Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

“You don’t know me ——” Dr. King said.

“Oh, I know you,” Mr. Belafonte replied, as he recounted later in his memoir. “Everybody knows you.”

Dr. King seemed apprehensive, as Mr. Belafonte told me in a 2017 interview, because “he didn’t know where he was headed” and “his mission was not that clear.”

Mr. Belafonte’s mission was not that clear either, not in the spring of 1956. Around that time, he released a new album, “Calypso,” which would sell more than a million copies and propel his Hollywood acting career.

But the call between the two men changed the course of both their lives. And it changed the way that celebrities would think about using, and imperiling, their stardom to advance a social cause.

Just months earlier, Rosa Parks had refused to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Ala., sparking a citywide boycott and thrusting Dr. King into a position of leadership that neither he nor anyone else could have imagined. Now Mr. Belafonte was cast into a new role, too, one that caused him to suppress his career ambitions as he joined Dr. King in pursuit of loftier goals.

Dr. King sought to build a support system in those early days and sensed “that I was one of the forces in that historical moment that was willing,” as Mr. Belafonte later told me, “to commit to that cause.”

But Mr. Belafonte might not have committed so fully if not for the almost instant bond the men forged. Even in that first phone call, Mr. Belafonte said, he was struck by Dr. King’s attentiveness. Dr. King listened more than he spoke. He asked questions. He keyed in on Mr. Belafonte’s interest in labor unions, wondering how unions might support this growing movement, which, it should be remembered, had not yet transcended Montgomery.

“In the very beginning, Dr. King was not quite as vocal as he became,” Mr. Belafonte said. “He was very much a listener. He was in a turf with which he was not deeply familiar.” Though many people received Dr. King warmly, Mr. Belafonte said, “he just did not know where he fit. His task was to gather around him people who could help reveal for him what his course would be.”

Mr. Belafonte would prove to be one of his most important guides.

Even in the earliest days of the Montgomery bus boycott, Dr. King observed that the northern news media would play a major role in shaping national opinion and driving political change. Reporters couldn’t get enough of the Baptist preacher with an advanced degree in theology. Dr. King captivated television and radio audiences. Even among Baptist preachers, Dr. King’s spellbinding oratory and charisma were rare.

But they were not so rare among Hollywood stars, as both he and Mr. Belafonte recognized.

Mr. Belafonte, working in connection with Dr. King, became the key strategist of a group of celebrity activists that included Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Sammy Davis Jr., Dick Gregory and Sidney Poitier. These and other celebrities risked their careers by joining the fight for racial justice and helped redefine what we expect of celebrities today.

Mr. Belafonte passed up opportunities to make films in favor of his work as an activist. Even after he became the first Black person to win an Emmy in 1960, further deals to do more television dissolved when a sponsor, he has said, balked at a show potentially featuring Black and white performers in collaboration.

But what struck me most strongly as I listened to Mr. Belafonte, over the course of an afternoon in his apartment in Manhattan, was not his bravery or his commitment to the cause. I was struck more by his personal commitment to Dr. King.

Over the past six years, I’ve interviewed dozens of people who knew Dr. King, but few of them showed the kind of care for Dr. King’s well-being that Mr. Belafonte did.

When Dr. King visited New York, as he did many times, he stayed at Mr. Belafonte’s home. Late at night, sometimes, the men would sit alone in Mr. Belafonte’s den and listen to music. Dr. King would take off his shoes and socks and sing along to the music of Lead Belly, Odetta and Peter, Paul and Mary.

Once, Mr. Belafonte said, he noticed that his friend had developed a kind of nervous tic, a frequent hiccup so soft one had to be standing beside him to hear it. When the hiccup suddenly vanished, Mr. Belafonte asked how he had cured it.

“I made peace,” Dr. King told him.

“With what?” Mr. Belafonte asked.

“With death,” he said.

Mr. Belafonte remained modest about his role in Dr. King’s life. “I don’t want to anoint myself,” he said.

He didn’t have to.

It was Mr. Belafonte who tried to relieve some of the strain in Dr. King’s marriage by hiring housekeeping help for his family. It was Mr. Belafonte who put away money for the education of the King children. It was Mr. Belafonte who purchased a life insurance policy for his friend. And it was Mr. Belafonte, time and again, who raised emergency funds for Dr. King’s movement, especially when money was needed to post bond for jailed protesters.

His activism didn’t end with Dr. King’s death. Dr. King was two years younger than Mr. Belafonte. When we pause to reflect on what Dr. King might have done with the gift of a long life, Mr. Belafonte offers us a splendid vision.

With his connection to Dr. King, Mr. Belafonte both exploited his newfound fame and, when necessary, subsumed it. He showed how to use a personal spotlight to bring attention to a cause — and also how to shift that spotlight to the person best at delivering the message.

For the rest of his life, Mr. Belafonte continued refining that blueprint for celebrity activism. He never tempered his radicalism. He never quit the fight. Like Dr. King, he never stopped speaking truth to power.

During our conversation, he complained that American history did students a disservice by ignoring its radical figures. We choose a version of history that makes people comfortable, he said. As a result, we do nothing to encourage the kind of bold behavior that he and Dr. King and many others exhibited.

Dr. King made people uncomfortable and “put Blackness squarely in everybody’s space,” Mr. Belafonte said.

And Mr. Belafonte, with his raspy, courageous voice, did the same, for another 55 years.

READ MORE  Mike Pence. (photo: Getty Images)

Mike Pence. (photo: Getty Images)

Pence's appearance comes as Smith is believed to be wrapping up his investigation and possibly preparing to indict Trump on charges that could include obstruction of an official proceeding, conspiracy to defraud the United States and insurrection.

