Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

The article below is satire. Andy Borowitz is an American comedian and New York Times-bestselling author who satirizes the news for his column, "The Borowitz Report."

“I could be wrong, but I vaguely remember that he was maybe this guy lying down on a beach?” Harland Dorrinson, who lives in Phoenix, said. “There was a picture of him going around. He was on a beach. I don’t remember what was going on, but it wasn’t good.”

“Was he the traffic-cone guy?” Carol Foyler, a resident of Akron, said. “I think he did something with traffic cones, blocking off traffic and stuff, and people were pissed. Am I thinking of the right guy? I’m a little fuzzy on all of the details, but it wasn’t good.”

Tracy Klugian, who lives in San Jose, said that, at first, the name Chris Christie didn’t “ring a bell,” but then he summoned a distant memory of Christie being associated with Donald Trump. “There was this time when Trump was giving a speech, and Christie was this guy standing behind him with this insanely pained expression on his face,” he said. “Was that him, or am I confusing him with someone else? Anyway, it wasn’t good.”

READ MORE  President Joe Biden talks with reporters before boarding Marine One on the South Lawn of the White House in Washington, May 26, 2023. (photo: Susan Walsh/AP)

President Joe Biden talks with reporters before boarding Marine One on the South Lawn of the White House in Washington, May 26, 2023. (photo: Susan Walsh/AP)

Grassroots organizers and large groups like Greenpeace and the NAACP have expressed grave concern over the contents of the debt ceiling deal, arguing the impact on Black Americans and other marginalized groups could be disastrous. Their concerns raise the question, did President Joe Biden make the best of a bad situation, or did the GOP take him for a ride?

- Caps on non-defense spending.

- Roll-backs on environmental protections.

- An end to the student loan payment freeze in August

- New work requirements for food stamps and TANF recipients.

- The debt limit will be raised to 2025

Aspects of the bill could be considered wins for Democrats. For example. although the age was lowered for work requirements for food stamps, that was potentially offset by the bill removing work requirements for other groups. In fact, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that there could actually be a small increase in the number of people eligible for food stamps.

But overall, progressives argue that the bill was mostly a give away to GOP interests.

Will The Debt Deal Hurt Black Communities?

Black Lives Matter Co-Founder and Black Futures Lab Principal Alicia Garza doesn’t mince words when discussing her concerns about the new debt deal.

“The things that we’re seeing in this proposal are very reminiscent of the Regan era,” says Garza. “work requirements to receive basic assistance, cuts to education, cuts to the kind of safety net that makes America at least in theory, the land of the free and the home of the brave, and who suffers in these kinds of games are Black communities.”

Natalie Mebane, Climate Campaign Director at Greenpeace USA, is equally direct. “There’s absolutely nothing that I like about the debt limit compromise,” says Mebane. “There’s not a single line, there’s not a single thing that I want in there.”

What Does The Debt Deal Mean for The Environment?

Mebane is particularly concerned about the environmental impacts of the bill.“The environmental provisions alone are absolutely horrendous,” “[This] is going to harm everybody, but it’s especially going to harm communities that have already faced the brunt of environmental racism, which are mainly Black communities and indigenous communities.”

The provision that has environmental groups really up in arms is a change to the National Environmental Policy Act, which would limit the Environmental Protection Agencies’ ability to review a project’s environmental impact. It may sound small, but the effect would be massive, says Mebane. Without these types of guardrails on corporations, the kinds of disasters we’ve seen time and time again in the Black community (re: Cancer Alley) will be much more likely, she argues.

“This legislation harms everybody, but especially Black communities,” she says. “Black communities are already severely impacted by pollution at a significantly higher rate than all other communities.”

Did Biden Allow The GOP to Take Him For a Ride?

Tamara Toles O’Laughlin, Founder of Climate Critical Earth, part of the Movement for Black Lives, says that the White House allowed Republicans to manufacture a crisis for their own purposes. “We’ve been backed into a corner that was entirely foreseeable,” says O’Laughlin.

In essence, she argues that Republicans played a high-stakes game of chicken with the economy, and Democrats lost. “The fact that we could end up in a moment that that that stirs up yet another crisis on schedule,” says O’Laughlin. “And the only way to get out of it is to just throw a whole lot of black people under the bus, a whole bunch of poor people under the bus right next to them, and a whole bunch of folks who have been made in invisible under the bus, that all seems really super convenient.”

Not everyone shares the same assessment of Biden’s negotiation tactics. Algernon Austin, Director of Race and Economic Justice at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, says Republicans had the nation over the barrel.

“It wasn’t as bad as the hostage takers wanted,” says Austin. “So, in that sense, it’s a positive outcome because the people who were holding the United States hostage really wanted to do much more harm.”

READ MORE  A Pride parade in Lummus Park, South Beach, Florida, in 2021. (photo: Giorgio Viera/AFP)

A Pride parade in Lummus Park, South Beach, Florida, in 2021. (photo: Giorgio Viera/AFP)

As Ron DeSantis attacks LGBTQ+ rights and threats are reported, planned events are canceled

The inaugural Pride month event that Bozanich organized in St Cloud last year featured an open-air parade and a drag show performance. This year, the 30-year-old photographer had scheduled a private event on 10 June at a gym that would once again include a drag show and would be open only to adults who had bought tickets in advance.

News of the Protection of Children law and the appearance of a road sign in the nearby Orlando neighborhood of Lake Nona that read “kill all gays” prompted all four drag show performers to cancel their appearances. That forced Bozanich to scrap the event altogether.

“That [sign] was very shocking to members of our community,” said Bozanich. “The performers felt they could be made an example of in some way, and we couldn’t ensure their security.”

The passage of similar laws targeting drag performances in other Republican-controlled state legislatures has cast a pall over this year’s Pride celebrations, including in Texas, Montana and Arkansas. Organizers in Tennessee are awaiting a federal judge’s ruling on the constitutionality of a law passed by the state legislature in March that places restrictions on where “adult cabaret” can be staged.

