The July Fundraiser Starts Tomorrow, Early Urgency

Funding was way down in June. We can’t sustain another month like that. Funding has to be a top priority in July. We start tomorrow Tuesday the 5th.

This is a challenge we, all of us, must meet if RSN is to remain strong, and we have to meet it now.

RSN Needs you.

Marc Ash

Founder, Reader Supported News

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

ALSO SEE: Who Are the Farc?

Viktor Bout, 55, is a former Soviet military translator who became an international air transport figure after the fall of communism. Bout is currently serving a 25-year sentence at a medium-security prison in Illinois for conspiring to kill U.S. nationals and selling weapons to the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

The Kremlin has long pushed for Bout’s release, calling his conviction “unlawful.” And in recent weeks, media reports in Russia have hinted that he could be swapped for WBNA star Brittney Griner and former U.S. Marine Paul Whelan.

On Friday, Griner appeared in a Russian court to face drug charges stemming from her arrest at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo International Airport in February. Whelan was arrested and charged with spying in 2018 — and has called the trial politically motivated.

U.S. officials have declined to say whether the Biden administration is seeking a prisoner swap involving Griner and Whelan. In April, another U.S. prisoner held in Moscow — former Marine Trevor Reed — was released in exchange for a Russian convicted in the United States.

Many, including Bout’s own lawyer in the United States, say he would have to be released for Griner and Whelan to be allowed back to the United States.

Bout’s lawyer in the United States, Steve Zissou, says what Moscow wants is “obvious.”

“All that remains is for the U.S. government to have the courage to admit the obvious — get what we can for Viktor Bout,” Zissou said. “The alternative should be obvious — no Americans will be exchanged unless Viktor Bout is sent home along with them.”

What led to Bout’s arrest?

Bout was arrested in Thailand in 2008 in a sting operation after spending years dodging international arrest warrants and asset freezes.

“Today, one of the world’s most prolific arms dealers is being held accountable for his sordid past,” Attorney General Eric Holder said when he was convicted in New York in 2011.

The focus of the trial in Manhattan was Bout’s role in supplying weapons to FARC, a Marxist-Leninist guerrilla group that staged a long-running insurgency in Colombia. The United States, which worked with Thai authorities to apprehend Bout, said these weapons were intended to kill Americans.

But Bout had an even longer history of weapons dealing in some of the most dangerous and impoverished places in the world. His relationship in the 1990s with the Taliban led the Los Angeles Times to profile him in 2002, quoting a former U.S. government official who described him as the “Donald Trump or Bill Gates” of arms trafficking. He was also known to have links to Liberia’s Charles Taylor and Libya’s Moammar Gaddafi.

Why would Moscow care so much about him?

Bout himself has denied the charges against him, telling The Washington Post in 2002 that he was simply a man in the “air transportation business” and, presciently, that the accusations against him sounded like something out of a “Hollywood action film.”

And publicly at least, Russian officials have maintained that Bout was an entrepreneur who was unfairly targeted for political reasons. He has become something of a cause celebre in Russia, with government buildings in Moscow exhibiting his prison-made artworks last year.

Zissou said that much of the deterioration in U.S.-Russia relations could be tied to Bout’s case.

“The United States government set out to make a case against him for crimes that could be charged and prosecuted in an American court, and so they lured him into a sting operation,” Zissou said. “This targeting of one of its citizens is seen in Russia as a direct attack on its sovereignty.”

But outsiders have long suggested that Bout had ties to the Russian government that enabled him to gain a foothold in the international arms smuggling world.

David Whelan, the brother of Paul Whelan, said it was “understandable, if disappointing” that the focus was on Bout.

“There are hundreds of Russian prisoners held by the Bureau of Prisons and, if the U.S. decided to engage in a prisoner swap, many more names that might be palatable,” David Whelan said, pointing to one — Roman Seleznev, who has been imprisoned in the United States since 2011 on charges related to hacking and fraud — as another prisoner the Russian government has asked for.

But Russian journalist Andrei Soldatov said that even after all these years, Russia still seemed to care strongly about Bout’s case. He wasn’t just a hacker that was used occasionally by Russian intelligence services like the FSB or the GRU, “he was really important for military intelligence,” Soldatov wrote in an email.

Plus, “he kept his cool in prison [and] never exposed anything to the Americans, as far as I can tell,” Soldatov said.

What is his link to Americans arrested in Russia?

On paper, there is no link.

Indeed, there is little comparison between the enormous accusations against Bout and the minor charges that Griner faces.

Two-time U.S. Olympic gold medalist Griner, whose trial began on trial Friday, was arrested over 4 months ago on charges of possessing cannabis oil while returning to play for a Russian team.

While Whelan was arrested three years prior on espionage charges, his family and friends have said it was inconceivable that the charges are true. In 2020, U.S. officials said that his conviction was a “mockery of justice.”

But family and supporters of both Griner and Whelan have said that they hope a deal can be struck with Moscow that would see the two U.S. citizens released in exchange for Bout. And they have good reason to believe a deal is possible.