Prior to the riot at the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, Trump pressured Pence to summarily reject the certification of the Electoral College vote tally showing that Joe Biden had won the election. Pence refused to comply, leading Trump to denounce him at a Washington rally prior to the riot. Trump's supporters then descended on the Capitol in an effort to disrupt the certification of the election, chanting “Hang Mike Pence!” as they ransacked the building and delayed the proceedings.

On Thursday, Pence testified under oath before the grand jury for roughly seven hours about his dealings with Trump following the 2020 election.

In a video statement posted the same day, Trump repeated himself in describing the man who might yet indict him as "a Trump-hating prosecutor, Jack Smith, he’s a Trump-hater. His wife’s a Trump-hater. His family is a Trump-hater. They all hate Trump. They hate him with a passion and they’ll do anything they can to hurt Trump.”

The former president, who has a healthy lead over his Republican challengers for the 2024 GOP primary, also misspoke about which election cycle he claimed Smith was trying to influence with his investigation.

“But he's a harasser and an abuser of our people in order to obstruct and interfere with the 2020 presidential election, that’s why they’re doing it. We’re leading by a lot in the polls. If I weren’t, I believe it would all stop."

Here’s a rundown of where Smith’s investigation stands and why Trump has good reason to be concerned.

All eyes on Pence

The appearance by the former vice president on Thursday before the Washington grand jury is a significant event in Smith’s investigation. On Wednesday, an appeals court rejected a last-ditch appeal by Trump's lawyers to block Pence from testifying. Just hours later, Pence swore to tell the truth and nothing but the truth about his interactions with Trump and the plan hatched by lawyer John Eastman for Pence to reject the Electoral College tally. While the testimony already given by former members of Trump’s staff will no doubt factor into Smith's decision on whether to charge Trump with crimes, Pence is the central character in the former president's plan to subvert American democracy.

“We’ll obey the law, we’ll tell the truth,” Pence said in an interview with CBS on Sunday.

2nd firm hired by Trump confirmed absence of 2020 election fraud

While Trump spent months prior to the 2020 election declaring to the nation that it would be marred by fraud due to the use of mail-in ballots, those claims have since repeatedly been proved false. In order to charge him with conspiracy and obstruction, however, Smith will need to prove that Trump wasn’t simply wrong that fraud had cost him victory in the election, but that he pursued a strategy to overturn the results even though he knew his assertions were bogus.

To that end, Smith has subpoenaed employees of two firms that Trump’s campaign paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in the wake of the election to turn up evidence of voter fraud.

“No substantive voter fraud was uncovered in my investigations looking for it, nor was I able to confirm any of the outside claims of voter fraud that I was asked to look at,” Ken Block, founder of the firm Simpatico Software Systems, one of the firms subpoenaed by Smith, told the Washington Post. “Every fraud claim I was asked to investigate was false.”

[Pence Just Testified About Trump’s Election Theft Plot for Over Seven Hours: Rolling Stone]

Berkeley Research Group, a second firm contracted by the Trump campaign and subpoenaed by Smith, reached the same conclusion: Voter fraud significant enough to sway the results of the 2020 election had simply not occurred.

Whether Trump was made aware of the findings by Simpatico Software Systems and Berkeley Research Group is not clear, but his campaign certainly received them.

Trump fundraising under the microscope

In the two months following the 2020 election, Trump and his associates may have used his bogus election claims to raise millions of dollars from his supporters. Smith has been scrutinizing that fundraising, the Washington Post reported, which may have violated federal wire fraud laws that prohibit the use of false information over email to raise money. According to the Post, Smith has sent “subpoenas in recent weeks to Trump advisers and former campaign aides, Republican operatives and other consultants involved in the 2020 presidential campaign” in connection with the possible fundraising grift.

Fox News producer Abby Grossberg to turn over recordings to Smith

Smith's case may not implicate only Trump. On Tuesday, former Fox News producer Abby Grossberg released a recording she had made of a conversation between Fox News host Maria Bartiromo and Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, describing a plan to challenge the 2020 election results.

Grossberg, who worked with the recently fired Fox News host Tucker Carlson, is suing the network for alleged gender and religious discrimination. Earlier this month, Fox News reached a $787 million settlement with Dominion Voting Systems over bogus claims of voter fraud promoted by the network’s hosts.

MSNBC reported Tuesday that Smith had contacted Grossberg’s lawyers and was in the process of securing access to the recording of the conversation between Bartiromo and Cruz, as well as others.

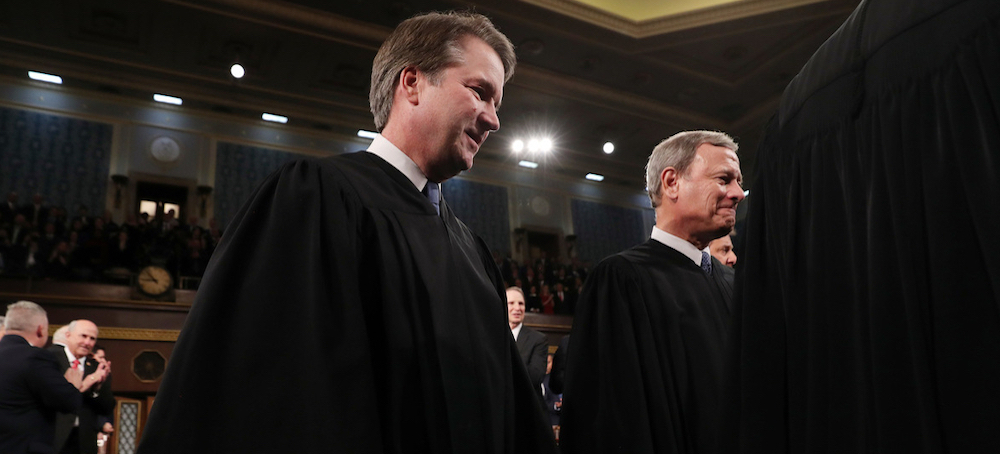

READ MORE  Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Roberts told a friend that the change was motivated by a desire to avoid the appearance of conflicts of interest, given that her husband was now the highest-ranking judge in the country. "There are many paths to the good life," she said. "There are so many things to do if you're open to change and opportunity."

