kaczynski, others from movements like deep ecology, anarchy, primitivism, and nihilism, mixing them into new strains. Although they all believe industrial civilization is in a death spiral, most aren’t trying to hurry it along. One exception is Deep Green Resistance, an activist network inspired by a 2011 book of the same name that includes contributions from one of Kaczynski’s frequent correspondents, Derrick Jensen. The group’s openly stated goal, like Kaczynski’s, is the destruction of civilization and a return to preagricultural ways of life.

So far, most of the violence has happened outside of the United States. Although the FBI declined to comment on the topic, the 2017 report on domestic terrorism by the Congressional Research Service cited just a handful of minor attacks on “symbols of Western civilization” in the past ten years, a period of relative calm most credit to Operation Backfire, the FBI crackdown on radical environmental efforts in the mid-aughts. But in Latin America and Europe, terrorist groups with florid names like Conspiracy of Cells of Fire and Wild Indomitables have been bombing government buildings and assassinating technologists for almost a decade. The most ominous example is Individualidades Tendiendo a lo Salvaje, or ITS (usually translated as Individuals Tending Toward the Wild), a loose association of terrorist groups started by Mexican Kaczynski devotees who decided that his plan to take down the system was outdated because the environment was being decimated so fast and government surveillance technology had gotten so robust. Instead, ITS would return to its guru’s old modus operandi: revenge. The group set off bombs at the National Ecology Institute in Mexico, a Federal Electricity Commission office, two banks, and a university. It now claims cells across Latin America, and in January 2017, the Chilean offshoot delivered a gift-wrapped bomb to Oscar Landerretche, the chairman of the world’s largest copper mine, who suffered minor injuries. The group explained its motives in a defiant media release: “The pretentious Landerretche deserved to die for his offenses against Earth.”

In the larger world, where no respectable person would praise Kaczynski without denouncing his crimes, little Kaczynski Moments have been popping up in the most unexpected places — the Fox News website, for example, which ran a piece by Keith Ablow called “Was the Unabomber Correct?” in 2013. After summarizing some of Kaczynski’s dark predictions about the steady erosion of individual autonomy in a world where the tools and systems that create prosperity are too complex for any normal person to understand, Ablow — Fox’s “expert on psychiatry” — came to the conclusion that Kaczynski was “precisely correct in many of his ideas” and even something of a prophet. “Watching the development of Facebook heighten the narcissism of tens of millions of people, turning them into mini reality-TV versions of themselves,” he wrote. “I would bet he knows, with even more certainty, that he was onto something.”

That same year, in the leading environmentalist journal Orion, a “recovering environmentalist” named Paul Kingsnorth — who’d stunned his fellow activists in 2008 by announcing that he’d lost hope — published an essay about the disturbing experience of reading Kaczynski’s manifesto for the first time. If he ended up agreeing with Kaczynski, “I’m worried that it may change my life,” he confessed. “Not just in the ways I’ve already changed it (getting rid of my telly, not owning a credit card, avoiding smartphones and e-readers and sat-navs, growing at least some of my own food, learning practical skills, fleeing the city, etc.) but properly, deeply.”

By 2017, Kaczynski was making inroads with the conservative intelligentsia — in the journal First Things, home base for neocons like Midge Decter and theologians like Michael Novak, deputy editor Elliot Milco described his reaction to the manifesto in an article called “Searching for Ted Kaczynski”: “What I found in the text, and in letters written by Kaczynski since his incarceration, was a man with a large number of astute (even prophetic) insights into American political life and culture. Much of his thinking would be at home in the pages of First Things.” A year later, Foreign Policy published “The Next Wave of Extremism Will Be Green,” an editorial written by Jamie Bartlett, a British journalist who tracks the anti-civ movement. He estimated that a “few thousand” Americans were already prepared to commit acts of destruction. Citing examples such as the Standing Rock pipeline protests in 2017, Bartlett wrote, “The necessary conditions for the radicalization of climate activism are all in place. Some groups are already showing signs of making the transition.”

The fear of technology seems to grow every day. Tech tycoons build bug-out estates in New Zealand, smartphone executives refuse to let their kids use smartphones, data miners find ways to hide their own data. We entertain ourselves with I Am Legend, The Road, V for Vendetta, and Avatar while our kids watch Wall-E or FernGully: The Last Rainforest. An eight-part docudrama called Manhunt: The Unabomber was a hit when it premiered on the Discovery Channel in 2017 and a “super hit” when Netflix rereleased it last summer, says Elliott Halpern, the producer Netflix commissioned to make another film focusing on Kaczynski’s “ideas and legacy.” “Obviously,” Halpern says, “he predicted a lot of stuff.”

And wouldn’t you know it, Kaczynski’s papers have become one of the most popular attractions at the University of Michigan’s Labadie Collection, an archive of original documents from movements of “social unrest.” Kaczynski’s archivist, Julie Herrada, couldn’t say much about the people who visit — the archive has a policy against characterizing its clientele — but she did offer a word in their defense. “Nobody seems crazy.”

Two years ago, I started trading letters with Kaczynski. His responses are relentlessly methodical and laced with footnotes, but he seems to have a droll side, too. “Thank you for your undated letter postmarked 6/11/18, but you wrote the address so sloppily that I’m surprised the letter reached me …” “Thank you for your letter of 8/6/18, which I received on 8/16/18. It looks like a more elaborate and better developed, but otherwise typical, example of the type of brown-nosing that journalists send to a ‘mark’ to get him to cooperate.” Questions that revealed unfamiliarity with his work were poorly received. “It seems that most big-time journalists are incapable of understanding what they read and incapable of transmitting facts accurately. They are frustrated fiction-writers, not fact-oriented people.” I tried to warm him up with samples of my brilliant prose. “Dear John, Johnny, Jack, Mr. Richardson, or whatever,” he began, before informing me that my writing reminded him of something the editor of another magazine told the social critic Paul Goodman, as recounted in Goodman’s book Growing Up Absurd: “ ‘If you mean to tell me,” an editor said to me, “that Esquire tries to have articles on serious issues and treats them in such a way that nothing can come of it, who can deny it?’ ” (Kaczynski’s characteristically scrupulous footnote adds a caveat, “Quoted from memory.”) His response to a question about his political preferences was extra dry: “It’s certainly an oversimplification to say that the struggle between left … right in America today is a struggle between the neurotics and the sociopaths (left = neurotics, right = sociopaths = criminal types),” he said, “but there is nevertheless a good deal of truth in that statement.”

But the jokes came to an abrupt stop when I asked for his take on America’s descent into immobilizing partisan warfare. “The political situation is complex and could be discussed endlessly, but for now I will only say this,” he answered. “The current political turmoil provides an environment in which a revolutionary movement should be able to gain a foothold.” He returned to the point later with more enthusiasm: “Present situation looks a lot like situation (19th century) leading up to Russian Revolution, or (pre-1911) to Chinese Revolution. You have all these different factions, mostly goofy and unrealistic, and in disagreement if not in conflict with one another, but all agreeing that the situation is intolerable and that change of the most radical kind is necessary and inevitable. To this mix add one leader of genius.”

Kaczynski was Karl Marx in modern flesh, yearning for his Lenin. In my next letter, I asked if any candidates had approached him. His answer was an impatient no — obviously any revolutionary stupid enough to write to him would be too stupid to lead a revolution. “Wait, I just thought of an exception: John Jacobi. But he’s a screwball — bad judgment — unreliable — a problem rather than a help.”

The Kaczynski moment dislocates. Suddenly, everyone seems to be living in a dream world. Why are they talking about binge TV and the latest political outrage when we’re turning the goddamn atmosphere into a vast tanker of Zyklon B? Was he right? Were we all gelded and put in harnesses without even knowing it? Is this just a simulation of life, not life itself?