A drag show scheduled to take place this week at Nellis air force base in Nevada was canceled on short notice after Department of Defense officials advised organizers that the performance would contradict the defense secretary Lloyd Austin’s recent congressional testimony that the Pentagon would not fund such events.

Meanwhile, brands are navigating rightwing attacks on LGBTQ+ people, in the wake of a boycott against Bud Light for working with the trans influencer Dylan Mulvaney. Target announced the removal of some Pride items from its shelves last month after some of its employees received threats that affected their “sense of safety and wellbeing while at work”.

A coalition of more than 100 LGTBQ+ organizations responded by issuing a statement this week calling on Target and the business community to “reject and speak out against anti-LGBTQ+ extremism going into Pride Month”. (In its statement announcing the withdrawal of Pride-related merchandise, Target did reaffirm its “continuing commitment to the LGBTQIA+ community”.)

But with DeSantis having officially launched a presidential campaign last month, the spotlight remains on Florida. His administration foreshadowed the introduction and eventual passage of the Protection of Children Act when it filed a complaint last March seeking to revoke the liquor license of a Hyatt Regency hotel in Miami last March, after it hosted a Christmas drag queen show where children were reportedly among the audience.

A month later, a Pride parade scheduled in the seaside city of Port St Lucie was canceled and attendance at related events was restricted to adults at least 21 years old after organizers and local officials reached an agreement to scale back the festivities.

This year’s annual Tampa Pride festival went ahead as scheduled in the Gulf coast city on 25 March, but organizers recently decided to cancel a Pride on the River celebration slated for the fall after some sponsors expressed concerns over the outdoor setting.

“A parade with drag queens on boats or a public stage can’t be fenced off,” explained Carrie West, a retired businessman and president of the Tampa Pride organization. “It’s a very scary time for the LGBTQ+ community with the political climate right now. With DeSantis running for president, he wants to make a name for himself by campaigning against us.”

A deputy press secretary for the Florida governor declined an interview request from the Guardian. But on the day DeSantis signed into law five bills that will, among other actions, target the use of appropriate pronouns in school and prohibit minors from undergoing gender-affirming surgeries and obtaining puberty blocking medication, DeSantis said Florida “is proud to lead the way in standing up for our children. As the world goes mad, Florida is a refuge of sanity and a citadel for normalcy.” Last year, the governor signed a “don’t say gay” bill that bars instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity to children between kindergarten and third grade.

According to Equality Florida, the state’s premier advocacy group for LGBTQ+ rights, the Sunshine state is home to an estimated 886,000 gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender and non-binary people 13 years of age or older. They represent about 5% of Florida’s workforce and 4.6% of the state’s adult population.

At a time when the NAACP has issued a travel advisory warning that “Florida is openly hostile toward African Americans, people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals”, some people are voting with their feet.

Kristina Bozanich knows of a family living in St Cloud with a transgender child who will be fleeing the Sunshine state and one adult who has paused his gender transition and will be moving to California in 2024. “And I have other friends who have confirmed they will no longer visit Florida,” she adds.

But many more members of Florida’s besieged LGBTQ+ community are moving ahead with plans to celebrate Pride month and assert their gender identities. Led by Mayor Kenneth Welch, the city of St Petersburg kicked off a series of events with a flag-raising ceremony on Thursday and will hold three days of festivities during the last weekend of June. These will include a Friday night concert, a parade and a Sunday street fair.

In a similar vein, south Florida’s longest-running Pride parade will be held in the Fort Lauderdale suburb Wilton Manors on 17 June, and events are planned at the Perez Art Museum Miami and a Fort Lauderdale theater.

One of Florida’s first openly gay lawmakers welcomes the forthright affirmation of his community’s existence and future in some of the state’s largest metropolitan areas. “We’re hearing that, more often than not, our Pride events are going forward, regardless of the political environment,” said Carlos Guillermo Smith, a senior policy adviser at Equality Florida who served three terms in the Florida house of representatives between 2016 and 2022.

“People are understanding that raising their flag high and proudly is an important act of political resistance. They aren’t allowing themselves to be bullied out of continuing their Pride festivities as usual.”

READ MORE  New York Police Department officer. (photo: AP)

New York Police Department officer. (photo: AP)

It is the first public look at how officers are being trained to implement Mayor Adams’ mental health directive.

The hypothetical scenario is among five posed to police officers in a 15-minute presentation on situations that may warrant involuntary hospitalization. The training was prepared to brief patrol officers on Mayor Eric Adams’ recent directive that people may be forced to undergo psychiatric evaluation when a mental illness is seemingly preventing them from meeting their own basic needs, putting them at risk of harm.

The presentation slides are also incorporated in a 9-minute video that describes when someone experiencing mental illness should be brought to the hospital against their will and walks officers through a step-by-step protocol.

The records were obtained by the New York Civil Liberties Union in a lawsuit filed in March against the NYPD and shared with POLITICO.

Adams has homed in on the intersecting crises of homelessness and mental illness as part of a larger effort to address voters’ concerns about crime and perception of public safety. His approach has drawn outrage — and legal action — from civil rights advocates like NYCLU, who see it as both ineffective in tackling serious mental health concerns and a dangerous infringement of individuals’ constitutional rights.

The advocates have also criticized police involvement in implementing Adams’ directive in light of numerous instances of people in a mental health crisis being killed or seriously injured by NYPD officers. Adams, a former police captain, has responded by saying patrol officers would hand off cases of someone in crisis to others on the force “who have a deeper training than the surface training that an everyday police officer would.”

But the training materials, publicly disclosed here for the first time, indicate that any uniformed member of service has the authority to unilaterally decide someone needs to be brought involuntarily to a hospital because of the inability to care for one’s self.

Beth Haroules, director of disability justice litigation for NYCLU, said the presentation also seems inconsistent with city officials’ pledge to provide police with in-depth training on the “unable to meet basic needs” standard and a refresher on crisis communication strategies. Between the slides and the video, which overlap significantly, patrol officers appear to be receiving no more than 25 minutes worth of a refresher.