And life was indeed good for the Robertses, at least for the years 2007 to 2014. During that eight-year stretch, according to internal records from her employer, Jane Roberts generated a whopping $10.3 million in commissions, paid out by corporations and law firms for placing high-dollar lawyers with them.

That eye-popping figure comes from records in a whistleblower complaint filed by a disgruntled former colleague of Roberts, who says that as the spouse of the most powerful judge in the United States, the income she earns from law firms who practice before the Court should be subject to public scrutiny.

"When I found out that the spouse of the chief justice was soliciting business from law firms, I knew immediately that it was wrong," the whistleblower, Kendal B. Price, who worked alongside Jane Roberts at the legal recruiting firm Major, Lindsey & Africa, told Insider in an interview. "During the time I was there, I was discouraged from ever raising the issue. And I realized that even the law firms who were Jane's clients had nowhere to go. They were being asked by the spouse of the chief justice for business worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, and there was no one to complain to. Most of these firms were likely appearing or seeking to appear before the Supreme Court. It's natural that they'd do anything they felt was necessary to be competitive."

Roberts' apparent $10.3 million in compensation puts her toward the top of the payscale for legal headhunters. Price's disclosures, which were filed under federal whistleblower-protection laws and are now in the hands of the House and Senate Judiciary committees, add to the mounting questions about how Supreme Court justices and their families financially benefit from their special status, an area that Senate Democrats are vowing to investigate after a series of disclosure lapses by the justices themselves.

Jane Roberts did not respond to emails with detailed questions. When reached by phone on Thursday morning, she declined to comment, as did a spokesperson for the Supreme Court.

In an emailed statement, John Cashman, the president of Major, Lindsey & Africa, said that Jane Roberts was "one of several very successful recruiters" at the firm. He attributed his recruiters' success to "the highest standards: Candidate confidentiality, client trust, and professionalism."

A spokesperson for the firm declined to comment further. A spokesperson for Macrae, the recruiting firm where Roberts now works, did not return an email requesting comment.

The affidavit, along with internal financial spreadsheets showing Jane Roberts' earnings at Major, Lindsey & Africa, were sent to congressional committees as part of a whistleblower complaint filed in December. The documents suggest that Jane Roberts was a highly successful recruiter: In the affidavit, Price says that one of the firm's partners told him that she was "the highest earning recruiter in the entire company 'by a wide margin.'" And a detailed internal spreadsheet compiled by Major Lindsey & Africa shows that Roberts' "attributed revenue" totaled $13,309,433 between 2007 and 2014. Her share of that revenue, described by the spreadsheet as payments for "commissions," adds up to $10,323,842.70.

Legal headhunting firms typically receive a share of a partner's projected compensation as a matchmaking fee. (In other scenarios, like placing lawyers in-house, recruiting firms are often paid a retainer instead of a commission.) A large chunk of that fee is typically paid to the individual recruiters who made the deal happen, and it's those payments to Jane Roberts that Price criticized.

"She restructured her career to benefit from his [John Roberts'] position," Price wrote in an affidavit accompanying his complaint. "I believe that at least some of her remarkable success as a recruiter has come because of her spouse's position."

A cover letter from Price's lawyer, Joshua Dratel, which summarizes his claims, was previously published by Politico and reported on by the New York Times, along with some details from the underlying documents, which Insider is publishing today for the first time. While the Times reported that Roberts "has been paid millions of dollars in commissions," the total figure has not been previously reported.

Mark Jungers, another one of Jane Roberts' former colleagues, said that Jane was smart, talented, and good at her job. "To my knowledge," he told Insider, "friends of John were mostly friends of Jane, and while it certainly did not harm her access to top people to have John as her spouse, I never saw her 'use' that inappropriately. In fact, I would say that Jane was always very sensitive to the privacy of her family and when she could drop the name or make certain calls, she didn't."

Insider spoke with with three legal recruiters who said $10.3 million in commission was a plausible amount for someone with Roberts' experience and network to have made over those years.

In a prior statement to the Times, a spokesperson for the Supreme Court said that the justices, including Roberts, are "attentive to ethical constraints" and obey laws governing financial disclosure. The spokesperson also told the Times that the Robertses had complied with the code of conduct for federal judges, citing an advisory opinion finding that "a judge whose spouse owned and operated a legal or executive recruitment business need not recuse merely because a law firm appearing before the judge engaged the judge's spouse." (Other advisory opinions have held that when a judge's spouse is actively recruiting for a firm appearing before that judge, or when a spouse has personally done "high level" recruitment work that generated "substantial fees," recusal would be appropriate.)

Dratel said that regardless of whether there was an actual conflict of interest, the linkage between the couple's careers looked bad. "What's the public confidence in a system when the firms which are appearing before the court are making decisions that are to the financial benefit of the chief justice?" he asked.

A series of damaging disclosures

The news of Jane Roberts's outsized earnings and the allegation that she traded on her husband's role comes as the Supreme Court faces a broader crisis of legitimacy. Only 25 percent of Americans say they have "a great deal" of confidence in the court, the lowest since Gallup started asking the question in 1974. The court has been rocked in recent weeks by a series of revelations about the behavior of sitting justices, including transactions and relationships that could lead to discipline in almost any other professional context.