People have moments like that under normal conditions, of course. Sigmund Freud wrote a famous essay about them way back in 1929, Civilization and Its Discontents. A few unsettled souls will always quit that bank job and sail to Tahiti, and the stoic middle will always suck it up. But Jacobi couldn’t accept those options. Staggered by the shock of his Kaczynski Moment but intent on rising to the challenge, he began corresponding with the great man himself, hitchhiked the 644 miles from Chapel Hill to Ann Arbor to read the Kaczynski archives, tracked down his followers all around the world, and collected an impressive (and potentially incriminating) cache of material on ITS along the way. He even published essays about them in an alarmingly terror-friendly print journal named Atassa. But his biggest influence was a mysterious Spanish radical theorist known only by the pseudonym he used to translate Kaczynski’s manifesto into Spanish, Último Reducto. Recommended by Kaczynski himself, who even supplied an email address, Reducto gave Jacobi a daunting reading list and some editorial advice on his early essays, which inspired another series of TV-movie twists in Jacobi’s turbulent life. Frustrated by the limits of his knowledge, he applied to the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, to study some more, received a full scholarship and a small stipend, and buckled down for two years of intense scholarship. Then he quit and hit the road again. “I think the homeless are a better model than ecologically minded university students,” he told me. “They’re already living outside of the structures of society.”

Four years into this bizarre pilgrimage, Jacobi is something of an underground figure himself — the ubiquitous, eccentric, freakishly intellectual kid who became the Zelig of ecoextremism. Right now, he’s about to skin his first rat. Barefoot and shirtless, with an old wool blanket draped over his shoulders, long sun-streaked hair and gleaming blue eyes, he hurries down a rocky mountain trail toward a stone-age village of wattle-and-daub huts, softening his voice to finish his thought. “Ted was a good start. But Ted is not the endgame.”

He stops there. The village ahead is the home of a “primitive skills” school called Wild Roots. Blissfully untainted by modern conveniences like indoor toilets and hot showers, it’s also free of charge. It has just three rules, and only one that will get us kicked out. “I don’t want to be associated with that name,” Wild Roots’ de facto leader told us when I mentioned Kaczynski. “I don’t want my name associated with that name,” he added. “I really don’t want to be associated with that name.”

Jacobi arrives at the open-air workshop, covered by a tin roof, where the dirtiest Americans I’ve ever seen are learning how to weave cordage from bark, start friction fires, skin animals. The only surprise is the lives they led before: a computer analyst for a military-intelligence contractor, a Ph.D. candidate in engineering, a classical violinist, two schoolteachers, and a rotating cast of college students the older members call the “pre-postapocalypse generation.” Before he became the community blacksmith, the engineering student was testing batteries for ecofriendly cars. “It was a fucking hoax,” he says now. “It wasn’t going to make any difference.” At his coal-fired forge, pounding out simple tools with a hammer and anvil, he feels much more useful. “I can’t make my own axes yet, but I made most of the handles on those tools, I make all my own punches and chisels. I made an adze. I can make knives.”

Freshly killed this morning, five dead rats lie on a pine board. They’re for practice before trying to skin larger game. Jacobi bends down for a closer look, selects a rat, ties a string to its twiggy leg, and hangs it from a rafter. He picks up a razor. “You wanna leave the cartilage in the ear,” his teacher says. “Then cut just above the white line and you’ll get the eyes off.”

A few feet away, a young woman who fled an elite women’s college in Boston pounds a wooden staff into a bucket to pulverize hemlock bark to make tannin to tan the bear hide she has soaking in the stream — a mixture of mashed hemlock and brain tissue is best, she says, though eggs can substitute if you can’t get fresh brain.

Jacobi works the razor carefully. The eyes fall into the dirt.

“I’m surprised you haven’t skinned a rat before,” I say.

“Yeah, me too,” he replies.

He is, after all, the founder of The Wildernist and Hunter/Gatherer, two of the more radical web journals in the personal “rewilding” movement. The moderates at places like ReWild University talk of “rewilding your taste buds” and getting in “rockin’ fit shape.” “We don’t have to demonize our culture or attempt to hide from it,” ReWild University’s website enthuses. Jacobi has no interest in padding the walls of the cage — as he put it in an essay titled “Taking Rewilding Seriously,” “You can’t rewild an animal in a zoo.”

He’s not an idiot; he knows the zoo is pretty much everywhere at this point. He explained this in the philosophical book he wrote at 22, Repent to the Primitive: “My focus on the Hunter/Gatherer is based on a tradition in political philosophy that considers the natural state of man before moving on to an analysis of the civilized state of man. This is the tradition of Hobbes, Rousseau, Locke, Hume, Paine.” His plan is to ace his primitive skills, then test living wild for an extended time in the deepest forest he can find.

So why did it take him so long to get out of the zoo?

“I thought sabotage was more important,” he says.

But this isn’t the place to talk about that — he doesn’t want to break Wild Roots’ rules. Jacobi goes silent and works his razor down the rat’s body, pulling the skin down like a sock.

When he’s finished, he leads the way back into the woods, naming the plants: pokeberry, sourwood, rhododendron, dog hobble, tulip poplar, hemlock. The one with orange flowers is a lily that will garnish his dinner tonight. “If you want, I can get some for you,” he offers.

Then he returns to the forbidden topic. “I could never do anything like that,” he says firmly — unless he could, which is also a possibility. “I don’t have any moral qualms with violence,” he says. “I would go to jail, but for what?”

For what? The first time I talked to him, he told me he had dreams of being the leader Kaczynski wanted.

“I am being a little evasive,” he admits. His other reason for going to college, he says, was to plant the anti-civ seed in the future lawyers and scientists gathered there — “people who will defend you, people who have access to computer networks” — and also, speaking purely speculatively, who could serve as “the material for a terrorist criminal network.”

“Did you convince anybody?” I ask.

“I don’t know. I always told them not to tell me.”

“So you wanted to be the Lenin?”

“Yeah, I wanted to be Lenin.”

But let’s face it, he says, the revolution’s never going to happen. Probably. Maybe. That’s why he’s heading into the woods. “I want to come out in a few years and be like Jesus,” he jokes, “working miracles with plants.”

Isn’t he doing exactly what Lenin did during his exile in Europe, though? Honing his message, building a network, weighing tactical options, and creating a mystique. Is he practicing “security culture,” the activist term for covering your tracks? “Are you hiding the truth? Are you secretly plotting with your hard-core cadre?”

He smiles. “I wouldn’t be a very good revolutionary if I told you I was doing that.”

At the last minute, Abe Cabrera changed our rendezvous point from a restaurant in New Orleans to an alligator-filled swamp an hour away. This wasn’t a surprise. Jacobi had given me Cabrera’s email address, identifying him as the North American contact for ITS, which Cabrera immediately denied. His interest in ITS was purely academic, he insisted, an outgrowth of his studies in liberation theology. “However,” he added, “to say that I don’t have any contact with them may or may not be true.”

Now he’s leading me into the swamp, literally, talking about an ITS bomb attack on the head of the Department of Physical and Mathematical Sciences at the University of Chile in 2011. “Is that a fair target?” he asks. “For Uncle Ted, it would have been, so I guess that’s the standard.” He chuckles.

He’s short, round, bald, full of nervous energy, wild theories, and awkward tics — if “Terrorist Spokesman” doesn’t work out for him, he’s a shoo-in for “Mad Scientist in a B-Movie.” Giant ferns and carpets of moss appear and disappear as he leads the way into the swamp, where the elephantine roots of cypress trees stand in the eerie stillness of the water like dinosaurs.