The police academy, meanwhile, devotes at least four-and-a-half hours to teaching entry-level officers about “policing the emotionally disturbed,” as the NYPD’s student guide calls it.

In an emailed statement, an unnamed police spokesperson said officers already receive “significant training” on interacting with people experiencing mental illness and their involuntary commitment authority. More than 90 percent of patrol, transit and housing officers have been trained regarding voluntary and involuntary transports, according to the department.

“Recruits at the Police Academy are taught about mental illness, how to recognize mental illness, effective communication, and proper tactics,” the spokesperson said in a statement. “Moreover, a significant portion of our members have received crisis intervention training to instruct members on how to effectively respond to critical incidents and enhance their communication skills with the mentally ill.”

“We are willing to do our part, and this has the full support and attention of the NYPD,” the spokesperson added.

Since Adams announced the directive Nov. 29, details on its implementation by police officers and frontline mental health workers have been scarce. City Hall has yet to release data on how many people have been involuntarily committed due to the “unable to meet basic needs” criteria. And at least one agency, NYC Health + Hospitals, has indicated it is not tracking that metric — only the total number of involuntary hospitalizations.

The scenarios presented in training sessions provide some insight into the potential situations when police officers might be using their expanded authority. A similar presentation to clinicians, which POLITICO previously obtained, outlined several different scenarios when involuntary commitment might be appropriate.

In the case of the hypothetical Queens woman, the presentation notes someone sleeping on the street during a Code Blue Warning — triggered when temperatures reach 32 degrees or lower — “may be deemed to not care for self, and may be involuntarily taken into custody for psychiatric evaluation at a hospital.”

Another scenario involves a “reasonably groomed” man living in a messy house, who says he was just released from the hospital after being abducted by aliens, according to the materials. Officers called to check on him “MAY NOT involuntarily transport the individual for a psychiatric evaluation” because he is not a threat to himself or others and does not appear unable to take care of himself, the presentation says.

Signs that someone cannot care for themself, as listed in the presentation, include a strong smell of feces or urine, rotting flesh, extreme swelling of the legs or feet, untreated wounds, no shoes, a makeshift crutch or cast, malnourishment and the presence of bugs on the body.

An internal Dec. 6 memo to all NYPD commands, sent to POLITICO by the agency, also described examples of people who might meet the standard, such as someone who is incoherent and on the subway tracks or in the path of oncoming traffic.

Patrick J. Lynch, president of the Police Benevolent Association, which represents rank-and-file NYPD officers, said the union is “constantly asking for more and better-quality training for our members, especially on sensitive and complex topics like mental health response.”

“No matter what other policies the city puts into place, police officers will inevitably remain on the front lines of the mental health crisis,” Lynch said in a statement. “We need the most thorough training possible, and we need our city leaders to support us when we carry out their directives.”

State law explicitly authorizes police and peace officers to involuntarily commit people for the purpose of a psychiatric evaluation. But civil rights groups and criminal justice advocates argue the NYPD is ill-equipped for the responsibility, at least in part because of inadequate training.

“This is not the role of NYPD,” Haroules said. “They should not be trying to navigate these very complicated social problems that implicate health issues.”

Indeed, in instances when a mental health professional is present, the training materials instruct NYPD officers to defer to that person’s judgment: “The job of [uniformed members of service] on a scene of a clinician making this decision is to support the decision of the clinician, not to argue with the clinician,” the 15-minute presentation says.

Yet clinicians with the authority to involuntarily commit someone, which include psychologists and social workers on mobile crisis teams, are few and far between compared to the NYPD’s tens of thousands of uniformed officers patrolling the city at all hours.

The slides indicate that when a clinician is not present, NYPD officers may decide unilaterally whether someone is unable to meet their basic human needs due to mental illness and must be involuntarily committed — as in the example of the woman on the street dressed inappropriately for the cold weather. (Under former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration, some people were taken involuntarily to hospitals during Code Blue Warnings.)

As part of Adams’ directive, NYC Health + Hospitals launched a support hotline that NYPD officers can call for guidance in deciding whether a particular person should be taken to a hospital involuntarily. But a presentation to train Health + Hospitals clinicians staffing the hotline, which NYCLU obtained in a public records request and shared with POLITICO, notes, “NYPD officers makes [sic] the decision.”

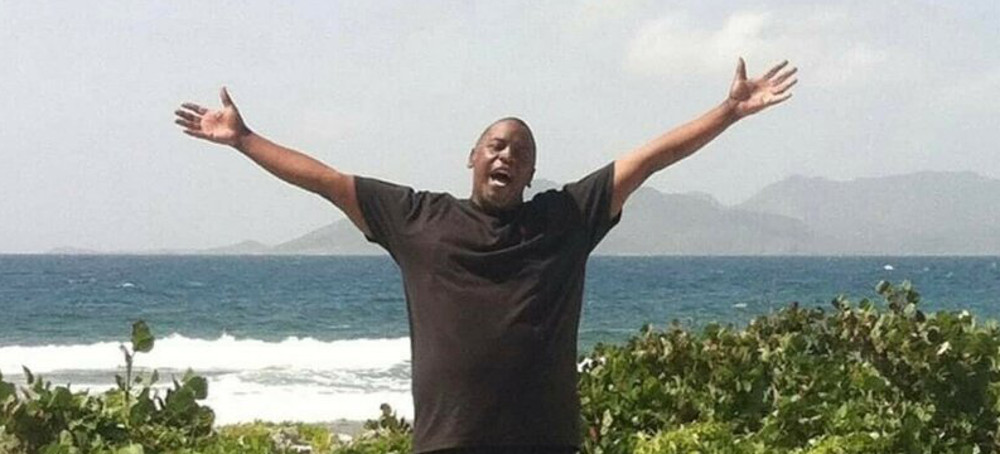

READ MORE  In 2020, when Dexter Barry learned he would be the recipient of a healthy heart, he most looked forward to the possibility of watching his grandchildren grow up. (photo: Janelle King/NPR)

In 2020, when Dexter Barry learned he would be the recipient of a healthy heart, he most looked forward to the possibility of watching his grandchildren grow up. (photo: Janelle King/NPR)

"I take rejection medicine for my heart transplant. I can't miss those doses," he said, according to body camera footage obtained by NPR.