In April, the U.S. government agreed to a prisoner swap that saw former Marine Trevor Reed returned from Russia in exchange for Konstantin Yaroshenko, a Russian pilot serving a 20-year prison sentence in Connecticut for drug trafficking.

Though such prisoner swaps between Washington and Moscow are unusual, they are not unprecedented. In 1986, detained American journalist Nicholas Daniloff was swapped for Soviet physicist Gennadi Zakharov. In more recent years, the United States has exchanged prisoners with Iran.

David Whelan said his family was not aware of any discussions about a swap but that they did not expect to be provided information like that anyway.

“It’s also our understanding that there are obstacles within the U.S. government for any prisoner exchanges to happen, obstacles that only President Biden could surmount,” he said.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said Sunday that he had “no higher priority than making sure that Americans who are being illegally detained in one way or another around the world come home.”

Bout’s lawyer, Zissou, said that he had not had any contact from the State Department about the case and that the families of Griner and Whelan had been advised not to talk to him.

He said that if a swap does not happen, he plans to file a motion for a reduction of his sentence to time served — as is commonly known as compassionate release. Even if that is denied, Bout could probably be released to an immigration facility 12 months before the end of his term.

That means he could be home in as little as five years, Zissou said.

David Whelan said the focus on Bout underscores how Russia controls the “context of wrongful detention of Americans.”

“It is time for the U.S. government to have a solution to deter them and to take control of the problem. Otherwise, it will always be responding — in public, if not in reality — to Russia’s most outrageous demands,” David Whelan added.

Mohammed bin Salman at an official ceremony in Ankara, Turkey, in June. (photo: AFP/Getty Images)

Mohammed bin Salman at an official ceremony in Ankara, Turkey, in June. (photo: AFP/Getty Images)

John Bates, a district court judge, gave the US government until 1 August to declare its interests in the civil case or give the court notice that it has no view on the matter.

The administration’s decision could have a profound effect on the civil case and comes as Joe Biden is facing criticism for abandoning a campaign promise to turn Saudi Arabia into a “pariah”.

The US president is due to meet the heir apparent to the Saudi throne later this month when he makes his first trip to Riyadh since entering the White House.

The civil complaint against Prince Mohammed, which was filed by Cengiz in the federal district court of Washington DC in October 2020, alleges that he and other Saudi officials acted in a “conspiracy and with premeditation” when Saudi agents kidnapped, bound, drugged, tortured and killed Khashoggi inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018.

Khashoggi, a former Saudi insider who had fled the kingdom and was a resident of Virginia, was a vocal critic of the young crown prince and was actively seeking to counter Saudi online propaganda at the time when he was killed.

After years of inaction against Prince Mohammed by Donald Trump, who was president when Khashoggi was killed, the Biden administration moved to release an unclassified US intelligence report in 2021, shortly after Biden entered the White House, that concluded Prince Mohammed was likely to have ordered the murder of Khashoggi.

At the time the report was released, the Saudi foreign ministry said the kingdom’s government “categorically rejects what is stated in the report provided to Congress”.

While Saudi Arabia said it held a trial against the hit squad responsible for the grisly murder, the proceeding was widely condemned as a sham, and some of the most senior members of the team have been sighted in a state security compound in Riyadh.

Other possible avenues of justice have been stymied for political reasons. A Turkish prosecutor in March ended a long-running trial in absentia against Khashoggi’s killers, in a move that was seen as part of the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s attempts to improve relations with Prince Mohammed.

The Saudi prince has taken responsibility for the murder on behalf of the Saudi government but has denied any personal involvement in planning the assassination.

For supporters of Cengiz, who has been an outspoken advocate for justice for Khashoggi’s murder, any move by the US government to call for the crown prince to be granted sovereign immunity in the case would represent a betrayal of Biden’s promise to hold Saudi Arabia accountable.

“It would be preposterous and unprecedented for the administration to protect him. It would be the final nail in the coffin for attempts to hold Khashoggi’s murderers accountable,” said Abdullah Alaoudh, the research director of Dawn, a non-profit that promotes democracy in the Middle East that was founded by Khashoggi and a co-plaintiff on the case against the crown prince.

Judge Bates said in an order released on Friday that he would hold a hearing on 31 August after motions to dismiss the civil case by Prince Mohammed and others.

The motions to dismiss the civil case rest on claims by Prince Mohammed’s lawyers that the DC court lacks jurisdiction over the crown prince.

“In the court’s view, some of the grounds for dismissal advanced by defendants might implicate the interests of the United States; moreover, the court’s resolution of defendants’ motions might be aided by knowledge of the United States’ views,” Bates said.

The judge said he was specifically inviting the US government to submit a statement of interest regarding the applicability of so-called act of state doctrine, which states that the US should refrain from examining another foreign government’s actions within its courts; the interaction of that doctrine with a 1991 law that gives Americans and non-citizens the right to bring legal claims in the US of torture and extrajudicial killings committed in foreign countries; the applicability of the head of state immunity in this case; and the US view of whether Saudi Arabia’s sovereign interests could be impaired if the case were to proceed.

