Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) recounts the night an armed man shouted at her and her husband outside their Seattle home — and how threats of political violence haunt and alter the lives of elected officials.

Everyone could hear the men on the street. The car, a black Dodge Challenger with gold rims, sped down the block, just past the congresswoman’s house. Two voices shot through the dark. “HEY, PRAMILA,” the first man shouted. “F--- YOUUUUU.” Then came the second: “F--- you, c---!”

The neighbors knew the car. It was the same Dodge Challenger they had seen several times that summer. But Pramila Jayapal didn’t know this yet.

She was on the couch, watching the psychological thriller “Mindhunter” with her husband, Steve Williamson. It was July 9 in Arbor Heights, a West Seattle neighborhood laid out in neat sweeps of grass and pavement. They paused the show. Williamson got up and went outside. The items on the porch sat undisturbed: sneakers, turquoise Crocs, a dog leash, two hanging plants swaying in the night air. Then they heard the men again. Security footage picked up what the men said and the sound of heavy-metal music coming from the car. One shouted something about “India,” the country where Jayapal was born. The voices were hard and clear. “F---ing c---,” one of them said.

“Tell Pramila to kill herself — then we’ll stop, motherf---er.” Then came a honk. Then another long “F--- YOUUUUU.” On the porch, Williamson waved an index finger and went back inside. The men drove off.

Inside, Jayapal picked up her phone and dialed 911. But when she saw the car leave, she hung up before it could connect. Maybe she should contact the Capitol Police, the D.C. agency that protects members of Congress. She wasn’t sure. Maybe she had been doxed. There had been instances of obscene yelling at the house that summer, this she knew. She had reported those to Capitol Police. But she didn’t know then what dozens of pages of police reports and court filings would later reveal — that one of her visitors that night had been there before, in the same Dodge Challenger. She didn’t know that he had driven by her house between three and seven times since late June, or that the other male voice that night belonged to his adult son, as he would later tell investigators. She didn’t know that from the house across the street, her neighbor had seen the Dodge earlier that same evening, or that down the block, another neighbor had seen it, too, just a week before. She didn’t know that the man in the Dodge had emailed her congressional office back in January, to express his distaste for her political party, and for her, the 56-year-old three-term Democrat from Seattle, the chair of the House Progressive Caucus and a high-profile antagonist to Donald Trump.

“I am a freedom loving nonregistered libertarian who votes in every election no matter how big or small,” the man wrote in his email.

“You, Pramila, are an anti-American s---pit creating Marxist.”

“We are incompatible.”

Jayapal didn’t know that his distaste would mutate into action. When she heard the yelling stop, when the men drove off into the night, she had no idea that one of them would be back a half-hour later to yell some more, and that he’d have a loaded .40-caliber semiautomatic pistol on his hip, later seized by police.

On paper, at least, the whole thing was over in 47 minutes. But the anatomy of political violence is more tangled than the events of a single case. Threats against members of Congress have risen year after year, according to data from the Capitol Police: 9,625 in 2021, up from 3,939 in 2017. Officers logged nearly 2,000 cases in the first three months of this year alone. Among the statistics, there are thousands of stories like Jayapal’s, each one unraveling with its own special complexity in the lives and homes of elected officials.

“We sign up for a lot of things,” Jayapal said, sitting in her backyard. “It should not be that you get this kind of abuse and racism and sexism directed at you. But you have to accept it if you want to do this job.”

Talking about that night now, five weeks later, in the house where Jayapal and Williamson have lived for almost six years, those 47 minutes take on new life. They have shown Jayapal just how many gaps exist in congressional security. The system is like a “black box,” she said, and she is lobbying House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) to fix it. They have changed the way she goes about her work as a public official, physically and psychologically — the routes she drives, the tracking device she keeps on her phone, the alarm it sounds when she unwittingly comes within 1,000 feet of the man with the Dodge. It already happened once, on her way to an appointment on a Sunday in August. They have changed the way she thinks about her home, too. The house looks different now — she and Williamson see all the ways it needs to be “hardened.” So did the neighborhood. The block “had been such a safe space,” Jayapal said. Now it was “tainted.”

“We felt threatened,” she said. “We still do.”

The man, identified by police as 49-year-old Brett Forsell, is out on bail. He lives seven blocks away.

11:03 p.m.

Even while it happened, as she ducked out of view from the front door on a couch in her den, Jayapal could feel how ill-prepared she was to deal with the questions that came next: how to protect her home, who would pay for it, what to keep private, what to share with the public.

Around 11 p.m., Jayapal’s phone rang.

A woman’s voice came on the line. “Hi, this is Seattle 911. We got a hang-up call from you. Is everything okay?”

“Yeah, thanks for calling back. This is Congresswoman Jayapal,” she said, according to a recording of the call. There was a tremor in her voice. “I am okay.”

Jayapal handed the phone to her husband. Williamson told the 911 operator that he’d heard one of the men in the Dodge say he was going to come back “every day.” The operator said she could have the Seattle Police Department get in touch. “It’s totally up to you,” she said.

The congresswoman was back on the line. She wasn’t sure.

“Umm, what do you think is best?”

Jayapal decided to contact the Capitol Police. She woke up Rachel Berkson, her deputy chief of staff and district director, at home in Seattle. Berkson emailed and texted her contacts at the Capitol Police but couldn’t get through to anyone that night. It was after 2 a.m. on the East Coast.

The house was quiet again. On her phone, Jayapal opened the encrypted app Signal and scrolled to a chat named “Gallery Group.” Last year, on Jan. 6, she had been one of several dozen members of Congress trapped on the balcony of the House gallery, the last to evacuate the chamber as rioters stormed the Capitol. While their colleagues on the main floor below were able to leave, rioters pounded on the balcony doors. There was no sense of how or when they would get out. Afterward, Jayapal organized a text chain for the Democrats in the group. They did therapy sessions together, at least three of them. The Signal chain has become a space to vent. “It’s, ‘I’m dealing with this today. I need some support,’” Jayapal said, “which is really unusual in Congress. We all operate like individual fiefdoms.” Republicans had been on the balcony that day, too, but she didn’t invite them to the Signal group. “I don’t know that it would have felt like it was a safe space,” she said. “Honestly, we never tried.”

At 11:03 p.m., Jayapal tapped out a text: “For the second time in a week, I’ve had people outside my house screaming f---ing c--- commie b----, we’re coming back every night, go kill yourself pramila. Reporting it to cap police of course as we did the last two times with nothing done.”

A few of the members on the chain were awake. I’m so sorry this is happening, they said. What can we do to help you? Others wouldn’t wake up on the East Coast until hours later.

“It’s triggering,” Jayapal wrote to the group.

That night, the thoughts of Jan. 6 returned “immediately,” she later recalled, tears in her eyes. The same noises that have stayed with her came back again — the yelling, the pounding on the doors outside in the hallway, the anger. “I could just feel myself, like, ‘OK, I’m back. I’m back there.’”

Elected in 2016, the same year as Trump, Jayapal became the first Indian American woman to serve in the House. She was “the anti-Trump,” her husband said, a “bright light in an otherwise dark night.” And she made the job as big as she could. She became a cable news regular. She stepped in as a mentor to the most liberal women in the House, the members of “the Squad.” She assailed Trump’s policies as “cruel” and “xenophobic,” and branded him the leader of a “cult.” In 2019, Jayapal helped lead the public case for Trump’s first impeachment, and it was around that time that Williamson started installing security cameras outside their home. Now she is the sole chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, corralling its 101 members as she balances the demands of the left with real influence in President Biden’s White House.

Before entering politics, Jayapal spent 20 years in the advocacy world. After the World Trade Center fell on Sept. 11, 2001, she organized against anti-Muslim bias. She got threats then, too. “I’ve had people forever telling me to go back to India,” she said after the July incident outside her home. “But I will say that this was different. This was really different.”