First, ProPublica revealed that Clarence Thomas accepted lavish, undisclosed gifts of travel and had engaged in real estate transactions with Harlan Crow, a Dallas real-estate developer and GOP donor. That news prompted the discovery of errors in Thomas's financial disclosure forms, which he agreed to revise. This isn't the first time that Thomas has had difficulty with filing complete and accurate financial disclosure forms. In 2011, Thomas amended 13 years of forms, some of which had wrongly claimed that his wife Ginni had no outside income, when in fact she'd been paid more than half a million dollars by the conservative Heritage Foundation.

Then came the news that shortly after his confirmation to the Supreme Court, Neil Gorsuch had sold his share of a vacation property to Big Law CEO. He reported the transaction on his disclosure forms, but left the name of the buyer blank.

These disclosures came on the heels of yet another report in November that an evangelical activist orchestrated an influence campaign targeting Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. by mobilizing a network of well-heeled conservative donors to contribute to the Supreme Court Historical Society. One of those donors, the activist claims, received an early heads up about a coming decision in the Hobby Lobby case.

Last week, Sen. Dick Durbin, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, invited Roberts to "restore confidence in the Court's ethical standards" by coming on the Hill and giving public testimony. Roberts declined.

In a statement to Insider, Durbin suggested that he was close to giving up on the prospect that the Supreme Court was capable of policing itself. "The need for Supreme Court ethics reform is clear," he said. "And since it appears that the Court will not take adequate action, Congress must."

Unlike their 870 district-court and circuit-court colleagues, the nine Supreme Court justices are essentially exempt from strict compliance with the Judicial Conference's rigorous Code of Conduct; instead they only consult it as what Roberts has called a "starting point." The Supreme Court is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act or the oversight of the Office on Government Ethics. It has no internal ethics committee and no inspector general. In lieu of all these safeguards, there is a document called "Statements of Ethics Principles and Practices," which Roberts provided to Durbin.

Even the bare-bones requirement of an annual financial disclosure form is, in Roberts' view, a voluntary gesture, as "the Court has never addressed whether Congress may impose those requirements on the Supreme Court."

A previous letter from Durbin urged Chief Justice Roberts to open an investigation into Justice Thomas for conduct "that is plainly inconsistent with the ethical standards the American people expect of any person in a position of public trust." Roberts did not reply, although Judge Roslynn Mauskopf, the secretary of the Judicial Conference, did, writing that she had forwarded Durbin's letter to the conference's financial disclosure committee, which deals with "allegations of errors or omissions in the filing of financial disclosure reports." But whether that committee has the authority to discipline Thomas or any other Supreme Court Justice remains a matter of murky constitutional interpretation, to be ultimately decided by the Supreme Court itself.

Now, Price and a legal ethics expert that he consulted for his complaint say that Chief Justice Roberts may have his own disclosure issues. The millions that Jane Roberts made placing Washington lawyers into high-level jobs, described as "commission" on internal firm documents, was listed each year as "salary" on John Roberts' financial disclosure forms. (The form only requires judges to list the sources of spousal income, not the amounts.)

The balance of Roberts' income did not come at a steady rate from a single employer, as "salary" suggests. It was paid by the deal and based on a sizable cut of her clients' salaries — a compensation model which varies from year to year depending on her ability to capitalize on her network. The ultimate sources of her income were the firms hiring Major, Lindsey & Africa-backed candidates. Their identities and the specific amounts that they paid Roberts for her services remain unknown.

Price's affidavit says that John Roberts' characterization of his wife's income as "salary" is "misleading." A memo written in support of Price's complaint by Bennett Gershman, professor at the Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University who has written books on legal ethics, goes further. "Characterizing Mrs. Roberts' commissions as 'salary' is not merely factually incorrect; it is incorrect as a matter of law," Gershman wrote. "The legal distinction between these terms is clear, undisputed, and legally material. If the Chief Justice's inaccurate financial disclosures were inadvertent, presumably he should file corrected and amended disclosures."

In 2014, Price sued Jane Roberts and Major, Lindsey & Africa. He claimed that Roberts and another recruiter had collected fees for placing job candidates that were rightfully his. His complaint states that he was the only Black recruiter at the firm, and that his attempts "to recruit diverse in-house candidates" were not "only rebuffed … but also criticized as unproductive and unprofitable." Price says in his affidavit that he only met Roberts once during the years when they were colleagues; he says he discussed both her performance and Supreme Court ties with other recruiters. Price's suit was referred to an arbitrator, who dismissed Price's claims, ruling in favor of the company. But in the process, Major, Lindsey & Africa produced the spreadsheets that show Roberts' commission as well as "attributed revenue" connected to her recruiting.

Since then, Price has worked as the principal of a legal consulting firm in Boston, doing work that includes counseling other whistleblowers. It was years, he says, before he came to believe that the material he turned up in his own case should be made public. "I was worried about the potential negative effect of this disclosure on my life and career," he wrote in his affidavit. "However, with the passage of time and reflection … I've decided that, despite the risks, it is time to share with you what I know."

'Successful people have successful friends'

Legal recruiting is an established niche profession. One Washington insider compared it to being a real-estate agent. "You know your customer and what they're interested in," they said. "Then you go out and find something. The barriers to entry are low. But there are certain realtors who are well-established, even realtors who deal with billionaires. At Jane's level, no doubt she's talking to the leaders of the big law firms and they're telling her things like, well, when the attorney general steps down, we'd like to hire them. She's not making cold calls."

Recruiters get paid by the firms and companies that do the hiring — often 20 to 25 percent of a new hire's first-year compensation, which can be in the seven figures. In sworn testimony taken in 2015, included as part of Price's whistleblower disclosure and published here by Insider, Roberts gave a detailed account of the mechanics of her recruiting practice. Most of her business, she says, comes through referrals: "Successful people have successful friends."