Agnès Callamard, the head of Amnesty International, who investigated Khashoggi’s murder in her previous role as UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial killings, said it was “laughable” that Prince Mohammed, whom she called “an almost-sovereign”, could benefit from head of state immunity after the US itself had concluded publicly that he most likely approved the operation to kill Khashoggi.

Noting that Prince Mohammed was not king, she added: “MBS [as the crown prince is known] is not the ruler of Saudi Arabia and the US should not recognise him as head of state. Doing so would grant him an authority and legitimacy he certainly does not deserve and hopefully will never receive.”

Cengiz could not immediately be reached for comment. The Saudi embassy in Washington was not available for comment.

The U.S. Supreme Court is seen on September 02, 2021 in Washington, DC. (photo: Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

The U.S. Supreme Court is seen on September 02, 2021 in Washington, DC. (photo: Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images)

The president and Congress can check SCOTUS' power when they believe the justices have exceeded their mandate. This might be the best way to save the court from itself.

It was a remarkable observation. Sotomayor’s primary intent was to argue that rights and prerogatives need not be explicitly delineated in the Constitution for them to exist. The right to privacy — more specifically, the right to terminate a pregnancy — does not appear anywhere in the document, but neither does the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review. Both exist by strong implication.

It’s an observation worth revisiting. After issuing a wave of hotly contested, and in some cases deeply unpopular, decisions, the Supreme Court has emerged in recent weeks as a formidable —and perhaps the most formidable — branch of the federal government. Six conservative justices, enjoying life tenure on the bench, are fundamentally reshaping the very meaning of citizenship. Their power to do so is seemingly absolute and unchecked.

How did we get here?

Liberal critics of today’s judicial activism are right when they note that the Supreme Court essentially arrogated to itself the right of judicial review — the right to declare legislative and executive actions unconstitutional — in 1803, in the case of Marbury v. Madison. There is nothing in the Constitution that confers this power upon the only unelected branch of government. But it is equally true that many of the Constitution’s framers and original proponents intended or at least believed the court would enjoy that prerogative. If context matters — and liberals normally insist that it does — the court is the frontline arbiter of what is, and isn’t, constitutional.

But that doesn’t make the court more powerful than the executive and legislative branches. Acting in concert, the president and Congress may shape both the size and purview of the court. They can declare individual legislative measures or entire topics beyond their scope of review. It’s happened before, notably in 1868, when Congress passed legislation stripping the Supreme Court of its jurisdiction over cases related to federal writs of habeas corpus. In the majority decision, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase acknowledged that the court’s jurisdiction was subject to congressional limitation. Subsequent justices, over the past century, have acknowledged the same.

That’s the brilliance of checks and balances. In the same way that Congress or the Supreme Court can rein in a renegade president, as was the case during Watergate, the president and Congress can place checks on an otherwise unconstrained court, if they believe the justices have exceeded their mandate.

In 1801, outgoing President John Adams appointed, and Congress confirmed, a number of “midnight” judicial nominees, in an effort to stymie incoming President Thomas Jefferson. John Marshall, then closing out his tenure as secretary of state, failed to deliver official commissions to several of these justices. When Jefferson instructed his secretary of state, James Madison, to withhold the commissions, in an effort to deny Adams’ nominees their seats on the bench, one of those confirmed nominees, William Marbury, sued. The case wound its way to the high court. In a decision penned by Marshall, who now served as chief justice, the court held that Madison had violated the law by withholding the commissions but also declined to order him to do so. In the same breath, the court asserted the right to strike down federal or state laws that it deemed unconstitutional. And so the concept of judicial review came into being.

Critics are correct on one point: The Constitution is silent on judicial review. It says only that the “judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” But many of the framers assumed that some form of review was a given.

Judicial review as a concept was well-established in 1787. English courts had long issued rulings upholding or striking down laws — rulings that, in aggregate, and alongside centuries of commentary, formed the basis of England’s unwritten Constitution. It was certainly well-established in the United States, even on the eve of Marshall’s decision. Between the Constitution’s ratification and 1803, federal and state judges struck down at least 31 statutes on the grounds that they violated either the federal or state constitutions. These rulings were generally received with silent acquiescence.

We also know that many of the Constitution’s framers and loudest proponents anticipated the Supreme Court’s role in adjudicating the constitutionality of laws and actions. In Federalist Paper 78, Alexander Hamilton said so explicitly, writing: “If it is said that the legislative body is themselves the constitutional judges of their own … it may be answered, that this cannot be the natural presumption, where it is not to be collected from any particular provisions in the Constitution. … It is far more rational to suppose, that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority.”

Hamilton wasn’t alone. At least 12 delegates to the Philadelphia convention affirmed the judiciary’s role in reviewing legislative measures, though their interpretations of this power varied. No delegates appear to have argued strongly in the opposite direction. Judicial review was already an established practice in state courts, a point that several delegates noted with approval. Madison lauded judges in Rhode Island who had “Refused to execute an unconstitutional law.” Elbridge Gerry observed that state judges regularly “set aside laws as being agst. the [state] Constitution.”