By the time the Dodge Challenger came, Jayapal had read about other incidents of political violence across America. There was the man in New Hampshire, sentenced to 33 months in prison after threatening to hang members of Congress who didn’t support Trump. There was the man in Alaska, sentenced to 32 months after sending threatening voice mails to his Republican U.S. senators. Two weeks after the incident at Jayapal’s home, a man in New York charged the stage at a campaign event, lunging for Republican Rep. Lee Zeldin. On Capitol Hill, two of Jayapal’s male colleagues, Reps. Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.) and Eric Swalwell (D-Calif.), publicly released audio from voice mails they’d received. “Gonna get your wife, gonna get your kids,” a man told Kinzinger. “Cut his wife’s head off, cut his kids’ heads off,” another told Swalwell.

Jayapal got voice mails, too, and these felt different. She’d talked often with other women of color in the House about the threats they’d received, and the racism and sexism laced through the audio files. But she didn’t feel like she could, or should, release them. There was a tension there: “I don’t really want people to know it affects me,” she said. “And at the same time, so much of my work as an activist, and as a member of Congress, is to share vulnerability.”

After the Dodge left on the night of July 9, Jayapal poured herself a glass of Scotch.

Otis, her 70-pound labradoodle, had been too scared to bark when the noise started. In the front den, he lay down on the floor at the foot of the couch, and put his head between his two long paws.

Williamson said his first instinct had been to go on the porch, to face the men and wave them off: “Like, ‘Hey, go home,’ you know.” He figured they’d had too much to drink. “I think I surprised them,” he told the 911 operator. But Jayapal felt palpable alarm. Once they’d been able to discuss the incident in the days that followed, the couple attributed the difference to Williamson’s view as a White man, and Jayapal’s as a woman of color. “I’ve been in the mainstream in many ways,” Williamson said. “It’s very different for her.”

There was a moment like this on Jan. 6, in the House gallery. Jayapal remembered a colleague, a White man, telling the group to remove their congressional pins, the little lapel amulets reserved for the 435 members of the House of Representatives. It would help them blend in, the colleague said to the others on the balcony. Jayapal said she and other members of color glanced around. If they took the pins off, Capitol Police might not know they were people to protect. “Enough of us have had the situation where Capitol Police doesn’t recognize us as members,” she said. “And if we keep them on, we’re gonna get tagged by the insurrectionists.”

“Which one do we want to do?”

Jayapal kept her pin on.

11:13 p.m.

The Dodge Challenger came back, revving once, then twice. The sound of heavy metal music sounded in the street again, before the car came screeching to a stop in front of Jayapal’s house, just a few steps north of the property line.

Again, Williamson came out to the porch. He lifted his phone and started filming.

“Hey, guess what, a--hole,” the driver, Forsell, said.

This time he was here alone.

Again, security cameras picked up the sound.

“I’m your new f---in’ neighbor,” he said.

Williamson was still filming as he turned backward toward the door. “Call 911,” he told his wife.

“Call the f---ing police if you want,” Forsell said.

Then Williamson heard the sound of metal hitting metal. He’s owned handguns before, and the noise made his body react. He wondered if someone was chambering a round. It was dark outside, and hard to see. The unwelcome visitor was in front of the house. Police did not identify the source of the sounds, but later found the remains of a large gray tent, half assembled across the street, a pole sticking out from the tarp, along with a sleeping bag in the front of the Dodge.

Back in the house, Jayapal again dialed 911.

Williamson walked upstairs to try to see what he could from the window. He advised his wife to come upstairs, too. They worried the man was on their property.

This time, the call connected. Another woman came on the line: “911 — what’s your emergency?”

“We have people at the front door who are looking for me. This is Congresswoman Jayapal.”

“I’m sorry?” the operator said.

Again, Jayapal’s voice was shaking.

Upstairs with his wife, Williamson thought this visit felt different from the one less than an hour earlier. “It was like he was owning the space, demonstrating power over the situation, and real determination, combined with that same anger,” he recalled. They were both scared.

Jayapal explained again: “We have people at the front door who have been harassing us. This is Congresswoman Jayapal.”

There was a muffled sound in the background as Williamson tried to say something.

“Yes. I’m, I’m — I’m telling them, babe,” Jayapal said, according to a recording of the call. “They were yelling ‘c---,’ ‘b----,’ ‘go kill yourself.’”

“Oh, God. Okay, okay,” said the operator. “I’m gonna stay on the phone with you, one second.”

“Are they still there?” Jayapal asked her husband.

“They have not left. They have not left,” he said.

“They have not left,” Jayapal repeated into the phone.

The operator asked for a description of the car.

“Steve, can you see what color it is?”

“I’m not going outside,” he said.

“No, no, no, it’s okay,” said the operator.

“I think he’s on the front porch,” Williamson said.

“We think he’s on the front porch,” Jayapal said. “I don’t know if these are the same people as came a half an hour ago when I first called.”

“Oh, you had called earlier?” the operator asked.

There was the sound of typing in the background.

“Oh,” Jayapal said, “he’s yelling again.”

“The guy’s yelling again?”

“He’s yelling again.”

“Okay, hold on. All right, hold on.”

Nine minutes after the call began, Jayapal and Williamson saw flashing lights. They watched through the window.

Police were yelling. “Walk backward! Walk backward!”

At 11:23 p.m., just before Forsell was detained, a security camera captured him saying, “I’m setting up camp. It’s my right as an American.” He informed police he had a gun on his right hip. It was a registered .40-caliber Glock with a round in the chamber, according to the police report. Forsell was taken into custody. In the back of the car, he told police he had been “peacefully protesting.”

Jayapal dialed a 1-800 number for the Capitol Police. She spoke to the officer on call. “I literally didn’t know what to do,” the congresswoman said. Weeks later, Jayapal would assemble a four-page letter to Pelosi with recommendations to improve member security. One thing she wants is a basic flowchart — a real-time, step-by-step guide to dealing with a threat. “There have been a lot of us who have been feeling very frustrated, frankly, that there’s not a more coordinated response to the things that happened,” she said. “A lot of members feel like these things go into a black box.” If you are a high-profile person of color in politics, a person “who does get targeted more,” Jayapal said, “there’s real inequities around this. It means we don’t have as much money for staff and office as other members do.”

At 11:59 p.m., Jayapal pulled up Signal again.

“Well either he or others came back,” she wrote to the Gallery Group. “This one has a gun, a loaded Glock. We called the cops.”

“It’s actually helping me just to be able to text you all,” she added.

11:25 p.m.

Inside the house, Jayapal retrieved her Scotch. Then, “for some bizarre reason,” she recalled, she started blasting Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive.” And then she started to cry.

She didn’t go to sleep for a long time. After 2 a.m., she sent a final message to the Gallery Group. “Update: we should definitely have a discussion about security,” Jayapal wrote.

“Local police arrested this guy. I spoke with Capitol police and their threat assessment person. It feels like they are on it. Taking seriously that someone with a gun is out in front of a members house. Let’s see what happens.”

For more than an hour, Forsell sat in the back of a police car, his conversation captured on video. He said he’d made a point of driving by Jayapal’s house regularly, just to roll down his window and call out “the hypocrisy” of the Democratic Party. “I pulled up in front of the house. I got out. I pulled out my tent. The guy opened the door, and I said, ‘Hey, a--hole, I’m your new neighbor.’ That was it,” he said. In the video, Forsell appeared calm, making small talk with the officers on the scene. There were bursts of frustration as dispatch radio chatter came through from the front seat. There were “real” crimes being committed elsewhere, he said. “I have broken no law.” He said he struggled with “mental issues,” and argued he was exercising his First Amendment rights when he came to Jayapal’s block.

Inside the police car, Forsell said he had respect for the police on the scene, but none for the political process. “You should have that b---- in handcuffs, ’cause she’s a f---in’ traitor to this country,” he told authorities. “I just don’t see what law I’ve broken, and I’m very well-versed in the law.”

Police documents describe Forsell as a longshoreman and lifelong resident of West Seattle. In his original email to Jayapal, dated Jan. 5, he said he had watched his hometown morph from a “relatively beautiful and safe city into the filthy and violent s---pit that it is now.” Sitting cuffed in the back of the car, he said he’d pitched his tent on Jayapal’s block just as scores of homeless people did across downtown Seattle. He said he carried his pistol for protection and would not use it unless his life was at risk. “The socialists come into power? I want a gun,” he said. He told the officers he wanted to buy an AR-15, in case Democrats banned them.