He started checking out ITS after he heard some rumors about a new cell starting up in Torreón, his grandparents’ birthplace in Mexico, he says, but the group didn’t really catch his interest until it changed its name from Individuals Tending Toward the Wild to Wild Reaction. Why? Because healthy animals don’t have “tendencies” when they confront an enemy. As one Wild Reaction member put it in the inevitable postattack communiqué, another example of the purple prose poetry that has become the group’s signature: “I place the device, and it transforms me into a coyote thirsting for revenge.”

Cabrera calls this “radical animism,” a phrase that conjures the specter of nature itself rising up in revolt. Somehow that notion wove together all the dizzying twists his life had taken — the years as the child of migrant laborers in the vegetable fields of California’s Imperial Valley, his flirtation with “super-duper Marxism” at UC Berkeley, the leap of faith that put him in an “ultraconservative, ultra-Catholic” order, and the loss of faith that surprised him at the birth of his child. “Most people say, ‘I held my kid for the first time and I realized God exists.’ I held my kid the first time and I said, ‘You know what? God is bullshit.’ ” People were great in small doses but deadly in large ones, even the beautiful little girl cradled in his arms. There were no fundamental ethical values. It all came down to numbers. If that was God’s plan, the whole thing was about as spiritually “meaningful as a marshmallow,” Cabrera says.

John Jacobi is a big part of this story, he adds. They connected on Facebook after a search for examples of radical animism led him to Hunter/Gatherer. They both contributed to the journal Atassa, which was dedicated on the first page to the premise that “civilization should be fought” and that the example of Ted Kaczynski “is what that fighting looks like.” In the premier edition, Jacobi made the prudent decision to write in a detached tone. Cabrera’s essay bogs down in turgid scholarship before breaking free with a flourish of suspiciously familiar prose poetry: “Ecoextremists believe that this world is garbage. They understand progress as industrial slavery, and they fight like cornered wild animals since they know that there is no escape.”

Cabrera weaves in and out of corners like a prisoner looking for an escape route, so it’s hard to know why he chose a magazine reporter for his most incendiary confession: “Here’s the super-official version I haven’t told anybody — I am the unofficial voice-slash-theoretician of ecoextremism. I translated all 30 communiqués. I translated one last night.”

Abe Cabrera: Abracadabra.

Yes, he knows this puts him dangerously close to violating the laws against material contributions to terrorism. He read the Patriot Act. That’s why he leads a double life, even a triple life. Nobody at work knows, nobody from his past knows, even his wife doesn’t know. He certainly doesn’t want his kids to know. He doesn’t even want to tell them about climate change. Math homework, piano lessons, gymnastics, he’s “knee-deep in all that stuff.” He punches the clock. “What else am I gonna do? I love my kids,” he says. “I hope for their future, even though they have no future.”

His mood sinks, reminding me of Jacobi. Shifts in perspective seem to be part of this world. Puma hunted here before the Europeans came, Cabrera says, staring into the swamp. Bears and alligators, too, things that could kill you. The cypress used to be three times as thick. When you look around, you see how much everything has suffered.

But we’re not in this mess because of greed or nihilism; we’re in it because we love our children so much we made too many of them. And we’re just so good at dominating things, all that is left is to lash out in a “wild reaction,” Cabrera says. That’s why he sympathizes with ITS. “It’s like, ‘Be the psychopathic destruction you want to see in the world’, ” he says, tossing out one last mordant chuckle in place of a good-bye.

Kaczynski is annoyed with me. “Do not write me anything more about ITS,” he said. “You could get me in trouble that way.” He went on: “What is bad about an article like the one I expect you to write is that it may help make the anti-tech movement into another part of the spectacle (along with Trump, the ‘metoo movement,’ neo-Nazis, antifa, etc.) that keeps people entertained and therefore thoughtless.”

ITS, he says, is the very reason he cut Jacobi off. Even after Kaczynski told him the warden was dying for a reason to reduce his contacts with the outside world, the kid kept sending him news about them. He ended his letter to me with a controlled burst of fury. “A hypothesis: ITS is instigated by some country’s security services — probably Mexico. Their real task is to spread hopelessness, because where there is no hope there is no serious resistance.”

Wait … Ted Kaczynski is hopeful? The Ted Kaczynski who wants to destroy civilization? The idea seems ridiculous right up to the moment it spins around and becomes reasonable. What better evidence could you find than the unceasing stream of tactical and strategic advice that he’s sent from his prison cell for almost 20 years, after all. He’s hopeful that civilization can be taken down in time to save some of the planet. I guess I just couldn’t imagine how anyone could ever manage to rally a group of ecorevolutionaries large enough to do the job.

“If you’ve read my Anti-Tech Revolution, then you haven’t understood it,” he scolds. “All you have to do is disable some key components of the system so that the whole thing collapses.” I do remember the “small core of deeply committed people” and “Hit Where It Hurts,” but it’s still hard to fathom. “How long does it take to do that?” Kaczynski demands. “A year? A month? A week?”

On paper, Deep Green Resistance meets most of his requirements. The original core group spent five years holding conferences and private meetings to hone its message and build consensus, then publicized it effectively with its book, which speculates about tactical alternatives to stop the “planet from burning to a cinder”: “If selective disruption doesn’t work soon enough, some resisters may conclude that all-out disruption is needed” and launch “coordinated actions on a large scale” against key targets. DGR now has as many as 200,000 members, according to the group’s co-founder — a soft-spoken 30-year-old named Max Wilbert — who could shave off his Mephistophelian goatee and disappear into any crowd. Two hundred thousand may not sound like much when Beyoncé has 1 million-plus Instagram followers, but it’s not shabby in a world where lovers cry out pseudonyms during sex. And Fidel had only 19 in the jungles of Cuba, as Kaczynski likes to point out.

Jacobi says DGR was hobbled by a doctrinal war over “TERFs,” an acronym I had to look up — it’s short for “trans-exclusionary radical feminists” — so this summer they’re rallying the troops with a crash course in “resistance training” at a private retreat outside Yellowstone National Park in Montana. “This training is aimed at activists who are tired of ineffective actions,” the promotional flyer says. “Topics will include hard and soft blockades, hit-and-run tactics, police interactions, legal repercussions, operational security, terrain advantages and more.”

At the Avis counter at the Bozeman airport, my phone dings. It’s an email from the organizers of the event, saying a guy named Matt needs a ride. I find him standing by the curb. He’s in his early 30s, dressed in conventional clothes, short hair, no visible tattoos, the kind of person you’d send to check out a visitor from the media. When we get on the road and have a chance to talk, he says he’s a middle-school social-studies teacher. He’s sympathetic to the urge to escalate, but he’d prefer to destroy civilization by nonviolent means, possibly by “decoupling” from the modern world, town by town and state by state.

But if that’s true, why is he here?

“See for yourself,” he said.

We reach the camp in the late afternoon and set up our tents next to a big yurt. A mountain rises behind us, another mountain stands ahead; a narrow lake fills the canyon between them as the famous Big Sky, blushing at the advances of the night, justifies its association with the sublime. “Nature is the only place where you feel awe,” Jacobi told me after the leaves rustled at Wild Roots, and right now it feels true.

An hour later, the group gathers in the yurt outfitted with a plywood floor, sofas, and folding chairs: one student activist from UC Irvine, two Native American veterans of the Standing Rock pipeline protests, three radical lawyers, a shy working-class kid from Mississippi, a former abortion-clinic volunteer, and a few people who didn’t want to be identified or quoted in any way. The session starts with a warning about loose lips and a lecture on DGR’s “nonnegotiable guidelines” for men — hold back, listen, agree or disagree respectfully, avoid male-centered words, and follow the lead of women.

