Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Thirty years later, an avoidable tragedy has spawned a politically ascendant mythology.

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms suspected the Davidians of illegally converting semi-automatic rifles into fully automatic weapons. (The weapons allegations seemed to inspire more reason for action than reports that Koresh was sexually assaulting his followers’ underage daughters.) During the ensuing investigation, A.T.F. agents repeatedly overestimated their capacity for subterfuge. When a group of undercover agents posing as college students moved into a house across the street from the Branch Davidian compound, their rental cars gave them away. The agents hosted a party to deflect suspicion, but it had the opposite effect: “Some of the Branch Davidians showed up, mingled, and reported back to Koresh that these were federal agents for sure,” Jeff Guinn writes, in the recently published “Waco: David Koresh, the Branch Davidians, and a Legacy of Rage.” Another agent, Robert Rodriguez, posed as a potential follower to gain access to the group. Koresh quickly pegged him as a Fed but kept inviting him to Bible study anyway; after all, as he reminded his followers, Jesus had preached to a Roman centurion.

The day before the Sunday-morning raid, Treasury Department officials in Washington attempted to call it off, concerned that it relied on unnecessary force. Why couldn’t Koresh be arrested when he was away from the compound? But a plan, once in motion, has a certain momentum, and the A.T.F., which had a congressional budget hearing approaching, was in need of a splashy, successful operation. One A.T.F. agent was so confident that the mission would be over in a few hours that he booked tee time in Houston for Sunday afternoon.

On the morning of February 28, 1993, Rodriguez, still ostensibly undercover, listened as Koresh was tipped off that a raid was imminent. Rodriguez rushed to report the news to his superiors, sure that they would abort the mission, since the plans relied on maintaining the element of surprise. Instead, the raid proceeded, disastrously. Agents swarmed the compound and were met with heavy gunfire. When the battle ended, a few hours later, four federal agents and six Branch Davidians were dead, and many more wounded on both sides.

The fifty-one-day siege that followed deteriorated into the most dangerous kind of conflict, one in which both sides felt as though they were backed into a corner. This was much more true for the Branch Davidians, of course, who were barricaded in a compound with plenty of canned food and bullets but a dwindling water supply. But the federal agents surrounding them also felt a sense of desperation. The raid, intended as a show of A.T.F. competence, had instead devolved into a prolonged spectacle of defeat. “The hostages were not those Davidians in there,” Bob Ricks, the F.B.I. special agent in charge of the operation, said later. “The hostage in this whole process was the F.B.I. We had to respond to the demands of David Koresh. We were like actors in his play . . . In the final analysis, everything rested under the control of David Koresh.”

As the siege wore on, tensions emerged between the F.B.I.’s negotiators and its Hostage Rescue Team (H.R.T.), specialized units that preferred to resolve conflicts quickly, through the tactical use of force. (Shortly after the shoot-out, the F.B.I., which is responsible for investigating the deaths of federal agents, took command of the operation.) Negotiators believed that Koresh could eventually be coaxed into surrendering peacefully, though the dominant H.R.T. view was that Koresh was a liar who would never emerge of his own volition. The two F.B.I. factions were working at cross-purposes: a negotiator would make headway with the Davidians only to learn that the tactical team had just run over one of Koresh’s beloved vintage cars with a tank.

Weeks into the siege, Koresh claimed that he would surrender peacefully as soon as he finished writing a treatise on the Book of Revelation. Davidians had been communicating with the outside world via messages painted on bedsheets, hung out of windows. Then they displayed one reading “Let’s Have a Beer When This Is Over.” Instead, the tactical faction received approval to end the situation more rapidly. Early on the morning of April 19th, federal agents rammed the Mount Carmel building with tanks and pumped tear gas into the holes they had created. Around noon, someone reported seeing flames. Agents expected to see people flooding out of the building to surrender, but only nine did; more than seventy others, including two dozen children, were crushed as the building collapsed, died by suicide, or were killed in the fire. (One toddler died of a stab wound in the chest.) The government’s heavy-handed, deeply flawed approach enabled Koresh’s transmutation into a martyr.

The Branch Davidians appeared to see a kinship between their struggle and those of other victims of state violence; one of their bedsheet messages read “Rodney King We Understand.” In the decades since, the people who have got the most mileage out of the tragedy have told a narrower story, one of a powerful and oppressive federal government waging war on gun-loving, God-fearing citizens. (In this fable, the Davidians are implicitly coded as white, even though at least two dozen of them were not.) Timothy McVeigh travelled to Texas during the siege, where he sold bumper stickers with slogans like “Fear the Government That Fears Your Gun” and “A Man with a Gun Is a Citizen, A Man Without a Gun Is a Subject.” McVeigh, who was already steeped in white-supremacist rhetoric, became obsessively focussed on Waco. On the second anniversary of the fire, he blew up the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, in Oklahoma City. Five years later, Alex Jones attached himself to efforts to rebuild a church in Mount Carmel. Jones was then twenty-five, had recently been fired from his job as a talk-radio host in Austin and had just launched Infowars. He led a memorial service, during which other speakers referred to the events in 1993 as “our second Alamo.” “All of it—it’s all about public opinion,” Jones told a reporter that day. A few months later, Jones would release a video, “America: Wake Up or Waco,” in which he claims that F.B.I. agents intentionally machine-gunned women and children. The film follows the template that Jones has used successfully ever since—using the government’s real failures to build a paranoid mythology that he bends to sinister ends.