When other delegates proposed that judges also be given explicit power to veto legislation, Gerry and his fellow New Yorker, Rufus King, objected, noting that the courts “will have a sufficient check agst. encroachments on their own department by their exposition of the laws, which involved a power of deciding on their Constitutionality.” Arguing the opposite point, James Wilson advocated additional controls to block bad laws, noting that “[l]aws may be unjust, may be unwise, may be dangerous, may be destructive; and yet not be so unconstitutional as to justify the Judges in refusing to give them effect.”

Luther Martin, a delegate from Maryland, argued that “as to the Constitutionality of laws, that point will come before the Judges in their proper official character. In this character they have a negative on the laws.”

Hamilton, arguably the most full-throated proponent of judicial review, similarly wrote that “the interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is in fact, and must be, regarded by the judges as a fundamental law. It, therefore, belongs to them to ascertain its meaning as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body.”

The men who gathered in Philadelphia largely agreed that courts would serve as arbiters of what was and was not constitutional. So did delegates to state-level conventions that ratified the new Constitution. Delegates in seven such meetings discussed the concept of judicial review no fewer than 25 times. In addition, at least 74 federalist pamphlets, published in 12 of the 13 states, affirmed the court’s prerogative to strike down unconstitutional laws.

It’s clear from the record that the men who wrote the Constitution intended the Supreme Court, and the lower federal courts, to enjoy a constitutional veto over acts of Congress and of the states.

But they did not intend this power to be unchecked or unlimited.

Deeply ingrained in the Constitution genius are checks and balances. The president can veto legislation; Congress can override a veto. The Courts can invalidate an act of Congress or the president. And the executive and legislative branches enjoy checks against the judiciary.

The Constitution called for the establishment of a Supreme Court and lower federal courts. It left it to Congress and the president to decide just what shape the judiciary would take. They did so in the Judiciary Act of 1789, which created district courts, circuit (or appellate) courts, and a six-member Supreme Court. Over the years, Congress, with the president’s approval, has increased and decreased the number of justices on the Supreme Court, created and changed the jurisdiction of district and circuit courts, and adjusted the number of federal judges.

By now, it’s well-known that Congress can change the size, and thus the composition, of the Supreme Court by simple legislation. Court-packing, as it’s been called since 1937, when President Franklin Roosevelt unsuccessfully attempted to circumvent a hostile court by expanding its membership, is a deeply controversial practice.

Critically, but less widely understood, the Constitution also grants Congress the power to strip the Supreme Court of its jurisdiction over specific matters. Article III, Section 2 reads: “In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.”

At least one founder was clear about the intent of Section 2. Hamilton wrote, “From this review of the particular powers of the federal judiciary, as marked out in the Constitution, it appears that they are all conformable to the principles which ought to have governed the structure of that department, and which were necessary to the perfection of the system. If some partial inconveniences should appear to be connected with the incorporation of any of them into the plan, it ought to be recollected that the national legislature will have ample authority to make such exceptions, and to prescribe such regulations as will be calculated to obviate or remove these inconveniences.”

Defenders of judicial review appropriately point to Federalist 78 as evidence that Hamilton believed the Constitution contained an implicit power of judicial review. But he also believed that Congress could adjust the court’s jurisdiction.

In practice, so few instances exist of jurisdictional stripping that its meaning and scope are open to debate. But it has happened. In the late 1860s, federal authorities jailed William McCardle, a newspaper editor, under provisions of the 1867 Military Reconstruction Act. McCardle sued for his freedom, citing the Habeas Corpus Act of 1867. Congress denied the justices jurisdiction in the matter, and the court conceded that it was powerless to act.

Writing several decades later, Justice Felix Frankfurter, an FDR appointee, noted that “Congress need not give this Court any appellate power; it may withdraw appellate jurisdiction once conferred and it may do so even while a case is sub judice.” Chief Justice Warren Burger, whom President Richard Nixon placed on the bench, agreed, writing that Congress could pass simple legislation “limiting or prohibiting judicial review of its directives.”

No less than the executive and legislative branches, the judiciary — particularly, the Supreme Court — is limited in just how much power it can exert. But only if Congress and the president exercise their right to check its power.

In theory, Congress could very easily pass legislation denying the Supreme Court jurisdiction over a new voting rights act, a law codifying the right to privacy (including abortion rights), and other popular measures. If they so chose, Congress and the president could go further, reducing the court to a shell of its former self, leaving it to adjudicate minor matters of little significance. Of course, with the filibuster in place, this outcome is about as likely as a bill expanding the court’s membership, which is to say, very unlikely.

Would it be wise?

A world in which a highly partisan and increasingly unpopular Supreme Court found its jurisdiction routinely boxed out by Congress is hardly a recipe for political stability. With every change of control, a new Congress and president could overturn precedent and lock the court out of its intended role as a constitutional arbiter. Moreover, there would likely be widespread confusion over just what might happen, were Congress to strip the court of its jurisdiction over, say, the state legislative doctrine. Would it then be left to lower courts to adjudicate cases? And what if they disagreed?