By that time, I’d already committed my first microaggression. The cook asked why I was standing in the kitchen doorway, and I answered, “Just supervising.” Her sex had nothing to do with it, I swear — I was waiting to wash my hands and, frankly, her question seemed a bit hostile. But the woman who followed me out the door to dress me down said that refusing to accept her criticism was another microaggression.

The first speaker turns the mood around. His name is Sakej Ward, and he did a tour in Afghanistan with the U.S. Joint Airborne and a few years in the Canadian military. He’s also a full-blooded member of the Wolf Clan of British Columbia and the Mi’kmaq of northern Maine with two degrees in political science, impressive muscles bulging through a T-shirt from some karate club, and one of those flat, wide Mohawks you see on outlaw bikers.

Unfortunately, he put his entire presentation off the record, so all I can tell you is that the theme was Native American warrior societies. Later he tells me the societies died out with the buffalo and the open range. They revived sporadically in the last quarter of the 20th century, but returned in earnest at events like Standing Rock. “It’s a question of ‘Are they there yet?’ We’ve been fighting this war for 500 years. But climate change is creating an atmosphere where it can happen.”

For the next two days, we get training in computer security and old activist techniques like using “lockboxes” to chain yourself to bulldozers and fences — given almost apologetically, like a class in 1950s home cooking. In another session, Ward takes us to a field and lines us up single file. Imagine you’re on a military patrol, he says, turning his back and holding his left hand out to the side, elbow at 90 degrees and palm forward. “Freeze!,” he barks.

We freeze.

“That’s the best way to conceal yourself from the enemy,” he tells us. He runs through basic Army-patrol semiotics. For “enemy,” you make a pistol with your hand and turn it thumbs-down. “Danger area” is a diagonal slash. After showing us a dozen signs, he stops. “Why am I making all the signs with my left hand?”

No one knows.

He turns around to face us with his finger pointed down the barrel of an invisible gun. “Because you always have to have a finger in control of your weapon,” he says.

The trainees are pumped afterward. “You can take out transformers with a .50 caliber,” one man says.

“But you don’t just want to do one,” says another. “You want four-man teams taking out ten transformers. That would bring the whole system to a halt.”

Kaczynski would be fairly pleased with this so far, I think. Ward is certainly a plausible contender for the Lenin role. Wilbert might be too. “We talk about ‘cascading catastrophic effects,’ ” he tells us in one of the last yurt meetings, summing up DGR’s grand strategy. “A large percent of the nation’s oil supply is processed in a facility in Louisiana, for example. If that was taken down, it would have cascading effects all over the world.”

But then the DGR women called us together for a lecture on patriarchy, which has to be destroyed at the same time as civilization. Also, men who voluntarily assume gendered aspects of female identity should never be allowed in female-sovereign spaces — and don’t call them TERFs unless you want a speech on microaggression.

Matt listens from the fringes in a hoodie and mirrored glasses, looking exactly like the famous police sketch of the Unabomber. I’m pretty sure he’s trolling them. Maybe he’s remembering the same Kaczynski quote I am: “Take measures to exclude all leftists, as well as the assorted neurotics, lazies, incompetents, charlatans, and persons deficient in self-control who are drawn to resistance movements in America today.”

At the farewell dinner, one of the more mysterious trainees finally speaks up. With long, wild hair, a floppy wilderness hat, pants tucked into waterproof boots, a wary expression, and an actual hermit’s cabin in Montana, he projects the anti-civ vibe with impressive authenticity. He was involved in some risky stuff during the Cove Mallard logging protests in Idaho in the mid-1990s, he says, but he retreated after the FBI brought him in for questioning. Lately, though, he’s been getting the feeling that things are starting to change, and now he’s sure of it. “I’ve been in a coma for 20 years,” he says. “I want to thank you guys for being here when I woke up.” One of the radical lawyers wraps up with a lyrical tribute to the leaders of Ireland’s legendary 1916 rebellion. He waxes about Thomas MacDonagh, the schoolteacher who led the Dublin brigade and whistled as he was led to the firing squad.

On the drive back to the airport, I ask Matt if he’s really a middle-school teacher. He answers with a question: What is your real interest in this thing?

I mention John Jacobi. “I know him,” he says. “We’ve traded a few emails.”

Of course he does. He’s another serious young man with gears turning behind his eyes.

“Can you imagine actually doing something like that?” I ask.

“Well,” he answers, drawing out the pause, “Thomas MacDonagh was a schoolteacher.”

The next time I talk to John Jacobi, he’s back in Chapel Hill living with a friend and feeling shaky. Things were getting strange at Wild Roots, he says — nobody could cooperate, there were personal conflicts. And, well, there was an incident with molly. It’s been a hard four years. First he lost Jesus and anarchy. Then Kaczynski and Último Reducto dumped him, which was really painful, though he understood why. “I’ve been unreliable,” he says woefully. To make matters worse, an ITS member called Los Hijos del Mencho denounced him by name online: The trouble with Jacobi was his “reluctance to support indiscriminate attacks” because of his sentimental attachment to humanity.

Jacobi is considering the possibility that his troubled past may have affected his judgment. He still believes in the revolution, he says, but he’s not sure what he’d do if somebody gave him a magic bottle of Civ-Away. He’d probably use it. Or maybe not.

I check in a couple of weeks later. He’s working in a fish store and thinking of going back to school. Maybe he can get a job in forest conservation. He’d like to have a kid someday.

He brings up Paul Kingsnorth, the “recovering environmentalist” who got rattled by Kaczynski’s manifesto in 2012. Kingsnorth’s answer to our global existential crisis was mourning, reflection, and the search for “the hope beyond hope.” The group he co-founded to help people with that task, a mixture of therapy group and think tank called Dark Mountain, now has more than 50 chapters worldwide. “I’m coming to terms with the fact that it might very well be true that there’s not much you can do,” Jacobi says, “but I’m having a real hard time just letting go with a hopeless sigh.”

In his Kaczynski essay, Kingsnorth, who has since moved to Ireland to homeschool his kids and write novels, put his finger on the problem. It was the hidden side effect of the Kaczynski Moment: paralysis. “I am still embedded, at least partly because I can’t work out where to jump, or what to land on, or whether you can ever get away by jumping, or simply because I’m frightened to close my eyes and walk over the edge.” To the people who end up in that suspended state now and then, lying in bed at four in the morning imagining the worst, here’s Kingsnorth’s advice: “You can’t think about it every day. I don’t. You’ll go mad!”

It’s winter now and Jacobi’s back on the road, sleeping in bushes and scavenging for food, looking for his place to land. Sometimes I wonder if he makes these journeys into the forest because of the way his mother ended her life — maybe he’s searching for the wild beasts and ministering angels she heard when he fell to his knees and spoke the language of God. Psychologists call that magical thinking. Medication and counseling are more effective treatments for trauma, they say. But maybe the dream of magic is the magic, the dream that makes the dream come true, and maybe grief is a gift too, a check on our human arrogance. Doesn’t every crisis summon the healers it needs?

In the poems Jacobi wrote after his mother hanged herself, she turned into a tree and sprouted leaves.

READ MORE Donald Trump. (photo: Erin Schaff/NYT)

Donald Trump. (photo: Erin Schaff/NYT)

Cannon's earlier rulings suggest she "bends over backwards" to appease Trump, ex-federal judge says

Legal experts sounded the alarm on Friday after Judge Aileen Cannon, a Trump appointee accused of favoritism after she blocked the FBI from using documents seized from Mar-a-Lago in its investigation before an appeals court overturned her order, was assigned to the Mar-a-Lago case. Trump's team, meanwhile, sees it as an opportunity to try a "ploy" to squash damning notes provided by his own lawyer, Evan Corcoran, in the case against him, according to The Daily Beast.