In her testimony, Roberts said she specialized in placing current and former government officials at law firms, describing the mechanics of her job in market-oriented terms. Candidates, Roberts said, are "owned" by whomever first pitches them, and those contacts are logged in an internal company database. "The monetary value of a senior government official will depend on the value they bring to a law firm's client base," she said, "some very senior people have been basically valued at zero because the law firms don't see the business case." For that reason, Roberts said, she advises candidates — often current U.S. attorneys, cabinet secretaries, or even senators — to write a formal business plan explaining their value to elite firms.

Compensation for a retiring lawmaker, she says, "depends very much on the senator or congressperson's ability to practice law and in what areas. So sometimes their highest and best use is as a lobbyist, but they don't want to be lobbyists, so you can have, and others actually have, hard legal skills."

Roberts stresses discretion: "I keep my placements confidential. The firm keeps them confidential." Only a few, according to reporting by the Times, have become public: Robert Bennett, Brendan Johnson, Timothy Purdon, and Michael Held. Price's affidavit cites another — Kenneth Salazar, who led the Department of the Interior under President Obama. Price alleges that Roberts would have received $350,000 for Salazar's placement at WilmerHale, which has a booming Supreme Court practice. While there is no evidence that any of Roberts' placements — as opposed to the firms that hire them — have argued before the Supreme Court, a legal consultant told Politico that Roberts' "access to people is heavily influenced by her last name."

Gershman's memo cites one case, Dutra Group v. Batterton, in which the Supreme Court overruled a decision that found a WilmerHale client potentially liable for punitive damages. Roberts voted with the majority. "In my opinion, a reasonable person would want to know that the law firm on the other side of a legal dispute had recently paid the judge's household over $350,000," Gershman wrote. "Such a payment might cause a reasonable person to question the judge's impartiality."

Neither WilmerHale nor Salazar, who is now the US ambassador to Mexico, immediately responded to emails requesting comment.

In 2019, Jane Roberts left Major, Lindsey & Africa to head up the Washington office of Macrae, another legal recruitment firm, where she serves as managing partner. As with his previous forms, Justice Roberts' most recent financial disclosure gives no indication of how much money his spouse made or which law firms it came from. Nor is there any indication that she earned a commission on placements, only income paid out by "Macrae, Inc. — Attorney Search Consultants – salary."

READ MORE  Abortion rights supporters rally at the state Capitol in Oklahoma City on May 3, 2022. (photo: Sue Ogrocki/AP)

Abortion rights supporters rally at the state Capitol in Oklahoma City on May 3, 2022. (photo: Sue Ogrocki/AP)

As the last vote was cast in Nebraska, where abortion is currently banned after 20 weeks of pregnancy, cheers erupted outside the legislative chamber, with opponents of the bill waving signs and chanting, "Whose house? Our house!"

In South Carolina, Republican Sen. Sandy Senn criticized Majority Leader Shane Massey for repeatedly "taking us off a cliff on abortion."

"The only thing that we can do when you all, you men in the chamber, metaphorically keep slapping women by raising abortion again and again and again, is for us to slap you back with our words," she said.

The Nebraska proposal, backed by Republican Gov. Jim Pillen, is unlikely to move forward this year after the bill banning abortion around the sixth week of pregnancy fell one vote short of breaking a filibuster.

And in South Carolina, where abortion remains legal through 22 weeks of pregnancy, the vote marked the third time a near-total abortion ban has failed in the Republican-led Senate chamber since the U.S. Supreme Court reversed Roe v. Wade last summer.

The state has increasingly served patients across a region where Republican officials have otherwise curtailed access to abortion. Six Republicans helped block motions to end debate and defeated any chance the bill will pass this year.

Thirteen other states have bans in place on abortion at all stages of pregnancy. They are Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia and Wisconsin. Four other states have bans throughout pregnancy where enforcement is blocked by courts. The majority of those bans were adopted in anticipation of Roe being overturned, and most do not have exceptions for rape or incest.

In Utah, a judge on Friday will consider a request from Planned Parenthood to delay implementing a statewide ban on abortion clinics, set to take effect next week. Planned Parenthood argues a state law passed this year will effectively end access to abortion throughout the state when clinics next week stop being able to apply for the licenses they've historically relied on to operate.

In North Dakota, Gov. Doug Burgum signed a ban Monday that has narrow exceptions: Abortion is legal in pregnancies caused by rape or incest, but only in the first six weeks of pregnancy. Abortion is allowed later in pregnancy only in specific medical emergencies.

The North Dakota law is intended to replace a previous ban that is not being enforced while a state court weighs its constitutionality.

Pat Neal, 72, of Lincoln, was among those cheering the Nebraska vote Thursday. She, like others in attendance, expressed shock at the bill's failure.

"This gives me hope for the future," she said. "It gives me hope that the direction we've been seeing — across the country — could turn around."

The bill failed to get the crucial 33rd vote when Sen. Merv Riepe, a former hospital administrator from Ralston, abstained. Riepe was a cosigner of the bill but expressed concern this year that a six-week ban might not give women enough time to know they were pregnant.

Riepe introduced a measure Thursday that would have extended the proposed ban to 12 weeks and add to the bill's list of exceptions any fetal anomalies deemed incompatible with life.

When he received pushback from fellow Republicans, Riepe warned his conservative colleagues they should heed signs that abortion will galvanize women to vote them out of office.

"We must embrace the future of reproductive rights," he said.

Independent South Carolina Sen. Mia McLeod criticized leaders who prioritized the near-total ban over efforts to make South Carolina the 49th state in the country with a law allowing harsher punishments for violent hate crimes.

McLeod, who shared during a previous abortion debate that she had been raped, said it is unfortunate that women must reveal intimate experiences to "enlighten and engage" men.