Conversely, today’s court majority claims largely unchecked power.

John Marshall, the chief justice who first asserted the power of judicial review, was “notably cautious in dealing with cases that might excite Republican or popular sensibilities,” noted historian Charles Sellers. He sought consensus among the associate justices, Federalists and Republicans alike, operated with “restraint” (Sellers) and led with “lax, lounging manners” (Thomas Jefferson) rather than cutting partisanship. He did so because he understood that the court was a new institution, and were it to lose popular support, the powers it claimed for itself would become either unenforceable, or subject to congressional restraint.

Ultimately, it is the responsibility and prerogative of the executive and legislative branches to encourage greater restraint and humility on the part of the judiciary.

Judicial review is well-rooted in American political tradition. But so are checks and balances. To save the Supreme Court from itself, Congress might first have to shrink it.

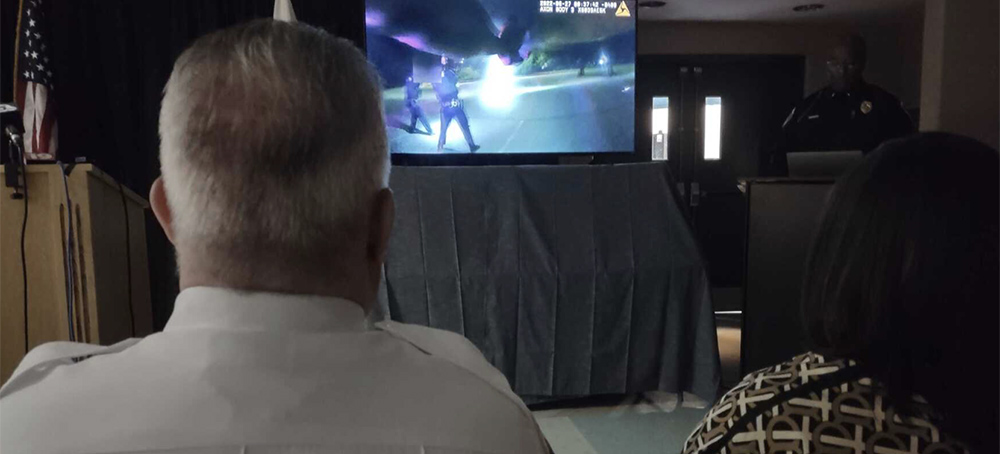

Akron Police Chief Stephen Mylett watches the video of the final minutes of Jayland Walker's life. He was fatally shot numerous times by eight police officers early Monday morning after an attempted traffic stop and police chase, according to police. (photo: Matt Richmond/Ideastream Public Media)

Akron Police Chief Stephen Mylett watches the video of the final minutes of Jayland Walker's life. He was fatally shot numerous times by eight police officers early Monday morning after an attempted traffic stop and police chase, according to police. (photo: Matt Richmond/Ideastream Public Media)

The video begins during the pursuit after police say they attempted to stop Jayland Walker for a traffic and equipment violation near the intersection of Thayer Street and East Tallmadge Avenue on Akron's north side shortly after midnight Monday morning.

Watch the video of the press conference here. The bodycam video of the shooting begins at 23:52. Viewer discretion is advised. The image of Walker's body is blurred in the video at the request of his family, police said.

Walker did not stop and officers initiated a pursuit, according to police. His vehicle merged on to state Route 8 heading southbound as officers gave chase, the video showed.

Less than a minute after the pursuit began, a pop can be heard on the video.

"That vehicle just had a shot come out of its door," said the officer wearing the bodycam. Police also showed images from an ODOT camera that showed a flash of light coming out of the side of Walker's car as he traveled along the highway.

The pursuit ended after Walker's vehicle exited the highway and stopped in a residential neighborhood near the intersection of Clairmont Avenue and East Wilbeth Road, according to police.

The bodycam shows a number of officers surrounding Walker's vehicle and yelling at him to get out of the car. Walker gets out of the passenger side of the vehicle and runs a short distance with a number of officers following on foot. Shortly after that, officers fire a barrage of bullets then call for a cease fire, and the video ends.

Police do not know how many times officers fired, Chief Stephen Mylett said during the press conference.

"Based on the video, I anticipate that number to be high," he said. "A lot rounds were fired, and I would not be surprised if the number at the end of the investigation is consistent with the number that has been circulating in the media."

Multiple news outlets have reported Walker was shot close to 60 times based on the medical examiner's preliminary summary. The Summit County Medical Examiner's report indicates over 60 wounds were found on Walker's body, but investigators are still working to identify entrance and exit wounds, Mylett said.

At the family's request, Walker himself is blurred in the video, and it is difficult to determine his exact movements. But police say he was wearing a ski mask.

“Actions by the suspect caused the officers to perceive that he posed a deadly threat to them,” according to a written statement from police.

The eight officers involved in the shooting have been placed on paid administrative leave, and the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation is investigating the shooting, Mylett said.

After the shooting officers attempted to provide first aid, according to police. Officers attempted to put Walker in a police car to transport him to the hospital, but emergency medical personnel arrived and Walker died at the scene.