Barry, 54, pleaded with the arresting officer seven times back in November. He alerted the jail nurse and a court judge about his condition too. But in the two days that Barry was held at Duval County Jail in Jacksonville, Fla., no one allowed him access to the medication he desperately asked for.

Three days after he was released from jail, Barry died from cardiac arrest that was caused by an acute rejection of the heart, Dr. Jose SuarezHoyos, a Florida pathologist who conducted a private autopsy of Barry on behalf of Barry's family, told NPR.

Barry's family insists that their loved one's death was entirely preventable had the jail staff taken Barry's pleas for his medication more seriously. His death, which was first reported by The Tributary, has sparked major questions about the quality of health care overseen by the Jacksonville Sheriff's Office.

"Dexter Barry's disturbing, preventable death from medical neglect highlights a major flaw in how America treats its carceral system," ACLU Florida told NPR in a statement. "We urge state officials to investigate Mr. Barry's killing and pursue justice for his loved ones."

Attorney Andrew Bonderud, who is representing Barry's family, told NPR they plan to file a lawsuit against the Jacksonville Sheriff's Office soon.

"There were so many people who could have prevented Dexter Barry's death," Bonderud said. "It seems to me that one phone call to the right person from the right person would've made a difference."

The sheriff's office declined to comment on Barry's death due to pending litigation.

A jokester who was ecstatic to watch his grandchildren grow up

Barry, a car salesman with roots in the West Indies, loved traveling to the Caribbean, talking about cars and making his children laugh.

"He was stern but fun," his daughter, Janelle King, told NPR. "He was a jokester, always cracking jokes and fun to be around."

After experiencing a near-stroke in 2008, Barry waited for a new heart for 12 years, and even moved to Florida to increase his chances of getting the procedure, King said. Barry was determined to receive the treatment because he wanted to watch his son's children grow up, as well as see King have a child of her own. In 2020, the opportunity to possibly live a longer, healthier life came true.

"He thought he was going to die before he could receive one," King said. "So, to hear that they had a heart for him, it was amazing news to everyone."

Successful heart transplant recipients can live on average 10 years longer

Some people wait months or years for donated hearts.

"Usually for every possible organ that comes up, there's a long list of recipients that would potentially be compatible with it," Dr. Juan Vilaro, a heart transplant cardiologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville, told NPR.

The process is highly selective — blood type, body size, how sick the patient is and the distance between the donor and candidate are all factors that determine who will receive the lifesaving transplant.

But once the procedure goes through, it can be transformative for ailing patients. With proper treatment and recovery, heart transplant recipients can add on average 10 years to their life span, Vilaro said.

Anti-rejection drugs play a critical role for that to come true. These medications help prevent a recipient's immune system from attacking their new heart. Therefore, they have to be taken every day for the rest of their lives. Missing several days of medication can be deadly.

"What we explain to patients, in no uncertain terms that, these medications are your lifeline," he said.

Vilaro added that in his experience, when a transplant patient ends up incarcerated, hospital staff coordinate with the jail or prison to ensure the patient continues to take their medication.

"They go through a lot of work and trouble to call the jails and make sure they get what they need," he said.

Barry's multiple pleas for his medication were ignored

On Nov. 18, Barry got into a heated argument with his neighbor, who had been using his internet in exchange for some cash to help pay the internet bill. Barry accused his neighbor of missing some payments and at one point, threatened to beat up his neighbor, who is disabled and blind. Before the fight turned physical, Barry walked away to cool off, King said.

Later that day, Barry was charged with simple assault. While in the police car, Barry alerted the police multiple times about his transplant, as well as the drugs he relied on to stay alive.

"The jail can get your medication," said J.J. McKeon, the arresting officer.

During a health intake, a jail nurse noted that Barry had a heart transplant and needed medication for it. "Urgent Referral," the nurse wrote down, as well as the location of Barry's pharmacy, according to medical documents.

The next day, at a bond hearing, Barry sounded the alarm again.

"I just had a heart transplant and I haven't took my medicine all day since I have been locked up, and I take rejection medicines for my heart so my heart won't reject it," Barry said, according to court transcripts.

Judge Gilbert Feltel responded "OK," adding that Barry could be released if he paid a bond of $503.

"Hopefully you are able to make bond here and get your medication," the judge said.

He suffered from an acute rejection of his heart, only 2 years after the surgery

Barry did not tell his family that he went to jail until he was released on Nov. 20. That evening, Barry called his son, who immediately noticed his father did not sound well and urged to him see a physician, King said.

On Nov. 23, Barry went to the hospital. There, he asked if he should double up on his anti-rejection drugs given that he had missed some doses. The nurse told him to continue taking the drugs as usual to prevent the risk of overdosing, according to King.

Later that day, Barry, feeling weak, called his home health aide to visit him. Upon arrival, the nurse phoned 911. When first responders arrived, the aide stepped outside to escort them to the apartment. But by the time they returned to his apartment, Barry was unresponsive. He was taken to a local hospital, where he was pronounced dead.

King said she is most disturbed by how many authorities knew of her father's condition.

"The officer, the judge, the jail, the nurses, the medical team, nobody did their job," she said. "As a result, my father who waited 12 years for a transplant is not here."

READ MORE  Officials attend a ceremony in honor of late Haitian President Jovenel Moise at the National Pantheon Museum in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in July 2021. (photo: Valerie Baeriswyl/AFP)

Officials attend a ceremony in honor of late Haitian President Jovenel Moise at the National Pantheon Museum in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in July 2021. (photo: Valerie Baeriswyl/AFP)

Rodolphe Jaar, a convicted drug trafficker, is the first defendant to be convicted in the slaying that plunged Haiti deeper into turmoil. He pleaded guilty in March to several charges, including conspiracy to commit murder or kidnapping outside the United States and providing material support resulting in death.