That mythology, and its attendant rhetoric of grievance and aggression, is politically ascendant in many parts of the country, even as its most vocal proponents consider themselves beset on all sides by enemies. Earlier this month, congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene staged her own mini-confrontation with the A.T.F., showing up at a gun store in Smyrna, Georgia, during a routine inspection. “This is a prime example of Joe Biden and the Democrats weaponizing federal agencies to silence and intimidate their political opponents,” she tweeted later. “I fear this is just the beginning and they are directly targeting our Second Amendment and our right to protect and defend our families.” Koresh and his followers wanted to be left alone; the growing cohort of self-identified Christian nationalists want control of school boards, city councils, and state legislatures. The kind of tactical-firearms training that the Davidians used to prepare for their war with Babylon is now a significant nationwide industry, one that attracts dentists and real-estate agents to weekend classes on urban combat. And there are twice as many privately owned firearms in the U.S. as there were when the Waco siege took place.

READ MORE  The case has returned the Supreme Court to an issue it had said it was ceding to elected officials in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade. (photo: Michael A. McCoy/The New York Times)

The case has returned the Supreme Court to an issue it had said it was ceding to elected officials in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade. (photo: Michael A. McCoy/The New York Times)

In an emergency application, lawyers for the government asked the justices to stay all of a Texas judge’s ruling suspending a commonly used abortion medication.

The administration’s brief, in the first major abortion case to reach the justices since they eliminated the constitutional right to abortion in June, asked the court to pause parts of an appeals court ruling that had limited the availability of the pill, mifepristone.

“If allowed to take effect, the lower courts’ orders would upend the regulatory regime for mifepristone, with sweeping consequences for the pharmaceutical industry, women who need access to the drug, and F.D.A.’s ability to implement its statutory authority,” the brief said.

READ MORE  U.S. Army Sgt. Daniel Perry, center, and his attorney Doug O'Connell, left, walk out of the courtroom during jury deliberations in his murder trial, Friday, April 7, 2023, at the Blackwell-Thurman Criminal Justice Center in Austin, Texas. (photo: Jay Janner/AP)

U.S. Army Sgt. Daniel Perry, center, and his attorney Doug O'Connell, left, walk out of the courtroom during jury deliberations in his murder trial, Friday, April 7, 2023, at the Blackwell-Thurman Criminal Justice Center in Austin, Texas. (photo: Jay Janner/AP)

The 76 pages filed by Travis County prosecutors also reveal messages dating back years in which Perry, an Army sergeant, talked about killing people — several times referencing a desire to kill Muslims.

In a 2019 message, for example, Perry wrote it was "to [sic] bad we can't get paid for hunting Muslims in Europe."

The documents released Thursday were filed on March 27, when prosecutors announced their intent to introduce messages and posts they'd gathered from Perry's cellphone. Some of Perry’s messages were presented during his trial, including a May 31, 2020, social media post where he said he might have to kill people. But the newly unsealed filing contains dozens of other posts and messages that weren’t presented publicly.

Each piece of evidence is listed separately in the 76 pages. They include Internet searches for news about George Floyd-related protests, posts of memes that appear to encourage or rationalize shooting protests, and Perry's own messages in which he talks about being angry and scared over the protests or writes about committing violence.

Perry on Friday was convicted in Austin in the killing of 28-year-old Garrett Foster in downtown Austin during a Black Lives Matter protest on July 25, 2020.

In a near-unprecedented move Saturday, Abbott said he would recommend that Perry be pardoned even though Perry has yet to be sentenced. Abbott tweeted Perry should have been protected by Texas' stand-your-ground laws because he was acting in self-defense. The governor blamed Perry's prosecution on a "progressive" district attorney.

The Chronicle has reached out to Abbott's office for comment. Perry’s attorney Doug O'Connell did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Weeks before Foster's death, Perry in a May 2020 Facebook message exchange told a friend he "might have to kill a few people" who were rioting outside his apartment complex.

The friend wrote to Perry: "Can you catch me a negro daddy."

"That is what I am hoping," Perry responded.

Other messages talked of going to Dallas "to shoot looters" and included "white power" memes.

Social media posts compared BLM movement to monkeys

Some of Perry’s social media posts have been public knowledge for years. Soon after he was identified as the person who shot Foster, activists flagged tweets in which Perry said that protesters from New York or Minneapolis should be sent to Texas.