A D.C. judge ordered Corcoran to turn over his notes to prosecutors and provide testimony after agreeing with the DOJ that Trump may have used his services in furtherance of a crime. Corcoran's notes revealed that Trump mused openly about lying to investigators about the hundreds of classified documents stashed at Mar-a-Lago and appeared to suggest that his lawyer should destroy or hide evidence.

While it's too late for Trump's team to try to get the notes back from the DOJ, sources told the Daily Beast that his lawyers plan to ask Cannon to dismiss the charge that Trump personally plotted ways to obstruct the government's investigation, arguing that the notes should have been covered by attorney-client privilege.

The plan shows how the selection of Cannon "could play out favorably" for Trump, and a source told The Daily Beast that if it works, Corcoran could be "totally in the clear," though it would not insulate Trump from other charges.

Without a court intervention, Corcoran figures to be the "No. 1 government witness to prove Trump committed a coverup," wrote The Daily Beast's Jose Pagliery.

Trump last spring asked Corcoran and attorney Jennifer Little how he could avoid responding to a grand jury subpoena for the documents he failed to return to the National Archives, according to the indictment.

"Well, what if we, what happens if we just don't respond at all or don't play ball with them?" Trump mused. "Wouldn't it be better if we just told them we don't have anything here?"

"Well, look, isn't it better if there are no documents?" Trump asked.

Trump also repeatedly appeared to suggest that Corcoran should take the fall for him, citing an attorney for Hillary Clinton who he said deleted "the 30,000 emails" so that "she didn't get in any trouble," according to the indictment.

The extensive notes have alarmed Trump's team.

"They were way too detailed," a source familiar with the team's internal discussions told The Daily Beast.

Former Trump attorney Tim Parlatore, who recently resigned from the team, told the outlet that the allegations in the indictment are damning.

"It's really bad," Parlatore said. "That whole discussion about his interaction with Walt [Nauta] to move the boxes is bad. That's what people go to jail for. It's bad—if they have the evidence to back it all up." (WALT NAUTA)

But Parlatore added that Cannon is well-positioned to swing the lawyer notes aspect in Trump's favor.

"If another judge looks at it and says this is normal attorney client-communications, they can strike these charges out of the indictment and Corcoran's no longer a witness. He can try the case himself," he said.

Trump's lawyers previously "specifically sought out" Cannon in 2022 after they filed a lawsuit against Hillary Clinton but the "gambit failed" when a different judge, who was appointed by Bill Clinton, got the case and threw out the frivolous suit, The Daily Beast reported. Trump's lawyers "struck gold" months later when they landed Cannon in their challenge of the FBI search of Mar-a-Lago. Cannon appointed a short-lived special master and blocked the FBI from reviewing the most sensitive documents seized from Mar-a-Lago before an Atlanta appeals court overruled her.

Some legal experts have called on Cannon to recuse herself given her role earlier in the probe.

"She's demonstrated favoritism to Trump, and her past decisions in the investigation reversed by 11th Circuit were so erroneous that bias is clear," tweeted CNN legal analyst Norm Eisen, who served as Democratic counsel during Trump's first impeachment.

"Judge Cannon, who abused her discretion previously in favor of Trump, should recuse herself from the Trump case. If she doesn't, DOJ should file a motion to recuse. This issue is too important to ignore and hope for the best," wrote MSNBC legal analyst Glenn Kirschner.

Former Watergate prosecutor Jill Wine-Banks predicted it was "not likely" that special counsel Jack Smith would move to remove Cannon.

"Good news though: Trump cannot waive jury unless prosecutor agrees, so Cannon won't be deciding guilt, but she can delay the case and make unfair and legally incorrect rulings on admissibility of evidence," she tweeted.

Carol Lam, a former federal judge and U.S. attorney, told MSNBC that Cannon's earlier rulings suggests "she bends over backwards a little bit more for the former president" but how that would play out in a trial "remains to be seen."

If Cannon steps aside, another Trump appointee could get the case.

"This isn't about who appointed the judge," former U.S. Attorney Joyce Vance told the network. "This is about how the public will view the case. And because of her decisions in the earlier matter, where the 11th Circuit didn't just reverse her but said she was out of bounds, that she lacked jurisdiction, they moved extraordinarily quickly to prevent her from allowing Trump to engage in delay."

Vance added that Cannon could influence numerous factors in the case, like rulings on pre-trial motions and the admissibility of evidence.

"The public won't have confidence whether she acquits or convicts," Vance warned.

But MSNBC legal analyst Lisa Rubin ultimately doesn't expect a fight over Cannon's assignment.

"Cannon got the case through random assignment—and absent a voluntary recusal (which I don't expect) or a motion to recuse by DOJ," Rubin wrote, "which would consume time DOJ likely doesn't want to waste, she'll keep it."

READ MORE  Donald Trump. (photo: Reuters)

Donald Trump. (photo: Reuters)

The talking heads on Kremlin TV are brainstorming ways to get Trump back into power after the shock of the indictment.

Troubled by the magnitude of the criminal jeopardy their favored candidate is facing, the Kremlin’s mouthpieces on state media’s airwaves are openly brainstorming how to help Trump by undermining President Joe Biden—reflecting the efforts that are likely taking place behind the scenes. After all, Trump represents Moscow’s best hope that the U.S. will eventually stop supporting Ukraine, which would in turn allow Russia to swallow it whole.

When it was first revealed that Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate was searched by the FBI and contained hundreds of classified documents, Russian state TV host Evgeny Popov mockingly noted: “Turns out that the investigation against Trump has to do with the disappearance of secret documents from the White House, related to the development of new nuclear weapons by the United States... Obviously, if there were any important documents, they’ve been studying them in Moscow for a while. What’s the point of searching?”

Now that the search has resulted in a multitude of charges, Popov and his fellow propagandists are not nearly as giddy but still hold out the hope that the Republicans and their mouthpieces—like Russia’s beloved Tucker Carlson—will manage to harm Biden and undermine U.S. aid to Ukraine.

Appearing on Vladimir Solovyov’s morning broadcast of Full Contact, "Americanologist" Dmitry Drobnitsky mockingly predicted that in light of the criminal charges that threaten the main contenders of the presidential race, the final battle might be between Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Nikki Haley. He pointed out that RFK Jr. surprised everyone with higher-than-anticipated popularity ratings but noted that he is unlikely to prevail. Nonetheless, Drobnitsky said, Kennedy’s participation in the elections will enable him to inject his pro-Russian talking points about Ukraine into the mainstream—a beneficial side effect for Moscow.

During Thursday’s broadcast of The Evening With Vladimir Solovyov, experts proposed being more proactive, weighing various ways to boost their favorite candidate and sink his opponent. Dmitry Evstafiev, Professor at the School of Integrated Communications, suggested: “In the West, we should be supporting crooks, scumbags, and idiots—then we will succeed! We should support them and convince them that they are geniuses.”

Drobnitsky surmised: “It’s possible that none of the leading presidential candidates will make it to the 2024 elections as free men. There is a number of pending and potential criminal cases against all of them!” He suggested: “In addition to demonstrating our successes, both in the economic field and on the frontlines of the special military operation, it’s time for us to take advantage of this. The new cornerstone of our foreign policy should be to constantly demonstrate the toxicity of the American world, the Pax Americana that previously suited everyone.” He later added: “Let all the flowers bloom, as long as our adversaries are allergic to them... We should do whatever we can to shove them out of our Eurasia.”

The grand plan of forcing the U.S. to focus predominately on its internal issues is in line with Trump’s long-standing pledge to greatly limit America’s global involvement, concentrating mainly on trade and financial dealings.