Forsell said he would come back to Jayapal’s house. “I’ll keep doin’ it. And you can let her know that I will in no way physically harm her,” he said, unless she harmed him. “But I will continue to drive by here and voice my opinion, until she goes back to India — or something else.”

The remarks, picked up by the police video recording, were cited by the King County prosecutor on the case, Gary Ernsdorff, in his request for bail in the amount of $500,000. “The defendant, a White male, targeted a woman of color who is a sitting member of the U.S. House of Representatives,” Ernsdorff wrote. A judge later reduced bail to $150,000 over the objection of the state.

Forsell was charged with felony stalking and has pleaded not guilty.

Forsell’s lawyer, Robert Flennaugh, did not respond to multiple calls and emails. Forsell did not respond to a request for comment.

Ernsdorff said: “Our First Amendment is very strong, but at some point, you can’t yell fire in a movie theater. We take these kinds of cases very seriously and very cautiously.”

Ernsdorff said his office did consider a possible hate crime charge. The investigating detective said she did not believe a hate crime had been committed, according to a copy of her report, describing the case instead as a crime of stalking and harassment. During an interview with Seattle FBI agents on July 10, according to police records, Forsell denied stepping onto Jayapal’s property and said he did not make comments about her race or ethnicity, or say anything “regarding statements of Jayapal killing herself.” In security footage from Forsell’s 10:38 p.m. visit, the one with his son, the men are not visible, but one of the two male voices on the tape can clearly be heard saying “Tell Pramila to kill herself.” The detective was not able to definitively match who said what, she wrote in a summary of the investigation. Forsell also told the FBI agents that his actions toward Jayapal were a symptom of his struggles with mental illness, and that he is “biased against Jayapal for no other reason than her political beliefs and status as a Democrat,” the detective wrote.

The case is now in its preliminary stages. At a hearing scheduled for Oct. 4, the two parties will have the chance to move toward a plea or a trial. Until then, as part of the conditions of his release, Forsell is prohibited from possessing a firearm and required to wear a GPS tracking device. He isn’t allowed to go within 1,000 feet of Jayapal, her house or her office — a restriction that the congresswoman, too, has to monitor with the police-provided tracking app on her phone. She was told she is one of the first people in Seattle to use it, and the notification system has been buggy. The app has just two buttons: a red circle labeled “Panic,” and a gray one labeled “Dispatch.”

Since July 9, she’s changed how she drives to the airport, to the grocery store, to events downtown — how she takes walks around the neighborhood. The main roads in Arbor Heights, the ones she used to take, would potentially put her within 1,000 feet of Forsell. It slows her down a bit, but what bothers her more is the state of vigilance she now assumes mentally — the “constant reminder of an outstanding threat.”

In the days that followed the police cars and the arrest, colleagues came up to her on Capitol Hill to ask questions about the security measures available to them. At one point, a committee chairman told her he didn’t even have a security system at home. “And it just made me realize there were all these people who either hadn’t thought about it, didn’t know what was possible, or didn’t know what was necessary,” she said. About a month before Forsell came to her home, Jayapal was one of 27 Democrats to vote against expanded security for Supreme Court justices and their families. A spokesperson for the congresswoman said Jayapal voted no because she wanted the bill to go further, covering employees and federal judges.

In August, Jayapal asked Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.), the chair of the House Democratic Caucus, to convene a call. Pelosi was on. So was Chief J. Thomas Manger from the Capitol Police and the House sergeant-at-arms, Maj. Gen. William J. Walker. More than 100 members of Congress joined. On Aug. 15, Jayapal laid out her recommendations in a letter to Pelosi: basic requirements for home security; clear security protocols for members and their spouses, including “Run, Hide, Fight” training, developed by the Department of Homeland Security; centralized points of contact for the many agencies involved.

“Currently, it is left to the Member to coordinate amongst all these agencies and figure out who is doing what,” Jayapal wrote to Pelosi. “This is a full-time job in the case of a serious threat assessment.”

Later that day, the congresswoman was driving from her house to an event in Seattle, celebrating the introduction of a trans bill of rights. Berkson, her district director, was behind the wheel. In the passenger seat, Jayapal pulled out her phone and played some of the voice mails she’d received.

A man’s voice filled up the car.

“ … Your f---in’ day is coming. God damn, as soon as the president’s installed, like on Nov. 4 or 5, we’re f---in’ coming after all you motherf---ers. You’re gonna be scrubbing f---in’ floors for the rest of your life, you f---in’ wh---.”

Another man, a trace of a smile in his voice.

“ … Get ready for the worst year of your life. It’s gonna be turmoil every day. This is gonna be fun. This is gonna be fun. Your life is gonna be miserable. And we’re gonna get rid of that corrupt Biden, and that socialist Kamala, and the rest of the group, and you’re going right along with them.”

His voice deepened.

“You stupid f---in’ b----. Get ready for turmoil. You’re gettin’ it. You’re gonna get exactly what you deserve, b----. Have a nice day, b----.”

Then another man.

“ … I’m gonna send you some knee pads, you f---in’ b----. You worthless f---in’ c---.

“ … We’re coming. And we’re really pissed off.

“ … You are an evil b---- and you need to die and I hate you and I will never vote for you again.”

Jayapal stopped the recordings. Berkson, in the front seat, was one of the staffers who screened the messages. She decides what to forward to Capitol Police, and what to bring to Jayapal’s attention. As she drove, she started to cry. “Sorry,” Berkson said. “I honestly don’t think about it that much.”

At home later that night, Jayapal listened again to the threatening voice mails that Kinzinger and Swalwell released this summer. She thought about how violence begins with the ability to dehumanize the subject of that violence. And she spent that evening replaying the voice mails that had been left for her. There was one calling her an animal. “The unleashing of it everywhere creates this space for other people to be unleashed as well,” she said.

She thought about her decision to talk about what happened. What would she and Williamson be saying, to themselves, to each other, to their loved ones, if they did? “I don’t really want to admit that we’re in danger,” Williamson said, “because that’s not a place I want to occupy.”

“But at the same time,” said Jayapal, “it’s important people understand how ubiquitous this is, and how much a part of our psyche it is taking up.”

She thought about why she had never shared the voice mails before.

“Why didn’t I?”

“Is it like, ‘Oh you’re supposed to take it?’”

“Or you’re not tough enough if you release it?”

These were questions the congresswoman couldn’t answer.

Instead, she asked, “Have we somehow conditioned ourselves to think this is what we should expect?”

READ MORE  Ukraine's Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba attends a news conference in Odesa, Ukraine, September 14, 2022. (photo: Umit Bektas/Reuters)

Ukraine's Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba attends a news conference in Odesa, Ukraine, September 14, 2022. (photo: Umit Bektas/Reuters)

The ministry argued that Russia had obtained its membership in the UN and Security Council illegally after the collapse of the Soviet Union, which had been a permanent member of the council.

“Russia has never gone through the legal procedure to be admitted to membership and therefore illegally occupies the seat of the USSR in the UN Security Council…Russia is an usurper of the Soviet Union’s seat in the UN Security Council,” reads the statement.

The Foreign Ministry said that Russia’s actions, such as military aggression against Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia, and Chechnya, are contrary to the concept of a “peace-loving” state, defined in the UN Charter as one of the main criteria for membership.

On the same day, Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba said Ukraine is looking to hold a peace summit by the end of February with the involvement of the United Nations and Secretary-General Antonio Guterres.

In an interview with the Associated Press news agency, Kuleba said that Ukraine will do whatever it can to win the war in 2023, adding that diplomacy always plays an important role.

Regarding the summit, the minister stressed that Russia could only be invited to such a gathering if the country faced a war crimes tribunal first.

A plan to initiate a summit to implement the Ukrainian peace formula in 2023 was announced by President Volodymyr Zelensky on Dec. 12.

In mid-November, he presented a 10-point peace plan that envisages preventing ecocide in Ukraine, punishing those responsible for war crimes, withdrawing all Russian troops from the territory of Ukraine, restoration of Ukraine’s territorial integrity, and the release of all prisoners of war and deportees. The proposals also call for ensuring energy security, food security, and nuclear safety.