“Send them to Texas we will show them why we say don’t mess with Texas,” Perry said. He was responding to a tweet by former President Donald Trump, in which Trump wrote that “protesters, anarchists, agitators, looters or lowlifes” in Democrat-led cities would face “a much different scene if they were in Oklahoma.

On May 30, 2020, he referred to protests and riots as “monkey s---” after writing that his favorite barbershop had been burned down. Days later, he compared the Black Lives Matter movement to a “zoo full of monkeys” and said people were acting like “animals at the zoo.”

Perry wrote that he initially supported the protest movement, but changed his stance when rioting and looting began.

Other items that filing says messages were found on Perry’s phone include a undated meme that uses the n-word and complains about Black people being racist; a meme that advises people “pick up your brass” if they encounter rioters; and a May 29 text to another person that shows a photo of a building with a sign on it that says “WHITE POWER, White county power … light co.”

Jury found killing of Garret Foster was murder, not self-defense

In July 2020, Perry was driving for Uber when he made a right turn into an intersection full of protesters in downtown Austin. Foster, who was a protester, approached the driver’s side of Perry’s car while carrying an AK-47 rifle. Perry rolled down the window and, seconds later, used a revolver next to him to shoot and kill Foster.

Both Perry and Foster were legally armed, and Perry claimed that the shooting was in self-defense. More than a year after the shooting, he was indicted and charged with murder and aggravated assault.

During a 10-day trial, Perry’s defense team attempted to portray the protesters as an angry mob and said Foster was carrying his rifle in a threatening manner, which meant Perry had the right to shoot him under Texas’ self-defense laws. Prosecutors contended that Perry deliberately drove into a group of peaceful protesters and lost his right to self-defense by provoking the confrontation with Foster.

Perry was found guilty by the jury last week.

Perry's attorneys have filed a motion for a new trial, arguing they should have been allowed to present evidence they said proved Foster was the aggressor in the confrontation between the two men.

READ MORE  Dakota Access pipeline opponents face law enforcement agencies, near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation on Feb. 2, 2017, outside Cannon Ball, N.D. (photo: Michael Nigro/Pacific Press)

Dakota Access pipeline opponents face law enforcement agencies, near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation on Feb. 2, 2017, outside Cannon Ball, N.D. (photo: Michael Nigro/Pacific Press)

More than 50,000 pages of documents were recently made public after the company behind the Dakota Access pipeline lost a court case to keep them secret.

By October, TigerSwan — founded by James Reese, a retired commander of the elite special operations Army unit Delta Force — had established a military-style pipeline security strategy.

There was one nagging problem that threatened to unravel it all: Reese hadn’t acquired a security license from the North Dakota Private Investigation and Security Board. Although Reese claimed TigerSwan wasn’t conducting security services at all, the state regulator insisted that its operations were unlawful without a license.

TigerSwan turned to Jonathan Thompson, the head of the National Sheriffs’ Association, a trade group representing sheriffs, for help. The security board “has a problem understanding and staying within their charter,” Shawn Sweeney, TigerSwan’s senior vice president, wrote to Thompson. If he could “discuss possible political measures to apply pressure it will assist in the entire project success [sic],” the employee appealed.

Thompson was enthused to work with TigerSwan. “We are keen to be a strong partner where we can help keep the message narrative supportive [sic],” he wrote back. “[C]all if ever need anything.”

Despite Thompson’s offer of assistance, TigerSwan continued to operate in North Dakota with no license for months. The company managed dozens of on-the-ground security guards, surveilled and infiltrated protesters, and passed along profiles of so-called persons of interest to one of the largest midstream energy companies in North America.

The revelation of TigerSwan’s close working relationship with the National Sheriffs’ Association is drawn from more than 50,000 pages of documents obtained by The Intercept through a public records request to the North Dakota Private Investigation and Security Board. In 2017, the board sued TigerSwan for providing security services without a license. The state eventually sought a $2 million fine through the administrative process, but TigerSwan negotiated a $175,000 fine instead — well below standard fines for such activities.

A discovery request filed as part of the case forced thousands of new internal TigerSwan documents into the public record. Energy Transfer’s lawyers fought for nearly two years to keep the documents secret, until North Dakota’s Supreme Court ruled in 2022 that the material falls under the state’s open records statute. Because an arrangement between North Dakota and Energy Transfer allows the fossil fuel company to weigh in on which documents should be redacted, the state has yet to release over 9,000 disputed pages containing material that Energy Transfer is, for now at least, fighting to keep out of the public eye.

The released documents provide startling new details about how TigerSwan used social media monitoring, aerial surveillance, radio eavesdropping, undercover personnel, and subscription-based records databases to build watchlists and dossiers on Indigenous activists and environmental organizations.