"Just as rape is about power and control, so is this total ban," McLeod said Thursday. "Those who continue to push legislation like this are raping us again with their indifference, violating us again with their righteous indignation, taunting us again with their insatiable need to play God while they continue to pass laws that are ungodly."

READ MORE  The 110th Brigade's soldiers use tablet computers to help locate their targets. (photo: David Guttenfelder/NYT)

The 110th Brigade's soldiers use tablet computers to help locate their targets. (photo: David Guttenfelder/NYT)

With fighting in the eastern Donbas region settling into a bloody stalemate, a patch of the Zaporizhzhia region of southeastern Ukraine could prove to be the war’s next big theater.

Inside was a subterranean bunker, cut into the black earth, where Ukrainian troops from a mortar unit awaited coordinates for their next target. The men squeezed past one another down a shoulder-width dirt corridor lit with LED strips, staring at tablet computers showing a live drone feed of the terrain outside. Blast waves from artillery shells and rockets shook the bunker, and a radio crackled with a warning of incoming Russian helicopters.

But the soldiers were focused on their screens, specifically on a line of Russian troops and heavy equipment dug in a short distance away and marked with red plus signs.

That would be their target.

“The guys dug all this by hand, and they want to fight, they want to shoot,” said the unit commander, a 32-year-old with a braided ponytail who uses the call sign Shuler. “We just want to kick them off our land, that’s it.”

For the soldiers of the 110th Territorial Defense Brigade, to which the mortar unit is attached, this is a critical moment in the war.

With fighting in the eastern Donbas region settling into a bloody stalemate, their patch of the Zaporizhzhia region of southeastern Ukraine could prove to be the next big theater, a focal point of a long-awaited counteroffensive. Ukraine is under pressure to show some measure of success in bolstering morale for soldiers and civilians, shoring up Western support and reclaiming stolen territory.

The fighting here is intensely personal. Most of the soldiers of the 110th Brigade come from areas now occupied by Russia. Shuler’s unit was forced to retreat in the early days of the war, which began in February 2022, and his parents remain in occupied Melitopol, roughly 80 miles from the bunker.

Over the past year, they have slowly turned the tide, halting the Russian advance and building a network of defensive positions that the Russian military, for all its superiority in weaponry and numbers, has been unable to crack.

“We really know this location — every bush,” said Col. Oleksandr Ihnatiev, a veteran of Ukraine’s special operations forces who took command of the brigade in April last year. “From the beginning of the war, we in our strip have not lost one position or post.”

No one knows where or when the counteroffensive will kick off. It could be weeks from now, when the summer sun dries the spring mud into a hard pavement ideal for the new Western-supplied tanks and armored personnel carriers soon to enter the fight.

Or it may have already begun — for good reason, the Ukrainians will not say — with the recent probing attacks on Russian positions east of the Dnipro River in the neighboring Kherson Region, or with the rotation of new units to Zaporizhzhia. Recently, the lines here were bolstered by the arrival of an elite, British-trained artillery unit that had previously been deployed outside Bakhmut.

A military push by Ukraine in the Zaporizhzhia region makes strategic sense, military officials and experts say. By punching south through the Russian lines and driving hard toward the Sea of Azov, Ukraine’s military could split Russian forces in half, severing important supply lines and dealing a blow to the war aims of Russia’s president, Vladimir V. Putin.

Zaporizhzhia makes up the heart of a land bridge that Russian forces seized in the early weeks of the war that links Russian territory to the occupied Crimean Peninsula. It is one of the Kremlin’s few tangible successes in Ukraine.

But the combat challenges are daunting. Ukraine’s success will require overcoming heavily armed defensive lines that Russian troops have spent the past 10 months reinforcing, as well as its own military’s shortcomings. Supplies of artillery and air-defense ordnance are dwindling. American officials have said that it is unlikely the counteroffensive will result in a significant shift in momentum in Kyiv’s favor.

After 14 months of nonstop fighting, Ukrainian soldiers are exhausted.

Shuler’s hands now shake uncontrollably, the result of a concussion suffered when a tank round exploded near him at the beginning of the war.

A history teacher before the invasion, Shuler views the looming fight within a broader context. He wears a patch with a Star of David on his arm, a reminder of his great-grandparents who died in the Holocaust. His Jewish grandfather had to change his name to sound more Russian when the Soviets took control of his native western Ukraine at the end of World War II.

Now, Shuler must hide his face, refusing to be photographed for fear that his parents could suffer reprisals from the occupiers.

“Imagine the situation, you’re alive, but your life has been taken away,” he said. “We’ll have nowhere to return to if we don’t stop this, if we don’t end it, if we don’t win.”

Flowers Blooming Alongside Corpses

At the far end of the bunker, closest to the Russian lines, soldiers rolled open another trapdoor — this one made of metal and plastic sheeting, and built on a track — exposing the muzzle of an Iranian-made HM16 mortar to a blue sky. It was a demonstration of the ingenuity that has kept the smaller, weaker Ukrainian armed forces in the fight.

Though practically under the Russians’ noses, the mortar team is largely invisible in the underground shelter, even to the Russian drones that are constantly buzzing overhead.

“Postril!” a soldier yelled. Fire! A fat mortar round shot in the direction of a group of about 10 Russian soldiers that a reconnaissance team had identified in a nearby tree line. The shock wave from the mortar’s report reverberated down the length of the bunker, compressing lungs and rattling teeth.

“If we end up hitting it, some will be turned into meat,” said the unit’s 36-year-old technical sergeant, who uses the call sign Shamil. “We’ll scare them a bit.”

A few seconds later, a puff of smoke erupted on the screen of Shamil’s tablet. They overshot and would have to try again.