The Kremlin dismissed the proposal by ruling out withdrawal from Ukraine by the end of 2022. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov said on Dec. 13 that Kyiv needs to accept new territorial “realities,” which include Moscow’s illegal claims of “annexation” of four Ukrainian regions – Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, Luhansk, and Kherson oblasts.

Also on Dec. 26, Putin claimed he was ready to “negotiate with everyone involved in this process about acceptable solutions,” according to the Russian state-controlled news agency TASS.

Both Ukraine and Western allies are skeptical about the Kremlin’s invitations for peace talks.

Ukraine has made it clear that it will not enter into talks with Russia unless the latter returns all occupied territories, including the Crimean Peninsula, which was illegally annexed by Moscow in 2014.

Last week, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said the Kremlin’s “invitations to negotiations” only aim to buy Russia time to prepare for a new offensive against Ukraine.

“Russia hopes to freeze the war to allow its forces to regroup, rearm and try to launch a renewed offensive,” he wrote in an op-ed for the Financial Times.

He added that most wars end with peace talks, but “what happens at the negotiating table is inextricably linked with what happens on the battlefield,” thus, Western countries should continue supporting Ukraine.

On the battlefield

Over 60% of the infrastructure in the city of Bakhmut in the eastern Donetsk Oblast, which has been the site of intense fighting, is partially or fully destroyed, Governor Pavlo Kyrylenko said on Dec. 26.

On the same day, Eastern Military Command spokesman Serhiy Cherevaty said that the Bakhmut and Avdiivka areas in Donetsk Oblast remain the sites of the heaviest hostilities at the current stage of the war. He reported that there were 28 episodes of fighting and 225 shellings from artillery and tanks in the Bakhmut area on Dec. 26 alone.

Zelensky described Bakhmut as “the hottest point” out of the entire 1,300-kilometer front line on Dec. 20.

A salt-mine city with a pre-war population of around 70,000 is one of Russia’s main targets, as seizing it could allow Russian forces to launch attacks on urban areas such as Kramatorsk and Sloviansk in Donetsk Oblast.

The General Staff of Ukraine’s Armed Forces said in an evening update on Dec. 26 that Russian troops are trying to improve their tactical positions in the directions of Kupiansk, Avdiivka, and Zaporizhzhia.

In Luhansk Oblast, Ukraine’s Armed Forces are “not far from” the city of Kreminna, and “the fighting is ongoing,” according to Luhansk Oblast Governor Serhii Haidai.

He reported that Ukrainian troops have been stationed within 20 kilometers of the city.

Kreminna lies 25 kilometers northwest of Sievierodonetsk, a major city in Luhansk Oblast which Russian troops occupied in June.

Over the past day, Ukraine’s rocket and artillery forces have hit four control points and six areas of concentration of Russian troops in the past 24 hours, according to the General Staff.

Meanwhile, Russian forces carried out 19 attacks with multiple launch rocket systems, the Ukrainian military said.

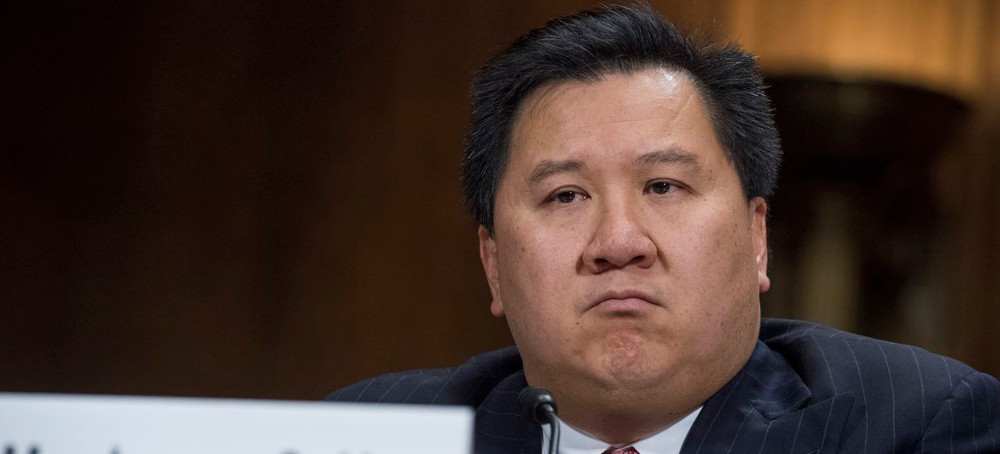

James C. Ho, judge for the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, testifies during his Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearing on November 15, 2017. (photo: Tom Williams/Roll Call)

James C. Ho, judge for the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, testifies during his Senate Judiciary Committee confirmation hearing on November 15, 2017. (photo: Tom Williams/Roll Call)

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is where law goes to die.

Taylor alleged that he was kept in this cell for four days, where he neither ate nor drank due to fears that the excrement, which was even packed inside the cell’s water faucet, would contaminate anything he consumed. Then, on the fifth day, he was moved to a bare, frigid cell with no toilet, water fountain, or bed. A clogged drain filled the new cell with choking ammonia films. With nowhere to relieve himself, Taylor held his urine for 24 hours before he could do so no longer. And then he had to sleep alone on the floor while covered in his own waste.

The Supreme Court eventually ruled 7–1 that Taylor’s lawsuit against the corrections officers who forced him to live in these conditions could move forward, and that lawsuit settled last February. But the Supreme Court had to intervene after an even more conservative court, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, attempted to shut down these claims against the prison guards.

A unanimous panel of three Fifth Circuit judges held that it was unclear whether the Constitution prevents prisoners from being forced to remain in “extremely dirty cells for only six days” — although, in what counts as an act of mercy in the Fifth Circuit, the panel did concede that “prisoners couldn’t be housed in cells teeming with human waste for months on end.”

This decision, in Taylor v. Stevens, is hardly aberrant behavior by the Fifth Circuit, which oversees federal litigation arising out of Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. The Fifth Circuit’s Taylor decision stands out for its casual cruelty, but its disregard for law, precedent, logic, and basic human decency is ordinary behavior in this court.

Dominated by partisans and ideologues — a dozen of the court’s 17 active judgeships are held by Republican appointees, half of whom are Trump judges — the Fifth Circuit is where law goes to die. And, because the Fifth Circuit oversees federal litigation arising out of Texas, whose federal trial courts have become a pipeline for far-right legal decisions, the Fifth Circuit’s judges frequently create havoc with national consequences.

The Fifth Circuit has, in recent months, declared an entire federal agency unconstitutional and stripped another of its authority to enforce federal laws protecting investors from fraud. It permitted Texas Republicans to effectively seize control of content moderation at social media sites like Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Less than a year ago, the Fifth Circuit forced the Navy to deploy sailors who defied an order to take the Covid vaccine, despite the Navy’s warning that a sick service member could sideline an entire vessel or force the military to conduct a dangerous mission to extract a Navy SEAL with Covid.

As Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote when the Supreme Court restored the military’s command over its own personnel, the Fifth Circuit’s approach wrongly inserted the courts “into the Navy’s chain of command, overriding military commanders’ professional military judgments.”

And this is just a small sample of the decisions the Fifth Circuit has handed down in 2022. Go back just a little further, and you’ll find things like a decision endangering the First Amendment right to protest, or another that seized control over much of the United States’ diplomatic relations with the nation of Mexico. In 2019, seven Fifth Circuit judges joined an opinion that, had it been embraced by the Supreme Court, could have triggered a global economic depression unlike any since the 1930s.

Its judges embrace embarrassing legal theories, and flirt with long discredited ideas — such as the since-overruled 1918 Supreme Court decision declaring federal child labor laws unconstitutional. They abuse litigants and even each other. During a 2011 oral argument, the Court’s then-chief judge, Edith Jones, told one of her few left-leaning colleagues to “shut up.”

And while the Fifth Circuit is so extreme that its decisions are often reversed even by the Supreme Court’s current, very conservative majority, its devil-may-care approach to the law can throw much of the government into chaos, and even destabilize our relations with foreign nations, before a higher authority steps in. Worse, the Fifth Circuit’s antics could very well be a harbinger for what the entire federal judiciary will become if Republicans get to replace more justices.