At times, the pipeline security company shared this information with law enforcement officials. In other cases, WhatsApp chats and emails confirm TigerSwan used what it gathered to follow pipeline opponents in their cars and develop propaganda campaigns online. The documents contain records of TigerSwan attempting to help Energy Transfer build a legal case against pipeline opponents, known as water protectors, using the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, a law that was passed to prosecute the mob.

The Intercept and Grist contacted TigerSwan, Energy Transfer, the National Sheriffs’ Association, as well as Thompson, the group’s executive director. None of them responded to requests for comment.

To TigerSwan, the emergence of Indigenous-led social movements to keep oil and gas in the ground represented a business opportunity. Reese anticipated new demand from the fossil fuel industry for strategies to undermine the network of activists his company had so carefully gathered information on. In the records, TigerSwan expressed its ambitions to repurpose these detailed records to position themselves as experts in managing pipeline protests. The company created marketing materials pitching work to at least two other energy companies building controversial oil and gas infrastructure, the records show. TigerSwan, which was staffed heavily with former members of military special operations units, branded its tactics as a “counterinsurgency approach,” drawing directly from its leaders’ experiences fighting the so-called war on terror abroad.

TigerSwan did not just work in North Dakota. Energy Transfer hired the company to provide security to its Rover pipeline, in Ohio and West Virginia, the documents confirm. By spring 2017, TigerSwan was also assembling intelligence reports on opponents of Energy Transfer and Sunoco’s Mariner East 2 pipeline in Pennsylvania.

The documents from the North Dakota security board paint a detailed picture of counterinsurgency-style strategies for defeating opponents of oil and gas development, a war-on-terror security firm’s aspirations to replicate its deceptive tactics far beyond the Northern Great Plains, and the cozy relationship between businesses linked to the fossil fuel industry and one of the largest law enforcement trade associations in the U.S. The impetus for spying was not simply to keep people safe but to drum up profits from energy clients and to allow fossil fuels to continue flowing, at the expense of the communities fighting for clean water and a healthy climate.

“For them, it was an opportunity to help create a narrative against our tribe and our supporters,” said Wasté Win Young, a citizen of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and one of the plaintiffs in a class-action civil rights lawsuit against TigerSwan and local law enforcement. Young’s social media posts repeatedly showed up in the documents. “We weren’t motivated by money or payoffs or anything like that. We just wanted to protect our homelands.”

The Intercept published the first detailed descriptions of TigerSwan’s tactics in 2017, based on internal documents leaked by a TigerSwan contractor. Nearly six years later, there have been no public indications that the security company obtained major new fossil fuel company contracts. Meanwhile, corporate lobbyists spurred the passage of so-called critical infrastructure laws widely understood to stifle fossil fuel protests in 19 states across the U.S. Collaborations between corporations and law enforcement against environmental defenders have proliferated, from Minnesota’s lake country to the urban forests of Atlanta.

No significant regulatory reforms have been enacted to prevent firms from repeating counterinsurgency-style tactics. And TigerSwan is far from the only firm to use invasive surveillance strategies. The North Dakota documents show that at least one other private security firm at Standing Rock appears to have utilized similar schemes against pipeline opponents.

“We need to always be very clear that the industry knows what a risk the climate movement is,” said May Boeve, the executive director of 350.org, a climate nonprofit that was repeatedly mentioned in TigerSwan’s marketing and surveillance material. “They’re going to keep using these kinds of strategies, but they’ll think of other things as well.”

TigerSwan’s Surveillance Gospel

“Gentlemen, as you are aware there has been a shift in environmentalist and ‘First Nations’ groups regarding the tactics being used to prevent, deter, or interrupt the oil and gas industry,” said a February 2017 email drafted by TigerSwan employees to a regional official at ConocoPhillips, a major oil and gas producer — and a potential TigerSwan client.

“Recently in our area the situation has become extremely tense with ‘protestors’ using terrorist style tactics which are well beyond simple civil disobedience,” the email continued. “If steps have not already been taken to prevent and plans to mitigate [sic] an event or events like these to Conoco I may be able to suggest some solutions.”

TigerSwan’s marketing materials read like a playbook for undermining grassroots resistance. ConocoPhillips was just one of the companies the private security firm had in its sights.

In another case, a PowerPoint presentation drafted for Dominion, which was building the Atlantic Coast natural gas pipeline through three mid-Atlantic states, offered detailed profiles of local anti-pipeline groups and individuals identified as “threat actors.” (The planned pipeline was canceled in 2020.) TigerSwan laid out the types of services it could provide, including a “Law Enforcement Liaison” and access to GuardianAngel, its GPS and mapping tool. (Neither ConocoPhillips nor Dominion responded to questions about whether they hired the security firm.)

In January 2017, a TigerSwan deputy program manager emailed a presentation titled “Pipeline Opposition Model” to Reese and others, explaining that it was meant to serve as a business development tool and a “working concept to discuss the problem.” The presentation claimed external forces had helped drive the Standing Rock movement and pointed to outside tribes, climate nonprofits like 350.org, and even billionaires like Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, who had a “vested interest in DAPL failure” because of their investments in the rail industry.