Jaar is among 11 defendants, including several Haitian Americans, who have been charged by U.S. prosecutors in the Southern District of Florida in connection with Moïse’s assassination. In Haiti, dozens have been detained, but after nearly two years, there have been few, if any, other charges.

A group of roughly 20 ex-military Colombian nationals stormed Moïse’s home in the hills overlooking Port-au-Prince on July 7, 2021, and shot him 12 times. He was 53. His wife, Martine Moïse, was wounded but survived the attack.

The assassination pushed Haiti, already roiled by political disorder, into further chaos from which it has yet to emerge. Violent gangs stepped into the power vacuum, conducting mass kidnappings, displacing more than 130,000 people and transforming daily life into what one regional leader last year called a “low-intensity civil war.”

Though U.S. authorities have made several high-profile arrests in the plot in recent months and have secured one conviction, much about the assassination remains unclear, including who, ultimately, was its mastermind.

U.S. Judge Jose E. Martinez sentenced Jaar to life on each of three counts during a 10-minute hearing Friday in a Miami courtroom. Government prosecutors requested a life sentence, according to a plea agreement.

U.S. prosecutors allege two U.S. residents — Antonio Intriago, 59, a Venezuelan, and Arcangel Pretel Ortiz, 50, a Colombian — devised a plan through a Florida-based company to oust Moïse and replace him with Christian Sanon, an aspiring Haitian politician, who promised them “lucrative” infrastructure contracts in return.

The men, prosecutors allege in court filings, hired about 20 Colombian mercenaries to carry out the plan. When the group realized that Sanon lacked the constitutional qualifications to become president, they decided that a former Haitian Supreme Court judge would replace Moïse instead.

U.S. prosecutors have said that the initial plan was to “extract” Moïse from Haiti in June 2021 by plane, but the plan fell apart because the group could not secure an aircraft. Organizers then began plotting to assassinate the then-president.

Jaar, 50, was accused of providing the money used to buy the weapons used in the assassination and to bribe unnamed Haitian officials who were responsible for Moïse’s security, allowing the mercenaries easy access to the compound. Jaar is also alleged to have provided his co-conspirators with food and lodging.

Jaar told U.S. investigators in December 2021 that he “provided firearms and ammunition to the Colombians to support the assassination operation” and that he had directed a co-conspirator to hide in an embassy in Haiti after the murder, authorities said in a criminal complaint.

U.S. authorities arrested and charged Jaar in January 2022 in the Dominican Republic, where he fled after the assassination. They said he agreed to be flown to Miami and had been cooperating with them.

U.S. authorities filed charges against eight suspects this year, including Sanon, who they allege smuggled 20 ballistic vests from South Florida to Haiti “for use by his private military forces.”

READ MORE 3M sold "forever chemicals" for decades. Will it foot the bill to get them out of our water supply? (photo: Grist)

3M sold "forever chemicals" for decades. Will it foot the bill to get them out of our water supply? (photo: Grist)

3M sold "forever chemicals" for decades. Will it foot the bill to get them out of our water supply?

“Are you prepared for this?” the aide asked when Peters returned her call. The rest came very quickly. The state had identified a class of chemicals linked to cancer called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS or “forever chemicals,” in Stuart’s drinking water supply. The chemicals were at dangerously high levels.

Peters, who had never even heard of PFAS before, emailed Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection for more information. The department explained that in 2012, the federal Environmental Protection Agency had added, for the first time, two types of PFAS — pronounced PEA’-fass — to its list of “unregulated contaminants” that public water systems must test for. Stuart had run tests in 2014 and 2015 and found both chemicals, PFOS and PFOA, in its water supply. But the city and the state environmental agency hadn’t thought much of it, since the contamination, at a combined 200 parts per trillion, or ppt, was not thought to be at a level that was harmful to human health.

But in May 2016, days before the legislative aide called Peters, the U.S. EPA issued a new policy: Levels of the two PFAS in drinking water, the agency said in a national health advisory, should not exceed 70 ppt.

What this meant was that Stuart’s public water utility — winner of multiple awards, including a statewide “best-tasting water” competition — had been unintentionally poisoning its constituents. Subsequent testing showed some of the city’s individual wells had levels of PFAS higher than 1,000 ppt. There was no way to turn back the clock. People had been drinking the poisoned water, and no one knew for how long.

Thus began, Peters told lawyers in a 2021 deposition, a “week in hell.”

Peters collected himself and began to devise a plan. By the end of the week, the city had discovered that levels of PFAS in water from all of the city’s municipal wells averaged out to 65 ppt, just 5 ppt below the EPA’s new standard, and had pulled its three most contaminated wells offline. Peters and other officials weren’t satisfied. They had been caught off guard once, and they weren’t willing to let it happen again.

“We weren’t about to take a chance on getting caught with a system that wouldn’t treat down to below detection levels under any circumstance,” Peters said in the deposition. The city’s goal since 2016 has been to get PFAS contamination in its drinking water supply to “non-detect,” or as close to zero ppt as possible.

But achieving non-detect status has proved to be wildly expensive and, ultimately, out of reach for a city of Stuart’s size and means. Conventional water-purification techniques, such as the use of chlorine, don’t work on tiny and persistent forever chemicals. So the city implemented a new water scrubbing system in order to rid its 30 wells of PFAS. The system, which is called an ion-exchange treatment, relies on magnetlike resins to attract PFAS molecules. The resins, once loaded up with contaminants, have to be incinerated to destroy the chemicals. The city has spent roughly $20 million keeping its PFAS levels below 30 ppt — a maximum limit Stuart set for itself — thus far. It estimates that the cost of replacing the resin, which cannot be reused, is approximately $2 million per year. That cost will increase incrementally as the city strives to get its contamination level down to zero.

“We can’t afford to spend that kind of money every year,” Peters said in his deposition. “We’re a small utility, a small municipality.”