Shuler complained that their Iranian weapon, which he believed had been confiscated by the United States and delivered to Ukraine, was less accurate than Western-built models. And the Pakistani and Soviet-era shells they have in their arsenal, while sufficient in quantity, at times failed to detonate.

Still, the 110th Brigade is in far better shape than it had been at the start of the war, when it had only about 100 men to fight the Russian forces who poured into the Zaporizhzhia region from Crimea after Mr. Putin announced the invasion.

A young battalion commander with the brigade who uses the call sign Polyak said he and his men initially had nothing but shovels to defend themselves with. “The first day, we had to move like caterpillars,” Polyak said. “We couldn’t even stand up; the Grads were never ending. And gradually, we crawled and crawled and crawled.”

The intensity of that early fighting is evident in a swath of annihilated villages that stretches along the Zaporizhzhia front. Mangled armored vehicles sit parked between burned-out houses. Soldiers said they had tried to collect most of the bodies of those killed in the fighting, but on a recent day, the skeletonized remains of a Russian soldier, still dressed in a green camouflage uniform with a hammer and sickle belt buckle, lay in the yard of an abandoned home, red tulips and yellow daffodils blooming nearby.

Colonel Ihnatiev, the brigade’s commander, said his men alone had killed more than 900 Russian soldiers in more than a year of fighting and had destroyed some 150 armored vehicles. The 110th Brigade, he said, now has several thousand soldiers, the majority of whom had never touched a weapon before the war began.

“It was not easy,” Colonel Ihnatiev said. “There was a lot of crying and whining, but we were able to mold the tears and the snot into character.”

To press forward in any counteroffensive, he said, his men would need additional armor and reinforcements from other units. Some of that aid has already begun to arrive.

Ready for More Action

The incoming shells howled overhead, their explosions getting closer and closer as Russian troops stationed about a mile away adjusted their cannon’s trajectory.

But the Ukrainian artillery team positioned to return fire was unfazed. The men joked as they loaded shells into their Australian-made howitzer in the shade of a cherry tree, swatting away bees that hummed around its white spring blooms. They fired. And fired again.

After the fifth round, the Russian side fell silent.

These Ukrainian soldiers are part of an elite, British-trained artillery unit attached to an airborne assault brigade. A month ago, they were stationed near Bakhmut burning through a thousand shells a week as they mowed down waves of Russian infantry. And before that, they took part in the liberation of Kherson.

Given their skills and experience, it was puzzling to some of them why they were sent to this corner of the war.

“Maybe it is connected with our offensive. Maybe it is a distraction maneuver,” said a junior sergeant with the unit, named Maksim, who goes by the call sign Stayer. “We don’t see the whole picture.”

The Russian military clearly believes that the Zaporizhzhia region is critical to the war. After a winter hiatus, Russian forces have begun to pound Ukrainian military positions, as well as cities and towns, with an array of weaponry, including artillery shells, guided missiles and Iranian-made explosive drones. This could be a sign that Russian forces are preparing for their own assault — or anticipating a Ukrainian one.

Stayer, 39, said his men were ready for more action.

“When there’s an offensive, there’s movement, it’s fun,” he said. “You’re shooting at them, they’re shooting at you.”

In Bakhmut, there was never even time to sleep, Stayer said. The muck and fatigue of battle had so changed his appearance that his iPhone’s face recognition system ceased to work for a bit, he said. Inside his phone was a horror show: drone photographs of fields littered with Russian bodies blown apart by the mortars his team had fired at them.

In Zaporizhzhia, Stayer has enough time in between artillery volleys to run 10 kilometers every other day and indulge his passion for coffee, which he has delivered from a specialty roaster called Mad Heads in Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital.

The counteroffensive, though, is on everyone’s minds, he said. Using a rock, Stayer drew on the wet ground what he thought the outlines of an operation might entail: a push south toward the port city of Berdiansk, accompanied by feints on the eastern front and perhaps an attempt by Ukrainian forces stationed in Kherson to cross the Dnipro River to attack Russian forces dug in on the eastern bank.

“It all looks very simple,” he said. “We’re waiting to see what our high command comes up with, some kind of clever plan.”

For Civilians, Renewed Hope

A pensioner who longs to return home to his ailing sister. An exiled small-town mayor who is already drawing up plans to rebuild once the Russians are gone.

Since the beginning of the war, the city of Zaporizhzhia, the regional capital, has been a refuge for thousands who have fled the Russian takeover of towns and villages farther south. But for many, it has never become a home.

Now like never before, talk of a counteroffensive has begun to buoy hopes that they will someday go back.

“I think our guys will get going soon and give it to them right in the …” Volodymyr Mateiko, a retired truck driver, said, finishing the sentence with a vulgarity.

Mr. Mateiko, 65, left Melitopol, а large occupied city about 75 miles south of Zaporizhzhia, in August, after Russian troops entered his home with guns and stole his television, computer and other belongings. He left behind his ailing older sister and the graves of his parents and wife, and settled in a shelter for exiles like him in Zaporizhzhia, where he has a bottom bunk in a large communal room and not much else.

“Here, I don’t know who I am,” he said. “A bum maybe, a refugee. I don’t know.”

The regional government estimates that there are about 230,000 people living in Zaporizhzhia who have been displaced by the war.

Though excited by the prospect of returning home, many worry about the destruction any counteroffensive might wreak.

Irina Lipka, the exiled mayor of Molochansk, a small town north of Melitopol, said Ukrainian forces had already begun carrying out strikes on Russian bases in the town, including a former school where she was a teacher, something she described as painful but necessary.

“This is war,” Ms. Lipka said. “There is no other way to de-occupy.”