Drobnitsky, a self-described fan of former President Trump, proposed: “Let’s release a story where we’ll write that Biden was personally getting $10 million for every day of the war in Ukraine. Who can prove it isn’t so? There are so many criminal cases out there!”

READ MORE  Greta Thunberg. (photo: Ronald Patrick/Grist)

Greta Thunberg. (photo: Ronald Patrick/Grist)

The young activist graduated high school but says "the fight has only just begun."

“The fight has only just begun,” Thunberg wrote in an announcement on Twitter on Friday.

Thunberg began skipping school in 2018 to sit outside the Swedish Parliament building as a form of climate protest. She quickly attracted attention from the press and solidarity from other students similarly frustrated by their governments’ lack of action on climate change. Within a year, millions of young people around the world were skipping school on Friday to take part in protests affiliated with Thunberg’s “Fridays for Future” movement.

Building on this momentum, Thunberg took a year off from school to pursue climate activism. In August 2019, she sailed for two weeks on a zero-emissions yacht across the Atlantic to speak at the U.N. Climate Action Summit in New York City. There, she blasted world leaders for failing to address a global crisis that will irreparably harm the lives of young people and future generations.

“I shouldn’t be up here. I should be back in school on the other side of the ocean,” Thunberg told policymakers. “You are failing us. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. The eyes of all future generations are upon you.”

Three days before the summit, millions of young people and other activists in more than 160 countries took to the streets in a global climate strike led by the Fridays for Future movement that was likely the largest coordinated climate protest in world history. A few months later, Thunberg spoke at the U.N. COP25 climate summit in Spain. That year, she was named Time Magazine’s Person of the Year and nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.

Fridays for Future joined a rising tide of youth-led climate activism in the late 2010s, along with groups like the Sunrise Movement and Zero Hour. Though the arrival of COVID-19 forced protests to move online in 2020, Fridays for Future school strikes are still alive and well. The group is currently organizing a global climate strike in September.

Thunberg remains active in climate activism. In January this year, she was detained by police in Germany at a protest against the expansion of a coal mine attended by tens of thousands of people. In March, Thunberg joined Indigenous Sámi youth to protest an illegal wind farm in Norway. She regularly makes headlines for taking positions on prominent issues — for example, arguing against Germany’s use of coal in its phaseout of nuclear power and decrying Russia’s apparent bombing of a dam in Ukraine.

But some advocates have noted that the media’s spotlight on Thunberg often comes at the exclusion of young climate activists from the Global South. In a particularly damning example, the Associated Press cropped Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate out of a photo of climate activists including Thunberg in 2020.

“Frustratingly, these other activists are often referred to in the media as the ‘Greta Thunberg’ of their country, or are said to be following in her footsteps, even in cases where they began their public activism long before she started hers,” writer Chika Unigwe observed in The Guardian. Over the years, Thunberg has asked reporters to focus on climate activists from other countries.

The end of school strikes is one of a few recent shifts in Thunberg’s activism. She chose to not attend either COP26 or COP27, the last two major U.N. climate conferences in Scotland and Egypt, respectively, saying, “the COPs are not really working, unless of course we use them as an opportunity to mobilize.”

“Much has changed since we started, and yet we have much further to go,” Thunberg wrote on Twitter on Friday. “We are still moving in the wrong direction, where those in power are allowed to sacrifice marginalized and affected people and the planet in the name of greed, profit and economic growth.”

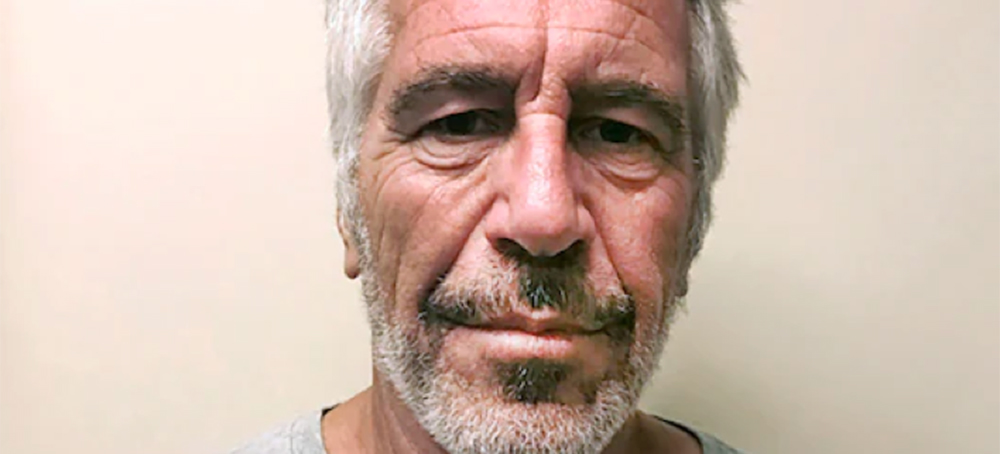

READ MORE  This March 28, 2017, photo provided by the New York State Sex Offender Registry shows Jeffrey Epstein. JPMorgan Chase announced a settlement Monday with the financier's victims, whose lawsuit had accused the bank of being the financial conduit that Epstein used to pay off his victims for years. (photo: AP)

This March 28, 2017, photo provided by the New York State Sex Offender Registry shows Jeffrey Epstein. JPMorgan Chase announced a settlement Monday with the financier's victims, whose lawsuit had accused the bank of being the financial conduit that Epstein used to pay off his victims for years. (photo: AP)

JPMorgan Reaches Settlement With Jeffrey Epstein’s Victims

Aaron Gregg, The Washington Post

Gregg writes: "The tentative deal would resolve a lawsuit filed on behalf of sexual abuse victims of the disgraced financier and claims the bank giant ignored warnings about him."

The tentative deal would resolve a lawsuit filed on behalf of sexual abuse victims of the disgraced financier and claims the bank giant ignored warnings about him.

The tentative agreement would resolve allegations made in a federal lawsuit filed last year in Manhattan. In Jane Doe 1 v. JPMorgan Chase Bank, victims accused the banking giant of enabling the sex trafficking operation by allowing for massive withdrawals of cash over a 15-year period, including after Epstein’s sex crimes were widely known. A different case, brought by the U.S. Virgin Islands, remains unresolved.

David Boies, an attorney representing the victims, confirmed the financial terms on Monday. Deutsche Bank, which handled Epstein’s accounts for a shorter period after he was dropped by JPMorgan, settled a class-action suit with similar allegations for $75 million in May.

“The parties believe this settlement is in the best interests of all parties, especially the survivors who were the victims of Epstein’s terrible abuse,” reads a statement emailed by JPMorgan spokeswoman Patricia Wexler.

The settlement comes after several of JPMorgan’s highest-ranking bankers were deposed, including chief executive Jamie Dimon and wealth management CEO Mary Erdoes. Jes Staley, a former JPMorgan executive who the bank said had advocated internally on Epstein’s behalf, also faced questioning.

The bank has denied wrongdoing and said any association with Epstein was a mistake. It has also sued Staley, accusing him of acting on his own to advance Epstein’s interests.

The lawsuit zeroed in on the extent to which those who knew or worked with Epstein were aware of his crimes, enabled them or looked the other way. It alleged the bank repeatedly ignored warnings that Epstein had been abusing teenage girls while profiting from business he brought to the bank. Epstein killed himself in August 2019 in a Manhattan jail cell, a month after his arrest, according to the New York medical examiner.