Stuart’s efforts to clean up its water are at the heart of a lawsuit of epic proportions that could have wide-ranging financial repercussions for more than 100 million Americans in the years to come. Next week, Stuart’s lawyers plan to argue in federal court that the companies that manufactured and distributed PFAS not only contaminated Stuart’s water supply, but did so knowingly for decades. They will make the case that those companies, not the city or its residents, should cover the cost of cleanup for Stuart — and for any other city with similarly contaminated drinking water.

The question underpinning the case is one that has consumed Peters’s professional life since 2016: Once you know there’s poison in the well, who’s responsible for getting rid of it?

PFAS do not naturally break down in the environment over time. Their resistance to decay is what makes them useful. It’s also what makes them dangerous.

In 1938, a scientist at DuPont De Nemours and Company, commonly known as DuPont, discovered the first PFAS chemical that would be widely used by Americans in the home — Teflon, the patented name for the type of forever chemical that makes certain cookware nonstick. But the multinational chemical conglomerate 3M quickly became the nation’s chief producer of PFAS. The company manufactured the chemicals for use in its own products and sold them to other chemical companies, like DuPont, for their products, too. PFOA, PFOS, and the thousands of other obscurely named acronymic chemicals under the PFAS umbrella were added to millions of products Americans used — and still use — on a regular basis: pizza boxes, seltzer cans, contact lenses, dental floss, mascara, rugs, sofas.

3M started winding down PFAS production in the 2000s under pressure from the EPA. The company recently announced that it will cease production of forever chemicals entirely by 2025. But the hundreds of millions of pounds of the chemicals the company produced for more than half a century still persist, indefinitely, in the environment. They’re also lingering inside of us: in our blood and our excrement, primarily via the foods we eat and the water we drink.

A growing body of research on the health ramifications of years of sustained exposure to PFAS paints a frightening picture: The chemicals have a disturbing affinity for blood. Once they find their way to the bloodstream, they stick to blood cells as they course through every organ in the body. Studies show PFAS can weaken immune systems and contribute to long-term illnesses like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer — specifically, testicular, kidney, and prostate cancers. A recent study linked PFAS in drinking water and household products such as food packaging to startling decreases in fertility in women. Studies on prenatal and childhood exposure to PFAS show adverse developmental effects, including low birth weight and accelerated puberty.

Since Stuart’s water crisis in 2016, the body of research illuminating the harmful health effects of PFAS has become more robust, prompting the EPA to take more forceful steps to limit consumer exposure to these chemicals. Earlier this year, the EPA proposed a set of new guidelines for six PFAS, including PFOA and PFOS. Unlike its 2016 health advisory standards, these limits — 4 parts per trillion, down from 70 ppt — are enforceable, meaning that water-supply managers must adhere to them or face fines. It’s the first time the agency has taken such a step, a move that underscores just how poisonous the EPA believes PFAS to be, even in minuscule amounts. The decision to regulate PFAS represents a huge win for public health. That win will come at a cost.

The new standard, once it becomes official later this year, will trigger a nationwide effort to rid drinking water supplies of forever chemicals. The projected costs of eliminating PFAS from the water supply are astronomical, beyond the scope of what cities, utilities, and the average consumer can afford. Preliminary estimates suggest that the price tag on filtering forever chemicals out of America’s drinking water is more than $3.8 billion per year. That cost will get passed on to consumers, unless the companies responsible for creating the contamination in the first place are forced to pay. That’s where Stuart’s lawsuit against 3M comes in.

The product at the center of the lawsuit, which will be heard in the U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina, is called aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF, which has been used by the U.S. military and local fire departments, including Stuart’s, across the nation. The foam’s key ingredient — what makes it so effective at putting out fires — is PFAS. Stuart is arguing that 3M and other manufacturers of ingredients used in firefighting foam knowingly pulled off one of the largest mass poisonings in American history and, crucially, that they hid what they knew about PFAS from the government and the general public in order to continue selling their products.

3M and the other defendants in the case maintain that their products can’t be tied to the plaintiff’s PFAS contamination and therefore they are not liable for the cost of cleaning it up. 3M “will vigorously defend its record of environmental stewardship,” the company said in a statement to Grist. “3M will continue to remediate PFAS and address litigation by defending ourselves in court or through negotiated resolutions, all as appropriate.”

3M has settled multiple PFAS-related lawsuits since 2005, including multimillion dollar settlements with Minnesota and Michigan. But the company has never admitted liability for the contamination the lawsuits alleged.

Stuart’s lawsuit is what lawyers call a “bellwether case” — it’s the first of more than 4,000 lawsuits that have been filed by cities, utilities, and individuals against 3M and other manufacturers of AFFF. Lawyers on both sides carefully chose Stuart as the most representative plaintiff out of the thousands of cases after analyzing the city’s water samples, reading through thousands of documents in the legal process known as discovery, and even exploring the city in person. Stuart’s case will serve as a litmus test for the lawsuits in line behind it, determining how lawyers for the other plaintiffs move forward with their respective arguments. If Stuart succeeds, 3M could be on the hook for one of the biggest mass tort payouts in U.S. history. If it fails, everyday Americans could see their water bills balloon in the years to come.

“3M is a corporate giant that was built in no small part on the profits of these PFAS chemicals. They contaminated drinking water supplies and people across the United States,” David Andrews, a senior scientist at the Environmental Working Group, an environmental health nonprofit, told Grist. “Holding them accountable is significant, both in terms of direct cost to consumers but … also as a signal to companies that produce industrial chemicals about the long-term costs of some of these chemistry decisions.”

Grist spoke with the plaintiffs’ lawyers and reviewed hundreds of documents filed in court to build a narrative account of the years leading up to Stuart’s discovery in 2016, including details about what 3M knew in the 1970s about the dangers its products posed to the general public. Some of the information in this article, including testimony in which a former 3M toxicologist admits that global PFAS contamination can be linked to 3M, has never been reported before.

“We’re dealing with something that is unprecedented in scope and scale,” Rob Bilott, the environmental attorney whose work investigating the chemical industry’s role in manufacturing forever chemicals was instrumental in bringing public attention to PFAS in the early 2000s, told Grist. Bilott, who initially sued DuPont for poisoning communities in West Virginia, is also involved in this new round of litigation.