Water protectors used an elaborate set of social movement theories to advance their cause, another slide hypothesized, including “Lone Wolf terror tactics.” Specifically, TigerSwan speculated that pipeline opponents could be using the “hero cycle” narrative, a storytelling archetype, to recruit new movement members on social media and energize them to take action — a strategy, the presentation said, also used by ISIS recruiters.

Anyone whose work had touched the Standing Rock movement could become a villain in TigerSwan’s sales pitches. One PowerPoint presentation included biographical details about Zahra Hirji, a journalist who worked at the time for Inside Climate News. Another included a photo of a water protector’s former professor and her course list.

As a remedy, the company offered up a suite of “TigerSwan Solutions.” To the security firm, keeping the fossil fuel industry safe didn’t just mean drones, social media monitoring, HUMINT (short for human intelligence, such as from undercover personnel), and liaising with law enforcement officials and agencies — all included on its list — it also meant local community engagement, counter-protesters, building a “pipeline narrative,” and partnering with university oil and gas programs.

“Win the populace, and you win the fight,” the presentation stated, repeating a key principle of counterinsurgency strategy.

Reese approved: “I’d like to have these cleaned up and branded so I can use,” he wrote back.

Reese used similar material to shore up his relationship with existing clients. In December 2016, he requested a copy of a presentation titled “Strategic Overview,” which he hoped to send to Energy Transfer supervisors working on building the Rover natural gas pipeline. The presentation, a version of which The Intercept previously published, draws heavily from a 2014 report by the Republican minority staff of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, claiming that a “club” of billionaires control the environmental movement.

In a memo called “The Standing Rock Effect,” TigerSwan lays out a set of seven criteria the company had developed for identifying anti-pipeline camps sprouting up across the country. “TigerSwan’s full suite of security offerings offsets the risk these camps pose to a company’s bottom line,” the company concluded.

TigerSwan utilized its promotional materials to target both energy companies and states with oil and gas resources. In April 2017, the security firm and the National Sheriffs’ Association planned to brief more than 50 state employees in Nebraska, including staffers in the governor’s office, the state Emergency Management Agency, and the State Patrol, on the “lessons learned” from the Dakota Access pipeline protests. A contractor for the National Sheriffs’ Association wrote that the briefing was in part “to prepare the state of Nebraska for the Keystone Pipeline issues coming in months ahead.”

Target: Water Protectors

TigerSwan’s obsessive tracking of environmental activists is laid out in detail in the North Dakota documents. Assisted at times by National Sheriffs’ Association personnel, the company targeted little-known water protectors, national nonprofits, and even legal workers.

The first page of a template for intelligence sharing encouraged TigerSwan employees to enter information about any “New Person of Interest.” TigerSwan personnel routinely referred to its targets as “EREs,” short for environmental rights extremists, apparently a version of the Department of Homeland Security’s classification of “Animal Rights/Environmental Violent Extremist” as one of five domestic terrorism threat categories.

A document labeled “Background Investigation: 350.org” helps explain why the company kept tabs on a national environmental organization with little visible presence on the ground at Standing Rock. Using an “Influence Rating Matrix,” TigerSwan ranked 350.org’s “formal position in organization/movement” and its “criminal history” as 0 — but gave its highest rating of 5 to the group’s size, funding, online presence, and history with similar movements.

TigerSwan also attempted to dig up dirt on legal workers with the Water Protector Legal Collective, which represented pipeline opponents. The security company used the CLEAR database, which is only available to select entities like law enforcement and licensed private security companies, to dig up information on attorney Chad Nodland. The company concluded that Nodland was also representing a regional electric cooperative that generates some of its power through wind — apparently considered a rival energy source to the oil the Dakota Access pipeline would carry. (Nodland told The Intercept and Grist he never worked for the cooperative.) TigerSwan also put together a whole PowerPoint presentation on Joseph Haythorn, who also worked for the legal collective and submitted bail money for clients to be released.

At the same time, the National Sheriffs’ Association was building its own profiles and sharing them with TigerSwan. In one instance, a contractor for the sheriffs’ group passed along a six-page backgrounder on LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, a prominent Dakota Access pipeline opponent and historian, to TigerSwan. The document included statements Allard made to the press, her public appearances, social media posts, and details about tax liens filed against her and her husband.

Targeting individual pipeline opponents like Allard seems to have been part of TigerSwan’s strategy particularly when it needed to have something to show its client, Energy Transfer Partners. In one exchange with employees, Reese suggested digging up more intelligence on a pipeline opponent who goes by the mononym Tawasi.

“We need to start going after Tawasi as fast as we can over the next couple weeks so we can show some more stuff to ETP,” Reese wrote, using an abbreviation for the company’s old name, Energy Transfer Partners. The documents show that TigerSwan kept close tabs on Tawasi, reporting his movements in daily situation reports, monitoring his social media, and at one point noting that he had gotten a haircut.