Police say they found a handgun, a loaded magazine and a wedding ring in Walker's car.

City officials met with Walker's family before the press conference to allow them to review the footage before it was released, a city media release said.

The family's attorney, Bobby DiCello spoke immediately following the release of the video. He recognized the police for releasing the video and called for peace, privacy and justice for the family.

Both city officials and Walker family representatives have begged the public for peace despite the content of the video which Akron Mayor Dan Horrigan called “shocking and hard to take in” and a family attorney called “heartbreaking.”

"Nobody should ever suffer the fate that Jayland Walker did," said Paige White, an attorney for the family. "Sunday morning, Jayland woke up in his bed and 24 hours later he was in the morgue."

"It’s not troubling. It’s beyond that. There are no words to describe it," she said of the video. "We are begging you, that family is begging you, Jayland is begging you to stay peaceful."

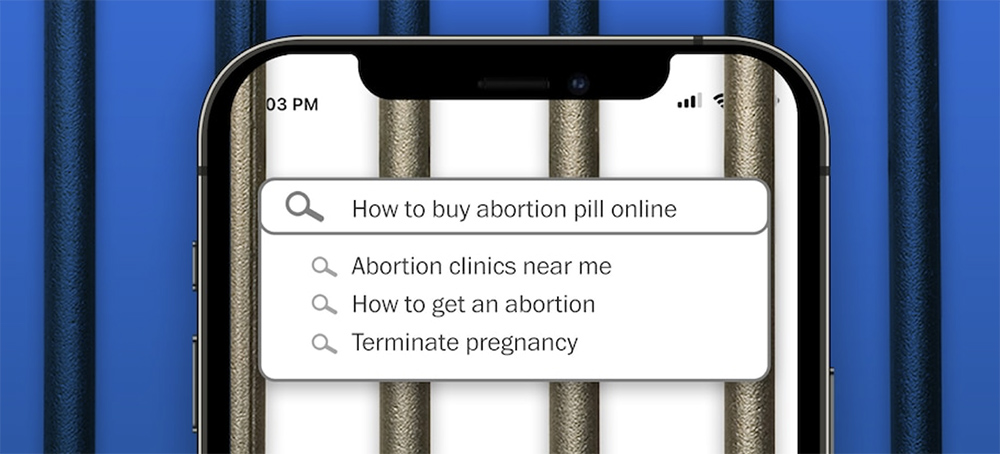

Texts and searches about abortion are being used by prosecutors. (image: wp/istock)

Texts and searches about abortion are being used by prosecutors. (image: wp/istock)

The data privacy risks associated with abortion aren’t hypothetical. Cases in Mississippi and Indiana could preview how digital evidence could be used post-Roe.

Fisher, a mother of three, told paramedics she had not known she was pregnant. But she later admitted to a nurse that she had known about the pregnancy. And after she voluntarily surrendered her iPhone to police, investigators discovered that Fisher, a former police dispatcher, had searched for how to “buy Misopristol Abortion Pill Online” 10 days earlier.

While there is no evidence Fisher took the pills — court records indicate only that she “apparently” bought them — her search history helped prosecutors charge her with “killing her infant child,” identified in the original indictment as “Baby Fisher.” The 2017 case is one of a handful in which American prosecutors have used text messages and online research as evidence against women facing criminal charges related to the end of their pregnancies.

Since the Supreme Court on overturned the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling on June 24— opening the door to state bans on abortion from the moment of conception — privacy experts have warned that many more pregnant people and their abortion providers could find themselves in similar circumstances. While some fret over data maintained by period trackers and other specialty apps, the case against Fisher shows that simple search histories may pose enormous risks in a post-Roe world.

“Lots of people Google about abortion and then choose to carry out their pregnancies,” said Laurie Bertram Roberts, a spokeswoman for Fisher. “Thought crimes are not the thing. You’re not supposed to be able to be indicted on a charge of what you thought about.” Fisher declined to comment.

Despite mounting concerns that the intricate web of data collected by fertility apps, tech companies and data brokers might be used to prove a violation of abortion restrictions, in practice, police and prosecutors have turned to more easily accessible data — gleaned from text messages and search history on phones and computers. These digital records of ordinary lives are sometimes turned over voluntarily or obtained with a warrant, and have provided a gold mine for law enforcement.

“T he reality is, we do absolutely everything on our phones these days,” said Emma Roth, a staff attorney at the National Advocates for Pregnant Women. “There are many, many ways in which law enforcement can find out about somebody’s journey to seek an abortion through digital surveillance.”

The debate over abortion in the United States has long centered on the definition of “fetal viability,” the point at which a fetus can survive outside the womb, which experts say is generally about 24 weeks. The vast majority of abortions in the United States occur long before that point. Nearly 80 percent of abortions reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are in the first nine weeks, according to 2019 data.

Under Roe, the right to abortion before fetal viability was guaranteed. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Supreme Court rejected that test and cleared the way for states to restrict access to abortion much earlier in pregnancy.