The median Fifth Circuit judge is very far to the right — more so than the Court’s current median justice, Brett Kavanaugh. But the typical Fifth Circuit judge would also be quite at home alongside a Republican stalwart like Justice Samuel Alito, or a more nihilistic justice like Neil Gorsuch.

How the Fifth Circuit became a far-right playground

Two generations ago, the Fifth Circuit was widely viewed as a heroic court by proponents of civil rights, handing down aggressive decisions calling for public school integration and protecting voting rights — even in the face of opposition from other, prominent judges.

Very soon after Brown v. Board of Education (1954) determined that racially segregated public schools violate the Constitution, a panel of federal judges in South Carolina handed down an influential opinion, in Briggs v. Elliott (1955), that effectively strangled Brown in its cradle. Brown, the court claimed in Briggs, “has not decided that the states must mix persons of different races in the schools or must require them to attend schools or must deprive them of the right of choosing the schools they attend.” To comply with Brown, Briggs suggested, a state must merely offer Black children the choice to attend white schools — and if those children choose to remain in segregated classrooms, that’s not a constitutional problem.

As a practical matter, these “freedom to choose” plans led to very little integration, in no small part because African American families knew full well what the Ku Klux Klan might do to them if they volunteered to send their children to a historically white school. Ten years after Briggs, the Fifth Circuit noted in United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education (1967), the South Carolina school system at the heart of the Briggs case was “still totally segregated.”

Jefferson County was authored by Judge John Minor Wisdom, arguably the greatest of the Fifth Circuit’s judges, whose name adorns the court’s building in New Orleans today. After watching Briggs’s approach fail Black children for 10 long years, Wisdom wrote a lengthy, statistics-laden opinion savaging Briggs and insisting that “the only school desegregation plan that meets constitutional standards is one that works.”

“The Brown case is misread and misapplied when it is construed simply to confer upon Negro pupils the right to be considered for admission to a white school,” Wisdom wrote. “The Constitution is both color blind and color conscious,” he wrote, anticipating modern-day attacks on affirmative action. It must be read “to prevent discrimination being perpetuated and to undo the effects of past discrimination.”

At the time, the Fifth Circuit’s jurisdiction extended over six Southern states, stretching from Texas to Florida (the court was split in half and three of these states were reassigned to a new Eleventh Circuit by a 1980 law), so the aggressive approach to desegregation laid out in Wisdom’s Jefferson County opinion bound many of the states where the need for public school integration was most urgent.

Beginning in the 1980s, however, Wisdom’s influence within his court began to fade. Republican President Ronald Reagan appointed a total of eight judges to the Fifth Circuit — one of whom was Edith Jones, a thirtysomething former general counsel to the Texas Republican Party. President George H.W. Bush added another four judges. The result was that, by 1991, Wisdom complained that his court’s approach to race in education was so harsh that it would even violate the separate-but-equal approach announced in the Supreme Court’s infamous Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) decision.

If any one decision captures the spirit of the post-Reagan, but pre-Trump Fifth Circuit, it’s that court’s decision in Burdine v. Johnson (2000). In that case, a man was convicted of murder and sentenced to die after his court-appointed lawyer slept through much of his trial. One witness recalled that the lawyer fell asleep as many as 10 times. Another testified that the lawyer “was asleep for long periods of time during the questioning of witnesses.”

And yet, a panel of Fifth Circuit judges that included Judge Jones initially voted to let this death sentence stand because it was unable to determine whether the lawyer “slept during the presentation of crucial, inculpatory evidence,” or merely through portions of the trial that the panel deemed unimportant. Eventually, the full Fifth Circuit reheard Burdine and held that the death row inmate at the heart of the case must be retried — but it did so over the dissents of five Fifth Circuit judges.

And the Fifth Circuit has only grown more conservative since these five judges determined that it was no big deal that a capital defendant’s lawyer couldn’t even remain awake throughout his trial.

Trump’s appointees turned the Fifth Circuit into a farce

When former President Donald Trump took office, the Fifth Circuit was already one of the most conservative courts in the country. It also had two vacancies due to a boneheaded decision by former Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Patrick Leahy (D-VT) to give Republican senators a veto power over anyone nominated to a federal judgeship in their home state — thus preventing President Barack Obama from filling these seats during his time in office.

To the first of these two seats, Trump appointed Don Willett, a libertarian provocateur known for speckling his opinions with the kind of platitudes that one might hear from a member of the John Birch Society, a member of the Tea Party, or a participant in the January 6 putsch. Sample quote: “Democracy is two wolves and a lamb voting on what to have for lunch. Liberty is a well-armed lamb contesting the vote.”

And then there was James Ho, the former law clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas who labeled abortion a “moral tragedy” in one of his first opinions as a judge. Ho’s very first opinion sought to implement a proposal he first announced in a 1997 op-ed to “abolish all restrictions on campaign finance.” The opinion declared that “big money in politics” was a “necessary consequence” of “big government in our lives.” It also claimed that our current government “would be unrecognizable to our Founders” because the Affordable Care Act exists.

Another Trump judge on the Fifth Circuit, Cory Wilson, published a series of columns in Mississippi newspapers that raise serious questions about his ability to apply the law impartially to Democrats and to LGBTQ Americans. Among other things, Wilson claimed that “intellectually honest Democrat[s]” are “very rare indeed.” He called President Obama a “fit-throwing teenager” because he opposed a Republican proposal to slash Medicaid funding and repeal Medicare and replace it with a voucher program. He wrote that “gay marriage is a pander to liberal interest groups and an attempt to cast Republicans as intolerant, uncaring and even bigoted.” And he also had a Twitter feed that often resembled Trump’s.

Another Trump judge on the Fifth Circuit, Kyle Duncan, spent much of his career as an anti-LGBTQ lawyer. He may be best known for an opinion he authored as a judge, which refused a transgender litigant’s request that Duncan use her proper pronouns.

Duncan also joined an opinion, authored by Trump-appointed Judge Kurt Engelhardt, which blocked a Biden administration rule requiring most workers to either get vaccinated against Covid-19 or take weekly Covid tests. The Supreme Court eventually struck this rule down under a legally dubious, judicially created legal doctrine called “major questions.”

But Engelhardt’s opinion makes this Supreme Court look sensible and moderate. Although federal law permits the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to issue emergency rules to protect workers from “exposure to substances or agents determined to be toxic or physically harmful,” Engelhardt made the extraordinary argument that the novel coronavirus — which has killed over a million Americans — does not qualify as a “substance or agent” that is “physically harmful.”

Nor did Engelhardt stop there. His most aggressive argument implies that the federal government’s power to regulate commerce does not extend to the workplace, which is the same argument the Supreme Court used in a discredited 1918 decision striking down federal child labor laws.

Trump, in other words, took a court that was already a reactionary outlier among the federal courts of appeal, and filled it with judges from the fringes of the legal profession. And those judges gleefully sow chaos throughout the law.

Why the Fifth Circuit in particular can cause so much chaos

One reason why the Fifth Circuit’s decline is so harmful to the nation as a whole is that it oversees federal litigation arising out of Texas.

That’s one part of a perfect storm: Texas’s Republican attorney general and other conservative litigants frequently bring challenges to Biden administration policies in Texas’s federal trial courts. And because those courts often permit plaintiffs to choose which judge will hear their lawsuits, these challenges frequently go before highly partisan judges who issue nationwide injunctions blocking that policy. And then those decisions, which frequently have glaring legal errors that would be obvious to many first-year law students, go to the Fifth Circuit.

This practice has been a particular thorn in the side of the Department of Homeland Security, as Texas has repeatedly obtained orders from Trump judges blocking the Biden administration’s immigration policies. One even forced the United States to change its diplomatic posture regarding Mexico.

One of the federal appeals’ courts most important roles is to keep a watchful eye over federal trial judges, and make sure they don’t issue disruptive, idiosyncratic decisions — or, at least, to make sure that those decisions don’t remain in effect for long. But the Fifth Circuit almost always operates like a rubber stamp for the Trumpiest judges, blessing even the most extreme decisions by trial judges who hope to sabotage Biden’s policies.