The first lawsuit was brought by several of Epstein’s victims, and the second by officials of the U.S. Virgin Islands, where Epstein owned a private residence and mansion. Attorneys for the prosecution claim the bank “knowingly facilitated, sustained, and concealed” Epstein’s long history of abuse and child sex trafficking. Epstein held accounts at JPMorgan for 15 years, starting in 1998.

“We all now understand that Epstein’s behavior was monstrous, and we believe this settlement is in the best interest of all parties, especially the survivors, who suffered unimaginable abuse at the hands of this man,” Wexler said in an email. “We would never have continued to do business with him if we believed he was using our bank in any way to help commit heinous crimes.”

David Boies, an attorney representing the victims, said the settlements represent accountability for those who enabled Epstein.

“Taken together or individually, the historic recoveries from the banks who provided financial services to Jeffrey Epstein, speak for themselves,” Boies said in an email. “It has taken a long time, too long, but today is a great day for Jeffrey Epstein survivors, and a great day for justice.”

Depositions showed that top JPMorgan executives were informed as early as 2006 that the bank had flagged suspicious activity on his accounts. But it wasn’t until 2013 ― years after Epstein’s status as a sex offender was widely publicized and discussed internally at the bank ― that Erdoes fired him as a client.

Several of the bank’s top executives blamed one another for allowing Epstein to remain a client. Dimon, in a deposition last month, said the decision to fire Epstein fell to the bank’s general counsel. But the general counsel said in his own deposition that Erdoes and Staley were responsible for that decision. Erdoes said Staley had advocated on Epstein’s behalf, and Staley accused his former colleagues of trying to shift blame onto him.

The settlement still must be approved by Judge Jed Rakoff in U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Rakoff is also presiding over the case brought by the U.S. Virgin Islands.

A spokesperson for the U.S. Virgin Islands attorney general said that office will “continue to proceed with its enforcement action to ensure full accountability for JPMorgan’s violations of the law and prevent the bank from assisting and profiting from human trafficking in the future.”

READ MORE  An Iranian woman leaves a pharmacy next to shuttered shops in Tehran on Aug. 16, 2021. (photo: Atta Kenare/AFP)

An Iranian woman leaves a pharmacy next to shuttered shops in Tehran on Aug. 16, 2021. (photo: Atta Kenare/AFP)

Joe Biden kept Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” sanctions — discouraging even legal, humanitarian trade.

In the earliest years of his life, Naroi was taking a specialized drug known as Desferal, which is manufactured by the Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis. Starting in 2018, however, around the time that President Donald Trump launched a “maximum pressure” campaign of economic sanctions against Iran, supplies of the iron-chelating drug in Iran — along with other medicines used to treat critical diseases — started to become difficult or impossible to access inside Iran, according to local NGOs supporting patients with the disease. By the summer of 2022, his organs failing due to complications from the disease, including damage to his organs from excess iron in his blood, Naroi passed away in a hospital, surrounded by his family.

According to documents obtained by The Intercept, multinational companies providing drugs for thalassemia and other conditions, as well as banks acting as intermediaries for attempted purchases, said U.S. foreign policy was ultimately causing the problems delivering drugs to Iranians. Namely, American sanctions against Iran have made the transactions so difficult that supplies of the medicines are dwindling.

The U.S. government is now facing a lawsuit from the Iran Thalassemia Society — an Iran-based NGO supporting victims of the disease — on behalf of Iranians with thalassemia and another inherited disease, epidermolysis bullosa, claiming that thousands of Iranian patients have been killed or injured after foreign companies producing specialized medicines and equipment for these diseases and others began cutting off or reducing their business with Iran as a result of sanctions. While the U.S. has given assurances that humanitarian trade with Iran will be exempted from sanctions, the lawsuit, which is currently pending appeal after being dismissed, alleges that the large-scale sanctioning of Iran’s banking sector has created a situation in which foreign companies are either unwilling or unable to do any trade with Iran at all.

“The American government has said that they will consider some exceptions for humanitarian aid, but in practice we have seen that there are no exceptions,” said Mohammed Faraji, staff attorney at the Iran Thalassemia Society. “We have had communications with countries that export medicines and medical equipment who have clearly told us that we cannot import medicaments to Iran because of sanctions. Banks won’t work with us, and health care companies won’t work with us. They are afraid of secondary sanctions and tell us that directly.”

Documents obtained by The Intercept bear out the picture of some companies balking at humanitarian trade with Iran because of the risk of being caught up in sanctions enforcement or because sanctions have closed off legal pathways for transacting with Iran. The communications reviewed, between European health care companies, foreign banks, and their Iranian counterparties, began in 2018. At times, the messages relayed are explicit: The companies won’t engage in trade with Iran — even to provide lifesaving medicines — due to the sanctions.

The intensity of foreign companies and banks aversion to dealing with Iranians reflects a victory of sorts for sanctions advocates, including hawkish pro-Israel advocacy groups and think tanks like United Against Nuclear Iran and the Foundation for Defense of Democracies. Thanks to their efforts, Iran today is one of the most sanctioned and isolated countries on Earth. While its government has held on to power and continues to remain aggressive and defiant despite the international pressure, life for ordinary Iranians has become materially worse under the sanctions regime, especially patients suffering from rare diseases.

The letters between banks, drug companies, and their Iranian interlocutors show in detail how the “maximum pressure” sanctions on Iranian financial institutions have blocked even mundane transactions for medical equipment required to treat a range of conditions.

A letter in September 2018 from a Danish manufacturer of urology products, Coloplast, informed its Iranian distributor that “despite the fact that Coloplast products are not excluded by US and/or international export control sanctions, we now face a situation, where the international banks have stopped for financial transactions with Iran. Under current conditions it is not possible to receive money for products sold in Iran.” (Coloplast did not respond to a request for comment.)

Mölnlycke, a Swedish provider of specialized bandages needed to treat patients with epidermolysis bullosa, sent a letter that same year to the head of an Iranian NGO supporting patients with the disease, EBHome, commending the organization for its work helping patients with the condition. Despite the approbation, the company said it would not be sending any more bandages to treat Iranian epidermolysis bullosa sufferers: “Due to the U.S. economic sanctions in force Mölnlycke Healthcare have decided not to conduct any business in relation to Iran for the time being.” A complaint from an Iranian NGO was filed against the company in Sweden in 2021 over the humanitarian impact of its cessation of business in Iran, but the complaint was rejected. (Mölnlycke did not respond to a request for comment.)

The denial of these specialized bandages has been particularly dire for Iranian patients. Epidermolysis bullosa is a disease that causes painful blisters and sores to appear on patients’ bodies. Many people with the condition are children whose skin is particularly tender and who require specialized wound dressings to avoid tearing the skin off when bandages are changed. An Iranian specialist on the disease submitted a testimony as part of the pending lawsuit describing the cases of six young Iranian patients who suffered excessive bleeding, infection, and “excruciating, severe pain” as a result of losing access to the specialized bandages produced by Mölnlycke.

The sanctioning of these supplies has at times led to desperate workarounds by foreign governments. In 2020, the German government and UNICEF cooperated to purchase and deliver a shipment of specialized bandages to Iran. Iranian doctors have also been forced to rely on locally produced approximations of specialized foreign medicines, many of which are of poorer quality and have resulted in life-altering complications and even deaths of patients.

Thalassemia sufferers, in particular, have been forced to use a product known as “Desfonac,” a local equivalent which is less effective at treating the disease and carries debilitating side effects not found in the original product. The Intercept obtained communications made in 2018 by local country representatives for Novartis, the company that manufactures Desferal, telling their Iranian interlocutors the drug company experiencing difficulty conducting transactions as a result of banking sanctions. These transaction problems, local organizations working on the disease say, were the beginning of the end of their own steady access to thalassemia drugs, which must be regularly administered to patients with the disease to be effective.

