Over the past few weeks, former Vice President Joe Biden has been making an effort to recast his record on Social Security as one of a champion who defended the program from assaults, rather than one who consistently argued that it ought to be cut.

The value of such a revision is clear: Austerity is no longer a politically viable platform for Democrats to take in the primary. His defense of his record has included multiple television interviews, public comments, and even an ad attacking Sen. Bernie Sanders for “dishonest smears” challenging him on Social Security. In the ad, Biden makes a sweeping claim: “I’ve been fighting to protect — and expand — Social Security for my whole career. Any suggestion otherwise is just flat-out wrong.” At Vice’s Black and Brown Forum in Iowa this week, when pressed on his proposal to freeze Social Security payments by moderator Antonia Hylton, he simply lied: “I didn’t propose a freeze.”

In fact, Biden has argued for cuts or freezes to Social Security throughout much of his career. Earlier in January, The Intercept wrote about several instances in which Biden advocated for cutting Social Security over the course of his career. Biden, when he acknowledges his past support for cuts, portrays the advocacy as deep in the past. But a close inspection finds reams of more recent evidence of Biden’s support for cuts — including in Biden’s recent recounting of a conversation he had with China’s president, Xi Jinping, and in his choice of Bruce Reed, a longtime deficit hawk, as a senior policy adviser in his current presidential campaign.

Reed, a longtime Biden aide, played a central role in advocating cuts to the New Deal-era program as a co-founder of the Democratic Leadership Council, as the top staffer for a controversial commission dedicated to slashing the deficit, and then as Biden’s chief of staff during the Obama administration. In Washington, D.C., he would be the last high-level staffer a campaign would bring aboard if it was genuinely intent on expanding, not cutting, Social Security.

Andrew Bates, a spokesperson for Biden, said that, as president, Biden would push to expand Social Security. “As President, Joe Biden would expand Social Security benefits — paid for with new taxes on the wealthiest Americans. And as Senator Sanders himself said in 2015: ‘Joe Biden is a man who has devoted his entire life to public service and to the wellbeing of working families and the middle class,’” Bates said.

The cuts came closest to happening amid talks between the Obama administration and congressional Republicans aimed at hammering out a so-called grand bargain. The most prominent vehicle for those negotiations was known as the Bowles-Simpson Commission, a bipartisan panel charged with making recommendations to Congress on how to reduce the federal debt. It was chaired by Alan Simpson, a former Republican senator from Wyoming, and Erskine Bowles, a former Democratic senator from North Carolina.

And the staff director for Bowles-Simpson? Bruce Reed. “Our team was led by Bruce Reed, and believe me, there wouldn’t be a Simpson-Bowles Report without Bruce,” Bowles later wrote. The chairs of the commission recommended reducing Social Security benefits for the top half of earners, cutting the amount the benefit grew relative to inflation and raising the retirement age to 69. Progressives skewered it, with New York Times columnist Paul Krugman noting that “it raises the Social Security retirement age because life expectancy has risen — completely ignoring the fact that life expectancy has only gone up for the well-off and well-educated, while stagnating or even declining among the people who need the program most.”

“Simpson-Bowles is terrible,” he concluded. “Yes, I know, inside the Beltway Simpson and Bowles have become sacred figures. But the people doing that elevation are the same people who told us that Paul Ryan was the answer to our fiscal prayers.”

The commission failed to secure the supermajority needed for its recommendations to move on to Congress, but the administration was far from done try to implement them. After finishing with the commission, Reed was brought on as Vice President Biden’s chief of staff, to continue to work on a grand bargain. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a Washington group dedicated to cutting Social Security and other entitlement programs, celebrated the appointment. We can’t think of a better person for the job,” CRFP said in a statement. “We hope Bruce will be able to leverage his expertise in this new position, and that his appointment portends positive steps from policymakers in the Administration in tackling our rising deficits and debt.”

At the time, the Fiscal Times wrote, “The recent appointment of Bruce Reed, the Executive Director of President Obama’s National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, as Vice President Biden’s Chief of Staff is the latest signal that the administration plans to endorse many of the Commission’s recommendations. Since one target for deficit reduction appears to be Social Security and social insurance programs more generally, it’s essential to understand the important role that social insurance plays in the economy.”