Just as often, the Fifth Circuit hands down decisions that seem to come out of nowhere, embracing legal theories that few lawyers have ever even heard of before, and that threaten to shut down much of the federal government and disrupt the nation’s economy. Consider, for example, Community Financial Services v. CFPB (2022), a decision by three Trump judges (Willett, Engelhardt, and Wilson), which declared the entire Consumer Financial Protection Bureau unconstitutional.

The Fifth Circuit’s opinion, by Wilson, claims that the agency is unlawful because of the unusual way that it is funded — rather than receiving an annual appropriation from Congress, the CFPB receives a portion of the funds raised by the Federal Reserve. Wilson claims that this funding structure “violates the Constitution’s structural separation of powers.”

But he’s just plain wrong about that, and his legal reasoning was explicitly rejected by the Supreme Court more than eight decades ago. Wilson relied on a provision of the Constitution stating that “no money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” But, as the Supreme Court held in Cincinnati Soap Co. v. United States (1937), this provision “means simply that no money can be paid out of the Treasury unless it has been appropriated by an act of Congress.”

Because there is an Act of Congress creating the CFPB and its funding structure, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, the CFPB is constitutional. Wilson’s opinion relies on a fantasy constitution that does not exist.

Three years before its CFPB decision, seven Fifth Circuit judges signed onto another opinion that would have destroyed another entire federal agency — and potentially triggered a worldwide economic depression in the process.

The Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) was created in 2008 to deal with the mortgage crisis that triggered a historic recession, and that very well could have led to a second Great Depression if the FHFA had not acted. Over the course of the next several years, the FHFA presided over tens of billions of dollars worth of transactions intended to prop up the US mortgage system and ensure that the American housing market did not collapse.

About a dozen years after the FHFA was created, however, the Supreme Court determined that federal agencies may not be led by a single individual who cannot be fired at will by the president. By law, the FHFA director enjoyed some protections against being fired, and there’s no question that this decision required her to be stripped of these protections.

But in Collins v. Mnuchin (2019), seven Fifth Circuit judges joined an opinion by Judge Willett, which argued that this minor constitutional violation — a violation the Supreme Court didn’t even recognize until years after the FHFA was established — renders everything the FHFA has ever done invalid. When a plaintiff who is injured in any way by one of the FHFA’s actions files a federal lawsuit challenging that action, Willett claimed, the “action must be set aside.”

The immediate impact of Willett’s opinion, had it taken effect, would have been to force the FHFA to unravel more than $124 billion worth of transactions it undertook to rescue the US housing market — more than the gross domestic product of the entire nation of Ecuador. But Willett’s opinion would have gone even further than that, because it would have permitted suits invalidating literally anything the FHFA had ever done since its creation in 2008.

In any event, the Collins case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court, where the justices voted 8 to 1 to reject Willett’s approach. Only Justice Neil Gorsuch thought that toying with an economic depression was a good idea.

But even when the Supreme Court does step in, eventually, to reverse the Fifth Circuit, it often drags its feet. When a notoriously partisan federal trial judge ordered the Biden administration to reinstate much of Trump’s border policy, and the Fifth Circuit rubber stamped that decision, the Supreme Court waited 11 months to intervene — leaving the lower court’s decisions imposing a defeated president’s policies on the nation in place the entire time. A similar drama played out over immigration enforcement.

The result is that the Fifth Circuit, though it does not have the final say, often decides what US policy should be for months at a time. And that’s assuming that the Supreme Court actually reverses the Fifth Circuit — sometimes the Fifth Circuit’s most legally dubious decisions are embraced by a Supreme Court dominated by Republican appointees.

If the Fifth Circuit behaves this badly when powerful litigants are before them, imagine what it is like for the powerless

One of the few good things that can be said about the Fifth Circuit is that it does not have the last word about what the law says. When its judges strike down a federal law, or attempt to destroy an entire federal agency, or declare a national policy unconstitutional, the Supreme Court almost always steps up to hear that case. And the justices do frequently reverse the Fifth Circuit’s most outlandish decisions — even if they take their sweet time before they do so.

But the Supreme Court only hears a tiny percentage of the cases decided by federal appeals courts, and it almost never hears cases brought by extraordinarily vulnerable litigants like Trent Taylor. Indeed, it hears these cases so infrequently that, when the Court decided to intervene on Taylor’s behalf, Justice Samuel Alito wrote a brief opinion complaining that Taylor’s case “which turns entirely on an interpretation of the record in one particular case, is a quintessential example of the kind that we almost never review.”

The Fifth Circuit hears a steady diet of ordinary immigration cases, which will often decide whether an individual immigrant can remain with their family in the United States or whether they must be deported to a nation they may barely know, or where they may fear for their physical safety. These cases are now heard by judges like Andrew Oldham, Trump’s sixth appointment to the Fifth Circuit, who spent much of his time both on and off the bench seeking to make federal immigration policies harsher to immigrants.

Similarly, the court hears a steady diet of employment discrimination cases. These cases are heard by judges like Edith Jones, who dissented in a 1989 case ruling in favor of Susan Waltman, a woman who experienced the kind of sexual harassment that would make any normal person’s skin crawl:

During the summer of 1984, an IPCO employee told a truck driver that Waltman was a whore and that she would get hurt if she did not keep her mouth shut. Later, in the Fall of 1984, several other incidents occurred. A Brown and Root employee, who was working at the mill, grabbed Waltman’s arms while she was carrying a vial of hot liquid; another Brown and Root worker then stuck his tongue in her ear. In a separate incident, an IPCO employee told Waltman he would cut off her breast and shove it down her throat. The same employee later dangled Waltman over a stairwell, more than thirty feet from the floor. In November 1984, one employee pinched Waltman’s breasts. In another incident, a co-worker grabbed Waltman’s thigh.

Jones claimed that Waltman’s employer “did not have actual or constructive notice that Waltman was subjected to a pervasively abusive and hostile work environment,” but Waltman complained multiple times to her supervisors, met with senior managers about the harassment she faced, and announced her intention to resign after a shift meeting where her coworkers made comments that “women provoke sexual harassment by wearing tight jeans” in front of her supervisor.

And then, after determining that these conditions do not amount to actionable sexual harassment, Jones spent the next 33 years hearing other cases brought by workers alleging employment discrimination.

The Fifth Circuit has created a void in the law, where judges ignore horrific violations in between writing opinions claiming that entire federal agencies are unconstitutional. And, barring legislation adding additional seats to the court, things are unlikely to get better anytime soon. Currently, Republican appointees hold 12 of the 17 active judgeships on this benighted court — and nearly all of them are ideologically similar to Jones.

That said, there are reforms that Congress or the Supreme Court could implement, which would diminish both the Fifth Circuit’s power and the power of litigants to channel political lawsuits to highly ideological judges. Congress, for example, may strip the Fifth Circuit of its jurisdiction over certain cases, or require certain suits to be filed in a federal court that is not located in the Fifth Circuit. It could also add seats to the court, which would then be filled by President Biden.

A less radical reform, proposed by former Fifth Circuit Judge Gregg Costa, would prevent litigants like the Texas AG’s office from handpicking judges who are likely to rule in their favor — and whose decisions are equally likely to be affirmed by the Fifth Circuit. Costa proposed having all lawsuits seeking a nationwide injunction against a federal law or policy be heard by three-judge panels, rather than a single judge chosen by the plaintiff. These panels’ decisions would then appeal directly to the Supreme Court, bypassing the Fifth Circuit (although a single Fifth Circuit judge might sit on some of these panels).

Realistically, however, systemic reforms to the problem of judge-shopping — and to the problem of a lawless court of appeals — are unlikely to happen anytime soon. The House of Representatives will soon be controlled by Republicans, who are unlikely to support legislation that reduces the power of their partisan allies on the bench. And the Supreme Court has six justices appointed by Republican presidents.

And so the Fifth Circuit will continue to hand down its decrees, confident that no one with the power to stop them is likely to do so.