Tawasi, who had a large social media following but was not a prominent leader of the anti-pipeline movement, was bewildered that he had been so closely monitored. “They didn’t have anything at all,” he told The Intercept and Grist. “And they picked me as somebody that they thought they could make something out of.”

“It makes me feel unsafe,” he said, “because the same contractors could be working for a different company, still following me around under a different contract from the next oil company down the line.”

Prairie McLaughlin, Allard’s daughter, said records of TigerSwan’s activities remain important, even six years later. “It matters because it gives somebody a handbook on what could happen — what might happen.”

Not a “Mercenary Organization”

After The Intercept published its first set of leaked TigerSwan documents in 2017, the company attempted to downplay the impact of the revelations. In a memo, TigerSwan shrugged off the story’s importance. “The near-term impact of the article is positive for the company,” TigerSwan claimed. The revelations had caused water protectors to limit their social media activity, rendering them “incapable of effectively recruiting members, raising operational funding, or proselytizing,” TigerSwan wrote.

The company intended to use “information operations” to maintain the paranoia: “This looking over-their-shoulder behavior will continue for several months because of internal suspicions and targeted information operations.”

Internally, the company scrambled to mount a public relations response, calling on help from Chris LaCivita, a Republican political consultant now reportedly being considered for a senior role in Donald Trump’s 2024 presidential campaign. A memo emailed to LaCivita by TigerSwan’s external affairs director said that, as a defensive strategy, the company would assert on background that “TigerSwan is not a ‘mercenary organization.’” It was a point that must never be made on the record, the document says, because it “would be like saying ‘no I don’t beat my wife.’” (LaCivita did not immediately respond to a request for comment.)

TigerSwan’s offensive strategy primarily consisted of trying to marshal evidence showing that water protectors were violent lawbreakers, professional protesters, un-American, and not even very Indigenous. The document author advised TigerSwan to locate “Any visuals, video of demonstrators waving flags or using insignia of an enemy of the United States.” Another suggested talking point said, “Upon our arrival, we quickly learned that a vast majority of the protestors were not indigenous not [sic] part of the peaceful water movement.”

In a final act of law enforcement collaboration, the memo advised TigerSwan to identify one local and one federal law enforcement source who could defend them — but only off the record.

Outside the public relations strategy, TigerSwan didn’t dramatically shift its tactics in response to the story, the documents suggest. In an email dated June 20, 2017, nearly a month after The Intercept’s first exposé, an intelligence analyst distributed a list of anti-pipeline camps across South Dakota, where the Keystone XL pipeline was supposed to be built.

“Maybe your folks can take a look at the list, check the social media for the sites, and figure out if A) you can get in and B) if there’s value to being inside and C) do you have the creds you need to get in. If you figure out that you need to attend some more events to build cred and access we can do that,” he said. “That should feed the beast until the next shiny thing.”

READ MORE  The Wingstop logo on the front door of the original Wingstop restaurant in Garland, Texas. (photo: Wingsider)

The Wingstop logo on the front door of the original Wingstop restaurant in Garland, Texas. (photo: Wingsider)

Prices aren’t going down. “Excuseflation,” explained.

The most common traditional explanation is an imbalance between supply and demand — “too much money chasing after too few goods,” as Milton Friedman put it. Most economists say that the supply chain disruptions contribute as well. But supply chain problems have eased in recent months, easing some supply concerns, and the Federal Reserve has been steadily raising interest rates, slowing job growth as a way to balance out the demand part of the equation. So why are prices still so high?

Tracy Alloway, a Bloomberg journalist and co-host of the financial podcast Odd Lots, thinks the answer may be, in part, the fact that many companies are increasingly turning to a strategy known as “price over volume.”

Translate that into plain English and you get something like “chasing fat profits.”

“So you’re selling fewer products, but you’re selling them at higher prices,” Alloway told Today, Explained co-host Noel King on a recent episode of the show. “It’s a viable strategy in the current environment.”

Today, Explained spoke to Alloway about this corporate strategy and the reasoning they use to justify price hikes to their customers in the first place, a phenomenon she’s dubbed “excuseflation.”

You recently identified a phenomenon that you call “excuseflation.” Tell me what it means.

I think a lot of people at this point have heard about this idea that companies, you know, maybe they’re taking advantage of the current environment in order to raise prices and really gouging their customers.

The thing about excuseflation is it’s sort of grounded in truth. It’s the idea that companies are using these once-in-a-lifetime disruptions. Think about the supply chain hiccups that we’ve had. Think about the Ukraine-Russia war. And they’re using those one-off disruptions as an excuse to raise prices. And that sounds fair enough. You know, companies, they have expenses. If their input costs go up, maybe it makes sense for them to pass some of those on to customers. But where it starts to become insidious is when they’re raising prices so much that they’re seeing their profits go up quite substantially as well.