National Journal reported that Reed helped Biden shape his approach to the debt-reduction commission, “often sitting right behind the vice president in meetings with Republican leaders.” Reed, National Journal noted, had sided with a cadre of other Obama administration advisers to “back cuts to Medicare and Social Security despite pushback from some Democrats who opposed touching entitlements.”

Reed was not some entry-level staffer. By that point, he had been a top domestic policy adviser in the Clinton administration, where he had championed the reform of welfare and otherwise advocated for slashing government spending. He was also co-founder of the Democratic Leadership Council, which represented the pro-business wing of the party that rose in the 1980s.

The DLC was the only influential Democratic institution to lobby not only for cutting Social Security benefits, but also supported the push for privatization of Social Security. In the 1990s, DLC began calling for “limited privatization” of the program that would allow individuals to invest part of their benefits in the stock market. “Personal accounts would refashion Social Security from a system of wealth transfer into one that also promotes individual wealth creation and broader ownership,” the DLC argued, encouraging the Clinton administration to embrace a grand bargain with Republicans.

In 1998, a plan to embrace the grand bargain came close to fruition. In secret negotiations between House Speaker Newt Gingrich, Rep. Bill Archer, R-Texas, and President Bill Clinton, a proposal was hatched to reduce Social Security benefits and embrace partial privatization in exchange for Gingrich to drop his demand for new tax cuts. That plan came perilously close to being implemented, but was blown up by Gingrich’s drive to impeach Clinton rather than cut a deal.

After Reed left the DLC and joined the debt commission, the organization continued to lobby for cuts to Social Security and a hike in the retirement age. The DLC submitted comments to the Bowles-Simpson panel suggesting that Social Security consider an approach that included “offering ways to mix part-time and online work with partial Social Security benefits after age 67 and into the eighth decade of life.”

Reed has remained in Biden’s inner circle. The campaign paid him more than $35,000 for “policy consulting” last year. As Politico reported, Reed routinely travels with Biden, continuing to serve as the former vice president’s chief policy adviser on the road.

The next phase of the Obama-era bargain talks, in the wake of Bowles-Simpson, became the so-called Biden Committee, a series of negotiations over deficit reduction chaired by Biden, staffed by Reed, and joined by House Majority Leader Eric Cantor; Sen. Jon Kyl, R-Ariz., Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Md.; and others. Biden, in talks that were covered closely in Bob Woodward’s book “The Price of Politics,” put Social Security and other cuts on the table but couldn’t get to a yes because Republicans refused to agree to any tax cuts. (Fly-on-the-wall books on the later years of the Obama administration lack the drama of Trump-era tell-alls.)

In the summer of 2011, the talks evolved into the Super Committee, made up of six Democrats and six Republicans from the House and Senate, charged with coming up trillions in budget cuts. Woodward obtained a copy of the administration’s recommendations to that committee, and it largely mirrored what was on offer during the Biden Committee talks and included significant cuts to Social Security.

But then came Occupy Wall Street. By the fall, coverage was dominated by protests that began in New York City around the slogan “We are the 99 percent,” calling attention to vast wealth inequality and the country’s superrich in a way that hadn’t happened since the days of the robber barons. The movement spread to cities and towns across the country, with encampments springing up in downtowns in every region. That fall, after Bank of America announced a new $5 monthly fee for debit cards, it faced so much backlash that it backed down and rescinded the fee.

In early November, a group of protesters set out from New York to Washington, calling themselves Occupy the Highway and aiming to hit the capital on November 22, the day the Super Committee was due to issue its legislation, which was designed to glide through Congress.

On November 21, the Super Committee collapsed, lacking the votes to get the legislation out of its own committee. “Super Committee Fail = Occupy Wall Street Win,” celebrated Michael Glazer, an organizer of Occupy the Highway, in a statement that day. “The so-called Super Committee was a failure from the beginning. No one has the courage to stand up inside our corrupt political system and fight for regular Americans. So, we will continue to take a stand outside the system.”