READ MORE  In this courtroom drawing, from left, Brandon Caserta with his attorney Michael Darragh Hills, defendants Adam Fox, center, and Ty Garbin appear during a hearing in federal court in Grand Rapids, Mich., on Oct. 16, 2020, in a case over a plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. (photo: Jerry Lemenu/AP)

In this courtroom drawing, from left, Brandon Caserta with his attorney Michael Darragh Hills, defendants Adam Fox, center, and Ty Garbin appear during a hearing in federal court in Grand Rapids, Mich., on Oct. 16, 2020, in a case over a plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. (photo: Jerry Lemenu/AP)

Adam Fox was convicted in August of conspiracy to commit kidnapping and to use a weapon of mass destruction.

Adam Fox, 39, was convicted in August of conspiracy to commit kidnapping and to use a weapon of mass destruction to attack Whitmer, who had drawn the ire of far-right groups for her efforts to curb the spread of Covid-19 in 2020.

Jurors in April failed to come to verdicts against Fox and co-defendant Barry Croft, forcing a judge to declare a mistrial before a second trial proved decisive.

U.S. District Judge Robert Jonker questioned whether Fox was a true "natural leader" of the plot, worthy of a life sentence.

"I don't think life is needed to achieve the important public deterrent factors," Jonker said in Grand Rapids, explaining the 192-month sentence.

While a terrorism enhancement set up Fox for a possible life term, Jonker said that harshest sentence isn’t automatic and that he had to carefully consider other factors.

Jonker said he leaned heavily on a 2018-19 Northern California case where U.S. District Judge Charles Breyer, brother of retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, sentenced ISIS sympathizer Amer Alhaggagi to 188 months in prison, more than 15 years short of the 33 years sought by prosecutors.

“You have to calibrate, as judges, the overall seriousness of wrongdoing and the overall seriousness of the defendant’s history," Jonker said.

“I see nothing in the record ... nothing that makes me think he’s (Fox) a natural leader and nothing that makes me think he’s the kind of person that anybody involved in this group was naturally going to follow.”

Assistant U.S. Attorney Nils Kessler had said Fox was out to spark an all-out war and needed to be put away for life.

“They wanted a second Civil War or a revolution,” Kessler told the court on Tuesday. "They wanted to ruin everything for everybody."

Kessler warned that Fox will still be a dangerous man when he someday walks free.

“The problem is this defendant, he’s going to go into jail and probably emerge more radicalized than when he went in and will remain a danger to the public, your honor," the prosecutor said.

The plot was hatched in response to Whitmer's actions during the start of the pandemic in 2020 when she ordered various lockdowns aimed at curbing the spread of Covid.

Far-right groups blasted Whitmer, and then-President Donald Trump appeared to back that opposition in an all-caps tweet.

Defense attorney Christopher Gibbons argued on Tuesday that a life sentence would have been too much.

"That overstates the reality of the conduct that has been alleged and that was actually accomplished by Adam Fox in summer of 2020," Gibbons said.

Fox declined an opportunity to address the court: "I’m satisfied with what my lawyer said."

Croft is scheduled to be sentenced on Wednesday.

A representative for Whitmer could not be immediately reached for comment on Tuesday.

READ MORE  Pneumatic tube operator is among the sedentary, unskilled jobs on a list the Social Security Administration uses when considering disability claims, even though the job barely exists in the modern economy. Four of five occupations in the Dictionary of Occupational Titles were last updated in 1977. (photo: Bettman Archive)

Pneumatic tube operator is among the sedentary, unskilled jobs on a list the Social Security Administration uses when considering disability claims, even though the job barely exists in the modern economy. Four of five occupations in the Dictionary of Occupational Titles were last updated in 1977. (photo: Bettman Archive)

Despite spending at least $250 million to modernize its vocational system, the agency still relies on 45-year-old job titles to deny thousands of claims a year.

There was just one final step: A vocational expert hired by the Social Security Administration had to tell the judge if there was any work Heard could still do despite his condition. Heard was stunned as the expert canvassed his computer and announced his findings: He could find work as a nut sorter, a dowel inspector or an egg processor — jobs that virtually no longer exist in the United States.

“Whatever it is that does those things, machines do it now,” said Heard, who lives on food stamps and a small stipend from his parents in a subsidized apartment in Tullahoma, Tenn. “Honestly, if they could see my shaking, they would see I couldn’t sort any nuts. I’d spill them all over the floor.”

He was still hopeful the administrative law judge hearing his claim for $1,300 to $1,700 per month in benefits had understood his limitations.

But while the judge agreed that Heard had multiple, severe impairments, he denied him benefits, writing that he had “job opportunities” in three occupations that are nearly obsolete and agreeing with the expert’s dubious claim that 130,000 positions were still available sorting nuts, inspecting dowels and processing eggs.

Every year, thousands of claimants like Heard find themselves blocked at this crucial last step in the arduous process of applying for disability benefits, thanks to labor market data that was last updated 45 years ago.

The jobs are spelled out in an exhaustive publication known as the Dictionary of Occupational Titles. The vast majority of the 12,700 entries were last updated in 1977. The Department of Labor, which originally compiled the index, abandoned it 31 years ago in a sign of the economy’s shift from blue-collar manufacturing to information and services.

Social Security, though, still relies on it at the final stage when a claim is reviewed. The government, using strict vocational rules, assesses someone’s capacity to work and if jobs exist “in significant numbers” that they could still do. The dictionary remains the backbone of a $200 billion disability system that provides benefits to 15 million people.

It lists 137 unskilled, sedentary jobs — jobs that most closely match the skills and limitations of those who apply for disability benefits. But in reality, most of these occupations were offshored, outsourced, and shifted to skilled work decades ago. Many have disappeared altogether.

Since the 1990s, Social Security officials have deliberated over how to revise the list of occupations to reflect jobs that actually exist in the modern economy, according to audits and interviews. For the last 14 years, the agency has promised courts, claimants, government watchdogs and Congress that a new, state-of-the art system representing the characteristics of modern work would soon be available to improve the quality of its 2 million disability decisions per year.

But after spending at least $250 million since 2012 to build a directory of 21st century jobs, an internal fact sheet shows, Social Security is not using it, leaving antiquated vocational rules in place to determine whether disabled claimants win or lose. Social Security has estimated that the project’s initial cost will reach about $300 million, audits show.

“It’s a great injustice to these people,” said Kevin Liebkemann, a New Jersey attorney who trains disability attorneys and has written extensively on Social Security’s use of vocational data. “We’re relying on job information from the 1970s to say thumbs-up or thumbs-down to people who desperately need benefits. It’s horrifying.”

Obsolete jobs

In 2022, it is not easy to find a nut sorter (code 521.687-086) in the national economy who “observes nut meats” on a conveyor belt and picks out broken, shriveled, or wormy nuts. How many workers in America inspect dowel pins (code 669.687-014), searching for flaws from square ends to splits, then discard them by hand? And even if Heard were qualified to remove virus-bearing fluid from fertile chicken eggs for use in vaccines by sawing off the end of an egg and removing its fetal membrane, that work is largely automated today.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics, which is part of the Labor Department, has built a new, interactive system for Social Security using a national sample of 60,000 employers and 440 occupations covering 95 percent of the economy. But Social Security still has not instructed its staff to use it.

“They regularly tell us they plan on using the data,” Hilery Simpson, the labor bureau’s associate commissioner for compensation and working conditions, said of Social Security officials. The data collection and estimation “have gone through extensive testing and use the best-in-class statistical methods,” he said. The survey is available to the public on the labor bureau’s website.

Social Security has not explained why it has yet to implement the labor bureau survey.

Acting Social Security commissioner Kilolo Kijakazi declined to be interviewed. In a statement, she said, “To date, the best available source for occupational information has been the Dictionary of Occupational Titles. We have enlisted vocational experts to provide more detailed and current information about the jobs available in the national economy, while we continue to work on creating our own occupational data source informed by [the Bureau of Labor Statistics] that best reflects the current job market.”

A spokeswoman for the agency declined to answer questions about a timeline for putting the modern data into use.

Social Security’s delays in updating the database of job titles are rooted in conflicting political considerations, shifting leadership, and the drift that can bedevil large federal projects, according to current and former officials, auditors and disability advocates.