Can you give me an example of something that has been excuseflated?

Sure. So one of my favorite examples, because, you know, I love these personally, but chicken wings. Let’s talk about chicken wings and Wingstop. Wingstop is a very large purveyor of very delicious chicken wings. And what they’ve been saying on their earnings calls is that they have been raising their prices for their delicious chicken wings. And the reason they’ve been doing that is because the wholesale cost of your basic chicken wing went up quite a lot during the pandemic. We had a lot of disruptions at various farms, chicken farms with labor shortages and things like that. So it made sense that chicken wing prices went up and the company started passing those on to consumers.

The issue now, though, is that we have seen a substantial drop in chicken wing prices. And yet the company isn’t saying that it’s going to start dropping its prices. What it’s discovered, much like a lot of other businesses at the moment, is that actually this strategy of making up what you lose in sales volume with higher prices, so you’re selling fewer products, but you’re selling them at higher prices, [is] a viable strategy in the current environment, and it’s working for a lot of companies because profit margins are up.

Listen, you are an economics reporter. You see what’s happening. You are still buying chicken wings. Why are you not furious? Why have you not put your foot down?

First of all, let me say that my personal price elasticity when it comes to chicken wings is probably infinite. But, you know, I will pay whatever it takes to eat Buffalo wings.

Wingstop is listening!

We spoke to the owner of a bakery over in Chicago. And, you know, I think there’s a tendency when you think about things like greedflation or excuseflation, you think about these big corporations, these really sophisticated corporations that are, you know, formulating their pricing strategies and how to get the most out of customers. But this is a phenomenon that also is endemic in smaller and midsize businesses. And this baker in Chicago kind of laid it out for us. He said:

Whether it’s rye flour or bird flu, that impacts eggs when it makes national news just running a business, it’s an opportunity to increase the prices without getting a whole bunch of complaining from the customers. It’s not that we’re out there price gouging, but, you know, timing can be everything. —Ken Jarosch, owner of Jarosch bakery, as heard on Odd Lots

Shouldn’t competition push prices down? If I’m a business owner, I’m going to let consumers know that I can get them stuff much cheaper than the other guys who have excuseflated everything. Shouldn’t that be happening?

This is really the key thing about excuseflation and where it differs a little bit from greedflation. If a company starts raising its prices just because it can, then in theory, according to the basic rules of capitalism and economics, someone should come in and undercut them and steal all their business away. But the thing about excuseflation is it allows companies to raise prices all at the same time and all together.

The economist Isabella Weber, she basically says what it does is it gives companies de facto monopoly power. So you think about the reason that we tend not to like monopolies as consumers. We want, you know, a vibrant landscape of lots of smaller businesses that are all competing with each other so that we get a better value for our money. What happens when you have an industry-wide event that gives a group of businesses an excuse to raise prices: They are all effectively, not officially, but effectively acting as a monopoly. They can all say, well, you know, it’s bird flu, so we’re all going to raise the prices of our eggs.

When it comes to specific company examples, you know, Pepsi has been pushing their prices higher for a while. And you would think that, well, customers can just buy Coke instead, but actually Coke is pretty much doing the same thing. And so you end up having these industries who are all acting together. And that means that there’s very little incentive for them to start lowering prices because they’re not seeing that competitive pressure.

We tend to think of monopoly power as this, you know, kind of static thing. So you might have one big company that dominates an industry, and that’s a classic monopoly. Consumers don’t have a lot of other options. But, in fact, monopoly power can be a fluid and temporary thing. So when you see a supply bottleneck or when you see an industry-wide disruption, it can lead to this situation where companies all start acting very similarly. They all start doing the same thing.

It’s almost, you know, I hesitate to use these words because they have legal connotations, but it’s almost like a de facto cartel, right? Everyone decides to raise their prices all at once because whatever crucial component or input cost is going up. That leads to an automatic monopoly. It feels the same to a consumer who finds that, actually, they don’t have a lot of options because one group of businesses is raising their prices all together, all at the same time.

READ MORE  Migrants cross the Acandi River on their journey north, near Acandi, Colombia, Wednesday, Sept. 15, 2021. (photo: Fernando Vergara/AP)

Migrants cross the Acandi River on their journey north, near Acandi, Colombia, Wednesday, Sept. 15, 2021. (photo: Fernando Vergara/AP)

Deal with Panama, Colombia seeks to stem ‘illicit crossings’ of dangerous jungle route used by US-bound asylum seekers.

The US Department of Homeland Security said on Tuesday that a deal had been reached with the Panamanian and Colombian authorities to address “irregular migration” through the so-called Darien Gap.

The 60-day campaign seeks to “end the illicit movement of people and goods through the Darien by both land and maritime corridors”, as well as open “new lawful and flexible pathways for tens of thousands of migrants and refugees”, the department said in a statement.