The willingness of that faction of protesters to even acknowledge the Super Committee was controversial inside Occupy, which considered direct interaction with the political system futile at best and corrupting at worst. But as Glazer emphasized, Occupy had blown up the committee from the outside by changing the political terrain. Concerns over the deficit and a preference for austerity were replaced by a conversation about economic inequality, one that would ultimately boost the Sanders campaign in 2015 and put an end, for the time being, to Democratic attempts to cut the deficit by trimming entitlement programs. (It wasn’t completely dead: An ad Biden released this week includes footage of Biden telling Paul Ryan, at a vice presidential debate, that he is committed to protecting Social Security. The Obama administration’s 2013 budget included Social Security cuts regardless. By 2015, those cuts were out.)

But even while the logic of the party changed, deficit scolding had become such a firm element of Biden’s brand that he had a hard time letting go. In 2018, at a speech at the Brookings Institute, Biden again returned to Social Security, criticizing then-House Speaker Paul Ryan’s recent tax cut but agreeing with his focus on Social Security and Medicare.

At a speech in July 2018, Biden again addressed Social Security and Medicare, relaying an anecdote in which Chinese leader Xi Jinping asked him if China’s investments in U.S. debt were safe and specifically if the United States planned to do something about the cost of entitlement programs — Social Security and Medicare — which Xi saw in conflict with meeting U.S. obligations to China. “I said don’t buy any more of our T-bills,” Biden whispered, as he does when he’s letting the audience believe that he’s letting them in on something secret or saying something verboten.

“‘I hope you’re able to do something about your entitlement problem,’” Biden said Xi told him. “And I said, ‘With regard to our entitlement problem, Mr. President, ours is a political problem, and it’s soluble, but my god, your problem, your one-child policy has produced a circumstance that by 2022, you’ll have more people retired than working.’”

It’s a story Biden has been telling versions of since 2011, and it has consistently cast entitlements as a problem to be solved. Biden’s reference to “our entitlement problem” as “a political problem” that is “soluble” suggests that his view of the programs hadn’t evolved over the past 40 years, though his official position in his 2020 campaign is the opposite, that benefits should be expanded, not shrunken.

This past week, Biden steadily ratcheted up his revision of his record. At Vice News’s Brown and Black Forum in Iowa on Monday, he was pressed on Social Security. “Do you think though that it’s fair for voters to question your commitment to Social Security when in the past you proposed a freeze to it?” he was asked by Vice moderator Hylton.

“No, I didn’t propose a freeze,” he said.

“You did,” she corrected.

On Wednesday, Biden joined the crew at MSNBC’s “Morning Joe” and was asked about the Social Security flare-up. “I have 100 percent ratings from the groups that rate Social Security [votes], those who support Social Security,” Biden said.

The claim was in line with, but more specific than, his earlier assertion of “I’ve been fighting to protect — and expand — Social Security for my whole career.”