Women have been punished for terminating pregnancy for years. Between 2000 and 2021, more than 60 cases in the United States involved someone being investigated, arrested or charged for allegedly ending their own pregnancy or assisting someone else, according to an analysis by If/When/How, a reproductive justice nonprofit. If/When/How estimates the number of cases may be much higher, because it is difficult to access court records in many counties throughout the country.

A number of those cases have hinged on text messages, search history and other forms of digital evidence.

Digital evidence played a central role in the case of Purvi Patel, an Indiana woman who the National Advocates for Pregnant Women said in 2015 was the first woman in the United States to be charged, convicted and sentenced for “feticide” in ending her own pregnancy. The state’s evidence included texts Patel exchanged with a friend from Michigan, in which she talked about her plans to take pills that can induce abortion, according to court records.

Prosecutors also cited her web history, including a visit to a webpage entitled “National Abortion Federation: Abortion after Twelve Weeks.” On her iPad, police found an email from InternationalDrugMart.com. Detectives were able to order mifepristone pills and misoprostol pills from that website without a prescription, according to court records.

Patel was sentenced to 20 years in prison, but was later released after her conviction was overturned, according to the Associated Press. The Indiana Court of Appeals ruled that the state’s “feticide” law wasn’t meant to be used to prosecute women for their own abortions.

Patel did not respond to a request for comment. One of her lawyers declined to comment.

Cases like Patel’s show how different types of digital evidence might be used to build a case against someone terminating a pregnancy, said Corynne McSherry, the legal director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. She said someone seeking an abortion cannot be solely responsible for considering the risks of leaving a digital trail.

“It may be difficult to think about digital privacy first when you have other things you’re worried about,” McSherry said. She also said given the history of surveillance of marginalized communities in the United States, there may be racial disparities in the role that digital evidence plays in the criminalization of abortion. Fisher is Black, and Patel is Indian American.

McSherry said tech companies need to play a greater role in protecting reproductive health data. Google on Friday announced it would delete location history when users visit an abortion clinic. Governments could also play a role through laws protecting privacy. Health care workers and friends also are sometimes forced to provide evidence, McSherry added.

“Privacy is a team sport — when you take steps to protect your own privacy, you also take steps to protect the community,” she said.

In Fisher’s case, a grand jury charged her with second-degree murder after the state’s medical examiner determined that the baby had been born alive and died from asphyxia. Fisher spent several weeks in jail before the district attorney summoned a new grand jury, which declined to bring charges after hearing evidence that the test used to establish a live birth was antiquated and unreliable.

Many activists have expanded their digital precautions as a way of life, understanding that routine data might prove problematic. Activists in Europe take extra precautions when working with women in Poland, where abortion is severely restricted. A Polish court in 2020 banned procedures even in instances of fetal abnormalities, one of the last remaining circumstances under which abortion had been permitted.

Groups like Abortions Without Borders have been filling the void, helping those who are pregnant travel to other countries with less restrictive laws and arranging for activists in other countries to send Polish women abortion pills. Poland’s laws permit a woman to give herself an abortion, such as by taking a pill, but prohibit anyone else from helping her access the procedure.

Activists also use virtual private networks, which can minimize data collected about browsing, and encourage Polish women to contact them on encrypted channels like Signal. They delete all online conversations after the person has had the abortion and caution the person not to post on social media about their experiences, after some faced online harassment. One organization that provides funds for Polish people to get the procedure in Germany pays abortion clinics directly, rather than providing funds to patients, to ensure there are no digital records.

And there is a fresh worry on European abortion activists’ minds: the introduction of what they describe as a “pregnancy register” in Poland. The Polish government approved a measure last month that requires doctors to save more patient information in a central database — including data on pregnancies.

The stakes have risen since the arrest of Justyna Wydrzyńska, a Polish activist who operates a hotline for the organization Abortion Dream Team. She is on trial, facing three years in prison, for allegedly providing abortion pills in 2020 to a woman who said she was the victim of domestic violence.

Wydrzyńska was arrested after the woman’s partner reported her to the authorities. Police confiscated Wydrzyńska’s computer, as well as her children’s devices, during the investigation. Wydrzyńska couldn’t be reached for comment for this story, but previously has told The Post that the case has not dissuaded her from activism.

“Our safety is actually a matter of solidarity also," said Zuzanna Dziuban, who is part of the Abortion Without Borders network that helps Polish women travel to abortion clinics in Berlin. "Not only for us activists … but also for people who use our help.”

In this Aug. 17, 2020, photo, inmate firefighters - notable by their bright orange fire gear compared to the yellow worn by professional firefighters - prepare to take on the River Fire in Salinas, Calif. The California Senate on Thursday, June 23, 2022, rejected a proposal to ban involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime after Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration warned it could cost taxpayers billions of dollars by forcing the state to pay inmates who work while in prison a $15-per-hour minimum wage. (photo: Noah Berger/AP)

In this Aug. 17, 2020, photo, inmate firefighters - notable by their bright orange fire gear compared to the yellow worn by professional firefighters - prepare to take on the River Fire in Salinas, Calif. The California Senate on Thursday, June 23, 2022, rejected a proposal to ban involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime after Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration warned it could cost taxpayers billions of dollars by forcing the state to pay inmates who work while in prison a $15-per-hour minimum wage. (photo: Noah Berger/AP)

The proposed measure would have elevated California prisoner pay to $ 15 an hour and given worker protections.