The countries would also launch a plan to reduce poverty and create jobs in border communities in Panama and Colombia, it added, without going into further detail.

Almost immediately, observers questioned how the effort would function in practice.

“The externalization of the US border continues,” Al Otro Lado, an organisation that provides legal and other assistance to migrants and refugees in the US and Mexico, tweeted on Wednesday.

“The language in this statement is vague on purpose. How exactly do they intend to end migration thru the Darien Gap + ‘reduce poverty, create jobs’ in 60 days? What are these alleged ‘new lawful + flexible pathways’?”

Nearly 250,000 migrants and refugees crossed through the Darien Gap last year, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) – nearly double the number of people who took the route in 2021.

“The stories we have heard from those who have crossed the Darien Gap attest to the horrors of this journey,” Giuseppe Loprete, the IOM’s chief of mission in Panama, said in a statement in January.

“Many have lost their lives or gone missing, while others come out of it with significant health issues, both physical and mental, to which we and our partners are responding.”

The administration of US President Joe Biden, which promised to reverse some of former President Donald Trump’s most hardline, anti-immigration policies, has nevertheless sought to deter migrants and asylum seekers from reaching the country’s southern border with Mexico.

Biden has been under political pressure domestically to address an increase in arrivals at the frontier and is now considering another plan that the United Nations refugee agency has warned could violate US obligations under international refugee law.

The proposal – dubbed an “asylum ban” by critics – would effectively block asylum seekers who arrive at the US-Mexico border from accessing protection in the US if they did not first apply for asylum in Mexico or another country they crossed earlier in their journeys.

Many people crossing the Darien Gap say they have no other choice as they face poverty, gang violence, political persecution and other crises in their home countries.

The IOM reported that a majority of those who crossed in 2022 – just more than 150,000 people – were from Venezuela, which has experienced a mass exodus amid years of socio-economic and political upheaval.

Ecuadorians, Haitians and Cubans also figured prominently among those who took the mountain route, which is rife with violence and natural hazards, including insects, snakes and unpredictable terrain.

Nearly 88,000 crossings were recorded in the first three months of 2023, the Reuters news agency reported, citing official Panama migration data.

On Wednesday, a senior Biden administration official told The Associated Press that US forces would “assist their Colombian and Panamanian counterparts with intelligence gathering to dismantle smuggling rings” in the Darien Gap.

“The official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss details that have not been made public, said migration through the Darien would not end, but the campaign is expected to have significant impact,” the news agency reported.

The official did not specify whether US forces involved in the 60-day campaign would be military or civilian law enforcement, AP said.

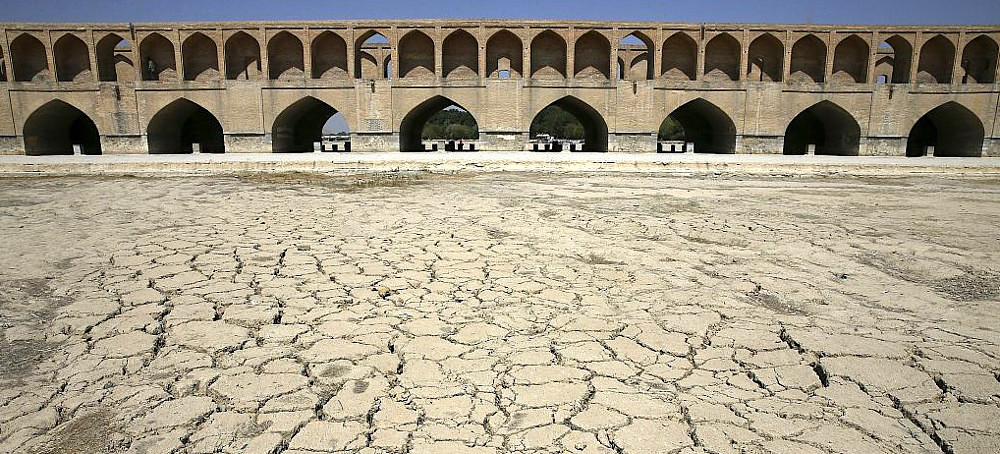

READ MORE  In this Tuesday, July 10, 2018 photo, the Zayandeh Roud river no longer runs under the 400-year-old Si-o-seh P

In this Tuesday, July 10, 2018 photo, the Zayandeh Roud river no longer runs under the 400-year-old Si-o-seh P

As global warming continues, more abrupt dry spells could have grave consequences for people in humid regions whose livelihoods depend on rain-fed agriculture. The study found that flash droughts occurred more often than slower ones in parts of tropical places like India, Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and the Amazon basin.

But “even for slow droughts, the onset speed has been increasing,” said Xing Yuan, a hydrologist at Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology in China and lead author of the new study, which was published Thursday in Science. In other words, droughts of all kinds are coming on more speedily, straining forecasters’ ability to anticipate them and communities’ ability to cope.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.