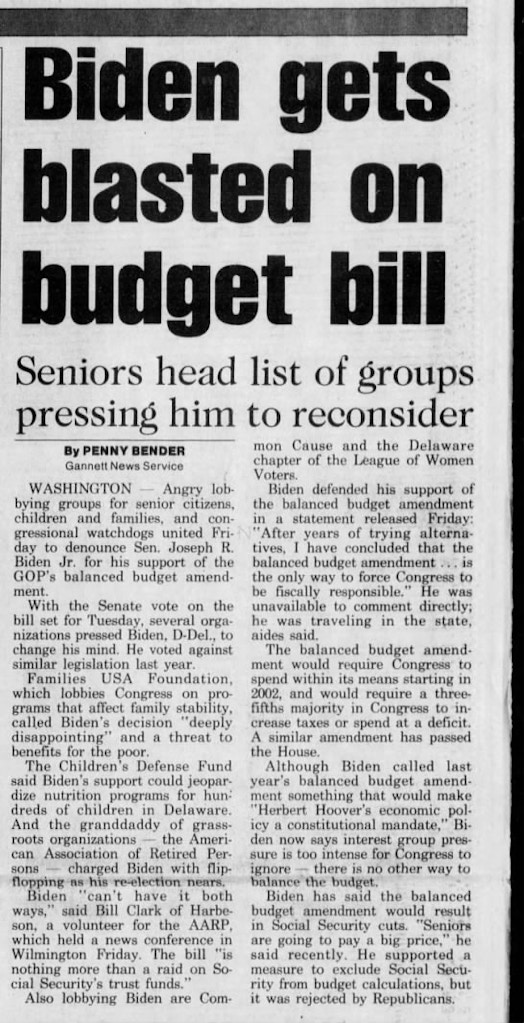

It’s also not true. A review of media reports from the 1990s shows that groups dedicated to protecting Social Security, including the AARP, saw Biden’s votes and advocacy as a betrayal. Ahead of the critical vote on the Balanced Budget Amendment in 1995, the Delaware News Journal carried a story that was headlined: “Biden gets blasted on budget bill: Seniors head list of groups pressing him to reconsider.”

An article on Biden’s support for the balanced budget amendment in the Delaware News Journal, published on Feb. 25, 1995.

Image: Delaware News Journal

The story began: “Angry lobbying groups for senior citizens, children and families, and congressional watchdogs united Friday to denounce Sen. Joseph R. Biden Jr. for his support of the GOP’s balanced budget amendment.”

The article noted that Biden himself had previously warned that “Seniors are going to pay a big price” thanks to the amendment. An AARP representative is quoted saying that Biden “can’t have it both ways” and that the bill “is nothing more than a raid on Social Security’s trust fund.”

Another News Journal article from the time reported that the “defections” of Biden and another Democratic senator “were a serious blow to opponents of the legislation, said David Certner, an official of the American Association of Retired People, which fears that the amendment will erode Social Security benefits.”

There were a number of groups scoring votes on legislation around Social Security at the time — meaning that they gave ratings to legislators based on their votes — including the NAACP, Americans for Democratic Action, the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare, and the National Council of Senior Citizens. Biden did not get 100 percent scores from any of those groups because of his votes to undermine Social Security.

The amendment passed the House and fell one vote short in the Senate, the Constitution just barely dodging the bullet. Ultimately, the focus on the measure’s impact on Social Security, according to the New York Times, swayed enough Democrats to stop it. In the House, then-Rep. Sanders had zeroed in on the amendment’s effect on Social Security. “The balanced budget amendment will be a disaster for working people, for elderly people, for low-income people,” he said on the House floor. “It will mean, in my view, the destruction of the Social Security system as we know it.”

Sanders was asked on Friday if he would apologize to Biden for criticizing him on Social Security, as he had apologized for a surrogate’s op-ed that argued Biden had a corruption problem. “No,” Sanders said. “There are ways to raise money in order to protect the working families of this country. Cutting Social Security ain’t one of ’em.”

Wait! Before you go on about your day, ask yourself: How likely is it that the story you just read would have been produced by a different news outlet if The Intercept hadn’t done it?

Consider what the world of media would look like without The Intercept. Who would hold party elites accountable to the values they proclaim to have? How many covert wars, miscarriages of justice, and dystopian technologies would remain hidden if our reporters weren’t on the beat?

The kind of reporting we do is essential to democracy, but it is not easy, cheap, or profitable. The Intercept is an independent nonprofit news outlet. We don’t have ads, so we depend on our members — 35,000 and counting — to help us hold the powerful to account. Joining is simple and doesn’t need to cost a lot: You can become a sustaining member for as little as $3 or $5 a month. That’s all it takes to support the journalism you rely on.

Consider what the world of media would look like without The Intercept. Who would hold party elites accountable to the values they proclaim to have? How many covert wars, miscarriages of justice, and dystopian technologies would remain hidden if our reporters weren’t on the beat?

The kind of reporting we do is essential to democracy, but it is not easy, cheap, or profitable. The Intercept is an independent nonprofit news outlet. We don’t have ads, so we depend on our members — 35,000 and counting — to help us hold the powerful to account. Joining is simple and doesn’t need to cost a lot: You can become a sustaining member for as little as $3 or $5 a month. That’s all it takes to support the journalism you rely on.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.