While the 13th Amendment outlaws slavery, California law allows involuntary servitude to punish someone for a crime. Inmates lack the same protections regular workers have regarding minimum wage and benefits. Prisons can also enforce discipline for refusing to work, including reduced privileges like limits on visits, telephone calls, and time out of their cells.

Assemblymember, now state Senator Sydney Kamlager introduced the “ Assembly Constitutional Amendment 3 (ACA 3), the California Abolition Act, in 2020. The state assembly passed the amendment with a 59-0 vote in March. As Kamlager notes, she ran out of time and supporters when the amendment fell seven votes short of the two-thirds margin it needed in the Senate. Voters in states like Louisiana, Oregon, and Tennessee will decide on similar provisions in the November elections.

“One of the challenges we’ve had is people are conflating policy with a moral argument about taking out words that are historical, that are loaded, that are remnants of a slave past and that were implemented in ways that made people less human,” Kamlager said in an interview.

The American Civil Liberties released a report calling for incarcerated workers to be paid fairly, adequately trained, and able to gain transferable skills. Former California State Prison inmate Samual Brown had to clean and disinfect prison cells during the height of the pandemic even while having asthma. While serving a 24-year attempted murder conviction, Brown worked several jobs, including porter, dishwasher, and hospital janitor, paying .75 cents an hour.

As his comments to Cal Matters show, he could not change his job despite his medical condition.

“They have various ways they force you,” said Brown, who was released this year from California State Prison in Los Angeles County. “This includes stripping you of your phone rights, stripping you of your visitation rights, stripping you of your ability to order personal food.”

A gharial swings its snout through the water to feed on fresh fish. (photot: Julie Larsen Maher)

A gharial swings its snout through the water to feed on fresh fish. (photot: Julie Larsen Maher)

According to the WWF program in Pakistan, the government there has asked Nepal, which has a long-running program raising the critically endangered reptiles in captivity, to provide hundreds of juvenile gharials for a planned reintroduction program.

Gharials, a fish-eating species with a distinctive slender snout, were once found in the Indus River in Pakistan and the Brahmaputra that runs through China, India and Bangladesh. Today, the species is virtually extinct from countries other than Nepal and India, where it occurs in the Ganges River and its tributaries.

“The last time gharials were recorded in Pakistan was around 1985 in the Nara Canal,” a channel of the Indus, said Rab Nawaz, senior director of biodiversity at WWF-Pakistan. “Some reports were received from the same area after 2000, but despite surveys by WWF and the local wildlife department, there was no success in locating the species.”

While local support for gharial reintroduction is said to be high, Pakistan’s request to Nepal faces multiple obstacles, including funding shortages and concerns from Nepal that Pakistan may not have done enough to change the conditions that led to the gharial’s local extinction there.

Return of an apex predator

Pakistan’s government wants to reintroduce gharials in the Nara Canal wetland system to improve its biodiversity. “Apex predators such as gharials ensure ecological balance,” Nawaz told Mongabay. “They can also become a basis for wildlife tourism that could provide a source of income for local communities.”

Enthusiasm for the reintroduction of gharials is growing in Pakistan following the growth of a healthy population of mugger crocodiles (Crocodylus palustris) in the Nara Canal, Nawaz said. The region also has a relatively low human population and a good network of protected areas such as the Deh Akro I and II wetland complexes consisting of 36 lakes with desert, wetland, marsh and agricultural landscapes.

Although an expert assessment would be necessary to ascertain the exact number of gharials for the reintroduction program, the figure would be in the hundreds, Nawaz said. It’s necessary to address the issues that led to the extinction of gharials in Pakistan before they can be reintroduced, he said.

“It’s been a long time since we started a conversation with Nepal,” Nawaz said. “The initial response [from Nepal] was positive, but the project couldn’t start due to lack of funding.”

An official at Nepal’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation confirmed to Mongabay that there had been an email between officials from Nepal and Pakistan two months ago on the issue.

According to recent counts, fewer than 200 breeding adults survive in the wild in Nepal, where the species is threatened by fishing activity, changes in river flow, and poaching.

The governments of Nepal and India both maintain captive-breeding programs to maximize the number of gharial eggs that survive and to introduce healthy hatchlings into river systems.

Ram Chandra Kandel, director-general at Nepal’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation, confirmed to Mongabay that he had received an email from Pakistan on the issue.

However, a decision on the matter hasn’t been taken yet, he said. He added it would be difficult for the proposal to move ahead as gharials are virtually extinct in Pakistan. “We would have liked to get some gharials from the Indus and send some of our gharials there to ensure genetic diversity in both the populations. As that is not the case, it would be difficult for us to send our gharials to Pakistan,” he said.

Special Coverage: Ukraine, A Historic Resistance

READ MORE

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.