“It’s going to be incredibly expensive to deal with this,” Bilott said. “I think it’s important for the public to know how much this company knew about the hazards of these materials.”

The USS Forrestal, the Navy’s first “supercarrier” ship, was gearing up for an attack off the coast of Vietnam on the morning of July 29, 1967, when a rocket accidentally slipped loose from a fighter plane idling on the ship’s huge deck. The rocket fired across the runway and pierced another jet. Hundreds of gallons of fuel flowed from the damaged plane, spreading quickly across a deck that had been stocked with aircraft, artillery, and bombs in preparation for the attack. When the fuel encountered a lingering rocket spark, it started a fire that raged for 24 hours, killing 134 people and injuring 161.

The conflagration was one of the deadliest naval disasters on record since World War II.

The Navy convened two separate panels to investigate what happened aboard the Forrestal. The resulting reports, aimed at improving “warship survivability,” recommended ships carry larger quantities of more effective firefighting foams.

In the 1960s, when the company was best known to the public for its masking tape and abrasive sponges, 3M began working on a new type of firefighting foam in collaboration with the Navy. They called the foam “light water,” but it’s now better known by its technical name, aqueous film-forming foam. The foam worked better than conventional firefighting foams and had a virtually unlimited shelf life.

In short order, light water became the firefighting foam of choice by the American military at home and abroad. By the 1970s, it had become a staple — not just on Navy ships, but also at military bases, commercial airports, and, ultimately, local fire departments across the country.

AFFF’s active ingredient, what makes the foam so good at smothering blazes, is “fluorinated surfactant,” otherwise known as perfluorooctane sulfonic acid, or PFOS. For decades, the foam, which was sprayed on real fires and just as often used by fire departments to conduct firefighting drills, was routinely dumped over the sides of ships and onto bare earth, where it leached into the environment and migrated into local drinking water supplies. 3M started winding down production of AFFF in 2000 as the EPA ramped up pressure on the chemical giant to disclose information about its products. But other companies stepped in to fill the void.

Stuart’s fire department began purchasing drums of AFFF from 3M in 1989, according to its lawyers — a decision that would later haunt the city. Court documents show the fire department often used AFFF to conduct training exercises in the field behind the firehouse. Once the city started analyzing water samples from the city’s 30 interconnected drinking water wells, it didn’t take long to discover that the samples with the highest levels of PFAS were located near the fire house.

On May 31, 2016, days after Peters’s call with the administrative aide, all personnel in Stuart’s fire department received a terse email from the city’s fire chief. AFFF was not to be used anymore except for in emergencies, it said, “effective immediately.” The PFAS firehose had finally been shut off, 27 years after it had been inadvertently turned on.

“At no time during the relevant period did the Defendants warn Stuart Fire Rescue that the ingredients in the AFFF were persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic,” Stuart’s legal complaint reads. 3M, as well as Dynax Corporation, Tyco Fire Products LP, Buckeye Fire Equipment Company, Chemguard, and National Foam Inc. — the other defendants in the case — exposed “thousands of innocent residents to water contaminated with dangerous chemicals,” the complaint alleges.

Though the Pentagon recently began to transition to PFAS-free firefighting foam — leading state and local firefighting agencies to do the same — the chemicals are still where fire departments left them for half a century.

What 3M knew about the effect its products had on human health comprises the main thrust of Stuart’s lawsuit against 3M and the other companies that manufactured and sold AFFF. The city’s lawyers have obtained millions of pages of official and unofficial internal company correspondence via discovery. If the plaintiffs can marshall the evidence contained in those pages to convince the jury that the PFAS industry knew its chemicals were widespread among the general public and suspected they were harmful to humans, the jurors may find the companies that produced these products liable for damages. Stuart’s argument, which will be echoed by the 4,000-plus plaintiffs waiting for their day in court, hinges on a few crucial moments in the late 1970s.

Company records, produced in discovery and filed in court, show that executives at 3M started to have an inkling their products were harmful to human health in 1975. That year, two independent scientists called 3M — the main mass-manufacturer of PFAS at the time — to inform the company that they had found PFAS compounds in their own blood and other blood samples. 3M pleaded ignorance. But actions taken by executives in 3M’s upper ranks in the months and years after the company was contacted by the scientists show that the company didn’t remain ignorant for long. 3M found out that PFAS were not only in its employees’ blood, but circulating widely in the blood of the general population, and that the chemicals were potentially carcinogenic. The company kept that information from the federal government, its factory workers, consumers, and the general public.

In 1976, 3M found forever chemicals in the blood of its factory workers, and internal laboratory tests on monkeys and rats had produced worrying results. In June 1978, 3M’s commercial chemical division sent a confidential letter to 3M’s general counsel and executives in the company’s medical and research departments. The company’s president of U.S. operations, Lewis Lehr, had “specifically requested” that 3M meet with an outside consultant to see whether its products containing PFAS were toxic. 3M hadn’t reported its tests to the EPA, which legally requires chemical companies to test and report the health impacts of their products, particularly if they appear to be harmful to humans. Lehr, the letter said, wanted “an independent opinion as to whether we are correct in our assumption that we do not have a reportable situation.”

The first outside expert the company spoke to was a renowned toxicologist named Harold C. Hodge. 3M executives flew to San Francisco to meet with Hodge in April 1979. According to the notes that a 3M staffer drafted at that meeting and are included in the cache of lawsuit documents, Hodge recommended that the company reduce its employees’ exposure to forever chemicals. The draft notes also include an addendum Hodge added by phone about a week later, after he had reviewed more study results provided by 3M. The company, he said, should figure out if PFAS were in the general population and, if so, at what levels. “If the levels are high and widespread,” he said, “we could have a serious problem.”

The next day, 3M executives met with another expert, J.R. Mitchell, from the Baylor School of Medicine in Houston. Draft notes from that meeting show that Mitchell told the company that some of the results from its studies on PFAS in animals “are similar to those observed with carcinogens.”