Scanning the Night Sky for Drones

When darkness falls over the Zaporizhzhia front, the challenges ahead for the Ukrainian Army become starkly apparent. On a recent night, Russian troops unleashed volley after volley of strikes from multiple-launch rocket systems called Grads, which briefly lit up the sky. In response, the Ukrainian side managed to shoot off an occasional artillery shell.

Watching all of this from across a farm field, members of an air-defense team with the 110th Brigade cursed as they sucked down cigarettes. Armed with a machine gun on the back of a pickup truck, the team was posted to guard against explosive Shahed drones, which Russia launches from nearby occupied territory.

Even the most dedicated soldiers now admit that the war is beginning to wear on them. A private named Vitaly said a friend, who had returned home from Israel to fight, was recently killed near Bakhmut. The unit’s commander was also dead.

Dogs barked incessantly, and a Russian Orlan surveillance drone soared overhead, the light from its thermal camera nearly indistinguishable from the stars in the sky. There was a flash, and the whoosh of several incoming shells sent the team diving into the mud.

“Of course, after a year and two months of war, everyone is tired,” Vitaly said. “But without victory, no one is going to leave here.”

As midnight approached, clouds moved in, obscuring the stars and a crescent moon, making it easier for Russian drones to escape detection. Across the field, the battle still raged in the dark.

READ MORE  Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva of the Workers' Party, flanked by two Indigenous women leaders, during a ceremony at the Museum da Amazonia in Manaus, Brazil. (photo: Edmar Barros/AP)

Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva of the Workers' Party, flanked by two Indigenous women leaders, during a ceremony at the Museum da Amazonia in Manaus, Brazil. (photo: Edmar Barros/AP)

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has decreed six new indigenous reserves, banning mining and restricting commercial farming there.

Indigenous leaders welcomed the move, but said more areas needed protection.

Lula, who took office in January, has pledged to reverse policies of his far-right predecessor Jair Bolsonaro, who promoted mining in indigenous lands.

Lula, who previously served as president in 2003-2010, signed the demarcation decree on Friday - the final day of a gathering of indigenous people from around the country in the capital Brasília.

"We are going to legalise indigenous lands. It is a process that takes a little while, because it has to go through many hands," the 77-year-old leader told the crowds.

"I don't want any indigenous territory to be left without demarcation during my government. That is the commitment I made to you."

And in a tweet, Lula described the decision as "an important step".

Recent years have seen an alarming rise in deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, a crucial buffer in the global fight against climate change.

The new reserves are in central Brazil, as well as the country's north-east and south.

The presidential decree grants indigenous people exclusive use of natural resources on the reserves. All mining is banned, and there are tighter rules for commercial farming and logging.

While hailing Lula's decision, some indigenous leaders pointed out that his government had vowed to recognise 14 new territories.

During his time in office, Mr Bolsonaro made it his mission to push economic development in the Amazon.

He repeatedly argued that by mining in indigenous territories, Brazil - which relies heavily on imported fertilisers - could build more of its own potassium reserves. That argument has been questioned by some experts.

READ MORE  Fish and coral in the ocean's "twilight zone." (photo: WIRED)

Fish and coral in the ocean's "twilight zone." (photo: WIRED)

Less food is falling to dimly lit waters, home to specially adapted marine life – but emissions cuts would stem decline

The twilight zone lies between 200 metres and 1,000 metres below the surface and is home to a variety of organisms and animals, including specially adapted fish such as lantern sharks and kite fin sharks, which have huge eyes and glowing, bio-luminescent skin.

Twilight zone animals feed on billions of tonnes of organic matter, such as dead phytoplankton and fish poo, which drifts down from the ocean’s surface. The drifting particles are known as marine snow.

Warmer waters were in effect reducing the quantity of food that sunk down to the zone, meaning up to 40% of life in the twilight waters could be gone by the end of the century, according to the study, which was published in Nature. Recovery could take thousands of years.

“The rich variety of twilight zone life evolved in the last few million years, when ocean waters had cooled enough to act rather like a fridge, preserving the food for longer and improving conditions allowing life to thrive,” said Katherine Crichton, the study’s lead author and a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Exeter.

“According to the studies we have done, 15m years ago there wasn’t all this life [in the twilight zone] and now, because of human activity, we may lose it all. It’s a huge loss of richness,” Crichton told the Guardian. “Unless we rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, this could lead to the disappearance or extinction of much twilight zone life within 150 years, with effects spanning millennia thereafter.”

Warmer oceans also reduced carbon storage, said Cardiff University’s Paul Pearson, the principal investigator on the study. This is because the “carbon that is sinking down as part of the marine snow” is eaten mostly by microbes nearer the surface, instead of falling further. Less sinking means a faster carbon release.

Crichton said the good part about the studywas that “we don’t seem to have reached an irreversible point. We can’t avoid some loss, but we can avoid the worst if we control emissions.”

Although poorly understood, the twilight zone “contains possibly the world’s largest and least exploited fish stock, and recycles [about] 80% of the organic material that sinks”, according to a UN programme that studies the region.

Crichton said: “We still know relatively little about the ocean twilight zone, but using evidence from the past we can understand what may happen in the future.” Her team’s findings suggested “significant changes may already be under way”.

The study offered three possible futures for the twilight zone: a low-carbon scenario, which allows for a total of 625bn tonnes of emissions from 2010 onward; a medium scenario, which allows for 2,500bn tonnes; and a high one, allowing for 5,000bn tonnes. “If we get to the medium or high scenario both are very bad news for the twilight zone,” Crichton said.

To put the emission figures in context, the University of Exeter-led Global Carbon Budget estimated that in 2022, total global CO2 emissions reached 40.6bn tonnes. Emissions have been close to 40bn tonnes every year from 2010-22, so most of the CO2 in the study’s low-carbon scenario has already been emitted.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.