A modern list of occupations would create new winners and losers in the application process — posing political sensitivities for a program that has long drawn judgment that the government is either too generous or not generous enough. Over two decades, Social Security has been led by six acting commissioners and just three Senate-confirmed leaders, leaving power vacuums at the top that can delay costly projects. Many advocates believe the agency is motivated to delay the project so it can deny more claimants benefits.

“The scandal is that everybody wants this data discussed in terms of who will be hurt and who will be helped,” said David Weaver, a former Social Security associate commissioner who helped lead the early effort to modernize. “But a lot of money has been spent. You have the gold-standard of federal data, and Social Security is not producing anything.”

Congress continues to approve more than $30 million per year for the survey of modern jobs without asking hard questions about why the data sits unused, congressional aides and former Social Security officials said.

Senate Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) called on Social Security to move forward.

“Occupational definitions used by the federal government need to reflect the reality of the work Americans are doing today,” Wyden said in a statement. He warned that data on modern jobs “must be handled with care to ensure that nobody is wrongly denied their earned benefits.”

Federal courts, meanwhile, keep sending denied claims back to Social Security to redo its decisions, raising alarms that the government is shortchanging disabled Americans with arbitrary judgments that put it at legal risk.

“Does anyone use a typewriter anymore?” Richard Posner, a judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit, asked in a 2015 decision reversing an administrative law judge’s denial of benefits to a disabled man the judge claimed could work as an “addresser” — one who “addresses cards” by hand or typewriter. Posner called a vocational expert’s claim that 200,000 such jobs still exist today a “fabrication.”

Others have not been as fortunate. Few claimants without attorneys are aware that the jobs used to deny them benefits have been pulled from obscurity. And many lawyers representing them lack the expertise and resources to take a case to federal court, say advocates, vocational experts and judges who rule in these cases.

“Every day we made decisions we don’t necessarily agree with,” said George Gaffaney, an administrative law judge in the Chicago area. “It’s troubling.”

A need to modernize

The Dictionary of Occupational Titles was first published in 1938 to help a country pulling out of the Great Depression match workers with jobs. Each entry contained the time to train for the job, the aptitude required, physical demands, the work performed — but not any recognition of which jobs match with the cognitive impairments common among the disabled today.

With its benefit decisions hinging largely on whether someone’s impairment limits them from doing past jobs or other jobs, Social Security needed a resource with accurate information about available work. But by the time the Labor Department retired the red hardcover book three decades ago, it was already stocked with jobs that, if not already gone, were quickly vanishing from the economy: elevator operators, thaw-shed heater tenders, window shade ring sewers. And it did not include a host of emerging information-economy jobs, from Web designers to employment recruiters.

Inside Social Security, the publication’s 1991 demise set off a decade of hand-wringing. Workgroups, panels and committees of experts formed — all while the agency continued to rely on the outdated jobs list. By 1998, the Labor Department had developed a new database of jobs and what was required to do them. Social Security brought in another round of experts to determine whether that system, dubbed O*NET, could serve its disability program.

It took until 2008 — a full decade — to reach consensus: the agency needed to develop its own vocational information because existing federal data lacked enough characteristics of jobs disabled people could do. So in 2012 Social Security signed a contract with the Bureau of Labor Statistics to design a modern system that would help make accurate disability determinations.

The same year, the Government Accountability Office began questioning the project’s cost estimates and schedule. After three years of tests, field economists began their surveys in 2015. When that data was delayed, government watchdogs began warning that the project was in danger of becoming a case study in the challenges of large federal investments.

In 2018, the agency’s inspector general wrote in an audit, “It remains crucial that [Social Security] leadership commit to ensuring appeal applications receive fair and consistent treatment.” In response, a Social Security official set a target of fiscal 2020 to put the modern data into use and wrote, “we continue to work diligently to avoid delays in its implementation.”

The labor bureau now says it will finish a second wave of data collection next year. A third is planned.

“We thought we could do it in 10 years. It might take 20 years,” said Byron Haskins, who worked on the project as a branch chief from 2010 to 2016. “In the meantime, we’re not standing on solid ground on these decisions.”

When New York art collector and apparel company investor Andrew Saul was confirmed as President Donald Trump’s Social Security administrator in June 2019, his team drew up plans to start using the modern jobs data, concluding that disabled people, particularly older Americans, could learn new skills in an economy with more sedentary, skilled jobs. The new survey could tighten eligibility for benefits, Saul believed — a White House priority.

“It was going to make the system fairer,” Saul said in an interview “People who deserved disability would get it, and those who didn’t would not.”

But the plan set off a furor among advocates, who opposed a provision that would have made it harder for older workers to qualify for benefits. The Biden administration quickly shelved it and the president fired Saul in 2021.

Old data

Even so, advocates and opponents agree on one thing: A disability system that relies on obsolete jobs to decide claims is gambling with taxpayers and with the courts.

“It’s never really been blessed by Social Security,” said David Camp, president of the National Organization of Social Security Claimants’ Representatives, reflecting the view of many advocates. “The agency won’t take the step to clean up the system because they know we’ll win more cases.”

Mark Warshawsky, deputy commissioner for retirement and disability policy under Saul, described the antiquated vocational policy as “an arbitrary system.”

“How hard it is for the federal government to make change?” he asked. “That’s not a political thing. Spending almost $300 million with nothing to show for it is embarrassing.”

The current system is leading thousands of disability claims per year to be denied that would otherwise have a good chance of approval, data suggests. The inspector general’s 2018 audit showed that from fiscal 2013 through 2017, occupational information was used to decide more than half of all initial claims and in four in five decisions at the hearing level when decisions are appealed. The data does not show if it was the deciding factor.

But a 2011 study commissioned by Social Security found the 11 jobs most commonly cited by disability examiners when denying benefits. The top job was addresser, used in almost 10 percent of denials. Twelve years later, little has changed, advocates say.

Estimates by Social Security’s experts of how many of these outdated jobs remain in the economy are also widely off the mark, courts have found.

The U.S. Supreme Court held in 2019 that Social Security judges could uphold agency decisions even when vocational experts refuse to provide data on how they come up with job numbers. But the decision led to a blistering dissent from Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, who cited dubious expert claims that 120,000 “sorter” and 240,000 “bench assembler” jobs are available to the disabled without clear evidence.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit noted a similar problem while overturning a Social Security judge’s denial of benefits to a Wisconsin man.

“All three judges on this panel, assisted by very talented law clerks, read the transcript of the [vocational expert’s] testimony multiple times,” the court wrote. “And yet nobody can explain with coherence or confidence what the [vocational expert] did to arrive at her job-numbers estimate … There has to be a better way.”

The expert claims can be equally baffling to claimants.

At his hearing before an administrative law judge in Pennsauken, N.J., in July 2019, Sean Dooley described the chronic pain and limited stamina from diabetes, thyroid issues and degenerative disk disease that had kept him from working as a jewelry salesman for three years.

His mother testified that at 400 pounds, her son struggled to sit, stand, bend over and lift. Yet a vocational expert said Dooley could work as an order clerk, an addresser or a call-out operator — a job he had never heard of. An expert whose software is used by many vocational experts has calculated that 2,000 addressers are left in the U.S., 2,060 call-out operators who compile credit information and 424 order clerks.

In a written decision three months later, Judge Lisa Hibner Olson denied Dooley benefits, overruling his lawyer’s arguments that the jobs were obsolete.

“It was like I’m hit with a torpedo,” recalled Dooley, 46, who is living on his mother’s meager retirement savings in his sister’s garage in Pennsville, N.J. “With these goofy jobs, there was no way they were ever going to approve me. If I could work, I would be working.”

Dooley’s denial was overturned by a U.S. district court and remanded to the same Social Security judge, who has scheduled a new hearing for January.

The problem is not limited to appeals heard before judges. State offices that first decide disability claims place blame for a historic backlog exceeding 1 million cases in part on the obsolete jobs system, which requires expertise most do not have.

“We’ve heard the message from Social Security, ‘We’re working on vocational policy changes,’ for 10 years,” said Jacki Russell, director of Disability Determination Services in North Carolina and president of the National Council of Disability Determination Directors. “ ‘It’s very sensitive,’ they say. Meanwhile, we’re over here trying to make the best decisions we can with a massive backlog.” Russell’s office of 600 employees has just two vocational experts.