“We have been fighting for years to control this disease inside Iran, and it is achievable, but the simple reality is that if patients do not get the iron-regulating drugs they need to treat it, they will die,” said Younus Arab, head of the Iran Thalassemia Society. “We have documented at least 650 people who have died since 2018 when we stopped being able to import medicine and over 10,000 who have had serious complications.”

Unlike other companies, and despite difficulties in receiving payments, Novartis did not cut off ties with Iran in response to U.S. sanctions. A spokesperson for Novartis told The Intercept that the company is willing to send medical supplies to Iran and has done so since the imposition of the “maximum pressure” sanctions, including through the use of a humanitarian trade channel created by the Swiss government in 2020.

The problem created by sanctions, according to the company, is less an unwillingness to do business with Iran over legal fears than an inability of Iranian officials to access their own foreign currency reserves to make payments. The sanctions, while not eliminating Iran’s foreign reserves, have frozen Iran’s access to them, sending the country’s accessible reserves from $122.5 billion down to a mere $4 billion between 2018 and 2020, according to International Monetary Fund figures. The collapse of accessible reserves has made it impossible for the Iranian government to carry out basic economic functions like stabilizing its currency or engaging in foreign trade, even with willing parties.

“Since the imposition of certain sanctions in 2018, the most significant challenge observed by many pharmaceutical companies has been a shortfall of foreign exchange made available by the Iranian government for the import of humanitarian goods, such as medicines,” said Michael Meo, the Novartis spokesperson. “With respect to thalassemia medicines specifically, Novartis has supplied these medicines continuously since 2019. We have been — and remain — ready to satisfy orders for these medicines.”

“However,” Meo’s statement continued, “for our medicines to reach thalassemia patients in Iran, Novartis relies on the action and collaboration of the Iran Ministry of Health and Food and Drug Authority in allocating sufficient foreign currency resources to import these medicines through regular commercial channels.” (The Iranian Ministry of Health and Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not reply to requests for comment.)

For Arab, whether sanctions are creating difficulties importing medicines due to companies’ reticence or a lack of foreign currency reserves, the results are the same: Patients under the care of his organization are dying.

“We don’t want money,” he said, “what we need is medicine for these patients.”

The Trump-era economic sanctions were considered a crowning achievement of the “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran. Some of the economic sanctions against Iran targeted specific individuals and institutions involved in human rights abuses, but many others went after entire sectors of the Iranian economy, including its financial sector.

The blanket sanctions on Iranian banks essentially severed the country from trade with the rest of the world by cutting its financial arteries, including access to Iran’s own reserves held in foreign banks. The U.S. government has also imposed so-called secondary sanctions on Iran, meaning that any foreign entity that still dares to engage in trade with Iranian banks or companies puts itself at risk of being sanctioned and being cut off from doing business in the U.S. — a risk that few businesses are willing to take.

Though the U.S. government repeatedly insisted that humanitarian trade with Iran would not be affected by its “maximum pressure” campaign, economic sanctions experts said the claim is misleading. Assurances that ordinary Iranians will still be able to purchase food and medicine are meaningless, they say, when the sanctions in place are so broad that banks and foreign countries view any dealings at all with the country as a looming violation.

“The banking issue is the real crux of the problem. There is a general blocking authority on all of Iran’s financial institutions, some on which have been designated for terrorism-related reasons, some for WMD reasons, and some for human rights reasons,” said Tyler Cullis, an attorney at Ferrari … Associates, a D.C.-based law firm specializing in economic sanctions. “The Trump administration then came and imposed sanctions on Iran’s entire financial sector, and that has targeted any remaining Iranian institutions that were not covered by those measures.”

Although President Joe Biden campaigned in part on restoring the Obama-era nuclear deal, his administration effectively maintained the maximum pressure policy. The banking sanctions that made Iranian business anathema to foreign financial institutions remain in place, making the prospect of doing any trade with Iran too legally and financially risky to be worth it for any foreign company. Those risks are augmented by hawkish activist groups like United Against Nuclear Iran, which maintains public lists of companies accused of engaging in trade with Iran. The blacklists — on which UANI has in the past included companies engaged in legal trade, including for medicines, with Iran — create a potential for reputational risk that makes doing business with Iran an even more unsavory prospect.

“At the end of the Obama administration, we had ideas in front of the administration calling for a direct financial channel between the U.S. and Iran that would be able to facilitate licensed and exempt trade between the two countries. To be frank, the Obama administration rejected creating such a channel on multiple occasions,” said Cullis. “The U.S. has now hit a dead end where they have used up all their levers of pressure other than military force.”

He went on, “I sympathize with folks in Iran, as there are a lot of people there who are nonpolitical and simply trying to find solutions. But it’s really hard to find a solution when U.S. government itself is not interested in one.”

While U.S. sanctions succeeded at wrecking Iran’s middle class and preventing Iranians from accessing necessities like food and medicine, they failed to achieve the aims of Washington: forcing Iran to change its foreign policy or renegotiate the 2015 Iran nuclear deal on less favorable terms. Instead, the Iranian government has survived waves of popular anger by doubling down on repression — including through executions and imprisonment of political dissenters — against an increasingly impoverished population.

Despite growing misery in the country, the Islamic Republic of Iran seems to be as firmly in charge as ever. The hardening narrative echoes the story of U.S. economic sanctions on countries like Iraq, Cuba, and Venezuela that succeeded in harming civilians but never resulted in regime change.

“The original idea of such sanctions is that they will cause people to rise up and overthrow their government, but there is not much evidence of that while there is a lot of evidence that they harm ordinary people,” said Amir Handjani, a nonresident senior fellow at the Quincy Institute and a security fellow with the Truman National Security Project. “When you consider regular Iranians living under sanctions with rare diseases, who need specialized drugs that can only be imported from the West, they are facing a very dark future.”

The lawsuit currently filed in U.S. federal court in Oregon on behalf of Iranians with thalassemia calls on the U.S. government and the Office of Foreign Assets Control, or OFAC, which administers sanctions and trade licenses, to “permit the reintroduction of life-saving medicines and medical devices into Iran through normal business channels.”

The suit was recently dismissed by the court on grounds of proving standing by the plaintiffs; an appeal of the ruling was filed in May. Lawyers working on the case say that they will continue pressing the matter in U.S. courts to compel the government to create a solution that will allow critical medicines to reach patients inside Iran. Neither the Office of Foreign Assets Control nor the Biden White House responded to requests for comment.

“On a visceral level, people are suffering and dying. We’re talking about little children who need medical dressings and didn’t get them,” said Thomas Nelson, the attorney for the plaintiffs in the case. “No one is willing to stand up to the impunity and bullying of the U.S. government on this subject, and particularly OFAC. It ought to be brought to the public’s attention that these types of things are happening.”

READ MORE  The Weisweiler coal-fired power plant in Weisweiler, Germany on Oct. 30, 2017. The plant is one of the highest emitters of pollutants and greenhouse gases in Europe. (photo: Bernd Lauter/EcoWatch)

The Weisweiler coal-fired power plant in Weisweiler, Germany on Oct. 30, 2017. The plant is one of the highest emitters of pollutants and greenhouse gases in Europe. (photo: Bernd Lauter/EcoWatch)

Earth’s carbon budget — the amount of carbon dioxide that can be emitted to have a greater than 50 percent likelihood of keeping global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius — is quickly running out, the study warned.

“Evidence-based decision-making needs to be informed by up-to-date and timely information on key indicators of the state of the climate system and of the human influence on the global climate system. However, successive IPCC reports are published at intervals of 5–10 years, creating potential for an information gap between report cycles,” the authors of the study wrote.