But the official meeting notes from both meetings, disseminated within the company in June 1979, do not include either of those statements by the outside experts. 3M struck them from its official records. Despite accumulating copious evidence that its products were widespread in the general population and posed serious risks to human health, the company neither alerted the EPA nor ceased production of PFAS. In the years that followed, 3M produced approximately 100 million pounds of POSF, the precursor to the chemical used in AFFF. It and other PFAS chemicals brought in $300 million in annual revenue for 3M.

3M has never publicly admitted that any of the forever chemicals found in samples from around the world could be linked to its products. But ahead of the trial, and over 3M’s vehement objection, the judge ruled that a deposition given by John Butenhoff, a former toxicologist at 3M who worked at the company for nearly four decades starting in the 1970s, could be considered as evidence in the case.

In a video of that deposition, one of Stuart’s lawyers asks Butenhoff a series of questions about where PFAS have been found. “You’re aware that PFOS has been detected and reported in rivers and streams?” the lawyer asks.

“Yes, I have awareness of that,” Butenhoff replies.

The lawyer lists off other places PFAS have been found: soil, sediment, the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, drinking water, human blood, umbilical cord blood, breast milk, shellfish, fish, indoor house dust, outdoor air, and polar bear blood. Butenhoff confirms that the chemicals have been found in all of those places.

“In each and every one of these media all around the world,” the lawyer asks, “the source of PFOS is more likely than not 3M, correct?”

“I think that more likely than not the source is 3M, yes,” Butenhoff replies.

While 3M was raking in billions from its PFAS products, cities like Stuart were unknowingly digging themselves into a pit.

The costs Stuart has had to shoulder, and potential long-term health consequences for the Florida city’s residents, could have been avoided if the defendants were upfront about the dangers of PFAS, Stuart’s lawsuit says. “Had Defendants provided adequate instructions and warnings, the contamination of the groundwater and drinking water supply with toxic and carcinogenic chemicals would have been reduced or eliminated,” it says. “Defendants’ conduct was so reckless or wanting in care that it constituted intentional or grossly negligent conduct.”

Stuart is not alone in its battle against forever chemicals. The prohibitive cost of getting PFAS out of local water supplies is a reality local officials and water providers across the nation are grappling with as the EPA prepares to codify its enforceable standards in the next several months. Once the standards are enacted, utilities will have three years, until 2026, to comply with them.

The federal government has directed roughly $10 billion to help the nation address its PFAS contamination problem. That pot of money includes $2 billion worth of grants to help alleviate the cost of cleaning out contaminants from drinking water in small or disadvantaged communities. But experts say even $10 billion is a drop in the bucket; some estimates put the total cost of ridding the entire nation’s water supply of PFAS somewhere between $200 billion and $400 billion. An estimated 1 in 20 Americans have forever chemicals in their drinking water, a figure that could increase as smaller utilities that were not required to test for PFAS between 2013 and 2015 start looking for them.

There is no easy solution to this problem; every path forward includes expensive equipment and laborious treatment processes. If Stuart and other cities aren’t successful in getting 3M to pay for the damage, the costs will be shouldered by tens of millions of utility customers, also known as ratepayers.

“The ratepayer is paying for the capital, they’re paying back a loan … and they’re paying for the personnel, the equipment, the replacement parts, the electricity,” Steve Via, director of federal relations for the American Water Works Association, an international coalition of water suppliers, told Grist. “All of it comes back to the ratepayer.”

The American Water Works Association analyzed the cost of PFAS cleanup for utilities and households in a report published in March. The typical American household located in an area where PFAS cleanup must take place is looking at an average annual cost of between $200 and $350 per year, which would be passed on to ratepayers through their water bills, according to Via. But there are disparities depending on the size of the community. The annual cost of PFAS for households in large communities is much lower than it is in small ones, where fewer ratepayers share the financial burden. In those less populated areas, the annual cost tops $1,000 a year — a significant expense for the average family.

“This is going to be expensive,” Via said. “None of these systems have been saving money in advance for this because they didn’t know they were going to be required to treat to 4 ppt.”

Sara Hughes, a professor of water policy at the University of Michigan, said some communities will be able to bear these costs more comfortably than others. In poorer communities, especially smaller ones where the average cost of PFAS remediation is much higher than the projected national average, the burden will be felt more acutely.

“Even $20 more a month means very different things to some households than others,” Hughes said. “For households that are already living on the edge, one more thing, one more bill, one more increase in the cost of living, can be pretty significant.”

The upfront financial cost of remediating the contamination these companies knowingly put into the environment is one facet of the long-term burden American families will face. But the larger and ultimately more devastating consequence is the impact PFAS has had, and will continue to have, on health. These chemicals have already been linked to various cancers, diabetes, infertility, childhood developmental delays, and other issues scientists are still uncovering. Many victims of PFAS poisoning don’t even know that their ailments may be linked to these chemicals, but their lives and bank accounts will feel the impacts.

To this day, 3M’s position on PFAS, according to its website, is that they are “safe and effective for their intended uses.”

Stuart’s lawsuit will probe the strength of this assertion. The more than 4,000 AFFF lawsuits comprise what’s called “multidistrict litigation,” a type of legal proceeding that’s similar to a class-action lawsuit. They fall into multiple categories: The first, spearheaded by Stuart, is made up of water-supply contamination cases. The next bucket of complaints will be personal injury cases — people who claim that exposure to PFAS in firefighting foam led to cancer diagnoses. Many of those plaintiffs are current or former firefighters. Yet more plaintiffs seek restitution for property damage caused by PFAS contamination.

In the months leading up to the bellwether trial, 300 cases per month on average were added to the multidistrict litigation. As of April, the total number of plaintiffs was 4,173.

The costs of dealing with PFAS contamination are “just now beginning to be recognized,” Bilott, the environmental attorney, said. “I think you’re going to see efforts now underway all over the planet to try to make sure that the people who created this global contamination are responsible for the global implications of cleaning it up.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.